- University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE, United States

This qualitative interpretative phenomenological analysis explored the lived experience of mother executive administrators in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Utilizing the philosophical underpinnings of the Heideggerian phenomenological approach, the following research question guided this study: What are the lived experiences of mother executive administrators in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic? Participants included nine self-identified mother executive administrators from one Midwest state at a variety of institution types and locations within the state. Data collection involved two focus groups and individual interviews with all nine participants. After data analysis, three recurrent themes emerged from the data: (1) Burnout and Exhaustion, (2) Never Enough: Responsibility Generated Feelings of Guilt, and (3) Receiving Support: Importance of Gender, Family Role, and Agency. The findings of this study exposed the neoliberal feminist and capitalistic ideological stronghold on the United States workforce and culture intensifying the already existing challenges of these mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

The early 2020s presented a variety of social and political crises and movements such as nationalist extremism, anti-racist and anti-colonial advocacy movements, and the COVID-19 pandemic, placing a spotlight on leadership, policy, and inequities. During the COVID-19 pandemic, women leaders were often commended for their leadership ability; however, this pandemic also created economic instability, referred to by some as the “she-cession” because of the disparate impact on women in the workforce due to the caregiving crisis that occurred due to lack of childcare, school closures, or safe assisted living facilities or nursing homes (Gupta, 2020).

Economists and public policy experts are concerned that the COVID-19 pandemic will put women in the workforce behind a generation (Modestino, 2020; Bauer et al., 2021). Throughout all of this, colleges and universities struggled to continue to serve students and preserve enrollments whether in their pivot to online learning or through on campus courses. Campus leaders had to navigate changing conditions, ambiguous recommendations, and the politicization of COVID-19 responses such as masking. For campus leaders who are also caregivers, this led to a potential double set of COVID-19 stressors.

With the continuance of the pandemic, it is important to understand how the pandemic plays out for mothers in executive leadership roles in higher education. Certainly, research has indicated that women have been considered successful in their leadership approach during the pandemic (Garikipati and Kambhampati, 2020; Wittenberg-Cox, 2020) yet they also have experienced the caregiving crisis with limited childcare resources and schools being closed (Gamble and Phadke, 2021). With many women leaving the workforce due to the pandemic, it is important to understand how the pandemic and resulting caregiving crisis may impact higher education with the already diminishing pipeline for leadership positions. There is a shortage of women leaders at the top in higher education where roughly 30% of American higher education institutions are led by a woman in comparison to 44% of chief academic officer roles being filled by women (Johnson, 2017).

In this study, I examined the intersection of motherhood and higher education leadership within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. This topic in its entirety has not been researched at all since a global pandemic has not occurred in our lifetime, therefore it is imperative to understand how this particular phenomenon impacts the lives of the limited number of women leaders in higher education. Due to the limited representation of not only women but mothers in higher education leadership, this study is critical to understand their lived experiences both leading and mothering during COVID-19. Gender equity is a large focus in leadership, so if it is collectively understood there are too few women positional leaders in higher education, especially mothers, there also needs to be an understanding of the impact COVID-19 had on mother leaders in higher education in light of the caregiving crisis and extra demands put on leaders during this time. If we do not fully understand the lived experiences of mother leaders in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic, we miss an opportunity to improve the outlook for mother leaders in higher education including in times of future crisis.

Literature

When you look at women leaders who are mothers in higher education, studies are minimal. Currently, there is research on women administrators (Marthe, 2009, 2010; Airini Collings et al., 2011; Dindoffer et al., 2011) and MotherScholars (Matias, 2011) or mother faculty members (Forster, 2000; Woodward, 2007; Santos and Cabral-Cardoso, 2008; Lapayese, 2012; Sallee et al., 2016). While certainly, the mother leader identity can be a component of the experiences of women administrators, the data points to a gender disparity problem in higher education leadership and the numbers also point to caregiving and parenting as one of the reasons why the industry has gender disparity at the top (American Council of Education, 2017; Johnson, 2017).

Mothers working in higher education during COVID-19

Research is still emerging related to higher education in pandemic times; however, studies have been conducted on MotherScholars’ experiences during COVID-19 both in the short-term and long-term related to career trajectory and advancement. The MotherScholars in Minello et al. (2021) study had to prioritize online teaching over research and preferred to teach asynchronous because of the ability to record their teaching any time of day, which meant they would be less interrupted by children. In turn, the fear of the future was a key theme in the study because of the changes in the organization of childcare, time restrictions, and the reduction of research work overall created a sense of inadequacy, often when MotherScholars and women in academia already have a sense of imposter syndrome (Minello et al., 2021). Additionally, the pandemic caused a sense of resentment in the participants because colleagues without children were able to continue their research and remain productive, likely contributing to their future career success in a publish or perish academic world.

From another perspective, Beech et al. (2021) took a more positive stance regarding the impact COVID-19 has had on MotherScholars. While Minello et al. (2021) discussed the lack of research productivity as an outcome of COVID-19, Beech et al. (2021) shared COVID-19 has allowed faculty to contribute knowledge in non-academic, more creative outlets such as blogs, podcasts, Op-Eds, public forums, or local media outlets. They stated, “COVID-19 is teaching us that the gap between academic knowledge and local knowledge should be closing in, not widening” (p. 629). Additionally, the pandemic has “exposed cracks in the system that highlights chronic, systemic injustices in the academy that prioritize and favor privileged identities, not excluding ourselves: highly educated, white women” (p. 629). They continue with a call to action, “The time has come to create equitable opportunities to rebalance privileged voices and identities by welcoming other perspectives and lived experiences outside the clearly defined lines of academic walls” (p. 629). Beech et al. (2021) do not discount the challenges COVID-19 presented MotherScholars, but state that living through this pandemic has allowed MotherScholars to reckon with and accept the reality of having dual roles and work to close the gap between their personal and professional lives. They call for higher education to stop “forcing women to choose which identity will take priority” (p. 630) and commit “we will no longer stand by and be treated as anything less than the brilliant, multitasking, badass mothers we are” (p. 630).

Mothering, caregiving, and working

The historical role of the mother has been to stay at home and manage the household and care for children (Thistle, 2006; Baxter et al., 2013; Horne et al., 2018). Hochschild (1989) is well known for her term “second shift” to describe the continued work parents face when they return from their income-producing work and begin their second shift caring for children, family, and managing the home. Specifically, mothers have to manage cultural expectations of family commitment and devotion, as well as strive to be the proverbial ideal worker (Williams, 2000; Blair-Loy, 2005) in what is considered an intensive mothering culture, which impacts both stay-at-home mothers and working mothers (Lamar and Forbes, 2020). Intensive mothering is a term coined by Hays (1996) which is an ideology that came about more than 65 years ago to describe the common motherhood expectations including being the primary and preferred caregiver, as well as an expert in child development. In order to practice intensive mothering, it is necessary for the mother to deprioritize her own personal and professional goals and focus solely on the needs of her children (Hays, 1996). Although this ideology seems antiquated, it remains in the fabric of our cultural expectations of mothers (Hays, 1996; Walls et al., 2016; Forbes et al., 2020). Currently, working mothers often experience additional stressors because they are expected to adhere to the intensive mothering culture, but also demonstrate strong work performance. Unfortunately, the intensive mothering culture hardly leaves room for work outside of the home and often working mothers experience judgment and criticism if their worker identity interferes with their mother identity (Guendouzi, 2006).

Caregiving crisis of COVID-19

Scholars have begun to unpack the ways in which mothers in particular carried the weight during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the United States, working mothers with young children were significantly more likely than fathers to reduce their work hours (Collins et al., 2020). Families with young and school-age children lost full-time child care and had to quickly adjust to homeschooling or remote learning, giving rise to greater negative effects on employment for mothers, but not for fathers (Petts et al., 2020). During the early stages of the pandemic, between February and April 2020, mothers of young children under 6 years old contributed to a 3.2% reduction in the labor force, while mothers with children ages 6–12 saw a reduction of 4.3% (Landivar et al., 2020). Fathers also left the workforce, but their exit rates are about 1 to 2% points lower, meaning nearly 250,000 more mothers than fathers with children younger than 13 left the workforce during the early part of the pandemic (Landivar et al., 2020). Overall, since February 2020 there has been a net loss of nearly 2.9 million jobs and women accounted for about 63% of those losses. By early 2022, male workers regained all jobs they had lost during the pandemic whereas women were still trailing behind men by 1.8 million jobs (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022). Unlike other economic downturns, like the recession of 2008, also referred to as the “recession,” the current recession has disproportionately impacted women in the labor market (Alon et al., 2020). These studies on the disparate impact on women in the workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic highlight that gender gaps are widening, not getting smaller.

Although the traditional caregiving role has historically fallen to mothers (Thistle, 2006), in a heterosexual relationship, the stay-at-home orders of the COVID-19 pandemic could have allowed men to recognize the invisible labor caregiving mothers often take on especially if they were working from home (Collins et al., 2020). Specifically examining couples who are able to telecommute, Collins et al. (2020) discovered that among these parents, those with children aged one through five, the reduction of work hours for mothers was 4.5 times larger than fathers. Therefore, when both parents were able to work from home, mothers had to scale back to help with homeschooling, housework, and other childcare related needs. Comparatively, an analysis conducted by the Hamilton Project found that moms with children aged 12 and under spent about 8 h on child care while working 6 h a day in their jobs, which is about 3 h more per day than fathers spent on child care (Bauer et al., 2021).

Burnout

Burnout has been long studied as a critical mental health problem leading to emotional and physical exhaustion, anxiety, and unproductiveness (Leiter, 1991). Burnout is defined as a

syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workspace stress that has not been successfully managed. It is characterized by three dimensions: (1) feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; (2) increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job; and (3) reduced professional efficacy (World Health Organization, 2019, para. 4).

Although burnout is officially used to frame exhaustion around one’s work according to the World Health Organization (World Health Organization, 2019), an argument can be made that home is a form of work, therefore there can be a distinction as to the type of workspace where burnout exists. For example, burnout can be felt in the workspace of home or the workspace of the out-of-home work environment. Broadly used to describe exhaustion caused by stress, burnout first became a studied phenomenon in the mid-1970s (Freudenberger, 1974). Academics have inquired about the causes of burnout and determined it is the result of prolonged stressors at work (Maslach and Leiter, 2016) and it is often associated with low job control, high workplace psychological demands (Alarcon, 2011), as well as low connection or social supports at work, and low rewards (Gluschkoff et al., 2016). Additionally, burnout has the potential to decrease creativity and commitment (Moore, 2000), increase disengagement at work (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004), and increase turnover in roles at work (Jackson et al., 1986). Research has demonstrated that although burnout is a key indicator for mental health (Leiter, 1991), depression and anxiety are separate constructs even though they may share some common features (e.g., loss of energy; Schaufeli et al., 2001). Doyle and Hind (1998) examined the increased likelihood of burnout in high-performance work systems, specifically academia; however, the specific examination of whether there is a differential burnout experience across the gender divide is lacking. Additionally, knowing work–family conflict can lead to burnout (Palmer et al., 2012), it is also important to recognize the increased workload challenge during the pandemic specifically experienced by mothers which impacted the work-family relationship and further contributed to their sense of burnout.

Methodology

The purpose of this interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) study was to illuminate the experiences of women in higher education executive administrator roles who are also mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic. By interviewing women executive leaders, I described the phenomenon of the women mothering and leading during the COVID-19 pandemic. The question, “What are the lived experiences of mothers in executive leadership roles in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic?” guided this research study.

The context of this study is both private and public higher education institutions, both 2- and 4-year institutions from one Midwestern state. The reasoning for limiting the study to one state is because I wanted to ensure some COVID-19 factors were consistent, primarily when considering the governmental guidance and higher education response especially early on in the pandemic.

Participant selection and recruitment

Through purposeful selection (Patton, 2015), I was able to gather information-rich cases to provide an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon under examination. I developed the following selection critiera to recruit participants: (a) the individual identifies as a woman, (b) the individual identifies as a mother, (c) the individual currently serves in an executive administration role at either a 4-year or 2-year institution, and (d) the individual served in the executive leadership role during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Of the 542 executive leaders in the state who received the recruitment e-mail, 37 completed the recruitment survey indicating their interest in participating in the study. Only 6–10 participants were necessary for an IPA study (Smith et al., 2009), therefore I narrowed the list of potential participants down by children’s age, geographic region, institution type, and role. I attempted to get a racially diverse representation of participants, but unfortunately, I only received one interested participant who identified as Black and her children were over the age of 22. I was able to include racially diverse families where two White participants were married to Black men.

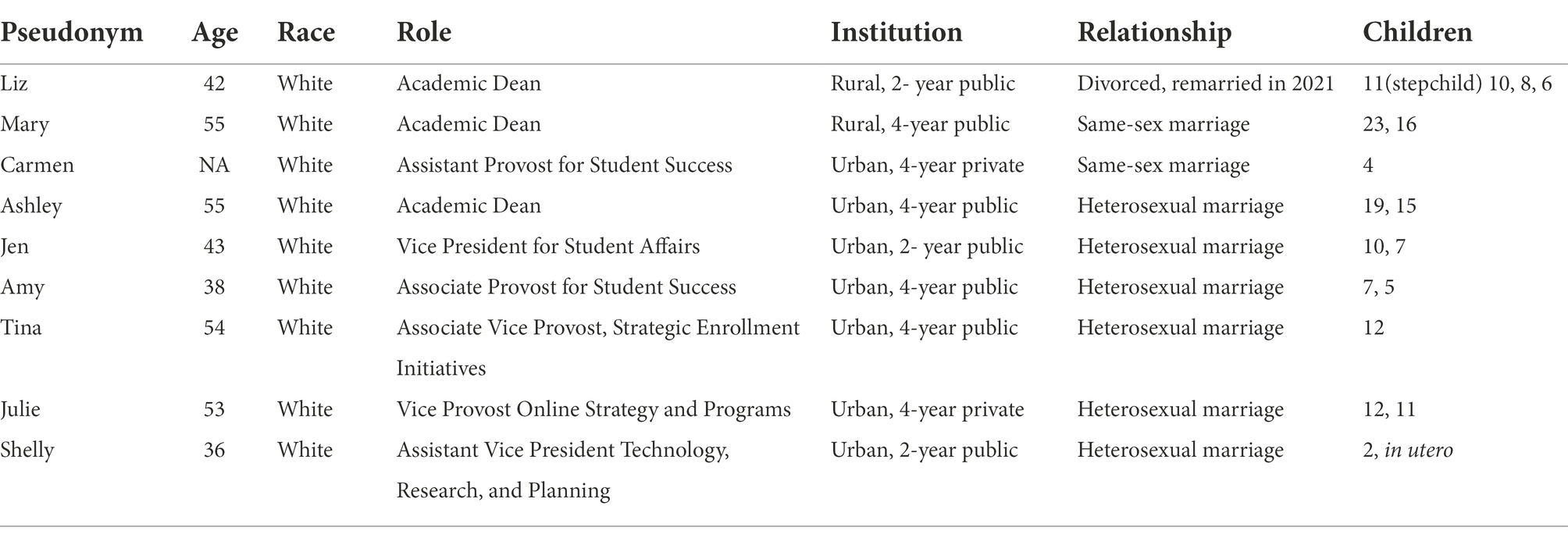

Overall, I successfully captured diversity across institution type with three two-year institutions represented and six four-year institutions. Geographically, the participants primarily came from urban areas with two working at rural institutions. Two women were in same-sex partnerships while the remaining six women were in heterosexual marriages with one of the six living as a single mother for a portion of the COVID-19 pandemic. The range of children’s ages was in utero to 23 and all of these women had three or fewer children. The women ranged in age from 36 to 55, with an average age of 47. A summary of the participant demographics can be found in Table 1.

Data collection

I held two semi-structured hour-long focus groups first via Zoom video conferencing. In the focus group, I asked questions about leading during the pandemic, parenting during the pandemic, their caregiving responsibilities, support systems, emotions, and the variance across all of these topics throughout the course of the pandemic.

In IPA, there is a strong desire to elicit detailed stories, thoughts, and feelings from the participant (Reid et al., 2005), therefore I elected to conduct a semi-structured interview after the focus group initial data collection point. The semi-structured interview allowed for the conversation to evolve as the participant desired based on their experience leading and mothering during COVID-19. The individual interview protocol began with a return to initial points of convergence or divergence in the focus group, then transitioned to a focus on the individual’s experience. I included questions around primary caregiving, meaning of motherhood, leadership shifts during the pandemic, work-family tension before and during the pandemic, as well as networks of support.

Data analysis

The data analysis process in IPA is less defined than other qualitative methods but does provide a set of common iterative and inductive processes, leading to the development of a framework illustrating the relationships between themes (Larkin et al., 2006; Smith, 2007; Smith et al., 2009). The analysis process is heavily reliant upon the hermeneutic circle where the whole of the data collection becomes sets of parts and becomes whole again in a new manner at the end of the analysis. In order to understand any given part, the whole needs to be taken into context; in order to understand the whole, the parts need to be examined. The hermeneutic circle allows for the analysis process to be iterative where the researcher “moves back and forth through a range of different ways of thinking about the data, rather than completing each step, one after the other” (Smith et al., 2009, p. 28).

Before going into detail on the data analysis, there are likely terms that are not well-known, therefore I will define them here:

Emergent theme

Produced from initial noting including the descriptive, linguistic, and conceptual notations (Smith et al., 2009).

Super-ordinate theme

“A construct which usually applies to each participant within a corpus but which can be manifest in different ways within the cases” (Smith et al., 2009, p. 166). An emergent theme will graduate to super-ordinate status through the process of abstraction where patterns have been identified between emergent themes. The super-ordinate theme is the title of the cluster of similar emergent themes.

Recurrent theme

In a larger sample size greater than six in an IPA study, Smith et al., (2009) recommended classifying super-ordinate themes to recurrent status if they are present in at least a third, or a half, or in all participant interviews. Although there are suggestions for when a super-ordinate theme transitions to a recurrent theme, there truly is no rule for recurrence and “the decision will be influenced by pragmatic concerns such as the overall end product of a research project” (Smith et al., 2009, p. 107).

In line with Smith et al., (2009) recommendation, I first analyzed the focus groups as two separate cases and then transitioned to each individual interview analysis, analyzing each case or participant separately. After the data was collected, I did a second round of coding through the two focus groups and then conducted the single case analysis with the eight individual interviews. After immersing myself in the data, I made some initial exploratory notes regarding language and semantic content on each transcript while engaging in the bridling process, or a phenomenological reduction that allows researchers to acknowledge their pre-understanding and assumptions without impacting the study outcome (Dahlberg, 2006; Smith et al., 2009).

I wrote memos after each analytic activity to engage in the bridling process to ensure I remained open to what the participants shared about their experiences and to engage in the analysis of each case as separate units. As I moved onto each consecutive case, it was important for me to bridle the ideas emerging from the analysis of the prior case in order to allow new themes to emerge with each case. No doubt, I was influenced by my emerging ideas from the prior case but that is also why I chose the IPA methodology to keep in line with my constructivist researcher role.

After coding and analyzing each of the eight interview cases and the two focus group cases, I began the cross-case analysis to search for super-ordinate themes. Utilizing abstraction, I clustered similar emergent themes together to form a super-ordinate theme and there were a few instances where I utilized subsumption where an emergent theme itself was elevated to super-ordinate status because it helped bring together a series of related themes. When I began seeing patterns across super-ordinate themes, I counted which participants exemplified the super-ordinate theme and elevated that super-ordinate theme to recurrent status given the somewhat larger sample size of this study. Smith et al., (2009) recommended that if the sample is greater than the recommended six, recurrent themes should be utilized to demonstrate how the theme is manifested across the participants which adheres to the idiographic nature of IPA. To be elevated to recurrent status, the super-ordinate theme needed to be present in at least one-third of the population, but most often in at least a half of the participants (Smith et al., 2009). This cut-off is important considering the idiographic nature of IPA where I was concerned with the individual details while also trying to make detailed and cautious universal claims about the essence of the experience.

Findings

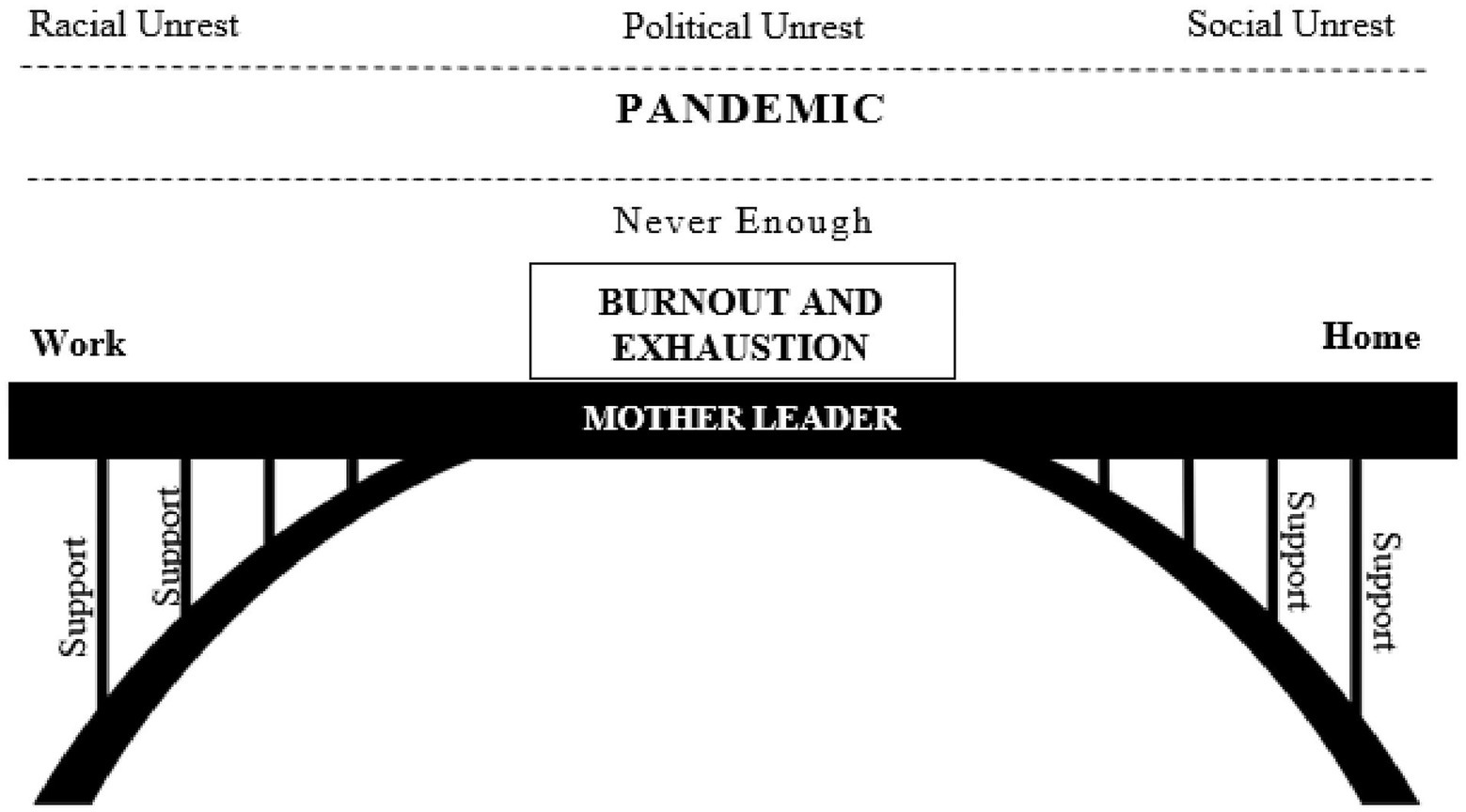

When looking at the recurrent themes of this study, one could see the findings are not dissimilar from the presumed experience of mother leaders in higher education without the COVID-19 pandemic complications. Many of the participants described challenges that were in existence for them as mother leaders prior to the pandemic but shared the pandemic exacerbated many of these pre-existing challenges. There were three overarching recurrent themes, two of which were present in all nine participants and the last overarching recurrent theme, Receiving Support: Importance of Gender, Family Role, and Agency was present in seven of the nine participants. Four super-ordinate themes were present in at least one-third of the participants. The recurrent themes that emerged through data analysis are listed below to capture the essence of the experience of being a mother leader in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, a visual representation of the way in which these themes connect to each other is presented in Figure 1.

• Recurrent Theme 1: Burnout and Exhaustion.

• Recurrent Theme 2: Never Enough: Responsibility Generated Feelings of Guilt.

• Recurrent Theme 3: Receiving Support: Importance of Gender, Family Role, and Agency.

Figure 1. The lived experience of mother executive administrators in higher education during COVID-19.

I chose the visual of a bridge connecting the home and work environments. Bridges have weight limits and the words that some participants used to describe their experience included “heavy” and “loaded.” Therefore, the first two recurrent themes appear to be compounding on top of the bridge of support, the third recurrent theme. The first recurrent theme, Burnout and Exhaustion, was felt across all nine participants and manifested in similar ways. Burnout and exhaustion is the primary weight of the women in this experience and feelings of never enough, the second recurrent theme contributes to the overall feeling of burnout and exhaustion. Participants also noted that the pandemic amplified many of their existing problems or challenges as mother leaders therefore the pandemic is layered on top of the recurrent and super-ordinate themes depicting the layered effect the participants spoke about. Coupled with the layered nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, the country and especially the state in which these participants resided experienced a great deal of racial, social, and political unrest. Therefore, layered on top of the pandemic are the terms racial unrest, political unrest, and social unrest.

Finally, these women survived their experience with the support of others which was critical certainly before the pandemic and the unrest, but even more critical during a time of crisis. However, the mother leader, or the deck of the bridge, cannot solely withstand the weight of burnout and exhaustion, feelings of never enough, or the layered effect of the pandemic and unrest which is why the decking is reinforced by the support received. All of the compounding challenges the participants experienced caused the bridge to crumble and the women were trying to repair it through more intentional mothering practices, boundary-setting at work, and their re-recognition of the importance of self-care. These women were very near to a breaking point related to their professional and home workloads before the pandemic and the pandemic exacerbated many of the longstanding challenges they have had to face.

Burnout and exhaustion

Burnout and exhaustion were felt across all nine participants. Regardless of family structure, children’s age, participant’s age, or institutional type, all of these women were burned out and exhausted. Although these sentiments were felt by all participants during the pandemic, before the pandemic, some women shared they had never experienced burnout to their knowledge during their career. Mary shared in the focus group.

I actually can’t say that I’ve experienced burnout really in my career and I just I don’t know, for whatever reason, I’ve been frustrated and professionally frustrated, but feel burned out right now. I don’t know because it keeps getting layered right?

Liz, on the other hand, had experienced burnout at work before, but she had managed to cope effectively in the past. While she had tips and tricks for helping her through periods of burnout, those were no longer working for her at this point. She shared.

I’m at the bottom of my barrel and I don’t know where to go…You know all of my tips and tricks, I’ve either used or I can’t because the pandemic is still going…It’s just we’re 2 years into a cycle of exhaustion that I don’t think any of us expected to last this long.

Mary focused on the layering complexities of COVID-19 that continued to add to her workload and Liz described a feeling of almost despair because of she did not expect the pandemic to last as long as it had, thus contributing to her overall exhaustion.

Amy struggled to find a word to describe her burnout: “Exhaustion does not cut it…there is not a word that exists in the English language at least that says the level of exhaustion that people are feeling right now through at least four levels of leadership at my institution.” Amy’s search for a word to describe how she and other leaders at her institution were feeling demonstrates the challenge in finding a word to describe the newfound level of burnout and exhaustion because it feels both qualitatively different and quantitatively more than levels experienced in the past.

The women specifically talked about how COVID exacerbated their feelings of burnout due to the chronic stress and uncertainty presented in both of their professional and family roles. Liz shared that she thought she has always had feelings of burnout throughout her career and admitted that “most working mothers I know have those,” but she did not have the same bandwidth to deal with her current feelings of burnout. “That bandwidth just keeps shrinking…I just am really struggling to figure out how to get back to that baseline.” Liz, among other participants, described her burnout as less physical and more mental exhaustion, “The mental exhaustion…the mental workload went up so much right? You know, I normally organized for a family of four everything and along with my job, that’s pretty much organizing all the pieces and then with COVID, it just exploded.” The World Health Organization’s (World Health Organization, 2019) definition of burnout described the syndrome as due to “chronic workspace stress that has not been successfully managed,” and Liz demonstrated that she lacked the “bandwidth” to deal with her stress in ways she had done so before, resulting in her feelings of burnout and exhaustion.

In terms of self-care to manage the burnout and exhaustion, the participants believed that they were able to grant others grace and support others, but often did not have much to give either at home or to themselves. Tina described her experience managing her staff and their “emotions, expectations, and their angst about the pandemic” and “their questioning policies and their frustration with leadership and their, and their, and their…” She felt that she was always giving to her staff and helping them through the pandemic and the racial or political unrest that was occurring near or on campus. “I mean it was it was just giving a lot of yourself to your staff, to try to make sure that they were okay which sometimes took away from you being okay.” She went on to question who was supporting her; who was making sure she was okay? “It did not always come from the top, to make sure I was okay. I had to do that for myself.” Unfortunately, although Tina knew she had to care for herself because she was not feeling it from the top, many of these women described their self-care practices as being minimal during the pandemic which perpetuated the cycle of burnout and exhaustion many of these women experienced. This interesting paradox amplified their feelings of burnout because they were required to give more to their families and institutions, but many felt they did not receive support or understanding from leadership at the top. Additionally, this lack of self-care contributed to how the World Health Organization (2019) defined burnout because the participants have not been able to effectively manage their chronic stress from the COVID-19 pandemic among other layering factors such as social and political unrest and racial reckoning.

Amy described her “empty bank” after “putting everything [she] [has] on the table to help support students” as her role was primarily student-facing as the senior student affairs officer for the institution. She shared this “empty bank” impacted her ability to mother, and she often asked her children and husband for decompression time to process her workday. Similarly, Jen realized that she gave “a lot of forgiveness and grace” to her staff and her colleagues but gave “none to [herself].” She was harder on herself as a leader due to the lack of support she felt from her supervisor above and the expectations she felt she had to maintain at work especially as a working mother attempting to balance work and family. Continually attending to people who have an increased need for support can contribute to feelings of energy depletion and exhaustion, causing an overall sense of burnout for the mother leaders.

The level of care and concern was certainly necessary in order to support their staff members during the pandemic, but simply because they were women or in leadership roles, they often were perceived as the caretakes of campus which placed a great deal of responsibility and pressure on them that almost seemed unattainable leading to feelings of burnout and exhaustion.

Never enough: Great responsibility generated feelings of guilt

The second recurrent theme, Never Enough, was exemplified in the experience of all nine participants. All participants expressed feelings of guilt, sentiments of never enough at home and work, and feelings of disappointment. These feelings of guilt and scarcity, coupled with the weight of motherhood where participants described their role of mother as their primary identity and as a “heavy,” “important,” and “loaded” word, led to burnout and exhaustion because these women placed great importance on their roles, especially as mothers, yet they did not meet expectations in ways they would like during the pandemic. The sentiments of never enough primarily came from the focus group where Carmen described never enough as pervasive: “nothing is ever, ever enough. It’s never enough for [my institution], it’s never enough for staff or faculty, it’s never enough for family. It’s just never…there’s never enough.”

The participants’ feelings of never enough were amplified due to the responsibility they felt in their motherhood role. Although mothering can look different for individuals, participants described their roles as mothers as “very important” and something they take “very seriously.” When asked how she defined motherhood in her individual interview, Shelly shared that it was a “loaded word” and that it “had a lot of weight to it.” Similarly, Tina described her title of mother as “the greatest title [she] has” as well as the “hardest job [she] has, but most rewarding.” Ashley shared that although she worked an “insane” number of hours, she recently discovered over the last few months that her primary identity is and always has been mother: “the person I am is motherhood and what I do is this job.” She admitted it was difficult for her to “disentangle what motherhood means” because it is so “pervasive that [she] sort of forgot that [she] was anything other than that.”

This great sense of responsibility to support their children was especially challenged during the pandemic and the social, racial, and political unrest especially experienced within the state where participants resided. Certainly prior to the pandemic the sense of responsibility to “raise good humans” was no small task either. This sense of responsibility and the participants’ inability to consistently meet their children’s needs in ways they previously had during the pandemic contributed to their feelings of never enough.

Even though feelings of never enough were exacerbated by the pandemic and other societal contextual factors, Jen stated in the focus group this feeling will likely persist her entire work life: “The guilt around not doing a good enough job at home and not doing a good enough job at my job still really has not gone away...probably never will.” This was after Jen returned to work on a hybrid basis and her children returned to school. She was able to slightly return to her compartmentalized life, but she still had this guilt of “never enough.” Jen described feeling this way even when she was forced to work from home during the governor’s stay-at-home order in the early stages of the pandemic where everyone had to work from home if they were able to:

If I’m at home, I feel constant guilt that I’m not at campus even though we were at a point where everybody had to go home. I still feel bad like I should be at work. I don’t like this feeling and this guilt that I’m not there [at work] and then I’d have guilt of not helping my kids enough, guilt of not being able to help people [at work] enough.

Often women feel guilty about being at home when they should be at work or being at work when they want to be with family due to the work–family conflict theory (Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985); however, Jen felt the guilt of not being at work even when she could not be physically at work due to the stay-at-home order placed by the governor. The guilt did not go away when the environmental context was no longer an issue.

Liz went deeper into her description of her feelings of never enough in her interview. She felt disappointed because she cannot be “all things to all people” and the pandemic primarily made her feel like she’s “not serving anybody well and that makes me feel uncomfortable and it makes me angry at myself.” She took these feelings a step further and stated that she felt as if she was failing her children, making “me feel inadequate…and feel angry that I could not give them more and feel sad that I’m not giving them my best.” At the same time, she also felt that she was doing the best she could and there “is not anything else for me to give. There is not another ounce of energy to do that.” Liz’s sentiments demonstrate the ways in which the Never Enough theme led to the Burnout and Exhaustion recurrent theme. In the workspace, she described that she felt she was doing “just good enough” and she would prefer to give more “brain space” to her work, but what she did give in all roles was all she could give at the moment. Similarly, Mary shared that she had not gotten back “into [her] groove” but particularly the uncertainty the pandemic presented made her feel like she “wasn’t doing anything well…nothing well.” Mary also shared that she typically led in a caring and nurturing fashion, but it seemed to be never enough for others: “there’s never that moment…I do not feel the moment where I can pause.” While Mary typically led in a caring and nurturing way, she felt it was necessary to increase the use of her caring approach during the pandemic, further contributing to these feelings of never enough.

Receiving support: Importance of gender, motherhood, and agency

Receiving Support: Importance of Gender, Motherhood, and Agency, describes the support women received at home and at work. The participants placed a great emphasis on the support from their supervisors being related to their supervisor’s gender and family role, particularly whether their supervisor was a mother. These characteristics of their supervisors were important when the participants described their experiences at work and their ability to be agentic with their own needs during the pandemic. Within this theme, participants who felt they could advocate for themselves often felt comfortable doing so because of their supportive leadership. The Receiving Support recurrent theme was present across seven of the nine participants, elevating it to recurrent status. Although there was divergence across whether the women had support at home or support at work, all women described support as an important factor in their experience of mothering and leading during the pandemic.

Many of the participants equated support with how they felt about their kids showing up on camera during meetings. Amy felt comfortable sharing her frustration about her child with her supervisor, which led to her supervisor even engaging with her child on occasion via Zoom. Amy’s supervisor even knew her children’s names, their interests, and could relate to her children. For example, Amy’s son wanted to talk to her supervisor and knew Amy had an upcoming meeting with her. Amy shared, “I’ll say to my supervisor, I know we have a ton to discuss, and [Peter] really wants to talk to you, and it just so happened that she happened to know the video game and the character [he was referencing].” Even beyond showing up haphazardly on camera, Amy felt comfortable inviting her son to speak with her supervisor during a meeting. Additionally, Liz also described her institution as being “supportive” and felt comfortable if “one of my kids had to come sit on my lap while I was on a call, that was welcomed and okay.”

On the other hand, Jen did not feel comfortable having her children appear on camera because she described her male supervisor as not supportive particularly as she battled attempting to balance her role as mother and leader during the pandemic. Jen shared as COVID continued on, “I was very careful never to mention my children and schooling at work because [my supervisor] did not have children at the time and I did not want him to think I could not do [my job].” Jen’s supervisor made negative comments about other employees’ children in the background which caused her to not talk about her children or feel comfortable having them visible on camera. She also wanted to “remain really professional” so she “did not ever really have [her] children around” therefore the reasoning was a combination of her desire to remain professional and also her lack of comfort based on her supervisor’s behavior.

Six participants out of the seven who supported the Receiving Support recurrent theme described gender and parenthood as an important factor in their sense of supportive leadership. Liz shared in the focus group how she felt comfortable with having her children appear on camera because of her all-female executive team:

We have an all-female executive team and I think that truly made a difference…I was the only administrator that had little kids at home. Most everyone else either had grown children or college-age students that might be at home and I felt really cared for and taken care of. So my kids always will pop on to say hello because they love the interaction and the feedback and the social aspect. So that's one thing I'm really grateful for, and I think our institution did really well to kind of normalize that we're human beings, and it was okay.

Similarly, Shelly shared in her interview “My boss is very understanding, and her kids are grown, but she was a working mom. And I think that’s been really helpful.” Amy also described her situation as “unique” in that her supervisor, the provost, and the president of her institution are both mothers. She explained, “the President is now a grandparent, so I think that I’ve actually said, like, ‘I think this has made you soft, being a grandparent has definitely made you a little softer.’ Yeah so they have been really understanding.” Altogether, Amy, Shelley, and Liz agreed in their conceptualization of support. They believed that support from the leadership above was demonstrated through understanding, caring, and relatability.

Emphasizing the importance of supervisors being not only women but also mothers, Carmen discussed her experience being one of the only members on the almost entirely female executive leadership team with children:

Although it’s almost an entirely female leadership team, I’m actually the only person, other than the President, that has children and it’s been a very odd experience to be with an entirely female leadership team, all of whom I assume for career reasons or other reasons, made choices, not to have children…In the beginning of the pandemic, I would bring up like we have a lot of working parents on the campus and we need to be flexible and do those things and there was a real lack of understanding of that to the point where I feel like I also have to hide my parenting and parenting stresses because I cannot be perceived as having to be that person or deal with those things, and so there’s some dissonance there around being on that leadership team and not being able to be entirely open about the challenges of parenting and open about the things that other people are experiencing on the campus.

Although she was on an almost entirely female leadership team, she did not feel comfortable sharing about her mother or parent identity because no one else on the leadership team could relate and they did not understand, according to Carmen. This quote from Carmen also aligned with her limited ability to advocate for other working parents on the campus with the executive leadership team because there was a perceived lack of understanding about the challenges working parents were experiencing simply because the leadership team members did not have children but were female.

This example demonstrates not only the importance of having the support of mother leaders above but also the support of parent leaders who had an understanding of what it might be like to be juggling all of the balls of work and home both in and out of a pandemic crisis. Certainly, this understanding and support from leaders above was required and more necessary during the COVID-19 pandemic as demonstrated by the support and caring leadership demonstrated by the participants to their staff members.

Discussion

This study examined the lived experience of nine mother executive administrators in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic. It provided important validation of existing literature around work–family conflict, blending, or integration but specifically within the context of COVID-19. Specifically in higher education, existing literature covers faculty as mothers (Wolf-Wendel and Ward, 2014; Sallee et al., 2016; Burrow et al., 2020), faculty as mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic (Beech et al., 2021; Fulweiler et al., 2021; Minello et al., 2021), and women in higher education leadership (Cook, 2014; Gallant, 2014; Hironimus-Wendt and Dedjoe, 2015; Burkinshaw and White, 2017), but very little literature presents the voices of mother leaders in academia to understand their lived experience with their dual roles and virtually no research has been conducted on the intersection of a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic, motherhood, and higher education leadership. As such, this study was critical to understanding specifically the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mother leaders in higher education when there are so few women in top leadership positions in academia (American Council of Education, 2017). Additionally, the experiences of the participants in this study provide an important reminder that their struggles are deeply rooted in capitalist and neoliberal feminism (Rottenberg, 2018), particularly intensive mothering culture (Hays, 1996) and the ideal worker norms (Williams, 2000; Blair-Loy, 2005).

Exposing the neo-liberal feminist ideal of “having it all”

As Craig and Churchill (2021) argued, crises have the ability to expose longstanding and systemic social problems, and this study demonstrated this is certainly the case with COVID-19, especially related to gendered cultural expectations and responsibilities related to the home and family. Women have been subscribing to the cultural expectation of the neoliberal feminist ideal of “having it all” (Rottenberg, 2018) for years and are often told to “lean in” in order to be successful (Sandberg, 2013). Neoliberal feminism has been recently framed with high-powered women publicly espousing feminism, recognizing gender inequality but failing to acknowledge the impact of socioeconomic and cultural structures on women’s lives (Rottenberg, 2018). Neoliberal feminism focuses on the individualistic qualities of most often middle- and upper-class women, encouraging them to focus on themselves and their aspirations (Rottenberg, 2018). Interestingly, Rottenberg (2018) suggested that in light of recent political shifts, neoliberal feminism reifies privilege, both of race and class, and heteronormativity, which also lends itself to not only neoliberal agendas but also neo-conservative political agendas. Whereas traditional feminism challenged power, Rottenberg (2018) argued that neoliberal feminism does nothing of the sort because in public media, it is often women in positions of power that project neoliberal feminist ideals.

The White, middle-class, neo-liberal cultural expectation that women can “have it all” was placed under a microscope during the pandemic where women’s challenges were called to attention, although certainly, these challenges were not new to women’s experiences. No doubt, the participants in this study experienced the challenges of not only working, but leading a higher education institution, as well as mothering during a crisis experience. During the early stages of the pandemic, Senator Tammy Duckworth contributed to Time magazine and stated, “American moms are running on empty. Every morning, we wake up feeling guilty that we are not doing enough. Every night, we go to sleep terrified that we are failing” (Duckworth, 2020, para. 1–3). Duckworth (2020) summarized almost perfectly the experience of the participants in my study and called to attention the need for a cultural shift in the way society expects working mothers to exist and be in the world in light of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The impossible notion of “having it all” for working women is related to the intensive mothering culture that is present in our society. The findings of this study align with Collins’ (2021) research on maternal guilt, which demonstrated that intensive mothering culture translates to increased guilt for mothers. Intensive mothering is an ideology that came about more than 65 years ago to describe the common motherhood expectations including being the primary and preferred caregiver, as well as an expert in child development (Hays, 1996).

Collins’ (2021) research demonstrates the cross-national nature of maternal guilt and supports the notion that policies are necessary but can also be insufficient in mitigating guilt, especially when taking cultural expectations into consideration. In the United States, the intensive mothering culture further exacerbated feelings of guilt for my participants because they were trying to “have it all” with their cultural subscription to intensive mothering. Not only were my participants trying to “have it all” as they were pre-pandemic, but they were trying to “have it all” in one single place, home, where both income-producing work and non-income producing work occurred for a period of time for eight of the nine individuals. To demonstrate the pervasive nature of the intensive mothering norms, Mary, who did not work from home much during the pandemic due to the requirements of her job, still felt the guilt and pressure placed on her by cultural norms and expectations leading to feelings of guilt and eventually burnout. Related to Whiley et al. (2021), when my participants attempted to reconcile the competing demands of what constitutes a “good” mother or a “good” leader pre-pandemic, they struggled and felt guilty. When the pandemic was layered on to this reconciliation, they felt increased pressure and guilt at not fulfilling either role to their expectations or the perceived expectations of others and society.

My participants were striving to be the proverbial ideal worker, and in particular the ideal leader, during the pandemic where the expectation is for employees to be completely devoted to their jobs and available to work long hours (Williams, 2000; Blair-Loy, 2005), as well as be effective leaders during a crisis as Lockwood (2005) described with aptitudes and abilities to include empathy, self-awareness, persuasion, teamwork, and relationship management. In addition to the increased focus on their leadership role during a crisis, these women also felt pressure to also practice intensive mothering (Hays, 1996) by the sheer nature of the pandemic during stay-at-home orders. Although it varied whether the participants in this study would call themselves primary caregivers, five out of the nine participants described their experience as being responsible for a large portion of the non-income producing work. This is especially interesting because one participant’s partner was laid off during this time. Even the women who did not admit to doing the majority of non-income producing work shared they felt pressured to do more around the house because of their mother role, informed by intensive motherhood notions (Hays, 1996). These pressures from the intensive motherhood culture “expend the precious resource of time, but also may create feelings of responsibility, generate additional cognitive load” (Milkie et al., 2021, p. 171) and contribute to women’s thoughts of what they should be doing with their time (Milkie et al., 2021). Furthermore, Milkie et al. (2021) argued that for women, engaging in an equivalent hour of domestic work compared to their male partner may be “denser” (p. 171) with the increased cognitive load women often carry and the cultural expectations that are “inextricably part of the work” (p. 171).

My participants described their mothering approach as survival or triage parenting, further contributing to feelings of guilt around not living up to the standards of intensive mothering culture. For example, my participants often found themselves practicing what they considered to be less than ideal parenting approaches such as parenting via electronic devices in order to give themselves some reprieve or to allow them to sit on a Zoom meeting for their income-producing work. Liz described her survival mode of parenting when she had to utilize technology to almost serve as another “parent,” especially as a single mother for a period of time during the pandemic. Another participant, Ashley, shared that she was unhappy about enabling her teenage son and doing tasks that he could or should do himself such as getting food. Certainly, parenting by electronics or enabling children does not fall in line with the intensive mothering ideal and relates more to the triage parenting approach described in Cummins and Brannon’s (2022) study. Even if my participants recognized and acknowledged the gender norms within their family responsibilities and roles, they still were heavily influenced by these hegemonic mothering ideologies and often felt as if they could not live up to these ideals, especially during the pandemic. Often when mothers experience conflict between the ideal and reality, they either reframe their decision to work so it conforms to these ideals (Blair-Loy, 2005) or they reject or challenge these ideologies and create their own (Christopher, 2012). The participants in my study acknowledged the cultural norms and expectations placed on mothers and described ways in which they were attempting to reframe or challenge these ideologies within their family units.

Lastly, the participants in Cummins and Brannon’s (2022) study described the importance of their careers to their identities and perceptions of good parenting. This increased importance of career challenged the ideology of intensive motherhood: “the mothers see their mothering as tied directly to their lives outside of their children” (p. 10). Similarly, the participants in my study challenge the intensive motherhood ideals and began to present ideals of integrative mothering. For example, as one participant shared, “work and home are laboratories for each other” to describe how she would “test” various approaches to problems either at home or work to see if they could be useful in the other environment. Relatedly, participants did not often speak about the tensions or the conflict between both income-producing and non-income producing work, but rather discussed the experience using the term integrated. Certainly, the two were often physically and mentally located in the same environment, home, but participants lost the ability to compartmentalize their income-producing and non-income producing work which consequently caused them to view the two types of work as integrated and co-occurring rather than separate. This mindset shift enhanced by the pandemic gives rise to potentially long-term challenges to intensive motherhood culture. Either way, conflict and tension may still contribute to feelings of guilt due to the pervasive cultural norms related to intensive motherhood (Hays, 1996), ideal worker norms (Williams, 2000; Blair-Loy, 2005), and overall neoliberal feminism (Rottenberg, 2018).

If working mothers are able to effectively integrate income-producing work and non-income producing work through the idea that they are combined and inform each other, there is a chance that feelings of guilt around work–family conflict or tension may be reduced. Work–family conflict was defined by Greenhaus and Beutell (1985) as inter-role conflict where the roles are separate and integrated mothering really examines the roles as intra-roles where the role is singular regardless of whether it is income-producing or non-income producing work. Recent research by Erdogan et al. (2019) examined how role salience and gender are related to work–family conflict, once again viewing income-producing and non-income producing work separately. These roles, once again, should be examined as intra-role versus inter-role conflict because the conflict exists inside of the person, not outside (Grünberg and Matei, 2020).

Burnout and exhaustion

Certainly, my study relates to Misra et al.’ (2021) study in that White women faculty were already feeling workload inequity without the pandemic taken into context. My study provided that once the pandemic was added into the mix, the mother executive leaders felt workload inequity even more so. This demonstrates that although this was a small sample size, the findings are not dissimilar from larger studies around the gendered workload in higher education and even more broadly.

While White women perceive inequitable workloads in higher education, current research has not examined whether there is a variance of burnout experience across the gender continuum. Studies have demonstrated that women often take on more of the emotional labor responsibility specifically at home (Pinho and Gaunt, 2021) and work, especially during a crisis (Vroman and Danko, 2020) which can eventually lead to burnout (Hochschild, 1983). Specifically, in higher education, women do more of the care work in the workplace, as well, ensuring the institution is running smoothly (O’Meara et al., 2017). The participants in my study described their emotional burnout from trying to support both their families but also their staff members during this crisis time of the pandemic in addition to the deep racial reckoning that occurred near the residences of several participants after the murder of George Floyd.

While burnout is often referred to specifically related to income-producing work (World Health Organization, 2019), researchers examined the impact of the pandemic on parental burnout (Bastiaansen et al., 2021). Parental burnout is defined as a “state of intense exhaustion related to one’s parental role, in which one becomes emotionally detached from one’s children and doubtful of one’s capacity to be a good parent” (Mikolajczak et al., 2019, p. 3). Furthermore, intensive mothering norms contribute to higher levels of parental burnout (Meeussen and Van Laar, 2018).

The pandemic placed increased pressure on parents further contributing to parental burnout through unemployment, low levels of support from family and friends, and a lack of leisure time which could have contributed to lower self-care practices (Griffith, 2020). My participants experienced parental burnout based on their chronic imbalance of demands over resources and their doubt around their capacity to be a good parent (Mikolajczak et al., 2019). While the participants did not describe emotional detachment from children, they felt as if they were not giving enough to their children. In some cases, participants felt they were neglecting their children’s needs, which may have contributed to a sense of emotional detachment.

Bridge of support

The nine participants in my study all felt burned out and exhausted during the COVID-19 pandemic even more so than they had felt prior to the pandemic. The findings from this study indicate that the pandemic exacerbated many challenges these women faced before the pandemic started and once the pandemic hit, many of these challenges were like balloons getting bigger and bigger until they could not get any bigger. This level of burnout and exhaustion had been unexperienced by the participants and therefore they did not know how to mitigate or manage the burnout. Additionally, in order to manage the chronic stress brought on by the pandemic, the women did not have self-care practices in place due to their inability to make time for intentional self-care as everything seemed like a priority or an emergency. Thus, women had to rely on others in order to help them mitigate their feelings of burnout and exhaustion for their own survival in both income-producing and non-income producing work. This reliance is represented by a bridge presented earlier in this chapter (Figure 1) the weight of the added complexities of the pandemic; racial, social, and political unrest; feelings of guilt; and overall burnout and exhaustion overwhelmingly consumed the participants where the bridge of support may not withstand these increasing challenges.

The necessity of support is not an unexpected finding as Dindoffer et al. (2011) shared the women in their study of mother leaders in protestant Christian higher education also made meaning of their experiences through strong family support, spousal support, mentoring, and their faith. Certainly, when you layer on the COVID-19 pandemic, the need for support is even increased but the support may be lacking due to various pandemic-related circumstances such as loss of community, loss of employment, and financial stress, among others. Their study demonstrated that 10 years before the pandemic, women were feeling challenged to meet the demands of family and work and relied heavily on support, especially spousal and family support in order to succeed. The women in the Dindoffer et al. (2011) study described the support from mentors as extremely critical in the way they made meaning of their experiences, which is similar to the way in which the participants in this study described the importance of having mother leaders above them to relate to their experiences during the pandemic and the challenges they had to navigate. Furthermore, an organization-level mitigation factor for work–family conflict is a family-supportive work environment (Kossek et al., 2011), and having a top leader who is a mother may influence the culture to be family-supportive.

Another key result of having female supervisors and mother leaders above them was that the participants felt they had a safer space to be agentic which helped them to create boundaries contributing to their overall wellbeing to mitigate their feelings of burnout and exhaustion. This sense of agency is aligned with the work of Grünberg and Matei (2020) who suggest the terms work–family conflict and work-life balance be replaced with a more agentic focused phrase. A sense of agency gave these women the ability to set boundaries with their supervisors hoping that these boundaries would mitigate the role conflict they experienced with the increased importance of both roles during the pandemic. Knowing women often feel a lack of agency to make decisions regarding the proverbial balance between work and family (O’Meara and Campbell, 2011), the gender and family role of the supervisor plays a critical role in fostering a culture that supports women’s agency.

Implications for practice

This study explained primarily the experience within the pandemic but also compared that experience to the participants’ experience before the pandemic. My findings reinforce the struggle of women that is deeply anchored in capitalist and neoliberal feminism (Rottenberg, 2018): intensive mothering (Hays, 1996) and the ideal worker (Williams, 2000; Blair-Loy, 2005) cultures. This struggle in essence creates increased work–family conflict and as a strategy, instead of being able to find balance, women attempted (and were also somewhat forced based on the stay-at-home order) to integrate these areas of their lives. Knowing that work–family conflict is one of the greatest social indicators of mental health (Amstad et al., 2011; Allen, 2013), institutions need to create a culture that decreases work–family conflict and releases the gendered expectations through policy changes and practice changes. Having a family-supportive working environment reduces the overall work–family conflict, especially for women (Kossek et al., 2011).

There seems to be a pipeline problem for women in higher education leadership (American Council of Education, 2017) as the number decreases each step of the proverbial ladder. Importantly, if women in executive leadership roles feel supported by having women or mother supervisors, institutions need to reevaluate their policies and practices to mitigate the pipeline challenge if they seemingly have such a challenge. Additionally, it is evident that not all mother executive administrators in higher education are going to be able to have women or mother leaders, therefore it is important for institutions to also create formal and informal support networks for all employees, but specifically for women and mothers.

Knowing how the participants in this study relied on both formal and informal support networks for their own survival and reconciliation of parental and work burnout, higher education institutions should create opportunities for women to formalize support networks through employee resource groups, facilitated discussions, and special interest groups among others. While informal support networks are often serendipitous, it is my opinion that employers can still facilitate the development of informal networks through building a culture of collaboration and connection. If employees feel supported in developing both a formal and informal network at work, they may be more likely to participate in these activities, further benefiting both them and the workplace. Overall, the building of informal and formal support networks at the workplace is another important step to perhaps shifting the work–family conflict conundrum that often is a challenge for women in particular based on our capitalist and neoliberal feminist ideals.

Although balance is often unattainable between work and life for women, work-life integration may be a better word choice to demonstrate the way in which these two environments intersect and interact with one another at any given point. However, this integration needs to be intentional because when this integration occurred almost immediately during the pandemic, the women did not know how to manage this integration and the blurred lines between work and home. Knowingly, institutions have recently begun to implement strategies to reconcile work and family for employees such as flexible work arrangements including hybrid work environments and paid family leave policies among others; however, this study along with Grünberg and Matei’s (2020) study, demonstrate that these policies do not always improve work–family conflict nor do employees utilize these policies.

Policies that are well-intentioned and seem to empower women also reinforce the context of traditional gender roles, “reiterating women’s social vulnerabilities instead of mitigating them” (Grünberg and Matei, 2020, p. 305). Certainly, work-family policies are most often thought of as benefiting women due to our social norms, but we need to change work expectations for everyone regardless of gender and family structure. It seems as if there is not a solution to this challenge because policies reinforce gendered roles for women (Grünberg and Matei, 2020) and are heavily based in capitalist and neoliberal feminist ideologies. Similarly, both men and women often do not take advantage of more parent-oriented policies (Sallee et al., 2016). The challenge of effective work-family policy does not seem to simply be a higher education problem, but a problem for women and mothers in the workforce more broadly. As such, this is more of a policy or systems challenge that needs to be addressed in order to create any tangible ideological shifts.

Moreover, in higher education, work-life integration literature states that in order to promote more usage of work-life policies, colleges and universities need to create an intentional culture of work-life balance which acknowledges the employees’ responsibilities outside of work (Lester, 2015). This intentional culture relates to the third recurrent theme around support from this study. The women in this study believed their supervisors were more supportive when they had a similar or relatable identity (e.g., motherhood or womanhood). This shared identity in turn created a culture of belonging and understanding for these women. Furthermore, knowing the dominant force of men in key leadership positions across higher education, it is important for them to be knowledgeable about the challenges of women in the workforce but also normalize the experience of a working parent if they have that particular identity. In order to foster greater work-life integration and a culture of belonging and understanding, Misra et al. (2021) suggest institutions provide a greater sense of transparency and clarity around faculty workload which may contribute to lower perceptions of inequitably assigned workloads. This approach may be applicable and even beneficial broadly in higher education but also to other workplaces. While women often feel as if they do more of the care work in the workplace (O’Meara et al., 2017), transparency and clarity may help women’s sense of burnout in the workplace. Overall, fairer and increased equitable practices and policies will have lasting effects on the goals of diversity and inclusion in higher education.

This study’s key finding across all participants was the overwhelming feeling of burnout and exhaustion. This may be a primary concern as higher education leaders prepare to plan for a post-pandemic future and prepare for future crises that are no doubt going to occur. Knowing burnout has the potential to decrease creativity and commitment (Moore, 2000), increase disengagement at work (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004), and increase turnover in roles at work (Jackson et al., 1986), institutions should implement a way to assess and evaluate employee’s, specifically women’s, burnout at work. With this assessment, institutions can make more informed policy and procedure decisions to improve burnout, although Grünberg and Matei (2020) suggest these types of “family-friendly” policies exacerbate traditional gender roles and vulnerabilities. Perhaps it depends on the perspective: do policies inform culture or does culture inform policy? While I understand Grünberg and Matei’s (2020) consideration, I also believe that even though individuals may not take advantage of family-friendly policies, if they are not there, then people do not have the opportunity to reduce their burnout or mitigate work–family conflict. Clearly, culture needs to support these family-friendly policies, as well.

Future directions for research

While I suggested increased measures for policy changes to accommodate and mitigate work–family conflict, I also believe additional research is needed to further our understanding of work–family conflict and mitigation policies enacted by employers to determine if they are even an effective mitigating factor for work–family conflict. Taken one step further, an extension of Grünberg and Matei’s (2020) research could examine the gendered nature of work–family conflict within the context of a post-pandemic world to understand if any ideologies shifted or changed as a result of the pandemic.

This study explored the experience of mother leaders during the COVID-19 pandemic but it is important to note the intersectionalities within these women’s experiences which was outside of the scope of this study. Certainly, three universal identities existed for the participants in this study: woman, mother, and higher education leader. Unfortunately, I was unable to capture the experience of racially diverse mother leaders during COVID-19; therefore I believe it is important to investigate racially diverse women’s experiences especially because only 5 % of college presidents are women of color (American Council of Education, 2017) and we know that the pandemic had a greater impact on gender disparities for women of color (Salles, 2021). Moreover, current research found that race and ethnicity matter more than gender when it comes to work–family conflict due to cultural values therefore gender and race/ethnicity must be considered together when examining work–family conflict (Ammons et al., 2017). As such, an extension of this study could be to specifically examine the intersectionality of gender and race for mother leaders in higher education during COVID-19. Additionally, although this study included two participants of same-sex partnerships, their experience was not notably different from the participants in heterosexual relationships. I believe the lived experience of same-sex parent partnerships during the pandemic should be examined as a collective to advance research on intersectionality and the experience of working parents, especially within the context of a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Furthermore, when examining work–family conflict and the impact it has on gender, researchers have not grappled with the fact that gender is not a binary construct and is a more fluid construct when researching work–family conflict. Studies have not fully examined how non-heteronormative family structure influences or is a factor in work–family conflict. As such, future research must be conducted to examine the various dynamics of a non-heteronormative family structure during the pandemic. Although we are not yet out of the pandemic, the research that currently exists primarily examines privileged working heterosexual couples (Calarco et al., 2021), the impact of the pandemic based on gender identity (Alon et al., 2020; Collins et al., 2020; Landivar et al., 2020; Petts et al., 2020), and the burnout effects produced by the pandemic (Aldossari and Chaudhry, 2020; Bastiaansen et al., 2021). Certainly, additional research could attend to the impact of parenting and working during the pandemic through the lens of non-heteronormative family structures or diverse gender identities on the gender continuum.

While the collective press and scholarly literature suggest that COVID-19 has negatively impacted women’s careers, it is important to investigate the comparative lived experience of father leaders to see how divergent the experience is from mother leaders. Particularly related to this study, researchers could examine the experience of father leaders in higher education or even single father leaders to compare experiences with the participants in this study and extend the current literature on the impact of COVID-19 for women (Alon et al., 2020; Collins et al., 2020; Landivar et al., 2020; Crotti et al., 2021).

Lastly, while this study laid the foundation for the examination of mother executive leaders in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic, a subsequent study could examine the experience of mother or women leaders in higher education who left the field of higher education during the pandemic as that was outside the scope of this study. Additionally, an examination of the variables under which the mother leaders’ experiences varied would expand the findings of this study. For example, did mother leaders at 2-year institutions have a particularly different experience than those at 4-year institutions? Did their experiences vary based on leadership role (e.g., student affairs or academic affairs)? This examination would provide an in-depth analysis of the influential variables that may play a role into the level of burnout or exhaustion and may take into greater consideration departmental norms and cultures rather than institutional norms and cultures.

Conclusion

At the time of the conclusion of this study, the question remains as to whether organizations are going to use this moment to enact changes or whether they are going back to what was considered “normal” in terms of workplace culture and practices even though “normal” was broken. Certainly, at the present time, it would seem as if back to normal work stances and expectations are happening across industries with few lessons learned to change the systems that were causing burnout, fatigue, and exhaustion for all employees, especially working mothers. I issue a call to action for higher education to take what was learned from the COVID-19 pandemic related to supporting its human capital by reexamining the work environment, policies, procedures, and expectations for all employees.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Nebraska Institutional Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LB contributed to the conception and design of the study, performed the analysis, wrote all drafts, and revised and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References