- Department of Curriculum and Instruction, College of Education, King Faisal University, Al-Hofuf, Saudi Arabia

This study investigates the perceptions of 149 English language students about online language learning at a state university in Saudi Arabia and how this experience has prepared them to continue online learning in post-pandemic times. It also investigates any differences in students’ attainment of the four language skills of reading, listening, writing, and speaking with respect to the online learning experience. Data were collected using a questionnaire with close-ended items with each item having an open-ended query. The findings of the study indicate that, overall, the students had positive attitudes toward learning English online whether during the pandemic or after it is over. However, their views differed regarding the acquisition of the four language skills; learning the receptive skills of reading and listening online was perceived positively, while learning the productive skills of writing and speaking online was perceived negatively as a result of the online learning mode. The study concludes that more advanced technical features are needed to be introduced onto online learning platforms for more effective learning outcomes and that the current platforms at universities fall somewhat short of the English language students’ needs.

Introduction

After the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in late 2019 and its rapid spread in early 2020, many countries worldwide implemented lockdowns in March 2020 (Hodges et al., 2020). Although many people had adapted quickly to the new measures by, for example, working from home, the question of how education could continue in schools and universities remained unclear in the beginning. However, gradually, governments swiftly adopted online education as a preferred mode of education to continue (Hazaea et al., 2021).

In 2021, many countries started to relax their earlier COVID-19 restrictions and allowed for the partial return of university and school students as long as social distancing was maintained (Milne et al., 2020). In Saudi Arabia, in March 2022, the authorities announced that all COVID-19 restrictions were lifted and that life would go back to what it used to be before the pandemic (Thompson, 2022), including the full return of students to schools and universities. However, some universities have since continued to use online learning platforms even after the restrictions were lifted in the country. This step has been welcomed by some university students but disapproved by others. Several previous studies in the Saudi context investigated COVID-19 with respect to various variables (Al-Ahdal and Alqasham, 2020; Alamer, 2020; Almekhlafy, 2020). In addition, Alamer (2020) investigated the use of the Blackboard; Almekhlafy (2020) explored students’ vocabulary learning; Al-Ahdal and Alqasham (2020) studied the competency of Saudi professors in computer skills.

Despite such vast research in the area, a chasm that is still unbridged is the impact of online learning on the acquisition of the four language skills. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the perceptions of English language students in a state university in Saudi Arabia on their language skills acquisition as a factor of online learning. This investigation tries to answer the following questions:

Research questions

This study aimed to investigate the following research questions:

1. How do English language students at a Saudi University perceive the implementation of online language learning in the post–COVID-19 era?

2. Are there any differences in the acquisition across the four language skills (reading, writing, speaking, and listening) that the students reported when they were taught online?

Literature review

Saudi Arabia and online education during the pandemic

When many countries worldwide shifted to online teaching as a response to the spread of coronavirus, Saudi Arabia was exceptionally effective in implementing online teaching in education both at schools and at institutions of higher education. For school education, Saudi Arabia established the Madrasati (Arabic for my school) online platform, which served more than 6,000,000 school students and 500,000 teachers averaging 250,000 online streaming every day (Al-Thumairy, 2020). The Online Learning Consortium (OLC) compared the Madrasati platform with other online teaching platforms from other countries and concluded that the “Saudi platform outperformed its international peers and proved to be one of the best responses taken to address the pandemic challenges, whereas more than 6 million users subscribed to Madrasati with a penetration rate amounting to 98%” (Unified National Platform [UNP], 2021, para. 3).

Despite this achievement, however, few studies have focused on the implementation of language online learning at Saudi universities, in contrast to numerous such studies in other countries (e.g., Bailey and Lee, 2020; Kitishat et al., 2020; Hammond et al., 2021; Hazaea et al., 2021). The reason for the lack of studies on online learning at Saudi universities—unlike Saudi school education—stems from the fact that school education uses a central national platform across the country reinforced by the Ministry of Education. Moreover, each Saudi University is left to implement the online platform, such as Blackboard or Zoom, that best suits their needs without any enforcement from a higher authority. Therefore, it has been more feasible for many studies (e.g., Aldossry, 2021; Alkinani and Alzahrani, 2021; Alubthane, 2021; Shishah, 2021; Alqahtani, 2022) to investigate various research questions related to online learning in Saudi schools compared to Saudi universities.

Nevertheless, some studies have attempted to investigate online learning in Saudi higher education. For example, Al-Ahdal and Alqasham (2020) surveyed a group of professors at the Saudi Electronic University and Qassim University. They discovered that the study subjects had moderate computer competency, which led to a number of challenges such as detecting cheating during online exams as well as their belief that the performance of learners was not as effective. They concluded that more organization is essential when performing online teaching.

Similarly, Alolaywi (2021) investigated the advantages and disadvantages of online learning from the perceptions of 43 English language teachers at Qassim University. The respondents expressed their preference for online teaching because it was an opportunity to improve their technical skills and make the most of the available online tools, such as teaching methods and assessments. Considering the disadvantages, however, the respondents reported that they struggled with the immediate transition to online learning without any former preparation.

Another study on online teaching during the pandemic in Saudi Arabia was conducted by Abduh (2021). She surveyed the perceptions of 26 English language instructors at Najran University toward the online assessment methods they used, the challenges that they faced, and whether there were any differences between perceptions of male and female instructors. The findings revealed that the majority of the research subjects had moderately positive attitudes to online assessment but believed that online teaching itself was challenging. Overall, however, their perceptions of online teaching were positive and there were no clear differences between perceptions of male and female instructors.

However, few studies have focused on the experiences of English language learners at universities in Saudi Arabia. For example, Alamer (2020) explored the perceptions of 34 English language students at a Saudi University toward learning vocabulary online using Blackboard during the pandemic. She concludes that, initially, the learners had negative attitudes toward learning vocabulary online. However, over time, using the Blackboard, despite its limitations, has improved their attitudes, and subsequently, their vocabulary level.

Another study that focused on English language students at Saudi universities and their experiences during the pandemic was carried out by Almekhlafy (2020). He surveyed 228 first and second-year English language students at a Saudi University and found that second-year students had negative perceptions toward using the Blackboard even though they had used it during blended learning alongside attending face-to-face classes before the pandemic. In contrast, first-year students had more positive attitudes toward using the Blackboard as the primary tool for English language learning. The author argues that this happened because the second-year students had been using the Blackboard as a tool of communication between them and their instructors rather than an effective learning tool. Therefore, he calls for further training and technical support for both students and instructors to make the most of the platform. Another significant finding reported by Almekhlafy (2020) was that students in his sample perceived learning listening and reading skills online positively compared to writing and speaking that were perceived negatively. However, he did not provide an explanation for why this was the case.

Therefore, this study built on Alamer’s (2020) and Almekhlafy’s (2020) studies by extending the investigations to include all four language skills and explaining why some skills were perceived to benefit differently than other(s). Furthermore, the current study examined the students’ attitudes toward online English language learning in the post–COVID-19 period as a permeant learning tool rather than a temporary measure designed to deal with the learning issues during the pandemic to be terminated once the pandemic was over.

Methodology

Research design

This study adopted a survey design. It collected data on the perceptions of Saudi undergraduate students on the impact of online learning on their acquisition of the four language skills. The study was conducted at a state university in Saudi Arabia for the academic year (1442–1443) AH.

Participants

In total, 149 male and female students at a Saudi state university participated in this study. They were first-year students studying in the department of English. This was a convenience sample and the university required them to continue attending online classes even after lifting the pandemic restrictions and measures as a part of its plan to make the most of the advantages that online learning provides. The participants were informed of the research aim, assured of data confidentiality, and their consent duly obtained.

Data collection tool

To address the research questions, this study developed a questionnaire consisting of 10 open-ended and close-ended items. The open-ended questions provided the respondents with a set of answers to choose from across three alternatives (agree, disagree, and I do not know/it does not differ from face-to-face learning). Next, each close-ended question was followed by an optional open-ended question that allowed the respondent to explain the reasons for choosing their answer, answering this was optional. In the end, there was another open-ended question that allowed the respondents to freely express any thoughts on the topic not covered in the previous close-ended questions.

Data collection process

After the formulation of the survey questions, validation was sought from three senior professors with at least 2 years of experience in online education. Their suggestions pertained to item reframing were duly enforced. Following this, a link on Google Forms was created. It was then sent to the academic staff at the English department where the respondents are enrolled. They shared the link with their students and encouraged them to send in their responses.

Data analysis

One of the advantages of using Google Forms is that it computes figures and frequencies and presents them in graphical form. Therefore, after submitting their answers, the respondents’ data were summarized and presented graphically without intervention on the researcher’s part. The collected data from the participants were analyzed both quantitatively and qualitatively. For the close-ended items, percentages were calculated whereas thematic analyses were applied for the qualitative data. They were presented along with the quantitative findings.

Results

In this section, the findings of the 10 close-ended questions and the responses to the open-ended questions are presented.

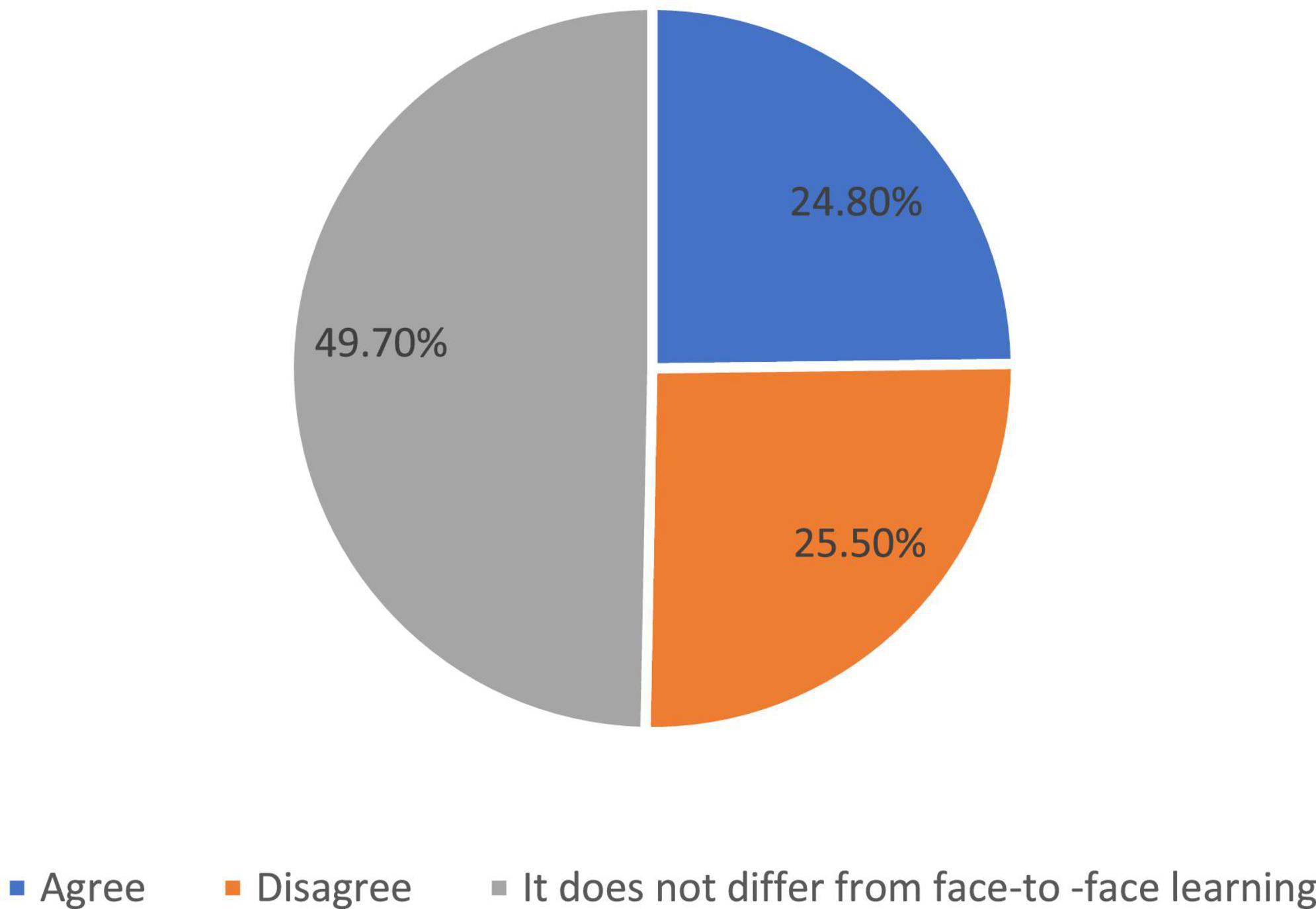

Virtual learning is more difficult with respect to reading skills

Figure 1 shows students’ opinions regarding acquiring reading skills through online learning.

The figure shows that half of the participants (49.7%) perceived that online learning did not differ from conventional learning in this matter. A quarter of them (25.5%) did not agree that studying/learning the reading skill were more difficult virtually. Similarly, the same percentage of the participants (24.8%) agreed that learning reading skills was more difficult in the online mode.

What are the reasons for your answer?

Students explained their answers by stating the following reasons:

1. Because virtual learning does not differ from face-to-face learning.

2. Sometimes, there is no observer to correct the student’s mistakes in reading.

3. Considering reading skills, students prefer to be warmed up before reading and to feel psychologically comfortable. Virtual learning provides such preparation and comfort.

4. Face-to-face learning is better to get more benefits.

5. Virtual learning is more difficult.

6. Reading skills are not an issue.

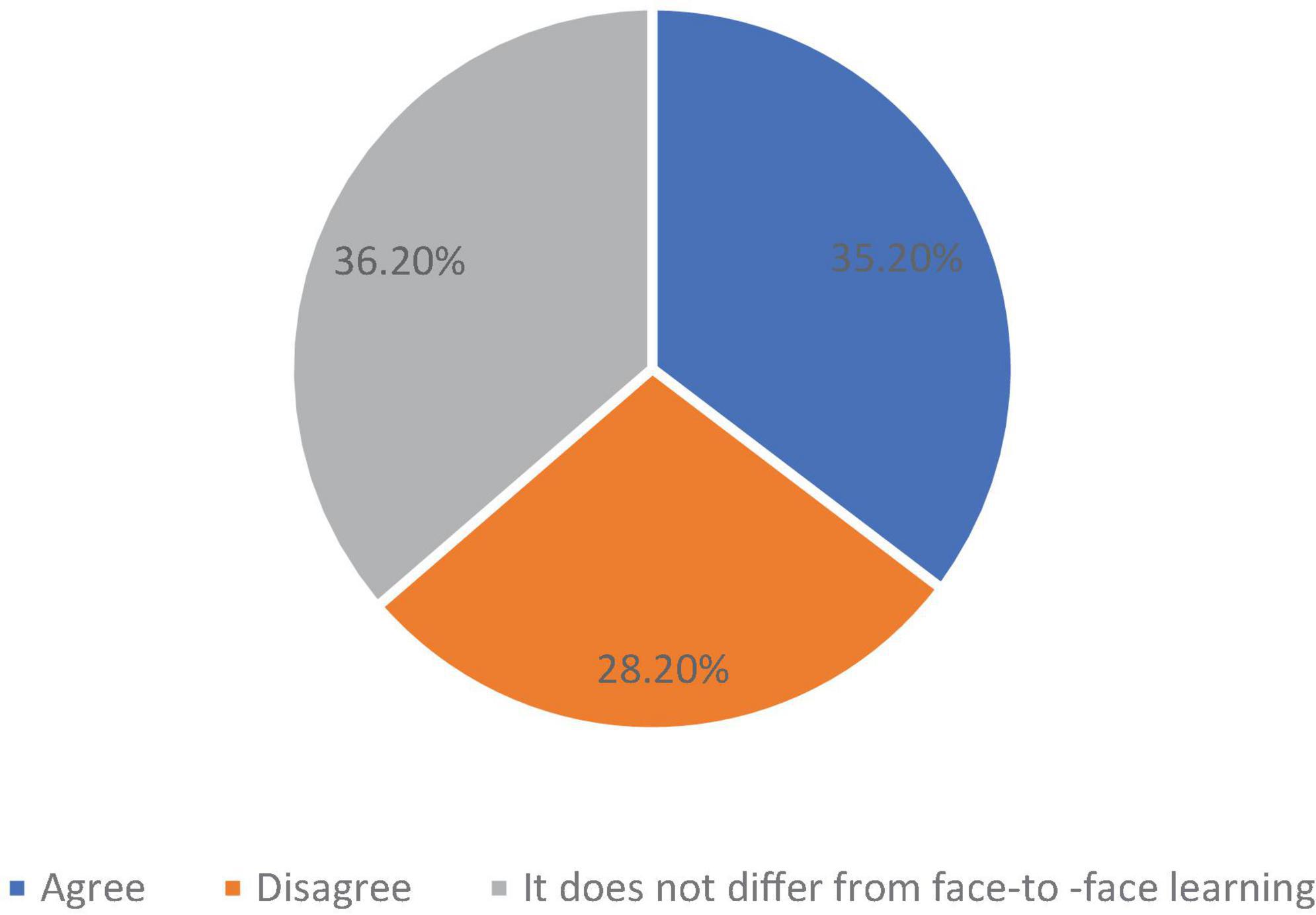

Virtual education is more difficult with respect to writing skills

Figure 2 shows the students’ opinions regarding acquiring writing skills through virtual learning.

Figure 2 shows that 36.2% of the respondents perceived that acquiring writing skills virtually did not differ from conventional learning. Nearly the same percentage (35.2%) of them agreed that this was more difficult virtually. In contrast, 24.8% of the students did not agree that acquiring writing skills were more difficult virtually.

What are the reasons for your answer?

Students provided the following reasons for their opinions:

1. Because virtual learning does not differ from face-to-face learning.

2. I think writing skills depend on self-effort.

3. All in all, we will get ourselves trained on the tasks and assignments. Nothing more is required from us.

4. Because there is a difference between virtual and face-to-face learning in explaining and understanding the lessons.

5. Because I use google translate in my writing in the beginning till I become dependent on myself later. Such dependency on Google minimizes my writing ability.

6. Virtual learning is difficult, especially in producing correct spellings.

7. Practice makes it easier.

Virtual learning is more difficult with respect to listening skills

Figure 3 shows the students’ opinions regarding learning listening skills through virtual learning.

Figure 3 shows that 33.6% of the participants did not agree that acquiring listening skills is more difficult virtually. Furthermore, 30.9% of them reported that acquiring listening skills virtually did not differ from acquiring them through conventional learning. Furthermore, the same percentage (30.9%) of them agreed that acquiring listening skills was more difficult virtually.

What are the reasons for your answer?

Students provided the following reasons for their answers:

1. Because virtual learning does not differ from face-to-face learning.

2. Listening skills improve through listening to lectures, so there is no difference whether the lectures are virtual or face-to-face. Moreover, listening skills can be improved because of the many available tools.

3. Because of the technical problems.

4. No difference.

5. When I hold my mobile, I can only listen without concentration. Such a thing I could not control; I felt sleepy and missed many points.

6. There are many programs/applications which students can use to improve their listening skills.

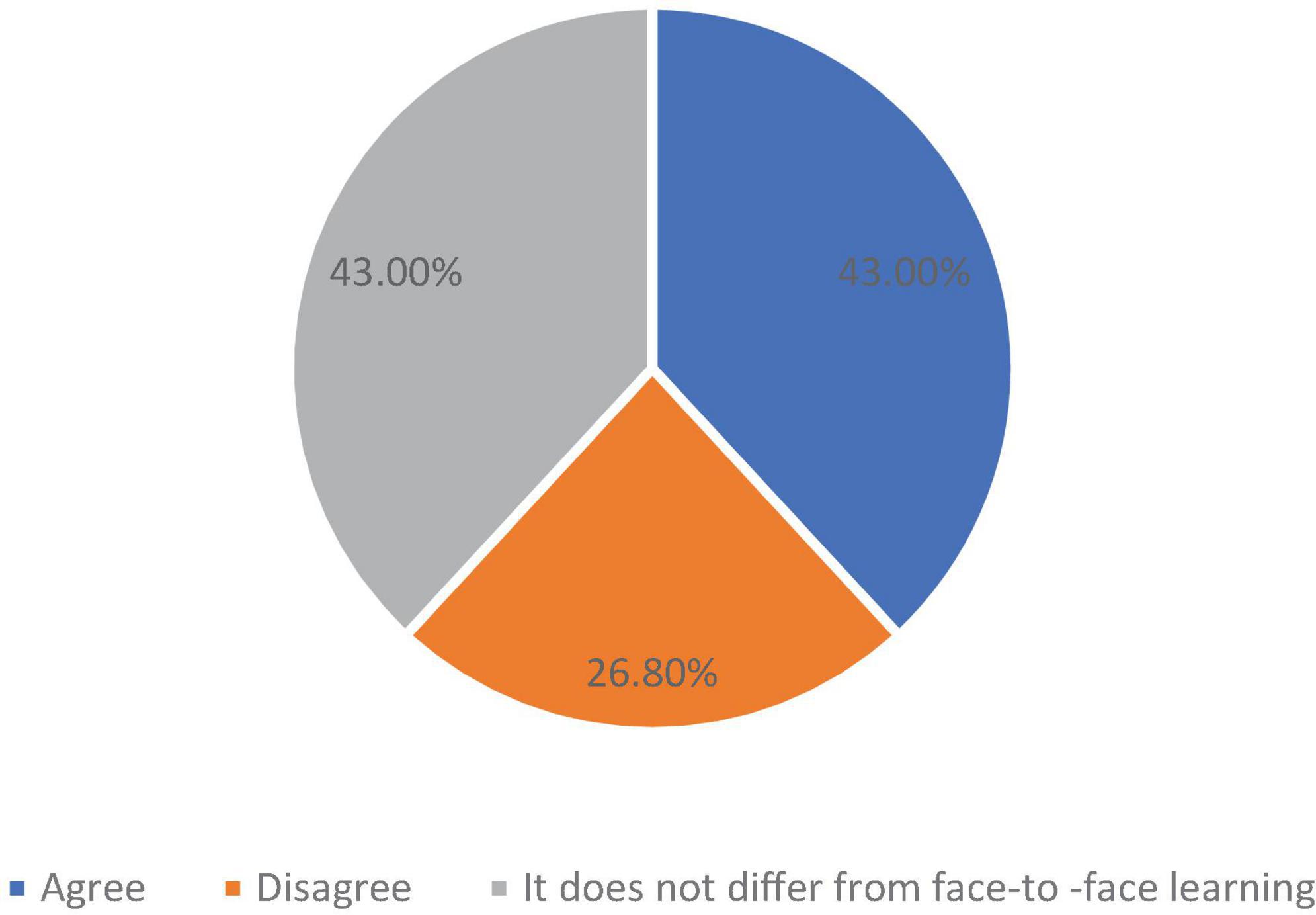

Virtual learning is more difficult with respect to speaking skills

Figure 4 shows the students’ opinions regarding learning speaking skills through virtual learning.

Figure 4 shows that 43% of the participants agreed that acquiring speaking skills through virtual learning was more difficult. Furthermore, the same percentage (43%) of them reported that acquiring speaking skills virtually did not differ from acquiring them through conventional learning. In contrast, 26.8% of them did not agree that acquiring speaking skills was more difficult virtually. This implies that it was easier for them.

What are the reasons for your answer?

Students reported the following reasons:

1. Because virtual learning does not differ from face-to-face learning.

2. Speaking is very difficult to be learned virtually because in virtual learning there is no direct practice. In face-to-face learning, we discuss more and speak more.

3. There is no difference.

4. Visual communication is an important element in conversation and explanation. Eye contact is the most important thing we need to understand in the conversation. Such semiotic language is missed in virtual learning.

5. A student can practice speaking outside the learning institution.

6. It is easier because a student feels less stressed. However, problems in audio hardly occurred.

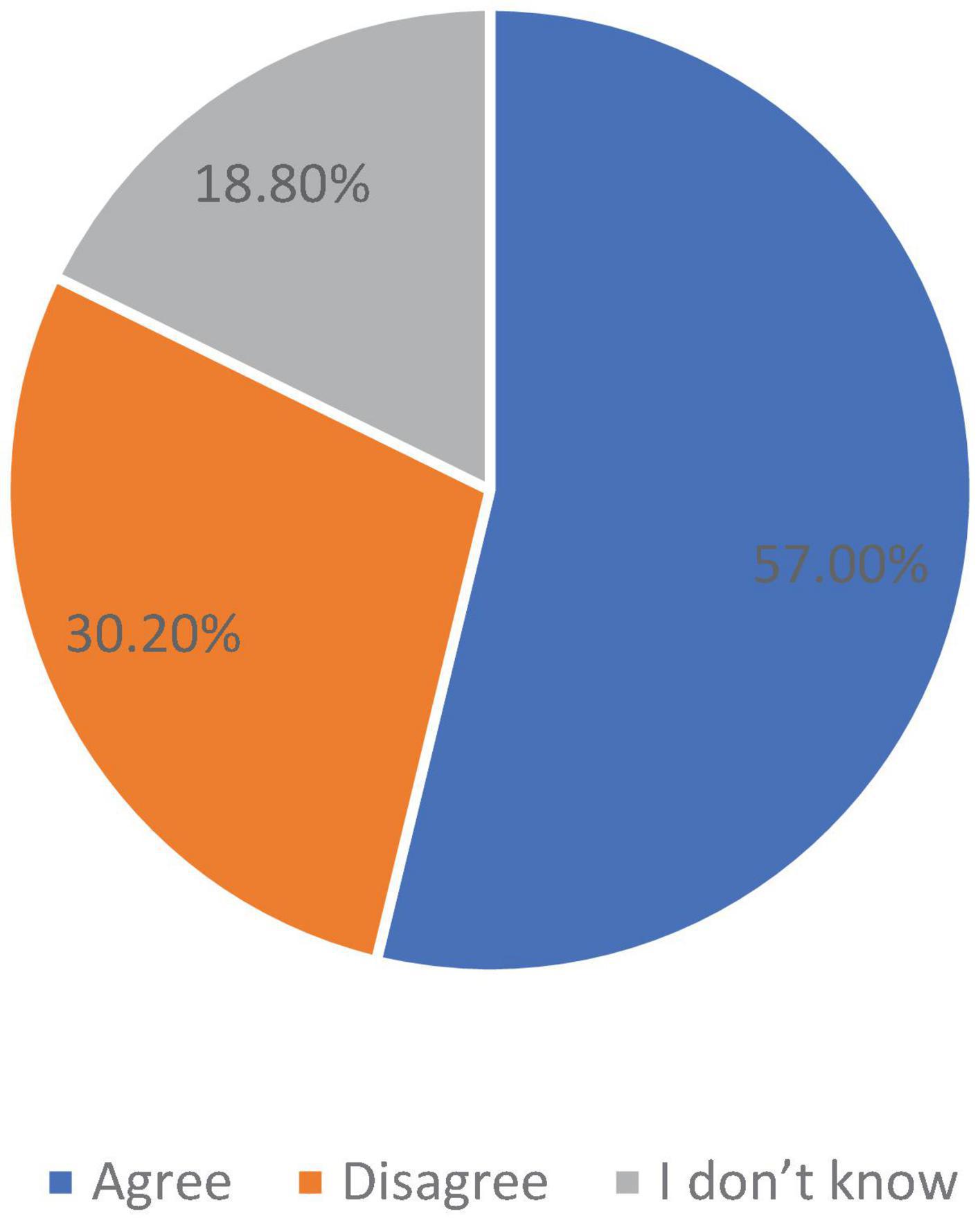

Virtual education enables me to become more self-dependent in learning English

Figure 5 shows the students’ opinions about the self-dependency they acquired to learn English virtually.

Figure 5 shows that 57% of the participants agreed that virtual learning urged them to become more self-dependent in learning English. In contrast, 30.2% of the students did not agree with the benefit of virtual learning related to increasing students’ self-dependency in learning English. Finally, 18.8% of them did not show any opinion. They did not know whether virtual learning increased or not their self-dependency in learning English.

What are the reasons for your answer?

Students reported the following reasons:

1. It makes me more curious.

2. I did not depend only on the professor’s information; I myself searched for other ways/methods to learn English.

3. Virtual learning reduced the interest I previously had to learn English. It is not real learning.

4. Sometimes virtual learning is not clear.

5. Sometimes virtual learning is better if a student makes more effort.

6. Various learning sources are very important in virtual learning. Moreover, it is more interesting when I get much beneficial information. Likely, I can search more and learn more.

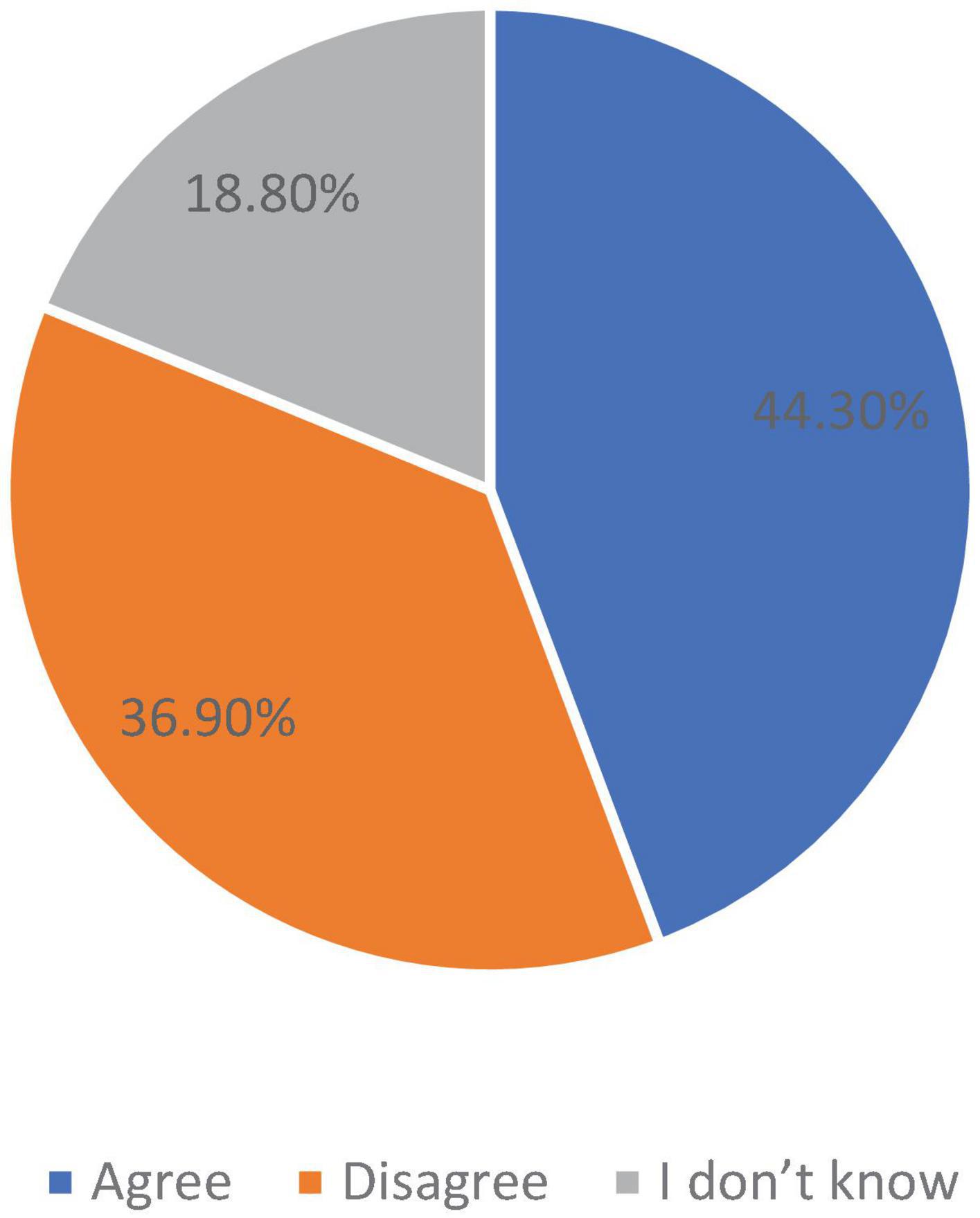

Virtual education opens new dimensions for me to learn the English language

Figure 6 shows the students’ opinions about the new dimensions they acquired by learning English through the virtual platform.

Figure 6 shows that 44.3% of the participants agreed that virtual learning opened for them new dimensions to learn English. In contrast, 36.9% of the students did not agree that virtual learning opened new horizons in learning English. Finally, 18.8% of them did not show any opinion. They did not know whether virtual learning opened new dimensions or horizons in learning English.

What are the reasons for your answer?

The following reasons were reported that explained the students’ attitudes:

1. Virtual learning urges us to search for information and reinforces self-learning.

2. I discovered new ways and methods for learning and development suiting me. They did not let me feel bored; they made me go on learning.

3. It does not suit me.

4. It does not differ.

5. I practice new applications.

6. I do not know whether it is true or not.

7. I did not know what to revise.

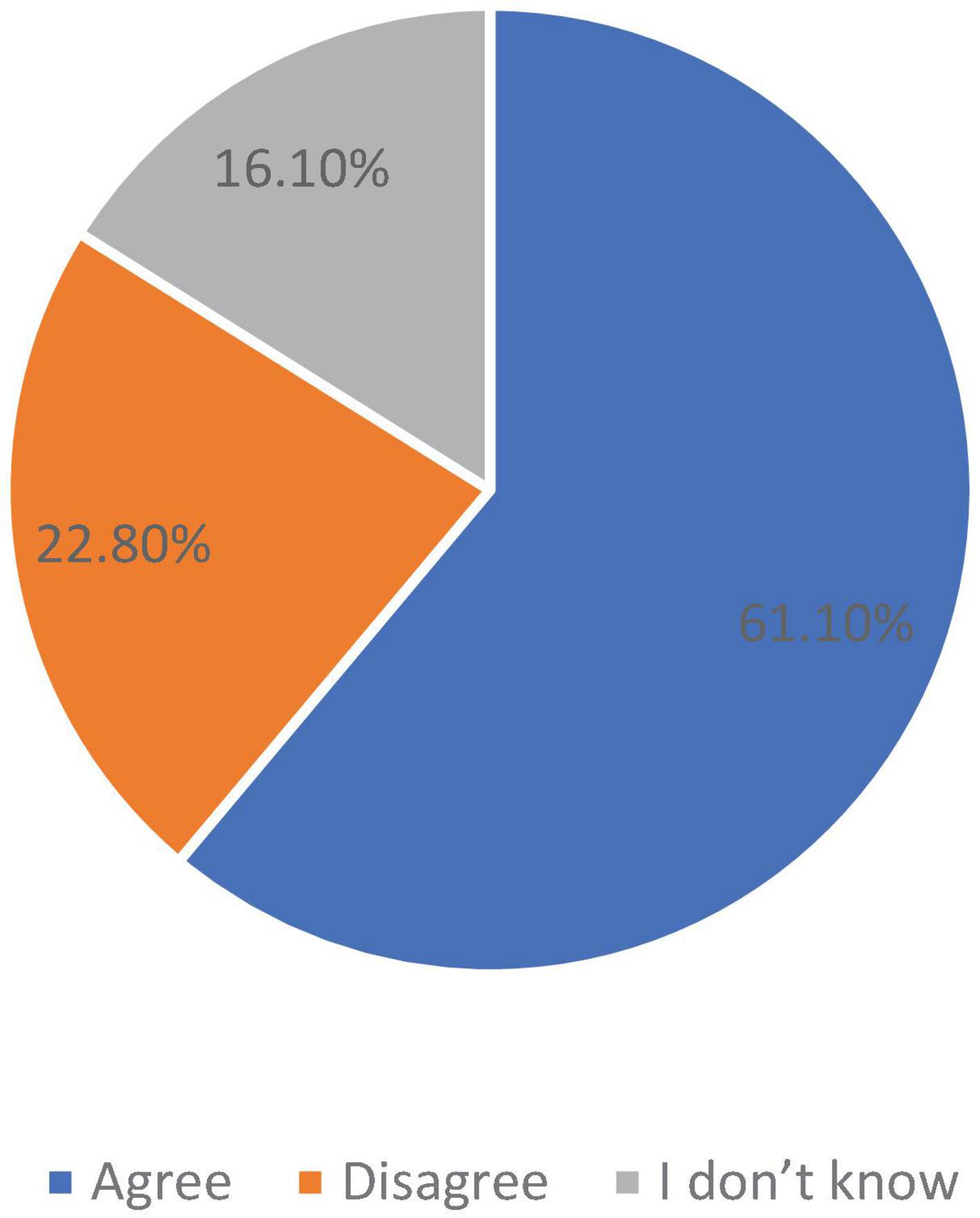

Virtual learning makes me believe in the possibility of learning the English language. Virtual learning enables everyone to learn independently

Figure 7 shows the students’ opinions about the new belief they acquired about the possibility to learn English through the virtual platform.

Figure 7 shows that 61.1% of participants agreed that everyone could learn English virtually. In contrast, only 22.8% of the students did not agree with the possibility to learn English through virtual education. Finally, 16.1% of them did not show any opinion. They were unsure whether it was possible for anyone to learn English virtually.

What are the reasons for your answer?

Students reported the following reasons:

1. Because it is easy.

2. I strongly agree because English language learning is a skill and creativity; every person can learn by themselves. I thought that I could not learn English, but I discovered the opposite. I acquired the four language skills during the academic year.

3. It does not exist.

4. Every person can learn the English language independently if they have an interest. Virtual learning makes me believe in this view because I experienced it before.

5. It is something interesting for me.

6. Every person can learn and develop themselves.

7. It is not a logical reason.

8. Virtual learning is not the reason for my self-dependency on English language learning.

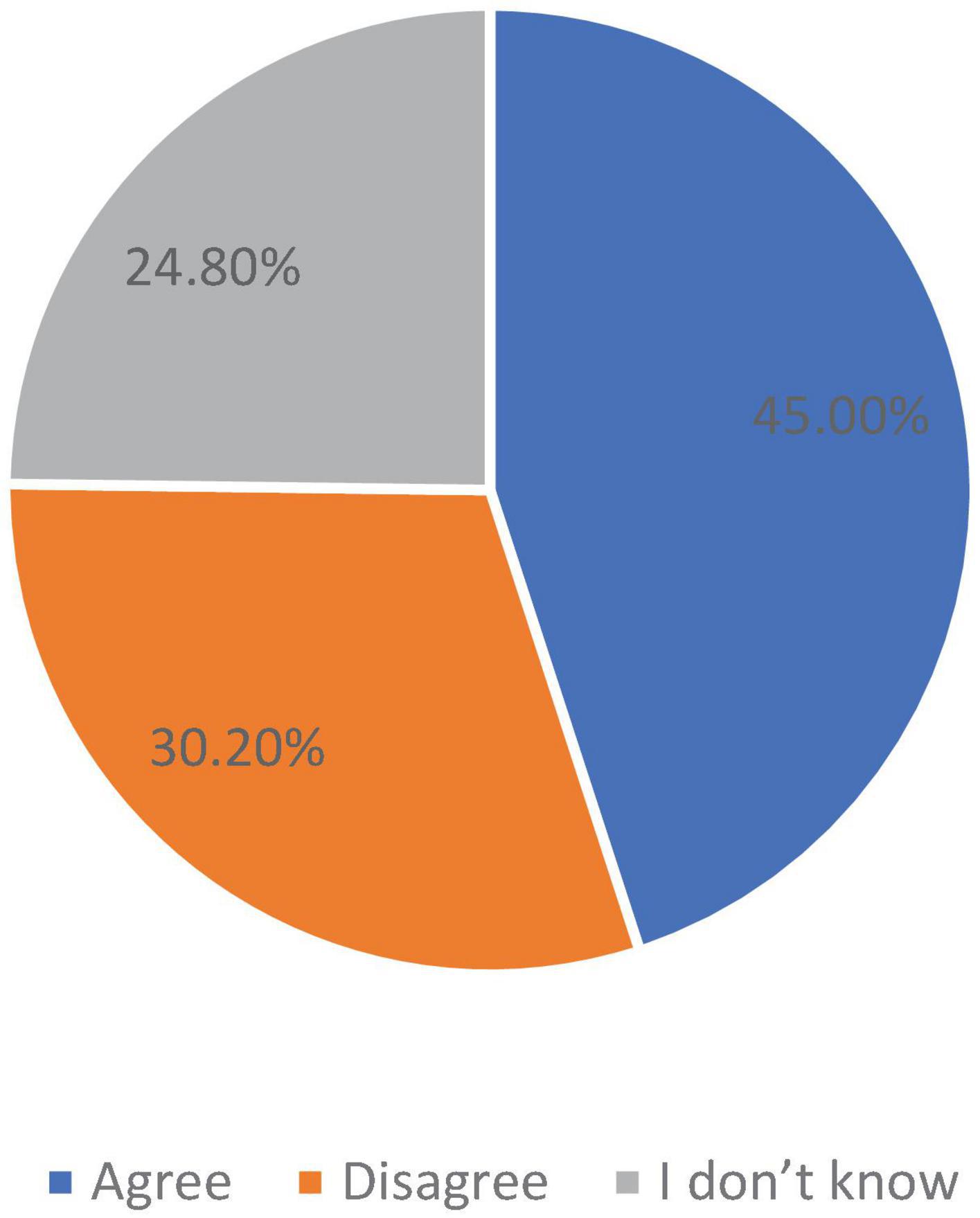

My conviction about learning English changed after the COVID-19 pandemic

Figure 8 shows the students’ changeable convictions on virtual learning after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 8 shows that 45% of the participants agreed that their convictions on virtual learning had changed after they experienced virtual learning during the pandemic. In contrast, 30.2% of the students did not agree that their conviction on virtual learning had changed after the pandemic. Finally, 24.8% of them did not show any opinion. They did not know whether their conviction had changed or stayed the same as it was before the pandemic.

What are the reasons for your answer?

Students reported the following reasons:

1. My conviction did not change.

2. Because virtual learning is easy.

3. Before the pandemic, my way of revision was wrong; I did not have the motivation to develop my English language, but after the COVID-19 pandemic I learned the correct way of revision and I discovered that English language learning is easier than what others think.

4. Convictions are changeable. The pandemic has no relationship with convictions.

5. My English language becomes weaker.

6. It depends on the person.

7. It is not real.

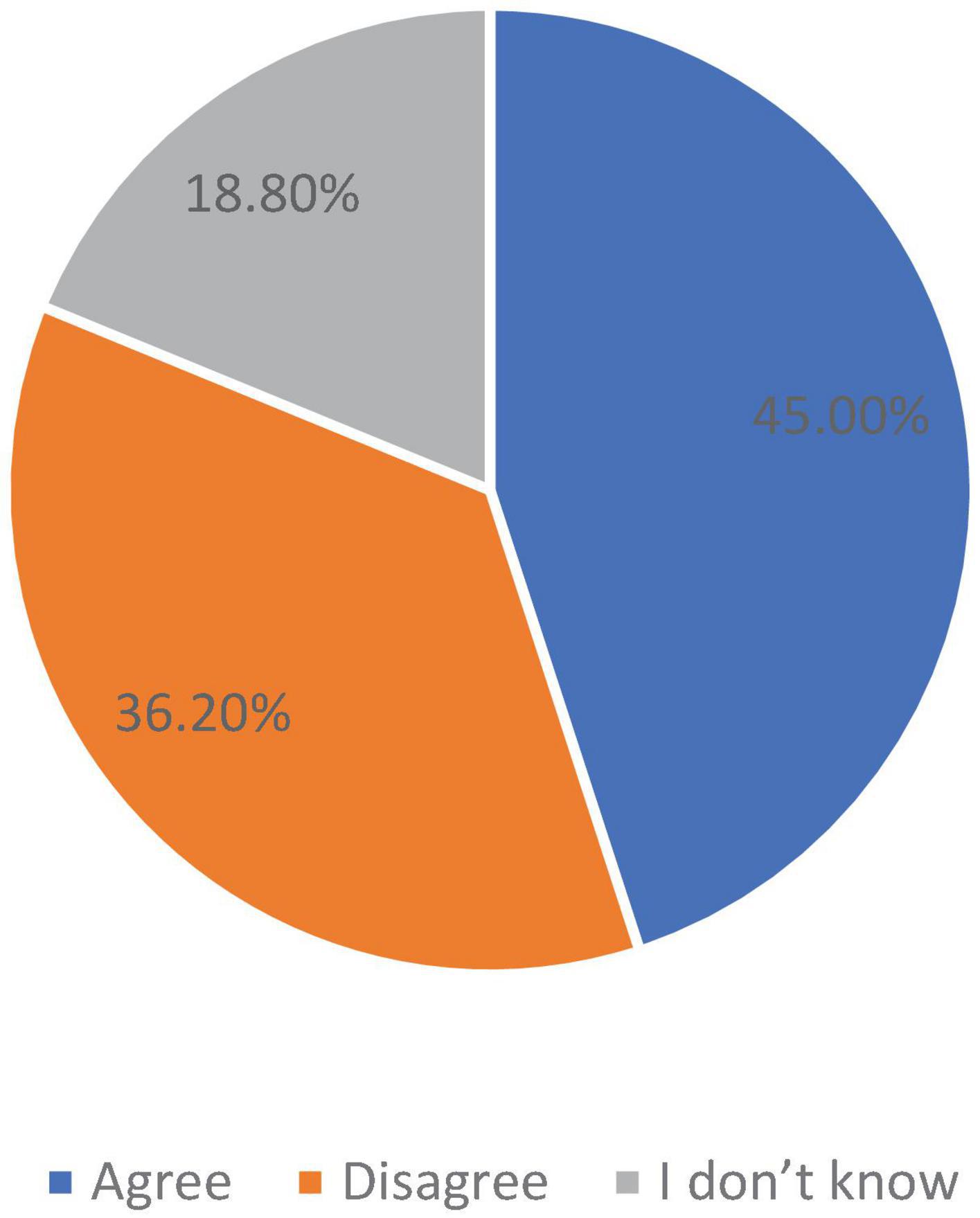

After the COVID-19 pandemic, I think it is important to use virtual learning for English language acquisition

Figure 9 shows the students’ opinions about the importance of using virtual learning after the COVID-19 pandemic in acquiring the English language.

Figure 9 shows that 45% of the participants agreed that it was important to receive virtual education in acquiring the English language after the pandemic. In contrast, 36.2% of the students did not agree with the importance of virtual learning in online English learning after the pandemic. Finally, 18.8% of them did not show any opinion. They did not know whether it is important to continue learning English virtually after the pandemic or to use conventional classrooms.

What are the reasons for your answer?

Some of the students’ reasons to support their opinions are as follows:

1. We did not understand the courses delivered through virtual learning and they preferred to study them conventionally. According to me, it is better to attend them together giving more space to conventional learning.

2. It is a huge mistake and a bad decision.

3. The reality of learning occurs by attending class. I am convinced by this as I have accustomed to it.

4. I did not only talk about English language learning. Virtual learning is not a good environment, even the word environment should not be used because many learning elements have been missed.

5. We (the students) as human beings are thirsty for the knowledge needed to communicate with each other in real life, not in front of hardware, we “need” to make eye contact.

6. Obtaining virtual learning supports students to learn some skills.

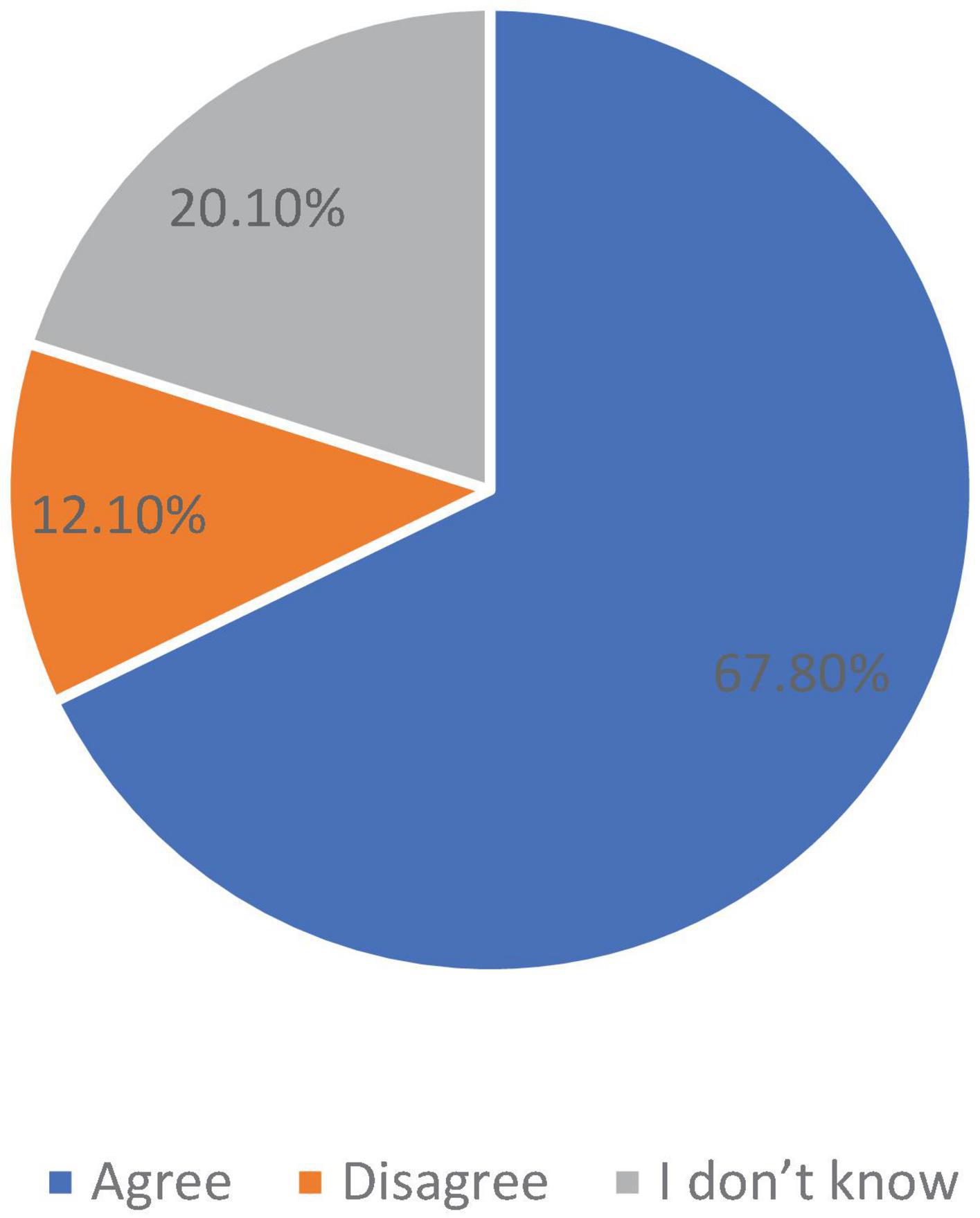

After the COVID-19 pandemic and returning to conventional classrooms, I will apply the skills that I have learned through virtual learning to English language acquisition

Figure 10 shows the students’ opinions on the application of the skills they acquired from virtual learning during the COVID-19 pandemic to acquiring the English language.

Figure 10 shows that many students (67.8%) agreed that they would apply the skills that they had learned virtually to conventional learning. Nevertheless, 20.1% of them did not show any opinion. They did not know whether they would apply the skills learned in virtual education to their face-to-face English language learning or not. Finally, just 12.1% of the participants did not agree that they would apply the skills learned during online learning to learning English after the pandemic in conventional classrooms.

What are the reasons for your answer?

Students reported the following reasons:

1. Because the skills we learned virtually are very beneficial.

2. I became cleverer and more skilful, gained more experience in discussions, and my writing and listening comprehension abilities increased.

3. Nothing learned.

4. There are no skills for me.

5. It depends on my work and abilities.

6. We can tell you about that later on.

7. I did not acquire any skills from virtual learning; I did not feel any improvement in my English.

Write down some notes/views on your virtual learning experience not mentioned in the answers to the questionnaire

1. It is a good and interesting experience.

2. First, my English language learning became more flexible and easier. Second, conventional mid-term and final examinations sharpened my English language ability as the examiner made open-ended questions to include the whole syllabus.

3. Virtual education is frustrating. I did not feel like studying. In my entire life, I will not forgive those who caused me to study some online courses.

Discussion

The findings can be divided into two main sections: the students’ attitudes toward learning English online as a whole and their actual experiences learning the four skills online.

Students’ attitudes toward learning English online

Figures 5–10 show that the students overall had a positive attitude toward online learning. Such positivity stems from the benefits that online learning provides. For example, McKeown et al. (2022) point out that online learning provided students with safety, convenience, and flexibility. Similar findings were reported by Alamer (2020) and Almekhlafy (2020) who investigated the students’ perceptions and attitudes toward learning English using Blackboard. Both studies found that those who had prior experience using the Blackboard for learning and had been familiar with the platform showed more positive attitudes toward using it as an English learning tool compared to those who had no experience using it before. Furthermore, the findings of the current study demonstrate that the students’ positivity toward online learning extends to their willingness to continue adopting online learning even after COVID-19 restrictions are lifted.

The students’ attitudes toward acquiring the four language skills

Figures 1–4 show the students’ attitudes toward their process of learning the four language skills. The findings in this study are consistent with the findings of Almekhlafy’s (2020) study, which reported that the students believed that online learning improved reading and listening but not writing and listening. However, Almekhlafy (2020) does not provide a sufficient explanation regarding why this was the case. In the current study, the students were given the opportunity to explain the reasons behind their preferences.

Considering receptive skills, such as reading and listening, the students—although by a small margin—preferred online learning to traditional face-to-face classrooms. Their preference may be attributed to numerous online resources for accessing and practicing their reading and listening skills on their own without assistance from their instructors. Furthermore, any reading or listening materials can be saved to be accessed online when convenient.

In contrast, the students showed different attitudes toward online learning related to the productive skills of writing and listening. Regarding writing, those who preferred face-to-face classrooms justified their choice by stating that they needed their instructors’ assistance to help them improve their writing skills. Others explained that learning skills online led them to depend on translation apps which hindered their writing improvement, whereas others complained that they needed constant evaluation of their spelling errors from their teachers. Nevertheless, the difference between those who preferred face-to-face classrooms to online learning concerning writing remains relatively small because most online platforms have in-built spell-checking tools.

Concerning speaking, however, the gap between those who preferred face-to-face classrooms to online learning was the widest among all the four skills. Some of the students complained about the lack of speaking practice in online learning. Others explained that body language, such as eye contact, was missing in online learning. Sato and Ballinger (2016) argue that face-to-face classrooms can function as a dynamic and productive environment for students to practice their English naturally. Therefore, more group work is required for speaking practices, which is difficult to achieve in online learning (Adnan and Anwar, 2020). Moreover, what the students referred to as the lack of body language and eye contact in online learning is what Tavares (2022) refers to as “meaningful social interaction” (p. 95). He argues that to maintain meaningful social interaction, individuals need to create a sense of community that can only be naturally achieved in face-to-face classrooms.

The significance of a strong sense of community to meaningful social interaction for multilingual international students in online environments cannot be overstated. Multilingual students may feel more motivated to participate in their learning environments if their relationships with their peers are characterized by quality and familiarity, and if group cohesion is present…Unstructured face-to-face interactions that occur within the physical classroom contribute majorly to bringing a group together. However, replicating this experience digitally is often difficult unless thoughtfully devised opportunities are present (Tavares, 2022).

Tavares (2022) illustrates this idea by stating that even after his students had known one another, and therefore, had established a sense of community, they seemed almost like strangers to each other when online learning commenced after the pandemic struck. They were less engaged in class activities and would not take part in any activity unless they were called out by their names to participate.

Therefore, the findings show that the students had more positive attitudes toward the receptive skills of reading and listening to be practiced online because both skills depend entirely on the learner and can be practiced on their own. Students did not respond positively to productive skills, such as writing and speaking. They needed their instructors’ assistance to constantly check their writing, whereas concerning speaking, online learning created an undynamic and unnatural setting that hindered the students’ opportunities to practice their speaking skills with their peers.

Conclusion and implications

This study investigated the perceptions of 149 university students studying English at a Saudi state university. It demonstrated that most of the respondents perceived online learning positively and believed that it was a great opportunity for their language learning process. However, considering learning the four language skills, their perceptions differed. The students believed that online learning enabled them to acquire and practice the receptive skills of listening and reading, and therefore, they were positive about the practice. However, both productive skills of writing and speaking were not met with the same positivity because the students required constant assistance from their instructors to guide them and help them improve their writing skills, whereas they needed a more natural and meaningful social setting to practice their speaking skills with their peers, which was only possible in face-to-face classrooms.

Two conclusions can be made from this study and can be used for practical implications. First, the students do not entirely oppose online learning. Rather, they oppose the limited features that it provides them with. Therefore, any current or future online platform needs to include sophisticated features that facilitate the learning process and simulate face-to-face classrooms to compensate for the lack of natural and social interaction. Second, online learning should not be perceived as a temporary measure taken by governments during the pandemic. Instead, it should continue after the pandemic is over regardless of whether the restrictions have been relaxed or even lifted.

Recommendations

The advantageous opportunities that online learning has provided should be recognized and utilized after the pandemic is over. One can never predict any future natural disasters, disruptions, or even other pandemics to emerge, and therefore, educational systems worldwide must be equipped with advanced online platforms for education to continue without the state of panic that many countries had to encounter at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. This study recommends the importance to foster students’ four language skills in whatever learning mode is used, but with the inclusion of the online component for specific skills. Online-course designers, teachers, and methodologists should make room for learners to practice language learning skills.

Limitations

The study had a mixed-gender sample with almost equal numbers of male and female participants. However, the role of gender in the difference of perception was not evaluated here and this was one of the limitations. Similarly, perceptions may be different when the learning platforms are changed and this must be considered in future studies.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Deanship of Scientific Research, King Faisal University. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

MA investigated the overlooked opportunities that online learning has brought during the pandemic, argued that these benefits can continue to be utilized after the pandemic is over, especially in English language classes, and provided the grounds for future research on online language learning in higher education to assess the achievement of English language learners during and after the pandemic.

Funding

This study was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia for financial support under the Ambitious Researcher Track (Grant No. 1198).

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the English language students who took part in this study. The author would also like to thank and express appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia for the financial support under the Ambitious Researcher Track (Grant No. 1198).

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abduh, M. Y. M. (2021). Full-time online assessment during COVID-19 lockdown: EFL teachers’ perceptions. Asian EFL J. 28, 26–46.

Adnan, M., and Anwar, K. (2020). Online learning amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Students’ perspectives. J. Pedagogical Sociol. Psychol. 1, 45–51. doi: 10.33902/JPSP.2020261309

Al-Ahdal, A. A. M. H., and Alqasham, F. H. (2020). Saudi EFL learning and assessment in times of Covid-19: Crisis and beyond. Asian EFL J. 27, 356–383.

Alamer, H. A. H. (2020). Impact of using blackboard on vocabulary acquisition: KKU students’ perspective. Theor. Pract. Lang. Stud. 10, 598–603. doi: 10.17507/tpls.1005.14

Aldossry, B. (2021). Evaluating the madrasati platform for the virtual classroom in Saudi Arabian education during the time of Covid-19 Pandemic. Eur. J. Open Educ. Learn. Stud. 6, 89–99. doi: 10.46827/ejoe.v6i1.3620

Alkinani, E. A., and Alzahrani, A. I. (2021). Evaluating the usability and effectiveness of madrasati platforms as a learning management system in Saudi Arabia for public education. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Netw. Sec. 21, 275–285.

Almekhlafy, S. S. A. (2020). Online learning of English language courses via blackboard at Saudi universities in the era of COVID-19: Perception and use. PSU Res. Rev. 5, 16–32. doi: 10.1108/PRR-08-2020-0026

Alolaywi, Y. (2021). Teaching online during the COVID-19 pandemic: Teachers’ perspectives. J. Lang. Ling. Stud. 17, 2022–2045. doi: 10.52462/jlls.146

Alqahtani, M. H. (2022). Post pandemic Era: English language teachers’ perspectives on using the madrasati e-learning platform in Saudi Arabian secondary and intermediate schools. World J. Engl. Lang. 12, 102–116. doi: 10.5430/wjel.v12n2p102

Al-Thumairy, A. (2020). Ba’ad. Asabee’a…Minassat Madrasati Wa Alta’aleem a’an Bu’ad Yatajawazan Marhalat Alkhatar [After 5 Weeks…Madrasati Platform and the Ministry of Education Pass the Danger Zone]. Al Eqtisadiah. Available online at: https://web.archive.org/web/20201101212841 (accessed January 21, 2022).

Alubthane, F. O. A. (2021). Saudi school education during the COVID-19 pandemic: The madrasati platform. Sci. J. King Faisal Univ. Basic Appl. Sci. 22, 316–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2021.104059

Bailey, D. R., and Lee, A. R. (2020). Learning from experience in the midst of COVID-19: Benefits, challenges, and strategies in online teaching. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. Electron. J. 21, 178–198.

Hammond, S. M., Aartsma-Rus, A., Alves, S., Borgos, S. E., Buijsen, R. A. M., Collin, R. W. J., et al. (2021). Delivery of oligonucleotide-based therapeutics: Challenges and opportunities. EMBO Mol. Med. 13:e13243. doi: 10.15252/emmm.202013243

Hazaea, A. N., Bin-Hady, W. R. A., and Toujani, M. M. (2021). Emergency remote English language teaching in the Arab League countries: Challenges and remedies. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. Electron. J. 22, 201–222.

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., and Bond, A. (2020). The Difference Between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. Educause Review. Available online at: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergencyremote-teaching-and-online-learning (accessed April 14, 2022).

Kitishat, A. R., Al Omar, K. H., and Momani, A. K. A. (2020). The Covid-19 crisis and distance learning: E-teaching of language between reality and challenges. Asian ESP J. 16, 316–326.

McKeown, J. S., Bista, K., and Chan, R. Y. (2022). “COVID-19 and higher education: Challenges and successes during the global pandemic,” in Global higher education during COVID-19: Policy, society, and technology, eds J. S. McKeown, K. Bista, and R. Y. Chan (Star, ID: STAR Scholars), 1–7.

Milne, G. J., Xie, S., and Poklepovich, D. (2020). A modelling analysis of strategies for relaxing COVID-19 social distancing. medRxiv [Preprint] doi: 10.1101/2020.05.19.20107425

Sato, M., and Ballinger, S. (2016). “Understanding peer interaction,” in Language learning and language teaching, eds M. Sato and S. Ballinger (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company), 1–30.

Shishah, W. (2021). Fake news detection using bert model with joint learning. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 46, 9115–9127. doi: 10.1007/s13369-021-05780-8

Tavares, V. (2022). Neoliberalism, native-speakerism and the displacement of international students’ languages and cultures. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 1–14. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2022.2084547

Thompson, M. C. (2022). “Societal perceptions of the saudi government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic,” in COVID-19 and a World of ad hoc Geographies, eds S. D. Brunn, and D. Gilbreath (Cham: Springer), 283–300.

Unified National Platform [UNP] (2021). Madrasati is a Unique Global Model Compared to the Top Platforms in 174 Countries. Available online at: https://web.archive.org/web/20210829230604/https:/www.my.gov.sa/wps/portal/snp/content/news/newsDetails/CONT-news-290820211 (accessed January 19, 2022).

Keywords: COVID-19, online learning, English as a second language, higher education, learner autonomy

Citation: Alqahtani MH (2022) Every cloud has a silver lining: The experience of online learning in English language classes at Saudi universities in the post–COVID-19 era. Front. Educ. 7:1027121. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1027121

Received: 12 September 2022; Accepted: 17 October 2022;

Published: 15 November 2022.

Edited by:

Hassan Ahdi, Global Institute for Research Education & Scholarship, Amsterdam, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Nazish Naz, Quaid-i-Azam University, PakistanArif Ahmed Mohammed Hassan Al-Ahdal, Qassim University, Saudi Arabia

Copyright © 2022 Alqahtani. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Muneer Hezam Alqahtani, bWhhbHFhaHRhbmlAa2Z1LmVkdS5zYQ==; orcid.org/0000-0001-5676-2221

Muneer Hezam Alqahtani

Muneer Hezam Alqahtani