- 1Department of Neurology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, United States

- 2Department of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, United States

Introduction

Away rotations are common among senior medical students who want to pursue residency training in the American healthcare system—a recent study quoted 56% of students complete at least one away rotation (Aagaard and Abaza, 2016). Surveys from program directors indicate performance on these away electives is an important factor in selecting candidates to interview (Bernstein et al., 2002a; Bernstein et al., 2002b; Janis and Hatef, 2008; Makdisi et al., 2011; Gorouhi et al., 2014; Weissbart et al., 2015). To guide prospective students on maximizing these valuable experiences, a team of neurology clerkship directors and U.S. and international trainees collaborated to formulate a neurologist’s guide for excelling during away rotations based on a review of available literature and direct experience. Given the limited published data on this subject, we compiled recommendations based on anecdotal experience from successful applicants as well as perspectives from program faculty to provide practical guidance for senior medical students seeking to enhance their application through away rotations. Recommendations unique to international students are also highlighted. Although the content in this commentary is derived from experiences in the field of neurology, the overall guidance is generalizable to away rotations in other medical specialties.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Away Electives

Away electives are beneficial to students as they provide an inherent educational value, allow students to obtain letters of recommendation, and create networking connections for future employment (Ances, 2006; Griffith et al., 2019). Students are exposed to new clinical practices, teaching styles, and research opportunities. International students gain valuable experience with the U.S. medical system. Additionally, away rotations provide an opportunity for students to gain insight into a program that would otherwise be unattainable before matching into residency. Higgins et al. note, in a survey of 756 fourth-year medical students, 53% of those who had completed an away rotation ranked a program lower on their list or not at all due to information they learned while on their rotation (Higgins et al., 2016).

However, participating in these electives comes with high costs. Students have minimal time to make a good first impression on the host institution, and attending multiple institutions requires a considerable amount of time and money (Griffith et al., 2019). A recent study reported that the mean cost of completing a single away rotation was $958, and the mean number of visiting rotations for neurology applicants was 2.2. However, some applicants reported spending over $10,000 (Winterton et al., 2016).

Students can look for scholarship opportunities to help with rotation expenses. One such example is the visiting medical student scholar program through the American Academy of Neurology (American Academy of Neurology, 2021). Huggett et al. note, while away rotations are widely used, they are poorly understood and can vary significantly by institutions, so research into host institutions is instrumental (Huggett et al., 2015).

Selecting an Appropriate Away Rotation

Ideally, carrying out away electives in July, August, or September is preferable since they are in the vicinity of the residency application, which now opens at the end of September. Although doing a rotation in October or November may also be considered valuable, it will be challenging to obtain a letter of recommendation (LOR) on time for residency application. Undoubtedly, for international medical students, given that their graduation timeline differs from US medical students, and depending on when they apply for the match, it might not be feasible to schedule an away rotation during these months. The actual process for selecting and applying to away rotations can be daunting, including a substantial amount of paperwork and training modules required before the start of away rotation. Careful and thoughtful planning may help mitigate these challenges and we recommend that applicants start early and ask former students for feedback on their selection process and elective experiences. When reaching out to the programs, the letter of interest (LOI) is critical as it is a way for clerkship directors to see who is genuinely interested. The LOI should be brief, demonstrate the student’s commitment to the specialty, and reflect what a student hopes to gain from the rotation experience. Occasionally, programs request other information like any potential connection to the rotation site or any interest in the sub-specialties that the program may offer, which should also be addressed in the LOI. The Association of American Medical College (AAMC) provides guidance for both national and international students and helps improve their chances of being accepted (AAMC, 2021). The AAMC Visiting Student Learning Opportunities (VSLO) is the platform used by most programs for the application processes, though some programs choose not to participate in VSLO.

Preparing for the Experience

To make an outstanding impression, students should hone their knowledge of the neurological exam, including maneuvers common in different subspecialties; they should have the essential tools needed for a detailed neurological examination: a reflex hammer, tuning fork, ophthalmoscope, and visual acuity card. Students should also review common neurological disease presentations and their anatomic localization and current treatments, which will allow them to generate a thorough differential diagnosis. We advise students to familiarize themselves with their attendings’ areas of interest, so they can engage in meaningful conversations while on the rotation. Making contact with the attending before the rotation is also encouraged as this provides an opportunity to make an early impression, define expectations, and solicit guidance for preparing for the rotation (E.g., appropriate texts/references, equipment). Finally, learning the hospital layout before beginning the rotation, if possible, can alleviate stress and allow students to focus on the clinical aspects of the experience.

Advice for the Rotation

The first few days may be the most overwhelming, as students get to know their new team and learn their role in the hospital. Foreign students might have a hard time “fitting in” at first (Bernstein et al., 2002b), due to cultural and language barriers. Introducing oneself as a visiting student applying into neurology can afford some leniency during the adjustment period, though it may also alert faculty to pay special attention. Asking the attending how they prefer patient presentations to be given on the first day will also help avoid confusion and allow students to prepare effective oral case presentations.

It is expected students know their patients’ histories, current and pending studies, and management plans. As students become more comfortable presenting cases, they should begin to take ownership of their patients’ care. Active listening and an empathetic attitude during patient encounters are critical skills for a prospective resident.

Neurology is an increasing evidence-based field, with new pivotal studies emerging every year. Bringing up-to-date knowledge and critically appraising primary sources of evidence can impress attendings. Asking questions, being proactive, and always showing up eager to learn can substantially impact how a student is perceived. We also recommend students give topic presentations to their team, in addition to their daily patient presentations, to showcase their communication ability and proactive learning.

Lastly, students can contribute to the education of the third-year medical students; this conveys they take a vested interest in every team member, which is a quality faculty hold in high regard. More effective teamwork translates into better clinical outcomes and a satisfying work environment (Manser, 2009). Although time spent on an elective is limited, students should see nearby attractions and sample the local cuisine—these can provide conversation topics to get to know the team personally.

Away Rotations During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Telemedicine

The COVID-19 pandemic had created a myriad of complications in medical education, including the year-long suspension of away rotations and subsequent “one rotation per learner per year” restriction for 2021-2022 (Association of American M). As the response to the pandemic continues to evolve, guidelines will continue to update. Schools utilize multiple learning modalities such as virtual didactics, online cases, and telehealth in following the AAMC’s guidelines for developing local substitutes for traditional away rotations. However, limited opportunities for exposure to host institutions can hinder students’ applications, especially for international students. To that end, many institutions have implemented virtual rotations for visiting students, which may allow students greater exposure to faculty.

The greater implementation of telemedicine will likely become a permanent addition to how physicians deliver care. When utilized correctly, telemedicine visits can increase effectiveness and provide homebound patients a convenient way to attend visits. However, they provide challenges to the health team, especially in obtaining a thorough physical exam. Al Hussona et al. provide up-to-date guidance on effectively completing a virtual neurologic exam (Al Hussona et al., 2020). Briefly, they provide straightforward suggestions on evaluation of cranial nerves as adapted for a video call and suggestions for thorough motor, sensory, and gait evaluations with accompanying demonstration videos. The visiting student should determine to what extent, if any, the institution is using telemedicine. Students should be familiar with institutional guidelines for telemedicine and understand what roles they may take on within this model. For many institutions, additional training or credentialing may be required to participate in health care delivered via telemedicine. As telemedicine is still a relatively new experience for some attendings and providers, a student who is facile and knowledgeable with technology will likely contribute positively to the overall clinic work flow rather than being viewed to be an additional burden on the faculty member.

How to Request a Letter of Recommendation

One of the most important objectives in completing an away rotation is to obtain a strong LOR. Before requesting a letter, students should meet with the faculty member (in-person or online) and provide them with a complete curriculum vitae (CV) and a personal statement, including their career aspirations within the field. Once the attending has agreed, students should give them at least 1 month to write the letter and ensure they know the submission deadline. It is also recommended that students waive their right to view the letter so the letter writer can give a candid evaluation.

Students should also remember to thank their letter writers formally. While an email expressing gratitude is a valuable display of professionalism and courtesy, a hand-written letter will go even further in displaying your appreciation. It is important to keep one’s letter writer updated throughout the application process. If they have agreed to write a letter, they have taken an interest in the applicant and likely want to continue offering support and share in future successes.

Discussion

Away electives not only benefit students by widening their educational experience and boosting their application, but also provide program administration a valuable opportunity to get to know their prospective applicants. Although the COVID-19 pandemic has led to significant changes in medical education, we predict that away rotations will continue to be an essential aspect of future residency application cycles. In addition to providing insight into a specialty at a different institution, they also provide students with further opportunities to create networking connections. It should be noted that a student can expect to be “on interview” for the entirety of their rotation, and therefore may worsen their chances if they do not make a good impression. Conversely, students may discover that a previously-adored program may not be a suitable fit for them throughout their rotation, saving them from discovering that after matching. Away rotations also come with a significant financial burden for applicants, and rotation experience may vary widely from place to place.

When selecting an away rotation, early research into the opportunities available is invaluable. Students may gain information through the VSLO platform if the host institution participates and may also connect with classmates at their home institution who have previously completed away rotations at locations they are considering. Some programs also allow applicants to email the program or faculty members directly. Students, internationals in particular, should avoid carelessness and have their email carefully checked by several colleagues, as verbal and written abilities are often associated with other forms of competence.

Students can mitigate feeling overwhelmed during the rotation with careful preparation, including reviewing all aspects of the neurologic physical examination and common presentations of neurologic disease and associated treatments. Early discussion with attendings on preferences for presentations can help to streamline rounds and avoid wasted time. Students are expected to know their patients’ histories, current/pending studies, and upcoming changes to their care. The goal should be gaining their attendings and residents’ confidence in the clinical care of their patients. Students can stand out by reading up on the other patients on the team and presenting evidence-based medicine. Additionally, completing progress notes, calling consults, and communicating with family are not likely to go unnoticed.

Students can excel in both virtual and in-person away rotations by becoming adept at telemedicine visits, which became a fast-growing subset of clinic appointments. We advise students to become proficient at navigating the technological challenges associated, taking a thorough history, and completing a virtual neurologic physical examination. As physicians are still determining their preferred styles for telemedicine visits, students should be prepared to be flexible in their presentations.

For many students, obtaining a LOR is one of the primary goals of an away rotation. Letters from full professors are often considered to carry more weight; however, an assistant or associate professor may be able to invest more time in getting to know the students and write a more personalized letter. Mostly, US seniors perform electives close to ERAS application. However, international students often cannot apply for residency the same year; thus, we suggest asking the letter writer to submit a copy to the Clerkship Director to ensure the LOR reflects the student’s actual performance rotation than if written many months later.

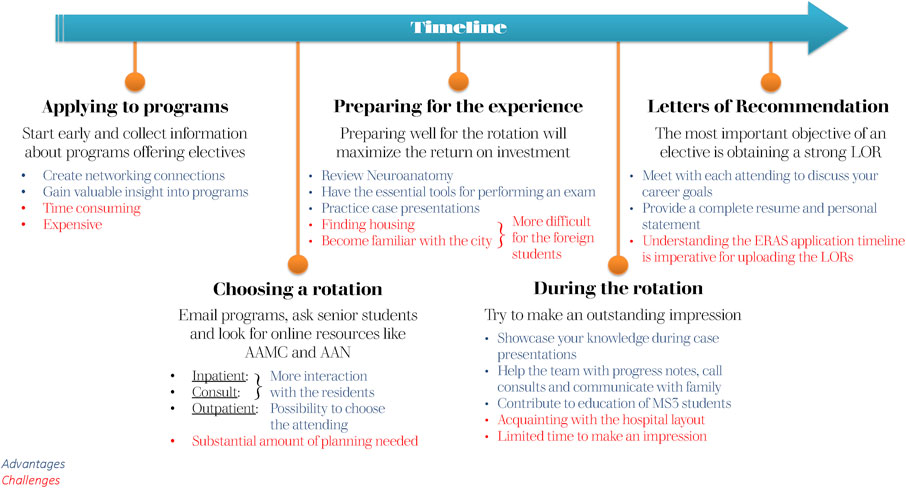

We have summarized the key points of this article in the form of a timeline (Figure 1) and hope that by following the above advice, visiting students will be better equipped to excel during their away rotations in neurology or other medical specialties. While this guidance is based on anecdotal experience from a panel from diverse backgrounds, our recommendations are intended to provide a general framework and are not based on validated evidence which is unfortunately lacking in this area. Ultimately, we hope that these recommendations will allow the applicant to get the most out of their away rotation and leave a favorable impression on future colleagues and collaborators during their rotation.

Author Contributions

AAM design and conceptualized the study, wrote the majority of the first draft of the manuscript. CC made the figure, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. LS added Telemedicine and discussion sections reviewed and edited the manuscript. JG, JR, and ML conceptualized the study, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the submitted version.

Funding

NIH/NINDS R25 NS079188 training award to AAM.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aagaard, E. M., and Abaza, M. (2016). The Residency Application Process - Burden and Consequences. N. Engl. J. Med. 374 (4), 303–305. doi:10.1056/nejmp1510394

American Academy of Neurology (2021). AAN Awards & Fellowships. Available from: https://www.aan.com/education-and-research/research/awards-fellowships/.

Al Hussona, M., Maher, M., Chan, D., Micieli, J. A., Jain, J. D., Khosravani, H., et al. (2020). The Virtual Neurologic Exam: Instructional Videos and Guidance for the COVID-19 Era. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 47 (5), 598–603. doi:10.1017/cjn.2020.96

Ances, B. M. (2006). The Away Neurology Rotation: Is the Grass Greener on the Other Side? Neurology 66 (9), E35–E36. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000216845.66742.9b

AAMC (2021). Association of American Medical College. Available from: https://aamc.org.

Bernstein, A. D., Jazrawi, L. M., Elbeshbeshy, B., Della Valle, C. J., and Zuckerman, J. D. (2002a). An Analysis of Orthopaedic Residency Selection Criteria. Bull. Hosp. Jt. Dis. 61 (1-2), 49–57.

Bernstein, A. D., Jazrawi, L. M., Elbeshbeshy, B., Valle, C. J. D., and Zuckerman, J. D. (2002b). Orthopaedic Resident-Selection Criteria. The J. Bone Jt. Surgery-American Volume 84 (11), 2090–2096. doi:10.2106/00004623-200211000-00026

Gorouhi, F., Alikhan, A., Rezaei, A., and Fazel, N. (2014). Dermatology Residency Selection Criteria with an Emphasis on Program Characteristics: a National Program Director Survey. Dermatol. Res. Pract. 2014, 692760. doi:10.1155/2014/692760

Griffith, M., DeMasi, S. C., McGrath, A. J., Love, J. N., Moll, J., and Santen, S. A. (2019). Time to Reevaluate the Away Rotation. Acad. Med. 94 (4), 496–500. doi:10.1097/acm.0000000000002505

Higgins, E., Newman, L., Halligan, K., Miller, M., Schwab, S., and Kosowicz, L. (2016). Do audition Electives Impact Match success? Med. Educ. Online 21, 31325. doi:10.3402/meo.v21.31325

Huggett, K. N., Borges, N. J., Jeffries, W. B., and Lofgreen, A. S. (2015). Audition Electives: Do Audition Electives Improve Competitiveness in the National Residency Matching Program? Springer.

Janis, J. E., and Hatef, D. A. (2008). Resident Selection Protocols in Plastic Surgery: a National Survey of Plastic Surgery Program Directors. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 122 (6), 1929–1939. doi:10.1097/prs.0b013e31818d20ae

Makdisi, G., Takeuchi, T., Rodriguez, J., Rucinski, J., and Wise, L. (2011). How We Select Our Residents-A Survey of Selection Criteria in General Surgery Residents. J. Surg. Education 68 (1), 67–72. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2010.10.003

Manser, T. (2009). Teamwork and Patient Safety in Dynamic Domains of Healthcare: a Review of the Literature. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 53 (2), 143–151. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01717.x

Weissbart, S. J., Stock, J. A., and Wein, A. J. (2015). Program Directors' Criteria for Selection into Urology Residency. Urology 85 (4), 731–736. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2014.12.041

Keywords: neurology, education, away rotation, medical students, international medical graduates, American medical graduates

Citation: Memon AA, Catiul C, Stoyka LE, Granade J, Rinker J and Lyerly M (2021) Neurology Electives: A Neurologist’s Guide for Excelling During Medical Student Away Rotations. Front. Educ. 6:713126. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.713126

Received: 21 May 2021; Accepted: 19 July 2021;

Published: 29 July 2021.

Edited by:

Joseph Safdieh, Cornell University, United StatesReviewed by:

Anna Hohler, Boston University, United StatesCopyright © 2021 Memon, Catiul, Stoyka, Granade, Rinker and Lyerly. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Adeel A. Memon, YW1lbW9uQHVhYm1jLmVkdQ==

Adeel A. Memon

Adeel A. Memon Corina Catiul

Corina Catiul Lindsay E. Stoyka

Lindsay E. Stoyka Joseph Granade2

Joseph Granade2 Michael Lyerly

Michael Lyerly