- Department of Science Education, Faculty of Humanities and Educational Sciences, University of Jaén, Jaén, Spain

The following article inquires how introducing the gender category, feminism theories, and intersectionality into social sciences education, especially regarding historical thinking development, could be key for the construction of a more critical and egalitarian future. The main research problem is knowing how the use of the gender category is included, or not, in the development of historical thinking in pre-service teacher beliefs and how it could condition them when they work on historical and social problems in the classroom. The main objective is to analyze the historical thinking development in pre-service Spanish teacher students and their capacity for constructing critical discourses with a gender perspective. Pre-service teachers of five Spanish universities (of the Primary and Secondary Education Degree) were asked about a report from a digital newspaper version that forces them to use historical thinking and to consider gender stereotypes and prejudices. Their responses were analyzed both qualitatively and quantitatively. The results indicate that pre-service teachers are not able to identify their own gender roles and prejudiced attitudes when they attempt to explain a social problem and they propose solutions, even when they could verify that there was another manner to understand this report. Hence, this research highlights the relevance of implementing feminism, intersectionality, and gender category for historical thinking development since these future teachers need to work around democratic culture competences. By contrast, not including this perspective will lead to them still maintaining historical thinking and democracy configured on hegemonic, heteropatriarchal, sexist, and Eurocentric cultural models.

Introduction

In the 21st century, our societies are trying to contribute to the development of the Sustainable Development Goals and, at the same time, to achieve concrete targets by 2030 (in our research, it is linked to SDGs 4 and 5). Besides, the 2030 Global Education Agenda “recognizes that gender equality requires an approach that ensures that girls and boys, women and men not only gain access to and complete education cycles, but are empowered equally in and through education” (UNESCO, 2019). For this reason, we can continue to affirm that in our initial teacher training centers, there is still a strong epistemic androcentrism (Maffía, 2007, p. 64).

Feminist epistemologies, since the 1980s, have been providing the configuration of specific critical theories of knowledge, at the same time that they were facing multiple acts of structural violence within the system itself for its acceptance. These acts of violence are still present today, since we could say that what Puleo García (2005) calls “patriarchy of consent” and an “ice law” (or mistreatment through silence) of the gender perspective in the education system have been imposed, relegating it to a second place, diluting the contributions of feminist epistemology and its demands, questions, and proposals, without incorporating it into practice in the classroom. However, seemingly, it is true that educational activities have been increased in the area of gender equality, but as Cobo Bedía (2005, p. 250) pointed out, “In recent years, the notion of gender detached from feminism is being used in both academic and political spheres, despite of the fact that this concept emerges as an instrument for the analysis of feminist theory.” Thus, in the face of the strengthening of feminist epistemologies, the transfer of their advances to the educational field has been largely diluted in actions concentrated in the months of March and November (coinciding with the anniversaries of 8 March and 25 November), the incorporation of some elements of women’s history in textbooks or the curricula highlighted in the equality plans of schools, and the emergence of standard phrases in curriculum programming which, despite being subject to constant evaluations by quality agencies, do not analyze or evaluate the instruments with which they are applied or the students’ learning outcomes.

Nevertheless, feminist theories have shown us that adopting an epistemological position also implies adopting an ethical position. The incorporation of the intersectional feminist perspective (Crenshaw, 1989, p. 139; 1991) made us aware of the discriminations of binarism present in epistemological systems and in the use of logical principles when we ontologize, interpreting as exclusionary and susceptible to being ignored (by the idea of no confrontation of ideas) all social realities that did not respond to such binary explanation. Hill Collins (2000) made us think of that “matrix of domination” that has organized and ranked our vision of the world around those who were historical subjects and held power and that, besides, was expressed through different local manifestations from particular historical and social configurations. Thus, structural, disciplinary, and hegemonic dominance (which, for example, make it possible to socially establish binary gender roles as unique and valid) and the interpersonal domain that shapes the life trajectory of people and groups have not only been present in our daily life and our construction of our own identity but they also appear in the construction of historical narratives selected to construct school history.

We would have to assume, therefore, that the analytical categories used that lead us to understand societies, make critical judgments, and participate as part of active citizenship should be reviewed to show their interpretative biases (Giddens, 2000) of space and time in which they established their hegemonic meanings. In this way, for instance, feminism went from talking about the importance of incorporating “the woman” as a historical subject to analyzing it from the diversities of women, breaking the universal logic of the History of Man, where the concept of man was in singular, allegedly referring to an eminently hegemonic generic male.

This is where the resistance becomes deeper in academia (Ballarín Domingo, 2017) because it involves rethinking absolute truths, interpretations constructed on the basis of logic, and also subjective interpretations generated by people who approach historical knowledge and/or reproduce it in other dissemination channels such as cinema, the specialized press, video games, and educational proposals, which now, in the face of the hegemony of epistemic androcentrism, are where invisibilized stories and their motives are posed to us.

This questioning, moreover, and in a concrete way when our gender identities are historical constructions, challenges us personally and professionally. There are already some studies, besides what is shown, for men, to speak of masculinities; therefore, male hegemony in history and leading them to deconstruct their meanings is linked more to the personal than to the professional perspective in spite of women, which is reflected in the personal but also and in a more epistemic way, in the professional (Elipe et al., 2021).

For all these reasons, it is no longer a question of learning and/or teaching history but of contributing to the development of historical thought (Seixas and Morton, 2013) and therefore, of attending to contexts (temporal and spatial) and to the notions of causality and change (we have hardly worked on the subject of historical time), but also learning to analyze when, who, and based on what research questions were obtained the results that shaped each moment and, even today, history.

How Is Research on the Development of Historical Thought With a Gender Perspective Materialized?

Gender equality is not only a matter of social justice but also affects the performance of teaching and research1 (EU, H2020, 2018) and not only in universities but also in the case of initial teacher education. It is a look capable of detecting gender asymmetries in the past and the present (Díez-Bedmar and Fernández Valencia, 2021).

Díez-Bedmar and Ortega Sánchez (2021) analyzed areas of research, innovation, and action that are being developed in our context and that materialized in the following parts:

• Research studies on the visibility of women and their roles from different sources and, normally, linked to the historical temporality of these sources (both from the premises of the history of women and addressing it with a gender perspective analysis).

• Research studies on the student and teacher’s perceptions, both with regard to the perception of women as historical subjects and gender mainstreaming.

• Research studies on curriculum elements and their application, educational practices, resources used (mostly textbooks), assessment, and learning outcomes and methodologies used (including co-education) linked both to the inclusion of women as invisible subjects and to the gender perspective.

• Research studies linked to the rupture of a binary and unitary gender construction and, in that sense, the inclusion of the theory of intersectionality, the construction of alternative masculinities, or the incorporation of diverse gender-generic identities.

All these research studies highlight the need to continue analyzing and investigating how we are contributing to the development of historical thinking with a gender perspective in initial teacher education students. The purpose, or rather the desire, is that in the future, the category of gender thinking is used in contextualizing its implications in each historical situation to understand how historical narratives and narratives around social relations were produced, the hierarchies of power, and the gender roles established by each society. Thus, they will be aware in their decision making about what social sciences to build in current classrooms for a future citizenship that neither should nor can perpetuate gender biases in the construction of science, that is to say, to develop the teaching competence in gender (Díez-Bedmar, 2019) that, although it is demanded by organizations such as UNESCO (2015), becomes evident and is visible only when studies make specific reference to equality and gender [see case study cover Meeting our commitments to gender equality in education (2018)2 (Table 3) versus study cover Migration, displacement and education: Building bridges, not walls (2019)3 ].

It is not surprising, therefore, that as Ortuño Molina and Fredrik (2021) remind us in their work “Swedish and Spanish pre-service teachers’ assumptions on gender inequality in temporal perspective,” the curriculum is mostly not developing historical thinking with a gender perspective, but tends to address gender inequality as a current social problem, although a third of the narratives analyzed do not even “see or mention problems of gender inequality at present” (p. 171). Possibly, therefore, in the face of the discouragement that appears in the students with regard to the teaching of history, since they are not recognized in the past that is presented to them, we see how they act, think, and position themselves when confronted with realities that have an equal dimension in the present and the future (Díez-Bedmar and Fernández Valencia, 2021).

But, could a teacher who does not implement an intersectional gender category analysis develop democratic culture competences?

Materials and Methods

According to Seixas and Morton (2013, p. 7), the student’s historical thinking “is rooted in how they tackle the difficult problems of understanding the past, how they make sense of it for today’s society and culture, and thus how they get their bearing in a continuum of past, present, and future.” The Council of Europe model for democratic culture (2018) includes the following competences: values, attitudes, skills, knowledge, and critical understanding. We understand that it is impossible to be a good democratic citizenship that develops critical historical thinking without including a gender perspective when society is analyzed.

That research arises from a research project financed by the Ministry of Economy, Industry, and Competitiveness of Spain (R&D EDU2016-80145-P), with the participation of several different Spanish universities, in whose context different research instruments were designed and implemented in the Primary Education degree and Secondary Education master degree (Castellví et al., 2020).

This study analyzes the discourses constructed by the students based on one of the activities (the fourth) on one of the questionnaires4 implemented. This questionnaire, which provided us with quantitative and qualitative data, inquires into the students’ capacity to analyze different news items and develop a critical discourse on controversial issues with a strong value skew. The activity where students had to make a critical analysis of a newspaper report published on 21/08/2015, 10:10 a.m., has been chosen because the topic is related to the gender perspective: gender roles, taking care of minors, responsibilities, inter alia, and because then, on the same questionnaire, they found another report published on 21/08/2015, 20:32 p.m., on the same newspaper and topic, but with more information.

Activity 4.a

In the following part, a piece of news from the newspaper “La Vanguardia,” from 2015,5 (Figure 1) is shown, which can be found on the following web link: http://www.lavanguardia.com/sucesos/20150821/54435940954/encierran-bebe-caja-fuerte-habitacion-hotel.html.

What is your opinion on this news?

Activity 4.b

For further information on this report and its outcome, please consult the following web link: http://www.lavanguardia.com/sucesos/20150821/54435954170/bebe-caja-fuerte-jugando-escondite-hermanos.html.

• Has your opinion changed about the parents? Why?

The complete questionnaire data were collected through a series of activities and open-ended questions which they filled out individually in, at most, 45 min. All the questions gave the possibility of consulting any kind of digital source to verify or complete the news item or to seek other sources that contradict it.

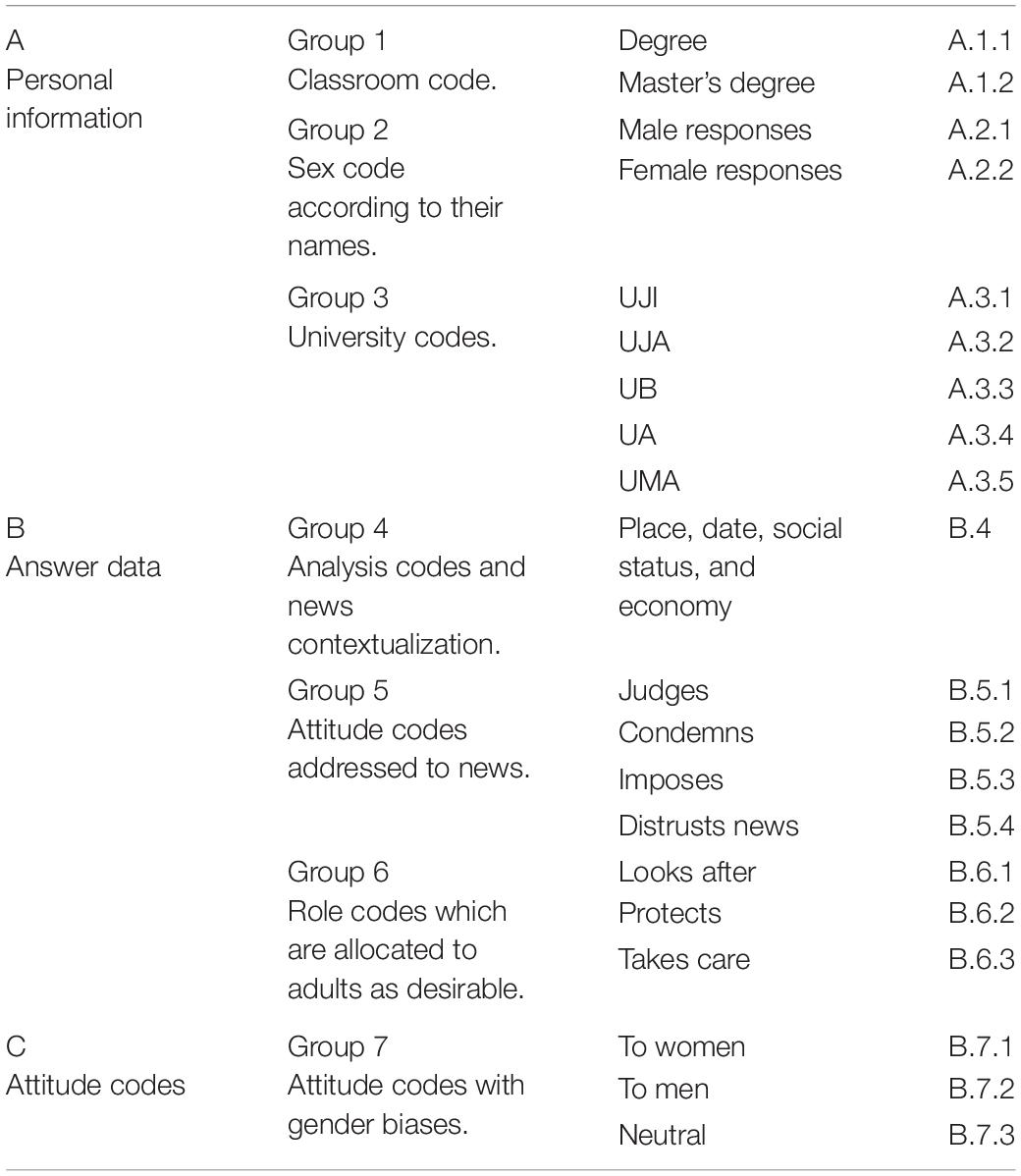

The responses obtained for that activity (n = 296 students in the third year of the Primary Education degree and 67 students in Secondary) have been analyzed, making two groups. On the one hand, students of the third year of the Primary Education degree, and on the other hand, students of the master of teacher training, were assigned different codes in Atlas.ti software (version 9).

We performed a triple analysis:

(a) Direct coding of responses after thorough reading.

(b) Axial coding, obtaining categories from the responses collected.

(c) Selective coding, construction of central concepts that rank knowledge and generate theory.

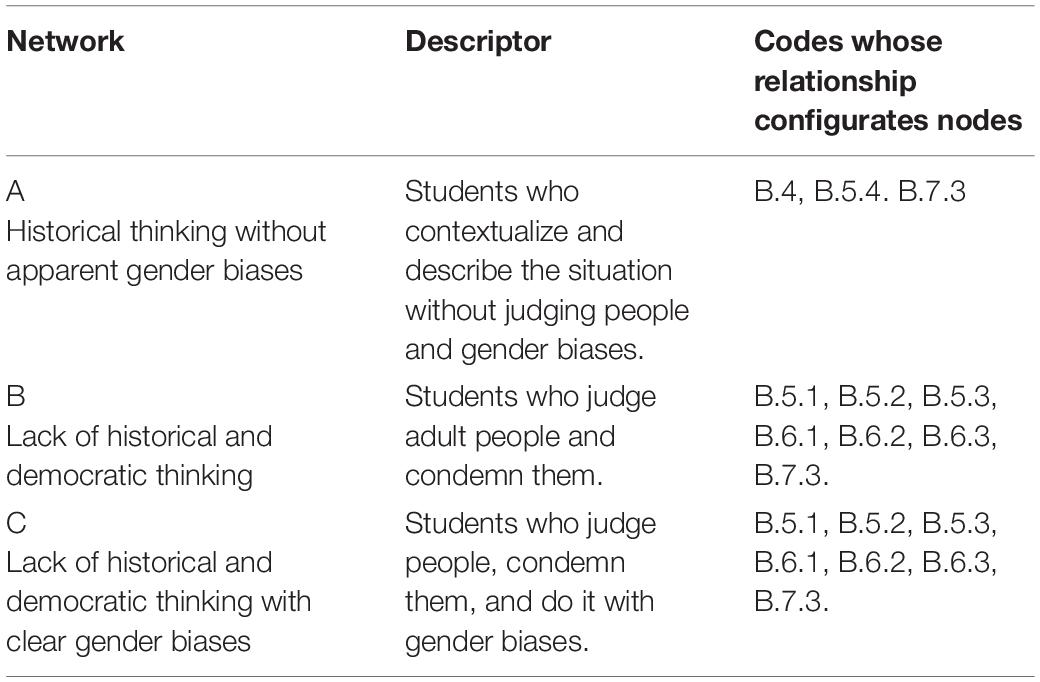

With these codes, we have created three networks that, following the Grounded Theory (Strauss and Corbin, 2002; Carrero et al., 2012), have enabled us to establish three profiles according to groups 4–7 of codes for the deconstruction of their own discourses and the categorization of their responses.

Our mission is to determine if students apply a gender perspective or if gender differences appear. How do they interpret society? Do they do it with gender biases? Is there any difference among degree and master degree students?

Results

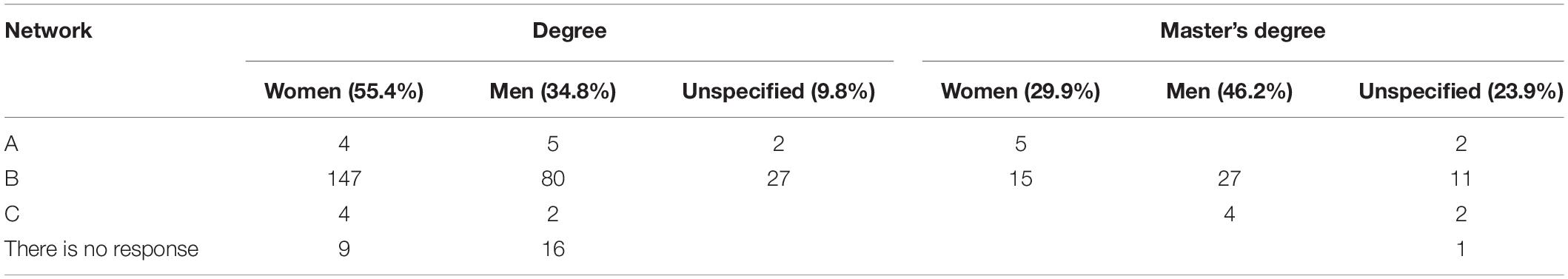

The nodes generated through Atlas.ti. (Tables 1, 2, 3) return the following results:

Responses to Activity 4.a

Examples of Network A

“It expresses it in a grotesque way and by the morbid, giving data that besides possible identification of ‘social class’ makes you think a would not have to happen to you” (Degree, Fem, UJA, 40); “Well I think that what they count is very brief and missing data” (Degree, Fem, UJI, 37); “This is sensational news, which tries to gain visibility ‘clickbait’ without answering or verifying the information before verifying it” (Master, s/n, UMA, 30).

Examples of Network B

Before setting out some examples, we must notice that the news in no case refers to a heterosexual couple (speaks of couple and parents), despite which, 98.35% of the total responses (363) assume that it is a father and a mother, expressing this duality either in the response to question 4.a or 4.b, indicating a clear conception bias toward the traditional family of the patriarchal and heterosexual model. On the other hand, although the responses do not differentiate causes or consequences for the two parts of the couple (who have been assumed to be a father and a mother), since they use the male generic parents (77%), parents (11%, although it is not indicated in any case that they are biological children), speak of both (7%), or do not put a subject (5%), their narratives do have a clear sex-gender bias.

The men’s responses tend to be less explanatory and more forceful; they judge with more violence and, in most cases, impose penalties for parents: prison (70%), perpetual (50%), or even death penalty (37%). “The parents should receive some kind of sanction” (Master, Mas. UAB, 28); “May the forced labor return, life imprisonment and cut stone for life” (Master, s/n, UMA, 37); “It seems to me a terrible news and a lack of respect for the deal, are made by two monsters, since they have no other name and deserve a death or life imprisonment” (Degree, Mas. UJI, 21). In some cases, the responses at least indicate that if they did not want to have children, they could have taken precautions or given them up for adoption (24%), which is a more common response in Bachelor’s degree than in Master’s degree students, assuming that it was the will of the parents to get rid of minors.

According to women’s responses, whose narratives contain more argumentation and reflection, they state that there must be a psychological problem behind it (74%) because otherwise they would not understand it. You have to propose measures before you get to that situation (“put means” 46% and give up for adoption 64%, the first being the most common option in the Bachelor’s degree and the second in the Master’s degree students, which is also an indication of the personal moment in which they are in function of age and tells us about the importance of this intersectional variable). As for sanctions, they tend more to ask that they do not continue to care for minors (47%), with very similar percentages in both Bachelor’s degree and Master’s degree students.

Some examples are presented in the following lines: “that couple is not mentally capable of holding a baby in their hands” (Degree, Fem, UJA, 53); “I believe that to be parents you should pass some psychological test or something similar to know if you are or not trained to care for your child because then things like this news happen” (Degree, Fem, UJI, 18); “A possible solution might have been adoption, as many couples cannot have babies and would have given the child a chance” (Degree, Fem, UJI, 28); “First, I would have taken custody of the parents, since they are not qualified to have a child.” (Degree, Fem, UJA, 53). Only in 25% of cases, they refer to punishment or prison.

Examples of Network C

Although there are few cases detected, since the news is written with the subjects “a couple” and “parents,” the students have tended to respond in the same terms; we see how 2% of the Bachelor’s degree students’ responses (mostly women) and 9% of the Master’s degree students’ responses (mostly men) have given us responses that focus on women or men. In both cases in which men are placed, these are responses of women and are linked to the hegemonic role of male protection [“My opinion regarding that news is that this man has a problem, and should not have the right to do that to a helpless baby” (Degree, Fem, UJA, 32); “We must raise awareness and educate society about what it means to have a child and how it really is the figure of a good father” (Degree, Fem, UJI, 29)]. The rest of the cases focus on women: they point out that “there are women who should not be mothers” (Degree, Mas. UJA, 19), blame them “she by mistake seems to leave a child in the safe.” (Degree, Fem, UJA, 43); “it is necessary to make people aware that having a baby is very important and that if you do not have minimum conditions to ensure their care should not be allowed to give birth” (Degree, n/s, UMA, 49), or directly hold them responsible for having had children without wanting them and point out other options: “if you don’t want a child there are many more options, beforehand, you can abort, but if not then you can always reach adoption” (Master, s/n, UMA, 36); “in my opinion if you don’t want to have a child you have plenty of options. The first is abortion that is legal in many states” (Degree, Fem, UJI, 40). There is no case where women hold men responsible, nor do women point out that they could have taken precautions or that a vasectomy could have been performed.

Responses to Activity 4.b

In fact, when they access the second story and read that the children were playing hide-and-seek and they were not abandoned by the parents, it is worrying to see how 10 Bachelor’s degree students who answered the first one do not do it for the second, and only 12 students acknowledge having misjudged the parents. “Yes, it has changed because it was an accident and there was no intention of mistreatment or abandonment” (Degree, Mas. UJA, 61). The rest, although in some cases they recognize that the new headline changes the meaning of the news, continue to judge the adults (92.5%). Among these responses, we find some that continue to mark gender biases: “No, I think it’s false. And in case it was real, a mother doesn’t let a little boy play alone with his siblings. It should be aware of them all the time, as they are children and children are put in danger with everything (Degree, Fem, UJI, 52)”; “In addition, no parent (good parent) would leave the Hotel without making sure that the whole family is together” (Master, Mas. UJA, 47), with the same connotations mentioned above. In the case of the Master’s degree students, only five responses acknowledge prejudgment, while 95.5% continue to judge the behavior of the adults.

Discussion

Seixas and Morton (2013) propose “The Big Six Historical Thinking Concepts”: historical significance, evidence, continuity and change, cause and consequence, historical perspectives, and ethical dimension. This study exposes that with a particular relevant social problem, pre-service teachers select what is important (historical significance) by taking into consideration emotions rather than the critical analysis of information and that they also do so from their cultural conceptions. In this case, the elderly and those who are not parents assume that it is a heteropatriarchal family, and in particular, the mothers have to take care of the minors. The cultural and sex–gender intersection is omitted. This is true for both undergraduate and master’s students (Networks B and C).

When we analyze the answers that are offered after visualizing the second report, which adds nuance and offers another perspective of the problem, it can be verified that the “how” is known like something of the past (the evidence) which is quite connected to the first opinion created (which responds to hegemonic parameters). Moreover, it is difficult to modify or contrast with other realities, which can be linked to resistances to introducing theories such as feminism in historical interpretation.

In connection with the concepts of continuity and change (which serve to give meaning to historical processes) and cause and consequence (why events take place and what their consequences are), the study shows us that, in general, instead of analyzing processes, pre-service students tend to analyze information from a direct causality, although women are more reflective, try to seek explanations, and tend to establish other causalities. The direct and hierarchical responsibilities are established around age and who has to do what (older people have to watch and care for minors and therefore the consequence is their fault). At no time, or when the information is checked, is there a shared responsibility established. This shows us a lineal and hierarchical consequence in the historical explanation that does not allow other interpretations (Network B and answers after contrasting the information).

Finally, the most relevant thing is that whether the historical perspectives are analyzed (how people can better understand the situations and people of the past) and the ethical dimension (which leads us to make decisions in the present) we can observe where value judgments from the present and from their first opinion regarding what happened are the predominant ones. Therefore, the historical perspective arises from perceptions marked by cultural hegemonic mandates as to who is responsible, what should have been done, or what punishment those who do not should have. The concept of guilt is very present in their answers, given in a clearly Judeo-Christian cultural context where heteropatriarchal relations predominate. In general, the responses in Network C show clear gender role biases associated with the responsibilities of adults and blame and make women more accountable, which shows the need to incorporate the intersectionality and gender perspective in initial teacher training so that future teachers can make democratic and equal ethical decisions in the development of historical thought.

As Castellví et al. (2019, p. 38) pointed out, “From the Didactics of Social Sciences, the concern for the interaction between emotions and reason is twofold: first, because social contents have an important emotional charge (identities, memory, social problems, etc.) which influence the processes of their teaching and learning; secondly, because it conditions the development of critical thinking and influences value judgements and social action” (see text footnote 5).

The present study shows that they are the emotions, expressed in the narratives of the students that predominate when faced with a socially relevant problem report story. They prejudge, sanction, and let themselves be carried away by emotions from their own position, without contrasting the information, without contextualizing or analyzing the data offered. Nor do they change their minds when they discover that there is another reading of the report that completely changes prejudiced behaviors. In addition, conducting a Critical Analysis of Feminist Discourse (Baxter, 2004, 2007), we appreciate how, far from being neutral, the responses of men and women are answered from the gender-generic roles assigned, which agrees with previous studies such as those of Kerr and Schmeichel (2018), which pointed out the existence of emotional divergencies as a function of sex, in the contributions to the digital debates on Twitter. Ortega-Sánchez et al. (2021, p. 15) also indicated that “how to identify the emotional mediating effects in the construction of social narratives and questioning the impact of hegemonic discourses on gender” should be taken into account. In this sense, the responses of the men confirm the results obtained in research on masculinities and co-education (Elipe et al., 2021).

Conclusion

Contrasting these results with those obtained by Díez-Bedmar reinforces the idea that the development of teaching competence in gender implies that one should “not only know, but also internalize and be aware of the consequences of their decision making, and that is why it involves long-term learning processes in which, gradually (depending on the starting point and the previous knowledge of each person) gender is internalized as a category of analysis and, from there, historical education with a gender perspective” (Díez-Bedmar, 2019, p. 115).

In this research, which analyzes both Bachelor’s degree and Master’s degree students’ responses, it is demonstrated that the emotions linked to the hegemonic sex-gender roles in our culture are stronger (in order to interpret a relevant social problem, which students have identified as a taking care issue) than the development of historical thinking competences. In fact, the supposed deep learning outcomes about historical thinking competences of Master’s students do not offer differences when their responses are analyzed looking for their intersectional and gender perspective on their critical narratives. Thus, these competences have not been developed through their academic formation.

Pace (2019) indicated the need to prepare training teachers for education concerning social problems, socially alive issues, and controversial topics within divided societies, considering the emotional variable as one of the most influential factors in their didactic treatment. While the work of Ortega-Sánchez et al. (2021, p. 13) point out how “The results that have been obtained have provided information on the influence of emotions and feelings that are socially constructed within the articulation of digital social narratives,” our study shows that these emotions should be approached from the perspective of feminism, analyzing their narratives and discourses with the category of gender thinking and attending to the theory of intersectionality, since they are intimately linked to sex roles.

This is what our patriarchal society has marked. As Díez-Bedmar and Fernández Valencia (2019) pointed out, asking questions with a gender perspective and knowing how to analyze the responses with a gender analysis is key in the training of teachers so that they can apply it in their professional field.

The lack of training offered by intersectional feminist epistemology as part of democratic culture competences sets a serious problem for democracy since, if future teachers are not able to challenge their own gender stereotypes and prejudices and how they are personally and professionally affected, they will not be able to work critically on the human and social sciences constructed, which are configured with heteropatriarchal models, sexist, Eurocentric, and based on hegemonic cultural models of hierarchical structures whose hegemonic narrative is based on exclusionary power configurations.

Moreover, as we have seen, despite having access to information that complements, adds nuance, explains, and contextualizes information, they are not able to identify their own prejudiced attitudes and maintain their discourses; therefore, they will be unlikely to be able to develop educational proposals, analyze materials and resources, and guide students to question the information they receive, with gender bias, every day. Feminism, intersectionality, and gender category appear to be essential for the development of historical thought and for the development of knowledge and critical understanding of society, if we do not want the citizenship of the future to assume messages based on stereotypes and prejudices are valid, unique, and truthful not only toward women but also toward diverse identities, perpetuating the systemic and structural gender violence present in our patriarchal and hierarchical system of current values and attitudes.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

MCD-B confirms being the primary author of the manuscript that has only been translated. The author has approved it for publication.

Funding

This study was the result of two research projects: teaching social sciences with gender perspective (research line of the author) and R&D EDU2016-80145-P, project subsidized by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness of Spain.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Pablo Cantero Castelló for his invaluable help in translating the text.

Footnotes

- ^ Topic description. The Horizon 2020 Regulation, Work Programme 2018–2019, Science with and for Society, SwafS-13-2018, Gender Equality Academy and dissemination of gender knowledge across Europe: http://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/portal/desktop/en/opportunities/h2020/topics/swafs-13-2018.html.

- ^ https://en.unesco.org/gem-report/2018_gender_review

- ^ https://en.unesco.org/gem-report/report/2019/migration

- ^ The full dossier can be consulted on https://ddd.uab.cat/pub/recdoc/2018/214742/EDU201680145P_literacidadcritica_gredics.pdf

- ^ The translation is ours.

References

Ballarín Domingo, P. (2017). >Se enseña coeducación en la universidad? Atlánticas Rev. Int. Estud. Fem. 2, 7–31. doi: 10.17979/arief.2017.2.1.1865

Baxter, J. (2004). Positioning Gender in Discourse: A Feminist Methodology. Londres: Palgrave Macmillan.

Baxter, J. (2007). “Post-structuralist analysis of classroom discourse,” in Encyclopaedia of Language and Education: Discourse and Education, Vol. 3, eds M. Martin and A. M. Mejia (Nueva York: Springer), 69–80.

Carrero, V., Soriano, R. M., and Trinidad, A. (2012). Teoría Fundamentada Grounded Theory. El Desarrollo de Teoría Desde la Generación Conceptual. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas CIS.

Castellví, J., Díez Bedmar, M.-C., and Santisteban, A. (2020). Pre-service teachers’ critical digital literacy skills and attitudes to address social problems. Soc. Sci. 9:134. doi: 10.3390/socsci9080134

Castellví, J., Massip, M., and Pagés, J. (2019). Emotions and critical thinking in the digital age: a study with beginning teachers. REIDICS 5, 23–41. doi: 10.17398/2531-0968.05.23

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. Univ. Chic. Legal Forum 140, 139–167. doi: 10.4324/9781003199113-14

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 43, 1241–1299. doi: 10.2307/1229039

Díez-Bedmar, M.-C. (2019). Educación histórica con perspectiva de género: resultados de aprendizaje y competencia docente. Futuro Pasado 10, 81–122. doi: 10.14516/fdp.2019.010.001.003

Díez-Bedmar, M.-C., and Fernández Valencia, A. (2019). Enseñanza de las ciencias sociales con perspectiva de género. Clío 45, 1–10.

Díez-Bedmar, M.-C., and Fernández Valencia, A. (2021). Perspectiva de género en las aulas de ciencias sociales. Reflexiones en torno a resistencias presentes. Íber 103, 43–50.

Díez-Bedmar, M.-C., and Ortega Sánchez, D. (2021). “Estado de la cuestión sobre la perspectiva de género y enseñanza de la historia y las ciencias sociales en España,” in O Ensino De História no Brasil e Espanha/La Enseñanza De la Historia en Brasil y España. Coord. A. Santisteban and C. A. Lima (Porto Alegre: Editora Fi), 234–254.

Elipe, P., Díez, M.-C., and De la Cruz, A. (2021). “Masculinidades a través de los ojos del alumnado y del profesorado,” in Coeducación y Masculinidades: Hacia la Construcción De Sociedades Cívicas y Democráticas. Coord. A. García (Barcelona: Octaedro), 33–80.

Giddens, A. (2000). “Etnicidad y raza,” in Sociología, ed. A. Giddens (Madrid: Alianza Editorial), 277–315.

Hill Collins, P. (2000). Black Feminist Thought. Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kerr, S., and Schmeichel, M. (2018). Teacher twitter chats: gender differences in participants’ contributions. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 50, 241–252. doi: 10.1080/15391523.2018.1458260

Maffía, D. (2007). Epistemología feminista: la subversión semiótica de las mujeres en la ciencia. Rev. Venez. Estud. Mujer 12, 63–98.

Ortega-Sánchez, D., Blanch, J. P., Quintana, J. I., Cal, E. S., and de la Fuente-Anuncibay, R. (2021). Hate speech, emotions, and gender identities: a study of social narratives on twitter with trainee teachers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:4055. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18084055

Ortuño Molina, J., and Fredrik, A. (2021). Concepciones de docentes en formación suecos y españoles sobre la desigualdad de género en perspectiva temporal. Panta Rei 15, 161–184. doi: 10.6018/pantarei.485481

Pace, J. (2019). Contained risk-taking: preparing preservice teachers to teach controversial issues in three countries. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 47, 228–260. doi: 10.1080/00933104.2019.1595240

Puleo García, A. (2005). El patriarcado ¿una organización social superada? Temas Para Debate 133, 39–42.

Seixas, P., and Morton, T. (2013). The Big Six: Historical Thinking Concepts. Toronto, ON: Nelson Education.

Strauss, A. y, and Corbin, J. (2002). Bases De la Investigación Cualitativa. Técnicas y Procedimientos Para Desarrollar la Teoría Fundamentada. Medellín: Editorial Universidad de Antioquia.

UNESCO (2015). A Guide for Gender Equality in Teacher Education. Policy and Practices. Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO (2019). Leading SDG 4 - Education 2030. Available online at: https://en.unesco.org/themes/education2030-sdg4

Keywords: historical thinking, learning outcomes, feminism theories, gender category, intersectionality, critical thinking, problematizing knowledge

Citation: Díez-Bedmar MdC (2022) Feminism, Intersectionality, and Gender Category: Essential Contributions for Historical Thinking Development. Front. Educ. 7:842580. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.842580

Received: 23 December 2021; Accepted: 25 January 2022;

Published: 10 March 2022.

Edited by:

Pilar Rivero, University of Zaragoza, SpainReviewed by:

Iñaki Navarro-Neri, University of Zaragoza, SpainMaria Feliu-Torruella, University of Barcelona, Spain

Copyright © 2022 Díez-Bedmar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: María del Consuelo Díez-Bedmar, bWNkaWV6QHVqYWVuLmVz

María del Consuelo Díez-Bedmar

María del Consuelo Díez-Bedmar