- 1Department of Psychology and Human Development, Institute of Education, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- 2School of Psychological, Social and Behavioural Sciences, Coventry University, Coventry, United Kingdom

- 3School of Education, University of Buckingham, Buckingham, United Kingdom

The transition to university is a time of great change. A recent literature has shown that adaptability (a personal resource) and social support (a conditional, situational resource) are associated with psychological wellbeing and distress among university students. However, the precise nature of these relations are unclear and there is a paucity of work investigating whether adaptability and social support are predictive of psychological wellbeing and distress over longer periods of time. In the present study, first-year university students (N = 411), were surveyed for their adaptability, social support, and psychological distress, and were then re-assessed for their psychological wellbeing and distress 1 year later. A series of moderated regression analyses, revealed that adaptability and social support were independent predictors of psychological distress concurrently, and psychological wellbeing 1 year later. Adaptability, but not social support, was also found to predict psychological distress 1 year later. No interaction effects were observed. The findings demonstrate the importance of adaptability (and social support to a lesser extent) in predicting psychological wellbeing and distress among university students both at course commencement, but also over the course of their studies 1 year later.

Introduction

The transition to tertiary or higher education (referred to as university from hereafter) is a time of great change. For example, Holliman et al. (2020) argue that this transition often involves a change in locality (e.g., many reside in university halls of residence), social networks (e.g., older ties may be broken, and new relationships forged), a change of subject focus and depth (i.e., engagement with subjects not offered previously and taught at a higher level), as well as increasing demands for independence, autonomy, and personal responsibility (not exhaustive). If not managed effectively, these changes (demands) threaten to negatively impact upon students’ psychological wellbeing and distress, which are reportedly considered a major concern in this population (Office for National Statistics, 2020).

In the present study, we explore the contribution of two protective factors (resources) that have begun to receive some attention in discussions of the transition to university (see Holliman et al., 2021, 2022): “adaptability” (a personal resource, referring to one’s capacity to adjust in situations of change, novelty, and uncertainty: Martin et al., 2012) and “social support” (a conditional, situational resource, referring to one’s perceived support from those within their social network: Slotkin et al., 2012). To extend on existing work, we examine whether adaptability and social support are predictive of wellbeing outcomes concurrently, but also over an extended period of time, 1 year later. Moreover, given the complexities surrounding the construct of “wellbeing” (Buzzai et al., 2020), and inspired by the writing of Hone et al. (2014), we incorporate measures of both mental health (e.g., linked to anxiety and depressive symptoms) and mental wellbeing.

Conservation of resources

In the Conservation of Resources (COR) model (see Hobfoll, 2001), it is posited that individuals can be protected from stress via at least two resources: those within the individual (i.e., their personal resources) and those within their social environment (i.e., the conditions or situations surrounding them)—see Hall et al. (2006), for a discussion and evaluation of conservation of resources theory. In line with other recent work in this area (e.g., Holliman et al., 2021, 2022), we consider adaptability to be a “personal” resource and social support to be a conditional, situational resource.

Adaptability, as a construct, is firmly rooted in a number of theoretical frameworks, which emphasize the importance of adjusting to changes in one’s environment via self-regulatory processes (see Holliman et al., 2020, for greater conceptual discussion of adaptability and its location within theoretical frameworks and traditions). This is where cognitions and behaviors (as well as emotions) are monitored, controlled, and directed, and sometimes adjusted/modified to help deal more effectively with the environment (see Zimmerman, 2002; Winne and Hadwin, 2008). A developing literature has shown adaptability to be associated with psychological wellbeing and distress among university students from different backgrounds, including home UK students (Holliman et al., 2021), Chinese international students at UK universities (Holliman et al., 2022), and students studying in non-UK countries, such as China (Zhou and Lin, 2016).

Social support refers to one’s subjective awareness of assistance and support offered within one’s social environment (Slotkin et al., 2012). It has been argued that social support may act as a buffer (Dollete and Phillips, 2004) and offer protection against stress. It may also support the effectiveness of coping strategies (Lakey and Cohen, 2000) and minimize the impact of negative life events (Cohen and Wills, 1985). It follows that social support has been found to be associated with wellbeing outcomes among college (e.g., Berndt, 1989) and university samples (e.g., Yildiz and Karadaş, 2017). In relation to the COR model (Hobfoll, 2001), social support may also help protect the individual from losing personal resources (e.g., Hobfoll et al., 1990): therefore, it seems plausible that relations between adaptability and wellbeing outcomes might be moderated by social support. However, the evidence for this moderation effect is mixed, with some studies reporting significant moderating effects (e.g., Zhou and Lin, 2016; Holliman et al., 2022) and others not (e.g., Holliman et al., 2021).

The present study

In sum, the resources of adaptability and social support are likely to impact upon wellbeing outcomes among university students, although only a sparse literature has investigated this. There are at least two further issues in the current literature, that are addressed in the present study: (1) as the literature yields mixed results regarding the moderating effect of social support, further research is warranted to investigate independent and moderating effects (of social support) in relation to wellbeing outcomes; and (2) prior work in this area (on adaptability, social support, and wellbeing) has almost exclusively utilized concurrent designs (with the exception of Zhou and Lin (2016), who used a lagged design with a 1-month interval), which are insufficient for establishing longer-term effects on psychological wellbeing and distress. We therefore examine whether adaptability and social support are predictive of wellbeing outcomes currently, but also over an extended period of time, 1 year later.

There were two major research questions:

1. Do adaptability and social support contribute significantly, and independently, to psychological wellbeing outcomes concurrently, and 1 year later?

2. Is there an interaction effect between adaptability and social support on psychological wellbeing outcomes concurrently, and 1 year later; specifically, is there a moderating role of social support?

Method

Participants and procedure

All participating students in this study (N = 411) were recruited from a single higher education institution (university) in the West Midlands, UK. Students were included from 31 undergraduate courses based in the Faculty of Health and Life Sciences. Approximately three-quarters of the sample were female (74%; n = 303), students were aged between 17 and 50 years (M = 19.89, SD = 3.65), and 42 students (10%) disclosed some form of disability. Most participating students were from the UK (63%; n = 259), followed by Portugal (6%; n = 26), Poland (4%; n = 17), and Romania (3%; n = 12). The ethnic background of most students was “White British” (49%; n = 203), followed by “Black or Black British–African” (10%; n = 42), “Asian or Asia British–India” (9%; n = 38), and “Asian or Asia British–Pakistani” (5%; n = 22).

Ethical approval was obtained by the University’s Research Ethics Committee and followed the Code of Ethics and Conduct set out by the British Psychological Society. The study was advertised by Course Teams. Students who were interested in taking part completed the survey during a campus-based lecture (92%; n = 377) or online (8%; n = 34), in the first semester of their studies. Information sheets and informed consent forms were provided, which clarified the aims and nature of the research, what was involved in participation, and made students fully aware of their rights, i.e., to anonymity, confidentiality, and withdrawal. Students’ course and demographic details were extracted from the University Records System and/or provided by the University’s Planning and Performance Team. One year later, at the end of Year 1 of their studies, participating students were re-contacted via email and invited to complete some follow-up questionnaires that were designed to measure psychological wellbeing. Note, fewer participants provided data 1 year later (N = 72), and this attrition is addressed in both the “Results” and “Discussion” section. Participants were debriefed at the end of the study and signposted to relevant university support (e.g., welfare services).

Measures

Measures at baseline

Adaptability

The Adaptability Scale (Martin et al., 2013) provided a measure of students’ cognitive, behavioral, and emotional adaptability. Participants responded to 9 items (e.g., “I am able to revise the way I think about a new situation to help me through it”) using a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was 0.85.

Social support

The Instrumental Support Survey (Slotkin et al., 2012) provided a measure of students’ perception that people in one’s social network are available to provide material or functional aid in completing daily tasks, if needed. Participants responded to 8 items (e.g., “There is someone around to help me if I need it”) using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was 0.93.

Psychological distress

The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) (Kessler et al., 2002) provided a measure of students’ general level of psychological distress, which can be used to identify symptoms of anxiety and depression. Participants responded to items 10 items (e.g., “During the last 30 days, about how often did you feel depressed?”) using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time). Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was 0.91.

Measures at the end of Year 1

At the end of Year 1, we measured students’ psychological distress via the aforementioned Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) (Kessler et al., 2002)—Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was 0.81—along with one other, alternative measure of psychological wellbeing (see below), which was again selected based on its credibility and age-appropriateness.

Flourishing

The Flourishing Scale (Diener et al., 2009) provided a measure of students’ self-perceived success and psychological wellbeing linked. Participants responded to 8 items (e.g., “I am engaged and interested in my daily activities”) using a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was 0.72.

Results

Descriptive statistics

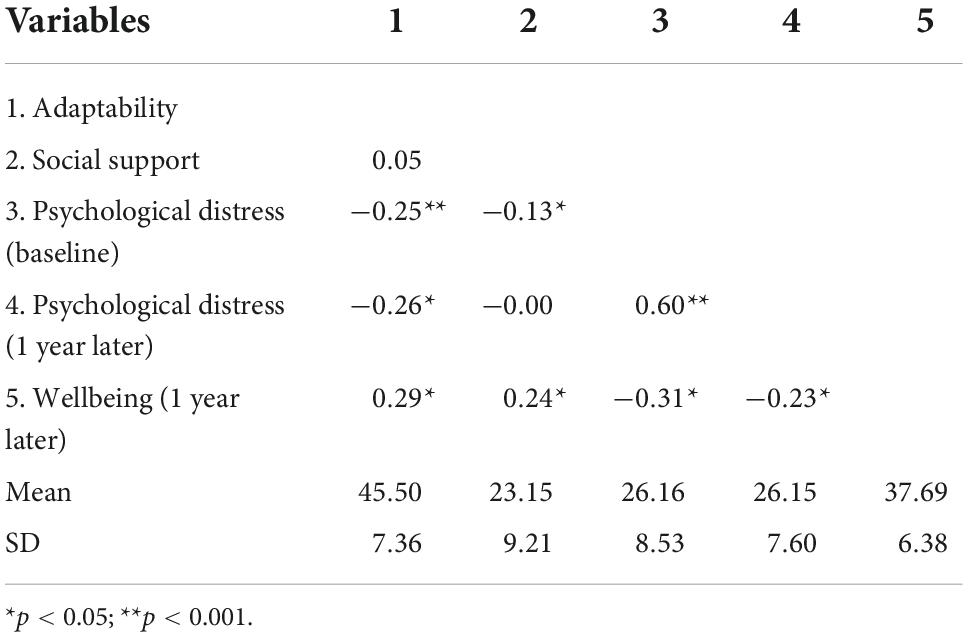

Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations among the key variables are presented in Table 1. As indicated, adaptability and social support were significantly negatively associated with distress at baseline. However, only adaptability was significantly related to distress 1 year later. Both adaptability and social support were significantly positively related with flourishing (wellbeing) 1 year later. Mann–Whitney U tests revealed no significant differences in age (U = 11,087, p = 0.26), adaptability (U = 10,182, p = 0.07), social support (U = 10,407, p = 0.17), or distress (Time 1) scores (U = 11,867.5, p = 0.77) by attrition group (completed only baseline survey; completed both surveys).

Moderated regression analyses

All regression assumptions for this dataset were met for each model. Moderated regression analyses were conducted to examine social support as a moderator of the relationship between adaptability and psychological wellbeing outcomes (wellbeing and distress), respectively. The total scores of the key predictor variables (i.e., Adaptability) and the moderator (i.e., social support) were first mean-centered and an interaction term computed by multiplying the centered predictors (Aiken and West, 1991).

Distress at baseline

It was found that there was a significant negative relationship between adaptability (β = −0.25, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−0.39, −0.17]), and social support (β = −0.11, p < 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.19, −0.02]), on psychological distress. There was no significant interaction effect observed (β = 0.02, p = 0.53, 95% CI = [−0.00, 0.01]). The variance explained by the predictors was 8%.

Distress 1 year later

It was found that there was a significant negative relationship between adaptability (β = −0.28, p < 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.57, −0.04]) on psychological distress 1 year later. However, there was no effect for social support (β = −0.06, p = 0.59, 95% CI = [−0.25, −0.14]) or an interaction effect observed on psychological distress (β = 0.18, p = 0.14, 95% CI = [−0.05, 0.00]). The variance explained by the predictors was 10%.

Flourishing

It was found that there was a significant positive relationship between adaptability (β = 0.29, p < 0.05, 95% CI = [0.06, 0.49]), and social support (β = 0.24, p < 0.05, 95% CI = [0.00, 0.32]), on psychological wellbeing. However, there was no interaction effect observed (β = −0.00, p = 0.95, 95% CI = [−0.02, 0.02]). The variance explained by the predictors was 14%.

Discussion

The present study examines the influence of adaptability and social support on university students’ psychological wellbeing concurrently, and over the course of their studies, 1 year later. This therefore extended on prior concurrent studies (e.g., Holliman et al., 2021, 2022) and those utilizing shorter longitudinal approaches (e.g., Zhou and Lin, 2016). In line with prior work, we found that adaptability and social support were independent predictors of psychological distress concurrently, and psychological wellbeing 1 year later. The findings, therefore, provide support for the COR theory (see Hobfoll, 2001), which signifies the importance of both personal resources (e.g., adaptability) and conditional, situational resources (e.g., social support) to protect oneself against current and future stress (Hobfoll, 2001; Dollete and Phillips, 2004). It was observed that individuals who were higher in the resources of adaptability and social support were less likely to experience distress and more likely to experience positive psychological wellbeing.

Interestingly, adaptability was a stronger predictor than social support in each case, and adaptability (but not social support) was also found to predict psychological distress 1 year later. This finding corroborates the results reported in Holliman et al. (2021) where adaptability (relative to social support) was found to be more important in relation to wellbeing outcomes in university students (higher education) compared with earlier education levels, i.e., those in further (college) education. To explain this finding—the increasing importance of adaptability (relative to social support) in relation to wellbeing outcomes at university—perhaps the increasing demands for independence, autonomy, and personal responsibility at university coupled with the change in social networks (Holliman et al., 2020) mean that students need to draw upon personal resources (adaptability) rather than conditional, situational resources (social support), which are less readily available, in order to reduce stress and promote positive psychological wellbeing. Further research is warranted to test this novel finding. Taken together, it can be seen that adaptability (relative to social support), is particularly important in relation to wellbeing outcomes among university students.

Moreover, we found no evidence of a moderation effect of social support. This seems to conflict with the suggestion that social support may help protect individuals from losing personal resources (e.g., Hobfoll et al., 1990) as well as the studies where a moderating role of social support was observed (e.g., Zhou and Lin, 2016, Holliman et al., 2022). Instead, our findings were in line with Holliman et al. (2021) who found no moderation effects. Taken together, the findings suggest the importance of adaptability (and social support to a lesser extent) in predicting psychological wellbeing and distress among university students both at course commencement, but also over the course of their studies 1 year later.

Limitations and further directions

There are some limitations of the study that will now be acknowledged. First, the concurrent sample in this study was 411, which is well above the 99 used in Zhou and Lin (2016) and the 102 used in Holliman et al. (2021); however, there was a significant level of attrition resulting in a depleted sample size. Although our analyses revealed no main effect of attrition group on any of the measures at baseline, future research should explore relations between the variables in this study, using longitudinal designs with larger samples. Second, and not unlike existing work in this area, we utilized quantitative methodology, which is insufficient for understanding in-depth students’ experiences of adaptability, social support, and wellbeing (qualitative approaches may be fruitful). Third, all the constructs in this study were measured via self-report scales. As such, there is the potential risk of inaccurate or biased responding (Podsakoff et al., 2012), although this could arguably be leveled at most other studies in this area. Finally, although significant variance in psychological distress and wellbeing was explained by the predictors in this study, it ranged from just 8 to 14%. Thus, other variables not included in the model are likely to be of importance. For example, this research focused on individual-level variables and did not consider variables beyond the individual, such as teacher influence or institutional practices (see Gravett et al., 2020).

Conclusion

The present study showed that among university students, where there are concerns about the management of stress and their overall wellbeing, resources such as adaptability and social support are of importance. The resources seem connected to wellbeing not only concurrently, but also over the course of their studies 1 year later. These findings have important implications for educators and researchers, who wish to identify protective factors for intervention efforts, mitigate stress within university contexts, and improve the overall student experience.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to AH, YS5ob2xsaW1hbkB1Y2wuYWMudWs=.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Faculty Research Ethics Committee (REC) at Coventry University. This adheres with the British Psychological Society’s Code of Ethics and Conduct. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AH and DW contributed to the conception and design of the study and organized the data collection. DW performed the statistical analysis. AH wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors wrote the sections of the manuscript, contributed to the manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aiken, L. S., and West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Berndt, T. J. (1989). “Obtaining support from friends during childhood and adolescence,” in Children’s social networks and social supports, ed. D. Belle (New York, NY: Wiley), 308–331.

Buzzai, C., Sorrenti, L., Orecchio, S., Marino, D., and Filippello, P. (2020). The relationship between contextual and dispositional variables and well-being and hopelessness in school context. Front. Psychol. 11:533815.

Cohen, S., and Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 98, 310–357. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.533815

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., et al. (2009). New measures of well-being: Flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc. Indic. Res. 39, 247–266. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

Dollete, S., and Phillips, M. (2004). Understanding girls’ circle as an intervention on perceived social support, body image, self-efficacy, locus of control and self-esteem. J. Psychol. 90, 204–215. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-2354-4_12

Gravett, K., Kinchin, I. M., and Winstone, N. E. (2020). Frailty in transition? Troubling the norms, boundaries and limitations of transition theory and practice. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 39, 1169–1185.

Hall, B. J., Rattigan, S., Walter, K. H., and Hobfoll, S. E. (2006). “Conservation of resources theory and trauma: An evaluation of new and existing principles,” in Stress and anxiety—application to health, community, workplace, and education, ed. P. Buchwald (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholar Press Ltd.), 230–250. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2020.1721442

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 50, 337–421.

Hobfoll, S. E., Freedy, J., Lane, C., and Geller, P. (1990). Conservation of social resources: Social support resource theory. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 7, 465–478. doi: 10.1111/1464-0597.00062

Holliman, A. J., Collie, R. J., and Martin, A. J. (2020). “Adaptability and academic development,” in The encyclopedia of child and adolescent development, eds S. Hupp and J. D. Jewell (New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.). doi: 10.1177/0265407590074004

Holliman, A. J., Waldeck, D., Jay, B., Murphy, S., Atkinson, E., Collie, R. J., et al. (2021). Adaptability and social support: Examining links with psychological wellbeing among UK students and non-students. Front. Psychol. 12:636520. doi: 10.1002/9781119171492.wecad420

Holliman, A., Waldeck, D., Yang, T., Kwan, C., Zeng, M., and Abbott, N. (2022). Examining the relationship between adaptability, social support, and psychological wellbeing among Chinese international students at UK Universities. Front. Educ. 7:874326. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.636520

Hone, L. C., Jarden, A., Schofield, G. M., and Duncan, S. (2014). Measuring flourishing: The impact of operational definitions on the prevalence of high levels of wellbeing. Int. J. Wellbeing 4, 62–90. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.874326

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L., et al. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 32, 959–976. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v4i1.4

Lakey, B., and Cohen, S. (2000). “Social support theory and measurement,” in Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists, eds S. Cohen, L. G. Underwood, and B. H. Gottlieb (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 29–52. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702006074

Martin, A. J., Nejad, H. G., Colmar, S., and Liem, G. A. D. (2012). Adaptability: Conceptual and empirical perspectives on responses to change, novelty and uncertainty. J. Guid. Couns. 22, 58–81. doi: 10.1093/med:psych/9780195126709.003.0002

Martin, A. J., Nejad, H. G., Colmar, S., and Liem, G. A. D. (2013). Adaptability: How students’ responses to uncertainty and novelty predict their academic and non-academic outcomes. J. Educ. Psychol. 105, 728–746. doi: 10.1017/jgc.2012.8

Office for National Statistics (2020). Coronavirus and higher education students: England, 20 November to 25 November 2020. London: Office for National Statistics. doi: 10.1037/a0032794

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 63, 539–569.

Slotkin, J., Kallen, M., Griffith, J., Magasi, S., Salsman, J., Nowinski, C., et al. (2012). NIH toolbox technical manual. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Winne, P. H., and Hadwin, A. F. (2008). “The weave of motivation and self-regulated learning,” in Motivation and self-regulated learning: Theory, research, and application, eds D. H. Schunk and B. J. Zimmerman (New York, NY: Routledge), 297–314.

Yildiz, M., and Karadaş, C. (2017). Multiple mediation of self-esteem and perceived social support in the relationship between loneliness and life satisfaction. J. Educ. Pract. 8, 130–139.

Zhou, M., and Lin, W. (2016). Adaptability and life satisfaction: The moderating role of social support. Front. Psychol. 7:1134.

Keywords: adaptability, social support, psychological wellbeing, distress, university, follow-up study

Citation: Holliman AJ, Waldeck D and Holliman DM (2022) Adaptability, social support, and psychological wellbeing among university students: A 1-year follow-up study. Front. Educ. 7:1036067. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1036067

Received: 03 September 2022; Accepted: 25 November 2022;

Published: 07 December 2022.

Edited by:

Charlotte Bagnall, The University of Manchester, United KingdomReviewed by:

Andreja Brajsa Zganec, Institute of Social Sciences Ivo Pilar (IPI), CroatiaMariel Fernanda Musso, Centro Interdisciplinario de Investigaciones en Psicología Matemática y Experimental (CONICET), Argentina

Copyright © 2022 Holliman, Waldeck and Holliman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrew J. Holliman, YS5ob2xsaW1hbkB1Y2wuYWMudWs=

†ORCID: Andrew J. Holliman, orcid.org/0000-0002-3132-6666; Daniel Waldeck, orcid.org/0000-0002-6542-706X

Andrew J. Holliman

Andrew J. Holliman Daniel Waldeck

Daniel Waldeck David M. Holliman

David M. Holliman