94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Educ., 22 December 2022

Sec. Higher Education

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.1083774

This article is part of the Research TopicStories of Abandonment. A Biographical-Narrative Approach to the Academic Dropout in Andalusian Universities. Multicausal Analysis and Proposals for PreventionView all 13 articles

Dropout is a phenomenon that is unfortunately occurring worldwide and is of increasing concern to authorities. It is a reality that quality indicators in many models are affected by the number of students who drop out of school at higher levels. However, this is not only reflected at the educational level, but also affects the social and personal development of young people. The analysis of school dropout among young Spaniards is a topic of interest due to the repercussions it generates in social, personal, and institutional spheres. The objectives of this study were to analyse how many studies have been published on the subject since 2010, locating the selected articles in areas of knowledge and studying the institutions where the research has been carried out. On the other hand, it has been observed how many studies have been focused on the search for the reasons that lead to high dropout rates and the main factors. Finally, an attempt has been made to analyse how many of them are aimed at solving the problem and preventing early school leaving in primary education in order to avoid drop-out at higher levels, by examining the proposals established to reduce the problem. In order to achieve the proposed objectives, a systematic review was carried out with the aim of carrying out a rigorous analysis of the existing and relevant scientific literature on the subject. After applying various exclusion and inclusion criteria, eliminating duplicate records and analysing the works in depth, 28 articles were selected. The results suggest that, currently, despite the problems caused by early school leaving, it is not a subject that has been widely studied and that the main causes are due to educational and social reasons. In the same context, of the articles selected, only 12 present different proposals for the prevention of early school leaving. In the light of the above, it is necessary to look more deeply into the nature of early school leaving in Spanish institutions.

Providing quality education is one of the main objectives of the Spanish educational system. The current interest in improving the quality of education is the result of a progressive compilation of initiatives, policies, plans and programs dating back to the 1980s (Llorent-Bedmar and Cobano-Delgado, 2018).

The Organic Law for the General Organization of the Educational System of 1990 proposed for the first time the general evaluation of the educational system as a factor favoring the quality of education, establishing a policy for its evaluation. Subsequent education laws retained, expanded, and specified this type of initiative (Tiana-Ferrer, 2018).

In order to evaluate an educational system and quantify the quality of education, it is necessary to select those aspects that characterize it. These elements, which concisely provide relevant information on the education system, will be the indicators that allow the evaluation of its different dimensions, as well as comparison with education systems in other countries (García, 2016). At present, the State System of Education Indicators (SSEI) (MEFP, 2021) establishes 21 indicators grouped into three dimensions: schooling and educational environment, educational financing and educational results.

One of the educational performance indicators used to evaluate the Spanish educational system, collected by the SSEI since its 2004 edition, is the early school dropout rate (MECP, 2004). In the most current edition of 2021, this indicator is defined as the percentage of persons aged 18–24 whose highest level of education is at most the last year of compulsory secondary education and who are not in any form of education or training (MEFP, 2021).

However, in the literature we can find different definitions of the concept of Early School Dropout (ESD), some of which are more specific and depend on the educational system of each country, while others are more general definitions aimed at facilitating international comparisons (Rizo and Hernández, 2019). In general, the difference lies in the age at which school dropout occurs and the minimum educational level attained. It is important to consider the various definitions of school dropout when comparing the rates of this indicator, as well as possible sampling errors.

According to the definition of the Statistical Office of the European Union (Eurostat, 2022), Spain is among the countries with the highest rate of early school dropout compared to the countries participating in the statistical study.

Although the ESD rate has decreased year after year and its trend is to continue decreasing, the data collected in 2021 show an 11.4% ESD rate. Spain is three points above the European Union average (8.4%) and does not exceed the European target of keeping the rate below 10%.

On the other hand, analyzing the latest data provided by the SSEI for 2020, the ESD rate has been decreasing to reach 16% in 2020. The rate is still above the European Union average of 9.9% and remains far from the European target of 10% for the year.

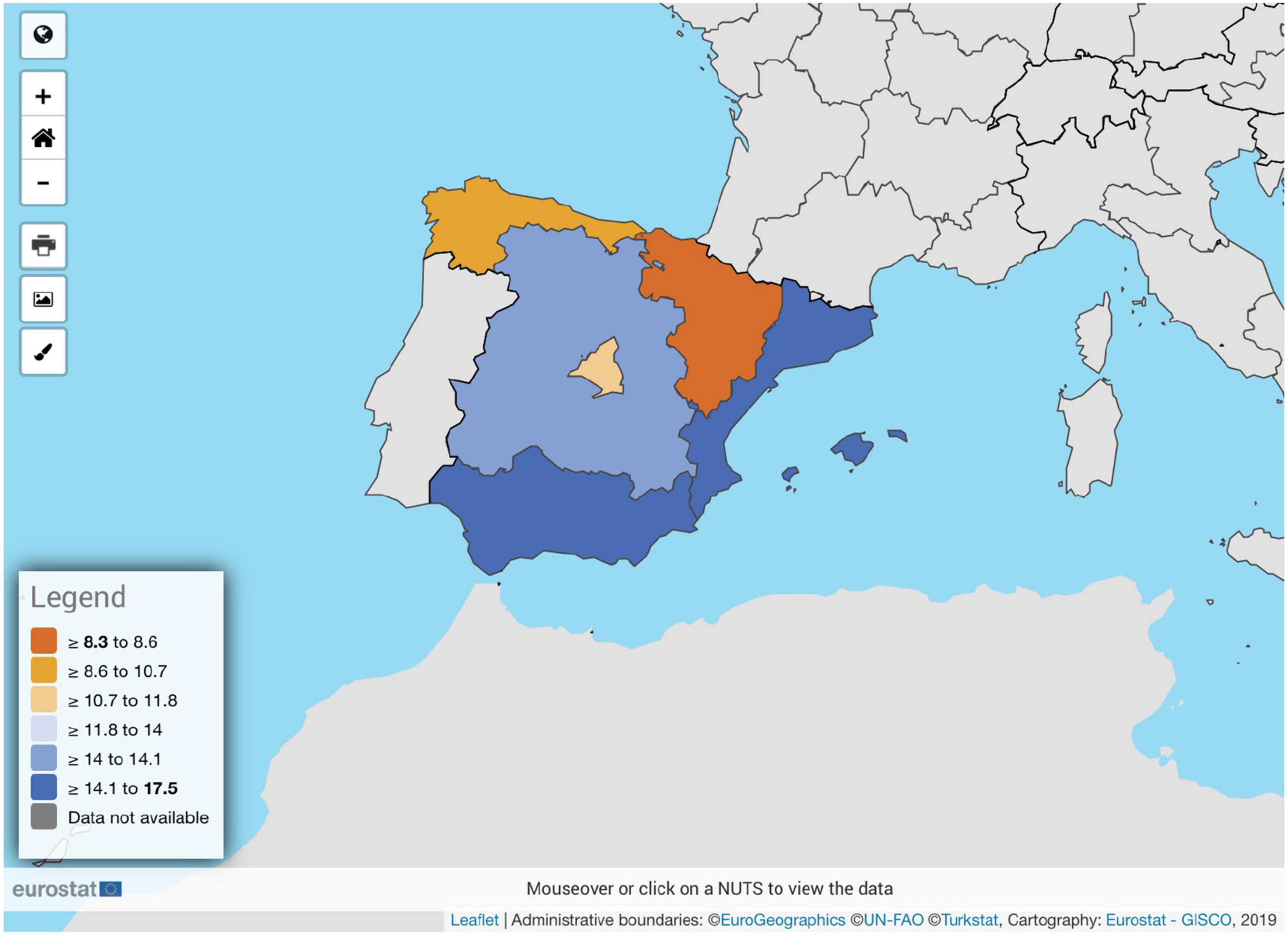

Both Eurostat and the SSEI offer data collected by region, which show that early school dropout is not distributed homogeneously throughout Spain. Analyzing the data by region, Figure 1 shows the high rates of ESD in most of Spain (Eurostat, 2022).

Figure 1. Early school dropout in Spain by region (Eurostat, 2022).

Similarly, analyzing the data provided by the SSEI, in 2020, the regions with the lowest dropout rate (less than 9.1%) are País Vasco, Principado de Asturias and Cantabria. Comunidad de Madrid, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, Galicia, Aragón, and La Rioja have values between 10 and 15% and Ceuta, Melilla, Andalucía, and Illes Balears exceed 21% ESD (MEFP, 2021).

After observing Spain’s position in the European rankings and the heterogeneity of the figures that appear in the different regions of the country, it makes sense to consider which agents influence the processes of early school dropout and what could be the possible actions to improve this situation.

Early school dropout is a problem influenced by many factors and with very diverse origins. The individual’s motivation, personal effort, capabilities, or socio-family support are internal causes that affect ESD (Hernández and Alcaraz, 2018). From an external perspective, the causes that intervene in this phenomenon may be the social environment, gender, ethnicity, nationality, economic situation, or school context, among others (Romero and Hernández, 2019).

The treatment of ESD is a complex challenge that must consider many dimensions in order to carry out multidisciplinary intervention programs from a global and integral perspective (González-Rodríguez et al., 2019). The main actions carried out by different countries include increasing the flexibility and permeability of educational pathways, improving educational and vocational guidance, improving teacher training for diversity, creating positive learning environments, and promoting inclusion (Eurydice, 2014).

In light of the theoretical contributions analyzed in this research, the objective is to analyze the studies that deal with school dropout in Spain. Determining the causes or reasons that lead to it and the most recommended actions that can be carried out to prevent it from occurring, thus reducing the high percentage that is registered in Spain.

The research questions that, together with this main objective, guide the present study are the following:

RQ1: How many studies have been published since 2010 on this topic?

RQ2: In what areas of knowledge are the studies on this subject framed?

RQ3: Which institutions have developed this research on school dropout in Spain?

RQ4: How many studies have focused on the reasons for the high dropout rates in Spain? What are the main factors that lead to this?

RQ5: How many studies are specifically aimed at preventing and solving this problem? What do they propose to reduce school dropout rates?

Finally, an attempt has been made to analyse how many of them are aimed at solving the problem and preventing early school leaving in primary education in order to avoid it at the higher levels, examining the proposals put in place to reduce the problem.

The review process was carried out in two phases: the first was devoted to planning and the second to action (Ramos-Navas-Parejo et al., 2020; Romero-Rodríguez et al., 2020). During the planning stage, the research objectives and questions were defined, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were selected based on the intention of this work, the most appropriate descriptors were chosen, which were found within Eric’s thesaurus, and the databases where the search for documents would be carried out.

In the action phase, the literature was surveyed and the results were refined in order to extract the most relevant content in accordance with the study criteria and, finally, to represent them.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria, were chosen according to the research objectives and questions and in accordance with the premises of the PRISMA statement (Moher et al., 2009). According to the inclusion criteria, we selected journal articles, documents published from 2010 onward, which had been carried out in Spain and which dealt with the study topic: school dropout in Spain. With respect to the exclusion criteria, non-peer-reviewed documents, literature prior to 2010, not published in Spain and whose study topics did not directly concern school dropout were discarded.

The search strategy was carried out within two of the most important international databases of scientific documents: Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus. The selection criteria were based on the quality of the articles indexed in them and their broad scope.

The most appropriate descriptors were selected to define the purpose of this study, which were checked to ensure that they were indexed in Eric’s thesaurus, in order to ensure the use of the most frequent keywords in scientific language. After this operation, we proceeded to carry out different search equations (Tables 1, 2). For these, the Boolean operator “and” was used and it was established that the descriptors were found in the title of the document, abstract or formed part of the keywords.

Data collection was guided by the PRISMA protocol. Thus, the discrimination was carried out in four stages (Figure 2): the first, called identification, consisted of all the documents collected in both databases by performing the search equation represented in the previous tables (Tables 1, 2), a second stage, called selection, in which repeated documents and those identified with the exclusion criteria EX1 and EX2, were eliminated, a third stage, called suitability, in which the articles were analyzed to choose those that respond to the research objectives and questions, which are those that correspond to the inclusion criteria IN3 and IN4, reaching the last stage, called inclusion, in which all the articles that finally make up the research sample are compiled. This process was carried out during the month of September 2022.

Of the 83 publications found according to the search criteria, 28 articles were selected after refining the results according to the established inclusion and exclusion criteria.

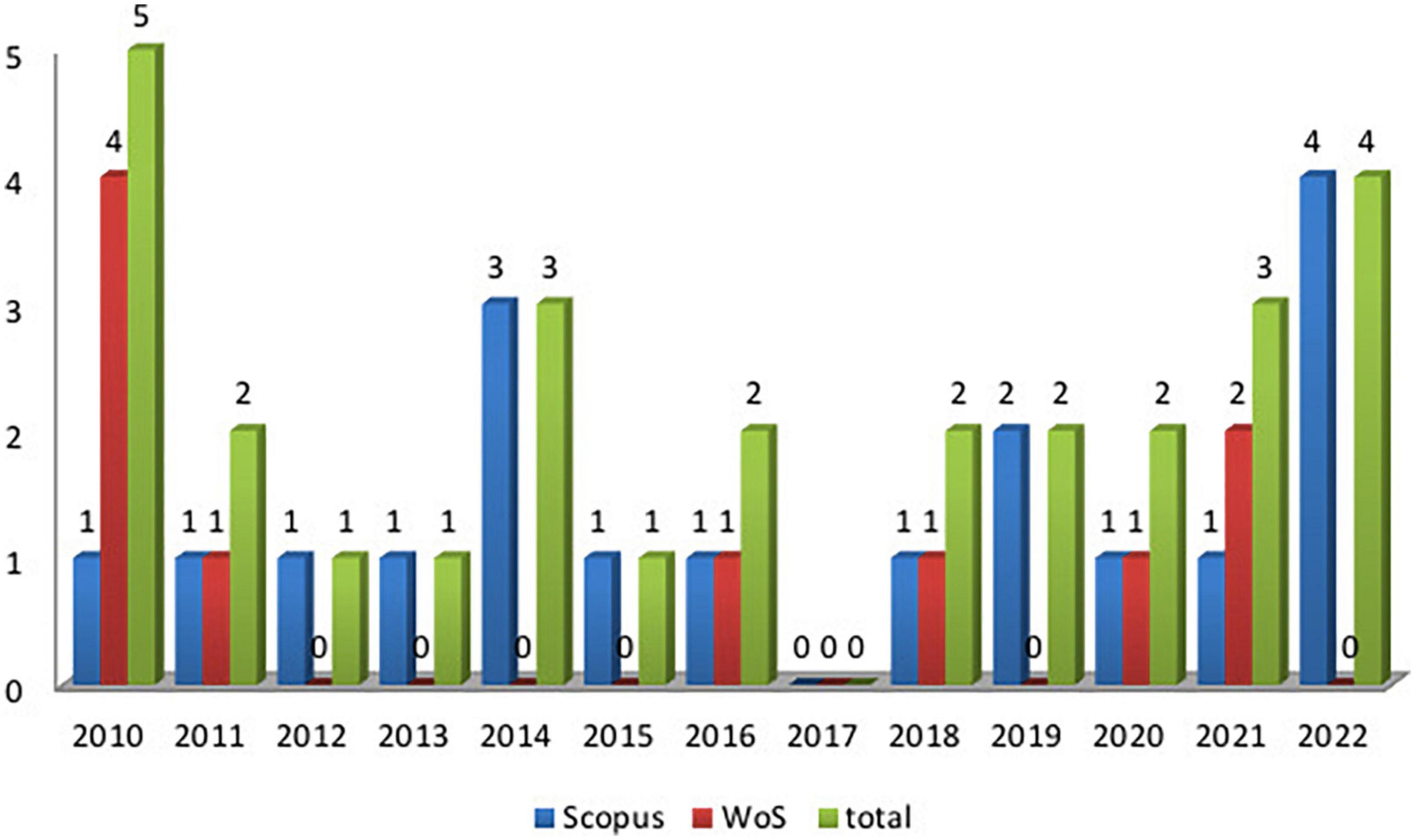

The Scopus database records a total of 18 articles, representing 64.28%, and WoS records 10 papers, representing 35.71%. The main years of scientific production are 2010 with five articles (17.85%) and 2022 with 4 (14.28%). They are followed by the years 2014 and 2021, which each support three articles (10.71%), respectively. The third place is occupied by the years 2011, 2016, 2018, 2019, and 2020 with two articles each year, which represents 7.14% of the total. Finally, in the following years, scientific production is limited to one article (3.57%) per year: 2011, 2012, 2013, and 2015.

On the other hand, it is observed that in 2017 there are no publications in both databases, as well as in the time interval from 2012 to 2015 in the WoS database. The same situation occurs in 2019 and 2022.

The 28 selected articles are grouped into six areas of knowledge and research according to the order of each database of journals and published articles. Both the Psychology and Social Sciences areas coincide in both classifications and appear as independent areas.

In WoS the journals and articles are sorted into 15 different possible Research Areas. The selected publications belonging to this database are distributed in three areas: Education Educational Research with seven papers, Social Sciences with two, and Psychology with one article.

On the other hand, in Scopus the journals and articles are organized into 14 Subject Areas. Those found in this database are presented in the following five areas: Arts and Humanities with one paper, Business, Management and Accounting with three, Social Sciences with 12, and Medicine and Psychology with one publication each.

Between the two databases, the area of knowledge and research in the Social Sciences is the one that collects the most articles with a total of 14 (50%), corresponding to the following: Tomás et al. (2012), Mínguez (2013), Salvà-Mut et al. (2014), González-Losada et al. (2015), Martínez et al. (2016), Gil et al. (2019), Lázaro et al. (2020), Fernández-Menor and Latas (2021), López et al. (2021), Cerdà-Navarro et al. (2022), Rodríguez-Izquierdo (2022), Sánchez-Lissen (2022), Mora and Oreopoulos (2011), and Amer (2011). In second place is Education Educational Research with seven articles, in third place Business, Management and Accounting with three, and finally Psychology with two papers.

The different authors belong to a variety of university and research institutions located throughout Spain. In total there are 30 entities spread over 12 autonomous communities and cities. There are also articles with affiliations from foreign universities in Chile (Universidad La Frontera), Colombia (Universidad Central de Bogotá) and Canada (University of Toronto).

Among the affiliations, in addition to university affiliations, other private and public institutions are visible. For example, private institutions include the Fundación de Estudios de Economía Aplicada (FEDEA) in Madrid and “La Caixa” Research in Barcelona. Among the public institutions other than universities, the Instituto de Evaluación del Ministerio de Educación in Madrid and the Colegio de Educación Infantil y de Primaria (CEIP) in Melilla stand out.

Of the 30 affiliations, eight were from universities in Andalusia, representing 26.66%. The universities of Seville and Malaga have two affiliations each. They are followed by the Universidad Pablo de Olavide, the Universidad de Jaén, the Universidad Loyola de Andalucía, and the Universidad de Huelva with one affiliation.

Catalonia is in second place with six affiliations (20%). These are distributed between the University of Barcelona with 2, and “La Caixa” Research, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, and Universidad Autónoma Barcelona with one affiliation each.

They are followed by the communities of Madrid and the Balearic Islands with five each. In the Madrid region, there are two studies by the Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, and three studies distributed between the Fundación de Estudios de Economía Aplicada (FEDEA), the Instituto Evaluación del Ministerio de Educación, and the Universidad de Comillas. Interestingly, the University of the Balearic Islands leads the number of publications compared to the other institutions with five published works.

Figure 3. Articles published in Scopus and WoS databases since 2010 on early school leavers in Spain.

With three studies we find the Community of Castilla y León, with affiliations from the universities of Salamanca, León, and Valladolid. With two works are the communities of Murcia (University of Murcia), Principality of Asturias (University of Oviedo), and the Autonomous City of Melilla (University of Granada Campus Melilla and College of Infant and Primary Education).

Finally, with one published work, the universities of Zaragoza, Valencia, La Rioja, and Vigo are identified.

Twenty-four articles were found out of a total of 28 which address the causes of early school leaving in Spain. Many of them work on the causes and proposals for prevention in a concatenated manner, which is why the same work points to several reasons for dropping out of school. The reasons listed in these studies are: personal, family, educational, social and educational policy reasons.

Social and educational causes are the most frequent with 13 papers each. They are followed by personal (8), family (8) and educational policy (5) reasons. The reasons can be summarized as follows:

- Educational: type of learning offered in educational institutions adapted to the context of the students, absenteeism, school conflicts, poor educational support, low academic performance, grade repetition, deficiencies in teacher training, difficulties in critical subjects such as mathematics or language, low reading comprehension, low participation of the educational community, class size, and student/teacher ratio (Cobo, 2010; Mora et al., 2010; Rico-Martín and Mohamedi-Amaruch, 2014; Salvà-Mut et al., 2014; González-Losada et al., 2015; Fernández-Suárez et al., 2016; Guio et al., 2018; Prados and Rodríguez, 2018; Gil et al., 2019; Lázaro et al., 2020; López et al., 2021; Morentin-Encina, 2021).

- Social: ease of access to the low-skilled labor market such as in the construction and service sectors, neighborhood environments, peer group or friends, frustration with dissonance between degree and success, socially vulnerable environments, labor market conditions, social and economic disadvantages and lack of reciprocity in friendship relationships (Castro, 2010; Cobo, 2010; Tomas and Gómez, 2010; Amer, 2011; Mora and Oreopoulos, 2011; Tomás et al., 2012; Mínguez, 2013; Salvà-Mut et al., 2014; Guio et al., 2018; Prados and Rodríguez, 2018; Lázaro et al., 2020; López et al., 2021; Cerdà-Navarro et al., 2022).

- Personal: lack of student commitment, defiant attitude, irresponsibility, alcohol and drug abuse, learning difficulties, health problems, poor results, wanting to do other courses, lack of social and emotional competences, aversion to study, low involvement and inadequate behavior in the classroom (Cobo, 2010; González-Losada et al., 2015; Fernández-Suárez et al., 2016; Prados and Rodríguez, 2018; Aguilar et al., 2019; Gil et al., 2019; Rueda et al., 2020; Cerdà-Navarro et al., 2022). Familiares: cabeza de familia ausente, entorno socioeconómico, la nacionalidad y la situación laboral de los padres, el compromiso de la familia con la educación de sus hijos y los antecedentes familiares (Cobo, 2010; Tomas and Gómez, 2010; Tomás et al., 2012; Mínguez, 2013; Salvà-Mut et al., 2014; Fernández-Suárez et al., 2016; Prados and Rodríguez, 2018; Gil et al., 2019).

- Political: the way of calculating school dropout (including people involved in non-formal educational activities increases the indicators and decreases if the newly arrived foreign population is excluded); deficient education policies as Spain has the highest dropout rate in Europe, the change in the LOGSE education law by reducing flexibility, the levels of spending on education and the greater problems of the Mediterranean regions compared to those in the north of Spain (Macías et al., 2010; Mora et al., 2010; Felgueroso et al., 2014; Martínez et al., 2016; Guio et al., 2018).

Out of the 28 studies selected, 12 have different proposals for the prevention of early school leaving. In each of them, several proposals of different natures have generally been found. The most recurrent, with seven articles, are those aimed at improving education policy in different aspects: transcending regional and party politics, proposing more inclusive prevention plans, plans aimed at different groups, policies that require the recruitment of qualified staff and greater investment in education (Cobo, 2010; Amer, 2011; Mínguez, 2013; Martínez et al., 2016; Aguilar et al., 2019; Rodríguez-Izquierdo, 2022; Sánchez-Lissen, 2022).

The next prevention measure is related to greater participation of the educational community with five studies (Cobo, 2010; Amer, 2011; Aguilar et al., 2019; Rueda et al., 2020; Fernández-Menor and Latas, 2021). In this sense, the aim is to work on it from the Primary Education stages, where there is a demand to foster a greater sense of belonging to the community from families, students and local communities. This is followed by the early identification of low academic performance and its improvement, which is addressed in four of the selected articles (Aguilar et al., 2019; Lázaro et al., 2020; Sánchez-Lissen, 2022; Usán-Supervía et al., 2022).

Other proposals present in the remaining studies call for: improving teacher training in intercultural education, intervention strategies, and emotional coaching (Aguilar et al., 2019; Gil et al., 2019; Usán-Supervía et al., 2022), promoting curricular diversification and increasing the educational offer, favoring curricular flexibility (Cobo, 2010; Martínez et al., 2016) and promoting vocational training (Cobo, 2010; Rueda et al., 2020).

This systematic review has been carried out following quality standards (Ramírez et al., 2018). This makes the process of reviewing and extracting the literature rigorous. Within this framework, the work carried out provides an interesting overview of the highly relevant issue of school dropout in Spain today, given that one of the objectives of educational institutions is to provide quality education.

The ultimate objective of educational institutions is to provide equal opportunities for the integral development of students, which means that as few students as possible should drop out of the education system, as the opposite would imply failure not only for the student, but also for the education system. In Spain, as mentioned above, the drop-out rates are above the European Union average, and remain far from the European targets set for this year.

Despite being a problem that is present in the Spanish education system, and in reference to the first objective set out, the research work that has been carried out in this respect is considerably insufficient. Although, analysing the graphs obtained, since 2010 there have not been so many studies published until 2022, with a total of just four articles. In line with the above, if we group the articles found by field of knowledge, the data show that, within the field of Social Sciences is where most papers are found with a total of 14 documents, followed by Education Educational Research with seven papers.

The various authors who have carried out research on early school leaving in Spain belong to some 30 affiliations. However, in first place are the eight universities in Andalusia, followed by Catalonia. Andalusia may have a higher number of research studies in this field due to the fact that it is a problem that arises in the autonomous community as it has the highest number of cases of early school leavers in the whole peninsula, with 21.8% according to data from the National Institute of Statistics (Instituto Nacional de Estadística [INE], 2020).

In relation to the many factors and origins that influence school dropout, both educational and social causes are the ones that have the greatest impact on this fact. Analysing the selected articles and as mentioned by Romero and Hernández (2019), absenteeism may be due to the social environment and the type of teaching offered at school, which is sometimes poorly adapted to the context of the students. On the other hand, there are personal factors such as low motivation on the part of the students, causing a lack of commitment and ending with educational dropout (Hernández and Alcaraz, 2018; Rueda et al., 2020).

Within the framework of the above, the most relevant and forward-looking approach is to propose inclusive prevention plans aimed at different groups, as well as policies that invest in education and hire qualified staff. Teachers should be continuously monitored to find out what methodologies they use, whether they adapt effectively to the context in which they work, how they treat their colleagues and students, and whether they provide adequate ongoing training, among other things. To promote learning and avoid school dropout, educational programmes and scholarship schemes can be used to stimulate learning for students with limited resources.

By way of conclusion, the work carried out has shown that dropping out of school is one of the most serious and worrying problems in the Spanish education system. However, in spite of this, there is not enough research into the causes of early school leaving, and there are not enough prevention plans to avoid early school leaving in Spanish institutions.

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

NM-P was responsible for the introduction and literature review. MR-N-P and FL-L for the methodology and results. BB-O for the discussion and conclusions and translation. All team members have been involved in the planning and development of the publication, reading drafts, and suggesting changes. The work has been developed as a team in order to maintain a common thread. All authors contributed to each section of the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Aguilar, P., Lopez-Cobo, I., Cuadrado, F., and Benítez, I. (2019). Social and emotional competences in Spain: A comparative evaluation between Spanish needs and an international framework based on the experiences of researchers, teachers, and policymakers. Front. Psychol. 10:2127. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02127

Amer, J. (2011). Education and tourist society in Balearic Islands: The public education policies to the impact of the economy of tourism services in the dropout. Investig. Turístic. 2, 66–81.

Castro, R. (2010). The effects of credentialism and social expectations on dropping out of school. Rev. Educ. 147–169.

Cerdà-Navarro, A., Quintana-Murci, E., and Salvà-Mut, F. (2022). Reasons for dropping out of intermediate vocational education and training in Spain: The influence of sociodemographic characteristics and academic background. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 1–25. doi: 10.1080/13636820.2022.2049625

Eurostat (2022). Early leavers from education and training by sex and NUTS 1 regions. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tgs00106/default/map?lang=en (accessed October 15, 2022).

Eurydice (2014). La lucha contra el abandono temprano de la educación y la formación en Europa: Estrategias, políticas y medidas. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Felgueroso, F., Gutiérrez-Domènech, M., and Jiménez-Martín, S. (2014). Dropout trends and educational reforms: The role of the LOGSE in Spain. IZA J. Lab. Policy 3, 1–24. doi: 10.1186/2193-9004-3-9

Fernández-Menor, I., and Latas, Á (2021). Notes on the fight against exclusion from the socio-educational community. Rev. Prism. Soc. 33, 183–201.

Fernández-Suárez, A., Herrero, J., Pérez, B., Juarros-Basterretxea, J., and Rodríguez-Díaz, F. (2016). Risk factors for school dropout in a simple of juvenile offenders. Front. Psychol. 7:1993. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01993

García, B. (2016). Indicators of early school desertion: A framework for reflection on strategies for improvement. Perf. Educ. 38, 191–213.

Gil, A., Antelm-Lanzat, A., Cacheiro-González, M., and Pérez-Navío, E. (2019). School dropout factors: A teacher and school manager perspective. Educ. Stud. 45, 756–770. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2018.1516632

González-Losada, S., García- Rodríguez, M., Ruíz- Muñoz, F., and Muñoz- Pichardo, J. (2015). Risk factors of early high school dropout: Andalusia middle school teachers’ perspective. Profesorado 19:4.

González-Rodríguez, D., Vieira, M. J., and Vidal, J. (2019). The perception of primary and secondary school teachers about the variables that influence early school leaving. Rev. Inv. Educ. 37, 181–200. doi: 10.6018/rie.37.1.343751

Guio, J., Choi, Á, and Escardíbul, J. (2018). Labor markets, academic performance and school dropout risk: Evidence for Spain. Int. J. Manpow. 39, 301–318. doi: 10.1108/IJM-08-2016-0158

Hernández, M. A., and Alcaraz, M. (2018). Factores incidentes en el abandono escolar prematuro. Rev. Investig. Educ. 16, 182–195.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística [INE] (2020). Abandono educativo temprano de la población de 18 a 24 años por CCAA y periodo. Available online at: https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Datos.htm?path=/t00/ICV/dim4/l0/&file=41401.px#!tabs-grafico (accessed October 10, 2022).

Lázaro, S., Urosa, B., Mota, R., and Rubio, E. (2020). Primary education truancy and school performance in social exclusion settings: The case of students in Cañada real Galiana. Sustainability 12:8464. doi: 10.3390/su12208464

Llorent-Bedmar, V., and Cobano-Delgado, V. (2018). Spanish educational legislation reforms during the current democratic period: A critical perspective. Arch. Analíticos Polít. Educ. 26, 1–23. doi: 10.14507/epaa.26.2855

López, M., Bernad, I., García, J., Córdoba- Iñesta, A., Urraco, E., Méri, E., et al. (2021). Student engagement in vocational education and training: Differential analysis in the province of Valencia. Rev. Educ. 394, 181–204. doi: 10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2021-394-505

Macías, E., Llorente, R., Pino, F., and Perez, J. (2010). Some arithmetic remarks on school failure and early school dropout in Spain. Rev. Educ. 307–324.

Martínez, M., Reverte, G., and Manzano, M. (2016). School failure in Spain and its regions: Territorial disparities and proposals for improvement. Rev. Estud. Reg. 121–155.

MECP (2004). Sistema estatal de indicadores de la educación. Proyecto 2004. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación Cultura y Deporte. doi: 10.4438/176-04-123-6

MEFP (2021). Sistema estatal de indicadores de la educación. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional.

Mínguez, A. (2013). The early school leaving in Europe: Approaching the explanatory factors. N. Horiz. Educ. 61:50.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., and Altman, D. G. (2009). Elementos de informe preferidos para revisiones sistemáticas y metanálisis: La declaración de PRISMA. Ann. Intern. Med. 151, 264–269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Mora, T., and Oreopoulos, P. (2011). Peer effects on high school aspirations: Evidence from a sample of close and not-so-close friends. Econ. Educ. Rev. 30, 575–581. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.01.004

Mora, T., Escardíbul, J., and Espasa, M. (2010). The effects of regional educational policies on school failure in Spain. Rev. Econ. Aplic. 18, 79–106.

Morentin-Encina, J. (2021). Lost studies, found learning. Analysis of learning from early school leaving. REICE Rev. Iberoam. Cal. Efic. Camb. Educ. 19, 103–120. doi: 10.15366/reice2021.19.3.007

Prados, M., and Rodríguez, M. (2018). Determining factors of early school leaving. Rev. Investig. Educ. 16, 182–195.

Ramírez, G. M., Collazos, C. A., Moreira, F., and Fardoun, H. (2018). Relationship between U-learning, connective learning and the xAPI standard: Systematic review. Campus Virtuales 7, 51–62.

Ramos-Navas-Parejo, M., Cáceres-Reche, M. P., Soler-Costa, R., and Marín-Marín, J. A. (2020). El uso de las TIC para la animación a la lectura en contextos vulnerables: Una revisión sistemática en la última década. Texto Tivre Ling. Tecnol. 13, 240–261. doi: 10.35699/1983-3652.2020.25730

Rico-Martín, A., and Mohamedi-Amaruch, A. (2014). Evaluación de la comprensión lectora en alumnos bilingües mazigio-español al término de la educación primaria. Calidoscópio 12, 49–63. doi: 10.4013/cld.2014.121.06

Rizo, L. J., and Hernández, C. (2019). El fracaso y el abandono escolar prematuro: El gran reto del sistema educativo español. Papeles Salmantinos Educ. 23, 55–81.

Rodríguez-Izquierdo, R. (2022). Identifying factors and inspiring practices for preventing early school leaving in diverse Spain: Teachers’ perspectives. Intercult. Educ. 33, 123–138. doi: 10.1080/14675986.2021.2018191

Romero, E., and Hernández, M. (2019). Analysis of endogenous and exogenous causes of early school dropout: A qualitative research. Education XX1, 22, 263–293. doi: 10.5944/educxx1.21351

Romero-Rodríguez, J. M., Ramírez-Montoya, M. S., Aznar-Díaz, I., and Hinojo-Lucena, F. J. (2020). Social appropriation of knowledge as a key factor for local development and open innovation: A systematic review. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 6:44. doi: 10.3390/joitmc6020044

Rueda, P., Torello, O., and Mut, F. (2020). Educational disengagement profiles: A multidimensional contribution within basic vocational education and training. Rev. Educ. 389, 67–91. doi: 10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2020-389-455

Salvà-Mut, F., Oliver-Trobat, M., and Comas-Forgas, R. (2014). Assessment of reading comprehension of Berber-Spanish bilingual students at the end of primary education. Magis Rev. Int. Investig. Educ. 6, 129–142. doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.M6-13.AEDE

Sánchez-Lissen, E. (2022). Reasons for an educational pact in Spain within the framework of decentralised government administration. Rev. Span. Pedag. 80, 311–330.

Tiana-Ferrer, A. (2018). Thirty years of school evaluation in Spain. Education XX1, 21, 17–36. doi: 10.5944/educxx1.21419

Tomas, A., and Gómez, M. (2010). Determinants of early drop-outs in Spain: A analysis by gender. Rev. Educ. 191–223.

Tomás, A., Solís, J., and Torres, A. (2012). School dropout by gender in the European Union: Evidence from Spain. Estud. Sobre Educ. 23, 117–139. doi: 10.15581/004.23.2052

Keywords: school dropout, Spain, education, systematic review, high education

Citation: Berral-Ortiz B, Ramos-Navas-Parejo M, Lara-Lara F and Moreno-Palma N (2022) School dropouts in Spain: A systematic review. Front. Educ. 7:1083774. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1083774

Received: 29 October 2022; Accepted: 29 November 2022;

Published: 22 December 2022.

Edited by:

Antonio Hernandez Fernandez, University of Jaén, SpainReviewed by:

Juan Leiva-Olivencia, University of Malaga, SpainCopyright © 2022 Berral-Ortiz, Ramos-Navas-Parejo, Lara-Lara and Moreno-Palma. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Blanca Berral-Ortiz, YmxhbmNhYmVycmFsQHVnci5lcw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.