- 1School of Foreign Language, Shanghai Jian Qiao University, Shanghai, China

- 2School of Education, The University of Queensland, QLD, Australia

Teacher questions have long been considered important in mediating students’ learning in language classrooms. This paper examined the mediated-learning behaviors involved in teacher questions during whole-class instruction in high schools of China. Five lessons of different topics were observed. Conversation analytic approach was applied to analyze teachers’ verbal interactions with students during whole-class teaching. Teachers’ questions and students’ responses were transcribed and categorized as display questions or referential questions. The mediated-learning behaviors involved in the two types of questions were discussed by presenting six sessions of interaction. The study investigated which question type initiated the interaction involving more variety of mediated-learning behaviors and what pedagogical implications this may have for teacher questioning techniques that enhance student learning. The study found the interactions initiated by referential questions contain more varieties of mediated-learning behaviors. This study suggests that teachers need to be encouraged to use referential questions more frequently whether in display interactions or in referential interactions.

Introduction

Interaction determines and affects the conditions of language acquisition by providing students with opportunities to input and output language comprehensively, especially in contexts where exposure to the target language is limited (Philp and Tognini, 2009). Interaction which falls within the scope of the Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) approach is highly advocated in EFL contexts, which usually includes whole-class teaching and small-group learning. Teachers’ verbal behaviors during whole-class instruction involve the behaviors addressing the general audience such as lecturing, giving instructions, asking questions, maintaining general discipline, and acknowledging students’ efforts. During group learning, teachers’ verbal behaviors are more supportive and personal with concrete encouragers and facilitating words, pertinent and targeted feedback, and praise (Hertz-Lazarowitz and Shachar, 1990). Therefore, teachers frequently implement group work or pair work to maximize opportunities for interaction (Edstrom, 2015).

However, in the context of teaching and learning being fundamentally guided by traditional instruction, such as in China (Hu, 2002; Huang, 2004; Liu, 2016; Liu and Wang, 2020), group work and pair work are not so commonplace as in countries like the United Kingdom, United States, Australia and others that use a more communicative pedagogical approach to language instruction. Pair work and group work in the classrooms of China are usually randomly organized based on students’ seat arrangements in order to complete a task assigned by the teacher. Usually, the students are allowed only several minutes to discuss a topic, and in the meantime, the teacher walks around to offer help. When the teacher declares the time is up, the group or pair stand up to report the results of their discussion with the teacher making comments afterward. Usually only one or two of the groups have the opportunity to report because of limited class time. The work from other groups usually goes without being discussed. In this context, class discussions look more like a session of interaction between the teacher and the students as occurs during whole-class instruction than cooperative learning or small group learning. The teacher-centered interaction in whole-class instruction is still dominant in EFL classrooms in China (Jin and Cortazzi, 1998; Halstead and Zhu, 2009; Peng, 2011; Liu and Wang, 2020). Whole-class teaching is normally inquiry-based so teachers influence how students learn by varying the types of questions they ask (Rutten et al., 2015). Based on a social-constructivist learning perspective, inquiry-based teaching and learning in the whole-class setting promotes more socially mediated classroom interactions (Smetana and Bell, 2013). Therefore, teacher-centered interaction in whole-class instruction warrants an investigation. A couple of studies found that mediated-learning behaviors occur between teachers and students and between students and students during cooperative learning or small-group learning (e.g., Gillies, 2004, 2006; Gillies and Haynes, 2011), but there is little research that focuses on the mediated-learning behaviors between teacher and students when the teacher engages in whole-class instruction. Questioning is one of the common forms of interaction utilized by the teacher in the classroom. Teacher questions provide an opportunity for the students to use English, compelling students to think and learn, which helps them to comprehend the materials and communicate using the language they are learning (Erlinda and Dewi, 2016). There are studies about teacher questions and most of them investigate teacher question types and their influence on students (e.g., Affandi, 2016; Al-Zahrani and AL-Bargi, 2017; David, 2007; Erlinda and Dewi, 2016; Halim and Mazlina, 2018; Hamel, et al., 2020; Lillydahl, 2015; Qashoa, 2013; Ruddick, 2011; Shen, 2012; Shu, 2014; Tan, 2007; Wright, 2016; Yang, 2010). Little research has been found regarding the mediated-learning behaviors involved in different types of questions.

The current study documents two types of teacher questions and the mediated-learning behaviors contained in teacher-student interactions that are initiated by the questions when the teacher implements whole-class instruction. By analyzing the mediated-learning behaviors, this study aims to identify the relationship between mediated-learning behavior and question types.

Literature Review

According to Vygotsky, the element that explains the higher psychological process is semiotic mediation, that is to say, the creation and use of symbol systems, such as language, that are used as mechanisms for extending and regulating human behavior (Vygotsky and Luria, 1993; Moll et al., 2014). Semiotic mediation of language is understood as the inculcation of mental disposition (Hasan, 2002). Practically, language mediates human thoughts and action through interaction (Kohler, 2015). Gillies (2006) and Gillies and Boyle (2008) coded six categories of teachers’ verbal interactions, among which are questions and mediations. The understanding of the significance of language as a powerful tool of mediation makes mediation a core of the teaching and learning process. In terms of language teaching and learning, mediation is an embodied process of teachers’ orientation and understandings of language and culture and overall conception of language teaching and learning. It is concerned with teachers’ talk, in particular, questions as the main stimulus and scaffold for learning (Kohler, 2015). Mediated-learning behaviors in the interactions started with teachers’ questions include probing basic information, challenging cognitive thinking and reasoning, promoting elaboration, focusing on specific issues, tentatively questioning, scaffolding information, paraphrasing to assist understanding, and validating and acknowledging students’ efforts (Gillies and Boyle, 2006, 2008). These mediated-learning behaviors in teachers’ discourses function to promote a sequence of reciprocal interactions between the teacher and the student(s) that are capable of encouraging students to focus on specific problem-solving strategies and continue with the dialogue (Gillies, 2004). Some earlier research also found mediated-learning interactions scaffold student learning and prompt meaningful cognitive and metacognitive thinking through challenging student thinking (Palincsar, 1998; Smyth and Carless, 2020).

In an EFL context, where students share the first language (L1) like the situation in China, questioning is a way of eliciting comprehensible output (Wright, 2016). Questions and mediations are frequently employed in EFL classrooms, especially in CLT classrooms (Ekembe, 2014), although these facilitative verbal interactions happen more often in a cooperative learning environment than a whole-class instruction environment. For example, Gillies (2004, 2006, 2008) and Gillies and Boyle (2006) found that in cooperative learning or group learning, teachers pose more questions and use more mediated-learning interactions to scaffold student learning. In whole-class instruction, where the teacher plays a more prominent role in facilitating classroom interaction, teacher control is a predominant behavior with encouragement also happening throughout the lesson. Questioning is a common strategy to facilitate foreign language communication by creating more dialogues in the whole-class instruction, which forms an integral part of classroom interaction (Ho, 2005). It is through questions that teachers direct students’ attention to language form or learning content which, in turn, contribute to students’ language development (Tan, 2007; Arifin, 2012). Effective teachers not only cast many questions to involve the students in discussion; they also ask relatively many process questions to sustain the interaction (Creemers and Kyriakides, 2006). Students could be asked to expand their thinking and justify or clarify their opinions in the follow-up interactions (Yang, 2010). Therefore, it is enlightening not only to consider the frequency of certain types of questions the teacher poses, but also to look at how these questions are followed up and extended (Rutten et al., 2015).

In the context of the communicative language teaching approach, one aspect of questioning strategy influencing enhanced output and learning is question type (Hong, 2006; Zohrabi et al., 2014; Al-Zahrani and AL-Bargi, 2017), which means teachers influence students’ learning by varying their question types to achieve different purposes (King, 2002) Researchers have suggested several categories of teacher questions based on the type of response they ask for and the pedagogical purpose they serve, such as convergent/divergent questions, display/referential questions or low-cognitive/high-cognitive questions. This study considers the classification of questions as display questions and referential questions (Long and Sato, 1983; Brock, 1986). Under the heading of display, the questions are those to which the teacher has an answer or there is only one answer and those that require students to “display (report or recall)” their knowledge of comprehension, confirmation or clarification, for example, “What information have you got from the recording? or “What is the synonym of expectation?.” Under the heading of referential, the questions are those to which the teacher does not have an answer or there are several equally valid answers and those that demand an answer involving some form of reasoning, analysis, evaluation or the formulation of an opinion or judgment (Hargreaves, 1984; Tsui, 2001), for example, “What are your suggestions for maintaining a healthy lifestyle?.” In short, the purpose of a referential question is to seek further and deeper information, while a display question is to elicit learnt knowledge (Richards and Schmidt, 2010). Generally, inquiry-based whole-class teaching starts with asking questions to establish hypotheses, continue with processes of further investigation, and ends with a conclusion and evaluation (Bell et al., 2010). The review above on two types of questions seemingly indicate the referential questions promise further analysis and evaluation while display questions only recall information that was presented before. However, interestingly, many conflicting findings have been reported by the research regarding teacher usage of and student response to display and referential questions (Wright, 2016). Some claim that referential questions can yield extended interaction and enhanced student output and learning (e.g., Brock, 1986; Ho, 2005; Hong, 2006; McNeil, 2012; Shu, 2014; Wright, 2016; Zohrabi, et al., 2014). Some others find referential questions do not necessarily elicit significantly more student speech, but display questions that promote more interaction and are central resources for language pedagogy due to high frequency of usage by teachers (e.g., Long and Sato, 1984; Shomoosi, 2004; Tsui, 2001; Lee, 2006; David, 2007; Yang, 2010). However, some research argues that although referential questions may not guarantee student responses will be enhanced, student learning and acquisition may have been aided by answering referential questions (Long and Sato, 1984). McNeil (2012) also points to the importance of teacher talk as a scaffolding tool to assist students to make meaningful responses to referential questions.

This study looks at teacher-student interactions initiated by teacher display and referential questions in Chinese EFL classroom in order to investigate:

What mediated-learning behaviors are involved in the two types of questions and what are the pedagogical implications?

Human Mediation

“The teacher assumes a relevant role in that he or she is a promoter of activities that encourages participation and offers affective quality in interactions and social relationships within educational contexts.” (Varela et al., 2020, p. 18) This can be interpreted as that the fundamental responsibility of teachers is to promote the development of students through mediation, in which language is a privileged instrument. The present study investigates mediated-learning behavior contained in teacher questions, which is informed by the notion that the teacher is an important human mediator in student learning.

Mediation, as a core concept in sociocultural theory, refers to “the process through which humans deploy culturally constructed artifacts, concepts, and activities to regulate the material world or their own and each other’s social and mental activity” (Lantolf and Thorne, 2006, p. 79). Social relationships and culturally constructed media or tools mediate the form of human higher-level thinking (Johnson, 2009). Mediated learning means the process of knowledge acquisition is assisted by significant people by means of selecting and shaping the learning experiences presented to children (Williams and Burden, 1997). Human mediation usually refers to the situation where experienced, well-intentioned and active adults (usually parents or teachers) are involved in the enhancement of the child’s performance by selecting, changing, scheduling or interpreting the contents or the environment offered to the child (Schur and Kozulin, 2008). The significance of human mediation has also been highlighted in the learning process of the students in special education (Berry, 2006).

Through organized learning activities, effective human mediation takes place by involving symbolic tools to help learners master skills of reasoning and problem solving (Kozulin, 2003). In the school environment, the human mediator is the teacher and symbolic tools are various educational materials and approaches, such as teacher questioning. Teacher mediation helps enhance students’ performance by organizing effective learning activities involving teaching materials and establishing positive relationships with students. The role of teacher mediation is to help students transit from the level of social interaction with the teacher to the individual level of internalized function (Kozulin, 2002).

Method

Study Design

The study aims to investigate the behaviors of teachers as human mediators in classrooms to identify the mediated-learning behaviors involved in the teacher questioning process. It draws on a multimodal conversation analytic (CA) approach (Stivers and Sidnell, 2005; Deppermann, 2013) to investigate interaction between the teacher and the students in situations of whole-class teaching. CA is a dominant qualitative approach to the systematic study of social interaction. This qualitative method identifies and describes the behaviors of teacher questioning and uses these results to understand and describe the underlying structural organization of social interaction (Stivers, 2015)—in this case, teachers’ mediated-learning behavior and student responses. Audio and video recordings are essential with CA for a detailed analysis of their actual situated activities (Mondada, 2013). This study used videos of five public lessons to capture all the necessary data. In China, public lessons conducted in one school are usually open to teachers and researchers from other schools. The lessons are also video-recorded by the school for future self-reference or for communication between schools. Normally, English public lessons are more communication-based, which provides a better opportunity for research on classroom interaction (Wright, 2016). Five lessons were acquired from the website of Teacher College of Xu Hui District, which were posted by the Teaching Researcher for training purpose. The lessons were selected deliberately to cover different learning topics, so as to contribute to the diversification of teachers’ questions. The authors also took teacher profile and the composition of their classes into consideration. All the teachers are Chinese and have 5–10 years of working experience as English teachers in high schools of Shanghai, China. Their classes are usually composed of 35–45 students. All the students have been learning English as a school subject for nearly 10 years. The teachers conducted the lessons in English and students gave their responses in English.

Every session of interaction starting with a teacher question during whole-class instruction was transcribed and coded to assist the first author to clearly identify the structure of the two types of questions. The interaction during whole-class instruction usually occurred between the teacher and a nominated student or the whole class. Both teacher discourse and student responses were discussed. Through the analysis of the mediated-learning behaviors involved in the interactions (stretches of lesson that only contain one type of question), the authors attempted to highlight the differences of mediated-learning behavior usage in both types of questions. The ultimate purpose was to inform how teachers can enhance student learning during whole-class instruction by employing effective questions.

Procedure

The first author observed the lesson videos carefully and recorded all the questions expressed by the teacher and the responses from the students. In most cases, a 40-min lesson is composed of teacher lecture and instruction, student task completion (individually, in pair or in group), and interaction between teachers and students during whole-class instruction or during group work. For the purpose of this study, all the questions and answers between the teacher and the students during the whole-class instruction were transcribed. The first author studied every session of interaction and coded them into display category or referential category based on the characteristics of the two types of questions. Subsequently, all the sessions included in two categories were examined and six representative sessions were picked from three lessons, with one display interaction and one referential interaction from each lesson. Each selected session was disassembled and regrouped into a table to highlight the teacher’s discourse for the identification of mediating behaviors. The first author examined the discourse of the teachers and labeled the mediated-learning behavior contained in the teacher’s question and response (e.g., probe, acknowledge, prompt, tentative question, challenge, etc.). The value and implication of each use of mediating behavior was discussed following the table, with the purpose to make their function prominent.

Findings

In the whole-class instruction portion of the five investigated lessons, referential questions were asked to inquire about students’ opinions and reasons, while the display questions were asked to check whether students obtained the correct information from the learning materials or whether students remembered the knowledge previously learnt. When the teachers asked a question, they used mediating strategies such as probing, challenges, prompts, focusing statements, paraphrasing, further tentative questions or validating and acknowledging students’ efforts to extend, comment or enhance student responses. The first author presumed teachers’ use of the mediated-learning behaviors might differ when they asked display or referential questions. In the following sections, the first author discussed the mediated-learning behaviors involved in the sessions of interaction triggered by the two types of questions.

Lesson by Ling

Ling taught grammar—appositive clause—by employing a special situation she experienced. On national holidays, Ling had to cancel her trip to Fu Jian because of the typhoon Fitow. The text and audio materials were all about Typhoon Fitow and the reasons why Jolin had to give up her plan.

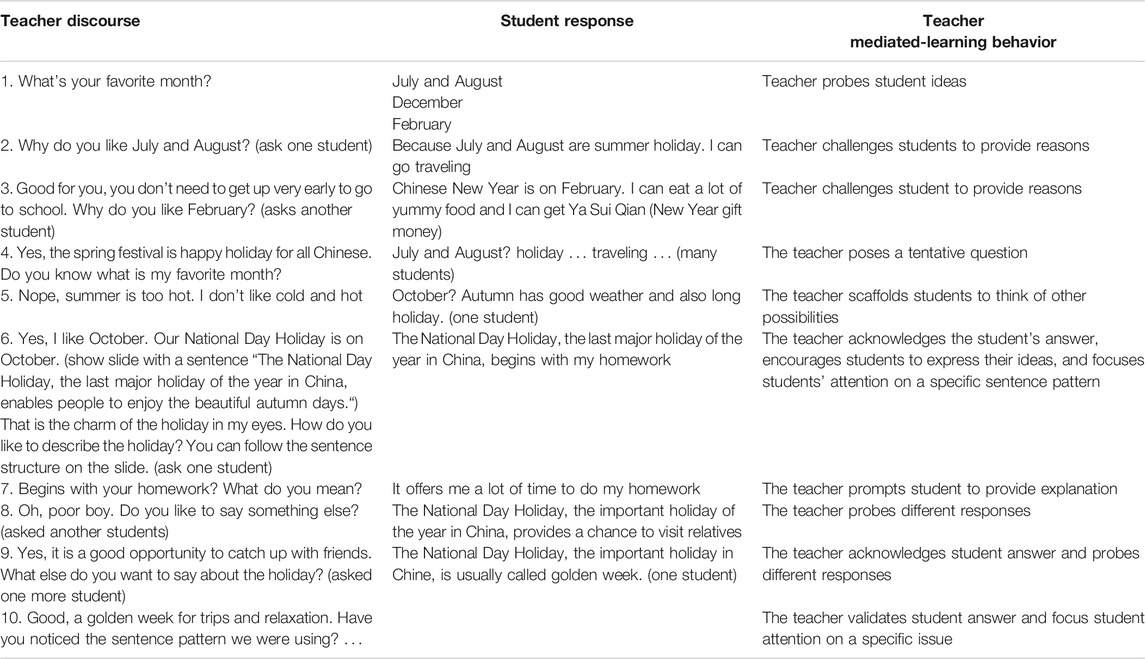

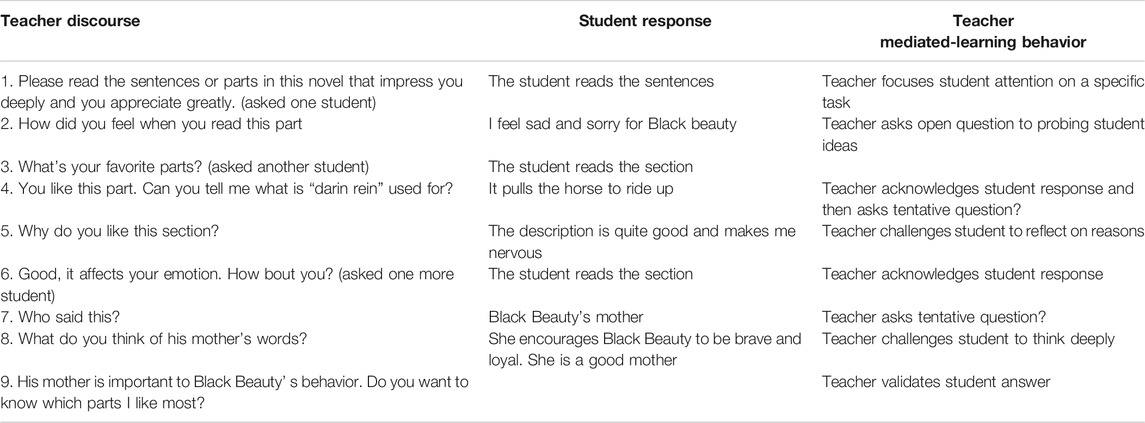

The first extract (Table 1) was the introduction of the lesson, which was a talk between Ling and her students. The students responded freely without being nominated by the teacher but occasionally the teacher prompted a few individual students. The session of interaction was categorized into referential question because the teacher did not have answers to the questions and student responses involve personal ideas and reasoning.

In the session of the interaction, the teacher started the dialogue with a referential question. In the following dialogue, she facilitated the interaction by probing (Turn 8 and 9), challenging (Trun 2,3 and 7), prompting ideas (Turn 6), asking tentative questions (Turn 4), focusing student attention on specific issues (Turn 6 and 10), scaffolding student thinking (Turn 5) and acknowledging and validating student answers (Turn 6, 9 and 10). With these mediating behaviors, the students expressed ideas, provided reasons, and made sensible guesses. Since the lesson focused on grammar, the students naturally employed the sentence structure with the teacher’s guidance.

In the second extract (Table 2), Ling checked students’ work after they listened to the WeChat recording about Ling’s explanation to her friend regarding canceling her trip to Fujian. The teacher did not nominate any specific student to respond, so the interaction took place between the teacher and the whole class. The session of interaction aimed to check students’ responses to see if they could be categorized as a display question.

During the above session of interaction, the teacher did not ask simple questions such as “What are the reasons?“, but instead, she prompted students to elaborate details they had obtained from the listening materials to make the activity a “real time” dialogue with diversified sentences. Aside acknowledging and validating, the teacher prompted the student to provide more information (Turn 1, 3, 4, 5, 6). The teacher also scaffolded the student to report the right answer by using the sentence pattern under discussion (Turn 7) and enforced the sentence pattern by repeating it (Turn 8). In this session of interaction, students responded with the information they obtained from the audio clip, but the teacher made it a smooth dialogue instead of reporting the right answer one by one. In the meantime, the teacher employed a few mediated-learning behaviors.

Lesson by Ming

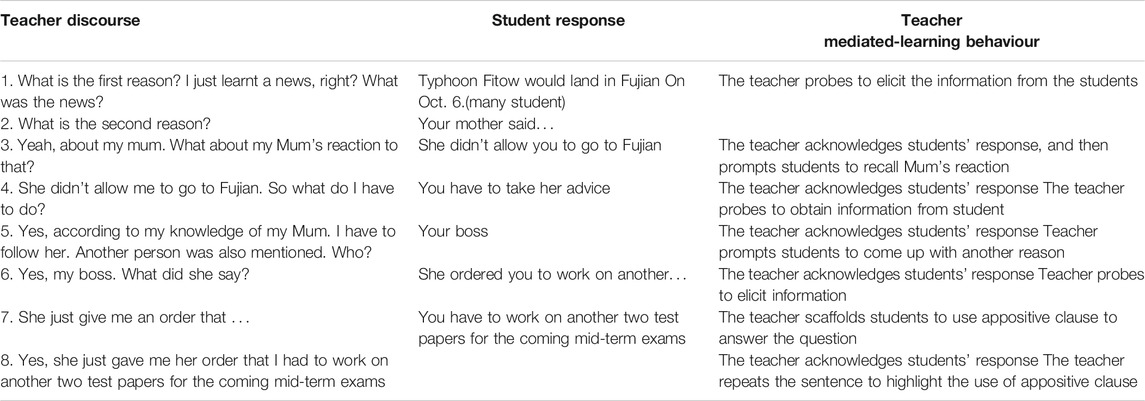

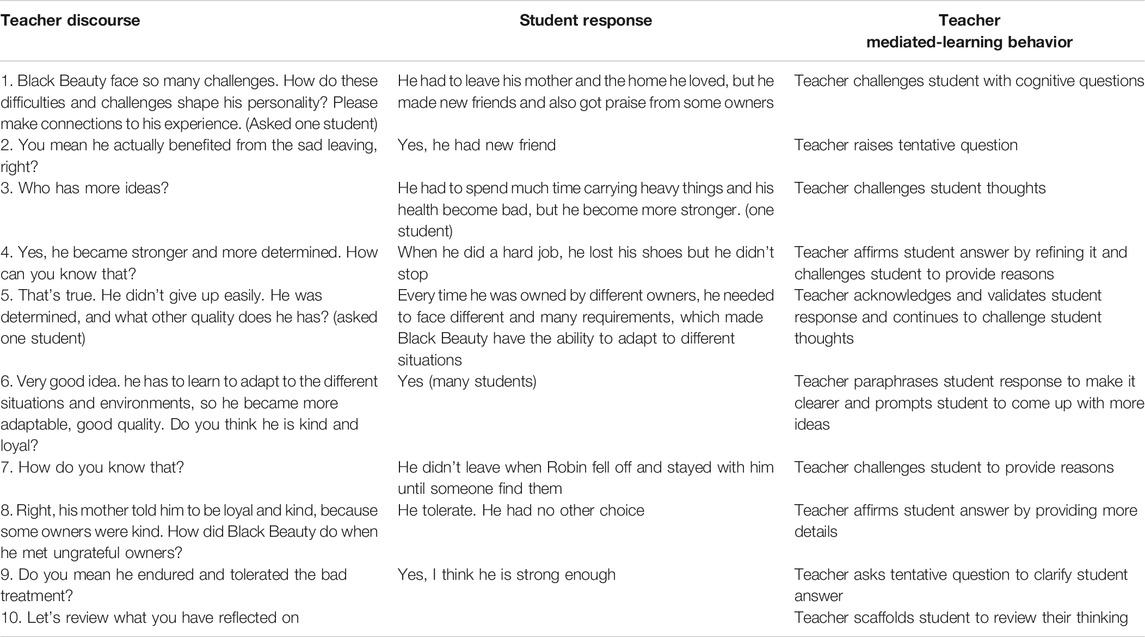

This lesson was targeting a reading text from the textbook. The topic was Thanksgiving Day. The teacher organized a series of activities to teach the text. The first extract (Table 3) was an introduction activity. The teacher was attempting to understand students’ knowledge about the topic. Given that the questions actually had fixed answers to them and the teacher asked to elicit the right answers, the session was categorized into display question.

This session of interaction involved teacher prompt (Turn 1), challenge (Turn 2,3,4,and5), and acknowledgment and validation (Turn 2, 3, 4, 5,and6), which was attributed to the teacher’s deliberate design of the task. The teacher changed the closed questions to open ones by inviting students to make free guess. She encouraged free thinking with positive and humorous comments. The students responded with interesting ideas and their free expression was enhanced.

In the second extract (Table 4), the teacher, Min, was simulating a situation for students to come up with some questions concerning Chinese festivals after talking about how the Thanksgiving Day was celebrated in the United States Students were encouraged to provide any idea freely, hence, this round of interaction was categorized into referential questions.

The teacher, in the extract above, transferred to the major question by probing students’ common knowledge. The following question was a referential question, raised by setting up a specific situation (Turn 2). When the student offered a clear response, the teacher acknowledged and validated it with encouraging words (Turns 3, 5, 6). As to those vague responses, the teacher affirmed their answers by repeating them in a clearer way to offer a better model for the whole class (Turns 4, 9). When the student mentioned “customs” in the response, the teacher prompted him to specify it (Turn 7). The teacher helped the student reflect on something that was not mentioned by other students through subsequent scaffolding discourses (Turn 8). With the teacher mediating discourse, the students reflected on their thinking and proposed some valid ideas.

Lesson by Li

This lesson was a literature study. The book “Black Beauty” was assigned to student to read two weeks before under the guide of a worksheet. On this lesson, the teacher guided students to reflect on their reading and probed students’ understanding of some details and the characters of the novel.

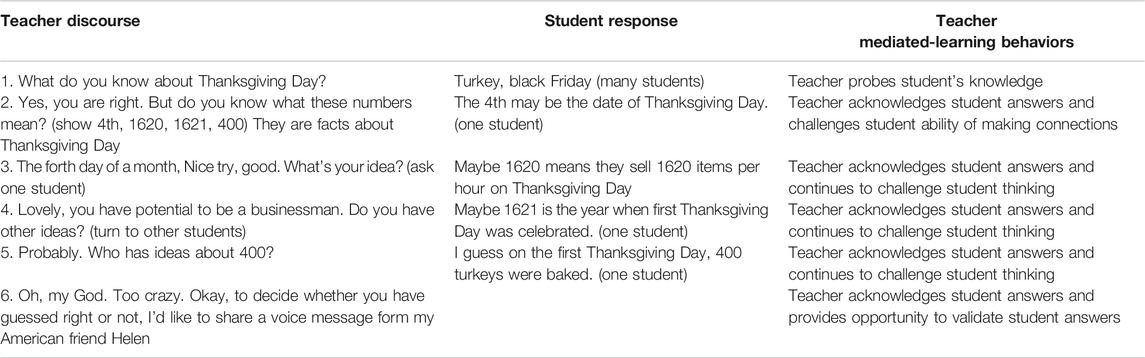

In Extract one (see Table 5), Teacher Li guided the students to reflect on their reading. The students read the sentences and the parts that impressed them deeply. The teacher prompted students to share their feelings and opinions about their reading. This session of interaction was centring on recalling specific details of the book and therefore was categorized as a display question.

This session of interaction was categorized into display question, but the teacher actually posed some referential questions to enhance student critical thinking and expression opportunity. During the interaction, the teacher applied mediated-learning behaviors such as focusing on issues (Turn 1), probing (Turn 2), asking tentative questions (Turn 3 and 7), challenging (Turn 5 and 8), and acknowledging and validating (Turn 4, 6, and 9). The students not only presented the sections they liked but also reflected on their feelings and understanding about the reading.

The second extract (Table 6) presented the interaction about students’ understanding and interpretation of the main character. It involved students’ personal ideas and opinions, so it was categorized to referential question.

This session of interaction required students to draw the correct connections, think critically, and express difficult ideas. The teacher’s discourses involved various mediated-learning behaviors. She started the interaction by asking a cognitive question (Turn 1) and continues to challenge student to provide more ideas (Turn 3, 4, 5, and 7). To assist students to generate better expression, the teacher asked tentative questions (Turn 2 and 9), paraphrased student answers and affirmed their responses by refining them (Turn 4, 6, and 8). At last the teacher scaffolded students to review all their ideas. During the interaction, the students were guided to reflect on their thinking and express their understanding.

Summary of the Sessions of Interaction

The six extracts above illustrate the teachers’ interactions with students, either individually or collectively, during whole-class teaching. Many of the questions the teachers posed to start the dialogues, whether referential questions or display questions, involved mediated-learning behaviors. For example, they posed probing questions to elicit information or ideas, promote students to think more about the current issues, cognitively challenge students to provide reasons, scaffold students’ construction or application of new knowledge, and validate and acknowledge students’ responses and efforts. These interactions with students drew on a range of discourse practice in the construction of meaning. Overall, teacher questions involving mediated-learning behaviors particularly serve as principal stimulus and scaffold for learning by creating opportunities for students to talk (Kohler, 2015).

Discussion

CA approach uses audio and video recordings of naturally occurring activities to study the details of interactions, moment—by—moment, by the participants within the very context of their activity (Mondada, 2013). The current study examines the details of teachers’ questions and students’ responses to identify patterns of their discourse. Therefore, the present study had two foci. First, the study demonstrated two types of teacher questions as “referential” or “display” oriented and the embedded mediated-learning behaviors in the interactions triggered by the two types of questions. Second, the study examined which type of question initiated the interactions that involved more mediated-learning behaviors and the pedagogical implications for teacher and classroom discourse.

As reviewed previously, there have been conflicting opinions concerning referential questions resulting in longer interactions and more complex responses. The findings of this study were in line with these arguments. The data included in the tables above indicated that the length of an interaction was decided by the topic under discussion or the design of the activity. The teacher controlled how deep or how extensive the topic would be investigated. Sometimes a display interaction was quite long (Take Table 2 as an example) because the material the teacher needed to cover was extensive or the teacher decided to extend some points aside reporting existing answers. This held true for referential questions. For example, in Table 4, the teacher enhanced student responses by promoting and scaffolding the student to provide clearer information. The complexity of the student response was evident in the number of connectors, the volume of description produced, and the degree of meaning negotiation appearing in the responses (Wright, 2016; Gould and Gamal, 2017). In this study, student responses to referential questions contained complete or compound sentences and involved cognitive thinking (For example, Turn 5 in Table 6 or Turn 8 and 9 in Table 1). Display questions could also elicit complex responses if teachers guided students to use more advanced expressions as the teacher did in Table 2 or if teachers deliberately designed the display interaction as the teacher did in Table 3.

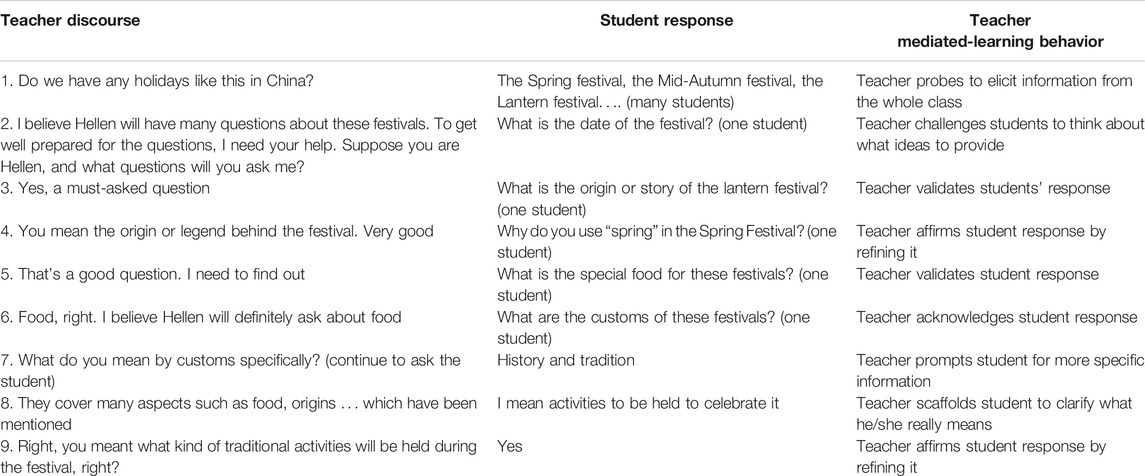

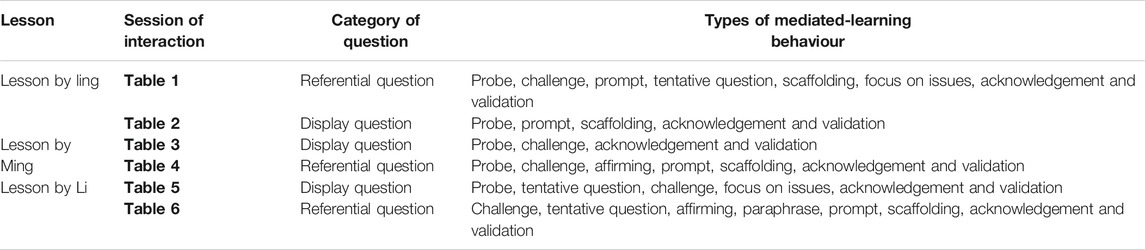

The following table (Table 7) provided an overview of the mediated-learning behaviors that the teachers demonstrated in the sessions of interactions extracted above. These behaviors were varied and ranged from simply probing for information to challenging the students’ perspectives on issues, from helping them clarify understandings to scaffolding their learning. In addition, the teachers also used strategies to assist the students to develop their thinking, refine their expression and focus their attention on key issues. They did this through the use of probes, prompts, challenges, affirmations, paraphrases, tentative questions, and scaffolding while continuing to acknowledge and validate students’ efforts and to extend their thinking (see Table 7).

The overview showed that the teachers tended to engage a wider variety of mediated-learning behaviors when they raised referential questions. Close observation of the data showed that if the teachers had further explored the use of referential questions during the display interaction session, there would have been more mediated-learning behaviors used other than probes and acknowledgements. For example, the teacher in Table 5 challenged student to provide reasons and opinions through questions “Why do you like this section?” and “What do you think of his mother’s words?”

The discussion about length of interaction, complexity of responses and teacher mediated-learning behavior indicated that the way how teacher delivered the questions to the students had an important effect on students’ responses (Affandi, 2016). Obviously, the teacher’s role as a mediator was very important. Teacher-student mediating interaction involved more explication, initiating solutions, asking leading questioning, analyzing language and using metalanguage (Guk and Kellogg, 2007). Teacher mediation was a matter of mediating language, culture and thinking through teaching strategies (Kohler, 2015). In this study, the teaching strategies meant lesson design and teacher questioning techniques. Teacher questions were very important for increasing cognitive demands in learning and different types of questions would create different learning opportunities (Tsui, 2001). If the questions the teacher used were able to enhance student interest and involvement, create cognitive conflict, challenge assumption, provoke cognitive thinking and lead to new knowledge, the questions would be powerful teaching strategies (Brown and Wragg, 2001; Cotton, 2003).

Both types of questions this study examined could facilitate student participation in an interactional structure (David, 2007; Ozcan, 2010; Zohrabi, et al., 2014), but referential interaction involved a larger variety of mediated-learning behaviors. Mediated-learning behaviors in teachers’ questions contributed to students’ comprehensible output. When teachers engaged in the interactions where they mediated students to think about an issue critically and thoroughly, students would, in turn, learn how the target language could be used to mediate new learning and construct new understanding (Mercer et al., 1999; Webb, 2009). Mediating occurs at the content level, and also cognitive level (Takahashi et al., 2000). This finding concurred with the research by Wright (2016), which found that the use of referential questions may lead to more enhanced student response and increased cognitive activity. The display interactions in the current study still had the function of checking knowledge and practicing speaking as claimed by many researchers (e.g., Burns and Myhill, 2004; McCarthy, 1991). They had been enhanced when the teacher managed to make the dialogue an authentic communication by employing referential questions to challenge and prompt further thinking. Referential questions were indeed authentic in nature (Wright, 2016).

The study has implications for teaching. It is expected that teachers promote higher-order thinking and reasoning among their students to enhance learning (Kuhn et al., 1997; Rojas-Drummond and Mercer, 2003), so it is important that teachers use mediated-learning behaviors in their dialogical interaction with their students to challenge students’ thinking and scaffold their learning (Gillies, 2008). Since the classroom interactions triggered by referential questions involve more mediated-learning behaviors, teachers are advised to employ more referential questions in class and use various mediated-learning strategies to guide the dialogical exchanges. Given that display interactions are common during whole-class teaching (Lee, 2006), teachers should try to design them carefully and utilize more mediated-learning strategies to make the interaction go beyond just probing—response—acknowledgement.

It is acknowledged that the current study is not without its limitations. The study focuses only on a small sample of high school teachers (five teachers) and no teacher or student interview was included. In addition, if students’ discourses during group discussion in the later section of the lessons had been recorded, the data would have reflected the effectiveness of teacher discourse on student learning. These are issues that further studies may address.

Conclusion

There is no doubt teachers’ talk has the capacity to stimulate and extend students’ cognitive thinking and advance their learning when they use effective questioning strategies. The study examined two types of questions (display and referential) the teachers used during whole-class instruction. It was demonstrated that interactions triggered by both types of question could be extended and student responses to them could be complex, if teachers deliberately used these questioning strategies. However, more mediated-learning behaviors were identified in the interactions initiated by referential questions. When the teachers posed referential questions, they were more likely to use mediated-learning behaviors to prompt, challenge, and scaffold students’ understandings, and encourage them to explicate their reasoning and thinking. As Shu (2014) suggested referential questions, compared with display questions, could generate more opportunities for a higher level of student speech and negotiation of meaning. Therefore, teachers are encouraged to use referential questions whether in display interactions or in referential interactions.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Shanghai No. 2 High School; Shanghai Wei Yu High School; Shanghai Qi Bao High School; Shanghai Xin Zhuang High School. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants and apos; legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

HL used to be a secondary school English teacher in Shanghai, China. Her major research interests are in foreign language teaching, teacher development, and classroom discourses. She has authored a few journal articles. HL is going to start a career in tertiary education. RG and apos; major research interests are in the learning sciences, classroom discourses, small group processes, including co-regulated learning, classroom instruction, student behavior, and students with disabilities. RG has worked extensively in both primary and secondary schools to embed STEM education initiatives into the science curriculum. She has authored more than one hundred journal articles and a few books.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Affandi, Y. (2016). Teacher’s Display and Referential Questions. Nobel 7 (1), 65–77. doi:10.15642/nobel.2016.7.1.65-77

Al-Zahrani, M. Y., and Al-Bargi, A. (2017). The Impact of Teacher Questioning on Creating Interaction in EFL: A Discourse Analysis. Elt 10 (6), 135–150. doi:10.5539/elt.v10n6p135

Arifin, T. (2012). Analyzing English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Classroom Interaction. APPLE3L J. 1 (1), 1–20. doi:10.22215/etd/2019-13853

Bell, T., Urhahne, D., Schanze, S., and Ploetzner, R. (2010). Collaborative Inquiry Learning: Models, Tools, and Challenges. Int. J. Sci. Edu. 32 (3), 349–377. doi:10.1080/09500690802582241

Berry, R. A. W. (2006). Teacher Talk during Whole-Class Lessons: Engagement Strategies to Support the Verbal Participation of Students with Learning Disabilities. Learn. Disabil Res Pract 21 (4), 211–232. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5826.2006.00219.x

Brock, C. A. (1986). The Effects of Referential Questions on ESL Classroom Discourse. TESOL Q. 20 (1), 47–59. doi:10.2307/3586388

Cotton, K. (2003). Classroom Questioning: School Improvement Research Series. Portland, OR: Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory.

Creemers, B. P. M., and Kyriakides, L. (2006). Critical Analysis of the Current Approaches to Modelling Educational Effectiveness: The Importance of Establishing a Dynamic Model. Sch. Effect. Sch. Improve. 17 (3), 347–366. doi:10.1080/09243450600697242

David, F. O. (2007). Teachers’ Questioning Behavior and ESL Classroom Interaction Pattern. Human. Soc. Sci. J. 2 (2), 127–131. doi:10.33915/etd.721

Deppermann, A. (2013). Multimodal Interaction from a Conversation Analytic Perspective. J. Pragmatics 46 (1), 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2012.11.014

Edstrom, A. (2015). Triads in the L2 Classroom: Interaction Patterns and Engagement during a Collaborative Task. System 52, 26–37. doi:10.1016/j.system.2015.04.014

Ekembe, E. E. (2014). Interaction and Uptake in Large Foreign Language Classrooms. RELC J. 45 (3), 237–251. doi:10.1177/0033688214547036

Erlinda, R., and Dewi, S. R. (2016). Teacher's Questions in Efl Classroom. Jt 17 (2), 177–188. doi:10.31958/jt.v17i2.271

Gillies, R. M., and Boyle, M. (2008). Teachers' Discourse during Cooperative Learning and Their Perceptions of This Pedagogical Practice. Teach. Teach. Edu. 24 (5), 1333–1348. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2007.10.003

Gillies, R. M., and Boyle, M. (2006). Ten Australian Elementary Teachers' Discourse and Reported Pedagogical Practices during Cooperative Learning. Elem. Sch. J. 106 (5), 429–452. doi:10.1086/505439

Gillies, R. M., and Haynes, M. (2011). Increasing Explanatory Behaviour, Problem-Solving, and Reasoning within Classes Using Cooperative Group Work. Instr. Sci. 39 (3), 349–366. doi:10.1007/s11251-010-9130-9

Gillies, R. M. (2006). Teachers' and Students' Verbal Behaviours during Cooperative and Small-Group Learning. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 76 (2), 271–287. doi:10.1348/000709905x52337

Gillies, R. M. (2008). “Teachers’ and Students’ Verbal Behaviours during Cooperative Learning,” in The Teacher’s Role in Implementing Cooperative Learning in the Classroom. Computer Supported Collaborative Learning Series. Editors R. Gillies, A. Ashman, and J. Terwel (New York: Springer), 8, 238–257. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-70892-8_12

Gillies, R. M. (2004). The Effects of Communication Training on Teachers’ and Students’ Verbal Behaviours during Cooperative Learning. Int. J. Educ. Res. 41 (3), 257–279. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2005.07.004

Gould, F., and Gamal, M. (2017). A Study on the Effect of Referential and Display Questions and Differing Feedback Strategies on Japanese EFL Students in an Oral Communication Class. J. Glob. media Stud. gms= ジャーナル・オブ・グローバル・メディア・スタディーズ 20, 37–48. doi:10.25134/ieflj.v2i1.634

Guk, I., and Kellogg, D. (2007). The ZPD and Whole Class Teaching: Teacher-Led and Student-Led Interactional Mediation of Tasks. Lang. Teach. Res. 11 (3), 281–299. doi:10.1177/1362168807077561

Halim, A., and Mazlina, H. (2018). Questioning Skill of Science Teacher from the Students Perspective in Senior High School. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1088 (1), 012109. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1088/1/012109

Halstead, J. M., and Zhu, C. (2009). Autonomy as an Element in Chinese Educational Reform: A Case Study of English Lessons in a Senior High School in Beijing. Asia Pac. J. Edu. 29 (4), 443–456. doi:10.1080/02188790903308944

Hamel, E., Joo, Y., Hong, S. Y., and Burton, A. (2020). Teacher Questioning Practices in Early Childhood Science Activities. Early Child. Edu. J. 7, 1–10. doi:10.1007/s10643-020-01098-6

Hargreaves, D. H. (1984). Teachers' Questions: Open, Closed and Half‐open. Educ. Res. 26 (1), 46–51. doi:10.1080/0013188840260108

Hasan, R. (2002). “Semiotic Mediation and Mental Development in Pluralistic Societies: Some Implications for Tomorrow’s Schooling,” in Learning for Life in the 21st Century. Sociocultural Perspectives on the Future of Education. Editors G. Wells, and G. Claxton (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing), 112–126.

Hertz-Lazarowitz, R., and Shacher, H. (1990). “Teachers’ Verbal Behavior in Cooperative and Whole-Class Instruction,” in Cooperative Learning. Editor S. Sharan (New York: Praeger), 77–94.

Ho, D. G. E. (2005). Why Do Teachers Ask the Questions They Ask? RELC J. 36 (3), 297–310. doi:10.1177/0033688205060052

Hong, Y. (2006). A Report of an ESL Classroom Observation in Two Language Schools in Auckland. TESL Can. J./Revue TESL du Can. 23 (2), 1–11. doi:10.18806/tesl.v23i2.52

Hu, G. (2002). Potential Cultural Resistance to Pedagogical Imports: The Case of Communicative Language Teaching in China. Lang. Cult. Curriculum 15 (2), 93–105. doi:10.1080/07908310208666636

Huang, F. (2004). Curriculum Reform in Contemporary China: Seven Goals and Six Strategies. J. Curriculum Stud. 36 (1), 101–115. doi:10.1080/002202703200004742000174126

Jin, L., and Cortazzi, M. (1998). Dimensions of Dialogue: Large Classes in China. Int. J. Educ. Res. 29 (8), 739–761. doi:10.1016/s0883-0355(98)00061-5

Johnson, K. E. (2009). Second Language Teacher Education: A Sociocultural Perspective. Upper Saddle River: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203878033

King, A. (2002). Structuring Peer Interaction to Promote High-Level Cognitive Processing. Theor. into Pract. 41 (1), 33–39. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip4101_6

Kohler, W. (2015). The Task of Gestalt Psychology. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. doi:10.1515/9781400868964

Kozulin, A. (2003). “Psychological Tools and Mediated Learning,” in Vygotsky’s Educational Theory in Cultural Context. Editors A. Kozulin, B. Gindis, V. S. Ageyev, and S. M. Miller (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 15–38. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511840975.003

Kozulin, A. (2002). Sociocultural Theory and the Mediated Learning Experience. Sch. Psychol. Int. 23 (1), 7–35. doi:10.1177/0143034302023001729

Kuhn, D., Shaw, V., and Felton, M. (1997). Effects of Dyadic Interaction on Argumentive Reasoning. Cogn. Instruction 15 (3), 287–315. doi:10.1207/s1532690xci1503_1

Lantolf, J. P., and Thorne, S. L. (2006). Sociocultural Theory and the Genesis of Second Language Development. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Lee, Y.-A. (2006). Respecifying Display Questions: Interactional Resources for Language Teaching. TESOL Q. 40 (4), 691–713. doi:10.2307/40264304

Lillydahl, D. (2015). Questioning Questioning: Essential Questions in English Classrooms. English J. 104 (6), 36–39. doi:10.4324/9781315676203-43

Liu, W. (2016). The Changing Pedagogical Discourses in China. Etpc 15 (1), 74–90. doi:10.1108/etpc-05-2015-0042

Liu, W., and Wang, Q. (2020). Walking with Bound Feet: Teachers' Lived Experiences in China's English Curriculum Change. Lang. Cult. Curriculum 33 (3), 242–257. doi:10.1080/07908318.2019.1615077

Long, M., and Sato, C. (1983). “Classroom Foreigner Talk Discourse: Forms and Functions of Teachers’ Questions,” in Classroom Oriented Research in Second Language Acquisition. Editors H. Seliger, and M. Long (Rowley, MA: Newbury House), 268–285.

McCarthy, M. (1991). Discourse Analysis for Language Teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McNeil, L. (2012). Using Talk to Scaffold Referential Questions for English Language Learners. Teach. Teach. Edu. 28 (3), 396–404. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2011.11.005

Mercer, N., Wegerif, R., and Dawes, L. (1999). Children’s Talk and the Development of Reasoning in the Classroom. Br. Educ. Res. J. 25 (1), 95–111. doi:10.1080/0141192990250107

Mondada, L. (2013). The Conversation Analytic Approach to Data Collection. The Handbook of Conversation Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 32–56.

Ozcan, S. (2010). The Effects of Asking Referential Questions on the Participation and Oral Production of Lower Level Language Learners in Reading Classes. Unpublished MA Dissertation. New York: Middle East Technical University.

Palincsar, A. S. (1998). Social Constructivist Perspectives on Teaching and Learning. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 49 (1), 345–375. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.345

Peng, J.-E. (2011). Changes in Language Learning Beliefs during a Transition to Tertiary Study: The Mediation of Classroom Affordances. System 39 (3), 314–324. doi:10.1016/j.system.2011.07.004

Philp, J., and Tognini, R. (2009). Language Acquisition in Foreign Language Contexts and the Differential Benefits of Interaction. IRAL-Int. Rev. Appl. Linguist. Lang. Teach. 47 (3–4), 245–266. doi:10.1515/iral.2009.011

Qashoa, S. H. (2013). Effects of Teacher Question Types and Syntactic Structures on EFL Classroom Interaction. Int. J. Soc. Sci. 7 (1), 52–62. doi:10.17077/etd.ah4k7h3s

Richards, J. C., and Schmidt, R. (2010). Longman Dictionary of Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics. 4th ed. Harlow, UK: Longman.

Rojas-Drummond, S., and Mercer, N. (2003). Scaffolding the Development of Effective Collaboration and Learning. Int. J. Educ. Res. 39 (1), 99–111. doi:10.1016/s0883-0355(03)00075-2

Ruddick, M. (2011). An Investigation of Question Types Used in an EFL Pre-intermediate Classroom. Bull. Niigata Univ. Int. Inform. Stud. Depart. Inform. Culture 14, 41–62. doi:10.3726/978-3-653-04297-9/17

Rutten, N., van der Veen, J. T., and van Joolingen, W. R. (2015). Inquiry-based Whole-Class Teaching with Computer Simulations in Physics. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 37 (8), 1225–1245. doi:10.1080/09500693.2015.1029033

Schur, Y., and Kozulin, A. (2008). Cognitive Aspects of Science Problem Solving: Two Mediated Learning Experience Based Programs. J. Cogn. Educ. Psych 7 (2), 266–287. doi:10.1891/194589508787381818

Shen, P. (2012). A Case Study of Teacher’s Questioning and Students’ Critical Thinking in College EFL Reading Classroom. Int. J. English Linguistics 2 (1), 199–206. doi:10.5539/ijel.v2n1p199

Shomoosi, N. (2004). The effect of teachers' questioning behavior on EFL classroom interaction: a classroom research study. The Reading Matrix 4 (2), 96–104.

Shu, L. Z. (2014). An Empirical Study on Questioning Style in Higher Vocational College English Classroom in China. English Lang. Lit. Stud. 4 (2), 6–13. doi:10.5539/ells.v4n2p6

Smetana, L. K., and Bell, R. L. (2013). Which Setting to Choose: Comparison of Whole-Class vs. Smallgroup Computer Simulation Use. J. Sci. Edu. Tech. 23 (4), 1–15. doi:10.1007/s10956-013-9479-z

Smyth, P., and Carless, D. (2020). Theorising How Teachers Manage the Use of Exemplars: towards Mediated Learning from Exemplars. Assess. Eval. Higher Edu. 6, 1–14. doi:10.1080/02602938.2020.1781785

Stivers, T. (2015). Coding Social Interaction: A Heretical Approach in Conversation Analysis? Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 48 (1), 1–19. doi:10.1080/08351813.2015.993837

Stivers, T., and Sidnell, J. (2005). Introduction: Multimodal Interaction. Semiotica 2005 (156), 1–20. doi:10.1515/semi.2005.2005.156.1

Takahashi, E., Austin, T., and Morimoto, Y. (2000). “Social Interaction and Language Development in a FLES Classroom,” in Second and Foreign Language Learning through Classroom Interaction. Editors J. K. Hall, and L. S. Verplaetse (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum), 139–161.

Tan, Z. (2007). Questioning in Chinese University EL Classrooms. RELC J. 38 (1), 87–103. doi:10.1177/0033688206076161

Tsui, A. B. M. (2001). “Classroom Interaction,” in The Cambridge Guide to Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages. Editors R. Carter, and D. Nunan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 120–125. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511667206.018

Varela, T., Palaré, O., and Menezes, S. (2020). The Enhancement of Creative Collaboration through Human Mediation. Edu. Sci. 10 (12), 347. doi:10.3390/educsci10120347

Vygotsky, L., and Luria, A. (1993). Studies on the History of Behavior: Ape, Primitive, and Child. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Webb, N. M. (2009). The Teacher's Role in Promoting Collaborative Dialogue in the Classroom. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 79 (1), 1–28. doi:10.1348/000709908x380772

Williams, M., and Burden, R. (1997). Psychology for Language Teachers, a Social Constructivist Approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Wright, B. M. (2016). Display and Referential Questions: Effects on Student Responses. Nordic J. English Stud. 15 (4), 160–189. doi:10.35360/njes.388

Yang, C. C. R. (2010). Teacher Questions in Second Language Classrooms: An Investigation of Three Case Studies. Asian EFL J. 12 (1), 181–201. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139524469.005

Keywords: whole-class instruction, teacher questions, referential questions, display questions, mediated-learning behavior

Citation: Liu H and Gillies RM (2021) Teacher Questions: Mediated-Learning Behaviors Involved in Teacher-Student Interaction During Whole-Class Instruction in Chinese English Classrooms. Front. Educ. 6:674876. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.674876

Received: 02 March 2021; Accepted: 23 April 2021;

Published: 04 May 2021.

Edited by:

Lawrence Jun Zhang, University of Auckland, New ZealandReviewed by:

Barry Bai, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Liu and Gillies. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Huifang Liu, aHVpZmFuZ2xpdWdyYWNlQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Huifang Liu

Huifang Liu Robyn M. Gillies

Robyn M. Gillies