- Collaboratory on School and Child Health, Institute for Collaboration on Health, Intervention, and Policy, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, United States

This mixed-methods study investigated the learning and shifts in teaching practices that educators reported after participating in a trauma-informed schools professional development intervention. Training participants were 61 educators at a suburban U.S. elementary school. The year-long intervention included three after-school trainings, classroom coaching for a subset of teachers, and evaluation of school policies with administrators. Interview (n = 16) and survey (n = 22) data were collected. Quantitative results indicated that educators reported substantial shifts in their thinking and teaching practices. Almost half reported that their thinking shifted a lot and 55% reported that their practices shifted somewhat. Qualitative themes demonstrated increased understandings of trauma and secondary traumatic stress; increased empathy for students, families, colleagues, and compassion for self; enacting proactive strategies; reappraising interactions with students; increased collaboration with colleagues; and enacting self-care strategies as a result of participating in the professional development intervention. Results have implications for policy and practice, particularly the need for implementation and evaluation of trauma-informed approaches during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately half of U.S. youth had experienced at least one potentially traumatic event (Bethell et al., 2017). One in five had experienced two or more (Bethell et al., 2017). Students who experience trauma are at risk for reduced academic achievement, poor self-regulation skills, and difficulties creating and maintaining relationships (Perry et al., 1995). They may also experience challenges with attention, memory, and language (Hamoudi et al., 2015; Perfect et al., 2016). These effects are particularly likely if trauma is experienced at a young age or is chronic (Perry et al., 1995). As early as first grade, potentially traumatic events are associated with students’ later risk for high school dropout (Alexander et al., 2001).

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated rates of trauma exposure. For example, more than 150,000 U.S. children have lost a parent during the COVID-19 pandemic (Unwin et al., 2022). For children, the death of a parent is associated with elevated risk for traumatic grief, depression, and poor educational outcomes (Bergman et al., 2017). The COVID-19 pandemic has also been associated with elevated household substance use (Czeisler et al., 2020), concerns of increased child abuse and neglect (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2020; Swedo et al., 2020), and intensified educational and economic inequality (Fortuna et al., 2020), all of which have the potential to cause trauma for students. Research has found that many children (Patrick et al., 2020; Racine et al., 2021) and educators (Baker et al., 2021; Chan et al., 2021) have experienced increased stress and distress during the pandemic.

Increased incidences of trauma associated with the pandemic make trauma-informed teaching practices ever more important (Halladay Goldman et al., 2020; Sparks, 2020). However, educators report feeling insufficiently prepared to understand the effects of trauma or implement trauma-informed practices in their classrooms (Hobbs et al., 2019; National Council of State Education Associations, 2019; Koslouski and Stark, 2021). Further, their misunderstandings of students’ trauma-related behavior (Siegfried et al., 2016; Milner et al., 2019) may lead to punitive responses that compound students’ experiences of stress and trauma (Harper and Temkin, 2019; Milner et al., 2019). Although some programmatic approaches to train educators on the effects of trauma in schools have been developed, more research is needed to understand if and how these approaches shift educators’ practices (Stratford et al., 2020; Sonsteng-Person and Loomis, 2021). As school communities work to heal, teach, and learn during and following the pandemic, understanding if and how trauma-informed schools professional development (PD) supports educators and students is crucial. Therefore, the present study documents the reported learning and shifts in teaching practices of educators at one elementary school who engaged in a trauma-informed schools PD intervention.

Current approaches to trauma-informed schools professional development

Over the past 10–15 years, there has been strong and growing interest in creating trauma-informed schools (Overstreet and Chafouleas, 2016), including state legislation supporting the creation of trauma-informed schools in at least eight states (Harper and Temkin, 2019). Drawing from Harris and Fallot’s (2001) original conception of trauma-informed care and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] (2014) guidance for a trauma-informed approach, trauma-informed schools “create educational environments that are responsive to the needs of trauma-exposed youth through the implementation of effective practices and system-change strategies” (Overstreet and Chafouleas, 2016, p. 1). Importantly, a trauma-informed approach is not a standalone intervention that treats the trauma symptoms of individuals; instead, it is a framework that guides systems (Maynard et al., 2019). Hanson and Lang (2016) describe that trauma-informed approaches may include (a) PD, (b) practice changes, and (c) organizational changes, and should include at least two of these three areas.

The first published approach to creating a trauma-informed school was developed by Cole and colleagues in 2005; since then, several additional approaches have been developed (Koslouski and Stark, 2021). Though varying in their scope and attention to equity (Gherardi et al., 2020; Koslouski and Stark, 2021), these approaches commonly aim to promote educator understanding of trauma and stress, safe and predictable learning environments, consistent and caring relationships, social and emotional learning, cultural humility, and empowerment and collaboration (Dorado et al., 2016). As described by Chafouleas et al. (2016), PD is an important foundational component to developing trauma-informed schools because it can help to establish knowledge and attitudes needed to become trauma informed. To date, there is no standardized trauma-informed PD for educational settings (Thomas et al., 2019).

Across existing trauma-informed school approaches, PD generally begins with didactic staff trainings. Some approaches also include classroom coaching or work with school administrators to evaluate and revise school policies to be trauma informed. Didactic staff trainings most commonly focus on foundational understandings of trauma and secondary traumatic stress (Chafouleas et al., 2016). Foundational trauma trainings describe the prevalence and impacts of trauma and the relations between trauma, triggers, and student behavior (Wittich et al., 2020). Staff are trained in instructional and non-instructional strategies that benefit students who have experienced trauma, including building consistent and caring relationships, teaching multi-sensory lessons, and establishing predictable classroom routines (Cole et al., 2005, 2013). Trauma-informed school approaches recognize that all students benefit from these practices; however, they are particularly important for the success of students who have experienced trauma (Craig, 2016). When possible, PD is implemented staff-wide to promote common language and understandings across the range of school personnel who work with students (Chafouleas et al., 2016).

It is recommended that trauma-informed school approaches utilize the multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS; Sugai and Horner, 2009) model, providing varied levels (Tier 1, 2, and 3) of student support depending on demonstrated needs (Chafouleas et al., 2016). Tier 1 interventions focus on school-wide supports (e.g., available to all students as part of general education programming), while Tier 2 and Tier 3 supports become progressively more targeted for students needing additional supports. Implementing multi-tiered systems of trauma-informed support generally occurs over multiple years and is often done using a phased approach (Fixsen et al., 2005; Chafouleas et al., 2016).

Building educators’ capacities to effectively respond to trauma

Trauma-informed schools PD aims to encourage curiosity over judgment about student behavior (Bloom, 1994). This is done by building educators’ social and emotional competencies with which to recognize, interpret, and respond to student trauma responses. For example, if an educator understands how a student’s self-regulation challenges are influenced by experiences of trauma, they may be better equipped to respond with empathy and support rather than discipline or punishment. This work is supported by the prosocial classroom model (Jennings and Greenberg, 2009). Jennings and Greenberg explain that educators’ social and emotional competence influences how they build relationships and respond to students’ emotions and behaviors. The authors stress that social and emotional competence can and should be taught to educators because it is paramount to educator and student success and wellbeing. Educators with strong social and emotional competence are perceptive to others’ emotions, understand potential underlying explanations for these emotions, and recognize how emotions inform behavior (Jennings and Greenberg, 2009). They are self-aware and adept at managing their own emotions. With these skills of attunement to students and themselves, educators are better equipped to support students’ academic, social, and emotional growth (Jennings and Greenberg, 2009). Trauma-informed schools PD is one example of PD that aims to strengthen educators’ social and emotional competence by training them to understand and effectively respond to consequences of trauma in the school setting.

Existing research on trauma-informed professional development interventions

Three recent systematic reviews provide key insight on existing evidence related to the outcomes of trauma-informed PD interventions. First, looking across disciplines, Purtle (2020) conducted a systematic review of evaluations of trauma-informed organizational interventions that included staff trainings. The author identified 23 studies, with the majority being in medical settings or child welfare agencies, and only one in a school setting. The review found that, across studies, there was evidence of improved staff knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors related to trauma-informed practice after participating in trauma-informed training, particularly when the intervention included additional components (e.g., ongoing consultation, policy work). However, the author noted that it was less clear how changes in staff knowledge and attitudes were translated into practices.

Next, Roseby and Gascoigne (2021) conducted a systematic review of school-wide trauma-informed education programs and their impact on students’ academic-related outcomes. The authors identified 15 articles describing school-wide trauma-informed education programs in preschool (n = 3), elementary (n = 5), and high school settings (n = 7). Eleven of these programs included staff PD. The authors found encouraging but mixed results related to students’ academic-related outcomes. They concluded that programs with multiple components, intensive initial staff training, regular booster sessions for staff, and those that were implemented over longer periods of time demonstrated greater impacts on students’ academic-related outcomes.

Finally, perhaps acknowledging the need for multicomponent interventions, Avery et al. (2021) limited their systematic review to school-wide trauma-informed interventions that included at least two of the following three elements: (1) staff PD on the impact of trauma, (2) practice change (e.g., prevention and/or intervention work), and (3) organizational change (e.g., revising policies or procedures to be trauma informed). The authors were only able to identify four school-based studies that met these criteria. The studies each focused on student outcomes (e.g., behavioral change, trauma symptoms), but did also report increased staff knowledge of trauma. The authors identified an urgent need to determine how various elements of a trauma-informed school approach contribute to student and staff outcomes. As resources are often stretched in schools, this would aid schools in selecting the most efficient and effective interventions.

These three reviews identify important next steps in the investigation of trauma-informed schools PD. First, additional research on various outcomes of trauma-informed schools PD is needed. In these recent reviews, only a small number of studies on trauma-informed schools PD were identified. Roseby and Gascoigne (2021) identified the most studies, but these spanned preschool, elementary, and high school settings. It is likely that unique considerations at each level (e.g., high school teachers having a larger number of students who rotate classes) affect how trauma-informed PD is put into practice, necessitating an accumulation of evidence at each level. In addition, across these reviews, the majority of studies focused on student outcomes. Much more information is needed on educator outcomes, including identifying how educators’ understandings of the impacts of trauma influence their teaching practices (Sonsteng-Person and Loomis, 2021). As summarized by Stratford et al. (2020), “There are many school districts around the country that are spending professional development resources on training teachers about trauma with little evidence to demonstrate whether those trainings actually translate into changed behaviors in the classroom and improved outcomes for students” (p. 472). Additional research would assist schools and policy makers in making decisions about the funding and implementation of trauma-informed schools PD approaches.

There is also a need to accumulate evidence about the elements, duration, and intensity of trauma-informed schools PD approaches to determine what is needed to facilitate change in teaching practices (e.g., evidence suggests that one-time trainings are generally ineffective in shifting educators’ practices; Desimone and Garet, 2015). As evidenced across the three systematic reviews, there is growing evidence that multifaceted interventions are more successful in producing desired outcomes. To this end, Overstreet and Chafouleas (2016) encourage that research on trauma-informed school approaches be grounded in logic models or theories of change so that comparisons can be made across approaches. As such, the present study aimed to investigate the learning and shifts in teaching practices reported by educators participating in a multifaceted trauma-informed schools PD intervention at one elementary school. The included logic model demonstrates alignment to prior trauma-informed school PD approaches and allows for comparison across approaches.

The present study

This study seeks to provide evidence of the learning and shifts in practices that educators report after participating in a multifaceted trauma-informed schools PD intervention. The research question of the study was “What learning and shifts in teaching practices do educators report after participating in a year-long Tier 1 trauma-informed schools PD intervention?” The intervention included three after-school PD sessions, classroom coaching for a subset of teachers, and meetings with school administrators to evaluate and revise school policies. Results provide a nuanced picture of the outcomes that can be expected from educator participation in trauma-informed schools PD. These results may help to inform administrators and policy makers’ decisions about whether to invest in trauma-informed schools PD and may allow researchers to investigate a more specific set of potential outcomes that can be expected from educator participation in these approaches.

Materials and methods

School context

The intervention was implemented at a Northeast elementary school during the 2019–2020 school year. The school served approximately 400 students in grades pre-kindergarten–4 (approximately 3–11 years old). The majority of students were White (80%); 15% were Latino and the remaining 5% were Asian, Black, or multiracial. One-fourth of students had a first language other than English and 30% qualified for free or reduced-price lunch. Most staff were White (98.5%) and female (95.5%).

Description of the intervention

A year-long Tier 1 trauma-informed schools PD intervention entitled “Understanding our Students, Understanding Ourselves: Navigating Trauma in Our Schools” included (1) three after-school PD sessions for teachers, paraprofessionals, and administrators (85% of school staff: n = 61), (2) bi-weekly coaching sessions for a subset of teachers (n = 3), and (3) monthly meetings with administrators to evaluate school policies and procedures. The study’s author designed the intervention to assess its feasibility and effectiveness. Data collection and coaching sessions began in October 2019. In-person after-school PD sessions were delivered in December 2019, January 2020, and February 2020.

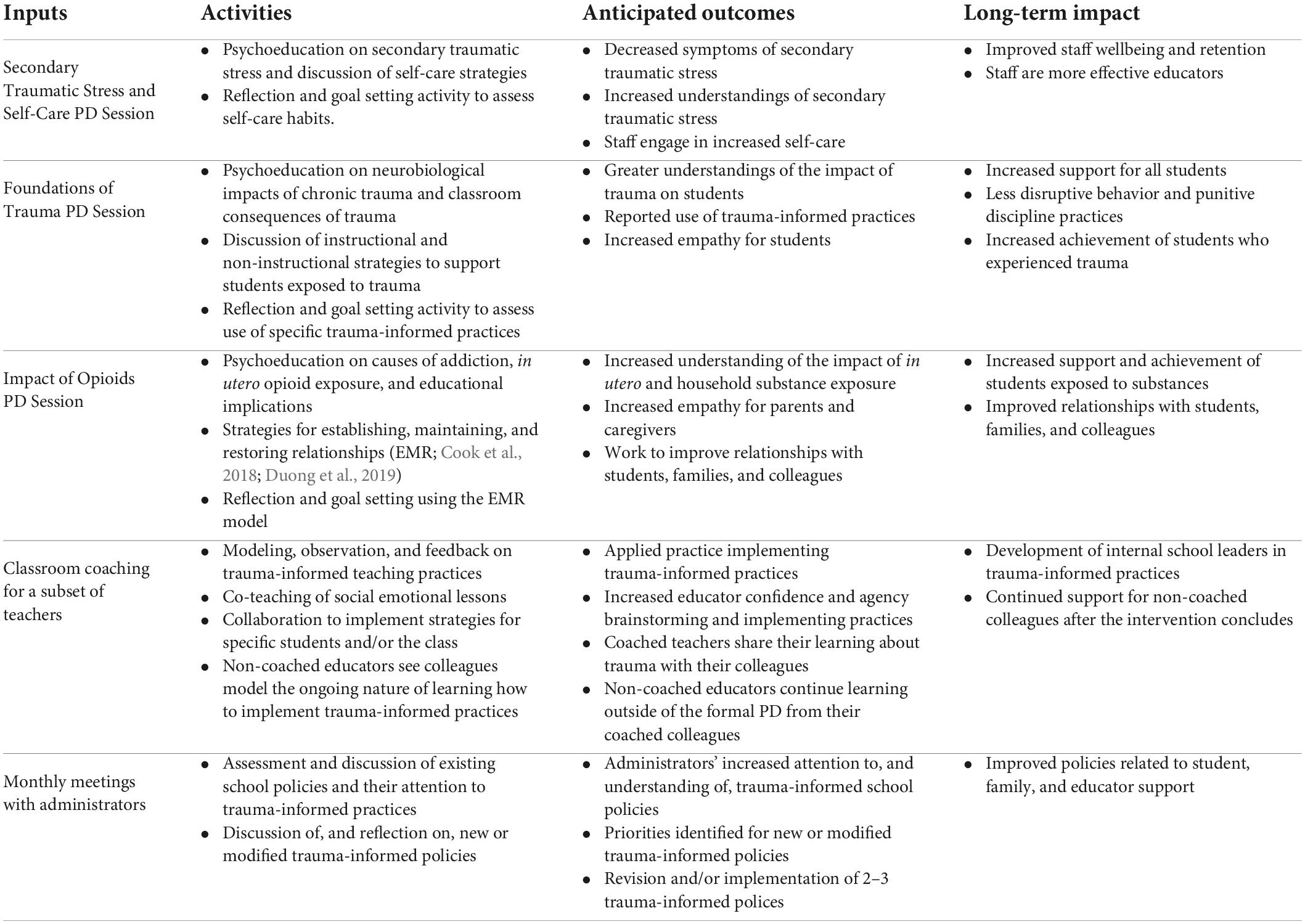

The three 45-minute PD sessions were delivered during contractually paid staff meetings and focused sequentially on: (1) Secondary Traumatic Stress and Self-Care, (2) Foundations of Trauma, and (3) Educational Impacts of the Opioid Epidemic (see Table 1 for further descriptions of content). PD sessions on secondary traumatic stress and foundations of trauma were included for their alignment to other trauma-informed schools PD approaches. Training on the educational impacts of the opioid epidemic was included due to its relevance to the school community and educators’ requests for training on this topic. The after-school PD and coaching sessions were led by the study’s author.

Bi-weekly classroom coaching sessions with three classroom teachers (who also attended the after-school PD sessions) consisted of 45 minute of shared time in the classroom followed by a 30-minute debriefing session. Debriefing sessions were used to plan or reflect on lessons, brainstorm supports for students, and reinforce after-school PD content. All classroom teachers (n = 22) were invited to express their interest in classroom coaching. Based on the time and resources available for classroom coaching, three of the 10 interested classroom teachers were randomly selected.

Finally, to promote sustainability over time and through changes in staff and leadership, monthly meetings with school administrators were used to assess school policies for their alignment with key principles of trauma-informed schools. Safe Schools New Orleans (2022) Policy Checklist was used. This checklist includes six sections: Cultural Humility; Safety; Trustworthiness and Transparency; Collaboration and Mutuality; Empowerment, Voice and Choice; and Peer Support. It has 3–12 questions per section that can be used to evaluate the extent to which school policies align with each principle. Each month, the administrators and author reviewed one of the six sections and engaged in reflection, brainstorming, and goal setting related to strengths and opportunities in that area. After completing the six sections, the administrators elected to focus on policies and procedures related to Cultural Humility, Collaboration and Mutuality, and Peer Support. Additional details are described in Koslouski and Porche (2020). A logic model of the PD intervention is shown in Table 1.

In mid-March 2020, five months after the start of the intervention and after all of the after-school PD sessions were complete, the school temporarily closed due to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Coaching sessions were suspended; each teacher received 11–12 of 20 planned coaching sessions. Meetings with administrators continued remotely.

Institutional review board approval, consent process, and confidentiality

This study was approved by the Boston University Institutional review board (IRB). The study purpose and procedure were reviewed with participants prior to data collection. Staff could attend the after-school PD sessions without consenting to study participation. Data from consented participants were de-identified and stored securely.

Role as researcher

In this study, the author was both a researcher and PD facilitator. In an effort to reduce social desirability bias (Nederhof, 1985; Bergen and Labonté, 2020), in both the survey and interview protocol, the author explained that the research aimed to improve the intervention and that honest feedback was most helpful. The author also collected survey data, which did not ask for any identifying information, so that participants were able to provide anonymous feedback. This has been identified as a valuable way to reduce social desirability bias (Nederhof, 1985).

Data collection and participants

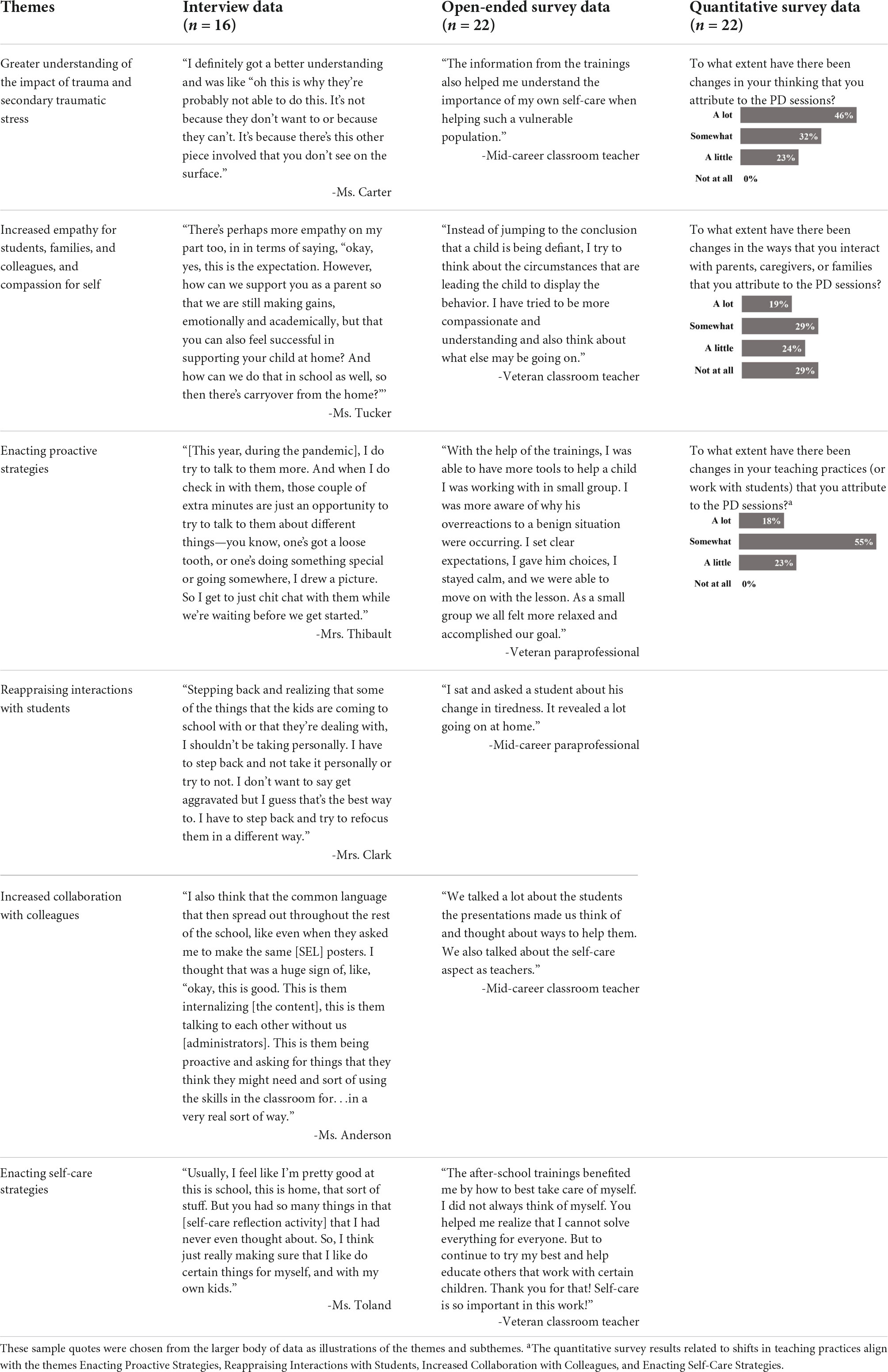

Data were collected using a convergent mixed methods design (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2017). The interviews and survey were conducted concurrently. Qualitative and quantitative analyses were completed separately and then merged to inform the conclusions of the study. Findings from both qualitative and quantitative data were organized in a joint display (presented below in Table 4; Guetterman et al., 2015) to examine the alignment or divergence of results. Results were then integrated for the presentation of results to illustrate the salience of themes across data sources and to provide rich qualitative description along with quantitative results.

Interviews

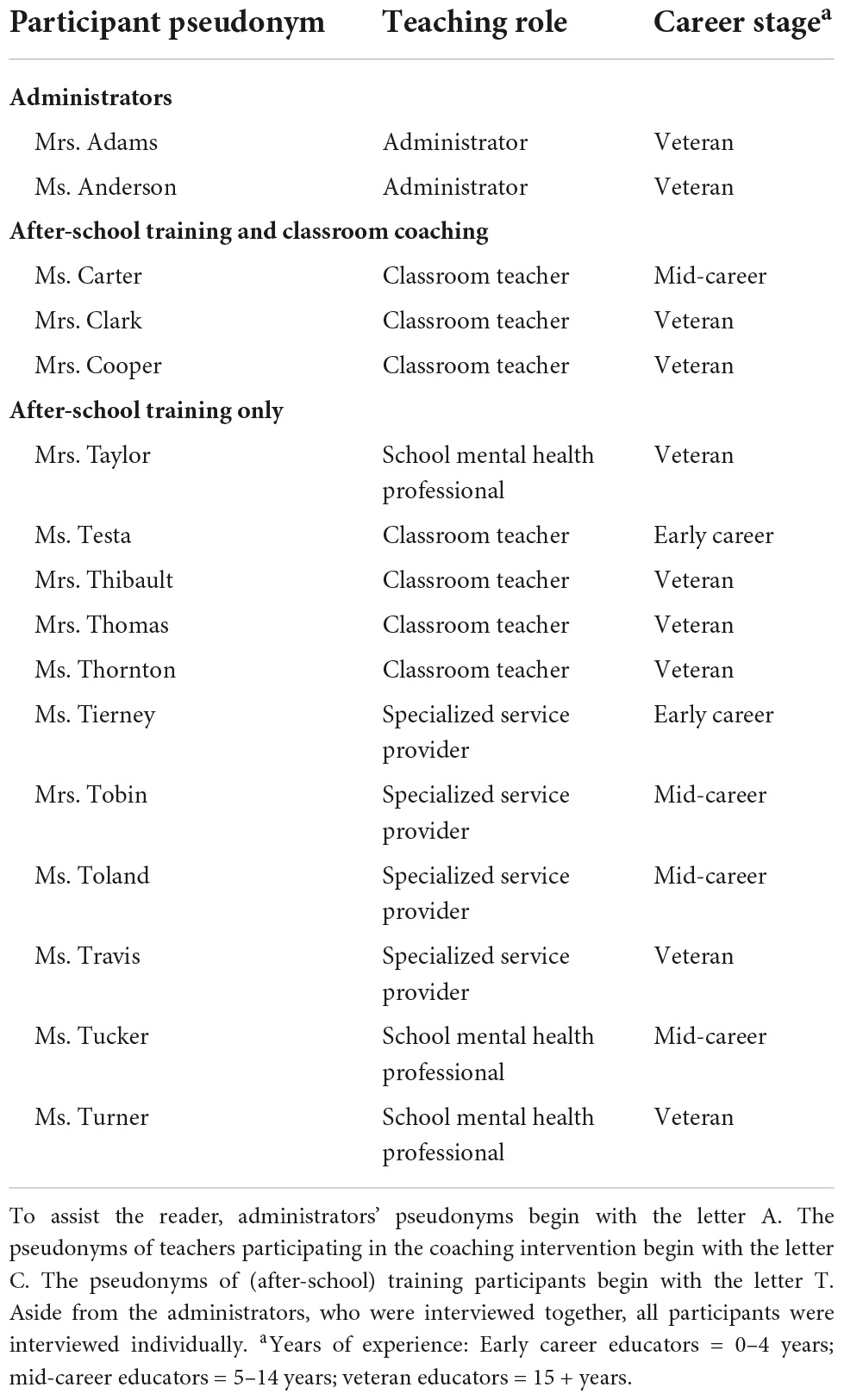

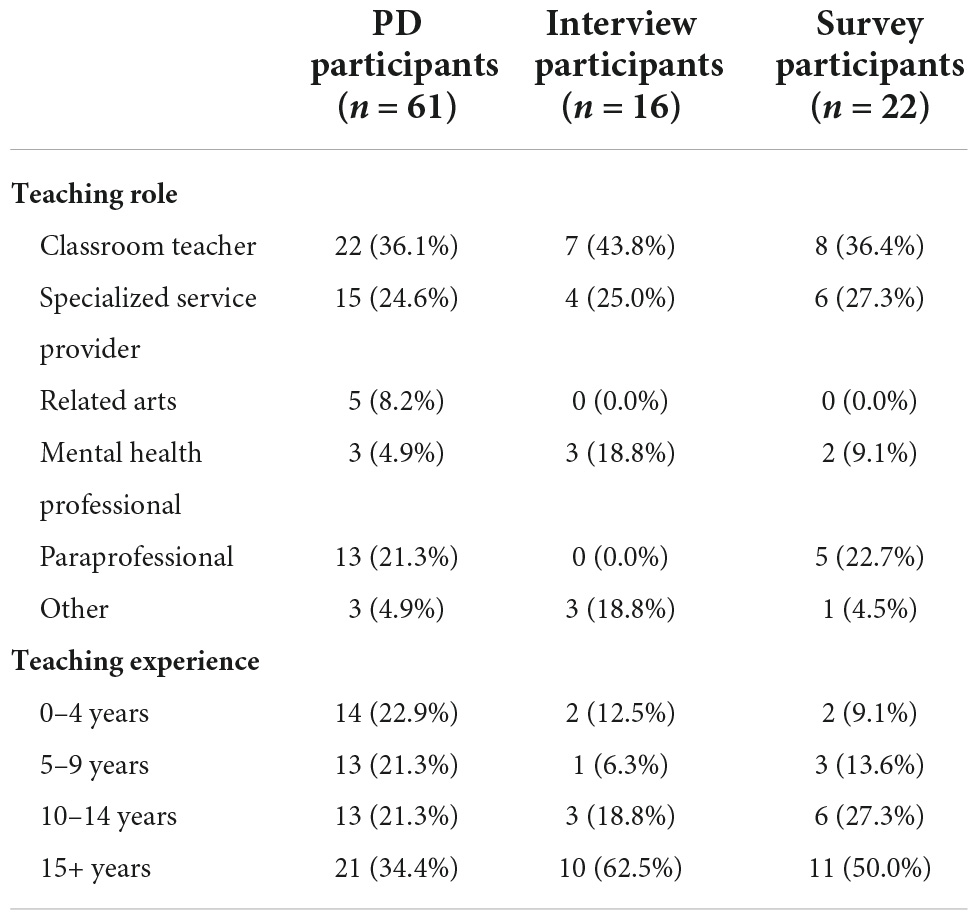

Interviews were conducted with a subset of PD participants (n = 16) between May and November 2020. PD participants were emailed a recruitment flyer inviting them to participate in a 20–30-min interview. The semi-structured interview protocol included 10 questions about participants’ experiences with the PD intervention. The present study focuses on 4 questions in which participants were asked if there had been any changes in their teaching practices, interactions with families, or understandings of trauma and secondary traumatic stress that they attributed to the PD sessions. If participants responded affirmatively, they were asked to provide specific examples. Participants were given a $50 gift card in appreciation for their time. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interview participants are described in Table 2.

Survey

In May 2020, the 61 PD participants were invited to participate in a brief survey about any learning or shifts in teaching practices that they attributed to the PD intervention. The survey was distributed by email, took 10 min to complete, and included three quantitative and three open-ended questions. Participants were asked to report the extent to which the PD sessions influenced their (1) thinking, (2) teaching practices, and (3) interactions with parents/caregivers. Response options were not at all, a little, somewhat, and a lot. The three open-ended questions asked participants to provide an example(s) of a time when they (1) thought differently about a situation, a student, or themselves based on the PD; (2) changed their teaching practices based on the PD; and (3) interacted differently with parents, caregivers, or families due to the PD. Participants were asked to provide their teaching role (classroom teacher; specialized service provider [e.g., special educator, reading specialist]; related arts [e.g., music]; paraprofessional; school mental health professional; other [e.g., nurse]); and years of experience (0–4 years, 5–9 years, 10–14 years, 15 + years). A $15 donation was made to the school’s local food pantry for each person who completed the survey. The survey response rate was 36.1% (n = 22). Demographics of the PD, interview, and survey participants are shown in Table 3.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze quantitative survey data with SPSS Version 26.0 (IBM Corporation, 2019). Qualitative coding was completed using NVivo 12 software (QSR International, 2018). Reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006, Braun and Clarke, 2021) was used to explore the learning and shifts in teaching practices that educators attributed to PD intervention. The qualitative interview and open-ended survey data were inductively coded line by line. Then, the codes were reviewed for redundancy and accurate naming and provisional thematic maps were created (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Thematic maps are used to explore relationships between codes. They are created and refined until a provisional thematic map acceptably represents the data and answers the research question. The author engaged in an iterative process of searching for themes by creating provisional maps and reviewing the data (Braun and Clarke, 2006). In total, nine provisional maps were created to explore the learning and shifts in teaching practices that educators reported as a result of the PD intervention. Once a provisional map that satisfactorily represented the coded data was created, all of the raw data was reread to be sure the map represented the data well and no major ideas had been omitted (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Finally, a code book was provided to a second coder to analyze 20% of the data. The two coders had 95% agreement in their coding and met to resolve any discrepancies.

Legitimizing the study results

Multiple measures were taken to legitimize the study results (Onwuegbuzie and Johnson, 2006). First, a diverse subset of the PD participants (n = 16; 26.2% of PD participants) who represented a variety of teaching roles and grade levels were interviewed. By collecting both interview and survey data, the codes and themes were able to be triangulated across participants, roles, and data sources (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2017). In the results, quotes from a variety of participants—demonstrated through varied teaching roles and years of experience—were included to illustrate the salience of themes across participants. Participants were asked to share stories and examples so that the study’s author could gain a deeper understanding of the shifts that they experienced rather than a simple endorsement of those shifts. Disconfirming evidence (i.e., findings contrary to other data; Creswell and Miller, 2000) was sought out and reported to provide a complete picture of the learning (or lack thereof) that educators reported. An audit trail of memos was maintained throughout the qualitative coding and analysis phases to document decisions, descriptions and shortcomings of each new thematic map, and rationale for each reorganization of the data. Lastly, a second coder independently analyzed 20% of the data. This allowed the author to verify the interpretations of the data and increase the trustworthiness of the findings.

Results

This study sought to identify the learning and shifts in teaching practices that educators reported at the end of Year 1 of a trauma-informed schools PD intervention. Six themes regarding the influence of the trauma-informed schools PD intervention emerged: educators reported increased understandings of the impact of trauma and secondary traumatic stress; increased empathy toward students, families, and colleagues, and compassion for self; enacting proactive strategies; reappraising interactions with students; increased collaboration with colleagues; and enacting self-care strategies. Table 4 demonstrates the salience of these themes across qualitative and quantitative data sources.

Across these findings, educators described changes that occurred before the COVID-19 pandemic and while remote or hybrid teaching during the pandemic. As the pandemic began within weeks of the third after-school PD session and was ongoing during post-intervention data collection, these findings are included. Although unexpected, the pandemic quickly became the teaching context in which educators had the opportunity to apply (or not apply) their learning.

In addition, across these themes, there were indications that the learning facilitated through the after-school PD sessions would not have been the same if classroom coaching for a subset of teachers had not occurred. The coaching sessions reinforced and extended learning for the three teachers involved, but also positioned them to be resources for their colleagues. The three teachers described processing the after-school PD content with their colleagues, sharing their coaching work with colleagues, and being used by their colleagues as resources in trauma-informed teaching practices. Mrs. Cooper described, “With the people that I work directly with, [a special educator], [a paraprofessional], and [another classroom teacher], we definitely had conversations based off of what we had learned from you and the PD. And then, the four of us would also talk about specific kids and the suggestions you had. It made it part of our discussions, our vocabulary, and trying out new things.” Mrs. Thomas, who was not in the coaching intervention, shared that Mrs. Cooper’s involvement helped her. She reflected, “Because I was able to get a lot of what you had taught her and she would share it with me. […] So, I’ve definitely been channeling some of that this year.” Ms. Carter described colleagues consulting with her based on her involvement in the coaching intervention. She shared, “My [colleagues] have come to me and asked for different strategies.” For example, one colleague had a student who had experienced significant household substance use. She asked Ms. Carter for suggestions and advice of how to support the student. In sum, these preliminary data suggest that the ongoing coaching sessions for a subset of teachers may have fostered internal resources that supported the outcomes described in the themes below.

Greater understanding of the impact of trauma and secondary traumatic stress

Participants conveyed that the PD intervention led to increased understandings of the impact of trauma on students and families. They expressed that their definitions of potentially traumatic events had broadened and that they had a greater understanding of how these experiences affected students and families. For example, Mrs. Clark expressed that she now realized that trauma could occur from many more experiences than abuse or neglect. Mrs. Cooper described that understanding the impact of trauma on students had “put things into a new light” for her. She described working with one student who has a significant history of trauma and a chronic medical condition. She explained, “It made me realize that all this trauma bubbled up […] you’ve got to get through that, especially with the [medical condition] and all that, getting through that first before he’s going to be ready to learn.”

Anonymous survey respondents1 echoed these sentiments. For example, a mid-career paraprofessional wrote, “I think I am just more aware of the impact that trauma has on the students and try to keep that in mind when interacting with them.” A mid-career classroom teacher shared, “I have a student who remembers things one day and then forgets the next. I now understand [that] because of his past traumas, this is how his brain works and the good news is it can be repaired or rewired with consistent practice.”

Educators also conveyed increased understandings of secondary traumatic stress and the importance of self-care. For example, Mrs. Clark described her evolving understanding of secondary traumatic stress and self-care. She shared, “Self-care doesn’t mean you’re going and getting a manicure and a pedicure. Self-care can mean you’re not looking at your email after 3:30, [you] leave the computer in another room, [you] don’t even look at it.” Ms. Tierney spoke about always taking care of others before herself and developing a greater understanding of the toll this took on her work and wellbeing. She shared that at the time of the Secondary Traumatic Stress and Self-Care Training, she was supporting a friend through a serious medical procedure. She recalled, “At the time, I also had students that demanded a lot of my attention, as they were undergoing their own trauma, and I felt pulled to care for everyone but myself. The reminders to breathe, take time, and ask for help were very helpful for me.” Similarly, on the anonymous survey, a mid-career classroom teacher shared, “The information from the trainings also helped me understand the importance of my own self-care when helping such a vulnerable population and gave me strategies to do so.” Participants conveyed that they had not previously understood the toll this work could take on them.

Increased empathy for students, families, and colleagues, and compassion for self

Educators reported feeling increased empathy for students and families as a result of the PD intervention. For example, Ms. Carter provided an example in which she described the compounding experiences of trauma that one of her students was experiencing. She explained,

Not only is he learning a new language, but now I have the consideration he also moved, left his family [in another country to live with an aunt he had never met]. We don’t know the home life. He doesn’t talk to [his parents]. He doesn’t see them. If he’s out of control, I’m like, “Okay, well maybe his school wasn’t like this before, maybe this is a whole different lifestyle.” And having that ability to kind of put myself in his shoes.

On the anonymous survey, a veteran specialized service provider wrote that the PD sessions led to her “finding love for kids with the most challenging behaviors—especially one boy who will do anything to derail the class.” Quantitative survey data supported these sentiments. The intervention encouraged empathetic interactions and almost half (45.5%) of respondents reported that the PD sessions impacted their thinking a lot, 31.8% somewhat, 22.7% a little, and 0.0% not at all.

Several anonymous survey participants also wrote about their increased empathy for caregivers as a result of the PD. Participants reported empathizing with caregiver stress and trauma in both their thinking and in their communication with caregivers, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. A veteran classroom teacher reported, “being aware that parents can be dealing with their own trauma and they are doing the best they can.” A mid-career classroom teacher reported ending every communication to caregivers with “Do what you can and what you can do is your best” in hopes that “parents don’t feel the pressure.” Quantitative survey data demonstrated that 19.0% of respondents reported that the PD sessions impacted their interactions with parents, caregivers, or families a lot, 28.6% somewhat, 23.8% a little, and 28.6% not at all. Three respondents explained their not at all responses. Two reported that as paraprofessionals, they did not interact with parents. One reported that empathetic family outreach had been part of their practice prior to the intervention.

A few participants spoke about feeling increased empathy for their colleagues. Mrs. Clark spoke about conversations she had with her grade level team about setting boundaries while remote teaching. She explained, “There were definitely nights when the [group] of us would be texting about plans for the next day […] and there were times people on my team just checked out because we had to.” Mrs. Clark said that her teammates offered one another compassion and understanding in those moments. Similarly, on the anonymous survey, a mid-career specialized service provider wrote, “I have found myself more patient and understanding with students and families as well as colleagues.” A veteran specialized service provider described that the PD sessions helped them to engage in “supporting colleagues who are dealing with traumatized students.”

Finally, participants expressed ways in which the PD sessions increased their feelings of compassion for themselves. For example, Mrs. Cooper reflected on a training activity in which educators identified student behaviors that triggered negative emotional responses in themselves while they were teaching. She shared, “I’ve been way more aware of that. So, just saying [to myself], ‘Oh, well, this is what triggers you.’ Knowing it kind of normalizes it. Like, ‘okay, that’s fine. You have to let that go.”’ On the anonymous survey, an early career specialized service provider summarized, “It comes back to recognizing that teachers have an important role in the community, but we cannot do it all alone and we cannot pour from an empty cup. Be empathetic to our families, but to ourselves too.” Across the data sources, participants conveyed that their increased understandings of trauma and secondary traumatic stress increased their empathy for students, families, and colleagues, as well as their compassion for self.

Enacting proactive strategies

The next four themes focus on shifts in teaching practices. On the quantitative survey, approximately 1 in 5 (18.2%) survey respondents reported that the PD sessions impacted their teaching practices a lot, 54.5% somewhat, 27.3% a little, and 0.0% not at all. This aligned with qualitative data, in which educators provided rich descriptions of shifts in their practices.

Educators reported enacting proactive strategies as a result of participating in the PD intervention. These included intentional grouping, offering choices, strengthening relationships, and embedding social and emotional learning into the day. For example, Ms. Tucker shared that the PD sessions led her to be more intentional in her interactions with students. She explained, “Really making sure that the student feels listened to and not just because you’re going through the wheels. Like, ‘I see that you’re upset, are you ready for me to talk to you? If not, that’s okay, I’ll wait, let me know.”’ Relatedly, on the anonymous survey, a veteran specialized service provider shared that they had been “Trying to dig deeper into understanding why a student is withdrawn, take pressure off, rather than put them on the spot. Trying to find an interest or spark through one-on-one conversation. Giving students choice or outlets.” Educators reported choosing strategies presented in the PD sessions that they felt were most aligned with their students’ needs. As suggested in the PD, they also seemed to start with a small number of strategies and to incorporate additional strategies over time.

Reappraising interactions with students

Educators reported reappraising interactions with students and increasing their focus on student support. Some educators reported that this was the result of having a greater understanding of student traumatic stress and therefore feeling less offended, inconvenienced, or reactive to student behaviors. For example, Mrs. Thibault described that as a result of participating in the PD,

I really try to think about what the what the root of their behavior could be. So not just assuming that they’re behaving poorly because they want to behave poorly. But where is this coming from? What is causing it? And how can I help them? What can I do for them to make things a little bit smoother or a little bit easier for them?

The school’s administrators observed this in staff as well. For example, Ms. Anderson explained, “[The intervention] helped lessen the amount of times [staff] ended up coming to me for things that they were able to handle and/or look at differently and think to themselves, ‘What could I do differently?’ or ‘How can I look at this kid differently?”’ She continued, “[They realized] this is not an emergency situation.” The data suggest that educators slowed down in their reactions to students and thought more flexibly and empathetically about student behaviors.

Increased collaboration with colleagues

Across interview and survey data, educators reported increased collaboration with colleagues to support students and families with experiences of trauma. For example, Ms. Tierney described that the PD sessions gave staff common language to speak about trauma and gave her language to challenge hurtful remarks that she heard about students. She explained,

Just helping shift the conversation about the way that we talk about these kids. Because I would find it very frustrating when I would be in meetings with other teachers and they would say things like, “Oh, he’s bringing the other good kids down,” and I just have to say “They’re all good kids. Even when they’re trying to assault you with scissors, it means something else.” So, I think helping shift that conversation gave me the language to change the way we talked about those kids.

On the anonymous survey, a veteran classroom teacher described, “I made sure that other staff members who had contact with these children throughout the day also understood why they acted like they did sometimes. I provided different strategies that they could try to use to be successful in their interactions.” A veteran specialized service provider reported seeking out this type of information. They described, “[I] have spoken to colleagues to check deeper into student home life before students are labeled as behavioral or difficult.” This proactive work to understand and collaborate about the multifaceted elements of students’ experiences likely generates greater empathy, more student-centered support, and continued attention to students’ learning.

Enacting self-care strategies

Educators described enacting self-care strategies as a result of participating in the PD intervention. For example, Mrs. Travis described that the Secondary Traumatic Stress and Self-Care Training had a strong influence on her. She explained, “It made me realize how many things I don’t do for myself to take better care of myself. And I have let a lot of things go. And that’s something I’m still working on.” On the anonymous survey, an early career specialized service provider described, “I took more time for me and was more patient with myself. I asked for help when I needed it.” A veteran specialized service provider described, “Understanding that it is normal to feel stress and taking needed breaks.” Participants stressed that this became increasingly critical during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Disconfirming evidence

Two interview participants shared sentiments that reflected that the PD intervention did not lead to sustained learning or shifts in teaching practices for all PD participants. This may have been due to the unforeseen but challenging context (i.e., the COVID-19 pandemic and remote teaching) that followed the PD intervention and in which educators would have implemented their learning. First, Ms. Testa said, “To be honest, I can’t really remember everything we’ve talked about. I feel that it’s kind of gone out of my brain. I feel like I’m just so focused on, to be honest, just hour by hour, day by day [during the COVID-19 pandemic].” Mrs. Taylor explained that educators were experiencing new and increased responsibilities while hybrid teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. She felt that her colleagues were struggling to balance academic instruction and social and emotional supports for students in the limited in-person time they had. Mrs. Taylor acknowledged the need for students to be regulated to be available for learning, but expressed that educators felt conflicted between meeting academic mandates and making time for social and emotional learning and supports.

Discussion

This study sought to identify the learning and shifts in teaching practices that educators reported at the end of Year 1 of a trauma-informed schools PD intervention. Educators reported greater understandings of the impact of trauma and secondary traumatic stress; increased empathy toward students, families, and colleagues, and compassion for self; enacting proactive strategies; reappraising interactions with students; increased collaboration with colleagues; and enacting self-care strategies. These findings extend previous research by providing evidence of staff outcomes, including shifts in teaching practices, that may be expected from educator participation in a Tier 1 trauma-informed schools PD intervention.

In addition, educators’ descriptions of these shifts yielded insight about their sequencing. Educators described that recognizing student behavior as trauma responses (increased understandings of trauma) led them to feel greater empathy toward students, and as a result, to enact strategies to support students (e.g., shifts in practices). This suggests that increased empathy may be an important mechanism through which educator implementation of trauma-informed practices is facilitated. This aligns with the prosocial classroom model (Jennings and Greenberg, 2009), which suggests that educators’ abilities to understand and recognize underlying causes of emotions and behavior may support them in responding with greater empathy. Previous research also suggests that invoking an empathetic mindset facilitates behavioral change in teachers, including less punitive discipline practices (Okonofua et al., 2016). Okonofua et al. (2016) found that a brief online intervention encouraged teachers to understand students’ negative feelings and experiences, maintain positive relationships amidst student misbehavior, and build and sustain trusting relationships to improve student behavior. The intervention also reduced suspension rates in half. This reinforces the idea that empathy may be an important mechanism through which desired outcomes of trauma-informed PD (e.g., maintaining positive relationships amidst student misbehavior, reducing exclusionary disciple) are facilitated. Empathy interventions have also been shown to be efficacious in improving client relationships and support amongst therapists, doctors, and nurses (Teding van Berkhout and Malouff, 2016). Thus, further exploration of empathy as a potential mechanism of change in the implementation of trauma-informed practices may offer important and novel insight for the development of trauma-informed schools.

An additional sign of increased social and emotional competence, educators in the present study reported reappraising interactions with students (Jennings and Greenberg, 2009). This suggests increased self-regulation on the part of educators: rather than responding with potential feelings of frustration, irritation, or anger, participants reported considering the broader circumstances that could be impacting students and providing supports. Others have highlighted the importance of adult self-regulation for successful implementation of trauma-informed practices. As succinctly described by Perry and Winfrey (2021), “A dysregulated adult cannot regulate a dysregulated child” (p. 284). Therefore, educators’ abilities to self-regulate when confronted with students’ intense emotions and challenging behaviors are likely critical to their effectiveness in responding with compassionate and well-reasoned supports. Educators’ self-regulation skills should be explored as an additional potential mechanism of successful implementation of trauma-informed practices.

In this study, educators also reported enacting proactive strategies, such as intentional grouping, offering choices, and increasing their attention to relationship building. These align with instructional and non-instructional strategies shared in this intervention and other trauma-informed schools PD (e.g., Cole et al., 2013; Perry and Graner, 2018; McIntyre et al., 2019). These strategies may reduce student challenges and increase engagement, creating more conductive learning experiences and environments for all students. In addition, educators reported increased collaboration with colleagues arising from their stronger understandings of trauma. They reported reaching out to colleagues to brainstorm supports for students; having conversations that considered student experiences, strengths, and challenges beyond academics; and the value of having shared language to engage in these conversations. This increased collaboration, especially about students with complex needs, may improve student support and outcomes (Ronfeldt et al., 2015; McLeskey et al., 2017).

Educators reported enacting self-care strategies both prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educators recognized that their effectiveness in the classroom, especially in challenging situations, depended on their own wellbeing (Jennings and Greenberg, 2009). Of note, although self-care may have been increasingly important during the COVID-19 pandemic, educators may have also felt more restricted in their abilities to engage in self-care due to increased family responsibilities and safety concerns. In addition, teaching responsibilities shifted, with new job demands (e.g., implementing safety protocols) and changes in job resources (e.g., reduced opportunities for in-person collaboration; Green and Bettini, 2020). As such, educators may have perceived their workloads as less manageable, an identified risk factor for emotional exhaustion (Bettini et al., 2017). Careful attention to educator wellbeing is needed as the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic continue to unfold, educator job demands and resources continue to shift, and a considerable number of educators report that they may leave the profession earlier than they had previously planned (e.g., Zamarro et al., 2022). Training in secondary traumatic stress and self-care is likely ever more important during this time and in responding to consequences for years to come.

This study also contributes an example of a multifaceted trauma-informed schools PD intervention. As evidence on trauma-informed schools PD accumulates, future research should investigate the necessary components, duration, and intensity of PD needed to facilitate changes in teaching practices and student outcomes. In the current study, there is some evidence that classroom coaching with a subset of teachers, at least in part, may have facilitated or reinforced learning of the broader staff. The coached teachers reported collaborating with their colleagues related to the PD content and being sought out as resources on trauma. Sun et al. (2013) refer to this as spillover, whereby additional informal learning happens as the result of some educators participating in formal PD opportunities (in this case, coaching). A cautious interpretation of evidence from the present study suggests that when resources are limited, classroom coaching for a subset of staff may still generate favorable outcomes for the broader staff. Future research should investigate how the dispositions and roles (both formal and informal) of these staff, as well as school culture (e.g., openness to collaboration), influence the ability for coached staff to become internal resources on trauma and if and how this promotes ongoing implementation and sustainability of trauma-informed teaching practices.

Limitations

It is important to consider the limitations of this study. First, these results are from one elementary school; although promising, future research is needed to determine if similar outcomes can be achieved in additional schools. Next, this study relies on self-report data rather than structured observations. It is possible that educators’ reports of their actions do not match actual implementation. However, educators were asked to provide examples to gain a more detailed understanding of their shifts in teaching practices; these examples aligned with insights shared by school administrators. The study is limited by a low survey response rate (36.1%). The survey was administered during the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic and competing demands likely impacted the response rate. In recognition of these competing demands, this study also recruited a convenience sample of interviewees. This likely affected the range of experiences with the PD that was captured. It is possible that interview and survey participants were those most invested in the intervention. Nonetheless, more than one-fourth of PD participants were interviewed, allowing a variety of participant perspectives to be captured.

As the study’s author implemented the PD and conducted the interviews, social desirability bias may have been high (Nederhof, 1985). However, an authentic understanding of educators’ learning and implementation of practices was sought by soliciting stories and gathering data through an anonymous survey. Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on this study. Although all three PD sessions were delivered prior to a shift to remote teaching, it is unclear how results may have differed if educators had continued with in-person instruction for the remainder of the school year or without the influence of a pandemic. Many educators reported that the COVID-19 pandemic surfaced new opportunities for application of the PD content. However, a smaller number reported that the stress of the pandemic made the retrieval and application of new learning difficult.

Implications for policy and future research

The COVID-19 pandemic has been associated with myriad types of adversity and trauma for children (e.g., Unwin et al., 2022). Thus, some have called for increased adoption of trauma-informed schools PD approaches (e.g., Sparks, 2020). However, educator stress is also heightened (e.g., Baker et al., 2021), making the adoption of new initiatives challenging. Thoughtful work is needed to effectively support school communities as they navigate the evolving landscape of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The present study, and increased attention to trauma-informed schools PD approaches during the COVID-19 pandemic, raise another important issue. Despite educators feeling unprepared to meet the needs of their students who have experienced trauma (e.g., National Council of State Education Associations, 2019; Koslouski and Stark, 2021), preservice training on the impacts of trauma on students is not yet widespread (Pierrottet, 2022). For example, only four U.S. states require preservice training on trauma (for an example, see Indiana General Assembly, 2020; Pierrottet, 2022). Given the high prevalence of potentially traumatic events in children’s lives (Bethell et al., 2017), the negative consequences of trauma on learning (e.g., Perfect et al., 2016), and knowledge of effective practices to promote learning for these students (e.g., Perry and Graner, 2018), preservice teachers should be trained in this content. The COVID-19 pandemic, and increased attention to student and educator wellbeing, may present an opportunity to spark institutional change and support (e.g., accreditation and licensure requirements) for more widespread preservice training in trauma-informed teaching practices.

Finally, continued research on the implementation and outcomes of trauma-informed schools PD approaches is needed. To date, there are very few peer reviewed trauma-informed schools PD studies that present a logic model along with outcomes (for examples, see Dorado et al., 2016; Schimke et al., 2022). This is an important next step in trauma-informed schools PD implementation to allow for comparisons and replication of approaches. The present study provides important evidence of potential outcomes of trauma-informed schools PD and identifies educator empathy and self-regulation as potential mechanisms of trauma-informed practice implementation. Future research is needed to investigate if and how the outcomes presented in the present study can be replicated in additional schools and test educator empathy and self-regulation as potential mechanisms facilitating the implementation of trauma-informed practices.

Conclusion

How we proceed in healing from the COVID-19 pandemic will shape our future for decades to come. Supporting children—who are highly vulnerable to trauma—and those who work with them is crucial to the future of our society. Trauma-informed schools PD may be an increasingly important protective factor for large numbers of students and educators. As school communities come back together to heal, teach, and learn during and following the pandemic, there is an urgent need for careful implementation and continued investigation of trauma-informed schools PD approaches.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article is unavailable due to IRB protections.

Ethics statement

This study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the Boston University Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

Data collection and analysis were funded by the Boston University Wheelock College of Education and Human Development’s Graduate Research and Scholarship Award (GRASA).

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Drs. Michelle Porche, Jennifer Greif Green, Melissa Holt, and Renée Spencer for helpful comments and guidance with this study. I wish to extend an additional thank to Dr. Michelle Porche for her ongoing mentorship in the preparation of this manuscript. Finally, thank you to the study participants for their engagement in this study and dedication to students.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ The survey and interview samples likely overlapped. However, due to the anonymous nature of the survey, data could not be matched. Therefore, survey respondents were not given pseudonyms. If they had been given unique pseudonyms, study participants may have had two pseudonyms (one for survey data, one for interview data). Instead, survey respondents are identified by their teaching role and years of experience. Interview participants’ teaching roles and years of experience can be found in Table 2.

References

Alexander, K. L., Entwisle, D. R., and Kabbani, N. S. (2001). The dropout process in life course perspective: early risk factors at home and school. Teach. Coll. Record 103, 760–822. doi: 10.1111/0161-4681.00134

Avery, J. C., Morris, H., Galvin, E., Misso, M., Savaglio, M., and Skouteris, H. (2021). Systematic review of school-wide trauma-informed approaches. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 14, 381–397. doi: 10.1007/s40653-020-00321-1

Baker, C. N., Peele, H., Daniels, M., Saybe, M., Whalen, K., Overstreet, S., et al. (2021). The experience of COVID-19 and its impact on teachers’ mental health, coping, and teaching. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 50, 491–504. doi: 10.1080/2372966X.2020.1855473

Bergen, N., and Labonté, R. (2020). “Everything is perfect, and we have no problems”: detecting and limiting social desirability bias in qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 30, 783–792. doi: 10.1177/1049732319889354

Bergman, A. S., Axberg, U., and Hanson, E. (2017). When a parent dies – a systematic review of the effects of support programs for parentally bereaved children and their caregivers. BioMed. Central Palliat. Care 16:39. doi: 10.1186/s12904-017-0223-y

Bethell, C. D., Davis, M. B., Gombojav, N., Stumbo, S., and Powers, K. (2017). Issue Brief: Adverse Childhood Experiences among US Children. Baltimore, MD: Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative.

Bettini, E., Jones, N., Brownell, M., Conroy, M., Park, Y., Leite, W., et al. (2017). Workload manageability among novice special and general educators: relationships with emotional exhaustion and career intentions. Remed. Spec. Educ. 38, 246–256. doi: 10.1177/0741932517708327

Bloom, S. L. (1994). “The Sanctuary Model: developing generic inpatient programs for the treatment of psychological trauma,” in Handbook of Post-Traumatic Therapy, a Practical Guide to Intervention, Treatment, and Research, eds M. B. Williams and J. F. Sommer (Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing), 474–491.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? what counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 18, 328–352. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

Chafouleas, S. M., Johnson, A. H., Overstreet, S., and Santos, N. M. (2016). Toward a blueprint for trauma-informed service delivery in schools. Sch. Ment. Health 8, 144–162. doi: 10.1007/s12310-015-9166-8

Chan, M. K., Sharkey, J. D., Lawrie, S. I., Arch, D. A. N., and Nylund-Gibson, K. (2021). Elementary school teacher well-being and supportive measures amid COVID-19: an exploratory study. Sch. Psychol. 36, 533–545. doi: 10.1037/spq0000441

Cole, S. F., Eisner, A., Gregory, M., and Ristuccia, J. (2013). Helping Traumatized Children Learn: Creating and Advocating for Trauma-Sensitive Schools, Vol. 2. Boston, MA: Massachusetts Advocates for Children.

Cole, S. F., O’Brien, J. G., Gadd, M. G., Ristuccia, J., Wallace, D. L., and Gregory, M. (2005). Helping Traumatized Children Learn, Vol. 1. Boston, MA: Massachusetts Advocates for Children.

Cook, C. R., Coco, S., Zhang, Y., Fiat, A. E., Duong, M. T., Renshaw, T. L., et al. (2018). Cultivating positive teacher-student relationships: preliminary evaluation of the Establish-Maintain-Restore (EMR) method. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 47, 226–243. doi: 10.17105/SPR-2017-0025.V47-3

Craig, S. (2016). Trauma-Sensitive Schools: Learning Communities Transforming Children’s Lives, K–5. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Creswell, J. W., and Miller, D. L. (2000). Getting good qualitative data to improve educational practice. Theory Into Pract. 39, 124–130. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2

Creswell, J. W., and Plano Clark, V. (2017). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Czeisler, M. É, Lane, R. L., Petrosky, E., Wiley, J. F., Christensen, A., Njai, R., et al. (2020). Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 69, 1049–1057. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1

Desimone, L. M., and Garet, M. S. (2015). Best practices in teachers’ professional development in the United States. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 7, 252–263. doi: 10.25115/psye.v7i3.515

Dorado, J. S., Martinez, M., McArthur, L. E., and Leibovitz, T. (2016). Healthy environments and response to trauma in schools (HEARTS): a whole-school, multi-level, prevention and intervention program for creating trauma-informed, safe and supportive schools. Sch. Ment. Health 8, 163–176. doi: 10.1007/s12310-016-9177-0

Duong, M. T., Pullmann, M. D., Buntain-Ricklefs, J., Lee, K., Benjamin, K. S., Nguyen, L., et al. (2019). Brief teacher training improves student behavior and student-teacher relationships in middle school. Sch. Psychol. 34, 212–221. doi: 10.1037/spq0000296

Fixsen, D. L., Naoom, S. F., Blake, K. A., Friedman, R. M., and Wallace, F. (2005). Implementation Research: A Synthesis of the Literature. Tampa, FL: University of South Florida.

Fortuna, L. R., Tolou-Shams, M., Robles-Ramamurthy, B., and Porche, M. V. (2020). Inequity and the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color in the United States: the need for a trauma-informed social justice response. Psychol. Trauma 12, 443–445. doi: 10.1037/tra0000889

Gherardi, S. A., Flinn, R. E., and Jaure, V. B. (2020). Trauma-sensitive schools and social justice: a critical analysis. Urban Rev. 52, 482–504. doi: 10.1007/s11256-020-00553-3

Green, J. G., and Bettini, E. (2020). Addressing teacher mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Teach. Coll. Rec.

Guetterman, T. C., Fetters, M. D., and Creswell, J. W. (2015). Integrating quantitative and qualitative results in health science mixed methods research through joint displays. Ann. Family Med. 13, 554–561. doi: 10.1370/afm.1865

Halladay Goldman, J., Danna, L., Maze, J. W., Pickens, I. B., and Ake, I. I. I. G. S. (2020). Trauma-Informed School Strategies During COVID-19. Los Angeles, CA: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress.

Hamoudi, A., Murray, D. W., Sorensen, L., and Fontaine, A. (2015). Self-Regulation and Toxic Stress: A Review of Ecological, Biological, and Developmental Studies of Self-Regulation and Stress (OPRE Report # 2015-30). Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Hanson, R. F., and Lang, J. (2016). A critical look at trauma-informed care among agencies and systems serving maltreated youth and their families. Child Maltreat. 21, 95–100. doi: 10.1177/1077559516635274

Harper, K., and Temkin, D. (2019). Responding to Trauma Through Policies to Create Supportive Learning Environments. Bethesda, MD: Child Trends.

Harris, M., and Fallot, R. D. (2001). “Envisioning a trauma-informed service system: a vital paradigm shift,” in New Directions for Mental Health Services. Using Trauma Theory to Design Service Systems, eds M. Harris and R. D. Fallot (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 3–22. doi: 10.1002/yd.23320018903

Hobbs, C., Paulsen, D., and Thomas, J. (2019). “Trauma-informed practice for pre-service teachers,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education, ed. G. W. Noblit (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Indiana General Assembly (2020). HB 1283. Available on line at: http://iga.in.gov/legislative/2020/bills/house/1283 (accessed August 14, 2022).

Jennings, P. A., and Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 79, 491–525. doi: 10.3102/0034654308325693

Koslouski, J. B., and Porche, M. V. (2020). Engaging School Administrators in Creating Trauma-Sensitive Procedures and Policies [Poster]. Washington, D.C.: The Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association.

Koslouski, J. B., and Stark, K. (2021). Promoting learning for students experiencing adversity and trauma: the everyday, yet profound, actions of teachers. Element. Sch. J. 121, 430–453. doi: 10.1086/712606

Maynard, B. R., Farina, A., Dell, N. A., and Kelly, M. S. (2019). Effects of trauma-informed approaches in schools: a systematic review. Campbell Syst. Rev. 15:e1018. doi: 10.1002/cl2.1018

McIntyre, E. M., Baker, C. N., and Overstreet, S., and New Orleans Trauma-Informed Schools Learning Collaborative (2019). Evaluating foundational professional development training for trauma-informed approaches in schools. Psychol. Serv. 16, 95–102. doi: 10.1037/ser0000312

McLeskey, J., Barringer, M. D., Billingsley, B., Brownell, M., Jackson, D., Kennedy, M., et al. (2017). High-Leverage Practices in Special Education. Arlington, VA: Council for Exceptional Children & CEEDAR Center.

Milner, H. R., Cunningham, H. B., Delale-O’Connor, L., and Kestenberg, E. G. (2019). These Kids are out of Control:” Why We Must Reimagine “Classroom Management” for Equity. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

National Council of State Education Associations (2019). Addressing the Epidemic of Trauma in Schools. Available online at: https://www.nea.org/sites/default/files/2020-09/Addressing%20the%20Epidemic%20of%20Trauma%20in%20Schools%20-%20NCSEA%20and%20NEA%20Report.pdf (accessed August 10, 2022).

Nederhof, A. J. (1985). Methods of coping with social desirability bias: a review. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 15, 263–280. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420150303

Okonofua, J. A., Paunesku, D., and Walton, G. M. (2016). Brief intervention to encourage empathic discipline cuts suspension rates in half among adolescents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113:5221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523698113

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., and Johnson, R. B. (2006). The validity issue in mixed research. Res. Sch. 13, 48–63.

Overstreet, S., and Chafouleas, S. M. (2016). Trauma-informed schools: introduction to the special issue. Sch. Ment. Health 8, 1–6. doi: 10.1007/s12310-016-9184-1

Patrick, S. W., Henkhaus, L. E., Zickafoose, J. S., Lovell, K., Halvorson, A., Loch, S., et al. (2020). Well-being of parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey. Pediatrics 146:e2020016824. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-016824

Perfect, M. M., Turley, M. R., Carlson, J. S., Yohanna, J., and Saint Gilles, M. P. (2016). School-related outcomes of traumatic event exposure and traumatic stress symptoms in students: a systematic review of research from 1990 to 2015. Sch. Ment. Health 8, 7–43. doi: 10.1007/s12310-016-9175-2

Perry, B. D., and Graner, S. (2018). The Neurosequential Model in Education: Introduction to the NME Series: Trainer’s Guide. Houston, TX: The ChildTrauma Academy Press.

Perry, B. D., Pollard, R., Blakley, T. L., Baker, W. L., and Vigilante, D. (1995). Childhood trauma, the neurobiology of adaption, and “use-dependent” brain development of the brain: how “states” become “traits”. Infant Ment. Health J. 16, 271–291.

Perry, B. D., and Winfrey, O. (2021). What Happened to You? Conversations on Trauma, Resilience, and Healing. New York, NY: Flatiron Books.

Pierrottet, C. (2022). Building Trauma-Informed School Systems: National Association of State Boards of Education. Available online at: https://www.nasbe.org/building-trauma-informed-school-systems/ (accessed August 11, 2022).

Purtle, J. (2020). Systematic review of evaluations of trauma-informed organizational interventions that include staff trainings. Trauma Viol. Abuse 21, 725–740. doi: 10.1177/1524838018791304

Racine, N., McArthur, B. A., Cooke, J. E., Eirich, R., Zhu, J., and Madigan, S. (2021). Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 175, 1142–1150. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482

Ronfeldt, M., Farmer, S. O., McQueen, K., and Grissom, J. A. (2015). Teacher collaboration in instructional teams and student achievement. Am. Educ. Res. J. 52, 475–514. doi: 10.3102/0002831215585562

Roseby, S., and Gascoigne, M. (2021). A systematic review on the impact of trauma-informed education programs on academic and academic-related functioning for students who have experienced childhood adversity. Traumatology 27, 149–167. doi: 10.1037/trm0000276

Safe Schools New Orleans (2022). Trauma-Informed Schools Policy Checklist. Available online at: http://safeschoolsnola.tulane.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/121/2020/07/Policy-Review-Checklist.pdf (accessed August 14, 2022).

Schimke, D., Krishnamoorthy, G., Ayre, K., Berger, E., and Rees, B. (2022). Multi-tiered culturally responsive behavior support: a qualitative study of trauma-informed education in an Australian primary school. Front. Educ. 7:866266. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.866266

Siegfried, C. B., and Blackshear, K., National Child Traumatic Stress Network, and The National Resource Center on Adhd: A Program of Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (CHADD). (2016). Is it ADHD or Child Traumatic Stress? a Guide for Clinicians. Los Angeles, CA: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress.

Sonsteng-Person, M., and Loomis, A. M. (2021). The role of trauma-informed training in helping Los Angeles teachers manage the effects of student exposure to violence and trauma. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 14, 189–199. doi: 10.1007/s40653-021-00340-6

Sparks, S. D. (2020). Triaging for Trauma During COVID-19. Available online at: https://www.edweek.org/leadership/triaging-for-trauma-during-covid-19/2020/09?intc=eml-contshr-shr-desk (accessed November 11, 2020).

Stratford, B., Cook, E., Hanneke, R., Katz, E., Seok, D., Steed, H., et al. (2020). A scoping review of school-based efforts to support students who have experienced trauma. Sch. Ment. Health 12, 442–477. doi: 10.1007/s12310-020-09368-9

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] (2014). SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Adminstration.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] (2020). Intimate Partner Violence and Child Abuse Considerations During COVID-19. Washington, DC: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Sugai, G., and Horner, R. H. (2009). Responsiveness-to-intervention and school-wide positive behavior supports: integration of multi-tiered system approaches. Exceptionality 17, 223–237. doi: 10.1080/09362830903235375

Sun, M., Penuel, W. R., Frank, K. A., Gallagher, H. A., and Youngs, P. (2013). Shaping professional development to promote the diffusion of instructional expertise among teachers. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 35, 344–369. doi: 10.3102/0162373713482763

Swedo, E., Idaikkadar, N., Leemis, R., Dias, T., Radhakrishnan, L., Stein, Z., et al. (2020). Trends in U.S. emergency department visits related to suspected or confirmed child abuse and neglect among children and adolescents aged <18 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, January 2019–September 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 69, 1841–1847. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6949a1

Teding van Berkhout, E., and Malouff, J. M. (2016). The efficacy of empathy training: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Counsel. Psychol. 63, 32–41. doi: 10.1037/cou0000093

Thomas, M. S., Crosby, S., and Vanderhaar, J. (2019). Trauma-informed practices in schools across two decades: an interdisciplinary review of research. Rev. Res. Educ. 43, 422–452. doi: 10.3102/0091732X18821123

Unwin, H. J. T., Hillis, S., Cluver, L., Flaxman, S., Goldman, P. S., Butchart, A., et al. (2022). Global, regional, and national minimum estimates of children affected by COVID-19-associated orphanhood and caregiver death, by age and family circumstance up to Oct 31, 2021: an updated modelling study. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 6, 249–259. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00005-0

Wittich, C., Wogenrich, C., Overstreet, S., and Baker, C. N., and The New Orleans Trauma-Informed Schools Learning Collaborative. (2020). Barriers and facilitators of the implementation of trauma-informed schools. Res. Pract. Sch. 7, 33–48.

Zamarro, G., Camp, A., Fuchsman, D., and McGee, J. B. (2022). Understanding how COVID-19 has Changed Teachers’ Chances of Remaining in the Classroom. (EdWorkingPaper: 22-542). Available online at: https://doi.org/10.26300/2y0g-bw09 (accessed August 14, 2022).

Keywords: trauma-informed schools, shifts in practices, teacher self-regulation, professional development (PD), teacher empathy

Citation: Koslouski JB (2022) Developing empathy and support for students with the “most challenging behaviors:” Mixed-methods outcomes of professional development in trauma-informed teaching practices. Front. Educ. 7:1005887. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1005887

Received: 28 July 2022; Accepted: 18 August 2022;

Published: 15 September 2022.

Edited by:

Helen Elizabeth Stokes, The University of Melbourne, AustraliaReviewed by:

Tom Brunzell, The University of Melbourne, AustraliaLyra L’Estrange, Queensland University of Technology, Australia

Copyright © 2022 Koslouski. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jessica B. Koslouski, SmVzc2ljYS5rb3Nsb3Vza2lAdWNvbm4uZWR1

Jessica B. Koslouski

Jessica B. Koslouski