- 1Department of English, FPT University, Can Tho, Vietnam

- 2School of Foreign Languages, Can Tho University, Can Tho, Vietnam

- 3School of Education, Can Tho University, Can Tho, Vietnam

Fears of COVID-19 covered humans on earth quickly since the first appearance of Coronavirus in Wuhan in 2019. Consequently, online learning has been deployed widely to ensure the continuity of education in the context of the pandemic. The mixed-method study was conducted to examine the extent of fears Vietnamese students’ perceived as well as their learning adaptability, using the Fears of COVID-19 Pandemic (FCV19) scale and Adaptability scale as research instruments. Data was analyzed relied on Mean statistics from SPSS22, combined with Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to examine the influences of fears of COVID-19 on students’ online learning adaptability. The results triangulated with qualitative data from open-ended questions showed that students were moderately afraid of the COVID-19 pandemic but had a high level of adaptability in online learning. Additionally, fears of COVID-19 also had little impact on students’ online learning adaptability. Instead, students showed off some other fears preventing their virtual learning, including (1) fears of wasting time and money for a shoddy online education, (2) fears of loneliness and laziness, (3) fears of distracting factors when learning online, and (4) fears of lacking learning materials.

Introduction

COVID-19 has become one of the phobias worldwide since its first appearance in Wuhan, China, at the end of 2019. It is believed to cause most depression, anxiety, fears of death, losing loved ones, and post-traumatic disorder (Keyes et al., 2014). 2020 was when the United States and most European countries like the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Portugal encountered the hazardous time fighting against the pandemic; meanwhile, in Asia in 2021, led by India with the records of death tolls and infections, followed by many other Asian countries like the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Switching to online education indeed becomes a must wherever there are infected cases. Accordingly, online education is implemented in different forms, including synchronous and asynchronous, or other tutoring models, including in-person, e-mail, virtual tutoring (Hangout/Google Meet), and WhatsApp (Pérez-Jorge et al., 2018, 2020). In Vietnam, educators also deploy online teaching on social networks such as Zalo and Facebook (Van and Thi, 2021b). Unfortunately, students are considered the most vulnerable due to facing strict social distancing periods and studying in the limit of learning resources (Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al., 2020). Some other hindrance factors discussed include the lack of social interaction, cost and access to the Internet, technological issues, or even students’ worriment about the quality of online education (Van and Thi, 2021a). When fears become one of the frequent common emotions in the time of the pandemic, there are plenty of studies conducted to investigate the impacts of fears of COVID-19 on different groups of people and living conditions, for example, medical staff (Urooj et al., 2020), patients with underlying medical conditions (Guven et al., 2020; Colomer-Lahiguera et al., 2021), senior citizens (De Leo and Trabucchi, 2020), prisoners (Pattavina and Palmieri, 2020; Johnson et al., 2021). Whether fears of COVID-19 impose any influences on students’ online learning adaptability has intrigued stakeholders for seeking the answers.

The idea of this study arose when Ho Chi Minh City and other localities in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam were sinking in the huge wave of COVID-19 infected cases and death tolls. The pandemic started in late the academic year and became more severe during the summertime of 2021. It was coincident with summer vacation; however, to most high school students, this was a revision time for National High School Examination and the summer semester for university students. By the same token, a plethora of Vietnamese students have encountered the second time of online learning. Researching the correlations between fears of COVID-19 and students’ online learning adaptability help to gain more insight into the psychological characteristics of students in the region. It may also help to propose necessary interventions from stakeholders for students’ normal psychological recovery in the post-COVID-19 pandemic.

Theoretical Background

Fears of COVID-19 Pandemic

The Oxford online dictionary defines “fears” as the bad feelings someone has when being in danger or frightened. In the educational environment, fears may cause significant psychological distress, fears of vagueness, and uncertainty, which could directly impose unpleasant effects on overall learning, academic achievement, and the general well-being of students (Elsharkawy and Abdelaziz, 2021). Similarly, Arpaci et al. (2020) considered fears a multifaceted factor, often one of the most crucial underlying factors of conceded mental health and well-being. During the COVID-19 pandemic, fears become one of the most frequent emotions that may spread much faster from one to another than the disease itself (Arpaci et al., 2020).

Online Learning in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic

The outbreak of a fatal and infectious disease named COVID-19 has caused the closure of most educational institutions worldwide. To maintain the continuity of education in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, online learning was implemented as no more than an option, but a necessity (Singh and Thurman, 2019), even when some underdeveloped and developing nations have been unready. For instance, Pakistanis education pointed out the undesired learning satisfaction among students, whose online learning conditions were restricted not only in technical issues but also monetary issues (Adnan and Anwar, 2020).

In Vietnam, as one of the developing countries in Southeast Asia, online learning has been implemented to meet the demand of the global educational trend; however, it also imposes a wide range of difficulties for the authorities and educators. With regard to the online learning barriers in the current context, most Vietnamese students, especially students in the Mekong Delta, considered that limited social interaction had caused a lot of challenges for them when learning online (Van and Thi, 2021a,b). Subsequently, the so-called cost and access to the Internet and some technical issues have prevented students from becoming successful online learners. These challenges were followed by learners’ skepticism about learning quality when most of them thought that they paid more than what they knew and could not understand as effectively as when they were on campus.

Students’ Adaptability

Adaptability is understood as appropriate cognitive, behavioral, and/or affective adjustment in the face of uncertainty and novelty (Martin et al., 2013). The American Psychological Association’s (APA) has officially defined adaptability as “the capacity to make appropriate responses to changed or changing situations; the ability to modify or adjust one’s behavior in meeting different circumstances or different people” (VandenBos, 2007). Prior studies highlighted the vital role of adaptability in constructing students’ engagement and achievements (Martin et al., 2013; Collie et al., 2017), reducing students’ failure dynamics (Martin et al., 2015). Holliman et al. (2018) especially emphasized the connection between adaptability and students’ engagement and long-term achievement. As a matter of fact, adaptability plays an essential role in students’ positive development (Martin et al., 2021).

Research Methodology

Research Aims

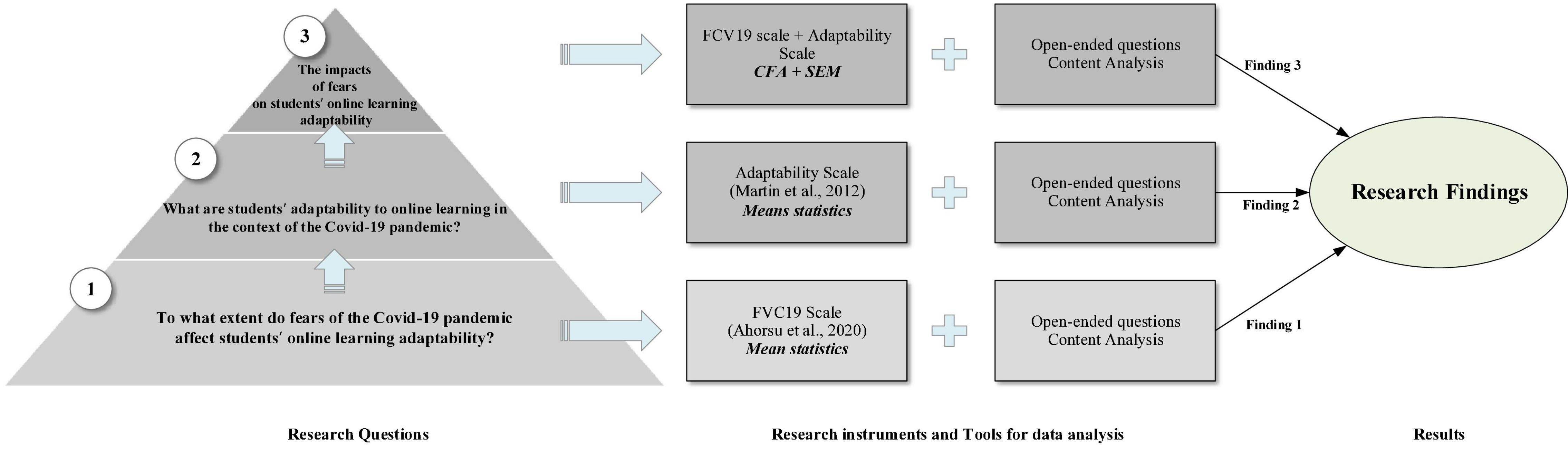

The study was conducted to measure the levels of fear among students about the COVID 19 pandemic. We also wanted to assess Vietnamese students’ adaptability to online learning in the context of the pandemic. Ultimately, we aimed to investigate whether such fears of COVID-19 affect their adaptability to online learning or not.

To address these aims, the following questions were posed:

1. To what extent do students perceive fears of the COVID-19 pandemic?

2. What are students’ adaptability levels to online learning in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic?

3. To what extent do fears of the COVID-19 pandemic affect students’ online learning adaptability?

Research Design

A mixed-method study was designed to find out answers to research questions. Accordingly, data will be collected in parallel, analyzed separately, and merged to provide a complete understanding of research problems (Creswell and Creswell, 2017). Mixed-method studies are also preferred since they provide a deeper and broader understanding of the phenomenon than the study taken only with a qualitative or quantitative approach (Hurmerinta-Peltomäki and Nummela, 2006).

In this study, the FCV19 Scale and Adaptability Scale were adapted to confirm the extent of students’ fears of the pandemic and their adaptability to online learning, with the first use of Exploratory Factor Analyses. Then, we employed statistics on means of these scales and ran CFA and SEM to examine the influences of FCV19 on students’ adaptability in online learning. Also, in this study, we wanted to get insights into students’ explanations for their rating with items in the survey; open-ended questions were added to call for students’ answers. To ensure the validity and reliability of answers from open-ended questions, we followed Brislin’s model of translation (Brislin, 1986), which is widely accepted and used to translate quantitative instruments but is time-consuming (Lopez et al., 2008). Accordingly, one researcher took the responsibility to translate the answers from Vietnamese to English. The second researcher would then back-translate the results from English into Vietnamese. The third researcher compared both versions to check accuracy and consistency. Any discrepancies would be negotiated before figuring out the final answers.

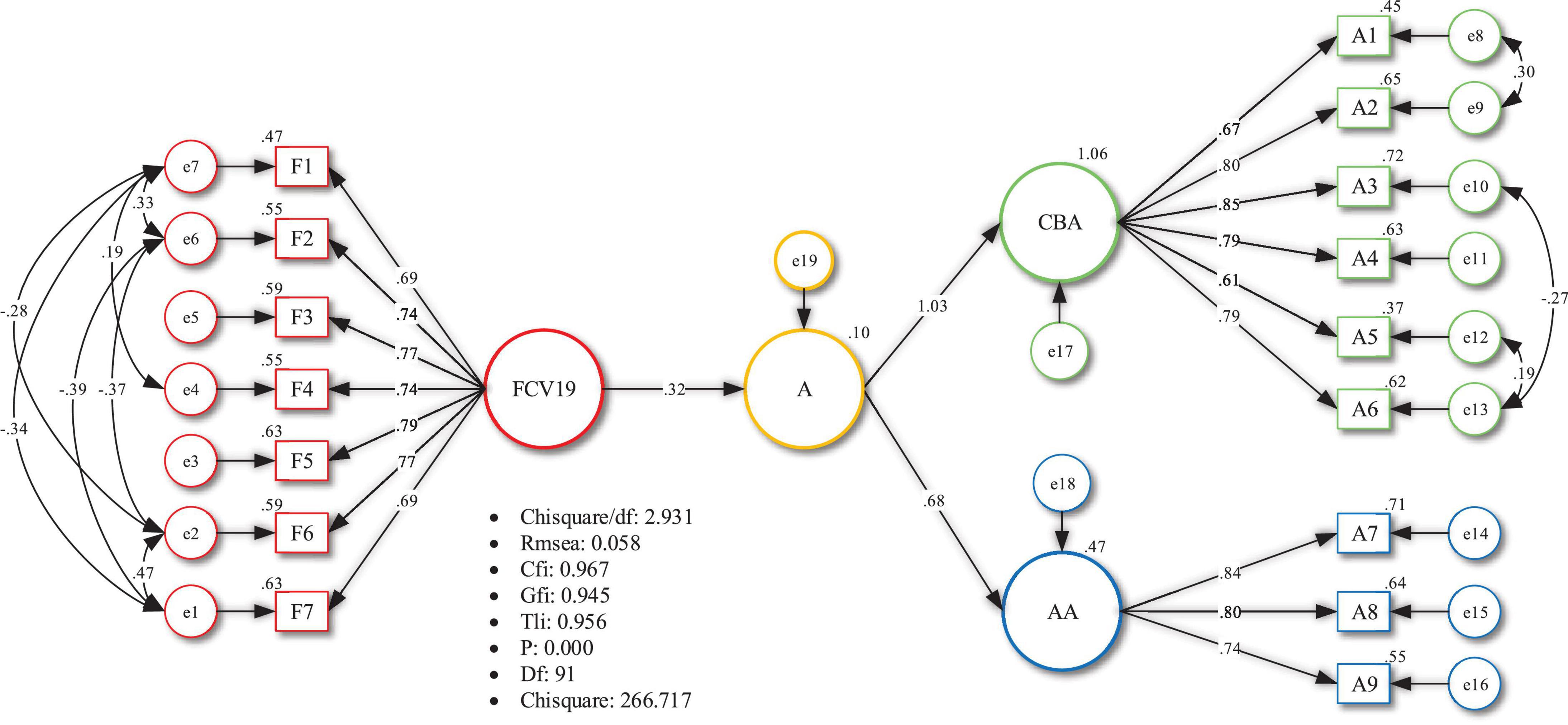

Both quantitative and qualitative findings were triangulated to write up the results. The research model is illustrated in Figure 1.

Research Instruments

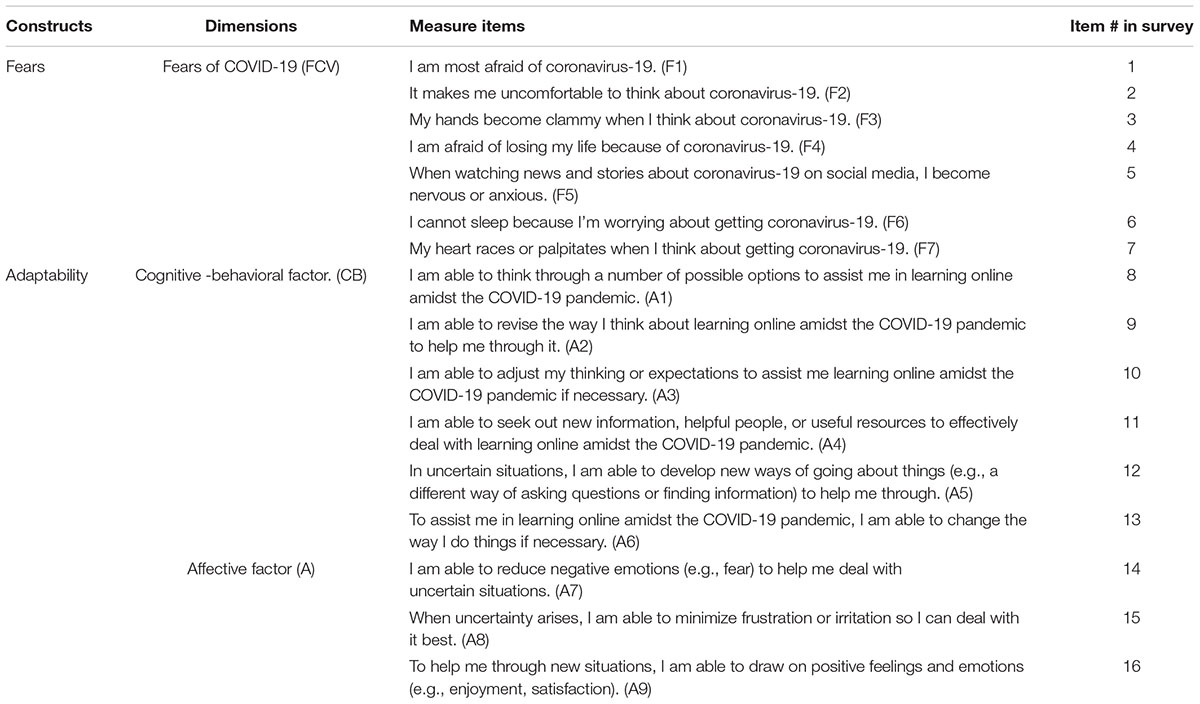

To solve the research issues, we adapted the FCV19 scale (Ahorsu et al., 2020) and Adaptability scale (Martin et al., 2012) as the research instruments. According to Natalia and Syakurah (2021), FCV19 Scales is useful to evaluate the fear of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Adaptability Scale (Martin et al., 2013) is also a comprehensive measurement for assessing students’ cognitive, behavioral, and emotional adaptability (Holliman et al., 2021).

There are sixteen items that help measure learners’ fears of the pandemic and their online learning adaptability in the current context. A Vietnamese version was created to help learners familiarize themselves with the questionnaire before launching it to collect data on Google Form in September 2021. Table A1 displays all the variables measured for the study’s primary constructs. Participants were asked to choose the extent they agree with each statement, ranging from (1) Completely disagree to (5) Completely agree.

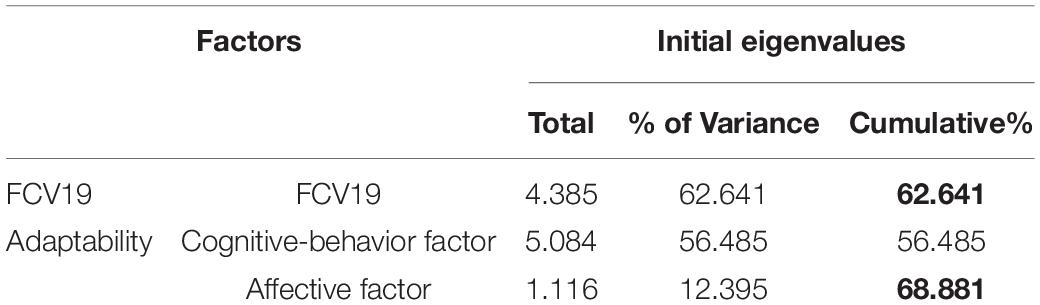

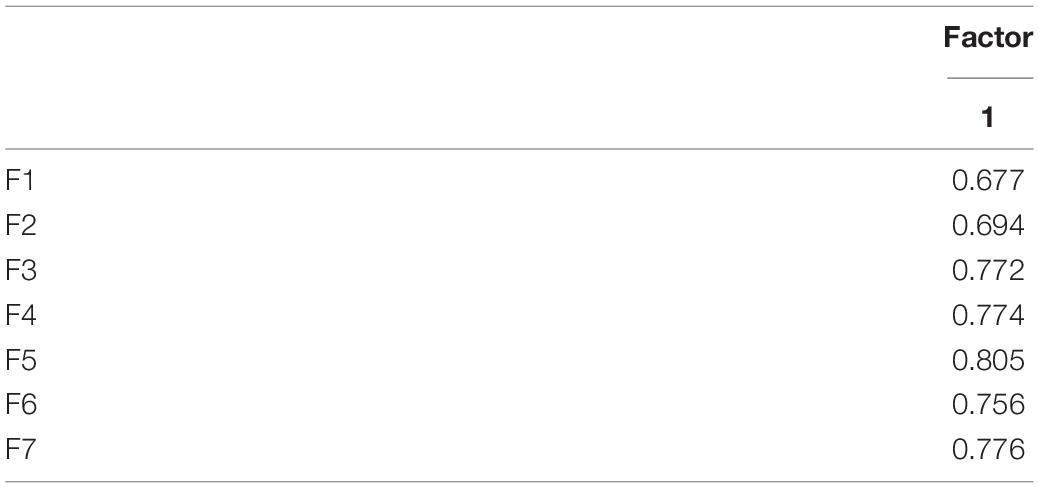

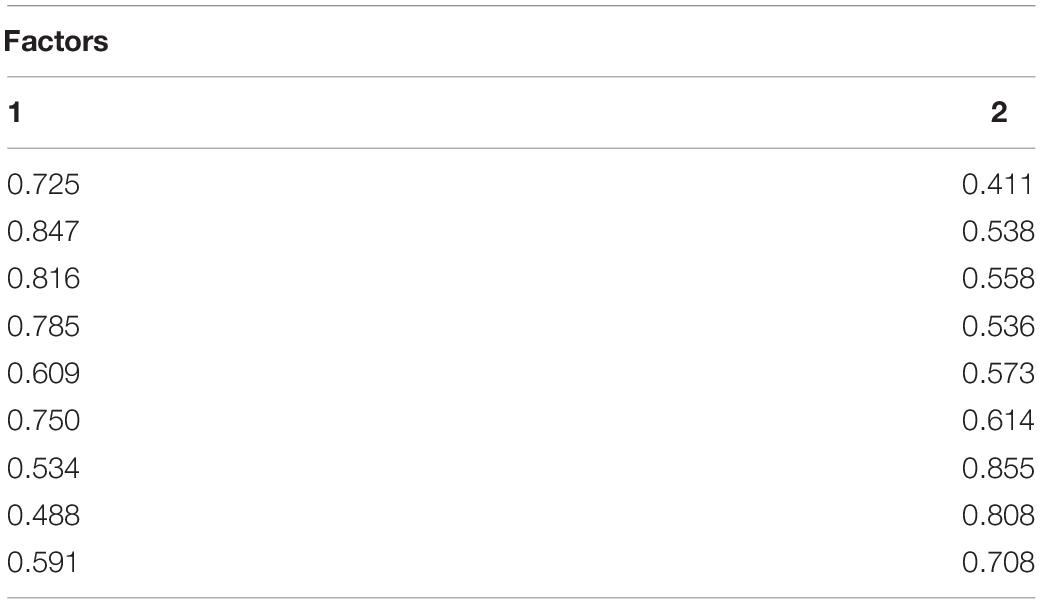

An Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) with Principle Axis Factoring and Promax rotation was used in the study. The results showed that FCV19 was a unidimensional factor when the seven items were loaded into only one group, with Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) at 0.878 and the initial eigenvalues were greater than 1. The significant level of Bartlett’s was at 0.000, proving all the variables were correlated. They were accounted for 62.64 of all variance. According to Hair et al. (2006): “… in the social sciences, where information is often less precise, it is not uncommon to consider a solution that accounts for 60% of the total variance (and in some cases even less) as to satisfactory” (p. 104).

Simultaneously, a similar EFA was applied for the Adaptability scales, with KMO at 0.900, a significant Bartlett’s test level at 0.000, and qualified initial eigenvalues (> 1). Noticeably, nine items were loaded into two groups of factors, namely the Cognitive-behavioral factor and the Affective factor, precisely the same as the result of Martin et al.’s (2012) study. Details about the results of EFA for these scales were displayed in Tables 1–3 as follows.

Participants

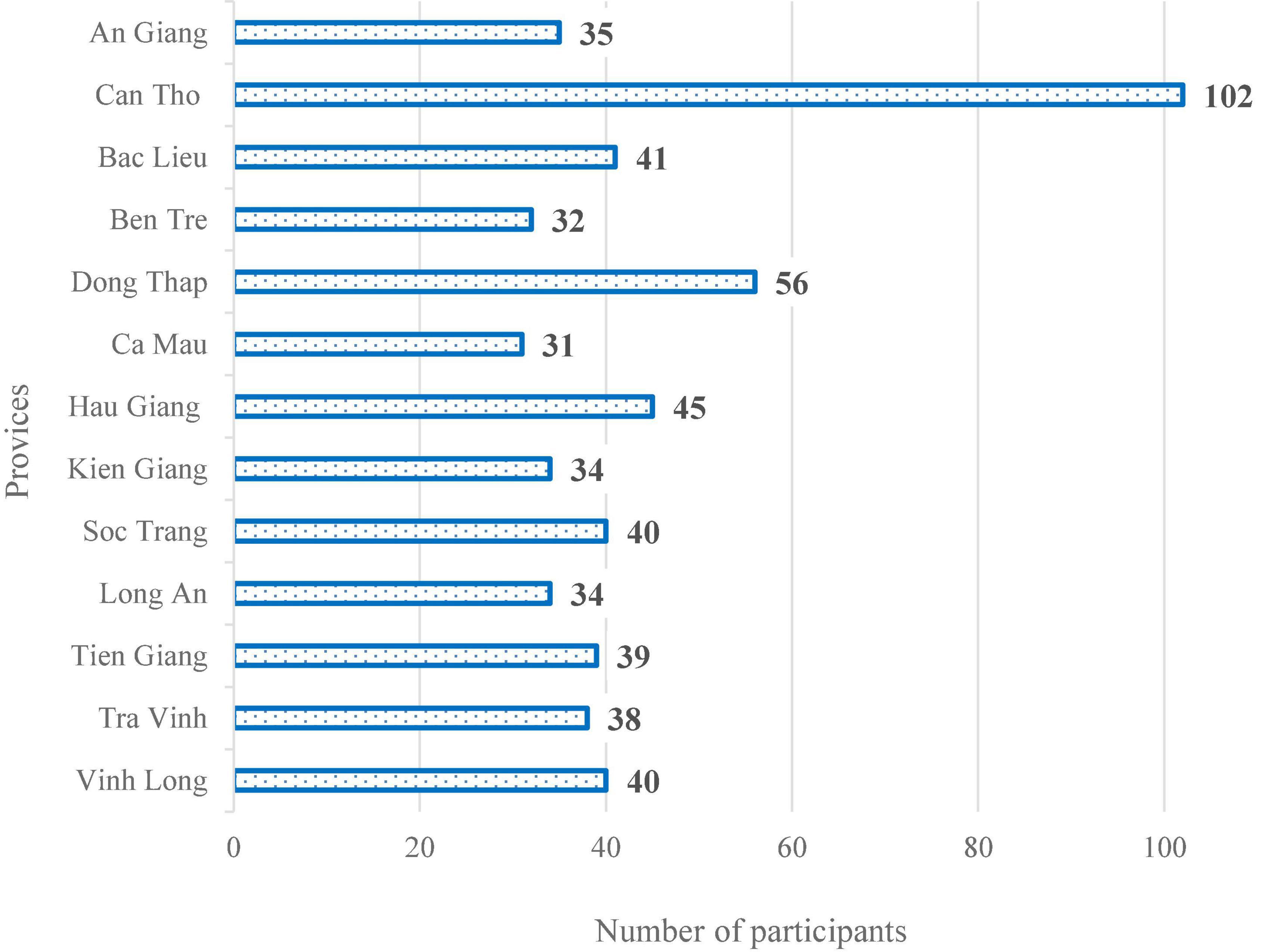

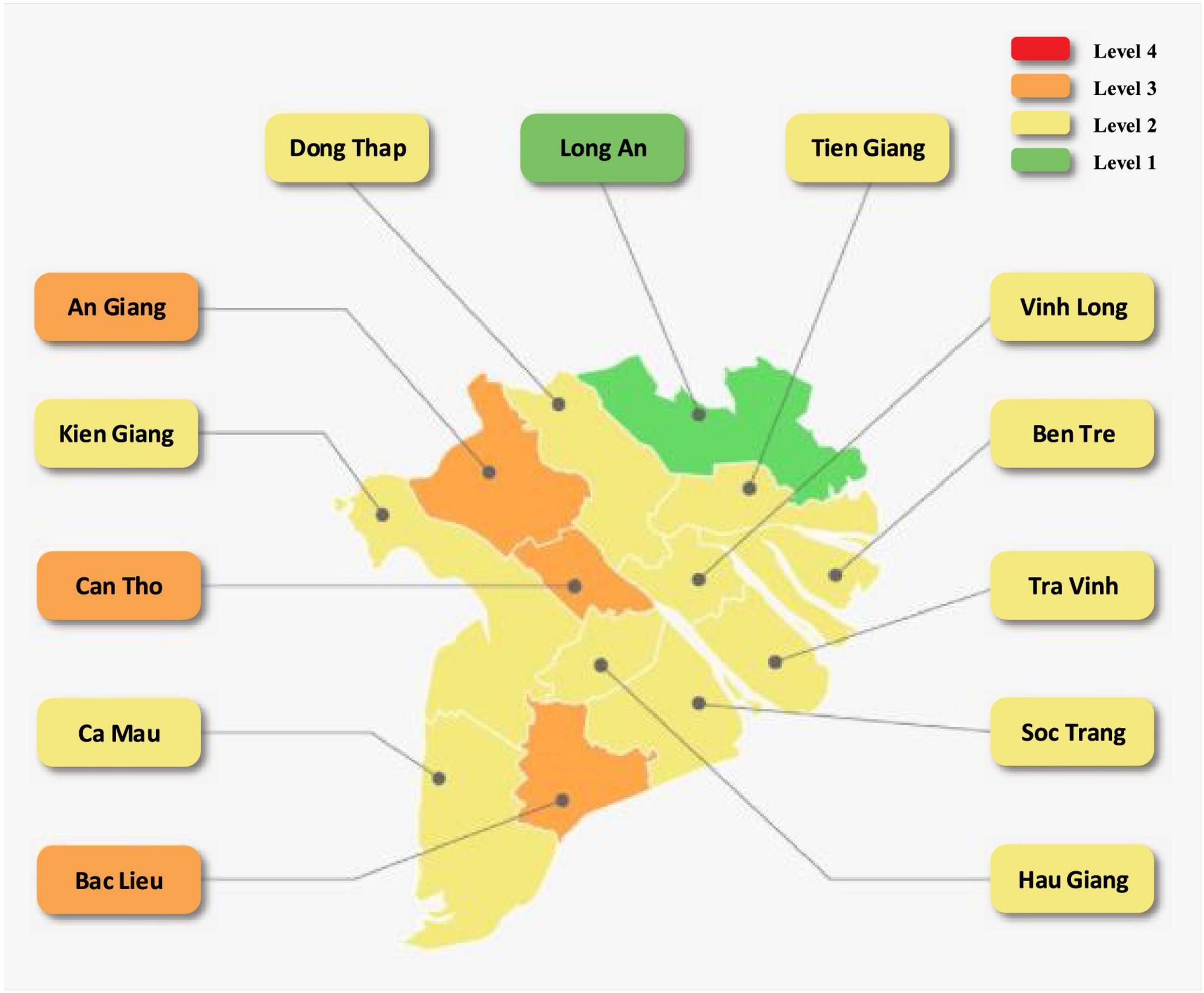

567 university students in the Mekong Delta, who were learning online due to the COVID-19 pandemic, joined in answering a web-based questionnaire. They are from 18 to 24 years old, including 199 male students (35.1%) and 368 female students (64.9%). Most of them came back to their hometown, and a few were stuck in the university regions. They are living in 13 provinces in the Mekong Delta. According to statistics on the locals with COVID-19 infected cases, there are 503 students (87.1%) living in the pandemic areas, only 73 students (12.9%) being in non-COVID-19 regions. Details about distribution of participants and the COVID-19 risk levels by provinces will be illustrated in Figures 2,3.

Findings

Students’ Perceived Fears of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Results From Quantitative Analysis

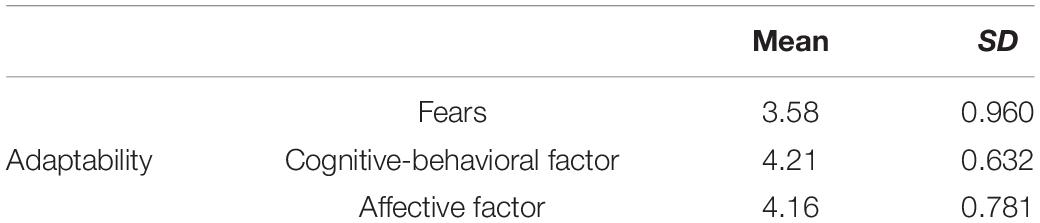

To evaluate the extent of fears students perceived regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, the mean statistics (Table 4) showed a moderate level (M = 3.58, SD = 0.84). It means that students were quite afraid of the pandemic.

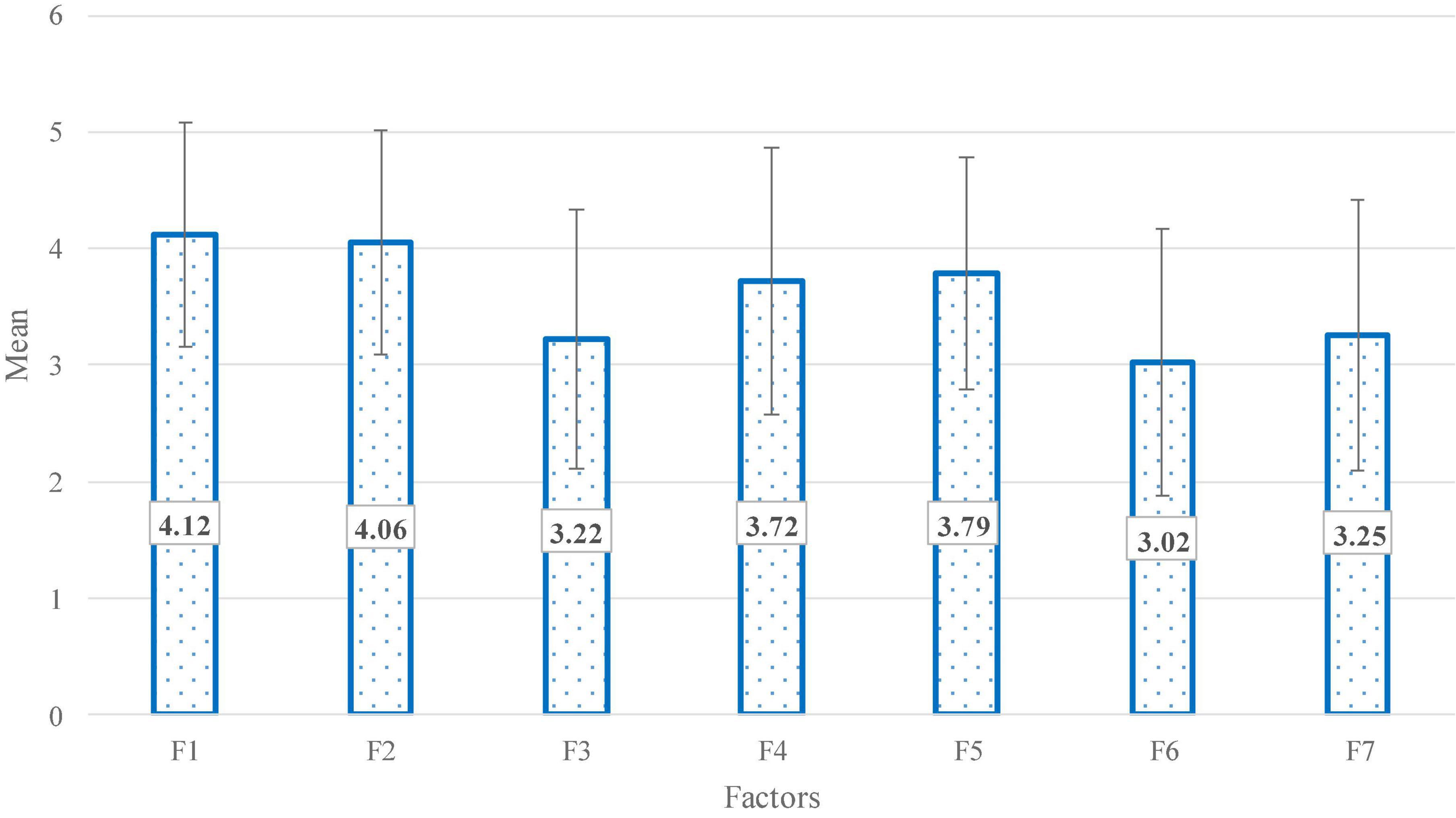

Specifically, among the seven items constructing the FCV19 scale, F1 (I am most afraid of coronavirus-19) and F2 (It makes me uncomfortable to think about coronavirus-19) got the highest levels (M = 4.12, SD = 0.96, and M = 4.06, SD = 0.963, respectively). F3 (My hands become clammy when I think about coronavirus-19), F6 (I cannot sleep because I’m worrying about getting coronavirus-19), and F7 (My heart races or palpitates when I think about getting coronavirus-19) were rated just above the neutral level (Figure 4), which mean that students were afraid of the COVID-19 but not extreme toward these issues.

When participants were invited to write short answers for the open-ended question: “How can you describe your feeling when there are more and more COVID-19 positive cases in Vietnam?,” among 567 responses recorded (100%), almost all participants (98%) revealed their worriment about the pandemic, except for 12 respondents (2%) who said that they were still OK, just normal, or calmed down enough with the COVID-19 news. Statistics on the frequencies of words that appeared in their answers showed that there were 495 times students mentioned the word “worry,” 212 times of “fears,” 77 times of “confused,” 43 times of “sad,” 22 times of “insecure,” and 6 times of “bored.” It can be seen that the COVID-19 seemed to cover uncertain living conditions to almost all students. This section will be continued by some typical reasons for students’ fears of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Lateness in Graduation Time

It sounded like a paradox when educational institutions implemented online learning is to ensure students’ continuity of education and their time to graduate. The results showed that 74/567 (13.1%) were terrified of late graduation from the university. Specifically, some said that they were seniors and some experimental courses required them to attend the traditional learning form. Their fears of the COVID-19, to be more precise, are their phobias when they become passive in the changing learning condition.

“I am scared of the pandemic, especially when it lengthens the time I graduate. I cannot finish practicum courses, which makes me feel hard to eat well and sleep well.” said Respondent #37.

A smaller number of 53/567 (9.3%) students thought they might fail the exams because they could not concentrate on their study. They were bombarded with information about the numbers of people dying due to the COVID-19 in Vietnam and the world; even the increasing number of infected cases in their regions. Losing concentration leads students to risks of failures and lateness in their graduation plan.

“Sometimes, when we are learning and there is suddenly an announcement about an increase in cases, I feel distracted a lot. It will be worse if my friends bring the story to share with my teacher and other classmates, the lesson will be interrupted and we cannot re-focus to study.” said respondent #5.

“I am trying to stay home and learn online, but I continuously wonder when the locals come and grasp us to the isolation area. I know that people can be positive with Corona easily. I cannot concentrate on learning whenever I think of it. What if I cannot keep up with my friends and fail the course? When will I graduate?” said Respondent #5.

Infection and Death

112/567 (19.8%) students said that they were afraid of being positive for the virus when more and more people around them were infected. Respondent #69 wrote: “I do not know when I am positive with Coronavirus, though I try to follow the government policies to stay home during the quarantine period.” Similarly, Respondents #1, #91, and #355 said that: “I am afraid of losing my life because of the COVID.” Twelve other students showed their expectation not to lose anyone due to the pandemic, resulting from the fact that they have witnessed a lot of stories about people who died and the sorrowfulness that their families suffered. All depicted a very blue picture that became a phobia for everyone on earth.

“I am still young, and I have so many things to do in the future. I do not want to end my life due to Coronavirus.” said Respondent #466.

“I saw a lot of videos on Facebook about families in Ho Chi Minh City; just in a few days, they lost their father, their mother, and they cannot see them at the last second. A lot of children become innocent orphans. I feel blue about it. I cannot imagine what will happen to me in the future.” said Respondent #77.

Students’ Online Learning Adaptability

Results From the Quantitative Analysis

Students’ online learning adaptability was evaluated through its mean values. As shown in Table 4, the results indicated that students have high adaptability in learning online in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, not only in Cognitive-behavior (M = 4.21, SD = 0.632) but also in Affective aspects (M = 4.19, SD = 0.781). Noticeably, as can be seen in Figure 5, all means of factors in the scales fluctuated from 4.17 to 4.25, testifying that students agree with the survey items. More precisely, they can adapt very well to a changing learning condition.

Students’ Voice About Their Adaptability

When answering questions regarding students’ FCV19 and students’ adaptability, 64/567 (11.4%) students believed that Coronavirus’s existence was not a simple issue, but it will challenge humans for a long time. Therefore, learning to adapt to the pandemic becomes a must to help people feel better. It is surprising to see a strong sense of responsibility and self-discipline from students that can form the so-called “students’ solid mental preparation” and “students’ strong belief in the governmental policies.”

Students’ Solid Mental Preparation in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic

142/567 (25%) students joining the survey said they were scared of the pandemic; however, they recognized the importance of learning. They know how to adapt to reality and balance their mental phobia with their responsibilities while and after the pandemic. 132/567 (23.2%) students said they found information about the virus, including the common symptoms if they were accidentally positive with, how to protect themselves, how to care for themselves, and how to take care of their family members these days. All proved the fact that students had known how to confront the epidemic. They are not passive and weak to be attacked by the virus.

Students’ Strong Belief in the Governmental Policies

97/567 (17.1%) students said they were worried about the pandemic, but it was not much because the Vietnamese government has implemented the right policies that help to protect everyone. The problem is how individuals strictly follow those directions to protect themselves and the whole community. 155/567 (27.3%) students confidently claimed that they obeyed every demand from their local authority, like joining 5K instruction, taking national vaccination plan, following Directives numbers 15 and 16 during social distancing periods. As a fact of the matter, they all said that they were protected well by the government, and they had no reasons to worry about the COVID-19 longer. These claims sometimes showed their innocence, but in general, proved students’ steady state of mind in the fight against the COVID. Since then, they felt more secure to study online in the context of the pandemic.

“…I think the more I fear, the more unstable I will be. This will make me more worried. With the instructions given by the state and everyone doing as well as now, we will win the pandemic soon; everything will return to normal. Always thinking positively also greatly contributes to avoiding the fear of the Corona pandemic.” said respondent #366.

“To deal with Coronavirus, I think obeying the government’s directives well will reduce the spread and fear.” said Respondent #14.

“I feel that our government has implemented many correct directives to prevent the epidemic, so I have nothing to worry about. I always study in a comfortable posture without worrying; I also try to limit leaving the house when not necessary to help the disease not spread much.” said Respondent #106.

The Impact of Fears of COVID-19 Pandemic on Students’ Online Learning Adaptability

Results From the Quantitative Analysis

Measurement Model Testing

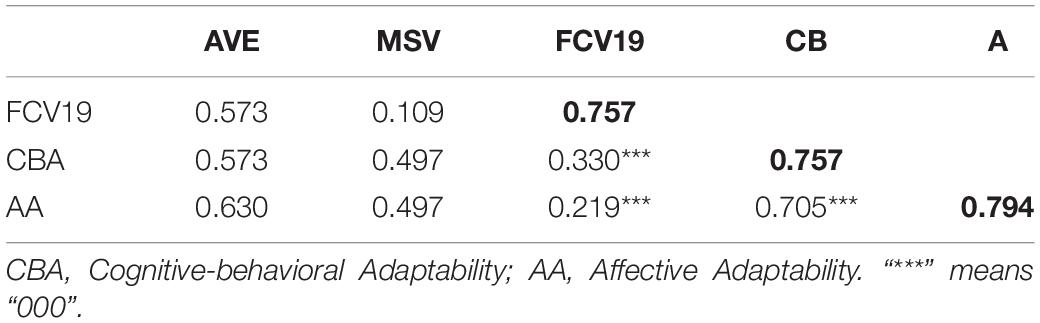

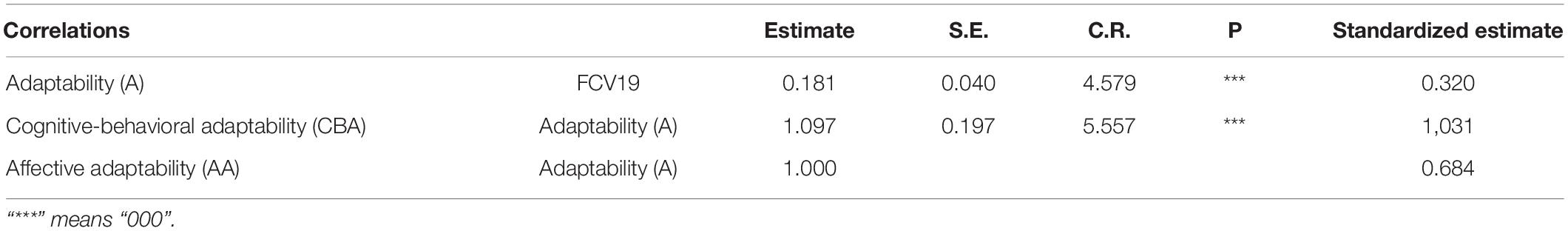

Evaluating the measurement model is initial in every SEM process. Three main criteria were used to assess the model, including the Reliability, Composite Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) (Nunnally, 1978; Hair et al., 2006). Table 5 shows that Cronbach’s alpha is above 0.7, confirming the strong reliability of all measures. CR fluctuates from 0.836 to 0.903, which exceeds the recommended value (0.7) (Hair et al., 2006). The AVE value for all constructs is greater than 0.5, confirming the latent model variables’ confidence and validity. The discriminant validity of the measurement model (Table 6) was assessed based on the evaluation of whether the correlation and coefficient among factors are different from 1; and comparing the square root of AVE, which must be higher than the correlation between one construct and the others (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Figure 6 will display the structural model results.

As can be seen in Table 7, using the 95% confidence standard, the sig of the FCV19 affecting Cognitive-behavioral Adaptability (CBA) and Affective Adaptability (AA) is equal to 0.000, so these relationships are all significant. It can conclude that FCV19 has influenced participants’ online learning adaptability (A).

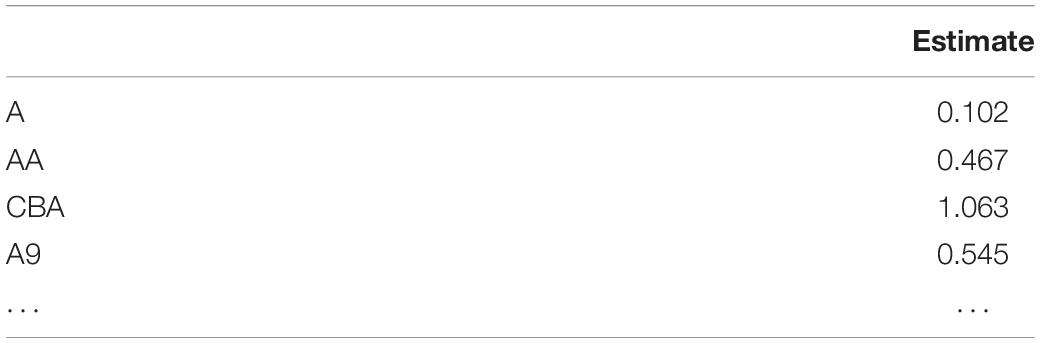

Specifically, Table 8 showed that the R-squared value of Adaptability (A) is 0.102, which mean that FCV19 has the levels of impact at 10.2% on Adaptability. To conclude, FCV19 merely explains 10.2% its influence on learners’ adaptability within the context of pandemic.

Qualitative Results About the Impacts of Fears of COVID-19 Pandemic and Students’ Online Learning Adaptability

The results after qualitative analysis indicated that FCV19 did not really scatter students’ online learning adaptability. It is only a minor factor that governs adaptability and especially, it is a mediator to a series of other influencing factors for students’ online learning.

“Currently, Corona has become more familiar to my study, which means it doesn’t dominate my study more. Being at home during quarantine and lockdown periods makes me feel very cramped, so I prefer to go to school. But I have no more option but learning online. In the past, I might have been late to school because of the erratic weather at noon, but when I study online, I am never late. In the past, I might not be able to concentrate in class because I did not have time to drink coffee or sleep enough, and I had to go back and forth many times, making me feel tired. Now I can balance my eating, sleeping, and learning during the quarantine period. After all, Corona is scary, but I don’t want it to mess up all the order in my life in a senseless way.” said Respondent #139.

“…FCV19 impacts my online learning, but just a little! Because in many situations, people also need to learn and adapt.” said Respondent #329.

Other fears related to COVID-19 influencing on students’ online learning adaptability can be mentioned as: (1) Fears of Time and money consuming with a shoddy online education, (2) Fears of loneliness and laziness when learning online, (3) Fears of distracting factors when learning online, and (4) Fears of lacking learning materials.

Time and Money Consuming With a Shoddy Online Education

To begin with, 94/567 (16.6%) students complained that the teaching quality is not worth the amount of money their parents invested in their studies now. 42/567 (7.4%) students firmly concluded that learning online is just a waste of time and money.

Concerning money earned in the time of the pandemic, it had pushed a tremendous strain on families’ financial burden. When following directive No. 16 of the Vietnamese government, millions of people had to leave their work. Therefore, when the school fee is on the rise, many students tend to be upset and wonder why they have to pay more when they do not use any facilities from the university.

“I’m petrified of the epidemic. If it is still happening for a long time, our economy is exhausted. There is no money to pay the tuition fee. Now, the tuition fee increases, who can stand it?” said Respondent #247.

“I believe FCV19 dominates my study a lot. I do not know when the pandemic ends, and I can come back to my school to study. There are many reasons that we must go to school, but we cannot. Especially in this period, my family cannot earn money, but we have to spend a lot on our daily meals, housing, and school fee. High tuition really makes me confused and worried so much” said Respondent #409.

“Studying at home makes me dominated. I feel very depressed and uninterested, like going to school. Learning online costs electricity (laptop, phone, Wi-Fi, etc.), yet I still have to pay the full tuition while the school saves it?” said Respondent #480.

Some students were fed up with being charged a lot by learning online because they had to prepare laptops, computers, or smartphones, and the Internet connection that cost a lot of money from their parents in a susceptible period. Those are their true fears about the pandemic, they all believed.

Poor Online Teaching Quality

Up to 20 students claimed that they did not believe in the quality of online teaching. Learning online did not provide enough knowledge about the subject (Respondents #198, #202, and # 218).

“I have always had doubts about the quality of online teaching. I feel that online assessment is just something to deal with grades” said Respondent #7.

“COVID-19 has influenced a lot on my study because I cannot go to school in a practical way. If studying online, how can I have enough knowledge and practice to pass the exam and complete the graduation course?” said respondent #198.

“…the quality of online teaching is not as good as offline, so I really hope the school will postpone the next semester until everything is under control.” said respondent #5.

Students’ Fears of Loneliness and Laziness When Learning Online

Being mentally affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, some students find themselves alone when learning in the virtual environment. They admitted that online learning do not bring to learners social interaction factors. They cannot exchange information with their friends and teachers naturally. Consequently, students found it boring and were fed up with online learning. 28/567 (4.9%) students admitted that they were lazier when locked at home and studying online. All urged them to their dream of coming back to traditional education.

“… Yes. The epidemic affects both my spiritual and academic life. Social distancing makes it impossible for me to exchange information, communicate and have fun with friends. Thereby, it makes my life boring and indirectly affecting the spirit of learning online.” said Respondent #555.

“Students are restricted from group discussions. Sitting for many hours in front of the computer screen makes our body tired, causes eye disease, and it is also difficult to remember the lesson content.” said respondent #374.

Students’ Fears of Distracting Factors When Learning Online

44/567 (7.8%) students said they could not concentrate on studying when they were learning at home. Finding out no motivation in learning from a separate place with their friends and teachers makes them “feel bored,” and they cannot stay focused when being bombarded with a lot of housework, noise, and their threat to be falling behind their friends.

“The biggest influence is the study space. I feel uncomfortable when learning at home. It makes my study stagnant, interrupted, and I always feel hard to re-concentrate on my study.” said Respondent #30.

Students’ Fears of Lacking Learning Resources

71/567 (12.5%) students admitted the inconveniences of online learning materials. Some said that they have to work with poor quality E-books, and the number of reference books was also inadequate.

“I find it difficult to go to the photocopier to have printed books. I cannot look at e-books and take part in the lesson on Google Meet simultaneously. My phone can be broken if online learning continues taking place.” said Respondent #344.

Discussion and Conclusion

Reports on Vietnamese Students’ Fears of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Their Online Learning Adaptability

The findings indicated Vietnamese students’ moderate level of fears of the COVID-19 pandemic (M = 3.58, SD = 0.96) and their high level of adaptability (M = 4.19, SD = 0.62) in learning online, based on the adaptation of the two research instruments, namely the FCV19 Scale (Ahorsu et al., 2020) and the Adaptability Scale (Martin et al., 2012). In addition, results from the qualitative analysis help clarify reasons students were scared of the pandemic and how they exposed their strong sense of adaptability in the context of the pandemic.

Concerning Vietnamese students’ fears of the COVID-19 pandemic, most participants in this study agreed that they were most afraid of the pandemic (F1, M = 4.12, SD = 0.960), which made them feel uncomfortable to think about the Coronavirus (F2, M = 4.06, SD = 0.963). These findings proved humans’ commonsense when the pandemic has been threatening anyone’s life since 2019. Though many students have not witnessed the consequences of the pandemic in their current place of living, they have still been afraid of it through news and other updated information from the Internet. Nevertheless, students have rated just above average for other items of the FCV19 questionnaire; those are explained as items expressing different extreme levels of people’s fears about the virus. Specifically, students almost approved the idea F5 (M = 3.79, SD = 0.996) that when watching news and stories about the pandemic on social media, they become nervous or anxious. Responses from the open-ended question also supported that statement when students felt blue whenever they heard reports about the number of people dying due to the COVID-19 or pictures of severe cases requiring ECMO and ventilator support. Therefore, students feared losing their lives because of Coronavirus (M = 3.72, SD = 1.145). Students disagree with three physical reactions: F3, F6, and F7; more precisely, when students were asked whether they felt clammy when thinking of the Coronavirus, or whether they could not sleep because of the pandemic, or their hearts race or palpitate when thinking about getting Coronavirus. It can be explained that at the time this study was conducted, there were not many infected cases in the region, and therefore students were not living in the center of the pandemic. Their voting would be, of course, different from those working in medical staff (Urooj et al., 2020) or high levels of fear from those with underlying medical conditions (Guven et al., 2020; Colomer-Lahiguera et al., 2021). It contributes to explaining the discrepancies in people’s psychological responses in different situations. Moreover, the current study results, which were implemented on young adults aged 18–24, showed lower levels of fear than De Leo and Trabucchi (2020)’s results, which mainly surveyed fears of COVID-19 from the elderly. This helps hypothesize whether concerns about the COVID-19 increase with age, which will be a good premise for further research.

In addition, answers from the open-ended questions showed the two reasons students felt scared of the pandemic. Many explanations supported well for the quantitative results, like students were afraid of losing their lives and being positive with the Coronavirus. Another reason for their fears, being different from the FCV19 scale, was students’ fears of lateness in their graduation.

Regarding the high level of students’ online learning adaptability (M = 4.19, SD = 0.62), they almost recognized the importance of learning to face an acute and prolonged illness like the COVID-19. Diverse explanations were found on their high awareness about the pandemic and their strong belief in their local policies. Just following all demands from the state strictly, students confidently claimed that they could protect themselves and other people effectively. This research finding was compatible with Elsharkawy and Abdelaziz (2021) when testifying that “…more knowledge and certainty regarding COVID-19 will relieve students’ fears and worries about the disease and support their ability to adapt to any secondary effects in their lives.” Under VandenBos’s (2007) definition, Vietnamese students entirely had the capacity to make appropriate responses to changing situations.

The Impact of Fears of COVID-19 on Students’ Online Learning Adaptability

The quantitative result from SEM displayed the fact that fears had little impact on students’ online learning adaptability. Specifically, the FCV19 scale explained 10.2% of its influence on students’ online learning adaptability. Therefore, the current study contributes to the literature another factor distracting students’ virtual education. Moreover, a significant different value-adding to this research context was that this study generated the additional four other kinds of fears emerging from the fears of COVID-19 pandemic (FCV19) that dominated students’ online learning adaptability, including (1) fears of wasting time and money for a shoddy online education, (2) fears of loneliness and laziness, (3) fears of distracting factors when learning online, and (4) fears of lacking the learning materials. This coincidence was compatible with Van and Thi (2021b) regarding factors hindering online learning in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam. It can be proven that FCV19 can be seen as another hindrance factor that prevented Vietnamese learners from studying online in the current context. This was also similar to Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al. (2020) when students had to learn within the limit of learning resources.

Pedagogical Implementation

The current study highlighted that fear is another factor affecting students’ online learning adaptability. Also, students were a little afraid of the COVID-19 pandemic but the high level of adaptation. This helps educators in the home country understand more about local students’ psychological characteristics. The study also reinforced findings from previous studies about online learning barriers in the region. It will effectively contribute to education administrators having appropriate support for students to overcome difficulties in the online learning process, making online education more effective and accessible to all learners.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the FPT University, Can Tho, Vietnam. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

DV took the main duty in launching the idea and writing the review of literature and findings. NK took responsibility in writing the introduction and research methodology. HT analyzed data and wrote discussion. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adnan, M., and Anwar, K. (2020). Online learning amid the covid-19 pandemic: students’ perspectives. J. Pedagog. Sociol. Psychol. 2, 45–51. doi: 10.33902/JPSP

Ahorsu, D. K., Lin, C.-Y., Imani, V., Saffari, M., Griffiths, M. D., and Pakpour, A. H. (2020). The fear of COVID-19 scale: development and initial validation. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 27, 1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8

Arpaci, I., Karatas, K., Baloglu, M., and Haktanir, A. (2020). COVID-19 phobia in the United States: validation of the COVID-19 Phobia Scale (C19P-SE). Death Stud. 1, 1–7. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2020.1848945

Brislin, R. W. (1986). “The wording and translation of research instruments,” in Cross-Cultural Research and Methodology Series, Vol. 8, eds W. L. Lonner and J. W. Berry (Thousand Oaks, CA: Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research), 137–164.

Collie, R. J., Holliman, A. J., and Martin, A. J. (2017). Adaptability, engagement and academic achievement at university. Educ. Psychol. 37, 632–647. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2016.1231296

Colomer-Lahiguera, S., Ribi, K., Dunnack, H. J., Cooley, M. E., Hammer, M. J., Miaskowski, C., et al. (2021). Experiences of people affected by cancer during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic: an exploratory qualitative analysis of public online forums. Support. Care Cancer 29, 1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06041-y

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Newbury Park, CA: Sage publications.

De Leo, D., and Trabucchi, M. (2020). COVID-19 and the fears of Italian senior citizens. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:3572. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103572

Elsharkawy, N. B., and Abdelaziz, E. M. (2021). Levels of fear and uncertainty regarding the spread of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) among university students. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 57, 1356–1364. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12698

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50.

Guven, D. C., Sahin, T. K., Aktepe, O. H., Yildirim, H. C., Aksoy, S., and Kilickap, S. (2020). Perspectives, knowledge, and fears of cancer patients about COVID-19. Front. Oncol. 10:1553. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01553

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., and Tatham, R. (2006). Multivariate Data Analysis. Uppersaddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Holliman, A., Martin, A. J., and Collie, R. (2018). Adaptability, engagement, and degree completion: a longitudinal investigation of university students. Educ. Psychol. 38, 785–799. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2018.1426835

Holliman, A. J., Waldeck, D., Jay, B., Murphy, S., Atkinson, E., Collie, R. J., et al. (2021). Adaptability and social support: examining links with psychological wellbeing among UK students and non-students. Front. Psychol. 12:205. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.636520

Hurmerinta-Peltomäki, L., and Nummela, N. (2006). Mixed methods in international business research: a value-added perspective. Manag. Int. Rev. 46, 439–459. doi: 10.1007/s11575-006-0100-z

Johnson, L., Gutridge, K., Parkes, J., Roy, A., and Plugge, E. (2021). Scoping review of mental health in prisons through the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open 11:e046547. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046547

Keyes, K. M., Pratt, C., Galea, S., McLaughlin, K. A., Koenen, K. C., and Shear, M. K. (2014). The burden of loss: unexpected death of a loved one and psychiatric disorders across the life course in a national study. Am. J. Psychiatry 171, 864–871. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13081132

Lopez, G. I., Figueroa, M., Connor, S. E., and Maliski, S. L. (2008). Translation barriers in conducting qualitative research with Spanish speakers. Qual. Health Res. 18, 1729–1737. doi: 10.1177/1049732308325857

Martin, A., Nejad, H., Colmar, S., and Liem, G. (2013). Adaptability: how responses to change, novelty, variability, and uncertainty predict academic and non–academic well–being. J. Educ. Psychol. 105, 728–746. doi: 10.1037/a0032794

Martin, A. J., Collie, R. J., and Nagy, R. P. (2021). Adaptability and high school students’ online learning during COVID-19: a Job demands–resources perspective. Front. Psychol. 12:3181. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.702163

Martin, A. J., Nejad, H., Colmar, S., and Liem, G. A. D. (2012). Adaptability: conceptual and empirical perspectives on responses to change, novelty and uncertainty. J. Psychol. Couns. Sch. 22, 58–81. doi: 10.1017/jgc.2012.8

Martin, A. J., Nejad, H., Colmar, S., Liem, G. A. D., and Collie, R. J. (2015). The role of adaptability in promoting control and reducing failure dynamics: a mediation model. Learn. Individ. Differ. 38, 36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2015.02.004

Natalia, D., and Syakurah, R. A. (2021). Mental health state in medical students during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Educ. Health Promot. 10:208. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_1296_20

Pattavina, A., and Palmieri, M. J. (2020). Fears of COVID-19 contagion and the Italian prison system response. Vict. Offender. 15, 1124–1132. doi: 10.1080/15564886.2020.1813856

Pérez-Jorge, D., Barragán-Medero, F., Gutiérrez-Barroso, J., and Castro-León, F. (2018). A synchronous tool for innovation and improvement of university communication, counseling and tutoring: the whatsapp experience. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 14, 2737–2743. doi: 10.29333/ejmste/90588

Pérez-Jorge, D., Rodríguez-Jiménez, M. d. C, Ariño-Mateo, E., and Barragán-Medero, F. (2020). The effect of COVID-19 in university tutoring models. Sustainability 12:8631. doi: 10.3390/su12208631

Rodríguez-Hidalgo, A. J., Pantaleón, Y., Dios, I., and Falla, D. (2020). Fear of COVID-19, stress, and anxiety in university undergraduate students: a predictive model for depression. Front. Psychol. 11:3041. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.591797

Singh, V., and Thurman, A. (2019). How many ways can we define online learning? A systematic literature review of definitions of online learning (1988-2018). Am. J. Distance Educ. 33, 289–306. doi: 10.1177/0047239520934018

Urooj, U., Ansari, A., Siraj, A., Khan, S., and Tariq, H. (2020). Expectations, fears and perceptions of doctors during Covid-19 pandemic. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 36, S37–S42. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2643

Van, D. T. H., and Thi, H. H. Q. (2021a). Gender discrepancies in online english learning in vietnam amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. IAFOR J. Educ. 9, 7–27. doi: 10.22492/ije.9.5.01

Van, D. T. H., and Thi, H. H. Q. (2021b). Student barriers to prospects of online learning in vietnam in the context of Covid-19 pandemic. Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. 22, 110–123. doi: 10.17718/tojde.961824

VandenBos, G. R. (2007). APA Dictionary of Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/14646-000

Appendix

Keywords: fears of COVID-19 pandemic, FCV19, adaptability, online learning, mixed-method

Citation: Van DTH, Khang ND and Thi HHQ (2022) The Impacts of Fears of COVID-19 on University Students’ Adaptability in Online Learning. Front. Educ. 7:851422. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.851422

Received: 09 January 2022; Accepted: 14 February 2022;

Published: 09 March 2022.

Edited by:

Nurbiha Shukor, University of Technology Malaysia, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Fernando Barragán-Medero, University of La Laguna, SpainZaleha Abdullah, University of Technology Malaysia, Malaysia

Copyright © 2022 Van, Khang and Thi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nguyen Duy Khang, bmRraGFuZ0BjdHUuZWR1LnZu

Dao Thi Hong Van

Dao Thi Hong Van Nguyen Duy Khang

Nguyen Duy Khang Ha Hoang Quoc Thi

Ha Hoang Quoc Thi