- Faculty of Education, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Through the use of a case study, this paper explores the provision of educational and support services to a group of marginalized young parents in Melbourne, Australia. Teenage parents present as a vulnerable population, and are at risk of becoming socially, economically and culturally disadvantaged. However, young parent support programs, such as the program under study in this project, act as rafts, providing a much-needed lifeline to student participants. These programs engage young parents back into education, after withdrawal due to pregnancy, and increase their likelihood of a life without social disadvantage. Utilizing one site from the young parents’ program, this study examined the educational and support provision to young parents, through a strengths-based, social justice lens. The study yielded the RAFT framework, which may be used to better position young parents to tackle the challenges of their dual roles. Targeting educational providers, teachers and community organizations, the projects attempts to reduce social distance and barriers for the participants.

Highlights

When accommodating young parents in educational programs in secondary schools should be cognizant of:

– Teenage parents may be one of the most vulnerable populations in our societies and advocating for them and their success is a collective responsibility.

– Responsivity toward the needs of young parents in secondary school encapsulates acceptance, sponsorship and advocacy.

– Young parents as students differ from their mainstream counterparts in secondary school, and therefore require a more adaptable and malleable teaching and learning program.

– Education programs for young parents in secondary school, should be flexible and pliable, accommodating changing schedules, unexpected absence, and being sensitive to the ever-altering needs of the student.

– In this context, inclusivity is facilitated largely through the educators, the support staff and the networks which maintain programs for marginalized young people.

Introduction

The study explores to the educational provision for a group of adolescent mothers who were accommodated at a community learning center in the south-eastern of Melbourne. Findings from a report by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW] (2020) found that teenage pregnancies made up 2.2% of all live births. Early parenthood is a significant shift for young people with some studies acknowledging the positivity of this early maturational experience (Price-Robertson, 2010). Biologically, young mothers appear to experience fewer challenges with labor and pregnancy-related diabetes, however, from a psychological and social perspective, these young people become vulnerable and potentially marginalized [Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2020]. Teenage mothers are at risk of socioeconomic disadvantage and could perpetuate a cycle of teenage parenting in the future (Gaudie et al., 2010). There are also links between teenage motherhood and reduced wellbeing outcomes for both mother and baby—babies are likely to be of low birth weight with mothers experiencing behavioral, emotional and cognitive difficulties (Marino et al., 2016). Depression has been recorded as a known drawback of teenage pregnancy (Marino et al., 2016). Against this context, this research examines the experiences of young mothers at a site in Melbourne, in an attempt to document their re-engagement into education. Utilizing a strengths-based approach, the current study considered how the program offered at this site attempted to address student needs, as young parents and to break cycles of disadvantage. A study of this nature is significant as it addresses how the needs of young parents could be met, within a nurturing and supportive program. Consequently, the documenting of a single site’s experiences and provision may act as a basis for other providers, allowing the program’s model to be replicated. The study closes with the construction of the RAFT framework, drawing on research contained within the discussion, as a means to inform and support future programs which provide for marginalised and vulnerable youth.

An exploration into the literature

Returning to a mainstream school can be an intimidating experience for pregnant or parenting teens; since they are surrounded by other teens whose worries may seem inconsequential relative to their own. These young women need support to re-engage with their education to ensure that their future aspirations can become reality. This educational program may not be in the mainstream setting with a traditional program. The rate of teen pregnancy in Australia is decreasing, with births to teen mothers dropping between 2006 and 2017. The majority of these teen pregnancies occur in women living in remote areas, who come from socio-economic disadvantage, or identify as Indigenous [Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2020]. There is a cyclical repetition—teens from these disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to fall pregnant—and this embeds the existing disadvantage regarding the educational and financial opportunities of these young women. The teenage pregnancy rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders is almost eight times higher than that of non-Indigenous women. It is also higher for young women in rural and remote areas and those who have been in out-of-home care [Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2020]. If intervention is not available for these women, the outcomes for the mother and child are poor, including educational attainment, poverty, physical and mental health, homelessness, child protection services and issues with the law (SmithBattle, 2007; Pinzon and Jones, 2012; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2020). The support provided for young parents has been neglected in terms of policy and practice in Australia (Beauchamp, 2020). In other developed countries, the rate of teenage pregnancy has been declining on account of increased birth control measures and educational programs targeted at prevention. For example, in the United States, the percentage of teenage pregnancies dropped from 17.4% to 16.7% {Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2021 #334}. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, pregnancy rates decreased by 60% from 1993 to 2018, with just 17 teenagers becoming pregnant {Nuffield Trust, 2022 #335}.

Teenage mothers have traditionally been perceived with negativity, with expectations that the pregnancy and birth of their child will only lead them to a pathway of becoming welfare recipients (Ellis-Sloan, 2018). The outlook is negatively positioned for both mother and infant, and is regarded as problematic for society (Ellis-Sloan, 2018). Others note that teenage mothers compromise or violate societal pathways, often to their own peril (SmithBattle, 2018). However, there is emerging research around the transformative impact of having a child on the life of the teen parent (SmithBattle, 2018). The stereotype that their educational aspirations and their lives are “derailed” by becoming a mother are widespread, and yet if these teens have family support and access to community support there is minimal disadvantage for the teens (SmithBattle, 2018). While these expectations and aspirations may not correspond with those of their non-child bearing peers, they have been increasing over recent decades. What they may encounter is “role conflict” which relates to the duality of their roles as a mother and as a student (Carlson, 2016). While mainstream schools may be inclusive and supportive, they may not be able to address the very particular requirements of the young parents. Their educational needs may require programs that support them academically and also in terms of accommodating their parenting requirements with mentoring programs that offer a tiered level of support, from academic, to social and emotional, parenting skills and general life and career skill development (Rowen et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2019).

In SmithBattle’s (2005) 12-year longitudinal study conducted with 16 teen mothers, she discovered that the birth of a child to a teen mother was not a predictor of their future. For many, it is a chance to reboot their life and work to address previous adversity, becoming caring mothers. However, this did generally require interaction with others supporting them, whether that be a partner, parent, or another, such as a health care nurse or a teacher. These people could have discussions with the girls about their future plans, dreams and goals and encourage the girls to pursue these (SmithBattle, 2002, 2005). This support “when combined with long-term support, advocacy, mentoring, and linkages to resources, creates and sustains new horizons and connections” (SmithBattle, 2005, p. 845). These are the key elements necessary for an effective educational program for parenting teens.

Hindin-Miller (2018) acknowledged that pregnancy can be a turning point for girls to ‘re/assemble’ their life, describing the school she helped to establish in New Zealand for teenage parents. The school and the early-childhood centre were physically connected so the young mothers could see and hear their children playing, which assisted with communication with child-care workers and helped with breastfeeding, time with their babies and the settling of babies. Transportation was organised to assist the girls and their babies to travel to and from school and social workers were employed to support the young women with issues such as alcohol and drugs, relationships, finances, housing, legal advice and advocacy when dealing with a number of agencies. Healthy meals were provided and food was often shared and prepared by the young mothers. Dental services and medical checks were also provided. There was a low student to teacher ratio and each girl had an Individual Education Plan (IEP), which outlined their career aspirations. The school offered regular secondary school educational subjects as well as some tertiary-level programs. Other co-curricular programs were offered, such as sports, cooking and crafts. Outings were organised with the girls and their children, relatives were encouraged to join and guest speakers were often invited. The girls also were supported to obtain their driver’s license and first-aid certificates. This holistic provision for the young women and the support they required resulted in ‘challenging and transforming conventional school practices’ (Hindin-Miller, 2018, p.260). These included supportive relationships with teachers and other staff members, and time with other young women and children. The re/assembling of these girls’ identities emerged through this ‘context, offering positive narratives about who they could become as young women, as learners and as parents’ (Hindin-Miller, 2018, p. 260). The school became a home away from home, often a safe haven.

These programs not only support these young women with their educational aspirations, but it also has broader implications, obviously for the mother and child, but also to society (Basch, 2011), because it will be a conduit for these young women to find meaningful employment and ensure the future for both themselves and their child. For these programs to be successful, they need to ideally start during the pregnancy, have a multi-disciplinary approach, ensure accessibility of services, address transport and child care barriers, include a multi-generational approach and involves the father of the baby, be culturally appropriate and attends to the physical and mental health needs of the participants, including the building of resilience. The stigma of accessing services needs to be removed. They need to have social and peer support and a safe place for all of this to take place. If the young mother does not return to education within 6 months after giving birth, there is an increased likelihood of another pregnancy within 2 years (Department of Social Services, 2017). An analysis by the Department of Social Services, suggests that 79 per cent of young parents will be receiving income support payments in 10 years, 57 per cent will be receiving income support payments in 20 years (Department of Social Services, 2017). Further, “around 16 per cent will remain on income support for the rest of their lives” (Department of Social Services, 2017, p. 7).

The establishment of the young parents’ program

What is needed to support pregnant and parenting teens is a safe and supportive school environment, such as that outlined by Hindin-Miller (2018). Traditional schools often do not provide helpful and practical support, such as academic support, health-care, child care and counseling, and their educational needs may be neglected (Roxas, 2008). The young parents’ program in Melbourne’s south-east offer pregnant and parenting young people with a program that re-engages them into education by offering a flexible learning environment. They are able to have their babies with them until the child is able to walk or is 12 months of age. A qualified childcare worker is on-site to assist with care of the babies and to provide mentoring and guidance to the young mothers. In order to assist with facilitation, a small team of academics became involved, delivering literacy programs and developing an approach to evaluate the program to ascertain success factors. As part of the course offered to students, they are able to undertake a Victorian Certificate of Applied Learning (VCAL) course, offering them a pathway to tertiary study. Other stakeholders support the program by providing expertise to enable these young women to continue their education, and to be more prepared as parents. The current study was focused on one of these learning hubs and was shaped by the following questions.

Research questions

1. What are the factors that contribute to the positive experiences of young parents within a customized educational program?

2. How has the program accommodated the changing needs of young parents?

3. What are the unique characteristics of the educational programs which accommodate the needs of young parents?

Theoretical framework

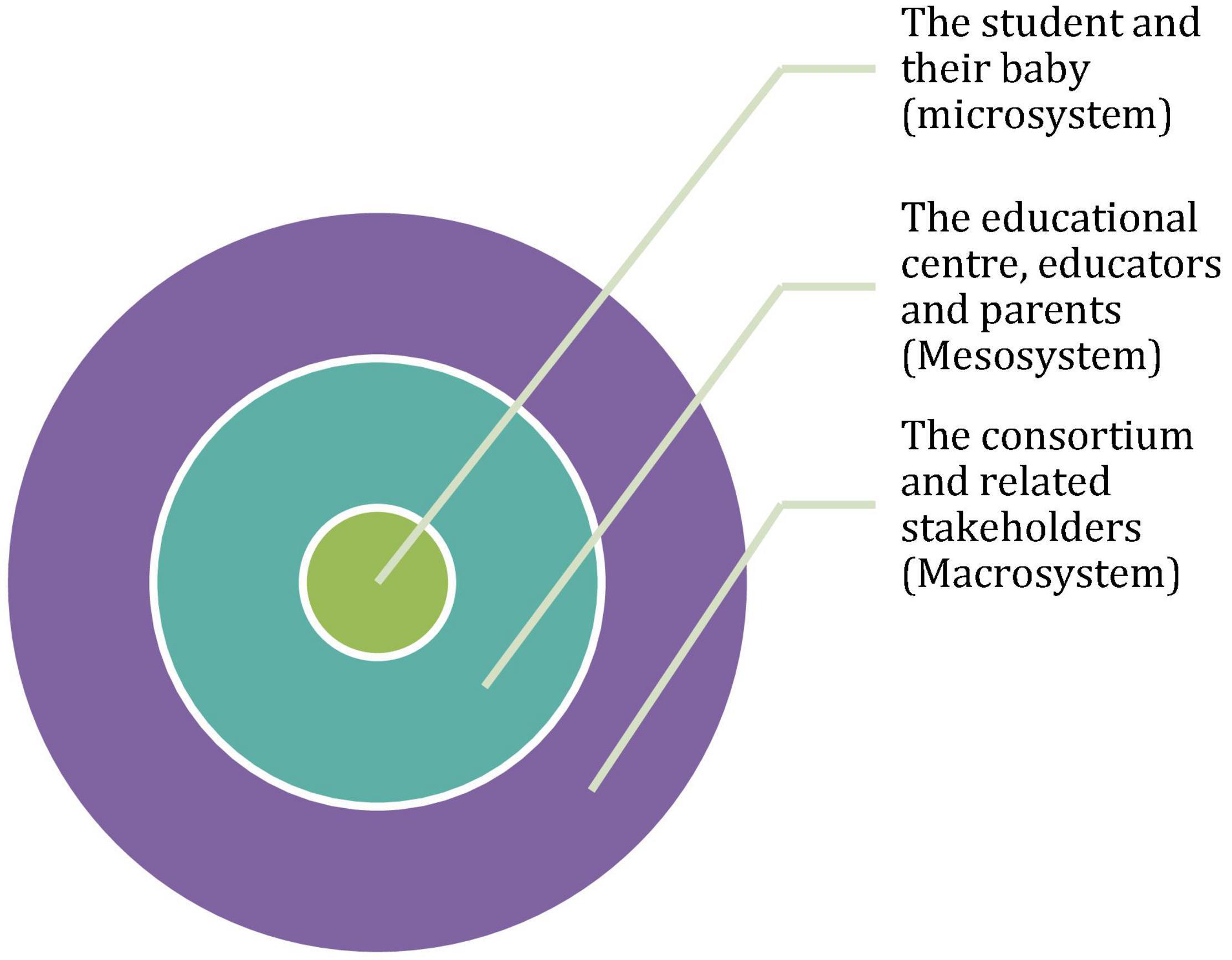

Bronfenbrenner’s (2005) ecological model was used as a departure point for this study. The study acknowledges that there are wider, influential factors, within the context of education, which contributes to student success (Hamwey et al., 2019; Koller et al., 2019). The environment in which educational development takes place is fundamental to this success. Bronfenbrenner’s ubiquitous model is constructed as a series of nested circles, with the student at the center (Bronfenbrenner, 2005). The circles closest to the student are the most influential. Bronfenbrenner labeled these circles: the microsystem, the mesosystem, the exosystem, the macrosystem, and the chromo system (Bronfenbrenner, 2005).

Utilizing these five nested structures, the study theorized that the students who formed part of their program were a product of a range of influences (Bronfenbrenner, 2005). It is proposed that in their microsystem, their teachers, parents, peers, partners and siblings, may have the greatest impact. These interactions are uniquely personal. Similarly, the mesosystem captures the interactions between the students’ microsystem, and their lives beyond the educational context. The school developing relationships between partners and parents, and fostering strong skills to support parenting, are likely to influence overall success and development.

The exosystem incorporates those informal social structures, such as the local neighborhood and friendship circles, which contribute to environments that facilitate development (Bronfenbrenner, 2005). In this context, the circle focuses on the young parents and their wider role models. In the macrosystem, the students’ culture, geographic location and socio-economic status often play a significant role in determining their level of engagement and subsequently the degree of success. These factors are proffered as possible marks of influence; several studies have demonstrated that elements such as geographic location and socioeconomic status, may have some impact on educational success (Cooper et al., 2017; Hirschl and Smith, 2019).

Finally, the model considers environmental impact over time, as the major life transition of pregnancy, birth and parenting become fundamental to the young person’s normal life. Bronfenbrenner’s (2005) model refers to this as a chronosystem, with early pregnancy in the context of this study being viewed as part of the timeline of events in both the young parent’s and their child’s lives. Consequently, this ecological model provides a considered focus, with regard to environmental influences. However, it also incorporates developmental processes which the young parents may experience over time. In this context, it is wise to consider the individual, the context, and the developmental outcomes, individually.

For the purpose of this investigation, the Ecological Systems Theory was represented through concentric spheres to highlight the circles of support offered to teenage parents (refer to Figure 1).

Methodology, rationale and target population

The program ran multiple sites, with one of these being selected as a case study in order to obtain both a holistic and in-depth view of how young parents were being re-engaged into education. It was of interest as it presented an authentic context of the program at work. Ethical clearance to study the program was obtained through the state department of education and the university which had oversight over the program. The observation of practice; interviews with educators, students, and other macrosystem stakeholders; and document analysis illustrated a model at work and provided significant insight into how to best accommodate the unique learning profiles of the young parents. In order to facilitate the use of case study research in this exploration, we adopted the definition from Yin (1999), which encapsulates the “intense focus on a single phenomenon within its real-life context” (Yin, 1999, p. 1211). Aligned with this definition, we sought to describe and explore the context and the inner workings of the identified site, in order to help understand and explain how an educational center could be developed to assist young parents re-enter mainstream education. The use of a case study assisted with the capture of explanatory information, detailing processes, procedures, and insight into responses, engagement and perceptions relating to how the center operated (Yin, 1999, 2009). We adopted the interpretivist approach (Crowe et al., 2011), in an attempt to understand individual and shared meaning of the program, while drawing on a more reflective perspective which accommodated the social and contextual environment.

The case study focused on a 2-year operational period of the site, and included student participants, educator perspectives, stakeholder comments, and a perusal of documents and records that were used during this time. The research team had access to all participant groups, with each assigned particular time for dialog and observation. At the outset, the researchers applied for ethics clearance to the nominated university, ensuring that all possible risks to participants were accounted for. Participation in the study was voluntary with each group provided with a full explanatory statement regarding the use of the information they provided. To facilitate a comprehensive view of the program, the team sought to gather multiple forms of evidence, using qualitative methods (interviews, document analysis and observation). This ensured some form of data triangulation, and was an attempt to increase the validity of the study (Crowe et al., 2011). Additionally, the research team was keen to create a holistic perspective of the program by viewing it from a range of angles.

In order to obtain an accurate view of the program, the research team decided to interview varying stakeholders, teaching and support staff, and students. Participation by these individuals was voluntary and they could withdraw at any stage of the interview prior to the data being collated for analysis. Interviews were arranged at mutually convenient times, at the education center site. These interviews were audio recorded, with this provision being indicated on the consent form an explanatory statement that was made available to all participants. The recorded interviews were then transcribed for analysis purposes. The research team read the interview transcripts multiple times in order to identify common themes. Since the interviews were loosely divided into three groups—students, staff and stakeholders the same concepts would become visible through the various stakeholder perceptions.

Situating the case site

The case site in Melbourne’s southeast was located in a local community learning facility, overseen by a Registered Training Organization (RTO). The facility hosted a number of engagement and support programs for at-risk youth with the young parent program situated in an adjacent building. This provided a level of privacy, reduced noise, and space for the necessary equipment while still allowing for easy access for staff and students. Importantly, the facility is located next to a train station and near major bus routes. The student population in the young parent program has a rolling enrolment—students enroll at any time of the year, they may pause their attendance around the birth of their child, and are able to complete their certificates at their own pace (subject to VCAL standards and guidelines). In 2019, the site listed 15 girls enrolled ranging from young teens through to early twenties. While the program was open to young parents of any gender, no young fathers had enrolled.

The case study site is one of several sites of this model of young parent engagement programs, but is the most enduring. The local learning and employment network (LLEN) oversee and manages the various sites. The Program Coordinator works for the LLEN and is a linchpin in the operation of the program. Furthermore, there is a consortium of various youth-orientated organizations that provide funding, resources, and expertise. Importantly, the group also acts as advocates for this marginalized group of young people. In 2019, the Consortium members included representatives from current and future program sites; members of the government funding programs; city officials working in youth and family services and counseling; representatives from the Department of Education and Training Regional Office; representatives from mental health and wellbeing groups; representatives from the university health services; university academics and representatives from the YMCA.

Program overview

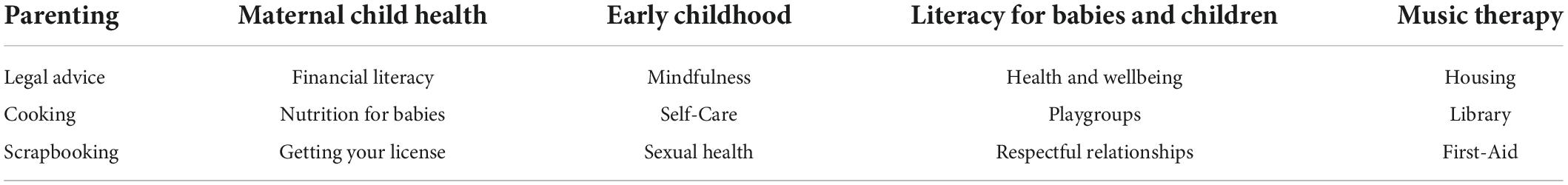

The program supports students to obtain their Year 12 certificate in VCAL as well as a Certificate II or III in their chosen Vocational and Education Training (VET) course. Students attend their VCAL classes 3 days a week at the community learning center in a flexible learning environment with their babies, and their VET courses once a week without their babies. In addition to their Year 12 Certificate, students also learn about parenting skills and literacy for children. Much of the VCAL content and assessments are tailored to further support the learning needs of the young mothers. Each student is in an Individual Learning Plan (ILP) to support them in obtaining their qualifications and “includes consideration of factors such as wellbeing, career planning, parenting, living arrangements, relationships, legal advice, maternal child health, mental health, learning needs, support networks, study history and any other factor specific to each student” (Student Induction Booklet, 2019, p. 4). In 2019, the students’ academic learning was supported by a full-time classroom teacher, a part-time numeracy teacher, and a program coordinator who was also involved in other programs through the community learning center. A list of topic covered has been provided in Table 1. There is also a parental support specialist who runs a focused session once a week and a full-time parent support worker to increase the flexibility of the learning environment.

Table 1. List of topics covered by guest presenters (Student Reference Booklet, 2017, p. 5).

Data analysis

For the purposes of this case study, the researchers were informed by the method suggested by Hill et al. (1997). In this context, the team drew on consensual qualitative research, where the researchers involved arrived at a consensus about the meaning of the data across the sub-groups interviewed as part of this study (Hill et al., 1997). Members of the team brought different perspectives to the collated data, based on their observation, interaction and involvement at the research site as well as from their own professional histories. This method allowed the researchers to capture commonalities and contradictions, revealing interesting perceptions and insight into the program. At the outset, the interviews were transcribed, followed by a close and considered reading. Drawing on the expertise of the research team the data was individually coded, searched and reviewed in order to define the ideas and identify them. Coding occurred alongside the research questions which drove the analysis. The use of semantic codes permitted the research team to present the participant experience in a descriptive manner, and we observed relationships between the groups who were interviewed. Once coding was complete it was possible to then translate these into themes, based on the three research questions. The initial group of provisional themes soon transitioned into a defined set of established themes that were used to address the research questions. Finally, the analysis was developed in relation to the research questions.

Findings

The purpose of this study was to determine factors that contribute to the experiences of young parents within a tailored education program, which sought to re-engage them into education. Additionally, the paper sought to reflect on the accommodation measures that aligned with the changing needs of young parents. In doing so, the study explored the unique characteristics of an alternative education program, which positioned the needs of young parents at the forefront.

The study was directed by the following research questions:

1. What are the factors that contribute to the positive experiences of young parents with a customized educational program, tailored to their needs?

2. How has the program accommodated the changing needs of young parents?

3. What are the unique characteristics of the educational programs which accommodate the needs of young parents?

Research question one: what are the factors that contribute to the positive experiences of young parents with a customized educational program, tailored to their needs?

Some researchers note that the idea of engaging young parents back into education is unsettling for society and “perplexing for schools” (p. #), and accounts for the discomfort young mothers feel when they interact in the real world (Kamp and McSharry, 2018). Referencing a similar Australian program, Kamp and McSharry (2018) maintains that positively recognizing the needs of young parents does more to shift the balance and alter the lens, rather than compelling young parents to be excluded and moved out of the educational landscape. The mere alteration of schedules, spaces and timetables may cause inconvenience and unease (Watson and Vogel, 2017; Kamp and McSharry, 2018; Bakhtiar et al., 2020), but is perhaps what our fluid contemporary society requires. At its heart, research acknowledges that teenage parents are afraid and this fear often presents in different ways in their interaction, behavior and speech (Dickinson and Joe, 2010). Society may interpret this as untoward or inappropriate; however, research reports consistently enunciate the view that teenage parents require the sponsorship and assistance offered by nurturing groups and individuals, in order to find their places within their communities (Dickinson and Joe, 2010; Jutte et al., 2010).

Prioritizing the care of the individual student

It was evident through the interviews that a strengths-based approach which involved small class sizes that were more understanding of the needs of students, was fundamental to an alternative education program for young parents. In this regard the shared experiences of the participants allowed for effective transition protocols, as young parents were able to share a great deal of camaraderie and commonality. One student commented that:

“I could go to any school, but I feel like it’s more comfortable to be with other mums and stuff. Where you go to a normal school, they all just talk about teenage stuff or whatever, and here I feel like I get along with everyone because they’re all mums and so am I.”

In their report, the SHINE group (Year) supported this view that it was essential to provide an educational system that was comfortable and non-judgmental for young parents. Reporting on a similar young parents’ program in South Australia, the need for a friendly and nurturing culture within the educational environment was viewed as crucial to the advancement of students. Similarly, a New Zealand study noted that the creation of Teen Parents Units (TPUs) improved the educational and life outcomes of young parents by creating spaces where they could thrive, through a re-engagement in education (Kamp and McSharry, 2018). The researchers reported that students had “transformed” and “benefitted” from an easily accessible educational context, for them and their babies. Comparable to the program under review, the TPUs in the New Zealand study were geared toward respecting the position of the young parent, nurturing and caring for their needs and accepting them for who they were. It is evident that successful programs to support the educational initiatives of young parents were successful primarily because of their ability to connect young people in similar circumstances (SmithBattle, 2007; McDonald et al., 2009; Dickinson and Joe, 2010; Bakhtiar et al., 2020). This form of networking of like peers facilitated success and connected individual students to the initiative (Fram, 2005; Stiles, 2005; McLeod et al., 2006; Dickinson and Joe, 2010).

Optimizing the value of the educators

Experienced educators with a background in welfare and wellbeing were viewed as crucial to the program. Educators should ideally possess a wide-ranging skill set, often balancing between teaching and counseling in order to provide appropriately for students. Educators were vital to the success of the program, as it was crucial for them to build strong rapport with the young parents, while maintaining their professional boundaries. A key factor was the consideration of combined skill and knowledge, aligned with temperament and disposition, especially since teaching programs are often interrupted, and unstructured in order to accommodate changing needs. In this regard, one educator acknowledged that:

“….we usually take it slow, we identify what their needs are, what their goals are, what are their challenges? What did they find difficult when they were in mainstream school and why they left and why it didn’t work. And we really try to be mindful of that and cater our program…every single one of them has a separate program. So, it’s catered to their needs and my job is to make sure that I’m very flexible and adaptable to be able to cater to each one’s needs.”

It was evident that flexibility and personalized learning was central to the program. With regard to the disposition and the demeanor of teachers, a student noted that:

“the teachers sit with you and they talk to you. They encourage you to do stuff. It’s really cool.”

Evidently the personality and mindset of the educator and the support are essential to the success of the program and of how participants respond. Professional support, especially, is perceived as a primary factor that facilitates the program’s success (Stiles, 2005). Stiles (2005) notes that educators with a background in childcare, nursing and education will contribute actively to the support of the young parent. They are likely to offer knowledge relating to essential life skills, stress management, nutrition and health (Stiles, 2005). Additionally, a Tasmanian report on teenage parents reflected on “mentors” rather than “educators” within the context of parenting programs (Bakhtiar et al., 2020). In this regard, the researchers mentioned the need for educational staff to recognize the individuality of each participant. As part of their study, they acknowledged that the teenage parents preferred the term “mentor” as it better encapsulated the role of the professional staff in their journeys (Bakhtiar et al., 2020). Similarly, Watson and Vogel (2017) acknowledged the criticality of teacher support as it built resiliency among the teenage parents involved in the program.

The location of the educational center

The location of the young parents’ program was viewed as important to the willingness of young parents to attend and to be engaged in their learning. On school-sites may pose challenges as it may marginalize the young parents, when comparisons with mainstream students in secondary school are likely. Within the context of this study, the selected site was viewed as somewhat ideal, as it was close to public transport, offered students a separate building, and was accessible from several suburbs. One of the invested stakeholders noted that:

“This was seen as a good possible location because of where they’re positioned…it is embedded into the community, I think it’s done that because it’s part of what happens in that organization. They’re very much a community hub, and I think that model is what we want to take to replicate in other areas definitely.”

Reporting on a similar program in Victoria, the Australian Institute of Family Studies (2014) reiterated the need for an appropriate location which would serve the needs of young parents. The geographical location is a significant consideration in a program of this nature, as it should be contextualized within a local area with easy access to resources, appropriate networks and access to transport (Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2014). In order to increase the connectedness of the young parents, the program should be accessible, and within their physical networks. Similarly, a report on parenting programs in the Australian Capital Territory noted the importance of location and positioning of support programs for young parents (Butler, 2015). Butler (2015) implies that situating parenting programs within an appropriate setting is likely to reduce stigma and create greater normality for the parents.

Accessibility to on-site assistance

Moreover, the use of an on-site child-nurse facilitated care for the babies, responding to an essential need of the young parents to be able to have their babies alongside them during their study. An educator noted that:

“The number one would be having their babies with them, that they’re able to come in and still provide the care and be there with their babies and do everything they want to, while still being able to get their education at the same time.”

Furthermore, the effective modeling from staff allowed for students to feel quite supported as young parents, and more holistically as individuals within a vulnerable population. One member of staff summed it up in this way:

“…these young people need a mentor…they’ve got lots of workers but they need just one key worker that does the full 100% advocation…and supports them and mentors them.”

This element of support and care for both the physical and mental health of the teenage parent has been highlighted in research, with calls for programs, such as the current one, to work to overcome the fear of difference and exclusion among young parents (De Jonge, 2001; Fram, 2005; Stiles, 2005; Niven and Dow, 2016). Access to community support and organizations of support added to the skill base of the young parents and gave them vital knowledge relating to their access to help from both governmental and private organizations (Stiles, 2005; McDonald et al., 2009; Dickinson and Joe, 2010). Appropriate facilities such as comfortable chairs for breastfeeding and a bottle warmer, provided physical aspects that fostered wellbeing, thereby assisting involvement in a learning program. Strategic partnerships with key stakeholders also formed a critical aspect of the program as the shared vision of stakeholders contributed to the vision, goals and funding for the program. Stakeholders offered expert opinions, and drew from their respective expert and specialist knowledge in order to enhance the program delivery. Research notes that the strengths of young parent support programs involve high quality facilitation and the provision of appropriate resources (Dickinson and Joe, 2010).

Individual needs

Essentially, programs of this nature become about “individual needs” as each develops and devises strategies and methods that assist them individually. One teacher emphasized that:

“The strategies and the methods that I think work well are just the engagement, having that flexibility, allowing them to choose, having some of the extracurricular activities.”

Research notes that many young parents are drawn to the programs in order to reduce the stigma associated with early pregnancy and to increase their chances of a successful life (De Jonge, 2001; Fram, 2005; SmithBattle, 2007; Niven and Dow, 2016; Watson and Vogel, 2017). Furthermore, juggling the responsibility of parenthood, while attending school and maintaining a social life proves challenging for teenage parents (Stiles, 2005). Therefore, access to parenting programs which provide a range of skills, both academic and maternal, offered teenage parents a much-needed lifeline (Stiles, 2005; SmithBattle, 2006). Butler (2015) maintains that broad programs which consider overall needs work well, but those which focus on specific needs are likely to be of greater benefit to the participating parent. Each teenage parent faces unique challenges, and programs which help them address and manage these position them well for success (Watson and Vogel, 2017).

Research question two: how has the program accommodated the changing needs of young parents?

Flexibility and responsivity

In considering how the program has accommodated the changing needs of young parents, the research team sought to consider the structure and organization of the program. The program has repeatedly been acknowledged as “flexible” to the needs of the students, with educators, students and stakeholders reporting that the fluidity of the program was a significant element. Important to student needs is that the programs start with them, rather than a structured curriculum. Additionally, the young parents straddle different roles, that of parent and student simultaneously—the program had to be cognizant of both these roles. Furthermore, many of the participants were keen to advance their skills and ensure that they were in a stable educational position for themselves and their babies. As such, the program had to wrap around student needs, being more accommodating and adjusting the learning and teaching schedule to suit individual learners. Research and evaluation into support programs for teenage parents zoomed in on similar ideas, as young mothers were keen to improve their skill with providing for their babies, while also improving their educational outcomes (SmithBattle, 2007; McDonald et al., 2009). Flexibility and responsivity was a critical factor contributing to the success of the young parents (Watson and Vogel, 2017).

The success of the program was evident in one young parent’s accolade that:

“I enjoy coming here. I don’t dread it in the morning… It’s welcoming… and you feel this isn’t a classroom. It just feels like a place you come and learn.”

Evidently, the dynamic of the classroom is an important fundamental element of the learning environment, as the reward of being among like-minded and empathetic peers is supportive to young parents. Additionally, participants feel supported by the co-curricular elements that support their roles as parents. One respondent commented on her involvement in a mothering segment:

“…they do a lot of things…it’s really cool.”

Previous research with support programs for young parents revealed similar values, and findings, with young mothers feeling supported, sustained and heard (Dickinson and Joe, 2010; Watson and Vogel, 2017). A flexible program which emphasized the needs of young parents appeared to have greater success (Fram, 2005; Stiles, 2005; McDonald et al., 2009; Dickinson and Joe, 2010). Networking and relationship forming were particularly relevant for teenage parents experiencing a range of challenges, including the care of an infant with a disability and social isolation from family circles (Fram, 2005; Stiles, 2005).

Co-curricular activities and support networks

Add-on activities which create normality and encourage the young parent to become involved in life outside the classroom is viewed as essential to their wellbeing:

“we go to the pools, or we go to the beach…or the zoo…stuff like that…” These programs included art workshops, scrapbooking and music lessons, to assist students to gain a holistic view of parenting and of their own lives. Young parents without adequate information and external support may experience marginalization and disconnection (De Jonge, 2001; Stiles, 2005; Niven and Dow, 2016). Therefore, programs of this nature are central to their education and social engagement (McLeod et al., 2006; McDonald et al., 2009). Drawing together a range of service providers who are responsive to the needs and circumstances of the young parents, are likely to enhance positive outcomes and reduce disadvantage (Butler, 2015).

Furthermore, preparing the young parent for a work life was seen as crucial to their learning and equipping. A young parent referenced the “opportunities” she was given since joining the program, and that she appreciated the “information about organizations…that help us with housing and food…” Young parents are likely to experience anxiety over the days that lay ahead, so enabling them through a provision of links and networks is important to the cohesive functioning of the program. A key stakeholder reflected on the program needs, acknowledging that a “totally different model was needed.” In this instance, the need for “early childhood development specialists,” and their expertise was seen as critical for success. Support networks for young parents facilitated discussion of common fears, participation in activities and generally acting as a progressive spur (De Jonge, 2001; SmithBattle, 2007; Niven and Dow, 2016). Young parent education programs provide opportunities for interaction, while equipping them with much-needed information for their lives outside the educational context (De Jonge, 2001; Stiles, 2005; McDonald et al., 2009; Dickinson and Joe, 2010).

Staff collaboration

In this regard, raising the “level of care to the parents and the babies,” was viewed as an integral element of the program’s success. Issues of wellbeing were viewed as central to the teaching and learning program, with one educator noting that:

“It’s all about the process and if that’s in place, everything will run smoothly.”

However, educators acknowledged that they had to “wear different hats” as they taught and assisted students through their learning. Teamwork and collaboration among the educators were also an important feature of the teaching network, as one individual was not seen as responding or working independently. The sharing of resources and “managing the program as a team” was viewed as an important factor for the staff.

Some staff acknowledged that appropriate resources were essential to the success of programs of this nature. They also intimated that parenting support provided through the co-curricular agenda was “amazing” because “it’s all about role modeling what is appropriate.” These programs worked collectively to “set the student up not to fail, but … setting them up for the real world.” Additionally, physical resources like larger spaces to accommodate prams and other equipment for the infants, alongside kitchen and toilet facilities were viewed as essential features of a well-functioning program. Other resources like staffing, literacy and numeracy support and co-curricular activities were also prioritized as important for program efficacy.

Bakhtiar et al. (2020) note that creating collaborations between agencies of support and the educational centre positions the educational initiatives better. Connection, communication and sharing knowledge and resources is elemental to the success of education programs for young parents. In this context, the collaboration of various consortium members, drawn from different agencies from across the state, link service providers and educational organizations, who would proactively consider ways to better accommodate the young mothers. Sharing ground and communicating regularly in this manner directly involves stakeholders, and reduces the potential for marginalization of the young parent (Asheer et al., 2014; Bakhtiar et al., 2020).

Research question three: what are the unique characteristics of the educational programs which accommodate the needs of young parents?

Personalized learning

Learning and teaching programs which accommodate the needs of young parents are unique in themselves, however, the research team was mindful of the individual elements that distinguished the program from mainstream teaching. In this regard, students noted the “comfort” and “familiarity” of sharing a learning space with other young parents who were empathetic and sympathetic to their needs and circumstances. Additionally, the personalized nature of the program, as one student jestingly described it, as “you have a teacher in your face all the time,” was an important feature which facilitated individualized instruction. However, students often thrived working at a pace that was comfortable to their needs, without the rigidity of “you have to do this and you have to do that.”

The elements of “choice…if you want to do your work, you can do your work, but if you don’t, then that’s on you if you don’t finish.” In this regard an adaptable and adjustable learning program was crucial to the needs of the students.

Individualized programs are better positioned for success as they are likely to meet the unique needs of individual young parents (National Research Council, 2004; Butler, 2015; Watson and Vogel, 2017). Young mothers are often motivated to succeed since they want to create a better future for themselves and their child, so in this context, encouraging them on individually helps them overcome hurdles and gives them courage to persevere (Watson and Vogel, 2017). Watson and Vogel (2017) in their American study of teenage mothers reflected that pregnancy sometimes acts as the spur for some students, transforming them from fearful to confident, as they realize so much more is at stake. Personalized instruction, within a supportive and nurturing environment, is more likely to increase the educational outcomes of young parents (National Research Council, 2004).

Staff dispositions

Additionally, staff dispositions and temperament are also fundamental to the success of programs of this nature as students feel more connected with them as individuals rather than teachers. Teachers with patient dispositions, who “sit with you and they talk to you. they encourage you to do stuff… it’s really good…” are also fundamental to student success. Teachers noted that they felt the need to be:

“understanding of their situations, you have to allow for that. You have to adjust for that, so you’ve got to be really flexible and be very understanding and try different strategies that work for different people because they’re all so different. They all have different challenges. They all have different moods/they all have different personalities.”

One staff member noted that, “…the teacher does make a big difference…have boundaries and still support.” Fundamentally, this meant that staff had to be sensitive to student needs while keeping them on task to continue to meet curricular demands.

Consequently, the personality and disposition of the educator is a principal feature of programs of this nature. Research validates this view, underscoring the essential role of the educator, and the social and academic links they provide (Fram, 2005; Watson and Vogel, 2017; Bakhtiar et al., 2020). Maintaining professionalism while still being cognizant and sensitive to individual parent needs was a primary element of successful support programs for teenage parents (Fram, 2005; Bakhtiar et al., 2020). Bakhtiar et al. (2020) note that it is important for educators and participants to establish rapport, and for the educator to create a connection with the young parent. Likewise, Fram (2005) notes that young parents within support groups often possess reduced social and economic capital, and risk marginalization without help. Programs like the one under review, and others of a similar ilk around the world, provided appropriate support through connectedness and bonding relationships (Fram, 2005; Clarke, 2015; Bakhtiar et al., 2020). One study noted that students within parenting programs for teenage parents, expressed the need for teachers to play a “pseudo-parent” role, setting high expectations, while being aware of their unique challenges (Watson and Vogel, 2017).

Nurturing environment

The learning and teaching space is viewed as “not really a school. It’s more of a mum’s group to me.” Consequently, it is evident that the nurturing nature of the environment and the individuals involved in those circles, are important factors, optimizing the success of these programs. Likewise, the ability to have their babies with them during the class time, was an important comfort and security factor for the students. One young parent noted that, “it’s good that you can bring your baby to school with you.” The young parents’ education program has facilities for babies, which assists in the nurturing of the student, and assist with their wellbeing, as their baby is within reach, and can be attended to during the academic day.

Accommodating students who are keen to straddle dual roles in the classroom is certainly unique to the program. Incorporating mothering and parenting workshops and creating networks for the young parent to support them even after the educational term has been completed, is elemental to their success as human beings (Fram, 2005; SmithBattle, 2007). These primary needs are corroborated in similar research studies, which acknowledge that teenage parents are at risk of depression unless they become part of nurturing circles where they are trusted and accepted (De Jonge, 2001; SmithBattle, 2007; McDonald et al., 2009; Dickinson and Joe, 2010; Niven and Dow, 2016). Genuinely welcoming spaces which prioritized the needs of the young parent often paved the way for successful outcomes (Fram, 2005; SmithBattle, 2006).

The program is also unique in that it accommodates the whole student—their wellbeing is paramount. An educator noted that:

“It’s their whole wellbeing. It’s good for them all round, to be able to feel part of something, to be able to further their education, to be connected to other people their own age in the same situation…they do need a lot of support and if they can be with people that are in the same situation of their same age in a learning environment, then they will thrive.”

This is consistent with similar studies which highlight the benefits for young mothers, should they have access to supportive programs (Fram, 2005; Dickinson and Joe, 2010; Niven and Dow, 2016), such as the one under study. One study pointed out the “how” of the program matters (Asheer et al., 2014). Staff in programs for young parents should be comfortable discussing challenging issues with the young parents and be sensitive to their vulnerability (Asheer et al., 2014). They also had to possess some degree of passion for the work they did, and ideally, possess specialized skill to align with the program model (Asheer et al., 2014).

Curricular modifications

The curriculum adjustments and modifications are also an important consideration, as these need to be adaptable and resilient, constantly being reshaped to suit different student needs. One teacher commented that:

“So their curriculum is—we keep it at the minimum that they are required to do to complete the certificate, so that’s it’s not overwhelming.”

The adaptability of the curriculum is crucial especially since young parents may have time off from school to attend to their babies needs including doctors’ appointments and post-natal care appointments. Teachers recognize that the young parents want “routines” and “a bit of structure,” but they also want it to be “relaxed” to suit their changing circumstances.

Another teacher noted that after taking care of their babies’ needs, the students are:

“…. very tired, so being so flexible is really good for them to just to be able to work at their own pace…there’s not so much pressure.”

Research supports the premise that a supportive and responsive curriculum is central to the success of educational programs for young parents (Watson and Vogel, 2017). Smaller class sizes which are more accommodating of student needs, having daycare services alongside formal educational programs, and the individualization of the pace of such programs, are lauded as key curricular modifications for success (Watson and Vogel, 2017). Additionally, accommodating student needs through flexibility with attendance, providing alternate pathways as appropriate and modifying their curriculum, is pivotal to the success of teenage parents in support programs (Watson and Vogel, 2017).

Implications: establishing the RAFT framework for teenage parents

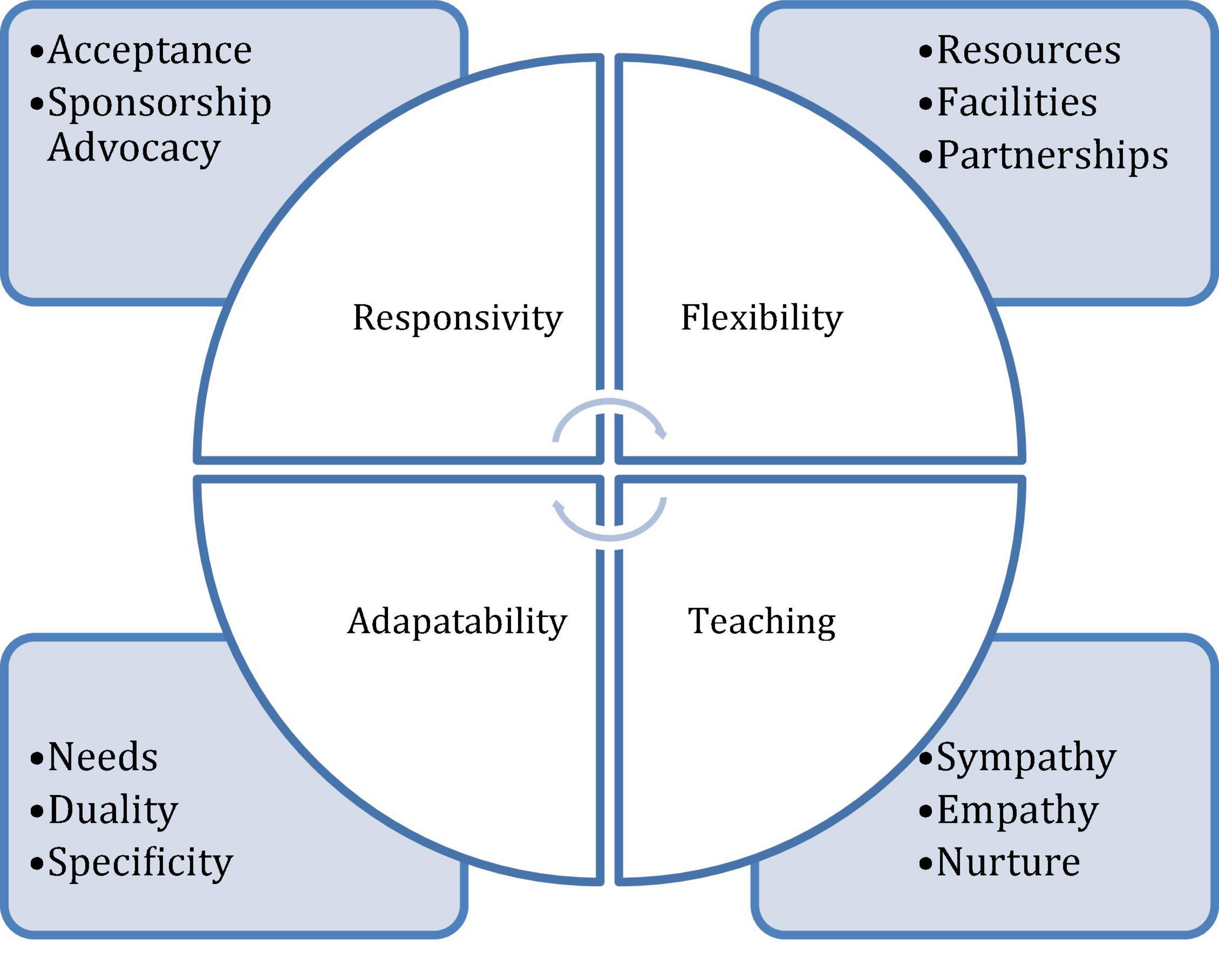

In concluding this project, the researchers were keen to provide a framework which they hope will inform the crafting and development of programs to accommodate marginalized youth as they navigate challenges (Refer to Figure 2). Informed by the ecological theory used to position the research, the yielded framework considers contextually specific and more universal factors which could be used as a platform, indeed a raft, to navigate the gap between difference and commonality. Teenage parents may be one of the most vulnerable populations in our societies and advocating for them and their success is a collective responsibility. In drawing together the research contained in this manuscript, the research team amalgamated the ideas, arriving at the RAFT framework. Each element is discussed below as an implication of the project and highlights the research studies and reports which support each.

Responsivity

Research cited in this study illustrate that educational programs should ideally draw in students who are marginalized and accommodate their needs. Being responsive to the needs of a vulnerable population is central to a developed society (Watson and Vogel, 2017; Kamp and McSharry, 2018; Bakhtiar et al., 2020). Responsivity encapsulates acceptance, sponsorship and advocacy. Additionally, the nurture of an educational program, which responds to individual needs, positions students for success and assists them to provide more appropriately for themselves and their babies. Preventing social failure rests at the core of these programs.

Adaptability

Young parents as students differ from their mainstream counterparts and therefore require a more adaptable and malleable teaching and learning program. In this regard, resources and facilities are not restricted to just teaching and learning programs, but are likely to draw on the wider supports of the community. Strategic partnerships with community groups and governmental organizations should be deftly incorporated into their learning programs, creating an adapted and modified curriculum that is better suited to their unique needs (Stiles, 2005; McDonald et al., 2009; Dickinson and Joe, 2010).

Flexibility

Education programs for young parents should be flexible and pliable, accommodating changing schedules, unexpected absence, and being sensitive to the ever-altering needs of the student. Initiatives to support young parents who are still at school should demonstrate an understanding of the participants’ dual roles, as they juggle parenthood and their academic workloads (Stiles, 2005; SmithBattle, 2006; Watson and Vogel, 2017). Flexible programs which consistently assume two lenses, one which is holistic, and the other which is specific to individual needs, will result in greater success (Butler, 2015).

Teaching

In this context, inclusivity is facilitated largely through the educators, the support staff and the networks which maintain programs for marginalized young people. The demeanor and investment of the educators within young parent support programs, according to research, are pivotal to its success. Research demonstrates that it is not just academic support that is sought in this context, but other forms of sympathy, empathy and nurturing (Stiles, 2005). Staff, and supportive service providers, who acknowledge the individual journeys of each student are likely to foster greater resiliency among the young parents in their care (Watson and Vogel, 2017; Bakhtiar et al., 2020).

Limitations of the study

The framework devised as a product of this research was based on a single case study. While the model is replicable, contextual factors for individual care programs and initiatives for young parents, should be borne in mind.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Monash University. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Asheer, S. M. P. H., Berger, A. P. D., Meckstroth, A. M. P. P., Kisker, E. P. D., and Keating, B. M. P. P. (2014). Engaging pregnant and parenting teens: early challenges and lessons learned from the evaluation of adolescent pregnancy prevention approaches. J. Adolesc. Health 54, S84–S91. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.019

Australian Institute of Family Studies (2014). Connecting Young Parents. Melbourne, Vic: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW] (2020). Australia’s Children: A Web Report. Darlinghurst NSW: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Bakhtiar, A., te Riele, K., and Sutton, G. (2020). Supporting Expecting and Parenting Teens (SEPT) Trial—Independent Evaluation. Hobart TAS: University of Tasmania. Report for the Peter Underwood Centre for Educational Attainment.

Basch, C. E. (2011). Teen pregnancy and the achievement gap among urban minority youth. J. Sch. Health 81, 614–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00635.x

Beauchamp, T. (2020). Improving Outcomes for Young Parents and their Children: Effective Policy Settings and Program Approaches. Tokyo: APO.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (2005). Making Human Beings Human, Biological Perspectives on Human Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Butler, K. (2015). Parenting Programs in the ACT. Report Created for: Families. Lyneham: Families ACT.

Carlson, D. L. (2016). Challenges and transformations: childbearing and changes in teens’ educational aspirations and expectations. J. Youth Stud. 19, 705–724.

Clarke, J. (2015). It’s not all doom and gloom for teenage mothers – exploring the factors that contribute to positive outcomes. Int. J. Adolescence Youth 20, 470–484. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2013.804424

Cooper, G., Baglin, J., and Strathdee, R. (2017). Geographic location a significant predictor of students’ intentions to attend university. Bentley WA: National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education.

Crowe, S., Cresswell, K., Robertson, A., Huby, G., Avery, A. J., and Sheikh, A. (2011). The case study approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 11:100. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

De Jonge, A. (2001). Support for teenage mothers: a qualitative study into the views of women about the support they received as teenage mothers. J. Adv. Nurs. 36, 49–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01942.x

Department of Social Services (2017). Try, Test and Learn Fund, Career Readiness for Young Parents. Australian Capital Territory: Department of Social Services.

Dickinson, P., and Joe, T. (2010). Strengthening young mothers : a qualitative evaluation of a pilot support group program. Youth Stud. Australia 29, 35–44.

Ellis-Sloan, K. (2018). “Personal decisions, responsible mothering: unpicking key decisions made by young mothers,” in Re/assembling the Pregnant and Parenting Teenager: Narratives from the Field(s), 1st Edn, eds A. Kamp and M. McSharry (Bern: Peter Lang AG), 243–268.

Fram, M. S. (2005). “It’s Just Not All Teenage Moms”: diversity, support, and relationship in family services. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 75, 507–517. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.4.507

Gaudie, J., Mitrou, F., Lawrence, D., Stanley, F. J., Silburn, S. R., and Zubrick, S. R. (2010). Antecedents of teenage pregnancy from a 14-year follow-up study using data linkage. BMC Public Health 10:63. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-63

Hamwey, M., Allen, L., Hay, M., and Varpio, L. (2019). Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological model of human development: applications for health professions education. Acad. Med. 94, 1621–1621. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002822

Hindin-Miller, J. (2018). “What if becoming a teenage parent saved your life?” in Re/Assembling the Pregnant and Parenting Teenager: Narratives From the Field, eds A. Kamp and M. McSharry (Oxford: Peter Lang Publishers).

Hill, C. E., Thompson, B. J., and Williams, E. N. (1997). A guide to conducting consensual qualitative research. Counseling Psychol. 25, 517–572. doi: 10.1177/0011000097254001

Hirschl, N., and Smith, C. M. (2019). Well placed: The geography of opportunity and high school effects on college attendance. Res. High. Educ. doi: 10.1007/s11162-020-09599-4

Jutte, D., Roos, N., Brownell, M., Briggs, G., MacWilliam, L., and Roos, L. (2010). The ripples of adolescent motherhood: social, educational, and medical outcomes for children of teen and prior teen mothers. Acad. Pediatr. 10, 293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.06.008

Kamp, A., and McSharry, M. (2018). Re/Assembling the pregnant and parenting teenager. Oxford: International Academic Publishers.

Koller, S. H., Paludo, S. D. S., and de Morais, N. A. (2019). Ecological Engagement: Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Method to Study Human Development. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG.

Lin, C. J., Nowalk, M. P., Ncube, C. N., Aaraj, Y. A. L., Warshel, M., and South-Paul, J. E. (2019). Long-term outcomes for teen mothers who participated in a mentoring program to prevent repeat teen pregnancy. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 111, 296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2018.10.014

Marino, J. L., Lewis, L. N., Bateson, D., Hickey, M., and Skinner, S. (2016). Teenage mothers. Aust. Fam. Phys. 45, 712–717.

McDonald, L., Conrad, T., Fairtlough, A., Fletcher, J., Green, L., Moore, L., et al. (2009). An evaluation of a groupwork intervention for teenage mothers and their families. Child Family Soc. Work 14, 45–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2008.00580.x

McLeod, A., Baker, D., and Black, M. (2006). Investigating the nature of formal social support provision for young mothers in a city in the North West of England. Health Soc. Care Commun. 14, 453–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00625.x

National Research Council (2004). Engaging Schools: Fostering High School Students’ Motivation to Learn. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Niven, G., and Dow, A. (2016). Health visitors’ perceptions and experiences of teenage mothers’ support groups: a qualitative study. J. Health Visit. 4, 258–263. doi: 10.12968/johv.2016.4.5.258

Pinzon, J. L., and Jones, V. F. (2012). Care of adolescent parents and their children. Pediatrics 130, e1743–e1756. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2879

Price-Robertson, R. (2010). Supporting young parents. (CAFCA Practice Sheet). Melbourne, VIC: Child Family Community Australia, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Rowen, W. D., Shaw-Perry, M., and Rager, R. (2005). Essential components of a mentoring program for pregnant and parenting teens. Am. J. Health Stud. 20:225.

Roxas, K. (2008). Keepin’ it real and relevant: providing a culturally responsive education to pregnant and parenting teens. Multicultural Educ. 15:2.

SmithBattle, L. (2005). Teenage mothers at age 30. West J. Nurs. Res. 27, 831–850. doi: 10.1177/0193945905278190

SmithBattle, L. (2006). Helping teen mothers succeed. J. School Nursing 22, 130–135. doi: 10.1177/10598405060220030201

SmithBattle, L. (2007). “I Wanna Have a Good Future”: teen Mothers’ rise in educational aspirations, competing demands, and limited school support. Youth Soc. 38, 348–371. doi: 10.1177/0044118x06287962

SmithBattle, L. (2018). “Teen mothering in the United States: fertile ground for shifting the paradigm,” in Re/assembling the Pregnant and Parenting Teenager: Narratives from the Field(s), 1st Edn, eds A. Kamp and M. McSharry (Bern: Peter Lang AG), 243–268.

Stiles, A. S. (2005). Parenting needs, goals, & strategies of adolescent mothers. MCN Am. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 30, 327–333. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200509000-00011

Student Induction Booklet (2019). Information supplied anecdotally from student coordinator at the Young Parents Education Program. Melbourne, VIC.

Student Reference Booklet (2017). Student Material Prepared by Course Leaders. Available online at: https://www.foundation.vic.edu.au/courses-programs/youth/young-parents-ypep/

Watson, L. L., and Vogel, L. R. (2017). Educational resiliency in teen mothers. Cogent Educ. 4:1276009. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2016.1276009

Yin, R. K. (1999). Enhancing the quality of case studies in health services research. Health Serv. Res. 34(5 Pt 2), 1209–1224.

Keywords: teenage parents, marginalised adolescents, learning support, student diversity, individualized learning, personalized support

Citation: Subban P, Round P, Fuqua M and Rennie J (2022) Creating a R.A.F.T to engage teenage parents back into education: A case study. Front. Educ. 7:852393. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.852393

Received: 11 January 2022; Accepted: 28 June 2022;

Published: 12 September 2022.

Edited by:

Joanne Banks, Trinity College Dublin, IrelandReviewed by:

Maria Elena Ramos-Tovar, Autonomous University of Nuevo León, MexicoJose Manuel Salum Tome, Temuco Catholic University, Chile

Copyright © 2022 Subban, Round, Fuqua and Rennie. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pearl Subban, cGVhcmwuc3ViYmFuQG1vbmFzaC5lZHU=

Pearl Subban

Pearl Subban Penny Round

Penny Round