- Institute of Educational Research in the School of Education, University of Wuppertal, Wuppertal, Germany

The social participation of students can be defined as one of the fundamental goals of inclusion. However, current literature shows that (a) children from minorities can belong to groups at risk of low social participation and (b) relatively little is known as yet about changes in social participation over time (longitudinal study). This study therefore seeks to investigate more closely the stability of social participation for students with a migration background. A total of 353 year 4 students (45% girls, including 16% with German as their second language) from North Rhine-Westphalia (Germany) were surveyed about their social participation (friendships, interactions, etc.) using a paper-and-pencil questionnaire at the beginning (September 2018) and at the end (June/July 2019) of a school year. All schools of common learning in North Rhine-Westphalia were contacted and asked to participate voluntarily. Only students who participated in the survey at both measurement points were considered. At the first measurement point, students had an average age of 9 years (SD = 0.42; range 8–11). At the second measurement point, students had an average age of 10 years (SD = 0.57; range 9–12). Student responses were largely in the form of sociometric ratings or sociometric nominations. One finding of the variance analyses (ANOVA with repeated measures) was that, for the most part, there was no difference longitudinally between students with and those without a migration background. However, students with a migration background were found to have significantly fewer stable friendships than their peers. No other differences in relation to changes over time were recorded in any other areas. The findings thus also illustrate that a possible lack of social participation by students with a migration background remains constant, and that the period when students first come into contact with each other appears to be of fundamental importance.

Introduction

Students spend a considerable portion of their childhood/youth at school. In recent years, there has been an increasing research focus on the social aspects (e.g., social participation) of school life alongside academic development. At least since the implementation of UNESCO (1994), the view is that school should not just be a place of education for children; it should also foster socialization through social participation (Koster et al., 2009; Bossaert et al., 2013). Here, for example, reciprocal friendships are of particular importance, as they are considered emotionally supportive (Vaquera and Kao, 2008). Moreover, the consequences of (low) social participation is also reflected in other studies; increased school dropout (Carbonaro and Workman, 2013) or increased contact with locals is related to less discrimination/more identification (Di Saint Pierre et al., 2015).

Nevertheless, within the framework of UNESCO (1994), all children should be considered (e.g., disabled, gifted). Likewise, also children from cultural, linguistic, or ethnic minorities are explicitly mentioned. However, analyses in the context of social participation have studied students from minorities (e.g., special educational needs—SEN, migration background or low socioeconomic status—SES) in particular, but to varying degrees and to a large extent cross-sectional. It is evident from current research that the focus of empirical studies has to date been on the social participation of students with SEN. There has been comparatively little research on students with a migration background (especially in a longitudinal design). Yet these children are particularly important as migration increases in the context of globalization (Hunkler et al., 2015). For example, within the European Union as a whole, the net migration increased continuously between 2008 and 2015 (Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge, 2016), resulting in a new peak in immigration to Germany in 2015 (Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge, 2020). This was mainly due to the high influx of asylum seekers (2.1 million people) and an associated net migration of 1.1 million people (Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge, 2020). In the following years, migration to Germany decreased again, but still remained in the positive range. In 2019, for example, 1.6 million immigrants and 1.2 million emigrants were registered (Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge, 2020). Overall, the population with a migration background in Germany thus grew by around 2.1% in 2019, which means that 26% of the population in Germany currently has a migration background (Destatis Statistisches Bundesamt, 2020a). Looking more closely at students within Germany, it becomes visible that 33% of school students in Germany have a migration background (Destatis Statistisches Bundesamt, 2017); this figure rises to 36% for children of primary school age (Destatis Statistisches Bundesamt, 2017). In light of the significant proportion of students in Germany with a migration background (particularly in the early years of school), equal rights of people with and without a migration background (UNESCO, 1994) and the limited research available, the question arises as to whether or not and to what extent there are currently differences in the social participation of students in Germany, taking into account a longitudinal design. Only in this way is it possible to develop or initiate appropriate intervention programs that counteract possible problems in a targeted and client-specific manner.

Theoretical Background

In the following, a brief definition of social participation is given. Following on from this and oriented toward the structure of the given definition, the findings of the current research literature on the social participation of students with a migration background (including differentiation of the genders) are presented. The following focus of the paper deals with the current state of knowledge on the stability of social participation of students with a migration background and forms the closing of the theoretical background. However, in the context of the discussions on social participation of students with a migration background in this paper, it is important and should be clearly emphasized that some researchers focused on race, while others measured the difference in co-ethnic friendships. The wording in this paper may therefore vary and refer to the wording of each reference. However, this should not imply that the terms used can or should be equated.

Definition of Social Participation

There is no standard definition of social participation. It is often used synonymously with social integration and social inclusion (Koster et al., 2009). According to Koster et al. (2009) and Bossaert et al. (2013), there are four aspects to student social participation: (1) a Student’s relationships and friendships with their classmates; (2) a Student’s interactions and social contact with their classmates; (3) peer acceptance of a student by their classmates and (4) the Student’s own perception of their social inclusion.

Friendships are usually recorded in the literature using student nominations (Schwab, 2015; Hamel et al., 2022): students are generally asked to give their three (Mamas, 2012) to five (Pijl et al., 2011) best friends. Reciprocal friendships appear particularly important here, for, as Vaquera and Kao (2008) outline, this type of friendship seems to provide particular emotional support. In addition to considering the presence of friendships, i.e., a purely quantitative approach to the dimension, it seems that the quality and stability of friendships can also play a crucial role. For example, based on their findings in the context of social participation (of students* with SEN), Avramidis et al. (2018) emphasize the need to focus on quality and stability of friendships as well. Interactions can be understood as verbal and non-verbal communicative behavior (Carter et al., 2007) that occurs at work or during leisure activities (Bossaert et al., 2013). According to Bossaert et al. (2013), the main factors that come under social acceptance are social preferences, social support and social rejections. Bullying processes are also part of social acceptance. Social preference is understood to mean that a student is liked by his or her class, whereas social rejection means that a student is not liked by his or her class. Social support and bullying, on the other hand, explicitly refer to the behavior of the class community toward a student, which can be positive (social support) but also negative (bullying) (Bossaert et al., 2013). Unlike the first three aspects, the final aspect relates to a Student’s own self-perception rather than their peers’ perception of them. Feelings of loneliness also play a role here alongside self-concept and self-perception of acceptance by peers (Bossaert et al., 2013).

Current State of Research on Social Participation of Students With a Migration Background

Referring to friendships, Wittek et al. (2020) demonstrated in their study that students with a migration background and the gender of a peer can have an impact on friendships. In addition, Jugert et al. (2018) describe that ethnic self-identification (host country, dual, or heritage country identification) can also be important for friendship decisions. Based on their findings, they speak, among other things, of ethnic minority students not always necessarily preferring ethnic minority peers (compared to the ethnic majority). The findings on friendship quality, however, seem to be inconsistent. While Grütter et al. (2017) report greater cross-group friendship closeness for students with a migration background, Jänsch and Pupeter (2017) describe that children with a migration background in Germany assess their circle of friends as “negative to neutral” significantly more frequently than peers without a migration background (native German). In this context, Strohmeier et al. (2006) also report that girls’ dyads have a higher quality of friendship than boys’ dyads.

On student interactions, Zander et al. (2019) report in their study that students tend to select peers with the same migration background (student or parent born outside Germany) or of the same gender for interactions. As regards student isolation, however, the findings of Plenty and Jonsson (2017) show that students from the first migration generation are particularly affected by rejection and isolation in the classroom (migration status by region of origin).

On the social acceptance of students with and without a migration background, Krull et al. (2018) report a negative correlation between peer election as neighbor in class/a positive correlation between peer rejection as neighbor in class and children with a migration background (migration status identified by teacher). These findings are supported by Huber et al. (2018). Comparing children with and without a migration background revealed that boys were more positive in their social acceptance of children without a migration background.

In research on self-perception of social inclusion, inconsistent results emerge. While Strohmeier and Doğan (2012) found no difference in loneliness between first and second Turkish immigrant and non-immigrant Austrian youth, Rich Madsen et al. (2016a) explored feelings of loneliness among students with and without a migration background (self-identified ethnicity). It turned out that young people who do not belong to the ethnic majority are probably more affected by loneliness (see also Madsen et al., 2016b) than those who do. This probability decreased in cases where there were more students from the same ethnic background in the class.

Current State of Research on the Stability of Social Participation of Students With a Migration Background

With a focus on the stability of social participation, Jugert et al. (2011) found (in the context of friendships) that Turkish students (at the start of the school year) and German students (in the middle of the school year) tended to prefer friendships with peers of the same ethnic background. However, that preference decreased for both groups over the course of the period investigated (one school year) and was no longer evident by the end of the school year. The decrease was faster amongst students with a Turkish migration background than amongst their peers without a migration background (Germans). In contrasting findings, Aboud et al. (2003) showed that the number of cross-race friendships among primary school students fall as students get older. Similarly, Schneider et al. (2007) report that co-ethnic friendships are more likely to last beyond 6 months than inter-ethnic friendships. To the best of the author’s knowledge and in the light of the current literature, however, there have to date been no findings on the stability of friendship quality or friendship stability for students with and without a migration background.

In regard to interactions, a longitudinal study by Martinovic (2010) found that forming one contact is an important predictor of later contacts, but that how many interethnic contacts people form varies depending on their ethnic background. The age of immigration also appears to be a significant factor. Immigrants who immigrated at a younger age were found to form more interethnic contacts than those who immigrated when they were older. Similarly, the language of the country of immigration also seems important. People who speak the language of the country better were found to have far more interethnic contacts (Martinovic, 2010).

With a focus on social acceptance, Krull et al. (2018) reported in their studies that social rejection appears to be a stable variable. They found that students who were affected by strong rejections in year 1 continued to experience strong rejections in year 2. At the same time, however, they also report that social acceptance can be affected by processes of change between year 1 and year 2. This last conclusion would fit with the findings of Von Marées and Petermann (2010), whose study explored bullying (as an aspect of social acceptance according to Koster et al., 2009; Bossaert et al., 2013; see also Schäfer and Albrecht, 2004 for a longitudinal study).

To the best of the author’s knowledge, there are currently no longitudinal studies of self-perception of social inclusion, with a particular focus on loneliness, for children with a migration background.

Research Questions

The above outline of the current state of research shows that there have to date been very few longitudinal studies of social participation of students with and without a migration background, particularly in primary schools. Studies that look at all four aspects of social participation are also rare in the current research landscape (especially in the German-speaking regions). However, there are indications that language barriers in particular, i.e., the need to learn a new language (that of the country of immigration), are significant for social participation processes (such as interactions; e.g., Martinovic, 2010).

The majority of the (mostly cross-sectional) studies tend to focus on the social participation of students with and without SEN (Koster et al., 2010). Nevertheless, on the basis of the theory and the empirical studies (e.g., Schäfer and Albrecht, 2004; Schneider et al., 2007; Martinovic, 2010) it can be assumed that students with a migration background could be disadvantaged from a longitudinal perspective. Thus, these studies provide indications that differences within the various dimensions of social participation can be assumed for students with and without a migration background. Moreover, it is unclear to what extent the results of the studies presented, most of which were conducted outside the German-speaking world, can be found in Germany.

This study therefore aims to gain first basic longitudinal oriented insights into the current situation of social participation of primary school students with and without a migration background in Germany and to investigate whether first rough longitudinal differences in social participation of the aforementioned student groups can be identified, taking into account all four aspects of social participation (friendships, interactions, social acceptance, self-perception of social inclusion), according to Koster et al. (2009) and Bossaert et al. (2013) simultaneously. Thus, the current study provides a first basis for the current situation in Germany and paves the way for further studies in the context mentioned. In addition, this paper is intended to help closing the research gap in this context of social participation of students with and without a migration background, since, to the best of knowledge, such studies are currently significantly underrepresented or, if available at all, only rudimentary for individual subdimensions. Therefore, the following research question and hypotheses are examined in the present study.

What are the differences in social participation at the beginning and end of a school year between students with and without a migration background?

As the discussion of the theory shows, studies to date in the field of migration backgrounds indicate that findings may differ by gender (Strohmeier et al., 2006; Von Marées and Petermann, 2010; Huber et al., 2018; Zander et al., 2019). Gender has therefore been included as a control variable in the analyses here.

I. After one school year, students with a migration background have fewer reciprocal friendships than peers without a migration background.

II. After one school year, students with a migration background have fewer stable friendships (identical by name) than peers without a migration background.

III. After one school year, students with a migration background have a lower friendship quality than peers without a migration background.

IV. After one school year, students with a migration background have fewer interactions than peers without a migration background.

V. After one school year, the social acceptance of students with a migration background does not differ from the social acceptance of peers without a migration background.

VI. After one school year, students with a migration background do not differ in their self-perception of social participation from peers without a migration background.

Materials and Methods

Design and Implementation

The data used were collected as part of the longitudinal study ‘Social Inclusion of Students in Inclusive Classes’ (SISI). As part of the study, all schools of common learning in North Rhine-Westphalia were contacted. The sample consisted of schools that voluntarily agreed to participate in the survey. The first measurement point was from September 2018 (the start of the school year). The second measurement point was June/July 2019 (the end of the school year). A paper-and-pencil questionnaire was used to collect the data. The survey was conducted by qualified project staff following a standardized protocol. A total of 971 students in year 4 from North Rhine-Westphalia (Germany) participated in the survey. The participants in the sample come from both urban and rural areas of North Rhine-Westphalia. This federal state is home to the largest number of people with a migration background in Germany. Furthermore, the migration rate here is also among the highest in Germany (Destatis Statistisches Bundesamt, 2020b). According to the Federal Statistical Office (Destatis Statistisches Bundesamt, 2018), Turkish (17%) is the most commonly spoken language in households with a migration background. Russian (16%), Polish (9%), and Arabic (7%) are the next most commonly spoken languages in the households addressed.

Ethics

Participation in the study was voluntary for both the schools and the individual participants. Prior to the start of the survey, the parents or legal guardians of the students had to give their written consent to the participation and the processing of the data. Students without a declaration of consent were not allowed to participate in the survey. The procedure was strictly applied; in the case of a revocation, the corresponding data was immediately and irrevocably deleted. All participants in the survey (students, parents, etc.) had the opportunity to ask questions or withdraw their consent at any time during the implementation of the project. The ethics committee of the University of Wuppertal approved the present study. The ethical guidelines of the University of Wuppertal were strictly applied. No objections were raised on the part of the German Research Foundation (DFG; Funding number: 393078153) in the context of study ethics.

Migration Background

In German-speaking countries, various characteristics have been used for some time to determine the construct of migration background in addition to nationality (Kemper, 2010). It is also clear that the same characteristics are not always used or combined for official statistics and for educational research. The exclusive use of the characteristic of nationality, on the other hand, is described as a distorted picture (Kemper, 2010). Therefore, the researcher chose not to use place of birth as operationalization due to several aspects: firstly, stigmatization through the use of a person’s place of birth (e.g., due to one parent born abroad and an associated “inherited citizenship,” as Will, 2019 discusses) should be countered. Secondly, it is to be presumed that the first language learned probably comes from the parent who is/was the child’s primary reference person. Thus, in this context, it can also be assumed that this person was/is an important reference person in the context of the child’s socialization. And thirdly, this approach was used because the aspects of social participation addressed are based on interacting and thus communicative actions. The use of an operationalization of a migration background based on linguistic aspects was therefore favored (see e.g., Davoli and Entorf, 2018; Kast and Schwab, 2020). Thus, the classification criterion for migration background was the first language learned by the students. Students whose first language is a non-German language are therefore defined in this study as having a migration background.

Sample

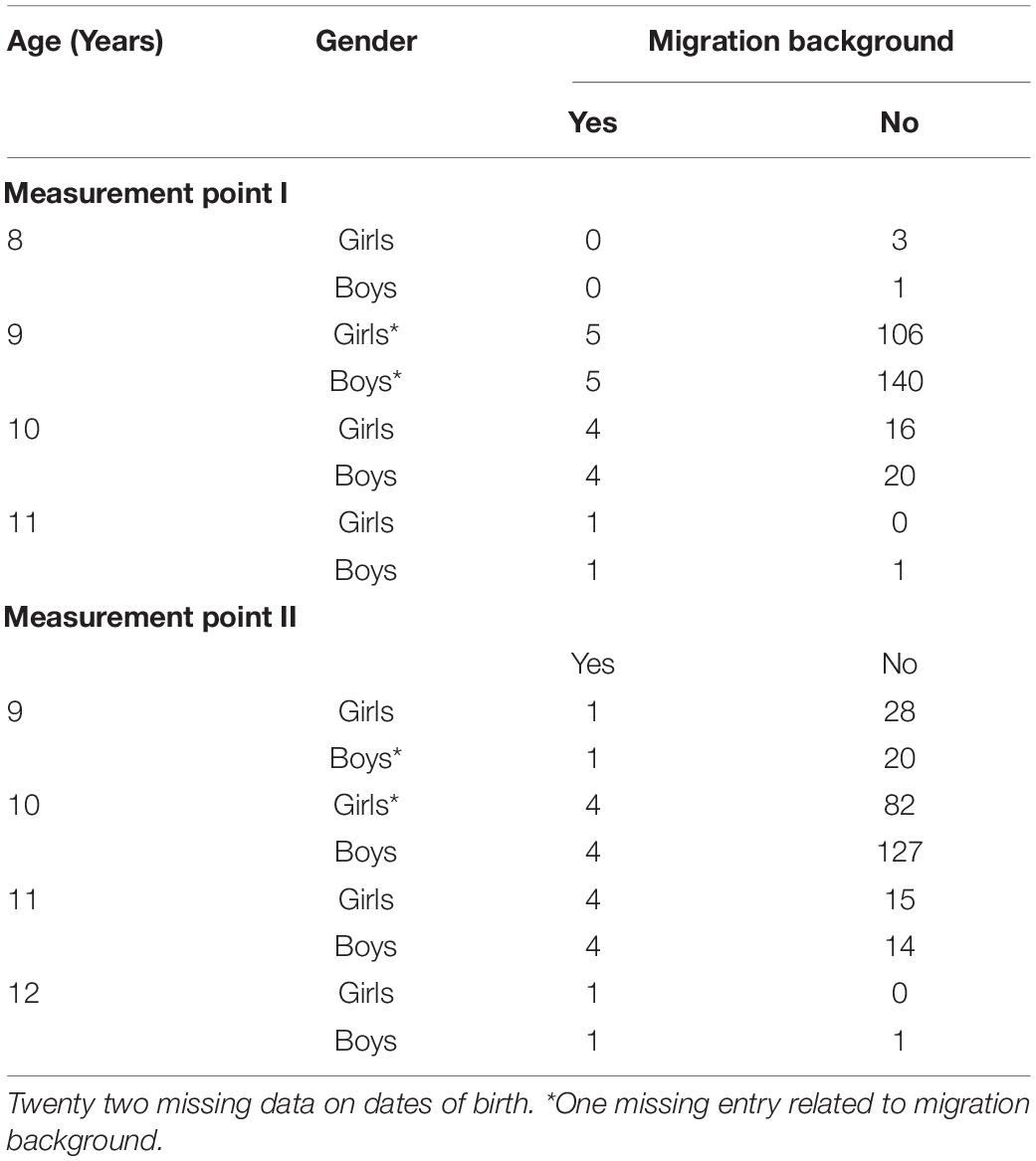

For this study, only students who participated in the survey at both measurement points were considered. Therefore, data of 65 students had to be excluded from further analysis due to lack of attendance at one of the two measurement points or missing data (e.g., because of student illness). In addition, the original sample was reduced due to the rejection of schools for further participation (due to the time and effort required). On average, slightly more than 15 students participated per class in the study. Thus, this average is slightly below the general average class size of 21 students (Destatis Statistisches Bundesamt, 2022). Finally, data could be obtained from 353 students (from 23 classes) who participated at both survey points and could therefore be used for the analysis (Information on students who did not have a declaration of consent from their parents or legal guardians at the time of the survey cannot be provided here due to strict data protection guidelines within the scope of the study and the country in which the survey was conducted.). Of those students, 45% were girls and 16% (52% girls) had a non-German language background. Insufficient information meant that it was not possible to determine the language background status of 3% students (67% girls). At the first measurement point (September 2018), students had an average age of 9 years (SD = 0.42; range 8–11 years). At the second measurement point (June/July 2019), students had an average age of 10 years (SD = 0.57; range 9–12 years). Information on gender or migration background did not change due to the approach of the study (only students who participated at both measurement points were taken into account). A detailed overview of the distribution of age, gender, and language background can be found in Table 1.

Tools

Reciprocal Friendships

Sociometric nomination (e.g., Avramidis et al., 2017) was used to determine reciprocal friendships within a class. In identifying reciprocal friendships, only those that were subject to mutual nomination by two students were scored in this area. A unilateral nomination (by one student) was not scored in this section. For this, the students were asked to nominate their five best friends in the class (“Nominate your 5 best friends in class”). In accordance with data protection requirements, nomination data for persons outside the class or students for whom consent had not been given were disregarded. The same applied to nomination data that exceeded the maximum of five people. Only positive nominations were analyzed from an ethnic angle. The maximum number of friends could therefore vary between zero and five.

Friendship Quality

The quality of the best friendship was measured using a German version of a three-item scale (on aspects of the quality of friendship): intimacy (“I share private thoughts and feelings with this person”) and support (“I depend on this person for help, advice and support” and “This person sticks up for me”) by Bossaert et al. (2015; see also Malcolm et al., 2006; Waldrip et al., 2008). Here, students were explicitly asked to think of their best friend when answering this scale (“Now please think of your very best friend in your class”). Responses could be given using a five-point Likert scale (1 = “not correct at all” to 5 = “completely correct”). Thus, this approach is also oriented (alongside the approaches of Koster et al., 2009; Bossaert et al., 2013) to current research (e.g., Hoffmann et al., 2021).

Friendship Stability

Friendship nominations were used to examine the stability of Students’ friendships. However, this analysis only considered identical friendship nominations (by name; not the amount, but the exact same persons) on the first and second data collection date by one student.

Interactions

The mean of Students’ sociometric evaluations was used to determine their social interactions. Students were given a class list (similar to Roberts and Smith, 1999) with all participating peers in their class (“How often do you spend your break with the following classmate?”) and asked to state how often they spent time with each person at break (1 = “never” to 5 = “every time”). The means calculated for interactions can therefore be between one and five.

Peer Acceptance

The friendship nominations were also used to determine Students’ social acceptance value within a class. This was done using Moreno’s (1974, see also Dollase, 1976; Petillon, 1978):

Thus, the approach is oriented to national (e.g., Huber, 2011) and international (e.g., Schwab, 2015) studies.

Self-Perception of Social Inclusion

Self-perception of social inclusion was measured using the Finnish school health questionnaire, which is based on the international Health Behavior in School-aged Children (HBSC) study (Kämppi et al., 2012). The subscale contains the items “I like being in school,” “Most students in my class are friendly and helpful,” “The students in my class feel comfortable with each other,” and “Other students accept me as I am.” The students responded to the individual items using a five-point Likert scale (1 = “I completely disagree” to 5 = “I completely agree”).

Statistical Analyses

Social Participation

An ANOVA (analysis of variance) with measurement repetition was conducted to investigate differences between the social participation (friendships, interactions, peer acceptance, and self-perception) of students with and without a migration background at different points in time. Time was selected as the within-subject factor in the calculations, with the within-subject variables “first measurement point” (T1) and “second measurement point” (T2). Language background and gender were used as between-subjects factors. An equivalent method to that used for social participation was used to calculate the quality of the best friendship over time.

Friendship Stability

First, the number of identical student friendship nominations (by name) was established for the two survey dates. An ANOVA (analysis of variance) was then conducted to investigate the differences in friendship stability. The number of identical students (by name) was the dependent variable. A language background/gender were independent variables.

Results

Friendships

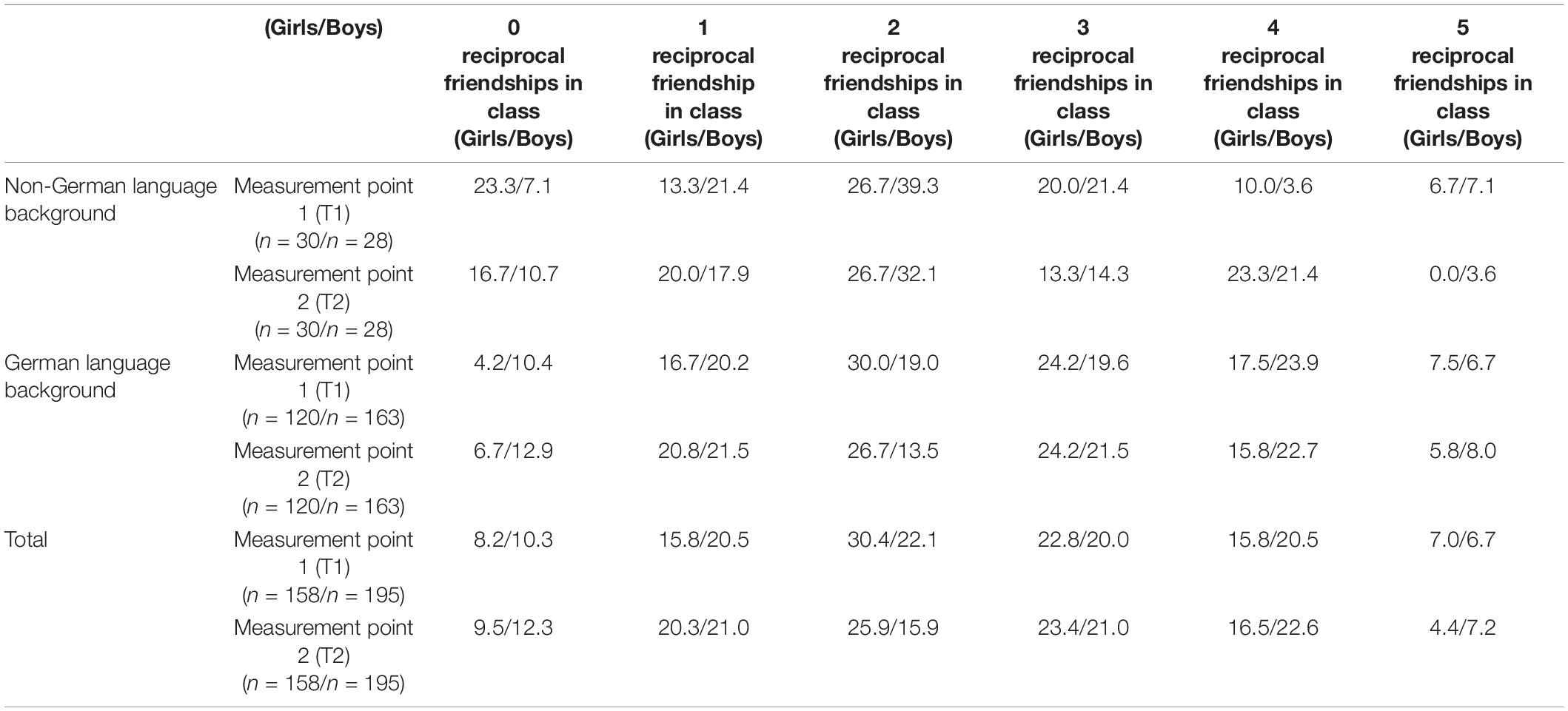

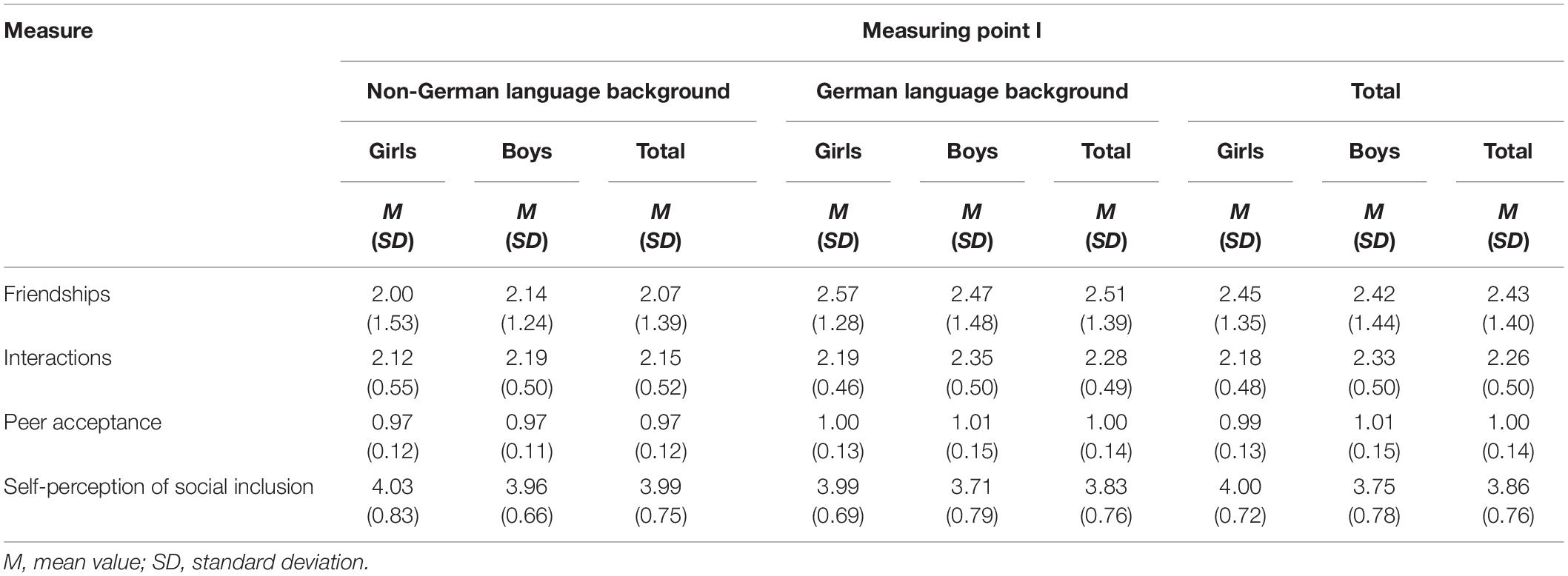

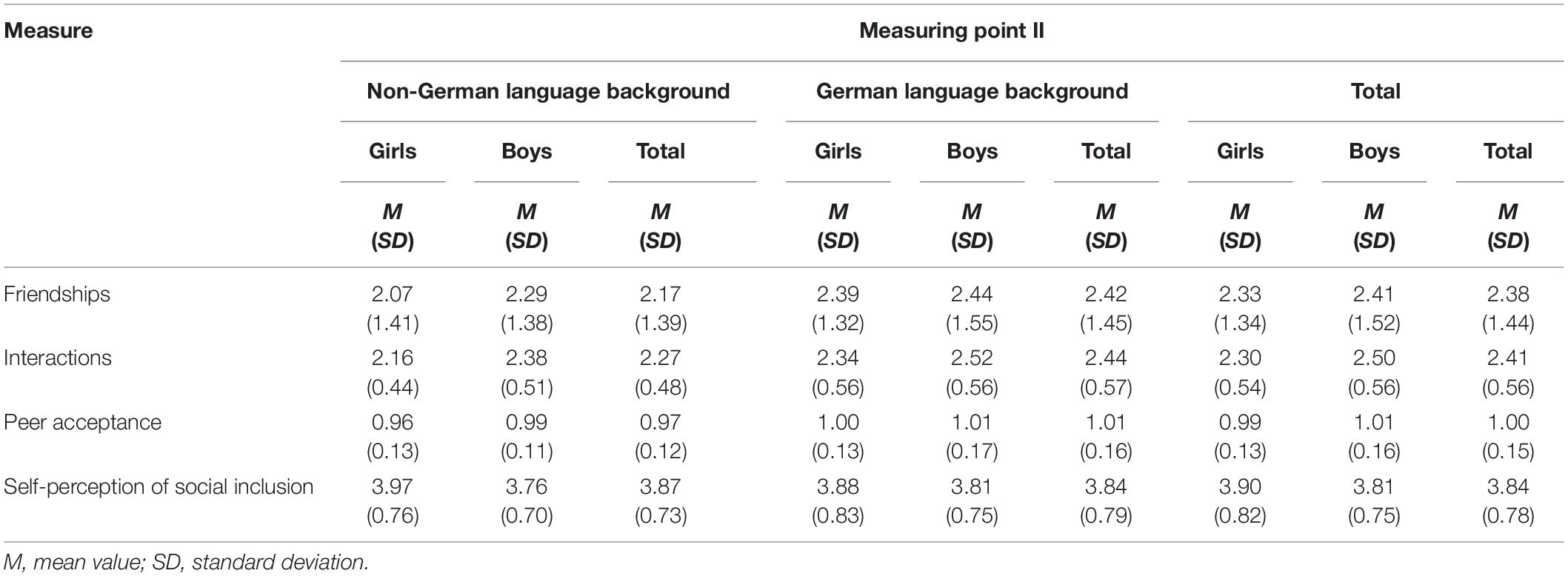

No clear trend for the number of reciprocal friendships over time can be identified in the light of the descriptive analyses (Table 2). The figures fluctuate between the two measurement points both for students with a non-German language background and for those with a German language background. Students had an average of 2.41 (SD = 1.40, range 0–5 reciprocal friends) reciprocal friends at the first time of measurement, while they had an average of 2.37 (SD = 1.44, range 0–5 reciprocal friends) reciprocal friends at the second time of measurement. Differentiated by language background, students with a German language background have an average of 2.51 (SD = 1.39, range 0–5 reciprocal friends) reciprocal friends at the first time of measurement and an average of 2.42 (SD = 1.45, range 0–5 reciprocal friends) reciprocal friends at the second time of measurement. Students with non-German language background have an average of 2.07 (SD = 1.39, range 0–5 reciprocal friends) reciprocal friends at the first time of measurement and an average of 2.17 (SD = 1.39, range 0–5 reciprocal friends) reciprocal friends at the second time of measurement.

Table 2. Distribution of percentage of friendships by gender and migration background at the first (T1) and second (T2) measurement point.

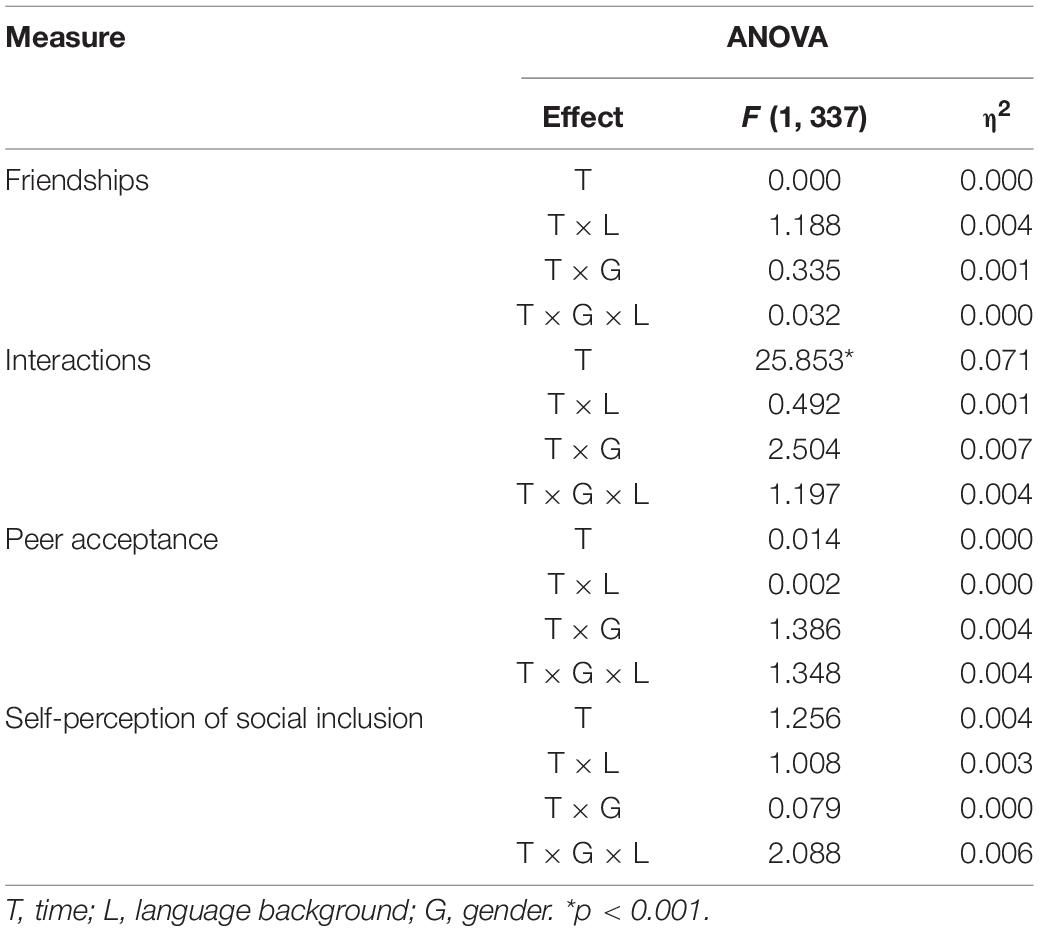

This is also confirmed by the variance analysis. No significant differences were found for Students’ reciprocal friendships for the groups studied. Time thus has no significant impact on the number of Students’ reciprocal friendships. A closer examination of interaction effects (time, gender, and migration background) did not find any significant differences either.

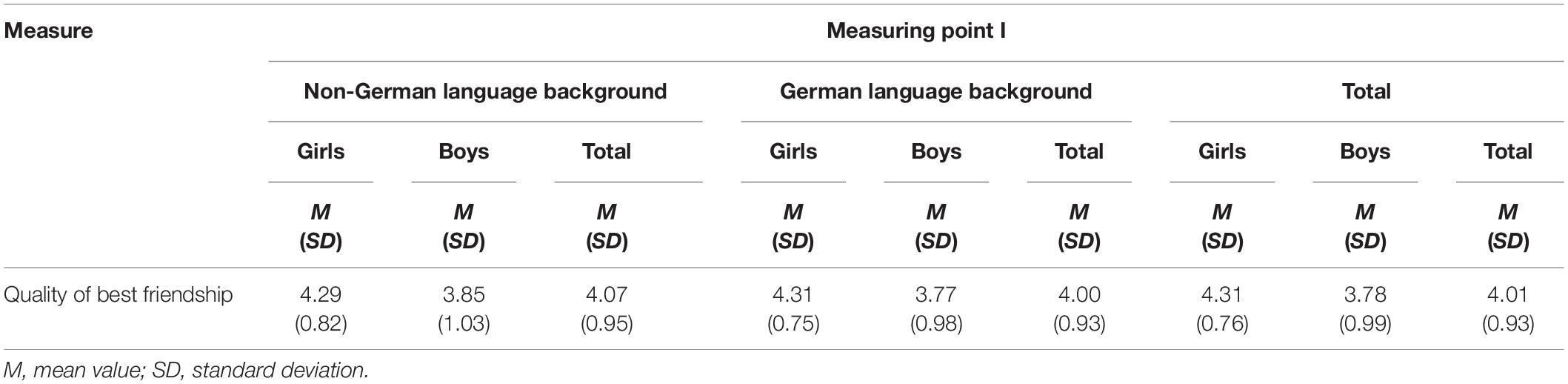

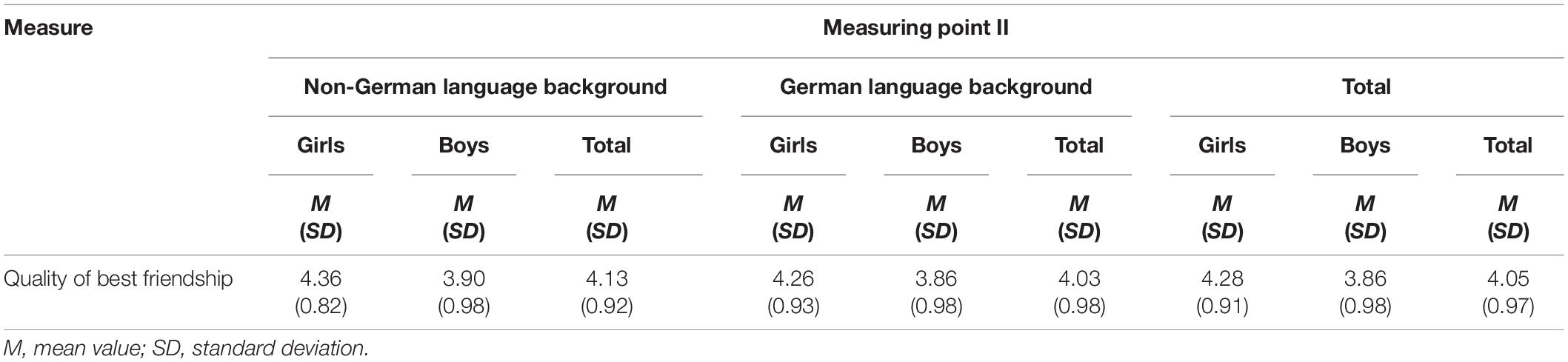

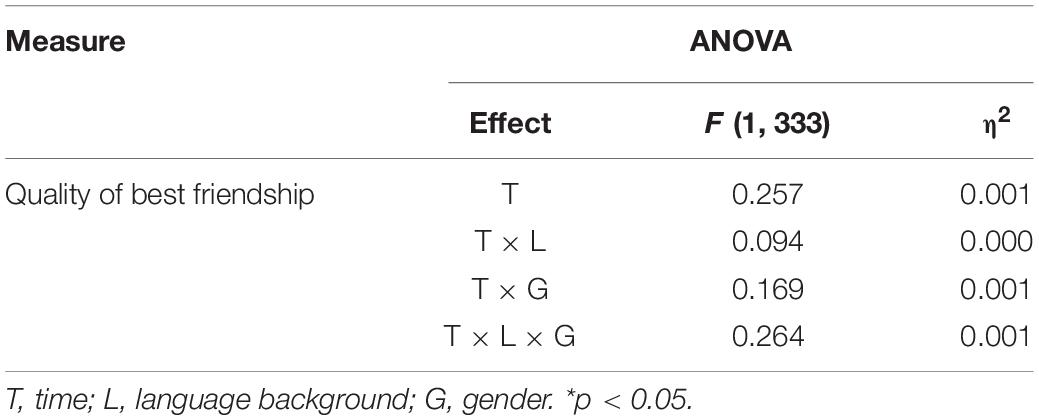

Friendship Quality Over Time

The analysis of the quality of friendship found no significant differences between the Students’ responses at the start of the school year and those at the end of the school year. Interaction effects (time, gender, and migration background) were similarly not affected by time. No significant differences could be found here either (Tables 3–5).

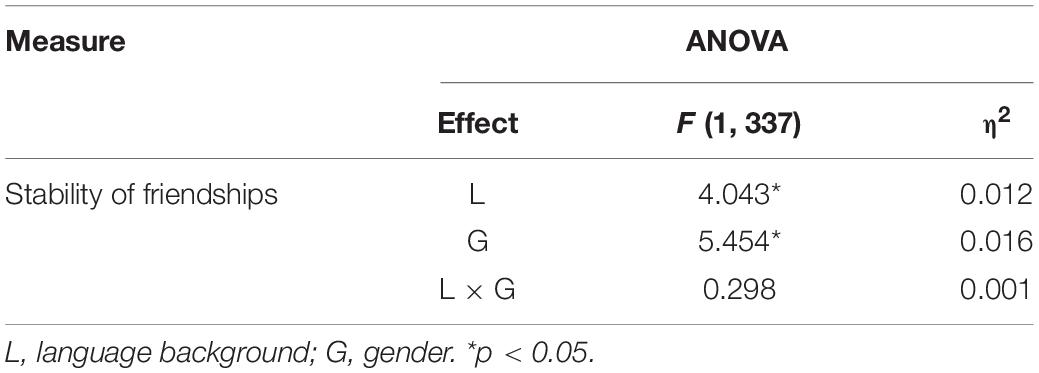

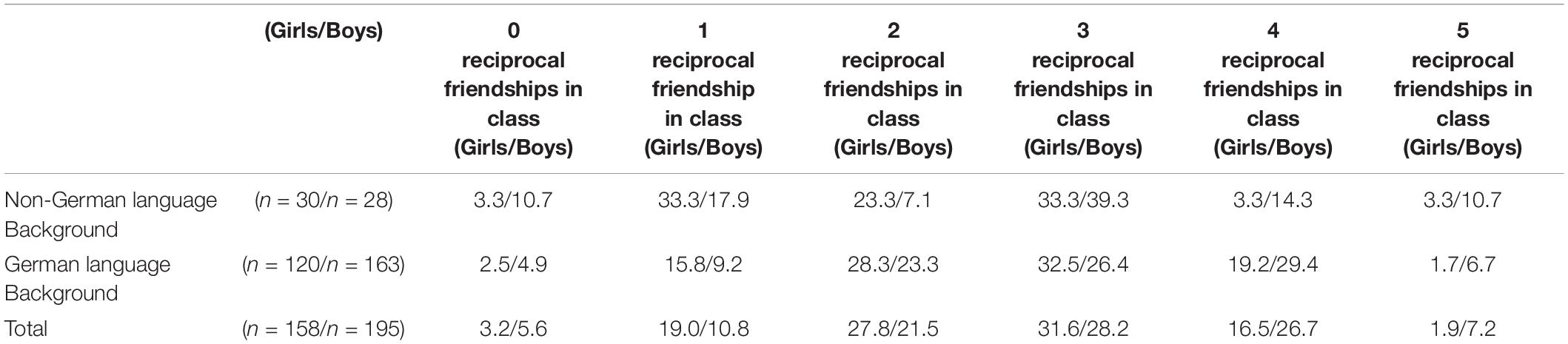

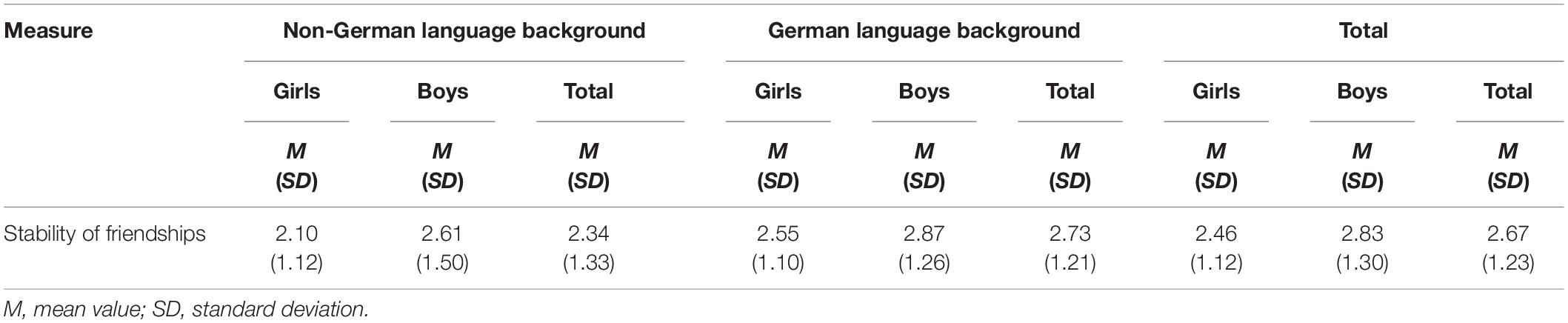

Friendship Stability

The descriptive analyses of the percentage distribution of stable friendships (Table 6) show that students with a non-German language background tend to be at a disadvantage compared to peers with a German language background. For example, a closer examination shows that boys with a non-German language background (10.7%) are more than twice as likely as boys with a German language background (4.9%) to have no stable friendships. At the same time, girls with German language background (19.2%) are almost six times as likely to have four stable friendships than girls with a non-German language background (3.3%). These trends are also confirmed in the variance analyses (Tables 7, 8). The analyses of friendship stability found a significant difference between students with and without a non-German language background [F(1) = 4.04; p = 0.045; η2 = 0.012] and between girls and boys [F(1) = 5.45; p = 0.020; η2 = 0.016]. On average, students with a non-German language background specified fewer stable friendships (M = 2.34, SD = 1.33) than peers with a German language background (M = 2.73, SD = 1.21). Similarly, girls specified fewer stable friendships (M = 2.46, SD = 1.12) than boys (M = 2.83, SD = 1.30). No significant interaction effects (gender and non-German language background) were found.

Table 6. Distribution of the percentage of stable friendships between the first (T1) and the second (T2) measurement point for students with and without a migration background.

Table 7. Mean values and standard deviations of friendship stability between measurement points I and II.

Interactions

Significant differences were found for students’ interactions at break in the student groups studied [F(1, 337) = 25.85, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.071]. Students spent significantly more time together during break at the end of the school year (M = 2.41, SD = 0.56) than at the beginning of the school year (M = 2.26, SD = 0.50). Time thus has a significant impact on student interactions during break. A closer analysis of interaction effects (time, gender, and non-German language background) found no further significant differences.

Peer Acceptance

No significant differences in peer acceptance were found for the time period in question. Similarly, there were no significant differences in interaction effects.

Self-Perception of Social Inclusion

No significant differences were found in self-perception of social inclusion, nor were there any significant interaction effects (time, gender, and non-German language background) (Tables 9–11).

Table 9. Mean values and standard deviations of the dimensions of social participation at measurement point I.

Table 10. Mean values and standard deviations of the dimensions of social participation at measurement point II.

Discussion

The aim of this study was a longitudinally oriented investigation of the social participation (friendships, interactions, social acceptance, and self-perception of social participation) of students with and without a migration background. A non-German language background was used here as an operationalization of a migration background and will be used in the following to discuss implications for students with a migration background in more detail. The analysis used data from students at the start and at the end of a school year. This study found that student responses on the aspects of friendships or friendship quality, social acceptance, and self-perception remained comparable/constant between the two measurement points. However, students reported more interactions at the end of the school year. On friendship stability (identical nomination by name at both measurement points), students with a migration background and girls were found to have fewer stable friendships than students with no migration background and boys, respectively. In light of the findings presented here and the current literature cited, an exploration of (a) an indirect risk [from the continuation of general poorer (initial) conditions (Madsen et al., 2016b; Jänsch and Pupeter, 2017; Krawinkel et al., 2018; Krull et al., 2018) for students with a migration background] and (b) a direct risk (lower friendship stability for students with a migration background at the end of the school year) of disadvantage for students with a migration background in the context of social participation is required.

The findings presented here on friendships are in contrast to the hypothesis I. There is no significant difference in the data at the beginning and end of the school year between students with a migration background and peers with no migration background. This is in contrast to the findings of Schneider et al. (2007). However, the findings presented here could be explained in reference to contact theory according to Allport (1954), which is also discussed by Jugert et al. (2011). In their study, which references contact theory (Allport, 1954), the authors report different findings, namely that the preference for people from the same ethnic background fell over time. Unlike the sample in the Jugert et al. (2011) study (year 5—first year in an ethnically heterogeneous school), most of the students in the study presented here (year 4) had already known each other for at least 3 years. In accordance with Allport’s contact theory (1954), longer contact with each other could therefore already have broken down prejudices and the associated preferences for same-ethnic friendships. The end conditions in the study by Jugert et al. (2011) could therefore correspond to the initial conditions in this study, which could explain the absence of change in friendships. It is therefore to be assumed that (as a result of prolonged intergroup contact) the status of a migration background is not important for the choice of friendships and that other factors such as shared interests, views and activity preferences (McGlothlin and Killen, 2005) are considered. It is also to be assumed that the number of native friends of students with a migration background increases the longer they have been in the country of immigration (Gabrielli et al., 2013) and that any differences thus decrease over time.

The study presented here confirms the initial hypothesis II on the stability of friendships (identical nominations of friends by name). It found that students with a migration background have a significant but marginally lower friendship stability than students with no migration background. Thus, although a significance can be determined, it amounts to less than one friend on average. Furthermore, only a small effect size can be reported here. Therefore, students with a migration background appear to be slightly disadvantaged here. Nevertheless, this could be problematic particularly because lasting friendships with a certain person can lead to deeper attachment (to that person) and thus to an exchange on more personal subjects (thoughts and feelings).

Although, as already outlined, this study did not find (in contrast to hypothesis III) a reduction in friendship quality defined in this way, the findings merely show that there were no processes of change within friendship quality (at the two measurement points). In other words, this could mean that there was no change at the end of the school year from the (poor) initial conditions (lower friendship quality) at the start of the school year and that, for example, students with a migration background remain disadvantaged.

As regards changes in interactions, the initial hypothesis IV similarly does not correspond to the findings. The general increase (moderate effect size) in interactions (irrespective of migration background or gender) could once again be explained by contact theory according to Allport (1954). At this point, it is also important to question the extent to which environmental factors (such as teaching strategies or school wide programming) have either promoted or constrained interaction among peers across the school year. This information should be included in the data collection process in subsequent studies. It is likely that all children got to know each other (better) over the course of the school year, which may have led to an increase in interactions within the breaks (regardless of migration background). In this context, Martinovic (2010) reports that forming one contact is an important predictor of future contacts, and this could also have influenced the increase in interactions over time. In addition, it should be borne in mind that a migration background was classified on the basis of the first language learned, so no conclusions can be drawn about Students’ language level at the time of data collection. Therefore, it is to be assumed that the students with a migration background did not differ significantly in their language proficiency from those with no migration background and that comparable interaction (no language barrier) between peers was possible.

On peer acceptance, the findings of the study are in line with the initial hypothesis V. No clear differences could be found here between students with and without a migration background, which is in line with the current literature. Although Krull et al. (2018) report stability in rejections, they also state that peer acceptance can be affected by change processes. Schäfer and Albrecht (2004) and Von Marées and Petermann (2010) also underline that there is no difference in bullying (a sub-aspect of social acceptance) between students with and without a migration background (when parental education background is considered) and that victims and perpetrators are seldom identical at different measurement points.

The findings presented here on self-perception of social inclusion also correspond to the hypothesis VI. Students with a migration background (representatives of a minority group) and those without thus behave in accordance with the findings on students with and without SEN (the former also being representatives of a minority group) in Schwab et al. (2015): the authors also found no differences in self-perception of social inclusion over time. However, it should be noted here that there is a need for further research that examines these findings in more detail, as students with and without a migration background and with and without SEN cannot and should not be directly compared to or equated with each other despite the fact that those with a migration background and with SEN both belong to a minority group.

Lastly, the problem of inconsistent operationalization of a migration background in many countries (as well as in Germany), which has already been addressed in the theory, needs to be discussed. In Germany, for example, one relatively static criterion is often used to operationalize a migration background (as is also the case in this paper). However, when interpreting the issues addressed within the framework of the four dimensions of social participation, it should be taken into account that the operationalization used on the basis of linguistic aspects is a well-founded and logically derived approach, but at the same time many facets of a migration background remain unconsidered. Especially the degree of acculturation of the participants can only be reflected to a limited extent by this monoperspective view. For example, it is unclear whether and, if so, how strongly the students in the study identify with the present (German) culture, or whether and, if so, how strongly the students identified with a migration background differ from their peers without a migration background in terms of their cultural understanding. The currently available data basis therefore only allows for a more in-depth interpretation of the available findings to a limited extent. Further studies should consider a more differentiated approach, including the consideration of multi-layered levels of a migration background (see e.g., Kemper, 2010). In addition to linguistic aspects (e.g., language first learned, language spoken at home), origin (e.g., place of birth/country of birth) and cultural aspects (acculturation) should also be included.

Nevertheless, based on the current data, there seems to be no difference in most aspects of social participation for students at the two measurement points, or that the initial conditions seem to remain constant or deteriorate (friendship stability for students with a migration background), which can also be seen in relation to the effect sizes. An effect is not identifiable here for the most dimensions. However, if one takes into account the fact that students with a migration background seem to start off with a lower social participation (e.g., Madsen et al., 2016a; Krull et al., 2018; Zander et al., 2019; Hamel et al., 2022), findings suggest the need for intervention. A given level of student social participation, once established, seems not to change or only to undergo limited change over time. Rather, the results of the study seem to indicate that initial conditions may remain.

It is therefore necessary to shed more light on this issue with the help of further research, in order to be able to combat this phenomenon in practice, if necessary, and to take measures to reduce disadvantage in the context of social participation. Further research should therefore focus more on investigating the social participation of students with and without a migration background, in order to be able to assess the current situation more precisely and in a more evidence-oriented way using more advanced methodological approaches and analyses, as well as more comprehensive designs (e.g., mixed methods approaches). Only in this way intervention programs can be developed to improve relationships between students and to generate good class cohesion (e.g., language of the country of immigration; Titzmann, 2014; reducing stereotypes/prejudices toward the out-group; Allport, 1954).

Limitations

The aim of this paper was to provide a first insight into the stability of social participation of students with a migration background—an area of research that has been significantly underrepresented so far. Thus, although the methodological approach used was deliberate in order to gain a first insight into the potentially differing dimensions of social participation (of students with a migration background), this also results in limitations with regard to capturing the complexity of social participation as well as the generalizability of the present results. It would be interesting for future studies to record data in more detail and to determine migration background based on various different classifications (e.g., first language learned/place of birth; Kemper, 2010). Thus, language as an operationalization option reflects only one facet of adequately capturing a migration background. Following Kemper (2010), however, it would be worth considering developing and implementing a minimum catalog that specifies minimum requirements in the context of defining and operationalizing a migration background. In these minimum requirements mentioned by Kemper (2010), aspects such as the generation of a migration background (Plenty and Jonsson, 2017) could also be taken into account. This is the only way to create adequate national and international comparability of data (e.g., with regard to educational planning). In this context studies should also take account of the language proficiency (to uncover any language barriers) of the students (at the time of data collection) for a more precise examination of social participation (Beißert et al., 2020).

In addition, the dimensions surveyed (e.g., friendship, quality of friendship) should be measured in a more complex way. Although some studies in German-speaking countries (Strohmeier et al., 2006) report that the tendency toward homophily (preference for students with identical characteristics, e.g., ethnic background, gender) does not seem to be as strong in the cultural context as in Anglo-American countries, the influence of this effect should nevertheless be further investigated in future studies (Titzmann, 2014; see also Leszczensky and Pink, 2015). In this context, it should also be noted that the study is based on data from Germany and should be considered primarily in this context (e.g., the refugee crisis; e.g., Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge, 2020). Since migration populations, histories, surrounding circumstances, and political contexts and situations differ from country to country, as well as from continent to continent, further studies should examine the extent to which the findings presented here can be transferred to other countries and/or continents. It is therefore advisable to consider the results only in the European context and to bear in mind when interpreting them that the results here can provide a first insight into the current situation. In further research, based on the findings of this paper, more elaborate and complex analyses should be used to more accurately capture the complexity of friendships, interactions, etc. between students in the context of social participation. More comprehensive research designs, such as mixed-methods approaches (e.g., using questionnaires and interviews), should also be included in the considerations. In this context, the use of other instruments that measure social participation with one scale (see e.g., Koster et al., 2008) could also be considered in order to conduct further research (e.g., also with regard to further factor analyses). In addition, here should also be considered whether the quality of friendship should be assessed using a more differentiated view in order to be able to provide a more heterogeneous picture of the quality of friendship. Likewise, the counterbalance technique was not considered when conducting the study. Within the survey, those peers in class should be nominated with whom a student is best friends, spends the most time, and who therefore most likely come to the Student’s mind first (without being influenced by varying information in the sense of the counterbalance technique). Nevertheless, it is unclear whether bias could have resulted exactly from this.

Beyond that, the study was only able to consider social participation in a school context (data protection requirements). More extensive studies in future should also look at activities outside school (leisure activities; see Strohmeier et al., 2006) and compare offline and online friendships (social media; see Glüer and Lohaus, 2016). In addition, it must be taken into account that the maximum number of friends that could be nominated in the study was limited to five. Therefore, it is possible that not all friendships could be considered.

The extent to which academic performance influenced students in their nomination of interaction partners is also still to be determined. Garrote (2020) showed that academic performance has an influence on the selection of interaction partners for collaboration in an academic context (not, however, in a play context). The author also reports a tendency to prefer high-achieving peers (over lower-achieving ones) in a collaborative context. In turn, Stark et al. (2017) report that ethnic minority students are less likely to choose friends with high grades. Nevertheless, ethnic minority students are found to prefer friends with similar academic performance (see also Kretschmer et al., 2018, here focusing on gender). Although the students in the study presented here were asked about their interactions at break time, it is not clear whether the responses were colored by the academic performance of their peers as break-time interactions do still take place in the academic context of school. On this point, Schwab et al. (2021) report in their mixed-method study that children state academic performance as grounds for friendships. In turn, it is also unclear what impact friendship quality can have on other aspects such as academic performance (Sebanc et al., 2016).

Conclusion

The analyses have given some first longitudinally oriented insights into the social participation of students of differing linguistic backgrounds in Germany, thus making a first contribution to closing the existing research gap on the social participation of students with and without a migration background. The study provides indications that students report comparable situations at the different measurement points at the start and end of the school year for the social participation aspects of friendships/friendship quality, (interactions), social acceptance and self-perception of social inclusion. It can therefore be suggested that the initial situation for students with and those without a migration background does not appear to change. Rather, the results of the paper suggest that initial conditions seem to remain constant. Considering that students with a migration background seem to be disadvantaged in the context of social participation (as outlined in the current literature, e.g., Madsen et al., 2016b; Jänsch and Pupeter, 2017; Krawinkel et al., 2018; Krull et al., 2018), the results of the present paper give first indications that these disadvantages in the context of social participation manifest themselves early on and also do not seem to change but remain constant. The findings presented here also indicate that students with a migration background have fewer stable friendships than their peers. The need for further and more in-depth (longitudinal) research in the context of social participation of students with a migration background and interventions that may need to be developed or implemented (e.g., Ülger et al., 2018; Strohmeier et al., 2020) becomes clear when considering that loneliness can be seen as a strong predictor of student intentions to leave school early (Frostad et al., 2015) and that social exclusion appears to be linked to average grades (Raabe, 2019). In terms of practical implications, this means above all that in the school context, attention should be paid at an early stage (preferably in the school entry phase) to a good social participation of all students regardless of their migration background (but of course also with regard to any other dimension of heterogeneity, such as gender, SEN, etc.). In addition to the reduction or avoidance of stereotypes/prejudices (e.g., Allport, 1954) or the consideration of the proportion of children with a migration background within a school and the associated contact opportunities between the students (Titzmann, 2014), the focus should also be on the consideration of linguistic aspects in order to create a good and profitable communication basis between the students, from which friendships and interactions can arise. Thus, language is seen as one of the most significant and important instruments of interethnic exchange (Titzmann, 2014). In addition to these aspects, the acculturation of the students should be the main focus. Here, the focus within the classes should primarily be on developing a positive orientation (attitude) toward the counterpart (both from the perspective of students with and without an immigrant background), as according to the theory of planned behavior (see e.g., Fishbein and Ajzen, 2010) such attitudes predict later behaviors also in the context of friendships (Armitage and Conner, 2001). In this context, it is shown here that immigrants who maintained increased contact with their ethnic culture had more friends from their ethnic group. At the same time, they found fewer native friends (Titzmann et al., 2007, 2012). This paper therefore clearly shows how great the need for further and deeper research is in the context of the social participation of students with (and without) a migration background. This is the only way to achieve full inclusion in practice and to ensure not just physically but also socially inclusive living and learning, enabling equal conditions and opportunities for all students, irrespective of their mental, physical and cultural characteristics (see UNESCO, 1994).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of ethical and data protection reasons. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to NH, aGFtZWxAdW5pLXd1cHBlcnRhbC5kZS4=

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Wuppertal. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

NH did the complete drafting of the manuscript.

Funding

The data of the current study is part of the research project SISI, funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; funding number: 393078153).

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Susanne Schwab as the project initiator and Dr. Stefan Markus, without whose cooperation the data on which this manuscript is based could not have been acquired. In addition, I would like to thank Dr. Sebastian Wahl. Finally, I acknowledge support from the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Wuppertal.

References

Aboud, F., Mendelson, M., and Purdy, K. (2003). Cross-race peer relations and friendship quality. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 27, 165–173.

Armitage, C. J., and Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta- analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 40, 471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939

Avramidis, E., Avgeri, G., and Strogilos, V. (2018). Social participation and friendship quality of students with special educational needs in regular Greek primary schools. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 33, 221–234. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2018.1424779

Avramidis, E., Strogilos, V., Aroni, K., and Kantaraki, C. T. (2017). Using sociometric techniques to assess the social impacts of inclusion: some methodological considerations. Educ. Res. Rev. 20, 68–80. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2016.11.004

Beißert, H., Gönültaş, S., and Mulvey, K. L. (2020). Social inclusion of refugee and native peers among adolescents: it is the language that matters! J. Res. Adolesc. 30, 219–233. doi: 10.1111/jora.12518

Bossaert, G., Colpin, H., Pijl, S. J., and Petry, K. (2013). Truly included? A literature study focusing on the social dimension of inclusion in education. Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 17, 60–79. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2011.580464

Bossaert, G., Colpin, H., Pijl, S. J., and Petry, K. (2015). Quality of reciprocated friendships of students with special educational needs in mainstream seventh grade. Exceptionality 23, 54–72. doi: 10.1080/09362835.2014.986600

Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge (2016). Migrationsbericht 2015 – Zentrale Ergebnisse. Nuremberg: Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge.

Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge (2020). Migrationsbericht 2019. Nuremberg: Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge.

Carbonaro, W., and Workman, J. (2013). Dropping out of high school: effects of close and distant friendships. Soc. Sci. Res. 42, 1254–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.05.003

Carter, E. W., Sisco, L. G., Melekoglu, M. A., and Kurkowski, C. (2007). Peer supports as an alternative to individually assigned paraprofessionals in inclusive high school classrooms. Res. Pract. Persons With Severe Disabil. 32, 213–227. doi: 10.2511/rpsd.32.4.213

Davoli, M., and Entorf, H. (2018). The PISA Shock, Socioeconomic Inequality, and School Reforms in Germany (No. 140) Policy Paper. Bonn: IZA.

Destatis Statistisches Bundesamt (2017). Press release no. 06 of 7 February 2017. Wiesbaden: Destatis Statistisches Bundesamt.

Destatis Statistisches Bundesamt (2018). Pressemitteilung Nr. 329 vom 5. September 2018. Wiesbaden: Destatis Statistisches Bundesamt.

Destatis Statistisches Bundesamt (2020a). Press Release no. 279 of 28 July 2020. Wiesbaden: Destatis Statistisches Bundesamt.

Destatis Statistisches Bundesamt (2020b). Bevölkerung in Privathaushalten Nach Migrationshintergrund und Bundesländern. Wiesbaden: Destatis Statistisches Bundesamt.

Destatis Statistisches Bundesamt (2022). Durchschnittliche Klassengrößen. Wiesbaden: Destatis Statistisches Bundesamt.

Di Saint Pierre, F., Martinovic, B., and De Vroome, T. (2015). Return wishes of refugees in the Netherlands: the role of integration, host national identification and perceived discrimination. J. Ethnic Migr. Stud. 41, 1836–1857. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2015.1023184

Fishbein, M., and Ajzen, I. (2010). Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Frostad, P., Pijl, S. J., and Mjaavatn, P. E. (2015). Losing all interest in school: social participation as a predictor of the intention to leave upper secondary school early. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 59, 110–122. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2014.904420

Gabrielli, G., Paterno, A., and Dalla-Zuanna, G. (2013). Just a matter of time? The ways in which the children of immigrants become similar (or not) to Italians. J. Ethnic Migr. Stud. 39, 1403–1423. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2013.815389

Garrote, A. (2020). Academic achievement and social interactions: a longitudinal analysis of peer selection processes in inclusive elementary classrooms. Front. Educ. 5:4. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00004

Glüer, M., and Lohaus, A. (2016). Participation in social network sites: associations with the quality of offline and online friendships in German preadolescents and adolescents. Cyberpsychology 10, 21–36. doi: 10.5817/CP2016-2-2

Grütter, J., Gasser, L., and Malti, T. (2017). The role of cross-group friendship and emotions inadolescents’ attitudes towards inclusion. Res. Dev. Disabil. 62, 137–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2017.01.004

Hamel, N., Schwab, S., and Wahl, S. (2022). Social participation of German students with and without a migration background. J. Child Fam. Stud. 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10826-022-02262-9

Hoffmann, L., Wilbert, J., Lehofer, M., and Schwab, S. (2021). Are we good friends?– Friendship preferences and the quantity and quality of mutual friendships. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 36, 502–516. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2020.1769980

Huber, C. (2011). ,,Lehrerfeedback und soziale Integration. Wie soziale Referenzierungsprozesse die soziale Integration in der Schule beeinflussen könnten. [Teacher’s feedback and social integration: is there a link between social referencing theory and social integration in school].”. Empirische Sonderpädagogik 3, 20–36.

Huber, C., Gerullis, A., Gebhardt, M., and Schwab, S. (2018). The impact of social referencing on social acceptance of children with disabilities and migrant background: an experimental study in primary school settings. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 33, 269–285. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2018.1424778

Hunkler, C., Kneip, T., Sand, G., and Schuth, M. (2015). “Growing old abroad: social and material deprivation among first-and second generation migrants in Europe,” in Ageing in Europe—Supporting Policies for an Inclusive Society, eds A. Bösch-Supan, T. Kneip, H. Litwin, M. Myck, and G. Weber (Berlin: De Gruyter), 199–208. doi: 10.1515/9783110444414-020

Jänsch, A., and Pupeter, M. (2017). “Friendships among peers,” in Well–Being, Poverty and Justice From a Child’s Perspective, eds S. Andresen, S. Fegter, K. Hurrelmann, and U. Schneekloth (Cham: Springer), 135–147.

Jugert, P., Leszczensky, L., and Pink, S. (2018). The effects of ethnic minority adolescents’ ethnic self-identification on friendship selection. J. Res. Adolesc. 28, 379–395. doi: 10.1111/jora.12337

Jugert, P., Noack, P., and Rutland, A. (2011). Friendship preferences among German and Turkish preadolescents. Child Dev. 82, 812–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01528.x

Kämppi, K., Välimaa, R., Ojala, K., Tynjälä, J., Haapasalo, I., Villberg, J., et al. (2012). Koulukokemusten Kansainvälistä Vertailua 2010 Sekä Muutokset Suomessa ja Pohjoismaissa 1994–2010: WHO-Koululaistutkimus (HBSC-Study). Tampere: Finnish National Agency of Education.

Kast, J., and Schwab, S. (2020). Teachers’ and parents’ attitudes towards inclusion of pupils with a first language other than the language of instruction. Int. J. Incl. Educ. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2020.1837267

Kemper, T. (2010). Migrationshintergrund – eine Frage der Definition! [Migration Background - a Question of Definition!]. Die Deutsche Schule 102, 315–326.

Koster, M., Nakken, H., Pijl, S. J., and van Houten, E. (2009). Being part of the peer group: a literature study focusing on the social dimension of inclusion in education. Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 13, 117–140. doi: 10.1080/13603110701284680

Koster, M., Nakken, H., Pijl, S. J., van Houten, E., and Spelberg, H. C. L. (2008). Assessing social participation of pupils with special needs in inclusive education: the construction of a teacher questionnaire. Educ. Res. Eval. 14, 395–409. doi: 10.1080/13803610802337657

Koster, M., Pijl, S. J., Nakken, H., and Van Houten, E. (2010). Social participation of students with special needs in regular primary education in the Netherlands. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 57, 59–75. doi: 10.1080/10349120903537905

Krawinkel, S., Südkamp, A., Lange, S., Wolf, S. M., and Tröster, H. (2018). Soziale Akzeptanz und Eigengruppenbevorzugung deutschsprachiger und türkischsprachiger Schülerinnen und Schüler [Social acceptance and in-group bias among German speaking and Turkish speaking students]. Psychol. Erzieh. Unterr. 65, 110–124. doi: 10.2378/peu2018.art08d

Kretschmer, D., Leszczensky, L., and Pink, S. (2018). Selection and influence processes in academic achievement—more pronounced for girls? Soc. Netw. 52, 251–260. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2017.09.003

Krull, J., Wilbert, J., and Hennemann, T. (2018). Does social exclusion by classmates lead to behaviour problems and learning difficulties or vice versa? A cross-lagged panel analysis. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 33, 235–253. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2018.1424780

Leszczensky, L., and Pink, S. (2015). Ethnic segregation of friendship networks in school: testing a rational-choice argument of differences in ethnic homophily between classroom-and grade-level networks. Soc. Netw. 42, 18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2015.02.002

Madsen, K. R., Damsgaard, M. T., Rubin, M., Jervelund, S. S., Lasgaard, M., Walsh, S., et al. (2016a). Loneliness and ethnic composition of the school class: a nationally random sample of adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 45, 1350–1365. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0432-3

Madsen, K. R., Damsgaard, M. T., Jervelund, S. S., Christensen, U., Stevens, G. G. W. J. M., Walsh, S., et al. (2016b). Loneliness, immigration background and self-identified ethnicity: a nationally representative study of adolescents in Denmark. J. Ethnic Migr. Stud. 42, 1977–1995. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2015.1137754

Malcolm, K. T., Jensen-Campbell, L. A., Rex-Lear, M., and Waldrip, A. M. (2006). Divided we fall: children’s friendships and peer victimization. J. Soc. Pers. Relationsh. 23, 721–740. doi: 10.1177/0265407506068260

Mamas, C. (2012). Pedagogy, social status and inclusion in Cypriot schools. Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 16, 1223–1239. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2011.557446

Martinovic, B. (2010). Interethnic Contacts: A Dynamic Analysis of Interaction Between Immigrants and Natives in Western Countries. Utrecht: Utrecht University.

McGlothlin, H., and Killen, M. (2005). Children’s perceptions of intergroup and intragroup similarity and the role of social experience. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 26, 680–698. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2005.08.008

Moreno, J. L. (1974). Die Grundlagen der Soziometrie. Wege zu Neuordnung der Gesellschaft. Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Pijl, S. J., Koster, M., Hannink, A., and Stratingh, A. (2011). Friends in the classroom: a comparison between two methods for the assessment of students’ friendship networks. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 14, 475–488. doi: 10.1007/s11218-011-9162-2

Plenty, S., and Jonsson, J. O. (2017). Social Exclusion among Peers: the role of Immigrant Status and Classroom Immigrant Density. J. Youth Adolesc. 46, 1275–1288. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0564-5

Raabe, I. J. (2019). Social exclusion and school achievement: children of immigrants and children of natives in three European countries. Child Indic. Res. 12, 1003–1022. doi: 10.1007/s12187-018-9565-0

Roberts, C. M., and Smith, P. R. (1999). Attitudes and behaviour of children toward peers with disabilities. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 46, 35–50. doi: 10.1080/103491299100713

Schäfer, M., and Albrecht, A. (2004). ‘Wie du mir, so ich dir?‘ Prävalenz und Stabilität von Bullying in Grundschulklassen [‘Tit for tat?‘ - Prevalence and Stability of Bullying in Primary School Classes]. Psychol. Erzieh. Unterr. 51, 136–150.

Schneider, B. H., Dixon, K., and Udvari, S. (2007). Closeness and competition in the inter-ethnic and co-ethnic friendships of early adolescents in Toronto and Montreal. J. Early Adolesc. 27, 115–138. doi: 10.1177/0272431606294822

Schwab, S. (2015). Social dimensions of inclusion in education of 4th and 7th grade pupils in inclusive and regular classes: outcomes from Austria. Res. Dev. Disabil. 43, 72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2015.06.005

Schwab, S., Gebhardt, M., Krammer, M., and Gasteiger-Klicpera, B. (2015). Linking self-rated social inclusion to social behaviour. An empirical study of students with and without special education needs in secondary schools. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 30, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2014.933550

Schwab, S., Lindner, K. T., Helm, C., Hamel, N., and Markus, S. (2021). Social participation in the context of inclusive education: primary school students’ friendship networks from students’ and teachers’ perspectives. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 1–16. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2021.1961194

Sebanc, A. M., Guimond, A. B., and Lutgen, J. (2016). Transactional relationships between Latinos’ friendship quality and academic achievement during the transition to middle school. J. Early Adolesc. 36, 108–138. doi: 10.1177/0272431614556347

Stark, T. H., Leszczensky, L., and Pink, S. (2017). Are there differences in ethnic majority and minority adolescents’ friendships preferences and social influence with regard to their academic achievement? Zeitsch. Erzieh. 20, 475–498. doi: 10.1007/s11618-017-0766-y

Strohmeier, D., and Doğan, A. (2012). Emotional problems and victimization among youth with national and international migration experiences living in Austria and Turkey. Emot. Behav. Diffic. 17, 287–304.

Strohmeier, D., Nestler, D., and Spiel, C. (2006). Freundschaftsmuster, Freundschaftsqualität und aggressives Verhalten von Immigrantenkindern in der Grundschule. Diskurs Kindheits Jugendforschung 1, 21–37.

Strohmeier, D., Stefanek, E., Yanagida, T., and Solomontos-Kountouri, O. (2020). “Fostering cross-cultural friendships with the ViSC Anti-Bullying-Programme,” in Contextualizing Immigrant and Refugee Resilience: Cultural and Acculturation Perspectives, eds D. Güngör and D. Strohmeier (Cham: Springer), 227–241.

Titzmann, P. F. (2014). Immigrant adolescents’ adaptation to a new context: ethnic friendship homophily and its predictors. Child Dev. Perspect. 8, 107–112. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12072

Titzmann, P. F., Silbereisen, R. K., and Mesch, G. S. (2012). Change in friendship homophily: a German Israeli comparison of adolescent immigrants. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 43, 410–428. doi: 10.1177/0022022111399648

Titzmann, P. F., Silbereisen, R. K., and Schmitt-Rodermund, E. (2007). Friendship homophily among diaspora migrant adolescents in Germany and Israel. Eur. Psychol. 12, 181–195. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040.12.3.181

Ülger, Z., Dette-Hagenmeyer, D. E., Reichle, B., and Gaertner, S. L. (2018). Improving outgroup attitudes in schools: a meta-analytic review. J. Sch. Psychol. 67, 83–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2017.10.002

UNESCO (1994). The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. Adopted by the World Conference on Special Needs Education: Access and Quality, Salamanca, Spain, 7-10 June 1994. Paris: UNESCO.

Vaquera, E., and Kao, G. (2008). Do you like me as much as I like you? Friendship reciprocity and its effects on school outcomes among adolescents. Soc. Sci. Res. 37, 55–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2006.11.002

Von Marées, N., and Petermann, F. (2010). Bullying in German primary schools: gender differences, age trends and influence of parents’ migration and educational backgrounds. Sch. Psychol. Int. 31, 178–198. doi: 10.1177/0143034309352416

Waldrip, A. M., Malcolm, K. T., and Jensen-Campbell, L. A. (2008). With a little help from your friends: the importance of high-quality friendships on early adolescent adjustment. Soc. Dev. 17, 832–852. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00476.x

Will, A.-K. (2019). The German statistical category “migration background”: historical roots, revisions and shortcomings. Ethnicities 19, 535–557. doi: 10.1177/1468796819833437

Wittek, M., Kroneberg, C., and Lämmermann, K. (2020). Who is fighting with whom? How ethnic origin shapes friendship, dislike, and physical violence relations in German secondary schools. Soc. Netw. 60, 34–47. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2019.04.004

Keywords: migration background (German as a second language), friendship, social interactions, peer acceptance, self-perception of social inclusion, longitudinal study

Citation: Hamel N (2022) Social Participation of Students With a Migration Background—A Comparative Analysis of the Beginning and End of a School Year in German Primary Schools. Front. Educ. 7:764514. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.764514

Received: 25 August 2021; Accepted: 31 January 2022;

Published: 28 February 2022.

Edited by:

Christoforos Mamas, University of California, San Diego, United StatesReviewed by:

Alison Black, University of California, San Diego, United StatesCandido J. Ingles, Miguel Hernández University of Elche, Spain

Copyright © 2022 Hamel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Niklas Hamel, aGFtZWxAdW5pLXd1cHBlcnRhbC5kZQ==

Niklas Hamel

Niklas Hamel