95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 02 June 2022

Sec. Teacher Education

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.848547

This qualitative study examines the levels of feedback given by university supervisors to student teachers during their co-assessment meeting in French-speaking Belgium. For this purpose, 14 co-assessment meetings were qualitatively analyzed. The co-assessment meeting is the final step in the internship supervision process and allows the student teacher to compare their self-evaluation with the cooperating teacher’s evaluation report and the supervisors’ evaluation. The analysis showed that the certification objective of the internship meeting influenced the level of feedback. Within this objective, the feedback was task-oriented. In the formative part of the meeting, the feedback was more process-oriented and self-regulatory. In this type of meeting, supervisors therefore adopt a dual perspective for feedback, both cognitivist and socio-constructivist. This dual perspective is part of a continuum logic.

In many countries, the old paradigm of pre-service teacher education as provided only in and by universities has long since been outdated (Zeichner, 2010). Academic knowledge was once considered the authoritative source in pre-service teacher education. This old paradigm was replaced some time ago by a paradigm of alternating university courses and internships. The importance of internships in students’ educational programs has been demonstrated (Narayanan et al., 2010; Hora et al., 2020). For student teachers, the internship has become a protected field of experimentation that allows them to experience the classroom, develop their pedagogical skills and become socialized within the profession (Hascher et al., 2004; Chu, 2020). It also increases their self-confidence (Knoblauch and Chase, 2015; Waber et al., 2020). In addition, it promotes interaction between the expertise of university supervisors and that of cooperating teachers (He, 2009; Nguyen, 2009; Clarke et al., 2014), and thereby strengthens the links between theoretical and practical training (Bower and Bennett, 2009; Mesker et al., 2020).

In the context of French-speaking Belgium, teacher training currently lasts 3 years. The length of internships increases as the training progresses, from 2 weeks in the first year of training to 10 weeks in the final year. Unlike in the United States where the supervisor can be a faculty member or an adjunct educator, or sometimes a retired administrator or teacher (Slick, 1998), in Belgium, the supervisor is automatically a faculty member who is assigned this task in addition to their teaching load. The supervisor is hired primarily on the basis of their disciplinary expertise and not prior supervisory experience or training (Colognesi and Van Nieuwenhoven, 2017). However, the supervisor must go and observe and evaluate the student teacher at the practical training site.

Students are supervised during their internship by both supervisors from the university and cooperating teachers (Ballinger and Bishop, 2011; Cuenca et al., 2011; Johnson, 2011). During the internships, these cooperating teachers and supervisors work together with the student teacher, forming the supervision triad (Rogers and Keil, 2007; Wang and Ha, 2012; Range et al., 2013; Allen et al., 2014). Many studies have highlighted the difficulties and even tensions encountered by these actors in exercising their support function (Hansford et al., 2004; Bradbury and Koballa, 2008; Leshem, 2010; Desbiens et al., 2013; Izadinia, 2017; Portelance and Caron, 2017; Hudson and Hudson, 2018), whether related to the relationship between the actors, to their communication or to the multiple roles played by the supervisors. More precisely, some research (Bujold, 2002; Hansford et al., 2004; Mieusset, 2013; Zinguinian and André, 2017) has evoked the tension that arises when a person switches from a supportive to an evaluative posture. This tension can be encountered by the cooperating teacher or supervisor who is called upon to provide an evaluative judgment of the student teacher’s performance. In this study, we are only looking at the university supervisor.

To investigate the difficulties encountered by the supervisor in performing their function, several studies have documented the supervisor’s activity (Slick, 1998; Boutet and Rousseau, 2002; Cuenca, 2010; Bélair, 2011; Correa Molina, 2011). However, these studies did not focus specifically on the co-assessment meeting that takes stock of the student’s internship experience and performance. This meeting is at the center of our work, in order to understand how supervisors construct their evaluative judgments in this situation (Colognesi and Van Nieuwenhoven, 2017). One study (Maes et al., 2018) found that an important tension arises in the context of co-assessment, that caused by the supervisors’ shift from a supportive to an evaluative role.

The characteristics of these evaluative judgments appear to be similar to those of professional evaluation judgments (Allal and Mottier Lopez, 2008). The production of the final evaluative judgment by the supervisors is a dynamic and iterative process that takes into account the uniqueness of the situation (Jorro and Van Nieuwenhoven, 2019). Their evaluative judgment is based on a situated perspective (Mottier Lopez and Allal, 2008) and on partial and provisional judgments (Tourmen, 2009) rendered by the supervisor. This has led us to focus on the organization of these partial and provisional evaluative judgments within the co-assessment meeting. We are also interested in the content of these judgments, in order to analyze the levels of feedback they provide to the student. For that purpose, four levels of feedback have been identified: task, process, self-regulation and person (Hattie and Timperley, 2007). We also consider the perspectives within which these levels of feedback are integrated: cognitivist or socio-constructivist (Evans, 2013).

In this context, this contribution aims at a triple objective: first, examine how co-assessment meetings are organized; second, identify the different levels of feedback formulated by university supervisors during the co-assessment meetings; third, address the perspective (cognitivist or socio-constructivist) adopted by supervisors in their feedback. This study thus aims to document the evaluative activity of the university supervisor, which is still underdeveloped in the literature (Gouin and Hamel, 2015), in order to improve the evaluation of student teachers’ pre-service teacher training internships.

Before clarifying the roles of the supervisor, it seems useful to us to clarify the concept of supervision. Supervision is a continual process of exchange (Villeneuve, 1994) between the different actors: the student teacher, the cooperating teacher and the supervisor (Boutet, 2002). Supervision can be seen as having two dimensions, one concerning training and the other related to control. According to Boutet (2002), to be pedagogical, supervision cannot be limited to control; on the contrary, it must allow the student teacher to learn. This is supported by Spallanzani et al. (2017), who defined instructional supervision as a supportive relationship aimed at improving student teacher performance.

According to various authors (Enz et al., 1996; Gervais and Desrosiers, 2005; Correa Molina, 2008), supervisors play a triple role in the performance of their duties. They are at the same time a support for the student teacher, a resource person for the cooperating teacher, and a mediator between the training institute and the training site.

In the context of our study, our attention is focused on the supervisor’s role as the student teacher’s coach. In this role, the supervisor observes the student teacher and acts on this observation, supports and encourages the student teacher, conducts seminars, and finally, evaluates the trainee. It is more precisely this evaluation function that is observed during our study. While some authors have pointed to a tension between the support and evaluation postures (Bujold, 2002; Mieusset, 2013; Zinguinian and André, 2017), here the evaluation posture is integrated into the support role (Gervais and Desrosiers, 2005; Correa Molina, 2008).

Deeley (2014) defined co-assessment as “a shared system of assessment, synonymous of cooperative and collaborative assessment” (Deeley, 2014, 39). For Dochy et al. (1999, 342), building on the work of Hall (1995), “Co-assessment, the participation of students and staff in the assessment process, is a way of providing an opportunity for students to assess themselves whilst allowing the staff to maintain the necessary control over the final assessments.” Again, according to Deeley (2014, 39), “Fundamentally, it involves self-assessment in addition to assessment by another, for example, the teacher.”

From these definitions, we take the idea that co-assessment is a system of shared evaluation. It allows the student teacher to compare their own evaluation with that of the teacher. In addition, it allows the supervisor to keep control over the final evaluation judgment. In the context of teaching placements, co-assessment is defined as:

a joint evaluation between a student teacher and the supervisor(s) with a view to initiating a dialogue between them on differences in evaluation in relation to a particular product or a more global evaluation, whether or not it is based on an external reference system (Jorro and Van Nieuwenhoven, 2019, 37, free translation).

The co-assessment, carried out after the internship has been completed, brings together the supervisors and the student teacher with a view to building a global assessment of the internship (Colognesi and Van Nieuwenhoven, 2017). It seeks to give meaning to the evaluation by setting up a logic of dialogue. The supervisors make sure to keep the student teacher at the center of the process by developing the student teacher’s reflexivity.

As a form of cooperative and collaborative assessment, the co-assessment meeting is a relevant time to provide the student teacher with feedback about the internship being evaluated. It is this feedback, formulated by the supervisors, that is at the heart of our study.

Feedback is about enabling people to know the knowledge and skills they already have (Rodet, 2000). In the field of educational psychology, feedback has been identified as one of the most powerful levers for learning (Hattie and Timperley, 2007; Ko et al., 2014). Teaching feedback is necessary for learning to teach: it allows teachers to reflect on their teaching practice, assess their growth, and set goals accordingly (Wexler, 2020).

In the field of teaching internships, feedback is a specific type of information explaining the comparison between the observed student teacher’s performance during the internship and the standard defined by the university (Hattie and Timperley, 2007; Van De Ridder et al., 2008). This standard is operationalized through the institutional grid that includes the different items evaluated. The primary aim of the feedback is “to improve the trainee’s performance” (Van De Ridder et al., 2008, 193). However, “feedback must be recognized as a complex and differentiated construct that includes many different forms with, at times, quite different effects on student learning” (Wisniewski et al., 2020, 13).

In their model, Hattie and Timperley (2007) presented four levels of feedback: task, process, self-regulation and person-centered. Here we contextualize them to the theme of this research.

• The first level concerns the task carried out by the student teacher during his internship. It is information-oriented (for example, the criteria on the institutional grid are met or not) and allows surface knowledge to be developed. It is also called “corrective feedback.”

• The second level concerns the process used by the student teacher to carry out the task related to the teaching practice developed during the internship. Information processing is at the center of this level. For example, the feedback may include proposing alternative processes or helping with better error detection.

• The third level aims at the student teacher’s regulation of their own learning. Feedback can thus help the student teacher to increase their ability to self-assess and increase self-confidence.

• The fourth level directly addresses the student teacher’s person. This level is necessary in order to reassure and encourage, but it should not replace the other three levels.

It is assumed that the feedback must be appropriate to the student teacher’s level of understanding or slightly higher, and that a distinction must be made between the first three levels describing learning progress and the fourth level focusing on the person of the student teacher.

In addition, Rodet (2000) proposed three types of feedback: informative (presenting findings), making suggestions (formulating proposals, advice) or prescriptive (giving actions to be carried out, often starting with “it is necessary”).

Furthermore, feedback can be given from a cognitivist or a socio-constructivist perspective (Archer, 2010; Evans, 2013). The former is closely linked to a directive approach in which feedback is thought of as corrective. The supervisor communicates information on what needs to be corrected to a “passive” student teacher. The latter considers feedback to be facilitative for the student teacher by allowing them, through dialogue, to develop new understandings without dictating what those understandings will be (Archer, 2010). The supervisor provides comments and suggestions that allow the student teacher to make their own corrections. These two perspectives are not mutually exclusive. They further suggest the idea of a continuum that requires consideration of the precise nature and importance of the feedback in relation to individual needs, context and support functions.

In this study, three objectives are pursued. The first objective of this research is to examine how co-assessment meetings are organized. So, we want to understand how supervisors handle this moment. How do they give the student teacher a voice? How are skills reviewed? The second objective is to identify the different levels of feedback formulated by the supervisors during the co-assessment meetings. And the third is to address the perspective adopted in this feedback. These goals are based on the following hypotheses:

• The purpose of the co-assessment meeting (formative or certification) influences the perspective (cognitivist or socio-constructivist).

• The purpose of the co-assessment meeting (formative or certifying) influences the feedback levels used by the supervisors.

• The feedback levels used by supervisors adopt either the cognitivist or the socio-constructivist perspective.

The following research questions, exploratory in nature, guided the study:

• Do the perspectives adopted in the supervisors’ feedback influence the organization of the co-assessment meetings?

• Are supervisors’ feedback levels influenced by the primary aim of the co-assessment meetings?

• What perspective is adopted in the feedback levels used by the supervisors?

This is a qualitative study with an interpretative purpose (Crotty, 1998). The qualitative approach allows flexibility in the progressive construction of the object of study, as well as adjustment to the characteristics and complexity of the phenomenon studied (Anadón, 2006). We seek to understand the phenomena studied based on the meanings given by the actors in their natural environment (Denzin and Lincoln, 1994).

Our study was conducted in French-speaking Belgium, where teacher training currently takes place over t3 years. The time allowed for teaching internships increases as the training progresses: 2 weeks in year 1, 4 weeks in year 2 and 10 weeks in year 3.

The supervision process at the teacher training institute selected for this study with regard to teaching internships involves four main stages.

• In the first stage, before the internship, the student teacher and the assigned supervisor define the objectives of the internship.

• In the second stage, during the internship, two university supervisors (the assigned supervisor who accompanies the student teacher through the supervision process and a visiting supervisor, whose observation and participation in the co-assessment meeting are used for certification) separately observe the student teacher in action in the internship school. At the end of this observation, they each provide feedback to the student teacher during a debriefing meeting. This occurs directly after the activity.

• In the third stage, upon return from the placement, the student teacher and the assigned supervisor meet to conduct a reflective meeting. This meeting aims to allow the student teacher to reflect on their internship practices in order to identify possible problems and solutions and also to prepare for the final stage of the process.

• In the fourth stage, which concludes the process, there is a co-assessment meeting between the assigned supervisor, the visiting supervisor and the student teacher. As the cooperating teacher cannot be physically present, their opinion is taken into account through their report. This meeting result in a certified assessment of the skills the student teacher is expected to develop. An overall assessment of the internship is also decided upon during this meeting.

This co-assessment meeting is at the heart of our research. Figure 1 below illustrates this supervision process.

The co-assessment interview was conducted according to the following institutional guidelines constructed by the supervisory team based on the competency framework:

• The assigned supervisor conducts the interview.

• The assigned supervisor relays the cooperating teacher’s comments stated in the report.

• The duration of the interview is minimum 10 min.

• The student teacher explores, clarifies and explains his vision of the internship.

• The assigned supervisor enriches the reflection with aspects of the context and appreciation of the observed practice.

• The student teacher’s level of reflexivity is explored through follow-up questions.

• The assigned supervisor completes the evaluation document and writes down the personal objectives that have been identified.

• The level of success achieved is communicated to the student teacher.

This research is based on a deliberate sample of typical cases (Patton, 1990) consisting of 14 co-assessment meetings involving 14 supervisors1 from the same teacher training institution, all of whom supervise student teachers in their internships during the last year of training. Table 1 below provides information on these 14 supervisors, giving their position within the institution and their experience as internship supervisors (in years). Table 1 distinguishes between the assigned supervisor and the visiting supervisor roles2 for the two actors who provided feedback during the co-assessment meetings for each student teacher.

The participants gave their consent for the recording of the co-assessment meeting and the use, within the framework of research, of the data thus collected. The researchers took care to preserve the anonymity of the participants. The first names used in this study are pseudonyms.

Objective traces were collected in the form of 14 recorded co-assessment meetings involving assigned supervisors, visiting supervisors and student teachers, which were transcribed verbatim. A content analysis of these textual transcripts (Miles and Huberman, 1994) was conducted. Pre-established categories were used, based on the four levels of feedback (Hattie and Timperley, 2007). Version 12 of NVivo software (QSR International, 2017) was used. Two expert supervisors performed independent coding of two verbatim transcripts to check on the reliability of the coding. A Cohen’s kappa of 0.7813 was obtained, which corresponds to strong agreement between the three coders according to Landis and Koch (1977).

The results are structured around the research questions. The aspects presented are illustrated with excerpts from emblematic meeting transcripts.

Table 2 shows the duration of each interview and the two sections of the interview that were identified. The part of the interview when the feedback perspective was socio-constructivist to facilitate student teacher understanding was aimed at the self-regulatory, formative dimension. During this part, the student teacher was led to take an active role by describing the strengths identified and the difficulties encountered. The other, when the feedback perspective was cognitivist and was thought of as corrective, was for certification purposes, during which the various items in the evaluation grid3 were reviewed and evaluated.

In 12 of the 14 meetings analyzed, the certification part was longer than the formative part. The perspective was predominantly cognitivist, and the feedback formulated was corrective. This was likely due to the certification aim of the meeting, which should lead to a final assessment. Only two meetings included a formative part longer than the certification part. The socio-constructivist perspective was more present in the formative part, while not obscuring the cognitive perspective linked to the certification dimension of the meeting.

A transition sentence clearly identified when the assigned supervisor moved from one logic to the other. This is shown by the following extracts4 :

Delphine: What I am proposing is that we now quickly take stock of the situation within our grid here. We will compare our points. (Meeting 7)

Pascal: We will now look at the skills. (Meeting 10)

Dany: So we will try to complete the strengths, challenges and actions. So you, for your strength section, what did you notice? (Meeting 13)

The results showed that the 14 co-assessment interviews were composed of a certification and a formative part. For 12 of them, the certification part was longer. In this part, the perspective was mainly cognitivist. In the formative part, the socio-constructivist perspective was present.

Table 3 shows the distribution of comments at the different feedback levels (Hattie and Timperley, 2007) by meeting. Then, for each level, a more detailed analysis is proposed, which is illustrated with examples.

Table 3 shows that, for each of the meetings analyzed, the greatest number of feedback comments were related to the task (an average of 16 comments per meeting), for 222 task-related comments in all, close to 60% of the total feedback comments given. The certification objective of these co-assessments explains this result. Next came feedback on processes, 94 comments in all (an average of seven comments per meeting), or 25% of the total; followed by feedback on self-regulation, with 49 comments in all (an average of three comments per meeting), or 13% of the total. The absence of person-related feedback is obvious, with eight comments spread over five meetings, or barely 2% of the total feedback comments. Furthermore, the number of comments made was not directly related to the length of the meeting. Indeed, 28 comments were made in each of meetings 3, 4, and 6, although the meeting durations ranged between 27 and 41 min.

By linking the level of feedback to the part of the meeting (formative or certifying), and thus to the perspective pursued by the feedback given (cognitive or socio-constructivist), the results revealed, with a few nuances, an articulation of the different levels of feedback during the two main parts of the meeting. In what follows, each level is developed and illustrated with examples from the transcripts.

The formative and regulatory part of the meeting was mainly punctuated by feedback on the teaching processes and strategies used by the student teacher during their internship. These feedback comments were based upon and built on the student teacher’s comments, comments from the two supervisors present (assigned supervisor and visiting supervisor) based on their reports and those made by the assigned internship supervisor in his report. Below, one type of process feedback identified a “winning” strategy that was implemented:

Delia5 : And I put “answer wisely” because in fact you used several workshops when I observed. And you made connections with the students, so you didn’t bring the connections. You asked questions in such a way that they made connections and the way you accompanied their reflection seemed very judicious to me, so this DIY had really become an opportunity for reflection and connection between the sequences they had experienced, and then I found that it was really a level, you brought them to a cognitive task and not to a task. (Meeting 4)

Another type of feedback underlined and identified strengths in the processes used by a student teacher:

Dolly6 : And so, group management, natural authority, involves all the students, adapts instructions to the students… simple, clear, structured, it7 is a beautiful quality, too, that!

Didier: Adaptation, it’s still fundamental for the first year of primary school. (Meeting 2)

Yet another type of feedback targeted difficulty encountered by the student teacher in their processes and defined the objective of overcoming this difficulty during the next internship:

Student 3: In relation to my lesson planning, there is a link, as you said, between my objective, my skills and my progress. Consistency.

Daisy: Yes, but come back to “what is lesson planning?”.

[…]

Perrine: If you have the courage to read the documents, everything is in there and that explains why you are being taught that. And in terms of respecting the rhythm of the children, this is fundamental, especially in preschool education. Well, that’s still true even in primary school.

Daisy: So, I’m reviewing the whole structure of the different lesson plans.

Student 3: Yes.

Daisy: That’s why I think you really need to dive into the genesis,8 then after that, working on the coherence between the different sections9 and staying the course because you were constantly changing a little. There was no common thread. (Meeting 3)

This regulatory and formative part also included feedback concerning student teacher self-regulation, which was less frequent than that concerning processes. This type of feedback mainly had the objective of leading the student teacher to develop their reflective practice by questioning their own practice and analyzing the difficulties they had encountered.

Student 5: For me, it was a good experience, the first year of primary school. It’s really something else, I can’t compare that with other years, I think. And at first it was really hard for me.

Patricia: Hard, why?

Student 5: Working with young children, we really have to adapt each lesson and also with the material. The visuals, the spoken part, and those who need to manipulate all the time. At first, it was a bit complicated for me and then, already after the first week, I realized that I had to change my lessons. So, I worked a lot during the weekend and during the week really to adapt.

Patricia: And how did you realize that?

Student 5: I had already noticed that, during my lesson, the children. that I didn’t keep their attention. It was too complicated sometimes. And also, the advice of my cooperating teacher, it really helped me. That is, to improve all this. But at the end of the internship, I was happy. Yes, because I had a good relationship with the children. Even if the class was really difficult, in the end it was good. And I noticed that the lessons were better.

Patricia: Great. (Meeting 5)

In the following extract, the supervisors pushed the student teacher’s thinking in order to get the student teacher to find their own regulatory strategies and objectives for the next internship.

Pauline: And so, one lead for action would be to continue to?

Student 11: Be sure to note the instructions for the students carefully.

Pauline: To anticipate the instructions well or as much as possible in any case. Continue to anticipate instructions!

Pamela: You know that I, after 30 years of teaching, always write down my instructions in my lesson preparations.

Student 11: I find it helps to memorize them and have the structure in mind. (Meeting 11)

The extract continued with the supervisors proposing a strategy to be implemented during the next internship.

Pauline: But you yourself put a lead: “do as in the theatre.” Have you tried that?

Student 11: When I thought about it, yes. And it worked, especially when I told stories. Now I could get their attention.

Pauline: You dare to do that, because some students don’t dare too much. Be more theatrical even outside of stories. So, transfer this attitude a little that we could have a little more. Yes, which could be called “more theatrical” when telling stories in other lessons.

Pamela: Yes, I confirm that, because when you read “Barrabas’s story,” it was really very cheerful to hear you!

Student 11: Yes. and I also noted the mastery of the oral language in relation to voice modulation. (Meeting 11)

These consecutive extracts show that, in this part of the meeting oriented toward regulation, the levels of feedback alternated as discussion and reflection took place. One or more issues were raised and analyzed. Regulatory options were either proposed by the student teacher following feedback aimed at self-regulation, or by supervisors when they emerged from feedback targeting processes.

Feedback aimed at self-regulation was also used to help student teachers identify positive elements of their internship practice:

Patricia: We’ll get your strength back. Didn’t you get your strength back either?

Student 6: No, it’s a little hard.

Didier: 0 force?

(Laughs)

Student 6: I still have trouble completing this.

Patricia: So, it’s important that you can focus on your strengths! Go ahead, share all your strength with us!

Student 6: For me, in the positive points I felt, it was really the interaction with the children. For me, I really have a very, very good contact with them. Even with the child with whom it was more difficult. well, in the end. It wasn’t to me directly; it was more about his situation. I really managed to make contact with them, so they saw me as their teacher for 3 weeks. (Meeting 6)

The small amount of feedback that directly targeted the student’s person also appeared in the formative part of the meeting. This was much less frequent and appeared in only four of the 14 meetings analyzed. These comments could complement feedback on processes, as shown in the following example:

Didier: If I can, Pascal, in relation to the qualities of the student, I noted “Outstanding animation.” So, that means theatricality, facial expressions. Extraordinary! I think she’s the best intern I’ve seen in this field. I would like to insist on that!

Student 9: Thank you. (Meeting 9)

They could also highlight an aspect of the student’s person, an attitude:

Didier: I noticed, a great professional conscience, too. We feel like you’re someone who’s trying to do, uh, everything right.

Pascal: Yes! (Meeting 10)

In the other part of the meeting, which aimed to certify each item on the institutional grid and produce the final evaluative judgment, feedback on the task was provided, with a few exceptions. What changed from one case to another was the dynamics of how the meeting was conducted. The cooperating teacher’s report could be used as a guideline:

Patricia: So, the next one, level 310 for your cooperating teacher. What about you?

Student 5: Me, too.

Patty: Me, too.

Patricia: Okay, level 3. (Meeting 5)

In other meetings, the institutional evaluation grid was used as a basis for the exchange, and each item was discussed. Everyone shared their views and then consensus was sought. The student teacher’s involvement could be more timid, and the exchange took place mainly between the two supervisors:

Pascal: The whole design of the lessons. A level 3.3, 4 even!

Didier: Yes, for me too.

Pascal: With a lot of differentiation already!

Didier: Yes, exactly. (Meeting 9)

Sometimes the student teacher’s involvement might be more important, because of the place he was given at the meeting:

Delphine: What I propose is that we now quickly take stock of the situation with our grid. Here, we’ll compare our points. So there, I have mastered the oral language, 1.1, I have 4.

Student 7: I put 3.

David: I put 3 too.

Delphine: Okay, I’ll put 3 +.

(Laughs)

Delphine: That being said, you do have a very. How can I say this? You’re paying attention! I mean, I don’t know if you’re attentive to your oral language, but you have high quality oral language. That’s it! That’s it!

David: Yes, that’s right. That’s nice to hear!

Delphine: I say that because I care. You’re pleasant to listen to. And it’s true that the fact that you’re adapting to children, I think it’s worth showing that there’s a level 4 that’s been pointed out here. And it’s hard to give yourself that kind of thing, that kind of points. 1.211, level 3 for the cooperating teacher.

David: Yes.

Student 7: Yes, I put 3 too.

Delphine: I have 4 in spelling.

Student 7: Yes, I put 4 too. (Meeting 7)

It is also interesting to note that there were no significant differences in views or difficulties in reaching consensus in the meetings analyzed. In some situations, the supervisor was called upon to make a decision, and this was most often in the student teacher’s favor:

Dany: So, we’re on skill 5.12 That’s all the knowledge you pass on to the children. So, in terms of your answers. There, she13 even puts you at a level 3 because apparently you manage to construct things in a very correct way with the children in relation to the different content. Did you get into it?

Student 13: I had put myself at a level 2.

Dolly: And I was more at level 1 because. but I think you were a little stressed. by my presence, by our presence. And it’s true that I didn’t feel you were sufficiently invested, etc.

Dany: I’m looking a little bit. So, there the cooperating teacher puts: “Attentive to know the subject proposed to the children. She has always tried to answer children as judiciously as possible.” We’re going to put a level 2, like this.

Student 13: Okay! (Meeting 13)

Another element that emerged from the analysis of the results is that it was sometimes difficult to evaluate certain components of the grid. This could be because they were not observed by the supervisor during his visit:

Didier: So, skill 3,14 we have a level 3. And you, did you have?

Student 1: Level 3.

Dolly: I put unobserved, but positive impression, it seems to me well integrated into the school.

Didier: Great! We are at 4.1. I will read, “inquires about the subjects taught, questions about children’s difficulties.” That’s not bad, is it? Here, we have a level 3. What about you?

Student 1: I put a level 3.

Dolly: Me, not observed. (Meeting 1)

Sometimes this occurred because they were not understood by the student teacher, for example:

Delphine: 7.115 Managing the class in a challenging way, I have 3.

David: I put 2.

Student 7: I didn’t understand that, I didn’t put anything there.

Delphine: Ah, that’s because you forgot to look there. It is simply the competence that deals with classroom management.

Student 7: Ah, okay! (Meeting 7)

A few rare feedback comments on processing were identified in the certification part of the meeting. The following excerpt is an example:

Patricia: Managing the organizational dimension?

Didier: I put 3.

Student 6: I put 4.

Patricia: She16 also gives you a 4. I think that’s your strong point too!

Didier: For the benefit of the student.

Patricia: Yes, the activity I saw was great! She changed the space. She had great equipment. (Meeting 6)

Feedback from the final evaluation judgment was task oriented. Here is an example that illustrates this:

Daisy: So, your cooperating teacher puts you between B and C.17 It is true that apart from the 1.5 that we have put in spelling, everything is at the expected level or even higher. You get C.

Delia: I am between C and B. I would have put a C +. A C with very good professional reflexes. That’s what I would have said.

Daisy: Well, listen, I will circle B–C?

Delia: Yes.

Daisy: Yes, you are different, you are beyond C for several components. (Meeting 4)

Much of the feedback provided by supervisors during the co-assessment meetings, just under 60% (222 pieces of feedback), was task related. This is explained by the certification purpose of the co-assessment meeting. Next, we find feedback on the process at 25% of the total (94 pieces of feedback), and feedback on the student teacher’s self-regulation at 13% of the total (49 pieces of feedback). In 9 of the 14 co-assessment meetings analyzed, there was no feedback on the student teacher’s person.

The results showed that the supervisors produced feedback on the task during the part of the meeting aimed at certifying each item on the institutional grid and constructing the final evaluative judgment. The formative and regulatory part of the meeting was mainly punctuated by feedback on teaching processes and strategies as well as feedback on the student teacher’s self-regulation.

We sought to identify the perspective within which these feedback comments were framed. The certifying aim of the meeting would tend to place it by default in a cognitivist perspective. However, in the part of the meeting aimed at regulatory and formative purposes, feedback oriented toward the student teacher’s process was part of a more socio-constructivist perspective. In this perspective, the aim was to provide the student teacher with comments and suggestions enabling them to self-regulate and acquire new knowledge. This is illustrated by the following extract:

Pauline: And so, to say “I’ll prepare my oral instructions for the students so I can be clear about this” or “it can help me to,” but then there’s fatigue, as you say.

Student 11: Yes, and so there it was, planning of instruction still helped, but there were still other circumstances that played a role.

Pauline: Yes, and so that regulation track really helped. and so one course of action would be to continue then to.

Student 11: Please note the instructions!

Pauline: To anticipate the instructions well or as much as possible in any case. continue to anticipate the instructions.

Pamela: You know that I, after 30 years of teaching, always write down my instructions in my lesson plans. (Meeting 11)

This was especially true when the feedback was aimed at developing student teacher self-regulation. In that case, the student teacher was asked to make their own comments on their activity and to identify their own suggestions for promoting their self-regulation. This is shown in the following extract:

Student 11: I have to accelerate the pace by alternating groups, individual and game activities. So. that I need to be more attentive to the biological rhythm of the students, to their attention to be able to accelerate the pace. And no more alternating between group and individual moments.

Pauline: You tried to do that a little bit.

Student 11: Yes, at the end, I didn’t dare do it anymore, but at first, I always wanted to stick to my schedule. And especially during the last week, I tested the closing activities a lot. The calming and relaxing activities helped a lot because I had an active class.

Pauline: So, pick up the pace, because if I hear, well it was still evolving when you tested things. Okay! Okay!

Student 11: Yes, and become more spontaneous in the rhythm. (Meeting 11)

The certification part of the meeting was part of a cognitivist perspective. Feedback from supervisors could then essentially be considered as corrective. This was indeed the case when the supervisors, together with the student, had evaluated each component of the institutional grid and formulated task-oriented feedback, as shown in the following extract:

Delphine: The written language: 3.

Doriane: I had put 2.

Student 8: I had put 3, it doesn’t seem to me that I made any mistakes.

Delphine and Doriane: Let’s put 3! (Meeting 8).

The same applied to the construction of the final evaluation judgment, which gives the student teacher an overall assessment for the entire internship:

Didier: So, what this gives us in terms of evaluation. I was at a B. I say “me,” excuse me, because I’m starting a little selfishly. The visiting supervisor was at a real B, too. Your cooperating teacher was clearly at a B. And you, were you?

Student 1: At a B.

[…]

Didier: Perfect with all this, it’s a level B. It’s a great success! (Meeting 1)

In light of the extracts presented, a nuance regarding the student’s role can be added to the definition of this cognitivist perspective (Evans, 2013). Indeed, the student teacher’s role was not passive, and the student teacher played a role in the construction of evaluative judgments. As mentioned above, the student’s involvement varied according to the dynamics initiated within each triad.

The results showed that the feedback produced during the certification part of the meeting was task-oriented and was part of a cognitivist perspective. However, in the regulative and formative part of the meeting, the feedback produced was oriented toward the process and self-regulation of the student teacher as part of a more socio-constructivist perspective.

As a reminder, the objectives of this study were threefold: first, to examine how co-assessment meetings are conducted; second, to identify the different levels of feedback given by supervisors during co-assessment meetings; and third, to address the perspective adopted by this feedback. Three aspects emerged from the results. These relate to the research questions.

All evaluation meetings analyzed comprised two parts. These two distinct parts in all of the analyzed evaluation interviews can be compared to the idea of formative and certificatory meetings (Balslev et al., 2017). Thus, within the same meeting, the supervisor takes two roles, depending on the two phases of the meeting. In the first part, the student teacher takes an active role in highlighting his or her strengths and difficulties. We think this is important. Indeed, in a perspective of maintaining a partnership relationship (Maes et al., 2018; Jorro and Van Nieuwenhoven, 2019), it seems important that all of the actors involved can express themselves. Moreover, giving the floor first to the student teacher places them as a priority in their training. It also shows on the part of the supervisors that they are interested in the student teacher’s opinion, and want to try to understand the student teacher’s point of view (Spallanzani et al., 2017), from a non-deficit perspective (Malo, 2019). Then the supervisors provide students with comments and suggestions that allow them to self-regulate and acquire new knowledge. In the second part, the competencies in the grid are reviewed. On average, the second part takes 2/3 of the meeting. The fact that they all use these criteria is, in our view, a great advantage. Indeed, criterion-referenced grids have the advantage of giving evaluators an analytical evaluation system in which each component is evaluated individually and similarly for each individual (Berthiaume et al., 2011). These criteria, as they are reviewed one after the other, provide explicit and specific feedback to students (Balan and Jönsson, 2018).

Moreover, the results highlighted that, despite the dominant certification perspective pursued in the co-assessment meeting within this training institute, a place was left for dialogue between the student teacher and his supervisors (Dochy et al., 1999; Deeley, 2014). And this was evident in both parts of the meeting. The student teacher could thus compare their self-assessment with the assessments of these different supervisors (assigned and visiting supervisors). These elements therefore strongly corroborate the use of the concept of co-assessment to characterize these meetings (Deeley, 2014).

Supervisors used more task-oriented feedback than any other level of feedback (Hattie and Timperley, 2007). This can be explained by the certification objective of the co-assessment meeting. Indeed, the primary objective of this meeting is to determine, as an assessment, a final evaluative judgment certifying the student’s performance during the entire internship. However, it is interesting to observe that we identified as co-occurring within the same meeting feedback that was part of a cognitivist perspective aiming at correcting and other feedback that was part of a socio-constructivist perspective aiming at facilitating the student’s understanding. Thus, the two perspectives are not exclusive; on the contrary, they are mutually reinforcing (Evans, 2013). In another study (Maes et al., 2020), the co-assessment meetings at the end of the first internship were analyzed from a formative perspective. Here, process-oriented feedback and self-regulatory feedback made up the majority of the comments, with task feedback relegated to the very end of the meeting when supervisors had to make an assessment (without the certification function in this context). The purpose of the meeting would therefore influence the level of feedback mobilized. However, even in the context of certification, it is important not to forget that the student teacher is still in training. Indeed, we have shown that process-oriented and self-regulatory feedback are also important.

When this happens, as we have shown, process-oriented feedback allows, on the one hand, the identification of winning strategies and, on the other hand, proposal of alternative strategies when the student teacher is in difficulty. This feedback is thus part of a socio-constructivist perspective aiming at facilitating the student’s understanding of their practice. Thus, in the context of teacher training, this type of feedback seems essential, because it highlights suggestions, alternative proposals, and even, if the situation is difficult, prescriptions (Rodet, 2000).

In this context of initial training, the supervisor’s self-regulation feedback is important. Indeed, this feedback allows the student teacher to identify their own strengths and difficulties in a self-regulatory perspective. It also aims to facilitate the student’s understanding of his practice. It reinforces the socio-constructivist perspective by giving the student teacher a central place in the analysis of their practice.

With respect to feedback about the student’s person, the results are consistent with Hattie’s (2011) comments (2011). Such comments were largely in the minority and initiated with a view to encouragement and congratulations. They supported the supervisors’ comments while not replacing the other three levels.

Feedback, in the form of partial judgments (Tourmen, 2009), sheds light on each of the components of the institutional evaluation grid and thus contributes to the construction of the final evaluation judgment (Maes et al., 2020).

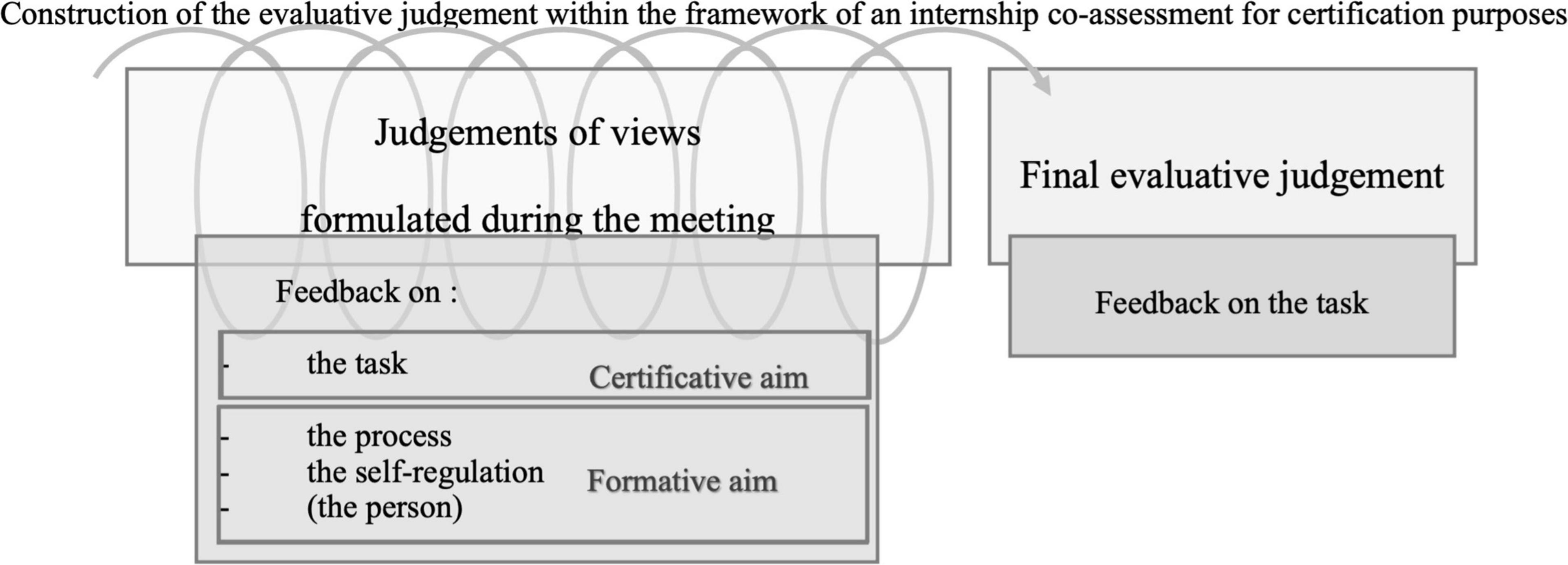

The figure below presents a model of the construction of supervisor evaluative judgment in a context of co-assessment of the internship for certifying purposes (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Evaluative judgment construction (according to Hattie and Timperley, 2007; Mottier Lopez and Allal, 2008; Tourmen, 2009).

Finally, cognitivist and socio-constructivist (Evans, 2013) perspectives coexisted in the 14 meetings analyzed. This is not problematic since, according to Evans (2013), they are not mutually exclusive. On the contrary, they should be seen as mutually reinforcing in the service of meeting the student’s needs. As presented in the context of the study, the institutional guidelines provide for an active role for the student teacher by asking them, on the one hand, to explore, clarify or explain their vision of the internship and, on the other hand, to develop their reflexivity during the meeting. This can be seen in the presentation of our results. Indeed, in the meetings studied, the students did not play a passive role, even if the degree of their involvement differed according to the dynamics initiated by the two supervisors.

This study has certain limitations. The specific context is an important one. Indeed, these are 14 co-assessment meetings conducted by 14 supervisors from the same training institute in French-speaking Belgium. It would be of interest to further investigate this question of the nature and content of feedback when co-evaluating pre-service teacher training internships in a broader context, at an international level. Another limitation is the focus on the co-assessment meeting. Indeed, this practice is not widespread in all training institutes; it would be interesting to look at other evaluation mechanisms as well.

Several practical implications emerge from our study. First, it seems wise to provide feedback training for practicum supervisors. Introducing them to the different types of feedback and their effects on students’ teaching practices seems an interesting suggestion. Second, based on the prerequisite that supervisors do not have many opportunities to talk about their jobs, it seems appropriate to allow them to compare how they manage the assessment meetings. For that, meetings such as those transcribed could be used as a basis for discussion. Ultimately, the challenge is to enable supervisors to improve their feedback practices. This appears to be an appropriate way for student teachers to become more effective.

This research qualitatively studied the levels of feedback given by university supervisors to student teachers during their 14 co-assessment meetings, the final step in the internship supervision process, in Belgium. Therefore, this study contributes to the literature on feedback in the context of experiential learning. The findings showed the influence of the certification purpose on the levels of feedback provided in the assessment meetings. When referring to the outcomes, the feedback is informative and task-oriented, while it is process-oriented and self-regulatory during the formative part of the meetings.

To conclude, the key message of this article is that supervisors use different levels of feedback in a teaching placement co-assessment meeting. The feedback thus formulated can be part of a cognitive or socio-constructivist perspective, depending on the objective pursued. The two perspectives then reinforce each other. This is strengthened by the primary objective of a co-assessment meeting, which is to allow a shared and joint evaluation in which the student teacher must have an active place. It is therefore important for the supervisor not to omit the formative dimension and to formulate feedback that aims at process and self-regulation. These will support the student teacher in his or her process of understanding and regulation. This is not possible with task-oriented feedback, which, according to Hattie and Timperley (2007), produces more surface knowledge.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because it is confidential data because it allows the identification of participants who have been guaranteed anonymity. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to OM, b2xpdmllci5tYWVzQHVjbG91dmFpbi5iZQ==.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

OM under the direction of CV and SC to this contribution is the result of a study carried out within the framework of a doctoral research. The article was co-authored by the three authors. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Allal, L., and Mottier Lopez, L. (2008). “Mieux comprendre le jugement professionnel en évaluation : Apports et implications de l’étude genevoise.” [Gaining a better understanding of professional judgment in evaluation: Contributions and implications of the Geneva Study],” in Jugement professionnel en évaluation: Pratiques enseignantes au Québec et à Genève, eds L. Lafortune and A. Allal (Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec), 223–239.

Allen, D. S., Perl, M., Goodson, L., and Sprouse, T. K. (2014). Changing traditions: supervision, co-teaching, and lessons learned in a professional development school partnership. Educ. Considerations 42, 19–29.

Anadón, M. (2006). La recherche dite ‘qualitative’: de la dynamique de son évolution aux acquis indéniables et aux questionnements présents. “[Qualitative research: from the dynamics of its evolution to the undeniable achievements and current questions]. Recherches Qual. 26, 5–31. doi: 10.7202/1085396ar

Archer, J. C. (2010). State of the science in health professional education: effective feedback. Med. Educ. 44, 101–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03546.x

Balan, A., and Jönsson, A. (2018). Increased explicitness of assessment criteria: effects on student motivation and performance. Front. Educ. 3:81. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00081

Ballinger, D. A., and Bishop, J. G. (2011). Theory into practice: mentoring student teachers: collaboration with physical education teacher education. Strategies 24, 30–34. doi: 10.1080/08924562.2011.10590941

Balslev, K., Perréard, V., and Tominska, E. (2017). “Formative, on est vraiment dans cette perspective-là : interventions et intentions d’une formatrice universitaire dans l’évaluation de stages.” [Formative, we are really in this perspective: interventions and intentions of a university trainer in the evaluation of traineeships]. Contextes et Didactiques 9, 30–35.

Bélair, L. (2011). “La reconnaissance de la professionnalité émergente par les superviseurs en situation pratique d’enseignement.” [Recognition of emerging professionalism by supervisors in practical teaching situations],” in La professionnalité émergente: quelle reconnaissance, ed. A. Jorro (Bruxelles: De Boeck Supérieur), 101–116.

Berthiaume, D., David, J., and David, T. (2011). Réduire la subjectivité lors de l’évaluation des apprentissages à l’aide d’une grille critériée : repères théoriques et applications à un enseignement interdisciplinaire.” [Reducing subjectivity in learning assessment using a criterion-referenced grid: theoretical references and applications to interdisciplinary teaching]. Rev. Int. pédagog. Enseign. Supér. 27

Boutet, M. (2002). “Pour une meilleure compréhension de la dynamique de la triade.” [For a better understanding of the dynamics of the triad],” in Les enjeux de la supervision pédagogique des stages, eds M. Boutet and N. Rousseau (Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec), 81–95.

Boutet, M., and Rousseau, N. (2002). Les enjeux de la supervision pédagogique des stages. [The challenges of pedagogical supervision of internships]. Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec.

Bower, G. G., and Bennett, S. (2009). The examination of the advantages of a mentoring relationship during a metadiscrete physical education field experience: ICHPER-SD. J. Res. 4, 19–25. doi: 10.1080/00221473.1964.10610220

Bradbury, L. U., and Koballa, T. R. Jr. (2008). Borders to cross: identifying sources of tension in mentor–intern relationships. Teach. Teach. Educ. 24, 2132–2145. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2008.03.002

Bujold, N. (2002). “La supervision pédagogique: vue d’ensemble.” [Educational supervision: an overview],” in Les enjeux de la supervision pédagogique des stages, eds M. Boutet and N. Rousseau (Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec), 9–22.

Chu, Y. (2020). Preservice teachers learning to teach and developing teacher identity in a teacher residency. Teach. Educ. 32, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/10476210.2020.1724934

Clarke, A., Triggs, V., and Nielsen, W. (2014). Cooperating teacher participation in teacher education: a review of the literature. Rev. Educ. Res. 84, 163–202. doi: 10.3102/0034654313499618

Colognesi, S., and Van Nieuwenhoven, C. (2017). “Le processus de coévaluation entre superviseurs et étudiants en formation initiale des enseignants du primaire.” [The supervisor-student co-assessment process in preservice elementary teacher education]. Rev. Canad. Éduc. 40, 1–27. Available online at: http://journals.sfu.ca/cje/index.php/cjerce/article/download/2398/2429

Correa Molina, E. (2008). “Perception des rôles par le superviseur de stage.” [Role perception by the internship supervisor],” in L’accompagnement concerteì des stagiaires en enseignement, eds M. Boutet and J. Pharand (Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec), 73–89. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv18pgnjm.8

Correa Molina, E. (2011). “Ressources professionnelles du superviseur de stage: une étude exploratoire.” [Professional resources for the internship supervisor: an exploratory study]. Rev. Des Sci. Éduc. 37, 307–325. doi: 10.7202/1008988ar

Crotty, M. J. (1998). The foundations of social research: Meaning and perspective in the research project. Newbury Park: Sage.

Cuenca, A. (2010). In loco paedagogus: the pedagogy of a novice university supervisor. Stud. Teach. Educ. 6, 29–43. doi: 10.1080/17425961003669086

Cuenca, A., Schmeichel, M., Butler, B. M., Dinkelman, T., and Nichols, J. R. (2011). Creating a ‘third space’ in student teaching: implications for the university supervisor’s status as outsider. Teach. Teach. Educ. 27, 1068–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2011.05.003

Deeley, S. J. (2014). Summative co-assessment: a deep learning approach to enhancing employability skills and attributes. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 15, 39–51. doi: 10.1177/1469787413514649

Denzin, N. K., and Lincoln, Y. S. (eds) (1994). Handbook Of Qualitative Research. Newbury Park: Sage.

Desbiens, J. F., Spallanzani, C., and Borges, C. (2013). Quand le stage en enseignement déraille: regards pluriels sur une réalité trop souvent occultée.” [When the teaching internship goes off the rails: a plural view of a reality that is too often overlooked]. Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec.

Dochy, F., Segers, M., and Sluijsmans, D. (1999). The use of self-, peer and co- assessment in higher education: a review. Stud. High. Educ. 24, 331–350. doi: 10.1080/03075079912331379935

Enz, B. J., Freeman, D. J., and Wallin, M. B. (1996). “Roles and responsabilities of the student teacher supervisor: Matches and mismatches in perception,” in Preparing tomorrow’s teachers: The field experience – Teacher education yearbook IV, eds D. J. McIntyre and D. M. Byrd (Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press), 131–150.

Evans, C. (2013). Making sense of assessment feedback in higher education. Rev. Educ. Res. 83, 70–120. doi: 10.3102/0034654312474350

Gervais, C., and Desrosiers, P. (2005). L’école, lieu de formation des enseignants – Questions et repères pour l’accompagnement de stagiaire. Laval: Presses de l’Université Laval.

Gouin, J. A., and Hamel, C. (2015). La perception de formateurs de stagiaires quant au développement et à l’évaluation formative des quatre compétences liées à l’acte d’enseigner. Rev. Can. Éduc. 38, 1–27.

Hall, K. (1995). “Co-assessment: participation of students with staff in the assessment process,” in Paper presented at the 2nd European Electronic Conference on Assessment and Evaluation, European Academic & Research Network (EARN).

Hansford, B. C., Ehrich, L. C., and Tennent, L. (2004). Outcomes and perennial issues in preservice teacher education mentoring programs. Int. J. Pract. Exp. Prof. Educ. 8, 6–17.

Hascher, T., Cocard, Y., and Moser, P. (2004). Forget about theory–practice is all? Student teachers’ learning in practicum. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 10, 623–637. doi: 10.1080/1354060042000304800

Hattie, J. (2011). Visible Learning For Teachers: Maximizing Impact For Learning. New York: Routledge.

He, Y. (2009). Strength-based mentoring in pre-service teacher education: a literature review. Mentor. Tutoring Partnersh. Learn. 17, 263–275. doi: 10.1080/13611260903050205

Hora, M. T., Parritt, E., and Her, P. (2020). How do students conceptualise the college internship experience? Towards a student-centred approach to designing and implementing internships. J. Educ. Work 33, 48–66. doi: 10.1080/13639080.2019.1708869

Hudson, P., and Hudson, S. (2018). Mentoring preservice teachers: identifying tensions and possible resolutions. Teach. Dev. 22, 16–30.

Izadinia, M. (2017). Pre-service teachers’ use of metaphors for mentoring relationships. J. Educ. Teach. 43, 506–519. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2017.1355085

Johnson, I. L. (2011). Teacher to mentor: become a successful cooperating teacher. Strategies 24, 14–17. doi: 10.1080/08924562.2011.10590927

Jorro, A., and Van Nieuwenhoven, C. (2019). “Le clair-obscur de l’activité évaluative,” in [He Chiaroscuro of Evaluative activity], in L’évaluation, Levier Pour L’enseignement et la Formation, eds A. Jorro and N. Droyer (Bruxelles: De Boeck), 33–44.

Knoblauch, D., and Chase, M. A. (2015). Rural, suburban, and urban schools: the impact of school setting on the efficacy beliefs and attributions of student teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 45, 104–114. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2014.10.001

Ko, J., Sammons, P., and Bakkum, L. (2014). Effective teaching: A review of research and evidence. Berkshire, New York: CfBT Education Trust.

Landis, J., and Koch, G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33, 159–174. doi: 10.2307/2529310

Leshem, S. (2010). The many faces of mentor-mentee relationships in a pre-service teacher education programme. Creat. Educ. 3, 413–421.

Maes, O., Colognesi, S., and Van Nieuwenhoven, C. (2018). ““Accompagner/former” ou “évaluer/vérifier” Une tension rencontrée par les superviseurs de stage des futurs enseignants?” [“Accompany/Train” or “Evaluate/Verify” A Tension Encountered by Supervisors of Student Teachers?]. Éduc. Format. 308, 95–106.

Maes, O., Van Nieuwenhoven, C., and Colognesi, S. (2020). “La dynamique de construction du jugement évaluatif du superviseur lors de l’évaluation de stages en enseignement.” [The dynamics of constructing the supervisor’s evaluative judgment in the evaluation of teaching internships]. Rev. Canad. Éduc. 43, 522–547.

Malo, A. (2019). “Apprendre dans un dispositif de formation en alternance: le cas de stagiaires en secondaire. L’Alternance en Éducation et en Formation.” [Learning in an alternating training system: the case of secondary school trainees. Alternation in education and training]. Éduc. Form. 314, 129–144.

Mesker, P., Wassink, H., and Bakker, C. (2020). How everyday classroom experiences in an international teaching internship raise student teachers’ awareness of their subjective educational theories. Teach. Dev. 24, 204–222. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2020.1747531

Mieusset, C. (2013). Les dilemmes d’une pratique d’accompagnement et de conseil en formation. Analyse de l’activiteì reìelle du maitre de stage dans l’enseignement secondaire. [The dilemmas of a training coaching and counselling practice. Analysis of the real activity of the training supervisor in secondary education]. Ph.D. thesis. France: Universiteì de Reims Champagne-Ardenne.

Miles, M. B., and Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook, 2nd Edn. Newbury Park: Sage.

Mottier Lopez, L., and Allal, L. (2008). Le jugement professionnel en évaluation : un acte cognitif et une pratique sociale située.” [Professional judgment in assessment: a cognitive act and a social practice situated]. Rev. Suisse Des Sci. Éduc. 3, 465–482.

Narayanan, V. K., Olk, P. M., and Fukami, C. V. (2010). Determinants of internship effectiveness: an exploratory model. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 9, 61–80. doi: 10.5465/amle.2010.48661191

Nguyen, H. T. (2009). An inquiry-based practicum model: what knowledge, practices, and relationships typify empowering teaching and learning experiences for student teachers, cooperating teachers and college supervisors? Teach. Teach. Educ. 25, 655–662. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2008.10.001

Portelance, L., and Caron, J. (2017). “Logique du stagiaire dans son rapport aÌ l’évaluation.” [Trainee’s logic in reporting to the evaluation]. Phronesis 6, 85–98. doi: 10.7202/1043983ar

Range, B. G., Duncan, H. E., and Hvidston, D. (2013). How faculty supervise and mentor pre-service teachers: implications for principal supervision of novice teachers. Int. J. Educ. Leadersh. Prep. 8, 43–58.

Rodet, J. (2000). La rétroaction, support d’apprentissage? [Feedback as a learning support]. Rev. du Conseil Qué. de la Formation à Distance 4, 45–46.

Rogers, A., and Keil, V. L. (2007). Restructuring a traditional student teacher supervision model: fostering enhanced professional development and mentoring with a professional development school context. Teach. Teach. Educ. 23, 63–80. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2006.04.012

Slick, S. K. (1998). The university supervisor: a disenfranchised outsider. Teach. Teach. Educ. 14, 821–834.

Spallanzani, C., Vandercleyen, F., Beaudoin, S., and Desbiens, J.-F. (2017). “Encadrement offert par des superviseurs universitaires en formation à l’enseignement : le point de vue de stagiaires finissants en EPS.” [Mentoring by university supervisors in teacher education: the perspective of graduating EPS teacher candidates]. Rev. Can. Éduc. 40, 1–30.

Tourmen, C. (2009). “L’activité évaluative et la construction progressive du jugement.” [The evaluative activity and the progressive construction of judgement]. Les Dossiers des Sci. Éduc. 22, 101–119.

Van De Ridder, J. M., Stokking, K. M., McGaghie, W. C., and Ten Cate, O. T. (2008).. What is feedback in clinical education? Med. Educ. 42, 189–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02973.x

Waber, J., Haugenauer, G., and De Zordo, L. (2020). Student teachers’ perceptions of trust during the team practicum. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 1–17. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2020.1803269

Wang, L. J., and Ha, A. S. (2012). Mentoring in TGfU teaching: mutual engagement of pre-service teachers, cooperating teachers, and university supervisors. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 18, 47–61. doi: 10.1177/1356336x11430654

Wexler, L. J. (2020). How feedback from mentor teachers sustained student teachers through their first year of teaching. Action Teach. Educ. 42, 167–185. doi: 10.1080/01626620.2019.1675199

Wisniewski, B., Zierer, K., and Hattie, J. (2020). The power of feedback revisited: a meta-analysis of educational feedback research. Front. Psychol. 10:3087. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03087

Zeichner, K. (2010). Rethinking the connections between campus courses and field experiences in college- and university-based teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 61, 89–99. doi: 10.1177/002248710934767

Keywords: pre-service teacher education, internship, co-assessment meeting, university supervisor’s feedback, final evaluative judgment

Citation: Maes O, Van Nieuwenhoven C and Colognesi S (2022) The Feedback Given by University Supervisors to Student Teachers During Their Co-assessment Meetings. Front. Educ. 7:848547. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.848547

Received: 04 January 2022; Accepted: 05 May 2022;

Published: 02 June 2022.

Edited by:

Dominik E. Froehlich, University of Vienna, AustriaReviewed by:

Julia Morinaj, University of Bern, SwitzerlandCopyright © 2022 Maes, Van Nieuwenhoven and Colognesi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Olivier Maes, b2xpdmllci5tYWVzQHVjbG91dmFpbi5iZQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.