- Department of Special Education, Faculty of Education, Kristianstad University, Kristianstad, Sweden

The present study aims to study how external assessments are used by teachers, transforming summative test results into a formative approach for teaching, with a special focus on students with SEN. The data material consists of documents and interviews with teachers. The documents were the schools’ compilations of assessment results, including proposals for measures and action programs for individual students. The students’ action programs constitute data material for analysis of their needs regarding the outcomes of the DLS tests. Eight ordinary and six SEN teachers participated in follow-up interviews to express their understanding of the test results and their decisions regarding what adaptations and support the students needed. The results show the teachers’ expressions and understanding of aligning the results to better support the identified SEN students in education. The emerging results indicate that the primary purpose of the assessment was to identify students with SEN and to plan teaching for these students. SEN was identified by test results on or below stanine 3. The planned support was mainly directed toward special education conducted by SEN teachers. Within the same community, different interpretations of the assignment are possible. This may affect how the results are analyzed and implemented into teaching.

Introduction

The present study reflects the alignment between an external assessment, initiated from a municipal school administration, and teachers’ use of the results for teaching, especially students with special needs. It is a re-analysis of part of a more extensive study, aimed at contributing with knowledge about teacher’s perceptions of an external assessment assignment and the consequences at organizational, group and individual level. In that study the results show that the main purpose of the assessment is to identifying students with special needs. The results also illuminate the complexity of the assessment assignment and dilemmas the teachers need to handle during the whole assessment process. However, without deepening the alignment between assessment results and teaching, which the present study aims to focus.

Externally initiated assessments are usually classified as high-stakes or low-stakes according to the consequences they may have at different levels. For example, high-stakes assessments may affect the individual student’s further education regarding grades or school placement (Gard, 2020). Low stakes, on the other hand, are not directed at the individual student; instead, they can be considered high stakes at the system, school, or educational level (Polesel et al., 2014).

Rather than referring to an assessment as summative or formative, Black and Wiliam (2018) argue that an assessment serves either a summative or formative purpose. Assessment with a formative purpose focuses on the student’s process during a work in progress. The information collected is intended to support both the student and the teacher. The teacher can use the information to adapt ongoing teaching. The student can be informed about what may need to change for progress towards the objectives to take place (Council of Chief State School Officers, 2018). Assessment with a summative purpose is used at the end of a theme or at the end of a term to measure students’ learning at a particular time. It may be in the form of test results or grades (Dolin et al., 2018). The information from an assessment with a summative purpose can provide information to both teacher and student. It can be about something in the teaching that can be changed or something the student can change. An assessment with a summative purpose can therefore be used formatively for both teachers and students (Wiliam, 2006; Black and Wiliam, 2018).

According to Lockton et al. (2020), external assessments based on standardized assessments can serve both summative and formative purposes for education. When external assessments are used for evaluative purposes, they are considered summative. Formative purposes mean that assessments are used to inform adjustments in teaching and learning (Lockton et al., 2020). Research indicates that teachers value self-assessments more highly than external assessments and are sceptical of using data from external assessments for formative purposes related to teaching and learning (Coburn and Turner, 2011; Vanlommel et al., 2017). This scepticism can be linked to the fact that teachers themselves feel assessed based on the evaluative function of external assessments (Coburn and Turner, 2011). External assessments, used for evaluative purposes are usually recognized by large-scale assessments (Wixson and Carlisle, 2005). Since large-scale assessments are designed without any link to ongoing teaching Wixson and Carlisle (2005) ask whether this type of assessment can or should contribute to improvement of teaching.

External assessments and their impact on teachers and students in the classroom have long been discussed in research and policy fields (Volante et al., 2020). Positive and negative impacts for teachers and students have emerged, although the positive consequences seem limited (Volante, 2012). In previous research, external assessments initiated from international and national assessments are not the focus but the context of this article. Instead, the focus will be on assessment initiated at a local level, on the decision by a municipal school administration to use an externally developed test (DLS). The case was chosen as an example of how an assessment culture, grounded in international assessment assumptions, is transformed through different levels to meet the local level as well as teachers and students in the classroom (Ball, 2003). This assessment culture is recognized using norm-referenced test results to compare and rank schools or individuals (Chapman and Snyder, 2000). The assessment results can also be used to review and evaluate the pedagogical practice, with further expectations to improve the teaching practice (Chapman and Snyder, 2000; Forsberg and Lindberg, 2010; Green, 2013; Gergen and Dixon-Román, 2014; Polesel et al., 2014; Smith and Douglas, 2014). This can be related to the formative purpose of an assessment, in accordance with Lockton et al. (2020). Despite these intentions, research reveals that data from external assessments are rarely analyzed sufficiently to be used as a basis for addressing students’ individual needs in education. An increased number of externally initiated assessments have provided additional opportunities to identify students with special educational needs (SEN; Phelps, 2006; Polesel et al., 2014). Depending on the intentions of identifying students with SEN, the consequences for the students may vary. Discussions are conducted regarding inclusion, exclusion, and categorization rather than relating external assessments to teaching and learning and identifying the need for early support (Allan and Artiles, 2017; Hamre et al., 2018; Mayes and Howell, 2018). To match students’ individual needs in education, The Swedish Schools Inspectorate (2016) emphasizes the importance of identifying students with SEN and identifying the needs of the individual students.

However, research indicates (Christman et al., 2009; Hoover and Abrams, 2013; Resnick and Schantz, 2017; Lockton et al., 2020) that implementing results from external assessments into teaching is a challenging process. To better promote students’ learning, collaborative discussions are suggested as a support for teachers’ analysis. The present study addresses the gap between how external assessments are used by teachers, transforming data from an external assessment, based on a norm-referenced test, to adjustments in teaching and learning, with a special focus on students with SEN.

Previous research

Different epistemological starting points underlie the view of learning, what promotes learning, and how learning can be monitored (Pullin, 2008). With different initiators of assessment of students’ knowledge and skills, the purpose and the forms of assessment may vary. Thus, teachers may conduct assessments that differ from their epistemological starting point for learning (Walker et al., 2014; Baird et al., 2017). Since results from different assessments have become a crucial part of teaching and student learning, it may also mean that teachers are expected to implement results from assessments that differ from the teacher’s view of learning, what promotes learning, and how learning is assessed.

Hoover and Abrams (2013) wanted to study to what extent teachers use summative assessment data from both internal and external assessments in formative ways, meaning to inform adjustments in teaching (Lockton et al., 2020). In total, 656 elementary, middle, and high school teachers participated in a survey conducted in the United States. The results show that teacher-generated assessments were most frequently used compared to other assessment types. The results indicate that analysis from external summative assessments needs to be conducted more frequently to support student learning. The teachers’ analysis was held on a general level, for example, to obtain information about the level of knowledge of the whole class. The results from the study conducted by Hoover and Abrams are consistent with other research, for example, Coburn and Turner (2011) and Vanlommel et al. (2017). In conclusion, Hoover and Abrams (2013) discuss that overall, teachers do not use the advantage of “the formative potential of summative assessment data” (s. 229).

As mentioned in the introduction, collaborative discussions could support teachers in using data from external assessments for formative purposes for the teaching practice. On this basis, Lockton et al. (2020) studied math instructional improvement projects intending to support teachers’ use of data. Teachers from four schools from the same school district in the United States participated in the study. The schools served grades 6–8 and were considered low-performing. Data were gathered for 2½ years. During this period, they conducted 85 interviews with teachers and 150 h of observations of collaborative discussions in teacher teams. Despite the support provided in the improvement project, the results show that the teachers missed the alignment between assessment and education. Rather than support for teaching and learning, the teachers perceived the assessment as serving administrative purposes. According to the teachers, time for preparing and discussing data from assessments was taken from collaboration for lesson planning. This, in turn, affected the students’ learning negatively. The teachers were also pessimistic about letting students from low-performing schools conduct this kind of assessment.

Datnow and Park (2018) discuss how using data from different large-scale assessments to improve teaching and learning can contribute to ensuring equitable opportunities and outcomes for all students. With a starting point from their own studies, Datnow and Park (2018) wanted to discuss how data use practices influence equity goals. From different studies based on in-depth qualitative research, they aimed to study how teachers used data, what types of data, and how these factors influenced education. The aggregated data material consists of observations of teacher team meetings and in-depth classroom interviews in the United States They also reviewed documents related to data use. Overall, the different studies show that the culture and context around assessment affect how data are used and how data will contribute to improving teaching and students’ learning. This is not just about the teachers’ culture. The culture and context at different organizational levels may influence assessment results’ impact on teaching and students’ learning. For complete improvement, several levels in an organization must be involved. It is a matter of developing a common approach within all the relevant levels of an organization. A common approach is not least important concerning students with SEN (Liu and Barrera, 2013; Tefs and Telfer, 2013). In addition to a common framework, the organization can provide collegial collaboration between teachers (Tefs and Telfer, 2013). Lockton et al. (2020) also emphasize school structure and culture as essential factors for implementing test results into education. The results of their study show that the prevailing culture is only sometimes encouraging teachers for the intended purpose. Transforming summative assessment results into teaching and learning places great demands on teachers. According to Gummer and Mandinach (2015), this involves a combination of factors, such as understanding assessment results, subject knowledge, “curricular knowledge, pedagogical content knowledge and an understanding of how children learn” (p. 2). Gummer and Mandinach (2015) summarize this competence with the concept of data literacy, which also includes ethical aspects and handling test results with care.

Benchmark assessment is an example of formative assessment, initiated and administered from district or state level in the United States. Benchmark assessment intends to provide data with purpose to improve teaching (Bartlett, 2021). The formative data are intended to be used at classroom, school, and district level. The assessments are usually administered three times a year and makes it possible for teachers to value students’ progress toward set goals (Hamilton et al., 2009). The information could be a help for teachers in preparing students for summative assessments, carried out at the end-of-year state assessments. Bartlett (2021) wanted to examine teachers use of data from reading benchmark assessments. The assessment intended to effectively improve students reading achievement. In a basic qualitative study, 13 reading teachers, teaching in the third grade participated in semi-structured interviews. Data reflection tools with notes of students’ weakness, strengths, and teachers next steps were available during the interviews. The teachers expressed that they used the formative data to analyze students strengths and weakness and reflected over their teaching. The teachers emphasized the importance of collaboration with other educators during the analyze process. According to the teachers, an effective way to improve the students’ reading abilities was to teach the students different test taking strategies. The teachers also expressed that they used benchmark assessment as model for their own assessments. Assessment of reading comprehension.

The subject for assessment in the present study was reading comprehension, and the Diagnostic Literacy Test (DLS; Lindholm and Tengberg, 2019) was used. Since Swedish students indicated lower results for reading comprehension in The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) from 2000 to 2018 (Skolverket, 2019), the subject could be derived from international assessments. A locally initiated assessment assignment could then contribute to improved teaching and improve the students’ performance (Green, 2013; Polesel et al., 2014; Smith and Douglas, 2014).

Reading comprehension is described as a complex ability consisting of different skills, which is essential to consider when it comes to assessment (Keenan et al., 2008). Although assessment materials related to reading comprehension have been improved, it is difficult to assess all the elements of reading comprehension in one test (Wixson and Carlisle, 2005). Thus, there is a risk that some standardized tests reduce reading ability to a single score (Kamhi and Catts, 2017). Standardized tests could contribute to identifying students with SEN; however, they do not contribute to identifying the needs. Thus, it does not automatically provide support for further education. Instead, Kamhi and Catts (2017) argue that there is a risk that education is adapted to the tests rather than improvement of education.

However, data from different assessments can be included in an overall assessment of a student’s reading comprehension. Together, this can provide a basis for planning and improvement of the teaching practice (Wixson and Carlisle, 2005). Whether the assessment is internal or external, it places demands on how different results can be translated and implemented into teaching, to support all students’ learning and development. For this to be successful, teachers need an increased understanding and knowledge of how to interpret and understand results from different assessments so that they can be integrated into a holistic assessment and help to adapt teaching to students’ different needs (Wixson and Carlisle, 2005).

Aim and research questions

The focus of the present study is the alignment between assessment at the school level initiated from the local level, namely the municipal school administration’s requirement to use the Diagnostic Literacy Test (DLS), and teachers’ use of the results when teaching, especially with SEN students. The present study aims to study how external assessments are used by teachers, transforming data from a norm referenced test, to adjustments in teaching and learning, with a special focus on students with SEN.

Accordingly, two research questions were formulated:

RQ1. How do participating teachers express their alignment between individual results of the DLS test and teaching?

RQ2. What consequences do teachers express that the assessment has for students’ learning and knowledge development, generally and explicitly concerning low-achieving students?

Theoretical framework

The present study is positioned within the theory of situated learning (Lave and Wenger, 1991). In this theory, learning is perceived as a process among participants in a community. Learning is an essential aspect of social practice: the context is vital for the process and comprises the individuals concerned, the activity, and the social world (Lave and Wenger, 1991, p. 122). Participants in communities of practice are “groups of people who share a concern … and learn how to do things better…” (Wenger, 2011, p. 1). Participating individuals have a dual function as members of the activity and as agents of the activity, thereby providing a link between meaning and action. According to Wenger (1998) learning in communities of practice is moving through different phases of development. During these different phases, the participants engagements can differ. Within an organization, communities of practice can have different relationships. In this study the relationship bootlegged, legitimized, and strategic could be relevant. Bootlegged is defined as informal, visible for the participants. The relationship legitimized is “officially sanctioned as a valuable entity” (Wenger, 1998, p. 5). The definition of strategic is “widely recognized as central to the organization’s success (p. 5).

The shared concern in the present study is an assessment assignment initiated and administered by a municipal school administration. Although each school, with participating teachers, can be seen as a community, they all participate in the same assessment assignment, initiated, and organized from a shared context. The assessment material is a norm-referenced standardized test based on psychometric measures. Nevertheless, it is not possible to predict what the results mean for the participants. According to Pullin (2008), the participants’ interpretations “are always situated in social and cultural practices and in individual understandings” (p. 344). Thus, different interpretations of the assignment are possible within the same community. This, in turn, may affect how the results are analyzed and implemented into teaching.

Materials and methods

Description of the case

In the present study, a reanalysis of part of a more extensive study has been conducted, Assessment of reading comprehension, and then what? Teachers’ meaning making in an assessment process initiated from the municipality level (Sjunnesson, 2014; hereafter mentioned as the main study). The main study used a case study approach (Hartley, 2004). As described, the case was designated as an example of what Ball (2003) describes as a transformation of an assessment culture through different levels in society and was considered to respond to the aim of the study. Schools affected by the assessment assignment and the municipal school administration were defined as units characterized by an internal structure in a given context. With a case study approach, it was sufficient to focus on how the teachers handled the situation based on their understanding of the assignment and to study this from different angles (Merriam, 1994; Stake, 1995).

The subject for assessment was reading comprehension, using the DLS test carried out in school year 4. The assignment stated that an analysis of the students’ results was expected to form the basis for planning actions at different levels; individual, group, and organization. These actions should be reported in written form to the municipal school administration. The schools’ accounts should then form the basis for analysis at the municipal level as part of the schools’ quality report, reported to the municipality’s politicians. The assignment also stated that action programs should be established for students with results on or below stanine 3. Thus, the assessment assignment would fulfil different functions at different levels in the organization.

The assessment material was DLS for grades 4–6, sub-exam reading comprehension. DLS has a measured standard and is standardized in three nationally representative norm groups of students in grades 4, 5, and 6.

The research methods

Data were collected using documents (Creswell and Creswell, 2018) and individual semi-structured interviews (Cohen et al., 2011). The documents were chosen to get an increased understanding of the culture of the case (Simons, 2009) and, further, to get an increased awareness of the teachers’ understanding of the external assessment assignment. The following documents were included:

• The assessment assignment formulated at the municipal school administration level.

• The schools’ compilations of assessment results with proposals for measures aimed at the organization, group, and individual level at each school.

• Action programs formulated for individual students with results on stanine 3 or lower.

Since the included documents were formulated as part of the assessment assignment and were not to be part of this study, they were defined as authentic (Cohen et al., 2011). Furthermore, the documents were also authored before the study, and thus were not affected by the researcher.

Interviews with people with different functions within a case provide an opportunity to describe organizational processes. Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted with the teachers involved in the assessment process, meaning classroom teachers and special educational needs teachers (SEN-teacher). Semi-structured interviews were chosen to obtain the teachers’ understanding of the assessment assignment. A given topic characterizes this interview form with open-ended questions (Cohen et al., 2011) formulated in an interview guide. The interview guide was formulated after a first reading of the included documents. The audio recorded interviews lasted between 40 and 50 min. Afterwards they were verbatim transcribed.

The sample

The study was carried out in a municipality located in the south part of Sweden. To create consistency between research issues and the sample, the choice of the municipality was goal-oriented (Bryman, 2018). The municipality was chosen as an example of how an assessment culture is transformed from different levels to meet the local level. Since documents requested from the municipal school administration had been reported from seven of nine schools, these seven schools were included. The schools included in the study represented a socioeconomic dispersion. Three of the schools were in urban areas of the municipality. One of these schools had a high proportion of second language learners. Four schools were in the suburbs of the municipality, with one school located in a rural area. Approximately 230 students from the seven schools conducted the assessment. Action programs were formulated for around 50 of the students. After asking for the parents’ written consent, responses from 31 parents were received, of which 26 parents gave written consent for their children’s action programs to be included in the study. In the main study, two-year action programs were included as data material. In the present study, the first action program, established for each student after the assessment was included as data material. The action programs were evenly distributed throughout the seven participating schools.

Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted with classroom teachers and SEN-teachers. These professionals were involved during the implementation of the assessment and with analysis of the assessment, followed by the drafting of documents requested as part of the assignment. Eight classroom teachers of 12, and six SEN teachers gave their written consent to participate in the study. That not all these 12 teachers participated was in some cases due to the fact that the teachers, on their own initiative, selected a representative from the school to participate in the interview. Teachers from six out of seven schools were represented in the interviews. As the teachers at one school were known to the researcher, the choice was made not to conduct interviews with these teachers. However, documents from this school were included in the study.

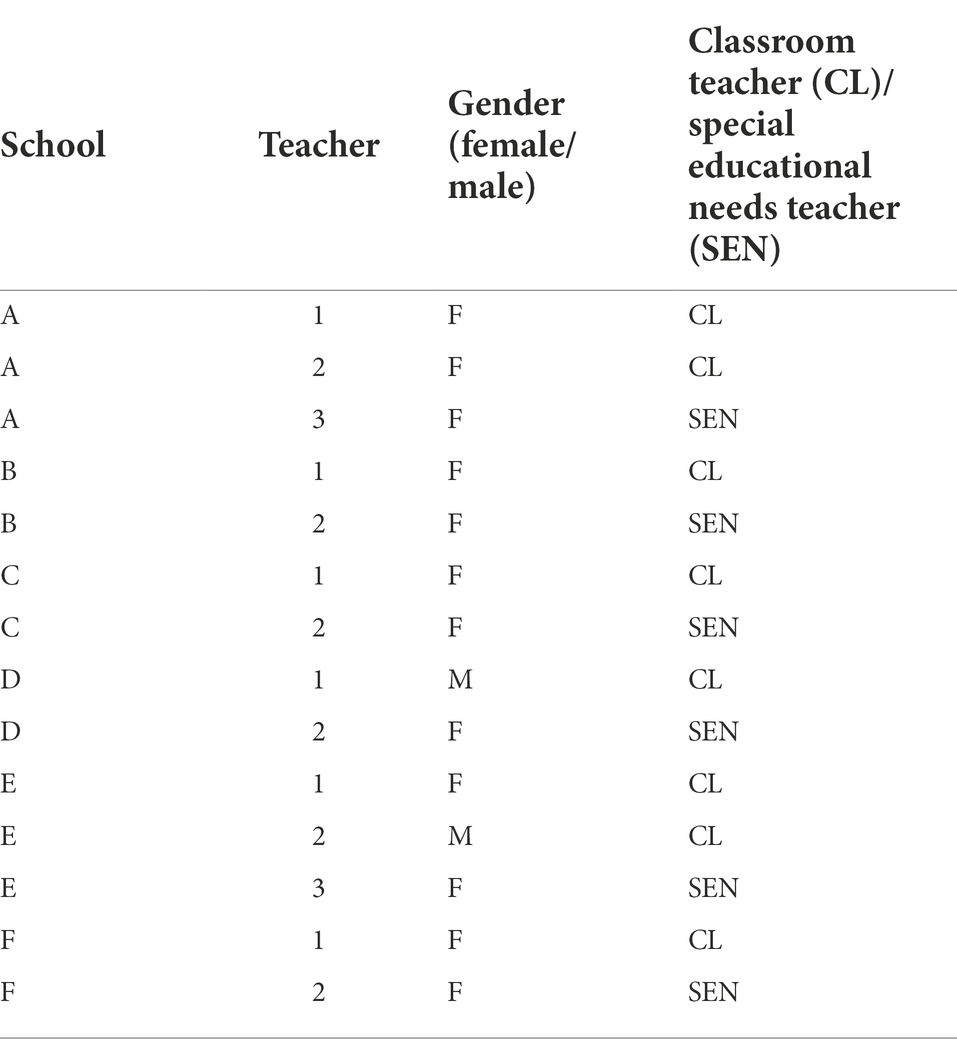

Table 1 lists all participating teacher in relation to school, gender, and category of teacher. When references in the results are made to individual teachers statement, Table 1 can be used to see information of the teacher.

The model for analysis

The analysis in the present study is inspired by thematic analysis presented by Braun and Clarke (2006, 2012). Thematic analysis is described as a method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns [themes] within data (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p. 79). Braun and Clarke (2012) have outlined a 6-phase guide to performing thematic analysis, which supported the analysis process in the present study. Phase 1 is mentioned as data familiarization, meaning to read, and reread the data to get to know the data material. Although Phase 1, was considered fulfilled during the main study, the present study started by re-exposing the case. First the individual data were read, and then the entire data material. Notes were taken. In phase 2, the notes were read, and the coding started. In phases 3, the codes were compared to each other, and sorting in initial themes. During the fourth phase, the work with themes continued and revisions were made. During phase 5, the themes were defined and named, and the first outline of texts for each theme began. In phase 6, the result section was produced. Although the phases are described as a linear process, the analysis work was characterized by a recursive process.

Ethical issues

With ethical issues, this study relied on good research practice (Vetenskapsrådet, 2011). The teachers involved were informed both orally and via an information letter. The parents of the students were informed through an information letter distributed by the teachers. Written consent to participate was obtained from both the teachers and the parents. The written information provided information about the purpose of the study, that the material will only be used for research purposes, that all material will be kept unapproachable to the unauthorized, and that the participation is voluntary. Furthermore, they have the right to withdraw from the study at any time during the study and have confidentiality.

The researcher had access to all the data. The recordings and transcripts were stored on an encrypted external hard disk. After the results are published, the material will be stored according to the rules of Malmö University.

Results

The teachers have different lengths of experience from external assessments initiated at the local level, meaning a municipal school administration. Most teachers (12/14) have extensive experience, some from other municipalities. Their experience indicates that the assessment assignments have changed over time regarding what is assessed, the focus, and the reporting back to the local level. Presenting a written analysis with proposals for action at the individual, group, and organizational levels is described as a relatively new element in this municipality. The current assessment material, DLS, is also described as relatively new in this context. Most teachers (12/14) have experience with similar assessments. Their previous experience indicate that the assessments were aimed at identifying students with special needs. In the past, similar assessments have also been used as a basis for resource allocation in the municipality. It is against this background the results of the present study can be understood.

Collaboration between classroom teachers and SEN teachers during the assessment process

In most schools (5/6), the teachers expressed that the assessment was carried out in collaboration between the classroom teachers and the SEN teachers. This applies to planning the assessment, the implementation of the assessment, and afterwards, in the form of correction and analysis. In some schools, the teachers described this as a clear mandate from the headmaster. At these schools, the overall responsibility was delegated from the headteacher to the SEN teachers. Delegation of responsibility by the principal to SEN teachers is in some schools described based on the SEN teachers’ mission of school development. This could be referred to as a strategic relation (Wenger, 1998). In one school, there was no explicit mandate formulated by the principal. Instead, the teachers were expected to handle the assessment assignment themselves. In this case, the SEN teachers took the overall responsibility. This alternative is explained in terms of the intended purpose of identifying students with SEN; thus, it becomes a special educational issue. A third option, recognized as a legitimized relationship (Wenger, 1998) is when the assignment is given to the teaching team where the SEN teacher is included. In this example, there was no specific person in charge. A further option emerged, when it e appears to be no collaboration between classroom teachers and SEN teachers. Instead, the SEN teacher has assumed responsibility for the whole assessment process. The concerned classroom teachers expressed that they only get feedback from the SEN teacher in the form of assessment results. The teachers’ descriptions reveal different solutions in different schools, suggesting that there is no clear way in which the assessment assignment should be handled in the schools.

Identify improvement needs at different levels

Based on the teacher's expressions, the assessment results can provide information about improvement areas at different levels in the organization. This means, individual students, teaching at group level, the organization at school level, or the organization at municipality level. However, the most central aim, expressed by the teachers, is to identify students with SEN regarding reading comprehension.

Excerpt 1:

It is to find students in special needs, so that we do not miss any students. There are some pupils who are easy to miss, when the decoding is good, but who do not understand what they are reading. (School C, Teacher 2)

Excerpt 2:

Reading comprehension is a bit special. It is easy to identify students who do not decode correctly, because you can hear it when they read. But there are a lot of students who read well, decode correctly, but do not understand what they are reading. (School A, Teacher 3)

Some teachers also express that the aim is to identify improvement areas for teaching, with a special focus on teaching conducted by classroom teachers at the group level.

Excerpt 3:

It is then, I must think. How do I teach? Has it been successful or? I have done this, and the result was this, what do I need to change for the students’ further progress? (School B, Teacher 1)

Excerpt 4:

It may be that you have missed something in the classroom teaching. It does not have to be because the students’ needs. It could be that the student cannot do it, it could be that you simply have not taught, or have not gone through things as you should have done. (School A, Teacher 2)

However, various factors emerge that may defeat the aim to identify improvement areas at group level. For example, some SEN teachers express that classroom teacher can be obstacles.

Excerpt 5:

Then the discussions will not be as deep as I would like class teachers to think about how they can change their teaching. Instead, the discussions are more directed at the students’ circumstances, home situations, and students who do not do their homework. Many teachers lay the analysis outside of themselves. (School B, Teacher 2)

When the class teacher is perceived as an obstacle as in the statement in Excerpt X, it also becomes clear that it is the teaching carried out by the class teacher that needs to be adjusted.

When a SEN-teacher takes full responsibility for the assessment assignment and the focus is directed towards identifying students with special needs, the SEN teacher could be an obstacle to identifying improvement areas for teaching at group level.

Excerpt 6:

So, then she [meaning SEN teacher] takes all the responsibility from the time the test is administered until the marking is completed. So, I get a paper with the results. Yes, it is in the folder there. (School E, Teacher 1)

Teachers also express aims linked to the organizational level for the school or school district and municipality-wide levels. Based on the students’ results, and the schools suggestions for measures, improvement areas can be identified at these levels. For example, if the overall test score in the municipality is low, it may indicate that teaching concerning reading comprehension is an area that needs to be developed. It may also be that one school area stands out from others and that special efforts need to be made there. It is also possible to analyze the reported measures, that is, how individual teachers or schools work with reading comprehension in their teaching. By that, improvement areas can be made visible.

Excerpt 7:

They can also go in and look at the analyses that have been done based on the assessment. How do they work at that school, and how do they not work. (School B, Teacher 2)

At the same time, teachers express that they miss feedback from the municipal school administration back to the schools.

Excerpt 8:

In my role as SEN-teacher at the school, I have not received feedback from the municipality. (School B, Teacher 2)

From three schools (B, C, D), teachers describe how assessment results from DLS, and other external assessments are used as a starting point for collegial discussions at the school level. They describe the headmaster or the school’s development team as the initiator of these discussions. The purpose is to contribute to the improvement of teaching across the school.

Excerpt 9:

We have meetings, between teachers from preschool to Grade 6 and talk about different assessment results. What can we say about the results for different students. But also, what do we need to adjust concerning teaching from preschool up to Grade 6. (School D, Teacher 1)

Excerpt 10:

The headmaster is interested and would like to know about the results. He also participates in the collegial discussions we have the whole school together. (School B, Teacher 1)

From two schools, (A, E) the continued discussions are described as something going on between SEN teachers and the headmaster. This could be a signal to the classroom teachers, that the purpose is to identify students with special needs.

Excerpt 11:

After the assessment, the continued discussions are between the headmaster and SEN-teacher. (School A, Teacher 2)

Excerpt 12:

The headmaster receives information about the results from the SEN-teacher. (School E, Teacher 2)

The significance for teaching

According to the teachers, most students with special needs have already been identified. This means that the students already have received support, documented in individual action programs.

Excerpt 13:

Yes, but what did we say, what did we know, what did we. And already there we are working; we are already in the process with action program and SEN-teacher. (School F, Teacher 1)

Since the most common support offered to the students is special education performed by SEN-teachers, it is not necessary for the classroom teachers planning to let these students undergo the assessment. Some teachers also question if it is ethically correct to let already identified students conduct the test.

Some teachers question the assessment assignment and the use of norm-referenced assessment material. One emerging view can be linked to the relationship between education, learning, and assessment. According to these teachers, norm-referenced assessment material does not support the teacher’s continued teaching. Instead, the assessment merely identifies what teachers already know. To use assessment as a basis for the development of teaching and students’ continued progress, they express that the assessment needs to be designed more in line with the teaching. The current assessment material, DLS, is not seen as a tool for the teachers but more a way to ascertain what the student can or cannot do.

Excerpt 14:

So that, just DLS, you do it, and you can find out if reading comprehension is easy or difficult for a student. But what happens next? It should give something more. Such tests are not good. We need other tools to help the students. (School E, Teacher 2).

Some teachers also question the extent to which one reading comprehension assessment can be used to identify students with SEN and evaluate the teaching. Instead, they express that this assessment needs to be positioned in a broader context alongside other assessments, such as national tests and teachers’ ongoing assessments.

Excerpt 15:

It is not only the tests that determine whether a student has achieved the objectives or not. It must be the whole picture. (School A, Teacher 1)

However, although teachers could notice a discrepancy between students’ results from national tests and this assessment, they express how they follow the directive that students with results at stanine 3 or below should be designated as students with SEN.

Teachers express norm-referenced assessment material as essential.

Excerpt 16:

Yes, I think that standardized tests are kind of accepted tests, so they are. (School A, Teacher 3)

Excerpt 17:

The teachers assessment is more subjective, but these tests, if they are standardized, then it is more obvious how extensive the difficulties are. (School A, Teacher 1)

The teachers’ analysis

The documents consisting of the schools’ compilations of assessment results, reported to the central municipality level, from the different schools generally follow the same structure. Based on the teachers’ overall expressed purpose of the assessment, the document is mainly directed at students with results on the specified criterion, stanine 3 or below. The documents start with a description of the support received by some students during the implementation of the assessment. This is followed by explanations for low performance of students, directed at individual students.

Excerpt 18:

A boy in the class had the text partially read to him because his decoding was not yet fully functional. (School E)

It is difficult for her to read and understand such large amounts of text, so we exempted her from the test. (School F)

The majority of the students have a mother tongue other than Swedish. (School B)

An over-aged boy with a developmental language disorder. (School A)

(Example from the schools’ compilations documents from the different schools)

This is followed by an analysis of the assessment results, with schools highlighting results above stanine 3. This part of the analysis is directed at students, with results between 3 and 9.

Examples of summaries, or analyses, of the results at the group level.

Excerpt 19:

30 students out of 37 (20 girls and 17 boys) had a score equivalent to stanine 4–9. (School D)

We think that the students worked well on their tasks. Overall, we think it was a good result, with 47% of the students scoring at stanine 6–8. (School F)

The results show a spread from 5 to 35 correct answers. Of the girls, 85% are above stanine 3. Of the boys, 70% are above stanine 3. (School G)

(Example from the schools’ compilations documents from the different schools)

Measures at the general level

Overall, the teachers express that the classroom teachers are responsible for the students’ learning at the general level. Sometimes with advice from SEN teachers or that the SEN teachers are involved in some activities in classroom teaching. How the assessment results are handled at each school may form the basis for collegial school-wide discussions. In three schools, the results are described as generating discussions at the school level.

Reading is illuminated as a basis for the development of reading comprehension. The teachers expressed reading both as an already ongoing teaching activity and as a consequence of the assessment. Examples mentioned by the teachers are reading in groups, individual reading, or the teachers reading out loud for the classes. Some teachers used the assessment results as a basis for group division in reading groups. Although reading groups are organized at a general level, SEN teachers can be involved in the classroom, responsible for groups consisting of students with SEN.

Excerpt 20:

The students are divided into different reading groups. Maybe it is not ok to have reading groups based on reading level. But the yellow group is students who think it is difficult to read. There are five or six students and we read a book together and then we discuss the text. (School E, Teacher 3)

Concerning DLS, teachers stress the importance of working with different reading strategies for the students’ further progress related to reading comprehension. The importance of developing students’ word comprehension is also illuminated.

The most common measure described at the general level is the purchase of different teaching materials for reading comprehension. According to teachers, these materials comprise different categories of questions, like those used for reading comprehension in national assessments and tests compared with the DLS.

The results show that the measures presented by the teachers are mainly consistent with how they describe their ongoing teaching. However, they do not discuss how the various measures are used or how to do follow-ups of the students’ progress concerning this measure.

Teachers also express that most measures are directed at students with results at or below stanine 3. For students with results just above stanine 3, there are no specific adjustments in teaching.

Excerpt 21:

Students with extensive difficulties, they are supported by SEN-teacher for a certain hour a week. But for students with average results, there are no measures other than what you do in the ordinary classroom. (School A, Teacher 1)

Measures for students with SEN

Based on the teachers’ expressions, the overall purpose of the assessment assignment is to identify students with SEN. At the same time, the teachers indicate that they already have captured and know most students with SEN. Most of these students already have action programs with planned measures in the form of special education. However, it is not clear how these measures have been followed up in relation of the assessment assignment. When they describe measures at the individual level, they describe what they already have done and what actions they have planned based on the assessment results. For students identified as students with SEN, some teachers express that they do not base their assessment solely on the results of this assessment but that it prompts a further identification of the student’s needs. This further identification is carried out by SEN teachers.

Excerpt 22:

Students with the lowest results have undergone an in-depth diagnosis conducted by the SEN-teacher, followed by modified measures. (School A, Document)

Excerpt 23:

For students with results on stanine 1 further assessments will be used to identify the students needs. (School B, Document)

In the schools’ compilations documents and action programs established for individual students, special education is the most common measure for students with SEN. This support is usually provided outside the classroom, individually, or in small groups. SEN teachers are primarily responsible for special education. The measures are generally described as providing students with SEN, special education for a particular time each week. However, it is not specified what this support should contain, only that it is directed toward reading and reading comprehension.

Excerpt 24:

He receives reading instruction several days a week. (School D)

She receives reading instruction for 20 minutes 2–3 times a week. (School E)

We intend to make a reading group with these pupils and do extra practice. (School C)

(Example from the schools’ compilations documents from the different schools)

In some schools, special education can be related to classroom teaching when the student can be supported with the texts used in different subjects. Additional adjustments are another measure aimed at the individual level but intended to be used at the group level.

Some of the measures can be carried out at home for students who do not have such extensive needs, with the parent taking responsibility.

Overall, the expressed and written measures are more about presenting what to do than relating them to the student’s progress.

Discussions

External assessment and its impact on teachers and students have long been discussed in research and policy fields (Volante et al., 2020). Since almost all teachers in this study have long experience with external assessments, this picture is supported. The present study focused on assessment initiated from the local level, meaning a municipal school administration. The case was chosen as an example of how an assessment culture, grounded in international assessments, is transformed through different levels in society (Ball, 2003).

The picture that emerges from the results is that the primary purpose of the assessment will be to identify students with SEN and to plan teaching for these students. The planned support is mainly directed toward special education outside the classroom conducted by SEN teachers. Through the measures presented, teachers demonstrate that students are supported. However, they do not present the support students receive, based on identified needs. This is consistent with previous research indicating that externally initiated assessments mainly lead to identifying students with SEN but without relating the support to teaching and learning (Allan and Artiles, 2017; Hamre et al., 2018; Mayes and Howell, 2018). The change in the assessment assignment, toward conducting analysis based on the assessment results and using this analysis as a ground for planning and improving teaching, could be seen as an attempt from the municipal school administration to better link the assessment with teaching and students’ learning at group level. However, the results show that this is not having the expected impact as the focus is mainly on students with SEN, without directly linking this to teaching at group level. Although the assessment assignment could be seen as an attempt at a common framework in the municipality (Lockton et al., 2020), an unclear structure around the assessment assignment emerges in the schools. In some schools, the task is delegated to SEN teachers by the headmaster, while in other schools, it is expressed as a separate task among SEN teachers. According to Datnow and Park (2018), the culture and context around assessment affect how data are used and in what way data will contribute to the improvement of teaching and students’ learning. For a complete improvement, Datnow and Park (2018) discuss that several organizational levels must be involved. When the responsibility is solely directed at the teachers, their view of external assessments determines the significance of the assignment. When teachers in a community share a concern (Wenger, 2011), which in this study is the assessment assignment, without support from other participants in the organization, the teachers form their meaning of the assessment assignment based on previous experiences (Lave and Wenger, 1991). According to Pullin (2008), the way participants in a community of practices interpret assessment results is situated in social and cultural practices and in individual understanding. When teachers are solitary in interpreting the assessment task, their understanding is not challenged. Instead, their understanding based on previous experiences seems to gain importance.

Among both classroom teachers and special needs teachers, an intention emerges that the assessment assignment should have a formative purpose to improve teaching at the classroom level. At the same time, obstacles emerges when teachers working in the same communities of practice have different perceptions of the purpose of assessment. In schools where assessment is the basis for collegial discussions related to the topic of reading comprehension, the number of participants sharing the same concern expands. Participation in the collegial discussions provides an opportunity for development among the participants in a community. By participating in this community of practice the learning process can start. The learning will continue and go through different phases (Wenger, 2011). When the organization does not enable or contribute with possibilities to participate in communities around the same concern, individual decisions can be an obstacle for development and for the learning process to start. Although the participants in the latter example share the same concern, it seems that in this assessment assignment they are not part of a common community of practices. Thus the assessment assignment does not contribute to the expected development.

In addition, the fact that special education teachers have or take responsibility for the assessment assignment may also impact the results of the assessment assignment. Based on previous experiences related to special education, this could lead to the focus on identifying students with SEN and that these students become a concern for special education.

An almost one-sided focus on students performing at the specified threshold, stanine 3, reveals a belief that this assessment form represents a truth about students’ reading comprehension abilities. When the assessment does not lead to in-depth discussions about teaching at the group level, it may also affect the learning and knowledge development for students performing over stanine 3. This group is unnoticed when discussions are more about presenting measures, rather than discussing why teaching may need to be improved. This issue could have been discussed if schools had received feedback from other levels of the organization.

Conclusion

This study contributes with examples from a case where an assessment culture based on international assumptions is transformed through the system to the local level. Previous studies have focused more on assessments initiated at international and national levels. The Swedish Schools Inspectorate (2016) emphasizes the importance of identifying students with SEN and their needs. According to Kamhi and Catts (2017), standardized tests do not contribute to identifying SEN students’ needs. For an externally initiated assessment assignment to contribute to the development of teaching, previous research highlights the importance of a common approach at different levels in the organization. In this study, a common approach could involve both the assessment assignment and the approach to special education concerning teaching at the group level.

As consistent with previous research, the results show that the externally initiated assessment assignment mainly lead to identifying students with SEN but without relating the support to teaching and learning (Allan and Artiles, 2017; Hamre et al., 2018; Mayes and Howell, 2018). The measures are primarily directed at the individual student in form of special education, performed by SEN-teacher. It also shows that the assessment does not support the adjustments in teaching to meet the students individual needs, neither at group nor individual level. Modifications are made more generally based on teachers’ previous experience than specifically targeted at each students special needs.

The schools organization has an impact on whether learning in communities of practice contributes with opportunities for a shared learning. Some schools offer and contributes with collegial discussions in expanded communities of practices (Lave and Wenger, 1991). This can be a way to start a process of development towards adjustments for teaching reading comprehension.

Limitations

The studied case has been chosen as an example where an assessment culture based on international assessments has been transformed through the system to the local level. In this case, the local level means municipality level. Using the case study approach, the intention was to present the case as such rather than to generalize the results. The case has been studied from the perspective of the teachers. For further research on similar cases, it would have been interesting to highlight other levels in an organization. This could be representatives from the municipality-wide level or headmasters. These levels are not included in this study, but they appear central in previous research. The students’ perspective could also be an essential contribution to a better understanding of this assessment culture.

The study was conducted in a small municipality with only 14 teachers, distributed among 8 classroom teachers and 6 SEN-teachers. Thus, the results cannot be used to generalize similar assessment assignments in other municipalities. One way to broaden the understanding of the studied phenomenon could be to conduct further studies in other municipalities with similar assessment assignments. And by that, comparisons between different municipalities could be made.

In the present study, a reanalysis of parts of a more extensive study was conducted. The present study takes a point of departure from other and more recent research in relation to the main study. The theory is based on the theory of situated learning which also differs from the theoretical starting point in the main study (Sjunnesson, 2014). This has given that the study provides a new and additional knowledge contribution to the field with a special focus on the alignment between assessment results and teaching, which the present study aims to focus.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participating teachers and by the participating students' legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

HS constructed the design of the study, literature review, data collection, analyses, interpretation, and writing the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Swedish Research Council (grant no. 2017-06039).

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful for funding from the Swedish Research Council (grant no. 2017-06039), and the Graduate School for Special Education (SET). The author extends sincere thanks to supervising professors: Mona Holmqvist at Malmö University (Sweden) and Carin Roos at Kristianstad University (Sweden). Further, the author thanks Spoken (https://www.spokencompany.se/) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Allan, J., and Artiles, A. J. (eds.) (2017). World Yearbook of Education 2017: Assessment Inequalities. Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis.

Baird, J., Andrich, D., Hopfenbeck, T. N., and Stobart, G. (2017). Assessment and learning: fields apart? Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 24, 317–350. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2017.1319337

Ball, S. J. (2003). The teacher's soul and the terrors of performativity. J. Educ. Policy 18, 215–228. doi: 10.1080/0268093022000043065

Bartlett, D. (2021). Teachers’ Use of Third Grade Reading Benchmark Assessment Data. Doctoral dissertation, Walden University.

Black, P., and Wiliam, D. (2018). Classroom assessment and pedagogy. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 25, 551–575. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2018.1441807

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2012). “Thematic analysis,” in APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological. eds. H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, and K. J. Sher (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 57–71.

Bryman, A. (2018). Samhällsvetenskapliga metoder [Social Research Methods]. 3 upplagan. Edn Stockholm: Liber.

Chapman, D. W., and Snyder, C. W. (2000). Can high stakes national testing improve instruction: reexamining conventional wisdom. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 20, 457–474. doi: 10.1016/S0738-0593(00)00020-1

Christman, J. B., Neild, R. C., Bulkley, K., Blanc, S., Liu, R., Mitchell, C., et al. (2009). Making the Most of Interim Assessment Data. Lessons From Philadelphia. Philadelphia: Research for Action.

Coburn, C. E., and Turner, E. O. (2011). Research on data use: a framework and analysis. Measurement (Mahwah, N.J.) 9, 173–206. doi: 10.1080/15366367.2011.626729

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2011). Research Methods in Education (7 Edn.). London: Routledge.

Council of Chief State School Officers (2018). Revising the definition of formative assessment. Available at: https://ccsso.org/sites/default/files/2018-06/Revising%20the%20Definition%20of%20Formative%20Assessment.pdf (Accessed November 24, 2022).

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (5. rev., international student ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Datnow, A., and Park, V. (2018). Opening or closing doors for students? Equity and data use in schools. J. Educ. Chang. 19, 131–152. doi: 10.1007/s10833-018-9323-6

Dolin, J., Black, P., Harlen, W., and Tiberghien, A. (2018). “Exploring relations between formative and summative assessment,” in Transforming Assessment. eds. J. Dolin and R. Evans (Berlin: Springer International Publishing), 53–80.

Forsberg, E., and Lindberg, V. (2010). Svensk forskning om bedömning: en kartläggning. [Swedish Research About Assessment: A Survey]. Sweden: Vetenskapsrådet.

Gard, K. (2020). Students’ attitudes towards standardized testing: A literature review. [Curriculum and Instruction Undergraduate Honors]. University of Arkansas. Thesis Available at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/cieduht/21 (Accessed November 24, 2022).

Gergen, K. J., and Dixon-Román, E. J. (2014). Social epistemology and the pragmatics of assessment. Teach. Coll. Rec. 116, 1–22. doi: 10.1177/016146811411601111

Green, A. (2013). Washback in language assessment. Int. J. Engl. Stud. 13, 39–51. doi: 10.6018/ijes.13.2.185891

Gummer, E. S., and Mandinach, E. B. (2015). Building a conceptual framework for data literacy. Teach. Coll. Rec. 117, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/08957347.2013.793187

Hamilton, L., Halverson, R., Jackson, S. S., Mandinach, E., Supovitz, J., and Wayman, J. (2009). IES practice guide: Using student achievement data to support instructional decision making (NCEE 2009–4067). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance.

Hamre, B., Morin, A., and Ydesen, C. (2018). “Optimizing the educational subject between testing and inclusion in an era of neoliberalism,” in Testing Inclusive Schooling. eds. B. Hamre, A. Morin, and C. Ydesen (London: Routledge), 254–261.

Hartley, J. (2004). “Case study research,” in Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research. eds. C. Cassell and G. Symon (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 323–333.

Hoover, N. R., and Abrams, L. M. (2013). Teachers' instructional use of summative student assessment data. Appl. Meas. Educ. 26, 219–231.

Kamhi, A. G., and Catts, H. W. (2017). Epilogue: Reading comprehension is not a single ability—implications for assessment and instruction. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 48, 104–107.

Keenan, J. M., Betjemann, R. S., and Olson, R. K. (2008). Reading comprehension tests vary in the skills they assess: differential dependence on decoding and Oral comprehension. Sci. Stud. Read. 12, 281–300. doi: 10.1080/10888430802132279

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lindholm, A., and Tengberg, M. (2019). The reading development of Swedish L2 middle school students and its relation to reading strategy use. Read. Psychol. 40, 782–813. doi: 10.1080/02702711.2019.1674432

Liu, K., and Barrera, M. (2013). Providing leadership to meet the needs of ELLs with disabilities. J. Spec. Educ. Leadersh. 26, 31–42.

Lockton, M., Weddle, H., and Datnow, A. (2020). When data don’t drive: teacher agency in data use efforts in low-performing schools. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 31, 243–265. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2019.1647442

Mayes, E., and Howell, A. (2018). The (hidden) injuries of NAPLAN: two standardized test events and the making of 'at risk' student subjects. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 22, 1108–1123. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2017.1415383

Merriam, B. S. (1994). Fallstudien som forskningsmetod [Case Study as Research Method]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Polesel, J., Rice, S., and Dulfer, N. (2014). The impact of high stakes testing on curriculum and pedagogy: a teacher perspective from Australia. J. Educ. Policy 29, 640–657. doi: 10.1080/02680939.2013.865082

Pullin, D. C. (2008). “Assessment, Equity, and Opportunity to Learn,” in Assessment, equity, and opportunity to learn. eds. P. A. Moss, D. C. Pullin, J. P. Gee, E. H. Haertel, and L. J. Young (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 333–351.

Resnick, L. B., and Schantz, F. (2017). Testing, teaching, learning: who is in charge? Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 24, 424–432. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2017.1336988

Sjunnesson, H. (2014). Bedömning av läsförståelse - och sen då?: Pedagogers menings-skapande i en kommunövergripande bedömningsprocess. [Assessment of reading comprehension–and then what?: Teachers mening making in an assessment process initiated from a municipality]. Lic.diss. Lärarutbildningen, Malmö högskola.

Skolverket (2019). PISA 2018: 15-åringars kunskaper i läsförståelse, matematik och naturvetenskap [PISA 2018: 15-year-olds’ Knowledge of Reading Comprehension, Mathematics and Science]. Sweden: Skolverket, Stockholm.

Smith, E., and Douglas, G. (2014). Special educational needs, disability, and school accountability: an international perspective. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 18, 443–458. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2013.788222

Swedish Schools Inspectorate (2016). Skolans arbete med extra anpassningar – Kvalitetsgranskningsrapport [The School’s Work With Supplemental Support–Quality Review Report]. Stockholm: Swedish Schools Inspectorate.

Tefs, M., and Telfer, D. M. (2013). Behind the numbers: redefining leadership to improve outcomes for all students. J. Spec. Educ. Leadersh. 26:43.

Vanlommel, K., Van Gasse, R., Vanhoof, J., and Van Petegem, P. (2017). Teachers' decision-making: data-based or intuition driven? Int. J. Educ. Res. 83, 75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2017.02.013

Vetenskapsrådet (2011). Good Research Practice [Elektronisk resurs], (Reviderad utgåva). Sweden: Vetenskapsrådet.

Volante, L. (Ed.). (2012). School Leadership in the Context of Standards-based Reform: International Perspectives. Berlin: Springer.

Volante, L., DeLuca, C., Adie, L., Baker, E., Harju-Luukkainen, H., Heritage, M., et al. (2020). Synergy and tension between large-scale and classroom assessment: international trends. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 39, 21–29. doi: 10.1111/emip.12382

Walker, V. L., DeSpain, S. N., Thompson, J. R., and Hughes, C. (2014). Assessment and planning in K-12 schools: a social-ecological approach. Grantee Submission 2, 125–139. doi: 10.1352/2326-6988-2.2.125

Wenger, E. (2011). Communities of practice: A brief introduction. Available at: Retrieved from: https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1794/11736/A%20brief%20introduction%20to%20CoP.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (Accessed November 11, 2025).

Wiliam, D. (2006). Formative assessment: getting the focus right. Educ. Assess. 11, 283–289. doi: 10.1080/10627197.2006.9652993

Keywords: external assessment, primary school, reading comprehension, special educational needs, theory of situated learning

Citation: Sjunnesson H (2022) Teachers’ alignment between a local initiated external assessment: The diagnostic literacy test—And teaching regarding special educational needs students’ needs. Front. Educ. 7:1075165. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1075165

Edited by:

Aldo Bazán-Ramírez, National University Federico Villareal, PeruReviewed by:

Karla Andrea Lobos, University of Concepcion, ChileRoberto Chávez-Nava, Instituto Tecnológico de Sonora (ITSON), Mexico

Copyright © 2022 Sjunnesson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Helena Sjunnesson, aGVsZW5hLnNqdW5uZXNzb25AaGtyLnNl

Helena Sjunnesson

Helena Sjunnesson