- 1Freelance Psychologist and Evaluator, Klagenfurt am Wörthersee, Austria

- 2Ombudsoffice for Children and Youths Carinthia, Klagenfurt am Wörthersee, Austria

- 3Department of Education Carinthia, Klagenfurt am Wörthersee, Austria

- 4Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Klinikum Klagenfurt am Wörthersee, Klagenfurt am Wörthersee, Austria

The effects that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on children and adolescents are versatile and vast. Reduced quality of life, emotional problems, social withdrawal, and symptoms of anxiety and depression up to suicidal ideations have been reported in numerous studies. They mainly use self-assessment, quite a few use parental assessments. The focus of this study are the challenges for teachers and students as well as observable behaviors and burdens of students from the perspective of teachers during the phase of distance learning because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The online study was conducted in Carinthia/Austria in March and April 2021. 1,281 teachers (29% response rate) from the 5th to the 13th grade participated. The significantly increased workload, the blurring of work and free time as well as the increased physical and mental demands are the largest challenges for the teachers. More than half of the students showed a significant drop in performance, reduced concentration ability and reduced motivation to learn from the perspective of the teachers. Assumed is a critically increased media use. Next to social withdrawal, one can also perceive symptoms of anxiety, depression, or physical ailments. Because of the external assessment through teachers the results are not directly comparable with international studies. However, they do show to the same degree the urgency of preventive and secondary preventive resp. measurements as well as easily accessible possibilities for support for teachers and students. Teachers have a high sensitivity to peculiarities of students and are a valuable source of information. The required performance of the students should be critically analyzed adequately according to the current situation and adapted.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has been described as a “unique multidimensional and potentially toxic stress factor for mental health,” which has had a particularly strong influence on children and adolescents due to its interruption of social contacts—which are of eminent importance for the psychosocial development (Brakemeier et al., 2020). Good living conditions, maintaining work, and exercises have been proven as protective factors. However, it seems that the lockdowns had a stronger influence on the everyday life of young people then on the one of older people (Moreira et al., 2021). Although childhood and adolescence are a vulnerable phase anyway due to its manifold levels of development during which there is an increased vulnerability for the development of mental disorders (Brakemeier et al., 2020).

Especially for children and adolescents with special needs (for example, after traumatic experiences, with disabilities, from families with low socio-economic status, with existing mental problems or migratory background) the pandemic phase is a particular challenge and danger. Social withdrawal and economical pressure burden the parents which also endangers children and adolescents (e.g., danger of child abuse). At the same time, the emergency services were only limited available during the COVID-19 pandemic (Fegert et al., 2020).

Numerous international studies point out strong effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. In May 2020, the majority of children and adolescents (71%) in Germany felt burdened from the pandemic as well as the parents (75%). Almost ⅔ found homeschooling exhausting, 83% missed contacts to friends, and 28% reported disputes in their families (Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2021a). The repeated survey in December 2020 as well as in January 2021 showed similar results, the health-related life quality kept decreasing. Emotional problems, symptoms of anxiety and depression as well as physical symptoms kept increasing (Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2021b).

Fifty five percentage of adolescents aged 14–20 in Austria showed symptoms of depression above the cutoff, 47% symptoms of anxiety, and 23% had difficulties sleeping (Pieh et al., 2021). Austrian senior high school students showed decreased pleasure in learning, and burdens because of the numerous preps on the computer, they showed increased problems compared to students from junior high school (Schober et al., 2020).

An Italian online study with almost 7,000 respondents (Uccella et al., 2021) showed significant effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on families. Close to ⅔ of the respondents showed mental impairments, 64% of children under the age of six and 73% aged 6–18 showed behavioral changes. Stress experienced by the parents because of COVID-19 correlated high with the behavioral changes of children/adolescents. The authors advocate for a focus on the health of children and adolescents, especially for groups with a high psychosocial risk (Uccella et al., 2021).

A review of 15 international studies about the weight changes of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic showed predominantly an increase in weight. On the one hand because of the changed eating habits, on the other because of the decreased physical activity. Also in this context a connection between socio-economic status and nutritional as well as movement behavior was shown (Stavridou et al., 2021). Often, a reduction in movement is accompanied by an increase in smartphone use. Problematic smartphone use can be accompanied by symptoms of anxiety and depression. It can be seen as a maladaptive coping strategy as well as an indicator for mental symptoms (Augner et al., 2021).

The Co-SPACE study from Great Britain showed - through parental assessment - an increased mental load and peculiarities in the behavior of children and adolescents aged 4–16 in the phase of an intensified lockdown. Sixty percent of parents declared that they cannot combine the needs of the children and the demands of work sufficiently. Even stronger affected were single parents, families with low socio-economic status, and children/adolescents with special needs (e.g., developmental disorders). There was no improvement of the mental health symptoms after the reduction of the restrictions in these families—compared to the overall sample (Creswell et al., 2021). A Chinese study among college students at five universities after reopening due to COVID-related closures also showed 15% of them with symptoms of anxiety and 32% with symptoms of depression (Ren et al., 2021).

Similar results are reported from the US, increased stress symptoms were shown due to social isolation, financial insecurity, and interrupted routines. The burdens led to mental symptoms, self-injuring behavior, and up to suicidal thoughts or suicide attempts. There was an increase of 24% in the group from 5 to 11 years in mental health related emergency departments. In the group from 12 to 17 years the increase was 31% and the suicide attempts increased about 39%. Next to an increased prevention, the demand is on trainings for teachers as well as the increase of supporting staff with trauma specialization. Additionally, evidence-based social and emotional learning programs should be offered (Evans, 2021).

A survey on 2,447 pedagogists in Germany showed the biggest challenges were the insufficient digitalization, the participation of all students, and their motivation. The evaluation of learning progress was found to be difficult (Schneider et al., 2021).

A study of 21 teachers in Switzerland showed a moderate to high general well-being, but because of the pandemic the occupational well-being decreased. Mental stress was created due to an increased workload, few experiences in online teaching, the feeling of not being sufficiently competent, and the multiple burdens of a problematic compatibility of work and family. The effects were less with stable persons, people with a higher resilience, available coping strategies, and clear working structures (Hascher et al., 2021).

Principals have a special role in these times as well since they have a particular role in the process of digital transformation. A qualitative study with 89 teachers in Turkey investigated digital leadership (Karakose et al., 2021c). Most participants rated the support of the school principals regarding digital transformation positively, the effort to create an effective digital learning environment was noticeable. Nonetheless, opposite trends were shown when promoting digital transformation could not take place due to a traditional understanding or due to lacking infrastructure. Next to technical and financial prerequisites the school principals need to be committed. The analysis showed three essential components of digital leadership: technology usage, managerial skills, and personal skills (Karakose et al., 2021c). These challenges lead quite frequently to strains for school administrators especially among female and young persons. COVID-19 related anxieties were stronger among school principals, whereas a stronger manifestation of work-privacy-conflicts was shown with younger participants. The crisis-like situation has effects on all participants in the school system, which should be diminished by a proactive approach (Karakose et al., 2021a).

Most studies report significantly increased mental symptoms and decreased life quality for children and adolescents, but studies from Austria are only limited representative because of their high number of female students and students at higher schools. Next to self-assessments of the students’ numerous studies used the external assessment of the parents.

The starting point for this study was the increase in admissions for inpatient child psychiatry acute care during the COVID-19 pandemic (for example because of sleeping problems due to circadian dysrhythmia, depressive symptoms, eating disorders) as well as the information about increasing consultations based on severe psychiatric disorders from registered psychiatrists for children and adolescents. The well-known increase in incidence of mental symptoms or disorders in Austria were primarily referring to students at higher schools or adults. An estimation for the compulsory school level was not reliably possible. Furthermore, the self-assessment of students aged 10–14 was forgone, since it would have been highly likely that it would have come to a biased sample due to the necessary declaration of consent from the parents.

Aim of the Study

The aim of the study is the detection of challenges and need for support for students and teachers in the period of distance learning during the lockdowns.

The psychosocial well-being of the students and possible mental symptoms during the phase of distance learning was externally assessed by the teachers and compared to results of studies with self-assessment or external assessment by the parents. Additionally, observed behavioral changes in online lessons from the perspective of the teachers was inquired.

Materials and Methods

External assessments by the teachers were chosen due to the young age of the students’ cohort, about ⅔ of them were aged 10–14. Questioning students below the age of 14 would require the written consent of the parents. This would have been an additional administrative burden in times of distance learning and during lockdowns. Furthermore, a representative sample would not have been secured this way since contacting a part of the parents was problematic according to the education authority.

It was supposed that especially the class teachers (CT—form/homeroom teachers) know their students well and can judge changes well accordingly, the other teachers were asked to give a global assessment over all classes. The method of external assessment by the teachers is appropriate for collecting behavioral changes of the students while learning or in online lessons. A distorting effect would rather have to be expected if students did a self-assessment.

Standardized procedures for external assessment could not be used because of the assessment of a general perception of behavioral changes and symptoms of a class or group of students, because those are always referring to individuals. Accordingly, the questionnaire was constructed based on study results on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on students in which mainly self-assessments of the children and adolescents or the external assessments by the parents were used. Additionally, specific questions about distance learning during the lockdowns were used.

The questionnaire consists of eight parts:

⁃ Information about Pedagogical Work (part A; 7 Items): information about schools, school district, the classes, the number of students, and about function (class teacher, teacher, principal)

⁃ Changes and Challenges for work as a Teacher and changes for all Students due to Lockdowns/Homeschooling (part B; 2 open questions with three text fields each)

⁃ Communication with Students and Parents during the COVID-19 Pandemic (part C, 9 Items): modality of contact, availability of parents, frequency and quality of contact

⁃ Observation of Changes of Students in Class (part D; 10 Items): mental state, learning motivation, persistence/performance, self-responsibility/self-organization, level of knowledge (compared with the target status without COVID-19 pandemic)

⁃ Availability and Problems of Students (part E; 4 Items): amount of unavailable students during homeschooling, amount of students without psychosocial problems and without learning problems as well as annotations to that

⁃ Perception of Impairments of Students‘ Mental Health (part F, 10 Items): anxiety, depressive symptoms, physical problems, excessive media use (reported), increased substance abuse, social withdrawal (loss of friendships), sleeping problems, noticeable weight change, suicidal ideations (manifestations), self-injury

⁃ Estimation of the Need of Support for Students and Teachers (part G, 6 Items): two open questions with three text field each

⁃ Free-Text Box for the Teachers (part H, 1 open question).

The questionnaire was adapted to correct items that could have been misunderstood and to incorporate missing aspects of the survey after a pilot testing with 61 teachers.

Participants

The target group of the study were all teachers (N = 5,194) from the 5th to the 13th school year in the Austrian state Carinthia. 1,500 teachers took part, the response rate was at 28.9%, but 219 cases were excluded from the questioning due to a premature abortion. The sample for analysis (n = 1,281) is assembled by 456 class teachers, (35.6%), 772 teachers (60.3%), and 53 principals (4.1%). The data of the teachers and the principals is summarized for the presentation of results (T). More than ⅔ of the class teachers (67.8%) knew the class before the begin of the COVID-19 pandemic, 56.7% of the teachers knew the most students, 28.2% some of them, and 15.1% did not know the students before the pandemic at all. For better anonymization no socio-demographic data was collected. All school levels and types of schools are sufficiently represented in the sample, but the response rate was lower in rural than in urban areas. The class size of the investigated school levels is 33 students maximum.

Data Collection

The data was obtained through an online study via links, which beforehand were sent to the school administrators requesting to forward it to all teachers. The participation was voluntary, and anonymity was ensured. Items with close-ended questions were set on “obligatory,” the open-ended questions in text fields were non-obligatory. Two weeks after the dispatch the Department of Education (Bildungsdirektion) sent a reminder to all school administrations requesting forwarding again.

The questionnaire was accessible from 16th of March to 7th of April 2021. At that time classroom training and distance learning were alternating after 1 month of pure distance learning (“shift operation”—each 50% of a class were in classroom training for 2 days per week, 1 day all students were in distance learning). Already in 2020, the teaching in Austria was characterized by alternating phases of distance learning, “shift operation,” and classroom training.

Data Analysis

The data of the online inquiry was analyzed with descriptive statistics by SPSS (IBM Corp., 2017). Reliability of the close-ended questions was examined by Cronbach’s Alpha. The internal consistency of the items for the communication with the parents was α = 0.79 (part C), of the items for the behavior in teaching (part D, 4 items) α = 0.765, if the item for the quality of interpersonal contact is taken off the scale. The reliability for the items for the observation of changes from students while teaching (part D, 6 items) was satisfactory at α = 0.901 as well as the reliability for the items for the estimation of impairments of students’ mental health (α = 0.865, part F, 10 items). Arithmetic means were calculated for the parts of the questionnaire with satisfactory reliability. Due to the different composition of questionnaires for class teachers (CT) and teachers (T) single scores are presented separately by percentages.

Responses to open-ended questions were summarized following the qualitative content analysis by Mayring (2002) with MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019). The answers were mostly in key points or enumerations, some teachers wrote longer texts. Two researchers inductively developed categories from this text material and presented codings in regard with content and frequency. Additionally, exact quotes are cited as examples. In the course of this paper only excerpts of these results can be presented.

Results

Communication between teachers and students took place mostly three times per week via the learning platform of the school (66.7%) or through online live teaching (42.6%). Often used was communication by email (37.4%), much fewer social media (17.3%), personal contacts (15.3%), or contact by phone (14.4%).

86% of class teachers and 74% of teachers estimated the frequency and quality of the contact to the parents (part C), the results of both groups are comparable. More than half of each stated that frequency and quality of the contact stayed the same in comparison to before the lockdown, but 22% thought frequency and 29% quality of the contact was somewhat worse or much worse than before. Availability of the parents was considered to have stayed the same (68%) or better (12%) than before the lockdowns. Though 20% stated it was somewhat worse or much worse than before.

Challenges for Students

Ninety five percent of teachers answered the open question, which challenges for students were shown because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Three free-text boxes were offered for this (part B). As well as with the questions about the challenges for teachers only excerpts can be given here, since due to the numerous statements of the teachers more than 2,600 entries occurred.

Reduction of Motivation and Performance

The impression of several teachers is, that the students are overtired and hard to motivate. Adding to this would be the directive, that students can move up a level even with a “not sufficient” (“F”) grading. They lack time management, and some students make the impression of being physically present but without (being able to) participating in class. An excited anticipation to “normal” lessons can be observed.

“Many students do not have a circadian rhythm anymore, they are overtired, many have sleep disorders, mental problems have worsened with some, motivation has changed or does not exist anymore resp.”

“Increasing loss of motivation, work-attitude leaves a lot to be desired, constant reminding to receive [their] tasks …”

More Severe Loss of Performances With Previously Weaker Students

Very often is expressed, that previously good students could keep their performance or even improve it during homeschooling, while with weak students there is a significant reduction in performance.

“Positive: some very engaged and creative students, who are really good with the digital work. Negative: many are at home and during class barely to motivate, especially the weaker students suffer from this situation (in my opinion) – The gulf between high- and low-performance students is sadly increasing.”

“Concentration during online lessons (and also increasingly in the present lessons) has severely sunken (often students have glassy eyes and are somewhere else in their head).”

Social Withdrawal

Often teachers describe the perception, that students pull back, enthusiasm is missing, and the “shinning eyes” are not seen anymore. There is a depletion of communication and social competence, friends also lose touch due to the division of classes in subgroups.

“The isolation. Almost all students are telling about how much they miss their friends. When students regularly tell me in the morning how happy they are that they can be at school with us, then this is a great compliment on the one hand. On the other, it is a huge warning signal.”

“Social contacts are missing: to develop in a group, trying identities, dealing with conflicts, day-to-day life and negotiating, getting quick and accessible help.”

“The social contact is getting lost. It follows, that even though students can communicate via computer/cell phone, this is a numbed manner of communication. Empathy in certain situations, social learning in the groups, this is getting more and more lost. Class community is just a hollow phrase now.”

Observation of Mental Burdens or Symptoms

Numerous teachers observed that single students are pulling back into their “snail shell,” seem apathic or depressive, are sad and show fear of the future. The mood is sinking due to the continuation of the pandemic. Several students seem friendly and polite, but one gets the impression, that they are low in spirits and more afraid than before the pandemic.

“Loss of circadian rhythm, depression, eating disorders, isolation, self-inflicted injuries, suicidal thoughts, severe increase in alcohol and drug abuse.”

“An overload regarding the autonomous mastery of the tasks, a stronger pulling back, and an increasing absence of communication. The missing of social contacts with peers also has a noticeable negative effect.”

Positive Remarks

Students have been gaining digital competence because of the distance learning. Some students discover new interests due to the self-management.

Challenges for Teachers

Ninety five percent of participants answered the question about the change in teaching since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Bureaucratic Burden

Very often were statements about the increased burden, regarding the preparation of learning material for distance learning, additional burdens through the supervision of parallel groups. Also, teachers feel that lessons are becoming more of a “monitoring.” That frustrates many of the surveyed teachers, since they feel they can get there work done only with unpaid additional work.

“You do not teach anymore, you just administrate, questionnaires, consent forms, running behind undone tasks, calling after the parents, writing lists.”

“Immense (unpaid) additional work due to more corrections, more contact to parents and also to students in my free time and on weekends.”

“Thoughts and worries are more with the students! Overload for us due to constant computer trainings, various programs and passwords (lessons at 2 schools!), love of the profession is getting lost, because everything is more and more about statistics, computers and their software!!!!!”

Missing Social Contacts and Collective Learning

Some teachers say that they cannot judge the learning progress and participation as well as in normal classes. The relationship building toward new students is different and more complex. It has come to a social distance, especially children/adolescents from educationally disadvantaged families are not tangible anymore and motivating students has become more difficult via distance learning.

“The current situation is utterly difficult for me as teacher and class teacher, since I want to support the community, the joy about learning, and give freedom to the urge to move of the students! All this is impossible now!!!”

Constant Availability – Blurring of Privacy and Work

Many teachers fell that they have to be constantly available, they are getting contacted by parents or students via mail or phone to unusual times. From the parents they perceive either an excessive expectation or disinterest. In some cases, it seems parents are taking over the tasks of the children/adolescents or want to mingle into the lessons.

“There is no work schedule with fixed times anymore, but one has to be available 24/7 for students and parents.”

“The constant availability! Before there was school and private life. One gets emails from the students until late in the night due to the numerous emailing and the constant questions or the missing tasks and the uncertainties of the students.”

“Increased digital communication with the students at every hour!!!! To show them that they are not alone! Sometimes also personal matters!”

Physical and Mental Burdens

There are physical as well as mental burdens because of the changed working conditions. The increased computer work is affecting the muscular system and posture, the wrists, and the eyes. Additionally, some name symptoms of exhaustion, feel insecure in their communication or feel that they are called upon in several roles next to knowledge transfer.

“Sometimes I feel very close to my limit. I sleep badly and wake up and cannot fall back asleep.”

“Teacher as psychologist, social worker, therapist, animateur… Knowledge transfer is falling by the wayside.”

Positive Aspects

Not least should be mentioned that many teachers name positive aspects as well. Some parents are thankful for the work of the teachers and many children/adolescents perform very positively; they handle the new challenges well.

Observations of Changes in Learning

Between 92% and 95% of the teachers answered the questions about the behavior in class (part D). Assessed as a somewhat worse or a much worse were presentism (51%), punctuality (40%), finishing tasks/homework (55%), and the quality of contact (interpersonal level, trustful communication, 65%). But 10%–15% of the surveyed assessed these aspects as a somewhat better or much better than before the COVID-19 pandemic. These estimations were completed by comments. Those showed that the motivation of the students had diminished and that a non-professional exchange as well as social interactions between students and teachers would be important. Distance learning did not worsen a good relationship with the students, but existing problems were exacerbated because of the distance learning. Students who before already did not finish all tasks finished even less during the lockdown, in part due to the losing of a study routine.

Changes and Problems Regarding Learning

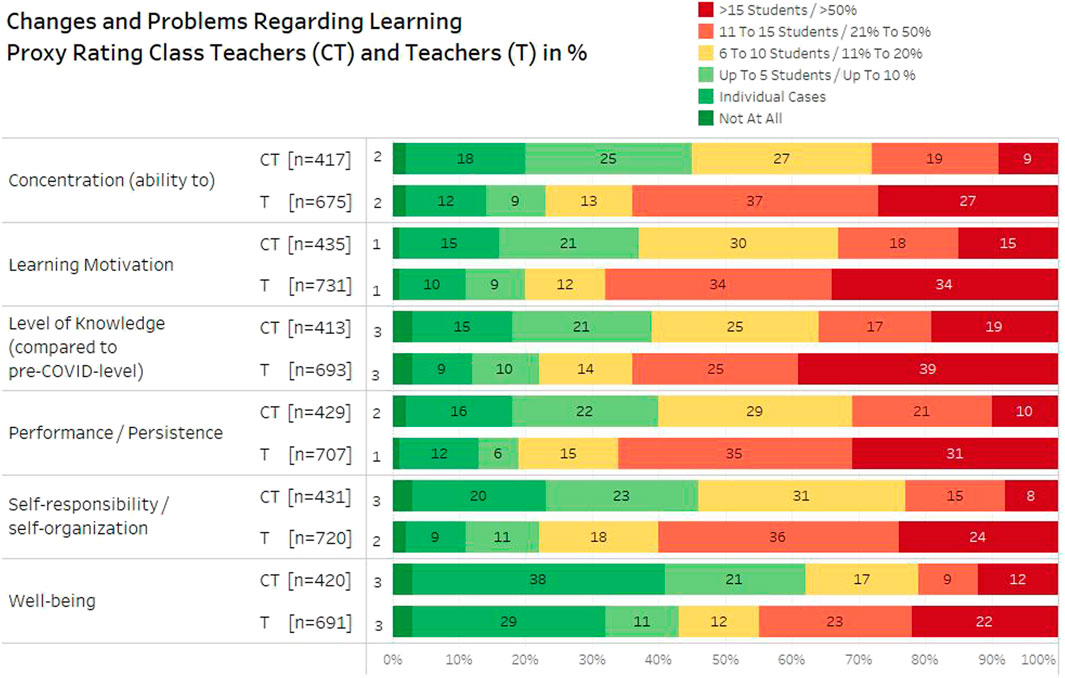

The questions regarding learning since the beginning of the school year 20/21 were collected through 6 items (part D). The estimations of class teachers (CT) were asked in numbers, the one of the teachers (T) in %. For the interpretation of the results the answer categories of the class teachers “6–10 students” till “>15 students” were summarized (that corresponds to about a share of 20% of students per class). For the answer categories of the teachers the manifestations 21% till 50% and >50% were summarized. Following is a juxtaposition of the estimations from the class teachers and the teachers which at least affected 20% of a class or the students resp.:

Problems in learning motivation (CT = 63%, T = 68%), level of knowledge (CT = 61%, T = 64%), performance/persistence (CT = 60%, T = 66%), concentration (CT = 55%, T = 64%), self-responsibility /self-organization (CT = 54%, T = 60%), and well-being (CT = 38%, T = 45%). From this it appears that class teachers just as well as teachers see problems for more than half up to ⅔ of the students concerning learning (Figure 1).

The respondents said that about 8% of the students were not reachable during the lockdown. The question, how many students would have no psychosocial problems was answered with ø 12 students by the class teachers (almost half the class), and teachers answered with 30%. Their particulars about learning problems were almost identical.

Mental Burdens of the Students Perceived by the Teachers

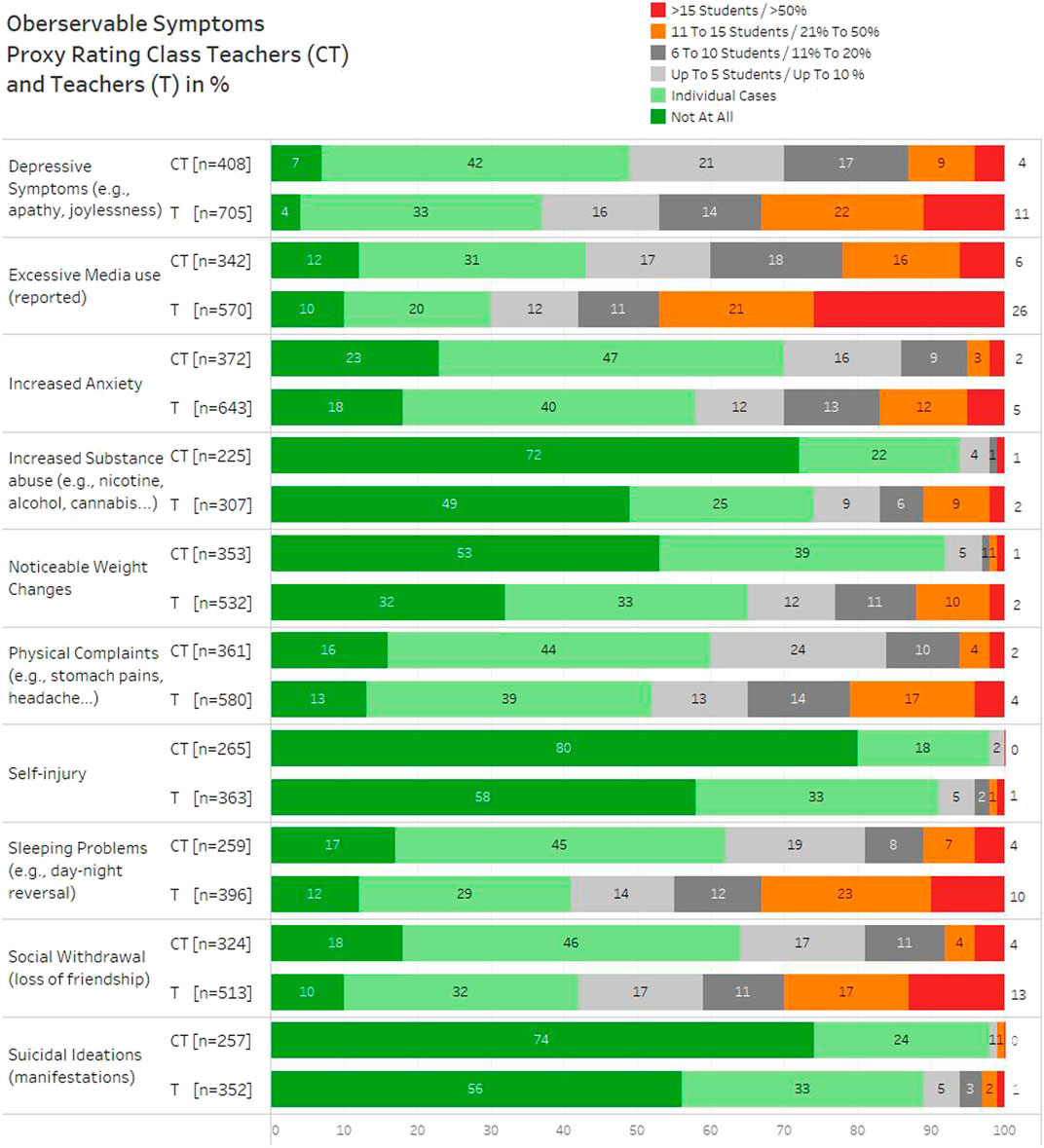

The estimation of students’ mental burdens was done on the basis of 10 items (part F). This was seemingly difficult for a part of the respondents, and they chose the option “I cannot judge.” This proportion was equally high among teachers (T) and class teachers (CT) for the most items. The tendency to choose the option “I cannot judge” was rarer in class teachers than in teachers: increased anxiety (CT = 13%, T = 13%), depressive symptoms (e.g., feeling glum, apathy, joylessness) (CT = 4%, T = 4%), physical problems (e.g., headache, stomach pain) (CT = 15%, T = 21%), excessive media use (reported) (CT = 20%, T = 23%), increased substance abuse (e.g., nicotine, alcohol, cannabis) (CT = 47%, T = 58%), social withdrawal (loss of friendships) (CT = 24%, T = 30%), sleeping problems (e.g., day-night reversal) (CT = 39%, T = 46%), noticeable weight change (CT = 17%, T = 28%), suicidal ideations (manifestations) (CT = 40%, T = 52%), and self-injury (CT = 38%, T = 51%).

As before, for the interpretation of the results the answer categories of the class teachers “6–10 students” till “>15 students” were summarized. For the answer categories of the teachers the manifestations 21% till 50% and >50% were summarized. Accordingly, the following symptoms affect at least 20% of a class or of the students: increased anxiety (CT = 14%, T = 17%), depressive symptoms (e.g., feeling glum, apathy, joylessness) (CT = 30%, T = 33%), physical problems (e.g., headache, stomach pain) (CT = 16%, T = 21%), excessive media use (reported) (CT = 40%, T = 47%), increased substance abuse (e.g., nicotine, alcohol, cannabis) (CT = 2%, T = 11%), social withdrawal (loss of friendships) (CT = 19%, T = 30%), sleeping problems (e.g., day-night reversal) (CT = 19%, T = 33%), noticeable weight change (CT = 3%, T = 12%), suicidal ideations (manifestations) (CT = <1%, T = 3%) and self-injury (CT = <1%, T = 2%). The most urgent and most frequent problem resp. seen by class teachers as well as teachers is excessive media use, followed by depressive symptoms, social withdrawal, and sleeping problems (Figure 2). Fourteen percent said that they had already been asked for advice from parents concerning excessive media use.

To the question how many students probably would need professional support due to mental problems, class teachers answered 2–3 students (about 10%) and teachers answered 14%.

Need for Support for Teachers and Students

At the end of the questionnaire there were two open questions about the need for support for teachers and students. For that, three free-text boxes were offered (part G).

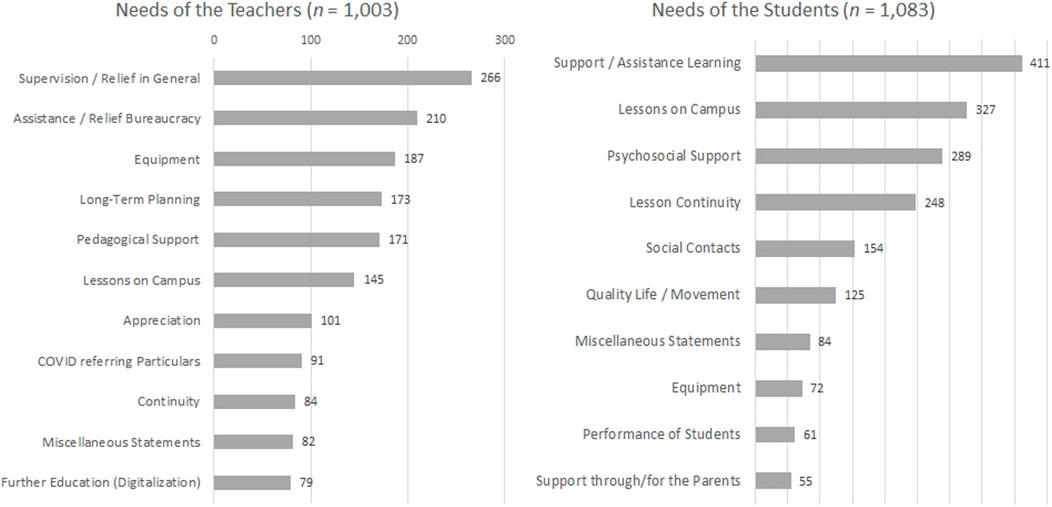

Need for Support for Teachers

One thousand and three teachers answered this question, 577 of them gave two answers, 241 gave three answers. This resulted in 1,821 passages which were summarized in 11 categories (Figure 3), and for which 1,589 codings were generated (double data was not considered). The most frequent wish was the one for relief (26.5%), in the form of supervision on the one hand, and on the other through the availability of school psychologists, school social work, mediators, and through a reduction of the increased burdens. One person said, “We need psychological help, nobody asks how WE are.” The teachers want to adequately handle evident mental problems of the students, but they also expect an accessible and competent place to go. Supervision and collegial interchange are named as very important for their own mental hygiene. Almost 20% hope for a relief from bureaucratic tasks which have been newly added because of the COVID-19 pandemic, e.g., conducting covid testing, and administration of materials. The wish for an adequate equipment was expressed by 17%, that affects the technical equipment in school (Wi-Fi, hardware, digital class material), but also support for the equipment of their home offices. Each 13.5% of the respondents wish for pedagogical support for example by reducing the size of the groups/classes or by additional teaching staff as well as a better long-term planning of the processes, since there were constant adaptions necessary due to the changing restrictions. The other categories show that the teachers are looking forward to an end of the changed working conditions (11.3%), that they want to get back to the former routine and continuity (6.6%), and that they wish for more appreciation for their work from society (7.9%).

Need for Support for Students

One thousand and eighty-three teachers answered this question, 603 of them gave two answers, 324 gave three answers. This resulted in 2,010 passages which were summarized in 10 categories and for which 1,826 codings were generated (double data was not considered).

A high percentage of teachers think it is necessary that there will be an additional support for learning (41%). This could take place by guided learning, special tuition, or individual assistance for students who are especially “in need.” The second most frequent wish was the one for classes on campus (33%), and in the category continuity (25%) a return to regular lessons in the sense of a “normal school life” is meant. Psychosocial support (29%) means school psychology, guidance counselors, school social work, as well as consultation and mentoring for students and their families. The category social contacts with peers (15%) includes statements about working together in school, about the “we-feeling,” talking opportunities or social contacts outside of school. Similar contents are in the category life quality/movement (12.5%), but here are concrete statements about sportive activities, about creative offers, or about active leisure activities (outside). The remaining categories were coded each by less than 10% of the respondents.

These open questions were complemented by a categorial question about existing offers of support. From the perspective of the teachers’ school psychology (36%), school social work (29%), supervision for teams (24%), youth coaches (23%), and guidance counselors (19%) are the most important offers of support.

Discussion

The challenges because of the COVID-19 pandemic are enormous and meanwhile long-lasting, they influence the everyday life of all people and lead to a decrease of life quality as well as an increase in stress and mental symptoms like anxiety, for example, among all age groups. Teachers and students are particularly affected by the effects of the pandemic because they immediately had to adapt to new forms of teaching, had to learn the handling of new corresponding tools, and they had to face an increased effort. On the one hand this phase was aggravated due to a lack of equipment, on the other due to a lack of experience and the complexity of distance learning (Karakose et al., 2021a).

The aim of this online study with 1,281 teachers was to record the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the work of the teachers as well as an external assessment of the effects on the students. The method of externally assessing the students by the teachers proofed as practical. Even though there is probably some fuzziness due to the assessment of school classes instead of single students, an estimation of the overall group in a region can be derived.

For the teachers, challenges and need for support was identified. For the students, behavioral changes, and indications for mental symptoms as well as need for support was identified.

The results show considerable effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on teachers and students. The results of the external assessment of the students by the teachers will be discussed in context with the results of studies with self-assessment.

The relatively pleasing response rate of the online questionnaire of the teachers – in times of a significantly increase workload due to the COVID-19 pandemic—supports the assumption that this group wants to be heard and that it has something to say to the political decision-makers, the education organizations as well as to society and parents. Teachers are confronted with numerous challenges regarding the lessons (changing the contents to distance learning, technical problems, the blurring of the border between private and work life) and with the changed behaviors of the students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Numerous free-text box comments in the study make the enormous work load visible, which has emerged for example due to the division of classes, the increased computer working time, and the almost constant availability, all of which led to a reduction of free time. Not only the amount of work has increased, but also the mental stress. Teachers in Germany as well described the social tasks due to teaching in times of the COVID-19 pandemic as particularly challenging: not “to lose” a student, to keep up motivation for learning, and assessing the performance accordingly (Schneider et al., 2021). These challenges have led to a decrease in professional well-being especially for teachers with low resilience and fewer available coping strategies (Hascher et al., 2021).

Most of the respondents of this study mentioned missing social contacts, among colleagues but also with and among students. As documented by numerous studies, social withdrawal is a particular challenge for students, especially in vulnerable groups (Creswell et al., 2021; Stavridou et al., 2021; Uccella et al., 2021). This aspect was not sufficiently considered for the construction of the questionnaire, but because of the many free-text comments tendencies became visible. Little changed for good students, but significant deteriorations were shown with already weaker students. There was not enough social learning, study matter could not be sufficiently consolidated, and the motivation is decreasing by the continuing pandemic.

Teachers see a decreased ability to concentrate with more than half of the students, a worse perseverance, a lower motivation, and less level of knowledge than before the COVID-19 pandemic. Self-responsibility and self-organization are deemed problematic for more than the half and the well-being is estimated to be lower. These results are compliant with a study from Germany, after which ⅔ of students found homeschooling exhausting, and the majority of parents and students were burdened (Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2021a).

These problems have to be seen with the mental state of the students too. Adolescence with its adaption requirements is anyway a vulnerable and risky phase for young persons (Brakemeier et al., 2020), since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic young people now have not only the challenges of learning but also possible symptoms of anxiety or depression, even suicidal thoughts, to cope with. While usually at least in part one can count on their peer group, since the pandemic isolation dominates, and not least because of this the media use increases critically. Links between media use and depression have been reported in several studies (Augner et al., 2021), and are also one of the most frequent observed symptoms or areas of concern resp. in this study.

Next to excessive media use (CT: 40%, T: 47%) teachers see sleeping problems (CT: 19%, T: 33%), and social withdrawal (CT: 19%, T: 30%) as the most severe impairments. The estimations of the part of students with anxiety symptoms (CT: 14%, T: 17%) and depressive symptoms (CT: 30%, T: 33%) are in accordance with the result of a survey of college students at the reopening of universities after the lockdown in China (Ren et al., 2021). Some studies though assume a much higher proportions of affected students (Pieh et al., 2021). Although, due to the different assessments which were used comparisons are not permitted.

In international studies life quality is also estimated as being significantly lowered for children and adolescents (Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2021a), but this was not part of this study. The special feature of this study is the external assessment of school classes or school groups whereas in conventional studies estimation or self-ratings of individuals are used. On the other hand, assessments of over 1,200 teachers could be collected this way, which in total observed more than 20,000 students, if one assumes an average of 25 students per teacher (with possibly overlapping observations).

The results show that most teachers think of themselves as capable to give a rough estimate about the mental state of their classes or students resp. The necessity of having a special attention on the mental health of children and adolescent is seen as equally urgent by the responding teachers as by international experts (Evans, 2021).

The open questions are a valuable supplement to the standardized questions. It makes clear how strong the effects were especially on vulnerable student groups. From the results measurements are derived how these students as well as the teachers can be supported in the future. Affected students should get quick and accessible possibilities for support for learning, but especially also in a psychosocial respect. Teachers should also get the demanded offers of support in a timely manner. In sum, there is a high sensitivity of the teachers for the state of students and their estimations are a valuable resource for the Department of Education (Bildungsdirektion) and the responsible health authorities.

Which are the practical implications which can be derived from these results? Now the political decision-makers have to take the reported conditions in schools seriously and improve them. To ensure teaching without limitations in the next phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, the technical prerequisites have to be established in the necessary extend on the one hand. On the other, a sustainable digital transformation is necessary.

Principals will have a particular importance since next to organizing of supporting measurements as relief or trainings, for example, they can also be a motivational factor for a creative and effective learning environment.

Psychosocial support for students and teachers at the schools needs to be urgently increased. Moreover, the up to now practiced performance review of the students needs to be questioned. Since especially students are subjected to particular challenges, they need a great deal of abilities and skills as well as self-motivation to cope with the current school requirements. But concentration, resilience, and motivation are decreased due to reduced possibilities for sport, for enjoying free time, and the restricted peer contacts. Thus, performance reviews should be more orientated on the current performance capability of the students instead on the, up to now undoubtedly and sensible, requirements.

Limitations

The response rate of the teachers was satisfactory, but a biased sample cannot be excluded. Teachers who, for example, are especially interested or attentive could have taken part in the questionnaire. The design of the questionnaire was challenging since standardized instruments refer to individuals. But object of this study was an entire school class or a group of students of one teacher resp. Thus, different scales for class teachers and teachers were created which cannot be exactly compared with each other. Thus, there is only a very limited comparability with other studies, which is also because for the estimation of the mental burden of students more often the parents are used than the teachers. Accordingly, results should be interpreted with care. Moreover, concrete burdens of the teachers were not collected in this study due to the length of the questionnaire. For future studies, it would be interesting to research under which conditions lower or stronger burdens such as fatigue or COVID-19 related anxieties, for example, are shown and to what extent burdens of students and teachers are linked. Optimally, these studies should be conducted with taking into account relevant sociodemographic data in the form of a regular monitoring. For a deep insight in the living environment school a study with mixed-methods design would be desirable as it is recommended by Karakose et al. (2021b).

Conclusion

The living environment school has been hit particularly hard by the COVID-19 pandemic. The largest challenges for the teachers in the phases of the lockdowns and of distance learning are the bureaucratic load, lacking social contacts and joint learning experiences, the merging of work and private life, and physical as well as mental burdens. The most urgent needs are therefore supervision, a relief by support in the administration, a sufficient technical equipment as well as a better predictability of school life through clear structures and explicit guidelines by the responsible authorities.

The students showed considerable signs of impairments of mental health as well as critical behavioral changes with regard to dealing with work assignments, attendance, punctuality, and learning motivation. Mostly impaired during the time of distance learning are the social contacts within the peer group, but frequency and quality of contact between teachers and students are also considerably reduced. These challenges meet educationally disadvantaged children and adolescents from families with a rather lower socioeconomical status particularly hard.

Teachers need a supporting environment next to an appropriate technical equipment for an efficient teaching so that they can keep effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on themselves and on the students to a minimum. A special significance is attributed to the principals here since they can organize supporting interventions such as a relief in workload or trainings as well as being a motivational factor for a creative and effective learning environment.

In the medium term a withdrawal of the requirements on the performance of students as an adjustment to the situation is necessary in order to avoid additionally pushing students to hard in this vulnerable development period anyway. A critical revision and reduction of the performance requirements is urgently needed due to the long duration and the expected after-effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because they include in the original qualitative part from case to case very personal statements about schools, which could allow for identifications of the respondents. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Birgit Senft: b2ZmaWNlQHN0YXRpc3RpeC5hdA==.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank all teachers for taking part in the study despite the difficult conditions during the COVID-19-pandemic in the springtime of 2021. We want to thank the state of Carinthia, the Ombudsoffice for Children and Youths in Carinthia, and the Department of Education for financing and supporting the conduction of this study.

References

Augner, C., Vlasak, T., Aichhorn, W., and Barth, A. (2021). The Association Between Problematic Smartphone Use and Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression-A Meta-Analysis. J. Public Health 28, 6377512. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdab350

Brakemeier, E.-L., Wirkner, J., Knaevelsrud, C., Wurm, S., Christiansen, H., Lueken, U., et al. (2020). Die COVID-19-Pandemie als Herausforderung für die psychische Gesundheit. Z. Klin. Psychol. Psychother. 49 (1), 1–31. doi:10.1026/1616-3443/a000574

Creswell, C., Shum, A., Pearcey, S., Skripkauskaite, S., Patalay, P., and Waite, P. (2021). Young People’s Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 5 (8), 535–537. doi:10.1016/s2352-4642(21)00177-2

Evans, A. C. (2021). Putting Kids First: Adressing COVID-19’s Impacts on Children: Written Testimony. Available at: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2021/09/covid-19-children-testimony.pdf (Accessed November 1, 2021).

Fegert, J. M., Vitiello, B., Plener, P. L., and Clemens, V. (2020). Challenges and Burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic for Child and Adolescent Mental Health: A Narrative Review to Highlight Clinical and Research Needs in the Acute Phase and the Long Return to Normality. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 14, 20. doi:10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3

Hascher, T., Beltman, S., and Mansfield, C. (2021). Swiss Primary Teachers’ Professional Well-Being During School Closure Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 12, 687512. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.687512

Karakose, T., Polat, H., and Papadakis, S. (2021c). Examining Teachers' Perspectives on School Principals’ Digital Leadership Roles and Technology Capabilities during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 13, 13448. doi:10.3390/su132313448

Karakose, T., Yirci, R., and Papadakis, S. (2021a). Exploring the Interrelationship Between COVID-19 Phobia, Work-Family Conflict, Family-Work Conflict, and Life Satisfaction Among School Administrators for Advancing Sustainable Management. Sustainability 13, 8654. doi:10.3390/su13158654

Karakose, T., Yirci, R., Papadakis, S., Ozdemir, T. Y., Demirkol, M., and Polat, H. (2021b). Science Mapping of the Global Knowledge Base on Management, Leadership, and Administration Related to COVID-19 for Promoting the Sustainability of Scientific Research. Sustainability 13, 9631. doi:10.3390/su13179631

Pieh, C., Plener, P. L., Probst, T., Dale, R., and Humer, E. (2021). Assessment of Mental Health of High School Students During Social Distancing and Remote Schooling During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Austria. JAMA Netw. Open. 4 (6), e2114866. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.14866

Ravens-Sieberer, U., Kaman, A., Otto, C., Adedeji, A., Napp, A.-K., Becker, M., et al. (2021a). Seelische Gesundheit und psychische Belastungen von Kindern und Jugendlichen in der ersten Welle der COVID-19-Pandemie - Ergebnisse der COPSY-Studie. Bundesgesundheitsbl 64, 1512–1521. doi:10.1007/s00103-021-03291-3

Ravens-Sieberer, U., Kaman, A., Erhart, M., Otto, C., Devine, J., Löffler, C., et al. (2021b). Quality of Life and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents During the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results of a Two-Wave Nationwide Population-Based Study. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 12, 1–14. doi:10.1007/s00787-021-01889-1

Ren, Z., Xin, Y., Ge, J., Zhao, Z., Liu, D., Ho, R. C. M., et al. (2021). Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on College Students After School Reopening: A Cross-Sectional Study Based on Machine Learning. Front. Psychol. 12, 641806. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.641806

Schneider, R., Sachse, K. A., Schipolowski, S., and Enke, F. (2021). Teaching in Times of COVID-19: The Evaluation of Distance Teaching in Elementary and Secondary Schools in Germany. Front. Educ. 6. doi:10.3389/feduc.2021.702406

Schober, B., Lüftenegger, M., and Spiel, C. (2020). Lernen unter COVID-19-Bedingungen: Erste Ergebnisse - Schüler*innen. Studie "Lernen unter COVID-19-Bedingungen. Available at: https://lernencovid19.univie.ac.at/fileadmin/user_upload/p_lernencovid19/Zwischenergebnisse_Schueler_innen.pdf (Accessed November 1, 2021).

Silva Moreira, P., Ferreira, S., Couto, B., Machado-Sousa, M., Fernández, M., Raposo-Lima, C., et al. (20211910). Protective Elements of Mental Health Status During the COVID-19 Outbreak in the Portuguese Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 (4), 1910. doi:10.3390/ijerph18041910

Stavridou, A., Kapsali, E., Panagouli, E., Thirios, A., Polychronis, K., Bacopoulou, F., et al. (2021). Obesity in Children and Adolescents During COVID-19 Pandemic. Children 8 (2), 135. doi:10.3390/children8020135

Uccella, S., de Grandis, E., de Carli, F., D’Apruzzo, M., Siri, L., Preiti, D., et al. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 Outbreak on the Behavior of Families in Italy: A Focus on Children and Adolescents. Front. Public Health 9, 608358. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.608358

Keywords: Distance Teaching, Distance Learning, COVID-19, Mental Health, Teachers’ external Assessment, Explorative Study

Citation: Senft B, Liebhauser A, Tremschnig I, Ferijanz E and Wladika W (2022) Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children and Adolescents from the Perspective of Teachers. Front. Educ. 7:808015. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.808015

Received: 02 November 2021; Accepted: 04 January 2022;

Published: 11 February 2022.

Edited by:

Stamatios Papadakis, University of Crete, GreeceReviewed by:

Michail Kalogiannakis, University of Crete, GreeceTeresa Pozo-Rico, University of Alicante, Spain

Copyright © 2022 Senft, Liebhauser, Tremschnig, Ferijanz and Wladika. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Birgit Senft, b2ZmaWNlQHN0YXRpc3RpeC5hdA==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Birgit Senft

Birgit Senft Astrid Liebhauser2†

Astrid Liebhauser2† Ina Tremschnig

Ina Tremschnig Edith Ferijanz

Edith Ferijanz