- 1University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria

- 2Coal City University Emene, Enugu, Nigeria

- 3Alex Ekwueme Federal University Ndufu Alike, Abakaliki, Nigeria

- 4Enugu State University of Science and Technology, Enugu, Nigeria

- 5Federal Polytechnic, Oko, Nigeria

Lecturing in private universities in Nigeria is one of the most challenging jobs for early career scholars. Regrettably, there is a high rate of turnover once an opportunity for exit presents itself. Researchers have proposed a relationship between psychological contract breach and turnover intentions. This study attempted to evaluate the effect of organizational climate in the link between psychological contract breach and turnover intentions using a sample of 584 private university lecturers in a two-wave investigation (time-lagged design) during a 1-month period (with 2 weeks interval). The ages ranged between 24–53 years old (38.24 ± 7.33). The questionnaires used to collect data were the Psychological Contract Breach Scale, Organizational Climate Description Questionnaire and Turnover Intention Scale. The result suggested that lecturers who received support from management were less likely to leave their jobs, while experiencing peace in the school played a significant factor in reducing turnover intention. The study’s implications were raised, and further suggestions were made to improve our organizations, particularly, universities.

Introduction

Ahmad and Riaz (2011) noted that turnover intentions had attracted much attention among researchers due to its widespread effect on many organizations over the years. Turnover intention is considered the careful thought an individual holds about changing his job after some time (Sousa-Poza and Henneberger, 2002). This behavior is costly for the new generation organizations (Aquino et al., 2004). Research has shown that in Pakistan, Singapore, and South Korea, lecturers’ turnover intention and actual turnover have risen above 60% (Ali, 2008). As sampled in Pakistan by Haq et al. (2011), teachers’ turnover intentions produced a stunning 53% record. Afolabi (2005) reported that turnover among lecturers in private universities in Nigeria was over 46%. Earlier studies have shown that turnover intentions attract negative behaviors such as abuse of privileges and sabotage (Ambrose et al., 2002; Harris and Ogbonna, 2002). Others found turnover intentions associated with abusing substances, breaking the organization’s rules, and thefts (Thomas et al., 2001; Sims, 2002). These unhealthy work behaviors have crumbled many organizations globally (Ahmad and Riaz, 2011).

Attention has shifted to the negative behaviors that impinge the university system (Harris and Ogbonna, 2002; Windon et al., 2019; Alo and Dada, 2020). In line with the increasingly pervasive nature of the adverse outcomes of turnover intentions (Robinson and Greenberg, 1998; Harder et al., 2015; Windon et al., 2019; Alo and Dada, 2020), universities are beginning to focus on the possible precursors. Researchers have placed psychological contract breach as the forerunner of turnover intentions (Robinson and Morrison, 1995; Douglas and Martinko, 2001; Vardi, 2001; Greenberg et al., 2003), suggesting a negative link between psychological contract breach and job dedication, satisfaction, and goal to decrease turnover. Morrison and Robinson (1997) defined psychological contract breach as employees’ mental assessment of what they will receive versus what they anticipate. A psychological contract breach also refers to an individual’s understanding that the organization has failed to fulfill the seeming promises or obligations in their employment relationships (Coyle–Shapiro and Kessler, 2000).

The exploration of psychological contract breach as a potential antecedent of the turnover intentions serves as a basis for identifying new approaches to understanding and addressing turnover intentions rate among employees pursuing a career in the academia. It also further affirms the solid linear relationship that exists between psychological contract breach and turnover intentions.

Furthermore, the breach of psychological contracts has a detrimental impact on employees’ attitudes and actions (Robinson and Morrison, 1995; Robinson, 1996). Robinson and Rousseau (1994) assert that when employees feel the management has not fulfilled its part of the business contract, they feel betrayed and increase their turnover intentions. Notably, the influence of this breach of psychological contract within the university system is unaddressed extensively. The current study additionally investigates the dynamics of the connection between psychological contract breach and intention to leave by examining the moderating influences of organizational climate. We chose organizational climate because Carr et al. (2003) established that organizational climate influences work outcomes such as job performance, employee disengagement, and psychological wellbeing by interacting with organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Thus, organizational climate implies those attributes that define a work environment.

Psychological Contract Breach and Turnover Intentions

According to Freese (2007), a psychological contract relates to an employee’s belief about his labor contribution and the expected reward from management. Emphatically, a psychological contract explained in few words implies the terms of an agreement between the employee and the administration as it exists in the employee’s mindset. It goes beyond the written contract terms but instead, deals with the belief of the employee. According to Herriot et al. (1997), they conceived psychological contracts in two ways. Firstly, from the standpoint, two parties are involved where both have their obligations to perform as it concerns an employment agreement. These obligations should be clear and easily understood through formal documentation of an agreement term between the employee and the organization or suggested without being directly expressed. Secondly, a psychological contract comes from the employee’s mental set (Herriot et al., 1997). This approach addresses the feelings and opinions of the employee concerning the exchange terms as the organization models it. In psychological contract, Rousseau (1995) noted that employees willingly accept the official agreement concerning their obligations and management. According to Rousseau (1990), the psychological contract is described primarily on an individual’s thoughts or beliefs rather than facts and may sometimes be unjust.

For example, employees expect (that) higher pay, promotion, and a good working environment will reciprocate hard work and obedience (Rousseau, 1990). As we study the academia, we align with the second conceptualization of psychological contract, which relies on the belief an employee holds about his duties and his expectations from the management in return. These expectations trigger the employee’s perception of management defiance from promise (Robinson and Rousseau, 1994; Zhao, Wayne, et al., 2007). Studies on psychological contract breaches found that organizational obligations and violated promises negatively influence employees’ attitudes and actions (Robinson and Rousseau, 1994; Kiewitz et al., 2009). In addition, employees who see a breach of the psychological contract begin to wonder if they should stay in the organization or whether the continuation of work relations would benefit them or not (Turnley and Feldman, 2000; Aykan, 2014). As a result, in this investigation, this hypothesis was developed:

H1: Psychological contract breach will positively predict turnover intentions among lecturers in Nigerian private universities.

Organizational Climate and Psychological Contract Breach

Organizational climate is the typical features or qualities that define an organization’s work environment, differentiating it from another. To a large degree, these qualities could last long and alter employees’ behavior in the organization (Liou and Cheng, 2010). More so, to a large extent, organizational climate includes behaviors that encourage healthy interaction among university staff members. It enables academic and non-academic workers to collaborate in academic-related tasks, facilitating corporate goals and objectives. Domitrovicha et al. (2019) used the term school climate to explain organizational climate. They defined it as the perception the staff hold concerning their safety, associations, relationships, academic practices, and the teaching environment, including their mode of operations and functioning. Cohen et al. (2009) noted that this organizational climate develops due to the constant social, academic, and administrative practices among staff and management of such institutions. This interaction builds the trust, loyalty, and managerial leadership style that define the organizational climate. Literature has suggested that organizational climate and psychological contract breach do not relate positively (Ahmed and Muchiri, 2014; Terera, 2019). According to reports, individuals who feel a breach of psychological contract are often from a hostile work environment. A sign of an unfulfilled contract is an indication of a poor work environment.

Organizational Climate and Turnover Intentions

Puspitawati and Atmaja (2019) suggest that organizational climate is negatively associated with turnover intention. An employee’s purpose defines and moderates his level of work performance because it influences his choice of action (Mishra and Bhatnagar, 2010). The features or qualities of this organizational climate are peculiar and unique to every university. Thus, it serves as the yardstick for measuring an employee’s feelings and beliefs about his university. Within the university environment, organizational climate affects employees’ efficiency, output, and commitment as it defines their contribution to students’ learning and community development. Research has shown that the growth and success of these universities could depend heavily on the organizational climate that exists within them. Hartini et al. (2020) reported that organizational climate and turnover intentions share a negative relationship. With the introduction of a favorable organizational climate such as reward, responsibility, and good standards, the management could minimize the rate of turnover intentions (Carmeli and Vinarski-peretz, 2010; Subramanian and Shin, 2013). Most studies have argued that turnover intentions are disruptive and unhealthy for organizational growth and development, negatively impacting work outcomes (Chau et al., 2009; Jeswani and Dave, 2012; Mei Teh, 2014).

Psychological Contract Breach and Turnover Intentions: Moderations by Organizational Climate Dimensions

Schneider et al. (2000) posited that organizational climate is the air workers breathe, feel, and sense their corporate practices, ideas, plans, and strategies. Employees monitor their work environments concerning their activities and decipher what is more important to their organization. There are five components to organizational climate: supportive behavior, directive behavior, dynamic behavior, frustrating behavior, and intimate behavior. The efforts of university officials to stimulate, assist, and promote lecturers’ welfare and task achievements in the university imply supportive conduct. It is managerial conduct that encourages workers to feel pleasant, calm, and a sense of belonging to the university. “Directive conduct” refers to a university’s strict, regulated, and authoritative monitoring of lecturers and university activities. Lecturers’ engaged behavior refers to their proud, dedicated, and supportive attitude toward their colleagues, students, and the university. Frustrated conduct characterizes a lecturer’s sense of burden and interference from colleagues and administrative tasks unrelated to instructing. These are the habits that keep instructors stressed and dissatisfied with the university system. Finally, the term “intimate behavior” refers to a lecturer’s strong and coherent social relationships with other colleagues. These are behaviors that promote pleasantries, friendliness, and support among colleagues.

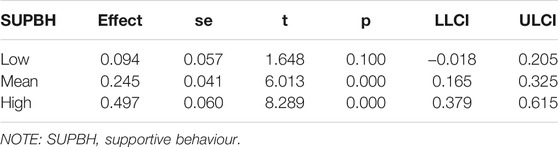

Several studies have found a favorable relationship between organizational climate and workplace outcomes such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, job performance, job participation, and organizational citizenship behavior (Adeyemi, 2008; Agyemang, 2013; Berberoglu, 2018; Bhat, 2013; Bhat and Bashir, 2016; Gheisari et al., 2014; Nwankwo et al., 2015; Okoli, 2019; Raja et al., 2019; Tsai, 2014; Turan, 1998; Valdez and Villa, 2019), and negatively linked to a psychological contract breach, counterproductive work behavior, and turnover intentions (Kanten, and Ülker, 2013; Chernyak-Hai, and Tziner, 2014; Kasekende et al., 2015; Conley and You, 2018; Sheu et al., 2019). According to Bamberger et al. (2008), an adverse organizational atmosphere might contribute to turnover intentions and other bad behavior. Given the nature of the negative consequences of a hostile corporate environment at universities, we anticipate that organizational climate (dimensions) will mitigate the association between psychological contract violation and desire to leave (see Figure 1). As reviewed literature has shown the high rate of turnover intentions in organizations like the university, we presume that the climate perceived by the academia could determine the extent they commit to the university. Thus, we hypothesized the following:

FIGURE 1. Proposed model for the study. Hypothesized model of the moderating roles of organizational climate dimensions on the associations between psychological contract breach and turnover intentions.

H2a: Organizational climate (supportive) will negatively predict turnover intentions among lecturers in Nigerian private universities.

H2b: Organizational climate (directive) will negatively predict turnover intentions among lecturers in Nigerian private universities.

H2c: Organizational climate (engaged) will negatively predict turnover intentions among lecturers in Nigerian private universities.

H2d: Organizational climate (frustrated) will negatively predict turnover intentions among lecturers in Nigerian private universities.

H2e: Organizational climate (intimate) will negatively predict turnover intentions among lecturers in Nigerian private universities.

H3a: Organizational climate (supportive) will negatively moderate the relationship between psychological contract and turnover intentions.

H3b: Organizational climate (directive) will negatively moderate the relationship between psychological contract and turnover intentions.

H3c: Organizational climate (engaged) will negatively moderate the relationship between psychological contract and turnover intentions.

H3d: Organizational climate (frustrated) will negatively moderate the relationship between psychological contract and turnover intentions.

H3e: Organizational climate (intimate) will negatively moderate the relationship between psychological contract and turnover intentions.

The study anchors on the social exchange theory because psychological contracts rely on giving and taking. Bal et al. (2013), Kasekende et al. (2015) used the social exchange paradigm to demonstrate that high-social exchange acts as a buffer on the negative link between psychological contract breach and performance.

Interestingly, some authors (Idogho, 2006; Adenike, 2011; Adeniji et al., 2018) attributed a lot of adverse behavioral outcomes among academia to unfavorable work climates. The resultant effect is that these unhealthy work behaviors have crippled the academic and social activities that should flourish in these universities. Furthermore, this unhealthy climate has led to insufficient enthusiasm, diminished work motivation, frustration, and tension among academic staff (Adeniji, 2011; Adeniji et al., 2018). To bolster this assertion, Adenike, (2011) and Afolabi (2005) suggested that researchers should study the organizational climate of Nigerian private universities further to trace the precursors of turnover intentions among lecturers.

The 2020 lockdown of academic activities in Nigeria made most private universities adopt virtual working platforms (e.g., Microsoft Team, Zomm, WebEx etc.). Virtual learning which has been used in the developed world even before the pandemic transitioned seamlessly compared to less developed countries like Nigeria (Kyari et al., 2018). This form of learning is considered to be better than the usual in-person interaction because it has the advantage of reaching many learners at the same time and does not require them to come together in a place (Ajadi et al., 2008). This shift consequently has affected the lecturers as some of these new technologies has a steep learning curve affecting some of them in adjusting (Zalat et al., 2021). The learning, and social interaction with peers and other forms of socialization among colleagues have been transferred online which resulted in a significant difference in the reactions to the lockdowns between academic staff and students.

In summary, the present study examines the relationship between psychological contract breach and turnover intentions. Also, the moderating effects of organizational climate dimensions on the association between psychological contract breaches and turnover intentions. Using social exchange theory to establish an integrative framework of psychological contract breach, turnover intentions, and organizational climate. As much as the private universities’ salaries are less than the government owned institutions, some staff remain even with opportunities for a higher paying job. This discrepancy cannot be captured in the social exchange theory. The gap here highlights the organizational cultural differences that explained the pattern of turnover intentions. This study also highlighted how organizational climate attenuates the effect of unfulfilled promises in the lecturers’ intention to leave.

Methods

Participants

This study enlisted the participation of 584 lecturers from seven private institutions in Southeast, Nigeria. Renaissance University (76), Tansian University (82), Gregory University (68), Godfrey Okoye University (84), Paul University (89), Madonna University (119), and Evangel University (66) are among these institutions. We choose these lecturers at random from these seven private institutions. Among these lecturers, 444 were men (76%) while 140 were females (24%), 419 were married (71.7%) while 165 were single (28.3%); 81were senior lecturers (13.87%), 59 were lecturer I (10.10%), 185 were lecturer II (31.68%), 188 were assistant lecturers (32.19 percent) and 71 were graduate assistants (12.16%). Participants varied in age from 24 to 53 years (M = 38.24, SD = 7.33).

Measures

The Psychological Contract Breach Scale

The researchers used the psychological Contract Breach Scale established by Robinson and Morrison (1995) to assess the breach of the perceived contract of lecturers at their private institutions. They respond to a five-point Likert scale, ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. The 5-item measure yielded a reliability value of α = 0.92 to Robinson and Morrison (2000). Examples include: “I believe my employer has fulfilled the promises made to me” and “My employer has broken many of its promises to me, despite the fact that I have kept my end of the bargain.” In addition, three items were reverse-scored, and two direct scored. According to Robinson and Morrison (2000), high ratings imply a lack of contract fulfillment and vice versa. In this study, we achieved a reliability index for the scale of α = 0.87. A high score on this metric suggests that the contract is not holding and unfulfilled.

Organizational Climate Description Questionnaires

The Kottkamp et al. (1987) OCDQ-RS is a 34 item measure developed to assess the organizational climate of teachers and principals in secondary schools. This measure evaluates five different behavioral attributes of teachers and principals in the school. The response options range from 1 (rarely occurs) to 4 (frequently occurs). These items tap the frequency of occurrence of such behaviors. The research instruments’ reliability consistency was high for the dimensions with principal supportive behavior (α = 0.91) 7items, directive behavior (α = 0.87) 7 items, engaged teacher behavior (α = 0.85) 10 items, frustrated teacher behavior (α = 0.85) 6 items, and intimate teacher behavior (α = 0.71) 4 items.

The OCDQ-RS was modified to suit the university community using field testing, validity, and reliability studies. We used the content and construct validation process to confirm the validity of the instrument. We subjected the OCDQ-RS to a reliability test. We obtained further validation using the responses received from 114 lecturers drawn from Caritas University. Caritas University is one of the private universities in the region and share most characteristics with other private universities in the region. In adopting the scale, we modified some words and items to suit the university community. We changed the terms “principal” to “university authority,” “school” changed to “university,” the word “teachers” was changed to “lecturers,” “teaching” changed to “lecturing.” Also, item number twenty-five (25), “the principal is available after school to help teachers when assistance is needed,” was changed to “the university authority is available to help lecturers when assistance is needed.” The modifications were necessary to capture the terminologies of a university setting. The inter-item correlation of the 34 items ranged from −0.08 to.55 during item analysis, with an internal consistency reliability estimate of Cronbach alpha =0.70. The item analysis also revealed coefficient alpha values of 0.72, 0.67, 0.66, 0.68, and 71 for OCDQ-RS supportive behavior, directed behavior, engaged behavior, frustrated behavior, and intimate behavior.

Turnover Intentions Scale

We used the 5-item Turnover Intentions Scale to measure the lecturer’s turnover intentions (Bluedorn, 1982). They were asked to assess their level of agreement on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 indicating significant disagreement and 5 indicating strong agreement. “I am actively pursuing an alternate employment” and “I will hunt for a new job outside of this organization within the next year” are two examples. Bluedorn (1982) earned α =0.90 dependability index. The researchers obtained an alpha of 0.82 in this study. A high score on the turnover intention measure shows that the company has a substantial turnover intentions.

Procedure

This study adopted a time-lagged design (2-weeks interval) for a period of 1 month using a multi-sectional questionnaire containing both the demographics and the scales. We employed some academic staff in these universities who helped the administration process by distributing this questionnaire to the lecturers in these private universities. The researchers distributed copies of this questionnaire in two batches (2 weeks interval). These research assistants came to serve as informants in this study and supply independent and dependent variable assessments. We distributed the copies of the questionnaire containing the independent factors first, followed by the documents containing the dependent variables. Notably, copies of this questionnaire were tagged with numbers for easy pairing with the sampled lecturers across the two batches. Only those lecturers that consented to the study participated. Those that participated were encouraged to complete the questionnaire within 2 days. However, the research assistants collected the distributed copies within 2 weeks across the two batches. We discarded few copies due to improper completion and the remaining analyzed. The anonymity of the participants was assured by adopting a researcher-to-participant communication during the follow-up phase and all data that could be linked to the participants were destroyed after data entry.

Statistical Analyses

This research ascertained the inter-relationships among the study variables through Pearson r correlation, hypotheses tested using Hayes, (2013, Hayes, 2014) regression-based PROCESS macro. IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences was used to analyze (SPSS v 25). The variables were analyzed across six models considering psychological contract breach, turnover intentions, and organizational climate (supportive, directive, engaged, intimate), as independent, dependent, and moderating variables.

Results

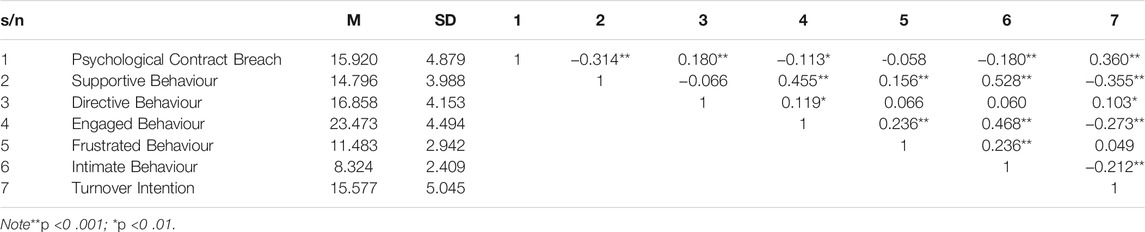

Table 1 above shows the descriptive statistics and correlation matrix of variables. The correlations in Table 1 showed that psychological contract breach was positively correlated with turnover intentions (r = 0.36, p = 0.001). Supportive behavior was negatively related to turnover intentions (r = −0.36, p =0.001). Directive behavior was positively related to turnover intentions (r = 0.10, p =0.013). Engaged behavior was negatively related to turnover intentions (r = −0.27, p =0.001). Frustrated behavior was not significantly related to turnover intentions (r = 0.05, p =0.237). Intimate behavior was negatively related to turnover intentions (r = −21, p =0.001).

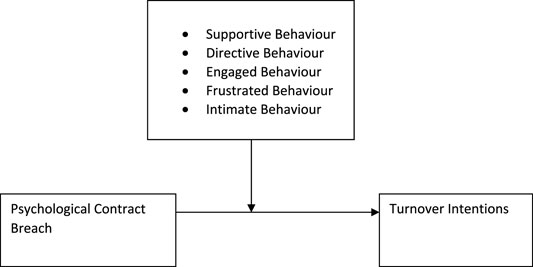

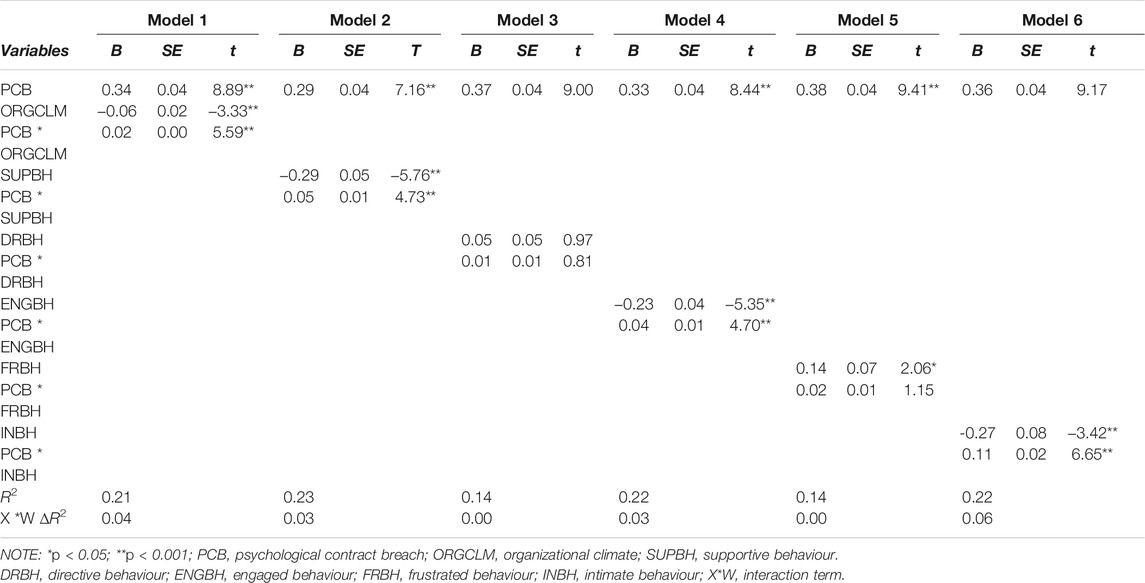

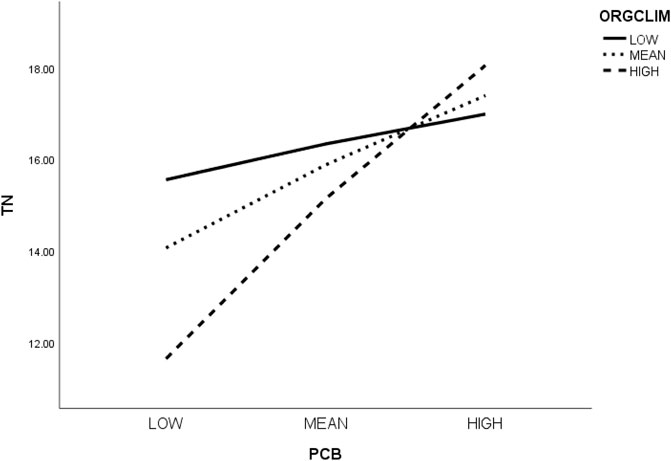

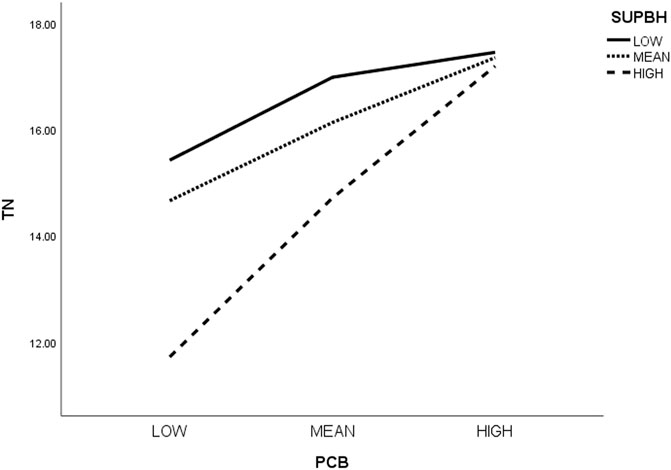

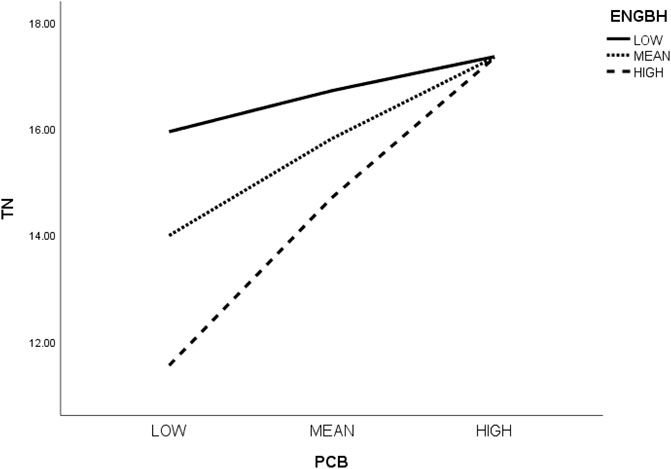

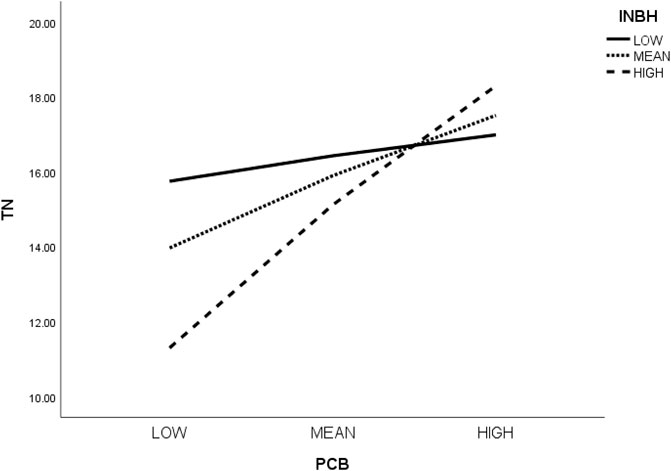

According to the Hayes Process regression results in Table 2, psychological contract breach exhibited a strong positive link with turnover intentions (B =0.344, t = 8.983, p < 0.001). The composite organizational climate revealed a substantial negative connection with turnover intentions (B = −0.059, t = −3.328, p < 0.001). Organizational climate substantially affected the relationship between psychological contract breach and turnover intentions (B =0.022, t = 5.588, p.001) (see Figure 2). Organizational climate (supportive behavior) was shown to have a substantial negative connection with turnover intentions (B = −0.288, t = −5.757, p < 0.001). Organizational climate (supportive behavior) substantially moderated the connection between psychological contract breach and turnover intentions (B =0.008, t = 4.731, p.001) (see Figure 3). There was no significant link between organizational climate (directive behavior) and turnover intentions (B =0.046, t =0.965, p =0.335). Organizational climate (directive behavior) did not affect the relationship between psychological contract breach and turnover intentions (B =0.008, t =0.811, p =0.418). Organizational climate (engaged behavior) was shown to have a substantial negative link with turnover intentions (B = −0.226, t = -5.351, p < 0.001). Organizational climate (engaged behavior) moderated the link between psychological contract breach and turnover intentions (B =0.044, t = 4.701, p < 0.001) (see Figure 4). The organizational climate (frustrated behavior) significantly positively links turnover intentions (B =0.142, t = 2.056, p =0.040). There was no significant moderating connection between psychological contract breach and turnover intentions in the presence of organizational climate (frustrated behavior) (B =0.016, t = 1.149, p =0 .251). Organizational climate (intimate conduct) was shown to have a significant negative connection with turnover intentions (B = −0.270, t = −3.416, p < 0.001). The link between psychological contract breach and turnover intentions was strongly affected by organizational climate (intimate behavior) (B =0.105, t = 6.647, p < 0.001) (see Figure 5).

TABLE 2. Hayes process regression predicting turnover intentions and testing moderating role of organizational climate.

FIGURE 2. Moderating role of organizational climate in the psychological contract breach and turnover intention relations.

FIGURE 3. Moderating role of organizational climate (supportive behavior) in the psychological contract breach and turnover intentions relations.

FIGURE 4. moderating role of organizational climate (engaged behaviour) in the psychological contract breach and turnover intentions relations.

FIGURE 5. The moderating role of organizational climate (intimate behaviour) in the psychological contract breach and turnover intentions relations.

Figure 2 shows that those with high organizational climate and high psychological contract breach had higher turnover intentions than those with lower organizational climate and higher psychological contract breaches (Table 3).

Figure 3: the moderating role of organizational climate (supportive behavior) in the psychological contract breach and turnover intentions relations. Figure 3 shows that those with lower organizational climate and high psychological contract breach had higher turnover intentions than those with higher organizational climate and lower psychological contract breach (Table 4).

Figure 4: the moderating role of organizational climate in the psychological contract breach and turnover intention relations. Figure 4 shows that those with lower organizational climate (engaged behavior) and high psychological contract breach had higher turnover intentions than those with higher organizational climate and lower psychological contract breach (Table 5).

Figure 5 demonstrates that individuals with a higher organizational environment (intimate behavior) and a more significant psychological contract breach had a greater desire to leave than those with a lower organizational climate and a higher psychological contract breach (Table 6).

Discussion

This study examined the association between psychological contract breach and intention to leave among academics at private institutions. However, perhaps more crucially, we must investigate the moderating influences of organizational climate characteristics on proven associations. The first hypothesis was accepted because it posited that psychological contract breach would be a strong positive predictor of turnover intentions among lecturers at private institutions (H1 confirmed). This result supports the earlier findings (Robinson and Rousseanm, 1994; Robinson & Morrison, 1995; Roehling, 1997; Turnley and Feldman, 2008; Munda and Agarwal 2010; Bal et al., 2013; Umar and Ringim, 2015). This study reported that psychological contract breaches positively predicted turnover intentions among employees. The findings revealed that private university academics become unsatisfied with their jobs, unsatisfied with management and organizations when they believe the organization has broken its commitment and inspired to look for another career. This finding could explain the result on the premise of “give and take”. Most employees perceive private establishments as business ventures where they get paid based on their put-in. In this instance, most lecturers at private institutions are motivated by the prospect of financial compensation in exchange for their services. This result explains the law of reciprocity that Blau (1964) espoused in social exchange theory. On this premise, if the contract fails, the intention to quit rises among lecturers.

We also hypothesized that organizational climate dimensions would significantly predict turnover intentions among lecturers in private universities. Organizational climate (composite) revealed a substantial negative connection with turnover intentions (H2 confirmed). The result of the study supports earlier findings (Chau et al., 2009; Hughes et al., 2010; Saungweme and Gwandure, 2011; Jeswani and Dave, 2012; Gosserland, 2003; Mei Teh, 2014; Awang et al., 2015). It discovered a negative association between organizational climate and lecturers’ inclinations to leave. According to the findings, a great corporate environment connects with a low desire to leave among academics. Lecturers in private universities can be encouraged or motivated to stay by introducing a free flow of communication, improved work facilities and conditions, improved pay package, administrative support, and adequate promotion (Hughes, 2012). These may raise work happiness, improve performance, and lower the likelihood of these lecturers quitting. However, the absence of these makes the job tedious and stressful. According to Kim et al. (2020), a failure to handle stress effectively may lead to turnover intentions and, in some cases, actual turnover.

Among the dimensions of organizational climate, we hypothesized that supportive behavior would significantly predict turnover intentions among lecturers in private universities. According to the study’s findings, the corporate environment (supportive behavior) showed a strong negative link with turnover intentions (H2a confirmed). The result showed that supportive leadership behavior from the university authorities has a negative association with lecturers’ intent to quit their jobs. This finding supports the argument that an employer’s support for an employee benefits the employee’s welfare and comfort in that company. When employees receive support from the management, they feel warm, relaxed, and show a sense of belonging, reducing their quest or intent to quit such an organization. We had expected that directive behavior would significantly predict turnover intentions among lecturers in private universities and did not support this hypothesis. There was no substantial link between organizational climate (directive conduct) and turnover intentions (H2b not confirmed). The organizational climate (engaged behavior) identified strong moderation in the connection between psychological contract breach and turnover intention (H2c verified) (see Figure 4). Engaged behavior reflects by high morale when lecturers are engaged in work-related activities in their universities, they tend to think less of quitting their jobs. Lecturers that exhibit engaged behaviors are usually concerned about the welfare and success of students and co-workers. They are friendly with their students and believe in their students’ potential to achieve. In private universities, lecturers are cooperative and supportive, primarily because of their small population. These lecturers come together as a collective unit engaged and committed to the teaching-learning task. The more committed to their jobs the lecturers are, the less likely their intent to quit. Engagement is an act of commitment, vigor, enthusiasm, and loyalty needed in times of distrust and betrayal to suppress the intention to leave.

Our finding that frustrating behavior predicted turnover intentions among lecturers in private universities is consistent with prior research findings (Ansari et al., 2012; Ghamrawi and Jammal, 2013). The results of the study supported the stated hypothesis that there would be a positive relationship between psychological contract breach and intention to leave. Organizational climate (frustrated behavior) explained a substantial positive link with the intent to leave (H2d confirmed). This result supports the assertion that a frustrated employee tends to leave a frustrating environment. When there are too many frustrating demands from lecturers by the management, these lecturers feel uncomfortable with the organizational climate and may likely nurse the intent to quit their job. Such frustrated behaviors may include abusive supervision, interference in teaching tasks, harsh routine requirements, burdensome administrative paperwork, non-teaching duties, etc. Our data shows a negative relationship between intimate conduct and turnover intentions (H2e confirmed). This result is consistent with Gormley, (2005) earlier study findings, which indicated a significant negative association between closeness and turnover intentions. This result suggests that level of closeness that exists among lecturers and co-workers or students in universities does necessarily influence one’s intent to quit or not. This social interaction that explains intimate behavior sometimes determine who amongst them decides to stay or quit the job. Personal behavior is part of the normal socialization process in work settings that members of such an organization are bound to share in one way or another. In African culture, there is always a solid and cohesive network of social interaction among people. Lecturers know their students by their names and relate intimately with their co-lecturers, explaining social interaction (intimate behavior). This pattern of life is rooted in culture and traverses across every social setting, work organizations inclusive. Therefore, even when a lecturer leaves one university for another, the collective lifestyle that encourages socialization will continue. This social interaction goes to a large extent to determine or guarantee whether they will stay or quit. This social activity might explain why intimate behavior predicted turnover intentions among lecturers in private universities.

However, the organizational environment (supportive behavior) could not reduce the connection between psychological contract breach and turnover intentions (H3a confirmed) (see Figure 3). Therefore, in psychological contract violation, supportive leadership behavior is the coolant that suppresses turnover intentions among lecturers in private universities. The climate-the openness of the supportive leaders cushions the adverse reactions of the aggrieved lecturers.

Furthermore, there was no significant moderating influence of the corporate environment (directive behavior) on the association between psychological contract breach and turnover intentions (H3b not confirmed). High directive behavior is all about rigid and domineering leadership within the universities where the authorities are autocratic, create panic and scare their followers or subordinates. However, this study showed that directive behaviors did not moderate the association between psychological contract breach and turnover intentions. This could be the case because the workers do not trust the management nor believe in their promises. Their previous experiences must have played a role in the non-significant relationship between psychological contract breach and turnover intentions.

Also, engaged behavior significantly moderated the relationship between psychological contract breach and turnover intentions (H3c).

However, there was no significant moderating association between psychological contract breach and turnover intentions when organizational climate (frustrated behavior) was included (H3d not confirmed).

The link between psychological contract breach and turnover intentions was strongly affected by the organizational atmosphere (intimate behavior) (H3e confirmed) (see Figure 5). In the context of a psychological contract breakdown, intimate conduct repels turnover intentions.

Practical Implications

The current study’s findings have several implications. Several deductions can be made that can benefit future researchers, policymakers, stakeholders, employers of labor, and workers in the educational sector. First, the study provides insight into variables that either promote or stimulate turnover intentions among employees in private universities (in South-East Nigeria) as a sample. Psychological contract breach predicted turnover intentions far more optimistically. This finding could explain this present result on the premise that unfulfilled promises boomerang on the violators of such commitment. Turnover intention is an emotional state that signals an unfavorable environment; therefore, it may not be surprising that management that breaks a contract or agreement may likely face the exit of its employees. A working contract states that you (employee) will receive payment in return for the services rendered. The expectation is that both parties should follow any agreement reached. Management’s breach or, contract violation demands activities such as a dispute, unproductive work behavior, neglect of tasks, sabotage, insubordination, and discontent, all of which generate turnover intentions or actual turnover. Organizations that engage in breach or violation of organizational contracts should also expect the exit of their employees, particularly in our private educational sector (universities, polytechnic, college of education, secondary schools, etc.) or other sectors where there are alternatives. Besides, this exit or intent to quit does no good to the management because the cost of replacing and training new personnel is high. An organization that surrounds itself with uncertainties faces an unexpected departure of its employees. When employees see themselves as “partners in the agreement,” they could go the extra mile to protect that agreement.

Managerial Implications

Personnel policies, working conditions, and decision-making involvement may all be said to dependably make up the corporate environment. Using academics in private institutions in south-eastern Nigeria, studies have revealed that workers’ turnover intentions are a product of the atmosphere in the company in which they work in the Nigerian setting. A positive organizational environment improves an organization’s performance, production, and employee satisfaction. Breach of psychological contract will threaten employee wellbeing in the workplace. In that case, there’s a need for the management to reintroduce the sense of trust, safety, and belongingness among employees to repel turnover intentions. Understanding the dynamics of links and the consequences of the influences between organizational climate dimensions (factors) and turnover intentions is critical for organizational development. This study revealed supportive, engaged, and intimate behaviors as modifiers in the connection between psychological contract breach and turnover intentions among lecturers at Nigerian private institutions, among other characteristics of the organizational environment. These behaviors encourage the lecturers to remain and overcome trial periods in the work domain. A favorable climate harbors an organism, while unfavorable weather drives it away. So it could be in many organizations, university environment inclusive. Organizations and managers should be aware of the link between organizational fairness and work results. Organizations (universities, hospitals, firms, industries, banks, etc.) should practice supportive behaviors that favor workers because they will strengthen their willingness to remain in such organizations. Such supportive behaviors include a good personnel welfare package, encouraging and motivating organizational policies (e.g., awards), providing financial assistance in related academic programs. Such behaviors will improve the standard and image of our Nigerian organizations. Our lecturers should embrace engaged and intimate behavior because they provide social relief through interaction and communication in difficult times.

Again, about career development, these scholars working in private universities develop their academic careers by researching, publishing articles and textbooks relevant to their specialties, attending conferences and various workshops, engaging in administrative roles within academic and higher education—these academic exercises gear towards career development. Doctoral students, postdoctoral researchers, and other multiple ranks attain personal goals and receive tangible rewards such as promotions for their intellectual abilities and contributions. These career development practices in academics prepare them for a more significant task ahead in challenging times, particularly during unfulfilled contracts from the management.

Supportive, engaged, and intimate work behaviors from the management and lecturers will help provide the necessary techniques to help aggrieved lecturers cope in tension-soaked situations and sustain their jobs. Having developed in ranks and status through academic exposure, these lecturers opt to public institutions where the management will keep the agreement’s terms. They can also tarry in such challenging and unfavorable conditions hoping to become part of the management team sometime in the future by clinging on to some administrative roles and positions such as heads of departments, deans, and members of the senate and appraisal board. In other words, it is the social or economic benefits from the work environment that defines the position of the lecturer in the university.

In summary, these lecturers in private universities give and receive from the system that determines their intent to stay or leave. This belief gives credence to the hypothesized social exchange theory. These thoughts of challenging conditions and uncertainties in the universities bedevil the quest to stay. When there is the perception of lack of trust, safety, and sense of belongingness from the management, it spurs the individuals (lecturers) to struggle for survival academically. Specifically, this struggle for survival is the driving force that propels them to the summit of their career.

During an interview in a newspaper report (Premiumtimes, December 1 Agency Reporting, 2016), the respondents indicated an unfulfilled agreement (e.g., epileptic appraisal and promotion process, irregular payment of salaries, poor welfare packages, work entitlements, job insecurity, heavy work pressure/overload, and poor academic infrastructures) created a sense of fear, distrust, and imbalance in the employment exchange equation and high turnover in privately owned universities. These lecturers attributed these negative changes and uncertainties in private universities to the management’s poor administrative and leadership qualities. It creates and defines the regular pathway that turnover intentions ply. Management needs to reintroduce trust, honesty, and confidence to reform the perception of these lecturers among their employees by redefining the purpose and ideology of the university. By so doing, the management will restore the reputation and integrity of these universities.

Limitations and Future Directions

The study noted drawbacks such as the focus on private universities. As a result, the study paves the way for further research possibilities to broaden knowledge at other private institutions, i.e., polytechnics, and colleges of education compared to government owned institutions. Literature has suggested that the organizational climates between private and public universities could differ due to their cultural variations. Furthermore, we selected these private universities at random from the country’s south-eastern region. Other researchers can obtain a more reliable result with further investigations in this area using samples drawn from the country’s six geo-political zones. Again, the nature of this study did not give room to determine causal effect among the variables.

Conclusion

This study expands on previous research by investigating the moderating impacts of organizational climate variables on the correlations between psychological contract breach and turnover intentions. Experience and observation as insiders have shown us that private universities in south-eastern Nigeria are drilling grounds where young applicants who nurse the ambition of becoming lecturers develop themselves for better lecturing opportunities in public universities. These young employees (lecturers), who often become assistant lecturers, strive to create academic wisdom. They develop, equip, and enrich themselves through teaching experiences, publications, improved job status, educational programs, conferences, workshops, and seminar presentations. After some years of academic training, having nursed their intentions to leave, they go to public universities for greener pastures with less workload, better pay packages, job security, and a conducive work/organizational environment. Private university authorities are highly encouraged to be supportive and flexible with rules and decisions affecting the welfare of lecturers. Lecturers need to feel valued, and their opinions should be sought and incorporated into decisions or policies.

In contrast, the organizational culture of in other parts of the world differ significantly from Nigeria, as scholars envy private universities for their academic pedigree, exploits, excellence, and achievements in other parts of the world like Europe, Asia, and American. Therefore, lecturers in private universities, particularly those located in the southeast, strive to develop academic wise and relocate to the public (federal and state) universities for greener pastures where they feel satisfied, fulfilled, and above all self-accomplished. This action is mainly due to flawed management principles from private universities, leading to many unfulfilled contracts with their employees.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Research and Publication Ethics Department, Coal City University Enugu Nigeria. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

GCK initiated the first draft; LEU developed and conducted data analysis; FAO collected data for the study; IU reviewed the draft; MAE collected data; AE; reviewed the draft; CO collected data and review of the draft; MA collected data and interpreted the result; LIU reviewed the draft and interpretation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adeniji, A., Salau, O., Awe, K., and Oludayo, O. (2018). Survey Datasets on Organisational Climate and Job Satisfaction Among Academic Staff in Some Selected Private Universities in Southwest Nigeria. Data Brief 19, 1688–1693. doi:10.1016/j.dib.2018.06.001

Adeniji, A. A. (2011). “Organizational Climate and Job Satisfaction Among Academic Staff in Some Selected Private Universities in Southwest Nigeria,” Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis in Industrial Relations and Human Resource Management (Nigeria: Department of Business Studies, Covenant University).

Adenike, A. (2011). Organizational Climate as a Predictor of Employee Job Satisfaction: Evidence from Covenant University. Business Intelligence J. 4 (1), 151–165.

Adeyemi, T. O. (2008). Organizational Climate and Teachers Job Performance in Primary Schools in Ondo State, Nigeria: An Analytical Survey. Asian J. Inf. Tech. 7 (4), 138–145.

Afolabi, O. A. (2005). Influence of Organizational Climate and Locus of Control in Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intentions. IFE Psychol. 13 (2), 102–113. doi:10.4314/ifep.v13i2.23690

Agency Reporting (2016). Nigeria’s Private Universities Lack Quality Teachers, Times Higher Education. Professors Say. Premium times. Available at: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/216874-nigerias-private-universities-lack-quality-teachers-professors-say.html.

Agyemang, C. B. (2013). Perceived Organizational Climate and Organizational Tenure on Organizational Citizenship Behaviour: Empirical Study Among Ghanaian Banks. Eur. J. Business Manag. 5 (26), 132–142.

Ahmad, T., and Riaz, A. (2011). Factors Affecting Turnover Intentions of Doctors in Public Sector Medical Colleges and Hospitals. Interdiscip. J. Res. Business 1 (10), 57–66.

Ahmed, E., and Muchiri, M. (2014). Effects of Psychological Contract Breach, Ethical Leadership and Supervisors' Fairness on Employees' Performance and Wellbeing. Wjm 5 (2), 1–13. doi:10.21102/wjm.2014.09.52.01

Ajadi, T. O., Salawu, I. O., and Adeoye, F. A. (2008). E-learning and Distance Education in Nigeria. Online Submission 7 (4). Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED503472.pdf.

Ali, N. (2008). Factors Affecting Overall Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intentions. J. Managerial Sci. 20 (2), 210–240.

Alo, E. A., and Dada, D. A. (2020). Employees' Turnover Intention: A Survey of Academic Staff of Selected Private Universities in Ondo State. Nigeria. Int. J. Scientific Res. Publications 10 (2), 263–268. doi:10.29322/ijsrp.10.02.2020.p9837

Ambrose, M. L., Seabright, M. A., and Schminke, M. (2002). Sabotage in the Workplace: The Role of Organizational Injustice. Organizational Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 89, 947–965. doi:10.1016/s0749-5978(02)00037-7

Ansari, M. A., Aafagi, R., and Sim, C. M. (2012). Turnover Intentions and Political Influence Behaviour: A Test of "Fight-Or-Flight" Responses to Organizational Injustice. FWU. J. Soc. Sci. Winter 6 (2), 99–108.

Aquino, K., Galperin, D., and Benneth, A. (2004). Integrating justice Constructs into the Turnover Process: A Test of a Referent Cognitions Model. Acad. Manage. J. 40, 1208–1227. doi:10.5465/256933

Awang, A., Ibrahim, I. I., Nor, M. N. M., Arof, Z. M., and Rahman, A. R. A. (2015). Academic Factors and Turnover Intention: Impact of Organization Factors. Higher Edu. Stud. 5 (3), 24–44. doi:10.5539/hes.v5n3p24

Aykan, E. (2014). Effects of Perceived Psychological Contract Breach on Turnover Intention: Intermediary Role of Loneliness Perception of Employees. Proced. - Soc. Behav. Sci. 150, 413–419. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.09.040

Bal, P. M., De Cooman, R., and Mol, S. T. (2013). Dynamics of Psychological Contracts with Work Engagement and Turnover Intention: The Influence of Organizational Tenure. Eur. J. Work Organizational Psychol. 22 (1), 107–122. doi:10.1080/1359432x.2011.626198

Bamberger, P., Kohn, E., and Nahum-Shani, I. (2008). Aversive Workplace Conditions and Employee Grievance Filing: the Moderating Effects of Gender and Ethnicity. Ind. Relations 47, 229–259. doi:10.1111/j.1468-232x.2008.00518.x

Berberoglu, A. (2018). Impact of Organizational Climate on Organizational Commitment and Perceived Organizational Performance: Empirical Evidence from Public Hospitals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 18 (399), 399–9. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3149-z

Bhat, S. A., and Bashir, H. (2016). Influence of Organizational Climate on Job Performance of Teaching Professionals: An Empirical Study. Int. J. Edu. Manag. Stud. 6 (4), 445–448.

Bhat, S. A. (2013). Influence of Organizational Climate and Social Adjustment on Job Performance of Teaching and Non-teaching Professionals. Edu. Dev. 3 (1), 420–424.

Bluedorn, A. C. (1982). A Unified Model of Turnover from Organizations. Hum. Relations 35, 135–153. doi:10.1177/001872678203500204

Carmeli, A., and Vinarski-Peretz, H. (2010). Linking Leader Social Skills and Organisational Health to Positive Work Relationships in Local Governments. Local Government Stud. 36, 151–169. doi:10.1080/03003930903435872

Carr, J. Z., Schmidt, A. M., Ford, J. K., and DeShon, R. P. (2003). Climate Perceptions Matter: A Meta-Analytic Path Analysis Relating Molar Climate, Cognitive and Affective States, and Individual Level Work Outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 88 (4), 605–619. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.4.605

Chau, S. L., Dahling, J. J., Levy, P. E., and Diefendorff, J. M. (2009). A Predictive Study of Emotional Labor and Turnover. J. Organiz. Behav. 30, 1151–1163. doi:10.1002/job.617

Chernyak-Hai, L., and Tziner, A. (2014). Relationships between Counterproductive Work Behavior, Perceived justice and Climate, Occupational Status, and Leader-Member Exchange. Revista de Psicología Del. Trabajo y de Las Organizaciones 30, 1–12. doi:10.5093/tr2014a1

Cohen, J., McCabe, E. M., Michelli, N. M., and Pickeral, T. (2009). School Climate: Research, Policy, Practice, and Teacher Education. Teach. Coll. Rec. 111, 180–213. doi:10.1177/016146810911100108

Conley, S., and You, S. (2018). School Organizational Factors Relating to Teachers' Intentions to Leave: A Mediator Model. Curr. Psychol. 40, 379–389. doi:10.1007/s12144-018-9953-0

Coyle-Shapiro, J. A. M., and Kessler, I. (2000). ‘Consequences of the psychological contract for the employment relationship: a large-scale survey’. J. Manag. Stud. 37 (7), 903–930.

Diefendorff, J. M., and Gosserand, R. H. (2003). Understanding the emotional labor process: A control theory perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 24 (8), 945–959.

Domitrovich, C. E., Li, Y., Mathis, E. T., and Greenberg, M. T. (2019). Individual and Organizational Factors Associated with Teacher Self-Reported Implementation of the PATHS Curriculum. J. Sch. Psychol. 76, 168–185. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2019.07.015

Douglas, S. C., and Martinko, M. J. (2001). Exploring the Role of Individual Differences in the Prediction of Workplace Aggression. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 547–559. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.4.547

Freese, C. (2007). Organizational Change and the Dynamics of Psychological Contracts: A Longitudinal Study. Ph.D. Dissertation (Tilburg, Netherlands: Tilburg University).

Ghamrawi, N., and Jammal, K. (2013). Teacher turnover: Impact of school leadership and other factors. Int. J. Math. Educ. Sci. Technol. 4 (1), 68–78.

Gheisari, F., Sheikhy, A., and Salajeghe, S. (2014). Explaining the Relationship between Organizational Climate, Organizational Commitment, Job Involvement, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior Among Employees of Khuzestan Gas Company. Int. J. Appl. Oper. Res. 4 (4), 27–40.

Gormley, D. K. (2005). Factors Affecting Job Satisfaction in Nurse Faculty: A Meta-Analysis. J. Nurs. Edu. 42 (4), 174–178. doi:10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n20p2986

Greenberg, P. E., Kessler, R. C., Birnbaum, H. G., Leong, S. A., Lowe, S. W., Berglund, P. A., et al. (2003). The Economic burden of Depression in the United States: How Did it Change between 1990 and 2000? J. Clin. Psychiatry 64, 1465–1475. doi:10.4088/jcp.v64n1211

Haq, A. V., Khattak, A. I., Shah, S. N. R., and Rehman, K. (2011). Organizational Environment and its Impact on Turnover Intentions in the Education Sector of Pakistan. J. Business Manag. 3 (2), 118–122.

Harder, A., Gouldthorpe, J., and Goodwin, J. (2015). Exploring Organizational Factors Related to Extension Employee Burnout. J. Extension 53 (2), 1–20. Available at: https://www.joe.org/joe/2015april/a2.php.

Harris, L., and Ogbonna, E. (2002). Leadership Style, Organizational Culture, and Performance: Empirical Evidence from U.K. Companies. Int. Hum. Resource Manag. 11 (4), 766–788.

Hartini, S., Arini, C., Dini, S., and Sulim, E. (2020). Turnover Intention in Terms of Organizational Climate in Marketing Employees. Int. Conf. Cult. Heritage, Educ. Sust. Tourism, Innovation Tech., 361–367. doi:10.5220/0010311903610367

Hayes, A. F. (2014). Comparing Conditional Effects in Moderated Multiple Regression: Implementation Using PROCESS for SPSS and SAS. Available at: http://www.afhayes.com/public/comparingslopes. Pdf (Accessed Nov 23, 2017).

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Herriot, P., Manning, W. E. G., and Kidd, J. M. (1997). The Content of the Psychological Contract. Br. J. Manag. 8, 151–162. doi:10.1111/1467-8551.0047

Hughes, G. D. (2012). Teacher Retention: Teacher Characteristics, School Characteristics, Organizational Characteristics, and Teacher Efficacy. J. Educ. Res. 105 (4), 245–255. doi:10.1080/00220671.2011.584922

Hughes, L. W., Avey, J. B., and Nixon, D. R. (2010). Relationship between Leadership and Followers Getting Intentions and Job Search Behaviour. J. Leadersh. Organizational Stud. 20, 1–12. doi:10.1177/1548051809358698

Idogho, P. O. (2006). Academic Staff Perception of the Organizational Climate in Universities in Edo State, Nigeria. J. Soc. Sci. 13 (1), 71–78. doi:10.1080/09718923.2006.11892533

Jeswani, S., and Dave, S. (2012). Impact of Organizational Climate on Turnover: An Empirical Analysis on Faculty Members of Technical Education of India. Int. J. Business Manag. Res. 2 (3), 26–44.

Kanten, P., and Ülker, F. E. (2013). The Effect of Organizational Climate on Counterproductive Behaviors: An Empirical Study on the Employees of Manufacturing Enterprises. Macrotheme Rev. A Multidisciplinary J. Glob. Macro Trends 2 (4), 144–160.

Kasekende, F., Munene, J. C., Ntayi, J. M., and Ahiauzu, A. (2015). The Interaction Effect of Social Exchanges on the Relationship between Organizational Climate and Psychological Contract. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 36 (7), 833–848. doi:10.1108/lodj-01-2014-0007

Kiewitz, C., Restubog, S. L. D., Zagenczyk, T., and Hochwarter, W. (2009). The Interactive Effects of Psychological Contract Breach and Organizational Politics on Perceived Organizational Support: Evidence from Two Longitudinal Studies. J. Manag. Stud. 46 (5), 806–834. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2008.00816.x

Kim, J., Shin, Y., Tsukayama, E., and Park, D. (2020). Stress Mindset Predicts Job Turnover Among Preschool Teachers. J. Sch. Psychol. 78, 13–22. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2019.11.002

Kottkamp, R. B., Mulhern, J. A., and Hoy, W. K. (1987). Secondary School Climate: A Revision of the OCDQ. Educ. Adm. Q. 23 (3), 31–48. doi:10.1177/0013161x87023003003

Kumar Mishra, S., and Bhatnagar, D. (2010). Linking Emotional Dissonance and Organizational Identification to Turnover Intention and Emotional Well-Being: A Study of Medical Representatives in India. Hum. Resour. Manage. 49 (3), 401–419. doi:10.1002/hrm.20362

Kyari, S. S., Adiuku-Brown, M. E., Abachi, H. P., and Adelakun, R. T. (2018). E-learning in Tertiary Education in Nigeria: Where Do We Stand? Int. J. Edu. Eval. 4 (9), 1–10. Available at: www.llardpub.org.

Liou, S.-R., and Cheng, C.-Y. (2010). Organisational Climate, Organisational Commitment and Intention to Leave Amongst Hospital Nurses in Taiwan. J. Clin. Nurs. 19, 1635–1644. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03080.x

Mei Teh, G. (2014). Impact of Organizational Climate on Intentions to Leave and Job Satisfaction. Wjm 5 (2), 14–24. doi:10.21102/wjm.2014.09.52.02

Morrison, E. W., and Robinson, S. L. (1997). When Employees Feel Betrayed: a Model of How Psychological Contract Violation Develops. Amr 22, 226–256. doi:10.5465/amr.1997.9707180265

Munda, S. S., and Agarwal, M. (2010). Workplace Factors, Psychological Contract Fulfillment and Turnover Intentions of Medical Professionals in the Private Healthcare Sector. Am. J. Nurs. 104 (5), 50–58.

Nwankwo, B. E., Agu, S. A., Onwukwe, L., Sydney-Agbor, N., and Ebeh, R. (2015). Relationship between Organizational Climate, Organizational Support, Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Taking Charge. Psychol. Soc. Behav. Res. 3 (2), 30–35.

Okoli, I. E. (2019). Organizational Climate and Job Satisfaction Among Academic Staff: Experience from Selected Private Universities in Southeast Nigeria. Int. J. Res. Business Stud. Manag. 5 (12), 36–48.

Puspitawati, N. M. D., and Atmaja, N. P. C. D. (2019). The Effect of Organizational Climate on Turnover Intention with Organizational Commitment as Mediating Variable. J. Int. Conf. Proc. 2 (1), 1–13.

Raja, S., Madhavi, C., and Sankar, S. (2019). Influence of Organizational Climate on Employee Performance in Manufacturing Industry. Suraj Punj J. Multidisciplinary Res. 9 (3), 146–157. doi:10.24247/ijhrmrapr20198

Robinson, S. l., and Greenberg, J. (1998). Trends in Organizational Behaviour. New York: John Wiley.Employee Behaving Badly: Dimensions, Determinants, and Dilemmas in the Study of Work Workplace Deviance

Robinson, S. L., and Morrison, E. W. (1995). Psychological Contracts and OCB: The Effect of Unfulfilled Obligations on Civic Virtue Behavior. J. Organiz. Behav. 16, 289–298. doi:10.1002/job.4030160309

Robinson, S. L., and Morrison, E. W. (2000). The development of psychological contract breach and violation: A longitudinal study. J. Organ. Behav. 21 (5), 525–546. doi:10.1002/1099-1379(200008)21:5<525::AID-JOB40>3.0.CO;2-T

Robinson, S. L., and Rousseau, D. M. (1994). Violating the Psychological Contract: Not the Exception but the Norm. J. Organiz. Behav. 15 (3), 245–259. doi:10.1002/job.4030150306

Robinson, S. L. (1996). Trust and Breach of the Psychological Contract. Administrative Sci. Q. 41, 574–599. doi:10.2307/2393868

Roehling, M. V. (1997). The Origins and Early Development of the Psychological Contract Construct. Jnl Mgmt Hist. (Archive) 3, 204–217. doi:10.1108/13552529710171993

Rousseau, D. M. (1990). New Hire Perceptions of Their Own and Their Employer's Obligations: A Study of Psychological Contracts. J. Organiz. Behav. 11, 389–400. doi:10.1002/job.4030110506

Rousseau, D. M. (1995). Psychological Contracts in Organizations: Understanding Written and Unwritten Agreements. Thousand Oaks. C.A: Sage.

Saungweme, R., and Gwandure, C. (2011). Organisational Climate and Intent to Leave Among Recruitment Consultants in Johannesburg, South Africa. J. Hum. Ecol. 34 (3), 145–153. doi:10.1080/09709274.2011.11906379

Schneider, B., Bowen, D. E., Ehrhart, M. G., and Holcombe, K. M. (2000). “The Climate for Service: Evolution of a Construct,” in Handbook of Organizational Culture and Climate. Editors N. M. Ashkanasy, C. P. Wilderom, and M. F. Peterson (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 21–36.

Shen, Y., Schaubroeck, J. M., Zhao, L., and Wu, L. (2019). Work Group Climate and Behavioral Responses to Psychological Contract Breach. Front. Psychol. 10 (67), 67–13. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00067

Sims, R. (2002). Human Resource Management's Role in Clarifying the New Psychological Contract. Hum. Resour. Manag. 33, 373–382. doi:10.1177/1350507602332016

Sousa-Poza, A., and Henneberger, F. (2002). Analyzing Job Mobility with Job Turnover Intentions: An International Comparative Study. Res. Inst. Labour Econ. Labour L. 82, 1–28.

Subramanian, I. D., and Shin, Y. N. (2013). Perceived Organizational Climate and Turnover Intention of Employees in the Hotel Industry. World Appl. Sci. J. 22 (12), 1751–1759.

Terera, S. R. (2019). Organizational Climate, Psychological Contract Breach and Employee Outcomes Among university Employees in Limpopo Province: Moderating Effects of Ethical Leadership and Trust. Unpublished manuscript. Cape Town: Department of Human Management and Labour Relations School of Management of Sciences, University of Venda.

Thomas, P., Wolper, P., Scott, K., and Jones, D. (2001). The Relationship between Immediate Turnover and Employee Theft in the Restaurant Industry. J. Business Psychol. 15, 561–577.

Tsai, C.-l. (2014). The Organizational Climate and Employees' Job Satisfaction in the Terminal Operation Context of Kaohsiung Port1. The Asian J. Shipping Logistics 30 (3), 373–392. doi:10.1016/j.ajsl.2014.12.007

Turan, S. (1998). “Measuring Organizational Climate and Organizational Commitment in the Turkish Educational Context,” in Paper presented at the University Council for Educational Administration's Annual Meeting, October 29-November 1, 1998 (St. Louis, Missouri, USA.

Turnley, W. H., and Feldman, D. C. (2008). Psychological Contract Violations during Corporate Restructuring. Hum. Resource Manag. 37, 71–83. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-050x(199821)37:1<71:aid-hrm7>3.0.co;2-s

Turnley, W. H., and Feldman, D. C. (2000). Re-examining the Effects of Psychological Contract Violations: Unmet Expectations and Job Dissatisfaction as Mediators. J. Organiz. Behav. 21 (1), 25–42. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-1379(200002)21:1<25:aid-job2>3.0.co;2-z

Umar, S., and Ringim, K. J. (2015). “Psychological Contract and Employee Turnover Intention Among Nigerian Employees in Private Organizations,” in Management International Conference28-30 May (Portoroz, Slovenia, 219–229.

Vardi, Y. (2001). The Effect of Organizational and Ethical Climates in Misconduct at Work. J. Business Ethics 29, 325–337. doi:10.1023/a:1010710022834

V. Valdez, A., and J. Villa, R. (2019). Personality Traits, Organizational Climate, Leadership Style and Job Satisfaction of Selected Government Employees in Aurora Zamboangadel Sur: A Correlational Study. Ijsms 2 (1), 100–106. doi:10.51386/25815946/ijsms-v2i1p113

Windon, S., Cochran, G., Scheer, S., and Rodriguez, M. (2019). Factors Affecting Turnover Intention of Ohio State University Extension Program Assistants. Jae 60 (3), 109–127. doi:10.5032/jae.2019.03109

Zalat, M. M., Hamed, M. S., and Bolbol, S. A. (2021). The experiences, challenges, and acceptance of e-learning as a tool for teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic among university medical staff. PLoS ONE 16 (3), e0248758. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0248758

Keywords: psychological contract breach, turnover intentions, organizational climate, lecturers, universities

Citation: Kanu GC, Ugwu LE, Ogba FN, Ujoatuonu IV, Ezeh MA, Eze A, Okoro C, Agudiegwu M and Ugwu LI (2022) Psychological Contract Breach and Turnover Intentions Among Lecturers: The Moderating Role of Organizational Climate. Front. Educ. 7:784166. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.784166

Received: 27 September 2021; Accepted: 17 January 2022;

Published: 10 March 2022.

Edited by:

Ana Campina, Infante D. Henrique Portucalense University, PortugalReviewed by:

Gary L. Railsback, Arkansas State University, United StatesFrancis Thaise A. Cimene, University of Science and Technology of Southern Philippines, Philippines

Jun (Justin) Li, China

Copyright © 2022 Kanu, Ugwu, Ogba, Ujoatuonu, Ezeh, Eze, Okoro, Agudiegwu and Ugwu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lawrence E. Ugwu, bGF3LnVnd3VAZ21haWwuY29t

Gabriel C. Kanu1

Gabriel C. Kanu1 Lawrence E. Ugwu

Lawrence E. Ugwu Ikechukwu V. Ujoatuonu

Ikechukwu V. Ujoatuonu