- Department of English Language and Literature, University of Mazandaran, Babolsar, Iran

A review of the various approaches to L2 listening instruction suggests that they were more of text- or communication-oriented approaches and less of learner-oriented ones. More recently, the focus has shifted to engage L2 listeners in their own listening comprehension process through strategy instruction inside the classroom and strategy use outside the classroom. In this regard, Vandergrift and Goh suggested a metacognitive approach to L2 listening instruction in which listening homework is assigned to L2 listeners as an extensive listening activity. Thus, the present article reports on a qualitative study that explores the role of embedding listening homework in metacognitive intervention in the case of English as Foreign Language listening comprehension and the problems learners encounter during listening. A group of intermediate-level male and female learners (N = 25) speaking Persian as the first language participated in embedded listening tasks. As part of a metacognitive intervention, the learners were given listening homework for which they were requested to view five news programs drawn from the BBC website for 5 weeks and complete diaries with a self-directed listening guide before, during, and after watching the programs. Totally, 116 diary entries were analyzed and data about factors influencing their listening comprehension processes and the actual notes they took during planning, monitoring, and evaluating stages of listening comprehension were collected. To categorize and analyze the diary entries, Goh’s framework was used as the analytical framework. Results indicated that diaries with a self-directed listening guide served pedagogical purposes by raising the learners’ metacognitive knowledge and providing them with opportunities to plan, monitor, and evaluate their unseen listening processes. It helped listeners to reflect on their listening homework, find the gap, take action to resolve their listening problems, and experience a sense of achievement and confidence. Possible reasons for findings are outlined and recommendations for future research are presented.

Introduction

Homework is a task assigned to students for out-of-class learning and has positive effects on their achievement (Cooper, 1989; Cooper et al., 2006; Jerrim et al., 2019, 2020; Martin, 2020). For example, it increases the time on task for the L2 learners in their leisure time such that it improves their attitude toward school in general and learning in particular resulting in improved study habits and skills. Besides, it brings about better self-direction, self-discipline, and problem-solving which are conducive to greater achievement (Cooper et al., 2006).

In traditional approaches, there has not been an equal emphasis on the four skills. Writing skill was likely to be used three times more than reading, five times more than speaking, and seven times more than listening (Wallinger, 2000). In fact, writing and reading skills were targeted by out-of-class homework in foreign language classes more than listening and speaking skills (Wallinger, 1997). Gradually, as there was a change of teaching methods from traditional approaches to the ALM and more recently CLT methods, speaking and listening skills have become the area of concern in L2 homework assignments at all levels of language learning (Wallinger, 2000). It was thought that laying emphasis on speaking and listening skills would in turn ease the development of writing and reading skills in addition to improving the communicative competence of the learners (Cheng, 2015). Today, due to the implicit nature of the listening skill, teachers would like to assist L2 learners with their listening comprehension process through out-of-class listening homework, thus calling for more studies in this area (Vandergrift and Goh, 2012).

Generally speaking, a great deal of informal listening development occurs outside the classroom where L2 learners have more chances of listening to various materials available on the Internet or mass media (Vandergrift and Goh, 2012). Nevertheless, many L2 learners lack the self-directing skills to usher their listening development through these extensive out-of-class listening activities and are still dependent on their teachers for instructions and directions (Vandergrift and Goh, 2012). To assist the L2 learners with becoming more self-directed in performing out-of-class listening activities, teachers can use listening homework that raises their metacognitive knowledge of listening strategies, which can be taught through the metacognitive intervention (MI) (Goh, 2008; Cross and Vandergrift, 2014). MI is one type of strategy instruction that assists L2 learners in using the metacognitive strategies to fulfill their listening tasks (Vandergrift and Goh, 2012).

Most past studies have investigated the MI embedded in listening course books and implemented in classrooms, but few have concentrated on listening homework as out of classroom activities (Goh, 2008; Cross and Vandergrift, 2014). Thus, there is a need for different MI approaches to be put into practice out of classrooms to increase options for teachers and answer diverse learner needs (Goh, 2008). However, Vandergrift and Cross (2015, p. 5) state that “there has yet been no attempt to establish which configuration of possible techniques proposed by Vandergrift and Goh (2012) can optimize listening development.”

Various new ideas for embedding the MI in listening comprehension, such as the metacognitive pedagogical sequence, have been proposed by Vandergrift and Goh (2012), which have been the focus of numerous studies to date (Vandergrift, 2003; Vandergrift and Tafaghodtari, 2010; Cross, 2011; Bozorgian, 2014; Bozorgian et al., 2020; Goh and Vandergrift, 2021). Among them, embedding listening homework in MI as an out-of-class activity has received little attention. Hence, the goal of this article is to contribute to the developing understanding of the listening homework assigned as part of MI for L2 learners’ listening comprehension as well as the problems they encounter during listening based on Goh’s (1999) analytical framework. To this end, the current qualitative study investigated learner responses to the out-of-class listening tasks through MI.

Review of Literature

Homework was primarily defined as “any task assigned by school teachers intended for students to carry out during non-school hours” (Cooper et al., 2006, p. 1), which enhances both learning and instruction in various ways. For example, it provides L2 learners with an opportunity to practice or review the previously learnt materials taught in class, thus assisting them with reaping the maximum benefits every time a new material is covered (Jerrim et al., 2019, 2020; Martin, 2020). Besides, most teachers enumerated the following purposes for homework: practice, preparation, and extension (Palardy, 1995). As a result, homework assignments could bring about positive effects such as better understanding and retention, greater self-direction and management, and more independent problem-solving and action (Cooper, 1994). Homework assignments have often incorporated more than one skill. The skill areas that have generally been the target of homework assigned to L2 learners were reading, writing, memorization, and rehearsal (Cooper, 1994). To the best of our knowledge, no qualitative studies to date have focused on listening homework in an EFL context. Thus, it calls for more studies in this research area with an aim to examine the effectiveness of homework in the realm of listening instruction.

With regard to listening comprehension problems, numerous studies have been conducted to date (e.g., Goh, 1999, 2000; Hasan, 2000; Zeng, 2007; Wang and Renandya, 2012; Renandya and Hu, 2018; Namaziandost et al., 2019; Ozcelik et al., 2019, 2020). The most comprehensive one is that of Goh’s (1999) who probed into the listening comprehension problems of 40 Chinese ESL learners based on the theoretical framework of Flavell (1979) metacognitive knowledge (i.e., person, task, and strategy). The listening comprehension problems reported by the majority of low-ability and high-ability listeners mostly revolved around text (e.g., vocabulary, speech rate, type of input, and visual support) and listener (e.g., prior knowledge, purpose for listening, context knowledge, concentration, and physical and psychological state) characteristics. In terms of frequency, the listening comprehension problems were related to vocabulary, prior knowledge, speech rate, type of input, and speaker’s accent, respectively. She further examined the extent to which they were aware of them using interviews and learner diaries. To categorize and analyze the data, she identified twenty factors and condensed them into five categories, namely text, speaker, listener, task, and environment. Findings suggested that listeners with higher metacognitive awareness display greater listening competence and can better control and manage their listening development.

Namaziandost et al. (2019) explored the relationship between the listening comprehension problems and strategies reported by 60 Iranian advanced EFL learners. The listening comprehension problems were input, context, listener, process, affect, and task-related variables. In addition, the listening strategies used were cognitive, metacognitive, and socio-affective strategies. Findings were indicative of a strong and significant relationship between the two variables, namely listening comprehension problems and strategy use among the advanced EFL learners. In another study, Ozcelik et al. (2020) probed into the positive effects of self-regulation on listening comprehension problems of 60 Flemish EFL learners, namely process, listener, affect, input, task, and social-related problems. Findings suggested that re-hearing an audio recording removes the burden on the participants’ working memory, assists them with catching up with the speed, and ultimately enhances their listening comprehension abilities.

In terms of metacognitive strategy instruction, studies such as Vandergrift and Baker (2015) and Alamdari and Bozorgian (2022) examined the effectiveness of instructing metacognitive strategies to L2 learners to facilitate their L2 listening comprehension. Findings suggested that these strategies could successfully ease the listening comprehension process and draw listeners’ attention to it. In addition, Tanewong (2018) also conducted a comparative study to examine the effect of a metacognitive pedagogical sequence on the development of L2 listening metacognition and listening comprehension achievement of 64 less-skilled Thai EFL listeners over a period of one semester. Results suggested that the experimental group’s metacognitive development of problem-solving, planning, and evaluating significantly improved. In addition, the self-directed listening assignments after the intervention affected both groups’ performance scores on the final achievement test. Lastly, the listening comprehension problems mentioned in this article were those with perceptual processing, limited L2 vocabulary, and unfamiliarity with L2 pronunciation.

The metacognitive instruction in L2 listening is accomplished in two forms, namely implicit and explicit. The implicit instruction approach to MI includes prompting (i.e., reminding listeners to use metacognitive strategies) and modeling (i.e., instructing listeners on how to use metacognition in action). On the other hand, the explicit instruction approach to MI includes direct instruction (i.e., promoting listeners’ declarative, procedural, and conditional knowledge) and teaching benefits (i.e., motivating listeners to acquire new [metacognitive] strategies) (Flanigan et al., 2016). Findings of most studies on the MI have collectively suggested that it has a significant effect on the L2 learners’ listening performance (Bozorgian et al., 2020) and metacognitive awareness (Maftoon and Fakhri Alamdari, 2020). However, rarely did the above studies focus on L2 listening homework, as suggested by Vandergrift and Goh (2012), embedded in metacognitive intervention aimed at resolving the listening comprehension problems. In addition, little research has been conducted with an aim to explore the effect of embedding listening homework in MI on the listening ability of L2 learners out of classrooms (Vandergrift and Goh, 2012). L2 listening homework encourages further involvement with a listening task and may, in turn, promote learner control and automatization in future learning experiences (Tanewong, 2018). Listening homework, being described as a tool, helps researchers access the voices of learners and plays a pedagogical role in channeling learners’ attention on ways to approach and benefit from listening tasks. It aids in the development of language and language learning awareness.

Theoretical and Analytical Frameworks

Metacognition is often defined with the terse definition “cognition about cognition” or “thinking about thinking” (Flavell, 1979) and is used to regulate learning processes in general and language skills in particular (Vandergrift and Goh, 2012; Goh and Vandergrift, 2021). Brought to second language learning first by Wenden (1987), metacognition provides learners with opportunities to improve their learning through planning, monitoring, evaluation, and reflection, which strengthens learners’ self-regulation and autonomy (Schraw, 2006; Veenman et al., 2006; Zimmerman, 2008; Kemp, 2009). During the planning phase (e.g., anticipating), L2 learners become familiar with the topic and text type and predict the possible information or words they might hear in the listening task. During the monitoring phase (e.g., checking the accuracy of anticipations), L2 learners verify their initial predictions and correct them as required. During the evaluation phase (e.g., verifying overall comprehension, ideas, and performance), L2 learners evaluate what they have understood and decide on the parts in need of special attention. During the reflection phase (thinking about one’s own listening comprehension process), L2 learners reflect on how they arrive at the meanings of certain vocabulary items, think about what compensation strategies to use for what they cannot understand, and write goals for the next listening task. Many theorists and scholars such as Schraw (1998), Tarricone (2011), and Goh and Vandergrift (2021) recognized that metacognition encompasses knowledge of cognition (or metacognitive knowledge) and regulation of cognition (or metacognitive skills). Knowledge of cognition refers to declarative (person) knowledge, procedural (strategy) knowledge, and conditional (task) knowledge. On the other hand, regulation of cognition includes processes such as planning and evaluation, problem solving, monitoring, directed attention, mental translation, etc. (Veenman, 2011; Vandergrift and Goh, 2012).

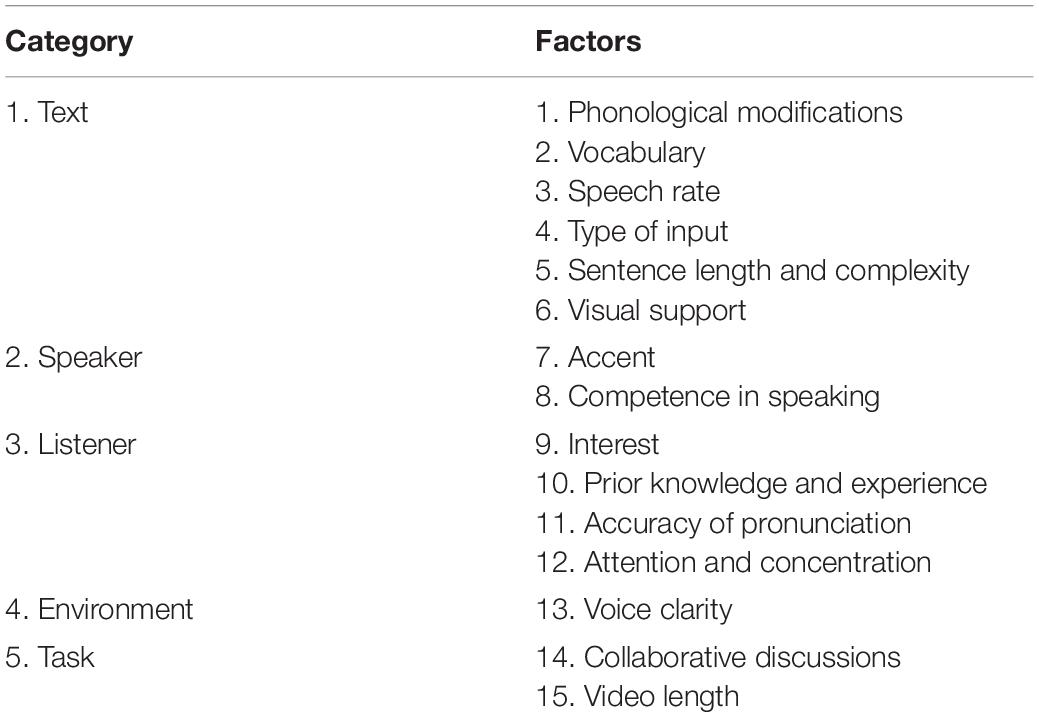

The analytical framework of the present paper is that of Goh’s (1999) discussing comprehension problems L2 listeners typically face. In doing so, she identified 20 factors related to the L2 listeners’ task knowledge, which they believed have influenced their L2 listening comprehension. These were further categorized into five key components, namely text, speaker, listener, task, and environment. The subcomponents were also delineated in her framework, which are as follows. The text category consisted of (1) phonological modification, (2) vocabulary, (3) speech rate, (4) type of input, (5) sentence length and complexity, (6) visual support, (7) signposting and organization, and (8) abstract and non-abstract topics. The speaker category was composed of (9) accent and (10) competence in speaking. The listener category was comprised of (11) interest and purpose, (12) prior knowledge and experience, (13) physical and psychological states, (14) knowledge of context, (15) accuracy of pronunciation, (16) knowledge of grammar, (17) memory, and (18) attention and concentration. The task category included (19) sufficient time available for processing and finally the environment category included (20) physical condition.

The Metacognitive Instruction in L2 Listening

The field of L2 listening instruction has witnessed a bevy of approaches and strategies to ease the L2 listening process for EFL learners. Recent research in this domain suggests that skilled listeners employ efficiently a wide range of strategies including cognitive and metacognitive ones in an orchestrated fashion (Graham and Macaro, 2008; Vandergrift and Goh, 2012; Goh and Vandergrift, 2021). Thus, Vandergrift and Goh (2012) proposed a metacognitive framework for listening instruction, placing metacognition at its core to develop metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive skills. Cross (2015) also opined that metacognitive instruction in L2 listening is a pedagogical approach designed to enhance and develop L2 listeners’ person, task, and strategy knowledge. He perceived it as a process-based and holistic approach to L2 listening instruction that assists L2 listeners with self-monitoring, self-evaluating, self-managing, and self-regulating their listening comprehension process. As a result, L2 listeners will become capable of goal-setting, monitoring, regulating, and controlling their thinking process and strategic behavior while listening. In order to optimize the L2 listening development and resolve listening comprehension problems, the configuration of embedding L2 listening homework as part of an explicit metacognitive instruction has not yet been explored. Thus, we strive to answer the following two research questions:

RQ1: What are EFL learners’ problems while carrying out L2 listening homework embedded in MI?

RQ2: How did the students actualize the planning, monitoring, and evaluation stages of metacognitive instruction in their diary entries?

Methodology

Design

The present paper adopted a qualitative design with the purpose of revealing the listening comprehension problems of 25 EFL learners while they were carrying out their L2 listening homework embedded in MI. The importance of using qualitative design stems from the provision of a rich and comprehensive narrative that unfolds the realities experienced by the participants with no prior hypotheses (Ary et al., 2018).

Participants

Participants aged between 19 and 20 were 25 learners, male (N = 12) and female (N = 13), who were selected to participate in this qualitative study through purposeful sampling. The choice of this sampling technique was informed by its potential use in qualitative research studies for the sake of identifying and selecting information-rich cases (Ary et al., 2018). The participants’ permission to take part in this study was obtained hierarchically from the university authorities and the teacher to the participants themselves through consent forms. Then, the diary entries used in this study were collected from undergraduates with Bachelor of Arts (BA) in Teaching English as Foreign Language (TEFL) attending a university in Iran. Based on their self-directed reports and their teacher’s confirmation, their proficiency level was equivalent to IELTS 5. Pseudonyms were used to analyze the data.

Instruments and Materials

News Recorded Audios

Materials were downloaded from the BBC news website.1 Five 2-min video programs on multiple topics of political issues were prerecorded and randomly selected and assigned to learners as homework.

Metacognitive Intervention for Listening Homework

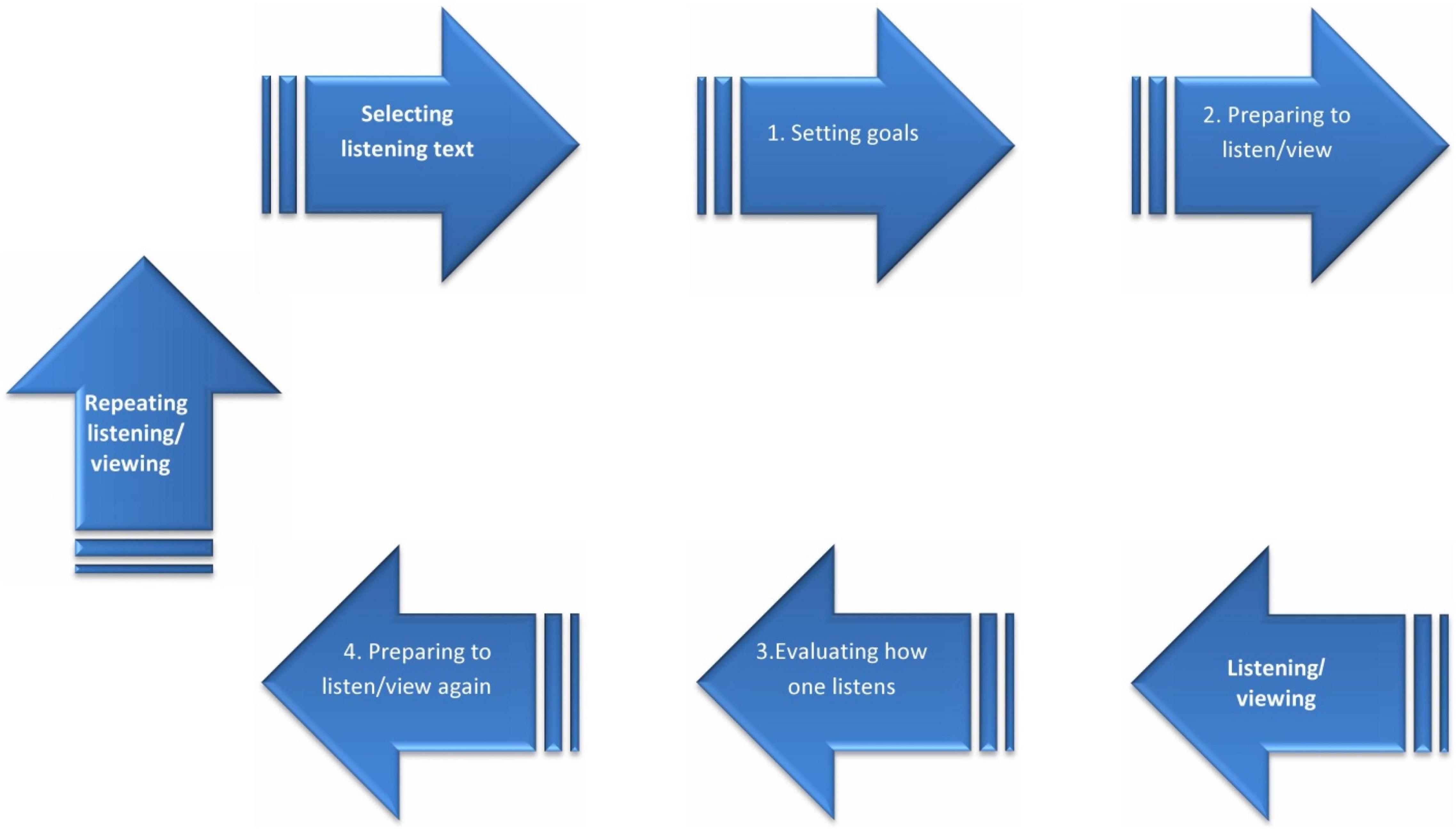

The MI has three stages, namely selecting listening homework (i.e., setting goals), listening (i.e., preparing to listen and evaluating how one listens), and repeating listening (i.e., preparing to listen again). The goal of this integrated MI is to enhance text-focused comprehension and metacognitive knowledge development (Vandergrift and Goh, 2012).

Procedure

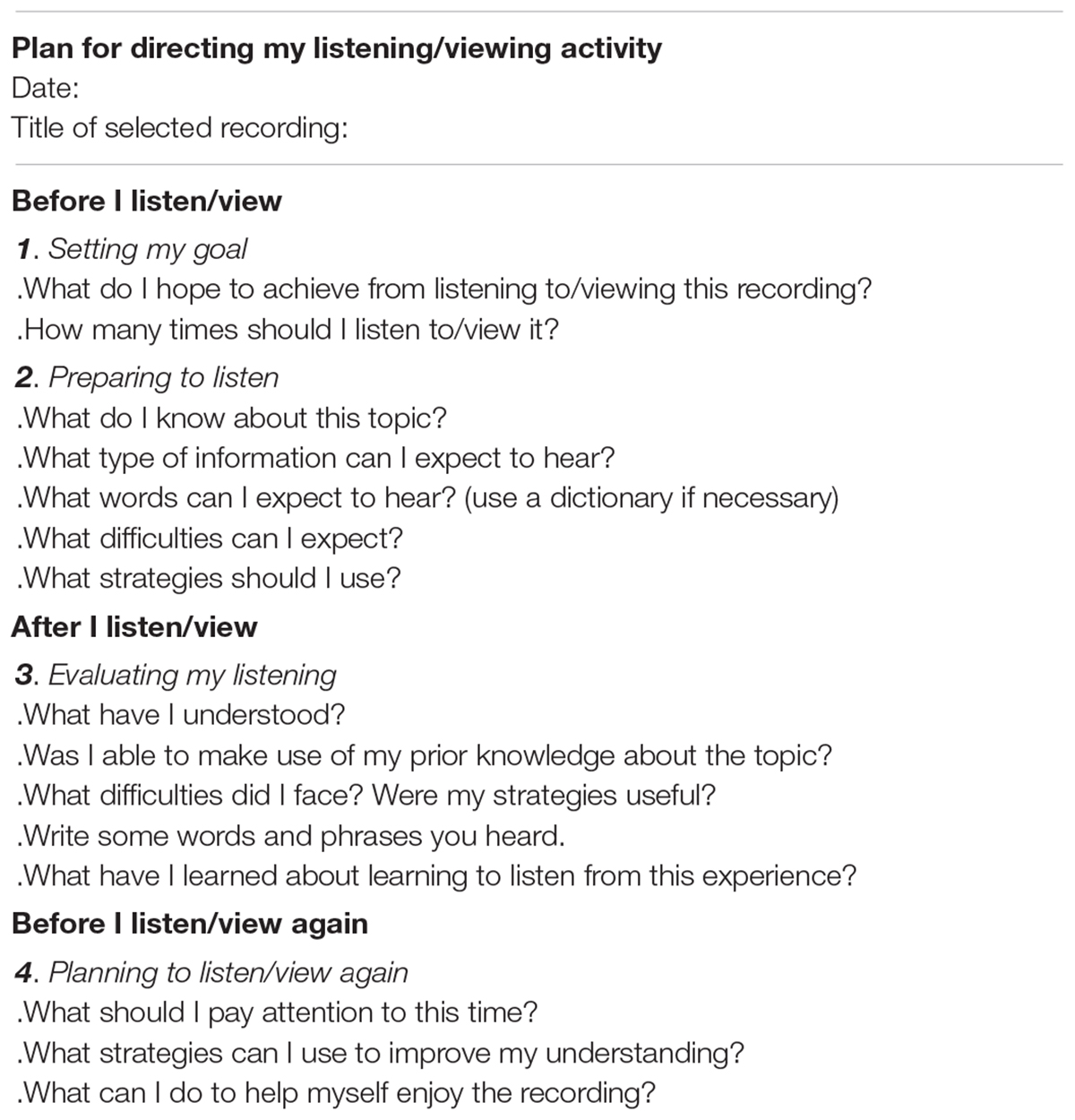

In general, the participants received explicit instruction on how to complete a diary, what prompts to answer and when (before, during, and after watching a news program), and how to complete listening tasks in class. Then, they went home and watched a news program and completed the diaries each week for 5 weeks. In particular, they were trained to use self-directed listening prompts (or metacognitive strategies such as planning, predicting, and evaluating) while doing the out-of-class listening homework for five sessions. Researcher 1 familiarized them with the related metacognitive strategies in class. As their listening homework, they were requested to view five news programs and complete diaries with a self-directed listening guide (including prompts) before, during, and after watching the programs at home. The plan for directing learners to listen/view (featuring self-directed listening prompts) is reported in the Appendix. The components of the self-directed listening guide, proposed by Vandergrift and Goh (2012), are as follows: (1) Setting my goals through asking questions like: What do I hope to achieve from listening to/viewing this recording?; How many times should I listen/view it?; (2) Preparing to listen/view through asking questions like: What do I know about this topic?; What type of information can I expect to hear (Use dictionaries if necessary)?; What difficulties can I expect?; What strategies should I use?; (3) Evaluating my listening through asking questions like: What have I understood?; Was I able to make use of my prior knowledge about the topic?; What difficulties did I face?; Were my strategies useful?; What were some words and phrases you heard?; What have I learned about learning to listen from this experience?; and (4) Before I listen/view again through asking questions like: What should I pay attention to this time?; What strategies can I use to improve my understanding?; and What can I do to help myself enjoy the recording?

The three stages of the MI, namely selecting listening homework (i.e., setting goals), listening (i.e., preparing to listen and evaluating how one listens), and repeating listening (i.e., preparing to listen again) are unpacked below.

Stage 1

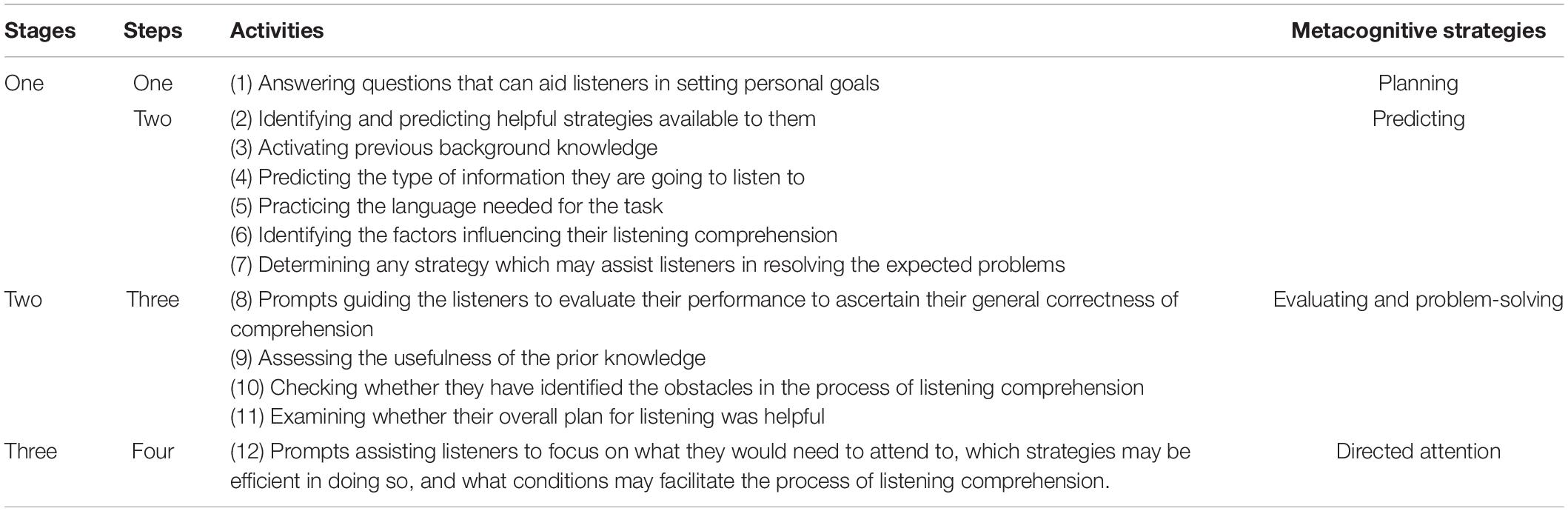

Figure 1 and Table 1 indicate the first two types of prompts in the pre-listening stage (first stage), namely planning and predicting. The learners were supposed to answer questions that aided them in setting personal goals, identify and predict helpful strategies available to them, activate previous background knowledge, predict the type of information they are going to listen/view, practice the language needed for the task, identify the factors influencing their listening comprehension, and determine any strategy which may assist them in resolving the expected problems.

Figure 1. Four types of prompts for self-directed listening/viewing (Vandergrift and Goh, 2012, p. 130).

Stage 2

During the second stage and after listening/viewing the listening task, prompts guided the learners to evaluate their performance with an aim to ascertain their general correctness of comprehension, assess the usefulness of the prior knowledge, check whether they have identified the obstacles in the process of listening comprehension, and examine whether their overall plan for listening was helpful.

Stage 3

In the final stage, before listening/viewing the listening task again, the guiding prompts assisted learners to focus on what they would need to attend to, which strategies may be efficient in doing so, and what conditions may facilitate the process of listening comprehension.

Data Collection Procedure

The researchers began the data collection after the participants agreed on serving the purpose of the study through a consent form and thus one of the researchers described the stages of L2 listening homework embedded in MI. At the beginning of the intervention, the participants were trained on how to keep a diary and then they were requested to keep a diary (see Appendix) for 5 weeks and write their answers according to the guiding prompts delineated at each stage every week they watched the video.

During the intervention, they viewed five news programs drawn from the BBC website for 5 weeks and completed diaries before, during, and after watching the programs. In order to facilitate the process of data collection, the learners were provided with the guide through an e-mail and once they did a listening homework and completed the diary slots, they emailed it to the second researcher on a weekly basis. Some learners did not submit all five diaries requested from them and the researchers received 125 diaries in total.

At the end of the intervention, once the data were collected, they were checked for completeness and nine of them were discarded as they were half-finished since not all the prompts related to the three stages of the intervention were answered. Finally, 116 diary entries from 25 learners were considered in total and the data about factors influencing their listening comprehension processes and the actual notes they took during planning, monitoring, and evaluating stages of listening comprehension were analyzed.

Data Analysis

To analyze and interpret the collected data for the first research question, the researchers first conducted a content analysis (McDonough and McDonough, 1997) to identify the problems, then counted and kept a tally of their reports. Repeated mention of the problem from the same learner was not counted as a new report. They were then categorized based on the categorization introduced by Goh (1999) for the first research question, and three new factors related to task and environment were identified from the data and added to the initial categorization. Finally, emerged categorizations and problems were cross-checked by a colleague and some minor changes were made. To answer the second research question, learners’ answers to L2 listening homework were checked for any evidence indicating their action pertaining to planning, monitoring and evaluating processes related to each stage of the metacognitive intervention, learner control, change in attitude and any evidence of progress.

Results and Discussion

Research Question 1

The first research question focuses on what listening comprehension problems the EFL learners encounter while carrying out L2 listening homework embedded in MI. The learners reported on 15 factors influencing their ability to listen well. These factors are aligned with Goh’s (1999) five broad categories consisting of text, speaker, listener, environment, and task and the relevant underlying factors listed in Table 2.

The Most Commonly Cited Factors

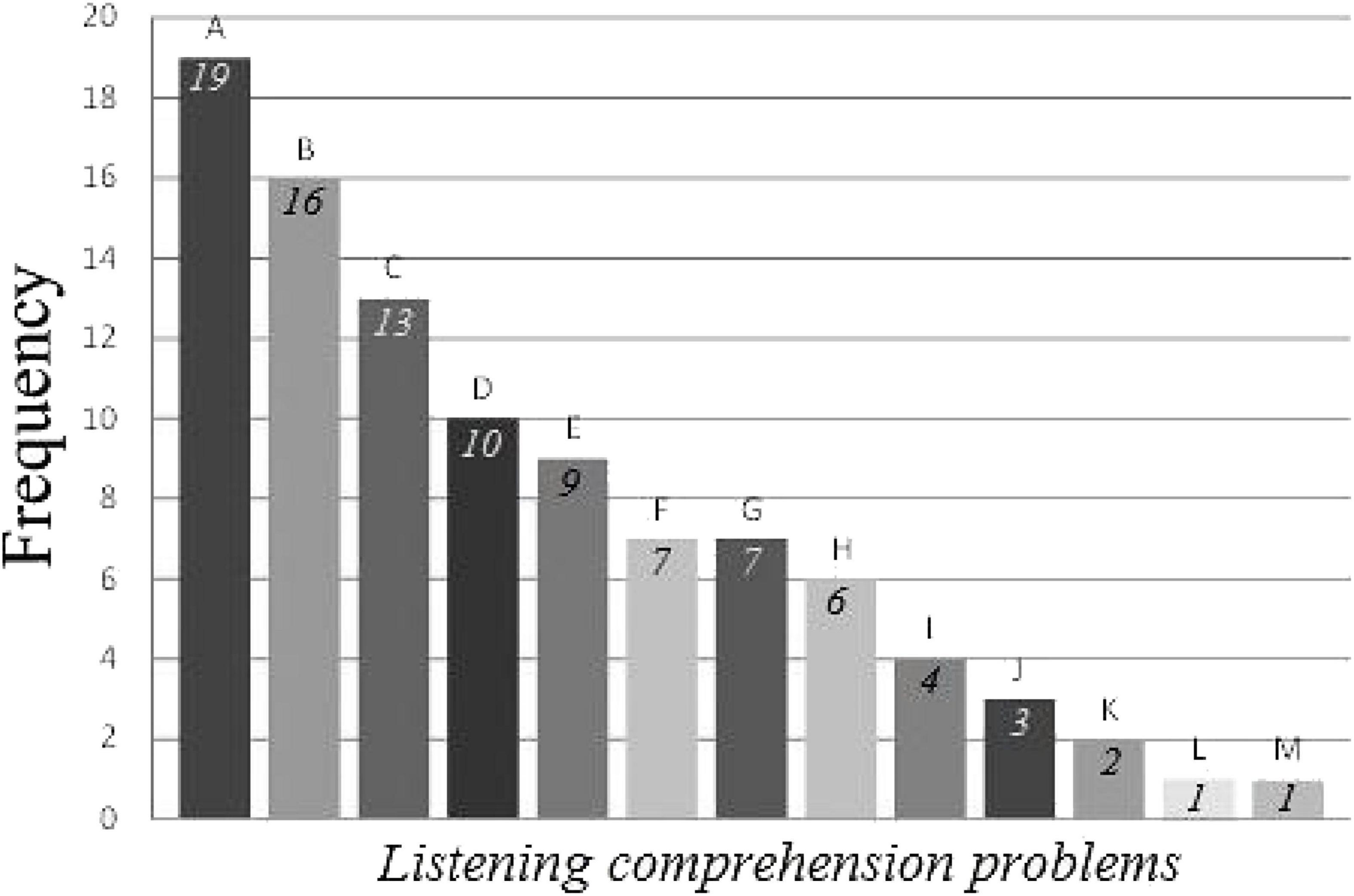

Figure 2 shows the frequency of reporting the above-mentioned 15 factors. Three factors were reported by a majority of the learners (N = 13). These have been presented with examples from learners’ diaries.

Figure 2. Frequency of learners’ knowledge about the factors that influenced their listening comprehension. A. vocabulary, B. accent, C. prior knowledge and experience, D. speech rate, E. voice clarity, F. collaborative discussions, G. sentence length and complexity, H. interest and purpose, I. attention and concentration, J. visual support, K. accuracy of pronunciation, L. competence in speaking, M. type of input.

Vocabulary

Most learners (76%) considered vocabulary as an important factor in facilitating their listening comprehension. This was asserted by “David” when he stated that “[i]f I focus more on the keywords, I can improve my understanding.” Some learners reported that their limited vocabulary knowledge resulted in misunderstanding the main points of the listening tasks. For example, “Mark” noted that “[p]erhaps, I get the claim or meaning of some parts or words wrongly and it makes me confused during listening.” Several others (e.g., Difa and Tara) stated that the lack of vocabulary knowledge is a burden for their overall listening comprehension. “Difa” noted that she “[h]ad difficulty for understanding the main point of this video” and that she “should try not to concentrate too much on listening to this video word by word.” “Tara” also expressed difficulty with vocabulary when she wrote that she “[d]id not know the meaning of some new words and [she] did not get the point of the video.” Other learners shared that their listening was interrupted by new words leading to losing the rest of the words and breakdown in comprehension or generally concentration For example, “Zoya” wrote that “[s]he tried to find out what a previous word meant, so [she] missed the next words.”

Accent

Some learners (64%) believed that accents in the video were incomprehensive and affected their ability to recognize words. For example, “Fei” believed that “[w]ords were not much hard but accents were somehow strange and not understandable.” In addition, “Yasi” asserted that “[t]he accents of these videos are in British. It makes listening a little difficult for me.” Others emphasized the importance of familiarity with other accents. In this regard, “Dora” maintained that she “[h]ad learned that mastering listening skill depends on practicing, experiencing or listening different types of accents very much.”

Prior Knowledge

Just over half of the learners (52%) considered the availability of prior knowledge as a necessary factor for overall listening comprehension. For example, “Helia” stated that “[I] should search about the topic. This option is useful and improves your understanding of whole idea.” Besides, “Arnika” confirmed that “[I] have learned that I should have some information about the topic before listening to it.” Some learners (e.g., Doa and Helia) also predicted a lack of prior knowledge as a problem for their understanding. For example, “Doa” declared that “[I] have learnt that I must get some background information about the video; otherwise, I would not understand the video.” In addition, “Helia” was able to use her prior knowledge and having found it useful, she felt happy. In this regard, she maintained that “[f]ortunately, I could use my prior knowledge.”

Other Factors

Learners (40%) identified speech rate among the factors affecting listening comprehension. For example, “Tara” expressed the fast rate of speech as a source of problem for her comprehension. In this respect, she stated that “[t]he speed of their speaking was fast and it made listening difficult for me.” “Ela” also believed that a slow speech rate would help her with sentence comprehension. She reported that “[I] have understood that if they talk a little slower, I will understand the sentences better.”

Just over a third of the learners considered voice clarity as a factor affecting their listening comprehension. Mike, for example, commented that video sound problem influenced his ability to recognize words that he heard. He added that “[t]here were some noises in some parts that made it difficult to understand the words exactly.” Another learner mentioned the noises within the listening (such as bombards, etc.) had a negative effect on her word recognition and hence comprehension of some parts. “Arnika” said that “[i]n the second part, I could not understand some parts because the situation was so noisy and I could not figure out some words.”

Sentence length and complexity were identified as having a determining role in their overall comprehension by a fourth of the learners. In this regard, “Joe” believed that “[a] significant difficulty which I faced was my weakness in understanding complex explanations that my strategies did not work in this case.” Besides, inability in figuring out the overall meaning of sentences despite understanding words individually was a problematic factor for some learners. For example, “Negar” declared that “[I] could understand word by word but I could not connect them to understand some sentences.”

A roughly similar proportion of the learners (24%) reported interest and collaborative discussions as important factors for listening comprehension. Some blamed on lack of interest causing fatigue or reluctance to watch the video. For example, “Lily” affirmed that “[t]he topic was not interesting and I got tired soon.”

Collaborative discussions in the forms of being in a group or class when watching the video were stated by some learners (e.g., Arshia, Lloyd, and Reyhaneh) to help build up knowledge and raise interest and overall understanding. “Arshia” confirmed that “[g]roup discussions about the videos can improve my understanding.” “Lloyd” also maintained that “[d]iscussing the video in class before listening to it and guessing what it might be about would make me want to listen to it more.” In addition, ‘Reyhaneh’ stated that “[t]o improve my understanding, I need to work with my friends in a group and share my understanding of the video with them. That really works for me.”

A small number of learners reported on other influences on listening. These included attention and concentration, video length, visual support, the accuracy of pronunciation, competence in speaking, and type of input and phonological modifications.

To answer the first research question, Goh’s (1999) analytical framework was employed according to which 15 factors were reported by the participants who believed have influenced their ability to listen well. These factors were in agreement with the five broad categories of Goh’s (1999) study, namely text, speaker, listener, environment, and task. To elaborate more, similar to Goh (1999), Goh and Taib (2006), Zeng (2007), and Wang and Renandya (2012), text- and listener-related problems were reported the most. This finding is consistent with those of the previous studies (e.g., Graham, 2006; Renandya and Hu, 2018; Ozcelik et al., 2019, 2020) showing that learners blamed themselves as listeners and the difficulty of texts as major hindrances to successful listening comprehension. The most commonly cited factors, namely vocabulary (76%), accent (64%), and prior knowledge (52%), reported by the majority of the learners are discussed below.

In the case of vocabulary, findings were broadly consistent with major trends in other studies (e.g., Goh’s 1999; Goh and Taib, 2006; Renandya and Hu, 2018) indicating that learners considered weakness in vocabulary as their most frequent problem, which hinders overall listening. Aligned with the same line, other studies (e.g., Vandergrift and Baker, 2015, 2018; Wallace and Lee, 2020) showed that among many variables, vocabulary knowledge was the most important for comprehension. Thus, it was considered a strong predictor of L2 listening.

In the case of accent, the findings are contrary to Goh and Taib (2006) study and in line with Goh’s (1999) in which accent was among the most problematic factors. However, it is inferred that rather than the non-nativeness of the accent, unfamiliarity with the accent has been troublesome for learners. This finding is consistent with Tauroza and Luk (1997) and Rajab and Nimehchisalem (2016) showing that the degree of familiarity with an accent determines whether that accent causes a problem in listening or not.

In the case of prior knowledge, adequate background knowledge is needed to compensate for the breakdowns in understanding. However, most learners were not able to activate any helpful prior knowledge to compensate for the gaps in their listening comprehension. The importance of familiar prior knowledge is highlighted in several studies such as Namaziandost et al. (2019), and Ozcelik et al. (2019) indicating that familiarity with the content facilitates the listening comprehension. Earlier, it was mentioned that knowledge of vocabulary has been reported as the most problematic area. It is possible to conclude that this heavy reliance on vocabulary could be due to the unavailability of prior knowledge which made learners to resort to the bottom-up strategy of word by word recognition of the speech text as also confirmed by Field (1998).

Research Question 2

The second research question asked, “How did the students actualize the planning, monitoring, and evaluation stages of metacognitive instruction in their diary entries?” To answer this question, the learners’ responses to the L2 listening homework activities have been analyzed. Results provided fresh insights into the three categories of planning, monitoring, and evaluating unpacked below.

Planning Stage

The participants of this study were involved in activities such as setting a goal, having a plan for listening, and activating their prior knowledge. For example, “Doa” stated that “[I] hope to achieve more information about politics of Syria which these days I see on top of the news.” She set a goal and decided what she would like to listen for. She then maintained her goal and predicted probable difficulties and possible strategies to resolve them. In this regard, she stated that “[I] may have a problem with the abbreviations or the technical words which I am not sure the meaning of, also some missing words because of the noises behind.” She also confirmed that “[i]t would be better to search for this video before listening, or perhaps ask some friends if they have any information.” Also, during the preparation stage, this learner activated any cultural or background knowledge available to her. Besides, she added that “[t]he only thing I know is that one of the cities in Syria was attacked by ISIS.”

Monitoring Stage

Strategy Change (Self-Management)

The L2 listening homework embedded in MI encouraged learners to take more responsibility for their language learning by self-management and proper strategy selection, depicted in Doa’s report, stating that “[d]uring listening to some parts, I didn’t understand the right words and missed some others.” For overcoming this problem stated in the planning stage, she reported she had solved it by ignoring the missing parts and focusing on the comprehended parts though the planning stage. She had decided to listen to the parts where she did not understand the words more than five or six times.

On the other hand, sometimes the learners implemented the same strategy declared in the planning stage repeatedly. In this regard, “Ela” declared that “[I] will replay those parts I do not understand. After all pausing, I can understand the whole video.” Then, she continued using this strategy for every other task until the end of the intervention program.

Evaluating Stage

Performance Evaluation

The L2 listening homework embedded in MI seems to have encouraged the learners not only to monitor the effectiveness of their employed strategies, but also to reflect on the effectiveness of their performance. For example, “Peter” reiterated that “[a] significant difficulty which I faced was my weakness in understanding complex explanations that my strategies did not work in this case.” Besides, in his next diary entry, and once asked if his new strategy worked, he stated that “[y]es, my strategies worked. I faced the same difficulty I mentioned before and I preferred not to pay much attention to the misunderstood parts at the first time of listening.”

Progress

Some learners clearly expressed improvement in certain areas such as accent, word recognition, overall listening comprehension ability, and strategy implementation as a result of their engagement in the listening process. The following extracts (e.g., Roja, Aria, Bahar, and Lily) illustrate some examples. “Roja” stated that “[t]his process helped me and my accent is much better now.” Also, “Aria” maintained that “[I] can understand more words and phrases than previous weeks by responding to prompts.” “Bahar” believed that “[her] listening skill is way better than the beginning of the program.” Finally, “Lily” expressed that “[her] strategies are improving week after week.”

Setting a Challenge

It appears that the metacognitive intervention has motivated the learners to actively set for more difficult challenges for making the listening task more interesting. This shows learners’ independent action. Here is an example from one of the reflections. “Leila” declared that “[i]f I do it as a practice of listening and put myself in a challenge to understand the video in a limited time, it will be enjoyable”. The learners seem to have set challenges to overcome their identified difficulties. Setting a challenge also functioned as a motivating factor.

Self-Satisfaction and Confidence

Once learners employed a strategy successfully, tackled a problem, and saw the positive result of the process-based intervention, they felt satisfied and positive, as stated by some learners (e.g., Fei, Kim, and Yasi). For example, “Fei” asserted that “[a]s I had guessed, after listening two times, I could understand the content completely. That’s pride.” In addition, “Kim” stated that “[I] understand everything I heard and to help my understanding, I used pause key as much as I could to think about what I have learned and even use my dictionary.” She also added that “[n]ow, I am really pleased with the result, because I understand the main idea. I think I want to continue my strategies for the next video or even some better strategies that I look for them.” Along the same line, “Yasi” maintained that “[I] feel I could understand the presentations better and the class became more interesting for me.”

Before the Listen-Again Stage

Learners were encouraged to reflect on their learning experiences while carrying out L2 listening homework embedded in MI and set goals and plan for their future listening efforts to compensate for what was not understood. The following two extracts (Doa and Bahar) illustrate some examples. “Doa” stated that “[I] should pay more attention to the main claim so that I find out the details or guess the details.” “Bahar” believed that “[I] should try to focus on what the presenter is saying and not pay attention to the noises.” In addition, “Arshia” found the repetition stage inherent in the MI useful for listening comprehension. He reported that “[l]earning to listen is a matter of repetition and spending time. If we consider these two main parts, our listening will improve.”

To answer the second research question, the findings of the present paper suggested that the ability to self-regulate learning in general and regulate listening comprehension in particular considered as “an important expected outcome of the metacognitive intervention for learners” by Vandergrift and Goh (2012, p. 101) was clearly observed among the participants as a result of carrying out L2 listening homework embedded in MI. Vandergrift and Goh (2012) believed one manifestation of this ability is learners’ effective engagement with input, management of the process and outcome of the listening task at hand in order to enhance comprehension and their utilization of the processed information. This finding is similar in nature to those of Tanewong (2018), Bozorgian et al. (2020); Alamdari and Bozorgian (2022), and Maftoon and Fakhri Alamdari (2020). The findings are also in agreement with Schraw (2006); Veenman et al. (2006), and Zimmerman (2008) in terms of self-regulation and autonomy.

The analysis of the learners’ responses to the L2 listening homework for listening activities provided fresh insights into the three categories of planning, monitoring, and evaluating. During the planning stage as a process-oriented strategy, learners were required to have a goal in mind, made a plan on how to listen, and thought about similar texts they had approached in the past, which are in alignment with Vandergrift (2004) and Tanewong (2018).

During the monitoring stage, the participants attempted to take control and find ways to understand the listening task. This ability has manifested itself through different learners’ learning behavior. Sometimes, in the planning stage of the intervention, they stated their decision to use a specific strategy to tackle the expected problem; however, in the evaluation stage, they reported they used a different strategy. It suggests that they are constantly involved in checking their understanding and consciously adapt their strategies to manage new, unpredicted challenges. This clever strategy switch could be the result of monitoring. These findings are in line with Imhof (2000, 2001), Goh and Taib (2006); Graham and Macaro (2008), Cross (2015), and Chen (2017) in that, learners in their study also reported improved listening ability by managing and monitoring their listening process.

During the evaluating stage, the participants showed focused use and evaluation of strategies for further understanding and tackling the problems they faced, which is in agreement with Tanewong (2018) and Vandergrift and Baker (2015) and contrary to Graham (2006). Also, Vandergrift and Goh (2012, p. 101) stated, “language learners who are aware of the benefits of specific listening strategies may also deliberately use these strategies to improve their listening comprehension”. As stated by Vandergrift (2004), one advantage of evaluating comprehension in the process of learning to listen is more active and better planning for the next time of listening using the cycle of planning-evaluation-planning. Another advantage is reflecting on past learning experiences and learning from them.

Conclusion, Future Directions, and Limitations

Embedding L2 listening homework in MI served pedagogical purposes by raising awareness of metacognitive knowledge and giving learners the chance to plan, monitor, and evaluate their unseen listening processes. It culminated in the listeners’ reflection on their listening, finding the gap and taking action to resolve it, sense of achievement, and confidence.

Metacognitive intervention of listening comprehension developed learners with certain characteristics. Firstly, learners appreciated the challenges of listening tasks by delineating the factors interrupting their listening comprehension process. Secondly, by planning to self-direct and self-manage their listening, monitoring and recurrently recalling useful strategies that worked in their previous listening tasks in earlier weeks of instruction, these learners actively and independently involved in the metacognitive experience. Such self-regulated actions assisted them in developing metacognitive knowledge on the one hand and the selection and use of strategies on the other hand. Furthermore, based on the learner’s reports, embedding L2 listening homework in MI assisted them to gain more confidence in their listening comprehension ability. They were also satisfied with and motivated by this method of instruction as it provided them with a sense of achievement.

The findings of this study may not be generalized to other contexts as the number of learners was small. Second, the duration of the intervention was 5 weeks; however, longer duration of an intervention ensures a better generalization. The MI can be readily used in extensive out-of-class listening activities promoting autonomous learning. However, to ensure scaffolding and receiving feedback from the teacher or classmates, it is advisable to complement it with class discussions or similar group checking. Also, future mixed-method research may be needed to investigate the effectiveness of the MI in the overall listening ability and compare it with other process-based interventions. It is also suggested that this approach be implemented with different task types as it may shed light on other aspects of learning to listen.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Mazandaran. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

HB designed the research project and supervised it throughout the process. MM wrote the introduction, review of literature, and methodology sections and refined the manuscript. EM was responsible for the results and discussion and conclusion, future directions, and limitations sections. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Associate Professor Jeremy Cross for his helpful comments and constructive feedback.

Footnotes

- ^ BBC copyright conditions permit the use of content when it is for non-commercial use.

References

Alamdari, E. F., and Bozorgian, H. (2022). Gender, metacognitive intervention, and dialogic interaction: EFL multimedia listening. System 104:102709.

Ary, D., Jacobs, L. C., Irvine, C. K. S., and Walker, D. (2018). Introduction to Research in Education. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Bozorgian, H. (2014). The role of metacognition in the development of EFL learner’s listening skill. Int. J. Listen. 28, 149–161.

Bozorgian, H., Yaqubi, B., and Muhammadpour, M. (2020). Metacognitive intervention and awareness: listeners with low working memory capacity. Int. J. Listen. 1–14.

Chen, C. W. Y. (2017). Guided listening with listening journals and curated materials: a metacognitive approach. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 13, 133–146. doi: 10.1080/17501229.2017.1381104

Cheng, W. W. (2015). A case study of action research on communicative language teaching. J. Interdiscipl. Math. 18, 705–717.

Cooper, H., Robinson, J. C., and Patall, E. A. (2006). Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987–2003. Rev. Educ. Res. 76, 1–62. doi: 10.3102/00346543076001001

Cross, J. (2011). Metacognitive instruction for helping less-skilled listeners. ELT J. 65, 408–416. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccq073

Cross, J. (2015). Metacognition in L2 listening: clarifying instructional theory and practice. TESOL Q. 49, 883–892.

Cross, J., and Vandergrift, L. (2014). Guidelines for designing and conducting L2 listening studies. ELT J. 69, 86–89. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccu035

Field, J. (1998). Skills and strategies: towards a new methodology for listening. ELT J. 52, 110–118. doi: 10.1093/elt/52.2.110

Flanigan, A., Sudbeck, K., Beavers, J., McBrien, S., and Sierk, J. (2016). The Nebraska Educator, Volume 3: 2016 (Complete Issue).

Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: a new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry. Am. Psychol. 34, 906–911. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.906

Goh, C. (1999). How much do learners know about the factors that influence their listening comprehension? Hong Kong J. Appl. Linguist. 4, 17–42.

Goh, C. (2008). Metacognitive instruction for second language listening development theory, practice and research implications. RELC J. 39, 188–213. doi: 10.1177/0033688208092184

Goh, C., and Taib, Y. (2006). Metacognitive instruction in listening for young learners. ELT J. 60, 222–232. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccl002

Goh, C. C. (2000). A cognitive perspective on language learners’ listening comprehension problems. System 28, 55–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2007.04.002

Goh, C. C. M., and Vandergrift, L. (2021). Teaching and Learning Second Language Listening: Metacognition in Action. London: Routledge.

Graham, S. (2006). Listening comprehension: the learners’ perspective. System 34, 165–182. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2005.11.001

Graham, S., and Macaro, E. (2008). Strategy instruction in listening for lower-intermediate learners of French. Lang. Learn. 58, 747–783.

Hasan, A. S. (2000). Learners’ perceptions of listening comprehension problems. Lang. Cult. Curric. 13, 137–153.

Imhof, M. (2000). “How to monitor listening more efficiently: meta-cognitive strategies in listening,” in Paper Presented at the International Listening Association Convention, Virginia Beach, VA.

Imhof, M. (2001). How to listen more efficiently: self-monitoring strategies in listening. Int. J. Listen. 15, 2–19. doi: 10.1080/10904018.2001.10499042

Jerrim, J., Lopez-Agudo, L. A., and Marcenaro-Gutierrez, O. D. (2019). The relationship between homework and the academic progress of children in Spain during compulsory elementary education: a twin fixed-effects approach. Br. Educ. Res. J. 45, 1021–1049. doi: 10.1002/berj.3549

Jerrim, J., Lopez-Agudo, L. A., and Marcenaro-Gutierrez, O. D. (2020). The association between homework and primary school children’s academic achievement. International evidence from PIRLS and TIMSS. Eur. J. Educ. 55, 248–260. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12374

Kemp, J. (2009). The listening log: motivating autonomous learning. ELT J. 64, 385–395. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccp099

Maftoon, P., and Fakhri Alamdari, E. (2020). Exploring the effect of metacognitive strategy instruction on metacognitive awareness and listening performance through a process-based approach. Int. J. Listen. 34, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/10904018.2016.1250632

Martin, I. A. (2020). Pronunciation can be acquired outside the classroom: design and assessment of homework-based training. Modern Lang. J. 104, 457–479. doi: 10.1111/modl.12638

McDonough, J., and McDonough, S. (1997). Research Methods for English Language Teachers. London: Arnold.

Namaziandost, E., Neisi, L., Mahdavirad, F., and Nasri, M. (2019). The relationship between listening comprehension problems and strategy usage among advance EFL learners. Cogent Psychol. 6:1691338. doi: 10.1080/23311908.2019.1691338

Ozcelik, H. N., Van den Branden, K., and Van Steendam, E. (2019). Listening comprehension problems of FL learners in a peer interactive, self-regulated listening task. Int. J. Listen. 1–14. doi: 10.1080/10904018.2019.1659141

Ozcelik, H. N., Van den Branden, K., and Van Steendam, E. (2020). Alleviating effects of self-regulating the audio on listening comprehension problems. Int. J. Listen. 1–16. doi: 10.1080/10904018.2020.1788946

Rajab, S. Y., and Nimehchisalem, V. (2016). Listening comprehension problems and strategies among Kurdish EFL learners. Iran. EFL J. 12, 6–27.

Renandya, W. A., and Hu, G. (2018). “L2 listening in China: an examination of current practice,” in International Perspectives on Teaching the Four Skills in ELT, eds A. Burns and J. Siegel (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 37–50. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-63444-9_3

Schraw, G. (2006). “Knowledge: structures and processes,” in Handbook of Educational Psychology, eds P. A. Alexander and P. H. Winne (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum), 245–263. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.771640

Tanewong, S. (2018). Metacognitive pedagogical sequence for less-proficient Thai EFL listeners: a comparative investigation. RELC J. 50, 86–103. doi: 10.1177/0033688218754942

Tauroza, S., and Luk, J. (1997). Accent and second language listening comprehension. RELC J. 28, 54–71. doi: 10.1177/003368829702800104

Vandergrift, L. (2003). From prediction through reflection: guiding students through the process of L2 listening. Can. Modern Lang. Rev. 59, 425–440. doi: 10.3138/cmlr.59.3.425

Vandergrift, L. (2004). 1. Listening to learn or learning to listen? Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 24, 3–25. doi: 10.1017/S0267190504000017

Vandergrift, L., and Baker, S. (2015). Learner variables in second language listening comprehension: an exploratory path analysis. Lang. Learn. 65, 390–416. doi: 10.1111/lang.12105

Vandergrift, L., and Baker, S. C. (2018). Learner variables important for success in L2 listening comprehension in French immersion classrooms. Can. Modern Lang. Rev. 74, 79–100.

Vandergrift, L., and Cross, J. (2015). Replication research in L2 listening comprehension: a conceptual replication of Graham & Macaro (2008) and an approximate replication of Vandergrift & Tafaghodtari (2010) and Brett (1997). Lang. Teach. 50, 80–89. doi: 10.1017/S026144481500004X

Vandergrift, L., and Goh, C. (2012). Teaching and Learning Second Language Listening: Metacognition in Action. London: Routledge.

Vandergrift, L., and Tafaghodtari, M. H. (2010). Teaching L2 learners how to listen does make a difference: an empirical study. Lang. Learn. 60, 470–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9922.2009.00559.x

Veenman, M. V. J. (2011). “Learning to self-monitor and self-regulate,” in Handbook of Research on Learning and Instruction, eds R. Mayer and P. Alexander (London: Routledge), 197–218.

Veenman, M. V. J., Van Hout-wolters, B. H. A. M., and Afflerbach, P. (2006). Metacognition and learning: conceptual and methodological considerations. Metacogn. Learn. 1, 3–14. doi: 10.1007/s11409-006-6893-0

Wallace, M. P., and Lee, K. (2020). Examining second language listening, vocabulary, and executive functioning. Front. Psychol. 11:1122. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01122

Wallinger, L. M. (1997). Foreign Language Homework from Beginning to End: A Case Study of Homework Practices in Foreign Language Classes. Unpublished Manuscript. Williamsburg, VA: College of William and Mary.

Wallinger, L. M. (2000). The role of homework in foreign language learning. Foreign Lang. Ann. 33, 483–496.

Wang, L., and Renandya, W. A. (2012). Effective approaches to teaching listening: Chinese EFL teachers’ perspectives. J. Asia TEFL 9, 79–111.

Wenden, A. (1987). Metacognition: an expanded view of the cognitive abilities of L2 learners. Lang. Learn. 37, 573–594.

Zeng, Y. (2007). Metacognitive Instruction in Listening: A Study of Chinese Non-English Major Undergraduates. Ph.D. thesis. Jurong West: Nanyang Technological University.

Zimmerman, B. (2008). Investigating self-regulation and motivation: historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. Am. J. Int. Res. 45, 166–183. doi: 10.3102/0002831207312909

Appendix

Keywords: L2 listening, listening homework, metacognitive intervention, listening comprehension, diary

Citation: Bozorgian H, Muhammadpour M and Mahmoudi E (2022) Embedding L2 Listening Homework in Metacognitive Intervention: Listening Comprehension Development. Front. Educ. 7:819308. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.819308

Received: 06 December 2021; Accepted: 30 May 2022;

Published: 15 June 2022.

Edited by:

Matthew P. Wallace, University of Macau, Macao SAR, ChinaReviewed by:

Mohammad Hasan Razmi, Yazd University, IranEbrahim Fakhri Alamdari, Qaemshahr Islamic Azad University, Iran

Fidel Çakmak, Alanya Alaaddin Keykubat University, Turkey

Copyright © 2022 Bozorgian, Muhammadpour and Mahmoudi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Meysam Muhammadpour, bW11aGFtbWFkcG91ckBzdHUudW16LmFjLmly

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Hossein Bozorgian

Hossein Bozorgian Meysam Muhammadpour

Meysam Muhammadpour Elahe Mahmoudi

Elahe Mahmoudi