- Pedagogical Department of Primary Education, University of Thessaly, Volos, Greece

This study deals with written reflections from final-year undergraduate pre-service teachers on the implementation of project-based learning (PjBL) during the school practicum. The research focuses on highlighting undergraduate pre-service teachers’ meaning through reflexive thematic analysis as well as highlighting modes of expressing positions—according to a specific model categorizing these modes—on the implementation of child-centered instructional approaches such as Pj-BL. The research methodology included written reflections by 40 undergraduate student teachers in a 4-year university BA of preparing primary school teachers by applying the convenient sampling strategy. The participants were attending their final school teaching practice component of their studies. The study identifies prospective teachers’ positive points, concerns, and challenges when applying Pj-BL. The findings also indicate that prospective teachers need to further develop their reflective thinking skills to provide explanations and solutions and identify areas of personal improvement when they produce written reflective reports.

Introduction

Developing prospective teachers’ reflective thinking is regarded as an important skill for becoming an effective teacher. Through different reflective practice strategies, pre-service teachers (PSTs) can recognize pedagogical issues such as teaching and learning processes, classroom management, communication procedures, and the teacher’s role. In addition, they can define their professional identity as educators in order to develop their professional capabilities (Zeichner, 2006; Orland-Barak and Yinoh, 2007; Brookfield, 2017; Cubero-Pérez et al., 2019). Therefore, undergraduate and postgraduate programs related to teacher preparation should incorporate various forms of reflective practice (Calderhead and Gates, 1993, 2003). Engaging in reflection helps prospective teachers take their “first steps” during school to connect knowledge with experience and theory with practice. In addition, PSTs are able to recognize pedagogical issues and build a professional identity as an educator, because, through teaching, and reflecting about/on teaching, they discover pupil needs and identify their own instructional and pedagogical areas of strength to continue, and weaknesses to improve.

As most teacher education programs are based on contemporary educational philosophies such as child-centered instructional approaches, interdisciplinary content principles, blended learning methods, and teacher empowerment and self-regulation, it is important to expose PSTs to those philosophies, not simply by implementing them in practice, but also by developing critical thinking skills to expand their practice into meaningful and effective responses to pupils’ learning.

An instructional method that aligns with this educational philosophy is project-based learning (Pj-BL). Pj-BL has been described as an experiential, child-centered, cross-curricular, real-world connection to knowledge, and an independent learning approach which facilitates pupil autonomy in both learning and the development of life-enhancing skills (Thomas, 2000; Barron and Darling-Hammond, 2008; Bell, 2010; Kaldi et al., 2011; Girvan et al., 2016; Thys et al., 2016; Chen and Yang, 2019). Research on teachers’ views and experiences regarding the use of Pj-BL in their classroom practice has been conducted (Tamim and Grant, 2011; Doğan et al., 2013; Han et al., 2015); however, previous research on PSTs’ reflections on implementing Pj-BL is scarce, and there is a need to examine how prospective teachers analyze, identify, interpret, criticize, and reconstruct their practice in order to implement Pj-BL as a tool for promoting professional change.

Theoretical framework

Project-based learning (Pj-BL) is internationally recognized as an exploratory and experiential approach for learning, seeking to integrate school knowledge with real life through the development of academic and practical skills (Thomas, 2000; Kaldi et al., 2011; Girvan et al., 2016; Thys et al., 2016) as well as the cultivation of life-long learning skills such as social and communication skills, responsibility, self-regulation and self-confidence, flexibility, team-spiritedness, and good work attitude (Musa et al., 2012). Pj-BL is defined as any child-centered learning activity which acquires substance through the investigation, organization, and management of knowledge, materials, values, and actions over a variety of multisensory learning tasks which accommodate learners’ needs and require their active involvement (Thomas, 2000; Kokotsaki et al., 2016). Pj-BL is often designed around the idea of cross-curricular topics/themes, which may be drawn from real situations—which are not fragmented by the different curriculum subjects—that relate to pupils’ interests (Chu et al., 2016). Pupils are involved in the search for answers and solutions to phenomena (whether physical or social) that surround them, often having great significance for them (Thomas, 2000; Thys et al., 2016). This gives them the chance to be actively engaged with collective responsibility in designing fully or partially the content and the outline of the learning tasks aiming usually at producing a final learning product (construction, book, presentation, performance, etc.) or partial learning products during the learning process of the PjBL (Thomas, 2000; Thys et al., 2016). This special feature highlights pupil active action on learning content that are not always imposed on them as mandatory by the respective school system. Another characteristic of the PjBL is the provision of a long time frame for the study and the possibility that can be given in some cases of applying the approach to modify the direction of the study if the pupils are more interested in specific dimensions of the topic under study. This is a strength of the PjBL where pupils are recognized as a differentiated and heterogeneous group. The teacher’s role is transformed to a more supportive, guiding, co-researching role, providing feedback at all learning stages (Thys et al., 2016). Because of the efforts to unify in-school and out-of-school knowledge, learning requires an exploratory character and multiple dimensions (Girvan et al., 2016). The Pj-BL process involves design, implementation, and assessment phases. In all phases, pupils’ participation is necessary. In order to examine the importance of Pj-BL, it is necessary to evaluate the entire process, from the starting point to the final assessment phase product.

Therefore, Pj-BL has been internationally introduced in syllabuses in many teacher education preparation programs. A common principle of the organization of teacher education curricula is educating pre-service teachers in different cognitive areas, along with focusing on developing their exploratory and reflective thinking skills. This helps them to better learn from and manage issues that arise during the teaching and learning process (Kaplan and Rafaeli, 2015; Goldstein, 2016; Dag and Durdu, 2017).

Reflective thinking has been claimed to be difficult to define (Rodgers, 2002) because firstly, it is not clear how it is different from other types of thinking, and secondly, it is difficult to evaluate an act that is not clearly identified. Reflective thinking is based on reflective practice, closely associated with knowledge of the professional and the development of practitioners. Being a professional teacher requires reflection on one’s own teaching because as Freire (1996) concludes “I cannot teach with clarity unless I recognize my ignorance, unless I find out what I do not know, what I have learnt” (p. 2). In teaching practice, reflection is regarded as an active, persistent, and careful consideration/analysis/review of perceptions, knowledge, and/or actions that occurred in a specific period of time; by describing the strategies and steps that were followed, so that the PST can better understand and orchestrate practice (Adler, 1990).

Different types of reflection exist, which are distinguished based on the time frame and the quality (depth) of reflective thinking. The first type of reflection, according to Schön (1983) takes place during teaching (reflection in/about an action), where the teacher reflects during the lesson, in order to understand any problems that arise as they occur. The second type of reflection mainly takes place after teaching, where the teacher is distanced from the heat of the moment. This type of reflection can be performed either after the end of the teaching or by stopping and thinking in the middle of the process. Finally, the teacher can take the opportunity to seek solutions through discussions with colleagues or experts (Kaldi and Pyrgiotakis, 2009). Eraut, in 1995, working on Schon̈’s types of reflection, added another instance, that of reflection for action. This tool can be used in all phases of teaching and identifies the teachers’ ambitions and goals for their educational practice (Husu et al., 2008).

Regarding the quality (depth) of reflective thinking, Valli (1997) distinguishes the following levels of reflection: (a) technical reflection that mainly includes reflection for the fulfillment of techniques and skills defined to the teacher by external guidelines; (b) personalistic reflection that focuses on reflection of the PST’s personal action and performance, based on their values and beliefs; (c) consultative reflection, which includes a wider range of concerns in relation to the curriculum and educational strategies; and (d) critical thinking, based on the social, moral, and political aspects of school education. However, according to Manen (1997) and Kaldi and Pyrgiotakis (2009), the levels mentioned above fit three types of reflection: technical, practical, and critical.

Pre-service teachers’ reflective ability varies depending on where they are in their studies to become a teacher as well as to how specific reflective pedagogical strategies influence pre-service teachers to reflect on practice (Tsangaridou and O’ Sullivan, 1994). This can potentially either be attributed to the fact that PSTs cannot be critical of their teaching practice but can easily evaluate pupils’ performance, or because they have not yet learnt to reflect (Loughran, 2002; Halim et al., 2011; Wharton, 2012). However, through written tasks, PSTs can become able to critically understand the quality of learning, increase involvement and active participation in learning and knowledge building, improve their self-assessment ability, develop freedom of written expression, and increase the frequency of written reflection (Boud, 2001).

Nevertheless, it is necessary to clarify that the content of the written reflection may be different according to the reader whom the PST is addressing. For example, when PSTs produce written reflections for self-assessment purposes, they are usually more objective; however, when building a diary of their teaching practice as part of their course assessment, they may present only the most successful moments of the teaching practice, attributing the success more to themselves and less to the pupils (Rodgers, 2002; Smith and Southerland, 2007; Wharton, 2012).

Research on reflection in teacher education has identified descriptive reflection, which provides an account of events, analytical reflection, which searches for reasons, provides alternatives, and evaluates the result of teaching, and critical reflection, which takes into account the larger socio-political context (Yesilbursa, 2011). In Yesilbursa’s study on written reflection of prospective EFL teachers’ microteaching experiences, a qualitative content analysis methodological tool was used, and different modes and themes were extracted. The findings showed that the participants were not only descriptive but were also moved to be analytical in their reflections.

Moreover, previous research on PSTs’ reflective practice using written reflection has highlighted the challenge they face in achieving critical reflection (Pedro, 2005; Kaldi and Pyrgiotakis, 2009; Wharton, 2012). More specifically, many PSTs recorded in their diaries those areas of their practice that they considered most effective/successful. When they referred to factors they perceived as the least effective/successful, they tended to provide explanations closely linked to lack of time and inappropriate preparation for the classroom discipline and/or any unexpected events that arose during teaching (Kaldi and Pyrgiotakis, 2009). In addition, PSTs’ written reflections were focused on effective areas of their teaching practice due to the guiding questions or prompts provided for them. These often directed them to focus their thinking on explanation and improvement, rather than on analysis and understanding (Smith and Southerland, 2007; Halim et al., 2011).

Wharton (2012) studied patterns that appeared in the way writers represented themselves through reflection. In short, he wanted to highlight the writers’ identity and the strategies used in representing themselves and the team they belonged to. The results showed that the writers presented the team and themselves in a positive light. However, they willingly cited challenges as something that were finally dealt with. The presentation of positive events or resolution of challenges seems to be due to the fact that reflections were being evaluated; thus, the participants potentially felt that presenting themselves positively was important. Students recorded, in writing, the results of their teaching, knowing that someone will evaluate it. Therefore, reflection is likely to be constructed in such a way by the writer so that they and their teaching practice are positively represented. This is closely linked to teachers’ beliefs and perceptions, which influence and often guide teaching practice, as has been shown in study (Minott’s, 2008).

Research concerning prospective teachers’ views on the implementation of Pj-BL projects in their school practice has indicated that PSTs who use Pj-BL develop well-professionally (Tsybulsky and Oz, 2019), and, more specifically, acquire and advance problem-solving skills as well as awareness of their learning objectives for the lesson (Mettas and Constantinou, 2008; Baran and Maskan, 2011). Implementation of Pj-BL in a school teaching practice can increase PSTs’ satisfaction, positive emotions, efficacy, and autonomy, compared with traditional teaching approaches (Kaplan and Rafaeli, 2015). Student teachers can develop reflective skills when applying Pj-BL in their school teaching practice (Tsybulsky et al., 2018); they may adapt current educational beliefs and display positive attitudes toward Pj-BL (Tsybulsky and Oz, 2019). However, the modes of presenting reflective thinking for the implementation of child-centered learning approaches, such as Pj-BL, have not been explored in the literature.

Thus, in terms of evaluating educational tasks, many studies have been conducted; these emphasize appropriate reflective practice in education as an important action, which not only motivates teachers, but leads to greater teacher effectiveness (Buehl and Beck, 2015). However, there is a lot of discussion on improving the quality of PST school internships in a more reflective way. Most teacher education programs attempt to improve the educational process, carried out in the context of PSTs’ school teaching practice, through reflection, where assigned projects seek to connect research with theoretical and practical skills. Such assignments also seek to develop PSTs’ critical approach to educational tasks such as teaching and learning.

This review suggests that previous research on written reflection by PSTs regarding the implementation and evaluation of Pj-BL is scarce. Researchers need to investigate what, and how, prospective teachers evaluate and reflect on their teaching experiences using Pj-BL during school teaching. Analyzing PSTs’ reflective writing texts concerning the implementation of Pj-BL during school teaching, according to the modes of presentation of their reflections, is important since a deep understanding of PSTs’ reflective thinking can improve the quality and variety of understanding, necessary for building appropriate teacher education courses on reflective practice. The present study also differs from previous research because it uses written reflection, and follows a specific model (i.e., Yesilbursa’s model) to identify the modes and themes of PSTs’ reflective thinking regarding actual teaching practice in schools employing the Pj-BL approach.

Materials and methods

The aim of this study was to explore PSTs’ written reflection regarding their experiences during the implementation of Pj-BL in the context of their school teaching practice. Specifically, the research questions are shaped as follows:

(1) How do pre-service teachers evaluate their experience regarding the application of Pj-BL during their school teaching practice in their self-assessment written reports?

(2) What modes of position expression emerge from PSTs’ self-assessment written reports regarding the application of Pj-BL during their school teaching practice?

Two cohorts of 40 participants each were recruited from a Greek University Teacher Education 4-year course. Specifically, PSTs’ self-assessment reports were used as part of their semester evaluation regarding the implementation of Pj-BL in the school teaching practice component of their studies. Each PST provided a written report answering various questions related to three axes: (a) analysis and evaluation of pupil activities/tasks, (b) analysis and evaluation of instructional actions, and (c) lessons learned for future applications.

A convenience sampling strategy (Cohen et al., 2002) was applied for selecting participant PSTs in this study. The procedure was as follows: 200 final year undergraduate PSTs in a University-based Teacher Education course were sought; however, only 150 were found. We then contacted them and asked if they would be willing to participate in this study. Forty of them responded positively. We then asked those 40 PSTs to sign informed consent forms to participate in the study, allowing us to use their written reflective reports for research purposes.

Qualitative data were analyzed through content analysis by three researchers in order to cross-check the findings and to ensure validity and reliability in the data analysis process. The data analysis procedure was divided into two levels. The first level of analysis concerned the three axes of questions, from which the following thematic categories emerged: (1) pupil interest, (2) active pupil involvement, (3) comprehension of the content in the Pj-BL, (4) how to start the project, and (5) use of instructional means and materials. The resulting material was then analyzed based on the PSTs’ modes of expressing their positions on each thematic category. Specifically, modes were coded according to a similar categorization used by Yesilbursa (2011, p. 109) study: (a) positive reflection (PR), i.e., “I think that I incorporated pupils’ ideas to a great extent when we worked on the internet,” (b) negative reflection (NR), i.e., “pupils could not suggest many learning activities due to their young age and possibly the fact that they were used to carrying out learning tasks organized by the teacher,” (c) reflection on reasons (RR), i.e., “the topic’s units were all understood by the pupils because the content was suitable for the age group and I noticed that pupils participated more than in the curriculum subjects of the program,” (d) reflection on solutions (RS), i.e., “as we had not planned that, I promised pupils that we would look at and study some pictures about traditional costumes,” (e) reflection on personal learning (RL), i.e., “concerning classroom management I think that I should have a thorough discipline plan and spend some time on it.” In particular, for each PST, the attitudes s/he had according to the above modes were analyzed and for each thematic category, more than one mode was observed. For example, the phrase “pupils could not suggest many learning activities due to their young age and possibly the fact that they were used to carrying out learning tasks organized by the teacher” falls under both NR and RR. The modes were then grouped relative to each thematic category and recorded in tables, where the frequency of the participants who answered positively, negatively, those who justified, those who acquired personal learning, and those who provided solutions to the challenges they faced was recorded.

Results

The results were analyzed based on the qualitative content analysis approach. Five thematic units, based on the participants written reflections, focused on self-assessment of their teaching. The thematic categories for each unit and the modes that emerged from the data analysis are described below. The results are presented in descending order in terms of the volume and variety of the participants’ reflective thinking, according to the coding of modes.

Pre-service teachers’ reflection on pupils’ topic content comprehension

This thematic unit includes seven thematic categories concerning PSTs’ reflective writing on the teacher role in Pj-BL, pupil response to the content of the learning tasks, the actual topic comprehension by the pupils, and the challenging issues which require teacher support.

Teacher role as guiding, supportive, and providing feedback

Almost all participants indicated that during the Pj-BL projects they helped pupils wherever they had difficulty during the learning tasks and where they deemed their intervention was necessary. Their role could only be supportive and guiding, since within this approach, the goal is for pupils to build knowledge on their own. In addition, many PSTs reported that they supported pupils after completing a learning task by providing feedback concerning challenging aspects of the learning tasks:

“My support in some cases was giving feedback. More specifically, when questions arose from the pupils about what we were working on, we discussed them in the plenary of the class, where we all expressed our views and if something was not clear to the pupils, I explained it further, extending in that way their thinking” (PST-12).

It is interesting to note here that PSTs appeared to have realized and acted respectively that teaching style is transmitted from being teacher-centered to pupil-centered.

No difficulties faced by the pupils

The majority of the PSTs claimed that the pupils did not face any particular difficulties from their involvement in the topic. This is explained in the reflective writing texts, with the class learning readiness level particularly high in some cases, or because the learning tasks and goals were tailored to the pupils’ interests and needs:

“I believe that all the learning activities corresponded to both the interests and the cognitive level of the pupils in my class, so the pupils did not face any difficulties” (PST-20).

Moreover, PSTs reported that if there was any difficulty during the implementation of the Pj-BL approach, they managed to face it effectively.

Pupils’ topic comprehension as a challenge for PSTs

Many participants claimed that content was understood by the pupils when they could complete the learning tasks. PSTs reported that they noticed if the content was not understood or learnt, because pupils often asked questions:

“Regarding the understanding of the topic we developed I can say that the pupils seemed to understand the content through the class and the group discussions, from the questions I asked and they answered, from the learning activities we carried out after the introduction of all new information. They also referred to information we had in conversations during the school breaks” (PST-5).

From the above, it seems that PSTs could see that pupils understood the learning content as long as they could complete the learning tasks and/or participated in the learning process by asking questions.

Pupil response to the topic due to their interest in it and in the learning tasks

Almost half of the participant PSTs claimed that the pupils responded positively to the topic learning tasks; this was evident from the active participation of most of the groups and the interest they showed. In addition, the participants noticed pupils’ responses through frequently asked questions and clarifications requested by them, showing interest in the topic they were working on:

“The implementation of the learning tasks should be enjoyable and at the same time completely constructive for pupils. The terminology used, the instructions provided and the materials used during the learning tasks were familiar and accessible to them and thus this facilitated the participation of the whole class” (PST-15).

From this, we can see that PSTs recognize in their reflective writing that the teacher needs to make efforts in order to attract and maintain pupils’ attention and interest in the learning content.

Linking these findings to the subtheme of the topic comprehension through explanations and discussion during the learning process, we can observe that here PSTs reflect on what they have attempted to do when they realized that pupils had not understood or covered the topic content. These attempts indicate that their role becomes more supportive than didactic in the Pj-BL approach.

Moreover, according to less than half of the participants, pupils faced some difficulties in specific areas of the topic such as language-related learning tasks (i.e., writing or literary texts), structuring appropriate arguments, constructions, and procedural features of the Pj-BL approach, for example, cooperating during group work. Other difficulties faced by the pupils seem to be due, as the PSTs argue, not only to the low learning level, but also to the indifference shown by many pupils to specific project activities. However, the difficulties were addressed, and PSTs claimed that they provided the appropriate support and guidance:

“The only difficulty was pupils’ cooperation in the group work. Again, two of the four groups were the ones that had cooperation problems. In one group there was a pupil who was causing trouble as he was uncooperative and disruptive while in the second group there was a competition issue where everyone wanted to do the exact same thing” (PST-11).

Student teachers of the study tried to cover any parts of the topic that was not understood by the pupils through explanations and discussion during the learning process. Thus, we can observe here that PSTs reflect on what they have attempted to do when they realized that pupils had not understood or covered the topic content. These attempts indicate PSTs recognize that their role becomes more supportive than didactic in the Pj-BL approach.

Pupil response to the learning tasks due to appropriate PST preparation

Less than half of the PSTs reported that the pupils responded effectively to the learning tasks, because they themselves had planned an appropriate teaching plan which corresponded to pupils’ age and learning level, resulting in effective completion of the learning tasks. PSTs’ preparation refers to thorough class observation, the teacher’s specific information concerning pupils before teaching, and designing appropriate material for pupils to carry out learning tasks:

“As for the learning activities, they were close to the pupils’ abilities, since I had configured them according to the class level and their age and after having discussed with the class teacher” (PST-5).

From the above, we can observe that some PSTs reflected positively about their Pj-BL preparation to attract and maintain pupil attention and interest during the learning process and it would be expected that the majority of STs would have been able to report similar reflections. It appears that thorough preparation in Pj-BL should be further addressed in the specific teacher education program and an issue to carefully consider in other teacher preparation programs of studies.

Application of differentiated instruction for greater understanding

A number of participants reported that they had to implement differentiated instruction (DI) in various learning tasks of the topic in the Pj-BL approach. Differentiated instruction was carried out as part of PSTs’ response to pupils’ difficulties during the learning tasks and/or their learning readiness level:

“With the aid of the DI and the use of specific means and materials that corresponded to the pupil age, learning readiness level and preferences/interest, from what I understood and from the assessment tasks, there was a great deal of understanding about the most important content areas of the topic” (PST-1).

Here PSTs response to face difficulties that pupils found to understand the topic content showed quick reflexes and applied knowledge they had acquitted from the teacher preparation course in general as DI was part of their studies.

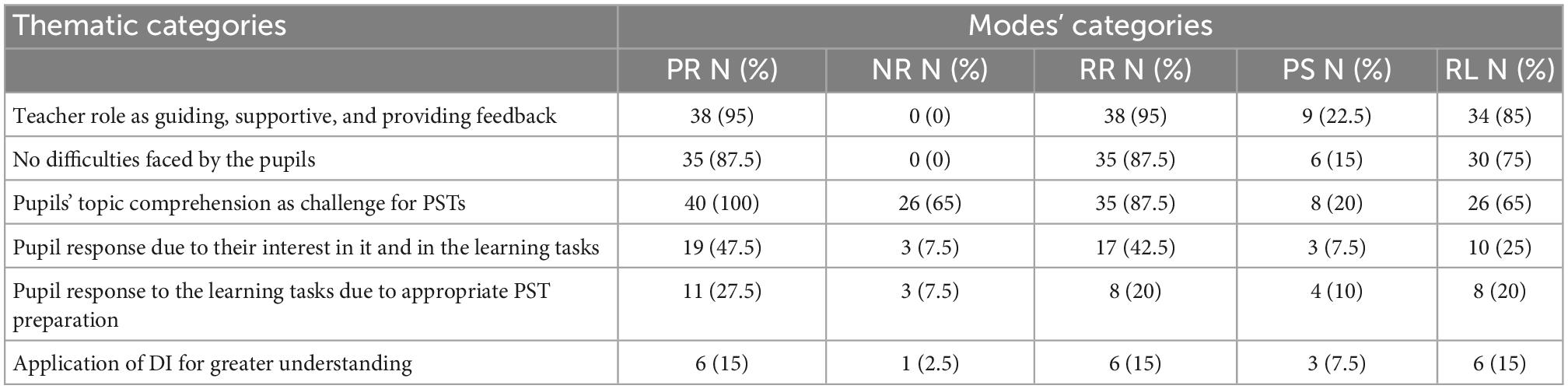

PSTs’ modes of expressing their positions regarding pupil topic content comprehension

Regarding the modes of expressing positions on the thematic categories, we observe that PSTs’ reflective writing was positive in terms of the guiding and supporting role they played, and that pupils did not face many difficulties in understanding the topic content. All of the PSTs reflected that they exhibited quick reflexes in supporting pupils with any parts of the topic content that they had not understood through giving further explanations and organizing discussions in the class. It is also worth noting that most PSTs justified their views in the reflective writing text, and several claimed that they developed further (acquired teaching knowledge as personal learning) because of their efforts and adaptation to a supporting and guiding role to help pupils understand the content of the topic. The general result from Table 1 is that the participant PSTs, in this thematic unit and indeed in all thematic categories, presented an enriched self-assessment and reflection. This was not only limited to a positive attitude regarding understanding of the content of the project; PSTs also demonstrated reflective thinking when justifying the teaching and learning outcomes, when they recognized the solutions they had provided, and when they reported teaching knowledge they had acquired.

Table 1. Pre-service teachers’ modes of expressing their positions regarding pupils’ content comprehension in the project-based learning (Pj-BL) approach.

Pre-service teachers’ reflection on pupil interest

As reported by most of the participant PSTs in their reflective writing texts, pupils responded to the learning tasks and showed an interest appropriate to their age and the topic. Six thematic categories were extracted concerning the pupils’ interest, which referred to (a) pupils’ interest for experiential learning tasks and for an enriched learning environment and (b) strategies applied in order to maintain pupils’ interest.

Methods to maintain pupil interest

“The majority of the participant PSTs reported that the interest was maintained to a large extent due to the game-based learning strategies used, the product’s construction and in the general the use of multisensory materials as well as the discipline strategies that most PSTs applied during class. All PSTs mention the need to apply organizational strategies in order to keep pupils interested:

I tried to keep them interested by using plenty of visual means which ranged from photos to videos. For this reason, in each thematic unit, which we were working on, I also accompanied it with supervisory material (PST-7).”

As reported by half of the participant PSTs, pupils’ interest was focused on experiential learning tasks as well as those that included constructions and games:

“They [pupils] loved the videos (they wanted to watch them twice or three times each) and they showed more interest in the experiential activities, other activities that included construction and crafts, painting, board games, reading a story, filling in a comic book, drama” (PST-12).

Participant PSTs realized in their reflective writing that the multisensory character of Pj-BL approach is an important element to maintain pupil interest and appreciated the benefit of using them.

PST’s teaching style can maintain pupil interest

The majority of the participants stated that, during the implementation of Pj-BL, they changed their instructional role and style due to the child-centered nature of this approach. This facilitated maintaining pupils’ interest in the topic by applying respective strategies in the approach. Furthermore, a number of PSTs emphasized that the pupils’ previous knowledge, participation, creativeness, and improvisation also played important roles in maintaining pupil interest:

“In order to maintain pupil interest, I had a certain teaching style both during the topic and in teaching the curriculum subjects which included elements of capacity, imagination, humor, performing actions, flexibility, changes and surprises, intense interactivity with the students, consistency, as well as classroom management techniques (which were not needed much during the topic)” (Y-2).

Fewer than half of the participant PSTs referred to a decreased pupil interest in learning tasks that contained educational software. This was attributed to the lack of pupil experiences with digital educational material. However, PSTs reported that they were able to deal with these difficulties, and at the same time, they claimed that the pupils’ indifference was emerged when teacher-centered instructional approaches were used:

Student participation decreased when teaching became teacher-centered (PST-14).

Here, as mentioned in the previous thematic category of PSTs’ reflection about pupils’ topic content comprehension, participants recognized in their reflective writing that changing their teaching style to become child-centered can maintain pupil interest in the topic study.

Pupils’ enthusiasm for a new learning environment

More than half of the participants reported that the pupils showed a special interest in the creation of a topic’s learning center in the class, and also in the visit of an expert to the classroom. Pupil interest was high both at the beginning and during the topic:

“On the day he was to come, from the morning (before we even entered the classroom) I was asked what time the beekeeper would come. They listened to him very attentively and asked him several questions which showed that they were interested” (PST-40).

Variation of pupils’ interest

Pupil interest, according to the opinions of several participants, varied between low and high depending on the content of the teaching unit and each pupil’s different interests. Pupil interest was observed in the entirety of the class and in group work:

“Pupils’ interest in the topic learning activities were generally increased, but it varied according to the thematic unit we were working on” (PST-6).

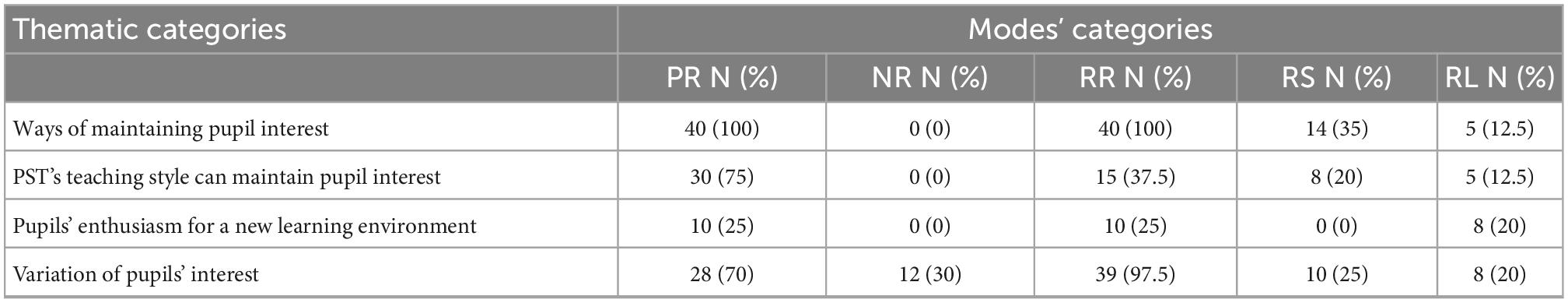

PSTs’ modes of expressing their positions on pupil interest

Regarding the modes of expressing positions on the thematic categories of this unit, we observed that many PSTs showed positive reflective thinking regarding the effect of their own teaching style and of their planning of experiential learning tasks on maintaining pupil interest during Pj-BL as well as in relation to the variations in pupil interest. It is important to mention here that in this thematic unit, most PSTs justified their views and provided reasons for increased pupil interest. Few PSTs pointed out (a) pupils’ enthusiasm for the learning center and (b) the benefits of the visit of an expert in the class as part of the Pj-BL approach. The small number of PSTs referring to this thematic category can be explained by the fact that PSTs were not asked to think about pupils’ response to specific characteristics of the Pj-BL approach. Moreover, in this unit, we observed quite a few PSTs who referred to providing solutions for raising and maintaining pupil interest in their teaching practice, as well as gaining personal benefits from their teaching (see Table 2).

Table 2. Pre-service teachers’ modes of expressing pupil interest in the project-based learning (Pj-BL) approach.

Pre-service teachers’ reflection on the use of means and materials

In this study, pre-service teachers developed their reflective thinking on the use of instructional means and materials during the implementation of the Pj-BL approach. Pj-BL is an experiential and interactive learning approach, where pupils can acquire knowledge by using a variety of materials and means in multisensory learning tasks. The four thematic categories that emerged from the data analysis are presented below.

Appropriate use of materials by pupils, due to familiarity with the materials

The majority of the participant PSTs reported that the materials used by the pupils, both in group and individual work, were appropriate because they were familiar with them. The pupils knew these materials because they had already used them, therefore, they did not have difficulties:

“There were no problems with the use of materials and means by the pupils. The materials and means such as worksheets, videos, desktops, adapted to their level and age, were fully understood” (PST-1).

The use of means and materials significantly contributed to the implementation of the topic in Pj-BL

Many participant pre-service teachers stated in their written reflective texts that the use of materials significantly contributed to the implementation of the topic in Pj-BL because pupils appeared to derive pleasure and interest from the topic. This resulted in increased participation and eventual, smooth completion of the learning tasks:

“They were able to use all the planned materials and means, which helped them to visualize the various information, to become more creative, to make beautiful crafts and to have the desired learning products. The pupils seemed to enrich what they knew about the Greek forest [the topic pupils worked during the Pj-BL] through enjoyable learning tasks and managed to engage to a very satisfactory degree with this topic” (PST-8).

Use of means and materials with the help of the teacher

A number of PSTs reported that pupils responded to the materials only after the PSTs intervened in various aspects of the topic in Pj-BL. PSTs’ interventions provided guidance before or during the learning tasks, and they intervened in any group that required more support:

“It should be noted that many times the cooperation of the children was not so good because they did not share and fight that one takes it from the other [sic]. The only problem was this, which I mostly tried to manage because what can you do in 10 min?” (PST-22).

Pupils’ complaints regarding fatigue from the use of materials

Only a few participant PSTs reported that a number of pupils expressed dissatisfaction with the use of the materials in the Pj-BL. This occurred in cases where learning tasks involved the use of ordinary materials for which pupils expressed their tiredness:

“The only thing I noticed was that they showed some reluctance when they had to cut with scissors” (PST-5).

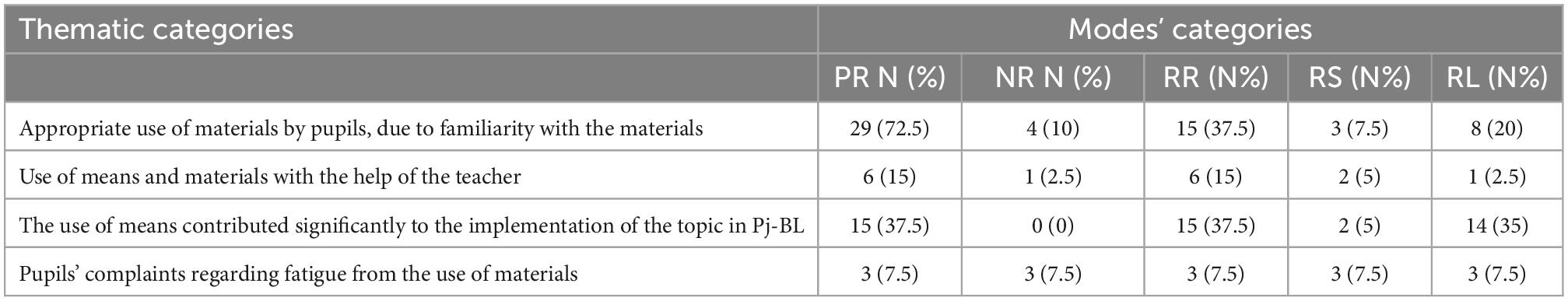

PSTs’ modes of expressing their positions on the use of means and materials

Analyzing the modes of expressing their positions that PSTs’ presented in the above thematic categories, we can note that the majority of participants (72.5%) were positive about the suitability of the materials used by the pupils, with most of them arguing that the pupils used the materials due to their familiarity with them. In addition, several PSTs (37.5%) claimed that the use of materials during the Pj-BL topic facilitated learning, and this was the main reason why the topic ran smoothly and why they justified their positive or negative views (37.5%). Similarly, 35% of the participants felt that they benefitted from the process of planning and from using a variety of materials and means in the implementation of Pj-BL. We also observed that a number of PSTs (7.5%) responded negatively regarding the use of materials (Table 3).

Table 3. Pre-service teachers’ modes of expression on the use of means and materials during the project-based learning (Pj-BL) approach.

Pre-service teachers’ reflection on pupils’ active participation in the learning process

Another thematic unit that emerged from the participant PSTs’ written texts was pupils’ active participation and involvement in various stages of the implementation of Pj-BL. PSTs’ reflective thinking included the level to which they gave space to the pupils to express their ideas during the Pj-BL approach, an important aspect of active pupil involvement in this learning approach. Four thematic categories emerged as follows:

Incorporating pupils’ ideas during Pj-BL

This thematic category pertains to PSTs’ reflective thinking regarding the incorporation of pupils’ ideas in topic development, in the topic learning center, in the choice of the materials, in classroom management (i.e., setting up class rules), and in designing learning products (i.e., creation of stories, constructions, etc.). The majority of the participant PSTs reported that they included pupils’ ideas in most parts of the Pj-BL topic, as they considered it necessary in this instructional and learning approach:

“When pupils boldly formulated their own ideas and more specifically in the learning task related to the creation of the collage, when they made suggestions and when they became involved in its perfection, helped a lot the process development [sic] and the product we all successfully delivered” (PST-3).

Pupils’ active participation resulted in the development of their creativity, imagination, initiative, and improvisation

Most of the participants referred to the positive results of the pupils’ active involvement in the learning process, which were stated to be: pupil interest and satisfaction, development of creativity skills, imagination, and taking initiative and responsibility for the learning process:

“I constantly encouraged pupils to take initiatives, improvise, imagine, adapt learning tasks to their interests and express their ideas. For this reason I believe that, through this topic in the Pj-BL approach, their creativity and imagination unfolded to a great extent, while also approaching the maximum of their possibilities in cognitive areas in which the pupils were rather ‘slow’ (PST-1).

In this category, we noticed that the participants appeared to be trying to highlight the importance of pupil engagement in the learning process in a rather critically reflective way, compared with the previous category, where PSTs simply stated how they included pupils’ ideas and experiences in the learning process.

Pre-service teachers’ satisfaction regarding pupils’ active participation

Almost half of the participants indicated that it was particularly enjoyable for them to incorporate pupils’ ideas in the learning process, because the lesson became more interesting, and the efforts they made were reflected in the pupils’ participation. For this reason, pupils were constantly encouraged to express their views and to analyze their ideas during the lesson. In addition, PSTs reported that pupil involvement was most successful both for achieving cognitive goals and for the enjoyable implementation of the learning process:

“I tried to include in the teaching process the materials that pupils brought to class about the sub-topics we were working on each time, such as the turtle shell, the dolphin video and the songs about the sea. Pupils expressed a great interest and enthusiasm bringing such materials and I was very happy about it” (PST-7).

Therefore, it is noticeable that in this category, PSTs positively assessed pupils’ active involvement, and did not simply report how the pupils engaged in the learning process.

Pupils’ indifference to being actively involved

A quarter of the prospective PSTs indicated that while they encouraged pupils to get involved by expressing their ideas, they did not manage to involve pupils successfully. It is interesting to note here that those PSTs who attempted to provide explanations for the pupils’ indifference to being actively involved, attributed this indifference to pupils’ lack of ideas, the fact that they did not seem to like the learning tasks, and the prepared plan of the topic. There was no effort to actually reflect on their own practice:

“The truth is that although I would very much like something similar to happen, as it really should be done in “authentic” projects, I did not manage to involve any of my pupils’ ideas during my project. This may be due in part to the fact that I had already prepared the lesson plans before I started teaching the project and I was ready to follow a specific schedule during the project hours. On the other hand, my students themselves did not come up with an idea for this and everything went as I had planned” (PST-20).

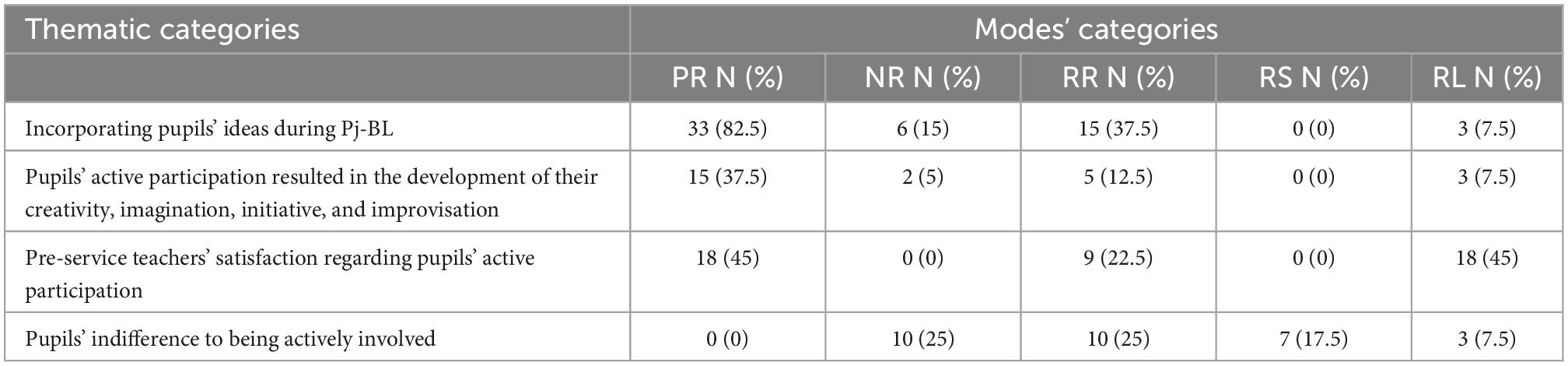

PSTs’ modes of expressing their positions on pupil active involvement during Pj-BL

Concerning the modes of expressing positions in the thematic categories of this unit, it is apparent that the participant PSTs exhibited a positive reflection mode in the first three categories; quite a few provided reasons for their reflection and indeed reflected on their own learning. It is interesting to note here that negative reflection and reflecting by providing solutions were only present in the thematic category “pupils’ indifference to being actively involved in the learning process.” This indicates that a rather negative category indirectly imposes the need to provide relevant explanations and solutions (see Table 4).

Table 4. Pre-service teachers’ modes of expressing pupil active involvement during project-based learning (Pj-BL).

Discussion and conclusion

Applying qualitative thematic analysis to written reflections, this study investigated PSTs’ experiences and thoughts regarding the implementation of Pj-BL during the school teaching practicum. The PSTs in this study implemented Pj-BL in Greek primary school classes during the final school teaching practice prior to graduation. Part of their evaluation was a self-assessment written reflection report based on several question. In these written texts, PSTs could illustrate their reflective thinking on the implementation of Pj-BL. Thematic units and categories were extracted from the written texts using data analysis, and these were subsequently analyzed according to Yesilbursa’s (2011) coding of modes of expressing positions that are present in reflective thinking.

Based on the results, the majority of participants in this study appear to exhibit a thoughtful stance toward their teaching practice with regard to Pj-BL; however, in general, they evaluate themselves positively, and, often at the same time, present an apologetic attitude regarding challenges and unsuccessful elements—as they themselves define—of their teaching practice during Pj-BL. In short, most PSTs positively comment on and evaluate the teaching experiences they had, even for cases that were less successful—according to them. They tend toward positive self-assessment, attributing the effectiveness of the approach to themselves, whereas any pitfalls during the teaching and learning process are attributed to difficult circumstances, to the pupils, or to unforeseen events. As discussed in other research, this may be partly explained by the fact that the specific PSTs knew that the written report was part of their course evaluation, therefore they write in such a way as to demonstrate academic success. That is, although they report the challenging issues encountered during teaching practice, they produce such reflective arguments in their reports so as to positively influence the evaluator (Wharton, 2012). Written reflection is evidence of teaching actions and connects theory with practice, aiming to generate a critical attitude toward teaching practice. However, written reflection carries inherent risks concerning the honesty of the writer and the accuracy of what they report. Therefore, it is necessary for prospective teachers to learn to reflect and to be taught how to write about and evaluate themselves (Loughran, 2002). As pointed out in similar research (Halim et al., 2011), guiding questions during reflection play a particularly important role in shaping the PSTs’ responses. Specifically, prospective teachers are motivated by the questions and the ways in which they are instructed to answer, thereby limiting themselves. It is important to mention again the purpose for which the PSTs reflected on the present research. The specific prospective teachers provided reflections knowing that this was part of their course evaluation. Therefore, it would be expected that several of them presented a positive image of their teaching practice for Pj-BL.

Analyzing the results closer, we can see that pupils’ content comprehension was one of the richest reflections for that particular thematic unit that emerged from data analysis. Most participants claimed in their reflections that pupils understood the topic content and they attribute this to their own appropriate preparation before the teaching practice, supporting and guiding pupils in discovering knowledge as opposed to lecturing them in a rather traditional teacher way. Thus, they seem to have perceived that pupils’ content comprehension is not related to pupils themselves, as much as it is connected to the teachers’ role in the process. In previous research, it was shown that prospective teachers’ reflective thinking varies, and refers more to the degree in which they have succeeded as class teachers, as opposed to pupils’ learning (Halim et al., 2011). This is similar to the outcome of the present study, where PSTs seemed to be rather narrow-minded in their reflective thinking regarding the factors that supported pupils’ active involvement, focusing mainly on their own teaching preparation. Therefore, it is evident that PSTs need guidance on how to view the overall picture of the teaching and learning process when they reflect. This can lead to the development of effective changes in school teaching to address all pupil needs. On the other hand, if we consider that Pj-BL has been often criticized for poor pupil knowledge acquisition, compared with more traditional modes of instruction or with curriculum subject areas where content knowledge is emphasized (Thomas, 2000; Markham et al., 2003; Hixson et al., 2012), we can conclude that the PSTs in this study assessed the comprehension of the topic’s content as very successful. They reflected in a rather enriched manner according to the modes of reflection, providing reasons for this success, expanding on teaching aspects that they learned, such as how their role as more of a shadow instructor improved pupils’ content learning, and they thought reflectively when providing solutions to solve challenges regarding content understanding. This may be due to the fact that content comprehension is an important indicator of effective pupil learning; PSTs had the opportunity to flourish as deeper thinkers in their teaching practice. Thus, when PSTs are given the appropriate guidelines for written reflection, they can develop further as reflective practitioners and can acquire an appropriate knowledge base for implementing Pj-BL.

In this study, it was observed that the majority of PSTs reflect positively on the active involvement of pupils in the Pj-BL process. At the same time, some of them justified their assessment when they explained that pupils had expressed their opinions and ideas at various stages of the process and took the initiative, developing social and organizational skills. It is also important to note that a number of participants who reported satisfaction from the inclusion of pupils’ ideas, simultaneously highlighted their personal learning benefits. Actively engaging pupils at all stages of Pj-BL is considered to be one of the basic characteristics of the approach; this was assessed positively by the specific PSTs. However, only a small number demonstrated a level of reasoning in the presentation of their own learning benefits in their reflections. From the perspective of critical reflection, it is argued that reflection may tend to remain at the level of relatively undisruptive changes in superficial thinking (Fook and Gardner, 2012); therefore, many PSTs in this study seem to have not achieved critical reflective thinking.

Concerning PSTs’ views in their written reflections on pupil interest during the Pj-BL process, it is evident that they positively assessed pupils’ interest and that they attributed this to their own practice as class teachers. More specifically, they think of their teaching style as guiding and supporting, leading pupils to discover knowledge and to practice procedural skills, increasing pupils’ interest in the learning process. Furthermore, many PSTs recognized that pupils’ personal interests as well as the topic itself are important factors for general pupil interest in a topic. In this thematic unit, PSTs appeared to provide reasons and argue their views. Moreover, those PSTs who negatively referred to the pupil interest, claimed that they attempted to provide solutions and that they gained learning benefits for their future teaching practice. A possible explanation for this could be the fact that PSTs knew, in theory, that pupil interest is one of the main procedural learning goals of this child-centered approach, and wanted to demonstrate to the reader that they met this target.

Regarding the thematic unit on the materials and means used during the lessons in the Pj-BL approach, most participants present a positive reflective attitude. They state that the materials were an important part of the topic, helping pupils to experience the content more intensely and to successfully complete the learning tasks; therefore, the materials contributed to meeting the topic’s learning aims. This fact is probably attributed to the pupils’ familiarity with most of the materials used, making the lesson more interesting and understandable. In addition, when using the materials, pupils often worked in groups, and this made them cooperate and remain committed to the group for a longer period of time. Therefore, when using materials during school teaching practice, PSTs feel confident about those that are already familiar to the pupils, and would need further support to experiment with materials and means that are not often used, as part of the often innovative character of pre-service teachers’ practice.

Finally, PSTs in this study expressed descriptive and analytical reflective thinking; however, they only partially showed an aspect of critical reflection when they connected teaching practice to larger socio-political contexts such as educational aims, the school, and pupil needs.

The results of this study should be interpreted according to the limitations that exist. In particular, the present study is limited by the following aspects: (a) it only included a sample from one University Teacher Education course, and extension of the study to other Teacher Education courses could be used in future research; (b) enrichment of the research tools used to interview the participants and after data analysis of the written reflective texts.

The implications of this study lie in the provision of appropriate conditions for a thorough reflective practice performed by PSTs, which can guide them to look for/at the overall picture of their school teaching practice, incorporating the critical reflective aspect of thinking.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adler, S. A. (1990). The reflective practitioner and the curriculum of teacher education paper presented at the annual meeting of the association of teacher educators. ERIC Doc. Reprod. Serv. No. ED 319:693.

Baran, M., and Maskan, A. (2011). The effect of project-based learning on pre-service physics teachers electrostatic achievements. Cypriot J. Educ. Sci. 5, 243–257.

Barron, B., and Darling-Hammond, L. (2008). Teaching for meaningful learning: A review of research on inquiry-based and cooperative learning. Book excerpt. San Rafael, CA: George Lucas Educational Foundation.

Bell, S. (2010). Project-based learning for the 21st century: Skills for the future. Clear. House 83, 39–43. doi: 10.1080/00098650903505415

Boud, D. (2001). Using journal writing to enhance reflective practice. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 90, 9–17. doi: 10.1002/ace.16

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative research in sport. Exerc. Health 11, 589–597. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Brookfield, S. D. (2017). Becoming a critically reflective teacher. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Buehl, M. M., and Beck, J. S. (2015). “The relationship between teachers’ beliefs and teachers’ practices,” in International handbook of research on teachers’ beliefs, eds H. Fives and M. G. Gill (New York, NY: Routledge), 66–84.

Calderhead, J., and Gates, P. (1993). Conceptualizing reflection in teacher development. Brighton: Falmer Press.

Calderhead, J., and Gates, P. (Eds.) (2003). Conceptualising reflection in teacher development. Abingdon: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203209851

Chen, C. H., and Yang, Y. C. (2019). Revisiting the effects of project-based learning on students’ academic achievement: A meta-analysis investigating moderators. Educ. Res. Rev. 26, 71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2018.11.001

Chu, S. K. W., Reynolds, R. B., Tavares, N. J., Notari, M., and Lee, C. W. Y. (2016). 21st century skills development through inquiry-based learning. Berlin: Springer Nature. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-2481-8

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2002). Research methods in education. Abingdon: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203224342

Cubero-Pérez, R., Cubero, M., and Bascón, M. J. (2019). The reflective practicum in the process of becoming a teacher: The tutor’s discursive support. Educ. Sci. 9, 1–21. doi: 10.3390/educsci9020096

Dag, F., and Durdu, L. (2017). Pre-service teachers’ experiences and views on project-based learning processes. Int. Educ. Stud. 10, 18–39. doi: 10.5539/ies.v10n7p18

Doğan, T., Totan, T., and Sapmaz, F. (2013). The role of self-esteem, psychological well-being, emotional self-efficacy, and affect balance on happiness: A path model. Eur. Sci. J. 9, 31–42.

Fook, J., and Gardner, F. (Eds.) (2012). Critical reflection in context. Abingdon: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203094662

Girvan, C., Conneely, C., and Tangney, B. (2016). Extending experiential learning in teacher professional development. Teach. Teach. Educ. 58, 129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.04.009

Goldstein, O. (2016). A project-based learning approach to teaching physics for pre-service elementary school teacher education students. Cogent Educ. 3, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2016.1200833

Halim, L., Buang, N. A., and Meerah, T. S. M. (2011). Guiding student teachers to be reflective. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 18, 544–550. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.05.080

Han, S., Yalvac, B., Capraro, M. M., and Capraro, R. M. (2015). In-service teachers’ implementation and understanding of STEM project based learning. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 11, 63–76. doi: 10.12973/eurasia.2015.1306a

Hixson, N. K., Ravitz, J., and Whisman, A. (2012). Extended professional development in project-based learning: Impacts on 21st century skills teaching and student achievement. Charleston, WV: West Virginia Department of Education.

Husu, J., Toom, A., and Patrikainen, S. (2008). Guided reflection as a means to demonstrate and develop student teachers’ reflective competencies. Reflect. Prac. 9, 37–51. doi: 10.1080/14623940701816642

Kaldi, S., and Pyrgiotakis, G. (2009). Student teachers’ reflections of teaching during school teaching practice. Int. J. Learn. 16, 185–196. doi: 10.18848/1447-9494/CGP/v16i09/46599

Kaldi, S., Filippatou, D., and Govaris, C. (2011). Project-based learning in primary schools: Effects on pupils’ learning and attitudes. Education 3–13 39, 35–47. doi: 10.1080/03004270903179538

Kaplan, H., and Rafaeli, V. (2015). Project based learning and emotional-motivational experience among student teachers from different cultural groups (Research Report in Hebrew). Tel Aviv: Mofet Institute.

Kokotsaki, D., Menzies, V., and Wiggins, A. (2016). Project-based learning: A review of the literature. Improv. Sch. 19, 267–277. doi: 10.1177/1365480216659733

Loughran, J. J. (2002). Effective reflective practice: In search of meaning in learning about teaching. J. Teach. Educ. 53, 33–43. doi: 10.1177/0022487102053001004

Manen, M. V. (1997). From meaning to method. Qual. Health Res. 7, 345–369. doi: 10.1177/104973239700700303

Markham, T., Larmer, J., and Ravitz, J. L. (2003). Project based learning handbook: A guide to standards-focused project based learning for middle and high school teachers. Novato, CA: Buck Institute for Education.

Mettas, A. C., and Constantinou, C. C. (2008). The technology fair: A project-based learning approach for enhancing problem-solving skills and interest in design and technology education. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 18, 79–100. doi: 10.1007/s10798-006-9011-3

Minott, M. A. (2008). Valli’s typology of reflection and the analysis of pre-service teachers’ reflective journals. Austr. J. Teach. Educ. 33, 55–65. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2008v33n5.4

Musa, F., Mufti, N., Latiff, R. A., and Amin, M. M. (2012). Project-based learning (PjBL): Inculcating soft skills in 21st century workplace. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 59, 565–573. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.315

Orland-Barak, L., and Yinoh, H. (2007). When theory meets practice: Student teachers’ reflections on their classroom discourse. Teach. Teach. Educ. 23, 857–869. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2006.06.005

Pedro, J. Y. (2005). Reflection in teacher education: Exploring pre-service teachers’ meanings of reflective practice. Reflect. Prac. 6, 49–66. doi: 10.1080/1462394042000326860

Rodgers, C. (2002). Defining reflection: Another look at John Dewey and reflective thinking. Teach. Coll. Record 104, 842–866. doi: 10.1111/1467-9620.00181

Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Smith, L. K., and Southerland, S. A. (2007). Reforming practice or modifying reforms?: Elementary teachers’ response to the tools of reform. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 44, 396–423. doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1098-2736

Tamim, S., and Grant, M. M. (2011). How teachers use project-based learning in the classroom. Bloomington, IN: Association for Educational Communication and Technology, 452–461.

Thomas, J. (2000). A review of research on project-based learning. Report prepared for the autodesk foundation. San Rafael, CA: Autodesk Foundation.

Thys, M., Verschaffel, L., Van Dooren, W., and Laevers, F. (2016). Investigating the quality of project-based science and technology learning environments in elementary school: A critical review of instruments. Stud. Sci. Educ. 52, 1–27.

Tsangaridou, N., and O’ Sullivan, M. (1994). Pedagogical reflective strategies to enhance reflection among pre-service physical education teachers. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 14, 13–33. doi: 10.1080/03057267.2015.1078575

Tsybulsky, D., and Oz, A. (2019). From frustration to insights: Experiences, attitudes, and pedagogical practices of preservice science teachers implementing PBL in elementary school. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 30, 259–279. doi: 10.1123/jtpe.14.1.13

Tsybulsky, D., Gateneo-Kalush, M., Abuganem, M., and Grobgeld, E. (2018). “Project-based-learning: Look at teacher trainees’ experiences,” in INTED18 proceedings, (Valencia: IATED Digital Library), 1424–1430. doi: 10.1080/1046560X.2018.1559560

Valli, L. (1997). Listening to other voices: A description of teacher reflection in the United States. Peabody J. Educ. 72, 67–88. doi: 10.21125/inted.2018.0240

Wharton, S. (2012). Presenting a united front: Assessed reflective writing on a group experience. Reflect. Prac. 13, 489–501. doi: 10.1207/s15327930pje7201_4

Yesilbursa, A. (2011). Reflection at the interface of theory and practice: An analysis of pre-service English language teachers’ written reflections. Austr. J. Teach. Educ. 36, 50–62. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2012.670622

Keywords: written reflection, modes of expressing positions, pre-service teachers, project-based learning, school practicum

Citation: Kaldi S and Zafeiri S (2023) Identifying reflective modes in pre-service teachers’ written reflections on the implementation of project-based learning during the school practicum. Front. Educ. 7:1072090. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1072090

Received: 17 October 2022; Accepted: 24 November 2022;

Published: 02 February 2023.

Edited by:

Stefinee Pinnegar, Brigham Young University, United StatesReviewed by:

Mary Frances Rice, University of New Mexico, United StatesCelina Lay, Brigham Young University, United States

Copyright © 2023 Kaldi and Zafeiri. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Stavroula Kaldi,  a2FsZGlAdXRoLmdy

a2FsZGlAdXRoLmdy

Stavroula Kaldi

Stavroula Kaldi Stella Zafeiri

Stella Zafeiri