94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Educ., 18 May 2022

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.790600

For over 50 years, psychology leaders have called for fundamental changes in how we undertake research, education, and community interaction. This paper provocatively argues the case for “why now, and how.” The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that psychology must contribute more to the wellbeing of local and global communities. We propose that a primary mechanism for doing so is by reinventing the undergraduate psychology program. This paper provides a stimulus to initiate international discussion of interconnected graduate capabilities, which we propose to be: Knowledge, Research Methods, Application of Knowledge to Personal, Professional and Community (Local, National, Global) Domains, Values and Ethics, Critical Thinking, Communication, and Cultural Responsiveness. Focusing on core aspects of psychology (Knowledge, Research Methods, Application) and more generic but evidence-informed capabilities is a unique formulation and should well serve graduates, employers, society, and the psychology discipline and profession in the uncertain “post-pandemic” era. We also propose psychological literacy as a promising unifying approach for psychology. Finally, we provide a “road-map” for curriculum renewal at international, national, and institutional levels, involving a consensus-seeking process (an extensive scholarly overview of the proposed capabilities is provided).

Leaders in the field of psychology learning and teaching have long called for a radical shift in how and what we teach. For example, Miller (1969) argued that although psychological scientists are not obliged to contribute to solutions to societal problems, as citizens they are obliged to contribute if their findings are of practical value. In particular, those with psychological knowledge should “give psychology away” (p.1071) through education within both classrooms and the public domain. Similarly, Halpern et al. (2010) argued that those with psychological knowledge should ensure that “policy makers and the general public… understand that the need to be psychologically literate is similar to being able to read or use numbers in thinking” (p.172). That is, Halpern et al. (2010) suggested that psychology education should become as mainstream as the “3R’s” [i.e., (r)eading, w(r)iting, and a(r)ithmetic], particularly as most societal problems relate to human behavior. Recently, Halpern and Dunn (2021, in press) have argued that in the age of unintentional misinformation and deliberate disinformation, false truths and fake news, the need for psychology education, including critical thinking, is particularly urgent.

Our provocation is this: For over 50 years, there have been calls, generally unanswered, to radically change the nature and outcomes of psychology education. We argue that the COVID-19 pandemic has provided us with an opportunity, in particular: (a) the sudden switch from classroom/blended to blended/online delivery, as well as cuts in higher education revenue, necessitates a rethink of educational delivery, and creates a culture of “change-mindedness”; (b) the pandemic exacerbated and highlighted social and economic inequities in Western societies and internationally; (c) the pandemic (including the lock-downs) has caused increased distress; and (d) universities are under increased pressure to produce flexible job-ready graduates for an economically uncertain post-pandemic society. Psychology education can contribute to solutions for these issues. In summary, we have an opportunity now to rethink and to “sell” psychology education as a valuable preparation for work and life in the post-pandemic 21st Century.

It is worth noting that there is a significant challenge inherent in this endeavor: our human tendency to hold tightly to our current world view, and resist taking on new information, including that offered by psychological research, that challenges that world view. For example, we refer to the human tendency to be biased, that has contributed in the last few years to startling increases in the spread of misinformation and its more dangerous counterpart, intentional disinformation, about a range of societal problems with psychological components (e.g., Scheufele and Krause, 2019; Treen et al., 2020; Su, 2021). These include the spread of the pandemic, vaccines and other solutions to the pandemic, climate change, and xenophobia, racism, and other forms of bigotry. The field of psychology is uniquely situated to help combat misinformation and disinformation, particularly by using our understanding of cognitive biases, social influences, behavioral nudges, and attitudinal change. Moreover, psychology education is perfectly situated to harness research from these areas to enhance information, media, and scientific literacy-skills that are currently more often addressed in other fields, such as communication and information science (e.g., Cooke, 2021; Vraga et al., 2021).

Psychology educators are familiar with these challenges (e.g., Halpern and Dunn, in press), and we argue that we should be sharing and further developing our strategies to advance this imperative (Miller, 1969). Given the challenges faced by global society, and the obvious contributions to their management by psychological science, it is time to emphasize the role of psychological literacy (PL) in creating positive health and wellbeing through creating some additional “r’s” to coexist alongside reading, writing and arithmetic, such as the capacities for healthy relationships, critical reflexivity, and resilience—at individual, group and societal levels.

In terms of psychological literacy (PL), Morris et al. (2021, p.2) recently stated that there:

“…appear to be two current approaches to defining and operationalizing PL: (a) as a set of capabilities—knowledge, skills, and attitudes-that a student should acquire during their psychology education, and (b) as a general capacity to intentionally apply psychology to achieve personal, professional, and societal goals. Regarding the former, although there is some consensus regarding what constitutes the set of capabilities, further development is required. Regarding the latter, practical implications, challenges and opportunities require further exploration”.

We consider (a) these challenges and opportunities as an invitation to develop a unifying paradigm of PL, and (b) the current societal climate as providing the impetus to do so.

In summary, the aims of this paper are to (a) propose a general model for the outcomes of undergraduate psychology education, (b) examine the advantages and disadvantages of adopting psychological literacy as a pedagogical philosophy, and (c) suggest ways forward through an international collaborative effort to radically change psychology education and thus, psychology.

In 2016, international consensus was reached on what capabilities “practicing professional psychologists” should possess [International Association of Applied Psychology (IAAP) and International Union of Psychological Science (IUPsyS), 2016]. One of the aims of this paper is to provide a stimulus to achieve international consensus regarding what capabilities graduates of an undergraduate psychology program (psychological scientists) should possess.

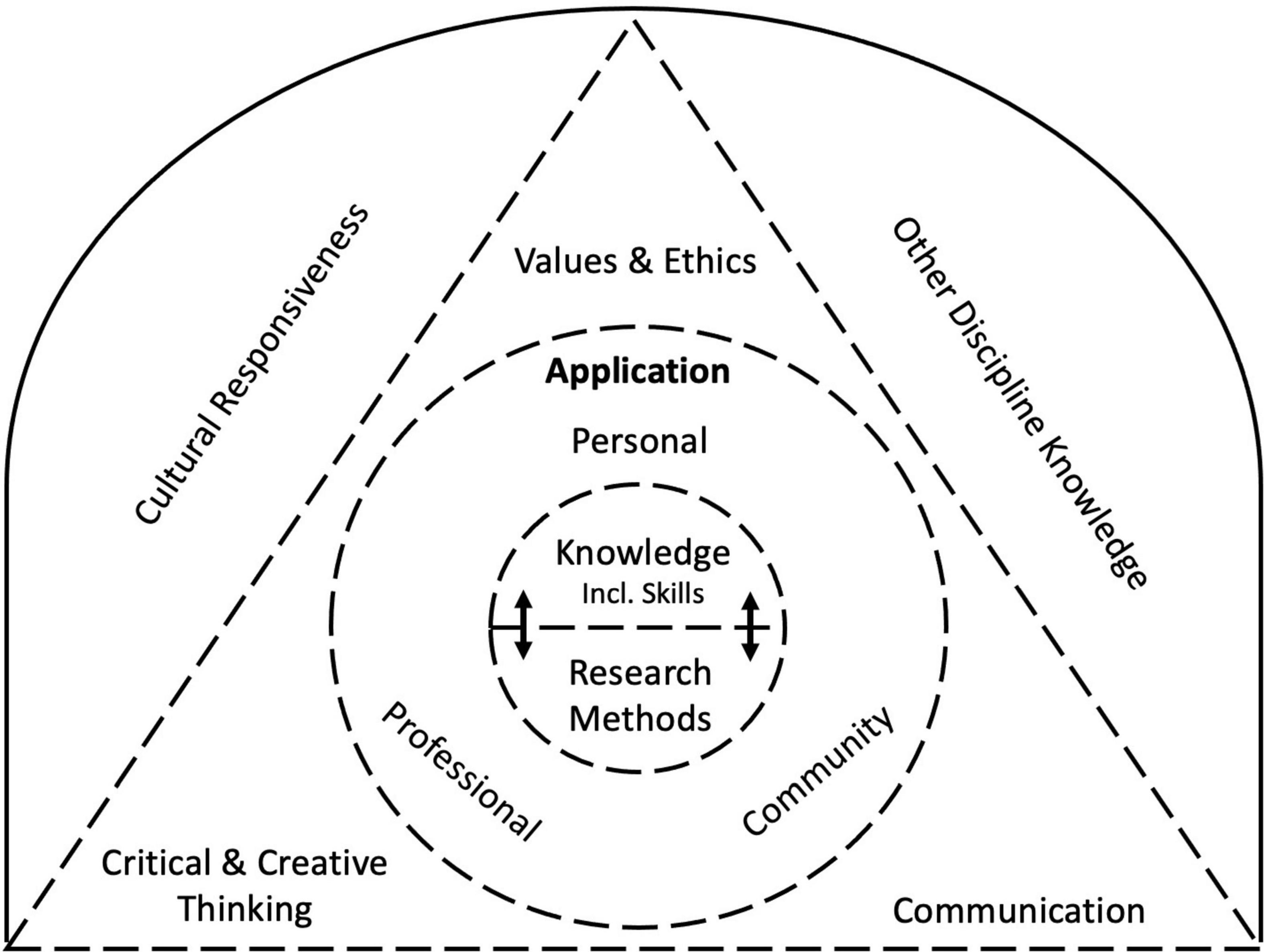

Building on significant previous contributions (e.g., Altman, 1996; Cranney and Morris, 2011), Figure 1 presents a model of undergraduate psychology graduate capabilities and interconnectivities. At the center is discipline-specific Knowledge (including skills—see Krathwohl, 2002), created by discipline-accepted Research Methods. Application of Discipline Knowledge occurs in three broad interconnecting domains/contexts: Personal, Professional, and Community. Application of Knowledge assumes the ability to apply both one’s existing (in one’s head) and “to-be-found” Knowledge, and the latter requires skills in locating and evaluating relevant information.

Figure 1. Undergraduate psychology education graduate capabilities and interconnectivities. The Core of the discipline of psychology, Knowledge, Research Methods and Application (of Knowledge to Personal, Professional and Community Domains, with the latter including Local, National, and International), is represented by the two circles. The Generic capabilities of Values and Ethics, Critical Thinking, and Communication are not only expected graduate capabilities of most undergraduate students, but they influence and are influenced by Core discipline capabilities. Indeed, the dashed lines indicate two-way influence across near and far figurative boundaries (e.g., Values influence Methods that influence Knowledge). This model builds upon and extends Figure 6 of Cranney et al. (2012). Note that Other Discipline Knowledge interacts with the Psychology Core and Generic capabilities. Cultural Responsiveness infuses all other capabilities. Finally, the scale of the figure does not depict the recommended extent of focus in the curriculum (e.g., one would expect a significant focus on research methods).

The capabilities within the circles are the core psychology education capabilities. Within the points of the UG psychology education triangle are the primary broad “generic” capabilities: Values and Ethics, Communication, and Critical Thinking. Psychology Knowledge, as well as knowledge from other disciplines, contributes to these generic capabilities, and of course, these generic capabilities influence Knowledge and Research Methods (e.g., critical thinking as applied in the research process). This triangle of psychology graduate capabilities is situated within the entire context of (a) Other Discipline Knowledge, where psychology Knowledge plays a key “hub discipline” role (Boyack et al., 2005), but there is bidirectional interactivity, and (b) Cultural Responsiveness, which infuses all capabilities. Based on the work of Darlaston-Jones and others (e.g., Darlaston-Jones, 2018; Dudgeon et al., 2018), we describe cultural responsiveness as the capacity to display ongoing critical reflexivity in striving toward respectful relationships with individuals and groups from diverse cultures and backgrounds. The capabilities and their definitions are listed in Table 1, and our extensive, literature-based “unpacking” of these capabilities (including assessment challenges; e.g., Halonen et al., 2020) is presented in the Supplementary Material.

As previously indicated, PL can be conceptualized as a general capability, or as a group of capabilities. Within the undergraduate psychology program, whereby a moderate level of PL is expected to be acquired, PL necessarily consists of a “moderate” level of acquisition of the Table 1 group of capabilities. Exactly what “moderate level” means will need to be determined by an international panel, and be implemented at an institutional program level. In the Supplementary Material, we state how these capabilities relate well to existing capability listings in the United States and the United Kingdom.

Of course, there will be the occasional mismatch across categories of national psychology capability listings, but what is important is that: (a) the capabilities are mostly represented in each listing, and (b) education leaders, in continuously improving their listing, examine other listings to help them determine whether there are important gaps. Just as importantly, there is a need to develop and share strategies for teaching and assessing these capabilities, and for the quality assurance of such. International collaboration should expedite this endeavor.

In terms of a general definition of PL, we offer the following: PL is the intentional values-driven application of psychology Knowledge to achieve personal, professional, and community goals. We purposefully omitted the word “ethical” that Murdoch et al. (2016) used in his similar definition, because the education that psychology major students receive should afford opportunities for students to examine their own values, moral philosophy and ethical frameworks, that will guide their behavior [see Chapter 9, Morris et al. (2018), for how this might be achieved]. Nevertheless, the use of the term “values-driven” acknowledges that our behavior is influenced by values, and we should be aware of such. It is also worth noting that, as Cranney and Morris (2021) argued, the use of skills that have an evidence-base for their effectiveness derived from psychological research, does not in itself constitute PL; PL also requires at least a moderate understanding of the theories and research relevant to each skill [see Miller (1969), for a similar argument]. Further research is required to develop feasible and valid behavioral measures of PL that can be administered not only to psychology students/graduates, but to any group in society (Newell et al., 2020; Morris et al., 2021; Machin and Gasson, 2022).

A critical ingredient of PL as the outcome of psychology education is the teaching approach of psychology educators, which is the subject of the next section.

A pedagogical or teaching philosophy can be thought of as the values, assumptions and knowledge that a teacher brings to designing, delivering, evaluating and improving their teaching practice. What does PL as a pedagogical philosophy entail? Firstly, acquisition of a moderate level of PL is accepted as the desired minimum outcome of psychology education (Cranney and Morris, 2021). Within an undergraduate education context, PL would most expediently be operationalized in terms of the group of capabilities outlined above; even if the educator holds as a guiding principle the notion of PL in its general conceptualization. Indeed, educators within any unit (or preferably, the whole program) may have more aspirational notions about what outcomes could and should be achieved, such as psychologically literate global citizenship (Bringle et al., 2016). Psychological literacy provides a unifying framework that inoculates against the pressures that would undermine the potential positive impact of psychology education (i.e., pedagogic frailty; Winstone and Hulme, 2017). Secondly, educators take a scientist-educator (or scholar-educator) approach, which involves adopting evidence-based teaching (EBT) strategies, and then reflecting on the effectiveness of those strategies in their particular context, recording the outcome (and preferably engaging in scholarship of teaching and learning), and subsequently modifying their practice (e.g., Bernstein et al., 2010; Worrell et al., 2010; Dunn et al., 2013), thus creating “practitioner evidence-based practice” (Green, 2008). Thirdly (and this factor may seem quite daunting but is “high impact” for student learning), educators themselves model psychological literacy in the classroom (McGovern, 2012; Hulme, 2014; Hulme and Cranney, in press).

We now consider how psychology education leaders can begin to make the paradigm shift to curriculum and pedagogical renewal that will enable our bachelor-level graduates to utilize their capabilities to achieve better outcomes for themselves, as well as for their communities.

Psychology education is a near-global phenomenon, and so an international response is needed to seek consensus regarding the broad scope of undergraduate psychology graduate capabilities, and PL as a pedagogical philosophy. Once consensus is reached, there is an urgent need to create and share resources for teaching and assessment of those capabilities. The urgency is driven by two factors: (a) many nations have poorly resourced education systems, and this has been exacerbated by the pandemic impact on national economic systems, with universities often given low priority, and (b) as argued in the introductory section, there is an urgent need now to produce psychology graduates capable of contributing to local, national and global communities. The creation of resources may in some cases require creative technological innovation, for example, to economically develop and assess Communication capability. Imagine the potential of thorough training in “active listening”—with advances in AI, a thorough grounding in (and assessment of) the basics in active listening could be achieved through an interactive program using an avatar respondent/evaluator. This skill will be useful not only in professional contexts (e.g., professional psychology, management—actually, any legitimate profession), but also personal contexts (e.g., between romantic partners, between parents and children). We should also look to other disciplines/professions that have made progress in such domains (e.g., Liu et al., 2016).

Also, students as partners should be a central part of the answer. Imagine senior undergraduate students creating training programs for junior students (e.g., in counseling micro-skills), and some of these programs being of such high quality that they can be shared on an international platform. Students as partners could also contribute to evidence-based teaching practice, for example, through the sharing of psychological evidence for inclusive practices created by research conducted by disabled or other minoritized students (e.g., Hamilton et al., 2021). That is, from these student partnerships, educators would learn creative, inclusive and economical ways to support the development of psychology capabilities.

In addition, educator and student engagement with leaders in professional and community contexts through work-integrated and service-learning experiences would serve to expose those leaders to the value of psychology, with multiple benefits for students, graduates, educators, and the discipline and “profession” of psychology. Imagine such a partnership contributing to the development of a platform for work-integrated or service learning that could be deployed internationally, such that any Department of Psychology could seamlessly organize a face-to-face, blended or online Application to Professional/Community Domain learning experience for their undergraduate students.

Finally, we offer the following recommendations for consideration by local, national and international psychology education leaders, to move us toward this vision.

At the international level, a group of psychology education leaders from several nations is formed to first determine a process for consensus-seeking regarding international psychology undergraduate capabilities. These initial steps will be quite challenging, given different languages, cultures (including psychology education cultures), and resource disparities. Lessons in inclusive cooperation can be learned from previous international projects [e.g., Lunt et al., 2011; International Association of Applied Psychology (IAAP) and International Union of Psychological Science (IUPsyS), 2016]. Indeed, this process of consensus-seeking could be initiated through direct submissions to international psychology organizations and collaborative bodies. If consensus is reached, then different groups would be delegated to locate and create accessible resources to support the development and assessment of those capabilities. Funding may need to be sought for technological development, but there is also the potential for creative and economical input from Students as Partners.

At the national level, psychology education organizations could contribute to the international efforts, but also take the opportunity to interrogate and reimagine their national psychology curriculum and standards in the contexts of both the international effort and national societal needs. Quality assurance standards and processes should be revised to better align with any international consensus regarding psychology capabilities. In terms of national societal needs, psychology organizations could look to specific professional development needs for the nation. For example, if there is an urgent need for highly trained disability workers, then there could be a national effort to create units on the psychology of disability work, which undergraduate psychology students from any program could take as electives. Most nations would have significant social justice issues in need of urgent redress; for example, in Australia, where there are unacceptable disparities in quality of-life-indices for First Peoples, a national community of practice has been created to support practice sharing in Indigenizing the psychology curriculum, supporting Indigenous psychology students, and supporting the development of cultural responsiveness in all psychology students (e.g., Dudgeon et al., 2016). On a different note, national psychology peak discipline/professional bodies could: (a) significantly improve their support and advocacy for psychology education and psychology educators, including promoting the value of undergraduate psychology education to both governments and employers, and (b) promote the value of all aspects of psychology more generally across society, for example, by contributing to national strategies to deal with ongoing societal issues such as the COVID-19 pandemic, war and conflict, refugee crises, climate change, racism, and misogyny. Psychology students and educators would be inspired by such genuine community-minded leadership. The first step at the national level, following international consensus regarding graduate capabilities, is to bring together all relevant national stakeholder organizations (including student, employer and national community representatives), and determine actions to collaboratively progress quality undergraduate psychology education outcomes.

At the local level, Departments of Psychology would contribute to the national and international efforts, but also take the opportunity to reimagine their local psychology curriculum in the contexts of both the international/national effort and local community needs. Most importantly, during a regular program review, the Department’s curriculum could be revised to better align with any international consensus and subsequent national standards revisions regarding psychology capabilities. In terms of local community needs, Departments could form partnerships with local employer and community organizations to determine local needs (e.g., Hamilton et al., 2008; Landrum, 2018; Hulme and Cranney, in press), which could result in ongoing work-integrated and service learning partnerships, as well as the development of specialist units to provide “work-ready” specialist training. In addition, the Department’s leadership team could devise strategies to better support their teaching staff in contexts where (a) research productivity is still prioritized over educational productivity in terms of institutional promotion processes, despite student fees being the primary income for the institution, and (b) undergraduate psychology education is yet to be fully understood and valued by higher education institutions, governments, and society more broadly. First steps in this process would include (a) the provision of training to support educators to develop their own PL, and (b) all local stakeholder organizations (including student, employer and local community representatives) to meet to determine actions to collaboratively progress quality undergraduate psychology education outcomes.

Imagine a future where our undergraduate students graduate with a high level of confidence that they will be able to achieve their personal, professional, and community goals. Imagine a future where such graduates are “snapped up” by business and community organizations alike, because such organizations highly value the capabilities that these graduates possess. Imagine a future where the general public and governments understand and highly value the discipline and “profession” of psychology, because of the contributions of these psychology graduates. These are outcomes worth striving for.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

JC contributed most to the conceptual development and writing. DD, JH, SN, SM, and KN contributed approximately equally to the conceptual development and writing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We would like to gratefully acknowledge that the publication cost of this article was covered by Kimberley Norris’s Consultancy Account (School of Psychological Sciences, University of Tasmania). We would like to thank Professor Judith Gullifer and Associate Professor Dawn Darlason-Jones for providing some key information as well as Rebecca Tyler for assistance with Figures and References.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2022.790600/full#supplementary-material

Altman, I. (1996). Higher education and psychology in the millennium. Am. Psychol. 51, 371–378. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.51.4.371

Bernstein, D., Addison, W., Altman, C., Hollister, D., Komarraju, M., Prieto, L., et al. (2010). “Toward a scientist-educator model of teaching psychology,” in Undergraduate Education in Psychology: A Blueprint for the Future of the Discipline, ed. D. F. Halpern (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 29–45. doi: 10.1037/12063-002

Boyack, K. W., Klavans, R., and Börner, K. (2005). Mapping the backbone of science. Scientometrics 64, 351–374. doi: 10.1007/s11192-005-0255-6

Bringle, R. G., Reeb, R. N., Brown, M. A., and Ruiz, A. I. (2016). Service Learning in Psychology: Enhancing Undergraduate Education for the Public Good. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Cooke, N. A. (2021). “Media and information literacies as a pesponse to misinformation and populism,” in The Routledge Companion to Media Disinformation and Populism, (Milton Park: Routledge), 489–497. doi: 10.4324/9781003004431-51

Cranney, J., Botwood, L., and Morris, S. (2012). National Standards for Psychological Literacy and Global Citizenship: Outcomes of Undergraduate Psychology Education, 2012 Final Report. ALTC/OLT National Teaching Fellowship. Available online at: http://altf.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Cranney_J_NTF_Final-Report_2012.pdf (accessed October 5, 2021).

Cranney, J., and Morris, S. (2011). “Adaptive cognition and psychological literacy,” in The Psychologically Literate Citizen: Foundations and Global Perspectives, eds J. Cranney and D. S. Dunn (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 251–268. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199794942.003.0063

Cranney, J., and Morris, S. (2021). “Psychological literacy in undergraduate psychology education and beyond,” in Handbook on the State of the Art in Applied Psychology, eds P. Graf and D. Dozois (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell), 315–337.

Darlaston-Jones, D. (2018). Cultural Responsiveness. Available online at: http://www.psychliteracy.com/concepts (accessed March 14, 2022).

Dudgeon, P., Darlaston-Jones, D., and Bray, A. (2018). “Teaching Indigenous psychology: A conscientisation, de-colonisation and psychological literacy approach to curriculum,” in Teaching Critical Psychology: International Perspectives, eds C. Newnes and L. Golding (Milton Park: Routledge), 123–147.

Dudgeon, P., Darlaston-Jones, D., Phillips, G., Newnham, K., Brideson, T., Cranney, J., et al. (2016). Australian Indigenous Psychology Education Project Curriculum Framework. University of Western Australia. Available online at: https://indigenouspsyched.org.au/frameworks/#core-frameworks (accessed October 5, 2021).

Dunn, D. S., Saville, B. K., Baker, S. C., and Marek, P. (2013). Evidence-based teaching: Tools and techniques that promote learning in the psychology classroom. Aust. J. Psychol. 65, 5–13. doi: 10.1111/ajpy.12004

Green, L. W. (2008). Making research relevant: If it is an evidence-based practice, where’s the practice-based evidence? Fam. Pract. 25, i20–i24. doi: 10.1093/famprac/cmn055

Halonen, J. S., Nolan, S. A., Frantz, S., Hoss, R. A., McCarthy, M. A., Pusateri, T., et al. (2020). The challenge of assessing character: measuring APA goal 3 student learning outcomes. Teach. Psychol. 47, 285–295. doi: 10.1177/0098628320945119

Halpern, D. F., Anton, B., Beins, B. C., Bernstein, D. J., Blair-Broeker, C. T., Brewer, C., et al. (2010). “Principles for quality undergraduate education in psychology,” in Undergraduate Education in Psychology: A Blueprint for the Future of the Discipline, ed. D. Halpern (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 161–163. doi: 10.1037/a0025181

Halpern, D. F., and Dunn, D. S. (in press). Thought and Knowledge: An Introduction to Critical Thinking, 6th Edn. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Halpern, D. F., and Dunn, D. S. (2021). Critical thinking: A model of intelligence for solving real-world problems. J. Intell. 9:7. doi: 10.3390/jintelligence9020022

Hamilton, K., Charlton, S., and Elmes, R. (2008). Developing a four-year baccalaureate degree in applied psychology. Plann. High. Educ. 36, 23–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2007.00675.x

Hamilton, P., Hulme, J. A., and Harrison, E. D. (2021). Experiences of higher education students with chronic illnesses. Disabil. Soc. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2021.1907549

Hulme, J., and Cranney, J. (in press).“Psychological literacy and learning for life,” in International Handbook of Psychology Learning and Teaching, eds J. Zumbach, D. Bernstein, S. Narciss, and P. Marsico (Berlin: Springer).

International Association of Applied Psychology (IAAP) and International Union of Psychological Science [IUPsyS]. (2016). International declaration of core competencies in professional psychology. Available online at: http://www.iupsys.net/dotAsset/1fd6486e-b3d5-4185-97d0-71f512c42c8f.pdf [accessed October 6, 2021].

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of bloom’s taxonomy: an overview. Theory Pract. 41, 212–218. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip4104_2

Landrum, E. (2018). The Care and Feeding of Psychology Majors: Learning Outcomes, Marketable Skills, and the Career Launch. Tallahassee, FL: National Institute for Teaching of Psychology.

Liu, C., Lim, R. L., McCabe, K. L., Taylor, S., and Calvo, R. A. (2016). A web-based telehealth training platform incorporating automated nonverbal behavior feedback for teaching communication skills to medical students: a randomized crossover study. J. Med. Internet Res. 18:e246. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6299

Lunt, I., Job, R., Lecuyer, R., Peiro, J. M., and Gorbena, S. (2011). Tuning Educational Structures in Europe: Reference Points for the Design and Delivery of Degree Programmes in Psychology. University of Deusto. Available online at: http://tuningacademy.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/RefPsychology_EU_EN.pdf (accessed October 6, 2021).

Machin, M. A., and Gasson, N. (2022). “An introduction to careers in the psychological sciences,” in The Australian Handbook for Careers in Psychological Science, eds M. A. Machin, T. M. Machin, P. N. Hoare, and C. Jeffries (Toowoomba: University of Southern Queensland).

McGovern, T. V. (2012). “Faculty virtues and character strengths: Reflective exercises for sustained renewal,” in Society for the Teaching of Psychology, ed. J. R. Stowell (Washington, DC: Society for the Teaching of Psychology).

Miller, G. A. (1969). Psychology as a means of promoting human welfare. Am. Psychol. 24, 1063–1075. doi: 10.1037/h0028988

Morris, S., Cranney, J., Baldwin, P., Mellish, L., and Krochmalik, A. (2018). The Rubber Brain: A Toolkit for Optimising Your Study, Work, and Life. Bowen Hills: Australian Academic Press.

Morris, S., Norris, K., and Cranney, J. (2021). “Psychological Literacy,” in Oxford Bibliographies in Psychology, ed. D. S. Dunn (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Murdoch, D. D. (2016). Psychological literacy: Proceed with caution, construction ahead. Psychol Research and Behav. Manag. 9, 189–199. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S88646

Newell, S. J., Chur-Hansen, A., and Strelan, P. (2020). A systematic narrative review of psychological literacy measurement. Aust. J. Psychol. 72, 123–132. doi: 10.1111/ajpy.12278

Scheufele, D. A., and Krause, N. M. (2019). Science audiences, misinformation, and fake news. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 7662–7669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1805871115

Su, Y. (2021). It doesn’t take a village to fall for misinformation: Social media use, discussion heterogeneity preference, worry of the virus, faith in scientists, and COVID-19-related misinformation beliefs. Telemat. Inform. 58:101547. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2020.101547

Treen, K. M. D. L., Williams, H. T., and O’Neill, S. J. (2020). Online misinformation about climate change. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change. 11:e665. doi: 10.1002/wcc.665

Vraga, E. K., Tully, M., Maksl, A., Craft, S., and Ashley, S. (2021). Theorizing news literacy behaviors. Commun. Theory 31, 1–21. doi: 10.1093/ct/qtaa05

Winstone, N. E., and Hulme, J. A. (2017). “Integrative disciplinary concepts: The case of psychological literacy,” in Pedagogic Frailty and Resilience in the University, eds I. M. Kinchin and N. E. Winstone (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers), 93–107. doi: 10.1007/978-94-6300-983-6_7

Worrell, F. C., Cassad, B. J., McDaniel, M., Messer, W. S., Miller, H. L., Prohaska, V., et al. (2010). “Promising principles for translating psychological science into teaching and learning,” in Undergraduate Education in Psychology: A Blueprint for the Future of the Discipline, ed. D. F. Halpern (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 129–144. doi: 10.1037/12063-008

Keywords: international undergraduate psychology education, psychological literacy, graduate capabilities, self-management, employability, international, global citizenship, COVID-19

Citation: Cranney J, Dunn DS, Hulme JA, Nolan SA, Morris S and Norris K (2022) Psychological Literacy and Undergraduate Psychology Education: An International Provocation. Front. Educ. 7:790600. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.790600

Received: 07 October 2021; Accepted: 23 March 2022;

Published: 18 May 2022.

Edited by:

Mohamed A. Ali, Grand Canyon University, United StatesReviewed by:

Jinjin Lu, Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Cranney, Dunn, Hulme, Nolan, Morris and Norris. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jacquelyn Cranney, Si5DcmFubmV5QHVuc3cuZWR1LmF1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.