- 1Department of English Language and Literature, Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran

- 2Department of Foreign Languages, Iran University of Science and Technology, Tehran, Iran

This study investigates the characteristics of an effective university professor based on the evaluations made by students in different majors at a state university in Iran. Two-hundred forty BA, MA, and Ph.D. students’ evaluations of their teachers were selected via purposive sampling. The evaluations were then content analyzed to determine which characteristics build the profile of an effective teacher in the students’ eyes. The results confirmed the findings of many previous studies that a good university professor needs to possess certain essential qualities. However, the profile of an effective university professor, at least the importance of the qualities that make up this profile, was rather different. More specifically, the most important criterion for evaluating the teachers was their assessment policies and practices. Furthermore, the findings suggest that the characteristics of an effective professor are dynamic and open to contextual, cultural and temporal influences. In light of the results of this study, it is recommended that higher education institutions put in place programs that educate teachers about a more learner-centered pedagogy to maximize not only their own teaching efficacy but also their students’ motivation and learning.

Introduction

Teachers play a significant role in classroom teaching and schooling process (Orhon, 2012). In recent years, the issue of characteristics of an effective teacher has been raised in a large array of studies (e.g., Lee et al., 2015; Morrison and Evans, 2018; Alzeebaree and Zebari, 2021; Singh et al., 2021; to cite but a few). These studies have identified a number of key qualities that build the profile of an effective teacher, including expert pedagogical skills, strong communication skills, passion for their profession (Murray, 2021), effective classroom management strategies, and solid knowledge of the subject matter or the field. Such qualities have been researched from the perspectives of teachers themselves (Mohammaditabar et al., 2019; Lisa et al., 2021) or students (Inan, 2014), with some studies comparing these two perspectives (Murphy et al., 2004) in order to provide a better portrayal of those qualities. The issue of what makes an effective teacher is of paramount importance due to the implications it has for teaching and learning quality (Bell, 2005), student and teacher relationship (Frisby et al., 2014), institutional quality (Catano and Harvey, 2011; Harrington, 2018), students’ motivation (Liando, 2015), and teachers’ professional development (Mohammaditabar et al., 2019). It should be noted, however, that the characteristics of an effective teacher is socially constructed and context-specific (Borg, 2006; Hughes et al., 2022), meaning that some characteristics that are valued in one context may not be appreciated as much in another context.

Examining students’ description of which characteristics constitute the profile of an effective university professor can be one useful way to optimize the instruction they receive at higher education institutions. Although there is a plethora of studies that have focused on identifying those characteristics, many of them are rather limited, either in the number of students whose perspectives have been examined or in the range of the majors these students have been selected from. To enhance the literature in this domain and given the importance of the issue and its wide-ranging applications, this study examines perceptions of students from various departments and degree programs at a well-known Iranian state university regarding the qualities of an effective teacher.

Literature Review

Considering the fact that the quality of teaching and its perception are influenced by both teachers and students’ values (Sotto, 2011), the issue of “what the characteristics of an effective teacher are” is one that has been approached from different perspectives. In a study conducted by Morrison and Evans (2018), the views of 37 Hong Kong university freshmen students about a good teacher were explored qualitatively and quantitatively; more specifically, cross-sectional and longitudinal data relating to students’ experience of transition from secondary to higher education were collected. The cross-sectional phase comprised administering a questionnaire, and the longitudinal phase involved conducting semi-structured interviews each semester of the participants’ first 2 years of study. The authors categorized the data into aspects of good and bad teaching practices. The results showed that the student’s primary focus was on the teachers’ pedagogical skills that helped their learning and encouraged critical thinking. In the same research strand, Su and Wood (2012), investigated undergraduate students’ perception of teaching excellence and the qualities of a good university lecturer. Over 100 students from over 20 UK universities wrote their answers to an essay completion task which invited them to write a 900–1,000-word essay to share their views on the question of “what makes a good university lecturer?” The results demonstrated that factors such as a combination of the lecturer’s subject knowledge, willingness to help, and inspirational teaching methods played a significant role in shaping the students’ perspectives toward a good university lecturer. Other important features included for teachers to be humorous and able to provide speedy feedback. Similarly, Arnon and Reichel (2007), explored similarities and differences in the perception of students of education regarding the qualities of a good teacher and of their own qualities as teachers. The 89 students who participated in this research were divided into two sub-groups: students at an academic teachers’ college who were designated as “student teachers” and “beginning teachers,” who while teaching, were completing their academic degrees at teachers’ colleges or regional academic colleges. They collected the data from these students via a questionnaire that comprised open-ended questions. The findings of the research revealed two significant categories: first, personal qualities and second, knowledge of the subject taught as well as educational knowledge. Analysis of the data indicated that both groups of the students gave great importance to the personal qualities of the ideal teacher. Still, there was a difference in students’ perspectives toward the teacher’s knowledge. The qualities of general education and wide perspectives were less prominent in the students’ attitudes. In the same vein, Reichel and Arnon (2009), investigated the similarities and differences in the perception of the good teacher among adult participants in Israel. The researchers intended to discover whether the students’ ethnicity and gender could account for the differences in their perceptions of the qualities of a good teacher and whether there exists an interaction between the two components. The interviewers in this study divided the 377 adults born in Israel into four groups, namely as Jewish men, Jewish women, Arab men, and Arab women. Findings of the content analysis of the open questions in a telephone survey illustrated that a good teacher is an individual with teaching knowledge, an educator, and a person of values who maintains good teacher-pupil relations. The study demonstrated that the perception of the qualities of a good teacher is culturally dependent and Arab-Israeli participants gave priority to the ethics of a good teacher over other factors. At the same time, the Israeli Jews preferred a more heterogeneous image of the qualities of a good teacher with a special emphasis on the teacher’s rapport and positive interaction with the pupils.

Moreover, Beran and Violato (2005), explored the students’ rating of teachers’ instruction by considering the student and course characteristics. In this study, 371,131 ratings from students across all faculties at a major Canadian university over a 3-year period were accumulated through the Universal Student Ratings of Instruction (USRI). The results demonstrated that students who attend the class and expect high grades marked high ratings for their instructors. However, the analysis of regression indicated that student and course characteristics explicate little variance in student ratings of their instructors. It was also revealed that students’ ratings were highly related to the teacher instruction and behavior of instructor rather than other factors. In addition, as Murray (2021) maintained, an ideal teacher’s prominence rests in the intersection of a high general level of literacy and numeracy, successful interpersonal and communication capabilities, a willingness to learn, and motivation to teach. The two specifications, “willingness to learn” and “motivation to teach,” correspond to the concept of “growth mindset,” a “can-do” mentality that fosters learning. The teacher with a growth mindset asks questions, persists in attempting, draws on previously taught strategies, and exploits failures as a springboard for learning experience. This inclination might be described as the yearn to learn. In the same vein, Richmond et al. (2015), conducted a study to evaluate teaching effectiveness through students’ rating of instruction. The participants of this study comprised 252 undergraduate students who were taking a psychology course at Texas Midwestern State University. The aim of this study was to investigate whether factors such as professor-student rapport, student engagement, and instructor’s use of humor can predict student’s perception of teaching effectiveness. A students ratings of instructors (SRI) survey was utilized to collect the data of the research. The results demonstrated that professor-student rapport was the highest predictor with 54 percent of the variability in SRIs, followed by student engagement with 3 percent and humor with 2 percent. Additionally, the results of the study corroborated previous research that those factors are essential to students’ perceptions of teaching effectiveness (Benson et al., 2005; Wilson et al., 2010). Furthermore, in a qualitative study by Joseph (2018), the philosophy and practice of effective professors were investigated through interviewing 35 teachers in the context of Trinidad and Tobago education system. The results of the content analysis revealed three themes, namely getting to know students, teacher as life-long learner, and teacher as role model. The results revealed that the factor of getting to know students was the most important one in the teaching practice of the professors. It should be pointed out that teacher as life-long learner and teacher as role model factors were also considered to be effective in the teachers’ teaching. The findings of this study provide insights into different philosophic positions of teachers; they also show how teachers carry out their teaching practice in the context of the Trinidad and Tobago education system. Similarly, Gruber et al. (2010), conducted a study to explore the factors that influence students’ satisfaction with teaching. For the purpose of this study, a questionnaire was given to 63 postgraduate students in a service marketing course at a large university in the United Kingdom. The results of the questionnaire confirmed the findings of other studies that the personality of the professors (e.g., Clayson and Sheffet, 2006) in general and their ability to establish good rapport with students (e.g., Delucchi, 2000) in particular had a significant impact on students’ satisfaction with teaching. The results also highlighted that teachers could improve classroom experience for their students by learning about the factors that make students satisfied or dissatisfied with teaching.

The qualifications of a competent teacher may be influenced by the time, context, and exceptional circumstances of the society in which teachers live. Lisa et al. (2021) interviewed 23 state elementary and secondary school teachers about the attributes of a good teacher during Covid-19 pandemic. Two primary themes emerged from the analysis, namely caring for the well-being of students and dealing with uncertainty. Teachers acknowledged that the importance of displaying these characteristics has increased throughout Covid-19. These results suggest that programs of teacher education and professional development may benefit from recognizing and encouraging teachers in attaining these characteristics.

Furthermore, Mohammaditabar et al. (2019), investigated the English as a foreign language (EFL) teachers’ perspectives of qualities of a good language teacher in three settings, that is, language institutes, high schools, and universities. They used a mixed-methods design in which 386 Iranian EFL teachers completed a self-report questionnaire on qualities of a good language teacher and a semi-structured interview was conducted with 40 of those teachers. The findings demonstrated that teaching boosters (e.g., the teachers’ knowledge of grammar, vocabulary and command of English), care, and enthusiasm were of paramount importance in the teachers’ perspectives in all three educational settings. Further, the results of MANOVA showed that there is a significant difference between language institute and senior/junior high school EFL teachers regarding morality and boosters. In a similar line of inquiry, Singh et al. (2021) carried out a study to discover the hallmarks of an ideal teacher educator as perceived by Malaysian educators. A survey comprised of eight items was utilized to collect data for this aim. The results demonstrated that an ideal teacher should exhibit certain attributes, including strong subject matter knowledge, competence of both general and content-specific pedagogy, and hands-on teaching capabilities. Further, the teacher educators acknowledged the necessity of adjusting their priorities in order to fulfill their vision, specifically the desire to accommodate the contemporary policies, creative approaches, and ever-growing educational patterns. Babai Shishavan and Sadeghi (2009) also explored the qualities of effective language teachers from the perspectives of Iranian EFL learners and teachers. To that end, a tailor-made questionnaire was administered to 59 English language teachers and 215 learners of English at universities, high schools, and language institutes in Iran. Their findings demonstrated that good command of the target language, good knowledge of pedagogy, the use of effective teaching methods, and good personality were perceived as the key characteristics of an effective EFL teacher.

The literature reviewed above shows that many studies have investigated the characteristics of a good university teacher, yet very few, if any, of those studies have investigated the characteristics of such a teacher from the viewpoint of students from different fields of study. The present study, therefore, intends to investigate the characteristics of a good university professor from the perspectives of students of different fields of study at an Iranian state university. The following research question was addressed in this study:

What are the characteristics of an effective university teacher from the perspective of students in different majors?

Materials and Methods

Corpus of the Study

The purpose of this research was to explore the characteristics of a good and effective university professor as perceived by students from different fields of study at an Iranian state university, namely Shahid Beheshti University which is one of the top-five universities in Iran. According to the university’s website,1 about 18,000 students study in 69 programs at Bachelor’s, 208 programs at Master’s and 136 programs at Ph.D. levels. For the purpose of this study, 240 BA, MA and Ph.D. students’ evaluations of their teachers were investigated. The evaluations, posted on a Telegram channel, were part of university students’ initiative to disseminate information regarding the quality of the institutions’ teachers in terms of their behavioral and instructional practices. The evaluations were also intended to help peer students choose their courses with those teachers who most matched their liking. To post their evaluations on the Telegram channel, students had to follow five criteria: the overall quality of the specific teacher’s class, his/her instructional methodology, communication skills, choice of instructional materials, and assessment practices. There was no word limit for the students’ comments about their teachers and some of the evaluations were rather lengthy so the researchers had to discard parts of those comments that were deemed irrelevant to the research purpose. These evaluations were all in Persian, the official language of Iran. The researchers, however, translated some excerpts of the evaluations into English to back up their assertions in the results section of this paper. The accuracy of the translations was assessed by a professional translator who was a native speaker of Persian and a near-native speaker of English. The local context did not require the researchers to obtain the approval of an ethical review committee to analyze the evaluations. However, to observe the ethical principles concerning privacy standards, the researchers made sure that identities of the professors mentioned in the evaluations were kept confidential by using pseudonyms instead of the professors’ real names.

Design of the Study

The data were considered secondary as they were written by the students for the purpose of evaluating the teachers rather than for the purpose of this research (see Su and Wood, 2012). As Church (2002) appropriately suggested, the promise of secondary data analysis resides in the intersection of establishing the generality of a quantitative function and identification of the issues of theoretical interest raised by the specific research gaps. The researchers of the present study, therefore, adopted Glaser (1963), secondary data analysis, which can be employed to study “specific problems through analysis of existing data which were originally collected for another purpose” (Glaser, 1963, p. 11). Moreover, the researchers used purposive sampling to collect the data; that is, they selected evaluation of those students who commented on all the five criteria and rated their teachers on a 0–10 scale which accompanied those criteria (0 poorest rating, 10 highest rating). Although care was taken to select data that represented the voice of students from different fields of study, we do not claim that these views are shared by all the students of those fields.

Procedure

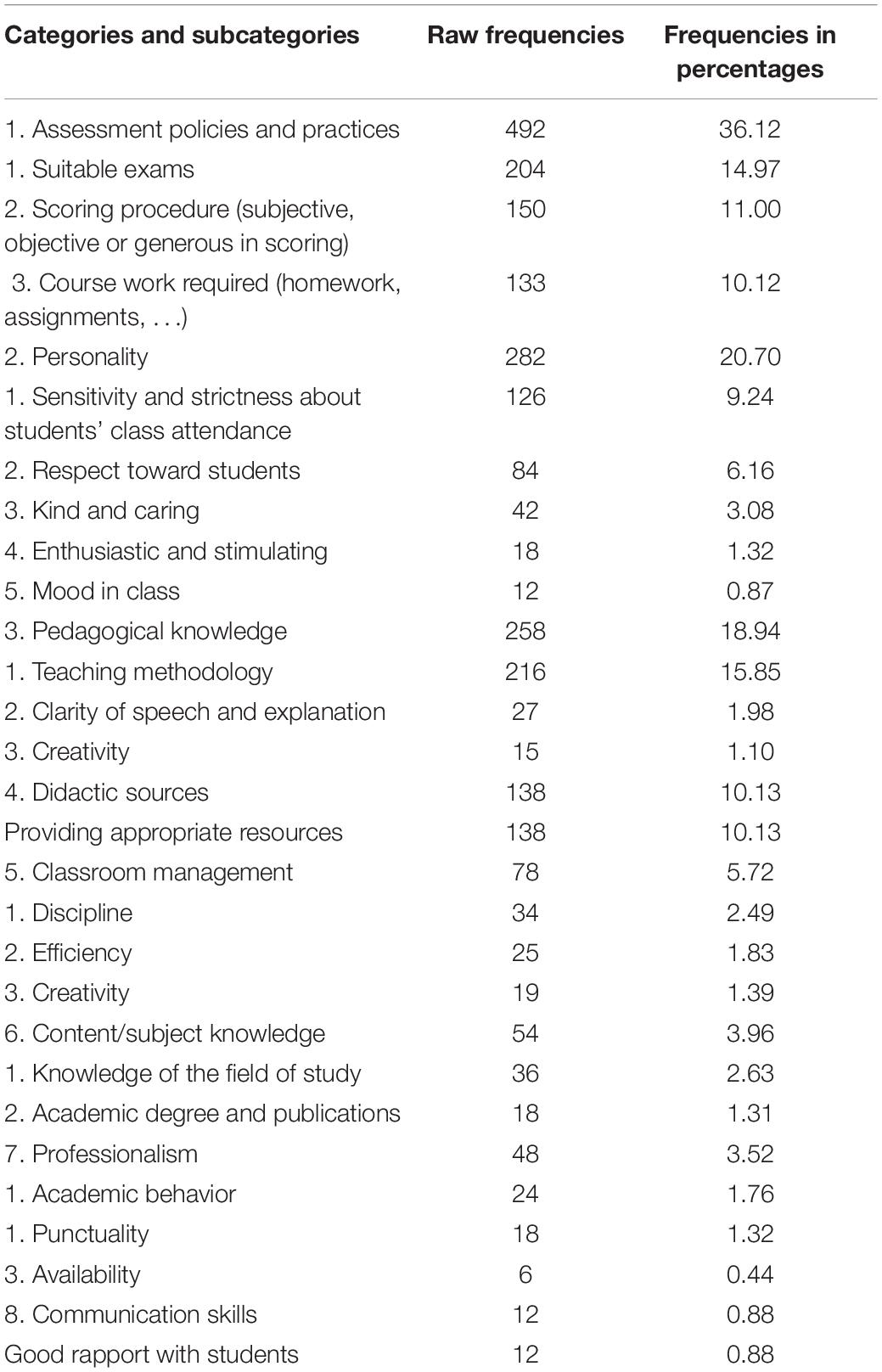

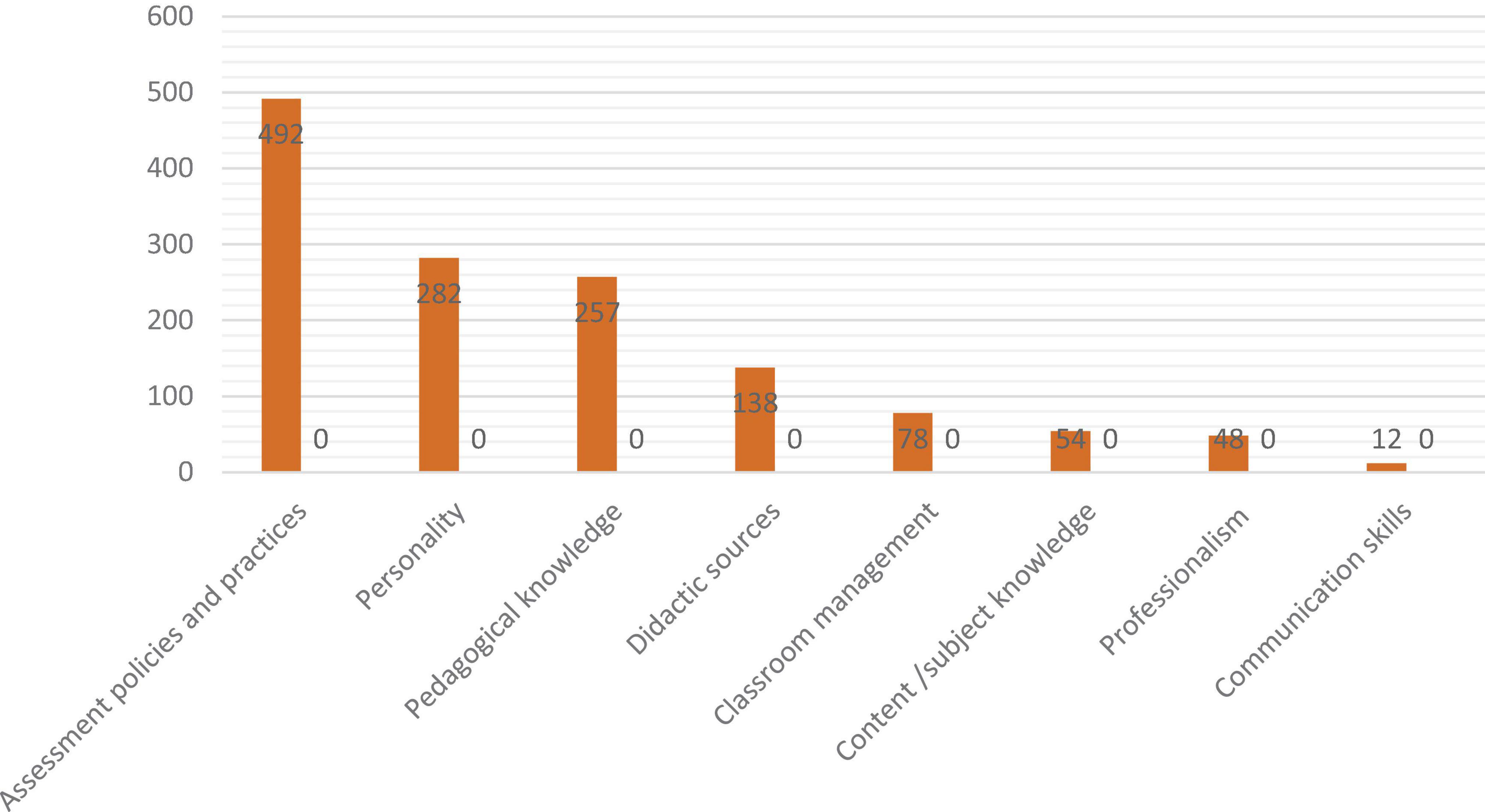

The researchers conducted a content analysis to analyze and interpret the data regarding the teachers; the analysis involved using an open, focused, integrative, and selective coding procedure (see Benaquisto, 2008). The purpose of coding was to identify and distinguish categories and provide evidence for each based on the existing data. In the first stage of the coding, called open coding, the researchers labeled the concepts and ideas by a close line-by-line reading, rereading and highlighting the most important points that could help them categorize the data. In this stage, analysis of the data was done without concerns about how the content in the students’ evaluations relate to each other. Through this procedure, the researchers started to detect new themes and categories, and then group examples or comments based on their similarities or differences. In the focused and integrative coding, the data were reviewed more systematically and thoroughly with the researchers having few prior categories in mind to know where and how these categories are demonstrated in the data. Through repeated reviewing and coding of the data, the researchers discovered the links between the categories, and in this way, they refined the categories and their components (i.e., subcategories). The intercoder reliability calculated by percentage agreement ranged from 0.81 to 0.98, showing a high reliability across all the categories. In addition, the researchers provide some excerpts of the students’ comments for each of the categories to highlight one aspect of the component in the category (see the results section of this article). The results of the coding and analysis of the students’ evaluations provided the researchers with eight main categories, namely teachers’ assessment policies and practices, personality, pedagogical knowledge, didactic resources, classroom management, teacher’s content/subject knowledge, professionalism and communication skills (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The breakdown of an effective university professor characteristics as perceived by the students.

A note should be made that some of these on the extracted categories may overlap (see Morrison and Evans, 2018). This is also evidenced in the literature where the analysis of the qualitative data can be influenced by some creativity and subjectivity on the part of the researchers (Drapeau, 2002; Ratner, 2002; Mruck and Breuer, 2003; Mohajan, 2018). To understand which of these categories and subcategories are of great significance to the students, the researchers calculated the frequency of each to find their distribution.

In qualitative research studies, the issue of sample size is a controversial one and there is no predetermined way to determine the size of the sample (Dworkin, 2012; Marshall et al., 2013; Robinson, 2013; Blaikie, 2018). To overcome this problem, the researchers of this study continued analyzing the data to reach data saturation, which is cited as a solution to the problem of sample size in qualitative studies (Vasileiou et al., 2018). The researchers reached that point by analyzing 240 students’ comments about their teachers. The two researchers analyzed the students’ evaluations independently, and an interrater reliability of 0.89 was obtained.

Results

The results of the content analysis of the data is demonstrated in Table 1. Top on the list of categories that mattered most to the students were the teachers’ “assessment policies and practices,” “personality,” and “pedagogical knowledge,” drawing more than 75 percent of the students’ responses. The remaining five categories constituted only around 25 percent of the responses.

A closer examination of Table 1 reveals that the subcategories in each of main categories received differential attention. In the “assessment policies and practice” category, the subcategory of the “suitable exam” (14.97%) was more important than the other two subcategories, that is, “scoring procedure” (11.00%) and “course work required” (10.12%). A suitable exam in the students’ words is one that is reliable, unambiguous, and commensurate in terms of difficulty with the materials taught during the semester. Moreover, students preferred multiple-choice exams over other forms of exams (e.g., essay-type exams) because they felt “multiple-choice exams are more objective.” Similarly, regarding the scoring, the results demonstrated that the students preferred objective scoring over subjective one since they believed this type of assessment would earn them a fair score as it would not be influenced by the teacher’s view toward different students. Some of the students’ concerns regarding their teachers’ assessment can be seen in the following comment:

He [the teacher] does not know much about designing standard items for the exam; his exam questions are full of ambiguous items; moreover, the items do not match with the materials taught during the semester, especially in terms of difficulty. In his final exam, there were some questions that were not in the materials introduced for the course; they were from other sources. The teacher also scores students subjectively, and you are sure to be surprised when you see your final term score. This is not fair. I rate this teacher 2 out of 10 and do not recommend taking the course with him (BA student of Mathematics).

The students also saw teachers who were generous with course grades as excellent ones and gave them high approval ratings. In the following quotation, an MSc student in Civil Engineering heaps praises on his teacher, saying:

He is one of the best university instructors that I have ever seen; he will add extra points to whatever score you obtain on the final exam. Hardly anyone fails his course. I give him 10 out of 10.

With regard to students’ work required, most of the students stated that they would not mind an extra manageable amount of work outside the class as long as “the teacher allocates some points for that” since these points would work toward higher final term course scores.

As for the teachers’ “personality,” the subcategory of “sensitivity and strictness about students’ class attendance” received the highest frequency (9.24%), but reviewing the students’ comments revealed that they regarded this as a negative characteristic in their teachers. This opinion was especially true about teachers who punished students score-wise for absenteeism and tardiness. In the comment below, a student highlights that point and writes:

She is not a good teacher because she is really sensitive to your presence in the class; she will mark you down if you are late or miss more than two classes during the semester. She will make you drop the course if you are absent thrice in her class. I highly recommend you take this course with Dr. Soroush (a pseudonym) if you can (BA student of History).

Of course, opinions diverged among students regarding this quality; some students mentioned that they appreciated teachers’ concern about their class attendance (but teachers should not mark them down for being absent or arriving late), with some students pushing it to the extreme saying that “teachers should not insist on students’ presence in the classroom; we are not kids anymore.”

The second most important quality of an effective teacher within the ‘personality’ category was “respect toward students” which drew 6.16 percent of the students’ responses. The students asserted that their teachers’ behavior and respect toward different students regardless of their ethnicity, social position, and gender were very important to them. The other subcategories within the “personality” category were for teachers to be “kind and caring” (3.08%), “enthusiastic and stimulating” (1.32%), and have appropriate and stable “mood in class” (0.87%). The results indicated that the students highly valued teachers who are kind, stimulating, and positive toward their students.

The third most important category was teachers’ “pedagogical knowledge,” and within this category, the subcategory of “teaching methodology” received 15.85 percent of the students’ responses. It has to be mentioned that the subcategory of “teaching methodology” has been rated as the most important of all the other subcategories in Table 1. To the students, teaching methodology translated as the way a teacher presents the course materials in the classroom, that is, whether the presentation is clear and orderly. A teacher “who just reads out of the textbook or off the PowerPoint slides and does not provide students with the complementary explanation” is not deemed as an effective teacher among the students. “Clarity of speech and explanation” (1.98%) and “creativity” (1.10%) are two further subcategories that received the students’ attention as factors contributing to the image of an effective teacher.

“Clarity of speech and explanation,” in the students’ words, is the teachers’ ability to provide students “with clear explanations and tangible examples.” “Creativity” in the “pedagogical knowledge” category meant exposing students to “new experiences” and bringing out “the innovation in classroom” to maximize and enhance students’ learning.

She is so creative in a sense that she runs some sort of game in the class in order to understand the materials in more effective way and at the end of the class she provides the class with a link which is a quick quiz game regarding the materials taught. At the end of the game, the students who get the highest score will receive the prize (MA student in Persian Language and Literature).

Another category was teachers’ “didactic sources” and the only theme that emerged in this category was “providing (academic) resources” to the students (10.13%). The students valued those teachers who provided them with appropriate and relevant educational materials which would facilitate their learning of the course content. It is interesting to note that the students preferred books with a lucid language; they also wanted their teachers to provide them with booklets that summarized and simplified the content of books that were difficult to read and understand.

To pass this course, you don’t need to study a big quantity of materials because he [the teacher] will provide you with a booklet which is 30 pages long. Reading this booklet is like taking a shortcut, it can help you achieve a good score on the final exam. Moreover, it is easier to study this teacher-prepared booklet because the language is so simple and it includes all the important points that teacher will consider when designing the final exam questions (BA student of History).

The student making the above comment gave her teacher the highest approval rating (i.e., 10), and it seems that those teachers who provide short summaries of their course content in the form of booklets are quite popular with students. That is quite understandable since booklets are an easy way out of reading and understanding their assigned texts.

“Classroom management” category, comprising teachers’ “discipline,” “efficiency,” and “creativity” subcategories, constituted only 5.72 percent of the students’ comments regarding the characteristics of an effective teacher. Among the subcategories, teachers’ “discipline” was valued more than other subcategories (2.49%). In the students’ eyes, teachers’ discipline meant that the teachers showed “systematic” and “in-control” behavior that established teachers’ authority and created a stress-free learning environment.

She is really great when it comes to classroom rules and procedures, which she establishes and elaborates right at the beginning of the course. The good thing is that although these rules may seem a bit tough, they are not in fact so; they give one a feeling of security in her class (MSc student in Chemistry).

Furthermore, the subcategories of “efficiency” and “creativity” drew 1.83 and 1.39 percent of the students’ responses; the students believed teachers who are “efficient” make best of use of available resources, especially educational technologies, to increase students’ learning outcome. “Creativity” in “classroom management” is related to but a bit different from “creativity” in “pedagogical knowledge” category in that “creativity” as part of pedagogical knowledge meant that teachers created innovative tasks that involved students in learning but “creativity” in “classroom management” meant that teachers employed novel tasks that brought order to a chaotic and sometimes boring class.

He is so creative in class, especially in utilizing technologies to enhance learning, and keeps you on your toes. At the end of the class, for instance, when everyone is quite tired and restless, he engages students in online quizzes and games that not only review the session content partially but also help students through sometimes boring or difficult class (Ph.D. student in Physics).

Surprisingly, “content/subject knowledge” of the teachers was not that high on the list of the students’ priories, as indicated by the rather low share of the comments this category received (3.69%). This might be due the fact that the majority of the students in the Telegram channel were BA students and did not care much about their teachers’ academic degree or their knowledge (or publications) in the specified discipline. This category comprised teachers’ “knowledge of the field of study” and their “academic degree and publications,” neither of which seemed to matter much to the students.

Teachers’ “professionalism” was the penultimate category on the list of characteristics of an effective university professor (3.52%). The qualities that were subsumed under this category were “academic behavior,” “punctuality” and “availability.” Academic behavior included avoidance of all forms of unacceptable behavior such as lying, cheating, plagiarism, use of unauthorized materials, divulging students’ private and personal information to other students or colleagues, etc. Students also appreciated teachers who were punctual, who were available in their office or via social networking apps to provide students with feedback on their assignments and answered students’ course-related queries. One of the students contended:

You can rest assured that he is one of the best teachers at our university; he is responsible and encouraging toward his students and treats them kindly and tactfully. He is always in time for class, and in fact punctuality is one of his main characteristics. Last but not least, he is easy to find in the department; whenever you need help, you just need to go to his office and you will find him there. You can trust him and talk to him easily about your problems (MSc student in Architecture).

And finally, the category of “communication skills,” which involved the teachers’ ability to establish and have a good rapport with students, received the least frequency (0.88%), indicating that those skills were not considered important qualities when evaluating the teachers. This finding was rather odd given the fact that previous studies (e.g., Rossettiand Fox, 2009; Starcher, 2011; Webb and Barrett, 2014) have shown teachers’ communication skills significantly contributed to their teaching efficacy. The researchers of this article think this finding could be attributed to the contextual specifications of the study; that is, in the context of Iranian universities teachers cannot establish that much of a friendly relationship with their students due to rather formal regulations governing the student-professor relationship and the ensuing gap that develops between the position of students and teachers in such a context. If this research could be replicated in another context, a language institute for instance, the factor of a good rapport may have drawn the attention of many students when evaluating their teachers.

Discussion

This article reports on an exploratory study about students’ perceptions of an effective teacher at a university context in Iran. The results of the study confirmed the findings of many of the previous studies (e.g., Arnon and Reichel, 2007; Reichel and Arnon, 2009; Su and Wood, 2012; Morrison and Evans, 2018) that a good university professor needs to possess certain abilities. However, the picture of an effective university professor, at least the importance of the qualities that make up the profile of an effective university professor, was rather different in this study. As Vinz (1996), rightly remarks, practices of teaching are positioned in specific contexts, and these contexts are framed by interrelated factors. Therefore, it could be argued that the issue of which characteristics render a university professor effective in the eyes of the students is truly multidimensional. The current research also suggests that the characteristics of an effective teacher are dynamic and open to contextual, cultural and temporal factors which affect evaluation of those characteristics (Reichel and Arnon, 2009; Murray and Kosnik, 2011). This finding also accords with those of Lisa et al. (2021), which confirmed that the features of a competent teacher lie at the nexus of time, context, and distinctive societal conditions in which teachers live. Additionally, Babai Shishavan and Sadeghi (2009), study, which examined the notion of an effective teacher at three different educational contexts in Iran (i.e., universities, high schools and language institutes) identified target language command, good pedagogical knowledge of, use of effective teaching methods, and good personality as the main qualities of an effective language teachers. Later on, in the same context of Iran, Mohammaditabar et al. (2019), investigated the EFL teachers’ perspectives of qualities of a good language teacher, and the findings highlighted the fact that teaching boosters, care, and enthusiasm were of paramount importance. By comparing the findings of these two studies with those obtained in this study, it can be concluded that time factors are highly important in the evaluation of an effective teacher. The findings of the present research could also be attributed to the context of the study (i.e., university) where term or exam scores usually distinguish strong and weak students from one another, at least on the paper, and students who finish their courses or programs with higher scores may be provided with certain academic bonuses and opportunities. Therefore, if this research is replicated in another context (at other academic institutions either inside or outside Iran), the findings might be different.

The results of the content analysis revealed that the three most important criteria for evaluating teachers were assessment, personality, and pedagogical knowledge. Investigation of the students’ comments showed that students judge an effective teacher mostly based on his or her assessment policies and practices; this finding is in contrast with what was found out by Mohammaditabar et al. (2019) who reported that teachers’ assessment policies and practices were the last-ranked feature of a good language teacher. It is also noteworthy that this criterion did not emerge as an important evaluation index in some studies investigating the characteristics of effective teachers (e.g., Su and Wood, 2012; Lupascu et al., 2014; Benekos, 2016). A possible justification for the emphasis of the students on the teachers’ assessment and scoring policies could be attributed to the grading system in the Iranian education system, which is based on a scale of 0–20. This scale induces a sense of anxiety and, at times, unhealthy competition amongst Iranian students (Arani et al., 2012; also see Romanowski, 2004).

In this study, personality trait was the second most important criterion making a teacher (in) effective in the eyes of the students. This finding supports those of some previous studies (Brosh, 1996; Curran and Rosen, 2006; Park and Lee, 2006; Babai Shishavan and Sadeghi, 2009; Barnes and Lock, 2010), which demonstrated that students perceived personality traits as a key characteristic of an effective teacher. Benson et al. (2005, p. 238) maintain that professors need to exhibit certain characteristics such as “having a good personality” to establish rapport with their students. Granitz et al. (2009), also argue that teachers’ personality as one of the three categories of what they call antecedents of rapport, with the other two being approach (i.e., availability of the professor) and homophily (i.e., the tendency of people to associate and bond with those who are similar to themselves). It is, therefore, very important for universities to consider the personality traits when hiring academics.

The extant literature shows that teachers’ pedagogical knowledge is a significant criterion when students evaluate their teachers (Hill et al., 2003; Faranda and Clarke, 2004; Barnes and Lock, 2010; Gruber et al., 2010; Benekos, 2016); our study echoes that finding, meaning that the students put special emphasis on the teachers’ instructional skills. The findings also shed light on the issue that teaching methodology of the teachers in the class is a critical concern importance. The students in our study found it difficult to follow the teaching style of those teachers who lack interactions with students in class; they did not wish their teachers to present the content of the course by simply reading off the PowerPoint slides without engaging students in the process of learning. A Ph.D. student of Philosophy major complained, “if teaching is in this way (reading off the slides without exemplification, explanation and students engagement), why can’t we just read the slides ourselves at comfort of our home and not bother with attending the class.” As a general rule, experienced teachers provide their students with the complementary explanation regarding the materials taught in the classroom and try to involve students in the process of learning. Similarly, in pursuit of what was reported by Singh et al. (2021), it is justified to strongly support that a competent teacher has impeccable subject matter knowledge, proficiency in both general and content-specific teaching methodology, and hands-on teaching functionality in order to live up the groundwork for teaching excellence.

Much to the researchers’ surprise, communication skills such as having a good rapport with students received the lowest frequency amongst the eight categories of the characteristics of an effective university professor. This finding contrasts those of Reichel and Arnon (2009) and Sybing (2019), in which the researchers singled out teachers’ ability to have a good rapport and interaction with students as one of the main characteristics of an effective university professor. The lowest priority for communication skills may indicate a highly score-based nature of the teaching system in Iran, which has resulted in damage to students’ creativity and absence of exposure to higher cognitive skills (Kakia and Almasi et al., 2008; Arani et al., 2012). The students’ disinterest in this category may also stem from the professors’ obsession with increasing the quantity of their publications in an attempt to climb the academic ladder. Many tenure track professors get tenure by publishing and this mentality can prevent them from investing their time and effort into developing interpersonal relationship with their students. Binswanger (2015), believes that teachers’ inability to connect with their students can lead to students’ dissatisfaction. More than two decades ago, Palmer (1998), warned that connectedness is undermined at the expense of constructivism and teaching techniques; in other words, good teachers should be characterized by a capacity of connectedness than their pedagogical knowledge and skills:

Good teachers possess a capacity for connectedness. They are able to weave a complex web of connections among themselves, their subjects, and their students so that students can learn to weave a world for themselves. The methods used by these weavers vary widely: lectures, Socratic dialogues, laboratory experiments, collaborative problem solving, and creative chaos. The connections made by good teachers are held not in their methods but in their hearts- meaning heart in its ancient sense, as the place where intellect and emotion and sprit and will converge in the human self (p. 11).

Binswanger (2015), adds this phenomenon (students’ dissatisfaction) can also be seen in European universities where the length of studies, increasing dropout rates, outdated curricula, and mediocre research performance have often been criticized. Lindbeck and Darnell (2008), believe that “for colleges and universities to develop successful, contributing faculty members, sustained orientation and on-going support for new faculty must become a part of each institution’s culture” (p. 10).

This study suffers from some limitations, which we hope future research will address. First, the study is confined to the context of university and the researchers urge caution when extrapolating the findings of this study to other contexts such as secondary education schools and institutes in or out of Iran. Second, the data was obtained from a secondary source, and we suggest future researchers use primary data to reach a better and deeper understanding of students’ perceptions of an effective university professor. Third, university teachers’ performance can be affected by some institutional factors such as faculty development programs, guidance from teaching excellence center, administrative support and so forth. These extraneous factors were not taken into account in this study and future studies should consider adding them as potential factors contributing to teacher and teaching efficacy. Fourth, despite the broad scope of perspectives examined in this study (i.e., students’ viewpoints from a variety of fields), it is recommended that future research classify these perspectives based on the students’ specific fields. Students’ opinions about qualities of an effective teacher may be influenced by their field of study. One final shortcoming was that the majority of the comments were made by the BA students, and the MA/MSc and Ph.D. students’ comments were not that frequent. A comprehensive understanding of effective teachers requires examining undergraduate and graduate students’ evaluatory comments.

Conclusion

There exists a huge literature on the characteristics of the effective teachers from the perspectives of either teachers or students (Khojastehmehr and Takrimi, 2008; Maria and Jari, 2013; Rasool et al., 2017). Studies have also been conducted to determine how and to what extent students and teachers’ standpoints on an effective teacher converge or diverge (Al-Mahrooqi et al., 2015). The main problem with many of these studies is that they have investigated characteristics of an effective teacher from the viewpoint of students in just one field of study, a shortcoming which limits the generalization of their findings to other academic disciplines. The distinctive feature of the present study is its comprehensiveness in considering the characteristics of an effective teacher from a wider population, that is, university students from different fields of study. As such, the findings of this study enjoy greater generalizability and can have cross-disciplinary implications and contributions. It should be pointed out that there are likely to be some discrepancies between students and teachers’ evaluations of an effective teacher, and some of the teachers whose evaluations made up the data of our study might not agree or be satisfied with those evaluations. These discrepancies might originate from different values, and beliefs students and teachers have toward learning and teaching. Further, as acknowledged by Murray (2021), the two yardsticks of “willingness to learn” and “motivation to teach” contribute to the conceptualization of a “growth” or a “can-do” mindset that might shape how students and teachers perceive a promising teacher. Examination of the students’ comments seems to indicate that they mostly prefer the teachers who are not strict with their classroom rules and who are pretty generous when scoring student work. This may go against the beliefs of those teachers who are disciplined and knowledgeable in their field of study and who believe students should earn their scores by merit. We conclude this study by suggesting that faculty development initiatives, whether at university, department, and individual teacher level, be designed in which students’ attitudes and perceptions of teaching effectiveness in higher education are incorporated not only to improve the education quality students receive but also to realize the higher education goals including democratization of advanced education.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

MN conceived the research topic, outlined the research design, supervised the whole process of the preparation of the article, read and commented on the manuscript several times, and submitted the manuscript to the journal. AM collected the data, wrote the initial drafts of the article. AM and MR revised the article based on MN comments. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ http://en.sbu.ac.ir/Pages/SBU-History.aspx, accessed in May 2020.

References

Al-Mahrooqi, R., Denman, C., Al-Siyabi, J., and Al-Maamari, F. (2015). Characteristics of a good EFL teacher: Omani EFL teacher and student perspectives. SAGE Open 5, 1–15. doi: 10.1177/2158244015584782

Alzeebaree, Y., and Zebari, I. (2021). What makes an effective EFL teacher: High school students’ perceptions. Asian ESP J. 2021:3887039.

Arnon, S., and Reichel, N. (2007). Who is the ideal teacher? Am I? Similarity and difference in perception of students of education regarding the qualities of a good teacher and of their own qualities as teachers. Teach. Teach. 13, 441–464. doi: 10.1080/13540600701561653

Arani, A. M., Kakia, M. L., and Karimi, M. V. (2012). Assessment in education in Iran. SAeDUC J. 9, 1–10.

Babai Shishavan, H., and Sadeghi, K. (2009). Characteristics of an effective English language teacher as perceived by Iranian teachers and learners of English. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2, 130–143.

Barnes, B. D., and Lock, G. (2010). The attributes of effective lecturers of English as a foreign language as perceived by students in a Korean university. Austr. J. Teach. Educ. 35, 139–151.

Bell, T. R. (2005). Behaviors and attitudes of effective foreign language teachers: results of a questionnaire study. For. Lang. Ann. 38, 259–270. doi: 10.1111/flan.2005.38

Benson, T. A., Cohen, A. L., and Buskist, W. (2005). Rapport: its relation to student attitudes and behaviors toward teachers and classes. Teach. Psychol. 32, 237–239. doi: 10.1207/s15328023top3204_8

Beran, T., and Violato, C. (2005). Ratings of university teacher instruction: how much do student and course characteristics really matter? Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 30, 593–601. doi: 10.1080/02602930500260688

Benekos, P. J. (2016). How to be a good teacher: passion, person, and pedagogy. J. Crim. Just. Educ. 27, 225–237. doi: 10.1080/10511253.2015.1128703

Benaquisto, L. (2008). “Codes and coding,”. In The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods Ed. L. Given, 86–89). (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage).

Binswanger, M. (2015). “How nonsense became excellence: Forcing professors to publish,” In Incentives and performance. Governance of Research Organizations eds I. Welpe, J. Wollersheim, S. Ringelhan, and M. Osterloh 19–32. (Berlin: Springer).

Blaikie, N. (2018). Confounding issues related to determining sample size in qualitative research. Internat. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 21, 635–641. doi: 10.1080/13645579.2018.1454644

Borg, S. (2006). The distinctive characteristics of foreign language teachers. Lang. Teach. Res. 10, 3–31. doi: 10.1191/1362168806lr182oa

Brosh, H. (1996). Perceived characteristics of the effective language teacher. For. Lang. Ann. 29, 125–136.

Catano, V. M., and Harvey, S. (2011). Student perception of teaching effectiveness: development and validation of the evaluation of teaching competencies scale (ETCS). Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 36, 701–717. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2010.484879

Church, R. M. (2002). The effective use of secondary data. Learn. Mot. 33, 32–45. doi: 10.1006/lmot.2001.1098

Clayson, D. E., and Sheffet, M. J. (2006). Personality and the student evaluation of teaching. J. Market. Educ. 28, 149–160.

Curran, J. M., and Rosen, D. E. (2006). Student attitudes toward college courses: An examination of influences and intentions. J. Mark. Educ. 28, 135–148.

Delucchi, M. (2000). Don’t worry, be happy: Instructor likability, student perceptions of learning, and teacher ratings in upper-level sociology courses. Teach. Soc. 28, 220–231. doi: 10.2307/1318991

Drapeau, M. (2002). Subjectivity in research: Why not? But. Q. Rep. 7, 1–15. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2002.1972

Dworkin, S. L. (2012). Sample size policy for qualitative studies using in-depth interviews. Archiv. Sex. Behav. 41, 1319–1320. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-0016-6

Faranda, W. T., and Clarke, I. (2004). Student observations of outstanding teaching: Implications for marketing educators. J. Mark. Educ. 26, 271–281.

Frisby, B., Berger, E., Burchett, M., Herovic, E., and Strawser, M. (2014). Participation apprehensive students: the influence of face support and instructor–student rapport on classroom participation. Comm. Educ. 63, 105–123. doi: 10.1080/03634523.2014.881516

Glaser, B. G. (1963). Retreading research materials: the use of secondary analysis by the independent researcher. Am. Behav. Sci. 6, 11–14. doi: 10.1177/000276426300601003

Granitz, N. A., Koernig, S. K., and Harich, K. R. (2009). Now it’s personal: antecedents and outcomes of rapport between business faculty and their students. J. Market. Educ. 31, 52–65. doi: 10.1177/0273475308326408

Gruber, T., Reppel, A., and Voss, R. (2010). Understanding the characteristics of effective professors: the student’s perspective. J. Market. Higher Educ. 20, 175–190. doi: 10.1080/08841241.2010.526356

Hill, Y., Lomas, L., and MacGregor, J. (2003). Students’ perceptions of quality in higher education. Qual. Assuran. Educ. 11, 15–20. doi: 10.1108/09684880310462047

Hughes, J., Robb, J. A., Hagerman, M. S., Laffier, J., and Cotnam-Kappel, M. (2022). What makes a maker teacher? Examining key characteristics of two maker educators. Internat. J. Educ. Res. Open 3, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedro.2021.100118

Inan, B. (2014). A cross-cultural understanding of the characteristics of a good teacher. Anthropologist 18, 427–432. doi: 10.1080/09720073.2014.11891561

Joseph, S. (2018). Effective professors: An insight into their philosophy and practice. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 5, 276–282. doi: 10.14738/assrj.53.4302

Kakia, L., Almasi, A. (2008). “A comparative study of effectiveness’s evaluation of qualitative and quantitative assessment methods on learning, anxiety and attitude of primary pupils of Tehran city,” in conference session Formative Assessment National Conference (Khoramabad: Lorestan’s Education Organization).

Khojastehmehr, R., and Takrimi, A. (2008). Characteristics of effective teachers: perceptions of the English teachers. J. Educ. Psychol. 3, 53–66.

Lee, H. H., Kim, G. M. L., and Chan, L. L. (2015). Good teaching: what matters to university students. Asia Pacif. J. Educ. 35, 98–110. doi: 10.1080/02188791.2013.860008

Liando, N. V. F. (2015). Students’ vs. teachers’ perspectives on best teacher characteristics in EFL classrooms. TEFLIN J. 21, 118–136. doi: 10.15639/teflinjournal.v21i2/118-136

Lindbeck, R., and Darnell, D. (2008). An investigation of new faculty orientation and support among mid-sized colleges and universities. Acad. Leaders. 6, 1–6.

Lisa, E., Kim, L.O., and Kathryn, A. (2021). What makes a great teacher during a pandemic? J. Educ. Teach. 2021, 1–3. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2021.1988826

Lupascu, A. R., Pânisoarã, G., and Pânisoarã, I. O. (2014). Characteristics of effective teacher. Proced. Soc. Behav. Sci. 127, 534–538.

Maria, M. T., and Jari, M. (2013). Comparison of Nepalese and Finnish teachers’ perceptions of good teaching. Asian J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 1, 10–27.

Marshall, B., Cardon, P., Poddar, A., and Fontenot, R. (2013). Does sample size matter in qualitative research? A review of qualitative interviews in IS research. J. Comp. Inform. Syst. 54, 11–22. doi: 10.1080/08874417.2013.11645667

Murray, J. (2021). Good teachers are always learning. Internat. J. Early Years Educ. 29, 229–235. doi: 10.1080/09669760.2021.1955478

Mohajan, H. (2018). Qualitative research methodology in social sciences and related subjects. J. Econ. Dev. Env. People 7, 23–48. doi: 10.26458/jedep.v7i1.571

Mohammaditabar, M., Bagheri, M. S., Yamini, M., Rassaei, E., and Lu, X. (2019). Iranian EFL teachers’ perspectives of qualities of a good language teacher: does educational context make a difference? Cogent Educ. 6, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2019.1651442

Morrison, B., and Evans, S. (2018). University students’ conceptions of the good teacher: a Hong Kong perspective. J. Furth. High. Educ. 42, 352–365. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2016.1261096

Mruck, K., and Breuer, F. (2003). Subjectivity and reflexivity in qualitative research—The FQS issues. Forum: Q. Soc. Res. 4, 1–13. doi: 10.17169/fqs-4.2.696

Murphy, P. K., Delli, L. A. M., and Edwards, M. N. (2004). The good teacher and good teaching: Comparing beliefs of second-grade students, pre-service teachers, and in-service teachers. J. Exp. Educ. 72, 69–92. doi: 10.3200/JEXE.72.2.69-92

Murray, J., and Kosnik, C. (2011). Academic work and identities in teacher education. J. Educ. Teach. 37, 243–246. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2011.587982

Orhon, G. (2012). The effect of teachers’ emotional and perceptual characteristics on creative learning. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 46, 3074–3077. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.013

Park, G. P., and Lee, H. W. (2006). The characteristics of effective English teachers as perceived by high school teachers and students in Korea. Asia Pacific Educ. Rev. 7, 236–248. doi: 10.1007/bf03031547

Palmer, P. J. (1998). The courage to teach: Exploring the inner landscape of a teacher’s life. Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass.

Rasool, G., Mahboob, U., Sajid, M., and Ahmad, S. (2017). Characteristics of effective teaching: a survey on teacher’s perceptions. Pakist. Oral Dent. J. 37, 58–62.

Ratner, C. (2002). Subjectivity and objectivity in qualitative methodology. Forum: Q. Soc. Res. 3, 1–8.

Reichel, N., and Arnon, S. (2009). A multicultural view of the good teacher in Israel. Teach. Teach. 15, 59–85. doi: 10.1080/13540600802661329

Richmond, A. S., Berglund, M. B., Epelbaum, V. B., and Klein, E. M. (2015). A+(b1) Professor–student rapport+(b2) humor+(b3) student engagement=(Y) Student ratings of instructors. Teach. Psychol. 42, 119–125. doi: 10.1177/0098628315569924

Robinson, O. C. (2013). Sampling in interview-based qualitative research: a theoretical and practical guide. Qual. Res. Psychol. 11, 25–41. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2013.801543

Romanowski, M. H. (2004). Student obsession with grades and achievement. Kappa Delta Pi Record 40, 149–151. doi: 10.1080/00228958.2004.10516425

Rossetti, J. and Fox, P. G. (2009). Factors that make outstanding professors successful in teaching: an interpretive study. J. Nurs. Educ. 48, 11–16. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20090101-09

Singh, C. K. S., Mostafa, N. A., Mulyadi, D., Madzlan, N. A., Ong, E. T., Shukor, S. S., and Singh, T. S. M. (2021). Teacher educators’ vision of an ‘ideal’ teacher. Stud. Engl. Lang. Educ. 8, 1158–1176. doi: 10.24815/siele.v8i3.19355

Sotto, E. (2011). When teaching becomes learning: A theory and practice of teaching (2nd ed.). London: Continuum Education.

Starcher, K. (2011). Intentionally building rapport with students. Coll. Teach. 59:162. doi: 10.1080/87567555.2010.516782

Su, F., and Wood, M. (2012). What makes a good university lecturer? Students’ perceptions of teaching excellence. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 4, 142–155. doi: 10.1108/17581181211273110

Sybing, R. (2019). Making connections: Student-teacher rapport in higher education classrooms. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. 19, 18–35. doi: 10.14434/josotl.v19i5.26578

Vasileiou, K., Barnett, J., Thorpe, S., and Young, T. (2018). Characterizing and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med. Res. Method. 18, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7

Webb, N. G., and Barrett, L. O. (2014). Student views of instructor-student rapport in the college classroom. J. Scholarship Teach. Learn. 14, 15–28. doi: 10.14434/josotl.v14i2.4259

Keywords: academic disciplines, effective professor, teacher evaluation, higher education, university

Citation: Nushi M, Momeni A and Roshanbin M (2022) Characteristics of an Effective University Professor From Students’ Perspective: Are the Qualities Changing? Front. Educ. 7:842640. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.842640

Received: 23 December 2021; Accepted: 07 March 2022;

Published: 30 March 2022.

Edited by:

Sandra Fernandes, Portucalense University, PortugalReviewed by:

Eva Fernandes, University of Minho, PortugalProdhan Mahbub Ibna Seraj, American International University-Bangladesh, Bangladesh

Anabela Carvalho Alves, University of Minho, Portugal

Copyright © 2022 Nushi, Momeni and Roshanbin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Musa Nushi, m_nushi@sbu.ac.ir

Musa Nushi

Musa Nushi