- 1Centre for Learning Enhancement and Research, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 2Faculty of Medicine, Nethersole School of Nursing, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 3Faculty of Medicine, Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 4Faculty of Medicine, School of Biomedical Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 5Faculty of Social Sciences, Department of Social Work, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 6Faculty of Sciences, School of Life Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 7Faculty of Education, Department of Sport Sciences and Physical Education, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 8Faculty of Business Administration, Department of Decision Sciences and Managerial Economics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 9Faculty of Art, Department of Linguistics and Modern Languages, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 10Faculty of Engineering, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Studies have provided evidence that Interprofessional Education (IPE) can improve learners’ attitudes, knowledge, skills, behaviors, and competency. Traditionally, IPE is commonly seen in the healthcare professional training in tertiary education. Aging is a global issue that requires more than just a single healthcare sector. It requires interdisciplinary collaboration and understanding to tackle the issues. Therefore, IPE is essential for nurturing university students to tackle the ever-changing global challenges. In addition, different hurdles can hinder IPE development. To have a better understanding of the feasibility, acceptance, and educational value of IPE in Hong Kong, we conducted a cross-sectional quantitative study. We invited teachers and students from a Hong Kong university to fill in an online survey that evaluated their understanding and participation in IPE, their attitude toward IPE, and the barriers to developing IPE from March to June 2020. Among the 37 academic staff and 572 students who completed the survey, 20 (54.1%) teachers and 422 (73.8%) students had never heard of IPE before, and 26 (70.3%) teachers and 510 (89.2%) students had never participated in any IPE activities. Major barriers reported by teachers included an increase in teaching load (72.9%), lack of administrative support (72.9%), lack of financial support and limited budget (67.5%), difficulty to make logistic arrangements (64.8%), and problems with academic schedules and calendars (62.1%). The survey findings revealed that despite the positive attitude of university teachers and students toward IPE, barriers that could hinder the development of IPE included heavy teaching and administrative load and logistic arrangement for classroom arrangement and academic scheduling involving multiple faculties.

Introduction

Interprofessional Education (IPE) occurs when two or more professionals learn about, from, and with each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes (World Health Organization, 2010). Here, the professional is an all-encompassing term that includes individuals with the knowledge and/or skills to contribute to the physical, mental, and social wellbeing of a community (World Health Organization, 2010). Interprofessional teamwork is crucial in healthcare practice. The Institute of Medicine states that patients receive better and safer care when healthcare professionals work effectively as a team, understanding each other’s roles and communicating effectively (Greiner et al., 2003). Nevertheless, the provision of holistic patient care requires a joint effort by members from non-healthcare backgrounds (Smith et al., 2013; Green and Johnson, 2015). In addition, interprofessional collaboration is the key to managing the ever-changing global challenges (Walsh et al., 1975; Goring et al., 2014). A plethora of empirical studies have provided evidence that IPE can positively improve learners’ attitudes, knowledge, skills, behaviors, and competency (Berger-Estilita et al., 2020). IPE appears as an interaction that involves students and professional practitioners of various disciplines, in which every individual in the group identifies themselves with professional skill sets, and is expected to maintain, create, and strengthen their professional identity (Haugland et al., 2019). Studies on the effectiveness of interprofessional programs have demonstrated statistically significant increases in participants’ scores on readiness for interprofessional learning, attitude toward IPE, communication skills, responsibility and accountability in healthcare, cooperation, and collaborative team-based work skills (Berger-Estilita et al., 2020). Hence, it is proposed that IPE plays an important role in students’ professional attitude, professional and collaborative competency, and knowledge enhancement. Traditionally, IPE is commonly seen in healthcare professional training in tertiary education. Effective communication and cooperation by interprofessional teams are paramount for patients’ holistic and comprehensive management and the enhancement of safe and effective care. This is especially important when caring for an aging population, as older adults normally present with a boarder spectrum of co-morbidities, coupled with cognitive, emotional, and social symptoms. There is increasing evidence that team-based models lead to optimal healthcare. In addition, most medical errors and incidents leading to patient harm are related to poor collaboration (Wai et al., 2020). Moreover, collaborative practice plays a crucial part in the coordination of current healthcare, health management and resources, and the moderation of feelings and outcomes of professional practitioners within the medical system, and it helps to decrease patients’ negative emotions (Solberg et al., 2015; Wai et al., 2020). To prepare students for collaborative practice contexts, IPE has emerged as a pedagogic approach involving social interactions which represent the knowledge, skills, and competencies of their profession as they make contributions to team healthcare choices (Haugland et al., 2019). Team-oriented care is now identified as an optimal primary care mode especially in the care of the aging population, as it links the practitioners of different disciplines and provides a platform for collaboration designed to address the complexity of healthcare management. Aging is a global issue that requires more than just a single healthcare sector. It requires interdisciplinary collaboration and understanding to tackle the issues. Therefore, IPE in university settings should not be limited to a few disciplines within one faculty only. Students should understand the strengths of different professions and they should be equipped with the ability to cooperate with peers across faculties. In this article, we aimed to share our findings from a cross-sectional qualitative study on IPE implementation in a Hong Kong university. We summarize the major barriers that teachers face and discuss the possible solutions to the challenges.

Methods

To evaluate the feasibility, acceptance, and educational values of IPE, we conducted a cross-sectional qualitative study from March to June 2020. We invited the teachers (n = 1,596) and students (n = 17,606) from all faculties at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) to fill in an online survey on their experience with IPE through email. The online survey evaluated their understanding and participation in IPE, their attitude toward IPE, and the barriers to developing IPE among teachers and students at CUHK. The survey was developed by our research team to evaluate the understanding of and participation in IPE, the attitude toward IPE, the barriers to developing IPE, and the impact of IPE on teachers and students at CUHK.

Instrument

The survey was composed of questions that collected information on subjects’ (1) demographics, (2) understanding and participation in IPE, (3) attitude toward IPE, (4) the barriers to developing IPE, and (5) impact of IPE.

Perception of Interprofessional Education

A total of five questions on students’ IPE experiences (i.e., “Have you heard of IPE in your faculty?,” “Have you ever participated in any IPE program?,” “Which type of IPE program you have participated?”), willingness for IPE engagement (e.g., “Even if you have never joined any IPE program in your faculty, would you consider participating in IPE program in your future?”), and prefer format for IPE (e.g., “Which format of IPE activities you would prefer most?”) were raised in the online survey.

Attitudes toward Interprofessional Education

Eleven statements surveying students’ attitudes toward IPE were extracted and modified based on the Attitudinal Survey on Interdisciplinary Education developed by Gardner et al. (2002) and the implementation context of IPE in CUHK (i.e., “interprofessional education should be a goal on CUHK campus.”).

Perceived barriers

Fifteen barriers were listed and modified according to the context of CUHK and Gardner et al.’s findings (Gardner et al., 2002). The barriers were categorized into two dimensions: institutional level (i.e., “Lack of financial support and limited budget.”) and individual level (i.e., “Students’ workload is already fully packed”) based on previous literature (Lawlis et al., 2014).

Expectations for Interprofessional Education

The instrument consists of eight statements extracted from the potential positive impacts of IPE proposed by Darlow et al. (2018) to understand students’ expectations for IPE from the dimensions of collaborative learning (i.e., “Students learn to appreciate different perspectives and recognize input from other professions.”) and professional development (i.e., “Students would have a better understanding of their own professional roles, responsibilities, expertise and also the roles of others”).

We used the 7-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree; 2 = Disagree; 3 = Somewhat disagree; 4 = Neither disagree nor agree; 5 = Somewhat agree; 6 = Agree; and 7 = Strongly agree) to evaluate the understanding of IPE, barriers of IPE implementation, Students’ attitudes toward IPE, and impacts of IPE. The validation process of the surveys was conducted in January 2020. We invited both teachers and students to respond to the draft surveys and commented on the clarity of the surveys. We then revised the surveys according to the comments of both teachers and students before sending the surveys to the ethics committee. After we obtained the approval from the ethics committee, we sent out the surveys via mass email to all students and teachers at CUHK. The study had been approved by the Survey and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee of CUHK (Reference no.: SBRE-19-501) and subjects’ informed consent was obtained before they filled in the questionnaire.

Descriptive statistics were conducted to identify students’ awareness of IPE. The Chi-square tests, independent t-tests, and ANOVAs were performed to examine if there are any differences existed in students’ perceptions, attitudes, and expectations toward IPE among students of varied demographic characteristics (i.e., gender, year of study, and faculty). Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) version 26 was used to analyze the survey data.

Results

A total of 37 academic staff (response rate: 2.3%) from the 7 faculties, namely, the Faculty of Arts, the Faculty of Business Administration, the Faculty of Education, the Faculty of Engineering, the Faculty of Medicine, the Faculty of Science, and the Faculty of Social Science, and 572 (response rate: 3.2%) students from the 7 faculties above and the Faculty of Law completed the questionnaire. The faculty distributions for teachers are Medicine (29.7%), Science (24.3%), Social Sciences (16.2%), Business Administration (10.8%), Engineering (10.8%), Arts (8.1%), Education (8.1%), and Law (2.7%). Among all the teacher respondents, 27% of them had teaching experience for 6–10 years followed by 18.9% who had over 20 years of teaching experience. Therefore, most of the teacher respondents are experienced teachers. The faculty distributions for students are Medicine (25.9%), Social Sciences (18.9%), Arts (16.8%), Science (15.6%), Business Administration (10.8%), Engineering (6.6%), Education (5.1%), and Law (0.3%). Among the student respondents, 35.8% were year 1 students followed by 33.9% were year 2 students. Therefore, the student respondents were junior students.

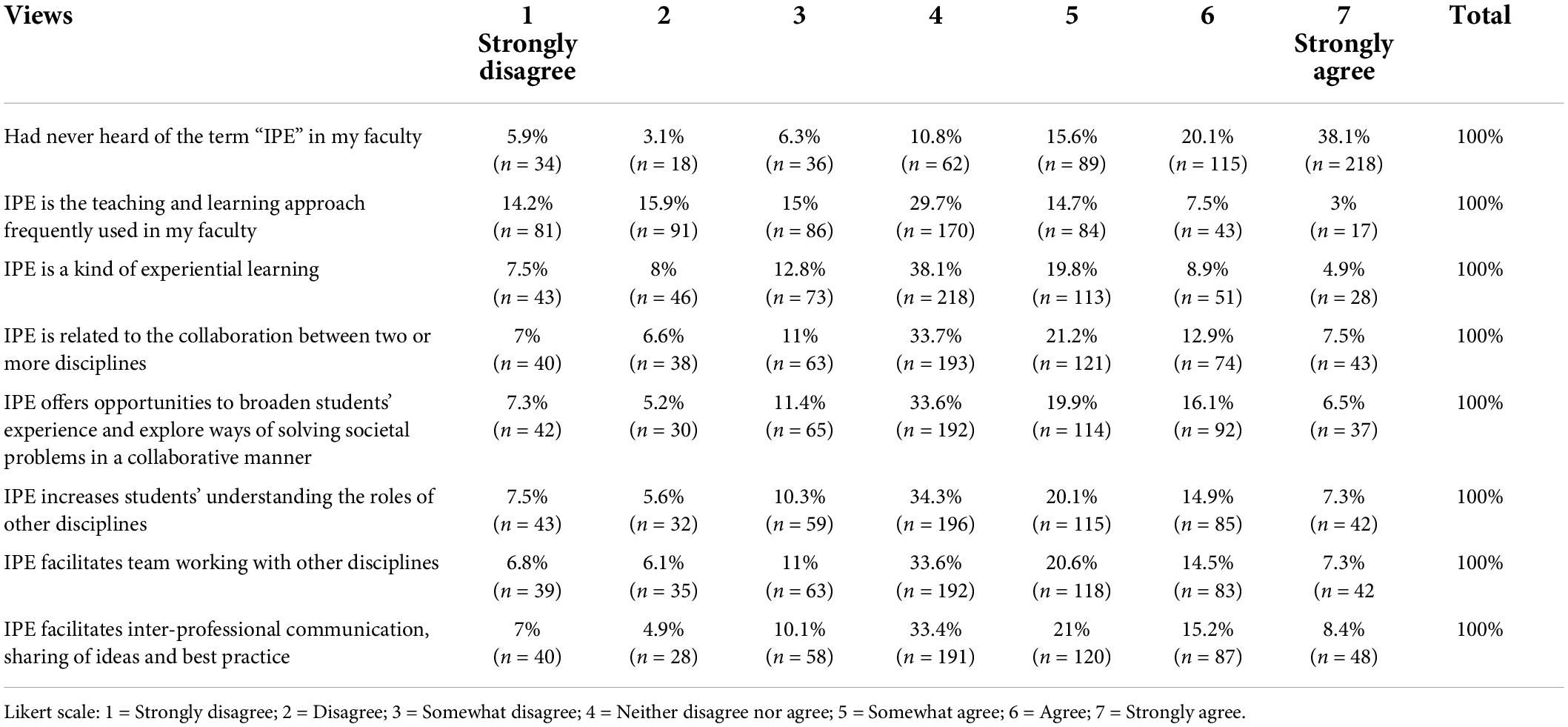

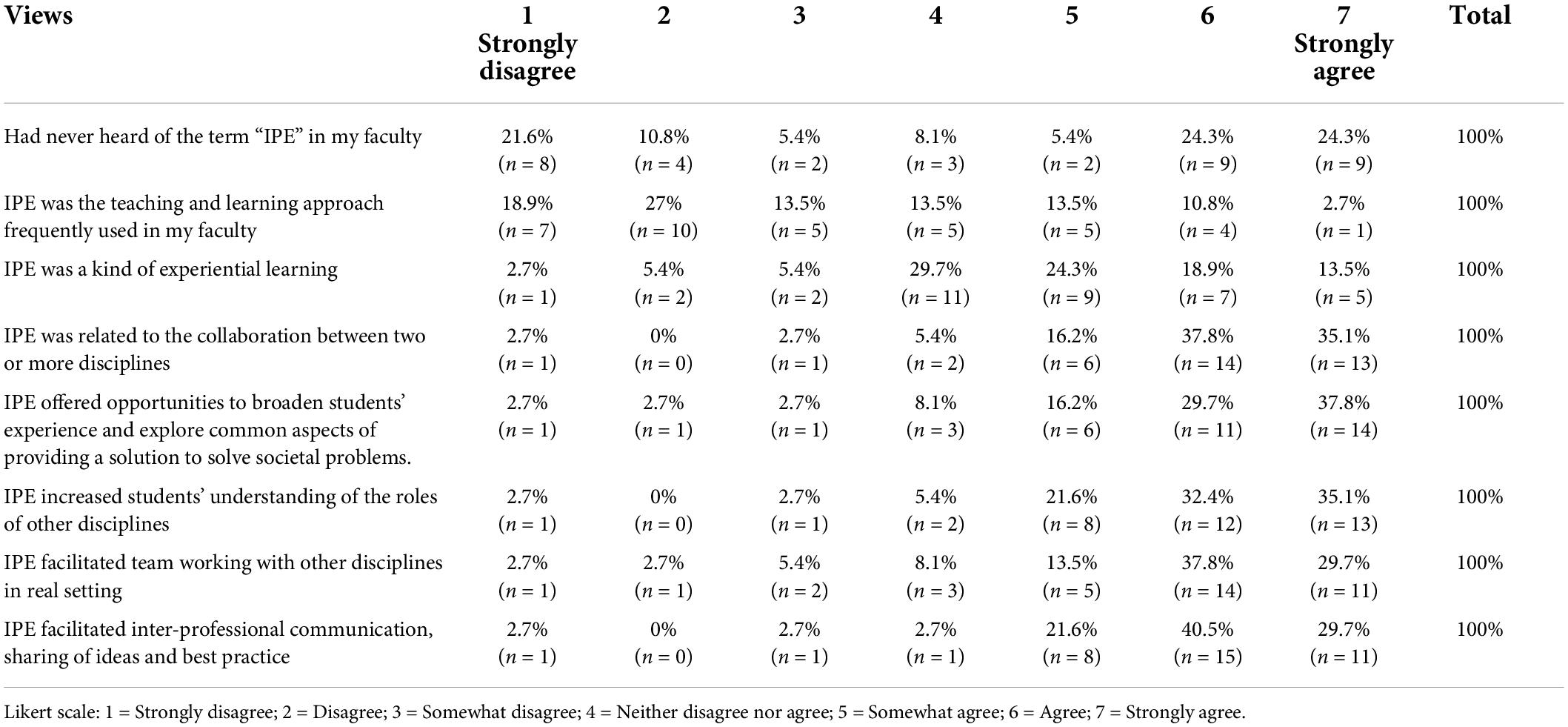

The survey results revealed that both teachers and students had limited engagement in IPE activities. There were 20 (54.1%) teachers and 422 (73.8%) students who had never heard of IPE before (Tables 1, 2). In addition, 26 (70.3%) teachers and 510 (89.2%) students had never participated in any IPE activities. Both teachers and students tended to hold a positive attitude toward IPE, and students were eager to gain IPE learning experiences. Over half of the surveyed students wished their faculties could provide IPE opportunities and they welcomed courses taught by teachers from other faculties. Over 80% of teachers agreed that IPE facilitated team working with other disciplines in a real setting, and it offered the opportunities to broaden students’ experience and explore solutions to societal problems. Over 90% of teachers agreed that IPE could facilitate interprofessional communication and the sharing of ideas and best practices.

Examples of the IPE program offered by CUHK included credit-bearing courses such as university general education courses, didactic elective courses, and major required courses, as well as service-learning activities and student organization activities. Around 20% of students had participated in IPE programs through taking university general education courses, while less than 10% had participated in the others. Around 20% of teachers had organized or participated in university general education courses or service-learning activities for IPE. Participation rates in the other categories were around 10%.

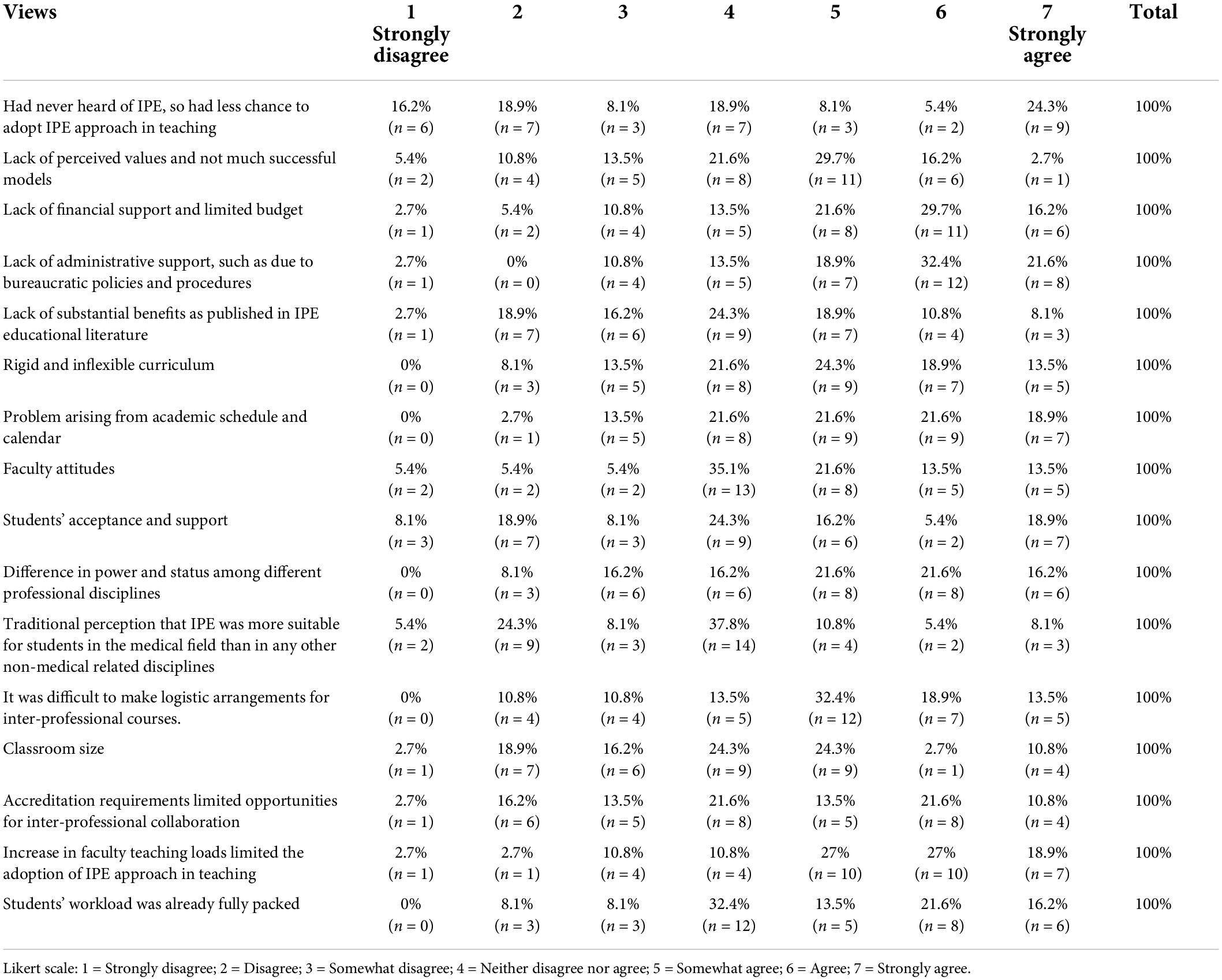

Our survey results showed that both teachers and students were positive about IPE. Nevertheless, their participation rates in IPE were very low. Thus, we went on to investigate the problems behind and the major hurdles teachers and students faced when implementing IPE. Major barriers reported by teachers included an increase in teaching load (72.9%), lack of administrative support (72.9%), lack of financial support and limited budget (67.5%), difficulty to make logistic arrangements (64.8%), and problems with academic schedules and calendars (62.1%) (Table 3). On the other hand, most students (73.1%) did not participate in IPE learning activities because they had never heard of this concept. Around 50% of students were unable to participate due to heavy workload or problems arising from academic schedules or calendars (Table 4).

Discussion

The current survey results revealed that although the majority of university teachers and students held a positive attitude toward IPE, their understanding and participation rates in IPE were very low. These results reflect a phenomenon that the development and promotion of IPE in Hong Kong remain in their infancy stage. University students in Hong Kong lack opportunities to learn about and engage in interprofessional learning. The results were also consistent with our literature search that limited interventions and studies on IPE had been conducted for students in Hong Kong. Perceived barriers were labeled and investigated in this study to understand the feasibility of IPE in Hong Kong and for the design of the IPE program. Two levels of barriers were identified in the context of Hong Kong tertiary institute, namely, individual level and institutional level. Barriers that could hinder the development of IPE included heavy teaching and administrative load and logistic arrangement for classroom arrangement and academic scheduling involving multiple faculties. These barriers were also noted in previous studies (Lawlis et al., 2014; Memarpour et al., 2015). In addition, interdisciplinary approaches are not novel to education. The concept of this approach has been related to the educational movement in the 20th century (Vars, 1991). It allows students to understand knowledge from different perspectives and in a more coherent manner (Styron, 2013). Interprofessional teamwork is highly valued in the future workplace for our students. It is of particular importance in the human services sectors, namely, health, education, and community services (Ponte et al., 2010). It is important for teachers to demonstrate the importance and value of IPE to students. As previous studies have shown that students in IPE were likely to have better collaboration and respect and positive attitudes toward interprofessional teams in patient care after they graduated (Barr et al., 2005; Diane et al., 2011). The Institute of Medicine and the World Health Organization stresses that healthcare professionals should be educated to deliver patient-centered care as members of an interprofessional team (Greiner et al., 2003; World Health Organization, 2010). There are assumptions that healthcare staff from all sectors know how to cooperate as a team. Unfortunately, it deviates from reality as ineffective communication between medical professionals has led to disruptive patient care (O’Daniel and Rosenstein, 2008). It is important for tertiary educational institutions to prepare their students to meet and recognize the needs in the real-world career market and to go beyond the mastery of content and low-level thinking (Styron, 2013). Thus, the importance of IPE in university education should not be underestimated. At CUHK, we also recognize the importance of interdisciplinary education as one of the strategic goals in education. Nevertheless, the proper implementation of IPE requires different levels of understanding and frameworks in place. We need to have a consensus on a competency framework that is agreed upon by all the stakeholders. Previously, the Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) has published 38 competencies across four domains, namely, (1) values/ethics for (2) interprofessional practice, (3) roles/responsibilities, and (4) interprofessional communication and teams and teamwork (Interprofessional Education Collaborative, 2016). When developing the new IPE programs in tertiary institutions, we should evaluate the feasibility to incorporate these competencies in the training programs and how to assess and measure the knowledge transferability to students. The IPE curriculum should be regularly reviewed and revised to address the feedback from both teachers and students. It is also important to note that the IPEC is in the process to review the core competencies guidelines starting in May 2021 (Interprofessional Education Collaborative, 2022). The release of the new IPEC core competencies guidelines will be published in early 2023 (Interprofessional Education Collaborative, 2022). As a result, the educators should be alerted of these new changes and evaluate the validity of the contents in the curriculum, whether it is up-to-date. The four-step cyclical process was previously mentioned in Wang et al. (Wang and Zorek, 2016). First, a solid implementation plan with specific educational goals and objectives should be placed before the execution of IPE. The strengths and weaknesses of students should be considered when collaborative practical skill training is to be developed (Wang and Zorek, 2016). Second, practical IPE experiences should be engaged in the curriculum with targeted skills enhancement (Wang and Zorek, 2016). Third, an effective system for student reflection and the teaching team’s feedback should be in place (Wang and Zorek, 2016). Finally, a review and revision process should be incorporated to address the students’ and teachers’ feedback and reflection (Wang and Zorek, 2016).

Undoubtedly, different professionals in the healthcare team should understand each other’s strengths and collaborate together to maximize treatment outcomes. However, there are many other factors that impact patients’ quality of life. Take a stroke patient as an example. Issues on post-discharge care, financial stress, social support, and psychological well-being can cause a great burden to the patient and his family. While healthcare staff may not be able to address the above problems, other professionals can play their roles (Gabrielová and Veleminsky, 2014; Burmeister et al., 2018). Social workers can refer the patient to some patient interest groups for peers’ support, designers and engineers can develop tools to aid patients’ daily living, and social enterprises can offer job opportunities to relieve patients’ financial burden. From a macroscopic perspective, policymakers should be able to foresee the upcoming changes in demographic structure and allocate resources to facilitate the prevention and care of chronic diseases. Furthermore, interprofessional collaboration is not only limited to disease management, but is an inevitable element in solving everyday problems, such as poverty, climatic change, pollution, and discrimination (Sutton and Kemp, 2006; Briggs and McElhaney, 2015; Kostoff et al., 2016; Bryant et al., 2017). As the pillars of society, university graduates should demonstrate the competency of sharing their expertise and making a contribution to the team. To achieve such a goal, IPE at university should not be limited to departments within the faculty, but across different faculties.

Previous studies had identified various obstacles that could hinder IPE’s development, including unsupportive attitudes from higher academic administrators, a lack of resources, difficulties or conflicts with class scheduling, different models and methods of practice among disciplines, and stereotypical perceptions of other professions (Buring et al., 2009; Hughes et al., 2019; Ahmady et al., 2020). IPE development faced a lot of challenges and many published studies involved only two disciplines (Zwarenstein et al., 2005). Our survey findings echoed the hurdles mentioned in the studies, in which the major barriers reported by teachers were the heavy workload, inadequate administrative and financial support, and conflicts with class scheduling.

We would like to share our experience of promoting IPE in the university and how we overcame the challenges in the process. In the 2017/2018 school year, we initiated a new course titled “Inter-professional Learning for Medication Safety.” This credit-bearing course welcomed students majoring in Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy, Public Health, Chinese Medicine, Gerontology, Community Health Practice, and Biomedical Sciences. This course aimed to help students recognize their own role in a multidisciplinary team to enhance medication safety among the elderly. Learning activities included a lecture on IPE and common drug-related problems in geriatrics, discussion on patient care plans among students across disciplines, and team-based service-learning in elderly care centers. In view of students’ concerns about study workload and conflicts with class schedule, we made it an elective course in the summer semester. We employed the validated tool, Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS), to assess the changes in students’ attitudes and perceptions of interprofessional learning and change (Parsell and Bligh, 1999; Reid et al., 2006; National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education, 2013). RIPLS was a 19-item tool with a five-point scale. The overall possible maximum score was 95 and the minimum was 19. Higher mean scores represented a more positive attitude toward interprofessional learning. The questions could be classified into four subscales: teamwork and collaboration, negative professional identity, positive professional identity, and roles and responsibilities. In the 2017/2018 school year, students’ RIPLS scores increased from 74.43 ± 8.04 at baseline to 77.56 ± 10.58 after completing the course. Initially, the course was taught by teaching staff from the School of Pharmacy only. Based on the observation and feedback gathered in the first 2 years, we invited a teacher from the Department of Medicine and Therapeutics and a teacher from the School of Nursing as collaborating partners in the third year. They provided recommendations on the patient care plans from the perspective of their own professions. Starting from the 2020/2021 school year, we will expand the enrolment criteria to include students majoring in Social Work and invite a teacher from the Department of Social Work as a collaborator. Given their close relationship with clients, we believe social workers are in a good position to recognize medication non-adherence problems and enhance medication safety in the elderly population. With the new arrangement, we believe students from the Faculty of Medicine and the Department of Social Work will benefit from each other.

Based on our experience, we would like to propose a few suggestions to overcome the obstacles with IPE. First, IPE programs could begin with selected disciplines within one faculty, then expand to involve more students from different faculties. In our case, we started our program within the Faculty of Medicine with the medical, nursing, and pharmacy disciplines. Our survey results showed that most students had inadequate knowledge of IPE, indicating that IPE was a novel concept in our institution. It is expected that both teachers and students take time to get used to studying and collaborating with their counterparts from other majors. Second, strategies should be developed to overcome the problems with academic schedules and calendars. Implementing the IPE course in the summer semester would allow higher flexibility for teachers and students, as they normally have a lighter workload during the summer term. Besides, it would be beneficial for teachers to introduce basic concepts through asynchronous modules or e-learning modules. Students can view the materials on their own so that they can spend the majority of the class time working with each other. It also allows students from different disciplines to attain a similar level of background knowledge which would facilitate discussion and collaboration (Shaw-Battista et al., 2015). Third, technical support from the institutional level should be provided to teachers. IPE requires collaboration between teachers from different disciplines. Thus, administrative and financial supports are needed for the effective organization of teaching activities and allocation of human resources (Nagge et al., 2017; Shagrir, 2017). It would be beneficial to set up a centralized system for lining up resources. At CUHK, we have the teaching development grant funded by the University Grant Commission to support IPE development. The system should allow teachers to look for potential collaborating partners from other disciplines to facilitate IPE. In addition, training should be provided to teachers to improve curriculum design and enhance students’ learning outcomes. Fourth, the outcomes and impacts of IPE should be evaluated from time to time. Suitable tools should be adopted to assess learning outcomes and competencies, such as professional knowledge, practical skill, interpersonal skill, and communication skill. Teachers’ and students’ comments would be valuable in guiding the development of this new pedagogy.

In summary, the survey findings indicated that despite the positive attitude of university teachers and students toward IPE, barriers could hinder the development of IPE including both personal and institutional levels. The survey results opposed the belief that IPE was a basic and fundamental concept that all students should have already known. Further actions should be taken to address these barriers to executing IPE successfully. These actions may include centralized support and platforms for the support of IPE at the university level. Interfaculty committees should be considered to facilitate the discussions for the IPE development.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The study has been approved by the Survey and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Reference number: SBRE-19-501. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JL analyzed data and wrote the article. JC, SW, AL, WC, PY, YY, FK, FS, and IK supervised the study, provided expert opinion on the study design, and helped with subject recruitment. VL supervised the study and critically reviewed the article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was funded by a Teaching Development and Language Enhancement Grant for the 2019–2022 Triennium from The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahmady, S., Mirmoghtadaie, Z., and Rasouli, D. (2020). Challenges to the implementation of interprofessional education in health profession education in Iran. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 11, 227–236. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S236645

Barr, H., Koppel, I., Reeves, S., Hammick, M., and Freeth, D. (2005). Effective Interprofessional Education: Argument, Assumption and Evidence. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing. doi: 10.1002/9780470776445

Berger-Estilita, J., Fuchs, A., Hahn, M., Chiang, H., and Greif, R. (2020). Attitudes towards interprofessional education in the medical curriculum: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Med. Educ. 20:254. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02176-4

Briggs, M. C., and McElhaney, J. E. (2015). Frailty and interprofessional collaboration. Interdiscip. Top. Gerontol. Geriatr. 41, 121–136. doi: 10.1159/000381204

Bryant, L. H., Freeman, S. B., Daly, A., Liou, Y.-H., and Branon, S. (2017). Making sense: unleashing social capital in interdisciplinary teams. J. Prof. Cap. Commun. 2, 118–133. doi: 10.1108/JPCC-01-2017-0001

Buring, S. M., Bhushan, A., Broeseker, A., Conway, S., Duncan-Hewitt, W., Hansen, L., et al. (2009). Interprofessional education: definitions, student competencies, and guidelines for implementation. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 73:59. doi: 10.5688/aj730459

Burmeister, J. W., Tracey, M. W., Kacin, S. E., Dominello, M. M., and Joiner, M. C. (2018). Improving research in radiation oncology through interdisciplinary collaboration. Radiat. Res. 190, 1–4. doi: 10.1667/RR15023.1

Darlow, B., Coleman, K., McKinlay, E., Donovan, S., Beckingsale, L., Gray, B., et al. (2018). The positive impact of interprofessional education: a controlled trail to evaluate a programme for health professional students. BMC Med. Educ. 15:98. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0385-3

Diane, R. B., Davidson, R. A., Odegard, P. S., Maki, I. V., and Tomkowiak, J. (2011). Interprofessional collaboration: three best practice models of interprofessional education. Med. Educ. Online. 16:1. doi: 10.3402/meo.v16i0.6035

Gabrielová, J., and Veleminsky, M. Sr. (2014). Interdisciplinary collaboration between medical and non-medical professions in health and social care. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 35, 59–66.

Gardner, S. F., Chamberlin, G. D., Heestand, D. E., and Stowe, C. D. (2002). Interdisciplinary didactic instruction at academic health centers in United States: attitudes and barriers. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 7, 179–190. doi: 10.1023/A:1021144215376

Goring, S. J., Weathers, K. C., Dodds, W. K., Soranno, P. A., Sweet, L. C., Cheruvelil, K. S., et al. (2014). Improving the culture of interdisciplinary collaboration in ecology by expanding measures of success. Front. Ecol. Environ. 12:39–47. doi: 10.1890/120370

Green, B. N., and Johnson, C. D. (2015). Interprofessional collaboration in research, education, and clinical practice: working together for a better future. J. Chiropr. Educ. 29, 1–10. doi: 10.7899/JCE-14-36

Greiner, A. C., Knebel, E., and Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Health Professions Education Summit (2003). Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2004.tb00473.x

Haugland, M., Brenna, S. J., and Aanes, M. M. (2019). Interprofessional education as a contributor to professional and interprofessional identities. J. Interprof. Care 1–7. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2019.1693354

Hughes, J. K., Allen, A., McLane, T., Stewart, J. L., Heboyan, V., and Leo, G. (2019). Interprofessional education among occupational therapy programs: faculty perceptions of challenges and opportunities. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 73, 7301345010p1–7301345010p6. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2019.030304

Interprofessional Education Collaborative (2016). Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice, 2016 Updates. Available online at: https://www.ipecollaborative.org/assets/2016-Update.pdf (accessed April 1, 2022).

Interprofessional Education Collaborative (2022). IPEC Core Competencies Revision 2021-2023. Available online at: https://www.ipecollaborative.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=70:2021-2023-core-competencies-revision&catid=20:site-content&Itemid=158 (accessed April 1, 2022).

Kostoff, M., Burkhardt, C., Winter, A., and Shrader, S. (2016). An interprofessional simulation using the SBAR communication tool. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 80:157. doi: 10.5688/ajpe809157

Lawlis, T. R., Anson, J., and Greenfield, D. (2014). Barriers and enablers that influence sustainable interprofessional education: a literature review. J. Interprof. Care 28, 305–310. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2014.895977

Memarpour, M., Fard, A. P., and Ghasemi, R. (2015). Evaluation of attitude to, knowledge of and barriers toward research among medical science students. Asia Pac. Fam. Med. 14:1. doi: 10.1186/s12930-015-0019-2

Nagge, J. J., Lee-Poy, M. F., and Richard, C. L. (2017). Evaluation of a unique interprofessional education program involving medical and pharmacy students. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 81:6140. doi: 10.5688/ajpe6140

National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education (2013). RIPLS: Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale. Available online at: https://nexusipe.org/informing/resource-center/ripls-readiness-interprofessional-learning-scale (accessed October 25, 2019).

O’Daniel, M., and Rosenstein, A. H. (2008). “Professional communication and team collaboration,” in Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses, ed. R. G. Hughes (Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US)).

Parsell, G., and Bligh, J. (1999). The development of a questionnaire to assess the readiness of health care students for interprofessional learning (RIPLS). Med. Educ. 33, 95–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00298.x

Ponte, P. R., Gross, A. H., Milliman-Richard, Y. J., and Lacey, K. (2010). Interdisciplinary teamwork and collaboration: an essential element of a positive practice environment. Annu. Rev. Nurs. Res. 28, 159–189. doi: 10.1891/0739-6686.28.159

Reid, R., Bruce, D., Allstaff, K., and McLernon, D. (2006). Validating the readiness for interprofessional learning scale (RIPLS) in the postgraduate context: are health care professionals ready for IPL? Med. Educ. 40, 415–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02442.x

Shagrir, L. (2017). Collaborating with colleagues for the sake of academic and professional development in higher education. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 22, 331–342. doi: 10.1080/1360144X.2017.1359180

Shaw-Battista, J., Young-Lin, N., Bearman, S., Dau, K., and Vargas, J. (2015). Interprofessional obstetric ultrasound education: successful development of online learning modules; case-based seminars; and skills labs for registered and advanced practice nurses, midwives, physicians, and trainees. J. Midwifery Womens Health 60, 727–734. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12395

Smith, M., Saunders, R., Stuckhardt, L., and McGinnis, J. M., and Committee on the Learning Health Care System in America, Institute of Medicine (2013). Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US).

Solberg, L. B., Solberg, L. M., and Carter, C. S. (2015). Geriatric care boot cAMP: an interprofessional education program for healthcare professionals. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 63, 997–1001. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13394

Styron, R. A. (2013). Interdisciplinary education: a reflection of the real world. Syst. Cybern. Inf. 11, 47–52.

Sutton, S. E., and Kemp, S. P. (2006). Integrating social science and design inquiry through interdisciplinary design Charrettes: an approach to participatory community problem solving. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 38, 125–139. doi: 10.1007/s10464-006-9065-0

Wai, A. K., Lam, V. S., Ng, Z. L., Pang, M. T., Tsang, V. W., Lee, J. J., et al. (2020). Exploring the role of simulation to foster interprofessional teamwork among medical and nursing students: a mixed-method pilot investigation in Hong Kong. J. Interprof. Care 35, 890–898. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2020.1831451

Walsh, W. B., Smith, G. L., and London, M. (1975). Developing an interface between engineering and the social sciences: an interdisciplinary team approach to solving societal problems. Am. Psychol. 30, 1067–1071. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.30.11.1067

Wang, J. M., and Zorek, J. A. (2016). Deliberate practiece as a theoretical framework for interprofessional experiential education. Front. Pharmacol. 7:188. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00188

World Health Organization (2010). Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education & Collaborative Practice. Geneva: World Health Organization, 14–19.

Keywords: Interprofessional Education, pedagogy, collaborative learning, experiential learning, service-learning

Citation: Li JTS, Chau JPC, Wong SYS, Lau ASN, Chan WCH, Yip PPS, Yang Y, Ku FKT, Sze FYB, King IKC and Lee VWY (2022) Interprofessional education—situations of a university in Hong Kong and major hurdles to teachers and students. Front. Educ. 7:653738. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.653738

Received: 15 January 2021; Accepted: 29 June 2022;

Published: 29 July 2022.

Edited by:

Stella L. Smith, Prairie View A&M University, United StatesReviewed by:

Fred Ganotice, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaAna Mercedes Vernia-Carrasco, University of Jaume I, Spain

Pedro Ribeiro Mucharreira, University of Lisbon, Portugal

Valentina Guerrini, University of Florence, Italy

Natalia Gomes, Instituto Politécnico da Guarda, Portugal

Copyright © 2022 Li, Chau, Wong, Lau, Chan, Yip, Yang, Ku, Sze, King and Lee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vivian W. Y. Lee, dml2aWFubGVlQGN1aGsuZWR1Lmhr

Joyce T. S. Li

Joyce T. S. Li Janita P. C. Chau

Janita P. C. Chau Samuel Y. S Wong

Samuel Y. S Wong Ann S. N. Lau

Ann S. N. Lau Wallace C. H. Chan5

Wallace C. H. Chan5 Yijian Yang

Yijian Yang Fred K. T. Ku

Fred K. T. Ku Vivian W. Y. Lee

Vivian W. Y. Lee