- Department of Preschool Education, Faculty of Education, University of Crete, Crete, Greece

Data that shows that young children can learn and acquire Computational Thinking (CT) skills has led governments and policymakers internationally to integrate CT into the curriculum, starting in the earliest grades. Researchers support the idea that this introduction must not solely focus on a problem-solving process skill (CT) but instead provide children with new ways to express themselves, supporting their cognitive, language, and socio-emotional development (Computational Fluency-CF). Coupled with the media and government’s rhetoric and an increasing number of apps offering various programming lessons, puzzles, and challenges, educators have been responsible for introducing young children to CT and CF using touchscreen technology. This paper presents a literature review (N = 21) of empirical studies on applying four coding apps to support young children’s learning of CT and CF. The main conclusion is that all apps positively affect the development of children’s CT skills. None of the apps can ultimately support the development of CF, although ScratchJr, with a “sandbox” approach, can better help students express themselves.

Introduction

Research shows that quality and intensive early childhood education positively affects children’s learning later in life (Bers, 2019; Yu and Roque, 2018). Consequently, in the past few years, around the globe, countries are introducing computing curricula into their national curriculums to equip pupils with much-needed skills. The development of Computational Thinking skills for young children attract increasing attention (Strawhacker et al., 2018) as a new literacy for the twenty-first century (Bers, 2020). It is considered an effective way to build thinkers and innovators, engaging children in skills that translate across the disciplines and undoubtedly need them at some point in their lives (Kazakoff, 2014). As Bers (2020) highlights, coding can be studied as a domain-general problem-solving mechanism and a process that allows users to create shareable products.

Nevertheless, in a world where Moore’s law is picking up its pace, skills in coding would no longer make sense (Byrd, 2020) as computational thinking and coding are not only problem-solving process skills. Instead, it is skill sets that provide children with new ways to express themselves, supporting their cognitive, language, and socio-emotional development (Sullivan et al., 2017; Strawhacker et al., 2018; Sheehan et al., 2019). What is needed now more than ever are not just code wizards, but students who can bring those skills to solve problems, and the only way to answer that is to understand how to identify specific problems, how to communicate effectively, how to problem solve, and think creatively.

The issue presently facing educational technology is not teaching CT and coding in early childhood but selecting developmentally appropriate tools and practices (Sullivan et al., 2017; Hamilton et al., 2020). Young children, with their unique developmental needs, need coding environments designed explicitly for them. These must be austere environments that still support multiple combinations, have syntax and grammar, and offer multiple ways to solve a problem (Bers, 2020). They need to provide opportunities for creating a computational artifact that can be shared with others and support a growing range of computational literacy skills, from beginner to expert (Bers, 2020). Despite the growing number of apps aiming to get children interested in coding, only a few studies have evaluated these apps’ effectiveness (Pila et al., 2019) in developing children CT skills and fluency.

The present study focuses on how young children (aged seven and under) can engage in Computational Thinking and Computational Fluency (CF) using new programming interfaces such as mobile applications (apps). This paper presents a literature review (N = 21) of empirical studies on applying coding apps to support young children’s CT and CF learning. The paper is organized as follows: the introduction part is followed by the theoretical framework of CT and CF. Method and research questions follow the theoretical framework. Findings on the learning effects and researchers’ perspectives on the apps are reported in subsequent chapters.

Computational Thinking and Computational Fluency

Nowadays, computation is a fundamental part of human existence; children grow up surrounded by technology, CT and coding are considered abilities essential to every child growing up in the 21st century (Ching et al., 2018). Teaching CT to young learners’ is not a new idea; it dates to 1980 (Papert, 1980). The Logo turtle robot and Slot Machines are two of the earliest best-known attempts to support children to explore computational thinking (Clarke-Midura et al., 2019). Nevertheless, it gained popularity in the context of education when Jeannette Wing wrote that “to reading, writing, and arithmetic, we should add computational thinking to every child’s analytical ability” (Wing, 2006, p.33). This popularity has led governments, researchers, policymakers, and stakeholders worldwide to propose computing in compulsory education (Rose, 2019; Rehmat et al., 2020; Tikva and Tambouris, 2020). This topic has been the subject of attention even across international organizations such as the OECD and UNESCO, recognizing CT and coding as essential competencies required to meet future requirements for a successful life (Falloon, 2016). In this context, new initiatives to introduce computing literacy to citizens have been undertaken worldwide from companies, universities, and non-profits such as the Hour of Code, EU Code Week, CS Education Week, and CS for All. Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, and other leading technology figures promote learning to code as a basis for overall development, gave the same importance as reading, writing, and arithmetic (Walsh and Campbell, 2018).

CT can be considered a general problem-solving framework involving knowledge, skills, or solving problems approaches and coding to support these concepts and tasks (Brennan and Resnick, 2012; Ching et al., 2018; Bers, 2019; Rose, 2019). These include sequences, conditionals, operators, and variables and an understanding of triggers, events, and parallelism (Falloon, 2016; Nouri et al., 2020). CT and programming’s relationship can be described as follows: “programming supports CT’s development while CT provides to programming a new upgraded role” (Tikva and Tambouris, 2020, p.7).

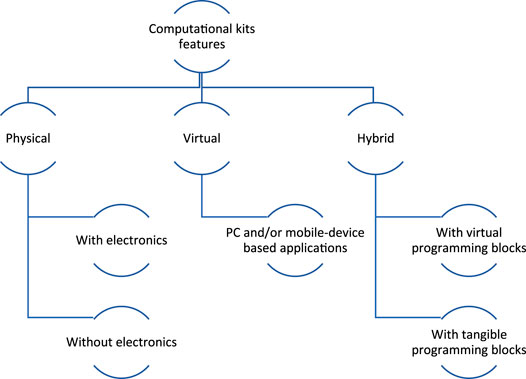

It is well established that young children spend a substantial amount of time with touchscreens devices (Dore and Dynia, 2020; Galway et al., 2020; Pila et al., 2019) and that they can handle these devices as young as 18 months old, often before reading (Rose, 2019). Touchscreen technology has reduced the children’s necessity of performing tasks with a computer, which was a challenging task for young children with limited fine motor skills. Furthermore, object-oriented, “drag and drop” apps have removed much of the code development complexity inherent in traditional text programming languages engaging teachers and students in purposeful activities and conversations and helping students better understand CT concepts. Findings prove that coding apps may be an ideal tool to introduce young age children to coding activities even before entering formal schooling (Sullivan et al., 2017; Sheehan et al., 2019). It is essential to mention that physical coding toys/approaches are more engaging for young children and have huge educational potentials (see Figure 1) (Hamilton et al., 2020).

FIGURE 1. A categorization of computational kits and toys appropriate for young age children based on their physical features (Adapted by Yu and Roque, 2018).

Although there are many programming tools in apps (Ehsan, Beebe and Cardella, 2017), most of them are not designed for young age students. It is not enough to copy models of computer science education developed for elementary, middle, and or high school students, which are not developmentally appropriate for young children (Bers, 2020). Some coding apps rely heavily on words, while others mask programming actions, thus obscuring critical aspects of creating coding (Kazakoff, 2014). Text-based programming languages are not considered developmentally appropriate for children aged 5–7, an age group that includes pre-readers (0–5) and emergent readers (6–7) (Sullivan and Bers, 2019; Pelánek and Effenberger, 2020). On the contrary, there is evidence to suggest that young children can learn coding at a young age when given developmentally appropriate tools, which support open-ended play and reduce the cognitive effort in a fun and enjoyable way (Murcia et al., 2020). A developmentally appropriate educational approach must be consistent with the children’s needs and embrace their maturational stages by combining play, discovery, socialization, and creativity (Bers, 2019). Since 2009 Resnick and his colleagues proposed that programming environments must be characterized by “low floors, high ceilings, and wide walls” (Resnick et al., 2009).

Many researchers also claim that coding in early childhood should not consider a set of technical skills but a new type of literacy and self-expression, which students need to function effectively in the 21st century; a new way for people to organize, share their ideas and express themselves (Resnick, 2017). Seymour Papert’s computational thinking involved problem-solving and the notion of expression (Bers, 2020). Byrd. (2020) mentions that what is needed now more than ever is the ability to use technology to solve problems, and the only way to answer that is to understand how to model problems, think critically, communicate effectively, and solve problems creatively.

Individuals become technologically fluent when they can use technology to express themselves creatively, in a fluent way, effortlessly, and smoothly, as one does with language (Bers, 2020). For the reasons mentioned, researchers such as Resnick. (2017) and Bers. (2020) state that it is better to focus on computational fluency than computational thinking. For Resnick, computational fluency involves understanding computational concepts and problem-solving strategies and creating and expressing oneself with digital technologies. Mitchel Resnick states (Kamenetz, 2015), “If you have kids put blocks together to solve the puzzle, which can help learn basic computing concepts. Nevertheless, we think it is missing an essential part of what is exciting about coding. If you present just logic puzzles, it is like teaching them writing by only teaching grammar and punctuation. In terms of textual literacy, it would be like only giving children crossword puzzles to solve and expecting them to become fluent writers.” Thus, if computational thinking is to be defined as a process of problem-solving, expression, and creation, we need to provide tools that enable creating an external artifact (Bers, 2020).

In many introductory coding activities, students are asked to code step by step the movements to navigate a virtual character through a maze toward a goal. This approach is designed to help students learn basic science concepts, but it does not allow them to express themselves creatively, developing imagination, curiosity, and a long-term engagement with coding (Resnick and Siegel, 2015). Well-designed coding apps must provide an interface that enables users to think creatively, promote problem-solving, and often work collaboratively to create or improve their projects (Hutchison et al., 2015). Resnick (2003) states that computer science is well-suited for early childhood education as it provides a positive and effective learning environment where young children can “play to learn while learning to play” (Resnick, 2003, p.1), promoting a coding playground and not a coding playpen (Bers et al., 2019). A playpen is an environment that provides children with limited opportunities to explore (Resnick, 2017). The coding playground promotes open-ended exploration opportunities, creating personally meaningful projects, imagination, problem-solving, conflict resolution, and collaboration. The coding playground engages children in six behaviors that we can also find in the regular playground: content creation, creativity, choices of conduct, communication, collaboration, and community building (Bers, 2018). Similarly, Román-González et al. (2019) extend the concept of CT to include various soft skills such as effective communication, decision making, self-confidence, creativity, and teamwork.

All coding apps available in the two biggest app stores claim that they have value as educational tools, but their value is undetermined. To date, there has been little empirical research on the effectiveness of these apps in introducing computational thinking and computational fluency in young children (Sheehan et al., 2019). Many of these apps have never been evaluated in young children, so their claims cannot be confirmed (Giannakoulas and Xinogalos, 2018; Terzopoulos et al., 2019). More research is needed to determine whether the various coding apps facilitate CT and CF in young children (Pila et al., 2019; Sheehan et al., 2019; Hamilton et al., 2020). This study fills the knowledge gap in the existing literature by providing vital evidence to inform decisions about the available coding apps’ appropriateness on developing CT and CF for young children.

Methods

Research Goal and Questions

This review aims to synthesize research on the impacts of using coding apps on Computational Thinking and Computational Fluency of young children. The Goal, Question, Metrics (GQM) approach was adopted as it stands for a systematic approach for defining and evaluating a set of stated operational goals using measurements. Applying the GQM involves 1) developing a set of research goals, 2) generating questions that define those goals, 3) specifying the types of data to be collected, 4) developing methods for data collection, 5) collecting, validating and analyzing the data to assess the goals and make recommendations for improvement (Basili, 1992, p.4). According to the Goal-Question-Metric approach (Basili, 1992), the present study investigates coding apps’ educational value in developing young children’s Computational Thinking and Computational Fluency. Two research questions were formulated to achieve this goal based on the author’s experience and relevant literature (Laporte and Zaman, 2018; Fessakis et al., 2019; Jin and Zha, 2019; Terzopoulos et al., 2019; Yu and Roque, 2019). More specifically, the following research question was identified:

— RQ1: How do coding apps affect the development of Computational Thinking of young age students?

— RQ2: How do coding apps affect the development of Computational Fluency of young age students?

Research Methodology

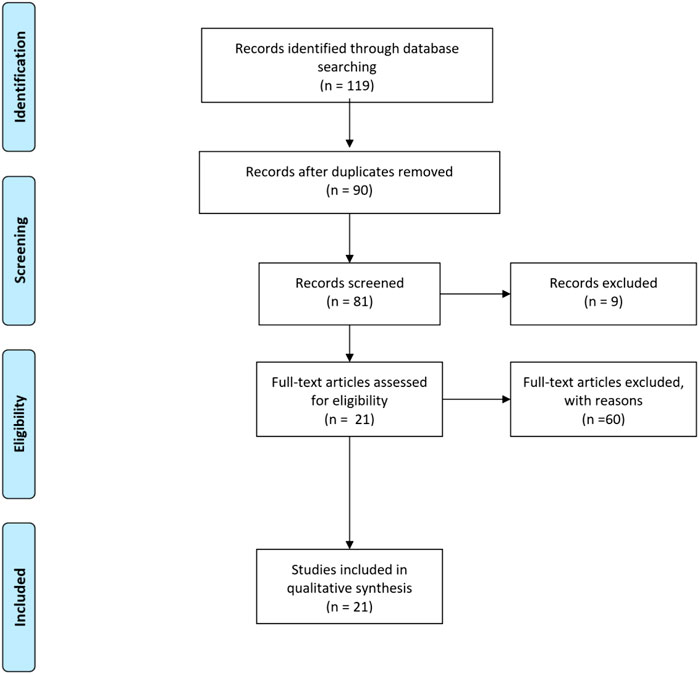

A protocol following method guidelines by Kitchenham. (2004) is reported in line with the PRISMA statement in three phases: planning, conducting, and reporting the review. These involve developing the review protocol, defining inclusion and exclusion criteria, searching for relevant literature, critical appraisal, data extraction, and data synthesis. The identification, assessment, and selection of articles for inclusion are shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. PRISMA flow diagram for this review’s search process (Moher et al., 2009).

Development of the Review Protocol

Based on the work of Wang and Tahir. (2020), the present study review protocol was developed to achieve the following goals: 1) to maximize the literature coverage; 2) to identify and include the related work classified as a study, and 3) to collect, organize, synthesize, and analyze data from widely divergent sources based on the defined research questions.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were considered to identify as much relevant literature as possible to provide a comprehensive presentation of the topic. The inclusion criteria used for the analyses were restricted as follows:

• The document is a journal article or book chapter and not a report, poster, letter, abstract or editorial.

• The document is published in a peer-reviewed journal or presented at international conferences, or published in international book series.

• The document is written in English.

The exclusion criteria were considered as follows:

• The article is not accessible online.

• The coding app(s) is(are) only mentioned as an example and is(are) not the paper’s focus.

• As the first tablet type device was launched in 2010, the search covered 2010 to December 2020. Studies outside this range were excluded.

Search Procedure

The search procedure was carried out in two steps. Initially, the scientific literature databases were searched for relevant studies published from 2010 to December 2020. Then the reference lists of included studies were checked for additional studies.

Based on the four research questions, the following search string was used: (teach OR teaching OR learn OR learning OR education OR educational) AND (apps OR application OR mobile OR touchscreen) AND (code OR coding OR program OR programming OR computational thinking) AND (preschool OR kindergarten OR first-grade OR young children).

The following research databases were searched in sequence: ACM Digital Library (Association for Computing Machinery), CiteSeerX, Digital Library - CSDL | IEEE Computer Society, Emerald Insight, ERIC - Education Resources Information Center, Ingenta Connect, JSTOR, Learning and Technology Library (LearnTechLib) (formerly EdITLib), LISTA (Library, Information Science and Technology), ProQuest, SAGE Journals, ScienceDirect, Scopus, Taylor and Francis and base (Bielefeld Academic Search Engine). These databases were chosen as they all provide extensive coverage of journals in the study research field. Additional searches were done in Google Scholar in English. As syntax and semantics of different databases differ, the search terms were slightly adjusted to accommodate different databases’ needs.

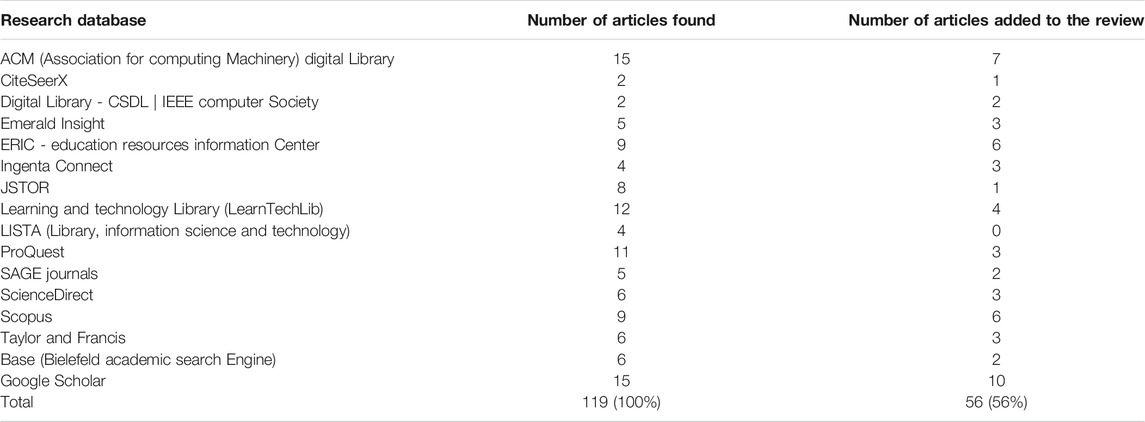

Table 1 summarizes the results of the search undertaken in sixteen different databases. Initially, titles and abstracts of identified articles were checked for relevance by the researcher. Studies that fulfilled both the inclusion and exclusion criteria were downloaded, and relevant information was stored in a database. In this stage, most rejected articles were articles not written in English.

Critical Appraisal

Three different criteria focused on relevance, rigor, and credibility were employed to ensure the studies’ quality. First, the search was performed in databases known for studying technology and education. Second, the studies had to undergo independent peer review. Third, the methodology of the selected studies was reviewed for publication bias. Studies with missing data on any of the critical information were excluded from further analysis. A drawback of the present study was that the researcher carried out this critical appraisal. Table 2 reports the findings from the critical appraisal of the papers. 21 of the 56 articles were accepted. Thirty-five studies were excluded as they lacked sufficient rigor. The remaining two studies were classified as presentations or posters.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted from the accepted articles during this stage by reading the full text. An Excel file was used to store the data extraction output. Each study was analyzed to derive these data, most of which are presented in the results section. These studies are described in Supplementary Appendix A–C.

Results

General Results

Studies Distribution by Database

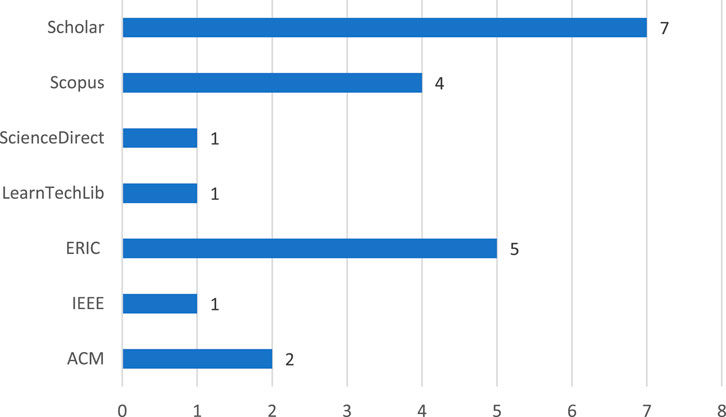

The author identified 21 related studies extracted from major online databases, as shown in Figure 3. Most articles were retrieved from Google Scholar, followed by ERIC and Scopus. All other databases contribute with only one or two papers.

Distribution by Sample Size

The sample size varied considerably from 12 participants up to more than 200. Two studies did not specify the number of participants included. Other studies did not merely use children as participants but dyads of students/teachers and students/parents.

Distribution by Subject Areas

Most of the studies (81%) used experimental study designs to understand whether the coding apps can help students develop their CT and coding skills. Three studies examined whether a coding app can help children learn mathematical concepts, while one study combined the use of ScratchJr to teach children physical science concepts via project creation.

Distribution by Artifacts

All studies that implemented ScratchJr asked the participants during or at the end of the study to produce projects in games, animation, or storytelling. The studies focused on the other three coding apps did not result in a final product, as the participants only had to play games due to the game nature of these apps.

Distribution by Coding Apps

The 21 accepted studies examined only four different apps. Sixteen studies mentioned the ScratchJr solely, and one study the Kodable app. Four papers described studies that combined two apps (Lightbot-ScratchJr, Lightbot-Kodable, Daisy the Dinosaur-ScratchJr, Daisy the Dinosaur-Kodable). In total, eighteen different studies mentioned the ScratchJr. Each of the remaining three apps was mentioned by two studies solely or in dyads with another app.

RQ1: How Do Coding Apps Affect the Development of Computational Thinking of Young Age Students?

To answer this research question, we used the definition for computational thinking provided by Rose and his colleagues. Based on a review of the existing definitions of computational thinking, they defined a working definition or guidelines about computational thinking using the following seven concepts: abstraction and generalization, algorithms and procedures, data collection, analysis and representation, decomposition, parallelism, debugging, testing, and analysis and control structures (Rose, Habgood, and Jay, 2017). Ehsan et al. (2017), in their study, provide a detailed description of these concepts.

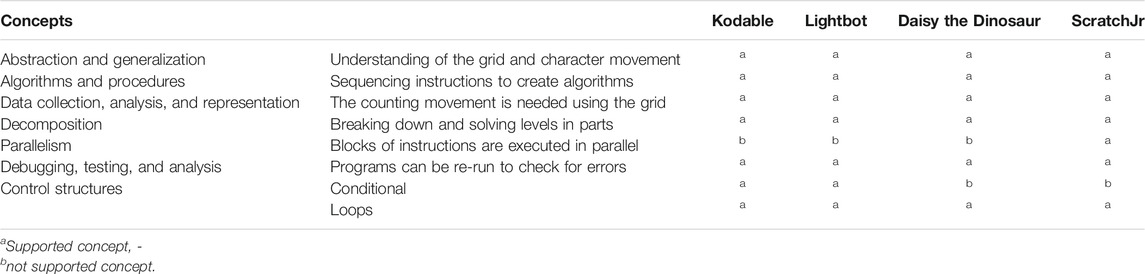

The present study findings (see Table 3) prove that the four apps positively affect the development of Computational Thinking of young age students. All apps can teach young children foundational coding skills while providing a fun and enjoyable platform for practicing these skills. These results follow Ehsan and her colleagues’ study results, which found that these four apps can help children develop these competencies (Ehsan et al., 2017).

TABLE 3. The computational thinking concepts supported in Kodable, Lightbot, Daisy the Dinosaur, and the ScratchJr.

Despite their differences in the programming interface, what is essential is that all studies reported that the four apps not only allowed children to learn necessary CT and coding skills such as sequence, repetition, and debugging but also encouraged children with a positive behavior for coding, which is necessary for their socio-emotional development (Sullivan et al., 2017; Strawhacker and Bers, 2019; Chou, 2020; Govind, Relkin and Bers, 2020). All apps helped the children learn algorithms and basic programming concepts while providing an enjoyable, interactive platform for both genders to practice these skills (Karadeniz, Samur, and Özden, 2014; Rose et al., 2017; Pila et al., 2019). Nevertheless, instead of learning CT and skills, studies targeted on the ScratchJr showed that the app could also be used by the younger students to get introduced to STEM learning or to explore numeracy concepts such as positive and negative integers, multiplication tables, or physical science concepts (Thuzar and Nay, 2015; Kalogiannakis, Ampartzaki, Papadakis and Skaraki, 2018; Sheehan et al., 2019; Herheim and Severina, 2020). Furthermore, Daisy the Dinosaur app offers two modes: a structured challenge mode and a free play mode. An app advantage is that it has an intuitive design, with precise functionality using cute and straightforward graphics with limited instructions. Also, only the Daisy the Dinosaur and the ScratchJr support events handling such as the “when touch.”

None of the apps evaluated in this study support variables, names a programmer gives to memory locations to hold one or more values. It should not be considered a problem as researchers claim that young children have problems understanding abstract representations such as variables. Relkin et al. (2021) highlight that developmental considerations such as variables must be considered when designing educational programs to teach CT to young children. Additionally, this study findings revealed that ScratchJr and Daisy the Dinosaur apps are missing a conditional option. This might be because research demonstrates that early elementary school children may have difficulty grasping “if-then” conditionals (Relkin et al., 2021). It would be a promising idea in an updated version of ScratchJr the developers to include this choice as a logical step from linear sequencing in kindergarten to an extension to loops and conditional in second grade. In this approach, children will understand that there are different actions within a sequence depending on a condition or patterns that repeat themselves.

Of course, there are operational differences between the coding approaches employed in various apps. For instance, in ScratchJr, an almost limitless number and variety of blocks can be added to the scene. These blocks are not executed unless linked to a trigger block or individually pressed to execute them. Whereas in Lightbot, the play button sequentially executes all the instructions included in the main program. Lightbot also limits how many instructions can be in the program depending on the current level (Rose et al., 2017). Daisy the Dinosaur, on the other hand, requires reading simple words such as “turn” and “shrink” in each programming block.

Regarding ScratchJr drawbacks, Falloon (2016) suggested that as coding activities are likely to be integrated into the entire curriculum in primary schools, “the minor addition of a sprite pencil would be helpful (p. 589).” ScratchJr supports only four different pages per project and faces delays when the user inserts many sprites on the screen. Thuzar and Nay (2015) highlighted that some students negatively mentioned the small number of messages sent between the characters. The students also complained about the limited number of scenes they could insert into their projects. In the same study, students also asked for variables and a faster environment as they experienced delays due to the increased number of sprites inserted in their projects.

The studies examined mentioned that the children had difficulty managing the loop statement in the Kodable and the Lightbox app (Karadeniz et al., 2014; Gomes, Falcão, and Tedesco, 2018). Gomes et al. (2018) also emphasized the app’s complexity in visual and textual descriptors for children aged 5–7 years. They also mentioned “the complex constructs in initial tutorials, help, and feedback” encountered in Lightbot (p. 80).

RQ2: How Do Coding Apps Affect the Development of Computational Fluency of Young Age Students?

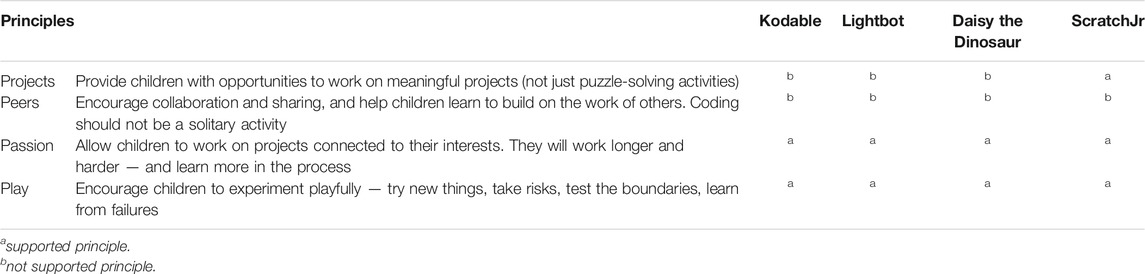

According to Bers (2020), coding is not only a cognitive activity that involves problem-solving and logical sequencing, but it is also an expressive medium that engages emotional and social domains. Thus, coding environments that are developmentally appropriate for young children must support children’s expression and developmentally appropriate experiences such as problem-solving, imagination, cognitive challenges, social development, emotional exploration, and making different choices (Bers, 2020). This is the first study in our knowledge that attempts to evaluate coding apps in computational fluency based on Resnick and Mitchel’s (2015) recommendations. For this purpose, we considered the following four principles for introducing coding to support gaining computational fluency: projects, peers, passion, and play. The study findings (see Table 4) prove that the four apps can partially support young children to gain computational fluency.

TABLE 4. The computational fluency principles supported in Kodable, Lightbot, Daisy the Dinosaur, and the ScratchJr.

Regarding the passion and play principle, in general, all studies mentioned that children, despite their demographic characteristics, enjoyed playing with apps and enthusiastically engaged in their lessons or tasks. Thus, we can consider that all apps effectively support these two pillars of Computational Fluency. As far as the peer’s principle, no one of the studies in this SLR provided explicit evidence that the children worked collaboratively and helped each other build their projects or finish a task. This sounds reasonable following Sullivan et al (2017) recommendations. Their study highlighted that only given an appropriately designed curriculum (in terms of structure, materials, and evaluation tools), apps such as the ScratchJr can promote positive behavior for social interaction.

Considering that the critical challenge is not only how to “teach creativity” to children but how to create a fertile environment in which their creativity will take root, grow, and flourish, we can consider that ScratchJr differs from the other coding approaches. ScratchJr, due to its open-ended approach, aspires to help children express themselves creatively and share their creations with others. In all apps except ScratchJr, players arrange symbols on the screen to command a sprite to walk, turn, jump, switch on a light, and so on. The maze and the list of symbols become more complicated as the game progresses. However, while this kind of software promotes computational thinking, it does not engage in the full range of experiences that a programming language does as it focuses on problem-solving but not expression. As Bers (2020) states, this approach facilitates exploration of computational concepts, (i.e. practicing skills, mastering discrete concepts, isolating skills), but this occurs in a limited way as it does not support creative projects (Clarke-Midura et al., 2019). It has been noted in various studies relative to ScratchJr, that the app provides a powerful tool for open-ended play related to both programming and literacy if used correctly. Kazakoff (2015), in her study, concluded that ScratchJr could be introduced as a teaching-learning intervention in the classroom as it provides opportunities for teachers to integrate digital literacy in authentic tasks easily. Papadakis et al. (2016) also recommended implementing ScratchJr as a teaching tool in early childhood as it helped children develop cognitive, language, emotional and social skills.

Similarly, Lowe and Brophy. (2019) noted that ScratchJr is a powerful accelerator for understanding computation than abstract storytelling alone. Falloon. (2016) also recognized that the ScratchJr design encourages children’s experimentation and open-ended exploration. Nevertheless, as most of the reported studies have been conducted in research settings and thus do not reflect usual students’ samples in real classroom settings, it remains under question whether the ScratchJr app, despite its open-ended approach, can genuinely support children to express themselves creatively via projects.

Discussion and Future Directions

Data that shows that young children can learn and acquire Computational Thinking skills has led governments and policymakers internationally to integrate CT into the curriculum, starting in the earliest grades. Researchers support the idea that this introduction must not solely focus on a problem-solving process skill (Computational Thinking) but instead provide children with new ways to express themselves, supporting their cognitive, language, and socio-emotional development (Computational Fluency). Coupled with the media and government’s rhetoric and an increasing number of apps offering various programming lessons, puzzles, and challenges, educators, and parents have been responsible for introducing young children to Computational Thinking and Computational Fluency using touchscreen technology. Further research is required to determine whether the available coding apps are developmentally appropriate, appealing, and meaningful for young children.

This review aimed to systematically evaluate the efficacy of coding apps to develop young children’s CT and CF. This study, similar to Clarke-Midura et al.'s (2019) study, makes no claims about whether one coding app is superior to another, as these apps all originate from high-quality methodological research on educational technology. However, the results presented in this study should serve as a benchmark and challenge for teachers, researchers, and software developers to be mindful of what demands and expectations we are placing on young children as they learn to code (Clarke-Midura et al, 2019). Indeed, the findings showed that the essential CT and coding skills mentioned in known CT frameworks could be delivered using the four different apps mentioned in this study. All apps have an interactive and appealing design offering an acceptable challenging level. This is considered especially important as studies exploring young children learning from educational multimedia argue that if children do not enjoy an environment or interface, they will not collaborate with it, eliminating any potential educational benefit (Pila et al, 2019).

Nevertheless, considering that programming environments must also promote imagination, cognitive challenges, social interactions, motor skills development, personal exploration (Bers, 2018), we must recognize that: (a) none of the apps truly supports CF and (b) there is a significant difference between the apps. Considering Resnick and Mitchel’s (2015) four principles of introducing CF, none of the apps genuinely encourage collaboration and sharing, helping children learn to build on the work of others (peers’ principle). In all studies, coding seems to be a solitary activity. All apps support the passion and play principles. The three apps mentioned in this review (Kodable, Daisy the Dinosaur, and the Lightbot) engage children in coding, math, and problem-solving skills via structured puzzle-like challenges. By navigating mazes using instructional commands, the children actively solve the problem to meet the challenge. While this puzzle-like approach is popular due to the ease of classroom implementation, it “reduces the potential of learning how to code to a problem, ignoring the expressiveness and communicative functions of programming” (Bers, 2019, p.503). This is an apparent distinction between the “bricolage-based approach” (Rose, 2016) or “sandbox approach” (Kamenetz, 2015) of ScratchJr and the more structured programming style used in apps as the Lightbot. Bers (2019) concerns that these puzzle-type coding approaches miss the opportunity to explore a “programming language’s richness as a symbol system with grammar and syntax that can be used to express thoughts and ideas” (p. 503).

Working on literacy practices and self-regulated learning skills is not a privilege reserved only for those working with the ScratchJr app. What is unique is that this review showed that children via the ScratchJr app could integrate CT concepts into their projects to make their stories more engaging, exciting, and emotional (Kazakoff, 2015). The “low-floors, high-ceilings, wide walls” approach of ScratchJr enable children to develop and broaden their general academic experiences, skills, and views (Portelance et al, 2016). In the process, children not only learn programming concepts and practices but develop valuable problem-solving skills. (Kazakoff, 2015; Strawhacker et al, 2018). Only one study mentioned teachers’ perceptions regarding using a coding app in the classroom (Strawhacker et al., 2018). The researchers found that regardless of their teaching style, most educators were positioned positively regarding the introduction of ScratchJr in their classroom. They advocated the ScratchJr open-ended design and the possible role of this environment in various educational contexts and settings. Of course, we must consider that the “coding as playground” approach may not work for all children. Some children may struggle with what to do or why to edit sprites or build animations. As Clarke-Midura et al. (2019) highlight, some children may not be able to afford to support coding independently, and apps like ScratchJr may require special attention, scaffolding, and systematic instruction in real educational settings. Thus, one could conclude that it could be more beneficial for children some structure or narrative to help them learn some concepts in the initial stages of coding. In the following stages, the more open environments can help children explore concepts more deeply based on their interests. Furthermore, future research is also needed on how, if at all, the role of play scenario affects children’s motivation to code (Clarke-Midura et al., 2019).

Interestingly, all apps mentioned in the studies are free or partially free and work on various operating systems and types of smart devices. Coding apps should be available for free and for various platforms as not all parents or schools can afford to buy an iPad or pay for app licenses (Terzopoulos et al., 2019). Additionally, they are stand-alone applications, and they do not require a continuous internet connection, which may be costly or even unavailable in some educational contexts. In terms of educational material, some apps come with a set of educational resources to support educator’s practices, such as classroom activities and assessment tools (Flannery et al, 2013; Kazakoff, 2015; João, Nuno, Fábio, and Ana, 2019).

Programming languages can become playgrounds in which children code. Four-to seven-year-old children are curious and eager to learn, but they get fatigued easily and have short attention spans. Given these developmental characteristics, designing programming languages for young children can be challenging (Bers, 2020, p.207). We need apps that can create an attractive and interactive learning context that motivates students to practice programming, providing them with appropriate challenging and scaffolding environments. Thus, as Bers (2020, p.185–186) states, we need apps that must be: age-appropriate, individually appropriate, and socially and culturally appropriate.

In addition, we should not forget that there are also CS unplugged activities to teach young people CT and CF that could be introduced in coding approaches because coding apps are just one part of the immense landscape of how CT and CF are taught. The next step would be to compare the effects of these apps in a context of a conventional curriculum, with no intervention and/or one that combines coding with unplugged activities. Whatever the motivations, we can learn from this approach whether young children best acquire CT and CF when taught using platform-specific coding exercises (with or without an open-ended approach), unplugged activities, or a hybrid approach using the advantages of both methods (Relkin et al, 2021). It would also be interesting to explore how these computational concepts can be supported and extended by using a combination of visual, auditory, or tactile objects (Yu and Roque, 2018) like Dash and Dot, Robot Turtles, and Cubetto (Hamilton et al, 2020).

Finally, the argument that open-ended designs like ScratchJr are better than apps with more structures like Lightbot is unsubstantiated; what matters is how the learning experience is structured and facilitated. We must highlight the importance of designing and incorporating a curriculum that promotes computational fluency (Bers 2020; Hamilton et al, 2020). For instance, none of the apps support a feature specifically conceived to promote collaboration between children. All apps are designed for a single user. Thus, there is a need for collaboration and communication strategies that are not focused on the tool but the tool’s teaching strategies and pedagogical choices (device and app). Educators who want to introduce coding into the early childhood classroom need these apps, but they also need a curriculum of powerful computer science ideas that are developmentally appropriate and a guiding framework that understands the whole child (Bers, 2020).

Limitations of the Study

Two factors may threaten the validity of the review:

• Study screening and data extraction. In other reviews, to ensure that the data generated are reliable, the analysis is undertaken by two or more coders, who code independently (Thomé, Scavarda and Scavarda, 2016). In the present study, the author discussed included and excluded papers with an expert panel consisting of two professionals with diverse backgrounds (Kitchenham, 2004). In consultation with the expert panel, the author adopted the Kitchenham (2004) recommendations, including gray literature, conference proceedings, and communicating with experts working in the field for any unpublished literature to retrieve a comprehensive list of the studies performed the topic. Furthermore, the included studies’ reference lists and previous systematic reviews were searched for additional relevant articles.

• Publication bias. The inclusion of only published articles may have introduced publication bias because studies with positive results are more likely to be published than studies with negative findings. Additionally, as non-English studies were excluded in the current review, it might be a source of potential publication bias (Kitchenham and Charters, 2007).

Conclusion

In many countries, the national curriculum aims to expose all pupils to some form of Computational Thinking and coding skills during their first-year studies. These needs, combined with the increased accessibility of touch screens, paraphrase the conversation from “When shall we introduce children to touchscreens and coding apps?” to “How shall we introduce children to touchscreens and coding apps?” The answer to this question is that appropriate instructional materials, pedagogical designs, and in-service teacher education are needed (Fessakis, Gouli, and Mavroudi, 2013; Strawhacker et al, 2018; Bers, 2019, 2020; Sheehan et al, 2019).

Many apps offering various programming lessons, puzzles, and challenges to teach core coding concepts to children have increased in recent years. Further research on this topic is needed on their ability to support early computer science learning truly. How the apps use interfaces and learning scenarios and how one is supposed to engage children differs playfully and productively in many ways (Sheehan et al., 2019). Nevertheless, few apps have been evaluated for their effectiveness, so we know little about what children can learn from them. The present study showed that the children could learn from playing with these four coding apps. Therefore, this study contributes to the limited body of research on the relationship between children’s digital literacy learning and playing with coding apps.

This study suggests that there is considerable value in the diverse ways presented to facilitate computational thinking and computational fluency, and thus there are challenging decisions that researchers and designers had to make in relative software product creation. It is crucial that researchers work on this field and try innovative approaches that capitalize on helpful ideas (Clarke-Midura et al, 2019). This can be most important considering studies highlighting the abundance of low-quality self-proclaimed educational apps that targeted young age children in literacy, mathematics, and general knowledge (Ackermann et al, 2020; Meyer et al, 2021).

We hope that this study can guide researchers who want to reveal more nuanced understandings of the learning processes that can provide opportunities for designing relevant adaptive scaffolds that can help young age students overcome their difficulties while developing computational thinking and computational fluency (Clarke-Midura et al, 2019). These topics can be exciting and rewarding for researchers, who get to explore an innovative approach while pursuing their research.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.657895/full#supplementary-material

References

Ackermann, L., Lo, C. H., Mani, N., and Mayor, J. (2020). Word Learning from a Tablet App: Toddlers Perform Better in a Passive Context. PloS one 15 (12), e0240519. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0240519

Basili, V. R. (1992). Software Modeling and Measurement: The Goal/Question/Metric Paradigm. Baltimore, United States: University of Maryland at College Park, 24.

Bers, M. U. (2020). Coding as a Playground: Programming and Computational Thinking in the Early Childhood Classroom. New York, United States: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003022602

Bers, M. U. (2019). Coding as Another Language: a Pedagogical Approach for Teaching Computer Science in Early Childhood. J. Comput. Educ. 6 (4), 499–528. doi:10.1007/s40692-019-00147-3

Bers, M. U. (2018). “Coding, Playgrounds and Literacy in Early Childhood Education: The Development of KIBO Robotics and ScratchJr,” in 2018 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON) (IEEE), 2094–2102.

Bers, M. U., González-González, C., and Armas–Torres, M. B. (2019). Coding as a Playground: Promoting Positive Learning Experiences in Childhood Classrooms. Comput. and Edu. 138, 130–145. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2019.04.013

Brennan, K., and Resnick, M. (2012). “Using Artifact-Based Interviews to Study the Development of Computational Thinking in Interactive media Design,” in Proceedings of Annual American Educational Research Association Meeting (Vancouver, BC: Canada), 1–25.

Byrd, L. (2020). Teach beyond Coding: How to Better Prepare Our Children for the Future. https://uxmag.com/articles/teach-beyond-coding-how-to-better-prepare-our-children-for-the-future

Ching, Y.-H., Hsu, Y.-C., and Baldwin, S. (2018). Developing Computational Thinking with Educational Technologies for Young Learners. TechTrends 62 (6), 563–573. doi:10.1007/s11528-018-0292-7

Chou, P.-N. (2020). Using ScratchJr to Foster Young Children's Computational Thinking Competence: A Case Study in a Third-Grade Computer Class. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 58 (3), 570–595. doi:10.1177/0735633119872908

Clarke-Midura, J., Lee, V. R., Shumway, J. F., and Hamilton, M. M. (2019). The Building Blocks of Coding: A Comparison of Early Childhood Coding Toys. Inf. Learn. Sci. 120 (7/8), 505–518. doi:10.1108/ILS-06-2019-0059

Dore, R. A., and Dynia, J. M. (2020). “Technology and Media Use in Preschool Classrooms: Prevalence, Purposes, and Contexts,” in Frontiers in Education (Frontiers), 5, 244. doi:10.3389/feduc.2020.600305

Ehsan, H., Beebe, C., and Cardella, M. (2017). “Promoting Computational Thinking in Children Using Apps,” in Proceedings of ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition (Columbus, Ohio). doi:10.18260/1-2--28772

Falloon, G. (2016). An Analysis of Young Students' Thinking when Completing Basic Coding Tasks Using Scratch Jnr. On the iPad. J. Comp. Assist. Learn. 32 (6), 576–593. doi:10.1111/jcal.12155

Falloon, G., Hale, P., and Fenemor, T. (2016). Planning and Implementing Coding in the Junior Classroom for Competency and Thinking-Skill Development. set 2016 (1), 8–16. doi:10.18296/set.0031

Fessakis, G., Gouli, E., and Mavroudi, E. (2013). Problem Solving by 5-6 Years Old Kindergarten Children in a Computer Programming Environment: A Case Study. Comput. and Edu. 63, 87–97. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2012.11.016

Fessakis, G., Komis, V., Dimitracopoulou, A., and Prantsoudi, S. (2019). Overview of the Computer Programming Learning Environments for Primary Education. Rev. Sci. Math. ICT Edu. 13 (1), 7–33.

Flannery, L. P., Silverman, B., Kazakoff, E. R., Bers, M. U., Bontá, P., and Resnick, M. (2013). “Designing ScratchJr: Support for Early Childhood Learning through Computer Programming,” in Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children (New York, NY, USA: IDC ’13. ACM.), 1–10.

Galway, G. J., Maddigan, B., and Stordy, M. (2020). Teacher Educator Experiences of iPad Integration in Pre-service Teacher Education: Successes and Challenges. Technol. Pedagogy Edu. 29, 1–19. doi:10.1080/1475939X.2020.1819397

Giannakoulas, A., and Xinogalos, S. (2018). A Pilot Study on the Effectiveness and Acceptance of an Educational Game for Teaching Programming Concepts to Primary School Students. Educ. Inf. Technol. 23 (5), 2029–2052. doi:10.1007/s10639-018-9702-x

Gomes, T. C. S., Falcão, T. P., and Tedesco, P. C. D. A. R. (2018). Exploring an Approach Based on Digital Games for Teaching Programming Concepts to Young Children. Int. J. Child-Computer Interaction 16, 77–84. doi:10.1016/j.ijcci.2017.12.005

Govind, M., Relkin, E., and Bers, M. U. (2020). Engaging Children and Parents to Code Together Using the ScratchJr App. Visitor Stud. 23 (1), 46–65. doi:10.1080/10645578.2020.1732184

Hamilton, M., Clarke-Midura, J., Shumway, J. F., and Lee, V. R. (2020). An Emerging Technology Report on Computational Toys in Early Childhood. Tech. Know Learn. 25 (1), 213–224. doi:10.1007/s10758-019-09423-8

Herheim, R., and Severina, E. (2020). “Scratch Programming and Student’s Explanations,” in Proceedings of the Tenth ERME Topic Conference (ETC 10) on Mathematics Education in the Digital Age (MEDA), 16-18 September 2020 (Linz, Austria: Johannes Kepler University).

Hutchison, A., Nadolny, L., and Estapa, A. (2015). Using Coding Apps to Support Literacy Instruction and Develop Coding Literacy. Read. Teach. 69 (5), 493–503. doi:10.1002/trtr.1440

Jin, Y., and Zha, S. (2019). Weave Coding into K-5 Curricula as New Literacies. Idd 48 (2), 49–66. doi:10.1108/idd-09-2019-0069

João, P., Nuno, D., Fábio, S. F., and Ana, P. (2019). A Cross-Analysis of Block-Based and Visual Programming Apps with Computer Science Student-Teachers. Edu. Sci. 9 (3), 181. doi:10.3390/educsci9030181

Kalogiannakis, M., Ampartzaki, M., Papadakis, S., and Skaraki, E. (2018). Teaching Natural Science Concepts to Young Children with mobile Devices and Hands-On Activities. A Case Study. Ijtcs 9 (2), 171–183. doi:10.1504/ijtcs.2018.090965

Kamenetz, A. (2015). Engage Kids with Coding by Letting Them Design, Create, and Tell Stories. https://www.kqed.org/mindshift/43097/engage-kids-with-coding-by-letting-them-design-create-and-tell-stories

Karadeniz, S., Samur, Y., and Ozden, M. Y. (2014). Playing with Algorithms to Learn Programming: A Case Study on 5 Years Old Children. Sydney, Australia: Paper presented at the international conference on information technology and applications.

Kazakoff, E. R. (2014). Cats in Space, Pigs that Race: Does Self-Regulation Play a Role when Kindergartners Learn to Code? The USA: Doctoral dissertation, Tufts University).

Kazakoff, E. R. (2015). “Technology-based Literacies for Young Children: Digital Literacy through Learning to Code,” in Young Children and Families in the Information Age, Educating the Young Child 10. Editors K. L. Heider, and M. Renck Jalongo (Dordrecht: Springer), 43–60. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9184-7_3

Kitchenham, B., and Charters, S. (2007). “Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering,”. Technical Report EBSE-2007-01, School of Computer Science and Mathematics (Keele, Newcastle, United Kingdom: Keele University).

Kitchenham, B. (2004). “Procedures for Undertaking Systematic Reviews,”. Joint Technical Report. Computer Science Department, Keele University (TR/SE0401) (National ICT Australia Ltd).

Laporte, L., and Zaman, B. (2018). A Comparative Analysis of Programming Games, Looking through the Lens of an Instructional Design Model and a Game Attributes Taxonomy. Entertainment Comput. 25, 48–61. doi:10.1016/j.entcom.2017.12.005

Lowe, T., and Brophy, S. (2019). “Identifying Computational Thinking in Storytelling Literacy Activities with Scratch Jr,” in ASEE Annual Conference Proceedings (Tampa, Florida, USA: American Society for Engineering Education), 10.

Meyer, M., Zosh, J. M., McLaren, C., Robb, M., McCaffery, H., Golinkoff, R. M., and Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2021). How Educational Are “Educational” Apps for Young Children? App Store Content Analysis Using the Four Pillars of Learning Framework. J. Child. Media, 1–23. doi:10.1080/17482798.2021.1882516

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., and Altman, D. G.Prisma Group. (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Plos Med. 6 (7), e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Murcia, K., Pepper, C., Joubert, M., Cross, E., and Wilson, S. (2020). A Framework for Identifying and Developing Children’s Creative Thinking while Coding with Digital Technologies. Issues Educ. Res. 30 (4), 1395–1417.

Nouri, J., Zhang, L., Mannila, L., and Norén, E. (2020). Development of Computational Thinking, Digital Competence and 21stcentury Skills when Learning Programming in K-9. Edu. Inq. 11 (1), 1–17. doi:10.1080/20004508.2019.1627844

Papadakis, S., Kalogiannakis, M., and Zaranis, N. (2016). Developing Fundamental Programming Concepts and Computational Thinking with ScratchJr in Preschool Education: a Case Study. Ijmlo 10 (3), 187–202. doi:10.1504/ijmlo.2016.077867

Pelánek, R., and Effenberger, T. (2020). Design and Analysis of Microworlds and Puzzles for Block-Based Programming. Comp. Sci. Edu., 1–39. doi:10.1080/08993408.2020.1832813

Pila, S., Aladé, F., Sheehan, K. J., Lauricella, A. R., and Wartella, E. A. (2019). Learning to Code via Tablet Applications: An Evaluation of Daisy the Dinosaur and Kodable as Learning Tools for Young Children. Comput. and Edu. 128, 52–62. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2018.09.006

Portelance, D. J., and Bers, M. U. (2015). “Code and Tell: Assessing Young Children's Learning of Computational Thinking Using Peer Video Interviews with ScratchJr,” in Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children (Boston, MA: ACM), 271–274.

Portelance, D. J., Strawhacker, A. L., and Bers, M. U. (2016). Constructing the ScratchJr Programming Language in the Early Childhood Classroom. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 26 (4), 489–504. doi:10.1007/s10798-015-9325-0

Rehmat, A. P., Ehsan, H., and Cardella, M. E. (2020). Instructional Strategies to Promote Computational Thinking for Young Learners. J. Digital Learn. Teach. Edu. 36 (1), 46–62. doi:10.1080/21532974.2019.1693942

Relkin, E., de Ruiter, L. E., and Bers, M. U. (2021). Learning to Code and the Acquisition of Computational Thinking by Young Children. Comput. and Edu. 169, 104222. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104222

Resnick, M. (2017). Lifelong Kindergarten: Cultivating Creativity through Projects, Passion, Peers, and Play. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. doi:10.7551/mitpress/11017.001.0001

Resnick, M. (2003). Playful Learning and Creative Societies. Edu. Update 8 (6). Retrieved April 20, 2021 from http://web.media.mit.edu/∼mres/papers/education-update.pdf. doi:10.1023/a:1025632719774

Resnick, M., Maloney, J., Monroy-Hernández, A., Rusk, N., Eastmond, E., Brennan, K., et al. (2009). Scratch. Commun. ACM 52 (11), 60–67. doi:10.1145/1592761.1592779

Resnick, M., and Siegel, D. (2015). A Different Approach to Coding. Int. J. People-Oriented Programming 4 (1), 1–4. doi:10.4018/IJPOP.2015010101

Román-González, M., Moreno-León, J., and Robles, G. (2019). “Combining Assessment Tools for a Comprehensive Evaluation of Computational Thinking Interventions,” in Computational Thinking Education (Singapore: Springer), 79–98. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-13-6528-7_6. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-6528-7_6

Rose, S. (2016). “Bricolage Programming and Problem Solving Ability in Young Children: An Exploratory Study,” in Proceedings of 10th European Conference for Game Based Learning (United Kingdom: Paisley), 914–921.

Rose, S. (2019). Developing Children’s Computational Thinking Using Programming Games. United Kingdom: Doctoral dissertation, Sheffield Hallam University.

Rose, S., Habgood, J., and Jay, T. (2017). An Exploration of the Role of Visual Programming Tools in the Development of Young Children’s Computational Thinking. Electron. J. e-learning 15 (4), 297–309.

Sheehan, K. J., Pila, S., Lauricella, A. R., and Wartella, E. A. (2019). Parent-child Interaction and Children's Learning from a Coding Application. Comput. and Edu. 140, 103601. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103601

Strawhacker, A., and Bers, M. U. (2019). What They Learn when They Learn Coding: Investigating Cognitive Domains and Computer Programming Knowledge in Young Children. Education Tech. Res. Dev. 67 (3), 541–575. doi:10.1007/s11423-018-9622-x

Strawhacker, A., Lee, M., and Bers, M. U. (2018). Teaching Tools, Teachers' Rules: Exploring the Impact of Teaching Styles on Young Children's Programming Knowledge in ScratchJr. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 28 (2), 347–376. doi:10.1007/s10798-017-9400-9

Sullivan, A., Bers, M., and Pugnali, A. (2017). The Impact of User Interface on Young Children’s Computational Thinking. J. Inf. Tech. Educ. Innov. Pract. 16 (1), 171–193. doi:10.28945/3768

Sullivan, A., and Umashi Bers, M. (2019). Computer Science Education in Early Childhood: the Case of ScratchJr. JITE:IIP 18 (1), 113–138. doi:10.28945/4437

Terzopoulos, G., Satratzemi, M., and Tsompanoudi, D. (2019). “Educational Mobile Applications on Computational Thinking and Programming for Children under 8 Years Old,” in Interactive Mobile Communication, Technologies and Learning (Cham: Springer), 527–538.

Thomé, A. M. T., Scavarda, L. F., and Scavarda, A. J. (2016). Conducting Systematic Literature Review in Operations Management. Prod. Plann. and Control. 27 (5), 408–420. doi:10.1080/09537287.2015.1129464

Thuzar, A., and Nay, A. (2015). “Teaching and Learning through Creating Games in ScratchJr: Who Needs Variables Anyway!,” in 2015 IEEE Blocks and beyond Workshop (Blocks and beyond) (Washington, DC; USA: IEEE), 139–141.

Tikva, C., and Tambouris, E. (2020). Mapping Computational Thinking through Programming in K-12 Education: A Conceptual Model Based on a Systematic Literature Review. Comput. and Edu. 162, 104083. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104083

Walsh, C., and Campbell, C. (2018). “Introducing Coding as a Literacy on mobile Devices in the Early Years,” in Mobile Technologies in Children’s Language and Literacy: Innovative Pedagogy in Preschool and Primary Education (Emerald Publishing Limited), 51–66. doi:10.1108/978-1-78714-879-620181004

Wang, A. I., and Tahir, R. (2020). The Effect of Using Kahoot! for Learning - A Literature Review. Comput. and Edu. 149, 103818. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103818

Yu, J., and Roque, R. (2019). A Review of Computational Toys and Kits for Young Children. Int. J. Child-Computer Interaction 21, 17–36. doi:10.1016/j.ijcci.2019.04.001

Keywords: apps and smartphones, coding, computational thinking, computational fluency, preschool education, primary education

Citation: Papadakis S (2021) The Impact of Coding Apps to Support Young Children in Computational Thinking and Computational Fluency. A Literature Review. Front. Educ. 6:657895. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.657895

Received: 24 January 2021; Accepted: 06 May 2021;

Published: 10 June 2021.

Edited by:

Christothea Herodotou, The Open University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Nashwa Ismail, The Open University, United KingdomPinaki Chakraborty, Netaji Subhas University of Technology, India

Michelle Neumann, Griffith University, Australia

Copyright © 2021 Papadakis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Stamatis Papadakis, c3RwYXBhZGFraXNAdW9jLmdy

Stamatis Papadakis*

Stamatis Papadakis*