- Department of Pharmacy, Kingston University London, Surrey, United Kingdom

An effective Personal Tutoring Scheme (PTS) is a crucial part of the strategy to support students’ progression and success rates in Higher Education institutions. This study investigated students’ expectations and perceptions of the PTS in a post-1992 university in the UK. Data collection was achieved through a survey completed by 1,078 students from all Faculties and was used to assess trends and factors affecting students’ expectations and perceptions of the PTS. Results indicated that there is a gap between students’ expectations and perceptions, but that in comparison to previous literature this gap seems to be reducing. Unsurprisingly, frequency and regularity of meetings are linked with the development of a relationship with the Personal Tutor (PT) and a higher level of satisfaction. Higher Education institutions still have further work to do to close the gap between students’ expectations and perceptions; however, the results of this study indicate that this work is currently being undertaken.

Introduction

In recent years there has been an increasing pressure on Higher Education (HE) institutions to ensure student retention (Tight, 2019) and, more generally, to enhance the student experience. These pressure points have various sources including the growing numbers of students and the increased diversity of the student body. Additionally, the large fee cap rise during the last decade (Bates and Kaye, 2014) led students, and families, to make a larger investment when they enter HE; they therefore seek a low risk return, i.e. a university with low drop-out rates (Simpson, 2006).

Another factor contributing to attrition rates is the mental health of students. A large-scale study was conducted in the UK in 2018, which assessed the prevalence of mental health disorders in students (Pereira, et al., 2019). Results showed that more than one in five students had a diagnosed mental health disorder; and one in three had experienced a serious psychological issue for which they needed professional help (Pereira, et al., 2019). Mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety, can affect students’ academic work (Gorczynski et al., 2017). The concerns regarding the mental well-being and health of university students have grown more serious due to the social distancing and the remote working during the SARS-Covid-19 pandemic (Defeyter et al., 2021). Without the right support systems in place, university students are more likely to withdraw from their course. Studies strongly support the ability of the relationship between the Personal Tutor (PT) and student to positively influence the student experience, which subsequently improves student retention (Yale, 2019).

For these reasons it has become essential for HE institutions in the UK to invest in developing and maintaining a high-quality Personal Tutoring Scheme (PTS) (Simpson, 2006). Having a well-established PTS embedded in the institutions’ policies ensures that students feel seen and supported (Owen, 2002). A key scope of the PTS is also fostering a sense of belonging and evidence suggests this is the most important factor related to student retention in HE (McFarlane, 2016; Grey and Osborne, 2018).

There is a limited body of literature on the topic of PTS in HE in the UK (Lochtie et al., 2018), especially of studies pertaining to students’ perspective and expectations of the PTS (Braine and Parnell, 2011).

Background

In 1996, The Higher Education Quality Council for England (HEQC) emphasized the need for student support in the form of PTs within HE due to the massification of the student body (Owen, 2002). In 2002, the Department for Education and Skills made it their target to ensure the retention of more students within HE (Wilcox et al., 2005). The large fee cap increase from £3,000 to £9,000 in 2012 sparked much discussion and change in HE, resulting in a shift in focus to ensure a more personalized learning experience for students (Lochtie et al., 2018). The introduction of the Office for Students (OfS) and the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) by the Higher Education and Research Act (2017), which focus on student retention and satisfaction (Lochtie et al., 2018), puts further pressure on HE institutions to ensure a high-quality university experience for all students.

Higher Education Services and Students’ Satisfaction

There are a number of services that are offered by universities that can affect the students’ satisfaction including physical/facilitating goods, explicit services and implicit services. Lectures, tutorials, presentation slides and Supplementary Materials are amongst the facilitating goods while the staff experience, teaching ability and knowledge are examples of explicit services. Implicit services include staff friendliness, availability, approachability and care for students (Douglas et al., 2006). The foundation of the PTS is based on the implicit services and can have an impact on the students’ satisfaction. Quality of Higher Education is based on the students’ perception of the overall service they receive during their course time Hill (1995). Perception about a service or a product is strongly linked to satisfaction and loyalty of the customers towards this service or product Browne et al. (1998) and Guolla (1999).

There are a number of tools that are used to measure satisfaction. SERVQUAL scale is a tool that was developed by Parasuramanet al. (1988). Parasuramanet defined the service quality “as a form of attitude, related but not equivalent to satisfaction, and results from comparison of expectations with perceptions of performance”. In other words, the difference between what the student is expecting to receive and what the student actually receives will define the quality of the course for this student. Therefore, the level of student’s satisfaction is shaped by the gap between what the student expects and what perceives. Sherry et al. (2004) used SERVQUAL scale to assess the perception of business students of the services provided by New Zealand Tertiary institute. A questionnaire made of 20 questions that covered 5 dimensions; Tangibles, Reliability, Responsiveness, Assurance and Empathy was used. Using SERVQUAL scale have showed that there was a significance difference between students’ expectation and perceptions. Also, the perceptions between international and local students services were different, with international students having a lower perception compared to local.

The Importance of Personal Tutoring Schemes

It is well documented that undergraduates face many challenges, which may lead to withdrawal from their course. Therefore, a functional PTS providing suitable support is necessary to assist with retaining students (Braine and Parnell, 2011), especially in the current competitive economic market. HE institutions invest considerable resources on marketing and it is therefore in their best interest to ensure that students are happy, successful and retained (Owen, 2002). Additionally, there is a moral responsibility of providing students with academic as well as pastoral support, due to transitioning into HE being a major life change and a considerable commitment of 3 years or more (Owen, 2002). A PTS ensures that students have access to the wide range of other support services provided by the institution (such as finance, mental health and disability support, careers advice, etc.) and that their academic progress and personal development are tracked by a staff member (Braine and Parnell, 2011; Small, 2013).

The Multifaceted Role of a Personal Tutor

It is important for HE institutions to acknowledge that personal and external factors have a direct impact on students’ academic performance and therefore students require pastoral and academic support (Braine and Parnell, 2011; Small, 2013). The PT has a multifaceted role and, over the years, the literature has suggested some examples of roles: providing advice and support on academic matters as well as pastoral care in terms of listening, giving advice, and solving problems on personal issues; encouraging and supporting student’s personal development; acting as a link between the university and the student, facilitating a sense of belonging for the student; referring students to appropriate university services; building rapport with the student and creating a friendship; and helping students build employability skills and give advice on career progression. (Malik, 2000; Braine and Parnell, 2011; Small, 2013; Ross et al., 2014; Lochtie et al., 2018). PTs also play a key role in the social integration of students into HE institutions (Wilcox et al., 2005). This is especially important in the first year of study because transition into HE is complex (Chanock et al., 2012) and can cause emotional difficulties for students (Small, 2013).

The first year of study is a crucial point for the PTS, especially because it has been documented that the highest drop-out rate is within the first year of study (Owen, 2002). The transition into HE is incredibly stressful; this is particularly due to the number of changes that students go through in a short period of time. Many students leave their family homes to live closer to their chosen institution; they must therefore deal with taking care of themselves (possibly for the first time), learning to navigate a new city and having less physical support from their families. The institution itself is a whole new environment with new people (friends and lecturers) from a variety of backgrounds. These big changes can cause much emotional stress; however, developing a supportive relationship with a PT can help the students adapt to their new environment and develop a sense of belonging, thus easing their transition (Chanock et al., 2012; Small, 2013). Forming this positive relationship with a PT in the first year of study has been linked to higher retention rates (Yale, 2017). HE institutions can encourage the formation of this relationship by embedding a compulsory PTS in an accredited module in the first year of study (Foundation and/or Year 1).

Students’ Expectations of a Personal Tutoring Scheme

While there is a consensus on the core values and skills that a PT should possess to be successful (Lochtie et al., 2018), PTs are generally expected to be trustworthy, open, available, knowledgeable, approachable, kind, patient, to mention few attributes (Hughes, 2004). Students generally expect these qualities in their PT; the most important features being support (Small, 2013) and a meaningful relationship with their PT (Malik, 2000; Small, 2013; Ross, et al., 2014). There is compelling evidence from the literature that the key to success of a PTS is the development of a strong PT-student relationship (Malik, 2000; Hughes, 2004; Braine and Parnell, 2011; Small, 2013; Ross, et al., 2014). When students feel supported and develop a friendship with their PT they then choose to meet more frequently with their PT (Small, 2013). Students want to feel that they belong (Ross, et al., 2014; Yale, 2019), are valued and respected (Braine and Parnell, 2011; Ross, et al., 2014). They expect this relationship to have a human side where they are recognised as a person by somebody with genuine interest and compassion (Ross, et al., 2014); somebody they can trust and have a genuine rapport with (Braine and Parnell, 2011; Ross, et al., 2014). The timing and regularity of the contact are also important contributing factors to the success of building this relationship (Ross, et al., 2014; Yale, 2019). Additionally, students have also been reported to prefer having their PT as a lecturer to get familiar with them in other ways (Owen, 2002). Some students have reported to feel more comfortable approaching their PT if they know them from lectures and that routine meetings with their PT and having the same PT throughout their time at university would be a great advantage (Owen, 2002). These are important points, which we explored to a further extent in this work. We argue the creation of a relationship between the student and the PT is as important as fragile; any attempt to embed the PTS in the taught material, for example by means of getting PTs to mark their own tutees work is risky and could be counterproductive.

Two of the most important characteristics of a PT are approachability and availability (Braine and Parnell, 2011) as these are vital to building a meaningful relationship (Owen, 2002). However, it has been found that students are more likely to approach their PT with academic rather than pastoral issues; this is especially true if the PT marks their assessments (Small, 2013). In a study conducted by Malik (2000) nearly half of the students stated that personal challenges were affecting their academic work, but they were unlikely to approach a PT regarding these issues. Certain students are reluctant to approach their PT because they perceive them as too busy and unavailable (Yale, 2019); they worry they will burden the PTs who already have heavy workloads (Owen, 2002). Students also express concern as to whether their PT is friendly (Yale, 2019).

This investigation aimed at evaluating the students’ expectations and perceptions of the current PTS at a post-1992 university in the UK. Analysis of trends and evaluation of various factors contributing to the expectations and perceptions of students was carried out. The overarching research question is: “are students’ expectations matched by the experienced level of provided support?”. In the light of the previously describe literature, we explore the potential existence of such a gap by evaluating different parameters that have been linked to satisfaction, retention, engagement and belonging. These aspects include characteristics of the PTs, the number frequency of meetings, whether PTs should be directly involved in summative assessments/marking, and general demographic data, including nature of course and level of studies.

Methodology

Research Tool and Study Design

In order to obtain information about the students’ expectations and perceptions of the PTS, a quantitative approach of data collection was undertaken. A survey was created using SurveyMonkey® online Supplementary Appendix S1, which contained 23 questions including 14 closed-ended questions, 8 combination questions (with a variable that allowed the students to elaborate), one open-ended question and an additional comments section. Therefore, the study was, by design, of a quantitative nature and little qualitative information was collected.

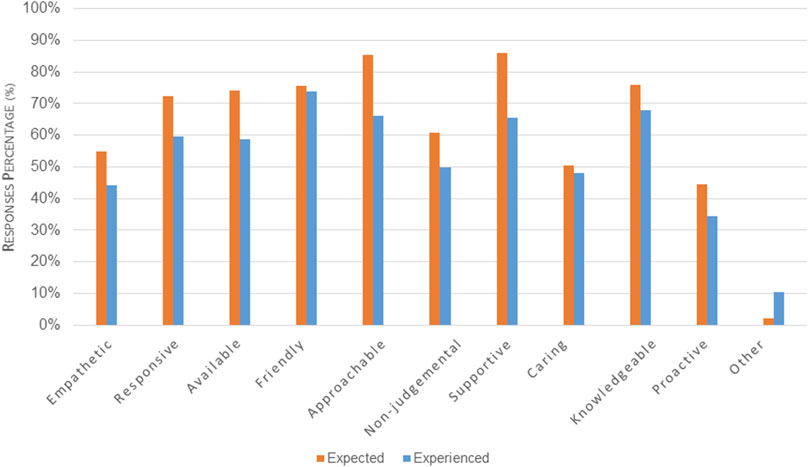

In order to identify the gap between students’ perceptions and expectation about the PT characteristics, a SERVQUAL model was used. One question asked about the expected characteristics of the PT while another question asked about the student’s experience with the characteristic of the allocated PT. PT’s characteristic included empathy, responsiveness, availability, friendliness, approachability, being non-judgemental, supportive, caring, knowledgeable and proactive.

In order to assess the perceptions of the students about the PTS, Likert scale questions were used to ask about the trust they built with their personal tutor, level of support from the PT, help they get from the PT to develop employability skills, transferable skills and CV.

To explore if students’ demographics play a role on their perceptions, the last section of the survey was designed to collate information about the students’ ethnicity, age, gender, entry qualifications, course and level of study.

The survey results were collected between 15 April and June 19, 2020. This survey was reviewed and approved by the Ethics committee of the same post-1992 institution.

Participants

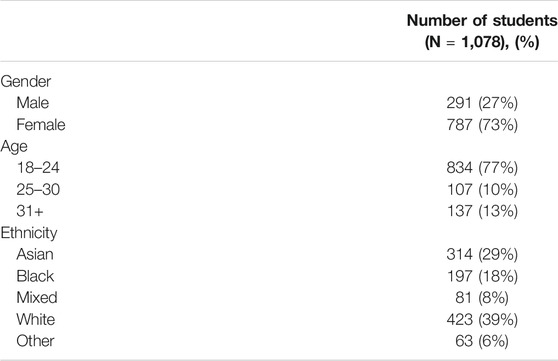

The survey was sent to 1,350 students in all faculties and 1,078 students completed and returned it, giving a response rate of 79.9%. Participation in the survey was anonymous and voluntary. The demographics of the students who completed the survey are displayed in Table 1.

Data Analysis

The data was analysed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics. Chi-square test of independence was used to evaluate statistical significance between cross-tabbed results. Independent samples T-tests were used to compare the mean Likert scale scores between two independent groups. One-way ANOVA tests were used to compare mean Likert scale scores between more than two independent groups. Kruskal-Wallis H tests were used to evaluate qualitative data more meaningfully by converting it to numerical format. A 95% confidence interval was used for all analyses.

Results

Frequency and Nature the Personal Tutor Meeting

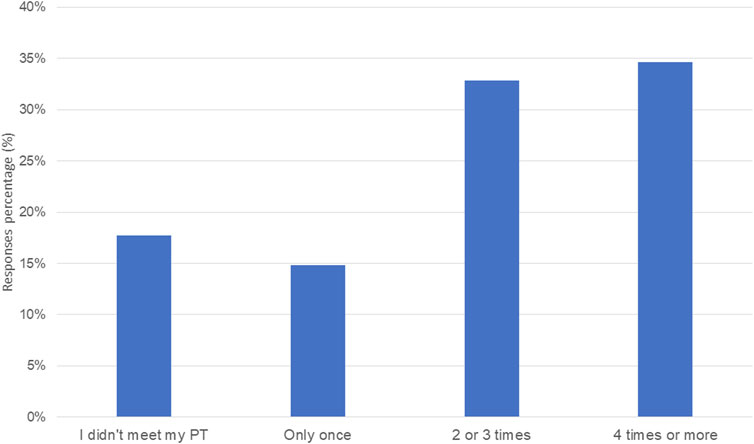

A strong PT-student relationship is linked to frequent and regular meetings (Malik, 2000). Figure 1 shows that majority of the surveyed students (67.4%; n = 727) have met at least 2 times with their personal tutor. Around 30% of the students did not meet with their PT or met only once.

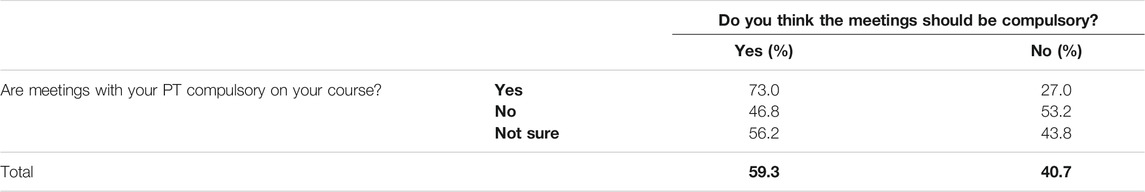

In order to assess students’ overall satisfaction with the PTS based on the compulsory nature of the PT meetings, a Likert scale showed that the mean score for students who had compulsory meetings was significantly higher than those who selected “no” or “not sure”, thus demonstrating compulsory meetings lead to more satisfied students. Possibly by formalising the PTS into a compulsory module, students are more likely to understand the value of the PTS and reap the benefits of having a PT, leading to improved satisfaction with the PTS.

Following from this, it was found the majority of the students (59.3%, n = 639) believed that meetings with their PT should be compulsory. When cross-analysing this finding with whether the PT meetings were compulsory it was observed that students tend to stick with what they know based on their experiences (Table 2). Most students who had compulsory PT meetings agreed that meetings should be compulsory (73.0%; n = 279), whereas students who did not have compulsory meetings were more likely to agree that compulsory meetings were unnecessary (53.2%; n = 176).

TABLE 2. Cross-analysis to explore students’ preferences regarding whether PTS meetings should be compulsory.

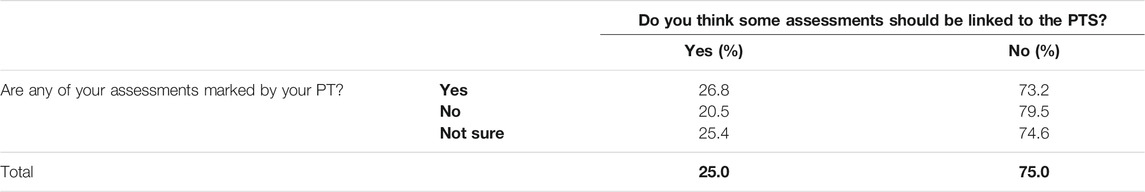

As the involvement of PTs in the marking of assessments has been implemented in some institutions. This approach was explored in our study and the student surveyed were asked if any of their assessments are marked by their PTs and if they think some assessments should be linked to the PTS. From data shown in Table 3, it is clear that most students (75%; n = 808) did not wish to have assessments linked to the PTS. The majority of the students (73.2%; n = 398), whose assessments are marked by their PT, also did not want assessments linked to the PTS.

TABLE 3. Cross-analysis of questions regarding assessments linked to the Personal Tutoring Scheme (PTS).

In this study, students’ preferences regarding the type of meeting were also explored. One-to-one meetings were preferred by most students (56.6%; n = 610), group meetings were preferred by 18.4% (n = 198) of students whereas 25.0% (n = 270) of students had no preference.

Does Demographics Affect Engagement With the PTS?

Demographics can often have an impact on expectations and perceptions. Therefore, this data was cross-analysed with frequency of meetings and the Likert scale to establish engagement and satisfaction with the PTS based on level and course of study, gender, age, ethnicity, and disability.

Figure 2A represents the students’ population according to level of studies. Majority of the surveyed students were at year 1 and 2 (Figure 2A). Some interesting trends arose when analysis was carried out to determine the relationship between students’ level of study and the frequency of PT meetings during the academic year (Figure 2B). A Kruskal-Wallis H test showed that as students move up in level they meet more frequently with their PT. However, Year 1 is the exception to this trend: Year 1 students meet with their PT more frequently than Years 2–4.

FIGURE 2. Percentage of students in each level of study at the post-1992 university (A), frequency of meetings with a Personal Tutor (PT) based on level of study (B), Compulsory nature of PT meetings per level of study (C).

Further analysis was undertaken to understand this exception, and it was found that 42.2% (n = 152) of Year 1 students answered “Yes,” to “Are meetings with your personal tutor compulsory on your course?” whereas the students at other levels of study had substantially lower numbers answering “Yes” to the same question (Figure 2C).

Despite definitively knowing that PT meetings were not compulsory, most of these students (71.9%, n = 238) still met with their PT at least once. This was also the case of students who were unsure (78.4%, n = 286). This is a significant majority and indicates that the University is effectively communicating with the students about the PTS.

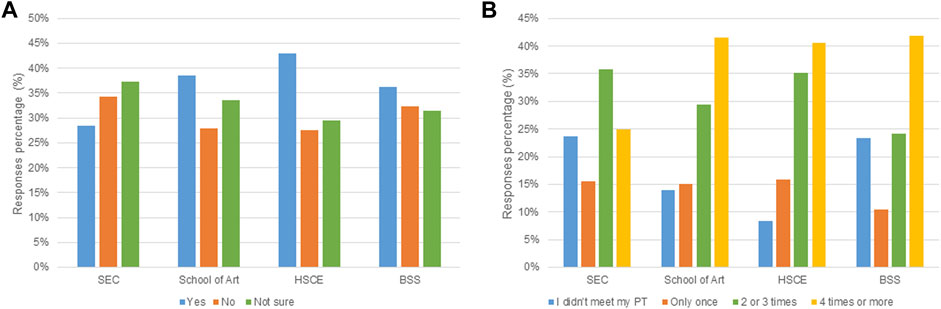

Analysis was conducted to explore potential differences in engagement with the PTS based on faculty/course studied. From Figure 3A it can be observed that the Science, Engineering and Computing (SEC) faculty had the lowest student engagement with the PTS compared to the school of art or faculty of Business and Social Sciences (BSS). This was confirmed by a Kruskal-Wallis H test (Appendix L2) which indicated that students in SEC had a significantly lower engagement with the PTS compared with the other three faculties. To explore this dynamic further, the faculties were cross-tabbed with the compulsory nature of the PTS (Figure 3B), and it was found that fewer students in SEC had compulsory PT meetings. HSCE (Health, Social Care and Education) students had the highest percentage (43.0%; n = 108) of students having compulsory PT meetings (Figure 3B); and correspondingly had the highest Kruskal-Wallis H test score for frequency of PT meetings.

FIGURE 3. Frequency of meetings with a Personal Tutor (PT) based on Faculty/course group (A), Compulsory nature of Personal Tutor (PT) meetings per Faculty/course group (B).

Expectations vs. Experience

To assess this gap students were asked which characteristics they expected in a PT and which characteristics best described their PT. The characteristics investigated were “empathetic, responsive, available, friendly, approachable, non-judgmental, supportive, caring, knowledgeable, and proactive”. Students could select as many variables as applied. They also had the opportunity to add characteristics of their choice they expected and experienced. Figure 4 represents the Differences between the characteristics students expected and what they experienced in their PT were identified in this study and are shown in Figure 4, which clearly shows students had higher expectations of their PTs compared with what they experienced. This difference was especially significant for expectations of supportiveness (20.5% difference), approachability (19.4% difference), and availability (15.6% difference) of PTs.

FIGURE 4. Characteristics of a Personal Tutor (PT) that students expected compared with what they experienced.

Discussion

It is well documented that undergraduates face many challenges which may lead to withdrawal from their elected course. Therefore, a functional PTS providing suitable support is necessary to assist with retaining students (Braine and Parnell, 2011). HE institutions have invested in developing PTS to provide both academic and pastoral support to the students (Owen, 2002). The post-1992 university runs a PTS and use different channels to communicate the scheme to the new and current students.

Around 46.0% (n = 496) of the surveyed students knew about the PTS in the early days of their course as it was introduced to them during Induction (week 0). While 21.3% (n = 230) being contacted and informed by their assigned PT and 16.3% 176) reading about it on the university portal. However, 9.1% (n = 98) of students selected “Other”, to which they had to specify.

Most of the qualitative responses to “Other” were that students did not know about the PTS and that they had a PT until they received the survey. One student included the following statement:

“The personal tutoring scheme was non-existent throughout the course until 3rd year. 2nd year a tutor did email me but I didn’t know who it was and I never ended up meeting them. I wasn’t sure what they were meant to do either."

Early communication about the PTS and its usefulness to every student is essential; however, a proactive PT also goes a long way to aid communication of the PTS and inevitably facilitates the overall success of the PTS. Some students felt uncomfortable in approaching their PTs and believed that the PT should initiate contact. There is a direct link between PTs being proactive and the success of the PTS (Malik, 2000). PTs who seek out their tutees and actively invite them to social and academic activities help students to foster a sense of belonging, build a relationship, and aid progression (Malik, 2000).

Universities and HE providers expect students to engage in the PTS because of the level of support they receive and to enable them to reap the benefits of the scheme. In the current study, majority of surveyed students (67.4%; n = 727) had met with their PT on two or more occasions during the academic year (Figure 2); this is an encouraging finding, despite the concerning 17.7% (n = 191) reporting to not have met with their PT. As evident from qualitative analysis of responses, either students were not aware of the PTS or felt uncomfortable making initial contact and expected the PT to contact them. There are also concerns regarding the minority of students who met with their PT once (14.8%; n = 160). After an initial meeting the students might have expected that it is the PT’s responsibility to arrange follow-up meetings (Malik, 2000). Another possibility is that after the first meeting the student was unhappy with their PT (perhaps they did not display the characteristics that they expected) and therefore did not initiate any further contact. A solution for low engagement is a proactive PT–which is often what students expect.

In terms of the type of meeting with the PTs, majority of the surveyed students (56.6%; n = 610) preferred one-to-one meeting, over group meetings which were selected by 18.4% (n = 198) of students. Interestingly, it was found that males (63.6%; n = 185) especially preferred one-to-one meetings when compared with females (54.0%; n = 425).

Despite a low number of students (18.4%; n = 198) preferring group meetings, there are several advantages to having group tutorials. Group tutorial sessions allow students to form friendships with each other and develop a network (Braine and Parnell, 2011; Small, 2013). Having friends and a good network enhances the feeling of supportiveness in HE, which in turn cultivates a sense of belonging (Braine and Parnell, 2011; Small, 2013).

The transition into HE is a stressful time for students and developing a relationship with someone who works at the institution can go a long way help foster a sense of belonging (Small, 2013). Students may not automatically associate the PTS with a smoother transition into HE. It would therefore be of benefit to have compulsory PT meetings in the first year of study whereby the institution can demonstrate the benefits of the PTS and aid student transition. This was adopted as a strategy by some departments at this post-1992 institution, as demonstrated by the higher rate of compulsory PT meetings in Year 1. However, a lack of analogous activities was observed in the Foundation level with far fewer students having compulsory PT meetings. As a result, a large and concerning number (33.7%; n = 31) of Foundation students have not met with their PT at all. When asked whether meetings with their PT were compulsory, almost half (44.6%, n = 41) of Foundation year students answered “Not sure”, and only 29.3% (n = 27) answered “Yes” compared with 42.2% (n = 152) of Year 1 students (Figure 4). As engagement of Year 1 students with the PTS is being facilitated in certain courses by having compulsory PT meetings, the same approach could be considered for Foundation students in an effort to help ease the burden of transition into HE for these students, in combination with or to make up for the lack of PTS activities embedded in the curriculum.

Students associate assessments with anxiety and fear of failure (Kivunja, 2015) and getting PTs to mark their tutees’ assessments may create unnecessary stress. As the involvement of PTs in the marking of assessments has been explored as a strategy to both reduce marking loads on specific members of staff and to facilitate the creation of the tutor-student relationship, the relationship between assessments being marked by PTs and students’ preferences were explored. The creation of the PT-student relationship requires effort and time; its creation is considered of importance to improve the chances of progression and engagement. The involvement of PTs in the marking/assessment of students work might adversely affect that delicate PT-student relationship, in turn having a detrimental effect on all the positive aspects the PTS aims at creating.

The post-1992 university, which this project was conducted at, is divided into four faculties: Science and Engineering (SEC), Health and Social Care (HSCE), Arts, and Business Studies (BSS). The largest number of respondents were from Science and Engineering (39.8%) whereas Business Studies were at 11.7%. age group, Analysis was conducted to explore potential differences in engagement with the PTS based on subject area of study. A Kruskal-Wallis H test indicated students in science had a significantly lower engagement with the PTS compared with the other three faculties. To explore this dynamic further, the faculties were cross-tabbed with the compulsory nature of the PTS, and it was found that fewer students in science had compulsory PT meetings. Health and Social Science students had the highest percentage (43.0%; n = 108) of students having compulsory PT meetings and correspondingly had the highest Kruskal-Wallis H test score for frequency of PT meetings. This indicates that the nature of the course of studies might affect engagement with the PTS.

A higher number of female participants (73%; n = 787) was observed among the respondents. It was found that a higher percentage of female met more frequently with their PTs than male students. Correspondingly, male students were also more likely to have not met with their PT during the academic year (male: 23.7%; n = 69; female: 15.5%; n = 122). This finding suggests that females are more inclined to seek support than males. However, in terms of overall satisfaction with the PTS, no significant difference between the genders was found (p > 0.05). Interestingly though, a significant difference was found between the two defined genders in terms of preferred meeting types. With male students (63.6%; n = 185) preferring one-to-one meetings significantly more than female students (54.0%; n = 425); as well as fewer male students (13.4%; n = 39) preferring group meetings than female students (20.2%; n = 159). These results may suggest that more males tend to prefer to keep their support needs private.

In terms of the age group, there does appear to be a general trend in the data indicating that mature students are more likely to meet more frequently with their PT. However, the p value is over 0.05, therefore this finding is not significant. A one-way ANOVA was performed to assess if there was any significant difference in satisfaction with the PTS between the different age groups; but no significant difference was found.

In order to evaluate potential differences in ethnicity, two variables were formed based on the definition of BME, i.e. black and minority ethnic groups/all non-white ethnic groups (Oxford English Dictionary, 2020). The respondents were grouped and analysed as white (39%; n = 423) and non-white (61%; n = 655). Over the past 10 years, the number of BME students in HE is increasing and it is well reported there is a differential outcome in curriculum progression and employment between BME and white students. The causes and factors were explored in HEFCE report in 2015 (Mountford-Zimdars et al., 2015). Moreover, previous literature states that non-traditional students find the transition to HE more difficult and they are more hesitant to approach their PT, thus leading to higher withdrawal rates (Small, 2013). However, this is not evident in the current study as no significant difference was found between BME and white students in terms of engagement and in overall satisfaction with the PTS.

The effect of declared disability on the engagement in the PTS was also explored. One eighth of students (12.5%; n = 135) considered themselves to have a disability. The two most common disabilities reported were mental health concerns (including depression and anxiety) and dyslexia. No significant difference in engagement with the PTS was found, instead a significant difference (p = 0.046) in satisfaction with the PTS was found. Disabled students scored a lower number on the Likert scale regarding overall satisfaction leading to the conclusion that disabled students are generally less satisfied with the PTS. Considering that the most commonly reported disability was a mental health problem such as depression or anxiety, these results could suggest that the PTs did not have a good understanding of such issues, hence raising questions on how the institution has prepared and trained members of staff in dealing with mental health issues.

Student experience is influenced by their expectations (Yale, 2019); however, there is a gap between what students expect from a PTS and what they experience (Yale, 2017). Looking at Figure 4, there was a significant difference between students’ perception and expectations of supportiveness (20.5% difference), approachability (19.4% difference), and availability (15.6% difference) of their PTs. There are several factors contributing to this drop from expectations to experiences. Most students would have started HE directly after some form of secondary school, which is characterized by a supportive learning environment with approachable teachers whose main function is to guide and support their students (Noddings, 2003). Unlike lecturers who have several roles and functions at a university, school teachers’ main focus is the well-being of their students (Stewart, 2016), which is facilitated by smaller classes size. Students entering HE may expect a similar culture. Another important factor associated with higher expectations is the high tuition fees paid by students (Bates and Kaye, 2014). By paying such high fees students become customers who expect value for money (Marcus and Fearn, 2008) and value, from a student’s perspective, is a high level of support (Bates and Kaye, 2014). In addition, HE has become an incredibly competitive marketplace in recent years resulting in aggressive marketing with over-promising prospectuses and other promotional information resulting in high student expectations (Marcus and Fearn, 2008).

Qualitative analysis of comments identified a common theme: students expected their PTs to make the initial contact. The following comments by two students show examples of this trend:

“My personal tutor never made any contact with me. I’m extremely disappointed”

“Personal tutor has never contacted me; I didn’t feel comfortable approaching him as we had never met.”

This same mindset of students was also reported by Malik (2000). The second student comment above describes a potential reason for this attitude–some students may feel uncomfortable approaching their PT or making initial contact, especially if they do not know who the person is (for example if they do not have their PT as a lecturer).

Conclusions and Limitations

The data reported by the current study indicate that there is a gap between students’ expectations and their experiences of the PTS; however, this gap appears to be reducing, based on comparison with previous literature. Most of the students at the post-1992 university engaged with the PTS and were generally satisfied with the PTS. The majority of the students who did not engage with the PTS remarked they either were unaware of such a scheme, or they expected their PT to contact them. The latter comment shades an interesting light of students’ views about the expected availability and pro-activity of PTs.

The key to success of a PTS is the development of a strong PT-student relationship (Malik, 2000; Hughes, 2004; Braine and Parnell, 2011; Small, 2013; Ross et al., 2014). This is confirmed by this study: frequent and regular meetings are linked to the development of a robust relationship, in turn boosting overall satisfaction with the PTS. These results also strongly indicate that making the PTS compulsory (especially in Foundation and Year 1) would lead to improvement in satisfaction, which could ultimately lead to a lower rate of withdrawals.

According to this study, group tutorials do not appear to be popular. However, students should be advised on the advantages of group tutorials and encouraged to participate in them. Group tutorials can help foster a sense of belonging and help students form a network (Braine and Parnell, 2011; Small, 2013); it would therefore be useful to integrate group tutorials into the PTS, especially in the first year of study to aid the transition into HE.

The data showed that there was no BME gap in terms of engagement and satisfaction with the PTS as suggested by previous literature. However, there was evidence indicating a difference in satisfaction rates between students with disabilities to those without disabilities. Considering that most students who consider themselves to have a disability stated that they had a mental health problem, this gap in satisfaction might be addressed by training the PTs on mental health issues.

There are a number of limitations to this study. Majority of the collated data were quantitative data and only one open-ended question was used and this limited the ability of the participants to express themselves and also limited the ability of the authors to explore new and unexpected insights that might affect the students’ engagement in the PTS. For instance, it would have been interesting to explore the reasons behind preferring compulsory PT sessions by some students and the reasons students provided for not meeting with their tutor. The paper was conducted by insider researchers who are familiar with the institution and settings; this helped the research group to achieve high response rate by tailoring the results collection strategy. To avoid such limitations, the research group recruited participants across the whole university and did not limit it to the school where the researchers work to minimize any bias.

Recommendations

The results of this study denote students have expectations of a PTS in HE higher than what they currently experience. The HE landscape is a fast paced, evolving environment and institutions ought to provide students with clearer policies and guidance on the functions of the PTS (Braine and Parnell, 2011), making it clearer as to how they can benefit from it. HE institutions ought to invest time and resources into managing students’ expectations of the PTS, especially in Foundation and Year 1 (Bates and Kaye, 2014) where drop-outs are the highest. This could be achieved by embedding a PTS into first year modules.

Institutions also have the responsibility to provide training for new members of staff as well as continuous support for established lecturers (Ross, et al., 2014). Training should not only focus on the core values of PTs, but should also provide PTs with modern tools in mental health and well-being awareness so that PTs are better equipped to support the modern students. Concomitantly, it would wise for institutions to foster a culture of reward and shape the way to future practice by rewarding members of staff who excel in student support. Ross, et al. (2014) recommends that any achievements or successes of both the student and PT should be shared and celebrated.

As unveiled by this study as well as previously reported by Malik (2000), many students do not feel comfortable making that initial contact with their PT. This issue should be addressed early: students should be advised to feel comfortable in reaching out and, equally, staff shall be trained to be more proactive in creating that link that is vital to students’ engagement and progression.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Kingston University Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

GC, DL, NT, AJ, DD, and AE designed and conducted the study. GC and AE contributed to the study conceptualisation and design. NT, AJ, DD designed data collection tool and collected data. DL analysed the data and synthesised the findings. GC and AE prepared the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding

The authors would like to thank Student Academic Development Research Associate Scheme (SADRAS) at Kingston University for funding this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.727410/full#supplementary-material

References

Bates, E. A., and Kaye, L. K. (2014). "I'd Be Expecting Caviar in Lectures": the Impact of the New Fee Regime on Undergraduate Students' Expectations of Higher Education. High Educ. 67 (5), 655–673. doi:10.1007/s10734-013-9671-3

Braine, M. E., and Parnell, J. (2011). Exploring Student's Perceptions and Experience of Personal Tutors. Nurse Educ. Today 31 (8), 904–910. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2011.01.005

Browne, B. A., Kaldenberg, D. O., Browne, W. G., and Brown, D. J. (1998). Student as Customer: Factors Affecting Satisfaction and Assessments of Institutional Quality. J. Marketing Higher Educ. 8 (3), 1–14. doi:10.1300/j050v08n03_01

Chanock, K., Horton, C., Reedman, M., and Stephenson, B. (2012). Collaborating to Embed Academic Literacies and Personal Support in First Year Discipline Subjects. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 9 (3), 1–13. doi:10.53761/1.9.3.3

Defeyter, M. A., Stretesky, P. B., Long, M. A., Furey, S. A., Reynolds, C., Porteous, D., et al. (2021). Mental Well-Being in UK Higher Education during Covid-19: Do Students Trust Universities and the Government? Front. Public Health 9, 1–13. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.646916

Douglas, J., Douglas, A., and Barnes, B. (2006). Measuring Student Satisfaction at a UK university. Qual. Assur. Educ. 14 (3), 251–267. doi:10.1108/09684880610678568

Gorczynski, P., Sims-schouten, W., Hill, D., and Wilson, J. C. (2017). Examining Mental Health Literacy, Help Seeking Behaviours, and Mental Health Outcomes in UK university Students. Jmhtep 12 (2), 111–120. doi:10.1108/jmhtep-05-2016-0027

Grey, D., and Osborne, C. (2018). Perceptions and Principles of Personal Tutoring. J. further Higher Educ. 44 (3), 285–299. doi:10.1080/0309877x.2018.1536258

Guolla, M. (1999). Assessing the Teaching Quality to Student Satisfaction Relationship: Applied Customer Satisfaction Research in the Classroom. J. Marketing Theor. Pract. 7, 87–97. doi:10.1080/10696679.1999.11501843

Hill, F. M. (1995). Managing Service Quality in Higher Education: The Role of the Student as Primary Consumer. Qual. Assur. Educ. 3, 10–21. doi:10.1108/09684889510093497

J Hughes, S. (2004). The Mentoring Role of the Personal Tutor in the ;Fitness for Practice' Curriculum: an All Wales Approach. Nurse Educ. Pract. 4 (4), 271–278. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2004.01.006

Kivunja, C. (2015). ‘Why Students Don’t like Assessment and How to Change Their Perceptions in 21st Century Pedagogies’. Ce 06, 2117–2126. doi:10.4236/ce.2015.620215

Lochtie, D., McIntosh, E., Stork, A., and Walker, B. W. (2018). Effective Personal Tutoring in Higher Education. ST ALBANS: Critical Publishing.

Malik, S. (2000). Students, Tutors and Relationships: The Ingredients of a Successful Student Support Scheme. Med. Educ. 34, 635–641.

McFarlane, K. J. (2016). Tutoring the Tutors: Supporting Effective Personal Tutoring. Active Learn. Higher Educ. 17 (1), 77–88. doi:10.1177/1469787415616720

Mountford-Zimdars, A. K., Sanders, J., Jones, S., Sabri, D., Moore, J., and Higham, L. (2015). Causes of Differences in Student Outcomes (Report). Higher Education Funding Council for England. Available at: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/23653/1/HEFCE2015_diffout.pdf (Accessed 0311, 2021).

Noddings, N. (2003). Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics & Moral Education. 2nd Edition. Berkley, Calif.; London: University of California Press.

Owen, M. (2002). 'Sometimes You Feel You're in Niche Time'. Active Learn. Higher Educ. 3 (1), 7–23. doi:10.1177/1469787402003001002

Oxford English Dictionary (2020). Available at: https://www.lexico.com/definition/bme (Accessed August 22, 2020).

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V., and Berry, L. (1988). SERVQUAL: a Multiple-Item Scale Formeasuring Consumer Perceptions of Service Quality. J. Retailing 64 (1), 12–40.

Pereira, S., Reay, K., Bottell, J., Walker, L., Dzikiti, C., Platt, C., et al. (2019). University Student Mental Health Survey 2018. London: The Insight Network & Dig-In

Ross, J., Head, K., King, L., Perry, P. M., and Smith, S. (2014). The Personal Development Tutor Role: An Exploration of Student and Lecturer Experiences and Perceptions of that Relationship. Nurse Educ. Today 34 (9), 1207–1213. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2014.01.001

Sherry, C., Bhat, R., Beaver, B., and Ling, A. (2004). “Students as Customers: The Expectations and Perceptions of Local and International Students,” in Research and Development in Higher Education: Transforming Knowledge into Wisdom Holistic Approaches to Teaching and Learning Vol. 27, Miri, Sarawak, 4–7 July 2004, 309.

Simpson, O., Thomas, L., and Hixenbaugh, P. (2006). “Rescuing the Personal Tutor: Lessons in Costs and Benefits,” in Perspectives on Personal Tutoring in Mass Higher Education. Editors Thomas, and Hixenbaugh (Stoke-on-Trent: Pub Trentham Books).

Small, F. (2013). Enhancing the Role of Personal Tutor in Professional Undergraduate Education. Inspiring Academic Practice. Available at: https://education.exeter.ac.uk/ojs/index.php/inspire/article/view/12 (Accessed August 9, 2020).

Stewart, M. A. (2016). Nurturing Caring Relationships through Five Simple Rules. English J. 105 (3), 22–28.

Tight, M. (2019). Student Retention and Engagement in Higher Education. J. Further Higher Educ. 44 (5), 689–704. doi:10.1080/0309877x.2019.1576860

Wilcox, P., Winn, S., and Fyvie‐Gauld, M. (2005). 'It Was Nothing to Do with the university, it Was Just the People': the Role of Social Support in the First‐year Experience of Higher Education. Stud. Higher Educ. 30 (6), 707–722. doi:10.1080/03075070500340036

Yale, A. T. (2019). Quality Matters: an In-Depth Exploration of the Student-Personal Tutor Relationship in Higher Education from the Student Perspective. J. further Higher Educ. 44 (6), 739–752. doi:10.1080/0309877x.2019.1596235

Keywords: personal tutoring, higher education, perceptions, expectations, students demographics

Citation: Calabrese G, Leadbitter D-LM, Trindade NDSMD, Jeyabalan A, Dolton D and ElShaer A (2022) Personal Tutoring Scheme: Expectations, Perceptions and Factors Affecting Students’ Engagement. Front. Educ. 6:727410. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.727410

Received: 18 June 2021; Accepted: 06 December 2021;

Published: 03 February 2022.

Edited by:

Annabel Theresa Yale, Edge Hill University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Ben W. Walker, Oxford Brookes University, United KingdomLidon Moliner, University of Jaume I, Spain

Copyright © 2022 Calabrese, Leadbitter, Trindade, Jeyabalan, Dolton and ElShaer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Amr ElShaer, YS5lbHNoYWVyQGtpbmdzdG9uLmFjLnVr

Gianpiero Calabrese

Gianpiero Calabrese Debbie-Leigh M Leadbitter

Debbie-Leigh M Leadbitter Ashveini Jeyabalan

Ashveini Jeyabalan Amr ElShaer

Amr ElShaer