- Department of English Language and Literature, Middle East University, Amman, Jordan

The explores the impact of using both ADDIE Model, which stands for Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation, as an instructional design and UDL in planning for English Literature Online courses during COVID-19 in higher education from the perspective of the students. Up to the researcher’s knowledge, no prior studies have been conducted to explore the effect of the use of ADDIE model and UDL in online English Literature courses for graduate students in universities or other forms of higher education from the perspective of the students. A quantitative approach was used for collecting the data, where a four-part questionnaire was distributed to 90 students, who were randomly chosen from the students of a group of English Literature professors from different public and private universities in Jordan, who were asked to plan for their online English Literature courses through integrating both the ADDIE model, with its principles of Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation, and Universal Design for Learning (UDL) with its principles of Engagement, Representation, Action and Expression. As a conclusion, the study shows the positive impact of using both ADDIE Instructional Design Model and UDL in English Literature Online courses on the students’ performance from the perspective of the students.

Introduction

Many students in the Arab world, be they high school students, undergraduates, or postgraduates, find it difficult to communicate in English Language. Furthermore, Arabs who take the IELTS exam score lower and are often ranked far below their global counterparts in English proficiency (Alhabahba et al., 2016). Additionally, many students show better performance in the receptive skills, listening and reading, than in the productive skills, speaking, and writing (Awajan, 2022). This is just as true for Jordanian students as it is for students from neighboring countries in the Arab world. In Jordan’s public schools, the syllabi of English courses tend to focus more on students learning reading and grammar skills in English over the four basic language skills of reading writing, listening and speaking. This is also true of a many of the private schools in the kingdom. Thus, when students want to enroll in English courses at university, they often find it difficult as the curricula of university level English language courses is designed to improve upon those already learned English skills that prospective students should previously possesses. Likewise, if those students do not improve their rudimentary English language skills learned in school and bring them into the twenty-first century, then it makes it even more difficult for these students to enter the job market. These are the reasons why it is imperative for English Departments at university and colleges within Jordan to create courses that will develop the communication, critical thinking, analytical and other such skills of their students. Moreover, the curriculum design must not only meet the needs of classroom teachers and students, but also the needs of online teachers and students because the way in which content is delivered online is much different than that of the classroom.

Like the rest of the world, Jordan also succumbed to a long lockdown during the global COVID-19 pandemic when academic institutions were forced to switch from classroom study to online learning whether or not that learning was synchronous or asynchronous. As Hu and Huang (2022) state, administrators, teachers and stakeholders alike were challenged by the COVID-19 lockdowns to undertake online learning with as much effort and determination as possible. Indeed, because the transition to online learning was so hurried, there was little or no time to plan for it. As a result, all members of academia from teachers and professors to grade school and postgraduate students were unready for online learning, including those in Jordan.

Nevertheless, online teaching has become even more crucial over the last 2 years (Zhang, 2020). In fact, after Jordan’s Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research discovered the benefits of online learning, it has now incorporated online teaching and learning as part of all university and college academic programs in Jordan (Accreditation and Quality Assurance Commission for Higher Education Institutions, 2020). Thus, nowadays, university and college professors put great effort and much thought into designing content for online courses, whether these lectures are asynchronous or synchronous. Furthermore, English Literature and English language professors need to work together when designing both synchronous and asynchronous online courses because most students often are not capable of expressing themselves freely English in lectures, which are face-to-face. Though remaining behind this veil for some students may be advantageous by giving them the confidence to speak in English and use their English language skills without anyone around them. According to Czerkawski and Bumen (2013), “[A]cademic and professional content standards at the national and state level” need to be included in the design and development of higher education programs (p. 1,480) as well. Haider et al. (2022) state that higher education institutions support their professors and instructors’ with ongoing training workshops to improve online teaching and to assure its quality. Haider and Al-Salman (2021) also declare that online learning and teaching has recently been common among higher education instructors despite its challenges, which are continuously decreasing.

Peskin et al. (2010) state that, when it comes to English Literature, even some students who speak English as their mother tongue have trouble comprehending what they are studying. Salameh (2012) agrees that this is true of both native and non-native speakers especially regarding their understanding of poetry. She adds that, because of their inability to understand particular characteristics of the English language such as grammar along with their lack of knowledge in even the basic skills of the language, students find studying English Literature especially difficult (Salameh, 2012).

Moreover, it may also be a result of most Arab students’ (Jordanians included) inability to express themselves in English because of their deficient speaking skills in the language (Huwari, 2019). Along those same lines, Huwari (2019) also believes that other causes may to blame for this weakness in English speaking skills such as “linguistic matters (like pronunciation, grammar, vocabulary), psychological factors (inhibition, lack of motivation), learning environment (topics of speaking modules, limited time), [and] lack of practicing” (p. 203).

Another issue, Arab students have with speaking English as a second language is the merging of the language with their mother tongue, Arabic (Salah, 2021). Likewise, Hussein and Al-Emami (2016) state that “the students’ level of language proficiency,” “the texts’ linguistic and stylistic degree of difficulty” and “the degree of cultural (un)familiarity [are] crucial issues which impact the productivity of the teaching -learning process.” Furthermore, they propose helping students better comprehend the text of English literature by “[n]arrowing the distance between students and the text by relating the themes and characters of the literary work to the students’ personal experiences,” and “by making students read independently” (p. 125).

According to Yao (2021), teachers in the conventional classroom settings can develop material that encourages students to participate and learn; online learning, on the other hand, requires teachers to blend activities that complement the interests of their students. Moreover, Zhang (2020) asserts that the students are less motivated while learning online than they are in the conventional classroom setting. As a result, many English Literature professors and teachers have been obliged to enroll in a number of workshops and search for a variety of different online instructional designs to help them develop better online courses. At the same time, they must also insure high-quality learning to their students that meets the outcomes and objectives of their English Literature courses. Brewer et al. (2001) assert that online learning requires special attention and should be carefully planned as it “can either facilitate or impede the learning process” (p. 12). VanSickle (2003) posits when planning their online learning curriculum, teachers should consider the interests and internet use of their students.

White (2004) recognizes that there are many ways and means of designing online course curricula that develop the comprehension of students and teach them in a manner that boosts interaction between teacher and students. Likewise, Abernathy (2019) posits that teachers can develop online teaching plans that apply conventional teaching and learning techniques to online learning. Since, as Almelhi (2021), suggests, today’s students are keen on technology, teachers should also integrate this technology into their online lesson plans to get students to participate more and collaborate with other students as well.

Moreover, there are some very well-recognized methods for teaching in the traditional classroom that would work just as well in online teaching. Indeed, many studies on the subject have concluded that using these well-known methods is key in providing a good learning experience. Thus, colleges and universities must put in more effort into designing online English Literature courses for native speakers of Arabic.

When examining the text through the perspective of literary theories, English Literature is mostly dependent on creative, critical, and analytical thinking skills. The analysis of this literature, therefore, depends mainly on what the students believe they take away from the literature. However, despite behind a cloak of sorts, many Jordanian students studying English Literature online are not brave enough to speak up and offer their opinions or perspectives on the literature they are studying. Bunsom et al. (2011) comment on this subject by saying that it is a rather daunting task for teachers not to make the students feel they are being forced to study and understand literary texts that are simply just too difficult for them to study and understand. Indeed, this puts a strain on both the teachers and the students.

Because many online learning instructional designs have come about recently, using both the ADDIE Model and UDL to enhance the performance of undergraduate students in online English Literature courses will help to solve the aforementioned issues in designing online learning. Additionally, both of these designs are used to develop the learning of the students and to enhance the high-quality in teaching and learning in online English Literature courses.

Literature review

ADDIE instructional design for online learning in higher education

Designed in 1975 by Florida State University’s Center for Educational Technology, the ADDIE (Analyze, Design, Develop, Implement, and Evaluate) Instructional design framework was first developed for use by the American military, where it was known as ADDIC (Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, Control) (Branson, 1978; Nadiyah and Faaizah, 2015; Maddison and Kumaran, 2017). However, the name change was necessitated when the instructional design model was introduced to civilian teachers (Tzu-Chuan et al., 2014). These days, ADDIE is used by many instructors because of its workability.

According to Shelton and Saltsman (2007) “brave” undergraduate teachers started using ADDIE to step away from the conservative teaching techniques long before COVID-19 and lockdowns gave them no choice. Still, these teachers—well-versed in using ADDIE—think that online teaching will only result in “inadequacy and being ill-prepared” (p. 14). Nevertheless, Shelton and Saltsman (2007) believe that the ADDIE framework is “a generic instructional model that provides an organized process for developing instructional materials” (p. 14). However, they amalgamate the third stage (Develop) and fourth stage (Implement), leaving them with only four stages instead of five when using the ADDIE model (p. 15).

Soto (2013) however, believes that the ADDIE model is a well-known model and considers it to be the best instructional model for use in online education. Moreover, Abernathy (2019) claims that by using the model, teachers develop both the participation and learning of their students. In fact, using ADDIE when designing an online course of their own, Tu et al. (2021) found students were more satisfied and less insecure about the subject. For these reasons, many teachers and lecturers have adopted the ADDIE model. In simplest terms, it provides teachers with a sound, efficient, and rewarding plan that presents both teachers and students with the assurance of a better learning experience (Zhang, 2019; Lin, 2012). Moreover, it is particularly used as an effectual design model that offers a systematically sound learning design in higher education (Fang et al., 2011).

Ozdileka and Robeck (2009) used it for their investigation into the “operational priorities of instructional designers” through “a thematic content analysis” that they carried out by surveying 29 instructional designers who work in education. The two concluded that the Analysis step is quite an important step of the ADDIE model because this step takes into account the interests, levels, background knowledge and other characteristics of learners more than any other step of the ADDIE Model. Likewise, it was established that particular steps of the ADDIE framework are more critical than other steps, thus requiring more focus. Therefore, if steps like Analysis are taken more seriously, better consequences may result in a better learning experience.

Exploring the need analysis for training and its application was the focus for Bamrara and Chauhan (2018). Their study emphasizes how ADDIE can use the tools of information and communication technology in the study of data patterns to “explore the correlation between techniques/approaches of training need analysis and evaluation of training program for n = 100.” For instance, when designing an academic writing course for university teachers, KOÇ (2020) applied ADDIE to a course created in Turkey due to not only the vitalness of such a course but also the weaknesses suffered by undergraduate and graduate students from different departments when it comes to academic writing. In the end, Bamrara and Chauhan (2018) study proved that the academic writing of these students could be improved thanks to the use of the ADDIE model design.

More recently, ADDIE has been used in teaching online English Language courses in universities and colleges. For example, using the ADDIE model, free online English language courses were designed by Balanyk (2017) for non-native English speaking undergraduate hopefuls at The Virtual Academic Bridge Program (VABP). Still, it has yet to be used to design online courses for teaching English Literature in universities and colleges.

When designing blended English language courses at Shandong Vocational College, Yao (2021) justified the use of the ADDIE model by explaining how postgraduate students are fanatical about their electronic devices. Consequently, this would motivate them to try learning English online while also helping teachers overcome the difficulties that come with teaching the English language online.

To build joint communications among the online university community learning English, Zhang (2020) also used the ADDIE model to improve the understanding and performance of his students. Because it did, indeed, develop the competence and performance of his students, using the ADDIE model turned out to be successful for Zhang (2020).

Another application of ADDIE was used by Almelhi (2021) in order to improve the creative writing skills of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) college students. Almelhi arbitrarily chose 60 students from the English Department and used a checklist to assess their creative writing skills. As a result, the study concluded that the EFL students did, indeed, improve their creative writing skills.

Finally, an English language textbook was developed by Rahmadhani (2022) he claimed was effectual and sensible since it focused primarily on grammar and disregarded speaking which he believed could affect students in a negative way. However, Rahmadhani (2022) concluded that textbook need to be improved by including the communicative skills such as speaking to meet the student’s goals of learning English speaking skills. As a result, Research and Development (R&D) is now an important part of the ADDIE model.

Universal design for learning in in higher education online learning

Czerkawski and Bumen (2013) declare that the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a “pedagogical model that emphasizes learner’s individual differences by providing them access to quality education” (p. 1,480). It includes three core principles—representation, expression and engagement—all of which helps develop student learning in universities and colleges. What is more, Czerkawski and Bumen state that UDL has long been integrated into online learning at universities and colleges.

Furthermore, the Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST) defines UDL as “a set of principles for curriculum development that give all individuals equal opportunities to learn” in a way that amalgamates the needs, backgrounds and levels of students (2003, p. NA). Rose et al. (2006) also reveal that during execution of the model, the three UDL principles are based on the individual needs of the students.

The principles of the UDL model—presentation; action and expression; and engagement and interaction—were integrated into plans for developing online curriculum at universities and colleges by Dell et al. (2018). One thing they found was that it provided students with disabilities with better access to online learning. Along with UDL, however, Dell et al. (2018) also used the Rose and Meyer (2008) model and its three principles when creating an online teacher education course designed to prepare teachers for an expected influx of students over their professional careers (Rose and Meyer, 2008; The Center for Applied Special Technology [CAST], 2013; He, 2014). The course provided teachers with the chance to experiment with online learning before actually using it with their learners. The study’s results revealed that the 24 participating teachers developed confidence and self-perception through this online learning experience.

Using rudiments of the principles of UDL along with combining the CAST approach, in which the three principles of UDL are used with the Goff and Higbee approach by Rao and Tanners (2011) in an online university course. At the end of the course 25 students said they were satisfied with the course, giving different reasons. First all of them were given different choices on how to access course materials. Second, they felt that the activities supported their learning, and third, the interaction encouraged the students so that they wanted to participate and learn more. They also mentioned they thought the design of the course was flexible and could be added into an online course in a variety of ways that would meet the needs and interests of students.

Additionally, Houston (2018) presents the idea of how the principles of UDL might be incorporated into online learning. She also looked at the challenges that instructors could face when integrating the design into online learning. Highlighting the problems and their solutions of framing a development plan using the UDL model that could be used over and over by colleges and universities for online teaching was the focus of a study by Fovet (2020) who based his research on his own experiences. Rose et al. (2006) researched the effects of applying UDL to university courses and highlighted the continuous improvement of these courses by implementing UDL principals into their design.

This study endeavors to investigate the effect of using ADDIE Instructional Design Model together with Universal Learning Design (ULD) on the undergraduate student performance in online English Literature courses in universities and colleges. For instance, Hu and Huang (2022) used UDL to investigate whether or not it was effective at improving the skills of English language students by applying the three principles of UDL. They concluded that the students’ performance improved so much that they all were incorporated into the online learning programs.

As aforementioned above, the use of ADDIE and UDL has been independently used to design online undergraduate courses at universities and colleges. Still, the researchers know no other study that has used both models together in creating curricula for online courses in colleges and universities. The study by Trust and Pektas (2018) is one example of those who have integrated the ADDIE model with UDL in their planning to enhance the professional development of teachers from all over the globe who took an online course that meets the different needs of learners. Past surveys of their courses prove that all students achieved the targeted goals. Three online courses planned by Rao et al. (2015) by using both designs. Their study found that incorporating the two designs improved the organization of students and their interchange with their teachers while at the same time offering them flexibility. The analysis was based on the students’ perspectives on their own learning.

Up to the researcher’s knowledge, no prior studies have been conducted to explore the effect of the use of ADDIE model and UDL in online English Literature courses for graduate students in universities or other forms of higher education from the perspective of the students. Furthermore, the study attempts to answer these two questions:

Question 1: What is the effect of using ADDIE Model with Universal Design for Learning in English Literature online courses from the perspective of the students?

Question 2: What are the challenges that faced the English Literature undergraduate students in the online English Literature courses designed?

Methodology

Participants

A group of English Literature professors from various public and private universities were asked to plan their online English Literature courses using both the ADDIE (Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation) model and the UDL model with its principles of Engagement, Representation, Action and Expression. From this group of professors, 90 of their online English Literature students were chosen to respond to a questionnaire designed to measure the effect of using both models to plan online English Literature courses. Additionally, in the latter part of the questionnaire, students were asked to communicate the challenges that they encountered during the learning and teaching process of their online English Literature courses.

Data collection and analysis

Using a quantitative approach, data was collected using a four-part questionnaire that was distributed to 90 online English Literature students who were randomly chosen A group of English Literature professors from various public and private universities were asked to plan their online English Literature courses using both the ADDIE (Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation) model and the UDL model with its principles of Engagement, Representation, Action and Expression. Respondents were asked to rank each statement on the questionnaire base on a numerical scale ranging from 1 to 5 with 1 being “Totally Disagree” and 5 being “Totally Agree.” Part one of the questionnaire is comprised of statements related to the respondents. This is followed by the second part which features statements related to the professors’ application of the ADDIE model. Next, part three features statements about the professor’s use of the UDL model. Finally, the fourth part asks students to communicate the challenges they faced in their online English Literature courses and how they overcame these challenges. Cronbachs’ alpha—a test that gauges the internal reliability of a theoretical entity—was carried out on the questionnaire. Means and standards deviation were also analyzed for responses to the studies first question with a means between 3.68 and 5.00 being notable, from 2.34 to 3.67 being average, and from 1.00 to 2.33 being insignificant.

Data

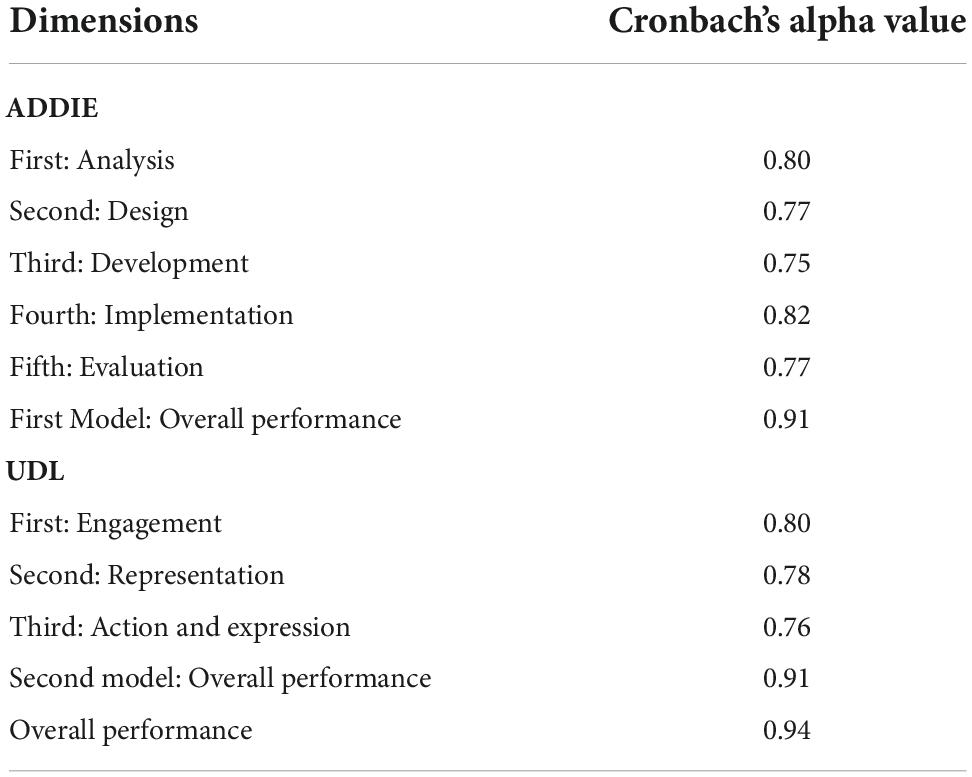

As mentioned above, using Cronbachs’ alpha—a test that gauges the internal reliability of a theoretical entity—was carried out to show the reliability of the questionnaire. Table 1 presents the significantly high relationship between the variables (α = 0.05). As seen in the table below, Cronbach’s alpha value ranges from 0.75 to 0.91 for the responses given by students as they relate to ADDIE. Similarly, Cronbach’s alpha value ranges from 0.76 to 0.91 for the responses given by students as they relate to UDL. General performance is 0.94 meaning that student performance has improved for the online English Literature courses taught by professors that utilized both models in their design.

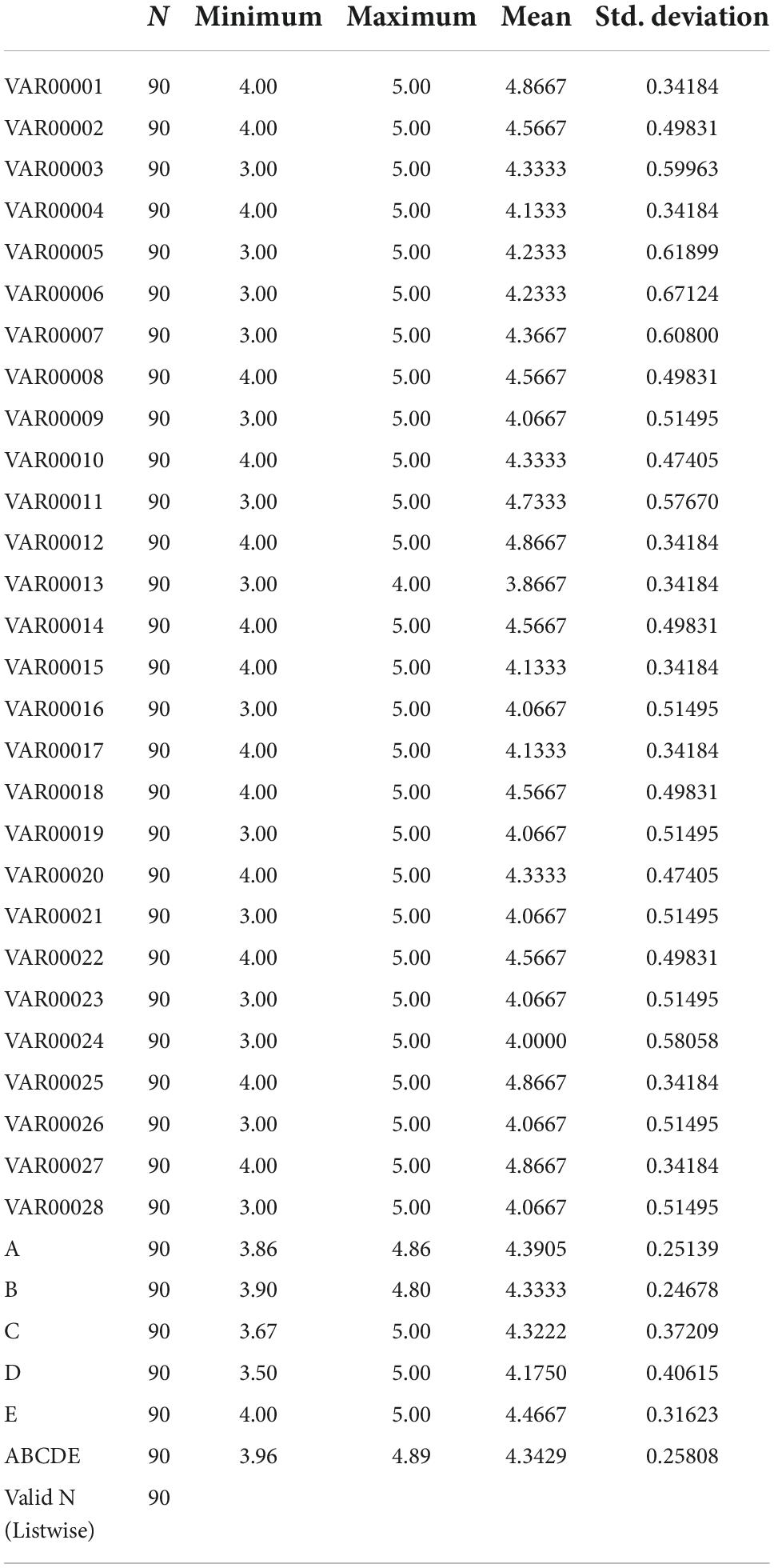

The data acquired from the responses to the questionnaire were analyzed and the descriptive statistics are shown below in Tables 2, 3. Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the responses of students to the statements related to the incorporation of the ADDIE model into the online English Literature courses. It illustrates the effect that the utilization of this model had on their performance as measured through student responses.

Discussion

As they relate to Analysis—the first step in ADDIE model—the average mean of statements rated between 1 and 7 is over 4.1333. The student’s responses provide evidence that professors applied the Analysis step quite well when planning their online English Literature courses. Additionally, students could clearly recognize their learning outcomes and objectives which likely means that professors took into account the background knowledge, academic level, needs, and interests of their students that allowed for a smart outcome. These first two statements were 4.8667 and 4.5667, respectively. Interestingly, these were also the highest means. Since these two statements define the outcomes of the course, these statements are very significant to both professors and students. The reason for this is that everything involved in planning like course content, resources and teaching strategies has to be aligned with the outcomes. As Mahajan and Singh (2017) posit, the whole learning process is contingent on learning outcomes; therefore, every element that comes after that must be aligned with them. These learning outcomes must be beneficial to students, and students should be aware of what these learning outcomes are before they enroll in the course. Furthermore, Mahajan and Singh outcomes should be written in coalition with the assessment.

Also according to the results, the needs and abilities of the students also improved. As these English Literature courses are held online, this shows that professors understood the importance of defining and taking into consideration the needs and abilities of the students. The professors actually accomplished this in the first stage—Analysis—where they define the students’ need analysis because students require these skills to use and operate e-learning platforms, to gain access to lectures, to obtain resources, and to complete their coursework. Rahmadhani (2022) argues the indispensability of this stage for both students and the instructors. Bettering these skills makes learning more efficient.

Two other statements of the Analysis stage that pleased the online English Literature students who took part in the study were delivery methods and resources. As stated before, everything in the planning process has to be aligned with the outcomes. This means that assessment strategies and tools, course content, course materials, teaching strategies, and delivery method all have to be taken into consideration during this stage. Drljača et al. (2017) assert that planning how learning will be delivered and attained happens in the Analysis stage. In this way, students have the assurance of a successful learning experience. Drljača et al. (2017) also put forward the idea that the Analysis stage is a determined and frequentative step that, if implemented correctly, will lead to both a better learning experience and an improvement in student performance (p. 5). Likewise, Shelton and Saltsman (2007) believe that the stage in which the course outline is designed, the setting is readied, and students are encouraged to improve and become independent is during the Analysis stage (p. 55).

Statements 8 through 17 are related to the second stage of ADDIE used in designing online English Literature courses—Design. The mean rating for these statements ranges between 0.34184 and 0.57670, meaning the professors completed this stage purposefully. This stage is where professors plan their e-content. Along with the Analysis stage, the Design stage is crucial because these two stages are really where planning begins. Students seemed pleased with the content of the course as well as its organization. They were also pleased with the activities and teaching strategies that the professors incorporated into their curriculum which also encouraged them to participate more by using the English language. Additionally, the students also seem content with how they are assessed in the course, whether those assessments were formative or summative. The professors’ proper designs of their courses were evidenced by the high ratings given by the students for this stage.

Next is the third stage of the ADDIE model—Development. At this stage, applications and learning platforms that students will use during the learning process for activities and assignments are identified, selected and readied for uploading. Students also rated this stage very high proving how satisfied they were with the applications and learning platforms as well as their flexibility and user-friendliness. Once this stage was complete, students were ready to start their online English Literature courses. It is notable that, even though Dousay and Logan (2011) believe the Development stage to be a difficult one, Gagné et al. (2004) assert that, once it has been planned, designed and given the stakeholders consent, then it can only lead to the best possible outcomes. Such was the case with the 47 participating professors of this research.

The Implementation stage is the fourth stage of the ADDIE method. It is at this stage where the professors deliver the course content, whether it be synchronous or asynchronous. Most importantly, this is where professor and student finally start the teaching and learning process. Students responded to statements 21 through 24 that are related to this stage. The mean rating of these statements differs from 4.0000 to 4.5667 meaning that the students were very pleased with the way their professors delivered the content along with their professors teaching strategies, and the timing of their activities and assignments. Students were also satisfied with their assessment results. As Richey et al. (2010) suggest, the Implementation stage is very important because this where the success or failure of the first two stages of the ADDIE method—Analysis and Design—will present. Moreover, Dousay and Logan (2011) believe that the evaluation of Implementation stage is the result of the production of the stage itself. Nonetheless, it is safe to assume that students were able to avail all of the material, resources, and activities that they needed to successfully reach their learning outcomes as their increase in performance during their online English Literature courses was the result.

Finally, we have the Evaluation stage where, as part of evaluating the use of the ADDIE model by their professors, students responded to questions about their learning experience, give their feedback, and communicated what challenges they faced while taking the course and how they overcame them. This stage consists of four statements with a mean that varied from 4.8667 to 4.0667. Greer (2016) posits that good results achieved in the Evaluation are the outcome of systematic planning during the Design stage.

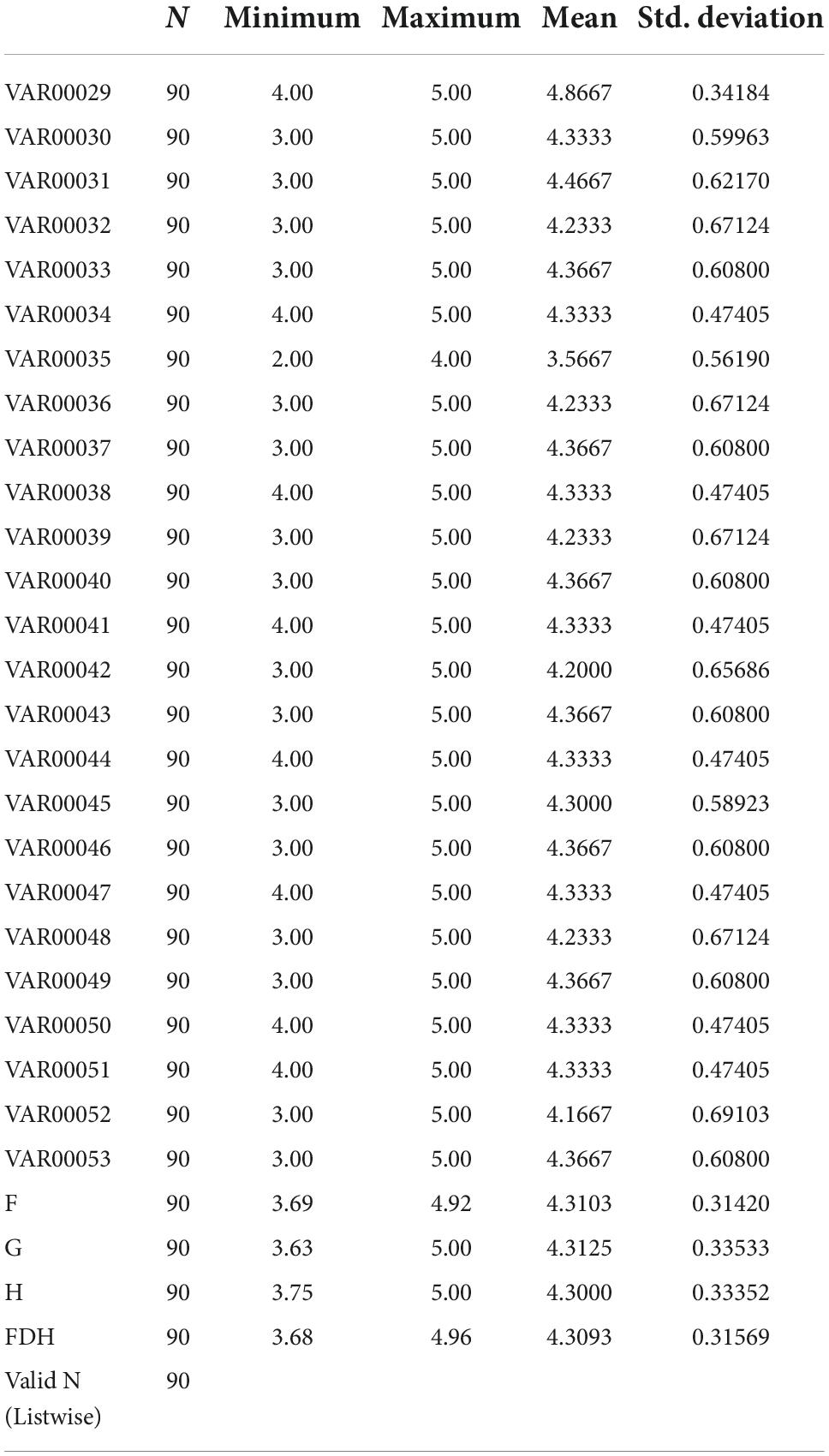

The UDL is the second model that professors used in planning their online English Literature courses. Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics for student responses to statements related to incorporating UDL into online English Literature course, showing how students believe the use of UDL affected their performance.

Engagement is the first principle of UDL. During Engagement, the professor incorporates all of the elements of learning that will engage students in the learning process. Statements 29–41 are rated based on participant satisfaction with their engagement in the lecture as well as what helped them become engaged, especially since, as mentioned before, university and college students are weak in English language proficiency in general and English Literature especially (Peskin et al., 2010; Salameh, 2012; Alhabahba et al., 2016). The mean for these statements vary between 4.2333 and 4.8667. Students proved their capabilities in reaching their learning outcomes by accepting the strategies, activities and learning style utilized during their online English Literature course. They were also able to understand and apply the content of the course to real world situations. Furthermore, along with the applications and platforms used in both synchronous and asynchronous modes, the students were very happy with the game-oriented activities and felt all of this made the learning process seem almost effortless. Additionally, they were happier because they felt more engaged as a consequence of the audiovisual material made available to them both in and out of the online classroom. They also expressed their approval for their assigned pre-readings and pre-questions. What is more, they had absolutely no problems work in groups or filling out the self/peer-assessment while they were enrolled in their online English Literature courses. All of this is the result of the fact that UDL main goal is to think about the needs, interests and levels of students. Indeed, the resources and strategies that the professors utilized are used to help support the students throughout their learning experience. Likewise, they may spark ideas, provide and build upon appropriate vocabulary, make simpler newly introduced information, and for teachers, these resources and strategies may help them look inside the minds of their students, inspire their minds and guide their students’ way of thinking down the path that leads to achieving their learning outcomes. As Eichhorn et al. (2019) argue, when the target of the design is to integrate and engage all students in the learning and teaching process, the importance of Engagement cannot be stressed enough.

The next principle of UDL is Representation which is presented in statements 42–49 of the questionnaire. These statements show participant responses to the online English Literature courses that they have taken. The rated means of these statements range from 4.2000 to 4.36667, meaning that the students felt that Representation is a significant principle in determining their performances and how they view the course. Without doubt, Representation is a critical in UDL because it focuses on the ways in which students learn. Some students are auditory learners, others are visual learners, and still others are tactile learners (Pritchard, 2009). Each of these ways of learning must be thoroughly taken into consideration during the Representation principle. Thus, the participating professors were asked to take this principle into account when designing their online English Literature courses. In this part of the questionnaire, students were asked to respond to statements regarding whether or not the images, audios, and videos and their content were relevant to the course content and if they helped the professor deliver the appropriate information. Their responses confirm that the audiovisual resources did, indeed, supported the course content, materials, and strategies used in presenting the course. They were also satisfied with guest visits and added that the applications used were beneficial. The reason for this is because English is the second most often used language in Jordan. Moreover, no matter their age, students find that expressing themselves in English can be difficult. However, English is critical for understanding English Literature because it needs critical, creative, and analytical thinking to be able to present, discuss, or even write about a literary text and create arguments for them. As Dell et al. (2018) assert the Representation principle provides students with a variety of opportunities to obtain information; as a result, it is necessary when planning online English Literature courses.

Action and Expression are the third principles and are presented in statements 50–53 in the questionnaire. The mean rating for these statements ranges from 4.1667 to 4.3667. The principle of Action and Expression is important because it concentrates on the ways in which students communicate their thoughts and express themselves whether it be through listening, speaking, writing or doing. These are all taken into account during the Action and Expression principle of course planning with UDL. Again, this is why the professors were asked to use UDL and take this principle into account when they planned their online English Literature courses. Meanwhile, the results are clear: however, they chose to express themselves, the students were happy with the activities and assignments given for both their formative and summative assessments.

As discussed before, the effect of these two designs on student performance in online English Literature courses is encouraging and noteworthy. Rao et al. (2015) agree that the impact of using both ADDIE and UDL is beneficial, stating that planning online course is a time consuming process that often takes great effort; however, once it is completed, planning is time saving and effortless for the professor during the learning process. Similarly, Trust and Pektas (2018) declare that by using both methods for planning an online course leads students to successful learning outcomes of the course.

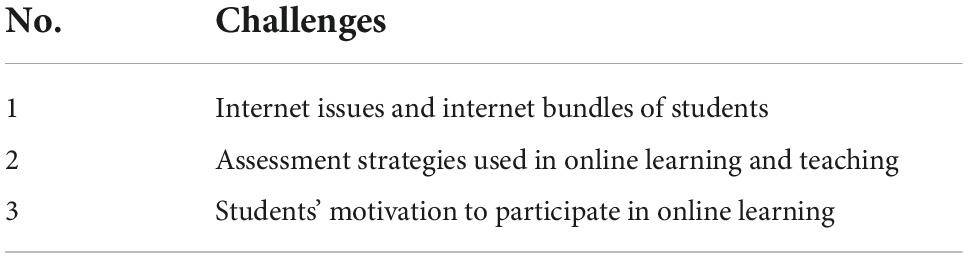

In part four, students communicate the challenges they have faced during the course and how they overcame those obstacles in reaching the learning outcomes of their online English Literature courses that were planned using both the ADDIE and UDL learning methods. Table 4 shows these challenges in order of their occurrence.

Table 4. Challenges by students in online English literature courses that were planned using both the ADDIE and UDL models.

As can be seen in the table, most students claimed that there were three basic challenges they faced during their course. Because both distance learning and online learning are new concepts in the Middle East, and both only began to be used during the recent global pandemic, the needed infrastructure is lacking with no decent internet networks or services available that are conducive to online learning. Because most students purchase internet bundles, the case was often that the students ran out of service before finishing their studies. Additionally, these bundles are also very expensive, so not all students can afford to keep purchasing them over and over again. However, because the lectures were recorded, students were able to overcome these obstacles by reviewing the lectures and assignments they may have missed. These recordings can be downloaded and used offline, and could also be shared. Additionally, the professors are savvy to know what user-friendly and flexible online learning platforms offer the maximum tools that support the learning and teaching process.

The second challenge is the way that online learning and teaching is assessed. The students criticized the assessment strategies used in online learning and teaching during the pandemic, as these assessments went from using traditional strategies of assessment to using rubrics-based and project/task-based assessments. As a result, students are not accustomed to the new kind of assessments. As mentioned by Haider et al. (2022) evaluation and assessment strategies used in colleges and universities changed during the pandemic. Nevertheless, this issue was solved by using a variety of assessment strategies that are better suited to the needs of the students, but align themselves with course outcomes at the same time (Accreditation and Quality Assurance Commission for Higher Education Institutions, 2020). Furthermore, Haider and Al-Salman (2021) also state that the assessment tools used in online learning are more effective and satisfying for students.

Finally, the third challenge is the Students’ Motivation to Participate in Online Learning. Nearly all of the students complained that online learning can sometimes be demotivating. They say this is particularly true when there is no audiovisual or the video cameras are not open. The challenge was overcome by some of the students through opening the cameras with facial and body movement recognition which seems to encourage the students. They also put a lot of effort into using the available resources and pre-lecture activities they were given by their professors for their online English Literature course.

Conclusion and recommendations

In sum, this study shows that there are positive impacts on student performance when online English Literature courses are planned using both the ADDIE and UDL models. Cronbach’s alpha value ranges from 0.75 to 0.91 for student responses to the statements related to ADDIE. Nearly identical are the Cronbach’s alpha values for student responses to the statements related to UDL which range 0.76–0.91. The overall performance is 0.94 meaning that performance increased for students of online English Literature courses that were designed with the use of both the ADDIE and UDL models. The descriptive statistics for the student responses to the statements related to English Literature online courses that used both ADDIE and UDL models in the planning of these courses are proof that an increase in student performance is the positive and considerable result of using the two models.

Recommendations

1. More studies need to explore the factors that enhance student performance in online English Literature courses in higher education.

2. More studies need to explore the factors that enhance student performance in other online courses in higher education.

3. More studies need be done on assessment in online learning.

4. More studies need be done on the challenges instructors and student face in assessment.

Limitations

The study is limited to the time and place it is conducted. It is also limited to the students of the mentioned online English Literature courses. The results of the study cannot be generalized to all students in higher education.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the Middle East University in Amman, Jordan, for their financial support granted to cover the publication fees of this research article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abernathy, D. (2019). ADDIE in action: A transformational course redesign process. J. Adv. Educ. Res. 13, 8–19.

Accreditation and Quality Assurance Commission for Higher Education Institutions, (2020). E-learning policy paper, the future of higher education in Jordan and the timetable for digital transformation in higher education. Available online at: http://en.heac.org.jo/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Guide-for-Quality-Assurance-Criteria-and-Procedures-at-Higher-Education-Institutions.pdf (accessed September 10, 2022).

Alhabahba, M. M., Pandian, A., and Mahfoodh, O. H. (2016). English language education in Jordan: Some recent trends and challenges. Cogent Educ. 3, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2016.1156809

Almelhi, A. M. (2021). Effectiveness of the ADDIE Model within an E-learning environment in developing creative writing in EFL Students. English Lang. Teach. 14, 1–20. doi: 10.5539/elt.v14n2p20

Awajan, N. W. (2022). Towards new instructional design models in online English literature courses during COVID-19 for Sustainability Assurance in Higher Education. Online J. Commun. Media Technol. 12:e202241. doi: 10.30935/ojcmt/12531

Balanyk, J. (2017). “Developing English for academic purposes MOOCS using the ADDIE model,” in Proceedings of the 11th international technology, education and development conference, Valencia. doi: 10.21125/inted.2017.1506

Bamrara, A., and Chauhan, P. (2018). Applying ADDIE model to evaluate faculty development programs. Int. J. Smart Educ. Urban Soc. 9, 25–38. doi: 10.4018/IJSEUS.2018040103

Branson, R. K. (1978). The interservice procedures for instructional systems development. Educ. Technol 3, 11–14.

Brewer, E. W., DeJonge, J. O., and Stout, V. J. (2001). Moving to online: Making the transition from traditional instruction and communication strategies. ERIC. Available online at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED453792 (accessed September 1, 2022).

Bunsom, T., Singhasiri, W., and Vungthong, S. (2011). “Teaching English literature in Thai universities: A case study at King Mongkut’s University of Technology,” in Proceedings of the 16th English in South-East Asia Conference: English for People Empowerment, (Yogjakarta: Sanata Dharma University), 237–252.

Czerkawski, B., and Bumen, N. (2013). “Universal design for E-learning: A review of the literature for higher education,” in Proceedings of the E-Learn, World conference on E-learning on corporate, government, health care and higher education 2013, Ls Vegas, NV.

Dell, C. A., Dell, T. F., and Blackwell, T. L. (2018). Applying universal design for learning in online courses: Pedagogical and practical considerations. Journal of Educators Online. 12, 166–192. doi: 10.9743/JEO.2015.2.1

Dousay, T., and Logan, R. (2011). “Analyzing and evaluating the phases of ADDIE,” in Proceedings of the design, development and research conference, Cape Town.

Drljača, D. P., Latinović, B., Stankovic, Z., and Cvetković, D. (2017). “ADDIE model for development of e-courses,” in Proceedings of the international scientific conference on information technology and data related research, Belgrade. doi: 10.15308/Sinteza-2017-242-247

Eichhorn, M. S., Lowry, A. E., and Burke, K. (2019). Increasing engagement of English learners through universal design for learning. J. Educ. Res. Pract. 9, 1–10. doi: 10.5590/JERAP.2019.09.1.01

Fang, M. J., Zheng, X. X., Hu, W. Q., and Shen, Y. (2011). On the ADDIE-based effective instructional design for higher education classrooms. Adv. Mater. Res. 27, 1542–1547. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.271-273.1542

Fovet, F. (2020). Universal design for learning as a tool for inclusion in the higher education classroom: Tips for the next decade of implementation. Educ. J. 9, 163–172. doi: 10.11648/j.edu.20200906.13

Gagné, R. M., Wager, W. W., Golas, K. C., and Keller, J. M. (2004). Principles of instructional design, 5th Edn. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning. doi: 10.1002/pfi.4140440211

Greer, J. (2016). Evaluation methods for intelligent tutoring systems revisited. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 26, 387–392.

Haider, A. S., Hussein, R. F., and Saed, H. A. (2022). Jordanian university instructors’ practices and perspectives of online testing in the COVID-19 Era. Front. Educ. 7:856129. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.856129

Haider, S., and Al-Salman, S. (2021). Jordanian University Instructors’ perspectives on emergency remote teaching during COVID-19: Humanities vs sciences. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1108/JARHE-07-2021-0261

He, Y. (2014). Universal design for learning in an online teacher education course: Enhancing Learners’ confidence to teach online. MERLOT J. Online Learn. Teach. 10, 283–298.

Houston, L. (2018). Efficient strategies for integrating universal design for learning in the online classroom. J. Educ. Online 15, 1–16. doi: 10.9743/jeo.2018.15.3.4

Hu, H., and Huang, F. (2022). Application of universal design for learning into remote English education in Australia amid COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Stud. Educ. 4, 72–85. doi: 10.46328/ijonse.59

Hussein, E. T., and Al-Emami, A. H. (2016). Challenges to teaching English literature at the University of Hail: Instructors’ Perspective. Arab World English J. 7, 125–138. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol7no4.9

Huwari, I. F. (2019). Problems faced by Jordanian Undergraduate students in speaking English. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Change. 8, 203–217.

KOÇ, E. (2020). Design and evaluation of a higher education distance Eap course by using the ADDIE model. Electron. J. Soc. Sci. 19, 522–531.

Lin, Y.-J. (2012). ADDIE Instructional Model. University of Library Science and Information. Available online at: http://terms.naer.edu.tw/detail/1678782 (accessed September 10, 2022).

Maddison, T., and Kumaran, M. (2017). Distributed learning: Pedagogy and technology in online information literacy instruction. Sawston: Chandos Publishing.

Mahajan, M., and Singh, M. (2017). Importance and benefits of learning outcomes. IOSR J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 22, 65–67. doi: 10.9790/0837-2203056567

Nadiyah, R. S., and Faaizah, S. (2015). The development of online project based collaborative learning using ADDIE model. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 195, 1803–1812. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.06.392

Ozdileka, Z., and Robeck, E. (2009). Operational priorities of instructional designers analyzed within the steps of the Addie instructional design model. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 1, 2046–2050. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2009.01.359

Peskin, J., Allen, G., and Wells-Jopling, R. (2010). The educated imagination: Applying instructional research to the Teaching of symbolic interpretation of poetry. J. Adolesc. Adult Lit. 53, 498–507. doi: 10.1598/JAAL.53.6.6

Pritchard, A. (2009). Ways of Learning: Learning theories and learning styles in the classroom, 2nd Edn. London: David Fulton Publishers.

Rahmadhani, M. S. (2022). The development of English textbook by using ADDIE-MODEL to improve English speaking skill for Non-English department students. Anglo-Saxon 12, 65–79.

Rao, K., Edelen-Smith, P., and Wailehua, C. (2015). Universal design for online courses: Applying principles to pedagogy. Open Learning 30, 35–52. doi: 10.1080/02680513.2014.991300

Rao, K., and Tanners, A. (2011). Curb cuts in cyberspace: Universal instructional design for online courses. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 24, 211–229.

Richey, R. C., Klein, J. D., and Tracey, M. W. (2010). The instructional design knowledge base: Theory, research, and practice. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203840986

Rose, D., and Meyer, A. (2008). A practical reader in universal design for learning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Press.

Rose, D. H., Harbour, W. S., Johnston, C. S., Daley, S. G., and Abarbanell, L. (2006). Universal design for learning in postsecondary education: Reflections on principles and their application. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 19, 135–151.

Salah, R. (2021). Jordanian university students’ use of English: Urban-rural dichotomy and university location. Adv. Lit. Study 9, 105–113. doi: 10.4236/als.2021.93012

Salameh, F. (2012). Some problems students face in studying English poetry in Jordan. Int. Forum Teach. Study 8:41.

Shelton, K., and Saltsman, G. (2007). Using the Addie model for teaching online. Int. J. Inf. Commun. Technol. Educ. 2, 14–26. doi: 10.4018/jicte.2006070102

Soto, V. (2013). Which instructional design models are educators using to design virtual world instruction? MERLOT J. Online Teach. Learn. 9, 364–375.

The Center for Applied Special Technology [CAST] (2013). What is universal design? Available online at: http://www.cast.org/udl/ (accessed August 25, 2022).

Trust, T., and Pektas, E. (2018). Using the ADDIE model and universal design for learning principles to develop an open online course for teacher professional development. J. Dig. Learn. Teach. Educ. 34, 219–233. doi: 10.1080/21532974.2018.1494521

Tu, C., Zhang, X., and Zhang, X.-Y. (2021). Basic courses of design major based on the ADDIE Model: Shed light on response to social trends and needs. Sustainability 13:4414. doi: 10.3390/su13084414

Tzu-Chuan, H., Jane, L. H., Turton, M. A., and Su-Fen, C. (2014). Using the ADDIE model to develop online continuing education courses on caring for nurses in Taiwan. J. Contin. Educ. Nurse 45, 124–131. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20140219-04

VanSickle, J. L. (2003). Making the transition to teaching online: Strategies and methods for the First-Time, Online Instructor. Eric. Available online at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED479882 (accessed August, 25 2022).

White, B. (2004). Problem-based learning commentary: Constructivist pedagogy. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 32:120. doi: 10.1002/bmb.2004.494032020329

Yao, Y. (2021). Blended teaching reform of higher vocational education based on addie teaching design model. Int. J. Front. Sociol. 3, 9–13. doi: 10.25236/IJFS.2021.031002

Zhang, J. (2020). The construction of college English online learning community under ADDIE Model. English Lang. Teach. 13, 46–51. doi: 10.5539/elt.v13n7p46

Keywords: online courses, higher education, English literature, instructional design, learning

Citation: Awajan N (2022) Increasing students’ engagement: The use of new instructional designs in English literature online courses during COVID-19. Front. Educ. 7:1060872. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1060872

Received: 03 October 2022; Accepted: 31 October 2022;

Published: 15 November 2022.

Edited by:

Amer Alaya, British University in Dubai, United Arab EmiratesReviewed by:

Mohamed Haffar, University of Birmingham, United KingdomAli Alalwan, Qatar University, Qatar

Copyright © 2022 Awajan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nasaybah Awajan, bmF3YWphbkBtZXUuZWR1Lmpv; orcid.org/0000-0002-5818-4813

Nasaybah Awajan

Nasaybah Awajan