- 1Department of Psychology, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

- 2Open University of Athens, Athens, Greece

Within a modern school that follows the international rules of inclusive education is very important for teachers to be able to understand and meet the needs of children with Developmental Language Disorder (DLD). The present study explores for the first time in Greece, the views of 122 Greek Kindergarten Teachers (KTs) and Primary school teachers (PSTs) about DLD, through an online survey that elaborated both categorical and Likert scale responses. According to the results half of the participants were not familiar with the term. Both groups of professionals reported that children with DLD have many vocabulary and syntactic difficulties in the receptive language. In the expressive language KTs identified more articulation and phonological difficulties, while PSTs referred mainly vocabulary and grammatical difficulties. The majority of professionals mentioned additional difficulties such as emotional and behavioral problems. Both groups identified a variety of challenges while working with children with DLD. KTs focused mostly on children’s emotional difficulties, while PSTs reported mostly their learning difficulties. The participants also recognized their own limitations regarding background knowledge and the need for further training. Furthermore, the educators mentioned that it is difficult for them to identify and support a child with DLD while, at the same time they acknowledged the need to collaborate with other professionals in order to meet children’s needs. The results are discussed in terms of their importance for raising awareness for DLD as well as for teachers’ better training, in order to efficiently identify and support children with DLD.

Introduction

Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder which is characterized by difficulties in oral language in the absence of other disorders or substantial hearing loss (Bishop et al., 2017). The term DLD—previously known as “Specific Language Impairment” (SLI)—was suggested by two CATALISE projects (Bishop et al., 2016; Bishop, 2017) in order to provide those working with children with DLD an inclusive language definition approach and framework. Recently, there is an international growing interest in the study of DLD, and its long-term effects on children and adolescents (Bishop et al., 2017). However, the majority of the evidence-based research to date, derives from English speaking countries, and there is rather limited research deriving from other countries, including Greece (Okalidou and Kampanaros, 2001). Additionally, although DLD affects a substantial number of children, 7.5% at school entry age (Norbury et al., 2016), public awareness is still rather limited when compared to other neurodevelopmental disorders, including Autism Spectrum Disorder, Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder and Dyslexia (Conti-Ramsden et al., 2013; Bishop, 2017; Thordardottir and Topbaş, 2021). In this direction, examining teachers’ views on DLD is very important since this disorder may impact on various aspects of children’s development including learning in the classroom (Dockrell and Lindsay, 2001; Bishop et al., 2017; Dockrell et al., 2017), as well as social and emotional competence (Botting and Conti-Ramsden, 2000; Van Daal et al., 2007; Lindsay et al., 2010; McCormack et al., 2011; Wadman et al., 2011; Bakopoulou and Dockrell, 2016; Toseeb and St Clair, 2020; Ralli et al., 2021b). To our knowledge, no attempt has been made till today to examine systematically the views of KTs and PSTs on DLD in Greece.

Children with DLD as it is known from the relevant literature, face receptive and expressive difficulties in grammatical morphemes and complex syntactic constructions (Okalidou and Kampanaros, 2001; Rice, 2013). Difficulties with learning morphosyntactic and morphological rules constitute a clinical marker of the disorder (Lammertink et al., 2020). They also often experience severe deficits in vocabulary in comparison to their typically developing peers (McGregor et al., 2013). Most of the time, DLD goes unnoticed, however, could affect the development of literacy skills (Simkin and Conti-Ramsden, 2006; Palikara et al., 2011) and academic attainments (Conti-Ramsden et al., 2009; Dockrell et al., 2009, 2011) as “almost every educational skill presupposes the use of language” (Dockrell and Lindsay, 1998, p. 117). In two recent studies with Greek speaking primary school children, it was found that children with DLD had worse performance across a series of oral language skills (oral language comprehension, vocabulary knowledge, phonological and morphological awareness, pragmatics and narrative speech) as well as in written text production (Ralli et al., 2021a,b) in comparison to their typically developing peers.

In addition, children with DLD often face difficulties with their socialization throughout the school years (McCormack et al., 2011; Bakopoulou and Dockrell, 2016), exhibit behavior problems (Botting and Conti-Ramsden, 2000; Van Daal et al., 2007; Lindsay et al., 2010; Bakopoulou and Dockrell, 2016) and may become victims of bullying (van den Bedem et al., 2018). These children may often respond inappropriately in social situations and interact with peers less frequently than their typically developing counterparts (Toseeb and St Clair, 2020). In a recent study, with Greek-speaking primary school children with DLD it was demonstrated that they exhibited difficulties in social, school and emotional competence in comparison to their typically developing counterparts (Ralli et al., 2021b). Furthermore, research shows that this group of children continue to experience social difficulties during young adulthood reporting more social stress (Wadman et al., 2011).

Taking into account the current educational context and the special educational needs legislation, children with DLD attend mainstream schools internationally (McLeod and McKinnon, 2007; Dockrell et al., 2014) as well in Greece (L4547/2018). Also, most of the time, parents rely on teachers in order to become aware of their child’s language problems. For example, parents often ask the classroom teacher to confirm their suspicions of a speech problem (McAllister et al., 2011). Educators are the key persons for early identification and support of children with DLD in the mainstream classroom (Dockrell and Lindsay, 2001; Dockrell et al., 2017) and the same applies for the Greek educational system (L 3699/2008; L4186/2013; L4452/2017; L4547/2018). Teachers have the opportunity to observe children in their academic and non-academic daily activities, and therefore can possibly recognize those who struggle with language. In addition, O’Toole and Kirkpatrick (2007), reported that teachers with adequate knowledge in relation to DLD can better understand typical language development and identify children with language problems Their involvement in the identification of the children whose language characteristics place them at risk is essential (Gregory and Oetting, 2018). Therefore, mapping the teachers’ views on DLD is very important for understanding their needs to better support this group of children in the mainstream classrooms.

Research evidence about teachers’ views on language difficulties, which mainly comes from English-speaking countries, shows that children with DLD may impose a challenge for their teachers in the classroom (Dockrell and Lindsay, 2001; Marshall et al., 2002; Mroz and Hall, 2003; Marshall and Lewis, 2014; Dockrell and Howell, 2015; Dockrell et al., 2017; Bruce and Hansson, 2019). Previous studies in the United Kingdom have also reported teachers’ concerns about their knowledge of language difficulties (Marshall et al., 2010). Furthermore, it has been found that teachers’ understanding of the children’s specific problems is limited and inconsistent (Dockrell and Lindsay, 2001; Marshall and Lewis, 2014; Dockrell and Howell, 2015). Gallagher et al. (2019) in their systematic review about professionals perspectives and practices concerning children with DLD demonstrated that in the education literature DLD is usually referred more broadly as a “learning disability” or a “special educational need” and is classified along with other unexplained problems such as difficulties in developing literacy or numeracy skills. According to the authors this conceptualization of DLD focuses on the environment in which a child functions (e.g., the classroom) and how this may influence a child’s ability to learn.

Recently Christopulos and Kean (2020) examined the positive predictive value of teachers for language impairment identification. They found that teachers had difficulty in identifying children with language impairment. In parallel, research shows that teachers are able to identify possible curriculum and psychosocial difficulties of children with DLD (Dockrell and Howell, 2015) and are aware of children’s emotional difficulties (Dockrell et al., 2017). On the other hand, Girolamo (2017), in United States demonstrated that teachers may not always have enough knowledge of language to accurately identify the impact of DLD on children’s emotional, behavioral, educational life and the ability to determine possible areas for improvement.

Regarding the professional adequacy of educators, in terms of training, identification, support of children with DLD and collaboration with others, it seems that teachers have received limited training in identifying and providing support for children with DLD, as well as poor post-qualification training (Dockrell and Lindsay, 2001; Dockrell and Howell, 2015). Teachers also recognized their own limitations and lack of skills to meet children’s needs, suggesting further training (Dockrell and Lindsay, 2001; Mroz and Hall, 2003; Dockrell and Howell, 2015; Dockrell et al., 2017) as well as more tools for screening and identification in the mainstream classroom (Dockrell et al.’s (2017)).

Last, but not least, it is well known from the educational policy perspective, that inter-professional collaboration (IPC) has been recommended as a means for catering of children’s needs with additional difficulties, such as children with DLD, in the context of school (United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], 1994; World Health Organization [WHO], 2010). Relevant studies have shown that teachers acknowledge the importance of collaborating with other professionals to meet the needs of children with DLD (Wright and Kersner, 1999; Dockrell and Lindsay, 2001) and at the same time they recognize the challenges they may experience in doing so (Wright and Kersner, 2004). A collaborative approach among specialists to respond to children’s needs in the classroom may provide opportunities for improvement for all the professionals (Throneburg et al., 2000) but especially for the children and their families. For example, teachers may have the opportunity to observe the strategies being used by speech and language therapists. On the other hand, speech and language therapists by observing teachers may gain a better understanding of the skills a child needs to succeed in the classroom (Nippold, 2011).

Little is known about how teachers, outside English-speaking countries, conceptualize DLD and what challenges they experience in meeting children’s needs in their classrooms. In Greece there seems to be limited public awareness about DLD (Palikara and Ralli, 2013, 2017). In a small-scale study it was found that most of the Greek preschool teachers recognized their incomplete knowledge on issues of language disorders (Tzakosta and Stavrianidou, 2014). Furthermore, Georgali (2017) in her thesis showed that Greek primary school teachers reported that children generally face difficulties with morphology and syntax, both in oral and written language.

Mapping the views of both groups of professionals (KTs and PSTs) working with children who are at a critical age for exhibiting DLD, will allow for better comparisons between these two groups of participants, in terms of their understanding as well as their needs. To achieve this objective, the present study explores the views of different educational professionals’ (Kindergarten Teachers with Primary School Teachers) on DLD by: (a) mapping their understanding of DLD (knowledge of the term DLD, language and additional needs of the children with DLD); and (b) identifying their challenges and professional adequacy regarding training, identification and support of children with DLD as well as collaboration with others.

Based on the previous literature it was anticipated that teaching staff may not be very familiar with the term DLD, but on the other hand it was expected to be aware of children’s language and psychosocial difficulties (Dockrell and Lindsay, 2001; Dockrell and Howell, 2015; Wilson et al., 2016; Dockrell et al., 2017). It was also predicted that educators may face many challenges when working with children with DLD and feel inadequate regarding their training as well identification and support of this group of children (Dockrell and Howell, 2015; Dockrell et al., 2017). On the other hand, we expected educators to be willing to collaborate with other specialists (Hartas, 2004; Dockrell et al., 2017).

Materials and Methods

Participants

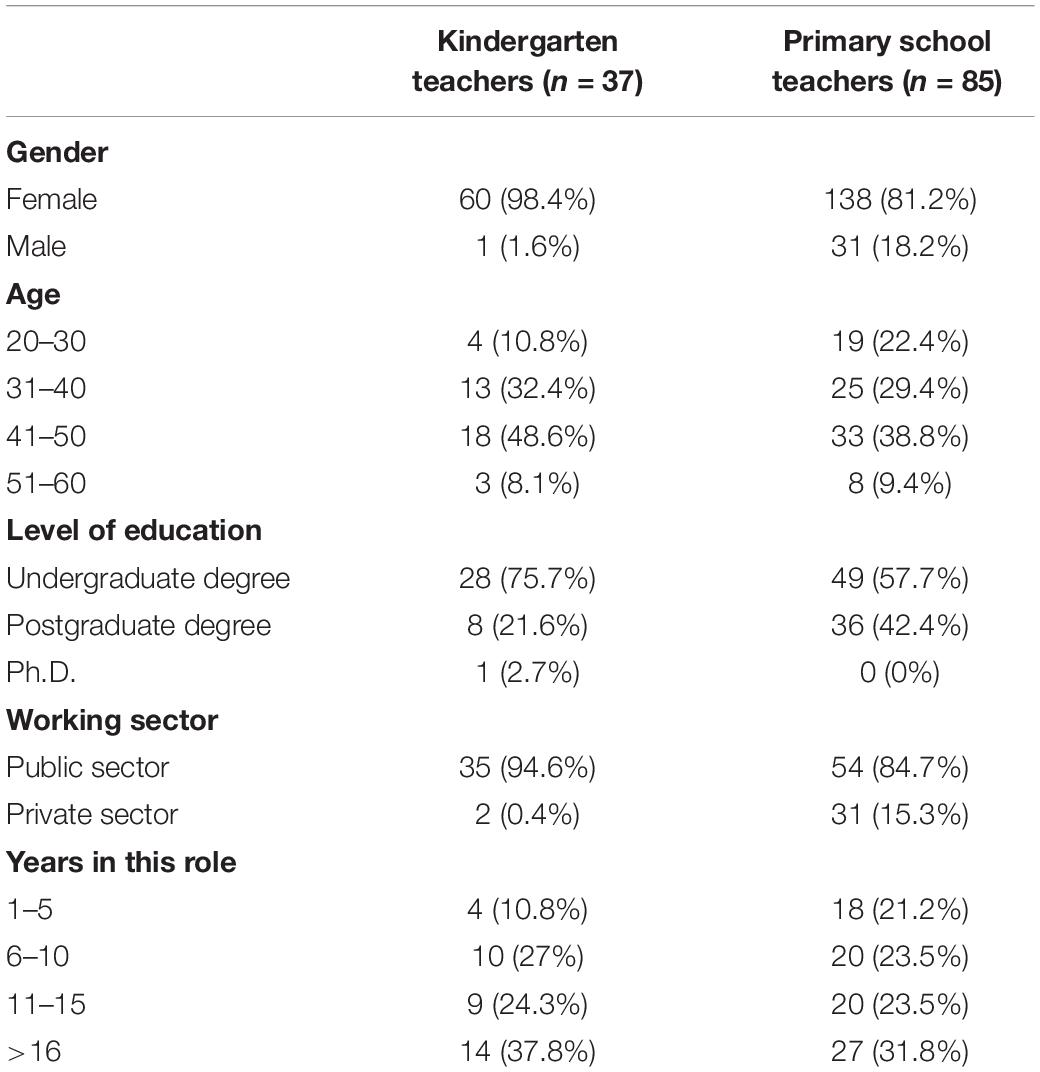

Two hundred and thirty-two teachers took part in the present survey. A considerable number of the respondents omitted sections and were therefore removed from the sample. Following that, 122 educators from different schools in Greece participated in the study (KTs n = 37; PSTs n = 85). The vast majority of both KTs (94.6%) and PSTs (84.7%) were working in the public education sector. Respondents were experienced practitioners as over 89% of the KTs and 78% of the PSTs had worked in their role for more than 5 years. Further details for the sample are reported in Table 1.

Materials

Participants responded to an online survey which was based on previous relevant studies (Dockrell and Lindsay, 2001; Dockrell and Howell, 2015; Dockrell et al., 2015, Dockrell et al., 2017), the Greek curriculum and educational system. This researcher—based survey was part of a wider project, which aimed to raise awareness about DLD in Greece. The questionnaire was first piloted with a small group of 35 participants- who did not take part in the main study- (15 KTs and 20 PSTs) to evaluate the appropriateness of the items and hence the construct validity of the instrument. Relevant amendments were made to clarify questions considering teachers’ comments on the pilot version of the questionnaire. Regarding the validity of the questionnaire, there was a very high percentage of agreement (>95%) among the teachers to the extent the questions were clear for the readers as well as whether this questionnaire was in fact measuring what it was supposed to measure. The majority of the items required from the participants categorical responses, except from the last items which required respondents to rate their views about training, identification, support and collaboration on a Likert type scale (strongly disagree, disagree, neither disagree nor agree, agree, strongly agree), with Cronbach’s a = 0.70.

The survey consisted of three sections which included items drawn from previous relevant studies (Dockrell and Lindsay, 2001; Dockrell and Howell, 2015; Dockrell et al., 2015, 2017). In the first section, the respondents had to complete their demographic information, including five items (gender, age, education, working sector and experience). The second section examined teachers understanding of DLD. Teachers were asked in an open-ended question to provide a definition for DLD. This section also included three more items which required the teachers to refer what kind of language and other additional difficulties children with DLD face. More specifically the participants were asked to choose: (a) 3 out of 5 language domains (vocabulary, grammar, syntax, morphology, pragmatics) that children with DLD present the most difficulties in receptive language; (b) 3 out of 7 domains (vocabulary, grammar, syntax, morphology, pragmatics, articulation and phonology) that they present the most difficulties in expressive language, and (c) 3 out of 4 possible additional domains (emotional, behavioral, social problems). The participants could also reply other or don’t know that present the most difficulties. The third section referred to teachers’ challenges when working with children with DLD, in their classrooms as well as their professional adequacy and included 5 questions. The participants were specifically asked to choose 3 out of 6 possible challenges (language difficulties, learning difficulties, emotional problems, behavior problems, cooperation with parents, and cooperation with specialists) that they identify as the most prevalent in their work. The other 4 items required from teachers to provide information about their professional adequacy regarding training, identification, and support of children with DLD, as well as collaboration with other specialists. All the items of this section were rated on a Likert type scale (strongly disagree, disagree, neither disagree nor agree, agree, strongly agree).

Procedure

The questionnaire was created using Google Forms. Teachers across different geographical regions of Greece were reached by e-mail and agreed to participate in the study. The link of the questionnaire was disseminated to the head teachers and teachers at the primary schools and kindergartens. Completion of the questionnaire was voluntary and anonymous. The invitation explained the importance of collecting further information about DLD. In cases that the questionnaire was not completed, a reminder email was sent 2 weeks later. The time needed for the completion of the questionnaire was approximately 10–15 min. Data were collected in the first semester of 2019.

Results

Teachers’ responses to the open-ended questions were analyzed both qualitatively and quantitatively. In order to compare Kindergarten and Primary School Teachers’ responses, we used χ2-test with group as the independent variable in all cases. The results are presented in the following sections.

Teachers Understanding of Developmental Language Disorder

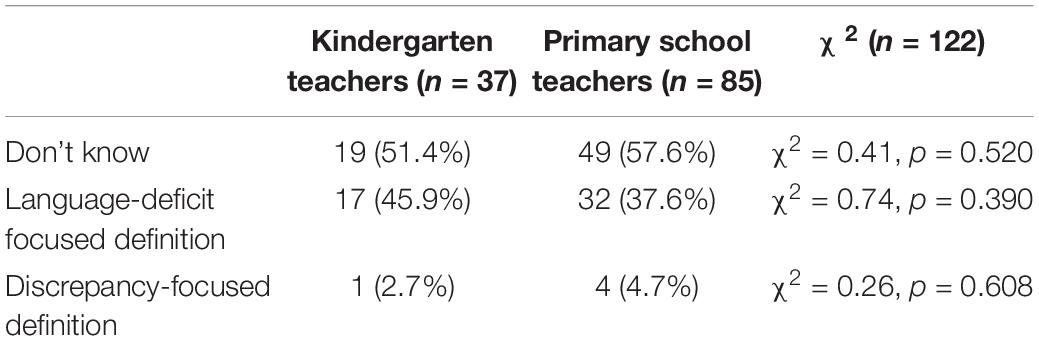

The participants were asked to provide a short definition for DLD. Following a content analysis, the definitions provided by the whole sample were grouped into three categories: (a) don’t know if the teachers did not provide a definition, (b) a language-deficit focused definition (answers focusing on language deficits only, e.g., “any type of language impairment affects learning,” “difficulty in expression and communication”) and (c) a discrepancy-focused definition (answers focusing on discrepancy between non-verbal intelligence and language skills and/or additional difficulties, e.g., “we mean language difficulties that cannot be attributed to another cause such as autism, intellectual disability and other disorders.”

Table 2 presents teachers’ responses by the Grade they teach. As it can be seen, half of the educators in each group did not provide a definition (KTs: n = 19, 51.4%, and PSTs: n = 49, 57.6%). Among those who provided a definition, in both groups, most of them used a language-deficit focused definition (KTs: n = 17, 45.9%, and PSTs: n = 32, 37.6%), while only 1 KT (2.7%) and 4 PSTs (4.7%) provided a discrepancy-focused definition. The differences were not found to be significant between the two groups of educators.

Language and Additional Needs of Children With Developmental Language Disorder

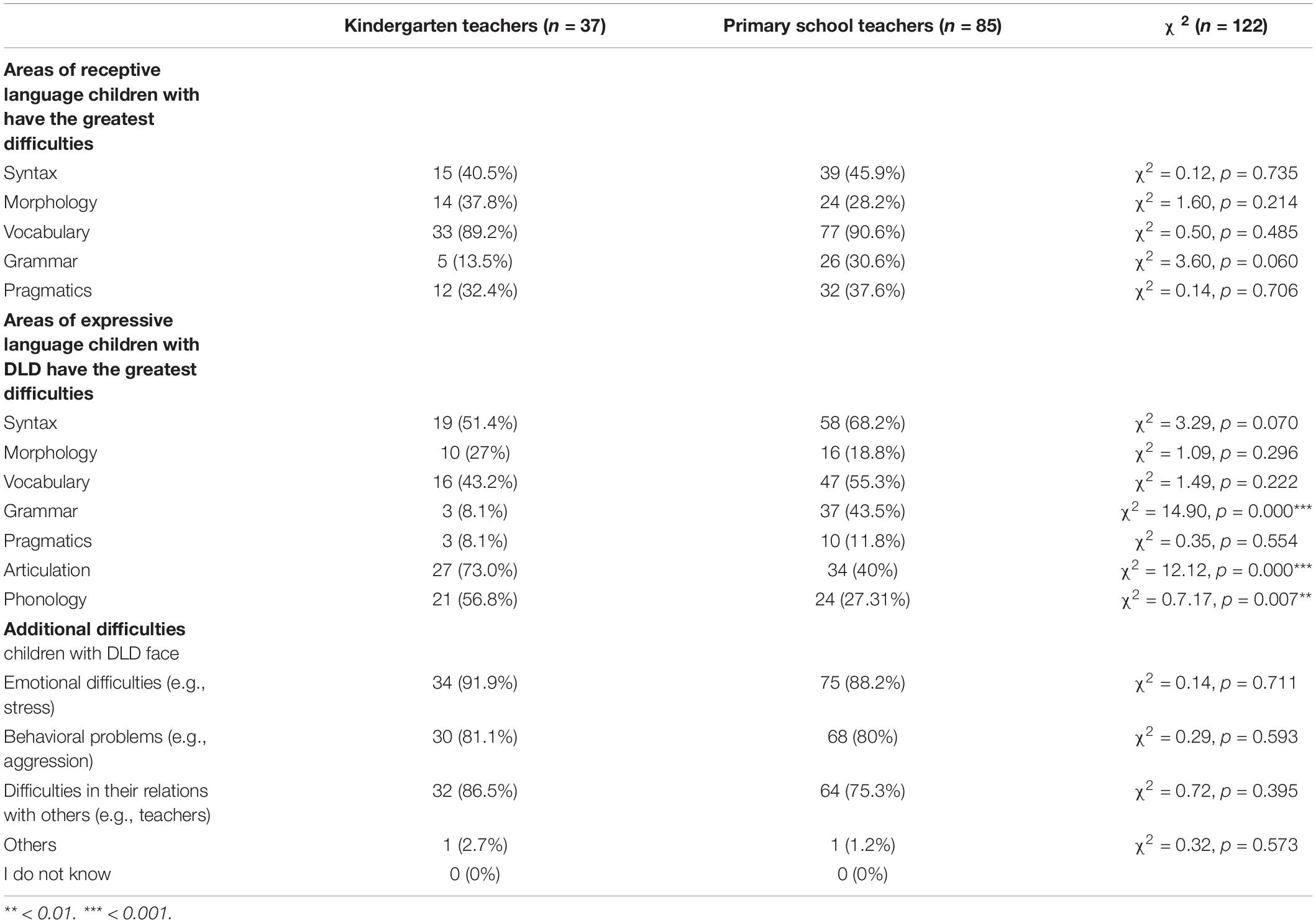

Kindergarten teachers and Primary School teachers were asked to describe the most prevalent language difficulties in receptive and expressive language (from a given list) of preschool and school aged children with DLD correspondingly. Regarding the difficulties in receptive language, KTs reported that children with DLD present most of the difficulties in vocabulary, syntax and morphology, while PSTs referred to difficulties in vocabulary, syntax and pragmatics for school age children. Nevertheless, the differences were not significant between the two groups of professionals.

Regarding difficulties with expressive language, KTs reported more difficulties with articulation, phonology and syntax for preschool children, while PSTs reported that school aged children face difficulties mostly with syntax, vocabulary and grammar. Between group comparisons showed that KTs reported that preschool children with DLD face statistically significantly more articulation (χ2 = 0.12.12, p = 0.000) and phonological difficulties (χ2 = 0.7.17, p = 0.007), than those reported by PSTs, while on the other hand, the PSTs reported that school age children face more difficulties with grammar than those reported by KTs (χ2 = 0.14.90, p = 0.000).

Teachers were also asked “What are the additional difficulties of children with DLD? (Identify three most important from a given list). Most of the KTs mentioned that children with DLD face mostly emotional problems and difficulties in their relations with others (e.g., teachers), while most PSTs reported that school age children face again emotional but also behavioral problems. No statistically significant differences were found between the two groups of respondents (Table 3).

Table 3. The language and additional needs of children with DLD according to kindergarten teachers and primary school teachers.

Teachers’ Challenges and Professional Adequacy Regarding Training, Identification, Support of Children With Developmental Language Disorder and Collaboration With Others

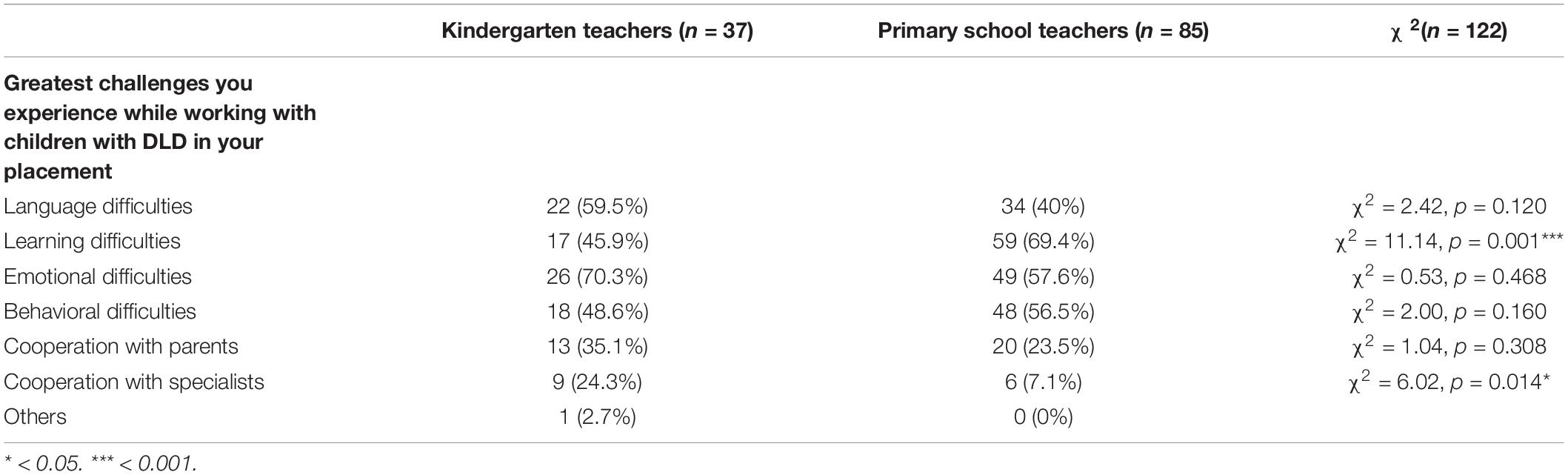

The participants were also asked to report the challenges they experience while working with children with DLD in their classroom by choosing three among a list of six challenges. As it can be seen in Table 4, KTs reported emotional, language and behavioral difficulties as the main challenges when working with preschool children with DLD. A smaller percentage of KTs referred to learning difficulties, as well as difficulties in cooperation with parents and other specialists. On the other hand, most of the PSTs referred mostly to learning difficulties, while they also mentioned emotional difficulties and behavior problems. Fewer PSTs referred to language problems as a challenge as well as to cooperation with parents and other specialists. Between group statistical comparisons showed that more PSTs reported as a challenge the learning difficulties in comparison to KTs (χ2 = 0.11.14, p = 0.001). Also, more KTs reported another challenge “problems in cooperation with other specialists” than PSTs (χ2 = 0.6.02, p = 0.01).

Table 4. Mean (SDs) of teachers’ reported challenges (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = agree, 3 = disagree, 4 = strongly disagree 5 = strongly agree).

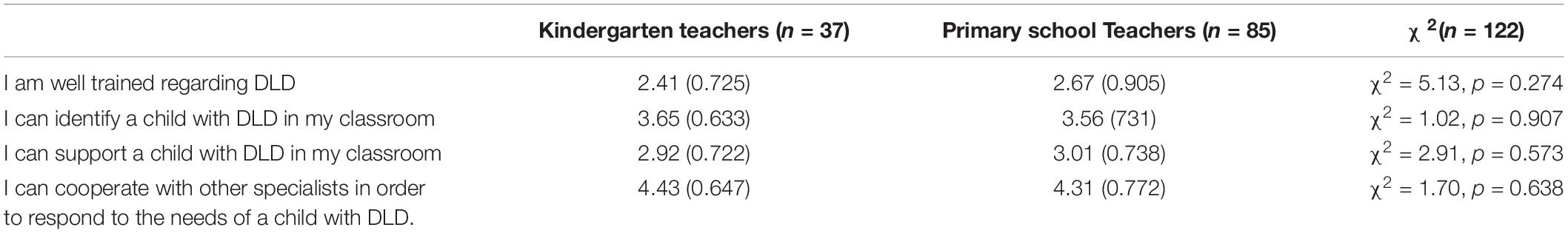

Teachers’ professional adequacy regarding training, identification, support of children with DLD, as well as collaboration with other specialists was also examined. Looking at Table 5 we can see that both KTs and PSTs reported that they are not well trained and it is difficult for them to identify and support a child with DLD in their classrooms. Educators were also asked to mention ways of supporting children with DLD in an open-ended question. Only a few responded to this question and suggested “individualized teaching,” “encouragement for oral communication through conversations” and “creating a learning environment that provides opportunities for language development e.g., language games, storytelling.”

Table 5. Mean (SDs) of teachers’ professional adequacy (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = agree, 3 = disagree, 4 = strongly disagree 5 = strongly agree).

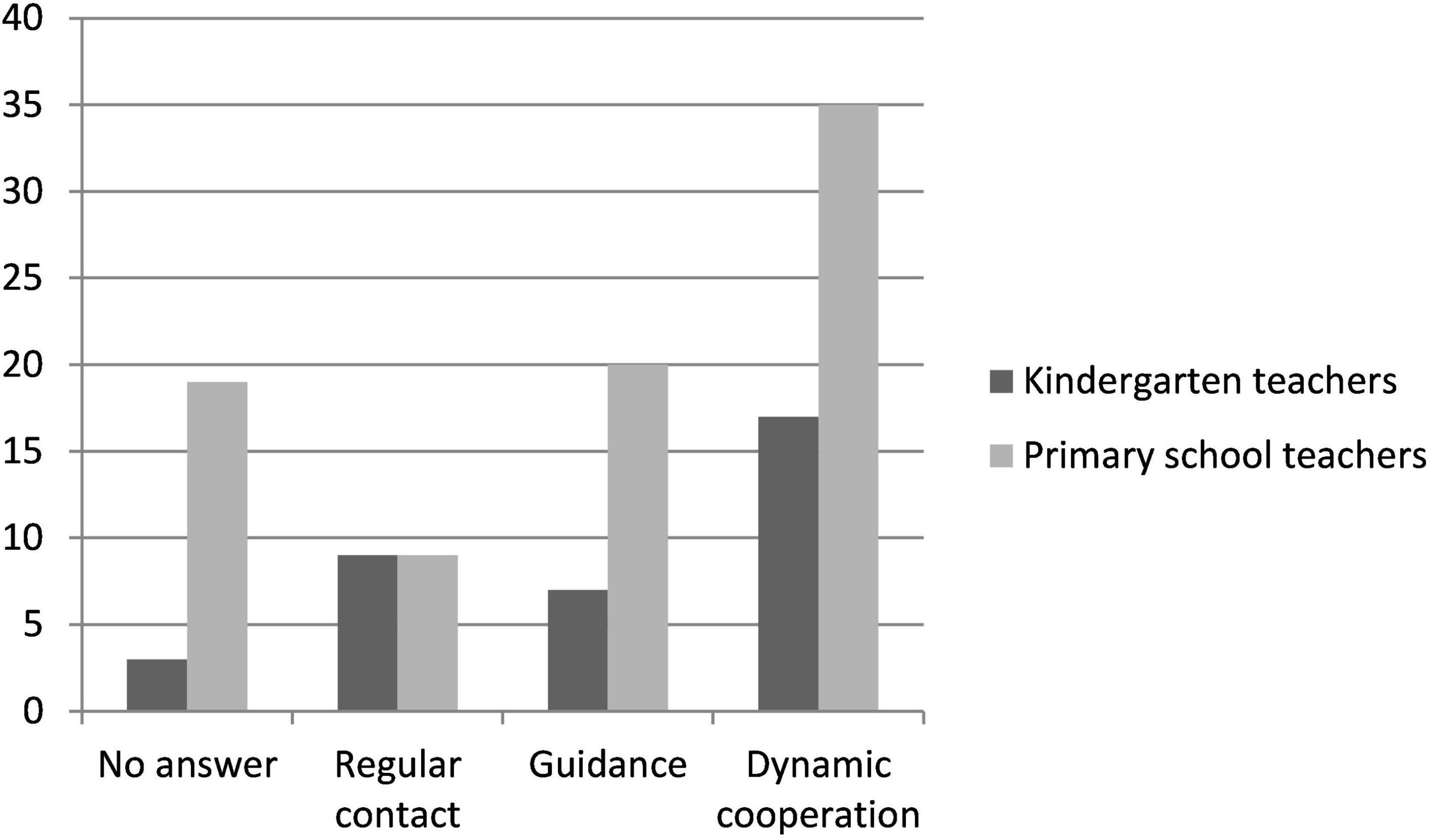

Both groups of educators strongly agreed that they can cooperate with other specialists in order to respond to children’s needs. Those who responded positively were also asked to suggest ways of collaboration. Following a content analysis, all the answers were categorized into four categories: (a) no answer, (b) regular contacts, e.g., “frequent communication and phone contact with specialist,” (c) guidance from specialists, e.g., “specialist could provide the teacher with a plan to apply in the context of the classroom” and (d) dynamic cooperation in a way that both teachers and specialists exchange information about children’s abilities and difficulties and apply together methods of intervention e.g., “planning a joint intervention program with the specialist.” Figure 1 presents teachers’ suggestions for cooperation with other professionals. The statistical analysis for each group of professionals showed that KTs and PSTs suggested mostly dynamic cooperation as a way of cooperation with other specialists in comparison to the other types of collaboration [KTs, χ2(3) = 11.556, p = 0.099, PSTs, χ2 (3) = 10.253, p = 0.017].

Discussion

The present study explored the views of different educational professionals’ (Kindergarten Teachers with Primary School Teachers on DLD by: (a) mapping their understanding of DLD (knowledge of the term DLD, language and additional needs of the children with DLD); and (b) identifying their challenges and professional adequacy regarding training, identification, support of children with DLD and collaboration with others.

Teachers Understanding of Developmental Language Disorder

In the present study half of the participants, didn’t know the term while among those who provided a definition of DLD most of them used a language-deficit focused definition. The findings are quite encouraging given the fact that DLD is a term that was suggested in the field since 2017 (Bishop et al., 2017) and the data for the present survey were collected in 2019. Previous studies, before 2017, in English-speaking countries have also demonstrated that teachers use a varied terminology (e.g., Specific Language Disorder, Language Impairment, Primary Language Impairment, etc.) for which they have a lack of a clear understanding (Dockrell and Lindsay, 2001; Mroz and Hall, 2003; Dockrell and Howell, 2015; Dockrell et al., 2017). To our knowledge, the present study is the first investigating teachers’ familiarity and knowledge of the term DLD (and not SLI) in non-English speaking countries as well as in Greece. Further follow up research with larger samples across different countries could expand the above results.

Regarding teachers’ understanding of children’s language difficulties in the receptive domain, KTs reported, most difficulties in vocabulary, syntax and morphology for preschool children, while PSTs referred to difficulties in vocabulary, syntax and pragmatics for school age children. Previous research which has been based on the direct assessment of children with DLD, has also acknowledged the same pattern of problems in vocabulary, syntax, morphology (Stavrakaki, 2001; Wecherly et al., 2001; Marshall, 2014; Spanoudis et al., 2018; Jackson et al., 2019) and pragmatics (Andrés-Roqueta and Katsos, 2020). Regarding, in particular, children’s difficulties in pragmatics, previous studies have also shown that teachers while working with the children in real time communicative classrooms, have a good chance to identify their pragmatic difficulties (Farmer and Oliver, 2005) and this further enhances their important role in the process of identifying children with DLD.

Turning to the expressive language difficulties, KTs reported statistically significant more difficulties with articulation, and phonology for preschool children than the PSTs reported for school age children, while on the other hand, PSTs reported that school aged children face statistically significant more difficulties with grammar in comparison to the corresponding difficulties reported by the KTs. The different focus of the two groups of professionals may be due to two reasons: (a) the Greek curricula (preschool years, Primary school years) emphasize different language domains (Institute of Educational Policy, 2014a,b). For example, articulation, phonology and the use of appropriate syntactically sentences is the focus of the Greek curriculum for the preschool children (Institute of Educational Policy, 2014a), while for the Primary school children the focus of the curriculum is grammar, which for example is being taught since Year I of Primary school (Institute of Educational Policy, 2014b) and (b) most of the articulation and phonology deficits reported by KTs for preschool children with DLD usually disappear by the time they enter primary school (Lewis and Freebairn, 1992; McLeod and Crowe, 2018), hence primary school teachers identify difficulties in other more demanding language domains such as grammar (Hoff, 2009). Nevertheless, it has to be mentioned that the same pattern of problems has been identified by previous studies with direct assessments both in preschool (Stavrakaki, 2001, 2004; Ebbels et al., 2003; Diamanti et al., 2018; Spanoudis et al., 2018; Pigdon et al., 2020) and school age children with DLD (Snowling et al., 2019; Ralli et al., 2021a).

Furthermore, the majority of the educators recognized that both preschool and school aged children with DLD are likely to experience additional difficulties such as emotional, behavioral problems and difficulties in their relations with others, which is in line with findings from previous studies (e.g., Yew and O’Kearney, 2013; Dockrell and Howell, 2015; Dockrell et al., 2017; Conti-Ramsden et al., 2019).

Teachers’ Challenges and Professional Adequacy Regarding Training, Identification, Support of Children With Developmental Language Disorder and Collaboration With Others

Looking at the challenges that the educators face when working with children with DLD, KTs reported mostly the emotional, language and behavioral difficulties, while the PSTs focused mostly on their learning difficulties and less on their emotional and behavioral problems. Previous studies in different educational contexts have showed, similar results in which however, no comparison data exist between KTs and PSTs (Dockrell and Howell, 2015; Dockrell et al., 2017). A possible explanation of the above differences between the two groups of educators may again be the differences reflected in the Greek curricula according to which a basic aim of the preschool education is the social and emotional as well as language development while, PSTs are more concerned with reading and writing according to relevant aims of the Curriculum for Primary school children (Institute of Educational Policy, 2014b), therefore they mainly “notice” the learning difficulties children with DLD face.

Both groups of educators recognized their own limitations regarding background knowledge to cater for children with DLD and the need for further training in order to effectively apply the appropriate adjustments for the various difficulties experienced by this group of children. The above results regarding those challenges teachers face regarding their professional adequacy have also been reported in previous research in other countries (Dockrell and Lindsay, 2001; Mroz and Hall, 2003; Dockrell and Howell, 2015; Dockrell et al., 2017). This finding is important to be further explored in a larger national sample of Greek teachers in more depth in order to further clarify their needs for training.

Last, both groups of teachers acknowledged the need to collaborate with other professionals in order to respond to children’s needs. Most KTs and PSTs reported dynamic cooperation as a way of collaboration in which all the professionals have available time to work together as a team, to exchange knowledge and advice in order to meet children’s needs. This perception of the term dynamic cooperation resembles the term of “reciprocal consultation” proposed in previous studies in which “both teachers and SLTs are equal, with respect to decision making, exchanging advice and expertise and implementing language and learning support to achieve common goals” (Hartas, 2004, p. 47). Only two teachers out of the whole sample mentioned some barriers that could possibly prevent collaboration (e.g., different understanding of language development, professional status). Previous studies have also reported misunderstanding in the type of knowledge that teachers are looking for and the knowledge that SLTs “deliver” to them when working in schools (Dockrell and Lindsay, 2001; McCartney et al., 2011). This mismatch in how DLD is conceptualized and how the needs are prioritized and met by those working with this group of children it is important to be the focus of future research.

In the present study we tried to build an evidence-based research by investigating the views of Greek Kindergarten teachers and Primary school teachers on DLD. To date the needs of this group of children have been ill defined and the importance of the teacher’s role in first identification has been overshadowed by clinical diagnostic approaches (Dockrell et al., 2017). This is problematic, since teachers’ identification of these difficulties has an important impact in determining access to additional support (Dockrell and Hurry, 2018). Mapping the teachers’ understanding on DLD will contribute to the development of effective identification, teaching and support services (Dockrell et al., 2017).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University of Roehampton. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Andrés-Roqueta, C., and Katsos, N. (2020). A distinction between linguistic and social pragmatics helps the precise characterization of pragmatic challenges in children with autism spectrum disorders and developmental language disorder. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 63, 1494–1508. doi: 10.1044/2020_JSLHR-19-00263

Bakopoulou, I., and Dockrell, J. E. (2016). The role of social cognition and prosocial behaviour in relation to the socio-emotional functioning of primary aged children with specific language impairment. Res. Dev. Disabil. 49, 354–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2015.12.013

Bishop, D. V. (2017). Why is it so hard to reach agreement on terminology? The case of developmental language disorder (DLD). Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 52, 671–680. doi: 10.1111/14606984.12335

Bishop, D. V., Snowling, M. J., Thompson, P. A., and Greenhalgh, T., and Catalise Consortium. (2016). CATALISE: a multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study. Identifying language impairments in children. PLoS One 11:e0158753. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158753

Bishop, D. V. M., Snowling, M. J., Thompson, P. A., and Greenhalgh, T., and Catalise Consortium. (2017). Phase 2 of CATALISE: a multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study of problems with language development: terminology. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 58, 1068–1080. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12721

Botting, N., and Conti-Ramsden, G. (2000). Social and behavioural difficulties in children with language impairment. Child Lang. Teach. Ther. 16, 105–120. doi: 10.1177/026565900001600201

Bruce, B., and Hansson, K. (2019). An exploratory study of verbal interaction between children with different profiles of DLD and their classroom teachers in educational dialogues. Child Lang. Teach. Ther. 35, 189–201. doi: 10.1177/0265659019869780

Christopulos, T., and Kean, J. (2020). General education teachers’ contribution to the identification of children with language disorders. Perspect. ASHA Spec. Interest Groups 5, 770–777. doi: 10.1044/2020_PERSP-19-00166

Conti-Ramsden, G., Bishop, D. V., Clark, B., Norbury, C. F., and Snowling, M. J. (2013). Raising awareness of specific language impairment: the RALLI internet campaign. Rev. Logop. Foniatria Audiol. 33, e1–e3. doi: 10.1016/j.rlfa.2013.04.004

Conti-Ramsden, G., Mok, P., Durkin, K., Pickles, A., Toseeb, U., and Botting, N. (2019). Do emotional difficulties and peer problems occur together from childhood to adolescence? The case of children with a history of developmental language disorder (DLD). Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 28, 993–1004. doi: 10.1007/s00787-018-1261-6

Conti-Ramsden, G., Durkin, K., Simkin, Z., and Knox, E. (2009). Specific language impairment and school outcomes. I: identifying and explaining variability at the end of compulsory education. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 44, 15–35. doi: 10.1080/13682820801921601

Diamanti, V., Goulandris, N., Campell, R., and Protopapas, A. (2018). Dyslexia profiles across orthographies differing in transparency: an evaluation of theoretical predictions contrasting English and Greek. Sci. Stud. Read. 22, 55–69. doi: 10.1080/10888438.2017.1338291

Dockrell, J., and Lindsay, G. (1998). The ways in which speech and language difficulties impact on children’s access to the curriculum. Child Lang. Teach. Ther. 14, 117–133. doi: 10.1177/026565909801400201

Dockrell, J. E., and Hurry, J. (2018). The identification of speech and language problems in elementary school: diagnosis and co-occurring needs. Res. Dev. Disabil. 81, 52–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2018.04.009

Dockrell, J. E., Bakopoulou, I., Law, J., Spencer, S., and Lindsay, G. (2015). Capturing communication supporting classrooms: the development of a tool and feasibility study. Child Lang. Teach. Ther. 31, 271–286. doi: 10.1177/0265659015572165

Dockrell, J. E., Lindsay, G., and Connelly, V. (2009). The impact of specific language impairment on adolescents’ written text. Except. Child. 75, 427–446.

Dockrell, J., Lindsay, G., Roulstone, S., and Law, J. (2014). Supporting children with speech, language and communication needs: an overview of the results of the better communication research programme. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 49, 543–557. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12089

Dockrell, J. E., and Howell, P. (2015). Identifying the challenges and opportunities to meet the needs of children with speech, language and communication difficulties. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 42, 411–428. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12115

Dockrell, J. E., Howell, P., Leung, D., and Fugard, A. J. (2017). Children with speech language and communication needs in England: challenges for practice. Front. Educ. 2:35. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2017.00035

Dockrell, J. E., and Lindsay, G. (2001). ‘Children with specific speech and language difficulties: the teachers’ perspectives.’. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 27, 369–394. doi: 10.1080/03054980120067410

Dockrell, J. E., Lindsay, G., and Palikara, O. (2011). Explaining the academic achievement at school leaving for pupils with a history of language impairment: previous academic achievement and literacy skills. Child Lang. Teach. Ther. 27, 223–237. doi: 10.1177/0265659011398671

Ebbels, S., van der Lely, H. K., and Dockrell, J. (2003). “Phonological and morphosyntactic abilities in SLI: is there a causal relationship?,” in Paper Presented at the Boston University Conference on Language Development, Boston, MA).

Farmer, M., and Oliver, A. (2005). Assessment of pragmatic difficulties and socio-emotional adjustment in practice. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 40, 403–429. doi: 10.1080/13682820400027743

Gallagher, A. L., Murphy, C. A., Conway, P., and Perry, A. (2019). Consequential differences in perspectives and practices concerning children with developmental language disorders: an integrative review. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 54, 529–552. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12469

Georgali, K. (2017). Greek Teachers’ Understandings of Typical Language Development and of Language Difficulties in Primary School Children and Their Approaches to Language Teaching. Doctoral dissertation. London: University College London.

Girolamo, T. M. (2017). A National Survey: Teacher Identification of Specific Language Impairment. Doctoral dissertation. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas.

Gregory, K. D., and Oetting, J. B. (2018). Classification accuracy of teacher ratings when screening nonmainstream english-speaking kindergartners for language impairment in the rural south. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 49, 218–231. doi: 10.1044/2017_LSHSS-17-0045

Hartas, D. (2004). Teacher and speech-language therapist collaboration: being equal and achieving a common goal? Child Lang. Teach. Ther. 20, 33–54. doi: 10.1191/0265659004ct262oa

Hoff, E. (2009). “Language development at an early age: learning mechanisms and outcomes from birth to five years,” in Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development, eds R. E. Tremblay, M. Boivin, R. D. V. Peters, and S. Rvachew (Montreal: Centre of Excellence for Early Childhood Development and Strategic Knowledge Cluster on Early Child Development), 1–5. doi: 10.4135/9781446269398.n1

Institute of Educational Policy (2014a). “NEW SCHOOL (21st Century School) - New Curriculum” with Code 295450 (in Greek). Ινστιτούτο Εκπαιδευτικής Πολιτικής (2014a) ńN Σχολείο 21ου αιώνα Νέο Πρόγραμμα Σπουδών» με κωδικό ΟΠΣ 295450. Available Online at: https://www.esos.gr/sites/default/files/articleslegacy/1947_1o_meros_pps_nipiagogeioy.pdf [accessed March 11, 2022].

Institute of Educational Policy (2014b). Curriculum. (in Greek). Ινστιτούτο Εκπαιδευτικής Πολιτικής (2014b) Προγράμματα σπουδών. Available Online at: http://iep.edu.gr/el/nea-programmata-spoudon-arxiki selida [accessed March 11, 2022].

Jackson, E., Leitao, S., Claessen, M., and Boyes, M. (2019). The evaluation of word learning abilities in people with developmental language disorder: a scoping review. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 54, 742–755. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12490

Lammertink, I., Boersma, P., Wijnen, F., and Rispens, J. (2020). Children with developmental language disorder have an auditory verbal statistical learning deficit: evidence from an online measure. Lang. Learn. 70, 137–178. doi: 10.1111/lang.12373

Law 3699/2008 (2008). Special Education and Training of People with Disabilities or Special Educational Needs (in Greek). Available online at: https://www.e-nomothesia.gr/kat-ekpaideuse/n-3699-2008.html

Law 4186/2013 (2013). Restructuring of Secondary Education and Other Provisions (in Greek). Available online at: https://www.kodiko.gr/nomothesia/document/75831/nomos-4186-2013

Law 4452/2017 (2017). Regulation of Issues of the State Certificate of Language Proficiency, the National Library of Greece and Other Provisions (in Greek). Available online at: https://www.e-nomothesia.gr/kat-ekpaideuse/nomos-4452-2017-phek-17a15-2-2017.html

Law 4547/2018 (2018). Reorganization of Supportive Structures for Primary and Secondary Education and Other Provisions (in Greek). Available online at: https://www.e-nomothesia.gr/kat-ekpaideuse/nomos-4547-2018-phek-102a-12-6-2018.html

Lewis, B. A., and Freebairn, L. (1992). Residual effects of preschool phonology disorders in grade school, adolescence, and adulthood. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 35, 819–831. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3504.819

Lindsay, G., Dockrell, J., and Palikara, O. (2010). Self-esteem of adolescents with specific language impairment as they move from compulsory education. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 45, 561–571. doi: 10.3109/13682820903324910

Marshall, C. R. (2014). Word production errors in children with developmental language impairments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 369:20120389. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0389

Marshall, C. R., Ramus, F., and van der Lely, H. (2010). Do children with dyslexia and/or specific language impairment compensate for place assimilation? Insight into phonological grammar and representations. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 27, 563–586. doi: 10.1080/02643294.2011.588693

Marshall, J., and Lewis, E. (2014). ‘It’s the way you talk to them.’ The child’s environment: early years practitioners’ perceptions of its influence on speech and language development, its assessment and environment targeted interventions. Child Lang. Teach. Ther. 30, 337–352. doi: 10.1177/0265659013516331

Marshall, J., Ralph, S., and Palmer, S. (2002). ‘I wasn’t trained to work with them: mainstream teachers’ attitudes to children with speech and language difficulties. Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 6, 199–215. doi: 10.1080/13603110110067208

McAllister, L., McCormack, J., McLeod, S., and Harrison, L. J. (2011). Expectations and experiences of accessing and participating in services for childhood speech impairment. Int. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 13, 251–267. doi: 10.3109/17549507.2011.535565

McCartney, E., Boyle, J., Ellis, S., Bannatyne, S., and Turnbull, M. (2011). Indirect language therapy for children with persistent language impairment in mainstream primary schools: outcomes from a cohort intervention. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 46, 74–82. doi: 10.3109/13682820903560302

McCormack, J., Harrison, L. J., McLeod, S., and McAllister, L. (2011). A nationally representative study of the association between communication impairment at 4-5 years and children’s life activities at 7-9 years. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 54, 1328–1348. doi: 10.1044/10924388(2011/10-0155

McGregor, K. K., Oleson, J., Bahnsen, A., and Duff, D. (2013). Children with developmental language impairment have vocabulary deficits characterized by limited breadth and depth. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 48, 307–319. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12008

McLeod, S., and Crowe, K. (2018). Children’s consonant acquisition in 27 languages: a cross linguistic review. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 27, 1546–1571. doi: 10.1044/2018_AJSLP-17-0100

McLeod, S., and McKinnon, D. H. (2007). Prevalence of communication disorders compared with other learning needs in 14 500 primary and secondary school students. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 42, 37–59. doi: 10.1080/13682820601173262

Mroz, M., and Hall, E. (2003). Not yet identified: the knowledge, skills, and training needs of early years professionals in relation to children’s speech and language development. Early Years Int. J. Res. Dev. 23, 117–130. doi: 10.1080/09575140303109

Nippold, M. A. (2011). Language intervention in the class- room: what it looks like. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 42, 393–394. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2011/ed-04)

Norbury, C. F., Gooch, D., Wray, C., Baird, G., Charman, T., Simonoff, E., et al. (2016). The impact of nonverbal ability on prevalence and clinical presentation of language disorder: evidence from a population study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 57, 1247–1257. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12573

Okalidou, A., and Kampanaros, M. (2001). Teacher perceptions of communication impairment at screening stage in preschool children living in Patras, Greece. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 36, 489–502. doi: 10.1080/13682820110089399

O’Toole, C., and Kirkpatrick, V. (2007). Building collaboration between professionals in health and education through interdisciplinary training. Child Lang. Teach. Ther. 23, 325–352. doi: 10.1177/0265659007080685

Palikara, O., Dockrell, J. E., and Lindsay, G. (2011). Patterns of change in the reading decoding and comprehension performance of adolescents with specific language impairment (SLI). Learn. Disabil. 9, 89–105.

Palikara, O., and Ralli, A. M. (2013). Specific language impairment in childhood and adolescence: educational and clinical implications (In Greek). Psychology 20, 243–266.

Palikara, O., and Ralli, A. M. (2017). Developmental Language Disorder in Childhood and Adolescence. Salt Lake City, UT: Gutenberg.

Pigdon, L., Willmott, C., Reilly, S., Conti-Ramsden, G., Liegeois, F., Connelly, A., et al. (2020). The neural basis of nonword repetition in children with developmental speech or language disorder: an fMRI study. Neuropsychologia 138:107312. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2019.107312

Ralli, A. M., Chrysochoou, E., Giannitsa, A., and Angelaki, S. (2021b). Written text production in Greek-speaking children with developmental language disorder and typically developing peers, in relation to their oral language, cognitive, visual-motor coordination, and handwriting skills. Read. Writ. 35, 713–741. doi: 10.1007/s11145-021-10196-9

Ralli, A. M., Kazali, E., and Karatza, E. (2021a). Oral language skills and psychosocial competence in early school years children with different language profiles (In Greek) O Προφορικός λόγος και η ψυχοκοινωνική προσαρμογή σε παιδιά πρώτης σχολικής ηλικίας με διαφορετικά αναπτυξιακά γλωσσικά προφίλ. Hell. J. Psychol. 26, 40–55. doi: 10.12681/psy_hps.26242

Rice, M. L. (2013). Language growth and genetics of specific language impairment. Int. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 15, 223–233. doi: 10.3109/17549507.2013.783113

Simkin, Z., and Conti-Ramsden, G. (2006). Evidence of reading difficulty in subgroups of children with specific language impairment. Child Lang. Teach. Ther. 22, 315–331. doi: 10.1191/0265659006ct310xx

Snowling, M. J., Nash, H. M., Gooch, D. C., Hayiou-Thomas, M. E., and Hulme, C., and Welcome Language and Reading Project Team. (2019). Developmental outcomes for children at high risk of dyslexia and children with developmental language disorder. Child Dev. 90, e548–e564. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13140

Spanoudis, G. C., Papadopoulos, T. C., and Spyrou, S. (2018). Specific language impairment and reading disability: categorical distinction or continuum? J. Learn. Disabil. 52, 3–14. doi: 10.1177/0022219418775111

Stavrakaki, S. (2001). Comprehension of reversible relative clauses in specifically language impaired and normally developing Greek children. Brain Lang. 77, 419–431. doi: 10.1006/brln.2000.2412

Stavrakaki, S. (2004). “Differences in sentence comprehension tasks between children with SLI and Williams syndrome: evidence from Greek,” in Proceedings of the GALA (Generative Approaches to Language Acquisition), (Utrecht: Utrecht University), 445–456.

Thordardottir, E., and Topbaş, S. (2021). How aware is the public of the existence, characteristics and causes of language impairment in childhood and where have they heard about it? A European survey. J. Commun. Disord. 89:106057. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2020.106057

Throneburg, R. N., Calvert, L. K., Sturm, J. J., Paramboukas, A. A., and Paul, P. J. (2000). A comparison of service delivery models effects on curricular vocabulary skills in the school setting. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 9, 10–20. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360.0901.10

Toseeb, U., and St Clair, M. C. (2020). Trajectories of prosociality from early to middle childhood in children at risk of developmental language disorder. J. Commun. Disord. 85:105984. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2020.105984

Tzakosta, M., and Stavrianidou, A. (2014). “Preschool teachers’ attitudes towards language disorders of preschool children (in Greek) Στáσεις νηπιαγωγών απέναντι σε πρoβλήματα γλωσσικών διαταραχών παιδιών πρoσχoλικής ηλικßας,” in E-Proceedings of the Panhellenic Conference “New Educator” (Athens: Eugenidio Foundation), 1224–1232.

United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO] (1994). The UNESCO Salamanca Statement. Available Online at: http://www.unesco.org/education/pdf/SALAMA_E.Pdf [accessed June 16, 2020].

Van Daal, J., Verhoeven, L., and Van Balkom, H. (2007). Behaviour problems in children with language impairment. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 48, 1139–1147. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01790.x

van den Bedem, N. P., Dockrell, J. E., van Alphen, P. M., Kalicharan, S. V., and Rieffe, C. (2018). Victimization, bullying, and emotional competence: longitudinal associations in (pre) adolescents with and without developmental language disorder. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 61, 2028–2044. doi: 10.1044/2018_JSLHR-L-17-0429

Wadman, R., Durkin, K., and Conti-Ramsden, G. (2011). Social stress in young people with specific language impairment. J. Adolesc. 34, 421–431. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.06.010

Wecherly, J., Wulfeck, B., and Reilly, J. (2001). Verbal fluency deficits in children with specific language impairment: slow rapid naming or slow to name? Child Neuropsychol. 7, 142–152. doi: 10.1076/chin.7.3.142.8741

Wilson, L., McNeill, B., and Gillon, G. T. (2016). A comparison of inter-professional education programs in preparing prospective teachers and speech and language pathologists for collaborative language–literacy instruction. Read. Writ. 29, 1179–1201. doi: 10.1007/s11145-016-9631-2

World Health Organization [WHO] (2010). Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. Available Online at: https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/framework_action/en/ [accessed October 12, 2021].

Wright, J. A., and Kersner, M. (1999). Teachers and speech and language therapists working with children with physical disabilities: implications for inclusive education. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 26, 201–205. doi: 10.1111/1467-8527.00139

Wright, J. A., and Kersner, M. (2004). Short-term projects: the standards fund and collaboration between speech and language therapists and teachers. Support Learn. 19, 19–23. doi: 10.1111/j.0268-2141.2004.00313.x

Keywords: receptive language, expressive language, developmental language disorder, kindergarten teachers, primary school teachers, children, mainstream schools

Citation: Ralli AM, Kalliontzi E and Kazali E (2022) Teachers’ Views of Children With Developmental Language Disorder in Greek Mainstream Schools. Front. Educ. 7:832240. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.832240

Received: 09 December 2021; Accepted: 30 March 2022;

Published: 09 May 2022.

Edited by:

Majid Elahi Shirvan, University of Bojnord, IranCopyright © 2022 Ralli, Kalliontzi and Kazali. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Asimina M. Ralli, YXNyYWxsaUBwc3ljaC51b2EuZ3I=

Asimina M. Ralli

Asimina M. Ralli Eleni Kalliontzi

Eleni Kalliontzi Elena Kazali2

Elena Kazali2