95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 13 May 2021

Sec. Special Educational Needs

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.666574

This article is part of the Research Topic Education, Forced Migration, and Disability View all 5 articles

Children and young people with special educational needs and disabilities and their families are likely to be significantly affected by the Covid-19 pandemic at various levels, particularly given the implementation of school closures during national lockdowns. This study employed a survey design to assess parental perspectives on the impact of school closures and of returning to school in England, as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. Eighty-three parents of children and young people with various types of need responded to the survey between September and December 2020. The survey included multiple choice questions and open-ended questions for further in-depth examination of parental perspectives. Results show that: the majority of parents reported that school closures had a detrimental effect on their children’s mental health (particularly those from the most deprived neighbourhoods) and on their own mental and physical health (particularly for ethnically diverse parents and for those whose children attend specialized settings); returning to school was considered to have a positive impact on children’s mental and physical health for the vast majority of parents, despite fearing exposure to the virus; many parents have reported that their children were calmer and happier at home during school closures and became more anxious and stressed upon returning to school. The role of cumulative risk in these children and families, as well as the role of schools as key support agents for the most vulnerable are discussed with implications for future research and policy.

This paper describes the findings of a survey issued to English parents of children and young people with special educational needs and disabilities about the impact of school closures and of returning to school on both children and parents, as a consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020. It also looks at the impact of returning to school. The survey was issued between October 2020 and January 2021, when the first wave of the pandemic had passed in England, and schools had reopened. Results show that parents of deprived neighbourhoods were more likely to report detrimental effects of school closures on their children’s mental health; parents of children attending specialized settings and of girls were more likely to report negative effects of school closures on their children’s physical health; and ethnically diverse parents reported detrimental effects on their own physical and mental health. The vast majority of parents considered returning to school beneficial for their children, but some have mentioned it has been worse for them, raising questions (that need to be addressed in the post-pandemic world) as to whether our schools are serving all children with special needs in a fair and equitable way. For some, returning to school represented a return to anxiety and emotional issues, thus, policy and practice need to rethink the role of future schools as key sources of support to all children with special educational needs and disabilities.

Since its identification in late 2019 in Wuhan, China, the virus associated with Covid-19 has spread quickly worldwide (World Health Organization, 2020a). In England, the first national lockdown in response to the pandemic was announced in March 2020, to help bring to a halt the fast spread of the disease in the country. This included school closures, nationally, with the exception of children of key workers, who were still allowed to attend school, as it has been the case in other countries. By April 2020, schools in 189 countries had closed (World Health Organization, 2020b). While it has been well documented that children directly affected by Covid-19 are rarely severely affected by the disease (e.g. Ladhani et al., 2020), the indirect effects of the pandemic on children’s overall wellbeing and mental health are still yet to be seen to their full extent, particularly the impact of school closures and homeschooling. It will be important, in the coming months to years, to fully ascertain the mental health and wellbeing issues stemming from the pandemic in children and their families, as well as the prevalence of these issues at country-level, including potential positive outcomes. Conversely, it has been argued that there might be a silver lining to the psychological impact of the pandemic on children and young people, particularly for the most vulnerable, who for example, often are victims of bullying in school context, or potentially more exposed to risky behavior when going to school; for these, being at home might have provided temporary relief or protection (Chawla et al., 2020).

Examining the experiences of vulnerable groups, particularly of children and young people with special educational needs and/or disabilities (SEND) and their families, is of particular relevance when considering the long-term mental health and wellbeing consequences of the pandemic. Parents of children with SEND are likely to have seen increased levels of anxiety and associated symptoms with the pressure of having to care for their vulnerable children without the usual support received from schools, during lockdown. A study with Indian parents of children with SEND has shown significantly enhanced depression, anxiety and stress symptoms after the outbreak, compared to pre-Covid levels (Dhiman et al., 2020). This can vary with personal circumstances, such as type and severity of the child’s need; for example, a study conducted in China showed that parents of children with autism spectrum disorder were more likely to suffer from mental health issues, during lockdown, when compared to parents whose children had an intellectual disability or a visual or hearing impairment (Chen et al., 2020). Regarding the psychological effects of the pandemic on children, a review by (Singh et al., 2020) concluded that the quality and magnitude of the impact is determined by vulnerability factors like developmental age, educational status, pre-existing mental health condition, being economically underprivileged or being confined due to infection or fear of infection, thus suggesting that children and young people with SEND are potentially more likely to suffer negatively from the impacts of the pandemic.

While some of the learning experiences for children with SEND can be moved to online platforms for continued support, this becomes less straight-forward for children and young people who, in addition to having SEND, also come from a socioeconomically deprived background: these have fewer resources and are much more reliant on meals offered by schools, as well as on their playground facilities for exercise and play, when compared to children with SEND from more affluent backgrounds (Crawley et al., 2020). (Andrew et al., 2020) examined children’s experiences of home learning during the first national lockdown in England and found considerable heterogeneity, which was strongly associated with family income; for children with SEND, who are also socioeconomically vulnerable, the effects of this cumulative risk are likely to place them in severe disadvantage. The issue of school closure is, therefore, open to debate, with some considering it as a necessary measure, while others defending that it has little impact in preventing deaths in adults (Viner et al., 2020). Conversely, it can have multiple impacts on children in terms of education, social isolation, well-being and child protection (Crawley et al., 2020).

In England, children and young people with SEND must have the provision required to meet their needs documented in an Education Health and Care (EHC) plan, the official statutory document regulating support provided; however, according to Crawley and colleagues (2020), these have not been adapted for home learning, and much of this provision cannot be delivered outside a specialized setting. In a study by (Asbury et al., 2020), parents of children with SEND in England reported feeling overwhelmed with the demands of the caring role during the first country-wide lockdown, but data suggested that more parents than children had seen an increase in anxiety and stress; interestingly, for a small proportion of parents in that study, homeschooling and confinement has had a positive effect on their children’s behavior and development, perhaps an indication of the silver lining mentioned above (Chawla et al., 2020).

The current system of provision and education for children with SEND in England is already subject to a number of criticisms, including about the process by which children become eligible for statutory support, the poor quality of the EHC plans documenting their needs and provision, and the extent to which children’s and families’ voices and concerns are taken into account in the planning and decision-making process about their education (Castro and Palikara, 2016; Palikara et al., 2018; Castro-Kemp et al., 2019). Therefore, it is somewhat unsurprizing that, for some, homeschooling became a better alternative. In any case, the pandemic added pressures to the SEND system in England, particularly to schools and school staff, raising questions related to how we can best support children and young people who are likely to be affected by the circumstances, as well as their parents, especially those who cannot access resources in an equitable way.

Whilst most of the studies described above focused on the national lockdown period, little is known about children and parental health and wellbeing upon returning to school in the post post-lockdown period, in the Autumn of 2020. This study aimed to ascertain the impact of the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic on the physical and mental health status of children and young people with SEND and of their parents in England, from the parents’ point of view, with a focus on experiences of school closure (in March 2020) and of returning to school (from September to December 2020). To achieve this aim, the following research questions were formulated: 1) How did parents of children with special educational needs and disabilities perceive the impact of school closures on their children’s mental and physical health? 2) How did parents of children with special educational needs and disabilities perceive the impact of school closures on their own mental and physical health? 3) How do parents of children with special educational needs and disabilities perceive the experience of schools’ reopening after the 2020 national lockdown? 4) to what extent do parental perceptions vary according to personal characteristics (child’s age, type of disability/need, child’s gender, ethnic background, type of setting attended and socioeconomic level of the postcode)?

The present study employs a survey design to assess parental perspectives on the impact of school closures and of returning to school in England, as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. Data was collected between October and December 2020 following ethical approval by the Ethics Committee of the host higher education institution. All data was anonymous and informed consent was obtained from respondents prior to initiating the survey.

The study employed a purposive sample, with contacts made nation-wide amongst the large networks of professional relationships that the research team fosters. Parent associations, forums and support groups were approached for dissemination of the survey among their followers and members, as well as professional organisations with parental links. The survey was kept open from October 2020 until early January 2021, when a second national lockdown was imposed in England, with new school closures. All respondents up to this point were included in the sample.

In England, children and young people with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities receive special education provision as stipulated in their Education Health and Care (EHC) plans, in accordance with the regulating policy, the Children and Families Act 2014. The most common type of need among children in receipt of an EHC plan, as classified by the Government of the United Kingdom, is Autism Spectrum Disorder, followed by other very common categories such as Speech, Language and Communication Needs, Social, Emotional and Mental Health needs, Moderate Learning Difficulties and Severe Learning Difficulties (UK Government, 2020). However, some children and young people with SEND are not considered to have a formal or diagnosable disability and therefore may not be in receipt of statutory provision and of an EHC plan, but they are integrated in a parallel system designated “SEND support”, in which individualized provision is also put in place. The numbers of both children with statutory provision and SEND support have been increasing steadily over the last few years. The Education system in England is also very heterogeneous in terms of type of school. Children and young people with SEND can attend a mainstream school, a special school or a specialized unit in a mainstream school. Almost all students in special schools (97.9%) have statutory support and an EHC plan. Moreover, the current policy regulating provision for children and young people with SEND in England covers education up to 25°years of age, thus supporting the transition of young people from secondary school to post-16 education.

Table 1 summarizes the demographic data of the respondents to the survey. Eighty-three parents responded to the online survey between October and December 2020. The mean age of their children at the time of response was 10.5 years (SD = 3.87; min = 3, max = 24). Eighteen children were aged 3–7°years, 32 children were aged 8 to 11 and 33 young people were 12°years old or above. Twenty-nine children and young people were female and 54 were male.

A wide range of disabilities and special educational needs were reported by the parents (What type of special educational need and/or disability does your child have?). For the purpose of enabling inferential analysis on this data, the reported disabilities and special needs were categorized into autism (n = 35), physical and sensory disabilities and difficulties (including children with cerebral palsy, blindness and deafness) (n = 7), autism with other co-morbidities (e.g. ADHD) (n = 10), various genetic syndromes (including Williams Syndrome, Jourbet syndrome and Down’s syndrome, for example) (n = 9) and other types (including Fetal Alcoholic Spectrum Disorder, learning, emotional, and behavioral difficulties not necessarily categorized within a diagnosis) (n = 22).

Forty children and young people were attending a mainstream education setting when the national lockdown was announced, 32 were attending a specialized education setting and 11 were attending a specialized unit in a mainstream setting.

Twenty-one parents described their children as having a background classified as BAME (Black, Asian or Minority Ethnic), including Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Indian, Chinese, Black Caribbean, Black African and mixed, and 54 parents characterized their children as white; for 8 parents there was no information on ethnicity and the cases were treated as missing values. In terms of geographical distribution, the named Local Authorities were classed into groups based on the Index of Deprivation Affecting Children (IDACI), which is considered to be a good indicator of socioeconomic level in the United Kingdom, when individual or family income is not available (McLennan et al., 2019). The index is based on the proportion of children aged 0–15 who live in income deprived households in each Local Authority of the country, according to population-wide data available (e.g. census); the more deprived one area is, the higher their IDACI score will be. The ranked position of each local authority is publicly available on the government managed digital platforms. However, to ensure anonymity of participants, the actual local authorities referred to in this study were classed into 3 categories. The sample represents top IDACI positions (the most deprived) (n = 28), mid-range IDACI (n = 19) and bottom IDACI positions (the most affluent) (n = 34), reflecting a good distribution in terms of deprivation that can affect children. For 2 parents this information was not available, and the cases were treated are missing values.

An online survey developed by the research team was designed to be brief, simple and user-friendly. Using a free online survey tool, and a mixture of open-ended and multiple-choice questions, the survey included: 1) demographic questions concerning child’s age, gender, ethnic background, type of special need and/or disability, type of educational setting and local authority (postcode); 2) items concerning the effects of school closures: Did your child stay at home during the spring 2020 school closures? Do you think that school closures had a detrimental effect on your child’s mental health? (Please tell us why); Do you think that school closures had a detrimental effect on your child’s physical health? Do you think that school closures had a detrimental effect on YOUR physical and/or mental health (please tell us why); and 3) items on returning to school: Now that schools have reopened, is your child back at school? How pleased are you with the measures put in place by your child’s school to ensure Covid safety (please tell us why), Do you think that returning to school has had a positive impact on your child’s mental health (please tell us why), Do you think that returning to school has had a positive impact on your child’s physical health? and How do YOU feel about your child returning to school? The survey was piloted with two parents before being sent out to contacts, where minor changes were suggested to wording of questions and options.

Descriptive statistics (frequencies and crosstabulation) were run for all items. To examine the role of the demographic variables on parental perceptions of school closures, a series of logistic regression models were run to ascertain the role of demographic variables (ethnicity, IDACI, gender, age, type of disability and type of educational setting) on parental perceptions (classed as binary answers); all variables were categorical, and some were recoded to meet the requirement of a minimum number of expected cases per expected observation. For example, ethnic background was recoded into two categories which are commonly recognized in England: Black, Asian or Ethnic Minority (BAME) and White. Local authorities were classified into three categories with reference to IDACI raking. Assumptions for logistic regression were met in all cases (categorical dependent variables, independence of observations, little or no multicollinearity, linearity of independent variables and log odds) (Field, 2013).

For open-ended items, thematic analysis was conducted, by creating clusters of meaning, derived from the short statements that participants provided, which in turn combine into themes in an inductive process of narrowing data (Creswell, 2012; Guest et al., 2014).

The purpose of this study was to ascertain the impact of the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic on the physical and mental health of children and young people with SEND and their parents in England, from the parents’ point of view, and with a focus on school closures (which happened in March 2020) and on returning to school (from September to December 2020). Differences were examined between geographical areas, children’s ethnic background, educational setting type attended by the children, children’s gender, age and type of need.

Respondents were asked about their children’s physical and mental health during the 2020 first national lockdown. The vast majority of parents (n = 81) reported that their children stayed at home during that period, not attending school.

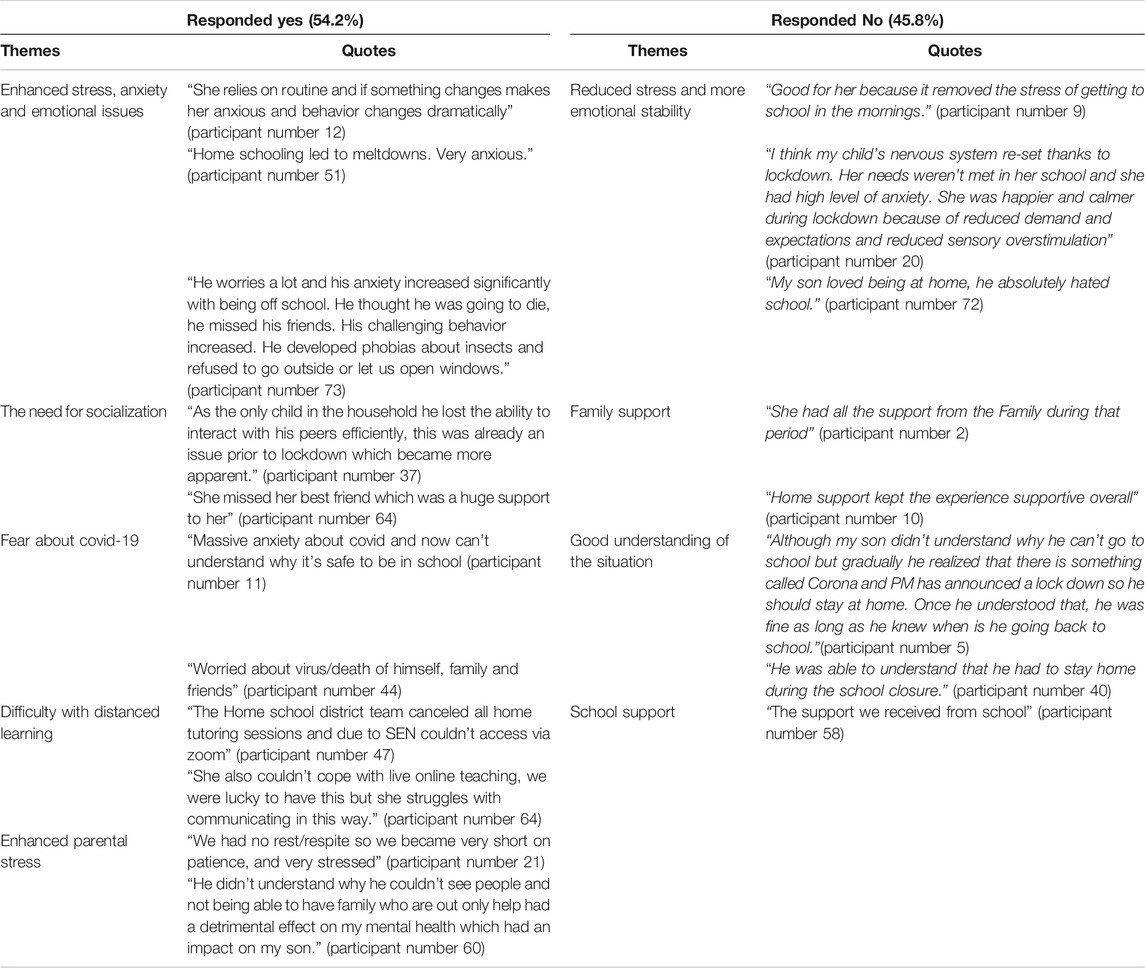

Forty-five parents (54.2%) said that they believed the 2020 national lockdown had a detrimental effect on their child’s mental health, while 38 parents reported that this was not the case (45.8%). Parents were asked to briefly justify their responses, and these justification statements were categorized into themes; a summary of these themes with examples of responses are presented in Table 2. For those who believed that the lockdown has had a detrimental effect on their children’s mental health, the most frequent theme was enhanced stress, anxiety and emotional issues, followed by the need for socialization; other themes found were fear about covid-19, difficulty with distanced learning and enhanced parental stress. For those who believed that there was no detrimental effect of lockdown on children’s mental health, the most common theme in justifying these answers was reduced stress and more emotional stability, immediately followed by family support and good understanding of the situation. One participant only mentioned school support.

TABLE 2. Themes and quotes resulting from the analysis of responses to the items “Do you think that school closures had a detrimental effect on your child’s mental health?” and “Please tell us why”.

Parents were also asked whether they thought school closures have had a detrimental effect on their children’s physical health; Forty-two parents responded “yes” (50.6%) and 41 responded “no” (49.4%). It should be noted that the two parents whose children continued attending school throughout lockdown reported that they did not feel that the national lockdown has had a detrimental effect on their children’s mental or physical health.

Binary logistic regression models were run looking at the predictive role of IDACI, ethnic background, gender, age, type of need or disability and type of educational setting attended by the child on parental perceptions of detrimental effects of the national lockdown on children’s mental and physical health.

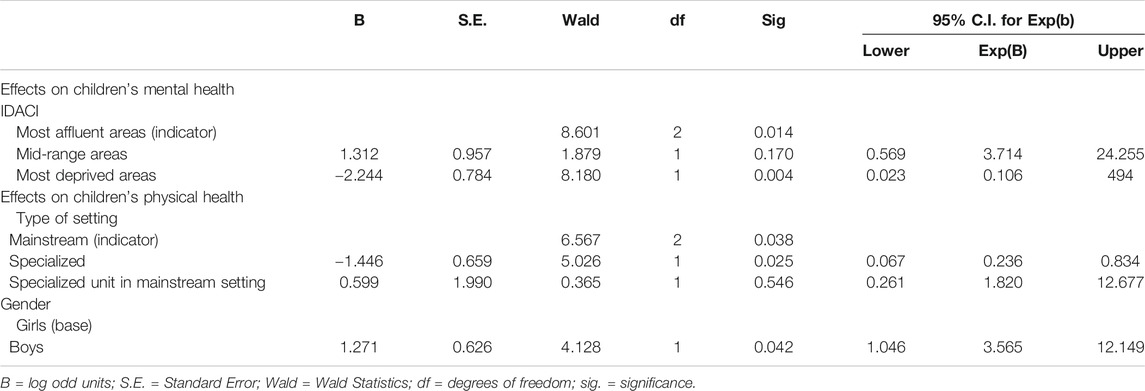

Regarding effects on mental health, a binary logistic model with all the variables of interest explained 29% (Cox & Snell R square) to 39% (Nagelkerke R square) of the variance on children’s mental health reports and has good fit [χ2 (8) = 9.33, p = 0.315]. Table 3 presents the likelihood ratios and parameter estimates for the independent variables tested, where effects were found. Significant effects on children’s mental health were found for IDACI only (using most affluent local authorities as the indicator), with parents from the most deprived neighbourhoods significantly more likely to say that school closures and lockdown affected their children’s mental health. Regarding physical health, effects were found for type of educational setting (with mainstream as indicator) and gender (with girls as indicator); parents of children attending specialized settings were more likely to say that lockdown affected their children’s physical health; parents of boys were more likely to say that school closures did not affect their children’s physical health. Parameter estimates for the variables tested can be found on table 3, where effects were found. In this case the model explains 19% (Cox & Snell) to 25% (Nagelkerke) of the variance in perceptions of physical health and has good fit [χ2 (8) = 87.39, p = 0.506].

TABLE 3. Parameter estimates for the effects of IDACI and type of setting on detrimental effect of school closures on mental and physical health, respectively.

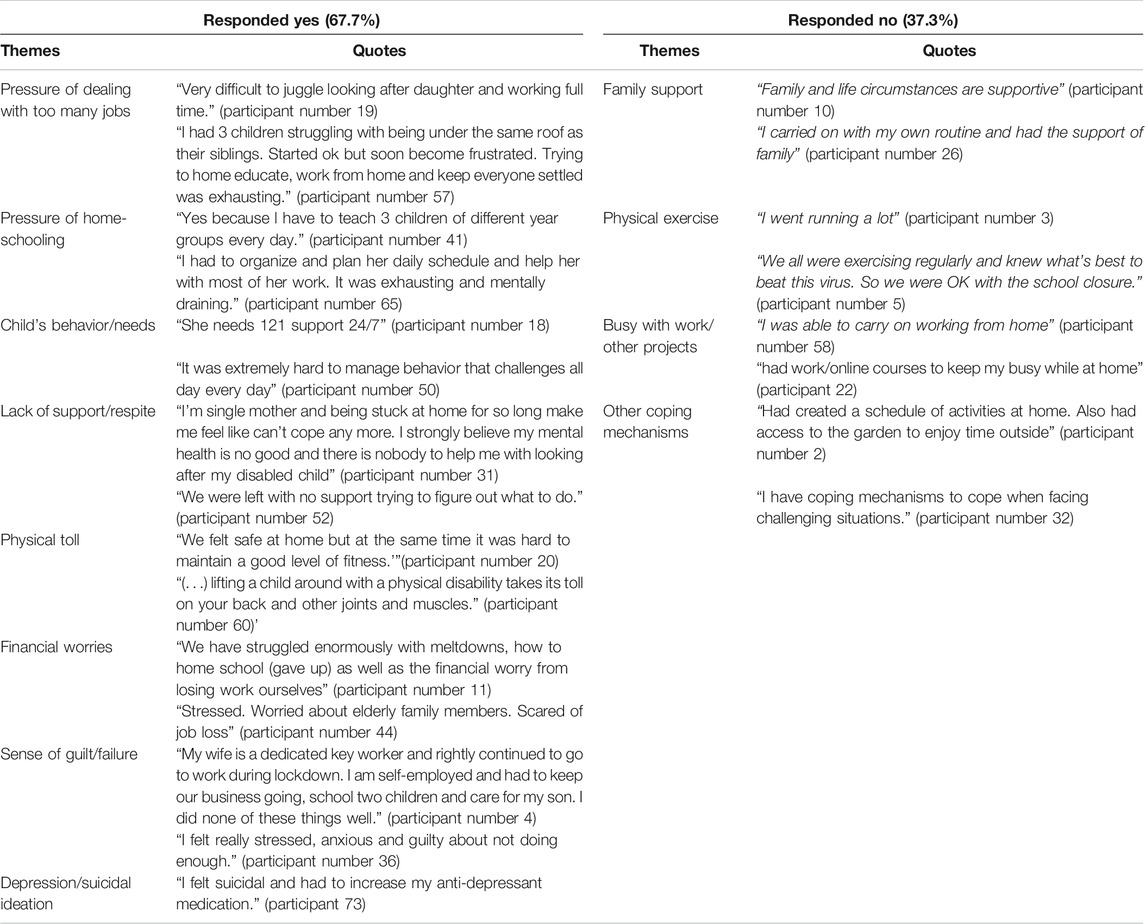

When asked whether school closures during the 2020 national lockdown have had a detrimental impact on their own physical and/or mental health, 52 parents (67.7%) responded that this was the case, and 31 (37.3%) reported that they did not have a detrimental effect. When asked to justify their answers, and among those that felt a detrimental impact on their mental health, the following themes emerged: pressure of dealing with too many jobs, pressure of home-schooling, child’s behavior/needs, lack of support/respite, physical toll, financial worries, sense of guilt/failure and depression/suicidal ideation. Among those that said it did not impact negatively their mental health, the following themes were identified: family support, physical exercise, busy with work/other projects and other coping mechanisms. Table 4 summarizes the different themes with respective quotes from the participants.

TABLE 4. Themes and quotes resulting from the analysis of responses to the items “Do you think that school closures had a detrimental effect on YOUR physical and/or mental health?” and “please tell us why”.

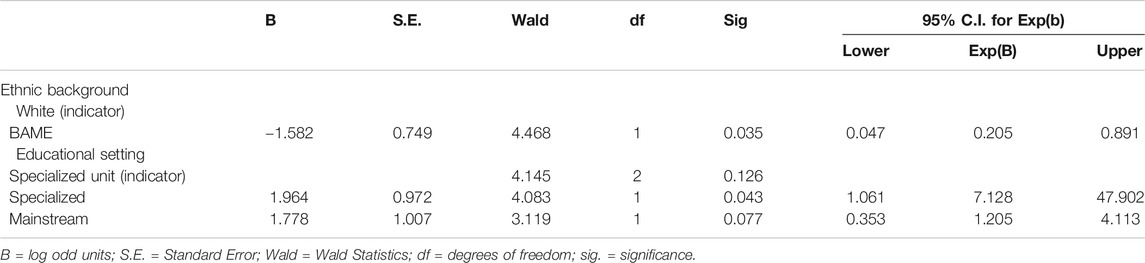

A Binary logistic regression model was run to test the effect of all demographic variables on the likelihood of parents reporting that school closures and lockdown have had a detrimental effect on their own mental and/or physical health. The model has good fit [χ2 (8) = 5.29, p = 0.725] and explains between 17% (Cox & Snell) and 24% (Nagelkerke) of the variance of parental mental and physical health. Effects, illustrated on Table 5, were found for ethnicity (with “white” as indicator) and type of educational setting (with “special “unit”as indicator); Parents of children from a BAME background were significantly more likely to say that they did experienced the detrimental effects of school closures on their health, as well as parents of children attending specialized units in mainstream settings.

TABLE 5. Parameter estimates for the effect of ethnic background on detrimental effect of school closures on parental mental health.

Parents were asked whether their children had returned to school, following the reopening of schools in September 2020. Seventy-five parents (90.4%) reported that their children were attending school again, with only 8 parents (9.6%) saying their children were not attending school.

We asked parents how pleased they were with the social distancing measures put in place by their children’s school to ensure Covid-19 safety; twenty-eight parents (33.7%) reported they were “very pleased”, 40 (48.2%) said they were “pleased”, and 7 parents (8.4%) said they were “not pleased” with measures put in place by schools.

When asked to justify their answer, and among the parents who were “not pleased”, responses were classified into no mask-wearing and lack of guidance/rules:

They followed the government guidelines, but they were not strict in their application. Gave parents the “choice” to abide by social distancing and facemask use and with this choice 99% of parents did not abide by the measures–participant number 26.

Among those that were very pleased, the most common theme was good communication with parents:

Clear communication–participant number 2;

Full risk assessment and good communication–participant number 50.

Other common themes were bubbles working well and good guidance:

hand sanitizer used throughout the day ad bubble system works and is keeping my child safe’–participant number 22; Good guidelines that my daughter also understands–participant number 28.

For parents who were “pleased”, all responses denoted that schools were doing their best, although this was not always the ideal:

They have done as much as they are able to within government guidelines, which have not taken into account the needs of special schools–participant 56.

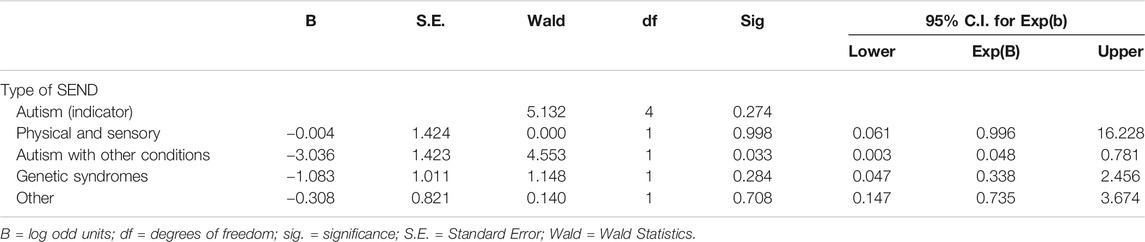

A binary logistic regression model was run to test the role of the demographic variables under interest on between being “pleased” or “very pleased” with the social distancing measures put in place by schools in relation to type of setting (Table 6). The Category “not pleased” did not have enough cases to be included in the analysis. Effects were observed for type of SEND: parents of children with autism alongside other conditions are more likely to lower their ratings from “very pleased” to “pleased”, than parents of children with the other types of SEND. The model explains 22% (Cox & Snell) to 29% (Negelkerke) of the variance in parental opinion regarding social measures implemented in schools and has good fit [χ2 (8) = 11.702, p = 0.165].

TABLE 6. Parameter estimates for the effect of type of setting on the likelihood of parents lowering their rating from “very pleased” to “pleased” in relation to social distancing measures implemented by their child’s school.

When asked whether returning to school has had a positive impact on their children’s mental health, 61 parents (73.5%) reported that this has had a positive effect, and 14 parents (16.9%) said that this was not the case.

When asked to justify their answers, among those of replied with “yes”, the most common theme was the return to socialization, followed by improved development/behavior and lastly returning to an established routine:

Although he said he didn’t miss any of his friends once he went back we could see his excitement at being able to talk to them again. He liked the return to routine. He stopped clinging to us as much or needing us in his eyeline. And he seemed happier to be away from us–participant number 81; He's back to the happy little boy he was. During lockdown he was so sad and unhappy. He has routine and equipment to help him through. He's learning and developing skills. He's having more contact with health professionals and someone with him who all the time to help him and he is eating again!–participant number 60.

Lastly, parents were asked how they felt about their children returning to school. Three themes were identified: happiness, mixed emotions and fear of the virus:

It has hugely reduced my anxiety and guilt about her well-being and development. I've increased her attendance by a half day as she is thriving at preschool and this has made me feel much less under pressure to create and perform and seeing their activities gives me ideas of activities I can do and emulate at home–participant number 62; Good and bad. Find it difficult to homeschool but worried about Covid as it's high for Asian people and families–participant number 74; I'm terrified that he might bring the virus home but I'm so glad he's back for him and his education–participant number 77.

The purpose of this study was to establish the impact of the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic on the physical and mental health of children and young people with SEND and of their parents in England, from the parents’ point of view, focusing on school closures (in March 2020) and on returning to school (from September to December 2020). The study looked at the role of socio-economic level of the postcode, children’s ethnic background, type of educational setting attended, children’s gender, age and type of need on the experience of school closures and of returning to school, as reported by parents.

Regarding parental perceptions of the impact of school closures on children’s mental health, the majority of parents reported that school closures had a detrimental effect on their children’s mental health. This is unsurprizing, and the psychological vulnerability of children and adolescents during the pandemic has been well documented, including for children with SEND (Warner-Richter and Lloyd, 2020). However, it is important to interpret this finding with caution, as it can reflect parental anxiety, more than actual children symptomatology, given that parents were the respondents to the survey. Asbury and colleagues (2020), who conducted the only large study to date in England looking specifically at the mental health of children with SEND and their families during the pandemic, found that although these families have clearly suffered the psychological impacts of the pandemic, stress and anxiety were observed more often in parents than in children. Consistent with this interpretation, some parents in the present study identified their own stress as one of the reasons potentially affecting their children’s mental health, in their qualitative responses. Moreover, the majority of parents reported that school closures had a detrimental impact on their own physical and mental health, and this more significant in ethnically diverse families (from a BAME background). Noteworthy is the effect of socioeconomic level found in the present study: parents living in the most deprived postcodes were significantly more likely to say that their children’s mental health was affected by school closures. This result highlights the widely recognized role of socioeconomic factors (often intersected with ethnicity) as vectors of psychological vulnerability in face of adversity (e.g. Morrissey and Vinopal, 2018; Taylor et al., 2020), but also underlines the importance of cumulative risk in children and families with SEND who are also from deprived communities. In other words, children with SEND from poorer backgrounds are much more likely to be affected, psychologically, by national lockdowns. Similar studies in the US also found that ethnically diverse families in Oregon and California, a majority of which receiving financial assistance from the government, reported that one of their main concerns about staying at home with their children during the pandemic was the loss of many support services that would, in normal circumstances, help to alleviate their financial pressures and also support their children’s development (Neece et al., 2020). Many of the parents in the present study also reported financial concerns as an added pressure brought about by the pandemic and the need to home-school. Schools often make up a substantial part of the net of supports received by these families; consequently, prolonged closure is likely to considerably affect these children’s development and wellbeing. Parents highlighted important areas of concern for children’s mental health and wellbeing during school closures, namely lack of socialization, the challenges of distance learning, generalized anxiety and emotional issues and also fear of the virus. This aligns with recent international research demonstrating that home learning can be significantly challenging for parents, teachers and children, particularly to those with SEND, with parents referring to lack of learning discipline at home, lack of technology skills and higher internet bills in lower income countries (Bahasoan et al., 2020; Putri et al., 2020). In addition to the practical challenges of home learning, evidence has arisen that the psychological impact of home learning on children’s wellbeing is substantial; in a study with 250 children from Spain, for example, the children reported feelings of boredom and loneliness, particularly for being removed from their peer socialization context and deprived of outdoor play (Idoiaga Mondragon et al., 2020). These are areas that deserve particular attention as we start redirecting the focus of our attention (in research and in professional practice) to the future and examine the longitudinal effects of the pandemic on these children.

Approximately half of the parents reported that school closures had a detrimental effect on their children’s physical health, particularly those whose children are girls and those whose children attend specialized settings. Schools are important spaces for play and exercise; children attending specialized settings often present more severe functioning profiles, as attested by the percentage of statutory provision in those settings, compared to mainstream ones. Many of the supports and therapies available in these settings could not be transferred to the home environment (Crawley et al., 2020), and therefore it is likely that developmental and physical consequences of this are present. This has been shown in a study conducted in the United States of America demonstrating that during lockdowns, children spent significantly more time in sedentary activities, leading to increased risk of obesity and cardiovascular disease (Dunton et al., 2020).

Between September and December 2020, the vast majority of parents reported that their children had returned to school and are mainly pleased or very pleased with the social distancing measures put in place in schools to ensure Covid-safety. However, parents of children that have an autism diagnosis alongside other conditions were more likely to lower their rating from “very pleased” to “pleased”. Most of the co-morbidities in this group included medical conditions, such as epilepsy or genetic problems, thus potentially making-up a more vulnerable group of children, which might, in turn, influence parental judgment.

Interestingly, the vast majority of parents reported that returning to school has had a positive impact on their children’s mental and physical health, including for those that did not consider that schools closures had a particularly detrimental effect. The most frequent reason given by parents for this was the return to socialization with peers and teachers, but also the return to established routines. This suggests that although families might have had the coping mechanisms and resources to deal with school closures effectively, the majority agree to the schools’ benefit for healthy child development and learning.

Noteworthy, some parents in this study reported that their children were happier and calmer at home, and again reported that returning to school has not had a positive impact on their children’s health. Although this represents a minority, it is a minority than cannot be ignored. The finding illustrates the potential “silver lining” of the pandemic and school closures for some children mentioned previously (Chawla et al., 2020), but it also uncovers areas for future investigation: it seems clear that our schools are not serving all children in the best possible way. A concerted multi-disciplinary effort is necessary to understand what role (or roles) schools can play in the lives of these children and consequently, how they can support these families more effectively.

The results of this study demonstrate that although the health impact of school closures on children with disabilities and their families was significant, returning to school was key to overcoming the detrimental effects of lockdown, as key contexts for socialization and learning. However, the study also shows that this is dependent on a number of variables of social-demographic nature. Planning for a future school post-covid-19 for children and young people with SEND and their families, in policy and practice, should include a tiered approach, looking at vulnerability and cumulative risk, and addressing needs of particular groups or even of particular individuals and their families. Moreover, we have learned from this pandemic that more governmental supports need to be immediately available for the poorer and most vulnerable in situations of national emergency.

This study has some limitations. First, the sample used is purposive and relatively small, therefore, generalizations about parental perspectives in England should be made with caution. However, the sample represents well a range of socioeconomic backgrounds in England, as defined by the IDACI (McLennan et al., 2019) and also the national distribution of the most frequent types of special educational needs and disabilities, according to the UK Government. Similarly, the small sample size implied that some variables had to be recoded to include larger number of individuals; for example, the category “BAME” can be considered reductionist and hide effects of particular ethnic backgrounds, which should be the focus of future research on the effects of the pandemic. Second, the study is based on parental reports of children’s mental and physical health, which is likely to reflect their own concerns rather than objective children’s outcomes. However, parental voice is crucial as a first step to understanding the child’s experience, particularly in children with SEND, for whom often the parent acts as direct advocate. Nevertheless, future research should look into apprehend these children’s voices and objectively assess their development in the “new normal”.

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee at the University of Roehampton.

SC-K conceived and designed the study, collected data, analysed data and wrote the final paper. AM contributed to the design of the study, data collection and writing up.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank the parents who have taken the time to respond to this survey.

Andrew, A., Cattan, S., Costa Dias, M., Farquharson, C., Kraftman, L., Krutikova, S., et al. (2020). Inequalities in Children’s Experiences of Home Learning during the COVID‐19 Lockdown in England. Fiscal Stud. 41 (3), 653–683. doi:10.1111/1475-5890.12240

Asbury, K., Fox, L., Deniz, E., Code, A., and Toseeb, U. (2020). How Is COVID-19 Affecting the Mental Health of Children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities and Their Families?. J Autism Dev Disord. 51, 1772-1780. doi:10.1007/s10803-020-04577-2

Bahasoan, A. N., Wulan Ayuandiani, W., Muhammad Mukhram, M., and Aswar Rahmat, A. (2020). Effectiveness of Online Learning in Pandemic COVID-19. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Manage. 1 (2), 100–106. doi:10.46729/ijstm.v1i2.30

Castro, S., and Palikara, O. (2016). Mind the Gap: the New Special Educational Needs and Disability Legislation in England. Front. Educ. 1. 4. doi:10.3389/feduc.2016.00004

Castro-Kemp, S., Palikara, O., and Grande, C. (2019). Status Quo and Inequalities of the Statutory Provision for Young Children in England, 40 Years on from Warnock. Front. Educ. 4, 76. doi:10.3389/feduc.2019.00076

Chawla, N., Sharma, P., and Sagar, R. (2020). Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on Children and Adolescents: Is There a Silver Lining?. Indian J. Pediatr., 88 (1), 91. doi:10.1007/s12098-020-03472-z

Chen, S.-Q., Chen, S.-D., Li, X.-K., and Ren, J. (2020). Mental Health of Parents of Special Needs Children in China during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 (24), 9519. doi:10.3390/ijerph17249519

Crawley, E., Loades, M., Feder, G., Logan, S., Redwood, S., and Macleod, J. (2020). Wider Collateral Damage to Children in the UK Because of the Social Distancing Measures Designed to Reduce the Impact of COVID-19 in Adults. BMJ Paediatrics Open 4 (1). doi:10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000701

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational Research: Planning, Conducting and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. 4th Edn. Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Dhiman, S., Sahu, P. K., Reed, W. R., Ganesh, G. S., Goyal, R. K., and Jain, S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 Outbreak on Mental Health and Perceived Strain Among Caregivers Tending Children with Special Needs. Res. Develop. Disabilities 107, 103790. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103790

Dunton, G. F., Do, B., and Wang, S. D. (2020). Early Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in Children Living in the US. BMC Public Health 20 (1), 1–13. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09429-3

Field, A. (2013). Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Guest, G., MacQueen, M., and Namey, E. E. (2014). Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Idoiaga Mondragon, N., Berasategi Sancho, N., Dosil Santamaria, M., and Eiguren Munitis, A. (2020). Struggling to Breathe: a Qualitative Study of Children’s Wellbeing during Lockdown in Spain. Psychol. Health 36 (2), 179–194. doi:10.1080/08870446.2020.1804570

Ladhani, S. N., Amin-Chowdhury, Z., Davies, H. G., Aiano, F., Hayden, I., Lacy, J., et al. (2020). COVID-19 in Children: Analysis of the First Pandemic Peak in England. Arch. Dis. Child. 105 (12), 1180–1185. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2020-320042

McLennan, D., Noble, S., Noble, M., Plunkett, E., Wright, G., and Gutacker, N. (2019). The English Indices of Deprivation. Ministry of Housing, Communites & Local Government, Technical report.

Morrissey, T. W., and Vinopal, K. M. (2018). Neighborhood Poverty and Children’s Academic Skills and Behavior in Early Elementary School. J. Marriage Fam. 80 (1), 182–197. doi:10.1111/jomf.12430

Neece, C., McIntyre, L. L., and Fenning, R. (2020). Examining the Impact of COVID-19 in Ethnically Diverse Families with Young Children with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 64 (10), 739–749. doi:10.1111/jir.12769

Palikara, O., Castro, S., Gaona, C., and Eirinaki, V. (2018). Capturing the Voices of Children in the Education Health and Care Plans: Are We There yet?. Front. Educ. 3, 24.

Putri, R. S., Purwanto, A., Pramono, R., Asbari, M., Wijayanti, L. M., and Hyun, C. C. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Online Home Learning: An Explorative Study of Primary Schools in Indonesia. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 29 (5), 4809–4818.

Singh, S., Roy, D., Sinha, K., Parveen, S., Sharma, G., and Joshi, G. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 and Lockdown on Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: A Narrative Review with Recommendations. Psychiatry Res. 293, 113429. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113429

Taylor, R. L., Cooper, S. R., Jackson, J. J., and Barch, D. M. (2020). Assessment of Neighborhood Poverty, Cognitive Function, and Prefrontal and Hippocampal Volumes in Children. JAMA Netw. open 3 (11)–e2023774. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.23774

UK Government (2020). Special Educational Needs In England: January 2020. Special Educational Needs and Disabilities and High Needs. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/special-educational-needs-in-england-january-2020.

Viner, R. M., Russell, S. J., Croker, H., Packer, J., Ward, J., Stansfield, C., et al. (2020). School Closure and Management Practices during Coronavirus Outbreaks Including COVID-19: a Rapid Systematic Review. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 4, 397–404. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30095-X

Warner-Richter, M., and Lloyd, C. M. (2020). Considerations for Building Post-COVID Early Care and Education Systems that Serve Children with Disabilities. Bethesda, MD. Child Trends.

World Health Organization (2020a). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). World Health Organization, Situation Report—51.

World Health organization (2020b). WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19. Available at: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020.

Keywords: COVID-19, England, school closures, pandemic, SEND

Citation: Castro-Kemp S and Mahmud A (2021) School Closures and Returning to School: Views of Parents of Children With Disabilities in England During the Covid-19 Pandemic. Front. Educ. 6:666574. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.666574

Received: 10 February 2021; Accepted: 16 April 2021;

Published: 13 May 2021.

Edited by:

Maxwell Gregor Ross, Arctic University of Norway, NorwayReviewed by:

Lakkala Suvi, University of Lapland, FinlandCopyright © 2021 Castro-Kemp and Mahmud. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Susana Castro-Kemp, c3VzYW5hLmNhc3Ryby1rZW1wQHJvZWhhbXB0b24uYWMudWs=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.