95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Educ. , 23 March 2022

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.853020

This article is part of the Research Topic Trauma-Informed Education View all 11 articles

More than half of United States adults have experienced potentially traumatic events. Given that reminders of these events can spur re-traumatization, facilitators of professional learning about trauma-informed practices must be intentional in their delivery to avoid re-traumatizing participants. Based on our experience delivering professional learning in trauma-informed practices to K-12 educators, we outline key strategies for facilitators. We organize these strategies using the United States Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) 6 key principles of a trauma-informed approach: safety; trustworthiness and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment, voice, and choice; and cultural, historical, and gender issues. Within each principle, we offer three strategies along with rationale and supporting research for each. Example strategies include learning about the school, staff, and students as much as possible before leading the training (collaboration and mutuality), conveying that there is not a “one size fits all” answer to addressing student trauma (trustworthiness and transparency), and providing time for educators to reflect on how to apply the content to their classrooms (empowerment, voice, and choice). We demonstrate alignment of these strategies with implementation supports of trauma-informed learning (e.g., relevance to school community) and provide facilitators with action planning questions to guide selection of recommended strategies. We conclude with important next steps for research on the delivery of trauma-informed professional learning.

Calls for trauma-informed schools have gained substantial momentum over the past two decades (Overstreet and Chafouleas, 2016; Harper and Temkin, 2019), thus facilitating significant interest in training educators in trauma-informed practices. Multiple resources outlining key concepts about trauma have been developed for facilitators planning to deliver this training (National Child Traumatic Stress Network [NCTSN], 2008; Chafouleas et al., 2016; McIntyre et al., 2019). Far less, however, has been written about how to deliver this content in a trauma-informed manner. This omission in available resources is notable as more than 60% of United States adults have experienced potentially traumatic events (Merrick et al., 2019), and reminders of these events can cause re-traumatization (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2014b).

Re-traumatization, or the reexperiencing of traumatic stress, can occur when a situation reminds someone of their original source of trauma. Re-traumatization can cause psychological distress that inhibits learning (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2014b), rendering the professional learning (PL) opportunity less beneficial, and potentially harmful, for educators. Therefore, every effort should be made to avoid re-traumatization during trauma-informed PL experiences.

In this commentary, we draw on our experience delivering professional learning in trauma-informed practices to K-12 educators. We offer strategies for facilitators aiming to deliver effective trauma-informed PL while avoiding potential for participant re-traumatization. Although our focus is on school-based professional learning, these strategies can be applied in other settings (e.g., conferences, university classes). In addition, as most trauma-informed PL includes didactic training (Chafouleas et al., 2016), we primarily orient our examples toward this format but encourage application across trauma-informed coaching, consultation, and policy conversations.

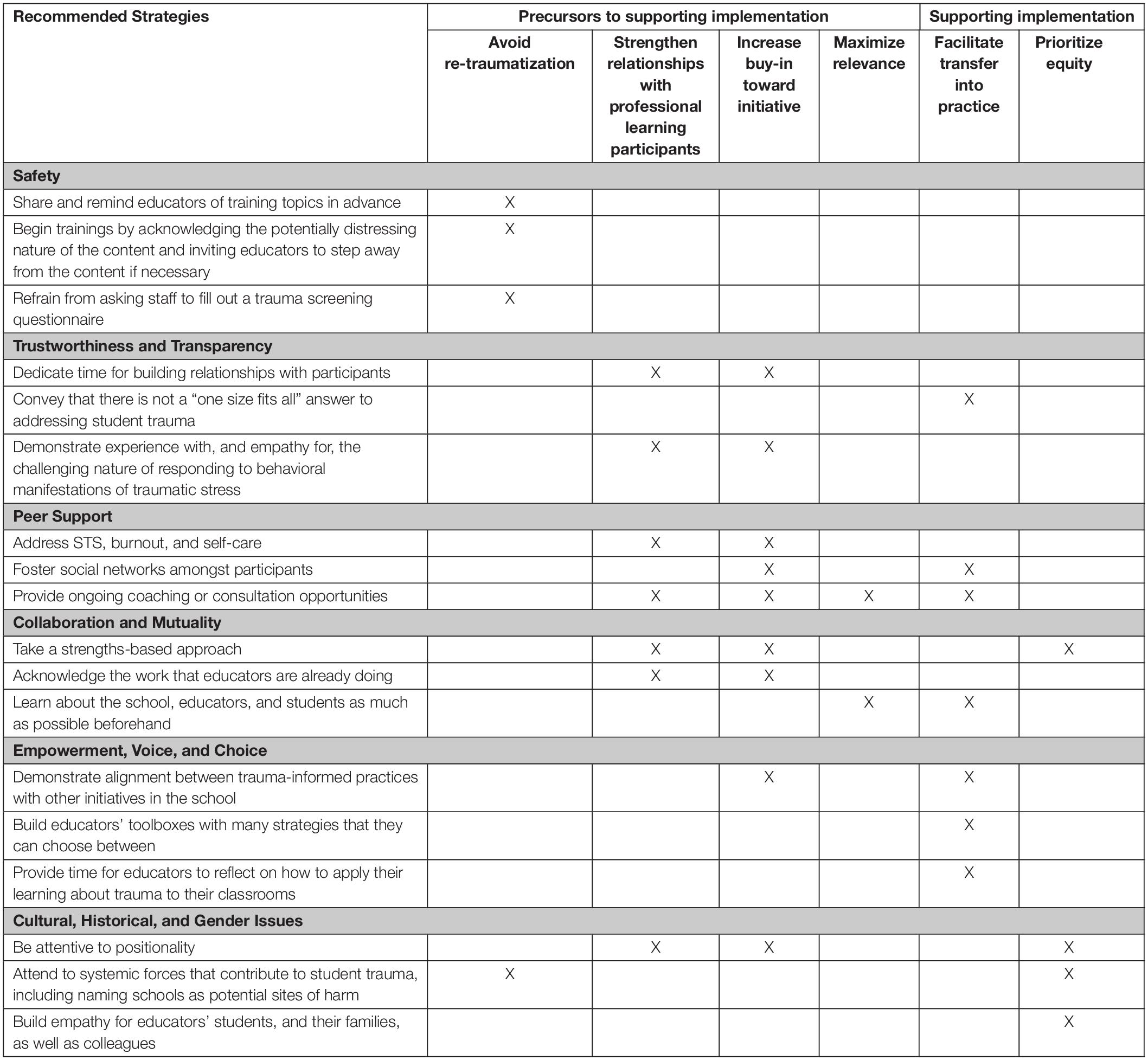

Although there is no universal definition of trauma-informed care (Hanson and Lang, 2016; Hanson et al., 2018), a recent systematic review of trauma-informed clinical care for adolescents (Bendall et al., 2021) found that Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s [SAMHSA’s] (2014a) definition, or close variations, is the most predominantly used. SAMHSA’s definition has been used in publications around the world (e.g., Sweeney et al., 2016; Atwool, 2019; Lotty et al., 2020), and thus, there is substantive rationale to organize recommended strategies using SAMHSA’s framework. In the framework, 6 key principles of a trauma-informed approach have been identified: safety; trustworthiness and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment, voice, and choice; and cultural, historical, and gender issues. In this commentary, we outline three strategies for each of SAMHSA’s six principles for a total of 18 recommendations. We provide rationale and supporting research for each strategy. Then, we demonstrate alignment of these strategies with implementation supports of trauma-informed learning (Table 1). In Table 2, we offer facilitators with action planning questions to guide selection of recommended strategies, understanding that it may not be relevant or feasible to implement all recommended strategies at once. We conclude with important next steps in research on the delivery of trauma-informed professional learning.

Table 1. Alignment of recommended strategies with implementation supports of trauma-informed learning.

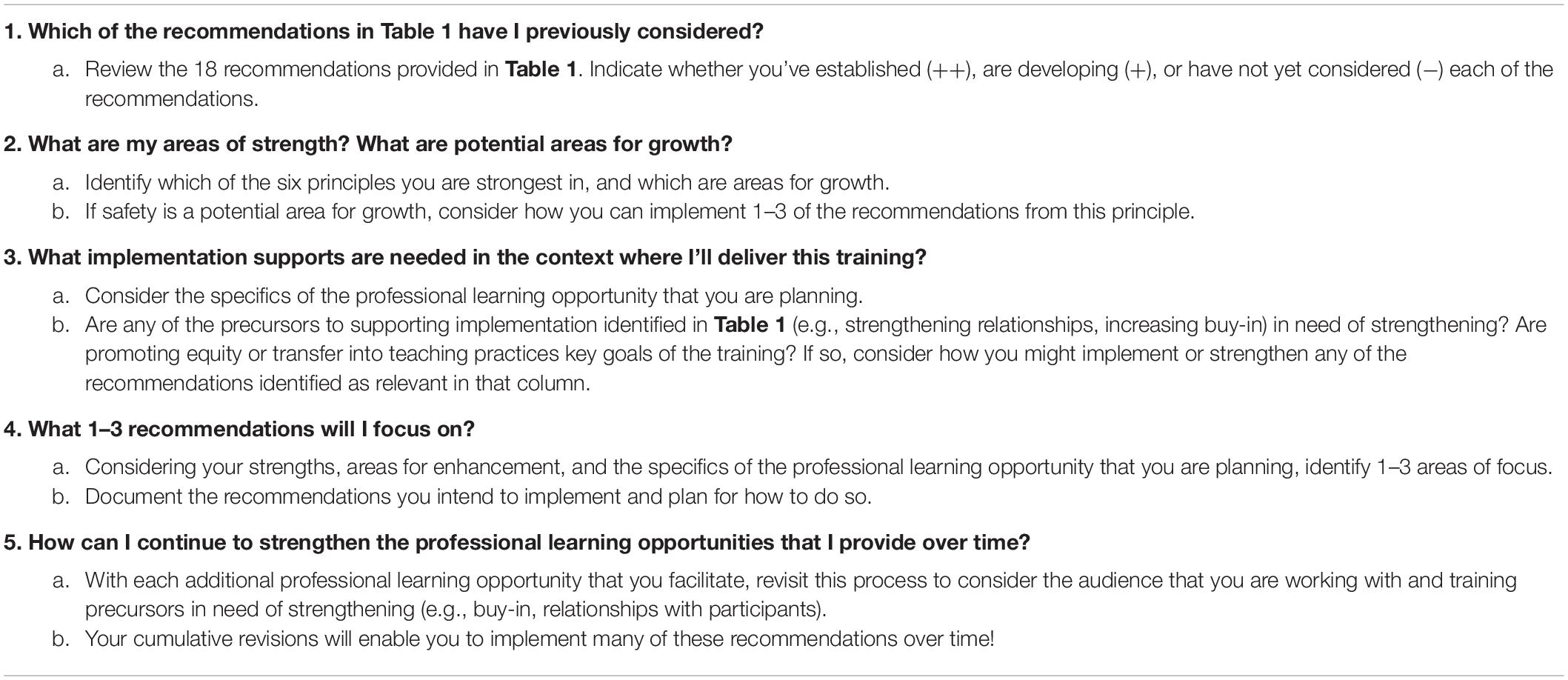

Table 2. Questions to guide facilitator action planning to deliver professional learning that is trauma informed.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s first principle of a trauma-informed approach is safety, including both physical and psychological safety. To promote safety for educators participating in trauma-informed professional learning, facilitators should (1) share and remind educators of training topics in advance, (2) begin trainings by acknowledging the potentially distressing nature of the content and invite educators to step away from the content if necessary, and (3) refrain from asking staff to fill out trauma screening questionnaires (e.g., Adverse Childhood Experiences [ACE] questionnaire; Felitti et al., 1998).

Sharing topics in advance promotes safety by providing opportunity for educators to proactively plan for their involvement and self-care related to the topic (Black, 2006, 2008; Boysen, 2017). For example, if educators anticipate being triggered by a topic, they can plan to implement strategies for self-care (e.g., breathing techniques, sitting near the door, requesting an excusal from the training). A reminder the day beforehand allows educators to proactively put these strategies in place. Facilitators should consult with school personnel about the best method for sharing the specific training topics with staff (e.g., email, meeting agenda); facilitators may choose to do so in multiple ways to increase the likelihood that staff receive advance warning. In addition, facilitators should begin trainings by acknowledging the potentially distressing nature of the content and invite educators to step away from the content if needed. Finally, although sharing research on the prevalence of potentially traumatic events (Felitti et al., 1998; Bethell et al., 2017) can be helpful in building educator knowledge of the scope of the concern, this should be done without having staff fill out questionnaires or being asked to self-report their own experiences as these direct reminders of traumatic events could be distressing and re-traumatizing (Miller, 2001).

Trauma-informed approaches promote trustworthiness and transparency (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s [SAMHSA’s], 2014a). In the context of educator professional learning in trauma-informed practices, trustworthiness and transparency can be advanced by (1) dedicating time for building relationships with participants, (2) conveying that there is not a “one size fits all” answer to addressing student trauma, and (3) demonstrating experience with, and empathy for, the challenging nature of responding to behavioral manifestations of traumatic stress.

Dedicating time for building relationships with participants is likely to generate trust that increases educators’ investment in the content and suggested shifts in teaching practices (Bryk and Schneider, 2002). The implementation of trauma-informed practices often asks educators to rethink some of their teaching practices (e.g., discipline approaches; Guskey, 2002; National Child Traumatic Stress Network Schools Committee [NCTSN], 2017), which may be well established and even part of their conception of what it means to be an effective teacher (Chen et al., 2012). Trust and positive relationships with the facilitator can help to promote the vulnerability, reflection, and risk-taking that reconsidering teaching practices requires (Timperley et al., 2007; Thompson et al., 2020).

Facilitators are also encouraged to communicate that there is not a “one size fits all” approach to addressing student trauma. In our experience, educators are often looking for the “answer” or the trauma-informed practice(s) that they can implement to resolve their students’ challenges. However, the impact and presentation of trauma is diverse (Harvey, 1996) and different strategies will benefit students at different times (Perry and Pollard, 1998). This is not to say that there are not well-established trauma-informed teaching practices (e.g., Perry and Graner, 2018); instead, key elements of trauma-informed practice are actively brainstorming how to best support a specific situation and engaging in some trial and error to assess students’ responses. Reinforcing this point demonstrates transparency and may promote ongoing implementation despite inevitable challenges.

Finally, educators appreciate professional learning experiences where the facilitator understands the reality of their day-to-day work (Boston Consulting Group, 2015). We suggest that facilitators demonstrate experience with, and empathy for, the challenging nature of working with students exposed to trauma. We encourage facilitators to share stories from their own work, including personal mishaps encountered and subsequent learning and adjustment that followed. This sharing reinforces the idea that there is not a “one size fits all” approach and that implementing trauma-informed practices will not always go smoothly. Relatedly, we encourage facilitators to acknowledge the emotional and potentially draining nature of disruptive and challenging student behaviors; this demonstrates empathy. We find that educators are more likely to reflect upon their responses to these behaviors when they have received validation for how difficult they can be. In sum, storytelling and transparency about the challenges of the work can be powerful tools for generating trust and rapport with participants (Barbour, 2015; Berger and Quiros, 2016).

Peer support is another important element of trauma-informed approaches. Peer support is particularly important because educators are vulnerable to secondary traumatic stress (STS; Figley, 1995) due to their work with students who have experienced trauma. Facilitators can provide peer support by (a) addressing STS, burnout, and self-care; (b) fostering social networks amongst participants, and (c) providing ongoing coaching or consultation opportunities to educators.

Facilitators should address STS, burnout, and self-care to promote educators’ wellbeing while they are engaged in this work. Educators are vulnerable to STS, or trauma responses (e.g., startle, sleep disruption), due to their work with students who have experienced trauma (Figley, 1995; Hydon et al., 2015). STS can have detrimental consequences on both personal and professional wellbeing (e.g., withdrawal from relationships and work responsibilities). Fortunately, school-based discussions of STS and self-care can buffer against these risks (Hydon et al., 2015; Lawson et al., 2019). Trauma-informed professional learning should address and seek to mitigate the toll that this work can take on educators (for a resource, see National Child Traumatic Stress Network [NCTSN] and Secondary Traumatic Stress Committee, 2011).

One strategy for mitigating educator STS is to foster social networks amongst participants. Positive relationships are one of the strongest buffers against the negative effects of STS. Participants should be given opportunities to share their experiences and strategies for attending to their own wellbeing while engaged in this work. Facilitators can also provide guidance for ongoing self-care and peer support (e.g., Chafouleas et al., 2020; University of Connecticut Collaboratory on School and Child Health, 2021).

Finally, one-time trainings are generally ineffective in shifting educator practices (Wei et al., 2009; Desimone and Garet, 2015). In addition, specific to trauma trainings, educators report challenges translating information they learn in didactic trainings into their classrooms (Wittich et al., 2020). Therefore, consistent with others in the field (Dorado et al., 2016; Wittich et al., 2020), we encourage facilitators to provide peer support through ongoing coaching and consultation for educators. Sustained support with implementing training content and opportunity to seek guidance for challenges specific to their classrooms can make the work highly relevant and more likely to be transferred into practice (e.g., Guskey, 2002; Darling-Hammond et al., 2017).

Trauma-informed approaches invest in collaboration and mutuality. We recommend that facilitators of trauma-informed professional learning (a) take a strengths-based approach, (b) acknowledge the work that educations are already doing, and (c) learn about the setting as much as possible beforehand.

Educators value and deserve learning opportunities where they are treated like professionals (Boston Consulting Group, 2015). Facilitators are encouraged to take a strengths-based approach to delivering trauma trainings, highlighting educators’ many strengths working with students. This can be done, for example, by making time and space for educators to share the expertise that they bring to the work. It is also important to highlight the strengths of students who have experienced trauma. Because much of the training content may focus on negative impacts of trauma on students’ learning, it is critical that facilitators showcase student strengths and reinforce that students’ experiences of trauma are due to societal failures beyond students’ control (Chafouleas et al., 2021).

Related to highlighting the expertise that educators bring to the work, facilitators should acknowledge the work that educators are already doing to support students who have experienced trauma. Even when educators have not received comprehensive training in trauma, it is likely that they are engaged in intentional work (e.g., providing academic, social, and emotional supports) to scaffold the learning of these students (Koslouski and Stark, 2021). Highlighting these efforts may help educators to feel validated for their work, reinforce relationships and rapport with the facilitator, and strengthen buy-in amongst educators.

As relevance to the school community is a key element of effective PL, facilitators are also encouraged to learn about the school, teachers, and students as much as possible before delivering professional learning experiences (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017). A primary barrier to the implementation of trauma-informed practices is educators feeling that the learning did not fit their context (McIntyre et al., 2019; Wittich et al., 2020). For example, in a setting where students are highly dysregulated and crisis management is the norm, PL focused on building students’ social and emotional competencies may initially be difficult to implement; instead, PL focused on regulatory strategies (e.g., yoga, music, rhythmic movement) may be more effective and allow for subsequent attention to social and emotional skills (Perry and Dobson, 2013). Facilitators should also tailor the content of their trainings to the types of trauma experienced in the community (e.g., migration stress, systemic racism, addiction). Gathering this information can equip facilitators with information to facilitate contextually relevant training (for a helpful resource, see New Orleans Trauma-Informed Schools Learning Collaborative, 2019). To maximize relevance, facilitators might seek feedback on training materials from a small number of educators in the setting in advance of the actual training.

Trauma-informed approaches prioritize empowerment, voice, and choice. Working with educators, facilitators of trauma-informed professional learning should (a) demonstrate alignment between trauma-informed practices and other initiatives in the school, (b) build educators’ toolboxes with multiple strategies, and (c) provide time for educators to reflect on how to apply their learning to their classrooms.

Educators are exposed to a wide variety of professional learning initiatives and educational reforms (Wilson et al., 2011). Over time, this can lead to “initiative overload,” whereby educators grow cynical toward any new initiative, questioning the value and sustainability of anything new (Blodgett, 2018, p. 105). Therefore, it is important that facilitators demonstrate how trauma-informed practices align with other initiatives. For example, facilitators may emphasize that when students are better able to regulate their trauma responses, they are increasingly available for learning across curriculum areas. This understanding may motivate educators to integrate trauma-informed practices into their work across initiatives and to see the synergistic benefit of these practices.

Next, facilitators should introduce educators to a variety of strategies that support students who have experienced trauma (e.g., regulating activities: movement, drumming, rocking, humming) and encourage them to choose strategies likely to be most beneficial in various circumstances. This choice reinforces that there is not a “one size fits all” approach to trauma-informed teaching and encourages educators to apply their expertise in response to various challenges that arise.

Facilitators should also provide time for educators to reflect on how to apply the content they have learned to their classrooms. This reflection may facilitate transfer of learning into classroom practices and promotes educator empowerment, voice, and choice. Educators report that they are not often given time in professional learning opportunities to engage in reflection and application work, but when they are, it supports their transfer of learning into their work with students (Koslouski, 2021).

Finally, trauma-informed approaches attend to cultural, historical, and gender issues. To be trauma informed, facilitators of professional learning need to (a) be attentive to their positionality in relation to the educators, students, and families in the community, (b) attend to systemic forces that contribute to student trauma, including naming schools as potential sites of harm, and (c) build empathy for educators’ students, and their families, as well as colleagues.

Facilitators are encouraged to be attentive to their positionality in relation to those they are working with. Facilitators should reflect upon how their identity, experiences, and current role influence their work. Due to systemic racism, bias, and legacies of harm, traumatic experiences are disproportionately experienced in minoritized communities (Fortuna et al., 2020). Meanwhile, the majority of United States educators hold majority identifies (Spiegelman, 2020). Therefore, it is particularly important that facilitators reflect on their positionality in relation to the educators, students, and communities with whom they are engaging. The ADDRESSING framework (Hays, 2008) can offer a valuable starting place for engaging in this work.

Goodman (2015) noted that “[T]rauma does not occur in a vacuum; it arises in a sociopolitical context and is influenced and sometimes caused by systemic forces, such as political violence, racism and economic inequality” (pp. 64–65). Early work on trauma-informed schools often overlooked this point, locating experiences of trauma in homes, families, and communities, rather than as a result of oppressive and ever-present social conditions (Mayor, 2019; Gherardi et al., 2020). This perpetuates harm inflicted on families and communities by reinforcing deficit narratives (Mayor, 2019). Facilitators are encouraged to acknowledge and attend to structural racism, economic inequality, and systemic forces that cause and contribute to student experiences of trauma. This attention may also serve to protect educators from re-traumatization during the training by contextualizing experiences rather than implying blame toward childhood caregivers or communities. Importantly, facilitators also need to address schools as potential sites of harm, showing how schools have historically and contemporarily caused or exacerbated student trauma (e.g., through biased and exclusionary school discipline; Gherardi et al., 2020).

Lastly, facilitators should promote empathy for educators’ students and their families, as well as colleagues. At its core, trauma-informed teaching is about relationships and empathy (Chafouleas et al., 2021). Attending to cultural, historical, and gender issues necessitates that empathy is built across stakeholders. One way to do this is to illustrate how systemic conditions (e.g., compromised access to healthcare or affordable housing) contribute to family stress and potential experiences of student trauma (e.g., homelessness, household substance use; Ellis and Dietz, 2017). In addition, describing the neurodevelopmental interruptions caused for students by traumatic experiences (Perry, 2009) can build educator empathy for students. Finally, attention to STS can facilitate empathy for colleagues. Professional learning opportunities in trauma-informed practices that do not promote empathy for students, families, and colleagues risk perpetuating harm rather than promoting support and healing. Facilitators are encouraged to think deeply about the cultural, historical, and gender issues that are relevant to their work with educators.

In addition to aligning strategies with SAMHSA’s framework, we highlight how these strategies support implementation of trauma-informed teaching practices (see Table 1). Research and experience indicate that strong relationships between educators and the facilitator (Koslouski, 2021), high levels of staff buy-in (Cole et al., 2013; Collaborative Learning for Educational Achievement and Resilience, 2018), and relevance to the school community (Wittich et al., 2020) all support the implementation of trauma-informed teaching practices. We identify avoiding re-traumatization, supporting transfer into practice, and promoting equity as additional key goals of professional learning in trauma-informed practices.

We recognize that our list of recommendations is long and encourage facilitators to assess their own strengths and opportunities for enhancement (see Table 2). Facilitators might consider which of SAMHSA’s six principles they are strongest in, and which are priorities for growth. If not yet considered in the training design, we suggest that facilitators first focus on the area of Safety. Facilitators can also use the columns in Table 1 (e.g., strengthening relationships, increasing buy-in) to identify next steps. For example, if increasing buy-in is a priority, facilitators may choose to focus on recommendations identified in that column. We recommend that facilitators focus on incorporating 1–3 recommendations at a time, re-visiting choices in future trainings to make additional enhancements.

In this commentary, we draw on extensive experience conducting trainings but encourage future investigation of how these strategies support educator learning and implementation of trauma-informed practices. Important next steps in the field of trauma-informed professional learning also include research to evaluate impact on educator knowledge and attitude toward the professional learning as well as their capacity to effectively implement trauma-informed practices.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

JK and SC contributed to the conception and design of the manuscript. JK drafted the manuscript. Both authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

The authorship and publication of this article were made possible in part by funding from the Neag Foundation, which serves as a philanthropic force for positive change in education, health, and human services initiatives.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Atwool, N. (2019). Challenges of operationalizing trauma-informed practice in child protection services in New Zealand. Child. Fam. Soc. Work 24, 25–32. doi: 10.1111/cfs.12577

Barbour, R. (2015). “The power of storytelling as a teaching tool,” in Creativity, Engagement and the Student Experience. eds G. Brewer and R. Hogarth (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 178–189. doi: 10.1057/9781137402141_18

Bendall, S., Eastwood, O., Cox, G., Farrelly-Rosch, A., Nicoll, H., Peters, W., et al. (2021). A systematic review and synthesis of trauma-informed care within outpatient and counseling health settings for young people. Child. Maltreat. 26, 313–324. doi: 10.1177/1077559520927468

Berger, R., and Quiros, L. (2016). Best practices for training trauma-informed practitioners: supervisors’ voice. Traumatology 22, 145–154. doi: 10.1037/trm0000076

Bethell, C. D., Davis, M. B., Gombojav, N., Stumbo, S., and Powers, K. (2017). Issue Brief: Adverse Childhood Experiences Among US Children. Available online at http://www.cahmi.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/aces_fact_sheet.pdf (accessed January 5, 2022).

Black, T. G. (2008). Teaching trauma without traumatizing: a pilot study of a graduate counseling psychology cohort. Traumatology 14, 40–50. doi: 10.1177/1534765608320337

Black, T. G. (2006). Teaching trauma without traumatizing: principles of trauma treatment in the training of graduate counselors. Traumatology 12, 266–271. doi: 10.1177/1534765606297816

Blodgett, C. (2018). “Trauma-informed schools and a framework for action,” in Violence and Trauma in the Lives of Children. eds J. D. Osofsky and B. M. Groves (Westport, CT: Praeger).

Boston Consulting Group (2015). Teachers Know Best: Teachers’ Views on Professional Development. Boston, MA: Boston Consulting Group.

Bryk, A. S., and Schneider, B. L. (2002). Trust in Schools: A Core Resource For Improvement. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Boysen, G. A. (2017). Evidence-based answers to questions about trigger warnings for clinically-based distress: a review for teachers. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. Psychol. 3, 163–177. doi: 10.1037/stl0000084

Chafouleas, S. M., Johnson, A. H., Overstreet, S., and Santos, N. M. (2016). Toward a blueprint for trauma-informed service delivery in schools. Sch. Ment. Health 8, 144–162. doi: 10.1007/s12310-015-9166-8

Chafouleas, S. M., Koriakin, T. A., Iovino, E. A., Bracey, J., and Marcy, H. M. (2020). Responding to COVID-19: Simple Strategies that Anyone Can Use to Foster An Emotionally Safe School Environment. Available online at: https://csch.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2206/2020/07/CSCH-Report-Responding-to-COVID-19-Simple-Strategies-7-6-20.pdf (accessed January 5, 2022).

Chafouleas, S. M., Pickens, I., and Gherardi, S. A. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): translation into action in K12 education settings. Sch. Ment. Health 13, 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12310-021-09427-9

Chen, J., Brown, G. T., Hattie, J. A., and Millward, P. (2012). Teachers’ conceptions of excellent teaching and its relationships to self-reported teaching practices. Teach. Teach. Educ. 28, 936–947. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2012.04.006

Cole, S. F., Eisner, A., Gregory, M., and Ristuccia, J. (2013). Helping Traumatized Children Learn: Creating and Advocating for Trauma-Sensitive Schools. 2. Boston, MA: Massachusetts Advocates for Children.

Collaborative Learning for Educational Achievement and Resilience (2018). CLEAR End of Year Staff Survey Results 2017-2018. Spokane, WA: Collaborative Learning for Educational Achievement and Resilience.

Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., and Gardner, M. (2017). Effective Teacher Professional Development. Available online at https://edpolicy.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/professional-learning-learning-profession-status-report-teacher-development-us-and-abroad_0.pdf (accessed March 8, 2022).

Desimone, L. M., and Garet, M. S. (2015). Best practices in teachers’ professional development in the United States. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 7, 252–263. doi: 10.25115/psye.v7i3.515

Dorado, J. S., Martinez, M., McArthur, L. E., and Leibovitz, T. (2016). Healthy environments and response to trauma in schools (HEARTS): a whole-school, multi-level, prevention and intervention program for creating trauma-informed, safe and supportive schools. Sch. Ment. Health 8, 163–176. doi: 10.1007/s12310-016-9177-0

Ellis, W. R., and Dietz, W. H. (2017). A new framework for addressing adverse childhood and community experiences: the building community resilience model. Am. Pediatr. 17, S86–S93. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.12.011

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., et al. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 14, 245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

Figley, C. R. (1995). “Compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress disorder: An overview,” in Compassion Fatigue: Coping with Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder in Those Who Treat the Traumatized. ed. C. R. Figley (New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel).

Fortuna, L. R., Tolou-Shams, M., Robles-Ramamurthy, B., and Porche, M. V. (2020). Inequity and the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color in the United States: the need for a trauma-informed social justice response. Psychol. Trauma 12, 443–445. doi: 10.1037/tra0000889

Gherardi, S. A., Flinn, R. E., and Jaure, V. B. (2020). Trauma-sensitive schools and social justice: a critical analysis. Urban Rev. 52, 482–504. doi: 10.1007/s11256-020-00553-3

Goodman, R. D. (2015). “A liberatory approach to trauma counseling: decolonizing our trauma-informed practices,” in Decolonizing “Multicultural” Counseling Through Social Justice. eds R. D. Goodman and P. C. Gorski (Berlin: Springer), 55–72. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1283-4_5

Guskey, T. R. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teach. Teach. 8, 381–391. doi: 10.1080/135406002100000512

Hanson, R., Lang, J., Goldman Frasier, J., Agosti, J., Ake, G., Donisch, K., et al. (2018). “Trauma-informed care: Definitions and statewide initiatives,” in The APSAC Handbook on Child Maltreatment. eds J. B. Klika and J. R. Conte (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE), 272–291.

Hanson, R. F., and Lang, J. (2016). A critical look at trauma-informed care among agencies and systems serving maltreated youth and their families. Child Maltreat. 21, 95–100. doi: 10.1177/1077559516635274

Harper, K., and Temkin, D. (2019). Responding to Trauma Through Policies to Create Supportive Learning Environments. Available online at: https://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/RespondingTraumaPolicyGuidance_ChildTrends_January2019.pdf (accessed February 18, 2022).

Harvey, M. (1996). An ecological view of psychological trauma and trauma recovery. J. Trauma. Stress 9, 3–23. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490090103

Hays, P. (2008). Addressing Cultural Complexities in Practice: Assessment, Diagnosis, and Therapy, 2nd Edn. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, doi: 10.1037/11650-000

Hydon, S., Wong, M., Langley, A. K., Stein, B. D., and Kataoka, S. H. (2015). Preventing secondary traumatic stress in educators. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 24, 319–333. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2014.11.003

Koslouski, J. B. (2021). A Professional Development Series in Trauma-Informed Teaching Practices: A Design-Based Research Study [Doctoral dissertation]. Morrisville, NC: ProQuest.

Koslouski, J. B., and Stark, K. (2021). Promoting learning for students experiencing adversity and trauma: the everyday, yet profound, actions of teachers. Elem. Sch. J. 121, 430–453. doi: 10.1086/712606

Lawson, H. A., Caringi, J. C., Gottfried, R., Bride, B. E., and Hydon, S. P. (2019). Educators’ secondary traumatic stress, children’s trauma, and the need for trauma literacy. Harv. Educ. Rev. 89, 421–447. doi: 10.17763/1943-5045-89.3.421

Lotty, M., Bantry-White, E., and Dunn-Galvin, A. (2020). The experiences of foster carers and facilitators of fostering connections: the trauma-informed foster care program: a process study. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 119:105516. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105516

Mayor, C. (2019). Whitewashing trauma: applying neoliberalism, governmentality, and whiteness theory to trauma training for teachers. Whiteness Educ. 3, 198–216. doi: 10.1080/23793406.2019.1573643

McIntyre, E. M., Baker, C. N., and Overstreet, S., and New Orleans Trauma-Informed Schools Learning Collaborative. (2019). Evaluating foundational professional development training for trauma-informed approaches in schools. Psychol. Serv. 16, 95–102. doi: 10.1037/ser0000312

Merrick, M. T., Ford, D. C., Ports, K. A., Guinn, A. S., Chen, J., Klevens, J., et al. (2019). Vital signs: estimated proportion of adult health problems attributable to adverse childhood experiences and implications for prevention — 25 states, 2015–2017. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 68, 999–1005. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6844e1external

Miller, M. (2001). Creating a safe frame for learning: Teaching about trauma and trauma treatment. J. Teach. Soc. Work 21, 159–176. doi: 10.1300/J067v21n03_12

National Child Traumatic Stress Network [NCTSN], and Secondary Traumatic Stress Committee (2011). Secondary Traumatic Stress: A Fact Sheet for Child-Serving Professionals. Los Angeles, CA: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress.

National Child Traumatic Stress Network [NCTSN] (2008). Child Trauma Toolkit for Educators. Los Angeles, CA: National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

National Child Traumatic Stress Network Schools Committee (2017). Creating, Supporting, and Sustaining Trauma-Informed Schools: A System Framework. Los Angeles, CA: National Child Traumatic Stress Network, Schools Committee.

New Orleans Trauma-Informed Schools Learning Collaborative (2019). Guide for a Cultural Audit. New Orleans, LA: New Orleans Trauma-Informed Schools Learning Collaborative.

Overstreet, S., and Chafouleas, S. M. (2016). Trauma-informed schools: Introduction to the special issue. Sch. Ment. Health 8, 1–6. doi: 10.1007/s12310-016-9184-1

Perry, B. D. (2009). Examining child maltreatment through a neurodevelopmental lens: clinical applications of the neurosequential model of therapeutics. J. Loss Trauma 14, 240–255. doi: 10.1080/15325020903004350

Perry, B. D., and Dobson, C. L. (2013). “The neurosequential model of therapeutrics,” in Treating Complex Traumatic Stress Disorders in Children and Adolescents, eds J. D. Ford and C. A. Courtois (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 249–260.

Perry, B. D., and Graner, S. (2018). The Neurosequential Model in Education: Introduction to the NME Series: Trainer’s Guide. Houston, TX: The ChildTrauma Academy Press.

Perry, B. D., and Pollard, R. (1998). Homeostasis, stress, trauma, and adaption: a neurodevelopmental view of childhood trauma. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 7, 33–51. doi: 10.1016/S1056-4993(18)30258-X

Spiegelman, M. (2020). Race and Ethnicity of Public School Teachers and their Students. Available online at: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2020/2020103/index.asp (accessed January 5, 2022).

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s [SAMHSA’s] (2014a). SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] (2014b). Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Sweeney, A., Clement, S., Filson, B., and Kennedy, A. (2016). Trauma-informed mental healthcare in the UK: what is it and how can we further its development? Ment. Health Rev. J. 21, 174–192. doi: 10.1108/MHRJ-01-2015-0006

Thompson, P. W., Kriewaldt, J. A., and Redman, C. (2020). Elaborating a model for teacher professional learning to sustain improvement in teaching practice. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 45, 81–103. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2020v45n2.5

Timperley, H., Wilson, A., Barrar, H., and Fung, I. (2007). Professional Learning and Development: A Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration. Auckland: University of Auckland.

University of Connecticut Collaboratory on School and Child Health (2021). Building Simple Action Plans to Strengthen your Well-Being [Webinar and Supporting Materials]. Storrs, CT: University of Connecticut Collaboratory on School and Child Health.

Wei, R. C., Darling-Hammond, L., Andree, A., Richardson, N., and Orphanos, S. (2009). Professional Learning in the Learning Profession: A Status Report on Teacher Development in the United States and Abroad. Available online at: https://edpolicy.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/professional-learning-learning-profession-status-report-teacher-development-us-and-abroad.pdf (accessed September 5, 2021).

Wilson, S. M., Rozelle, J. J., and Mikeska, J. N. (2011). Cacophony or embarrassment of riches: building a system of support for quality teaching. J. Teach. Educ. 62, 383–394. doi: 10.1177/0022487111409416

Keywords: professional learning (PL), educator wellbeing, avoiding re-traumatization, implementation, trauma-informed schools

Citation: Koslouski JB and Chafouleas SM (2022) Key Considerations in Delivering Trauma-Informed Professional Learning for Educators. Front. Educ. 7:853020. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.853020

Received: 12 January 2022; Accepted: 01 March 2022;

Published: 23 March 2022.

Edited by:

Judith Howard, Queensland University of Technology, AustraliaReviewed by:

Helen Elizabeth Stokes, The University of Melbourne, AustraliaCopyright © 2022 Koslouski and Chafouleas. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jessica B. Koslouski, SmVzc2ljYS5rb3Nsb3Vza2lAdWNvbm4uZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.