- Faculty of Hospitality and Tourism, Prince of Songkla University, Phuket, Thailand

The true power of social media lies in its ability to enable users to connect and share information with anyone around the globe. The use of social media in education helps students get more useful information and connect with learning groups and other educational systems that make education convenient. The purpose of this exploratory interview study is to identify how undergraduate students use social media to support their studies. Moreover, the study examines student perceptions concerning the benefits and limitations of using social media for educational purposes. The empirical data for this study was generated through a series of semi-structured interviews with undergraduate students (n = 27) and analyzed thematically. Three themes emerged through the thematic analysis: (1) perceived usage of social media, (2) invasion of privacy, and (3) the approachable teacher. The results of the study offer practical implications for educators and policymakers about incorporating social media in their curricula.

Introduction

The merger between social media and mobile devices allows students to create, edit, and share course content in textual, video, and audio forms. These technological innovations offer a new kind of learning culture, based on the principles of collective exploration and interaction (Greenhow and Lewin, 2016). Social media phenomena have their roots around the start of the millennium and originated in 2005 after Web 2.0 became a reality. Moreover, social media is defined more clearly as “a group of Internet-based applications that build on the ideological and technological foundation of Web 2.0 and allow creation and exchange of user-generated contents (Zgheib and Dabbagh, 2020). Mobile devices and social media provide students with opportunities to access resources, learning materials, and course content and to interact with tutors and peers (Greenhow and Lewin, 2016; Olagbaju and Popoola, 2020).

Anderson and Jiang (2018) report that 95% of teenagers have access to a mobile device; furthermore, 45% state that they are “constantly online.” However, there is a potential area for concern as identified by Stathopoulou et al. (2019), who state that students perceive a distinct divide between their learning space and their personal space. They argue that educators must address individual student preferences to combine or separate the two domains. Some studies argue that teachers play an important role in inspiring students to use social media to support their studies (Van Den Beemt et al., 2020), while others state that excessive instructional control may lead to boredom and lack of motivation (Barkley and Lepp, 2021).

Research Objective

Freberg and Kim (2018) report that students use social media to connect with classmates, work on assignments, and, to some extent, connect with faculty. Their quantitative findings could, however, be extended by gaining a more detailed understanding of how social media is used to support connecting with peers and teachers and working on assignments. Therefore, the explorative interview study aims to contribute by critically exploring how undergraduate students perceive using social media to support their studies and the perceived benefits and limitations compared with other means of communication. The study is guided by the objective of answering the following two research questions: “How do undergraduate students perceive the use of social media to support their studies?” and “What are the perceived benefits and limitations of using social media for educational purposes as compared with other means?” A series of semi-structured interviews will be used to gain a better understanding of the student perspective and students’ perceptions of using social media to support their studies.

Related Literature

Social Media in Education

Social media, in a wide sense, refers to any medium that aids in the integration of technology into people’s lives for the purpose of communication (Anderson and Jiang, 2018). Over the last decade, the use of social media has surged, as has the use of social media in higher education. To connect with and engage students, more universities are turning to social media platforms including social networking sites, wikis, and blogs (Appel et al., 2020). There is significant evidence that social media can be used to engage students both within and outside the classroom, resulting in improved academic achievement (Anderson and Jiang, 2018; Appel et al., 2020).

As the usage of social media continues to rise, the usage of social media in higher education is continually growing and evolving, with proponents tugging between its merits and demerits (Chugh and Ruhi, 2018). Studies have shown that social media play a central role in online education (Selwyn and Stirling, 2016; Appel et al., 2020). Ivala and Gachago (2012) identified the ways that social media has been used in classroom teaching, from replacing email to increasing access to online classroom interaction for “shy” students. Researchers also found that the use of social media tools can promote interaction between instructors and students, thus improving teaching quality in large online classes (Appel et al., 2020).

Mediated Communication

Mediated communication or mediated interaction refers to communication carried out by the use of information communication technology and can be contrasted with face-to-face communication (Li and Kent, 2021). While the technology used nowadays is frequently associated with computers, giving rise to the popular term computer-mediated communication, mediated technology does not have to be computerized; for example, writing a letter with a pen and paper is also mediated communication (Yao and Ling, 2020). Thus, mediated communication can be defined as the use of any technical medium for transmission across time and space (Boczkowski et al., 2018; Yao and Ling, 2020; Li and Kent, 2021).

Communication via Social Media

The rapid adoption of social media technologies has resulted in a fundamental shift in the way communication and collaboration take place (Greenhow and Lewin, 2016). Social network sites help fulfill communication needs and wants. It is a convenient method of communication and provides the ability to stay connected to friends and family, but at the users’ preferred rate and time (Chugh and Ruhi, 2018). Social media users can manage their interactions within their schedules by choosing when they want to read and respond. Internet communication is a self-contained activity usually carried out alone.

However, it is efficient because it is a one-to-many method of communication that allows users to quickly spread information. Social media fulfills different communication needs for different users (Sobaih et al., 2020). Interactions via the computer facilitate communication by allowing users to conveniently keep in touch with family and friends, learn about social events, and find out about the activities of other users (Duncan-Daston et al., 2013). The gratification the results from this social information helped users feel that they were part of a peer network in terms of knowing what was going on about events and activities (Chugh and Ruhi, 2018).

Further, “social grooming” was an aspect of social networking that received attention in a comparison of users and non-users of social media sites. Social grooming included expressive activities of social interaction, communication, gossip, and entertainment. Users have expressed enjoyment from keeping track of their friends’ lives and activities, though non-users were less interested in these activities (Duncan-Daston et al., 2013).

Social Media During COVID-19

There is a growing academic body of literature on social media usage for different purposes in higher education, e.g., supporting the learning process, student support, and engagement, scholarly communication, and building connections (Sobaih et al., 2020). Notwithstanding, studies focused on social media as a supplement to formal online LMS or face-to-face learning. Guidelines, protocols, and standardized operating procedures, usually kept within institutions, have been shared at an unprecedented rate during the pandemic, with social media used as an effective vehicle. Messaging and conferencing platforms such as Zoom, Skype, WhatsApp, etc. are complemented by free and simple-to-use collaboration software such as Google Drive, Dropbox, and Slack (Dutta, 2020; Wong et al., 2021).

Methodology

The proposed study is an emerging topic; therefore, an exploratory study is a suitable frame (De Langhe and Schliesser, 2017). Exploratory research initially employs a broad perspective and, as it progresses, the results crystallize (Stebbins, 2001). Previous research has been conducted mainly using quantitative data; therefore, qualitative data can offer a more detailed and nuanced understanding (Flick, 2018). The proposed study is being conducted from the perspective of students, who must decide what is social media and what is not, as well as what is “educational” and what is “personal.” Thus, the study does not provide a formal definition before the interviews, as students’ view on these terms is one of the contributions of the study.

Data Collection

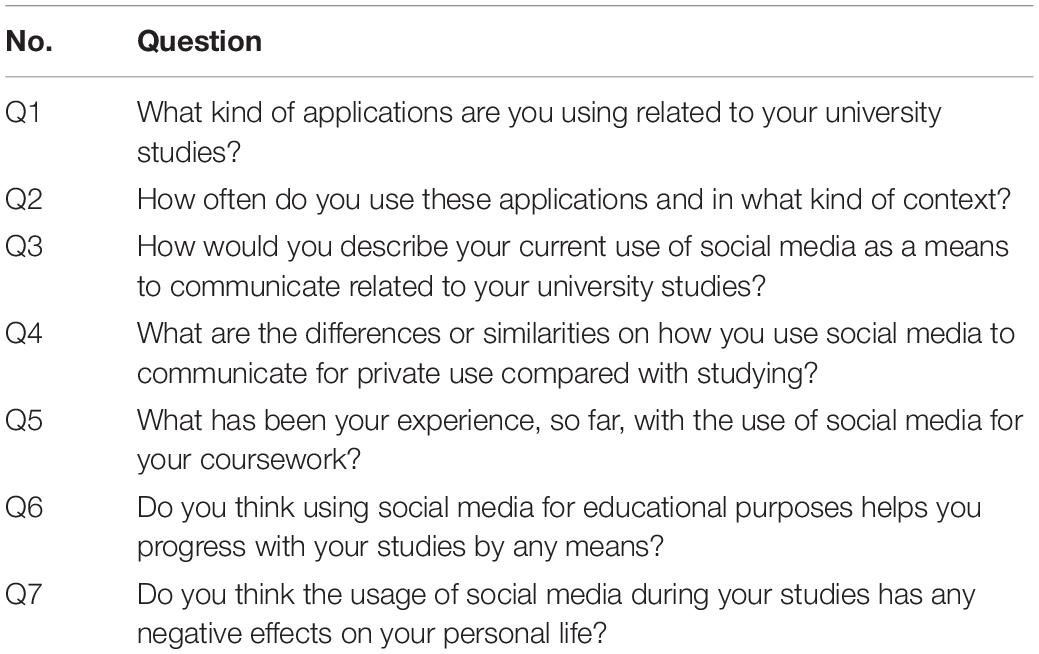

The data was collected through twenty-seven (27) semi-structured interviews with full-time undergraduate students at the Prince of Songkla University in Phuket, Thailand. The participants were arbitrarily selected to participate in the study and an appointment for the in-person interview was agreed upon by approaching the students individually. The data collection was carried out over 6 weeks between December 2021 and January 2022 at the Prince of Songkla University in Phuket, Thailand. A set of seven questions was used to guide the semi-structured interview (Table 1). Examples of these questions are “What has been your experience, so far, with the use of social media for your coursework?” and “What are the differences or similarities on how you use social media to communicate for private use compared with studying?” Each question had a set of three to four prompt questions to gain a more insightful understanding of the participants’ perceptions.

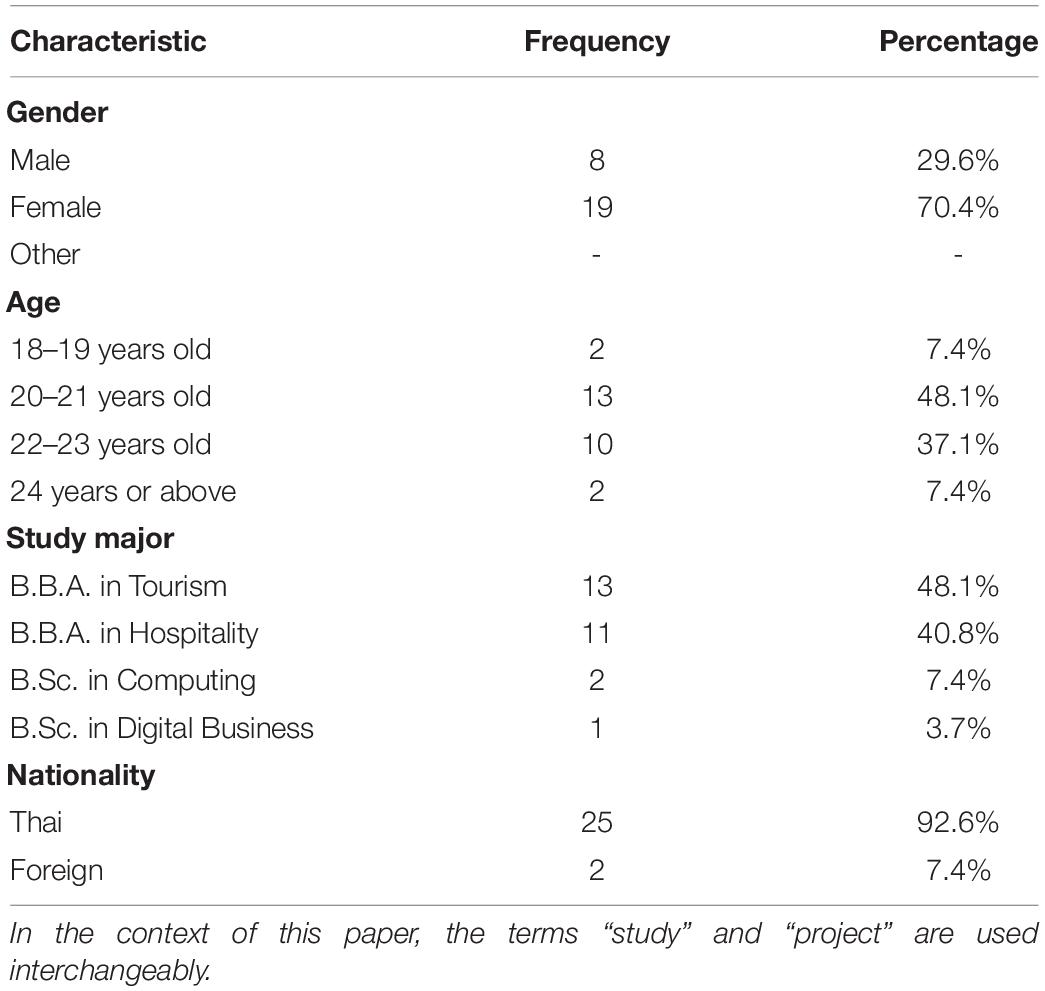

To protect the identities of the participants, the interviews took place off-premises in a nearby coffee shop. The length of the interviews ranged from 20 min to 1 h 8 min with an average duration of 28 min. Out of the 27 participants, 19 participants were female (70%), which is a reasonable representation of the actual student demographics at the university. Because the students were studying toward an undergraduate degree, their ages ranged from 18 to 24 years with an average age of 21.3 years. Furthermore, 13 students were majoring in Tourism (48.1%), followed by Hospitality (n = 9; 40.8%), computing (n = 2; 7.4%), and digital business (n = 1; 3.7%). Lastly, the majority of students were Thai nationals (n = 25; 92.6%) with the remainder being foreign degree students (Table 2).

Data Analysis

The method of inquiry through semi-structured interviews suggested a thematic analysis of the collected data (Neuendorf, 2018). During the interview, a series of open-ended questions, aimed at gaining more comprehensive insight into the participants’ perspectives, was asked. With the consent of the participants, the interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and categorized according to the questions posed to the participants. Moreover, the transcripts were used only for purposes of the thematic analysis and did not reveal the identity of the participants. The thematic analysis was developed based on the gathered data from the interviews to create groups and patterns. Moreover, in the analysis process, keywords were developed into codes. The codes formed the basis for bundling and grouping the data by clusters and analyzing the information thematically (Terry et al., 2017). This process was repeated until both researchers agreed on the results. Finally, conclusions were drawn based on the identified categories and patterns found for each category of social media use. The findings are presented in the subsequent sections of this report.

Ethics and Confidentiality

The interview participants were presented with the specific aim and scope of the research, and written consent was obtained before the interviews were conducted. The consent form was developed following the policies of the Ethical Advisory Board in South East Sweden (2021). The students were told that they could withdraw from participation at any time as well as have their collected data removed from the study. Moreover, it was made clear to the interviewees that their participation in the study had no bearing on their academic performance. Furthermore, confidentiality was extended to all 27 participants, whose identities were known only by the researchers involved.

Results and Discussion

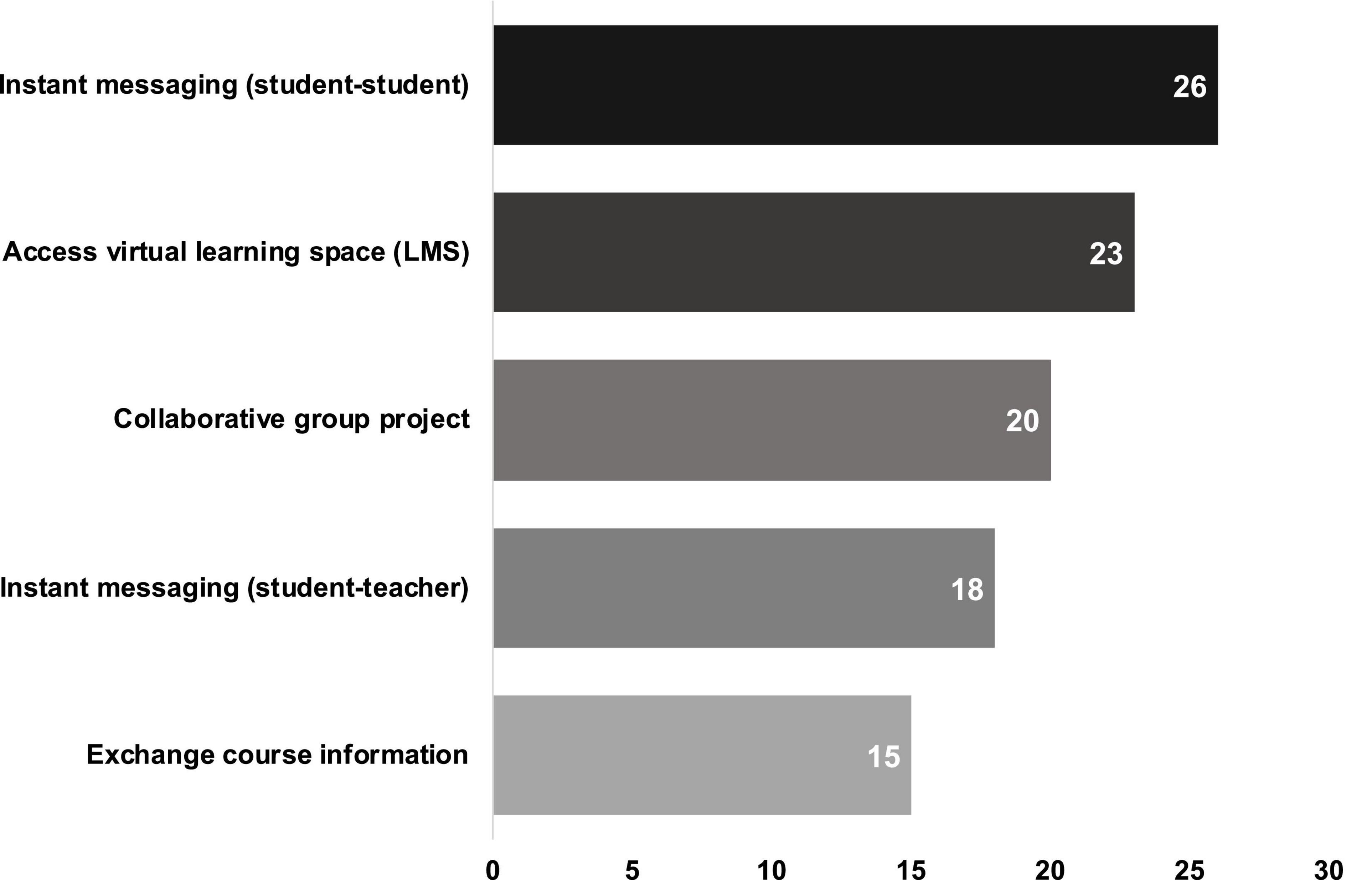

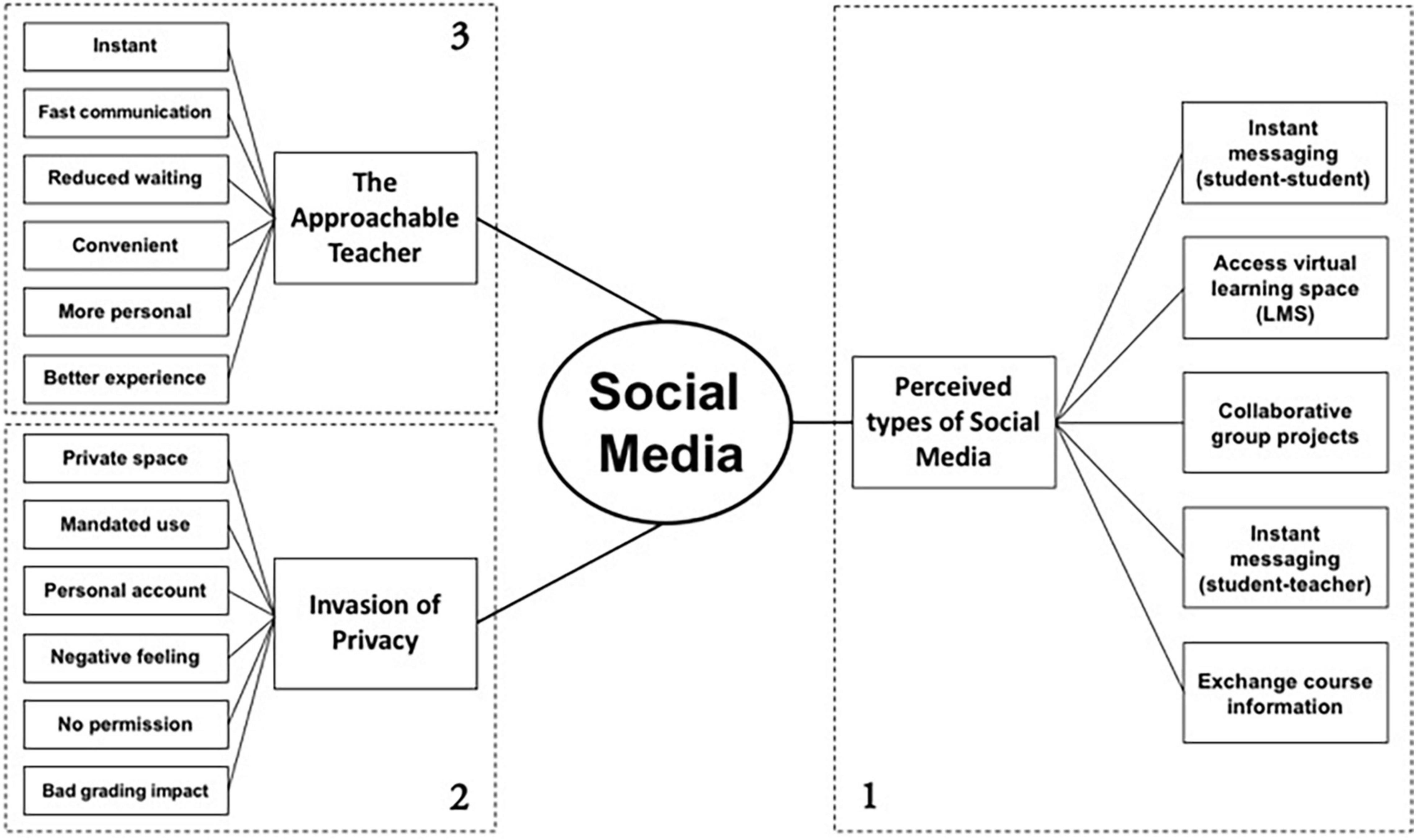

During the analysis of the interview data, three noteworthy themes emerged, which will be discussed in this section. These three themes were: (1) perceived usage of social media, (2) invasion of privacy, and (3) the approachable teacher. Furthermore, the themes emerged as part of the data analysis process when the keywords were organized and bundled into codes as the basis for the themes shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Visualization of the emerged themes and their respective coding (based on empirical data).

Perceived Usage of Social Media

All of the participants reported that they engaged in the use of social media at least once per day. However, half of the students reported that it is sometimes difficult to clearly distinguish between personal use and educational use, as the spheres often intertwine. Based on the responses collected from the participants, the five most commonly reported types of usage are discussed in this section.

Instant Messaging (Student-Student)

The students reported a notable difference between instant messaging with their peers (i.e., student-to-student) and their lecturer (i.e., student-teacher). Consequently, the results are reported separately and the type “instant messaging” appears twice in the overview (Figure 2). The vast majority of students (n = 26) reported that their most frequent use of social media relates to instant messaging among their peers. However, about half of the respondents (n = 12) also reported that, often, personal use and educational use are interconnected. An example of this finding is the following comment made by an interview participant: “I ask [my peer] a question about studying, but then we chat about something else” (P7).

Access Virtual Learning Space (Learning Management System)

Accessing the learning space or learning management system (LMS) was the second most common type of social media usage reported by the respondents (n = 23). Though there is no common agreement in the literature regarding whether a learning management system should be considered social media (Mpungose, 2020), the vast majority of students perceive their LMS as a type of social media. This interpretation could stem from the fact that students access their LMS in a similar manner as other applications on their mobile devices or laptops without having a clear boundary of what is considered educational and personal space. In particular, during the COVID-19 pandemic, when entire curricula transitioned to e-learning, the ease of accessing the learning management system contributed to students’ perceived satisfaction with the course (Fuchs and Karrila, 2021).

Collaborative Group Projects

Collaboration with peers on a semester project, case study, or joint presentation was reported as the third most common type of usage for social media (n = 20) in support of the students’ studies. The collaborative learning approach is said to foster the development of competencies and critical thinking skills in learners (Zhang et al., 2018). However, many students who cited collaborative group projects as an example of how they use social media during their studies also stated that collaboration via social media is only the second-best option, inferior to physical meetings. Many students shared the following sentiment: “I would [say] it is not the best way to collaborate, but it is the best alternative with technology during COVID” (P5). This response mostly emerged as all students attended their classes virtually due to the ongoing Coronavirus pandemic.

Instant Messaging (Student-Teacher)

Similarly, the first category, instant messaging, allows students to easily ask questions and resolve uncertainty. However, only two-thirds of the interview participants (n = 18) reported that instant messaging with their lecturer is a way they use social media for educational purposes. While two-thirds of students reported this type of usage, they also said that they experience an underlying feeling of uncomfortableness when they instant message their lecturers. A possible explanation is offered by an interview participant who noted that “normally there is a high-power distance with our teachers, but if we text on social with them, it just does not feel right to me” (P14).

Exchange Course Information

Exchanging course-related information was reported as the fifth most common type of use of social media by the students (n = 15). The respondents agreed that it is the easiest way to share “personal lecture notes” or “discuss and clarify the requirements for course assignments or homework.” A representative comment made during the interviews is that “it is easy to ask for the information from the lecture via social media, especially if I missed the class or did not pay attention [to what the teacher said]” (P18). Similarly, Osatuyi (2013) reported that “social interaction is experiencing a new dynamic with the advent of social media technologies” and the exchange of course-related information has been one of the most common types of usage for education (p. 2624).

It is clear that social media is here to stay and that students are using social media applications to communicate with peers and instructors, gather and exchange information, access their virtual learning space, and collaborate on group projects. As a result of this, and the absence of research investigating the current inclusion of social media in the course curriculum, many educators are managing the inclusion based on instinct rather than evidence-based best practices (Vie, 2015; Mpungose, 2020). The current body of knowledge offers a wide range of evidence supporting, in the classroom, the usage of different types of social media applications, i.e., Facebook (Manca and Ranieri, 2016; Peruta and Shields, 2017), Twitter (Nagle, 2018), and Instagram (Thomas et al., 2018). However, the contribution of this study is that it lets students decide how they perceive the different types of social media usage to support their studies. As previously reported, social media fulfills different communication needs for different users (Sobaih et al., 2020). However, students use social media for various activities to support their studies, which transcends the traditional use of social media merely for communication purposes.

Invasion of Privacy

Social media is used principally by students in the private sphere. However, its implementation for educational purposes in higher education is rapidly expanding. In the context of this study, the students reported that, for the majority of their courses, the lecturer asked them to join “at least one social media platform to ease communication barriers” (n = 17) and “facilitate an effective communication channel” (n = 22). More in-depth questions were posed given that, when asked about possible limitations or drawbacks of using mandated social media for their coursework, a majority of interviewees reported privacy concerns. Many students said that they registered for various social media platforms for private purposes; hence, the arrangement of content shared on their social medial reflects an audience of closer friends and relatives.

The respondents felt that sharing their social media with the course instructor was an invasion of privacy (n = 16). Some considered removing personal content from their social media feed to facilitate a “clean feed” appropriate for educational purposes, while others considered registering a second account purely for educational coursework. The students’ primary concern with sharing their social media was the loss of control over who could see their personal content and who could not. Furthermore, some students reported that they did not feel comfortable raising the issue with their course instructor, as they feared a negative impact on their course grading.

Though previous literature states that privacy concerns were not reported as being a major issue in similar studies (Sterling et al., 2017; Yerby et al., 2019), further consideration is required concerning this notable finding that students feel uncomfortable sharing their social media in some cases. The following comments were made by the interviewees and are representative of many of the respondents who expressed their views. Students commented that “I want to be the one that decides whom I want to accept as a follower on my social media” (P24) and “after all it is a very private matter. Using my private social media for university makes me consider many times what is appropriate [or not] to post on my private account” (P14).

The Approachable Teacher

Another notable theme that emerged in the analysis process was “the approachable teacher,” summarizing students’ experiences and comments that expressed their appreciation for a swift communication channel with their course instructor (n = 21). Though only 18 out 27 students identified instant messaging with their teacher as a type of usage (Figure 2), notably, 21 students stated their gratitude for having an instant communication channel with their teacher as opposed to contact via telephone, email, or in-person. Further clarification must be provided about the finding that 18 students reported using instant messaging with their teacher as a means of swift communication, while 21 reported gratitude for having a direct communication channel. The 18 reports refer to two-way communication wherein the student can ask questions, whereas the 21 reports refer to one-way communication wherein the students receive course-related updates from their teacher.

Another noteworthy finding is a correlation between students “appreciating a direct communication channel with their course instructor” (n = 21) and students “raising concern about privacy issues to share their social media for course-related purposes” (n = 16). Almost all the participating students who raised concerns about their privacy or felt that their privacy was invaded also expressed their appreciation for a direct communication channel with their course instructor. This surprising finding indicates that students want a direct communication channel to eliminate communication barriers while also staying in control of whom to accept on their social media.

Limitations and Future Work

Limitations offer an opportunity for future research. There are four particular limitations that the reader should consider when evaluating the results of this paper. All interviews were conducted in English; however, none of the participants (or the principal investigator) were native English speakers. Therefore, the students might have had difficulties expressing their precise sentiments in response to a particular question. Furthermore, the interviews were conducted at a time when students mostly studied remotely due to the ongoing pandemic at the time. These circumstances might have affected their perceived usefulness and frequency of use with regard to social media. Lastly, the participants were degree students at a large university in Thailand; henceforth, the results should be seen and interpreted in the cultural context of Thai culture, which differs substantially from many Western cultures.

Conclusion

This research project aimed to investigate how undergraduate students perceive the use of social media to support their studies. Moreover, it sought to identify the perceived benefits and limitations of using social media for educational purposes. With regard to summarizing the findings, it can be noted that students are frequent users of social media to facilitate their studies. Moreover, students have different interpretations of the diverse types of usage, i.e., instant messaging with their peers or teacher, exchange of information, access to their virtual learning space, or collaborative group projects. Moreover, a possible solution for educators to limit the perceived impact on the invasion of privacy could be an open dialogue during the course introduction and suggesting a secondary account for educational purposes only. Lastly, the study revealed that there are two types of students: those who feel that the use of social media intrudes on their privacy and personal space and those who appreciate the opportunity to engage in quick and easy communication with their teachers. The findings of this study are useful for educators and policymakers in terms of considering students’ needs as well as concerns before mandating that they use social media as part of their coursework.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Faculty of Hospitality and Tourism, Prince of Songkla University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

KF planned, executed the study, organized, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

The Faculty of Hospitality and Tourism, Prince of Songkla University supported this research project under the Fast Track Data Collection Grant (Contract No. FHT6400011).

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants who shared their experiences in the semi-structured interviews.

References

Anderson, M., and Jiang, J. (2018). Teens, social media & technology 2018. Pew Res. Center 31, 1673–1689.

Appel, G., Grewal, L., Hadi, R., and Stephen, A. T. (2020). The future of social media in marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 48, 79–95. doi: 10.1007/s11747-019-00695-1

Barkley, J. E., and Lepp, A. (2021). The effects of smartphone facilitated social media use, treadmill walking, and schoolwork on boredom in college students: results of a within subjects, controlled experiment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 114:106555. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106555

Boczkowski, P. J., Matassi, M., and Mitchelstein, E. (2018). How young users deal with multiple platforms: the role of meaning-making in social media repertoires. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 23, 245–259. doi: 10.1093/jcmc/zmy012

Chugh, R., and Ruhi, U. (2018). Social media in higher education: a literature review of Facebook. Educ. Inf. Technol. 23, 605–616. doi: 10.1007/s10639-017-9621-2

De Langhe, R., and Schliesser, E. (2017). Evaluating philosophy as exploratory research. Metaphilosophy 48, 227–244. doi: 10.1111/meta.12244

Duncan-Daston, R., Hunter-Sloan, M., and Fullmer, E. (2013). Considering the ethical implications of social media in social work education. Ethics Inf. Technol. 15, 35–43. doi: 10.1007/s10676-013-9312-7

Dutta, A. (2020). Impact of digital social media on Indian higher education: alternative approaches of online learning during Covid-19 pandemic crisis. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 10, 604–611. doi: 10.29322/IJSRP.10.05.2020.p10169

Ethical Advisory Board in South East Sweden (2021). Advice and Ethical Assessment of Projects. Available online at: https://lnu.se/en/meet-linnaeus-university/collaborate-with-us/projects-and-networks/ethical-advisory-board-in-south-east/ (accessed December 7, 2021).

Freberg, K., and Kim, C. M. (2018). Social media education: industry leader recommendations for curriculum and faculty competencies. J. Mass Commun. Educ. 73, 379–391. doi: 10.1177/1077695817725414

Fuchs, K., and Karrila, S. (2021). The perceived satisfaction with emergency remote teaching (ERT) amidst COVID-19: an exploratory case study in higher education. Educ. Sci. J. 23, 116–130. doi: 10.17853/1994-5639-2021-5-116-130

Greenhow, C., and Lewin, C. (2016). Social media and education: reconceptualizing the boundaries of formal and informal learning. Learn. Media Technol. 41, 6–30. doi: 10.1080/17439884.2015.1064954

Ivala, E., and Gachago, D. (2012). Social media for enhancing student engagement: the use of Facebook and blogs at a University of Technology. South Afr. J. High. Educ. 26, 152–167.

Li, C., and Kent, M. L. (2021). Explorations on mediated communication and beyond: toward a theory of social media. Public Relat. Rev. 47:102112. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2021.102112

Manca, S., and Ranieri, M. (2016). Facebook and the others. Potentials and obstacles of social media for teaching in higher education. Comput. Educ. 95, 216–230. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2016.01.012

Mpungose, C. B. (2020). Are social media sites a platform for formal or informal learning? Students’ experiences in institutions of higher education. Int. J. High. Educ. 9, 300–311. doi: 10.5430/ijhe.v9n5p300

Nagle, J. (2018). Twitter, cyber-violence, and the need for a critical social media literacy in teacher education: a review of the literature. Teach. Teach. Educ. 76, 86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2018.08.014

Neuendorf, K. A. (2018). “Content analysis and thematic analysis,” in Advanced Research Methods for Applied Psychology, ed. P. Brough (New York, NY: Routledge), 211–223. doi: 10.4324/9781315517971-21

Olagbaju, O. O., and Popoola, A. G. (2020). Effects of audio-visual social media resources-supported instruction on learning outcomes in reading. Int. J. Technol. Educ. 3, 92–104. doi: 10.46328/ijte.v3i2.26

Osatuyi, B. (2013). Information sharing on social media sites. Comput. Hum. Behav. 29, 2622–2631. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.001

Peruta, A., and Shields, A. B. (2017). Social media in higher education: understanding how colleges and universities use Facebook. J. Mark. High. Educ. 27, 131–143. doi: 10.1080/08841241.2016.1212451

Selwyn, N., and Stirling, E. (2016). Social media and education…now the dust has settled. Learn. Media Technol. 41, 1–5. doi: 10.1080/17439884.2015.1115769

Sobaih, A. E. E., Hasanein, A. M., and Abu Elnasr, A. E. (2020). Responses to COVID-19 in higher education: social media usage for sustaining formal academic communication in developing countries. Sustainability 12:6520. doi: 10.3390/su12166520

Stathopoulou, A., Siamagka, N. T., and Christodoulides, G. (2019). A multi-stakeholder view of social media as a supporting tool in higher education: an educator–student perspective. Eur. Manag. J. 37, 421–431. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2019.01.008

Stebbins, R. A. (2001). Exploratory Research in the Social Sciences, Vol. 48. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Sterling, M., Leung, P., Wright, D., and Bishop, T. F. (2017). The use of social media in graduate medical education: a systematic review. Acad. Med. 92:1043. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001617

Terry, G., Hayfield, N., Clarke, V., and Braun, V. (2017). “Thematic analysis,” in The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2nd Edn, eds C. Willig and W. Stainton Rogers (London: SAGE Publications), 17–37.

Thomas, R. B., Johnson, P. T., and Fishman, E. K. (2018). Social media for global education: pearls and pitfalls of using Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 15, 1513–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2018.01.039

Van Den Beemt, A., Thurlings, M., and Willems, M. (2020). Towards an understanding of social media use in the classroom: a literature review. Technol. Pedagogy Educ. 29, 35–55. doi: 10.1080/1475939X.2019.1695657

Vie, S. (2015). What’s going on?: challenges and opportunities for social media use in the writing classroom. J. Fac. Dev. 29, 33–44.

Wong, A., Ho, S., Olusanya, O., Antonini, M. V., and Lyness, D. (2021). The use of social media and online communications in times of pandemic COVID-19. J. Intensive Care Soc. 22, 255–260. doi: 10.1177/1751143720966280

Yao, M. Z., and Ling, R. (2020). “What is computer-mediated communication?”—an introduction to the special issue. J. Comput. Med. Commun. 25, 4–8. doi: 10.1093/jcmc/zmz027

Yerby, J., Koohang, A., and Paliszkiewicz, J. (2019). Social media privacy concerns and risk beliefs. Online J. Appl. Knowl. Manag. 7, 1–13. doi: 10.36965/OJAKM.2019.7(1)1-13

Zgheib, G. E., and Dabbagh, N. (2020). Social media learning activities (SMLA): implications for design. Online Learn. 24, 50–66. doi: 10.24059/olj.v24i1.1967

Keywords: social media, mediated communication, higher education, remote teaching, undergraduate

Citation: Fuchs K (2022) An Exploratory Interview Study About Student Perceptions of Using Social Media to Facilitate Their Undergraduate Studies. Front. Educ. 7:834391. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.834391

Received: 13 December 2021; Accepted: 09 February 2022;

Published: 08 March 2022.

Edited by:

Maria J. Hernandez-Serrano, University of Salamanca, SpainReviewed by:

Rania Zaini, Umm Al-Qura University, Saudi ArabiaRosalynn Argelia Campos Ortuño, University of Salamanca, Spain

Copyright © 2022 Fuchs. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kevin Fuchs, YWoua2V2aW4uZmh0QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Kevin Fuchs

Kevin Fuchs