- Entrepreneurship Department, BINUS Business School Undergraduate Program, Bina Nusantara University, Jakarta, Indonesia

Student entrepreneurship activities can be a driving force for the emergence of young entrepreneurs. Therefore, universities are making efforts to equip their students with the requisite entrepreneurial knowledge and skills for a conducive university entrepreneurial ecosystem. The present study employs a quantitative approach and survey-type research. The research method uses the explanatory method with research objects, including the internal environment of the institution, external environmental support, student entrepreneurial orientation, student entrepreneurial intentions, and student entrepreneurial activities. Data were collected through online questionnaires, which were randomly distributed to 456 students of 7 state universities and 11 private universities across Java and Sumatra, Indonesia. Descriptive and multivariate data analyses with a structural equation model was carried out using the IBM SPSS Amos 20.0 software. The study has propounded a research novelty called Entrepreneurship Eclectic Education, which combines several techniques, designs, and methods that have been proven valid, reliable, and feasible for adoption in universities. Such novelty is likely to trigger student performance in their entrepreneurial activities in the university's entrepreneurial ecosystem. This is realized through a synergy between the internal and external environment of the institution that can foster an entrepreneurial orientation and then trigger students' entrepreneurial intentions, which leads to the creation of student entrepreneurial activities. This study offers valuable recommendations for higher education decision-makers to re-orient the entrepreneurship curriculum and create a conducive university entrepreneurship ecosystem.

Introduction

The World Economic Forum states that higher education is the fifth pillar of the 12 pillars supporting a country's global competitiveness index through its role as an efficiency enhancer that increases its productivity and long-term prosperity (Schwab, 2018). As one of the factors driving the nation's economic growth, universities must have policies to create a higher education environment that thoughtfully and comprehensively supports entrepreneurial activities. Previous studies confirmed that entrepreneurial activity is positively correlated with economic growth (Galindo-Martín et al., 2019). For this reason, universities need to develop and encourage potential in young entrepreneurs while they are still in college through student entrepreneurial activities. It is believed that the entrepreneurial activities that students undertake during college will encourage them to be future entrepreneurs (Kourilsky and Walstad, 1998). It is also believed that they are more aware of the latest technology, market trends, and latest product ideas, are more friendly and sociable, and have more energy and high enthusiasm to begin and engage in new ventures at their age (Bosma et al., 2020). Entrepreneurial activities carried out by students are confirmed to result from simultaneous interaction between social values and individual attributes (Bosma et al., 2020), where the university environment and support from communities, societies, or organizations are considered social values. Individual attributes include orientation, intention, and motivation of students to become entrepreneurs, to create job opportunities for others and add values to their business (Bosma et al., 2020). In addition, previous research has confirmed that many things can improve the entrepreneurial skills of students, including entrepreneurship education (Odewale et al., 2019), support from external practitioners such as existing entrepreneurs (Bazan et al., 2019), and a university ecosystem that can have a positive influence on student entrepreneurial activities, although not significantly (Bazan et al., 2019).

The trend in Indonesia shows that only 16% of university graduates become entrepreneurs (BPS Indonesia, 2016). As of early 2020, the ratio of Indonesian national entrepreneurs was only 3.47% of the total population, which was still below the entrepreneurial ratio of neighboring countries, such as Malaysia, 4.74%, Thailand, 4.26%, and Singapore, 8.76% (Indonesian Ministry of Cooperatives and MSMEs, 2020). Therefore, the micro condition of these universities has a significant impact on Indonesia's macro needs, especially the ratio of Indonesian national entrepreneurs. Analysis of previous research regarding student entrepreneurial activities linking it to the conditions in Indonesian universities led the authors to formulate the main problem in this study, namely the low ability of universities to produce quality graduates capable of entrepreneurship after completing their studies.

Based on the research focus, this study aimed to obtain the best-fit model that could serve as an empirical basis to answer the research questions. In addition, it was expected that the results of this study could: (a) identify the most dominant indicator that contributes to each research variable, (b) analyze the relationship and the magnitude of influence between each variable, and (c) analyze the role of the mediator variable that is entered into the model. It was imperative to obtain empirical evidence from a higher education ecosystem in developing countries, such as Indonesia, which encourage student entrepreneurial activities.

Literature Review

Social Values Shaping Student Entrepreneurial Activities

Institution Internal Environment, External Environment Support

The internal environment of the institution that interacts with external parties in conducting entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurship research, and the development of the university's entrepreneurship programs can motivate students' intention to become entrepreneurs (Walter et al., 2013). An effective interaction synergizing internal strategies with the surrounding environment is purportedly able to strengthen entrepreneurship, particularly the performance of the entrepreneurs (Lumpkin and Dess, 1996). This interaction is also able to generate strong support for the education system within the institution so that the perception of potential obstacles in entrepreneurial activities is reduced (Mehtap et al., 2017), which in the end can provide learning to improve students' work abilities in the future (Knight and Yorke, 2003).

Disruptive innovations that are changing the organizational structure and current market conditions increasingly require universities to prepare an entrepreneurial ecosystem that can equip students with entrepreneurial competencies and skills to face the current demands (Hulme et al., 2014; Kuratko and Morris, 2018). Effective education and training could improve entrepreneurial skills to spark students' entrepreneurial intentions (Gieure et al., 2019). Entrepreneurship is based on complex learning, so universities need to formulate a comprehensive learning strategy to stimulate students' interests (Knight and Yorke, 2003). Entrepreneurship education is not a topic restricted just to the business but also includes a complex set of attitudes, beliefs, skills, and qualities. It is likely to have a positive impact if other relevant disciplines are linked to the entrepreneurship sub-topic as part of the curriculum. This would provide the program with a scientific context, enhance career relevance (Bridgstock, 2013), and facilitate finding solutions to complex problems (McDonald et al., 2018). Entrepreneurship is also a dynamic study with a history of being related to many variables such as knowledge and experience (Gupta et al., 2016), being very contextual (Thomassen et al., 2019), and comprehensive in nature (Hägg and Kurczewska, 2019). Entrepreneurship's proven ability to improve students' critical thinking skills (Ratten and Usmanij, 2020) has been presented in various forms of learning (Thomassen et al., 2019).

Since it has been proven to positively impact the experience of staff and students (Brown, 2018), universities could accommodate this need to re-orient their entrepreneurship curriculum by facilitating mentorship by practitioners (Baluku et al., 2019; Williams Middleton et al., 2019). Other research findings confirm that facilitating business incubators could teach students the need to recognize, adapt, and appreciate the tensions/dynamics of the business environment (Ollila and Williams-Middleton, 2011). The work-based entrepreneurship learning programs improve the student's business learning experience in all relevant disciplines (Gibson and Tavlaridis, 2018), which, in turn, could increase the student's business setup (Galvão et al., 2020). In addition, other researchers confirm that entrepreneurship education in line with local wisdom is a must. Therefore, entrepreneurship educators should always keep “regional attachments in mind” when developing and implementing entrepreneurship learning programs at their universities (Franco et al., 2010). Viewed from the external environment of the institution, support for providing training services, guidance, and financial support for business startups in an incubator is a significant issue that needs to be resolved urgently (Fong, 2020). Support from outside the institution in the form of investment activities for student entrepreneurial activities is proven to directly relate to the student's entrepreneurship (Zabelina et al., 2019).

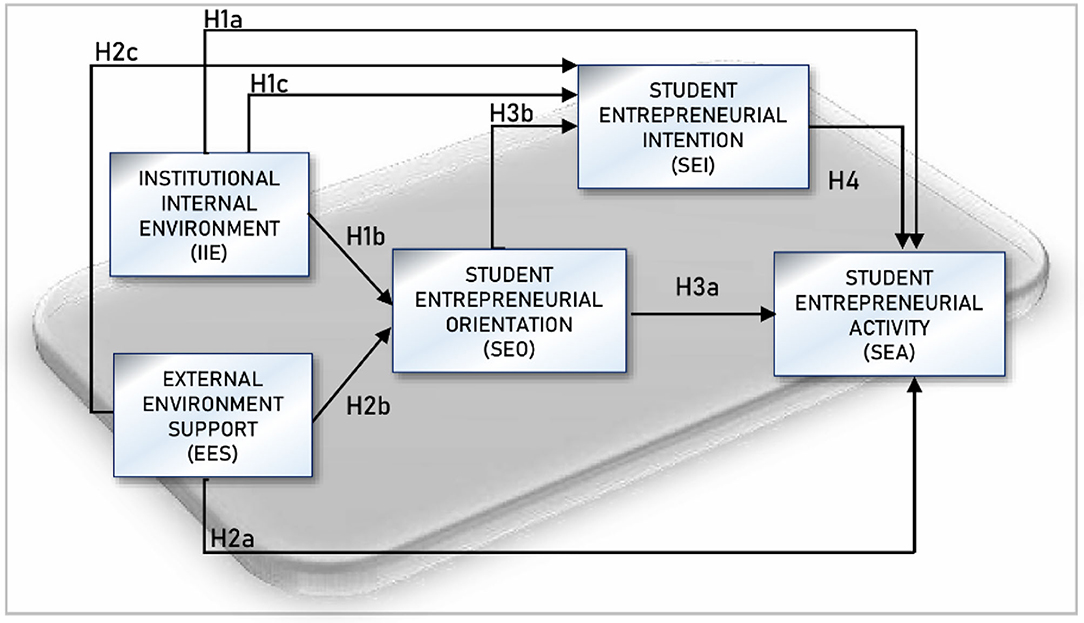

Based on the literature review that was used as a reference in this study, the authors compiled six hypotheses as follows:

Hypothesis 1a: Institutional Internal Environment directly affects Student Entrepreneurial Activity.

Hypothesis 1b: Institutional Internal Environment directly affects Student Entrepreneurial Orientation.

Hypothesis 1c: Institutional Internal Environment directly affects Student Entrepreneurial Intention.

Hypothesis 2a: External Environment Support directly affects Student Entrepreneurial Activity.

Hypothesis 2b: External Environment Support directly affects Student Entrepreneurial Orientation.

Hypothesis 2c: External Environment Support directly affects Student Entrepreneurial Intention.

Individual Attributes Forming Student Entrepreneurship Activities

Student Entrepreneurship Orientation, Student Entrepreneurship Intention

Entrepreneurial performance has increased significantly with the strengthening of the entrepreneurial orientation (Lumpkin and Dess, 2001; Walter et al., 2006; Keh et al., 2007; Li et al., 2009; Bayarçelik and Özşahin, 2014; Emoke-Szidónia, 2015; Gupta et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016; Chavez et al., 2017); however, entrepreneurial orientation cannot directly improve performance. Therefore, we needed a model to capture and illustrate the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and performance (Lumpkin and Dess, 1996; Lyon et al., 2000). Entrepreneurial orientation is one of the essential individual attributes observed in this study to monitor its impact on entrepreneurial performance.

Entrepreneurial intention is an individual attribute that is key to building the foundations of student entrepreneurial activity (SEA), but not every entrepreneurial intention can ultimately be realized intostarting and operating a new business (Shirokova et al., 2016). Many things affect the gap between entrepreneurial intentions and the outcome: a individual factors such as family entrepreneurial background, age, gender, and entrepreneurship education at the previous level of education, and the characteristics of the university environment, among others, where policymakers work in harmony with academicians in designing academic curricula to incorporate relevant theoretical elements with entrepreneurial practice (Iwu et al., 2019). Intentions are important outcomes of learning that are widely adopted across educational contexts. An increase in entrepreneurial intention is a desired outcome of entrepreneurship education (Nabi et al., 2017; Lavelle, 2019) because it is the first step in setting up a business (Sancho et al., 2020). Entrepreneurial intention is also shaped by various personality types and entrepreneurial self-efficacy (Sahin et al., 2019). Studies confirm that the greater the students' intention to become entrepreneurs, the higher their tendency to become nascent entrepreneurs and complete the tasks related to it (Souitaris et al., 2007). Against this background, the authors proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3a. Student Entrepreneurial Orientation directly affects Student Entrepreneurial Activity.

Hypothesis 3b. Student Entrepreneurial Orientation directly affects Student Entrepreneurial Intention.

Hypothesis 4. Student Entrepreneurial Intention directly affects Student Entrepreneurial Activity.

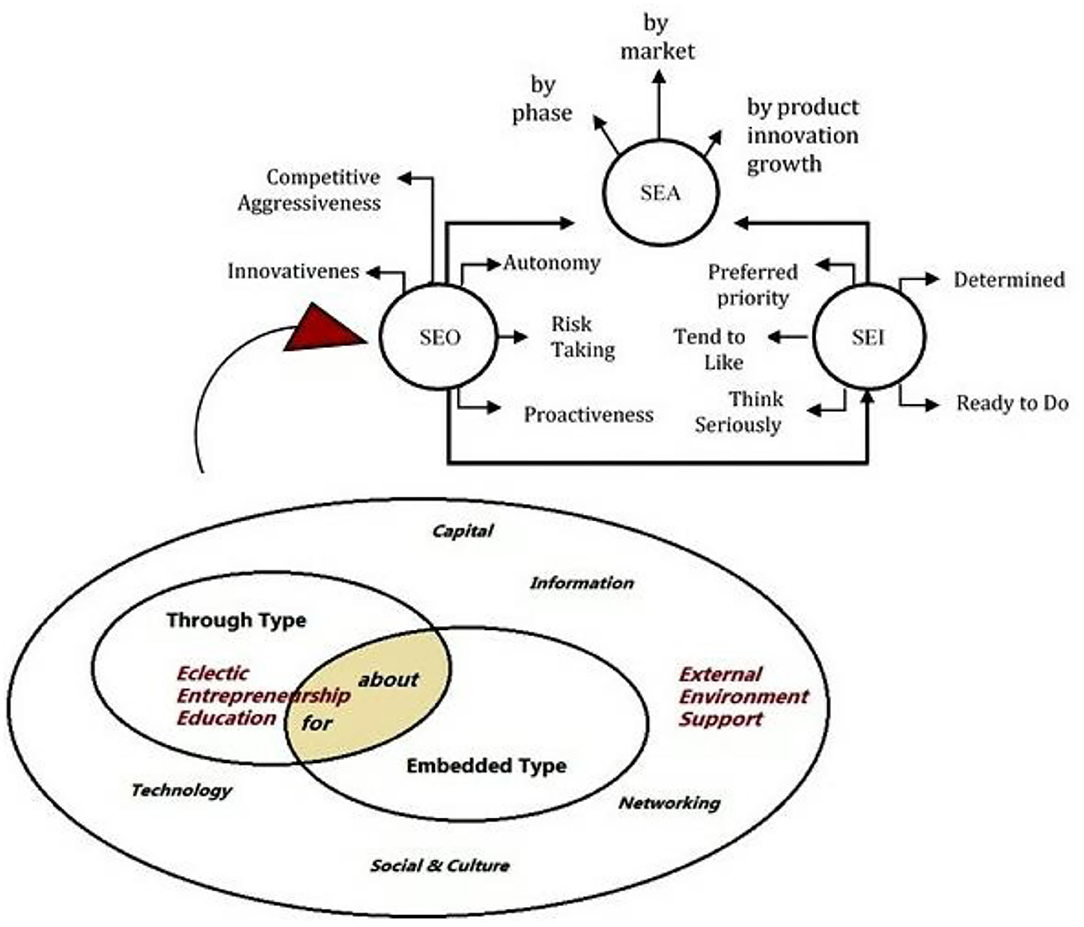

As a result of reviewing previous studies, nine hypotheses were successfully constructed and formulated in the following conceptual model presented in Figure 1.

Materials and Methods

Research Design

This study used a deductive approach with a survey research strategy on five research objects: internal institutional environment, external environment support, student entrepreneurial orientation, student entrepreneurial intention, and student entrepreneurial activity. The research subjects were universities in Indonesia with students as the unit of analysis. Data were collected using a cross-sectional time horizon with a web-based questionnaire as the research instrument. The data analysis technique used quantitative methods through descriptive analysis and explanatory analysis.

Population and Sample

There are 122 public universities in Indonesia spread across five major islands, namely Java, Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and Papua. The distribution of universities in Java and Sumatra is 63%, and the rest is spread over the three other islands (45). There are 3,171 private universities in Indonesia, with the largest distribution (75%) on the islands of Java and Sumatra and the rest spread over the islands of Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and Papua. Based on data published by the Indonesian Ministry of Research, Technology, and Higher Education in 2018, the largest number of public and private universities are located on the islands of Java and Sumatra. This was the determining factor for choosing the public and private universities located in Java and Sumatra for this study.

Seven public universities and 11 private universities in Java and Sumatra were chosen as samples, and the survey was conducted at these universities. The questionnaires were distributed within ±2 months with the help of several fellow lecturers who were permanent lecturers at the 18 sample universities. These colleagues then distributed the online questionnaires through social media accounts connected to several social media groups on campus, including social media groups of lecturers distributing the questionnaires and students on the campus. The online questionnaires were also distributed with the help of several colleagues who were members of lecturer associations, official lecturer forums, and several business incubators managed by lecturers at the sampled universities.

A total of 477 students agreed to participate as respondents in this study by filling out the research questionnaire. After checking for missing data, straight-line responses, and outliers, 456 respondents were deemed to be eligible for this study. The mean age of the respondents was 20 years, with a standard deviation of 1.47 years. A total of 41.2% of the respondents were men, 58.8% were women. Respondents included students enrolled in business study programs (51%) and non-business study programs (49%).

Demographically, of the 456 respondents, 39.9% did not have entrepreneurship education experience before entering college, 42.5% had received prior entrepreneurship education for 1–2 years, 10.5% for 3–4 years, and 7% for 5–6 years. Furthermore, 25.2% of the respondents had no entrepreneurial experience before entering college, 50% had entrepreneurial experience, 21.3% had been entrepreneurs to meet personal needs, and 3.5% had been entrepreneurs to meet family needs.

Variable Operationalization

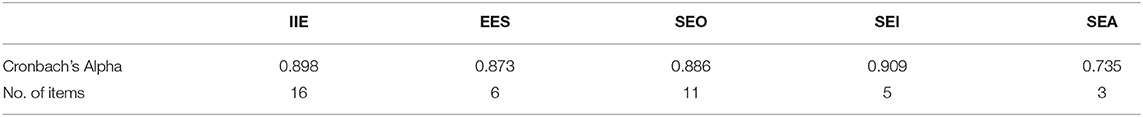

Research Instrument

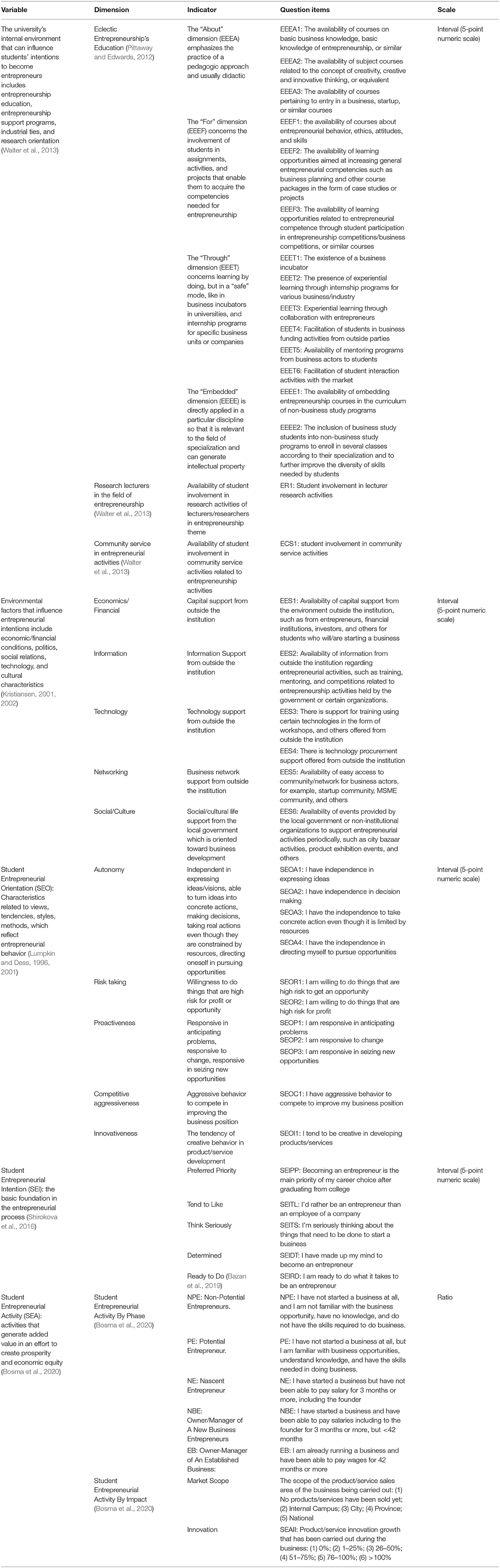

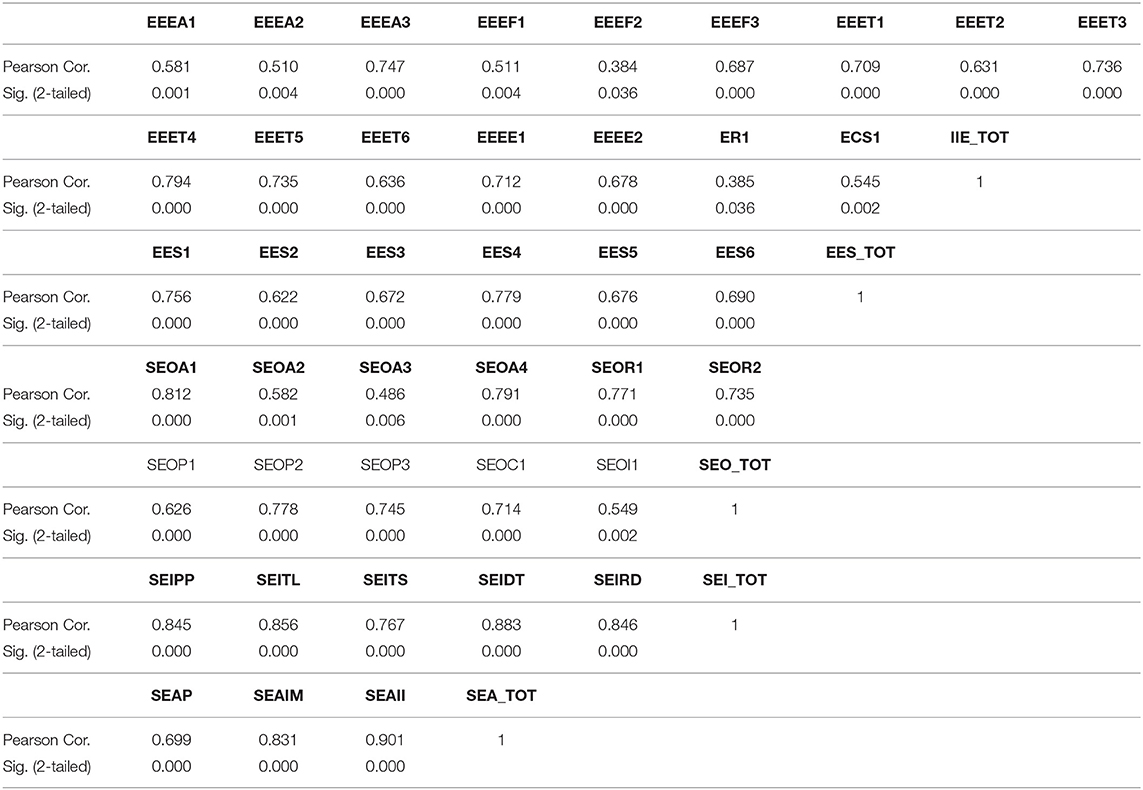

The research instrument used is a web-based questionnaire with question items arranged based on the operationalization of the variables in Table 1. The validity of this research instrument was measured using SPSS 20 by measuring the consistency of the correlation between item scores and the overall score on each research variable. In contrast, the correlation coefficient used was the Pearson correlation coefficient considering that the research data was interval scale and ratio scale. The instrument is “valid” if the significance level measured by the p <0.05 (Hair et al., 2014) and “very valid” if the resulting p-value is much smaller than 0.05 (Hair et al., 2014). Table 2 presents the results of the validity of the research instrument.

It can be seen that the research instrument was valid and mostly very valid because the resulting p-value was much smaller than 0.05 (Hair et al., 2014). Instrument reliability can be measured through three perspectives—stability, equivalence, and consistency (Cooper and Schindler, 2014). The instrument is (1) stable, if repeated measurements are made on the same person with the same instrument and still produces the same answer; (2) equivalent, if the level of variation in answers obtained from several different respondents is relatively low; and (3) Consistent, if the response given by the respondent shows a homogeneous answer. Reliability is determined when the value of the resulting reliability coefficient is >0.7 (Hair et al., 2014). In this study, the reliability coefficient value was measured using the Cronbach's Alpha value on SPSS20. Table 3 shows the results of the reliability test of this research instrument.

Since the Cronbach's Alpha value of all variables was higher than 0.7, the instrument was reliable and could be used as a measuring tool for this research.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

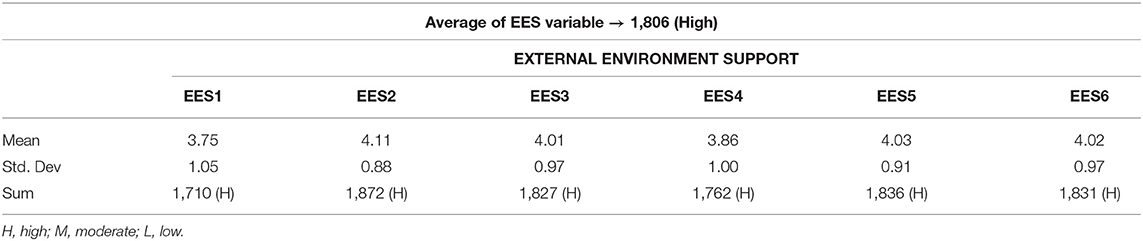

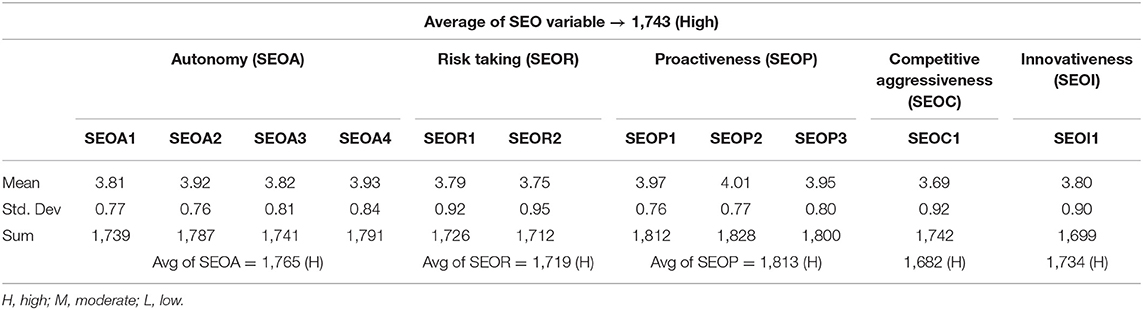

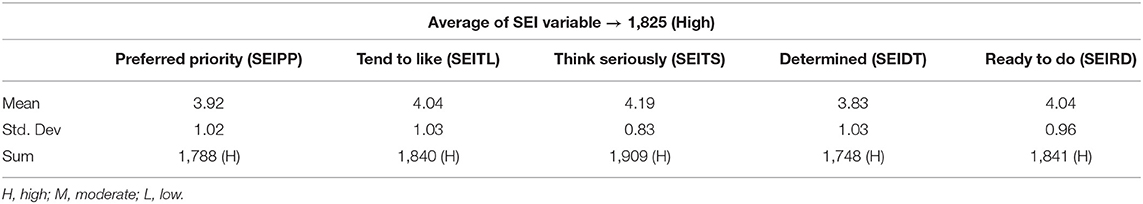

The respondents' replies to each question were distributed between the lowest value of one point and the highest value of five points. Based on their responses, the 456 respondents were grouped into three categories, namely “low” when the total perception score on each question was between 456 and 1,064, “medium” between 1,065 and 1,672, and “high” between 1,673 and 2,280. The results were then averaged for each dimension and each variable. All the results of this descriptive statistical analysis are presented in Tables 4–8.

Measurement of the SEA by phase dimension showed that:

1) 11.6% of the respondents had not started a business at all and had no business knowledge/skills

2) 45.8% had not started a business at all but had business knowledge/skills

3) 32.5% had started a business but had not been able to pay salaries for 3 months or more, including for the founders

4) 8.3% had started a business and were able to pay salaries including the founders for 3 months, but <42 months

5) 1.8% had run a business and had been able to pay wages for 42 months.

Furthermore, reviewing the performance of SEA by impact dimension with indicators of sales area coverage showed that:

1) 47.1% of the respondents stated that there was no product/service sales or active business

2) 12.9% of them stated that there still were sales around the campus

3) 28.9% of them stated that they had reach within the city

4) 4.2% of them stated that they had reach up to the provincial level

5) 6.8% of them stated that they had reach up to the national level.

For the product innovation growth indicator:

1) 40.8% stated that there was no growth in product innovation

2) 26.5% indicated that they experienced product innovation growth of 1–25%

3) 10.6% stated that they had product innovation growth of 26–50%

4) 10.0% stated that they had product innovation growth of 51–75%

5) 12.0% stated that the development of their product innovation was 76–100%.

Demographic data showed that 74% of male students and 76% of female students had entrepreneurial experience before entering college. Their entrepreneurial experience was motivated by various factors, including:

1) just trying (44% for male students, 54% for female students);

2) fulfilling personal needs (25% for male students, 19% for female students);

3) to fulfill family needs (5% for male students, 3% for female students).

We conducted the contingency test on respondents' demographic data between the entrepreneurial experience of students before entering college and the entrepreneurial activities they do while in college. The results showed a significant relationship between the two periods with a contingency coefficient of 37.5% for female students and 40.6% for male students (Astuty et al., 2021). This validates the choice of the research model for this study, which shows that, for the formation of a student's entrepreneurial activities, the student needs an entrepreneurship education that is more than just knowledge-based. It also strengthens the results of the contingency test, which proved that the student's entrepreneurial activities while in college were not related to their knowledge-based entrepreneurship education when they attended high school (Astuty et al., 2021).

Bivariate testing of demographic data in this study proves that the emergence of students' entrepreneurial intentions is not related to the study program taken by students. Even non-business study programs can trigger the emergence of students' intentions to become entrepreneurs, even though these non-business study programs do not directly present an entrepreneurial learning curriculum as much as business study programs (Astuty and Yustian, 2021).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Measurement Model Analysis

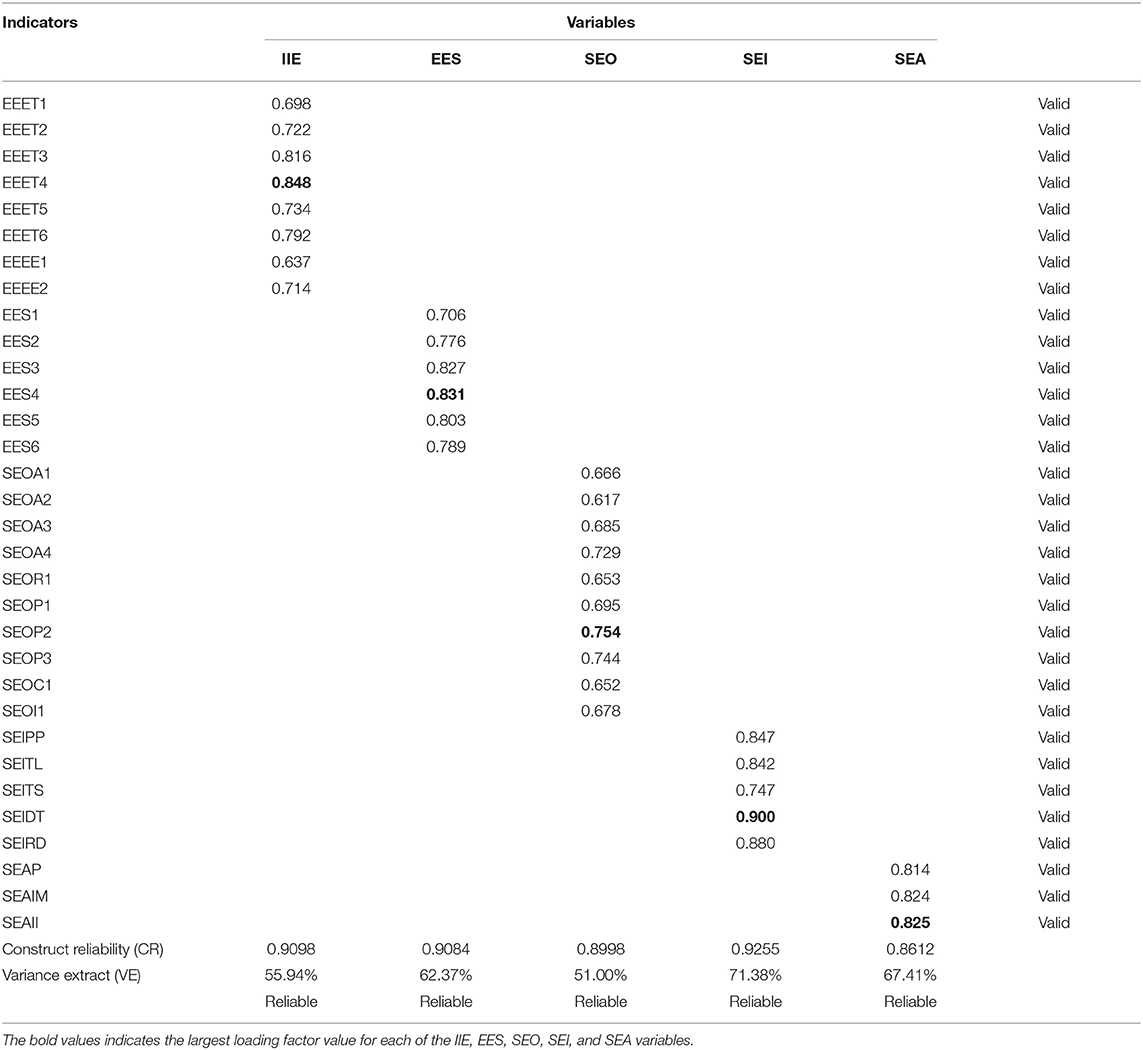

The results from the measurement model show that the main characteristics of each variable observed in this study were validity, reliability, and having a good model fit. The results of calculations using the related AMOS software are presented in Table 9.

Table 9. Loading factor, construct reliability, and variance extract of IIE, EES, SEO, SEI, and SEA.

Not all proposed indicators in the conceptual model were valid, and only the indicators in Table 9 have a loading factor value of >0.5, so they were declared valid (Hair et al., Hair et al., 2014). The high loading factor indicated that the latent constructs converge on a common point (have good convergent validity). Variance Extract (VE) of the IIE variable is 55.94%, which means that all indicators representing the IIE construct have a convergence rate of 55.94%. This implies that the data variance described in the IIE variable can be considered a communality (Hair et al., 2014). This also applies to the VE values of other constructs in the model, including VE of EES = 62.37%, VE of SEO = 50.00%, VE of SEI = 71.38%, and VE of SEA = 67.41%.

Good reliability means that all indicators can consistently represent the measured latent variables. Good reliability is achieved if the Construct Reliability (CR) value is higher than 0.7 (Hair et al., 2014). As seen in Table 9, all the CR values in the five latent variables were >0.7, so it can be confirmed that the IIE, EES, SEO, SEI, and SEA variables have high internal consistency. All the values of CR are >0.7 and VE >0.5; therefore, all existing variables are declared reliable (Hair et al., 2014).

Based on the confirmatory factor analysis, it can be firmly established that:

(1) The institutions that facilitate business funding activities from outside parties for its students are the most dominant internal variable and an indicator of the social values of a university's entrepreneurial ecosystem.

(2) The offer of technology procurement support from outside is the main characteristic of the external support variable.

(3) Student behavior that is proactive toward change is the most dominant indicator reflecting student entrepreneurial orientation.

(4) Determination to become an entrepreneur is the main characteristic of entrepreneurial intentions.

(5) The growth of product/service innovation is the most dominant indicator that reflects the impact of student entrepreneurial activities at universities in Indonesia.

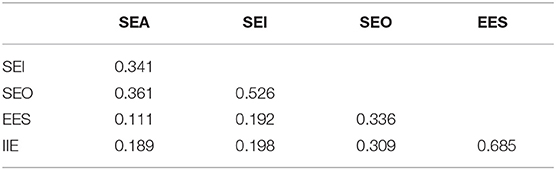

The relationship magnitude between the latent variables is shown in the correlation matrix in Table 10.

The highest correlation occurs in the interaction between the internal environment of the institution and external parties in the form of support for entrepreneurial learning. A value of 0.685 indicates a moderate to strong relationship (Hair et al., 2014). This result is in line with the findings that formal learning in institutions and informal learning obtained through external support, such as training support, mentoring, and network access support, which strengthens education and entrepreneurial competence through knowledge and access to the entrepreneurial resources available outside the institution (Williams Middleton et al., 2019).

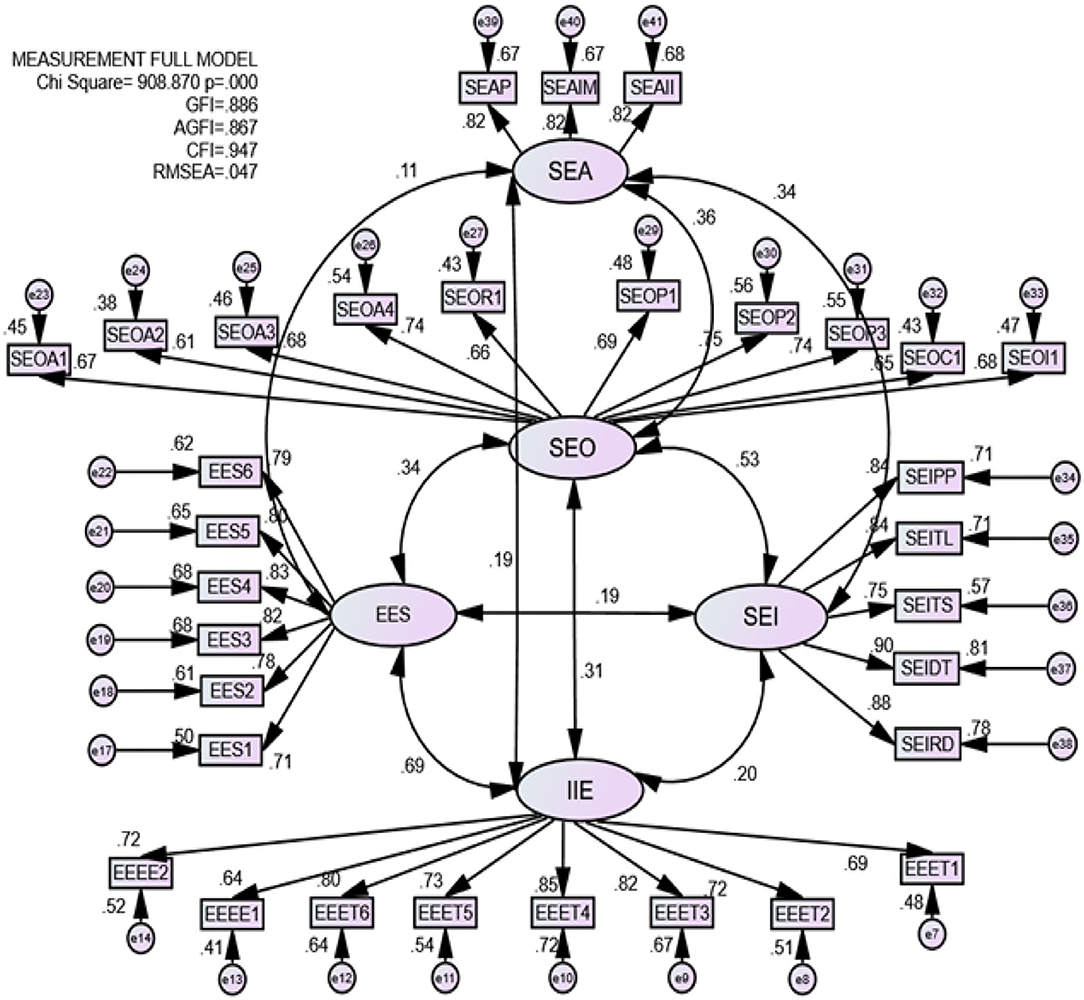

Figure 2 below shows the complete measurement model analysis where the valid and reliable indicators of the CFA results have been constructed.

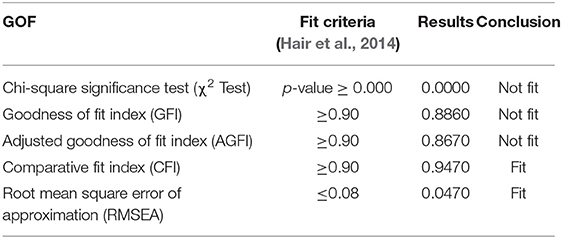

According to the estimation results of Goodness of Fit (GOF) test results at the Table 11, there are two GOF measures met the fit criteria in the goodness of fit (Hair et al., 2014).

Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is one of the most widely used GOF measurements to correct the χ2 significance test that rejects models with a large sample or a large number of observed variables so that the RMSEA better represents how well the model fits the population, not just the sample used for estimation. A low RMSEA value indicates a good model fit. Previous studies used a limit of <0.05 as a good RMSEA value, while some others used <0.08 as a good RMSEA limit. Recent research does not recommend a certain limit in expressing the RMSEA value (Hair et al., 2014). Whether the limit is <0.05 or <0.08, the results of this study, with an RMSEA value of 0.047, fulfill both limits. This also confirms that the RMSEA value in this study can correct the value of the χ2 significance test to meet the model fit criteria.

The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) is an incremental progression toward the model fit criteria. The range of CFI values is between 0 and 1. A higher value indicates a better fit, so a CFI value >0.90 is usually associated with a model fit (50). In this study, the CFI value was 0.9470, thus meeting the model fit criteria. Considering that the two goodness of fit measures (RMSEA and CFI) met the model fit criteria, it can be stated that the model built based on the empirical evidence meets the criteria of the best-fit model. The model can estimate the population covariance matrix, which tends not to differ from the sample data covariance matrix.

Structural Model Analysis

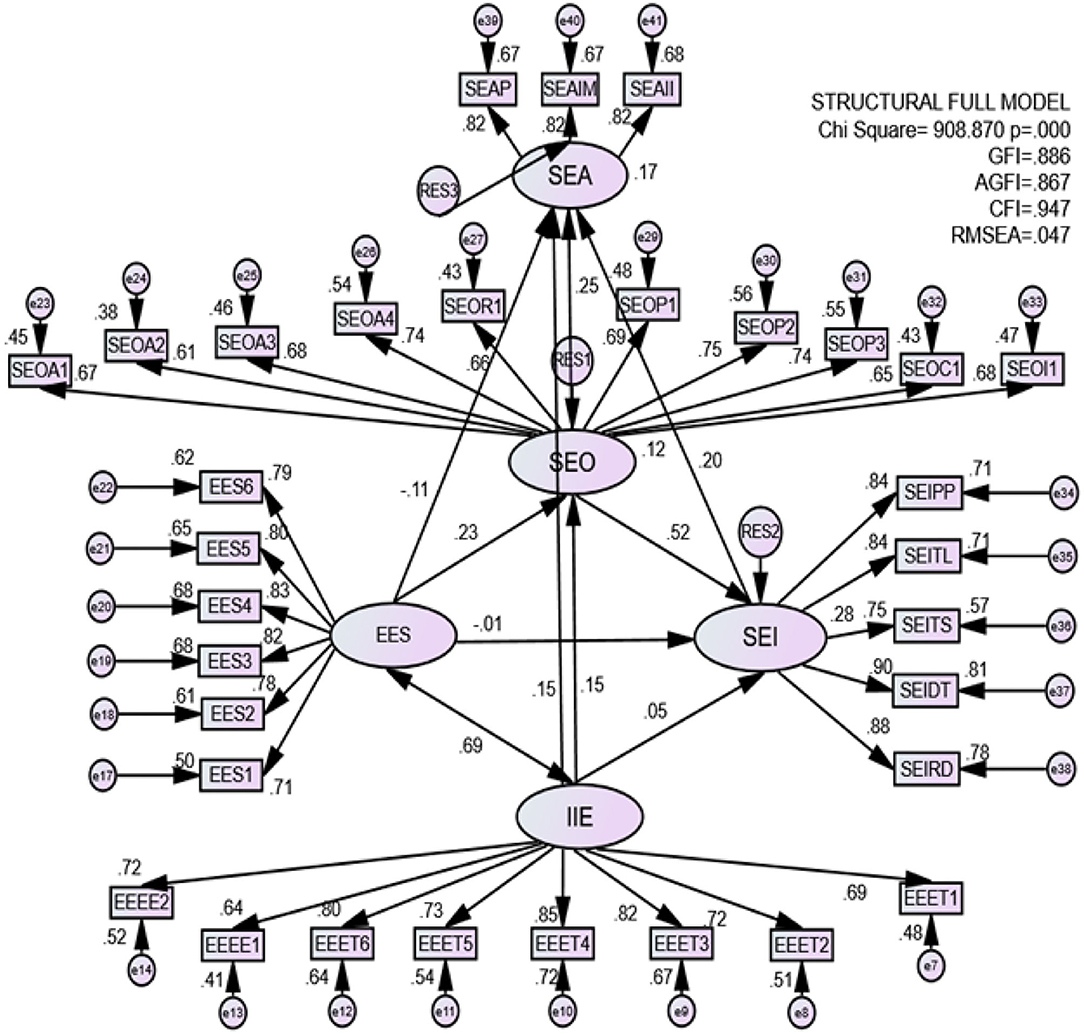

Nine hypotheses proposed in the conceptual model were tested through a structural model using the AMOS20 software, as shown in Figure 3.

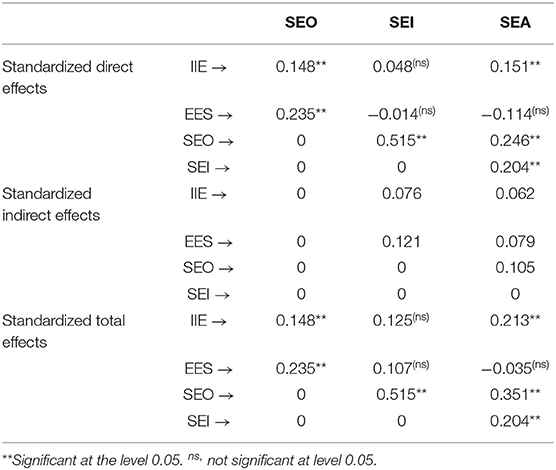

The statistical parameters of the structural model test results in Figure 3 are presented in the summary of estimation results for the structural model parameter in Table 12.

The significance test results for each estimated path coefficient in Table 12 show that the nine hypotheses proposed were not wholly accepted. Three hypotheses, namely H1c, H2c, and H2a, were rejected.

Based on the structural model summary of the estimation in Table 12, this research model consists of three main substructures.

Substructure 1:

SEO = 0.15*IIE + 0.24*EES.

(p = 0.041; IIE → SEO) and (p = 0.002; EES → SEO).

This means that the IIE and EES can significantly increase the SEO by 15 and 24%, respectively (H1b and H2b accepted), with the strength in explaining the variation of sample data to predict the population being classified as weak (R2 = 12%; Chin, 1998). This finding aligns with the previous finding and supports the statement that various factors are conducive to the formation of SEO, including personality traits, internal and external motivation, family environment, personality features of organizational leaders, and dynamics of the internal and external environment of an organization (Pittino et al., 2017). Thus, it is clear that R2 = 12%, which indicates that the dynamics of Indonesian higher education's internal and external environment are quite realistic because these two variables are part of several antecedents that form the SEO.

Substructure 2:

SEI = 0.05*IIE – 0.01*EES + 0.51*SEO.

(p = 0.463; IIE → SEI), (p = 0.836; EES → SEI), and (p = 0.000; SEO → SEI).

This means that student entrepreneurial intention can directly be influenced by the entrepreneurial orientation of the students themselves (H3b accepted). At the same time, the internal and external environments do not directly foster SEI. Substructure 2 has the power to predict that the population tends to be moderate (R2 = 0.28; Chin, 1998). This finding confirms that a strong student entrepreneurial orientation can increase the entrepreneurial intentions of the students (Martins and Perez, 2020).

Substructure 3:

SEA = 0.15*IIE – 0.11*EES + 0.25*SEO + 0.20*SEI.

(p = 0.038; IIE → SEA), (p = 0.122; EES → SE A), (p = 0.000; SEO → SEA), and (p = 0.000; SEI → SEA).

Substructure 3 indicates that EES does not have the power to influence students to engage in SEA directly but that IIE can foster SEA (H1a accepted). Individual internal factors related to entrepreneurship orientation and entrepreneurial intentions have been proven to accelerate student entrepreneurship activities (H3a and H4 accepted). The strength of substructure 3 (R2 = 0.17) in predicting the population is still relatively weak (Chin, 1998).

Referring to Table 12,

• EES has a direct negative impact on SEI and SEA. Even after analyzing the impact, it is proven that EES is not significant in influencing students' intentions to become entrepreneurs. In addition, it has no impact on the emergence of student entrepreneurial activities (H2a and H2c, rejected).

The external environmental support cannot arouse students' intentions to become entrepreneurs, or even to carry out entrepreneurial activities. This finding is in line with previous research in Indonesia and Japan, which stated that the readiness of instruments (access to capital, social networks, and information) had no significant effect on the entrepreneurial intentions of Indonesian and Japanese students (Indarti, 2015).

For Indonesian students, capital assistance from government and private financial institutions is quite burdensome as they are obliged to repay the capital and the interest charged while still studying. In addition, the procurement of technology and the forms of cooperation offered by entrepreneurs from outside the institution require them to provide feedback on the collaboration results, and they are not sure that they can fulfill such an offer.

• IIE is not significant in influencing students' intentions to become entrepreneurs (H1c rejected).

Based on lexical meaning, the intention is the will (desire in the heart) to do something (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2016) that requires several factors to ignite it. This study confirms that the university's internal and external environment can directly increase student entrepreneurial orientation. Still, it cannot directly influence students' intentions to become entrepreneurs, especially encouraging them to engage in entrepreneurial activities.

The results of this study are in line with previous research, which succeeded in constructing various factors conducive to the formation of entrepreneurial orientation, including personality traits, internal and external motivation, family environment, personality traits of organizational leaders, and dynamics of an organization's internal and external environment (Pittino et al., 2017). Therefore, it is clear that IIE can influence entrepreneurial orientation first and then create entrepreneurial intentions.

The ability of the variable mediators to mediate their antecedents to their consequences in a particular relationship is presented in the decomposition analysis in Table 13.

Institutional Internal Environment as an entrepreneurial ecosystem entity created through eclectic entrepreneurship education with the “Through” and “Embedded” types has proven to significantly influence the performance of SEA directly by 15.1%. This influence was found to increase when mediated by the growth of SEO. The students' eclectic entrepreneurship education increased their entrepreneurial intentions and ultimately impacted SEA performance up to 21.3%. This proves that SEO and SEI are significant mediating variables for IIE in influencing the performance of SEA. Furthermore, increasing SEO can directly and significantly influence the SEI by 51.5%. This is an interesting finding because, when viewed with respect to the direct influence of SEO on SEA, which is only 25%, increasing SEO further increases SEI to 35% because of the SEI that develops in students due to their increased entrepreneurial orientation.

Discussion

“Eclectic Entrepreneurship Education” Is a Novelty in Indonesian Higher Education

Through contingency testing of demographic data in this study, it has been empirically proven that the pattern of knowledge-based entrepreneurship education alone is not significantly correlated with entrepreneurial activities carried out by students while in the college (Astuty et al., 2021). Meanwhile, the contingency relationship between students' entrepreneurial experiences before entering college and entrepreneurial activities in college shows a significant relationship. It proves that a practical education pattern is significantly correlated with the entrepreneurial activities of young entrepreneurs.

The next question that arises is, what kind of education and learning pattern can trigger an increase in entrepreneurial activities for college students and the growth of students' new businesses?

“Through” and “Embedded” types of entrepreneurship education were found to be valid, reliable, and suitable for Indonesian entrepreneurship education. “Through” type accelerates the development of students' intentions to start their own business (Ollila and Williams-Middleton, 2011; Baluku et al., 2019), improve entrepreneurial competence (Gibson and Tavlaridis, 2018; Hägg and Kurczewska, 2019; Williams Middleton et al., 2019), and enhance the effectiveness of entrepreneurial learning (Ratten and Usmanij, 2020). Meanwhile “Embedded” type refers to embedding entrepreneurship education in a particular discipline to make it relevant for that specific discipline so that it can create entrepreneurial activities that have career relevance and the potential to generate intellectual property (Blake Hylton et al., 2020), facilitate the embedding of business study program students to take specific courses according to their specialization in non-business study programs so that they are expected to provide the necessary context (Thomassen et al., 2019), and to improve the ability to construct knowledge in the work-life of entrepreneurs (Bridgstock, 2013). “Through” and “Embedded” types simultaneously provide direct knowledge and practical learning to equip students with comprehensive entrepreneurial experience (Gieure et al., 2019).

Considering these findings, the authors formulate this entrepreneurship learning type as “Eclectic Entrepreneurship Education.” This nomenclature aligns with the Indonesian dictionary, which states that training or education carried out using various techniques, approaches, and methods simultaneously is called eclectic education (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2016). “Eclectic Entrepreneurship Education” is a novelty term from this research that higher education decision-makers in Indonesia can use to re-orient the entrepreneurship learning curriculum to create a conducive university entrepreneurial ecosystem.

“Through” dimension of Eclectic Entrepreneurship Education (EEET) emphasizes learning by doing but in a “safe” mode, such as in university business incubators and internship programs for specific business units or companies. Examples from the “through” dimension include:

▪ the existence of business incubators at universities

▪ the presence of experiential learning through internship programs for various businesses/industry

▪ the availability of experiential learning through collaboration with entrepreneurs

▪ facilitating students to obtain business funding from outside parties

▪ providing mentoring programs from entrepreneurs to students

▪ facilitating students to interact with the market

“Embedded” dimension of the Eclectic Entrepreneurship Education (EEEE) emphasizes direct entrepreneurship learning in a particular discipline so that it is relevant to the field of specialization and can generate intellectual property. Examples from the “Embedded” dimension include:

▪ the availability of embedding entrepreneurship courses in the curriculum of non-business study programs

▪ the inclusion of business study students in non-business study programs

▪ the opportunity for students to enroll in several classes according to their specialization

▪ to further improve the diversity of skills needed by students

Entrepreneurship Eclectic Education strengthens the university's entrepreneurial ecosystem because of the intersection of interactions between the university's internal and external environment. This learning model then strengthens the entrepreneurial orientation of students, which in turn can generate entrepreneurial intentions that result in entrepreneurial activities carried out by students. The empirical model of the university ecosystem in forming student entrepreneurship activities in several universities in Indonesia is presented in Figure 4.

The educators and institutions need to understand the importance of a pragmatic and comprehensive approach for their students to generate their interest, express increased willingness to become entrepreneurs, and provide the necessary motivation to engage in entrepreneurial activities to become potential entrepreneurs. The finding from this study confirms that SEI is proven to be a positive and significant mediator for SEO in increasing SEA. Hence, it can be concluded that the entrepreneurial ecosystem in which there is a conducive internal environment accompanied by interactions with external parties can contribute positively to individual attributes such as SEO and SEI for the realization of the SEA (Knight and Yorke, 2003; Hulme et al., 2014; Mehtap et al., 2017; Kuratko and Morris, 2018).

Research Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

This study has several research limitations, including:

a) Sampling was only in 18 universities in Java and Sumatra. Yet, it was done because 75% of universities in Indonesia are spread over two of the five major islands in Indonesia, namely Java and Sumatra. Meanwhile, another 25% of universities spread across the islands of Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and Papua were not included in the sampling. Researchers had limited resources in distributing samples to universities spread across three other major islands in Indonesia. However, the goodness of fit test included the RMSEA and CFI values in the model fit criteria. It can be emphasized that the model built based on the empirical evidence meets the requirements of the best-fit model, so it means that the model can estimate the population covariance matrix, which tends not to differ from the sample data covariance matrix. It is suggested that future research on this study's results adopts the empirical model to study universities that are spread over three other major islands in Indonesia.

b) The empirical evidence revealed something quite surprising regarding SEO, which significantly increases SEI by 51% directly though this intention results in the realization of SEA by 20%. Therefore, future research can study the effect of intervening variables between the SEI and SEA and investigate and verify the previous findings that all entrepreneurial intentions do not lead to concrete actions in the form of business creation (Shirokova et al., 2016). This, therefore, could be the “next task” to find the factors that can facilitate students' entrepreneurial intentions into actual entrepreneurial activities.

c) This study included just one direct antecedent of SEI in its research model, namely SEO. It is suggested that further research be undertaken to examine the competence of lecturers in frontline universities who can directly deliver “entrepreneurship eclectic education” to students, as recommended in this study. This is also based on other research findings that institutions that provide entrepreneurship education must have competent lecturers who can ignite the fire of entrepreneurial intentions in students (Iwu et al., 2019).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Prof. Dr. Tirta Nugraha Mursitama, S.Sos., M.M., Ph.D. (BINUS University), Prof. Dr. Mts. Arief, M.M., MBA., CPM. (BINUS University), Prof. Dr. Sasmoko, M.Pd. (BINUS University), and Nugroho Juli Setiadi, S.E., M.M., Ph.D. (BINUS University). Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

EA contributed to the literature review, model development, data processing, and analysis. OY and CR contributed to data collection and report preparation. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Research and publications are funded by BINUS University through Basic Research Internal Grants with implementation agreement No: 079/VR.RTT/VIII/2020.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to all parties who approved undertaking this research and BINUS University for funding this research. The authors also thank all colleagues who helped disseminate the research instrument and all respondents who participated in this study. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

References

Astuty, E., and Yustian, O. R. (2021). Analysis of the entrepreneurial intention's emergence at business and non-business students in Indonesia. J. Pendidikan Prog. 11, 27–38. doi: 10.23960/jpp.v11.i1.202103

Astuty, E., Yustian, O. R., and Ratnapuri, C. I. (2021). “Gender, student background, and the implications for the emergence of student entrepreneurial activities,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management (Singapore), 1729–1737.

Baluku, M. M., Matagi, L., Musanje, K., Kikooma, J. F., and Otto, K. (2019). Entrepreneurial socialization and psychological capital: cross-cultural and multigroup analyses of impact of mentoring, optimism, and self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Educ. Pedagogy 2, 5–42. doi: 10.1177/2515127418818054

Bayarçelik, E. B., and Özşahin, M. (2014). How entrepreneurial climate effects firm performance? Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 150, 823–833. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.09.091

Bazan, C., Shaikh, A., Frederick, S., Amjad, A., Yap, S., Finn, C., et al. (2019). Effect of memorial university's environment and support system in shaping entrepreneurial intention of students. J. Entrep. Educ. 22, 1–35.

Blake Hylton, J., Mikesell, D., Yoder, J.D., and LeBlanc, H. (2020). Working to instill the entrepreneurial mindset across the curriculum. Entrep. Educ. Pedagogy 3, 86–106. doi: 10.1177/2515127419870266

Bosma, N., Hill, S., Ionescu-Somers, A., Kelley, D., Levie, J., Tarnawa, A., et al. (2020). The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM): 2019/2020 Global Report. London.

Bridgstock, R (2013). Not a dirty word: arts entrepreneurship and higher education. Arts Human. High. Educ. 12, 122–137. doi: 10.1177/1474022212465725

Brown, A (2018). Embedding research and enterprise into the curriculum adopting Student as Producer as a theoretical framework. High. Educ. Skills Work Based Learn. 8, 29–40. doi: 10.1108/HESWBL-09-2017-0064

Chavez, R., Yu, W., Jacobs, M. A., and Feng, M. (2017). Manufacturing capability and organizational performance: the role of entrepreneurial orientation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 184, 33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2016.10.028

Cooper, D. R., and Schindler, P. S. (2014). Business Research Methods. 12th Edn. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Emoke-Szidónia, F (2015). International entrepreneurial orientation and performance of romanian small and medium-sized firms: empirical assessment of direct and environment moderated relations. Proc. Econ. Fin. 32, 186–193. doi: 10.1016/S2212-5671(15)01381-7

Fong, T. W. M (2020). Design incubatees' perspectives and experiences in Hong Kong. High. Educ. Skills Work Based Learn. 10, 481–496. doi: 10.1108/HESWBL-10-2019-0130

Franco, M., Haase, H., and Lautenschläger, A. (2010). Students' entrepreneurial intentions: an inter-regional comparison. Educ. Train. 52, 260–275. doi: 10.1108/00400911011050945

Galindo-Martín, M. A., Méndez-Picazo, M. T., and Castaño-Martínez, M. S. (2019). The role of innovation and institutions in entrepreneurship and economic growth in two groups of countries. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 26, 485–502. doi: 10.1108/IJEBR-06-2019-0336

Galvão, A. R., Marques, C. S. E., Ferreira, J. J., and Braga, V. (2020). Stakeholders' role in entrepreneurship education and training programmes with impacts on regional development. J. Rural Stud. 74, 169–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.01.013

Gibson, D., and Tavlaridis, V. (2018). Work based learning for enterprise education? The case of Liverpool John Moores university “live” civic engagement projects for students. High. Educ. Skills Work-Based Learn. 8, 5–14. doi: 10.1108/HESWBL-12-2017-0100

Gieure, C., Benavides-Espinosa, M., and Roig-Dobón, S. (2019). Entrepreneurial intentions in an international university environment. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 25, 1605–1620. doi: 10.1108/IJEBR-12-2018-0810

Gupta, V. K., Dutta, D. K., Guo, C. G., and Javadian, G. (2016). Classics in entrepreneurship research: enduring insights, future promises. N. Engl. J. Entrep. 19, 7–23. doi: 10.1108/NEJE-19-01-2016-B001

Hägg, G., and Kurczewska, A. (2019). Toward a learning philosophy based on experience in entrepreneurship education. Entrep. Educ. Pedagogy 2019:251512741984060. doi: 10.1177/2515127419840607

Hulme, E., Thomas, B., and DeLaRosby, H. (2014). Developing creativity ecosystems: preparing college students for tomorrow's innovation challenge. About Campus 19, 14–23. doi: 10.1002/abc.21146

Indarti, N (2015). Factors affecting entrepreneurial intentions among indonesian students. Fact. Affect. Entrep. Intent. Among Indones. Stud. 19, 57–70. doi: 10.22146/jieb.6585

Indonesian Ministry of Cooperatives MSMEs (2020). Through Training, Ministry of Cooperation and SMEs Increase the Competitiveness of MSMEs in Super Priority Tourism Destinations. Jakarta. Available online at: https://kemenkopukm.go.id/read/melalui-pelatihan-kemenkop-dan-ukm-tingkatkan-daya-saing-umkm-di-destinasi-wisata-super-prioritas (accessed June 6, 2020).

Iwu, C. G (2019). Entrepreneurship education, curriculum and lecturer-competency as antecedents of student entrepreneurial intention. Int. J. Manage. Educ. 2019:100295. doi: 10.1016/j.ijme.2019.03.007

Keh, H. T., Nguyen, T. T. M., and Ng, H. P. (2007). The effects of entrepreneurial orientation and marketing information on the performance of SMEs. J. Bus. Ventur. 22, 592–611. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.05.003

Knight, P. T., and Yorke, M. (2003). Employability and good learning in higher education. Teach. High. Educ. 8, 3–16. doi: 10.1080/1356251032000052294

Kourilsky, M. L., and Walstad, W. B. (1998). Entrepreneurship and female youth: knowledge, attitudes, gender differences, and educational practices. J. Bus. Ventur. 13, 77–88. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9026(97)00032-3

Kristiansen, S (2001). Promoting African pioneers in business: what makes a context conducive to small-scale entrepreneurship? J. Entrep. 10, 43–69. doi: 10.1177/097135570101000103

Kristiansen, S (2002). Individual perception of business contexts: the case of smallscale entrepreneurs in Tanzania. J. Dev. Entrep. 7.

Kuratko, D. F., and Morris, M. H. (2018). Corporate entrepreneurship: a critical challenge for educators and researchers. Entrep. Educ. Pedagogy 1, 42–60. doi: 10.1177/2515127417737291

Lavelle, B. A (2019). Entrepreneurship education's impact on entrepreneurial intention using the theory of planned behavior: evidence from chinese vocational college students. Entrep. Educ. Pedagogy 2019:251512741986030. doi: 10.1177/2515127419860307

Li, Y. H., Huang, J. W., and Tsai, M. T. (2009). Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: the role of knowledge creation process. Indus. Mark. Manage. 38, 440–449. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2008.02.004

Lumpkin, G. T., and Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifyang the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linkingit to performance. Acad. Manage. Rev. 21, 135–172. doi: 10.2307/258632

Lumpkin, G. T., and Dess, G. G. (2001). Linking two dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation to firm performance: the moderating role of environment and industry life cycle. J. Bus. Ventur. 16, 429–451. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9026(00)00048-3

Lyon, D. W., Lumpkin, G. T., and Dess, G. G. (2000). Enhancing entrepreneurial orientation research: operationalizing and measuring a key strategic decision making process. J. Manage. 26, 1055–1085. doi: 10.1177/014920630002600503

Martins, I., and Perez, J. P. (2020). Testing mediating effects of individual entrepreneurial orientation on the relation between close environmental factors and entrepreneurial intention. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 26, 771–791. doi: 10.1108/IJEBR-08-2019-0505

McDonald, S., Gertsen, F., Rosenstand, C. A. F., and Tollestrup, C. (2018). Promoting interdisciplinarity through an intensive entrepreneurship education post-graduate workshop. High. Educ. Skills Work Based Learn. 8, 41–55. doi: 10.1108/HESWBL-10-2017-0076

Mehtap, S., Pellegrini, M. M., Caputo, A., and Welsh, D. H. B. (2017). Entrepreneurial intentions of young women in the Arab world: socio-cultural and educational barriers. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 23, 880–902. doi: 10.1108/IJEBR-07-2017-0214

Ministry of Education Culture (2016). KBBI Online. Available online at: https://kbbi.kemdikbud.go.id/ (accessed July 2, 2021).

Nabi, G., Liñán, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N., and Walmsley, A. (2017). The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: a systematic review and research agenda. Acad. Manage. Learn. Educ. 16, 277–299. doi: 10.5465/amle.2015.0026

Odewale, G. T., Hani, S. H., Migro, S. O., and Adeyeye, P. O. (2019). Entrepreneurship education and students' views on self-employment among international postgraduate students in universiti utara malaysia. J. Entrep. Educ. 22, 1–15.

Ollila, S., and Williams-Middleton, K. (2011). The venture creation approach: integrating entrepreneurial education and incubation at the university. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. Manage. 13, 161–178. doi: 10.1504/IJEIM.2011.038857

Pittaway, L., and Edwards, C. (2012). Assessment: examining practice in entrepreneurship education. Educ. Train. 54, 778–800. doi: 10.1108/00400911211274882

Pittino, D., Visintin, F., and Lauto, G. (2017). A configurational analysis of the antecedents of entrepreneurial orientation. Eur. Manage. J. 35, 224–237. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2016.07.003

Ratten, V., and Usmanij, P. (2020). Entrepreneurship education: time for a change in research direction? Int. J. Manage. Educ. 2019:100367. doi: 10.1016/j.ijme.2020.100367

Sahin, F., Karadag, H., and Tuncer, B. (2019). Big five personality traits, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention: a configurational approach. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 25, 1188–1211. doi: 10.1108/IJEBR-07-2018-0466

Sancho, M. P. L., Martín-Navarro, A., and Ramos-Rodríguez, A. R. (2020). Will they end up doing what they like? The moderating role of the attitude towards entrepreneurship in the formation of entrepreneurial intentions. Stud. High. Educ. 45, 416–433. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2018.1539959

Schwab, K (2018). The Global Competitiveness Index Report 2017-2018. World Economic Forum. Available online at: http://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/110008131965/

Shirokova, G., Osiyevskyy, O., and Bogatyreva, K. (2016). Exploring the intention-behavior link in student entrepreneurship: moderating effects of individual and environmental characteristics. Eur. Manage. J. 34, 386–399. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2015.12.007

Souitaris, V., Zerbinati, S., and Al-Laham, A. (2007). Do entrepreneurship programmes raise entrepreneurial intention of science and engineering students? The effect of learning, inspiration and resources. J. Bus. Ventur. 22, 566–591. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.05.002

Thomassen, M. L., Middleton, K. W., Ramsgaard, M. N., Neergaard, H., and Warren, L. (2019). Conceptualizing context in entrepreneurship education: a literature review. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 26, 863–886. doi: 10.1108/IJEBR-04-2018-0258

Walter, A., Auer, M., and Ritter, T. (2006). The impact of network capabilities and entrepreneurial orientation on university spin-off performance. J. Bus. Ventur. 21, 541–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.02.005

Walter, S. G., Parboteeah, K. P., and Walter, A. (2013). University departments and self-employment intentions of business students: a cross-level analysis. Entrep. Theory Pract. 37, 175–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00460.x

Williams Middleton, K., Padilla-Meléndez, A., Lockett, N., Quesada-Pallarès, C., and Jack, S. (2019). The university as an entrepreneurial learning space: the role of socialized learning in developing entrepreneurial competence. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 26, 887–909. doi: 10.1108/IJEBR-04-2018-0263

Zabelina, E., Deyneka, O., and Tsiring, D. (2019). Entrepreneurial attitudes in the structure of students' economic minds. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 25, 1621–1633. doi: 10.1108/IJEBR-04-2018-0224

Keywords: entrepreneurship ecosystem, institution environment, entrepreneurship activity, entrepreneurship intention, entrepreneurship orientation

Citation: Astuty E, Yustian OR and Ratnapuri CI (2022) Building Student Entrepreneurship Activities Through the Synergy of the University Entrepreneurship Ecosystem. Front. Educ. 7:757012. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.757012

Received: 11 August 2021; Accepted: 20 April 2022;

Published: 09 June 2022.

Edited by:

George Waddell, Royal College of Music, United KingdomReviewed by:

Karin Širec, University of Maribor, SloveniaGuido Baltes, Hochschule Konstanz University of Applied Sciences, Germany

Copyright © 2022 Astuty, Yustian and Ratnapuri. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eriana Astuty, ZXJpYW5hLmFzdHV0eUBiaW51cy5hYy5pZA==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share last authorship

Eriana Astuty

Eriana Astuty Okky Rizkia Yustian

Okky Rizkia Yustian Chyntia Ika Ratnapuri

Chyntia Ika Ratnapuri