- 1Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education, University of Buea, Buea, Cameroon

- 2Department of Educational Foundations and Administration, Faculty of Education, University of Buea, Buea, Cameroon

- 3Department of Curriculum Studies and Teaching, Faculty of Education, University of Buea, Buea, Cameroon

Introduction: Many low-income countries have very high levels of youth unemployment. Self-employment provides one path to economic independence for these youths, but to be successful, they require both technical and entrepreneurial skills. Most youth employment interventions and research have focused on the formal education sector, which has limited the understanding of the role of education in reducing youth unemployment. The role of informal learning opportunities offered by small businesses and micro-enterprises, which constitute one of the largest sectors of the economy in many low-income countries, has been undermined. This study examines the potential of such learning opportunities through a case study of informal apprenticeships in tailoring in Cameroon, Central Africa.

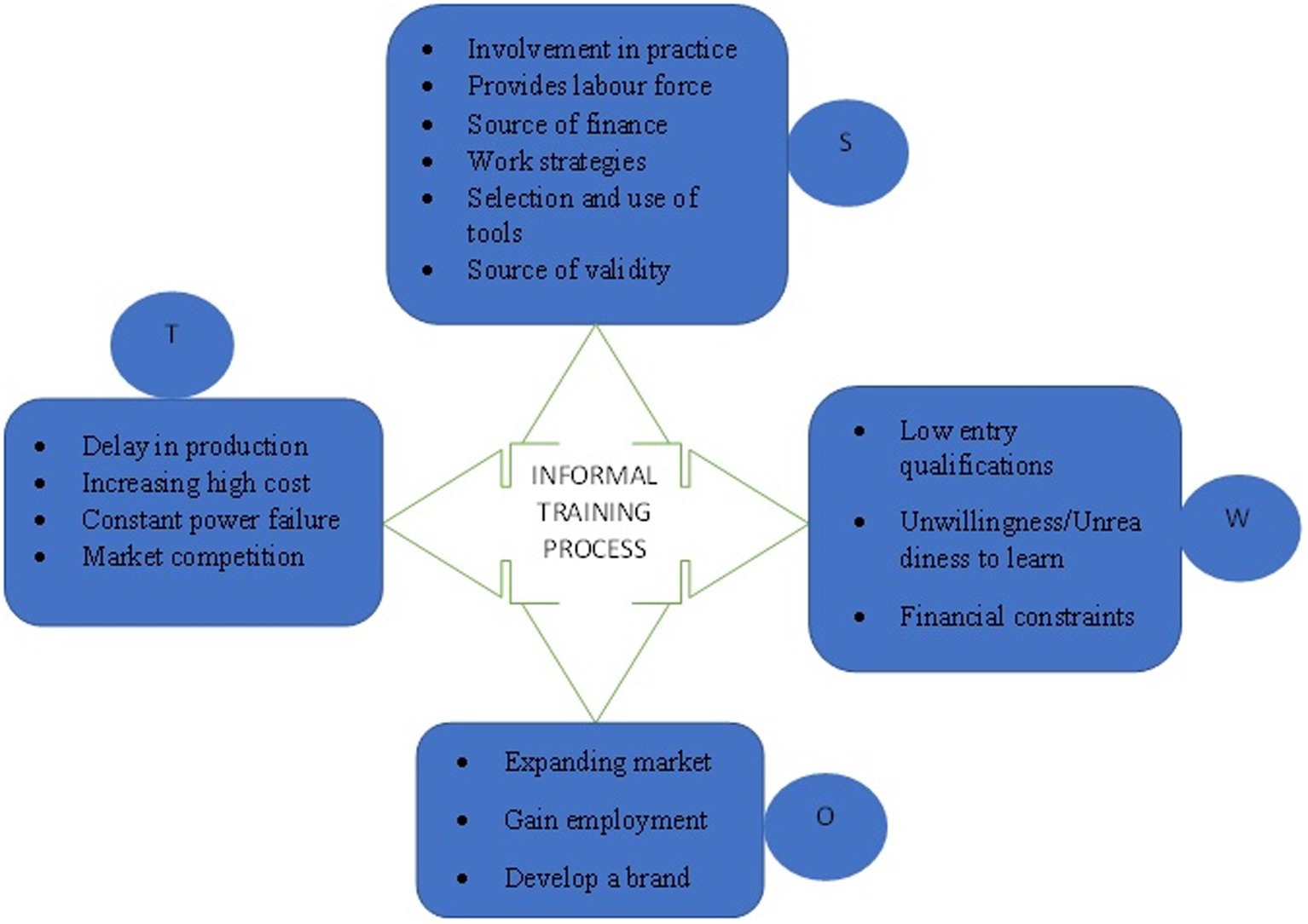

Methods: A Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats analysis drew on the perspectives of both informal trainers (n = 42; 88% women) and apprentices (n = 16; mean age: 22 years; 69% women) in small-tailoring enterprises in the city of Buea. Qualitative data from semi-structured interviews was subjected to a thematic analysis.

Results and discussion: The perceived strengths of informal apprenticeships included developing suitable work strategies, attitudes, technical and entrepreneurial skills in unemployed youth through practice and collaboration with other apprentices. However, participants also identified several weaknesses in informal training, including inadequate access to specialized machines and limitations on training imposed by the poor literacy skills of some apprentices. Most respondents perceived that tailoring provided an opportunity for a lucrative career while meeting their community’s need for appropriate clothing. However, high taxes and constant power failures were identified as threats to the continuing viability of local tailoring. Trainers also noted that few youths were interested in learning the trade. Taken together, the results indicate that the potential for informal vocational training to nurture youths toward developing their own enterprise would be strengthened if training included basic literacy skills, building self-confidence, strategies to raise and manage capital and the production of attractive designs to match their competition.

Introduction

Very high levels of youth unemployment are a longstanding obstacle to individual and community development as well as political stability in many low and middle-income countries. Staggering statistics indicate that 267 million young people aged 15–24 worldwide are not in employment, education, or training (Gomis et al., 2020, p. 14). Given that the absolute population size of the 15–24 age group is projected to grow strongly in Africa, the creation of sufficient decent job opportunities is one of the most pressing challenges in the region (Gomis et al., 2020, p. 14). Young people in Africa desire to earn jobs that can sustain their livelihoods. For instance, in a recent survey of more than 4,500 youth across 15 Sub-Saharan African countries, participants identified the creation of new, well-paying jobs as the highest priority for the future progress of Africa (Ichikowitz Family Foundation, 2022). In the current absence of these jobs, 78% of participants planned to start a business in the next 5 years. Such ventures are more likely to be successful if young people can acquire training in a profession, trade, and/or basic business and entrepreneurial skills.

Self-employment provides one path to economic independence for youth, but to be successful, they require both technical and entrepreneurial skills. Education is the leading tool for transforming the lives of individuals and society by facilitating the acquisition of the skills, knowledge, and attitudes that will help people live sustainable lives. Most youth employment interventions and research have focused on the formal education sector, which has limited capacity in most low and middle-income countries. In contrast, opportunities for informal learning offered by small businesses and micro-enterprises are typically overlooked, even though they constitute one of the largest sectors of the economy in many low- and middle-income countries. Data from the International Labor Organization (ILO) indicates that 90% of the micro and small enterprises worldwide are in the informal sector, and this may offer particular opportunities to youths in sub-Saharan Africa, which hosts about 26% of these workers (International Labour Organisation, 2012). The role the informal sector plays in providing meaningful training and employment has been acknowledged in the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8.3, which aims to “promote development-oriented policies that support productive activities, decent job creation, entrepreneurship, creativity, and innovation, and encourage formalization and growth of micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises, including through access to financial services.” Similarly, SDG 4 equally aims to “substantially increase the number of youth and adults who have relevant skills, including technical and vocational skills, for employment, decent jobs, and entrepreneurship by 2030” (United Nations, 2015, p. 7). These goals highlight the need for contextually relevant vocational and entrepreneurial skills. However, many micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises evade registration and are therefore treated as part of the informal economy (Delmar and Shane, 2004; International Labour Organisation, 2007).

The labor market challenges for young workers point to a need to establish technical and vocational training systems that are tailored to their needs and those of their potential employers (Gomis et al., 2020, p. 44). Training programs to enhance the skills of young men and women can play a positive role as long as they are well designed. The need to foster soft skills has recently been recognized (e.g., IDRC et al., 2016). Youth employment interventions can be distinguished between supply-side and demand-side interventions (Fox and Kaul, 2017). The former focuses on improving the supply of skills to young people by offering training and incentives in the hope that they will become more attractive to potential employers (Ayele et al., 2018). The latter focuses on improving the capacity of employers or industrial sectors so that there will be a higher demand for workers (McKenzie, 2017). The current research focuses on training that is specifically captured by supply-side strategies to address youth unemployment.

Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) is available in most African countries and is being regulated and provided through the public sector, while the role of private sector TVET providers keeps growing (Akoojee, 2016 as cited in Ismail and Mujuru (2020), p. IV). However, available literature on TVET indicates a consensus that TVET is underfunded and is a low priority for African governments. TVET systems in Africa are hampered by the poor quality of training facilities, trainers, equipment, and curricula (Sorensen et al., 2017; Andreoni, 2018; Leyaro and Joseph, 2019). TVET systems that are considered successful require very close collaboration between TVET providers and employers in the private sector. Tripney and Hombrados’ (2013) meta-analysis of the effectiveness of TVET in low- and middle-income countries revealed that the mean effects of completion of a TVET qualification on overall paid employment, formal employment, and monthly earnings from formal employment were small but positive. In contrast, TVET had no effect on earnings from self-employment or weekly hours worked. Formal TVET options will not be able to adequately serve youth at the bottom of the pyramid until the quality and relevance of primary education equips them to continue successfully in secondary schools (Oketch, 2018 p. 206). Therefore, systems and their donors and other partners must develop non-formal and informal learning and training options.

From a review of research on donor-funded training programs by Oosterom (2018) p. 1., there is hardly any evidence that youth employment interventions that seek to improve the supply-side of labor markets by offering skills training have positive results. Instead of creating new jobs, they move some youths to the front of the employment queue at the expense of others. None of the interventions was considered cost-effective. Donor-funded skills development programs vary considerably in terms of duration, scope, and objectives (Ismail and Mujuru, 2020, p. V). Overall, the impact of donor-funded skills development programs on employment is modest but improves if there is a component of workplace-based learning (Datta et al., 2018). Institutions and individuals take an interest in the role of the private sector as a provider of workplace-based learning. However, given the extent of informality in Africa, reference to the private sector may refer largely to the informal sector. This issue is important because a focus on the private sector implies that micro-entrepreneurs operating in the informal sector across Africa may carry the burden of training young people.

Many of the shortcomings of formal training programs and donor-funded short courses do not apply to informal apprenticeships. For youths at the bottom of the pyramid who have failed to make the post-primary learning (Oketch, 2018 p. 197) transition, Non-Formal Education (NFE) could be a remedy if taken seriously at the level of national policy formulation and resourcing, and notably, there is a resurgence of interest in this topic after nearly 40 years of debate and neglect (Britto et al., 2014). Informal or traditional apprenticeships, according to Ismail & Mujuru (2020, p. V), are private arrangements between a master craftsperson and an apprentice. The term is used broadly to refer to various artisans, tradesmen, or entrepreneurs operating in the informal economy. Informal apprenticeships are the primary source of technical and vocational skills development in Sub-Saharan Africa (Palmer, 2017, p. 12). This is because the informal or unregistered economy is responsible for between 80% and 90% of employment in much of Sub-Saharan Africa. These private, informal training modalities vary drastically but typically last from a few months to 3 or 4 years, with a written or verbal agreement between the master and apprentice, and the payment of a fee or payment of reduced earnings to the apprentice while he or she learns (Adams et al., 2013). This training is very relevant to enterprises that take on a learner and is usually more accessible than formal technical and vocational training programs (Palmer, 2017, p. 12).

However, informal apprenticeship systems also have concerns about poor working conditions, long working hours, child labor, and exploitation of workers (International Labour Organisation, 2012; Aggarwal, 2013 as cited in Ismail and Mujuru (2020)), as well as a high dropout rate among apprentices in several countries (Hoffman and Okolo, 2013). Simultaneously, some apprentices in Ghana cannot complete their training because they cannot afford the blessing ceremony that marks the end of the apprenticeship (Schraven, 2013). Similar capacity constraints and gender biases affect the system, and the same types of trade equally emerge in a range of African countries, regardless of wealth. Informal apprenticeships should be upgraded, although this must be done with care to ensure that policy changes lead to improvement rather than the demise of informal apprenticeships (International Labour Organisation, 2012). Enhancing the accessibility and quality of general education is also beneficial, as many informal apprentices are encumbered by poor literacy and numeracy skills.

Informal apprenticeship systems in West Africa are considerably self-regulated, but in many other countries, apprenticeship training in the informal economy is typically much less regulated or organized except through social and cultural norms (Palmer, 2017, p. 12). Palmer (2017), as cited in Oketch (2018 p. 204), discusses several attempts by the Ghanaian government to formalize informal apprenticeships and points to potential unintended ramifications in Ghana and other African countries. This type of training, Palmer (2017, p. 12), argues, does suffer from quality concerns. For example, there is usually a low-quality training environment, the trainer/master-craftsperson is usually untrained in how to teach, and the technologies used are often outdated. Furthermore, skills acquired from informal training (such as informal apprenticeships) are not usually recognized in the formal education system or in the formal economy, limiting the mobility of learners and workers (Glick et al., 2015). To solve this problem, assessment and certification of informal apprenticeships can help the market sort between good and bad training for apprenticeships (Adams et al., 2013, p. 13 as cited in Palmer, 2017 p. 33) and strengthen and formalize informal apprenticeships. In Malawi and Tanzania, informal apprentices can acquire competency-based skills certifications (World Bank, 2017).

Across Africa, there are concerns that traditional apprenticeships may not actually be improving labor market outcomes for youths (Axmann and Hoffman, 2013; Filmer and Fox, 2014 as cited in Ismail and Mujuru, 2020, p. 17). This trend occurs because of their reliance on outdated technology and the lack of standards and quality assurance (Hardy et al., 2019). Furthermore, low levels of literacy and education may undermine the potential of apprenticeships to foster skills development (Adams et al., 2013). Existing programs would need to be reviewed to assess whether there are barriers or enabling conditions to facilitate the role of TVET in supporting learning for those at the BoP [bottom of the Pyramid] (Oketch, 2018 p. 205).

In most LMICs, there remains a serious lack of reliable information on skills in the informal economy that hinders policymakers’ full understanding of the status quo and therefore how to design reforms and interventions to strengthen skills access, acquisition, and utilization in the informal economy (Palmer, 2017 p. 14). This gap in knowledge is addressed in this study using a case study of informal apprenticeship in tailoring in Cameroon, Central Africa. The informal sector in Cameroon has been the main source of employment for almost 9 out of 10 workers (89.5%), with 86% of males and 93.2% of females (International Labour Organization (ILO), 2018 p. 10). Cameroon envisages improving the value and relevance of vocational training in line with the demands of the labor market and providing universal access to apprenticeships by 2035 (Cameroon’s Growth and Employment Strategy Paper, 2009 p. 154). Apprenticeships have long remained informal in Cameroon, mainly because of the lack of a strong legal framework to define the partnerships between businesses and training centers. However, the government has made progress by recognizing apprenticeships as a form of vocational training in Law No. 2018/010 of July 18, 2018, although the organizing guidelines have yet to be defined (International Labour Organization (ILO), 2018 p. 29). Traditionally, apprenticeships in Cameroon have consisted of on-the-job training. Most workers in the informal sector (66.9%) learn through hands-on practice (Ngathe, 2015). However, the quality of training in TVET in Cameroon suffers from a lack of specialized equipment and materials (International Labour Organization (ILO), 2018 p. 42). Additionally, the lack of a standard certification criteria in the informal apprenticeship system limits apprentices’ access to opportunities backed by certification. Cameroon does not have a structure responsible for the recognition of formal and informal credentials. The ministries in charge of TVET each define their own training assessment and certification standards (International Labour Organization (ILO), 2018 p. 43).

The informal sector in Cameroon provides training in a range of trades and crafts, one of which is tailoring. It is very common to see a couple of tailoring workshops in every Cameroonian neighborhood. Tailoring encompasses the process of designing and sewing all forms of clothing for men, women, and children. It is a trade that attracts both male and female apprentices. The spirit of uniformity in attire is highly valued by Cameroonians and indicates a spirit of togetherness. People constantly stitch uniforms for school, family, cultural, religious, and social associations, events, and a lot more. As a result, tailors are usually engaged in sewing the required clothes for people. Tailoring is a source of employment and livelihood for many Cameroonians.

Trainers in tailoring are persons who are considered to have gone through and completed the tailoring apprenticeship process, acquired the skills and opened a tailoring workshop of their own. A tailoring workshop at its minimum in the Cameroonian context is a space usually a room (size ranging from 9 to 12 meters squared) that has at least a sewing machine, a flat surface or table for cutting fabric and ironing and other basic sewing tools such as sewing thread, needles, seizors, card board papers and a few stools for the clients and workers to sit. Workshops considered to be more advanced have a bigger room space (16 m squared and above) or have more than one room where one is often used to show case designs and receive clients and the other basically for sewing. Some advanced workshops have two or more sewing machines. Some have both the manual and electronic sewing machines that only functions with electricity. Very few trainers have specialized machines such as zigzag, press-button, marking in their workshops. There are workshops specialized in doing just zigzag, others in press button and some in marking. They work in partnership with tailoring workshops. It is very common to see tailors and apprentices moving to and back from other workshops with specialized machines to get the needed services for the completion of a dresses or garments sown.

Trainees are the apprentices who are recruited to learn the art of tailoring. Training is experiential and done practically through apprenticeship where the trainees observe, ask questions, run errands, do assignments and engage in manipulating tools such as measuring tape, needles, thread, iron, paddle sewing machines under careful instructions and supervision by the trainer and other more experienced apprentices if available. Training is organized from simple to complex as trainees at the beginning are given very basic task such as fitting buttons, machine paddling, seizors and tape usage to more advanced task like ironing, fabric cutting to actually sewing from simple to complex designs as they gain experience. There is a shared belief in the Cameroonian context that apprenticeship training is for children who cannot perform well in regular formal education. It is thus considered an avenue where children who are slow in academics can excel and sustain their livelihood. Some apprentices are usually nannies and house helps in the homes where they live. They are often sent to learn tailoring as a social contract where the employer (mother/father/caretaker) funds their training while they train and work as nanny and or house help where they live.

Given that training in this field is mostly informal, the elements in the training process that enhance or hinder sustainable livelihoods are empirical. The study thus uses the SWOT analysis to examine elements of sustainable livelihood in the training. The SWOT acronym stands for strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (e.g., Kotler and Armstrong, 2017). A SWOT analysis focuses on the internal capabilities and resources that support (strengths) and internal limitations that obstruct (weaknesses) the organization in achieving its aims, and aspects and trends of the external environment may support (opportunities) or undermine (threats) the organization’s future performance. SWOT analyses have remained a business tool in widespread use. However, more recently, the SWOT analysis format has been applied in a wide variety of contexts, including explorations of new applications of technology (e.g., use of virtual reality technology by athletes: During et al., 2018), and planning the implementation of new health interventions (e.g., Marx and More, 2022). In most analyses, judgments about strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats are based on either a review of existing scholarly literature (e.g., Tinga et al., 2020), sometimes combined with a review of government policy documents (e.g., Sharma and Pardeshi, 2021), or on newly collected data on the views of experts (e.g., Robert et al., 2014). In cases in which SWOT analyses have been based on the views of stakeholders, end users have rarely been included (e.g., Marx and More, 2022). For example, Zhou et al. (2021) sought the views of hospital administrators and medical staff on a proposed change in the location of treatment for patients with COVID-19, but did not seek the views of patients with COVID or their families. The exceptions, in which a SWOT analysis is based on the perceptions of end-users, may be referred to as “participatory SWOT analyses” (e.g., Nowreen et al., 2022).

A relatively small number of researchers have applied SWOT analyses to training programs. Most of these have focused on formal education provided in higher education courses (e.g., Wait and Govender, 2019) or continuing development programs for participants who have already completed professional training (Manzini et al., 2020). Most of these studies are also based on literature reviews or the views of experts. For example, recent analyses on the integration of virtual reality into training programs for fire-fighters (Engelbrecht et al., 2019) and the renewal of the curriculum for pediatric anesthesiology students (Ambardekar et al., 2022) were based on a literature review and a Delphi study of experts, respectively. The first did not consult firefighters or fire survivors; and the second did not consult pediatric anesthesiology students or new graduates, or patients and their families. Most published SWOT analyses of training programs that have sought the perspectives of trainers and/or trainees have focused exclusively on one of these (e.g., Topuz et al., 2021) or have pooled responses, with the result that any differences in the perspectives of trainers and trainees are obscured (e.g., Manzini et al., 2020).

Knowledge about informal apprenticeships held by experts in formal vocational training and government officials in government ministries for training and employment is limited. Also, the absence of existing literature on informal-tailoring apprenticeships in low-income countries precipitates the need to adopt a participatory SWOT analysis approach that seeks to give voice to the distinct perspectives of the trainers and trainees who are directly involved. This approach also offers the possibility of gaining rich information about trainers’ and trainees’ evaluations, perceptions, and experiences.

Aim

The study therefore aims broadly to provide insight into the role that informal apprenticeships play in addressing high levels of youth unemployment in low- and middle-income countries through a participatory SWOT analysis of informal-tailoring apprenticeships in Cameroon. Specifically, the study examines the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of informal apprenticeship in tailoring that enhance, hinder, foster, and retard, respectively, the tendency for youths to attain sustainable livelihoods.

Materials and methods

A qualitative approach that adopted the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Study Guidelines was used. Both groups of participants completed semi-structured interviews that lasted between 30 and 50 min in the participants’ workshops. The tailoring workshops were located in Buea, a city with a population of ~300,000 people in the English-speaking South-West region of Cameroon. Many tailoring workshops were in the neighborhood of the University of Buea (Molyko) as it provided access to the university staff and students who constituted their customers.

The data collection procedure lasted 2 months (03/03/2022–30/04/2022). The participants were interviewed while at work. Some trainers were interviewed in the presence of the trainees while permission was sought from the trainers to interview their trainees out of earshot. This was to ensure trainees’ freedom to share their experiences and express their views without the trainer’s influence. Prompt questions included: “How is your training organized?,” “What do you expect from your apprentices?,” “Who is the leader/coordinator and why?” “What are some things you think distort the progress of the business?” “What factors beyond your control impede your operations in the trade?” and “What can be done to improve the situation?” These sparked conversations in which follow-up questions could gain in-depth information on their experiences. The same questions were asked to trainers and trainees so as to capture and triangulate their different experiences. Interviews were recorded and field notes were made as a backup. Data collection proceeded until the themes emerging from both the female and male trainers and trainees became saturated.

All authors conducted the interviews independently (3 PhD holders and 1 PhD student) to cover a wider niche of the Buea Municipality. Three of the four authors were female. In terms of occupation, 2 of the interviewers were university lecturers and the others were secondary school teachers. Every author interviewed at least 10 trainers and four trainees in the study area.

Participants and sample

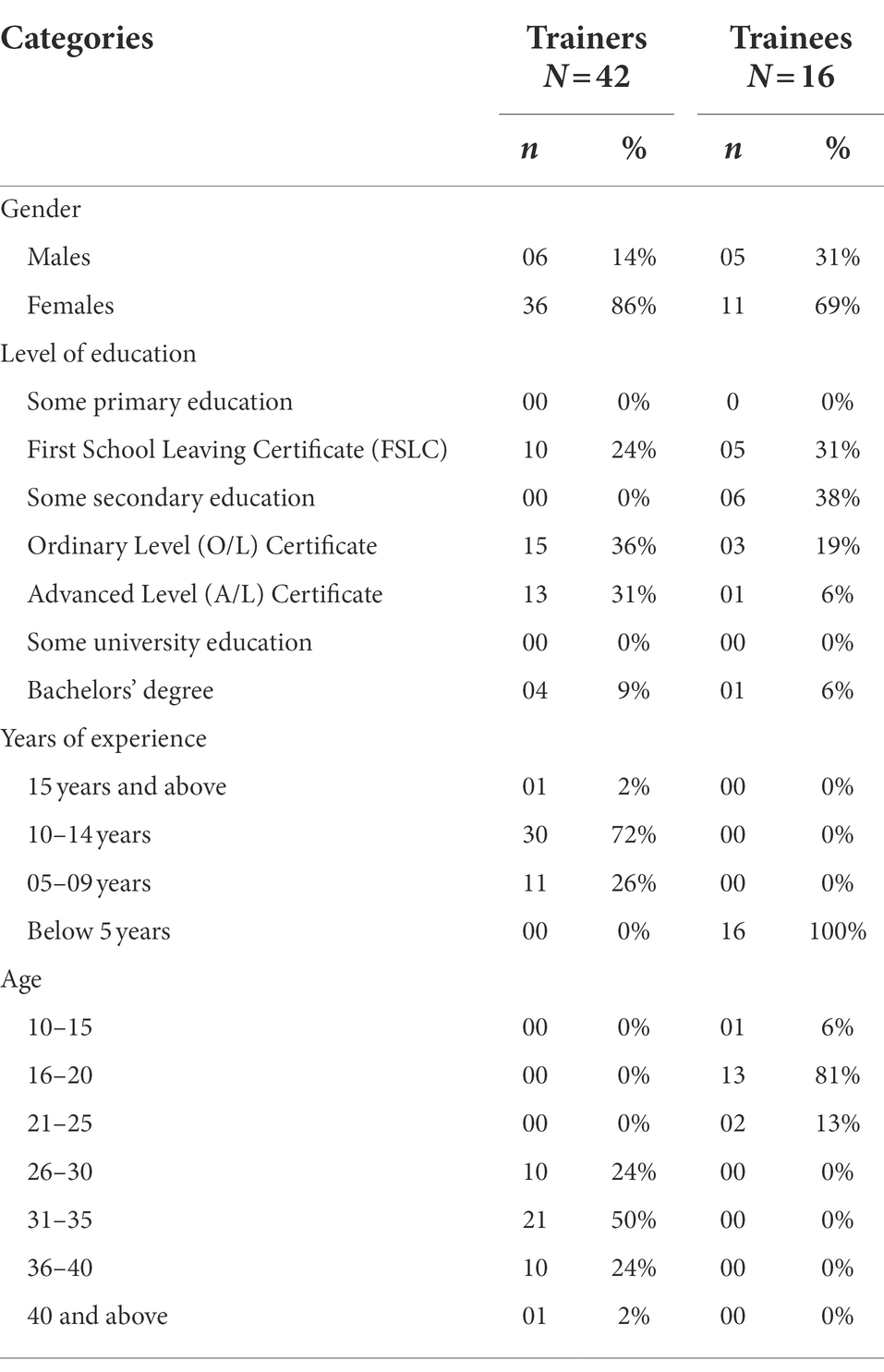

Participants’ demographic data is presented in Table 1. The sample included tailors who had apprentices (n = 42) and apprentices in tailoring (n = 16) recruited using a snowball sampling procedure. Very few tailoring workshops at the time of data collection had trainees, reason why the sample of trainers outnumbered those of the trainees. However, they were many workshops with trainers that had previously trained so many trainees. Recruitment targeted tailors who owned a workshop that had been operating for a minimum of 5 years. However, the majority of the trainers in the sample had spent more than 10 years (72%) in the trade. This is because newly established businesses are unlikely to have completed the training of their apprentices. Also, only trainees who had spent at least a year in the workshop were recruited for the interview, given that they must have had some level of experience. The sample size went up to 42 trainers and 16 trainees to ensure that a data saturation level was reached for all categories (male and female trainers and trainers in workshops that focused on garments for males and those that focused on dresses for females) involved. However, in both categories, most of the participants in our study were females (trainers = 86% females; trainees = 69% females). The majority of the trainers had earned higher certificates compared to their trainees, as the data indicated that more of the trainers had earned an Ordinary Level Certificate (36%) followed by an Advanced Level Certificate (31%). Instead, more trainees indicated having some level of secondary education even though they did not earn the certificate, followed by a FSLC (31%). According to the Cameroon educational system, formal education begins with primary education, which lasts for 6 years, and successful candidates will earn a FSLC. FSLC holders can now proceed to secondary schools where they can earn an O/L after 5 years of study, making them eligible to pursue high school education for another 2 years to earn an A/L certificate. This certificate qualifies them to enter higher education institutions where they can earn diplomas and degrees. Overall, our data indicates that most of the participants in this sector had higher levels of education. Trainers were also older than trainees, as all trainers were between the ages of 26–40 and above, while trainees were aged between 10 and 25.

Data analysis

Interview responses were transcribed before being analyzed through a qualitative thematic analysis and a quantitative content analysis. The recordings were listened to and the transcripts examined multiple times. In the course, initial codes were generated, emerging themes were sought for and reviewed. Three of the authors participated in assigning codes and generating themes that emerged from the data. Although grounding was done to indicate the strength of some emerging themes, the focus was on identifying and describing the themes as they emerged from the data. Interview transcripts for trainers were analyzed differently from those of trainees to capture their unique experiences. However, data for both trainers and trainees were compared and presented together to triangulate the findings. The themes were classified and presented concerning the SWOT. Typical responses reflecting the emerging themes were placed word for word while explaining the experiences. A few interviews were conducted in the pidgin Language (lingua franca of the English-speaking regions of Cameroon). A few typical responses from such cases were translated and presented in English.

Results

Content and thematic analysis of the interviews with trainers and trainees revealed several strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats to the sustainable livelihoods of unemployed youths engaged in informal training in tailoring workshops. Slight variations were found in the responses as revealed in the groundings. However, the dominant focus here was on the emergent themes rather than on the frequency of times that each theme reoccurred.

Strengths of informal training and sustainable livelihoods of unemployed youths

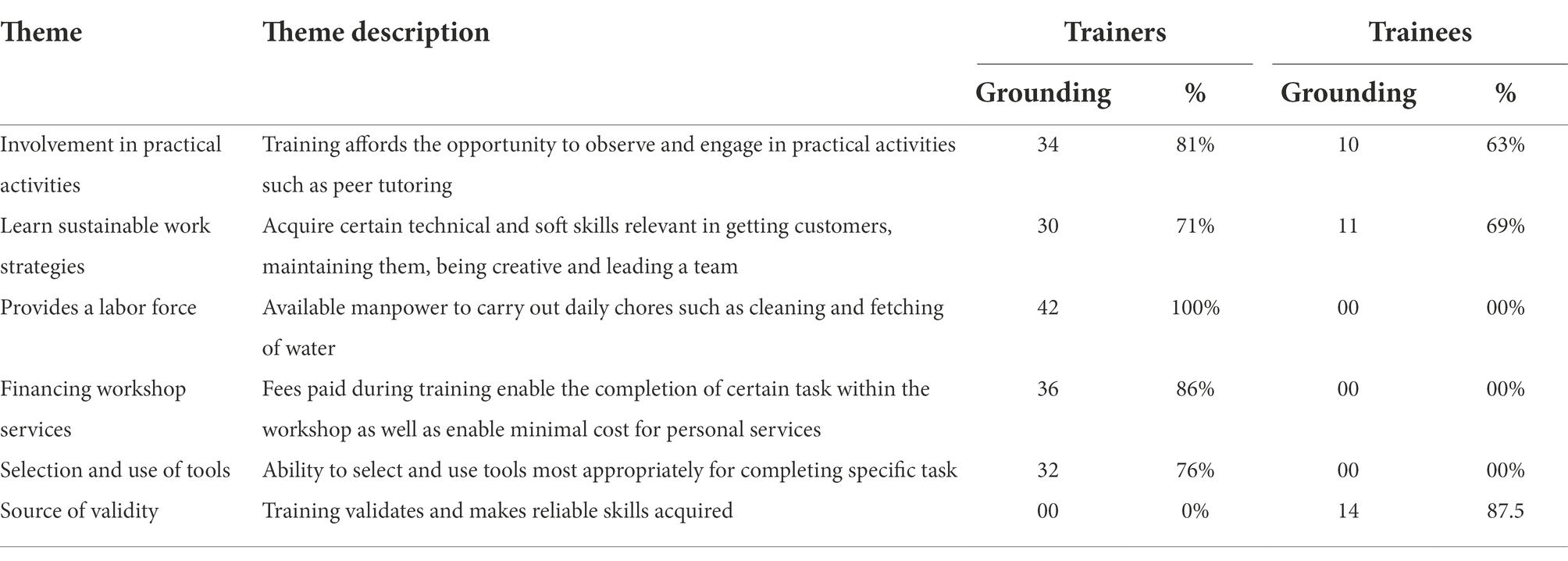

When the strengths of informal training were considered, it was realized that both groups of participants (trainers and trainees) viewed the strengths of the informal training process more in terms of the benefits accrued to the trainees. However, more benefits were perceived by the trainers than the trainees, as seen in Table 2.

The strengths of informal training in ensuring a sustainable livelihood of unemployed youths were captured in six key ways (see themes in Table 2). The perceptions of trainers and trainees on this vary as some of the strengths they shared were similar and others different as presented below beginning with the similar views:

Involvement in practical activities

Both trainers and trainees were of the view that training affords the opportunity to observe and engage in practical activities. Specifically, most of the trainers perceive the training process as one where every trainee is involved daily in all practical activities within the workshop. Trainees are given the opportunity to observe and practice in the workshop while continuing practice at home in the form of assignments, as noted by one of the trainers:

In the course of training, everyone is exposed to all the types of work done in my workshop.

Trainees’ views were consistent with the views of their trainers as they equally perceived their training grounds as a fertile place to practice and also receive support from their peers. To them, this was valuable as it enabled them to complete their assignments and correct their mistakes even before showing the final product to the trainer, as expressed by one of the trainees:

When we have to take measurements, we take each other’s measurements and we can take turns to do that and keep practicing. More experienced apprentices also teach us some of the things that they have already learnt.

Basic requirements of tailoring include measuring, cutting, paddling even before the sewing proper; and every trainee earns the opportunity to get involved in these activities. However, trainers also acknowledged that the level of involvement was based on the trainees’ experience usually measured either by the number of years spent in training or the ability to perform certain assigned task more efficiently as expressed by one of the trainers:

Though everyone is exposed, I also take into account that some are stronger and better at particular things by virtue of their length of training or their ability to learn fast while the weaker ones watch and then later get exposed to performing the task. Mostly, those who are weaker are either new in the workshop or not fast to acquire these skills. You know everyone is not the same.

Here, the trainer noted that involvement was in consideration of one’s level of exposure and their ability to grasp certain skills and perform certain task. Older trainees had the advantage to tutor the newer trainees.

Learn sustainable work strategies

Both trainers and trainees acknowledged that the training process afforded the acquisition of technical and soft skills relevant in getting and maintaining customers, being creative and leading a team. Specifically, trainers viewed their ability to expose trainees to varied work strategies as a strength of their training process. According to trainers, these were worthwhile activities that every tailor must grasp to eventually run and manage a tailoring business. To express this, one of the trainers noted:

Trainees have to be polite and respectful to all clients and I teach them this by example, for instance, when a customer comes into the shop, I say you are welcome, please have a seat. Having a good relationship with the customers will ensure that they trust our work and come back again and again.

According to this trainer, being polite and welcoming was a key strategy in maintaining customers and these strategies were vital for trainees to grasp. Other trainers noted that their strategy was to keep doing quality work so that they can get customers and maintain them. However, trainers also indicated some leadership strategies as one of the strategies that they pass on during training as noted:

My next in command is usually the person who has stayed longer, for now it is […] and as next in command, […] directs the others and distribute task. Sometimes even before I get here […] is expected to put things in order, at least they get to know how to manage things when they open their own shops.

Most trainers see their trainees as prospective trainers so they envisage that these leadership strategies are necessary for the trainees (prospective trainers) to observe and practice.

On the other hand, trainees agreed with trainers that they develop certain skills and attitudes that are essential in sustaining work as a tailor. Specifically, trainees emphasized on technical skills such as paddling, cutting, sewing and designing as well as interpersonal skills such as respecting and valuing customers. One of the trainees noted:

For the first two weeks, we are taught cutting and measurement and then move to paddling. We also go home and continue to practice so in less that no time, we are able to master the skills without any guidance. For the business to have a good reputation, we are also taught to be kind and patient with customers because some are very complicated.

Provides a labor force

One of the strongest themes that emerged as a strength in the training process was the perception of trainees as a source of gaining manpower to offset daily task such as cleaning and fetching of water. Only trainers identified this as a strength as they viewed trainees as a labor force, assisting in daily chores as well as other production activities that facilitate the completion of task and increase production speed. This view can be captured in the expression of the following trainer:

First thing in the morning is cleaning the environment because they cannot sew dresses in a dirty environment and because we all need to drink water in the course of the day, they must make sure that there is drinking water. After this, they must ensure that they participate in sewing at least one dress a day to finish customers’ demands.

Similarly, most trainers do not usually employ workers rather trainees serve as temporal workers during their period of training as noted by the following trainer:

Most workshops do not have permanent workers, well for me, I do not because there are always apprentices and during their training, they get involved in all the task to complete the demands we have.

Trainees therefore serve as a labor force necessary for the smooth operations of the workshops. Only trainers earmarked this as a strength perhaps because they benefit from the work force trainees provide. On the other hand, trainees as apprentices only perceive their input and support as a participatory and engaging process that enables them gain the necessary skills.

Financing workshop services

Trainers also strongly perceived informal training as a source of acquiring necessary finances and as a means of reducing cost for personal benefits. Trainers held that trainees pay a minimal training fee monthly or annually and this fee was relevant in helping them to carry out certain activities considered optimal for the functioning of the workshop as noted:

All apprentices here pay a fee when they come to request for training, they can pay monthly or yearly and this money is used to host a welcome party for them and also to buy some of the materials in the workshop that they will be using. However, when they are coming, they must also bring some basic materials (translated from pidgin English).

According to this trainer, some of the training fee is used for a welcoming party of the trainee. Basically, trainers described this as an event that was aimed at providing a sense of belonging to the new entrant of the workshop and this was relevant for the trainee to feel a sense of acceptance from other trainees and the trainer. In addition to this, some of the money was noted to have been used to purchase practice materials that can be used by the trainees.

Trainers also noted that as an internal policy, one of the benefits of being a trainee is the right to make one’s dress at a very minimal cost. Trainees can use the machines and other tools; however, they need to buy their own materials and cater for any cost outside the workshop as noted by one of the trainers:

Apprentices can sew their own dresses if there is no work to do in the shop but they will buy their materials and if for something like zig zag that we do not have the machine, then they can do it in another shop and pay for it.

Only trainers expressed financing work services as a strength and this is probably because they are the ones who receive, make decisions and manage the fees at will. The trainees equally benefit from the fees they pay as they share in the welcome party and use work tools purchased with some of the funds. The trainees however never highlighted this as a strength because they are not directly involved in managing the money that comes in as fees.

Selection and use of tools

Trainers only, also mentioned the acquisition of skills in selecting and using tools as a strength in the apprenticeship training that can enhance the development sustainable livelihood in trainees. Several tools are used in a tailoring workshop and selecting which one is most appropriate in completing a task is very important. Trainers viewed the process of searching for and identifying appropriate tools as a way to expose trainees to where they can purchase quality tools through errands as well as how to use these tools as they practice daily, as expressed in this quote:

As I send my apprentices on errands to different shops, they get to know the shops that we can trust and get good materials.

The trainers’ goal is to transfer the required knowledge and skills to the apprentices so they see engaging the trainees in errands to sort and identify appropriate tools as a positive strategy that empowers the trainee’s tendency toward apt tool selection. The trainees on the other hand perhaps did not figure this out as a strength because they tend to overlook the value of some task they are assigned to. Trainees are hardly given orientation on how relevant assignments and activities they engage in are toward meeting training goals thereby minimizing the worth.

Source of validity of acquired skills

Trainees strongly perceived training as what validates and makes reliable skills acquired. Most trainees look forward to their graduation, for most, undergoing the training until the time of graduation validates your skills as a new entrepreneur in the market. It serves as a source of acknowledging that your skills are valid and reliable even before proving them to clients as expressed by one of the trainees:

When people know your trainer, they become confident in you or at least if they know that you had training, that’s why you will always see certificates and pictures in most shops.

Only trainees saw training as a source of validating their acquired skills. This is because their main goal is probably to officially complete training and someday open their own workshop. This may differ from that of the trainers who already has the validity and focused on handing down skills. The strengths that emerged from the trainers were thus tilted more toward the training process and strategies involved while trainees emphasized the end product.

Weaknesses of informal training and sustainable livelihoods of unemployed youths

Regardless of the strengths of informal training, trainers and trainees also expressed weaknesses in the process. An analysis of the weaknesses of informal training indicated that trainers viewed this in light of the challenges that they face in the training process as well as in the management of their workshops while trainees focused on the challenges that they faced in relating with their trainers as presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Analysis of the weaknesses in informal training and sustainable livelihood of unemployed youths.

These weaknesses were captured in four key ways (see themes on Table 3). The only weakness that emerged from both the trainers and the trainees was financial constraints as presented below.

Financial constraints

When trainers indicated finances as a weakness, they viewed it in two ways; firstly, that trainees unable to pay their training fees inhibit the consistency of their training; and secondly, that financial constraints make it difficult for them to afford specialized machines. In consideration of trainees paying their training fees consistently, one of the trainers indicated:

Many of these my apprentices here go and come back. Some cannot pay the fee monthly so they go and stay home and come back only when they have the money. For instance, I had one here, she came here two years ago, this month she will pay and next month, she cannot…well her father is struggling so until now, she does not even know cutting and paddling well.

Consequently, many trainees who cannot afford the training fee will stop working for a period of time and continue again when they can afford it, so some spend several years at the same learning stage. On the other hand, though trainees acknowledged that paying their training fee was challenging, they expressed that it was more of a constraint because the trainers were not patient or understanding of their situation, as noted:

Some madams too do not understand the times and they will not allow us come to work if you have not completed the fee. So, some months I go first and work in a bar so I can raise the money for the training, that’s why I am still here until now.

Interestingly, this trainee expects the trainer to understand the financial difficulties that trainees encounter. The trainee also highlights other activities like selling in a bar (drinking parlor) that she needs to carry out to ensure that they can continue their training.

Inadequate finances also made it difficult for some trainers to afford some specialized machines and trainees may have to go to other workshops to get the task done as expressed by one of the trainers:

More specialized activities like zig zagging, trainees will have to go to another workshop to do it, this is because those with the machine in Buea are few and the machines are expensive.

Apart from financial constraints, only trainers perceived low entry qualification of trainees, trainees’ unwillingness and unreadiness to learn as a weakness in the training as examined below respectively:

Low entry qualification

Trainers overwhelmingly agreed that many of the youths who seek their training services have not had any form of formal education or have lower levels of education. The educational levels of these youths make it difficult for them to grasp certain skills, thus delaying their training period, as noted by this trainer:

I have been doing this for about 10 years and overtime, I have realized that those who are further advanced educationally, like formal education and sitting in the classroom, those ones learn faster than people with limited education. Like I trained a university graduate and she finished in no time.

According to this trainer’s experience, trainees who have some level of formal education complete their training in a shorter time compared to those without or with lesser levels of education. Formal education is therefore a key way of sustaining the livelihoods of youths involved in informal training. As a norm, most of the children and youths who engage in informal training are those who do not do well in formal training centers or, in most cases, are perceived as those without the potential to perform well, so training becomes the solution to getting them employed. However, tailoring requires mathematical and organizational skills, which might become complex and difficult for someone who has not been exposed to some type of formal education, as expressed in the following quote:

You cannot measure without knowing numbers and you must write down your measurements neatly but some of my apprentices do not even know how to read or write so they take measurements wrongly.

Perhaps only trainers saw low entry qualification as a weakness because of the difficulty they experience in passing on skills to trainees with no or very little formal education compared to the more literate ones. Although peer tutoring takes place among trainees, the trainer is the one directly involved and the vision bearer of the training goal so what obstructs skills acquisition becomes more worrisome to the trainer.

Unwillingness and unreadiness to learn

Most trainers indicated that some of their greatest challenges are working with trainees who are not ready or willing to learn. This weakness results in trainees spending more than the required number of years in training. In other cases, trainees’ unwillingness to learn results in high levels of absenteeism, which delays the production speed of clothes as work is always programmed beforehand, taking into consideration the manpower. Specifically, to express the negative effects of absenteeism and laziness, one of the trainers noted:

When trainees behave poorly, it’s really bad, for instance, I have already programmed work for tomorrow so when they do not come or are lazy, the work cannot become completed and you know that we give clients deadlines beforehand. Some come late because they are either nannies or doing some other activity at home like child care.

While this trainer acknowledges that trainees’ absenteeism resulted in undue delays, he also alluded to the fact that trainees are juggling several activities at a time and are unable to give maximum time to their training. Apart from this, some trainees do not have a passion for or interest in tailoring. In most cases, it is the parents or guardians—people the apprentices live with and work for—who decide that the trainees learn tailoring without considering their interest. As a result, some trainees are not motivated, which limits their tendency to fully engage and commit to work tasks.

Delay of program

Interestingly, while most trainers alluded to a delay in the training process as a result of trainees’ inability to pay tuition fees, absenteeism, and unseriousness, trainees also indicated that trainers intentionally delayed their training period. According to trainees, they had to spend more time learning the skills and strategies involved because some of the trainers did not show them all that it takes. In other scenarios, some trainees indicated that they had to move to more than one shop to gain the required skills. While trainers viewed this as the challenge of not having specialized machines, trainees felt it was an intentional act to delay their training and extort more money through training fees, as noted by this trainee:

It’s only after like six months that madam will teach you to sew a trouser, for instance. Sometimes, when we are on errands, that’s when she will do some technical work. After sometime with her, I left to another workshop to learn designing because she never showed us.

Though not expressed by trainers in their interviews, some trainers may feel threatened about exposing all their techniques to trainees in order to avoid competition. Also, trainers in need of the services or assistance of trainees who have mastered the required skills for meeting client demands might be hesitant to let them go so as to keep benefiting from their free services. Another plausible reason for trainers to keep trainees longer is to ensure that the trainees master the necessary skills in order to build a legacy and receive positive feedback on the trainees’ work. Trainers’ expertise is reflected in the work of their apprentices, so if a trainee does not perform well after completion, the trainer receives negative feedback that consequently retards the business. If otherwise, the trainer gets good feedback and more opportunities. Trainers will thus do their best to maintain standards and will keep trainees for an extended period of time to ensure skill mastery. Trainees’ eagerness to complete the course limits their tendency to reason in line with trainers on this. Contrarily, trainees see every delay as a calculated exploitative attempt by the trainer.

Opportunities of informal training and sustainable livelihoods of unemployed youths

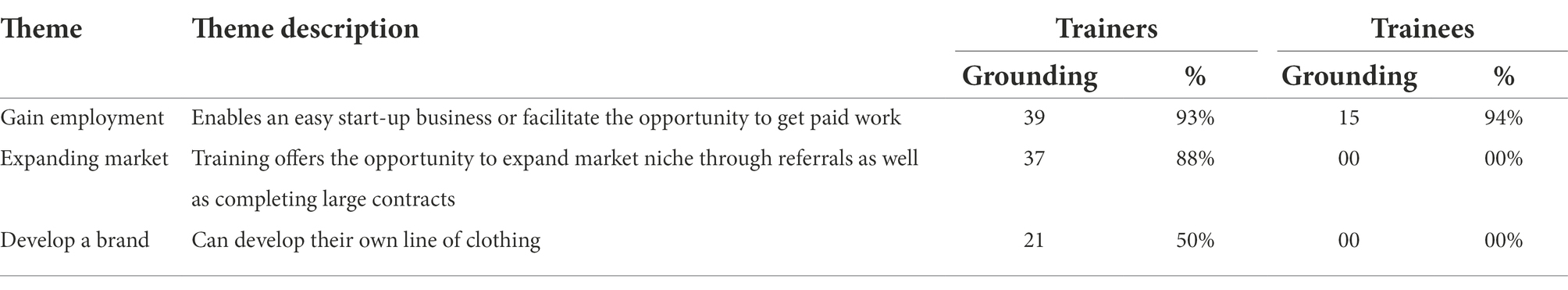

Regardless of the weaknesses, trainers and trainees also indicated several opportunities of informal training and its role in sustaining the livelihoods of unemployed youths. Themes emanating from an analysis of these responses are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Perceived opportunities of informal training and sustainable livelihoods of unemployed youths.

The opportunities were captured in three themes (see themes on Table 4). The only theme that emerged as an opportunity for both the trainers and the trainees was that informal training serves as a source of gainful employment as examined below:

Gain employment

Both trainers and trainees agreed that gaining some type of employment was an obvious benefit of informal training. Specifically, trainers viewed this opportunity in two ways: either the trainees become shop owners and self-employed, or they become employed by other tailors after the completion of their training. Specifically focusing on trainees becoming prospective shop owners, one of the trainers indicated:

After completion, these apprentices are expected to go and open their own shops and will also become trainers.

Becoming a shop owner was a redundant view expressed in the analysis of trainees’ interviews, as most trainees envisaged one thing after graduation, and that is owning their own workshops. Unlike trainers, no trainee envisaged being employed by other tailors, as expressed by this quote:

After this, I will find my own place and open my own shop. It’s not good to patch with other tailors, it’s better to have your own shop and start small.

This trainee totally discourages the idea of working with another tailor; rather, one should have their own little shop as long as one has ownership. This was the only opportunity earmarked by trainees. Trainees’ perception of training appears limited to just having their own shops at the end with very little or no awareness of other opportunities such as market expansion and gaining contracts, which are highlighted by the trainers. This indicates that trainers seem to focus more on skill acquisition and fail to introduce trainees to some business opportunities available in the trade that can motivate them and enhance achievement.

Expanding market

Trainers indicated that through the quality of their work, whether in the production of clothes or the training of youths, they can expand their market. Similarly, this can also afford them the opportunity to provide more training services to youths. To express this, one of the trainers indicated:

I do not go to the radio to advertise my business; the quality of my work advertises itself and opens me to more clients and apprentices. There are some workshops that even one apprentice will not even go there and it’s difficult to manage this business without apprentices or customers.

Some of the trainers also indicated that they see opportunities to expand their businesses through large contracts as noted:

With a tailoring workshop, one has the opportunity to gain large contracts, for example, a school might want like 200 uniforms and then give us a contract. Also, during mountain race or labour day, we make a lot of money.

According to this trainer, special occasions offer them an opportunity to earn huge contracts and make a lot of sales. However, trainees did not indicate an expansion of the market as an opportunity that they envisaged.

Develop a brand

Trainers also envisaged that if trainees can become creative, innovative and think broadly, then they can do better and develop their own brands which is one of the highest states of attainment for tailors. One of the trainers noted the following:

I always encourage my trainees to be smart, there are a lot of opportunities with tailoring, but one needs to think broadly. One of the booming areas now is developing your own brand and you cannot become comfortable having just one machine or attending to one customer a day.

Threats to informal training and sustainable livelihoods of unemployed youths

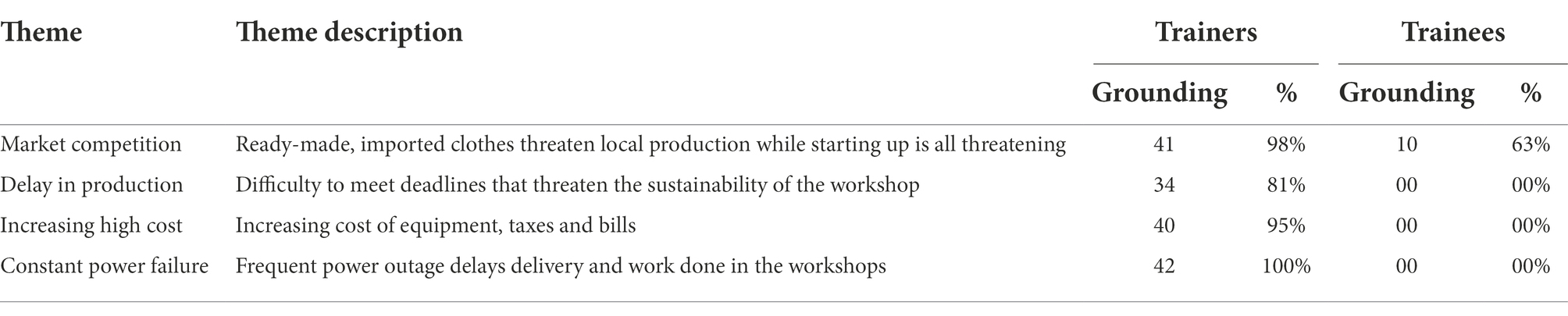

When the threats to the training process were considered, it was realized that trainees perceived only a single threat in view of being a prospective shop owner. However, these threats were captured by four themes as presented in Table 5.

The threats that emerge from the findings were captured in four themes (see themes on Table 5). The main threat that emerged from both the trainers and the trainees’ views was market competition. This was the only threat highlighted by trainees as presented below:

Market competition

While both trainers and trainees saw market competition as a threat, trainers viewed this more in terms of the presence of available cheap ready-made and imported dresses as a threat to the functioning of the local workshops as noted in the following quote:

Competition from ready-made dresses and imported dresses is acute, due to failure to deliver on time, some clients mostly consider readymade dresses over tailored dresses.

While trainers’ expressed distress about competing with ready-made and imported clothes, they also acknowledged that they do not meet deadlines, which is a possible motivation for some customers to prefer ready-made dresses. On the other hand, trainees perceived market competition as a possible threat that might emerge when they start their own businesses and need to compete with established workshops, as noted in the following quote:

There are already established workshops so it can be challenging to open and succeed as a beginner.

Trainees’ perception of the presence of other established workshops as a threat shows their lack of enthusiasm and motivation to innovate and improve on their skills so as to thrive in the competitive situation. Most trainees are satisfied with what they learned during the training. The curiosity to learn more strategies, designs and tendency to innovate is lacking. Most trainees; do not have a good vision with regards to their growth and business expansion, do not set realistic goals and do not have the confidence in their ability to excel in the trade. Trainees have a mediocre mind set limited to opening a workshop and performing the rudimentary tasks. For youth in informal training to develop effective sustainable livelihoods, training needs to go beyond basic skills acquisition to nurturing a sense of curiosity, creativity and an entrepreneurial mind set in trainees.

Delay in production

Many trainers felt threatened about being approached by many trainees who could eventually turn out to be unserious. According to trainers, unserious trainees can delay production, making it difficult for them to meet deadlines, with dire consequences for retaining customers. However, they have no tool for measuring who will be a serious trainee or not, till after some time. In practice, new trainees can be found almost every week in the workshop as they come and go. This was captured in a trainer’s expression:

When you have a workshop that you cannot rely on your apprentices, it’s very worrying because you cannot even take large orders as you may not meet up with the customers time which makes them angry.

Increasing high cost

The cost of equipment and paying taxes and bills threatens these training centers, as trainers indicated that they have to pay very high electricity bills in order to use all their machines and equipment, as noted:

Electricity bills keep increasing and we cannot afford them as we need to use machines. This high cost adds to the cost of production and equally reduce the profit that one makes.

Other trainers focused on the high taxes and indicated that tax rates keep increasing making it difficult for them to keep working as expressed by one of the trainers:

The tax office inflates the amount to be paid for taxes and failure to pay can result in the sealing of one’s shop preventing work for days.

According to this trainer, they are forced to pay high taxes if they must keep their workshops open and continue production.

Constant power failure

Trainers also indicated that frequent power failures limited training time and delayed delivery. For instance, one of the trainers indicated that frequent power cuts equally made it very difficult to complete large orders that are central to the success of every workshop, as expressed in this quote:

Frequent power cuts make it difficult to deliver on time especially when we have to sew for social groups or uniforms for colleges. Such contracts are what survives our business.

In summary, while the SWOT analysis revealed only slight variations when the views of trainers and trainees are considered, there is a considerable interrelationship between the perceived strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats of the informal training process seen in Figure 1.

Discussion

Informal training of unemployed youth helps them develop suitable work strategies and attitudes. Additionally, they develop technical skills through work practice, participatory observation, and peer tutoring. However, low entry qualifications of trainees, unwillingness to learn and financial constraints inhibit training, thus reducing the likelihood of youth attaining sustainable livelihoods. It can be attested from the strengths that informal apprenticeships are essential in developing the skills and attitudes needed for youths to start up their own enterprise. This can, however, be effectively attained if trainees recruited have acquired basic literacy skills and are motivated and supported to engage in the trade.

Concerning the external factors, expanding the market through referrals based on the quality of work done, gaining large contracts, developing new brands, employment, and the possibility for trainees to open their own workshops are opportunities for tailors in informal apprenticeship to thrive. Notwithstanding, constant power failure, increasing high-cost taxes, bills, equipment, and market competition threaten the survival of informal apprenticeship training. The opportunities for growth in this enterprise are compelling, but the need to improve the situation of power supply and to implement considerable taxes is vital in helping tailors grasp the opportunities.

The shortcomings of informal apprenticeship training presented in the findings are not unique to Cameroon, as they are consistent with the view of Andreoni (2018); Leyaro and Joseph (2019); and Sorensen et al. (2017) that TVET systems in Africa are hampered by poor quality training facilities, trainers, equipment, and curricula. Financial constraints are a common challenge in most LMICs. The unavailability of resources such as specialized machines, power supply and funds to pay for training makes it inconsistent and retards mastery of relevant skills needed for a sustainable livelihood. Also, the issue of absenteeism and unseriousness of trainees that emerged as a weakness in the system is consistent with the high dropout rate among apprentices in several other countries (Hoffman and Okolo, 2013). Some advantages of tailoring apprenticeships in the findings, such as engaging trainees in practical activities that foster skill development and employability, are in line with Palmer’s, (2017 p. 12) proposition that informal apprenticeships are the primary source of technical and vocational skills development in Sub-Saharan Africa and are responsible for 80% of employment in much of the area (International Labour Organisation, 2012). The practical nature of informal apprenticeship training and its tendency to employ most youth is thus established. Improving the quality of training in this domain is therefore vital to foster access to decent employment opportunities and sustainable livelihoods among the youth. Based on this, it can be demonstrated that informal apprenticeship can be effective in addressing high levels of youth unemployment in low- and middle-income countries, provided that the strengths and opportunities are maximized while the weaknesses and threats are minimized.

The constant demand for uniforms and other clothing in Cameroon precipitates the constant need for tailoring services. Organizing efficient tailoring apprenticeships is vital for developing the right attitude and skills needed for emerging tailors to thrive in the trade and meet customers’ demands. Tailoring workshops need to be equipped with all the necessary machines (sewing, zigzag, marking, pressing buttons) to enable trainees to access and master how to use them. Basic literacy skills are necessary and essential in facilitating skill mastery in tailoring. Just as a trainer mentioned, “more educated trainees easily master tailoring in no time, “and educated trainees perform better than illiterate ones. Trainers must include some training on basic literacy skills for trainees in need or set a criterion for recruiting trainees that limits the intake of non-literate youth. Alternative sources of power supply such as generators and solar energy panels are needed in case of power failure in substitution of ENEO, the lone electricity supply agency in Cameroon. The practical and interactive nature of informal training for tailors is valuable in enhancing skill mastery, but unfortunately, this is not what is obtained in the formal system. Apprenticeships in tailoring are a pathway to a sustainable livelihood for unemployed Cameroonian youth as it is a good opportunity for them to gain the necessary skills to start up their own workshops.

Limitations

The participatory SWOT analysis was limited to the experiences of trainers and trainees practically involved in the training. The voices of some stakeholders, such as clients, apprentices who have dropped out, and those who have successfully completed the training, were not captured. Perhaps some more valuable insights could have been obtained from their responses. For example, clients’ expectations of tailors and the extent to which such expectations are met. The sample size (42 trainers and 16 trainees) was immense given the qualitative interview nature of the study. Although the large size stemmed from the decision to get data saturation for the categories (male and female trainers and trainees), it led to huge data sets that complicated the analysis. The use of focus groups for the different categories would have reduced the sample size and led to a more organized data set.

Conclusion

Small businesses and micro-enterprises constitute one of the largest sectors of the economy in many low- and middle-income countries. Informal training through apprenticeships is anchored in this sector and plays a significant role in providing particular employment opportunities to many youths in these countries. Unfortunately, informal training in Africa has been underfunded, not prioritized by African governments, and lacks quality training facilities and trainers. Given the potential of the informal sector to nurture and develop skills in African youth, some attention is needed to improve the quality of training to expose many more youth to decent employment opportunities and sustainable livelihoods. Insights from empirical data from tailors and their apprentices in Cameroon indicate the potential this sector has to expand the market of the country’s clothing industry and provide an avenue for youth employment, an overarching need in the country. This sector thus deserves attention. The need to provide and improve on the resources and quality of training is vital to making the most of tailoring apprenticeship. There is also need to orient trainers in the informal sector to emphasize the business part of the tailoring trade to apprentices in the course of the training so as to keep them curious and motivated.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

IN-E: the lead author conceived, outlined the various phases of the study, reported on; TVET, apprenticeship training in Africa and the SWOT analysis. She collated the introductory literature, defined the methodology, collected data from 11 trainers and four trainees and participated in data analysis. She also discussed the findings and concluded the paper. EA: reviewed literature on informal training and youth unemployment in low- and middle-income countries, collected data from 10 trainers and four trainees and participated in the analysis. She summarized the complete data sets, presented the results and structured the final work. SM: collected material on the strengths of informal training and apprenticeships in Low- and Middle-Income Countries and data from 11 trainers and four trainees. She also assembled and prepared references for the sources that informed the study. NF: reviewed literature on weaknesses of informal training in low- and middle-income countries, collected data from 10 trainers and four trainees and participated in the analysis. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adams, A., Johansson de Silva, S., and Razmara, S. (2013). Improving Skills Development in the Informal Sector. Strategies for Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Aggarwal, A. (2013). “Lessons from informal apprenticeship initiatives in eastern and southern Africa,” in Apprenticeship in a Globalised World: Premises, Promises and Pitfalls, Vol. 27. eds. S. Akoojee, P. Gonon, H. Ursel, and C. Hofmann (Geneva: International Labour Organization).

Akoojee, S. (2016). Private TVET in Africa: understanding the context and managing alternative forms creatively! J. Tech. Educ. Training 8, 38–51. Available at: https://publisher.uthm.edu.my/ojs/index.php/JTET/article/view/1269

Ambardekar, A. P., Eriksen, W., Ferschl, M. B., McNaull, P. P., Cohen, I. T., Greeley, W. J., et al. (2022). A consensus-driven approach to redesigning graduate medical education: the pediatric anesthesiology Delphi study. Anaes. Anal., 10-1213. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000006128

Andreoni, A. (2018). Skilling Tanzania: Improving Financing, Governance and Outputs of the Skills Development Sector. London: ACE SOAS Consortium. Available at: https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/30117/1/Andreoni%20Skilling-Tanzania-ACE-Working-Paper-6.pdf

Ayele, S., Oosterom, M., and Glover, D. (2018). ‘Youth Employment and the Private sector in Africa.’ Institute of Development Studies. IDS Bulletin 49. Available at: https://bulletin.ids.ac.uk/index.php/idsbo/article/view/3005/Online%20article

Axmann, M., and Hoffman, C. (2013). “Overcoming the working experience through quality apprenticeships – the ILO contribution,” in Apprenticeship in a Globalised World: Premises, Promises and Pitfalls, Vol. 27. eds. S. Akoojee, P. Gonon, H. Ursel, and C. Hofmann (Geneva: International Labour Organization), 37.

Britto, P. R., Oketch, M., and Weisner, T. (2014). “Nonformal education and learning,” in Learning and Education in Developing Countries: Research and Policy for the Post-2015 UN Development Goals. ed. D. A. Wagner (New York: Palgrave Pivot)

Datta, N., Assey, A. E., Buba, J., and Watson, S. (2018). Integrated Youth Employment Programs: a Stocktake of Evidence on What Works in Youth Employment Programs. Jobs Working Paper, 24.

Delmar, F., and Shane, S. (2004). Legitimating first: organizing activities and the survival of new ventures. J. Bus. Ventur. 19, 385–410. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00037-5

During, P., Holmberg, H. C., and Sperlich, B. (2018). The potential usefulness of virtual reality systems for athletes: a short SWOT analysis. Front. Physiol. 9:128. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00128

Engelbrecht, H., Lindeman, R. W., and Hoermann, S. (2019). A SWOT analysis of the field of virtual reality for firefighter training. Front. Rob. AI 6:101. doi: 10.3389/frobt.2019.00101

Fox, L., and Kaul, U. (2017). The Evidence is in: How Should Youth Employment Programs in Low Income Countries be Designed USAID Available at: https://static.globalinnovationexchange.org/s3fs-public/asset/document/YE_Final-USAID.pdf.

Glick, P., Huang, C., and Mejia, N. (2015). The Private Sector and Youth Skills and Employment Programs in Low- and Middle-Income Countries RAND Corporation, USA and Solutions for Youth Employment (S4YE) Available at: https://www.s4ye.org/sites/default/files/S4YE_Report_1603414_Web.pdf.

Gomis, R., Kapsos, S., and Kuhn, S. (2020). World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2020. Geneva: International Labour Office.

Hardy, M. L., Mbiti, I. M., Mccasland, J. L., and Salcher, I. (2019). The Apprenticeship-to-Work Transition: Experimental Evidence from Ghana. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Hoffman, C., and Okolo, W. (2013). “Transitions and informal apprenticeship: results from the ILO research in several African countries,” in Apprenticeship in a Globalised World: Premises, Promises and Pitfalls, Vol. 27. eds. S. Akoojee, P. Gonon, H. Ursel, and C. Hofmann (ILO, Berlin: ILO), 37.

Ichikowitz Family Foundation (2022). African Youth Survey 2022. Available at: https://ichikowitzfoundation.com/wpcontent/uploads/2022/06/AfricanYS_21_H_TXT_001g1.pdf

International Development Research Centre (IDRC)Dutch Knowledge Platform on Inclusive Development Policies (INCLUDE)The International Labour Organization (2016). Gathering evidence: How can soft skills development and work-based learning improve job Opportunities for young people? Boosting decent employment for Africa’s youth. Available at: https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/bitstream/handle/10625/57588/IDL57588.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

International Labour Organisation (2012). Upgrading Informal Apprenticeship: a Resource Guide for Africa. Skills and Employability Department. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---Africa/---roabidjan/documents/publication/wcms_171393.pdf

International Labour Organization (ILO) (2018). State of skills in Cameroon. Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Geneva. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---ifp_skills/documents/genericdocument/wcms_743140.pdf

Ismail, Z., and Mujuru, S. (2020). Workplace based learning and youth employment in Africa. Boosting decent employment for African youth: Evidence synthesis paper series 3/2020. Include and ILO. Available at: https://includeplatform.net/publications/evidence-synthesis-wbl-and-youth-employment-in-africa

Leyaro, V., and Joseph, C. (2019). Employment mobility and returns to technical and vocational training: Empirical evidence for Tanzania. CREDIT Research Paper, No. 19/03. Nottingham, UK: The University of Nottingham, Centre for Research in Economic Development and International Trade (CREDIT). Available at: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/210854/1/1067854185.pdf

Manzini, F., Diehl, E. E., Farias, M. R., Dos Santos, R. I., Soares, L., Rech, N., et al. (2020). Analysis of a blended, in-service, continuing education course in a public health system: lessons for education providers and healthcare managers. Front. Public Health 8:561238. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.561238

Marx, V., and More, K. R. (2022). Developing Scotland’s first green health prescription pathway: a one-stop shop for nature-based intervention referrals. Front. Psychol. 13, 1–14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.817803

McKenzie, D. (2017). How effective are active labour market policies in developing countries? A critical review of recent evidence. World Bank Res. Obs. 32, 127–154. doi: 10.1093/wbro/lkx0001

Ngathe, K. P., (2015). Encouraging countries to invest in the skills development of trainers and entrepreneurs: Cameroon’s report.

Nowreen, S., Chowdhury, M. A., Tarin, N. J., Hasan, M. R., and Zzaman, R. U. (2022). A participatory SWOT analysis on water, sanitation, and hygiene management of disabled females in Dhaka slums of Bangladesh. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 12, 542–554. doi: 10.2166/washdev.2022.061

Oketch, M. O. (2018). “Learning at the bottom of the pyramid in youth and adulthood: a focus on sub-Saharan Africa,” in Learning at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Science, Measurement, and Policy in Low-Income Countries. eds. D. A. Wagner, S. Wolf, and R. F. Boruch (Paris, France: UNESCO/IIEP), 197–209.

Oosterom, M. A. (2018). Youth Employment & Citizenship: Problematising Theories of Change. K4D Emerging Issues Report. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies.

Palmer, R. (2017). Jobs and Skills Mismatch in the Informal Economy. Geneva: ILO. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---ifp_skills/documents/publication/wcms_629018.Pdf

Republic of Cameroon (2009). Growth and Employment Strategy Paper. Available at: https://www.cameroonembassyusa.org/images/documents_folder/quick_links/Cameroon_DSCE_English_Version_Growth_and_Employment_Strategy_Paper_MONITORING.pdf

Robert, P. H., König, A., Amieva, H., Andrieu, S., Bremond, F., Bullock, R., et al. (2014). Recommendations for the use of serious games in people with Alzheimer's disease, related disorders and frailty. Front. Aging Neurosci. 6:54. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00054

Schraven, B. (2013). “Youth between urbanisation and poverty: livelihood opportunities and challenges in informal apprenticeships in Ghana,” in Apprenticeship in a Globalised World: Premises, Promises and Pitfalls, Vol. 27. eds. S. Akoojee, P. Gonon, H. Ursel, and C. Hofmann (Berlin: ILO), 37.

Sharma, P., and Pardeshi, G. (2021). Rollout of COVID-19 vaccination in India: a SWOT analysis. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 6, 1–4. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2021.111

Sorensen, A., Aring, M., and Hansen, A. (2017). Reforming Technical and Vocational Education and Training in Tunisia: Strategic Assessment USAID Available at: https://simtunisie.weebly.com/uploads/1/8/1/2/18128835/aup_tunisia_tvet_assessment_final.pdf.

Tinga, A. M., De Back, T. T., and Louwerse, M. M. (2020). Non-invasive neurophysiology in learning and training: mechanisms and a SWOT analysis. Front. Neurosci. 14:589. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00589

Topuz, S., Sezer, N. Y., Aker, M. N., Gonenc, I. M., Cengiz, H. O., and Korucu, A. (2021). A SWOT analysis of the opinions of midwifery students about distance education during the Covid-19 pandemic a qualitative study. Midwifery 103:103161. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2021.10316

Tripney, J. S., and Hombrados, J. G. (2013). Technical and vocational education and training (TVET) for young people in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Empirical Res. Vocational Educ. Training 5, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/1877-6345-5-3

United Nations (2015). General Assembly Resolution a/RES/70/1. Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. (New York: Author). Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf

Wait, M., and Govender, C. (2019). SWOT criteria for the strategic evaluation of work integrated learning projects. Africa Educ. Rev. 16, 142–159. doi: 10.1080/18146627.2018.1457965

World Bank (2017). World Development Report 2018: Learning to Realize Education’s Promise. Washington, DC: World Bank.