- 1School of Textiles and Fashion, Shanghai University of Engineering Science, Shanghai, China

- 2College of Art and Design, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China

- 3Department of Global Business Graduate School, Kyonggi University, Suwon, South Korea

The global pandemic of COVID-19 is a challenge for entrepreneurship education in universities and various organizations. Although positive responses to overcome the challenges of COVID-19 are being made, entrepreneurship strategies and policies might not meet students’ requirements. In order to enrich education management research, the main aim of this study is to provide a conceptual model and examine the relationship between perceptions, perceived positive attitudes on entrepreneurship education, and entrepreneurial intention (EI) during the COVID-19 crisis. The model is tested by using data from universities that are located in Shanghai, P.R. China. The study reveals that 1) perceived social norms and perceived self-efficacy positively influence perceived positive attitudes in entrepreneurship education; 2) there is no relationship between perceived entrepreneurial barriers and perceived positive attitudes in entrepreneurship education; 3) perceived positive attitudes in entrepreneurship education positively influence EI. The findings contribute to university and government policies on the development of entrepreneurial education. The framework of this study provides insight into the influential factors of entrepreneurship education that contribute to theoretical studies in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, there are some limitations and restrictions in university education that have resulted in teaching methods being changed to online teaching (Ratten, 2020), which may affect entrepreneurship education. Before there are several findings that prove the positive impact of students’ intention towards entrepreneurship education; their willingness to engage in entrepreneurial activities and their employment performance (Graevenitz et al., 2010; Li and Liu, 2011; Souitaris et al., 2007; Tkachev and Kolvereid, 1999). Furthermore, entrepreneurship education has been studied by students, who are encouraged to consider their future directions and career goals (Ratten and Jones, 2018; Ratten and Jones, 2020). Entrepreneurship education is especially related to innovative thinking, which can empower students’ EI (Oosterbeek et al., 2010; Ratten and Jones, 2020). Especially, entrepreneurship education teaches skills for business management and for the future directions of university students (Mentoor and Friedrich, 2007). In universities, the effectiveness of entrepreneurial education is improved by entrepreneurial competencies, the reduction of entrepreneurial barriers and the change of EI (Liu et al., 2021). However, the COVID-19 pandemic has become a crisis for people’s daily life (Ruiz-Rosa et al., 2020), students may not perceive a qualified career in education. It is also difficult to evaluation their perceptions as the influential factors have not been studied sufficiently during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although, the perception of entrepreneurship education has been measured through various perspectives, still more research is required during this time of COVID-19 pandemic. The perception of entrepreneurship education has been explored through various factors, such as perceived self-efficacy, perceived desirability, desire for achievement and fear of failure (Farashah, 2013; Peterman and Kennedy, 2003; Shrivastava and Acharya, 2020). Even qualitative and quantitative methods are adopted in the exploration of factors (Blenker et al., 2014), studies on the perception of entrepreneurship education in the time of COVID-19 are inadequate.

As the stress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has a psychological influence on education (Roman and Plopeanu, 2021), the perceptions of entrepreneurship education should be explored in the context of the health crisis. The way to confront the social crisis and address students’ perception of entrepreneurship education has been overlooked in previous studies. This breach is mainly due to the neglect of validity in the international health crisis (namely, COVID-19) and its effects on university students’ EI. Current literature lacks studies that focus on perceptions during the COVID-19 pandemic and among other factors, exploring students’ perceptions is vital for improving entrepreneurship education and achieving its goals. Additionally, there have been insufficient studies on a perception-intention model for use under the influence of crisis. Due to the uncertainty of the effects of COVID-19 on entrepreneurship, there may have some changes on university students’ entrepreneurial activity (Meahjohn and Persad, 2020). Some limited studies have been published that tend towards qualitative research; however, there is still a need for credible research with the support of quantitative analysis (Lin and Xu, 2017).

The above mentioned gaps provide an opportunity for this research. This study proposed a perception-intention model for measuring the perception of entrepreneurship education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, we not only focus on the contents and approaches of entrepreneurship education alone, but also explore the quality in university students’ perceptions and attitudes. The objectives of this study are as follows: 1) to identify a conceptual model that discovers and emphasizes university students’ perception on entrepreneurship education during COVID-19; 2) to explore and identify attitudes towards entrepreneurship education that may have strong effects on university students’ EI during COVID-19; 3) to address the implications of this study for future research on entrepreneurship education; 4) identify the relationship of the views of university students. We also aim to contribute to literature by exploring the effect of students’ perception created by the COVID-19 pandemic on entrepreneurial intention. The paper contains five sections. In the following section, we review the literature on entrepreneurship education, perceived self-efficacy, perceived social norms, perceived entrepreneurial barriers, perceived positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship education, and EI and we propose a research model. The Methods and Results are method and results. In Discussion and Conclusion, we present discussion and conclusion.

Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

Perceived Positive Attitudes Towards Entrepreneurship Education

Students’ entrepreneurial abilities have been influenced by entrepreneurship education (Beynon, et al., 2016). Many researchers studied entrepreneurship education that mainly focused on assessing entrepreneurship education courses (Pittaway and Edwards, 2012; Gerba, 2012), learning models on entrepreneurship education courses (Graevenitz et al., 2010) and proposing theoretical models of entrepreneurship and emotions (Jones and Underwood, 2017). As an example, Abou-Warda (2016) supported by qualitative and quantitative research approaches, developed the framework of technology-based entrepreneurship education from the following three aspects: centres for innovation and entrepreneurship, technology entrepreneurship professors/education, and technology entrepreneurship programmes/courses. Additionally, after systematically reviewing the methods in entrepreneurship education research, Blenker et al. (2014) identified five levels in entrepreneurship education activities, namely, regional and national levels, institutional level, programme level, course level and student and teacher level (see a review). From the above literature, it can be found that researchers studied entrepreneurship education from various viewpoints (e.g., courses and activities). Attitude is the extent to which an individual forms positive or negative opinion on becoming an entrepreneur (Farashah, 2013). Attitude is important for changing or enhancing individuals’ intentions and behaviour. Students’ attitudes to entrepreneurship can be developed, based on their opinions to education (Harris and Gibson, 2008; Souitaris et al., 2007). In order to enrich policy in entrepreneurship education, researchers investigating the attitudes and motivation of female students towards entrepreneurship revealed that clear goals should be set for entrepreneurship education (Sowmya et al., 2010). Thus, we defined perceived positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship education as the perception on entrepreneurship training and courses during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Perceived Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy is a social-cognitive process that can be adopted to explain a person’s attitude, intention, performance, and behaviour towards entrepreneurship (Wardana et al., 2020). Self-efficacy can be described as a person’s confidence in their performance and abilities to be successful (Puni et al., 2018). Perceived self-efficacy is a measurement of individuals’ abilities and skills that can indicate their beliefs and intentions on how they want to perform and achieve (Shrivastava and Acharya, 2020). Perceived self-efficacy has been adopted as a predictor to intentions and performance that enhance EI (Boyd and Vozikis, 1994; Chen et al., 1998). In this study, perceived self-efficacy is defined as university students’ confidence on entrepreneurial abilities and performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, we hypothesized that:

H1. Perceived self-efficacy (PS) positively influences perceived positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship education (PPAEE) during COVID-19.

Perceived Social Norms

Social norms are defined as informal rules that are not written; however, they might influence individual perceptions (Elster, 1989). Social norms refer to the perceptions of a person who could be influenced from surrounding people, such as friends, family members and important persons (Liñán, 2008). Especially, individuals in society belong to social groups. Some people may prefer to follow social norms, while others may be annoyed by perceived social norms (Iyer et al., 2007). After analysing 170 questionnaires from students in Quaid-i-Azam University, Yousaf et al. (2015) found that when compared to students’ skills and capabilities, subjective norms have a significant effect in improving their intentions to be entrepreneurs. Thus, perceived social norms can be defined as the extent of university students’ care about opinions from friends, family, teachers, and the person who is important to them. The hypothesis is proposed as follows:

H2. Perceived social norms (PSN) positively influence PPAEE during COVID-19.

Perceived Entrepreneurial Barriers

Researchers examined the barriers in entrepreneurship that were affected by intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic factors include personal skills, characteristics and abilities (Ibrahim and Goodwin, 1986). Extrinsic factors are those that are out of an entrepreneur’s control, including government regulations and taxes (Theng and Boon, 1996). Stamboulis and Barlas (2014) concluded that there are three categories of entrepreneurial barriers, namely, individual barriers (family and education), organizational barriers (financing, physical resources and marketing) and environmental barriers (socio-cultural factors and rules and regulations). Giacomin et al. (2011) found there were differences in barrier perceptions among students from America, China, India, Belgium and Spain. They found that compared to American, Belgian and Indian students, Chinese and Spanish students rated perceived risk as a less important barrier in entrepreneurship. They also proved that lack of initial capital is the main barrier to starting businesses. Some barriers may have negative effects on EI that should be considered in entrepreneurship education (Shahverdi et al., 2018). Perceived entrepreneurial barriers is defined as university students’ difficulties in entrepreneurship during the COVID-19 pandemic, including lack of initial capital, experience, ideas, and formal help. Hence, we hypothesized that:

H3. Perceived entrepreneurial barriers (PEB) negatively influence PPAEE during COVID-19.

Entrepreneurial Intention

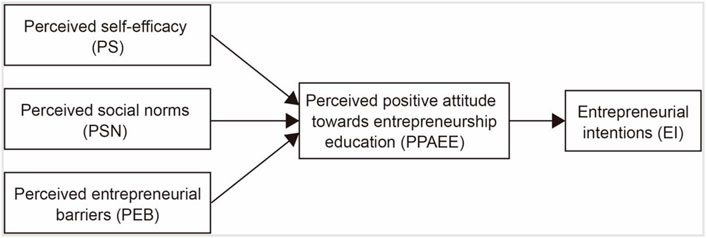

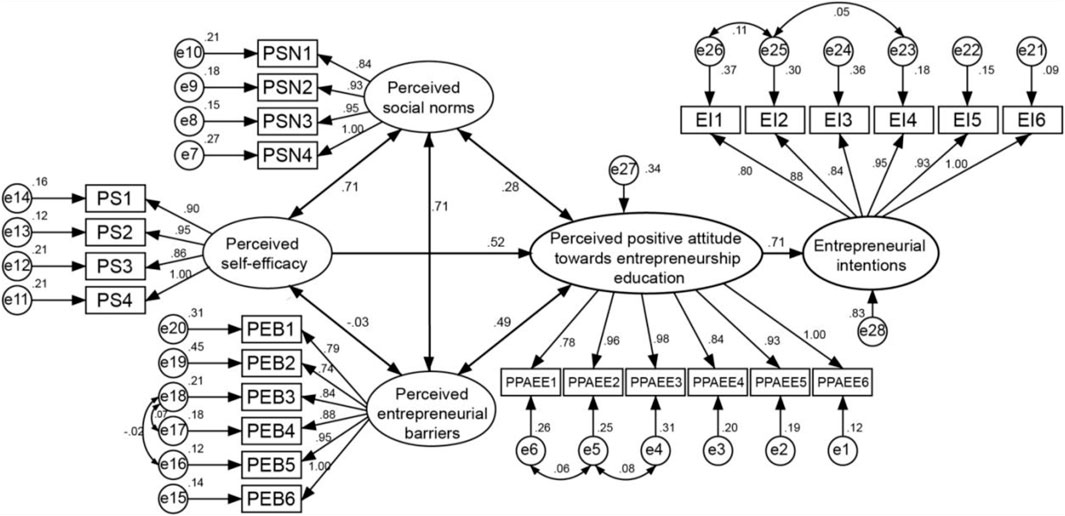

The theory of planned behaviour (TPB) is based on an individual’s rational choice and intention that may predict a certain behaviour (Küttim et al., 2014). Attitudes towards behaviour, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control can be adopted to predict intentions to perform behaviours (Ajzen, 1991). This theory has been applied in the studies of entrepreneurship, such as the effect of entrepreneurship education and EI (Shrivastava and Acharya, 2020). Furthermore, intention is a predictor of behaviour and action, such as a self-plan to become an entrepreneur or to start entrepreneurship activities in the future (Lent et al., 1994; Souitaris et al., 2007; Shrivastava and Acharya, 2020). Thus, TPB can be conducted to analyse intentions in an entrepreneurship setting. The conceptual framework of this study is presented in Figure 1.

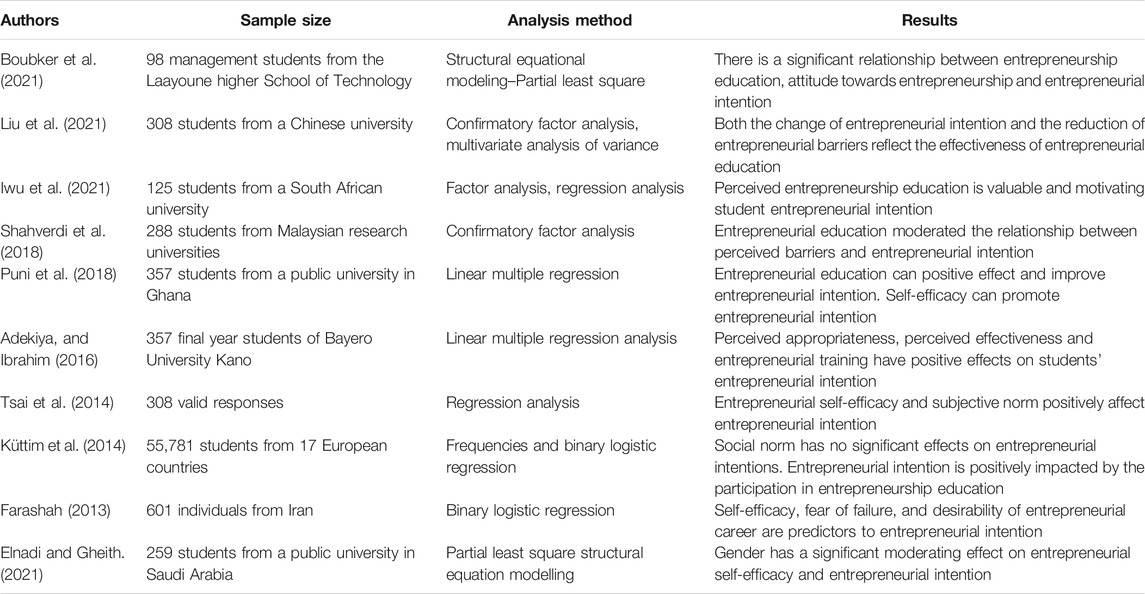

Nabi et al. (2010) defined entrepreneurial intention as individual awareness that he/she plans to set up a new business in the future. It also means that a person wants to develop entrepreneurship activities (Mohamad et al., 2015; Souitaris et al., 2007). Several researchers found that there is a significant correlation between entrepreneurial education and EI (Harima, et al., 2021; Peterman and Kennedy, 2003). Students’ EI had increased since they had received entrepreneurship education (Sowmya et al., 2010). Further, after analysed the data from 308 university students, Krichen and Chaabouni (2021) proved that perceived educational support positively affects entrepreneurial activities during the COVID-19. However, several researchers found that there was no effect to students’ intentions after taking entrepreneurship education and some students’ intentions even decreased (Mentoor and Friedrich, 2007; Oosterbeek et al., 2010). Various researchers explored the factors that affect entrepreneurship education and EI (see Table 1), while only a few studies investigated EI at a time of crisis (e.g., COVID-19). In this study, entrepreneurial intention can be defined as university students’ intention to participate into entrepreneurship. Hence, we hypothesized that: H4. Perceived positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship education (PPAEE) positively influence EI during COVID-19.

Methods

Data Collection

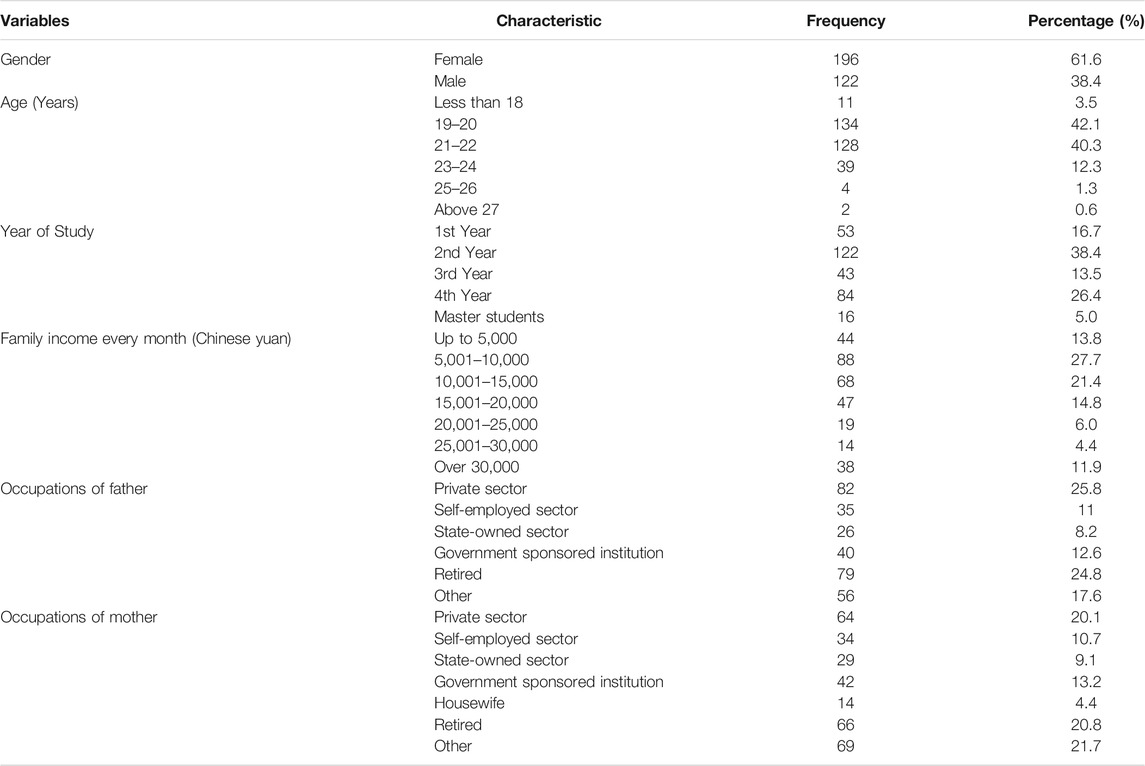

In order to ensure the validity and reliability of the questionnaire, it was translated into Chinese by a professional researcher, and then translated back to English by another language researcher. A pilot study was then conducted with ten students at a university to verify if the questionnaire was clear and easily understood. No problems were found. Then, the data was collected via social media (e.g., WeChat and email) direct to students in universities in Shanghai, China P.R. The target participants of this study were the students who have taken or attended the entrepreneurial courses or training at university. For participants, there is no requirements on their major. Before the data collection, the participants were informed of the research procedure. At the beginning of the survey, participants were asked to rate their perceptions and responses in the questionnaire. All participants were volunteers. There was no time limitation. In order to meet the requirement of this study, the data was cleaned. A total of 318 valid data was collected from 122 (38.4%) males and 196 (61.6%) females. The participants were mostly 19–22 years old (82.4%). The demographic information is analysed by frequency analysis (see Table 2).

Measures

All measures and scales were extracted from previous studies. The measures and scales of perceived positive attitudes on entrepreneurship education were adopted from Adekiya and Ibrahim (2016). The measures and scales of perceived self-efficacy were supported by Zhao et al. (2005); the measures and scales of perceived social norms were adopted from Boissin et al. (2017); the measures and scales of perceived entrepreneurial barriers were developed by Giacomin et al. (2011); and the measures and scales of EI were supported by Liñán et al. (2011). The measures and scales are presented in Supplementary Appendix SA. All the items were measured by a five-point Likert scale format ranging from “1 = strongly disagree/completely unsure/not at all/no confidence” to “5 = strongly agree/completely sure/very much/complete confidence.”

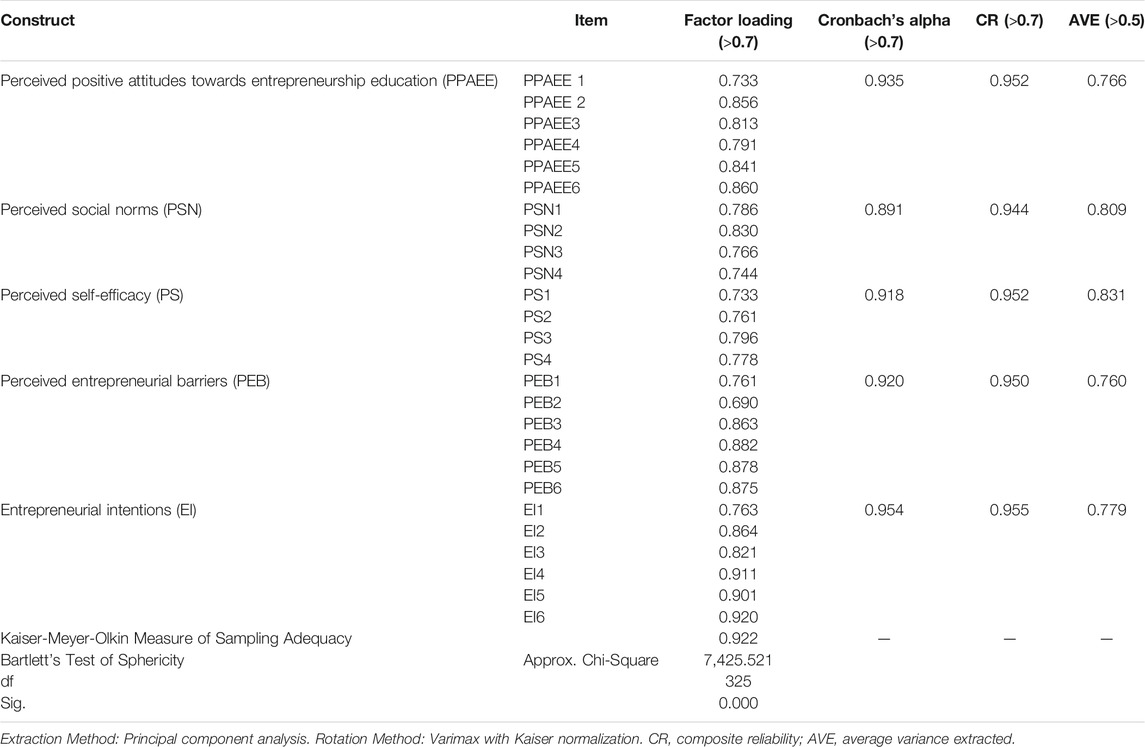

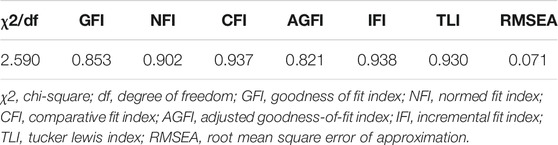

Both exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis are conducted in the data analysis. First, the reliability is tested by SPSS Statistics 25.0. The threshold of Cronbach’s alpha is higher than 0.7 (Hair et al., 2010). The factor loading should be above 0.5, and the value of Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin metrics (KMO) needed to be above 0.5 (Hair et al., 2010). Further, the confirmatory factor analysis is operated in SPSS Amos 23.0. The criteria of Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) values should be below than 0.6 (Hu and Bentler, 1999).

Results

Exploratory Factor Analysis

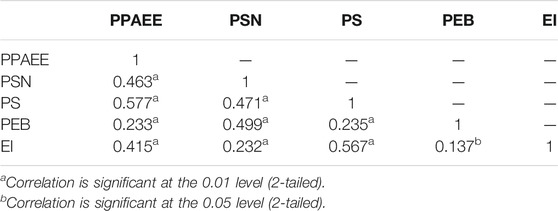

In the first step, the reliability and validity of the model was analysed. The validity is measured by three indices, namely, factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR). The result of exploratory factor analysis is presented in Table 3. There are 26 items, including perceived positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship education, perceived social norms, perceived self-efficacy, perceived entrepreneurial barriers, and EI. It can be seen that the scores of Cronbach’s alpha are between 0.891 and 0.954, the KMO = 0.922, CR > 0.950, AVE >0.760. Correlation of the constructs is significant (see Table 4), which indicated the reliability for the following analysis.

Hypothesis Testing

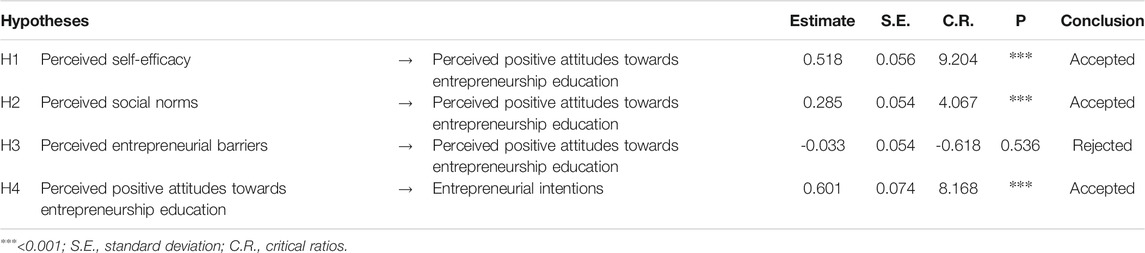

Based on the structural equation modelling, a fitting model was calculated in SPSS Amos 23.0. In total, the validity of the measurement model is confirmed. The relationships between constructs are presented in Figure 2. The overall fit statistics are presented in an acceptable level (see Table 5). As shown in Table 6, it can be found that H1 (β = 0.601, t = 8.168, p < 0.001), H2 (β = 0.518, t = 9.204, p < 0.001), and H3 (β = 0.285, t = 4.067, p < 0.001) were supported. H4 (β = −0.033, t = −0.618, p = 0.536) was not supported (see Table 6).

Discussion and Conclusion

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between perception and EI in university students during the time of COVID-19. Perceived self-efficacy, perceived social norms, perceived entrepreneurial barriers and perceived positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship education and EI are considered. This study presented an insight into variables that related to university students’ EI during the COVID-19 crisis.

Discussions

Although considerable empirical studies (Adekiya and Ibrahim, 2016; Elnadi and Gheith., 2021; Iwu et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021; Shahverdi et al., 2018) explore the factors that affect EI in different countries, most of them have not studied the relationship in the time of COVID-19. Before the TPB was adopted to test the relationship on EI (Boubker et al., 2021; Fragoso et al., 2019), there still needed to be further research on EI during the COVID-19 pandemic. This research studied four hypotheses via the research model. After data analysis, three proposed hypotheses were accepted, and one hypothesis was rejected.

The first hypothesis of this study (H1) indicated that perceived self-efficacy positively influences university students’ positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship education. Specifically, it shows that perceived self-confidence increases students’ positive attitudes towards the course of entrepreneurship. This means that the more confidence they have in themselves to develop their own businesses, the more satisfied and happier they may be in engaging in entrepreneurial education. The finding is in line with a previous study by Farashah (2013). Puni et al. (2018) found that self-efficacy and entrepreneurship education have a positive relationship.

A possible explanation for the finding may be that students like to create new products, develop new ideas and identify new business opportunities. It could further imply that university students intend to operate a business, rather than be employed by a company during the time of COVID-19. Additionally, it could also imply that students recognize the limited employment opportunities available during COVID-19. Therefore, they tend to have more creative and more inspired ideas for their own businesses.

The second hypothesis (H2) found that perceived social norms positively influence university students’ perceived positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship education. The finding corroborates with the findings of previous works by Boubker et al. (2021). This finding implies that students who have or run businesses are influenced by family, friends, teachers and other important persons, and thus, an influential person’s opinion would affect a student’s attitude to entrepreneurship education. It further suggests that during the time of COVID-19, these close relationships have an important effect on students’ decision-making. Therefore, the finding reveals that if university students get support from relatives and friends, they would like to devote themselves to entrepreneurship education and improve their entrepreneurial knowledge.

The result of the third hypothesis (H3) showed that there is no relationship between perceived entrepreneurial barriers and perceived positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship education. This result supports previous findings that lack of support was not considered as a potential barrier for an entrepreneur (Shahverdi et al., 2018). It indicates that during COVID-19, positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship education have no relationship with entrepreneurial barriers (e.g., lack of experience, lack of ideas, and lack of assistance or of formal help). As both intrinsic and extrinsic barriers of entrepreneurship may affect perceptions, this should be explored separately in entrepreneurship education. During COVID-19, the entrepreneurship courses and training are mainly conducted online. Significantly, there are almost no opportunities for students to visit or do internships in factories and companies that may influence their perception on entrepreneurial barriers as company operations may be influenced by the effects of COVID-19 and cannot offer opportunities for students to be involved through internships or part-time work. Limited work experience may influence their perceptions on barriers or risks of entrepreneurship.

With regard to EI, the fourth hypothesis (H4) indicated that students who have positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship education may be intending to become entrepreneurs. The finding supports previous studies by Boubker et al. (2021); Küttim et al. (2014); Iwu et al. (2021); Puni et al. (2018) and Liñán (2008). Students can identify opportunities and form creative ideas after having entrepreneurship education. A possible reason for this finding may be that students have positive attitudes to entrepreneurship education, which help them to increase their possibility of engaging in entrepreneurship and improve their impetus to develop their own businesses. Moreover, earlier findings indicate that as perceived entrepreneurship education can enhance students’ knowledge and abilities to find opportunities, it directly affects EI (Zhao et al., 2005). Additionally entrepreneurship education provides entrepreneurial knowledge, theories and cases in the study course, and the students get support to improve their EI. Thus, perceived positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship education can inspire students to start their own businesses during the time of COVID-19.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

The findings of the current study present theoretical and practical implications and suggestions for both public organizations and universities. In theoretical implications, our research findings highlight the perceptions in understanding the university students’ EI during COVID-19. Therefore, we contribute to a better understanding of university students’ entrepreneurship education in the period of COVID-19. Furthermore, this study develops a new model that is supported by data from Shanghai universities. This study enriches the entrepreneurship literature by considering the relationship of perceptions, perceived positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship education and EI. Finally, we extend the use of the TPB with a focus on entrepreneurship education and EI during the period of COVID-19. Thus, this study enriches the literature on university students’ perceptions and entrepreneurship education during COVID-19.

In practical implications, this research studied the perceptions and perceived positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship education in order to improve EI. First, further teaching methods should be explored in entrepreneurship. During the time of COVID-19, students can learn online, which is supported by video and audio technology, and obtain creative ideas from the e-training process. Entrepreneurship education triggers students’ innovative thinking and creativity on entrepreneurship. The universities should set up an entrepreneurship education centre to provide professional and business practice opportunities to students. Second, universities should create an entrepreneurial atmosphere for the public and provide support to students. Company managers, factory operators and entrepreneurs should be engaged in entrepreneurship education so as to extend students’ understanding with up-to-date news in entrepreneurship. Third, our study also provides some suggestions to teachers and education organizers. Barriers of entrepreneurship may be considered as an important section in entrepreneurship education. As most of the teachers have not received up-to-date business service training, it is essential to organize and establish an entrepreneurship team to not only improve the quality of entrepreneurship education and to help tackle the students’ entrepreneurship process but also to meet students’ requirements in entrepreneurship.

Our study offers some suggestions to universities, educational organizations and for government policies. Students’ perceptions and attitudes towards entrepreneurship education should be considered as vital factors for enhancing EI; creating more opportunities and entrepreneurial activities. Students should be fully involved in the entrepreneurship education training, course development and programmes. Thus, education organizers and university teachers should investigate students’ perceptions before and after entrepreneurship education, for example, track their attitudes on entrepreneurship after graduation and collect feedback to their entrepreneurship education.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are some limitations in this research. First, a small sample size was adopted to analyse the EI. Future studies can study more data from different areas of China P.R. In addition, there is no comparison of before and during the COVID-19 setting. It would be necessary to operate such a comparison, which may enrich the practical implications. Third, relevant influential factors such as students’ perceived desirability and perceived feasibility should be adopted to enrich the EI research model. Future studies could also adopt both quantitative and qualitative research methods to provide insight into the relationships among variables. Further empirical studies may focus on students from different disciplines that may have some effect on their attitudes to entrepreneurship education and EI during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Shanghai University of Engineering Science. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

PL contributed to design of the study. BL contributed to the data collection. PL, BL, and ZL performed the data analysis. PL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for Shanghai University of Engineering Science (No.0239-A3-0100-21-0928).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.770710/full#supplementary-material

References

Abou- Warda, S. H. (2016). New Educational Services Development: Framework for Technology Entrepreneurship Education at Universities in Egypt. Int. J. Educ. Manage. 30 (5), 698–717. doi:10.1108/IJEM-11-2014-0142

Adekiya, A. A., and Ibrahim, F. (2016). Entrepreneurship Intention Among Students. The Antecedent Role of Culture and Entrepreneurship Training and Development. Int. J. Manage. Edu. 14 (2), 116–132. doi:10.1016/j.ijme.2016.03.001

Ajzen, I. (1991). The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 50 (2), 179–211. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-t

Beynon, M. J., Jones, P., and Pickernell, D. (2016). Country-based Comparison Analysis Using fsQCA Investigating Entrepreneurial Attitudes and Activity. J. Business Res. 69 (4), 1271–1276. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.091

Blenker, P., Trolle Elmholdt, S., Hedeboe Frederiksen, S., Korsgaard, S., and Wagner, K. (2014). Methods in Entrepreneurship Education Research: a Review and Integrative Framework. Edu. + Train. 56 (8/9), 697–715. doi:10.1108/ET-06-2014-0066

Boissin, J.-P., Favre-Bonté, V., and Fine-Falcy, S. (2017). Diverse Impacts of the Determinants of Entrepreneurial Intention: Three Submodels, Three Student Profiles. Revue de l’Entrepreneuriat 16 (3), 17. doi:10.3917/entre.163.0017

Boubker, O., Arroud, M., and Ouajdouni, A. (2021). Entrepreneurship Education versus Management Students' Entrepreneurial Intentions. A PLS-SEM Approach. Int. J. Manage. Edu. 19, 100450. doi:10.1016/j.ijme.2020.100450

Boyd, N. G., and Vozikis, G. S. (1994). The Influence of Self-Efficacy on the Development of Entrepreneurial Intentions and Actions. Entrepreneurship Theor. Pract. 18 (4), 63–77. doi:10.1177/104225879401800404

Chen, C. C., Greene, P. G., and Crick, A. (1998). Does Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy Distinguish Entrepreneurs from Managers? J. Business Venturing 13 (4), 295–316. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(97)00029-3

Elnadi, M., and Gheith, M. H. (2021). Entrepreneurial Ecosystem, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, and Entrepreneurial Intention in Higher Education: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Manage. Edu. 19, 100458. doi:10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100458

Elster, J. (1989). Social Norms and Economic Theory. J. Econ. Perspect. 3 (4), 99–117. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-62397-6_2010.1257/jep.3.4.99

Farashah, A. D. (2013). The Process of Impact of Entrepreneurship Education and Training on Entrepreneurship Perception and Intention: Study of Educational System of Iran. Edu. + Train. 55 (8/9), 868–885. doi:10.1108/ET-04-2013-0053

Fragoso, R., Rocha-Junior, W., and Xavier, A. (2019). Determinant Factors of Entrepreneurial Intention Among university Students in Brazil and Portugal. J. Small Business Entrepreneurship 32, 33–57. doi:10.1080/08276331.2018.1551459

Giacomin, O., Janssen, F., Pruett, M., Shinnar, R. S., Llopis, F., and Toney, B. (2011). Entrepreneurial Intentions, Motivations and Barriers: Differences Among American, Asian and European Students. Int. Entrep Manag. J. 7, 219–238. doi:10.1007/s11365-010-0155-y

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Babin, B. J., and Black, W. C. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective. 4th ed.. NJ, USA: Pearson.

Harima, A., Gießelmann, J., Göttsch, V., and Schlichting, L. (2021). Entrepreneurship? Let Us Do it Later: Procrastination in the Intention-Behavior gap of Student Entrepreneurship. Ijebr 27, 1189–1213. doi:10.1108/IJEBR-09-2020-0665

Harris, M. L., and Gibson, S. G. (2008). Examining the Entrepreneurial Attitudes of US Business Students. Edu. + Train. 50 (7), 568–581. doi:10.1108/00400910810909036

Hu, L. T., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equation Model. A Multidisciplinary J. 6 (1), 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

Ibrahim, A. B., and Goodwin, J. R. (1986). Perceived Causes of success in Small Business. Am. J. Small Business 11 (2), 41–50. doi:10.1177/104225878601100204

Iwu, C. G., Opute, P. A., Nchu, R., Eresia-Eke, C., Tengeh, R. K., Jaiyeoba, O., et al. (2021). Entrepreneurship Education, Curriculum and Lecturer-Competency as Antecedents of Student Entrepreneurial Intention. Int. J. Manage. Edu. 19, 100295. doi:10.1016/j.ijme.2019.03.007

Iyer, A., Schmader, T., and Lickel, B. (2007). Why Individuals Protest the Perceived Transgressions of Their Country: the Role of Anger, Shame, and Guilt. Pers Soc. Psychol. Bull. 33, 572–587. doi:10.1177/0146167206297402

Jones, S., and Underwood, S. (2017). Understanding Students' Emotional Reactions to Entrepreneurship Education. Et 59 (7/8), 657–671. doi:10.1108/ET-07-2016-0128

Krichen, K., and Chaabouni, H. (2021). Entrepreneurial Intention of Academic Students in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic. Jsbed. ahead-of-print. doi:10.1108/JSBED-03-2021-0110

Küttim, M., Kallaste, M., Venesaar, U., and Kiis, A. (2014). Entrepreneurship Education at University Level and Students' Entrepreneurial Intentions. Proced. - Soc. Behav. Sci. 110, 658–668. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.910

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., and Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a Unifying Social Cognitive Theory of Career and Academic Interest, Choice, and Performance. J. Vocational Behav. 45, 79–122. doi:10.1006/jvbe.1994.1027

Li, Z., and Liu, Y. (2011). Entrepreneurship Education and Employment Performance: An Empirical Study in Chinese university. J. Ent Emerg 3 (3), 195–203. doi:10.1108/17561391111166975

Lin, S., and Xu, Z. (2017). The Factors that Influence the Development of Entrepreneurship Education. Md 55 (7), 1351–1370. doi:10.1108/MD-06-2016-0416

Liñán, F., Rodríguez-Cohard, J. C., and Rueda-Cantuche, J. M. (2011). Factors Affecting Entrepreneurial Intention Levels: A Role for Education. Int. Entrep Manag. J. 7 (2), 195–218. doi:10.1007/s11365-010-0154-z

Liñán, F. (2008). Skill and Value Perceptions: How Do They Affect Entrepreneurial Intentions? Int. Entrep Manage. J. 4 (3), 257–272. doi:10.1007/s11365-008-0093-0

Liu, H., Kulturel-Konak, S., and Konak, A. (2021). A Measurement Model of Entrepreneurship Education Effectiveness Based on Methodological Triangulation. Stud. Educ. Eval. 70, 100987. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2021.100987

Meahjohn, I., Persad, P., and Persad, P. (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 on Entrepreneurship Globally. jeb 3 (3), 1165–1173. doi:10.31014/aior.1992.03.03.272

Mentoor, E. R., and Friedrich, C. (2007). Is Entrepreneurial Education at South African Universities Successful? Industry Higher Edu. 21 (3), 221–232. doi:10.5367/000000007781236862

Mohamad, N., Lim, H.-E., Yusof, N., and Soon, J.-J. (2015). Estimating the Effect of Entrepreneur Education on Graduates' Intention to Be Entrepreneurs. Edu. + Train. 57 (89), 874–890. doi:10.1108/ET-03-2014-0030

Nabi, G., Holden, R., and Walmsley, A. (2010). Entrepreneurial Intentions Among Students: towards a Re‐focused Research Agenda. Jrnl Small Bus Ente Dev. 17 (4), 537–551. doi:10.1108/14626001011088714

Oosterbeek, H., Van Praag, M., and Ijsselstein, A. (2010). The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education on Entrepreneurship Skills and Motivation. Eur. Econ. Rev. 54 (3), 442–454. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2009.08.002

Peterman, N. E., and Kennedy, J. (2003). Enterprise Education: Influencing Students' Perceptions of Entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theor. Pract. 28 (2), 129–144. doi:10.1046/j.1540-6520.2003.00035.x

Pittaway, L., and Edwards, C. (2012). Assessment: Examining Practice in Entrepreneurship Education. Edu. + Train. 54 (8/9), 778–800. doi:10.1108/00400911211274882

Puni, A., Anlesinya, A., and Korsorku, P. D. A. (2018). Entrepreneurial Education, Self-Efficacy and Intentions in Sub-saharan Africa. Ajems 9 (4), 492–511. doi:10.1108/AJEMS-09-2017-0211

Ratten, V. (2020). Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) and Sport Entrepreneurship. Ijebr 26 (6), 1379–1388. doi:10.1108/IJEBR-06-2020-0387

Ratten, V., and Jones, P. (2021). COVID-19 and Entrepreneurship Education: Implications for Advancing Research and Practice. Int. J. Manage. Edu. 19 (1), 100432. doi:10.1016/j.ijme.2020.100432

Ratten, V., and Jones, P. (2018). Future Research Directions for Sport Education: toward an Entrepreneurial Learning Approach. Et 60 (5), 490–499. doi:10.1108/ET-02-2018-0028

Roman, M., and Plopeanu, A.-P. (2021). The Effectiveness of the Emergency eLearning during COVID-19 Pandemic. The Case of Higher Education in Economics in Romania. Int. Rev. Econ. Edu. 37, 100218. doi:10.1016/j.iree.2021.100218

Ruiz-Rosa, I., Gutiérrez-Taño, D., and García-Rodríguez, F. J. (2020). Social Entrepreneurial Intention and the Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic: a Structural Model. Sustainability 12 (17), 6970. doi:10.3390/su1221895810.3390/su12176970

Shahverdi, M., Ismail, K., and Qureshi, M. I. (2018). The Effect of Perceived Barriers on Social Entrepreneurship Intention in Malaysian Universities: The Moderating Role of Education. Manage. Sci. Lett. 8, 341–352. doi:10.5267/j.msl.2018.4.014

Shrivastava, U., and Acharya, S. R. (2020). Entrepreneurship Education Intention and Entrepreneurial Intention Amongst Disadvantaged Students: an Empirical Study. Jec 15, 313–333. doi:10.1108/JEC-04-2020-0072

Souitaris, V., Zerbinati, S., and Al-Laham, A. (2007). Do entrepreneurship Programmes Raise Entrepreneurial Intention of Science and Engineering Students? the Effect of Learning, Inspiration and Resources. J. Business Venturing 22, 566–591. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.05.002

Stamboulis, Y., and Barlas, A. (2014). Entrepreneurship Education Impact on Student Attitudes. Int. J. Manage. Edu. 12, 365–373. doi:10.1016/j.ijme.2014.07.001

Tessema Gerba, D. (2012). The Context of Entrepreneurship Education in Ethiopian Universities. Manage. Res. Rev. 35 (3/4), 225–244. doi:10.1108/01409171211210136

Theng, L. G., and Boon, J. L. W. (1996). An Exploratory Study of Factors Affecting the Failure of Local Small and Medium Enterprises. Asia Pac. J Manage 13 (2), 47–61. doi:10.1007/BF01733816

Tkachev, A., and Kolvereid, L. (1999). Self-employment Intentions Among Russian Students. Entrepreneurship Reg. Dev. 11, 269–280. doi:10.1080/089856299283209

Tsai, K.-H., Chang, H.-C., and Peng, C.-Y. (2014). Extending the Link between Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Intention: a Moderated Mediation Model. Int. Entrep Manag. J. 12, 445–463. doi:10.1007/s11365-014-0351-2

Varadarajan Sowmya, D., Majumdar, S., and Gallant, M. (2010). Relevance of Education for Potential Entrepreneurs: an International Investigation. Jrnl Small Bus Ente Dev. 17 (4), 626–640. doi:10.1108/14626001011088769

von Graevenitz, G., Harhoff, D., and Weber, R. (2010). The Effects of Entrepreneurship Education. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 76, 90–112. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2010.02.015

Wardana, L. W., Narmaditya, B. S., Wibowo, A., Mahendra, A. M., Wibowo, N. A., Harwida, G., et al. (2020). The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education and Students' Entrepreneurial Mindset: the Mediating Role of Attitude and Self-Efficacy. Heliyon 6, e04922. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04922

Yousaf, U., Shamim, A., Siddiqui, H., and Raina, M. (2015). Studying the Influence of Entrepreneurial Attributes, Subjective Norms and Perceived Desirability on Entrepreneurial Intentions. J. Entrepreneurship Emerging Econ. 7 (1), 23–34. doi:10.1108/JEEE-03-2014-0005

Keywords: perceived barriers, perceived self-efficacy, perceived social norms, perceived positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial intention

Citation: Li P, Li B and Liu Z (2021) The Impact of Entrepreneurship Perceptions on Entrepreneurial Intention During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Educ. 6:770710. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.770710

Received: 04 September 2021; Accepted: 15 November 2021;

Published: 09 December 2021.

Edited by:

Fu Bajun, Shaoxing University, ChinaReviewed by:

Isabel Nunes Janeiro, Universidade de Lisboa, PortugalAli Hosseini Khah, Kharazmi University, Iran

Copyright © 2021 Li, Li and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pei Li, cGVpLmxpQHN1ZXMuZWR1LmNu; Ziyang Liu, bW9ybmluZ2x6eUBob3RtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Pei Li

Pei Li Bing Li2†

Bing Li2† Ziyang Liu

Ziyang Liu