94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 20 December 2021

Sec. Special Educational Needs

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.739384

The purpose of this study was to investigate how general and special education instructors perceive their collaborative teaching responsibilities and their attitudes toward inclusive environments. A self-administered questionnaire was distributed to 300 teachers in accordance with the social interdependence theory and cooperative learning conceptual framework. The survey was composed of two parts. The first section examined collaborative teaching duties for both instructors. It included 29 items and four categories (planning, instruction, evaluation, and behavior management). The second section included 15 items to assess attitudes toward inclusion. The study enrolled a total of 233 teachers (123 in special education and 110 in general education) with a response rate of 78%. The results showed that there was agreement between general and special education on only one of the four domains (instruction). Additionally, special education teachers expressed a more favorable attitude toward inclusion than did general education teachers. The current situation’s implications were explored with an emphasis on the necessity for additional shared practical activities among teachers.

Since the 1960s, the groundwork for inclusive education has been laid with many calls for the “mainstreaming” of students with disabilities (SWDs). The foundation of this movement was celebrated within the United Nations International Year of Disabled Persons in 1981, which focused on the full participation in society for all people with disabilities (Hornby, 2015).

A convention for inclusive education was provided in 2006 by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. This convention stressed the right for the inclusion of SWDs with other students, equal access to schools, and provision of accommodations on all levels of learning (Lyons et al., 2016). This protocol proposed by the convention for inclusive education has shown great benefits for SWDs including an increase in academic skills (Szumski and Karwowski, 2015; Van Hove, 2015; Schnepel et al., 2020), sense of belonging (Potter, 2015; Garrote, 2017; Snipstad, 2019), participation (Potter, 2015; Snipstad, 2019), and emotional and cognitive development (Potter, 2015; Smogorzewska et al., 2019).

Collaboration has evolved into a vital component of the effectiveness and success of inclusive education (Mulholland and O'Connor, 2016) and the primary strategy necessary to establish inclusive schools (Hansen et al., 2020). To facilitate this collaboration, a consensus needs to be reached between general and special education instructors regarding the roles and objectives of inclusion in the classroom (Zagona et al., 2017).

Collaboration can be defined as “a professional partnership between two or more coequal educators who share responsibility, accountability, and resources” (Da Fonte and Barton-Arwood, 2017). This shared responsibility has raised numerous concerns, particularly among general education teachers. When both general and special education teachers are challenged with unplanned practices specific to the inclusive environment, this may impede the successful implementation of inclusion (Mulholland and O'Connor, 2016). Some of these unplanned practices are observable in research related to collaboration. Some research has reported that SWDs in general education classrooms are mainly the responsibility of special education teachers, including student achievement follow-up (Tiwari et al., 2015) and the implementation of inclusive practices (Moreno et al., 2015). This is expected especially when teachers have different views of inclusive education and the way it might be implemented. Teachers struggle in defining the roles and goals of both teachers that are most suitable for the proper implementation of inclusion. Many researchers have argued that teacher professional development that contains proper collaboration skills and defined roles provides better support for inclusive education (Able et al., 2015).

To build a proper collaboration among different teachers, certain factors need to be addressed and aligned with the philosophy of inclusion. One of the factors is the perspectives of teachers about inclusion and its practices, which might influence the implementation of such practices. Chitiyo (2017) mentioned the issue of differing philosophies as a main challenge to inclusion. With the increasing number of SWDs, teachers prefer not to collaborate on instruction in order to focus more on the separate classroom groups. Zagona et al. (2017) found that different philosophies and perspectives affected majorly on the delivery of services and collaboration among teachers. These different perspectives can be the outcome of many factors including the lack of adequate preparation by pre-service training programs (Mackey, 2014; Zagona et al., 2017), limited collaboration among teachers (Mulholland and O'Connor, 2016; Villa et al., 1996; Zagona et al., 2017), and lack of administrative support (Da Fonte and Barton-Arwood, 2017; Mulholland and O'Connor, 2016).

Inclusion has modified the different roles of both general and special education teachers. Most teaching was performed in either resource or special rooms away from the general classroom by the special education teacher. With inclusive practices, this role has shifted to be performed mainly by the general education teacher in cooperation with the special educator, a shift from providing specially designed instruction to adapting the general education content to the SWDs (Zigmond et al., 2009). It is expected that each teacher will have their main role in the general classroom in addition to many shared roles that can be assigned as a common responsibility to both teachers. A major example of the shared responsibility is the “collaborative consultation”, which is described as a reciprocal arrangement between the general and special education teachers. In order to facilitate such an assignment, both teachers should work on four main aspects where consultation can (1) be reciprocal, (2) facilitate problem-solving skills, (3) be a routine part of interaction and daily functioning, and (4) use proper communication language (Lamar-Dukes and Dukes, 2005).

Jordan, a Middle Eastern country, has been one of the pioneers in the MENA region in providing services to individuals with disabilities. Jordan’s school system consists of 12 classes preceded by 2 years of preschool (KG1-2), with years one through ten being mandatory for all students. Following the 10th grade, students have 2 years of optional secondary education that typically prepares them for university or vocational programs. Special education services in Jordan began with the establishment of the Holy Land College for deaf students in the 1970s. Additional private service providers have emerged in the form of special education institutions/centers providing services for a wide range of severe disabilities (Hadidi, 1998) with the private sector running the majority of institutions/centers.

Following Jordan’s participation in and adoption of the Salamanca Statement (Education, 1994), a paradigm shift in service delivery occurred, resulting in the formation of the Law for the Welfare of Disabled People (No. 12/1993). This was reinforced in 2007 by the enactment of the Law on Disabled People’s Rights (No. 31/2007). These laws resulted in establishing resource rooms within public institutions.

The Higher Council for Persons with Disabilities (HCPD) was established in 2008 as an autonomous national institution that serves as the primary policymaking and planning authority (Thompson, 2018). In 2016, the HCPD drafted a new law on the Rights of People with Disabilities (HCRPD, 2017). The new law reaffirmed disabled people’s rights to education and employment. This was translated into a 10-year strategy plan for inclusive education in 2018 (Education, 2018), which set the groundwork for the inclusion of all disabilities in the general education classrooms.

The implementation began in 2019 with approximately 150 public schools in addition to other private schools providing physical accessibility, accommodations, adequate teacher preparation, and awareness for all stakeholders, including school administrators, teachers, students, their families, and society in general.

In keeping with prior advancements, higher education has been providing educational programs to qualify teachers to work with all students. Jordan’s higher education system is modeled after the American credit system, and most educational programs are based on international standards [i.e., National Council for the Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE), National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC), and Council of Exceptional Children (CEC)]. Many programs are now working to be accredited by such entities and, as a result, are undergoing significant changes in order to qualify. Amr (2011) looked at undergraduate programs in a number of Arab nations. One or two special education courses are frequently offered in early childhood and early primary education programs (introductory courses in Special Education and Learning Disabilities). These courses cover a broad range of theoretical topics with little practical application. Aside from special education, no courses about collaboration were found in any undergraduate program.

As a result of this, many international notions regarding inclusion and concepts of collaboration have been embraced and used without regard for cultural characteristics in the Jordanian setting. This resulted in a lack of understanding around what inclusive education is or how an educational system should look within a different cultural context, especially with the short period of service delivery to SWDs. This new experiment will be an eye opener for many countries that have a comparable short history of educating children with disabilities.

This is especially true in Arab countries, particularly those in the Middle East and the Gulf countries (Alzahrani, 2020). Jordan’s situation might serve as a model for inclusion, elucidating and displaying the necessary joint efforts from general and special education teachers in order to fulfill their roles and responsibilities. Furthermore, the efficacy of inclusion is still under investigation, which might promote utilizing other educational alternatives, i.e., resource rooms or special classrooms (Gaad & Khan, 2007).

Accordingly, this promotion of inclusive education demanded many changes in educational systems and a shift from the traditional system to a more comprehensive system where specialists, principals, and teachers need to work together to ensure its success. This change necessitated that both general and special education have a different preparation to manage their altered roles and duties, which was a challenge and a source of debate among educators (Shade and Stewart, 2001). Furthermore, to ensure such a successful inclusion, the issue of teachers’ attitudes toward the practice needs to be addressed (Forlin et al., 2010; De Boer et al., 2011). The attitudes and perceptions of teachers influence the success of inclusive practices. Teachers’ positive attitudes have been an issue of research as a main factor for success. Its presence helps majorly in its implementation. It has been concluded that “inclusion largely depends on teachers’ attitudes towards learners with SEN [special education needs], their view of differences in classrooms, and their willingness to respond positively and effectively to those differences” (Education, 2003).

Many factors have been studied in relation to attitudes toward inclusion. The effect of gender revealed many conflicting results. Some did not find any differences between male and female teachers while others showed that female teachers hold more positively towards inclusion than male teachers (Alghazo and Naggar Gaad, 2004; Alquraini, 2012). Others examined teachers’ self-efficacy having a positive correlation with positive attitudes (Vieluf et al., 2013; Malinen and Savolainen, 2016; Aiello et al., 2017). In addition, teachers training had a part, where proper training yielded positive attitudes toward inclusion (Ahsan et al., 2012). Other variables also related to attitudes were the type and severity of a child’s disability (Moberg, 2003) and administrative support. Another factor is teacher categories where special education teachers have the most positive attitudes towards inclusion (Moberg, 2003; Hernandez et al., 2016; Engelbrecht and Savolainen, 2018).

Additionally, concerns and barriers to successful inclusion were also examined, including the factors of a lack of proper pre-services preparation and lack of resources (Lambe and Bones, 2006; McCray and McHatton, 2011). Other noticeable concerns were examined especially when considering collaboration within a co-teaching environment. General education teachers expressed apprehensions about special education teachers, especially concerning their preparations for the collaborative efforts in teaching. The issue of the “inadequacy” of some special education teachers in providing proper support in an inclusive setting was also highlighted (Liasidou and Antoniou, 2013). Furthermore, novice special education teachers expressed concern about their preparation due to the lack of coursework in collaboration (Carlson et al., 2002) and the implementation of collaboration with all personnel including professionals and families (Conderman and Stephens, 2000).

The issue of collaborative teaching has been raised with many concerns professed by both general and special education teachers. The implementation of inclusion has necessitated that both teachers resolve any conflicting roles affecting classroom management including the instruction and evaluation of students among other roles required in the regular classroom. Many voices are pushing for the shared responsibility in class to solve this problem. Nevertheless, barriers to such collaboration are still important factors that need to be addressed including the lack of communication, teacher’s attitudes, and teacher preparation and competencies (Conderman and Johnston-Rodriguez, 2009).

When considering collaboration and teacher relationships, Vygotsky’s sociocultural theoretical background emerges as the construct that focuses on connections between people and the sociocultural context in which they act and interact. According to this paradigm, this model describes learning as a social process that takes place inside a society or culture. This theoretical background exhibits an understanding of how knowledge is constructed and evolves in a social context, where knowledge is created throughout time as a result of interactions and joint attempts to make sense of new information (McLeskey et al., 2014).

From the roots of the sociocultural theoretical background, the social interdependence theory emerged to serve as the foundation for defining cooperative learning. Koffka’s social interdependence theory views groups as a unit, with the essence of a group being its members’ interdependence, typically guided by common achievable goals, which results in the group being dynamic (Johnson et al., 2014). The conditions found in social interdependence theory are positive interdependence (cooperation), which results in promotive interaction, negative interdependence (competition), which typically results in oppositional interaction, and no interdependence (individualistic efforts), which typically results in no interaction. Since 1949, social interdependence theory has served as a fundamental theoretical background for this field of study and has spawned hundreds of studies.

Social interdependence theory laid the groundwork for cooperative learning. The theory has been operationalized to include methods for the teacher’s role in formal and informal cooperative learning, as well as cooperative base groups. These practices are frequently employed by educators worldwide (Johnson and Johnson, 2009).

Teachers working together in the classroom have a responsibility to not only provide effective instruction to their students but also work cooperatively with one another. Johnson and Johnson (1989) cautioned that “placing people in the same room. Seating them together, telling them that they are a cooperative group, and advising them to “cooperate” does not make them a cooperative group” (p. 15). Although the concept is based on cooperative learning, it can be easily applied to educators who are working in a collaborative model (Johnson and Johnson, 1989).

Johnson et al. (2014) saw cooperative learning as a conceptual framework that promotes interaction to accomplish shared goals in cooperative contexts in order to maximize each other’s learning. Hence, cooperative learning (Johnson and Johnson, 1989) provides a foundation for the social production and promotion of independent practices. Although cooperative learning has a strong influence on this study, the idea of social interdependence exhibits collaborative teaching as an instructional approach that builds highly on the collaborative efforts of teachers inside the classroom.

Although this framework is the foundation for cooperative learning for students, the principles that combine together can easily apply to the collaborative relationship. These principles can be the foundation for an effective teaching environment that necessitates the same components through which teachers connect and share experiences and collaborate effectively (Johnson and Edge, 2012).

Cooperative learning focuses on five important characteristics of effective cooperative learning. The five pillars of cooperative learning theory are consistent with the concept of collaboration and include the following: (1) positive interdependence, (2) face-to-face interaction, (3) individual accountability, (4) group processing, and (5) interpersonal and small group skills, “social skills,” that enable every teacher to participate in the teaching process. Each of the five components of cooperative learning theory clarifies the social context for cooperative teaching in the classroom as well as the roles expected of all group members.

The first component is positive interdependence, which indicates that group members collaborate to accomplish common goals (Tran, 2013). The second component reflects individual interactions physically or verbally in order to accomplish group goals. Another part of this component is the feedback between teachers in order to improve the collaborative teaching model, proper teaching strategies, and new methods to enrich the classroom environment (Johnson and Johnson, 2009).

Individual responsibility is the third component; it ensures that each teacher performs their responsibilities while also contributing to the general success of collaborative teaching (Slavin, 2011). The fourth component is group processing; teachers must process information in order to comprehend and modify adjustments. This reflection enables collaborative teachers to assess their progress and provide feedback while also keeping a healthy relationship (Tran, 2013). Finally, interpersonal and social group skills are included; without effective communication, teachers will be unable to collaborate effectively. Johnson and Johnson (2009) recommend that certain skills be embedded in teacher preparation programs, including trust building, clear communication, acceptance and support, and, finally, conflict resolution.

The conceptual framework from which the research questions were derived focused on how general and special education teachers perceive roles, collaboration, monitoring, limitations, challenges, and assignment to an inclusive classroom in a collaborative teaching setting (Johnson et al., 2014).

All the previous parts cited above emphasized the importance of collaboration to achieve a successful inclusion of students in the general classroom. Nevertheless, more research is needed in order to understand the roles and responsibilities of both teachers with regard to their students. The importance of the current study lies in the idea that both teachers have to express and reveal their expected perceived roles in inclusive settings and to explore any effect of their attitudes towards their responsibilities for students with disabilities. This will facilitate and provide further insight into both pre- and in-service training for both teachers. The topic of inclusion in our countries is still under-investigated and yearning for further studies, and hopefully, this study will shed some light on the significance and magnitude of collaboration in the success of inclusion practices in the general school. Accordingly, this study attempted to answer the following questions:

1) How do general and special education teachers perceive their responsibilities and roles in collaborative teaching?

2) What are the attitudes of general and special education teachers toward inclusive settings and their collaborative teaching within?

The designated population for this research was all general and special education teachers working in inclusive settings in the capital of Jordan, Amman. A list of all-inclusive schools was attained from the Ministry of Education. A simple random sample of 40 schools was chosen (20 public and 20 private) with a total number of 300 surveys sent to both general and special education teachers. Out of the total number, only 254 surveys were returned. After a thorough review of the surveys, only 233 surveys were used due to incomplete surveys or false responses, representing a 78% response rate from 45 schools. Table 1 represents some of the demographics related to the sample.

The instrument used consisted of two parts. The first part was based on the work of Fennick (1995) and was guided by the conceptual framework of the cooperative learning theory, where the researcher addressed the issue of collaborative responsibility in relation to some variables (Fennick, 1995; Fennick and Liddy, 2001). The purpose of this part was to explore the collaborative teaching roles according to both general and special education teachers. Items reflected how both teachers perceive the different tasks and roles as either their responsibility or the others. This reflected either positive or negative interdependence, communication with the classroom partner, and accountability either by taking the responsibility or projecting the assignment on the other member. The questionnaire items were clustered into four areas as domains: planning (8 items), reflecting communication and social skills; instruction (10 items), reflecting the interdependence between teachers and accountability; evaluation (4 items), which was aligned with group processing and the need to provide proper feedback to students; and behavior management (7 items), which also reflected communication and social skills. The items used a Likert scale where they were divided according to the roles expected. Numbers 1–2 reflected special education teachers, number 3 reflected the collaborative work of both teachers, and 4–5 reflected the work of the general education teacher. A low score meant that this item is mainly for special education teachers and the higher score is referenced to the general education teacher.

The second part of the instrument aimed to measure the attitudes of teachers toward inclusion. A 15-item instrument was developed based on a thorough review of the literature (Hammond and Ingalls, 2003; Kim, 2011; Swain et al., 2012; Taylor and Ringlaben, 2012). Five items (5, 6, 7, 8, and 9) were negatively worded and then reversed for analysis purposes. All items used a 5-point Likert-type scale to reflect the teacher’s responses, with five indicating “Strongly agree” and one indicating “Strongly disagree.” As previously mentioned, negative item scores yielded an opposite meaning. Items were categorized into three levels: negative attitudes (1–2.33), average/neutral (2.33–3.66), and positive attitudes (3.67–5).

To examine the test validity, the two instruments were sent to ten experts specializing in general and special education. Minor changes presented by the experts were incorporated into the instrument. Moreover, to estimate the reliability of each domain, an internal consistency coefficient for the instrument was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha method. The alpha score of the test was 0.72 for planning, 0.73 for instruction, 0.62 for evaluation, 0.70 for behavior management, and 0.80 for attitudes toward inclusion.

In order to distinguish the different responsibilities for each teacher group, all items from the four perception domains were joined and averaged. Then, items were accordingly ranked by item means, with the lower end items (1–2) indicating the perceived responsibilities of special education teachers and the highest (4–5) indicating those of general education teachers. To set cutoff points, items rated <2.5 were considered as special education responsibilities and items rated >3.5 general education responsibilities. Items ranked 2.51–3.49 were shared tasks.

Data collection was initially intended to be done using paper and pencil especially since this would provide participants the opportunity for answers in case of any evolving questions. However, due to the COVID lockdown and lack of direct access to some schools, it was decided to transfer the instrument into an electronic form. Therefore, an electronic Google form was constructed and supervisors and administrators were contacted to send them a direct link. An introductory page was initiated to request a consent from all participants. Any participants who declined to provide an electronic consent were provided a thank you message and were not allowed to continue to the instrument. Therefore, all participants who provided an informed consent were provided with an electronic approval to participate in the data collection. All participants were encouraged to read all items carefully and chose the appropriate answer according to their perceptions. All participants were assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of their responses.

The data that emerged from the electronic form were extracted, entered into the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), and analyzed using the SPSS software package. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, means, and standard deviations, were determined to answer the main research questions. Differences between the groups were determined using t-tests for independent samples among the ranked categories of data.

This study aimed to explore the perceptions of general and special education teachers about their roles and responsibilities within the inclusive settings and roles of collaborative teaching. The first question examined how general and special education teachers perceive their responsibilities and roles of collaborative teaching.

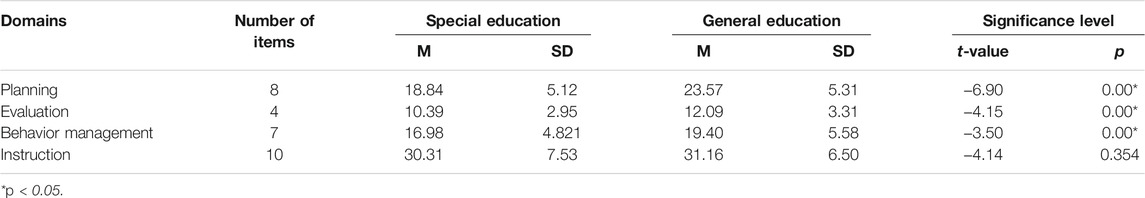

To explore the different perceptions of the two groups, independent sample t-tests were used to examine which group had higher means and if there were any significant differences in their perceptions toward the different domains, examining the degree of agreement between them. The results of the t-tests are displayed in Table 2.

TABLE 2. T-test comparison of special education and general education teachers on the four domains of the instrument.

Out of the four domains, three domains had significant differences, indicating a disagreement between general and special education teachers in planning, evaluation, and behavior management. To further evaluate how each teacher perceives the responsibilities of each group, means were calculated for each task and ranked in order from low to high. Cutoff points were made according to the original domains. Scores were divided into three categories: the lower scores (1–2.5) represent tasks for special education teachers, the higher scores (3.5–5) represent general education, and the mid-range scores (2.51–3.49) represent shared tasks done by both teachers.

Table 3 shows responsibilities ranked by item means from special education (1) to general education (5) and grouped as special education (1–2.5) to general education (3.5–5) and the middle range as combined/shared by both.

All tasks were distributed among the three categories. The special education domain had nine tasks assigned having the task “Adapt lessons and instructional materials for special education students” as the most aligned task to the special education teacher. Most of the items in this category were related to the two domains of planning and behavior management. The other end of the ranked items was delineated to general education teachers. This category only had four tasks and all were associated with the instruction domain. The highest category with the most tasks assigned were the shared category; this category contained sixteen items. The highest domain presented was planning followed by both instruction and behavior management and ending with evaluation.

To investigate the attitudes of both groups toward inclusion, an independent sample t-test was also used. Results showed a positive attitude of special education teachers towards the inclusion of students with disabilities compared to an average level of attitude for general education teachers. Furthermore, out of the fifteen items, eight items had significant differences between the two groups with most in favor of special education teachers. Table 4 represents the means and differences between the two groups.

The purpose of this study was to examine the perceptions of special and general education teachers toward collaborative teaching including teacher’s responsibilities and roles and their attitudes toward inclusive settings. The current study tried to examine the different perspectives of general and special education teachers related to their collaborative roles in the general classroom.

Due to the shift in Jordan from the traditional non-inclusive systems to inclusive education, many changes are needed within this environment. A major change would be the educational preparation of teachers to provide the most effective experience in this new environment (Education, 2018). The Council for Exceptional Children (CEC) has addressed collaboration as a major standard (standard 7) for special education programs. Other bodies of accreditation (i.e., NCATE) offer the same principle, which manifests the importance of collaboration for the success of students in general schools (CEC, 2021). The NCATE and other teacher education accreditation councils are considered as the main structure and reference for the formulation of most educational programs in Jordan. The expected effectiveness of inclusive education can be referred to the proper preparation of general and special education teachers in addition to the support and help provided by the school administrator and the educational system.

According to the cooperative learning conceptual framework (Johnson and Johnson, 1989; Johnson and Johnson, 2009; Johnson et al., 2014), the need for cooperative interaction between general and special education teachers can be considered as an important component for the success of inclusion. The proper communication, interactive skills, processing of day-to-day interactions, and accountability will eventually foster positive interdependence, which will lead to a constructive collaborative teaching relationship. This study provides further evidence of the complexity hindering the understanding of the teaching practices among the teachers themselves. It is noticeable that the different perspectives of teachers toward their responsibilities could be a major barrier to the development of a successful classroom for both students with and without disabilities in inclusive classrooms.

It is critical for educators to understand the components of collaborative teaching that are effective and the aspects that contribute to a healthy learning environment. By guiding this research with appropriate theories, the cooperative learning theory (Johnson and Johnson, 2009; Johnson et al., 2014) established a framework for implementing collaborative teaching. When used as a framework, these ideas can assist school teachers in developing a knowledge of effective cooperation and best teaching practices. While there is some agreement among teachers in this study, the factors suggested by Johnson and Johnson (2009), such as communication and social skills, group processing, and appropriate feedback, were deemed inadequate despite the fact that the preceding components are the foundation for effective communication and interaction. These tenets should be particularly studied by future preservice teachers as part of their graduate preparation programs in order to better prepare them to work in inclusive settings.

This is evident in the four collaboration categories examined; while both groups agreed on the roles of instruction for students, three of the four collaboration categories (planning, evaluation, and behavior management) revealed disagreement. In previous research by Fennick (1995), participants disagreed on two categories (instruction and behavior management) out of the four categories, which yields a shift in roles in regard to the instruction category.

The agreement on the instruction category reflects the clear model that is usually implemented in our school system, where one teacher is responsible for whole-class instruction while the other teacher supervises student work or provides brief (1–2 min) instructional support during independent work periods especially for SWDs (Solis et al., 2012). Nevertheless, when examining the different roles assigned to both teachers, even the points of agreement propose some issues. The only category of agreement (instruction) contained specific roles; the two roles assigned to special education teachers were focused on providing special services (instructional materials adaptations and pullout services) while the general education teacher roles were assigned to the general group of students which was the work of the general educator. This assignment of roles for general education implies that the special educator is only limited to work with SWDs, not having any input for the rest of students inside the classroom, which is really the opposite of collaboration. It may be noted that the collaborative environment is a two-way model, which involves a shared responsibility by both teachers and not one only.

Additionally, it appears as though role assumptions are not well defined, which could result in differing viewpoints for both teachers. The disagreements in the three areas of planning, evaluation, and behavior management suggest a discrepancy in the understanding of the different roles between general and special education teachers and a lack of preparation or knowledge of the duties assigned to each instructor. Teacher preparation programs prepare general and special education teachers to work with all students despite being with or without a disability providing services and proper education, but it still does not prepare student teachers to work collaboratively with other professionals (Zagona et al., 2017). Although most programs discuss the issue of collaboration, the implementation of the concept is still far short from what is expected. National university programs offered might incorporate courses related to collaboration in the inclusive setting, presenting methods of collaboration, and clarifying the different roles of professionals. The agreement about certain roles (i.e., instruction) denotes some change in the preparation of teachers mainly in the construct of some educational programs in order to adopt to the idea of inclusive education.

The disagreement is presented in the categories of planning, evaluation, and behavior management. This could be distinctly observed when analyzing teacher roles. All responsibilities related to special education teachers had either the words “special education” or “disability,” which directly indicated the work of special education. On the other side, the assignments given to the general educator mainly declared that they were targeted towards all students. The two viewpoints support the work that each teacher is accustomed to doing within the usual educational setting. Nevertheless, collaborative work demands a change in such roles. The involvement of both teachers in roles like the participation in setting the IEP, collaboration in teaching, managing student behaviors, and monitoring progress are important parts of the shared responsibilities within the inclusive environment and not the exclusive work of either teacher.

In a systematic review of teacher collaboration, it was found that the facilitating factors are situated on the level of the process of collaborating. This means that in order to ensure the effectiveness of teacher collaboration, numerous steps can be made to assist various components of the collaborative process, e.g., establishing task interdependence, defining clear roles for participants, and establishing a defined collaborative emphasis (Vangrieken et al., 2015). This shows the depth of collaboration needed inside the classroom to achieve proper collaboration and the need for task interdependence, which is based on the clear roles of both teachers.

Another issue is administrative supervision and support. Research indicates that teacher groups may not always operate as intended. When teacher cooperation is adopted in schools, it should be closely monitored to avoid the emergence of artificial collegiality by ensuring that several preconditions are satisfied (Fulton and Britton, 2011).

Attitudes towards the inclusion of general and special education were also examined. The relation between the success of inclusion and teacher attitudes has been examined widely as a main factor of success that will aid in the proper implementation of collaboration within the school system. General and special education both showed positive attitudes towards inclusion with significant higher averages/positive attitudes for special educators. This outcome is expected especially with special educators’ positive constructs toward students with disabilities and their rights, in addition to other considerations regarding their educational preparation and field training. These results match the work of Engelbrecht and Savolainen (2018), Hernandez et al. (2016), McHatton and Parker (2013), and Moberg (2003). In a longitudinal study by McHatton and Parker (2013) examining the attitudes of general and special education pre-service teachers, it was found that a collaborative course/field experience had a major effect on increasing and producing positive attitudes toward inclusion and collaboration. Furthermore, this trend of positive attitudes progress through student training within an inclusive collaborative environment. Other important factors might affect teachers’ attitudes including teachers’ self-efficacy. Most pre-service special education programs include courses that incorporate principles of inclusion and collaboration in addition to supervised field practicums that include collaborative efforts with other professionals and families. Despite other important factors, teacher preparation programs are one of the most dominating causes affecting the successful implementation of inclusion and the creation of proper collaboration in the general classroom.

This study adds to the research on collaboration between general and special education teachers from their perceptions in inclusive education. Results suggested that both teachers still think about inclusive education from the old perspective of separate services, not as one cohesive unit built on understanding and collaborative work.

Although both teachers have been well prepared to provide proper services for their students, both still embrace and claim their individual roles that they were originally trained for; the concept of shared responsibility is still yet to mature. Teachers’ preparation programs need to address the issue of collaboration actively. Even joint programs can be tailored for teacher preparation in order to enhance better understanding of collaborative teaching and further promote positive attitudes toward inclusion and the collaboration it requires. According to the current preparation paradigm, teachers’ traditional responsibilities and practices will not become more inclusive and teachers’ behaviors cannot be changed without proper inclusive preparation that includes shared responsibilities and the provision of a supportive environment that promotes collaboration. Hence, appropriate inclusive interventions to change the habitual patterns of teacher behavior are needed (Fennick and Liddy, 2001).

It is critical to understand that standard courses alone may not adequately equip teachers to interact with diverse children in their classrooms. As the concept of collaboration becomes evident and applicable in schools, it is important to recognize that the knowledge and skills to apply such a concept and provide others with opportunities for collaboration are not intuitive (Arthaud et al., 2007). These skills must be directly taught through clinical practice and collaborative environments (Friend and Cook, 2013).

The most effective way to acquire skills is to observe and participate in successful collaboration experiences (Pinter et al., 2020). Both general and special education teachers can benefit from ongoing professional development on various collaboration and team models in order to effectively support students with disabilities (Da Fonte and Barton-Arwood, 2017).

Another aspect of support comes from the school administration. It is recommended that school administrators support general and special education teamwork by providing proper supervision and the incorporation of dedicated time slots into the daily planning schedules (Da Fonte and Barton-Arwood, 2017). This scheduled time will help in building rapport among teachers and provide the time to plan, organize, and collaborate effectively.

Further research is required, especially qualitative research, to explore the grounds that hinder proper collaboration and the best methods to overcome. Special education teachers have proven to be better prepared with improved attitudes towards inclusive education, but still the responsibility lying upon them requires an active part in providing awareness and support to all people who work with SWDs.

Finally, inclusive education has proved to be an essential element to provide to all students despite having a disability or not. The benefits achieved have been demonstrated by many. Nevertheless, all recommended practices have to be addressed within the culture context and values.

This study had several limitations. First of all, because this research is directed toward general and special education teachers in the capital of Jordan, Amman, the addition of teachers from other governorates might enrich and provide different perspectives related to collaboration. Also, the need for different perspectives like school administrators and education professionals might add more insight into the nature of collaboration within the inclusive school. Another issue is the different models of collaboration especially between private and public sector schools and their implementation of inclusive practices and collaboration. A final limitation is directly related to the data collection method, where qualitative methodology is needed to further explore the different aspects of collaboration including the situational analysis of collaboration and its barriers.

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the School of Educational Sciences Research Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We would like to extend our gratitude to all the teachers who participated in the study. We would like to acknowledge Ellen Fennick for her guidance and for sharing her information freely.

Able, H., Sreckovic, M. A., Schultz, T. R., Garwood, J. D., and Sherman, J. (2015). Views from the Trenches. Teach. Edu. Spec. Edu. 38 (1), 44–57. doi:10.1177/0888406414558096

Ahsan, M. T., Sharma, U., and Deppeler, J. M. (2012). Exploring Pre-service Teachers' Perceived Teaching-Efficacy, Attitudes and Concerns about Inclusive Education in Bangladesh. Int. J. whole schooling 8 (2), 1–20. doi:10.1080/0305764x.2013.8340

Aiello, P., Pace, E. M., Dimitrov, D. M., and Sibilio, M. (2017). A Study on the Perceptions and Efficacy towards Inclusive Practices of Teacher Trainees. Ital. J. Educ. Res. 19, 13–28.

Alghazo, E. M., and Naggar Gaad, E. E. (2004). General Education Teachers in the United Arab Emirates and Their Acceptance of the Inclusion of Students with Disabilities. Br. J. Spec. Edu. 31 (2), 94–99. doi:10.1111/j.0952-3383.2004.00335.x

Alquraini, T. A. (2012). Factors Related to Teachers' Attitudes towards the Inclusive Education of Students with Severe Intellectual Disabilities in Riyadh, Saudi. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 12 (3), 170–182. doi:10.1111/j.1471-3802.2012.01248.x

Alzahrani, N. (2020). The Development of Inclusive Education Practice: A Review of Literature. INT-JECSE 12 (1), 100. doi:10.20489/intjecse.722380

Arthaud, T. J., Aram, R. J., Breck, S. E., Doelling, J. E., and Bushrow, K. M. (2007). Developing Collaboration Skills in Pre-service Teachers: A Partnership between General and Special Education. Teach. Edu. Spec. Edu. 30 (1), 1–12. doi:10.1177/088840640703000101

Callado Moreno, J. A., Molina Jaén, M. D., Pérez Navío, E., and Rodríguez Moreno, J. (2015). Inclusive Education in Schools in Rural Areas. N.Appr.Ed.R 4 (2), 107–114. doi:10.7821/naer.2015.4.120

Carlson, E., Brauen, M., Klein, S., Schroll, K., and Willig, S. (2002). Study of Personnel Needs in Special Education, 20. Rockville, MD: Westat Research Corporation. Retrieved February, 2004.

CEC (2021). Initial Special Education Preparation Standards. USA: Council for Exceptional Children. Available at: https://exceptionalchildren.org/standards/initial-special-education-preparation-standards.

Chitiyo, J. (2017). Challenges to the Use of Co-teaching by Teachers. Int. J. whole schooling 13 (3), 55–66.

Conderman, G., and Johnston-Rodriguez, S. (2009). Beginning Teachers' Views of Their Collaborative Roles. Preventing Sch. Fail. Altern. Edu. Child. Youth 53 (4), 235–244. doi:10.3200/psfl.53.4.235-244

Conderman, G., and Stephens, J. T. (2000). Voices from the Field: Reflections from Beginning Special Educators. Teach. Exceptional Child. 33 (1), 16–21. doi:10.1177/004005990003300103

Council for the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. 2007. Council for the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Available at: http://hcd.gov.jo/sites/default/files/English%20version.pdf

Da Fonte, M. A., and Barton-Arwood, S. M. (2017). Collaboration of General and Special Education Teachers: Perspectives and Strategies. Intervention Sch. Clinic 53 (2), 99–106. doi:10.1177/1053451217693370

De Boer, A., Pijl, S. J., and Minnaert, A. (2011). Regular Primary Schoolteachers' Attitudes towards Inclusive Education: a Review of the Literature. Int. J. inclusive Educ. 15 (3), 331–353. doi:10.1080/13603110903030089

Education, E. A. f. D. i. S. N. (2003). Key Principles for Special Needs Education: Recommendations for Policy Makers. Retrieved from website: Available at: http://www.european-agency.org/publications/ereports/key-principles-in-special-needs-education/keyp-en.pdf

Education, M. o. (2018). The 10-Year Strategy for Inclusive Education. Jordan: Amman. The Higher Council of Persons with Disability.

Education, S. W. C. o. S. N. (1994). World Conference on Special Needs Education: Access and Quality. Salamanca, Spain: Unesco, 7–10. June 1994.

Engelbrecht, P., and Savolainen, H. (2018). A Mixed-Methods Approach to Developing an Understanding of Teachers’ Attitudes and Their Enactment of Inclusive Education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Edu. 33 (5), 660–676.

Fennick, E. (1995). General Education and Special Education Teachers' Perceived Responsibilities and Preparation for Collaborative Teaching. USA: The University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Fennick, E., and Liddy, D. (2001). Responsibilities and Preparation for Collaborative Teaching: Co-teachers' Perspectives. Teach. Edu. Spec. Edu. 24 (3), 229–240. doi:10.1177/088840640102400307

Forlin, C., Cedillo, I. G., Romero‐Contreras, S., Fletcher, T., and Rodríguez Hernández, H. J. (2010). Inclusion in Mexico: Ensuring Supportive Attitudes by Newly Graduated Teachers. Int. J. inclusive Educ. 14 (7), 723–739. doi:10.1080/13603111003778569

Friend, M., and Cook, L. (2013). Interactions: Collaboration Skills for School Professionals. 7th edition. USA: Pearson.

Fulton, K., and Britton, T. (2011). STEM Teachers in Professional Learning Communities: From Good Teachers to Great Teaching. USA: National Commission on Teaching and America's Future.

Gaad, E., and Khan, L. (2007). Primary Mainstream Teachers' Attitudes towards Inclusion of Students with Special Educational Needs in the Private Sector: A Perspective from Dubai. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 22 (2), 95–109.

Garrote, G. (2017). Relationship between the Social Participation and Social Skills of Pupils with an Intellectual Disability: A Study in Inclusive Classrooms. Flr 5 (1), 1–15. doi:10.14786/flr.v5i1.266

Hadidi, M. S. Z. (1998). Educational Programs for Children with Special Needs in Jordan. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 23 (2), 147–154. doi:10.1080/13668259800033651

Hammond, H., and Ingalls, L. (2003). Teachers' Attitudes toward Inclusion: Survey Results from Elementary School Teachers in Three Southwestern Rural School Districts. Rural Spec. Edu. Q. 22 (2), 24–30. doi:10.1177/875687050302200204

Hansen, J. H., Carrington, S., Jensen, C. R., Molbæk, M., and Secher Schmidt, M. C. (2020). The Collaborative Practice of Inclusion and Exclusion. Nordic J. Stud. Educ. Pol. 6 (1), 47–57. doi:10.1080/20020317.2020.1730112

Hernandez, D. A., Hueck, S., and Charley, C. (2016). General Education and Special Education Teachers' Attitudes towards Inclusion. J. Am. Acad. Spec. Edu. Professionals 79, 93.

Hornby, G. (2015). Inclusive Special Education: Development of a New Theory for the Education of Children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities. Br. J. Spec. Edu. 42 (3), 234–256. doi:10.1111/1467-8578.12101

Johnson, C., and Edge, C. (2012). How Does the Co-teaching Model Influence Teaching and Learning in the Secondary classroomUnpublished Master's Thesis). Marquette: Northern Michigan University.

Johnson, D. W., and Johnson, R. T. (2009). An Educational Psychology success story: Social Interdependence Theory and Cooperative Learning. Educ. Res. 38 (5), 365–379. doi:10.3102/0013189x09339057

Johnson, D. W., and Johnson, R. T. (1989). Cooperation and Competition: Theory and Practice. USA: International Book Company.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., and Smith, K. A. (2014). Cooperative Learning: Improving university Instruction by Basing Practice on Validated Theory. J. Excell. Univ. Teach. 25 (4), 1–26.

Kim, J. R. (2011). Influence of Teacher Preparation Programmes on Preservice Teachers' Attitudes toward Inclusion. Int. J. inclusive Educ. 15 (3), 355–377. doi:10.1080/13603110903030097

Lamar-Dukes, P., and Dukes, C. (2005). Consider the Roles and Responsibilities of the Inclusion Support Teacher. Intervention Sch. Clinic 41 (1), 55–61. doi:10.1177/10534512050410011501

Lambe, J., and Bones, R. (2006). Student Teachers' Perceptions about Inclusive Classroom Teaching in Northern Ireland Prior to Teaching Practice Experience. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Edu. 21 (2), 167–186. doi:10.1080/08856250600600828

Liasidou, A., and Antoniou, A. (2013). A Special Teacher for a Special Child? (Re)considering the Role of the Special Education Teacher within the Context of an Inclusive Education Reform Agenda. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Edu. 28 (4), 494–506. doi:10.1080/08856257.2013.820484

Lyons, W. E., Thompson, S. A., and Timmons, V. (2016). 'We Are Inclusive. We Are a Team. Let's Just Do it': Commitment, Collective Efficacy, and agency in Four Inclusive Schools. Int. J. Inclusive Edu. 20 (8), 889–907. doi:10.1080/13603116.2015.1122841

Mackey, M. (2014). Inclusive Education in the United States: Middle School General Education Teachers' Approaches to Inclusion. Int. J. Instruction 7 (2), 5–20.

Malinen, O.-P., and Savolainen, H. (2016). The Effect of Perceived School Climate and Teacher Efficacy in Behavior Management on Job Satisfaction and Burnout: A Longitudinal Study. Teach. Teach. Educ. 60, 144–152. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2016.08.012

McCray, E. D., and McHatton, P. A. (2011). Less Afraid to Have Them in My Classroom": Understanding Pre-service General Educators' Preceptions about Inclusion. Teach. Edu. Q. 38 (4), 135–155.

McHatton, P. A., and Parker, A. (2013). Purposeful Preparation. Teach. Edu. Spec. Edu. 36 (3), 186–203. doi:10.1177/0888406413491611

McLeskey, J., Waldron, N. L., Spooner, F., and Algozzine, B. (2014). “What Are Effective Inclusive Schools and Why Are They Important,” in Handbook of Effective Inclusive Schools (USA: Routledge), 13–26.

Moberg, S. (2003). Education for All in the North and the South: Teachers' Attitudes towards Inclusive Education in Finland and Zambia. Education Train. Dev. Disabilities, 417–428.

Mulholland, M., and O'Connor, U. (2016). Collaborative Classroom Practice for Inclusion: Perspectives of Classroom Teachers and Learning Support/resource Teachers. Int. J. inclusive Educ. 20 (10), 1070–1083. doi:10.1080/13603116.2016.1145266

Pinter, H. H., Bloom, L. A., Rush, C. B., and Sastre, C. (2020). “Best Practices in Teacher Preparation for Inclusive Education,” in Handbook of Research on Innovative Pedagogies and Best Practices in Teacher Education (USA: IGI Global), 52–68. Best Practices in Teacher Preparation for Inclusive Education doi:10.4018/978-1-5225-9232-7.ch004

Potter, C. (2015). 'I Didn't Used to Have Much Friends': Exploring the friendship Concepts and Capabilities of a Boy with Autism and Severe Learning Disabilities. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 43 (3), 208–218. doi:10.1111/bld.12098

Schnepel, S., Krähenmann, H., Sermier Dessemontet, R., and Moser Opitz, E. (2020). The Mathematical Progress of Students with an Intellectual Disability in Inclusive Classrooms: Results of a Longitudinal Study. Math. Ed. Res. J. 32 (1), 103–119. doi:10.1007/s13394-019-00295-w

Shade, R. A., and Stewart, R. (2001). General Education and Special Education Preservice Teachers' Attitudes toward Inclusion. Preventing Sch. Fail. Altern. Edu. Child. Youth 46 (1), 37–41. doi:10.1080/10459880109603342

Slavin, R. E. (2011). Instruction Based on Cooperative Learning. Handbook Res. Learn. instruction, 358–374. doi:10.4324/9780203839089-26

Smogorzewska, J., Szumski, G., and Grygiel, P. (2019). Theory of Mind Development in School Environment: A Case of Children with Mild Intellectual Disability Learning in Inclusive and Special Education Classrooms. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 32 (5), 1241–1254. doi:10.1111/jar.12616

Snipstad, Ø. I. M. (2019). Democracy or Fellowship and Participation with Peers: what Constitutes One's Choice to Self-Segregate. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Edu. 34 (3), 355–368. doi:10.1080/08856257.2018.1520493

Solis, M., Vaughn, S., Swanson, E., and Mcculley, L. (2012). Collaborative Models of Instruction: The Empirical Foundations of Inclusion and Co-teaching. Psychol. Schs. 49 (5), 498–510. doi:10.1002/pits.21606

Swain, K. D., Nordness, P. D., and Leader-Janssen, E. M. (2012). Changes in Preservice Teacher Attitudes toward Inclusion. Preventing Sch. Fail. Altern. Edu. Child. Youth 56 (2), 75–81. doi:10.1080/1045988x.2011.565386

Szumski, G., and Karwowski, M. (2015). Emotional and Social Integration and the Big-Fish-Little-Pond Effect Among Students with and without Disabilities. Learn. Individual Differences 43, 63–74. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2015.08.037

Taylor, R. W., and Ringlaben, R. P. (2012). Impacting Pre-service Teachers' Attitudes toward Inclusion. Higher Edu. Stud. 2 (3), 16–23. doi:10.5539/hes.v2n3p16

Tiwari, A., Das, A., and Sharma, M. (2015). Inclusive Education a «rhetoric» or «reality». Teachers' Perspectives.

Tran, V. D. (2013). Theoretical Perspectives Underlying the Application of Cooperative Learning in Classrooms. Int. J. Higher Edu. 2 (4), 101–115. doi:10.5430/ijhe.v2n4p101

Van Hove, G. (2015). Learning to Read in Regular and Special Schools: A Follow up Study of Students with Down Syndrome. Life Span Disabil. 18 (1), 7–39.

Vangrieken, K., Dochy, F., Raes, E., and Kyndt, E. (2015). Teacher Collaboration: A Systematic Review. Educ. Res. Rev. 15, 17–40. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2015.04.002

Vieluf, S., Kunter, M., and Van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2013). Teacher Self-Efficacy in Cross-National Perspective. Teach. Teach. Educ. 35, 92–103. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2013.05.006

Villa, R. A., Thousand, J. S., Meyers, H., and Nevin, A. (1996). Teacher and Administrator Perceptions of Heterogeneous Education. Exceptional Child. 63 (1), 29–45. doi:10.1177/001440299606300103

Zagona, A. L., Kurth, J. A., and MacFarland, S. Z. C. (2017). Teachers' Views of Their Preparation for Inclusive Education and Collaboration. Teach. Edu. Spec. Edu. 40 (3), 163–178. doi:10.1177/0888406417692969

Keywords: perceptions, attitudes, collaboration, inclusive education, general and special education teachers

Citation: Alabdallat B, Alkhamra H and Alkhamra R (2021) Special Education and General Education Teacher Perceptions of Collaborative Teaching Responsibilities and Attitudes Towards an Inclusive Environment in Jordan. Front. Educ. 6:739384. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.739384

Received: 10 July 2021; Accepted: 18 November 2021;

Published: 20 December 2021.

Edited by:

Vasilis Strogilos, University of Southampton, United KingdomReviewed by:

Kerstin Göransson, Karlstad University, SwedenCopyright © 2021 Alabdallat, Alkhamra and Alkhamra. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hatem Alkhamra, aC5hbGtoYW1yYUBqdS5lZHUuam8=

†ORCID: Hatem Alkhamra, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6240-4316

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.