95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 30 September 2022

Sec. Higher Education

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.775303

Matthew J. Mayhew1*

Matthew J. Mayhew1* Christa E. Winkler2

Christa E. Winkler2 B. Ashley Staples1

B. Ashley Staples1 Kevin Singer3

Kevin Singer3 Musbah Shaheen1

Musbah Shaheen1 Alyssa N. Rockenbach3

Alyssa N. Rockenbach3Background: Evangelical Christian college students simultaneously experience the privileges that accompany dominant religious identities and feel a need to conceal their identity and perspectives on college campuses. Consistently and empirically, the college campus has been studied for its potential to help students develop appreciative attitudes toward religious, secular, and spiritual worldviews. Yet, few studies have investigated evangelical Christian appreciation longitudinally over 4 years of college, and even fewer through the additional use of a mixed-methods design.

Purpose: This inquiry examined if and how college students developed an appreciation of evangelical Christianity over 4 years of college.

Methods: This paper used data gathered through the Interfaith Diversity Experiences and Attitudes Longitudinal Survey (IDEALS), a nationally-representative, mixed-methods study that included survey data collection from 9,470 students at 122 colleges and universities over 3 time points, and 18 qualitative case studies conducted across institutions of various sizes, locations, and affiliations.

Results: Using latent growth modeling, we demonstrated that overall appreciation for evangelical Christianity developed during college and was related to institutional cultures that invited and embraced worldview diversity as well as religiously-inclusive campus climates and practices. Related qualitative insights storied change in evangelical appreciation that centered on personal relationships with evangelicals, efforts to understand evangelical viewpoints, and a recognition that Christian students often have the privilege of operating from unexamined beliefs.

Conclusion and Implications: Study results provide recommendations for educational practices that support student growth from tolerance to appreciation for evangelical Christianity.

Evangelical Christian college students simultaneously experience the privileges that accompany dominant religious identities in the United States and may feel a need to conceal their religious and spiritual expression on many college campuses. Evangelical Christian students generally enjoy privilege, as their status aligns with many of the values and systems upon which U.S. society and the ideas of the American University were founded (Seifert, 2007). However and concurrently, research on evangelical students has reported experiences of cultural incongruence and social status ambiguity (Moran et al., 2007)—placing these students in the awkward position of negotiating the privileges they hold and from which they receive benefits with their “out-voiced and misunderstood” (Moran et al., 2007, p. 28) lived experiences on college campuses. In light of the complex reality of evangelical Christians in higher education, we ask the following questions: How do college students develop an appreciative understanding of evangelical Christianity?

Developing appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christians is an important empirical consideration for the study of college and its impact on students. Paradigmatically, we assume that development can and does occur during college and that such growth can be accessed through measurement. Moving from tolerance to appreciation, we argue that the development of appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christians—or any social identity group—emerges from respecting the profound differences between religious, secular, and spiritual worldviews1 and finding common ground among them (Eck, 1993; Patel and Meyer, 2011; Bowman et al., 2017). Thus, appreciative attitudes create a foundation for an individual’s “proclivities for productive relationships across difference by way of their degree of positive regard for people who do not share their worldviews” (Mayhew & Rockenbach, 2021, p. 4).

Consistently and empirically, studies have documented how the college experience helps students develop appreciative attitudes toward people who hold identities different than their own (see Mayhew et al., 2016). The genuine appreciation of an identity group acknowledges that people in the group make positive contributions to society and are ethical, among other attributes. Recent scholarship suggests that students’ learning through exposure to religious, secular, and spiritual differences, and associated dissonance and ideological wrestling, might be related to helping students develop appreciative attitudes for evangelical Christian students (Mayhew et al., 2017), as well atheists (Bowman et al., 2017), Jews (Mayhew et al., 2018), Latter Day Saints (Rockenbach et al., 2017), and Muslims (Rockenbach et al., 2017). That said, no studies have investigated evangelical Christian appreciation longitudinally over 4 years of college and certainly none have adopted a mixed-methods approach for doing so. As such, this undertaking is distinctive in its ability to track student growth in evangelical appreciative attitudes over 3 time points during 4 years in college and provide insights into the voiced reasons students offer for this form of development occurring.

Serving as the conceptual framework for this study, the interfaith learning and development (ILD) model, offered by Mayhew and Rockenbach (2021) as an “emergent but valid theory-in-practice,” provides a renewed perspective for thinking about “religion and spirituality, students’ approaches to their own religious and spiritual selves and … the practices and mechanisms needed to help students grow in these areas” (p. 2). The ILD model defines four main empirically-based collegiate outcomes: pluralism orientation, self-authored worldview commitment, appreciative knowledge, and appreciative attitudes. The outcome presented in this paper—appreciative attitudes—represents a theoretical sophistication beyond tolerance that is “attuned to the nuanced impressions students have of specific groups” (Mayhew & Rockenbach, 2021, p. 4). The construct of appreciative attitudes represents students’ proclivities for productive interactions across difference by measuring the degree of positive regard students hold for those who do not share their worldview.

To explain the specific role of the collegiate environment in fostering interfaith learning outcomes, the ILD accounts for students’ pre-college characteristics, including social identities (e.g., gender, race) and high-school interfaith interactions. The framework then conceptualizes the campus environment as nested spheres of influence that include a behavioral context (i.e., formal and informal social and academic engagement), a disciplinary context (i.e., academic major), a relational context (e.g., supportive, coercive, or insensitive interactions), an institutional context (e.g., organizational behaviors and culture), and a larger national context (Figure 1). Together, these contexts holistically frame the interactions students engage within the learning environment. The model and its related constructs are useful for understanding how college experiences and environments contribute to students’ development of appreciative attitudes toward evangelicals and evangelical Christianity.

To contextualize this study, we first discuss evangelical Christianity in the religious landscape in the United States. Then, we turn to research about evangelical Christians in higher education by focusing on how evangelical college students experience and perceive the campus climate. Finally, we conclude by highlighting the dynamics of interfaith learning and development related to interactions between evangelicals and non-evangelicals within educational settings.

Christian identities have been defined in many ways and from multiple perspectives. Although most who identify as Christian center Biblical teachings and the person of Jesus Christ, their expressions of these tenets differs often, but not exclusively, based on the histories, theologies, and hermeneutics. Most Christians affiliate with Protestant, Catholic, or Eastern Orthodox denominations (Smidt, 2007), but evangelical Christians are often distinguished within Protestantism for holding an additional core set of beliefs, including Biblical infallibility, the emphasis on the crucifixion as the ultimate sacrifice making humanity's redemption possible, eternal salvation as only available through belief in Jesus Christ, and an emphasis on sharing the knowledge Jesus Christ as a savior is possible for anyone (National Association of Evangelicals, 1971). These characteristics highlight the ways in which evangelicals may define themselves in relation to other Protestants or Christians in general.

For many, especially in the United States, evangelical Christianity is adopted as a system of personal beliefs and convictions and as a sociocultural heuristic with pronounced political implications. For example, those who hold strong evangelical beliefs or who report having a born-again experience are more likely to agree that the United States was founded on Christian principles (Hammond & Hunter, 1984). Evangelical young adults are also more likely to express conservative political views and attitudes about family values, moral absolutes, and the role of legislation in upholding them (Bielo, 2011; Bryant, 2011; Markofski, 2015). Given this historical association between evangelical Christianity and conservative politics, it should not come as a surprise that many white evangelicals cast their votes for Republican presidential candidate, Donald Trump (Bailey, 2016; Jones, 2018; Weber, 2018). Understanding attitudes toward evangelicals thus should involve knowledge of religious beliefs and values and consideration of how the evangelical identity manifests itself in the fabric of social and political life.

Much like other socially-constructed or influenced identities, those who identify as evangelical Christians are not monolithic in their beliefs and attitudes, despite having shared tendencies. Evangelicalism has shifted historically in its theology, mission, conception of church life, connection to church history, and political involvement (Bielo, 2011; Pally, 2011). Indeed, there is a documented lack of consensus among this group about the role of religion in politics, public education, and policies related to gender and sexuality (Smith, 2000; Markofski, 2015). Evangelicals differ in their political engagement, their orientation toward the separation of church and state, the state of activism in civil society, and the role of public critique of the government (Pally, 2011; Markofski, 2015). For example, in the wake of the 2016 elections, many evangelicals attempted to distance themselves from the label “evangelical” out of fear of association with the far political right (Jones, 2018; Religion News Service, 2020) while others dropped the affiliation altogether (Weber, 2017). Although evangelical Christianity might be associated with some values and volitions that impact public life, the generalization of those associations to encompass anyone who adopts the evangelical label or affiliation may be understandable but misguided.

Research on evangelical college students provides compelling evidence that their attitudes and experiences vary even though they share the same religious affiliation. Indeed, evangelical college students differ significantly in their expressed political and moral values; in fact, intra-group differences are observed consistently in the context of political discourse (Bryant, 2005). Most recently, Lancaster et al. (2019) delineated three groups of first-year evangelical college students whose attitudes and experiences of campus varied: One aligned with more traditional notions of evangelicalism, one with more progressive stances on evangelical Christianity, and a third, referred to as “questioning evangelicals” (p. 496), demonstrating a mix of conservative and progressive attitudes toward evangelicalism. Some evangelical college students strictly adhere to biblical infallibility, the authority of one God, and conservative moral perspectives (Bryant, 2011), while others engage in exploration focused on finding a deep sense of connection with God, a sense of security in their faith, the pursuit of selflessness in action, and a sense of conviction stemming from faith (Foubert et al., 2012). In short, the evangelical identity cannot be essentialized, and neither can the experiences of evangelical students on campus.

Evangelical students seem to grapple with what it means to be authentically evangelical in collegiate environments. A study of evangelical student leaders revealed they are likely to distance themselves from being labeled “religious” as it suggests too much rigidity for a relationship-based faith and avoid being labeled as “spiritual” as it implies a personally-defined, rather than Biblically-defined, belief system (Magolda & Ebben Gross, 2009). Some students experience dissonance between their ways of being and those accepted as “normal” on campus; when unsupported, this dissonance may lead to a sense of alienation both on college campuses and in society (Yancey & Williamson, 2015). Some posit this dissonance ultimately leads to more development and commitment to one’s evangelical worldview, as well as higher levels of engagement in spiritual struggle compared to non-evangelical peers (e.g., Bowman & Small, 2010). Collectively, these studies suggest that dissonance characterizes the evangelical student experience and can be a help or hinderance to development.

Contributing to this idea of dissonance, evangelical students often have a difficult time expressing themselves on college campuses. For example, in Moran et al.’s (2007) study of evangelical students, the terms “out-voiced” and “misunderstood” were used to describe how evangelical Christians perceived themselves on campus. Students “felt that their values, beliefs, and behaviors as evangelical Christians were not only incongruent with the prevailing culture on their campuses but were also not respected to the same degree as those of other religions” (p. 28). Many evangelical students described themselves as a minority group in the context of numerical presence on campus, importantly not in relation to broader sociological conceptualizations of minoritized identities. The evangelical students in Moran et al.’s (2007) study did not recognize the way in which they, as a group, held privileged status in society, in general, and higher education, in particular. This incomprehension is deeply problematic and challenging, especially because this unacknowledged power is often used to perpetuate hegemonic norms that perpetuate harm.

These dynamics result in a campus climate where evangelical Christian students choose, consciously or unconsciously, to downplay their religious identity in order to avoid defensive or argumentative interactions with their peers (Bryant 2005; Moran et al., 2007; Brow et al., 2014). For evangelical college students, navigating the increasingly complex reality of higher education includes holding and benefitting from Christian privilege, managing the tendency of faculty and students to view them as ideologically-homogenous, and concealing their worldviews out of fear of intellectual discrimination. Understanding the delicate interplay of these experiences is instrumental for understanding how attitudes toward evangelicals are shaped in collegiate contexts.

Data from the Pew Research Center (PRC) suggests that, between 2014 and 2017, attitudes of U.S. respondents toward all religious identities improved, except those toward evangelical Christians. Moreover, fewer respondents reported knowing someone who is evangelical over time (PRC, 2017). Although respondents in general felt more warmly toward other groups of Christians such as mainline Protestants and Roman Catholics, attitudes toward evangelicals did not improve. As for higher education environments, Mayhew et al. (2017) conducted an illuminating example of research about attitudes toward evangelicals, which showed that positive attitudes toward evangelicals were strongly associated with students’ worldview identities. In particular, students who identified as Agnostic, atheist, Buddhist, Muslim, Jewish, non-religious, or Secular Humanists were less likely to appreciate evangelicals when compared to other Christians who, in general, were more likely to appreciate evangelicals. The study revealed positive attitudes toward evangelicals were strengthened by challenging encounters, productive campus engagements, and the availability of spaces for support and spiritual expression. The researchers noted that “leaving evangelicals to find their own support during college, either through church or parachurch organizations (e.g., Cru, Navigators, Athletes in Action), curtails opportunities for their involvement in inter- and intra-faith experiences benefitting all students” (Mayhew et al., 2017, p. 227). In other words, positive interactions between evangelicals and non-evangelicals not only spur evangelical students to reflect on their religious beliefs (Bryant, 2005, 2008, 2011; Paredes-Collins & Collins, 2011), but help non-evangelicals build relationships with those whose beliefs and practices are different from their own.

As for the development of appreciative attitudes toward evangelicals over time, little is known in the collegiate context. As an exception, Rockenbach et al. (2017) focused on students’ attitude changes during the first year of college, and showed incoming first-year students expressed general appreciation of evangelicals upon college entry at 52%, which increased to 59% by the end of the first year. This increase was notably lower than the growing appreciation toward all other worldview groups exhibited by first-year students, which increased by 10–15 percentage points over the first year (Rockenbach et al., 2017). Interestingly, perceptions of how welcoming the campus environment was toward evangelicals were similar to perceptions of welcome for Jewish people on campus (i.e., 79% and 78%, respectively), and several points higher than for other minoritized worldview groups at the end of the first year. Although first-year students think the campus climate is more welcoming for evangelical students, they do not appreciate evangelical Christians to the same degree as other religious groups.

What collegiate conditions, educational practices, and experiences help students develop an appreciation of evangelical Christians over 4 years of college and what reasons do campus community members offer for changed appreciation? This study seeks to answer these questions. We hope to provide insight into the ways colleges and universities can support bridge-building between evangelical and non-evangelical students to enhance relationships, mutual understanding, and collective efforts to improve the common good during and beyond the college years.

This mixed-methods study was conducted using data from the Interfaith Diversity Experiences and Attitudes Longitudinal Survey (IDEALS), which examines the impact of campus environments and undergraduate students’ collegiate experiences on educational outcomes, including appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christianity. Using an integrated mixed-methods approach known as explanatory sequential design (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011), we designed the IDEALS project to make meaning of its quantitative results through subsequent examination of qualitative findings.

Data were collected via three sources. The first involved collecting survey data from students and campus stakeholders representing institutions that participated in the IDEALS study at three different time points. The second data source was institutional information merged from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (i.e., IPEDS). Finally, the third source was qualitative data collected during site visits to selected campuses. In the spirit of mixed-methods approaches, the quantitative data collected for this study informed every aspect of the qualitative data collection strategy, from selecting the site visit campuses to data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

IDEALS was administered at 122 colleges and universities across the United States, with the sample stratified by geographic region and institutional religious affiliation. The survey included items that capture the various institutional conditions and educational practices documented for their influence on students’ appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christianity and other religions, secularities, and spiritualities.

IDEALS was administered longitudinally, with Time 1 responses collected in the summer or fall of 2015, Time 2 responses collected in spring or fall of 2016, and Time 3 responses collected in spring of 2019. At Time 1, 20,436 students from 122 institutions responded. At Time 2, the response rate was 43.0%, with 122 institutions represented, and at Time 3 the response rate was 36.0%, with 118 institutions represented. The data used in this study included responses from students who participated in IDEALS during at least two of the three timepoints, resulting in an analytic sample of 9,470 students at 122 institutions. Throughout all analytic steps in this study, robust standard errors were used to account for these complex sampling features of the data, including the clustering of students within institutions. As detailed in Table 1, students and their institutional affiliations were nationally representative.

In addition to the survey and institutional data, case studies were conducted at 18 institutions selected for IDEALS. Results from the quantitative portion of the study informed site selection, data collection, and data analysis for the case studies. Case study site selection occurred following the second wave of survey data collection in spring/fall 2016. At that time, a subset of IDEALS institutions was identified based on their varying degrees of change in interfaith learning and development outcomes among their first-year students and these students' degree of exposure to formal interfaith activities.

The resulting 18 case study sites included institutions ranging in size, from enrollments of fewer than 3,000 students (n = 4; 22%), to those between 3,000 and 12,000 students (n = 4; 22%), and finally, to those with more than 12,000 students (n = 10; 56%). Institutional religious affiliations included: Catholic (n = 4; 22%), evangelical Protestant (n = 1; 6%), mainline Protestant (n = 3; 17%), private nonsectarian (n = 5; 28%), and public (n = 5; 28%). Geographic locations of those institutions spanned the Rocky Mountains (n = 1; 6%), Plains (n = 3; 17%), Great Lakes (n = 3; 17%), New England (n = 1; 6%), Mideast (n = 2; 11%), Southeast (n = 5; 28%), Southwest (n = 2; 11%), and Far West (n = 1; 6%) regions.

Once the sites were identified, campus contacts connected the researchers with their students, faculty, and staff. Case studies included semi-structured interviews with 223 faculty and staff, focus groups with 268 students, and relevant observations of campus spaces and programs. The interview and focus group protocols were designed to elicit rich descriptions of the institutional contexts, practices, and experiences from participants to explain the growth noted among first-year students at each campus. For this study, student voices were of particular interest, as we sought to examine the relevant contexts students offered as reasons for developing appreciative attitudes toward their evangelical peers. Thus, transcripts generated from the student focus groups across the 18 sites formed the basis for the qualitative data examined in this study.

For the purposes of this study, the quantitative analyses included variables that captured the outcome of interest—appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christians—and the various components of the Interfaith Learning and Development Model. The outcome was measured via a theoretically-derived and empirically-validated scale comprised of four items where students rated the extent to which they agreed with the following statements: a) In general, people in this group make positive contributions to society; b) In general, individuals in this group are ethical people; c) I have things in common with people in this group; d) In general, I have a positive attitude toward people in this group. Students rated their level of agreement with a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Reliability of the outcome measure was assessed for the analytic sample at all 3 time points (i.e., Time 1: α = 0.842; Time 2: α = 0.859; Time 3: α = 0.872). Students’ scores on the appreciation measure at Time 1 were standardized using a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1, while scores at Times 2 and 3 were standardized using the mean and standard deviation from the raw scores at Time 1. As a result, scores on the outcome at Time 2 and Time 3 can be interpreted in effect size units as change in students’ appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christianity since Time 1.

A number of variables were included as covariates to capture the various components of the ILD model. Student-level variables were included to measure students’ pre-college characteristics and exposure to interfaith experiences. Student characteristics were captured from students’ self-reported gender identity, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, worldview identification, education generation status, high school GPA, and political leaning. These multi-categorical variables were effect coded in order to compare the effect for one group (e.g., students of a particular race/ethnicity or students of a particular worldview) to the overall group mean of all students. As a result, rather than testing whether each group differed significantly from an arbitrary reference group, we tested whether all groups differed significantly from the overall sample mean (Mayhew & Simonoff, 2015). Students’ pre-college interfaith experiences were then calculated via a single composite score that captured the number of interfaith activities students reported 12 months before coming to college.

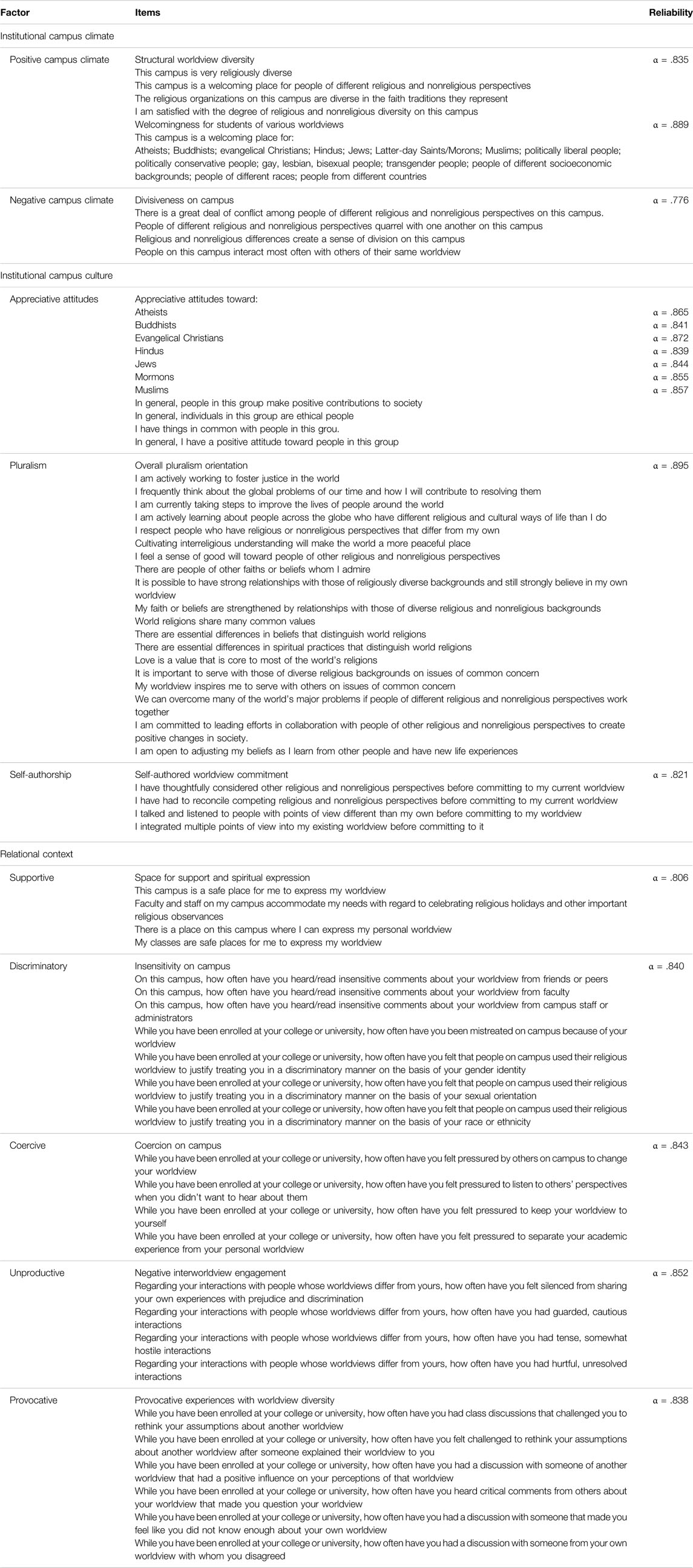

Institutional-level variables were then used to measure various dimensions of the interfaith learning environment, including the national, institutional, and relational contexts in which students’ interfaith experiences occurred. The institutional context included a number of variables measuring campus conditions, organizational behaviors, campus climate, and campus culture. Measures of campus conditions included institutional control (public versus private), selectivity (according to Barron’s Profiles of American Colleges, 2015), and the size of the undergraduate student population. Organizational behaviors were measured by the number of religious, spiritual, or interfaith programs, spaces, curricular opportunities, and diversity policies provided on campus, as reported by an institutional partner. Campus climate was measured with two composite indices—positive and negative climate for worldview diversity. Likewise, campus culture was captured with three composite indices—institutional commitment to appreciative attitudes toward others’ worldviews, pluralism orientation, and self-authored worldview commitment—which were computed by averaging student-level perceptions to obtain an institutional-level score. Similarly, the relational context was measured via composite variables reflecting students’ perception of space for support and spiritual expression, insensitivity on campus, coercion on campus, unproductive interworldview engagement, and provocative experiences with worldview diversity. All items comprising the aforementioned institutional-level measures for the institutional and relational contexts are reported in Table 2, along with their corresponding reliabilities.

TABLE 2. Interfaith learning and development model factors and items for institutional and relational contexts.

Student-level variables were then used to measure the final two components of the ILD model, students’ disciplinary contexts and interfaith engagement behaviors. Students’ disciplinary contexts were measured with a single-item indicator reflecting students’ self-reported academic major. Like other student-level multi-categorical variables, academic major was effect coded to allow for a comparison of each cluster of academic disciplines with the overall sample mean (Mayhew & Simonoff, 2015). Students’ interfaith engagement behaviors were captured by four separate measures. Those measures were disaggregated by whether students’ behaviors were formal (e.g., programmed interfaith activities) or informal (e.g., casual social interactions across religious difference) and academic (i.e., curricular or classroom-based) or social (i.e., co-curricular or extra-curricular). Then, the number of formal academic, informal academic, formal social, and informal social activities students reported were computed. Students were then identified as having participated in no activities (reference group), at least one activity, or two or more activities within each of the behavioral categories.

The quantitative component of this study relied on latent growth modeling (LGM) to evaluate and explain change over time in college students’ appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christianity. LGM is a robust method for capturing students’ growth trajectories in longitudinal datasets (Seclosky & Denison, 2018). Such models can estimate the rate of change in an outcome over time. As noted by Seclosky and Denison (2018), LGM is particularly useful in higher education research as its “conceptualization of growth as how individuals change across time and interest in modeling the variables that predict change between as well as change within people allows for a much fuller picture” (p. 388) of students’ college experiences.

The LGM used in this study was constructed within the structural equation modeling (SEM) framework; it was comprised of an observed outcome—appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christians—measured at 3 time points. Within the SEM LGM framework, this longitudinal model includes a latent intercept and latent slope to describe students’ trajectories in the outcome over time (as depicted in Figure 2). As is common in growth modeling, full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation was used to account for missing data (Grimm et al., 2017).

The LGM was first evaluated for overall model fit using standard benchmarks recommended by Hu and Bentler (1999), including small, non-significant chi-square test; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.05; comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.95; and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) < 0.08. Once the model fit was established, growth parameters were interpreted. This included the intercept, or mean baseline of appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christians, as well as the slope, or mean change in appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christians at each timepoint. Significant intercepts and slopes are those significantly different from zero. Thus, a significant slope is an indicator that students experienced a significant amount of change in their appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christians over time.

Following the evaluation of mean growth parameters, the variables comprising the interfaith learning and development framework (Mayhew et al., 2020) were incorporated into the model. Including these as covariates in the model allowed us to examine the extent to which each variable predicted (a) students’ baseline appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christians and/or (b) students’ change in appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christians over time. Most pertinent to the research question were the significant predictors of latent slope, as this study sought to identify and describe institutional conditions and educational practices that lead to growth in students’ appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christians. For all analyses, the outcome variables were standardized based on Time 1 responses, so regression coefficients can be interpreted as change since Time 1 in effect size units.

Once the qualitative focus group data from the subset of 18 institutions were collected and transcribed, teams of trained researchers commenced several analytic stages to identify and code transcripts relevant to students’ development of appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christianity. Recognizing that the IDEALS qualitative dataset is very large, our first decision was to examine only qualitative data segments that had been identified previously as relevant within the guiding frameworks of the study. This helped us thoughtfully reduce extraneous information and focus our analysis. As appreciative attitudes were not a construct of analysis in the original study, our second decision was to create a secondary analysis strategy specific to this study (Ruggiano & Perry, 2019) to examine any previously coded excerpt that included the words “evangelical” or “Christian” for evidence of change in appreciation toward evangelical Christianity. Finally, we explored how non-evangelicals understood evangelicals as people with whom they had things in common and people toward whom they have positive attitudes. This process resulted in a dataset of 463 excerpts from across all transcripts for review. Three themes relevant to change in the appreciation of evangelical Christianity emerged. We now turn to reporting the quantitative results and contextualizing qualitative findings.

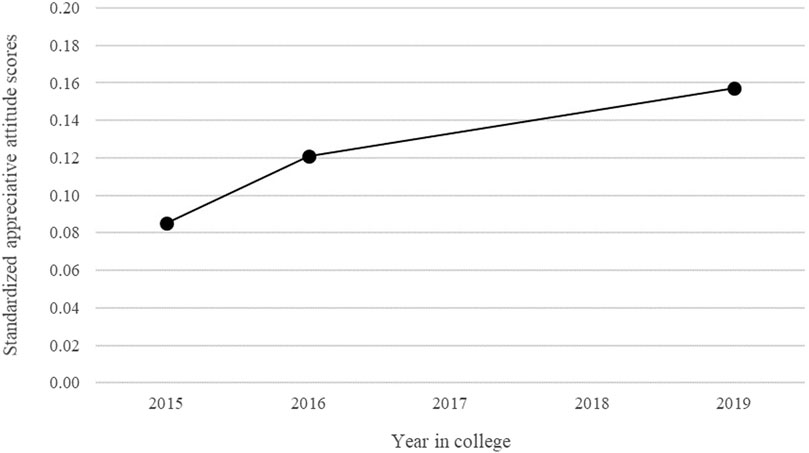

Overall, the latent growth model demonstrated good model fit (χ2 47) = 314.846, p < 0.001; RMSEA [95% CI] = 0.043 [0.039, 0.048]; CFI = 0.921; SRMR = 0.018). The significant chi-square result is to be expected when working with such a large sample size (West et al., 2012), and both RMSEA and SRMR were well within benchmarks of good fit (<0.05 and <0.08, respectively). While the CFI fell slightly below an ideal benchmark (>0.950), it remained acceptable at a close 0.921. Both the mean intercept and slope parameters were positive and significant (intercept = 0.085, p = 0.001; slope = 0.036, p < 0.001). The positive slope indicated that students experienced growth in their appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christians across the 3 time points. This trend is depicted in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3. Growth trajectory for standardized appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christians by timepoint.

The interfaith learning and development framework (Mayhew & Rockenbach, 2021) captures the variables known to influence outcomes such as appreciative attitudes toward people of other worldviews. Those variables include students’ pre-college characteristics (i.e., gender, sexuality, race or ethnicity, parental education), pre-college exposure to interfaith experiences, college experiences (i.e., academic and social behaviors), and environmental factors (i.e., disciplinary, relational, institutional, and national contexts). Each of these variables was examined as a potential predictor of both the latent intercept (i.e., students’ baseline appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christians) and latent slope (i.e., students’ change in appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christians). Significant predictors are reported in Table 3.

Of particular interest in this study were the significant positive predictors of the latent slope, as they are indicative of the experiences and environments that promote positive change in students’ appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christians during their time in college. In particular, one campus climate and one campus culture followed this trend, thereby helping to explain developmental gains in appreciative attitudes toward evangelicals. Compared to their peers at other institutions, students in productive campus climates (e.g., the campus is religiously diverse, the campus is a welcoming place for people of different religious and nonreligious perspectives) reported significantly greater developmental gains over 4 years in college (B = 0.111, p < 0.05), even though their appreciation scores at college entry were significantly lower than their peers (B = −0.115, p < 0.001). A similar trend was noted for students enrolled at institutions that were more likely to appreciate religious and worldview difference: Compared to their peers at other institutions, students enrolled at institutions more likely to appreciate religious and worldview difference reported significantly greater developmental gains over 4 years in college (B = 0.339, p < 0.001), even though their appreciation scores at college entry were significantly lower than their peers (B = -0.075, p < 0.01). Taken together, these findings indicate that evangelical appreciation was not initially linked to an institution’s climate or culture; however, as time went on, the relationship between institutions with productive climates and appreciative cultures was significantly associated with growth in evangelical appreciation through 4 years of college.

Turning to identity characteristics and pre-college behaviors, several results were noteworthy. Pre-college interfaith activities were associated with significantly higher evangelical appreciation when students entered college (B = 0.145, p < 0.001), but were associated with a significantly smaller amount of developmental growth over 4 years (B = −0.124, p < 0.05). The same trend held for white students: When compared to their peers, white students were significantly more likely to report higher appreciation scores upon college entry (B = 0.053, p < 0.05), but reported a significantly smaller amount of growth in those appreciation scores over 4 years of college (B = −0.109, p < 0.05). Taking a slight turn, first-generation college students were not any more likely than their peers to report higher evangelical appreciation at their time of entry, but they were significantly more likely to develop evangelical appreciation during college (B = 0.098, p < 0.05).

Political leaning exerted influence over evangelical appreciation as well. Conservative students reported no significant differences in their evangelical appreciation initially but they did experience significantly more growth in appreciation for evangelicals over 4 years of college (B = 0.160, p < 0.01). Initially, politically-liberal students also reported no significant differences in their evangelical appreciation, as compared to their peers; however, they reported significantly fewer gains in appreciation than their peers over 4 years of college (B = −0.097, p < 0.05). Very politically-liberal students reported significantly lower evangelical appreciation than their peers, both in their college entry scores (B = −0.119, p < 0.001) and in their development over 4 years (B = −0.170, p < 0.01).

Disciplinary contexts also exerted influence on growth in appreciation toward evangelicals. Students in the arts, humanities, or religion were no more likely than their peers to appreciate evangelicals on college entry, but were significantly less likely to report developmental gains over 4 years of college (B = −0.226, p < 0.001).

Relational contexts were also linked to the development of evangelical appreciation during students’ college-going experiences. Specifically, students significantly associated finding space for support and spiritual expression (i.e., “campus is a safe place for me to express my worldview,” “faculty and staff on my campus accommodate my needs with regard to celebrating holidays and other important observances connected to my religious or non-religious worldview,” “there is a place on this campus where I can express my personal worldview,” “my classes are safe places for me to express my worldview”) with evangelical appreciation, both upon college entry (B = 0.085, p < 0.001) and over 4 years (B = 0.112, p < 05). Conversely, students significantly associated more negative interworldview engagements (i.e., “felt silenced from sharing your own experiences with prejudice and discrimination,” “had guarded, cautious interactions,” “had tense, somewhat hostile interactions,” “had hurtful, unresolved interactions”) with lower evangelical appreciation, upon college entry (B = −0.069, p < 0.001) and over 4 years (B = −0.189, p < 01).

Only one interfaith behavior was associated with the development of evangelical appreciation over 4 years of college. When compared to students who participated in no formal academic activities, students who engaged in at least two activities (B = 0.095, p < 0.05) were more likely to develop an appreciation toward evangelicals during college.

Turning to the qualitative analysis, we explored how non-evangelicals understood evangelicals as people with whom they had things in common and people toward whom they have positive attitudes. Notably, sometimes students were clearly discussing interactions with evangelical Christian students, but at other times they referred to Christian students or staff without a clear denominational modifier. Though some of these interactions were not specific to evangelicalism but spoke more broadly to an appreciation of Christianity, we have included them to highlight the ways the college environment offers opportunities for students to develop more appreciative attitudes for Christianity broadly and, at times, evangelicalism in particular. The nuances of the qualitative data showed that students were experiencing both positive and negative interactions with their Christian peers and that their identification of specifically evangelical viewpoints seems to depend on their personal knowledge of evangelical Christianity. When organized for clarity, the stories about changes in appreciation fell into three categories: (a) establishing personal relationships with evangelicals, (b) seeking to understand evangelical viewpoints, and (c) recognizing the Christian privilege of operating from unexamined beliefs.

Throughout the data, students often shared the impact of personal relationships with Christian students on their own meaning making about religion and how those connections impacted their navigation of campus. For example, one student who identified as spiritual and Greek Orthodox shared that while her worldview had not changed much since coming to college at an East Coast private school, she had “grown to respect even more the differences … [and] kind of clung a little bit more toward religion.” She shared the following story:

I even was part of a religious group for a brief period of time. I don’t even know what the religion was, I just know that they were Christian. I stumbled upon the people because I was a new student here, and I didn’t have any friends, and these people were so nice, and I’m still really good friends with them. I’ve noticed and appreciated how religion can tie people together. I’ve met so many people just through that [Christian] group, which is just so funny. I was like a total outsider, but I’m like, “Hey. I wanna learn.”

While this student did not identify this student group as specifically evangelical, she seemed to view its beliefs as different from her own, approached the experience as a learner, and indicated that she has continued to share a social circle with many members of that group.

Other students shared narratives about how new relationships in college helped them make sense of previous experiences with evangelicals and incorporate those views into relationships going forward. For example, one Buddhist student at a private college in the South shared that, as a child, his closest friends were evangelical Christians who frequently asked him to go to church and consider becoming a Christian. He said, “That ended up making me very uncomfortable because I was like, is there something wrong with me? I feel very comfortable in Buddhism, but they’re acting like that’s bad or that’s wrong.” However, he said that in college, he has “found that other people became more accepting of difference and different worldview [s] and more curious as opposed to judgmental.” He explained that his perceptions of one of those previous friendships changed since coming to college:

Something that’s pretty interesting is that one of my evangelical friends from middle school comes here. And I think, we don’t see each other that much now, but I do feel like she’s possibly more open than she was before and I would guess honestly that part of that is just a liberal arts education and the classes that we take and the way that conversations happen in those classes.

In this anecdote, the student seemed to understand the changes in his own and his evangelical friend’s openness and acceptance as a byproduct of the college environment, and this shared developmental trajectory improved his appreciation of his friend, despite a difficult history.

Students also seemed to appreciate Christianity and evangelicals to a greater degree when they had opportunities to learn about the differences in religious beliefs and perspectives within evangelicalism. The stories students relayed often featured an opinion or impression formed before entering college and then a transition point during college. An agnostic student at a private institution in the South shared how initial interactions with an interfaith staff member influenced her perceptions of Christianity:

I’ve always been pretty accepting of a lot of faiths, but in particular the way I grew up, I experienced a lot of toxic Christianity … my mom’s parents, whenever we went to their house, we had to go to church and it was a Southern Baptist Church. The message was really, really conservative all the time. The few times that my parents even tried to find us a church, we’d go for a couple of weeks and then all of a sudden there would be a sermon like “Gays are horrible. Being gay is really bad,” and I’d be like, “I cannot be here. We have to go,” like, “This is really bad.” Coming here, especially one of the first people that I met at the [Interfaith] Center was our associate chaplain … and he’s a really progressive Christian. A lot of people I’ve met [here] are the more progressive Christians. I don’t know. I guess I just kind of associated Christianity with all the bad views and it was just nice to find Christians with good views here.

This student’s story highlights how pre-college experiences might prime students to view evangelical Christianity as associated with specific, undesirable viewpoints. However, the college environment might provide different examples of Christian ways of being that challenge these previous experiences and open the door for continued learning about Christianity as a religion and Christians as individuals. In this case, the student decided to pursue understanding religious differences formally by becoming a religious studies major and an active interfaith organizer on her campus.

At a religiously affiliated school near the Great Lakes, another student spoke specifically about evangelicals but referred more broadly to the way in which college environments inspire greater compassion toward others. She identified as Christian but not evangelical, and embedded in her story is how the ability to nuance viewpoints through discussion has changed her capacity for appreciation:

One side of my family is conservative evangelical Christians … I actually did grow up, in my early years, as an evangelical Christian. I considered believer’s baptism and stuff like that. But that's not really what the foundation of my faith is now, I guess. From going to college, throughout the last few years, I think I’ve gained a little bit more empathy for my conservative family members. Definitely still don’t agree with them, but I think that when you’re going at discussions with people who you disagree with, you have to assume that the other side has good intentions. Otherwise, the conversation just spirals.

An atheist student at a private school in the Southwest, who also identified as a former evangelical, conveyed similar compassion. As she pursued her major in evolutionary biology during college, she came to understand herself as an atheist, and her own story has informed how she views evangelicals:

I know that I probably believed the same things they did at some point and would have never changed my belief system [if someone hadn’t] challenged it. I think that a lot of people look at evangelicals and think that they can never change but that's not always the case. Sometimes planting doubt is good even if they don’t change right away. Because you have to understand that they most likely grew up their whole lives being told from the time they were young that this belief is the only way and it’s right and that everyone else is going to be tortured forever. A lot of times even though they seem bigoted they’re saying these things because they think that if you don't believe what they believe that you’re going to suffer forever and they truly care about you.

These two stories showcase how these students’ ability to engage with the evangelical Christians in their lives, productively and as part of their development during college, may have positively shifted their appreciation of evangelicals. Interestingly, both students were former evangelicals. Their personal worldview identifications underscore the nuance that those who identify as non-evangelical may have, at one point, identified within that group, which should inspire us to consider how growth in appreciation of evangelicals may differ for former evangelicals and never-evangelical Christians.

The stories represented in this final theme were not specifically about evangelical Christian students, but instead represented some aspect of Christian privilege that non-evangelicals understood was not available to them on campus. These stories further illuminate how, to a non-evangelical audience, evangelical students are firmly situated within the privileged group that benefits from the foundationally Christian ethos of U.S. college campuses.

In our data, student stories seemed to indicate that Christian students might not need to closely examine how their religious beliefs affect their experience on campus because they align with the campus norm. Poignantly, a Muslim student at a religiously-affiliated college near the Great Lakes said, “A lot of the students are Christian and are white, … [so although] most of them are open-minded and stuff … they don’t go out of their way to ask questions so that they can learn more.” She also shared she feels very comfortable expressing her worldview in certain settings, like interfaith programs, but she was more likely to stay quiet and not share if the conversation turned to religion in the context of a study group.

A different form of Christian privilege was illuminated by a Jewish student enrolled at a private university on the East Coast who realized, “A lot of people, who would identify as completely non-religious, would be like, ‘My parents are atheists, I’m an atheist, I have no connection to any religious background’, are often passably Christian.” These non-Christian students would operate as if everyone had the same background, and would “be shocked when [they discovered that,] actually, that’s not [her] lived experience at all.” When asked for a specific example, she shared a story about a student on her residence hall floor who put Christmas trees on all the doors, which within her religion she understood as a problem because “it is a huge sin to celebrate Christmas, essentially, in Judaism, because it is considered worshiping false idols … I really don’t want a Christmas tree put on my door.” Although she was not specifically upset with the other student’s intentions, she did see it as an issue that the secular and Christian lens usually employed on campus as an issue because there was little recognition that this action could be upsetting for religious reasons.

Notably, both stories were from students who self-identified as members of minoritized religions and who pointed to the broader presence of Christian privilege, rather than specifically the evangelical sector of Christianity, as a component of their campus experiences. It seems reasonable that non-evangelical students, who are not recipients of these Christian privileges afforded to those either religiously or culturally Christian, may be less inclined to develop their appreciation of evangelical students.

Our study was limited in several ways. First, the sample was biased toward students who responded to surveys, were more motivated by incentives, were enrolled at 4-years colleges, or may have been more invested in the topic of religion. Second, the interviews and focus groups we conducted were not specifically designed for the purpose of capturing in-depth information about a person’s religion or worldview narrative but were intended to understand how college experiences shape attitudes toward religious, secular, and spiritual diversity. For example, definitions of evangelicalism were not provided or discussed with students. Rather, students either self-identified as evangelicals or referred to evangelical Christianity without an explicit definition. Finally, the qualitative data analysis did not allow us to probe deeper into the intersections of religion with other identities (e.g., evangelical Christianity and whiteness), which curtailed our ability to explore these identity dynamics. Thus, the results should be considered with these limitations in mind.

Developing evangelical appreciation within academic spaces is complicated, especially as national right-leaning leaders politicize college-going for its liberalizing effects on students and left-leaning educators express prejudices about evangelical Christianity (Rosik & Smith, 2009; Kreighbaum, 2019). Results from this study provide compelling evidence that appreciation of evangelical Christianity can and does occur over 4 years of college through a mosaic of experiences. When students were provided opportunities to connect with evangelicals through a variety of touchpoints on campus—both curricular and co-curricular—the resulting relationships prompted greater understanding of and empathy toward evangelicals and in some cases softened previously negative attitudes against them (see Rockenbach et al., 2019; Ragins & Ehrhardt. 2020). This mixed-methods study showcases the immense power that lies in college-going: to see evangelicals differently, to appreciate their contributions to society, and to find commonalities with them, despite the potential presence of deep disagreements.

Findings from this study centered relationship as the primary means for helping students develop an appreciation for evangelical Christianity. In conversation with each other, the quantitative and qualitative findings suggest that the relationships students shared with each other offered them opportunities to make meaning of, or resolve, tensions over and about evangelical Christianity. The negative encounters we observed as detrimental for appreciation development—those that were silencing, guarded, tense, somewhat hostile, hurtful, and unresolved—were balanced against the words “empathy” and “good intentions,” which students used to underscore stories of the relationships they discussed as helpful for appreciating evangelical Christians. The need for empathy becomes increasingly important in the context of evangelical Christianity, given the potential coercive exchanges research has documented (see Shaheen et al., 2022) and students also discussed when engaging specifically with evangelicals. Adding dimensions to findings from previous research that established the importance of relationship mattering in student life (see Hudson, 2018; Hudson, 2020), our study offers relationship empathy as a distinctive epistemic mechanism for offsetting the fear of coercion with the opportunity for understanding.

Four-year gains in evangelical appreciation occur red most often for students who enrolled in campuses committed to inclusion and belongingness practices for all religions, secularities, and spiritualities. Public or private, large or small, selective or not, institutions that provided students with opportunities to express their religious beliefs freely and openly spurred growth in positive attitudes toward evangelicals. Participants named the “center” and the “classroom” as particular spaces and places they encountered for these moments, although we are certain there are others as well.

These results echo those from studies that examined similar dimensions of worldview development, including those associated with growth in appreciation for minoritized faith and non-faith-based identities (see Bowman et al., 2017; Mayhew et al., 2017; Rockenbach et al., 2017). Indeed, restricting religious expression (Rockenbach et al., 2017; Rockenbach et al., 2018), dismissing religious conversation as anti-intellectual (Marsden & Longfield, 1992), ignoring the spiritual struggles students often encounter in college (Pargament, 1997), and leaving spiritual support only to off-campus communities like churches and parachurch organizations (Mayhew et al., 2017) compromise the health and well-being of all students. To support appreciation of evangelical Christianity, students must feel like all worldview identities are welcomed and supported in educational contexts where physical spaces are distinctively provided for the free expression and exchange of religious ideas and supportive places designed for students to explore identity nuance.

Given the complexities of these issues, it is unsurprising that our results suggested at least two formal academic experiences were needed to motivate students' appreciation for evangelical Christians, developing appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christianity over 4 years in college was related to students' participation in at least two of the following formal academic activities: a) enrolling in a religion course on campus specifically designed to enhance your knowledge of different religious traditions; b) enrolling in a course on campus specifically designed to discuss interfaith engagement; c) discussing shared values between religious and non-religious traditions in one of your courses; d) discussing religious diversity in at least one elective course; e) discussing religious diversity in at least one general education course; f) brainstorming a solution to a societal issue by working with students from other religious or non-religious perspectives; g) using a case study as a way to examine religious and non-religious diversity in the world; h) participating in contemplative practices (e.g., meditation, prayer, moment of silence) in the classroom; i) discussing interfaith cooperation in at least one course; j) visiting a religious space off campus as part of a class; k) discussing religious or spiritual topics with faculty; l) discussing their personal worldview in class; m) reflecting on their own worldview in relationship to another religious or non-religious perspective as part of a class; n) discussing other students’ religious or non-religious perspectives in class; o) pursuing a minor or concentration in interfaith studies; p) reflecting on why interfaith cooperation is relevant to their field of study; q) developing a deeper skillset to interact with people of diverse religious and non-religious perspectives; and r) participating in an internship that encouraged using interfaith skills.

Consistent with the pragmatic epistemologies higher education scholars appropriate for their work, the results urge educators to provide students with opportunities to grow in their appreciation, compassion, and empathy for those peers with whom they deeply disagree, and especially at least twice in formal academic environments this study suggests.

What should the curricula driving these formal academic efforts underscore in the context of helping students develop appreciation for evangelical Christianity? In line with Eck’s (2006) vision for principled religious pluralism, it is insufficient that educators attempt to quell or circumvent challenging exchanges across worldview differences by promoting a polite tolerance or manufacturing false unity. In today's tumultuous social and political climate, more is needed to bring healing to the fractures that threaten well-being on our campuses and in our societies. Findings from this mixed-methods study echo and extend those from previous efforts. Not only are evangelical students not a religious monolith (see Riggers-Piel et al., 2021; Small, 2020), they also are not described monolithically, with students using words like “progressive,” “conservative,” “open-minded,” and “curious” to describe exchanges with Christian peers. As such, evangelical students have an opportunity to reframe their narrative based on the nuanced ways they approach and express their faith. Prioritizing a humble awareness of, and active ways to disrupt, the hegemony their Christian privilege carries may help evangelical students face some of the challenges with feeling muted by, and needing to conceal their perspectives on, some university settings. This approach may help non-evangelical students curate the empathy needed for making meaning of evangelical Christianity and developing relationships with their evangelical peers. Educators must first understand the ways in which their campuses are operating from a foundationally Christian heuristic, teach students how to identify and critically examine Christian privilege, and then address and disrupt the effects of Christian privilege while supporting the spiritual expression of evangelical students. With the support of educators, students can evolve from tolerance to appreciation for the ethical and societal contributions of their evangelical peers.

Developing appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christianity is axiologically sensitive. Critical scholars may scrutinize whether students should develop this sensibility, especially for evangelicals, as research has routinely documented the stronghold Christian privilege and its expressions (e.g., calendar, holiday) maintain on college campuses. Alternatively, some taxpayers may question whether developing appreciative attitudes toward evangelicals is important at all, given the misunderstandings about the separation of church and state. In tandem, there are other U.S. constituents who question whether higher education should spur appreciation toward anything conservative, including appreciative attitudes toward evangelical Christianity.

Our position centers social cooperation as the means for addressing the perpetual divisions that continue to characterize our democracy. If we can lead with empathy as a means for engaging with each other, like the student participants in this study, we can begin to appreciate each other’s complexities. In doing so, we can begin healing and reducing the ubiquitous extremism our contemporary society seemingly embraces.

Of critical importance, this study clearly provides evidence that 4-year growth in evangelical appreciation does occur, and points to practices educators can enact to spur its development. Rather than leave these practices to chance, to churches students attend, or to parachurch organizations with an active presence on college campuses, college administrators and faculty can make a difference in the lives of students by providing them with at least two formal academic activities to spur growth in evangelical appreciation. Educators should design these activities in contexts suitable for productive exchange with evangelicals and the ideas underscoring evangelical Christianity: Formal curricular activities intended to disrupt Christian and evangelical hegemony, without demonizing its privileged beneficiaries, should present challenging messages with the empathy students need to see, hear, and relate to each other. In tandem, educators must be aware of, and address openly, the pain often incurred by these conversations, especially among religiously-minoritized students. Findings like these express the pragmatic value higher education scholars place on research designed to inform practice. In the context of growth in positive attitudes toward evangelical Christianity, this study offers educators direction for moving forward.

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The Ohio State University and North Carolina State University Institutional Review Boards. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

The Interfaith Diversity Experiences and Attitudes Longitudinal Survey (IDEALS) research is made possible by funders including The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Fetzer Institute, and the Julian Grace Foundation.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1In this study, we use the term “worldview” to refer to a guiding life philosophy, which may be based on a particular religious tradition, spiritual orientation, nonreligious perspective, or some combination of these (see Mayhew et al., 2016).

Bailey, S. P. (2016). White evangelicals voted overwhelmingly for Donald Trump, exit polls show. Washington US: The Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/acts-of-faith/wp/2016/11/09/exit-polls-show-white-evangelicals-voted-overwhelmingly-for-donald-trump/.

Bielo, J. S. (2011). Emerging evangelicals: Faith, modernity, and the desire for authenticity. New York, United States: NYU Press.

Bowman, N. A., Rockenbach, A. N., Mayhew, M. J., Riggers-Piehl, T. A., and Hudson, T. D. (2017). College students’ appreciative attitudes toward atheists. Res. High. Educ. 58 (7), 98–118. doi:10.1007/s11162-016-9417-z

Bowman, N. A., and Small, J. L. (2010). Do college students who identify with a privileged religion experience greater spiritual development? Exploring individual and institutional dynamics. Res. High. Educ. 51 (7), 595–614. doi:10.1007/s11162-010-9175-2

Brow, M. V., Jenny, Y., Ying, H. J., and Bonner, P. (2014). Christians in higher education: Investigating the perceptions of intellectual diversity among evangelical undergraduates at elite public universities in southern California. J. Res. Christian Educ. 23 (2), 187–209. doi:10.1080/10656219.2014.901932

Bryant, A. N. (2005). Evangelicals on campus: An exploration of culture, faith, and college life. Relig. Educ. 32 (2), 1–30. doi:10.1080/15507394.2005.10012355

Bryant, A. N. (2008). The developmental pathways of evangelical Christian students. Relig. Educ. 35 (2), 1–26. doi:10.1080/15507394.2008.10012417

Bryant, A. N. (2011). The impact of campus context, college encounters, and religious/spiritual struggle on ecumenical worldview development. Res. High. Educ. 52 (5), 441–459. doi:10.1007/s11162-010-9205-0

Creswell, J. W., and Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, United States: Sage Publications.

Eck, D. L. (2006). Prospects for pluralism: Voice and vision in the study of religion. J. Am. Acad. Relig. 75, 743–776. doi:10.1093/jaarel/lfm061

Foubert, J. D., Watson, A., Brosi, M., and Fuqua, D. (2012). Explaining the wind: How self-identified born again Christians define what born again means to them. J. Psychol. Christianity 31 (3), 215–227.

Grimm, K. J., Ram, N., and Estabrook, R. (2017). Growth modeling: Structural equation and multilevel modeling approaches. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Hammond, P. E., and Hunter, J. D. (1984). On maintaining plausibility: The worldview of evangelical college students. J. Sci. Study Relig. 23, 221–238. doi:10.2307/1386038

Hu, L., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 6 (1), 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

Hudson, T. D. (2020). Interpersonalizing cultural difference: A grounded theory of the process of interracial friendship development and sustainment among college students. J. Divers. High. Educ. 15 (3), 267–287. Advance online publication. Available at: https://doi-org.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/10.1037/dhe0000287.

Hudson, T. D. (2018). Random roommates: Supporting our students in developing friendships across difference. About Campus. 23 (3), 13–22. doi:10.1177/1086482218804252

Jones, B. P. (2018). White evangelical support for Donald Trump at all-time high. Washington, D.C.: Public Religion Research Institute. Available at: https://www.prri.org/spotlight/white-evangelical-support-for-donald-trump-at-all-time-high/.

Kreighbaum, A. (2019). Persistent partisan breakdown on higher Ed. Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2019/08/20/majority-republicans-have-negative-view-higher-ed-pew-finds.

Lancaster, S. L., Larson, M., and Frederickson, J. (2019). The many faces of evangelicalism: Identifying subgroups using latent class analysis. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 13 (4), 493–502. doi:10.1037/rel0000288

Magolda, P., and Ebben Gross, K. (2009). It’s all about Jesus! Faith as an oppositional subculture. VA: Stylus: Sterling.

Markofski, W. (2015). The public sociology of religion. Sociol. Relig. 76 (4), srv042–475. doi:10.1093/socrel/srv042

Marsden G. M., and Longfield B. J. (Editors) (1992). The Secularization of the academy (Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press).

Mayhew, M. J., Bowman, N. A., Rockenbach, A. N., Selznick, B., and Riggers-Piehl, T. (2018). Appreciative attitudes toward Jews among non-Jewish US college students. J. Coll. Student Dev. 59 (1), 71–89. doi:10.1353/csd.2018.0005

Mayhew, M. J., Rockenbach, A. B., Seifert, T. A., Bowman, N. A., and Wolniak, G. C. (2016). How college affects students: 21st century evidence that higher education works. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mayhew, M. J., Rockenbach, A. N., Bowman, N. A., Lo, M. A., Starke, M., Riggers-Piehl, T., et al. (2017). Expanding perspectives on evangelicalism: How non-evangelical students appreciate evangelical Christianity. Rev. Relig. Res. 59 (2), 207–230. doi:10.1007/s13644-017-0283-8

Mayhew, M. J., Rockenbach, A. N., and Dahl, L. S. (2020). Owning faith: First-year college-going and the development of students’ self-authored worldview commitments. J. High. Educ. 91, 977–1002. doi:10.1080/00221546.2020.1732175

Mayhew, M. J., and Rockenbach, A. N. (2021). Interfaith learning and development. J. Coll. Character 22 (1), 1–12. doi:10.1080/2194587x.2020.1860778

Mayhew, M. J., and Simonoff, J. S. (2015). Non-White, no more: Effect coding as an alternative to dummy coding with implications for higher education researchers. J. Coll. Student Dev. 56 (2), 170–175. doi:10.1353/csd.2015.0019

Moran, C. D., Lang, D. J., and Oliver, J. (2007). Cultural incongruity and social status ambiguity: The experiences of evangelical Christian student leaders at two midwestern public universities. J. Coll. Student Dev. 48 (1), 23–38. doi:10.1353/csd.2007.0004

National Association of Evangelicals (1971). What is an evangelical? Washington, D.C., United States: National Association of Evangelicals. Available at: http://nae.net/what-is-an-evangelical/.

Pally, M. (2011). The new evangelicals: Expanding the vision of the common good. Cambridge: William B. Eerdmans Publishing.

Paredes-Collins, K., and Collins, C. S. (2011). The intersection of race and spirituality: Underrepresented students' spiritual development at predominantly white evangelical colleges. J. Res. Christian Educ. 20 (1), 73–100. doi:10.1080/10656219.2011.557586

Pargament, K. I. (1997). The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, practice. New York, United States: Guilford Press.

Pew Research Center (2017). Americans express increasingly warm feelings toward religious groups. https://www.pewforum.org/2017/02/15/americans-express-increasingly-warm-feelings-toward-religious-groups/.

Patel, E., and Meyer, C. (2011). The civic relevance for interfaith cooperation for colleges and universities. J. College Character 12 (1), 1–9. doi:10.2202/1940-1639.1764

Ragins, B., and Ehrhardt, K. (2020). Gaining perspective: The impact of close cross-race friendships on diversity training and education. J. Appl. Psychol. 106 (6), 856–881. doi:10.1037/apl0000807

Religion News Service (RNS) (2020). An open letter from black church leaders and allies to Christianity Today. Washington, DC: Religion News Service. https://religionnews.com/2020/01/10/an-open-letter-from-black-church-leaders-to-christianity-today/.

Riggers-Piehl, T. A., Dahl, L. S., Staples, B. S., Selznick, B. S., Mayhew, M. J., and Rockenbach, A. N. (2022). Being evangelical is complicated: How students’ identities and experiences moderate their perceptions of campus climate. Rev. Relig. Res. 64, 199–224. doi:10.1007/s13644-021-00472-z

Rockenbach, A. N., Hudson, T. D., Mayhew, M. J., Correia-Harker, B. P., Morin, S., and Associates, (2019). Friendships matter: The role of peer relationships in interfaith learning and development. Chicago, IL: Interfaith Youth Core.

Rockenbach, A. N., Mayhew, M. J., Bowman, N. A., Morin, S. M., and Riggers-Piehl, T. (2017). An examination of non-Muslim college students’ attitudes toward Muslims. J. High. Educ. 88 (4), 479–504. doi:10.1080/00221546.2016.1272329

Rockenbach, A. N., Mayhew, M. J., Correia-Harker, B. P., Morin, S., Dahl, L., and Associates, (2018). Best practices for interfaith learning and development in the first year of college. Chicago, IL: Interfaith Youth Core.

Rosik, C. H., and Smith, L. L. (2009). Perceptions of religiously based discrimination among Christian students in secular and Christian University settings. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 1 (4), 207–217. doi:10.1037/a0017076

Ruggiano, N., and Perry, T. E. (2019). Conducting secondary analysis of qualitative data: Should we, can we, and how? Qual. Soc. Work 18 (1), 81–97. doi:10.1177/1473325017700701

Seclosky C., and Denison D. B. (Editors) (2018). Handbook on measurement, assessment, and evaluation in higher education. 2nd ed. (Milton Park, Abingdon-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, England, UK: Routledge).

Seifert, T. A. (2007). Understanding Christian privilege: Managing the tensions of spiritual plurality. About Campus. 10–17, 10–17. doi:10.1002/abc.206

Shaheen, M., Mayhew, M. J., and Rockenbach, A. N. (2022). Religious coercion on public University campuses: Looking beyond the street preacher. J. Coll. Student Dev. 63 (1), 69–84. doi:10.1353/csd.2022.0007

Small, J. L. (2020). Critical religious pluralism in higher education: A social justice framework to support religious diversity. Milton Park, Abingdon-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, England, UK: Routledge.

Smidt, C. (2007). “Evangelical and mainline protestants at the turn of the millennium,” in From pews to polling places: Faith and politics in the American religious mosaic. Editor J. M. Wilson (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press), 29–51.

Smith, C. (2000). Christian America? What evangelicals really want. (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press).

Weber, J. (2018). Billy Graham center explains survey on evangelical Trump voters. Carol Stream, Illinois: Christianity Today. https://www.christianitytoday.com/news/2018/october/evangelicals-trump-2016-election-billy-graham-center-survey.html.

Weber, J. (2017). Evangelical vs. Born again: A survey of what Americans say and believe beyond politics. Carol Stream, Illinois: Christianity Today. Available at: https://www.christianitytoday.com.

West, S. G., Taylor, A. B., and Wu, W. (2012). “Model fit and model selection in structural equation modeling,” in Handbook of structural equation modeling. Editor R. H. Hoyle (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 209–231.

Keywords: appreciative attitudes, evangelical Christian, worldview diversity, interfaith diversity, higher education

Citation: Mayhew MJ, Winkler CE, Staples BA, Singer K, Shaheen M and Rockenbach AN (2022) The Evangelical Puzzle Partially Explained: Privileged Prejudice and the Development of Appreciative Attitudes Toward Evangelical Christianity. Front. Educ. 6:775303. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.775303

Received: 13 September 2021; Accepted: 06 December 2021;

Published: 30 September 2022.

Edited by:

Mona Hmoud AlSheikh, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Saudi ArabiaReviewed by:

T. Peele-Eady, University of New Mexico, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Mayhew, Winkler, Staples, Singer, Shaheen and Rockenbach. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Matthew J. Mayhew, bWF5aGV3LjY1QG9zdS5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.