- 1South Lanarkshire Psychological Services, South Lanarkshire, United Kingdom

- 2School of Environment, Education and Development, Manchester Institute of Education, The University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom

Background: The academic attainment of care experienced young people (CEYP) is consistently reported as below the national average. Studies emphasize associations between low academic attainment and poor life outcomes. Most research relating to CEYP and education, has highlighted the impact of educational barriers and opportunities on their progression and subsequent attainment. Although, this research is almost exclusively concerned with schooling up to aged 16. Few studies have explored the perspectives and experiences of CEYP in further education, especially in a Scottish context.

Aim: This study aimed to centralize the views of CEYP to gain insight into the perceived achievement opportunities and barriers in FE. Secondly, this study aimed to consider CEYP experiences in FE to inform support services for CEYP.

Sample: Ten CEYP, aged 16–24, studying at a further education college in Scotland participated in the study. Seven further education colleges from geographically diverse regions are represented.

Methods: CEYP participated in semi-structured interviews to share their experience of further education.

Findings: Thematic analysis was used to produce the following main themes: Care experience and personal narratives, valuing further education and navigating support systems.

Conclusion: These findings provide unique insight into CEYP experiences of FE. Opportunities for CEYP achievement in FE included stability of education and accommodation, personalized and financial support and supportive relationships. Reported barriers included care-related challenges, additional support needs (ASN), staff knowledge and labeling practices. Priorities for support service development included increased CEYP informed and led services such as peer mentoring, corporate parenting training and peer education. Implications for FE practice and future research are discussed. A summary of key points for consideration are provided in the Supplementary Material and may be of particular interest to any educational organisation in a corporate parenting role.

Introduction

Care experienced young people (CEYP) encounter significant educational challenges that can negatively impact educational attainment and wellbeing (O’Higgins et al., 2015). Further education (FE) can ameliorate such disruption (O’Neill et al., 2019), when factors likely to promote CEYP success are embedded (O’Higgins et al., 2017). However, research investigating CEYP views regarding education in general is scarce. Yet, high CEYP dropout from FE and poor attainment warrants examination and contributing factors can be considered by listening to CEYP voices (Scottish Government, 2018). The research being reported adopted a socio-constructivist approach seeking to centralize CEYP voice and gain insight into opportunities and barriers for their FE success.

Care and Education in Scotland

The Children (Scotland) Act (1995) describes the term “looked-after child” as an individual; involving one or more of the following residential care, secure care, kinship care, foster care, looked-after at home and adopted (Scottish Government, 2019a). Care experienced (CE) denotes an individual with public care experience of any duration and is preferred by young people, as this term is representing the subject of care instead of the provider (Who Cares? Scotland, 2018) and will be referred to hereafter. CEYP may be temporarily cared for by the state, based on protection grounds, with their status subject to review. CEYP who are removed from parents, who are unable to satisfactorily exercise their parental responsibilities, are issued with a permanence order and placed in long-term care (Scottish Parliament, 2009). 2% of young people were looked-after in 2017 (Scottish Government (2019b) and of this 88% of children were referred on protection grounds, whereas 12% were referred on offense grounds (Scottish Children’s Reporter Administration (SCRA), 2018).

The Children (Scotland) Act (1995) sets out CEYP leaving care on or after their 16th birthday must receive support until their 19th birthday and assessment of need will determine whether support should continue thereafter. From April 2015, CEYP are eligible to be “continuing care” in their placement until they are 21. Legislative policies, such as “Getting It Right for Every Child,” aim to improve cross-service collaboration and support continuing over time (Tormey, 2019). A legislative aspect is CEYP are considered to have additional needs (Education (ASL) (Scotland) Act, 2004). Additional support needs (ASN) is Scottish terminology that may be more readily recognized as special educational needs (Boyle et al., 2016). The proportion of CEYP reporting ASN in FE is 46% and 43% in HE, more than double the national average figure of 20% across other student groups (O’Neill et al., 2019).

Mental health difficulties are over-represented in CEYP (Kelly et al., 2016). Students receiving personalized support reported greater confidence in their educational capabilities (O’Neill et al., 2019). Many CEYP with mental health difficulties relied on voluntary services and felt unable access services in education (Lamont et al., 2009). McGhee and Ross (2015) argue support should be enduring and consistent, without recourse to CE type, age or study setting. Students place importance on knowing services are available to them throughout their studies (O’Neill et al., 2019). A complicating factor is the disproportionately high frequency of school moves among CEYP (McClung and Gayle, 2010). This correlates with poor attendance rates in CEYP (Scottish Government, 2018). Scottish Government (2018) figures show school exclusions rates were significantly higher among CEYP (169 per 1,000) compared to all pupils (27 per 1,000), with the number of accommodation changes in a year mediating the likelihood of exclusion. Despite this, the recent fall in CEYP exclusions is greater compared to general population exclusion rates (Scottish Government, 2018). Such disruption can contribute to socioemotional and learning difficulties (Allen and Vacca, 2010) meaning educational progress is also to be considered.

The Independent Care Review (2019) seeks to centralize CEYP views in the development of the Scottish care system. While this builds on research focusing on barriers and enablers for CEYP studying at college and university (O’Neill et al., 2019), such consideration is in the minority and rarely are CEYP views a central focus. The UN Convention of the Rights of the Child (United Nations (UN), 1990) seeks to promote a change in research dynamics in which young people are experts in their own lives and research can act as a platform to effectively share such insights (Mannay et al., 2019). The following section sets out an overview of FE experiences and educational outcomes and continues to consider the rationale for the role of CEYP voice in the research being reported.

Further Education Experiences and Educational Outcomes

In 2017/18 there were 118,684 full-time entrants to Scottish FE colleges. Of this population, 2,070 were CE, an increase from 1,500 in 2015 [Scottish Funding Council (SFC), 2019]. Whilst FE plays a role supporting vulnerable young people, research in this sector is limited (Herd and Legge, 2017). Most research regarding CEYP experiences in post-secondary education focuses on university outcomes (Geiger and Beltran, 2017) and tends to be quantitative, potentially because funding is based on student performance indicators [Scottish Funding Council (SFC), 2018]. Constructing CEYP’s realities from quantitative data fails to recognize the value of CEYP’s research contributions (Mannay et al., 2019) and is problematic as gaps exist from CEYP who do not disclose their status (Tormey, 2019). In Scotland, FE describes non-school based educational institutions offering qualifications up to Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (SCQF) Level 8. Such qualifications1 are, respectively, considered equivalent to first and second year of university and many are linked to university articulation routes [Scottish Funding Council (SFC), 2019].

FE experience is claimed to support CEYP transition into adult life, offering a structured day involving peer group access (Osborne et al., 2002) and facilitate support that mitigate challenges facing CEYP (Herd and Legge, 2017). Most CEYP study at FE level and are more likely to enter FE at a younger age than their peers. In 2016/17, 41% of CEYP progressed from school to FE in Scotland compared to 27% of all school leavers. However, this proportion dropped to 29% of CEYP remaining in FE 9 months after enrolment (Scottish Government, 2018). From 2018 to 19 CEYP, aged 16–26 who have disclosed their care status, are eligible for supplementary funding in Scotland. CEYP report the supplementary funding supports a comfortable lifestyle while studying (O’Neill et al., 2019). Some students reported they struggle to manage finances, most had ASN or had caring responsibilities. Lipkin (2016) suggests long-term exposure to financial adversity can mean CEYP experience further educational difficulties.

CEYP are less likely to achieve the SCQF level relevant to their age or have a positive post-school destination compared with their peers (Scottish Government, 2018) and are less likely to complete their FE qualification than their non-CE peers [Scottish Funding Council (SFC), 2018]. CEYP achieving one or more SCQF level 52 qualifications increased from 15% in 2009/10 to 44% in 2016/17, across compulsory and post-compulsory education (Scottish Government, 2018). Concurrently, there is an emerging research narrative aiming to celebrate positive experiences of CEYP (Duncalf, 2010; Mendis et al., 2018). Improvements may be due to initiatives aiming to improve CEYP’s attainment, such as “We Can and Must Do Better” (Scottish Executive, 2007). However, compared to 86% of all pupils attaining one or more qualifications at this level, there remains a need for improved educational support for CEYP. In 2018, 4.5% of CEYP went from school to university, compared to 36% of all school leavers [Scottish Funding Council (SFC), 2018]. A complication factor is that these figures do not consider the proportion of CEYP studying at HE level in colleges, which was 9.7% in 2017 [Scottish Funding Council (SFC), 2018]. Thus, evaluation of educational achievement requires a longer and more joined up consideration.

Care-related factors such as stigma, multiple transitions and chaotic living arrangements cause insecurity contributing to negative educational experiences (O’Higgins et al., 2017) and are likely to impact CEYP educational outcomes when accompanied by risk factors such as unmet ASN and low self-efficacy (O’Higgins et al., 2015). Stability in relation to accommodation and schooling are predictors of academic achievement in post-compulsory education (Höjer and Johansson, 2013., Gypen et al., 2017). CEYP are likely to have experienced inconsistent relationships and insecure attachments (Drew and Banerjee, 2019) emphasizing the need for safe and trusting educational environments that CEYP regard as highly important for their learning (Sugden, 2013). The Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 defines corporate parenting as “the formal and local partnerships between all services responsible for working together to meet the needs of looked after children, young people and care leavers.” Students experiencing successful transitions into HE and FE emphasized how FE establishments retain an important role as corporate parents holding high expectations for them (O’Higgins et al., 2017). Therefore, it is crucial carers and educational professionals have knowledge on how to best support CEYP through transition. Mentoring relationship may improve CEYP transitions (Gypen et al., 2017) and are valued by CEYP, noting these qualities are transferable to other corporate parenting roles (Thompson et al., 2016).

Within FE the engagement and implementation of support requires careful management. McClung and Gayle (2010) reported a range of CEYP experience, ranging from positive reports of teachers encouraging aspirations as well as many participants reported differential treatment tied to care status leading to low teacher expectations. Mannay et al. (2017) argue young people labeled as “in care” perceive themselves at risk of being associated with connotations of “failure” by their teachers. Such unsupportive, stigmatizing practices can undermine CEYP’s educational expectations, potentially leading to a form of the self-fulling prophecy (Rosenthal and Jacobson, 1968). However, CEYP can be motivated to achieve academically to prove those with low expectations for them wrong (Brady and Gilligan, 2018). Practical approaches can also undermine support systems in place. CEYP’s care status may be inadvertently communicated when support meetings are scheduled during class time. One third of 80 CEYP aged 8–18 had been bullied because they were not living with their parents (Farmer et al., 2013). Many reported they were reticent to share their circumstances with others, being apprehensive about the response from their peers.

It is arguable that adverse experiences impact CEYP subjectively (Hallett, 2016), thus CEYP require individualized support that is often steered by the individual’s efforts (Grunwald and Thiersch, 2009). Maintaining relationships with carers and engagement with extra-curricular activities positively impacted educational outcomes (Refaeli et al., 2017). However, CEYP often experience barriers to involvement with extra-curricular activities tied to self-efficacy and instability of their social environment (Quarmby et al., 2019; Mannay et al., 2021). Ellis and Johnston’s Pathways to University Project (2020) highlights the significant impact of the absence of long term, lasting support from previous carers and education professionals, on CEYP’s perceived success at university.

Resilience is evidenced to be the most important factor in supporting CEYP cope with adversity (Shonokoff et al., 2015). Resilience is a process wherein individuals exhibit positive adaption, despite experience of significant trauma or adversity (Luthar et al., 2000). The most common factor in supporting children develop resilience is a stable relationship with a significant adult. For CEYP their perception regarding their connection with others may relate to their ability to be self-determined that supports them to engage in goal-directed behaviors and determine their own outcomes (Deci et al., 1991) and this forms the theoretical framework that underpins the study being reported. An individual’s environment may promote or limit the extent to which psychological needs are met, thus impacting their ability to be self-determined. Feelings of competence, relatedness and autonomy are three key factors influencing resilience development (Ryan and Deci, 2000). Relatedness, referring to feeling connected with others through consistent and personal relationships, is the most salient factor of self-determination, in helping individuals aged 16–19 pursue positive post-school destinations (Hyde and Atkinson, 2019). Stein (2008) argues continuity is a key tenet of resilience but claims educational discontinuities can be helpful for CEYP when they are involved in planning a more suitable pathway, helping them develop a sense of agency. However, Yates and Grey (2012) highlighted that CEYP may be resilient in one domain but not another, emphasizing the heterogeneity of CEYP adaptive outcomes. Therefore, this study aimed to explore CEYP’s agency in both the continuity and discontinuity of their educational pathways in FE and identify the commonalities and diversity of their experiences.

Accordingly, a socio-constructivist approach supports gaining an understanding from CEYP that reflects their experiences and reality. Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) Ecological Systems Theory considers the interrelatedness of individuals in a developmental context. It is understood people engage in an ongoing, dynamic process wherein they develop their perceived reality, based on their own experiences and interpretations of the environment. By centralizing the CEYP voice power imbalances between CEYP and the interviewer are reduced by foregrounding participants as experts of their own experiences (Davidson, 2017). Such an approach aligns with the Scottish Government’s Progressing the Human Rights of Children Action Plan (2018b) that promotes young people’s involvement in making decisions on issues affecting them. Few studies have explored the FE experiences of CEYP and most research is concerned with schooling up to aged 16. The research being reported addresses this gap and explores CEYP’s experience of barriers and facilitators to achievement, reasons for dropout and improvements to support CEYP in their attainment and FE experience.

Design

This study placed young people’s views at its center and explored CEYP educational experiences. Placing value on participant’s views adopts a subjective stance that enables an understanding of educational needs to be captured and encourages the influence of this participant group in FE provision (Cresswell, 2007). Semi-structured interviews can achieve a rich understanding of participants experiences (Greig et al., 2013) and given the topic of enquiry are more suitable than alternatives such as focus groups, as sharing care experience with a group could be difficult for some CEYP (Bell and Waters, 2014). The interview schedule incorporated pre-planned items and used prompts when necessary and supports CEYP to highlight themes that were not pre-empted and were considered as relevant to their experiences. Themes captured in the schedule included items guided by the research questions and covered care background/experience, motivation and attitude toward learning, FE expectations and expectations of oneself, FE learning experience capturing strengths and difficulties, significant relationships, future prospects and suggestions of improvement for CEYP in FE. During interviews phrasing of questions were tailored to match participant discourse, as it is suggested matching the participant’s manner helps to build rapport (Alderson and Morrow, 2011).

Participants

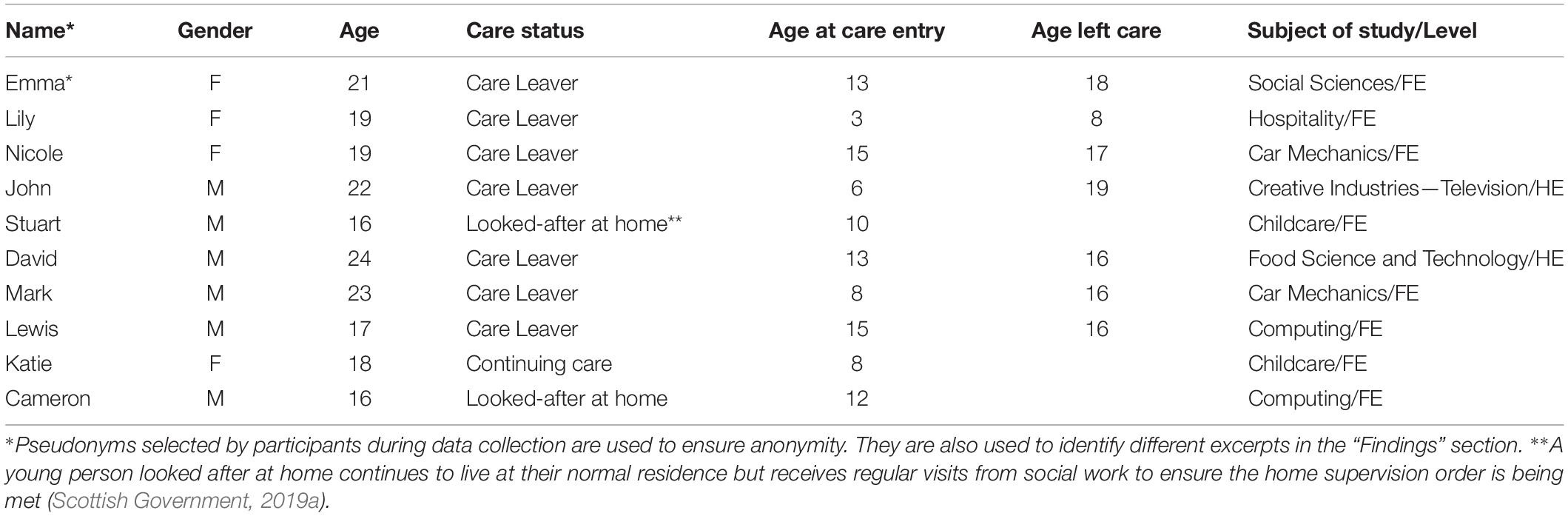

Specific eligibility criteria targeted duration and recency of CE, in addition to exclusion criteria making participants with a previous relationship to the first author, who was formally an FE lecturer in a participating college, ineligible to avoid conflict of interest. A minimum of 1 year in care and an age range of 16–25 years were established. Such criteria ensure sufficient CE was accessible to participants, to support their self-report accounts (Lipkin, 2016). According to the Children and Families Act (Scottish Parliament, 2014) every CEYP is entitled to corporate parenting support until they are 26, therefore the age criteria allowed for assessment of corporate parenting support in FE. Participants provided a self-report of their CE status and age. This approach bypasses alternatives such as accessing student records that may be seen a violation to this already vulnerable group. Care experienced and care leavers were invited to take part. A maximum variation strategy was adopted where each of the 26 colleges across 13 Scottish regions were offered a description of the research. Seven colleges from geographically diverse regions expressed interest and advertised the study via posters on campus and college social media, email and online learning platforms. Previous research noted challenges associated with accessing CEYP for research (Mezey et al., 2015). Therefore a small sample size was expected while the sampling strategy encouraged heterogeneity. 17 CEYP students volunteered, of whom six were unable attend the interview as arranged and one participant did not fit the age criteria. This led to ten interviews being conducted that correspond with criteria for exploratory research ranging between 5 and 15 participants (Emmel, 2013). Participant descriptors are detailed in Table 1.

All 10 participants were White, nine identified as Scottish and one identified as English. Seven were care leavers and three were currently in care. Of the care leavers, three had been in residential care,3 two had been in foster care, one in kinship care and one looked after at home.

Procedure

A choice of interview location encouraged participants to feel comfortable enabling the interview to best reflect their experiences (Alderson and Morrow, 2011). Eight interviews were held within a private room at the CEYP’s college and telephone interviews were chosen by two CEYP. Interviews ranged between 20 and 60 min and were all conducted by the first author. The interviews were transcribed verbatim, by the first author, to represent participants’ dialect and use of language. In person interviews used paper materials and digital documents were shared with telephone interviewees.

The sensitive nature of this study and use of a CEYP sample, required use of responsible and ethical research practice by adhering to guidelines (British Psychological Society, 2006; Data Protection Act, 2018). University ethical approval, as well as stakeholder permissions from each FE college was achieved. Informed consent was established through the distribution of an information sheet and consent form that explained their right to withdraw and shared information about confidentiality, anonymity and data storage procedures. Masson (2002) highlights that young people often have difficulty withdrawing from activities organized by adults. Information regarding withdrawal was provided during briefing and debriefing. Participants were informed should they disclose information relating to a safeguarding issue, the researcher would have a duty to act. CEYP were provided with contact information should they want to revisit interview content with the research team. Ample time for post-interview debrief ensured concerns or questions were addressed and relevant support agencies shared as avenues for further support.

Analytical Strategy

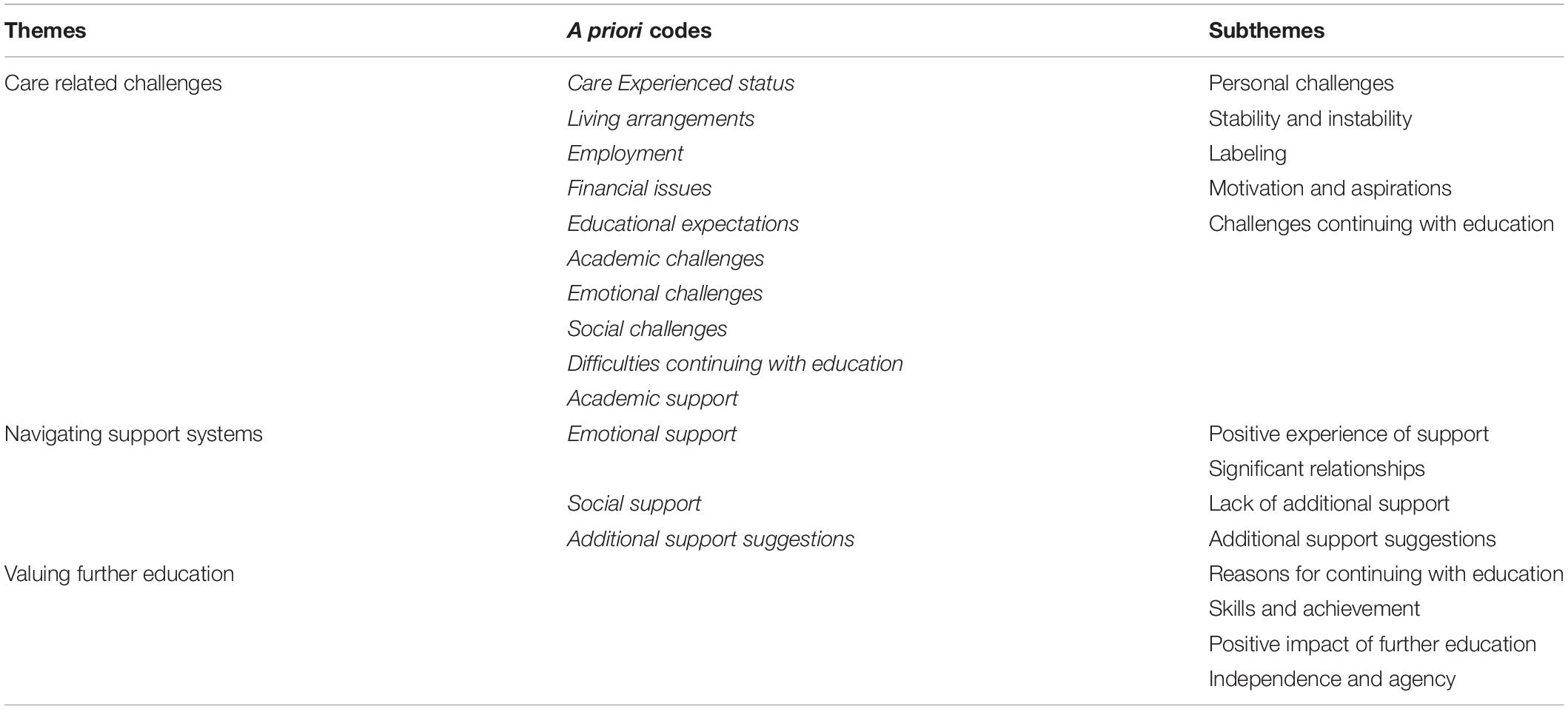

When working with CEYP it is imperative to consider potential differences between their views and experiences and the factors that may impact on data interpretation. Thematic analysis supports detailed interpretation of repeated themes across participants (Braun and Clarke, 2006) and allows for findings to be clearly communicated to others, meeting an end goal of this research (Clarke and Braun, 2013). The hybrid approach was adopted allowing for unexpected themes to be identified that can merge with existing themes informed by previous research (Swain, 2018). Nine a priori codes were identified and related to interview questions, these included: care status, living arrangements, employment, financial issues, academic challenges, academic support, emotional challenges, emotional support, social challenges, social support, educational expectations, difficulties continuing with education and suggestions for support improvement. Forty six a posteriori codes were generated meaning most codes were created by participants, meeting the research aim of giving voice to CEYP (Swain, 2018). The analytical process followed the six phases as set out by Braun and Clarke (2006) and further detail is captured in the Supplementary Material.

Findings

Three main themes were identified across the interviews. As shown in Table 2, there was a hybrid development of themes and codes. Content in italics refers to a priori content and adaptations trace across themes to help summarize the process. Themes and corresponding subthemes are provided in Table 2 and are explored using illustrative excerpts, these are reported verbatim and noted added to excerpts within parentheses if colloquial speech was used by an individual.

Care Experience and Personal Narratives

Most CEYP had significant personal challenges that altered their perceptions toward and ability to cope with FE. Despite this, CEYP presented positive attitudes regarding FE where negative attitudes were seemingly fuelled by undesirable experiences. Most challenges were care-related and for those not specifically care-related, an individual’s care status was often a compounding influence as social and emotional personal challenges were connected:

“I just feel rubbish one day and fine the next. But I come in anyway. I just dinnae (do not) talk to anyone when I’m in one of ma moods. I canna be bothered, so I just sit and dinnae dae (do not do) much. It’s just my mental state of mind probably” Nicole

Most CEYP were unsure whether they had disclosed their care status in their college funding application and for those who had, they had feelings of anxiety and uncertainty toward to process.

“It asks you if you’re Care Experienced… I didn’t really know what would happen with that, so I just ticked it… I was nervous about it” Katie

Care-related barriers were linked to individuals ability to attend college. CEYP considered review meetings during class time as disruptive to their learning and their relationships with lecturers and they were left to balance out competing interests:

“…the college don’t like when you’re not in. I have quite a lot of review meetings… It’s the people doing the meetings who start getting annoyed so there’s got to be a compromise but that’s left in my hands and no one is willing to budge” Lewis

CEYP explained their experiences of stability and instability in care and education and how this impacted their attainment. Participants referred to change in living arrangements and absence from school created barriers to educational engagement. CEYP viewed care-related disruption as a reason for their limited achievement in school, which led to progression that did not adequate reflect their ability.

“I ended up missing about 6 months of school. I was doing higher courses before I left and had to drop down to National 5 s. That’s quite a dramatic drop going from something that could’ve got me into a 3rd level college course” Lewis

Most CEYP preferred FE to school, particularly if care-related difficulties had posed a challenge in continuing with education. The impact on the perceived availability of creating and maintain friendships with peers was referred to. Katie comments on consistency in her experiences within FE. John refers to challenges tied to establishing friendships, perceived lack of warmth and consequence school avoidance and withdrawal.

“I’ve been to so many different care homes… With my education I’ve moved about but college has been stable, staying here has made a difference” Katie

“my classmates weren’t that friendly. I’d dropped out of college by November” John

Some CEYP felt their lack of motivation and stated low teacher expectations influenced their FE engagement. Nicole’s excerpt illustrates her experience that led to FE withdrawal on two previous occasions.

“I never had a good relationship with any of my lecturers then. Both times I was only there about 3 months…” Nicole

Many CEYP described situations where labeling by peers and professionals created perceptions of stigma and contribution to isolation. CEYP rejected the notion that all CEYP are the same and emphasized their need to be viewed as capable individuals, particularly by teachers:

“They’ve just got that set mentality against us and just generalise Care Experienced people as one thing” Lewis

“Lecturers would talk to me a bit different … I’d just be looking at them like I’m no (not) stupid” Nicole

Others emphasised a lack of stigma and felt supported “I haven’t been treated differently from the other people in the college. We are all treated the same as individuals, it’s really good” Stuart

Most CEYP had experienced care-related bullying. “I got bullied at school for being in care… if I was away to a LAC4 review people would ask me and laugh at me. I’ve got bullied once in college, but they have dealt with it really well…” Katie

Some struggled to engage with learning or felt they had to withdraw from education. There was a consensus that labeling was worse in school than FE. Evident in all CEYP accounts was the motivation to succeed in FE, with many referring to aspirations for progression and employment.

“Just keeping ma mind (my mind) on track and trying to work as hard as I can.” Cameron

Some CEYP referred to external supporting factors, such as family and significant others promoting their aspirations, whereas others referred to their desire to prove those who doubted them wrong.

“…my specific motivation is to better myself and to learn but… I am at the college for my two sons’ sake. I wouldn’t be doing it if it wasn’t for them…” Mark

“Social services said I would never be in mainstream education … yet here I am. I would say there’s no better feeling of proving the experts wrong…” John

Most CEYP referred to their reliance on the bursary to maintain their attendance at college. Many highlighted they would be unable to attend college without it. Some CEYP emphasized that financial support, coupled with support from lecturers, provided them with the motivation to achieve.

“Really the motivation is the bursary. I don’t know where I would really be right now without that money…” Lewis

CEYP shared the aspiration to support future generations of CEYP. Many felt with the skills they gained at college, they could improve other CEYPs’ outcomes, indicating CEYP identified this sense of purpose as motivation.

“I’ve been through foster care so I think I could make a difference wi’ kids (with kids) in childcare cos in normal childcare there could be people in foster care… Somebody to talk to that’s been through care could help” Stuart

Valuing Further Education

Appreciation of FE was universally expressed by participants. Participants identified specific aspects of FE that enabled their success including new skill development, improved wellbeing and a sense of independence, achievement and belonging. Some emphasized without FE they would have poorer qualifications and lessened future outcomes. CEYP spoke enthusiastically about FE opportunities and emphasized the relevance of work experience. Excerpts from CEYP completing supported programs that specifically designed to support learners with ASN or those who have disengaged with school clearly identify such perceptions:

“I’m doing a work experience in Game getting to like learn more about… behind the scenes of your computer and how you would fix them” Cameron

Participants expressed feelings of accomplishment about completing their course thus far. Many CEYP had exceeded their own and others expectations of themselves.

“I’ve passed all my outcomes for both first and majority of second year… I’m going to uni next year. Not many people I know from care have done what I’ve done…” John

All CEYP commented on the positive impact that FE provided, creating a sense of belonging and improved wellbeing. For some, relationships with peers and staff at the college provided consistency and connection.

“I’ve enjoyed learning. The more challenging stuff keeps you thinking a wee bit more, it can definitely raise your spirits when you get it…” David

“I’ve made some friends… I’ve felt more comfortable in this place than I have before” John

CEYP valued being treated as adults and the independence they had in determining their FE pathway. Some felt lecturers had facilitated this sense of agency, which supported their FE success.

“They treat you as adults and not like boss you about so much like they did in school…” Cameron

Navigating Support Systems

CEYP shared positive and negative experiences when navigating support systems. Positive experiences included support with learning, finances and progression to employment. Evident in most accounts was the need for improved quality of support and improved availability in colleges. All CEYP valued professionals’ understanding their needs and reported positive support from FE staff. CEYP felt they would have difficulty achieving without specific support:

“I get a lot of help from lecturers… with writing tasks and my reading. She helps me if I’m upset or if I’m not concentrating…” Lily

Some CEYP referred to positive support experiences involving non-teaching staff, such as student support advisors and third sector advocacy workers. Many valued the relational quality of these services, implicating that accessing such support provided a sense of security crucial to their FE success.

“They helped with the bursary form and with questions about being in care. There’s a fine line between professional and being friends and they ride that line perfectly…” Mark

CEYP felt positive relationships with significant adults supported their educational attainment and were aware of lecturers’ efforts to facilitate their integration into FE and reported this to be useful in supporting their progression, especially for those who had long-term school absences.

“When the lecturers first get to ken you… (know you…) they start to notice when you’re being off. They just take you aside and let you ken (know) that if you need to speak that they’re there…” Nicole

A prominent pattern was CEYP highlighting the importance of positive peer relationships. Some stated friendships provided crucial support that was otherwise absent.

“If you are care experienced you need that… support figure. You know even from a friend because you may not have it from anywhere else” Mark

Some participants who had experienced support from a staff member with CE, voiced this benefitted their wellbeing and educational progress.

“she’s Care Experienced too. I would just come into college and see her just to say hi and chat and it just makes it feel so much better” Katie

However, the view that teaching staff had limited understanding of CEYP needs was not isolated. Katie described the need for training by detailing the lack of lecturer knowledge:

“Most people had heard of it but there was a couple of people that shocked me. They were saying “what is a corporate parent?” and I was like “you are a corporate parent”” Katie

Permeating many accounts was the lack of support for additional needs provided at their colleges. Many CEYP had difficulties engaging with FE linked to their ASN and some required further support to overcome this. Some recognized their difficulties and self-referred to support service, as per college policy but were deemed ineligible for such support.

“I just put down Care Experienced but I spoke to student support and he basically told me ‘we don’t really have any support to help with that”’ Lewis

Some CEYP considered their ASN to be care-related, referring to social and emotional needs, and for others it was not relevant. Across both groups, concerns regarding support were evident:

“That only really lasted in the beginning… I don’t get that now, which has made it very difficult this year” David

A recurring view was the lack of CE specific support in some colleges. Many recognized their difficulties stemmed from their CE and believed that merited additional social and emotional support.

“I think being in care took away a lot of my social skills… I’m second oldest in my college class but a lot of them are further ahead in life… I never got any specialised help being a care-experienced… Maybe things would a bit different if I had…” Mark

An interesting insight was some CEYP’s resistance to support. They believed that professionals’ efforts to help were not genuine and this perceived lack of compassion is troubling given the already vulnerable population. These CEYP exhibited a sense of self-reliance, indicating a perceived barrier to engagement with support. It is not clear whether such support was rejected through a perceived lack of compassion or perhaps whether support was viewed as being inadequate for other reasons.

“I dinnae like (do not like) speaking about my feelings. It’s personal with me… Naebody (No one) is interested in listening to what I need to speak about” Nicole

Most participants called for improved ASN provision, signposting of support and staff knowledge. Many felt improved learning support would benefit their FE attainment and help contribute to feeling comfortable in an FE environment. Some participants felt CEYP should automatically be considered for additional support on the basis it was personalized support.

“they could just get extra support sessions. Seeing where their ability is at, especially if they have missed out on education… It should be designed for what a person needs.” Lewis

Many participants gave suggestions of peer support and noted interest in supporting other CEYP demonstrating the community CEYP are keen to maintain. “Like a Care Leaver support group for and run by Care Leavers” John. Katie spoke of her experience as a CE Officer and working with Advocacy Worker, highlighting the success of opportunity in encouraging CEYP to seek support.

“We came forward as Care Experienced and people in my class have come to me just for advice, telling me that they’re Care Experienced…” Katie

CEYP were enthusiastic about addressing these concerns by providing suggestions for improving understanding among professionals and their peers to combat stigma. Suggestions ranged from professional development to peer education.

“Children believe that kids are in care because they have done something wrong. There should be something taught about people in care, like they are just the same. There still is a stigma about Care Experienced people. Not as much as what there was but there still is” Katie

“Have like a course where somebody who’s been in care comes in… teaches lecturers aboot (about) it so they can relate tae it mare (relate to it more)” Stuart

Discussion

This study considered CEYP experiences of FE. Participants highlighted supportive factors including access to support and development of independence, self-determination and educational aspirations in promoting their engagement with FE. Barriers to FE attainment included personal and care-related challenges, FE staff varying knowledge, limited access to ASN provision, instability in schooling and accommodation throughout educational pathways and care-related stigma. Finally, there was a prominent call for improved additional support provision for CEYP, which was identified as an area for potentially improving future CEYP engagement and attainment. Autonomy, competence and relatedness, the three innate needs identified by Self Determination Theory (Deci et al., 1991) were central aspects influencing all themes. Such needs were met through positive relationships with FE staff and peers, which CEYP stated as an important factor influencing their FE experience and longer-term prospects.

Opportunities for Care Experienced Young People Achievement in Further Education

CEYP narratives highlighted numerous opportunities promoting their FE attainment. Evident in CEYPs’ accounts was the value placed on FE. Participants’ expressed motivation to overcome personal challenges and succeed and was this regarded as a direct influence on attainment, supporting Self Determination Theory evidence (Deci et al., 1991). CEYP said that having significant relationships promoted their resilience, adding to evidence regarding relationships in supporting CEYP pursuit of post-school goals (Hyde and Atkinson, 2019). Perceived doubt in CEYP’s aspirations motivated some to achieve, supporting findings of CEYP rejecting assumptions that they lack aspiration (Mannay et al., 2017). Achievement opportunities facilitated a sense of pride and promoted CEYP attainment. Many felt being treated as adults by lecturers, facilitated agency in determining their educational outcomes. This supports evidence that treating CEYP as agents of their own life course promotes their educational success (Hass et al., 2014).

Most participants expressed aspiration to improve CEYP outcomes using skills gained from FE and acknowledges that roles assumed by CEYP contribute to enhanced self-efficacy and social connectedness (Melkman et al., 2015). Another factor was the stability FE contributed to CEYP’s lives. Many felt the improved structure, continuity and financial support, compared to their schooling, had facilitated their success. Thus, supporting findings that discontinuity can have a positive impact CEYP’s educational pathways (Stein, 2008).

CEYP were completing work experience opportunities through college. Like Melkman et al.’s (2015) findings, this provided motivation to complete their qualification. Three CEYP on supported programs, designed to support disengaged school leavers and learners with ASN, felt they would not have accessed such opportunities at school. These work experience opportunities had allowed CEYP to develop relationships that provided a sense of security and such relationships have been reflected elsewhere as facilitating attainment (Sugden, 2013). Friendships established in educational settings also contribute to CEYP continuing with education (Lipkin, 2016) and in this study peer relationships were regarded as important for accessing emotional support that in turn facilitated engagement with FE. Extra-curricular activities were emphasized as opportunities for learning and friendships and involvement in mutual activities with peers is likely to support social and cognitive development (Daniel et al., 1999). Thus, FE should promote extra-curricular activities particularly for CEYP who are less likely to have had these opportunities (O’Donnell et al., 2019).

Consistent with previous findings all participants placed importance on relationships with FE staff for promoting their aspirations, attainment and self-efficacy (O’Higgins et al., 2017) and recognized lecturers understanding their needs as key to quality support (Drew and Banerjee, 2019). An interesting insight was the positive support experiences CEYP reported when their relationships with staff involved those who identified as CE. This implicates disclosure of care status by FE professionals may support CEYP in accessing support in FE. Conversely, many CEYP felt FE staff lacked knowledge of CEYP needs and considered this was communicated through stigmatizing behavior or lack of understanding for care-related disruptions to their education, building on previous reports of limited teacher understanding of CEYP needs leading to stigmatizing behavior (Mannay et al., 2015). Thus, the environmental interactions and make up of relationships in FE are valuable considerations when evaluating CEYP perspectives regarding attainment and encourage a layered consideration (such as Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) when capturing such interaction.

Barriers to Care Experienced Young People Achievement in Further Education

All CEYP reflected several barriers to their achievement in FE. While these challenges were not solely care-related, many referenced their CE as a compounding influence on their personal challenges, which is consistent with previous research (Brady and Gilligan, 2018). Some highlighted mental health difficulties had impacted their FE engagement, while others detailed their challenges socializing with peers. Health difficulties had disrupted some CEYP’s attendance leading to a reduced educational experience overall. While some CEYP felt supported by lecturers, others stated there was limited support from FE staff. These findings support evidence of poor rates of CEYP health and wellbeing (McAuley and Davis, 2009) and the need for improved mental health support within post-compulsory education for CEYP (Ellis and Johnston, 2020), implicating that FE colleges should be equipped to support CEYP health needs.

Related to Ferguson and Wolkow’s (2012) findings, barriers to continuing with education were frequent accommodation and school moves. Such change led to considerable absence with some CEYP stating this amounted to years of education. Absence had impacted CEYP’s core skill development leading them to struggle with aspects of FE. Similarly to Driscoll (2013), some attributed this instability as the reason for poor school achievement and consequent post-school progression that was beneath their capability. Professionals should understand that CEYP may require ASN provision due to missed schooling.

The disclosing of care status was noted across FE experience. Tied to staff knowledge some CEYP expressed reluctance to disclose their care status during their college application. Supporting previous findings, interview dialogue indicated a lack of CEYP understanding about the implications of disclosing their care status (Hyde-Dryden, 2013). Therefore, CEYP need to be informed as to who has access to their information. CEYP felt others perceived negative connotations of their CE label, supporting earlier reports (Mannay et al., 2017). Consequently relationships with staff were variable and such inferred bias may act as a barrier to the formation of trusting relationships with educators known to support CEYP educational attainment (Sugden, 2013). Such labeling practices can be addressed through training which could enable more positive FE journeys for CEYP. Overall, these findings support previous evidence that improved understanding of factors influencing disruption to CEYP’s education are necessary (O’Neill et al., 2019). Tied to student awareness, many CEYP had been bullied due to their care status, supporting findings of high rates of care-related bullying in education (Farmer et al., 2013) and the continuing need to challenge negative stereotypes (Hare and Bullock, 2006). Some reported bullying as the reason for their difficulties continuing with education, giving insight into FE drop out figures (Scottish Government, 2018). Colleges are opportunely positioned to promote aspirations for CEYP previously feeling unsupported in education.

Additional Support Needs and Care Experienced Young People Further Education Experiences

Many CEYP reported struggling to engage with FE because of their ASN covering mental health difficulties and learning difficulties. In most cases, these needs were perceived as not being met, implicating challenges in accessing ASN provision in FE. Although the success of CEYP progressing to FE should be celebrated, their continuity of needs cannot be overlooked (Brady and Gilligan, 2018). CEYP are classed as having ASN (Scottish Government, 2017), however, the findings of this study suggest colleges must do more to guarantee CEYP support. Aligned with the Education (ASL) (Scotland) Act (2004), most CEYP felt, based on their care-status, they should be entitled to ASN provision should they require it. However, some struggled to access support on this basis and called for improved needs assessment. CEYP receiving personalized support from a staff mentor reported greater confidence in their FE progression (O’Neill et al., 2019). This indicates that colleges should ensure CEYP have a staff member, who can establish a trusting relationship with them and offer individualized guidance and encouragement. Findings relating to peer support schemes (Scottish Government, 2012) as well as targeted interventions (MacRitchie, 2019) reflect how CEYP were able to effectively support each other socially as well as improve positive post-school destinations for 86% of participating CEYP (MacRitchie, 2019). Such interventions require further investigation and may be of value for CEYP who feel disenfranchised based on the perception that no professional truly wants to help them. While self-reliance can be a positive attribute (Samuels and Pryce, 2008) it may undermine CEYP attainment, as CEYP are less likely to seek support than their peers (Cotton et al., 2014). This recommendation denotes the important role held by corporate parents for CEYPs’ educational careers.

Looking Ahead and Future Research

The purpose of this project was to provide an in-depth insight into CEYP experiences in FE. Participants were able to report their experiences, documenting barriers and identifying potential reasons for their previous difficulties continuing with education. In line with such expectations are the sampling strategies that were adopted. Certain CEYP may have been less confident and felt restricted in their capacity to voice their views, while others had previous experience with research interviews that enabled them to provide more descriptive data. However, participants with ASN were able to provide insight into their FE experience based on the researcher-participant rapport that was developed (Charmaz and Belgrave, 2012) leading to informative findings from all participants. Given the dearth of research on CEYP in FE, there is room for future studies to build on these findings, focusing on different qualifications and subject areas; as well as communicating and engaging with CEYP over a longer period allowing nuances tied to care experiences (such as the transition of care entry and exit) to be captured. The sample represented seven colleges from geographically diverse Scottish regions and included CEYP studying a range of different courses. We recognize CEYP views at other colleges may have been different, as participants were all White British CEYP, meaning there was a lack of representation of ethnic minorities. CEYP were approached near the end of academic year, allowing reflection on the past year to be shared in interviews. However, this may have influenced participants’ decision to participate, potentially meaning students with superior time-management or whose study involved fewer exams were inclined to volunteer. The sample arguably had a positive FE experience considering they had nearly completed their qualification. Areas ripe for additional consideration are CEYP skills as they effectively have to become their own advocate, accommodating both their developing self and recognizing the need to negotiate with external organizations and navigate complex support structures to sustain and optimize their potential despite their adverse and changeable environment. The system currently in place tacitly acknowledges this via the role of corporate parents. Further study on corporate parenting and CEYP acting as self-advocates is warranted.

Conclusion

These findings provide unique insight into CEYP experiences of FE. Perceived barriers and opportunities for CEYP attainment in FE and CEYP suggestions for how FE support systems could be developed to facilitate their attainment are explored. Such insights from CEYP offers a contribution to a literature where much research is needed. CEYP highlighted facilitators of their achievement including, stability of education and accommodation, personalized and financial support, professionals understanding their needs, self-determination, aspiration and motivation, supportive relationships and opportunities provided by FE. Barriers to CEYP’s FE achievement included, labeling and stigmatized views of CEYP, bullying, poor mental and physical health, care-related challenges, ASN and lack of ASN provision. Regarding FE support services, most CEYP highlighted a need for improved provision of personalized support. Participants provided numerous recommendations for support in FE, which they suggested could help to address the barriers they face and are summarized in the supporting information. CEYP valued the achievement opportunities FE provided, with most reporting feeling accomplished and optimistic about the future, indicating the value FE has for CEYPs’ educational progression. Central to this study is the CEYP voice that shared positive and negative influences on their FE experience. These findings indicate the need for research with a more diverse sample and further exploration of the design and implementation of CEYP informed support in FE.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because participants did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University of Manchester Ethics Committee. Written informed consent from the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2022.821783/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

- ^ These include Higher National courses at SCQF 7 and 8, equivalent to International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) 5 and Regulated Qualifications Level (RQL) 4 and 5 in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

- ^ SCQF level 5 is equivalent to ISCED 3 and RQL Level 2 in England, Wales and Northern Ireland which includes GCSE grades 4–9.

- ^ The label “looked after child” may be appropriate for children in residential care (typically adolescence living with similarly aged children away from home), foster care (approved families or persons act as a temporary or short-medium term home for a child) and kindship care (families or persons related to a child providing a home). These descriptions are based on those provided by the Scottish Government (2019a).

- ^ Looked after child (LAC) review is a regular meeting between those closely concerned with a child or young person who is looked after by the local authority. The meeting is held to review the care arrangements for the child and consider whether changes need to be made to how they are being looked after. Under Section 31 of The Children (Scotland) Act (1995), a review must be held when children are looked after by the local authority.

References

Alderson, P., and Morrow, V. (2011). Information. The Ethics of Research with Children and Young People: A Practical Handbook. London: SAGE Publications, 85–98.

Allen, B., and Vacca, J. S. (2010). Frequent moving has a negative affect on the school achievement of foster children makes the case for reform. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 32, 829–832. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.02.001

Bell, J., and Waters, S. (2014). Planning and Conducting Interviews Doing Your Research Project: A Guide for First-Time Researchers. London: McGraw Hill Education, 209–226.

Brady, E., and Gilligan, R. (2018). Supporting the educational progress of children and young people in foster care: challenges and opportunities. Foster 5, 29–41.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualit. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

British Psychological Society (2006). Code of Ethics and Conduct. Leicester: The British Psychological Society.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). Understanding Children in Context: The Ecological Model of Human Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1–8.

Charmaz, K., and Belgrave, L. L. (2012). “Qualitative interviewing and grounded theory analysis,” in The SAGE Handbook of Interview Research: The Complexity of the Craft, eds J. F. Gubrium, J. A. Holstein, A. B. Marvasti, and K. D. McKinney (London: Sage Publications), 367–380. doi: 10.4135/9781452218403.n25

Clarke, V., and Braun, V. (2013). Teaching thematic analysis: over- coming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. Psychologist 26, 120–123.

Cotton, D. R. E., Nash, P., and Kneale, P. E. (2014). The experience of care leavers in UK higher education. Widening Participat. Lifelong Learn. 16, 5–21. doi: 10.5456/wpll.16.3.5

Cresswell, J. W. (2007). “Standards of validation and evaluation,” in Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 2nd Edn, eds J. W. Creswell and C. N. Poth (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications), 79–82.

Daniel, B., Wassell, S., and Gilligan, R. (1999). ‘It’s just common sense isn’t it?’: Exploring ways of putting the theory of resilience into action. Adoption Fost. 23, 6–15. doi: 10.1177/030857599902300303

Data Protection Act (2018). Data Protection Act 2018. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/data-protection-act-2018 (accessed June 27, 2019).

Davidson, E. (2017). Saying it like it is? Power, participation and research involving young people. Soc. Inclusion 5, 228–239. doi: 10.17645/si.v5i3.967

Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Vallerand, R. J., and Pelletier, L. G. (1991). Motivation and education: the self-determination perspective. Educ. Psychol. 26, 325–346. doi: 10.1080/00461520.1991.9653137

Drew, H., and Banerjee, R. (2019). Supporting the education and well-being of children who are looked-after: what is the role of the virtual school? Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 34, 101–121. doi: 10.1007/s10212-018-0374-0

Driscoll, J. (2013). Supporting care leavers to fulfil their educational aspirations: resilience, relationships and resistance to help. Child. Soc. 27, 139–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1099-0860.2011.00388.x

Duncalf, Z. (2010). Listen Up! AdultCare Leavers Speak Out: The Views of 310 Care Leavers Aged Manchester: The Care Leavers’ Association, 17–78.

Education (ASL) (Scotland) Act (2004). Education (Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Act 2004, c.6. Available online at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2004/4/contents (accessed June 29, 2019).

Ellis, K., and Johnston, C. (2020). Pathways to University-The Journey Through Care: Findings Report two. Sheffield: The University of Sheffield. doi: 10.15131/shef.data.13247639.v3

Emmel, N. (2013). Sampling and Choosing Cases in Qualitative Research: A Realist Approach. London: SAGE Publications, 137–156. doi: 10.4135/9781473913882

Farmer, E., Selwyn, J., and Meakings, S. (2013). ‘Other children say you’re not normal because you don’t live with your parents’. children’s views of living with informal kinship carers: social networks, stigma and attachment to carers. Child Family Soc. Work 18, 25–34. doi: 10.1111/cfs.12030

Ferguson, H. B., and Wolkow, K. (2012). Educating children and youth in care: a review of barriers to school progress and strategies for change. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 34, 1143–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.01.034

Geiger, J. M., and Beltran, S. J. (2017). Readiness, access, preparation, and support for foster care alumni in higher education: a review of the literature. J. Public Child Welfare 11, 487–515. doi: 10.1080/15548732.2017.1354795

Greig, A., Taylor, J., and MacKay, T. (2013). “Designing and doing qualitative research children and young people,” in Doing Research with Children: A Practical Guide, (London: Sage Publications), 171–202. doi: 10.4135/9781526402219

Grunwald, K., and Thiersch, H. (2009). The concept of the ‘lifeworld orientation’ for social work and social care. J. Soc. Work Practice 23, 131–146. doi: 10.1080/02650530902923643

Gypen, L., Vanderfaeillie, J., De Maeyer, S., Belenger, L., and Van Holen, F. (2017). Outcomes of children who grew up in foster care: systematic-review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 76, 74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.02.035

Hallett, S. (2016). ‘An uncomfortable comfortableness’: ‘Care’, child protection and child sexual exploitation. Br. J. Soc. Work 46, 2137–2152. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcv136

Hare, A. D., and Bullock, R. (2006). Dispelling misconceptions about looked after children. Adopt. Fost. 30, 26–35. doi: 10.1177/030857590603000405

Hass, M., Allen, Q., and Amoah, M. (2014). Turning points and resilience of academically successful foster youth. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 44, 387–392. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.07.008

Herd, R., and Legge, T. (2017). The education of looked after children: the social implications of further education. Adopt. Fost. 41, 67–74. doi: 10.1177/0308575916681712

Höjer, I., and Johansson, H. (2013). School as an opportunity and resilience factor for young people placed in care. Eur. J. Soc. Work 16, 22–36. doi: 10.1080/13691457.2012.722984

Hyde, R., and Atkinson, C. (2019). Care leavers’ priorities and the corporate parent role: a self-determination theory perspective. Educ. Child Psychol. 36:41.

Hyde-Dryden, G. (2013). Overcoming by Degrees: Exploring Care Leavers’ Experiences of Higher Education In England Ph. D, Thesis.

Independent Care Review (2019). Independent Care Review: Delivering real change. Availble online at: https://www.carereview.scot/ (accessed May 28, 2019).

Kelly, B., McShane, T., Davidson, G., Pinkerton, J., Gilligan, E., and Webb, P. (2016). Transitions and Outcomes for Care Leavers With Mental Health and/or Intellectual Disabilities: Final Report. Belfast: QUB.

Lamont, E., Harland, J., Atkinson, M., and White, R. (2009). Provision of Mental Health Services for Care Leavers: Transition to Adult Services. LGA Research Report. Slough: National Foundation for Educational Research.

Lipkin, S. (2016). The Educational Experiences of Looked After Children: The Views of Young People in Two London Boroughs. Doctoral dissertation. London: University College London.

Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., and Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev. 71, 543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164

MacRitchie, I. (2019). MCR Pathways’ relationship based practice at scale: revolutionising educational outcomes for care-experienced young people. Scottish J. Resid. Child Care 18, 92–107.

Mannay, D., Evans, R., Staples, E., Hallett, S., Roberts, L., Rees, A., et al. (2017). The consequences of being labelled ‘looked-after’: exploring the educational experiences of looked-after children and young people in Wales. Br. Educ. Res. J. 43, 683–699. doi: 10.1002/berj.3283

Mannay, D., Smith, P., Turney, C., Jennings, S., and Davies, P. H. (2021). Becoming moreconfident in being themselves’: the value of cultural and creative engagement for young people in foster care. Qualit. Soc. Work 1–19.

Mannay, D., Staples, E., Hallett, S., Roberts, L., Rees, A., Evans, R., et al. (2015). Understanding the educational experiences and opinions, attainment, achievement and aspirations of looked after children in wales. Soc. Res. 62:201. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015936

Mannay, D., Staples, E., Hallett, S., Roberts, L., Rees, A., Evans, R., et al. (2019). Enabling talk and reframing messages: working creatively with care experienced children and young people to recount and re-represent their everyday experiences. Child Care Practice 25, 51–63. doi: 10.1080/13575279.2018.1521375

Masson, J. (2002). “Researching children’s perspectives: legal issues,” in Researching children’s perspectives, 2nd Edn, eds A. Lewis and G. Lindsay (Buckingham: Open University Press).

McAuley, C., and Davis, T. (2009). Emotional well-being and mental health of looked after children in England. Child Family Soc. Work 14, 147–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2009.00619.x

McClung, M., and Gayle, V. (2010). Exploring the care effects of multiple factors on the educational achievement of children looked after at home and away from home: an investigation of two scottish local authorities. Child Family Soc. Work 15, 409–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2010.00688.x

McGhee, K., and Ross, E. (2015). Scottish Care Leavers Covenant & Agenda For Change: What’s The Big Idea? CELCIS 2015: Travelling Together. Glasgow: Centre for Excellence for Children’s Care and Protection.

Melkman, E., Mor-Salwo, Y., Mangold, K., Zeller, M., and Benbenishty, R. (2015). Care leavers as helpers: motivations for and benefits of helping others. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 54, 41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.05.004

Mendis, K., Lehmann, J., and Gardner, F. (2018). Promoting academic success of children in care. Br. J. Soc. Work 48, 106–123.

Mezey, G., Robinson, F., Campbell, R., Gillard, S., Macdonald, G., Meyer, D., et al. (2015). Challenges to undertaking randomised trials with looked after children in social care settings. Trials 16:206. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0708-z

O’Donnell, C., Sandford, R., and Parker, A. (2019). Physical education, school sport and looked-after-children: health, wellbeing and educational engagement. Sport Educ. Soc. 25, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2019.1628731

O’Higgins, A., Sebba, J., and Gardner, F. (2017). What are the factors associated with educational achievement for children in kinship or foster care: a systematic review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 79, 198–220. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.06.004

O’Higgins, A., Sebba, J., and Luke, N. (2015). What is the Relationship Between Being in Care and the Educational Outcomes of Children? An International Systematic Review. Oxford: Rees Centre for Research in Fostering and Education. Available online at https://www.brightonandhovelaw.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/ReesCentreReview_EducationalOutcomes.pdf

O’Neill, L., Harrison, N., Fowler, N., and Connelly, G. (2019). ‘Being A Student With Care Experience is Very Daunting’: Findings From A Survey of Care Experienced Students in Scottish Colleges and Universities. Glasgow: CELCIS.

Osborne, M., and Gallacher Murphy, M. (2002). Articulation Links Between Further Education Colleges and Higher Education Institutions in Scotland. A Research Review of FE/HE Links: A Report to the Scottish Executive Enterprise and Lifelong Learning Development. Glasgow: Centre for Research in Lifelong Learning, University of Stirling and Glasgow Caledonian University, 4–17.

Quarmby, T., Sandford, R., and Elliot, E. (2019). ‘I actually used to like PE, but not now’: understanding care-experienced young people’s (dis) engagement with physical education. Sport Educ. Soc. 24, 714–726. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2018.1456418

Refaeli, T., Mangold, K., Zeira, A., and Köngeter, S. (2017). Continuity and discontinuity in the transition from care to adulthood. Br. J. Soc. Work 47, 325–342. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcw016

Rosenthal, R., and Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom. Urban Rev. 3, 16–20. doi: 10.1007/BF02322211

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55:68. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Samuels, G. M., and Pryce, J. M. (2008). “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger”: survivalist self-reliance as resilience and risk among young adults aging out of foster care. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 30, 1198–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.03.005

Scottish Children’s Reporter Administration (SCRA) (2018). Scottish Children’s Reporter Administration Annual Report 2017/18. Available online at: https://www.scra.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/SCRA-Annual-Report-2017-18.pdf (accessed June 14, 2019).

Scottish Executive (2007). Looked After Children and Young People: We Can and Must do Better. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive.

Scottish Funding Council (SFC) (2018). Care Experienced Students at College and University. Available online at: http://www.sfc.ac.uk/web/FILES/Access/Care_Experience_students_in_college_and_university.pdf (accessed June 27, 2019).

Scottish Funding Council (SFC) (2019). Scotland’s Colleges 2019 Report. Available online at: http://www.sfc.ac.uk/news/2019/news-72117.aspx (accessed June 27, 2019).

Scottish Government (2012). Peer Mentoring Opportunities for Looked After Children and Care Leavers. Available online at: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/research-and-analysis/2012/06/peer-mentoring-opportunities-looked-children-care-leavers/documents/peer-mentoring-opportunities-looked-children-care-leavers-2012/peer-mentoring-opportunities-looked-children-care-leavers-2012/govscot%3Adocument/00394530.pdf" (accessed July 14, 2019).

Scottish Government (2017). Support Children’s Learning: Statutory Guidance on the Education (Additional Support for Learning) Scotland Act 2004 (as amended). Code of Practice (Third Edition) 2017. Available online at: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/advice-and-guidance/2017/12/supporting-childrens-learning-statutory-guidance-education-additional-support-learning-scotland/documents/00529411-pdf/00529411-pdf/govscot%3Adocument/00529411.pdf (accessed June 28, 2019).

Scottish Government (2018). Education Outcomes for Looked After Children: 2016 to 2017. Edinburgh: Scottish Government: Children, Education and Skills.

Scottish Government (2019a). Looked After Children: Policy. Available online at: https://www.gov.scot/policies/looked-after-children/ (accessed May 22, 2019).

Scottish Government (2019b). Children’s Social Work Statistics 2017-18. Scottish Government: Children, education and skills. Available online at: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/statistics/2019/03/childrens-social-work-statistics-2017-2018/documents/childrens-social-work-statistics-scotland-2017-18/childrens-social-work-statistics-scotland-2017-18/govscot%3Adocument/childrens-social-work-statistics-scotland-2017-18.pdf (accessed May 22, 2019).

Scottish Parliament (2009). The Looked After Children (Scotland) Regulations 2009. Available online at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ssi/2009/210/pdfs/ssi_20090210_en.pdf (accessed May 20, 2019).

Scottish Parliament (2014). Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014. Edinburgh: Scottish Parliament.

Shonokoff, J., Levitt, P., Bunge, S., Cameron, J., Duncan, G., Fisher, P., et al. (2015). Supportive Relationships and Active Skill-Building Strengthen the Foundations of Resilience: Working Paper 13. Cambridge, MA: National Scientific Council on the Developing Child.

Stein, M. (2008). Resilience and young people leaving care. Child Care Practice 14, 35–44. doi: 10.1177/1359104513508964

Sugden, E. J. (2013). Looked-after children: what supports them to learn? Educ. Psychol. Practice 29, 367–382. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2013.846849

Swain, J. (2018). A Hybrid Approach to Thematic Analysis in Qualitative Research: Using A Practical Example in Sage Research Methods. London: Sage Publications, doi: 10.4135/9781526435477

The Children (Scotland) Act (1995). Scotland’s Children - The Children (Scotland) Act 1995 Regulations and Guidance: Volume 1 Support and Protection for Children and Their Families. Available online at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotlands-children-children-scotland-act-1995-regulations-guidance-volume-1-support-protection-children-families/pages/0/ (accessed June 28, 2019).

Thompson, A. E., Greeson, J. K. P., and Brunsink, A. M. (2016). Natural mentoring among older youth in and aging out of foster care: a systematic review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 61, 40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.12.006

Tormey, P. (2019). Reaching beyond or beyond reach: challenges influencing access to higher education for care-experience learners in scotland. Scottish J. Resid. Child Care 18, 78–91.

Who Cares? Scotland (2018). Response to Consultation on the Empowering Schools: A Consultations on the Provisions of the Education (Scotland) Bill. Available online at: https://www.whocaresscotland.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/WCS-response-to-consultation-on-Empowering-Schools-Education-Scotland-Bill-Jan-18-1.pdf (accessed June 26, 2019).

Keywords: care experienced young people, looked after children (LAC), academic experiences, further education, inclusive education

Citation: Howard K and MacQuarrie S (2022) Perspectives of Care Experienced Young People Regarding Their Academic Experiences in Further Education. Front. Educ. 7:821783. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.821783

Received: 24 November 2021; Accepted: 31 January 2022;

Published: 24 March 2022.

Edited by:

Isabel Menezes, University of Porto, PortugalReviewed by:

Eavan Brady, Trinity College Dublin, IrelandJosé Pedro Amorim, University of Porto, Portugal

Copyright © 2022 Howard and MacQuarrie. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sarah MacQuarrie, c2FyYWgubWFjcXVhcnJpZUBtYW5jaGVzdGVyLmFjLnVr

Kirstie Howard

Kirstie Howard Sarah MacQuarrie

Sarah MacQuarrie