- 1Department of Education, National Kaohsiung Normal University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

- 2Department of Psychology, Fo Guang University, Yilan County, Taiwan

The purpose of this study was to explore the effects of integrating meaning-centered positive education (MCPE) and the second wave positive psychology (PP2.0) into a university English speaking class. The study adopted Wong’s CasMac model of PP2.0 and designed a series of English lessons which aimed to understand the meaning of life through the perspectives of PP2.0 and its focus on MCPE. The participants were 38 university students, with upper-intermediate English proficiency, enrolled in an English speaking class. They participated in the English program for 15 weeks and 2 h each week. The quantitative data was collected from survey of the CasMac Measure of Character and analyzed with the paired t-test method, and the qualitative data analysis was collected from students’ weekly learning sheets and journals. The results show that the integration of MCPE and PP2.0 in a university English class is feasible to enhance students’ understanding of mature happiness through the CasMac model and to promote their meanings in life. According to the research findings, it is suggested that the CasMac model can be applied to other fields or other groups who need help to enhance life meaning and improve wellbeing. Particularly under the pandemic of COVID-19, there are people encountering traumas, losses, and sorrows and it is crucial to transform sufferings with the support of approaching mature happiness.

Introduction

In this era of constant changes and crizes, COVID-19 pandemic for example, we human beings have been revolutionizing and changing our assumptions on world orderliness and life patterns, which then has further brought unprecedented anxiety, uncertainty, and doubt of the meaning of life. Thus, the certainty of the pursuit of the meaning of life is needed (Jong et al., 2020; Trzebiński et al., 2020; Wong et al., 2020). Positive psychology certainly brings hope and optimism, but it is not enough to respond to the dark sides of the reality of life, for example, the existing natural disasters and man-made chaos which have been threatening lives and well-being of the world. Although the positive education of positive psychology emphasizes positive organizations, little attention has been paid to the implementation of a curriculum that enables students to face setbacks and sufferings, and to build up resilience, morality, character improvement, and self-transcendence (Kristjánsson, 2012; Wong, 2017a, Wong, 2019a).

The meaning-centered positive education (MCPE) proposed by Wong et al. (2016) was informed by existential positive psychology (Wong, 2010a) and second wave positive psychology (PP2.0) (Wong, 2011), and based on Frankl’s logotherapy (1985). It can be seen as a potential cure of the current era of chaos and upheaval such as the COVID-19 pandemic. MCPE is based on a theory that focused more on meaning and value (Wong, 2021a). Many psychological theories have pointed out that people have the instinctive motivation to pursue happiness and avoid suffering; however, Frankl (Frankl, 1985; Frankl, 2000) believes that the pursuit of meaning is the deeper motivation of human existence. People can live for meaning or die for it. What the world needs now is the pursuit and resurgence of spirituality, along with the hope to a world threatened by global terrorism and disasters, that is, to find mature happiness based on inner peace and life balance (Wong, 2020a; Wong, 2020b). Meaning-centered counseling and therapy has been practiced in related fields, such as addiction (Wong, 2013a) and clinical treatment by emphasis on and in discovering meaning in life, tapping into resilience and healing capacities (Breitbart and Poppito, 2014; Dezelic and Ghanoum, 2016). The application of meaning-based education has been used in elementary classrooms (e.g., The D.R.E.A.M. program, Armstrong et al., 2019); however, in higher education, it is scarce and worth exploring.

In the trend of globalization, Taiwan, like other developed countries, is also facing the prevalence of emphasis on science, technology, and materialism, which has challenged the traditional culture and values. Students at all levels of school and people from all walks of life too have confronted senses of confusion of value and loss of meaning. Students have long been prone to suicidal behaviors or various disorderly behaviors when facing stress from study or life events. Being aware of the problems, in 1997, the Taiwan Department of Education took action (later in 1999 it reformed to the Ministry of Education of Taiwan based on the government organizational structure), hoping to guide students to respect and cherish life, and to live out their individual meaning and value. Later, it became a formal part of the curriculum for secondary schools and then extended to elementary schools, kindergartens, and universities. Based on the guidelines of 12-years basic education, life education has now become one of the focuses of the official curriculum of elementary, secondary, and high schools since the 2019 school year (Chang, 2020; Ministry of Education, 2014; Sun, 2015).

According to the educational guidelines, Taiwan’s life education aims to echo the aforementioned meaning, spiritual development, and the pursuit of mature happiness with the foresight of global educational trends, and to lead students to pursuit positive meanings in life (Chang, 2006a; Chang, 2006b; Sun, 2009; Chang, 2016; Chang et al., 2016; 2015). This emphasis is in contrast to the western approach of positive psychology, which focuses on the individualism of one’s happiness and success (Lopez et al., 2021). The practice of life education helps students reflect and construct the meaning and value of life (Chi, 2002; Chen, 2004; Chang, 2006a; Chang, 2006b; Chen and Lin, 2006; Chang et al., 2016; Chang, 2020). However, life education in Taiwan tertiary education is usually an elective course for general education. Not all the students are able to benefit from it. For most college and university students, this may be their final stage of formal education. They are also, according to Erikson’s theory, in a stage of identity development crisis (Erikson, 1968). Realizing their life goal and meaning of life is particularly important for tertiary students. In addition, because technical and vocational colleges place more focus on professional skills than regular universities, humanistic literacy and life-related education courses are practicably extruded. The importance of life education can be more critical to students in technical and vocational universities (Chang, 2006b; Chen and Lin, 2006).

Given the constraints of the educational emphases in colleges and universities, life education in tertiary education may be integrated into the existing heaving syllabus without being extruded or extruding other courses (Chang, 2006a; Chang et al., 2006). The first author is an English lecturer at a national university of science and technology, and the authors believe that meaning-centered positive education (MCPE) complies with the second wave positive psychology (PP2.0), which focuses on improving the meaning and value of life and is consistent with the purpose of life education in Taiwan. Hence the researchers of the paper were inspired to conduct this study.

Life education in this study is considered as an adaptive connection to positive education with an indigenous educational and cultural background. It takes the Asian/Chinese approach to positive education, which focuses on how to be a responsible citizen and a good and wise person as a way of collectivism to meaningful living and human flourishing, This goal is consistent with that of the PP2.0 (Wong, 2017b; Wong and Bowers, 2018; Wong, 2019a).

The purpose of this study was to explore the effects of integrating PP2.0 (Wong, 2011) into a university English class and to examine the design, implementation, and evaluation of the CasMac model in MCPE (Wong, 2017a; Wong, 2017b; Wong, 2019a). It aimed to help students understanding their attitudes toward life and well-being, as well as helping them understand that suffering is the reality of life, and mature happiness can be achieved by facing, transforming, and transcending suffering (Wong, 2019b).

The Second Wave Positive Psychology (PP2.0)

In order to heal wounds and gain true happiness, people have to face the dark side of survival and pursue self-transcendence in order to achieve greater meaning (Wong, 2010a). This argument (the focus of negative existence) further represents the synthesis and improvement to the argument of first wave positive psychology (PP). PP focuses on what makes life most worth living and aims to improve the quality of life with an emphasis on positive subjective experience, positive individual traits, and positive institutions (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Research has shown criticism to its existing limitations and defects, such as reality distortion like positive illusions (Taylor and Brown, 1988; Kristjánsson, 2012; Kristjánsson, 2012), narrow focus (Taylor, 2001; Norem and Chang, 2002; Sample, 2003; Martin, 2006; Wong, 2016a; Wong and Roy, 2017), role of negativity (Held, 2002; Held, 2004; Schneider, 2011; Wong, 2016a; Wong and Roy, 2017), cross-cultural issues (Norem and Chang, 2002; Held, 2004; Becker and Marecek, 2008; Christopher et al., 2008; Christopher and Hickinbottom, 2008; Chang et al., 2016; Wong, 2016a), problem of elitism (Wong and Roy, 2017), and toxic positivity (Gross and Levenson, 1997; Lomas, 2017; Lomas, 2018; Lomas, 2019; Lukin, 2019; Quintero and Long, 2019).

PP2.0 is a scientific advancement and provides an appropriate example for meaning-oriented research and intervention (Wong, 2016a; Wong, 2019a), well-being, and the realization of meaning in the reality of suffering and death (Frankl, 1985; Bretherton and Ørner, 2004; Schneider, 2011; Taheny, 2015). It emphasizes the importance of a balance and interaction between positive and negative emotions (Wong, 2011; Wong, 2012a; McMahan et al., 2015; Lomas and Ivtzan, 2016; Wong, 2016a; Wong and Roy, 2017; Wong, 2020a; Wong, 2021a), the dialectical principles of Chinese psychology (Wong, 2009), the bio-behavioral dual-system model of adaptation (Wong, 2012a), and cross-cultural positive psychology (Chang et al., 2016; Wong and Roy, 2017). In particular, it complies with the Eastern philosophy of the law of nature, Yin and Yang (Wong, 2020b), the research for multiple indigenous positive psychologies (Wong, 2013b), and a much broader list of variables that contribute to well-being and flourishing (Wong, 2016b). In addition to supporting the historical and dialectical viewpoints of PP2.0, humanism is also advocated as the basis and a meaning-centered approach to help finding the individual’s psychological drive for meaning-making and meaning-seeking (Waterman, 2013; Wong, 2016b; Wong, 2017a).

Meaning plays an important role in the application of positive psychology, and research also shows that interventions to strengthen meaning are important (Batthyany and Russo-Netzer, 2014; Steger et al., 2013; Wong, 2012a). The search for meaning, or in Frankl (1985) terminology, “will to meaning,” refers to making sense, order, or coherence out of one’s existence. Purpose refers to intention, some function to be fulfilled, or goals to be achieved, a sense of personal meaning means having a purpose and striving toward a goal. Research has shown that, when things go wrong, people are more likely to seek meaning (Wong, 2016a; Wong and Weiner, 1981). Meaning makes pain more tolerable and makes people more resilient (Frankl, 1985; Wong and Wong, 2012). Most deep insights into the meaning of life are discovered by those who have experienced extreme pain (Frankl, 1985; Guttman, 2008).

Meaning-Centered Positive Education (MCPE) Intervention

MCPE, which places more emphasis on personal, social, and spiritual development, is an approach that provides a more balanced positive education and is more consistent with the spirit of life education (Wong, 2017a; Wong, 2017b). It also teaches students that a good life consists of meaning, virtue, and mature happiness, which come from the deep satisfaction of making a unique contribution to humanity and learning how to become a fully functioning person. And mature happiness is considered a by-product of pursuing a meaningful life rather than the ultimate goal of life (Wong, 2007).

The design of the life education program in this study was inspired by Wong’s Meaningful Living Group (Wong, 2016c), a community-based meaning-centered positive group intervention, which was informed by existential positive psychology (Wong, 2010a) and PP2.0 (Wong, 2011). Wong’s meaning-centered positive group intervention consists of 12 sessions in each cycle. It runs every other week and is free of charge. Similarly, our program lasted for 15 weeks in the study. Every week the teacher gave a lecture that provided the content and conceptual ideas for students to learn important principles of meaningful living before the group discussion. The teacher implemented PP2.0 research findings as well as positive education derived from the Eastern cultural background, particularly the focus and application on Wong’s CasMac model (Wong, 2019a).

The CasMac Model

PP2.0 seeks a balance through the dialectical interplay between positive and negative in adaptation (Wong, 2011; Wong, 2012a; McMahan et al., 2015; Lomas and Ivtzan, 2016). Wong constructs the CasMac model (Wong, 2019a), which consists of six components, each representing a different virtue or attitude: Courage, Acceptance, Self-transcendence, Meaning, Appreciation, and Compassion. According to Wong (2019a); Wong (2019b); Wong (2020a), moral education or character building will provide a rock-like foundation to build a fulfilling and successful life. The CasMac model is based on existential-spiritual values and there is empirical support for each of the factor’s importance for wellbeing and life meaning (Wong and Roy, 2017; Wong, 2019a; Wong, 2019b). Its characteristics help guide people to transcend difficulties and sufferings, to focus on the meaning-mindset, and to gradually strive toward mature happiness (Wong, 2016a; Wong, 2019b; Wong, 2020a).

Courage

Courage is a universal virtue, and courageous individuals in all cultures have survived through times of hardship and integrity (Rachman, 1990; Putnam, 1997; Miller, 2000). It is believed that an individual develops courage by doing courageous acts (Aristotle, 1962) and there is the support that courage is a moral habit to be developed by practice (Cavanagh and Moberg, 1999). When one holds more bravery and persistence, more integrity will increase to reach a state of feeling vital in the face of things that oppose it, and this results in being more courageous in building the character (Seligman, 2011; Lopez et al., 2021). Courage is also to embrace the dark side of human existence, make positive changes in our own lives, and stand for what is right according to our innate conscience and the common good (Wong, 2019a).

Acceptance

Acceptance of the bleak reality and what cannot be changed or is beyond our control (Wong, 2004; Wong, 2010b; Wong, 2019a) as is opposed to avoidance. It involves full recognition and awareness of our feelings and accepts them as things that exist without trying to change them; even they are unreasonable and painful, instead consciously replacing the painful feelings with positive and inspiring ones (Harris, 2008). Mindful acceptance is helpful to increase our awareness and regulate our negative emotions (McKay and West, 2016). Many scholars have also discussed that self-acceptance is the key to psychological well-being (Ellis, 1995; Ryff and Singer, 2008; Williams and Lynn, 2011).

Self-Transcendence

According to Maslow (1971), self-transcendence represents the most holistic level of higher consciousness, relating to oneself, significant others, human beings in general, nature, and the cosmos. The pursuit of self-transcendence offers the most promising path to live a life of virtue, happiness, and meaning (Frankl, 1985), and Wong (2021a) in particular considers it as the prototype of existential positive psychology, also known as PP2.0. Self-transcendence refers to the relationship that the individual has with himself and to overcome or transform setbacks, obstacles, and internal/external limitations in our striving to make a significant contribution to others (Wong, 2014a; Wong, 2019a). It also develops our character strengths and virtue, but also increases our capacity for healing and flourishing (Wong, 2012a; Batthyany and Russo-Netzer, 2014).

Meaning-Mindset

According to Frankl (1985), the most effective way to attain healing and wholeness is through the spiritual path of discovering meaning. Meaning-mindset is as a lens to look at life as a whole as well as the present situation in order to discover what is good, beautiful, and the right thing to do (Wong, 2019a). Also, it is what is needed for cultures that value social responsibility, civic virtues, and service to humanity (Wong, 2012b). Through striving for meaning and the outcome of finding meaning, deep satisfaction and enduring happiness can emerge (Wong, 2016a).

Appreciative Attitude

Frankl (1985) has identified that by having an appreciative attitude, one will find beauty and meaning as the pathways of meaning-seeking (Wong, 2016a). Appreciative attitudes toward life and other people, including unpleasant individuals and uncomfortable situations can help actively, continuously appreciating the good things in your life and the thankfulness will bring joy to you and others (Blank, 2017; Wong, 2019a). An appreciative and defiant attitude helps complete positive mental health (Wong, 2014b). Moreover, in Buddhist psychology, as well as in indigenous traditional cultures, there is a consistent teaching that people should be grateful as the popular Chinese saying, “Whenever you drink, remember its source (飲水思源)” (Wong, 2016a).

Compassion

Gilbert (1989) points out that the caring-giving social mentality, which underlies compassion, includes caring, empathy, and sympathy; furthermore, it is a multilayered, dense construct that overlaps various other constructs such as loving-kindness, empathy, attachment, caregiving, and pro-social behavior, it cares for all people, living things, and oneself (Wong, 2006; Wong, 2019a). Compassion is an affective state defined by a subjective feeling, rather than compassion as an attitude (Goetz et al., 2010) and is also linked to positive affect (Davidson, 2002).

The CasMac model complements Seligman’s PERMA model (Seligman, 2011), which suggests that it makes up five important blocks of well-being and happiness: positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and acceptance, as well as the building of characters and virtues (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000; Peterson and Seligman, 2004; Seligman, 2004). The awareness of PERMA can help increase well-being by focusing on combinations of feeling good, meaningful living, establishing supportive and friendly relationships, accomplishing goals, and being fully engaged with life. However, according to Wong (2021b), PERMA model is restricted by its failure to address existential suffering, such as the following points:

1. Existential anxieties and negative emotions are an inescapable aspect of life.

2. Reality requires us to do things that we don’t particularly enjoy, either for making a living or fulfilling some moral obligation of social responsibility.

3. A common Western value, such as an individualistic and instrumental view, makes genuine or authentic relationships impossible.

4. A life purpose can be misguided when it ideologically or egotistically motivated at the expense of ethical and moral considerations.

5. Accomplishment can lead to either arrogance or envy and disappointment.

Nonetheless, CasMac is more relevant in adversities and times of difficulty and hardship as it is supported by PP2.0 and focuses on our need for courage, humility, compassion, and connections (Niemiec, 2018; Wong, 2019a; Van Tongeren and Van Tongeren, 2020; Wong, 2020b; Rosmarin, 2021). Wong further discusses that mature happiness will complement wellbeing which is characterized by inner harmony, acceptance, gratitude, contentment, and having peace with oneself, others, and the world (Wong and Roy, 2017; Wong and Bowers, 2018).

It is clear that PP2.0 is closer to the actual appearance of realities in life; that is, life is full of challenges, setbacks, and various sufferings. The ultimate meaning of life can be guided with the courage to overcome difficulties and fulfill self-transcendence, and transform it into the foundation of a meaningful life. MCPE intervention and the CasMac model thus have the capacity of developing mature attitudes toward happiness and meaning of life in students.

Materials and Methods

This study conformed to the code of ethics and our research obtained written informed consent from the participants. The following will further clarify the participants, materials and methods, procedures, and measures.

Participants

The participants were from a national university of science and technology in southern Taiwan. These students had an upper-intermediate English proficiency according to the university English placement test based on levels of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). There were 38 students, 11 males and 27 females aged between 19 and 23, enrolled in this English speaking class. It was an elective course and available to all the students in the university; therefore, the students came from various colleges, departments, and all years in the university.

Methods

Since the course in this study was limited to students of upper-intermediate English proficiency and it was also the only advanced English class in the university, it was not able to find an appropriate control group. Therefore, this study adopted the one-group pretest-posttest design. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected. The quantitative data was collected from the CasMac survey and analyzed with paired t-test. The qualitative data was collected from the weekly learning sheets and served as the supporting data for the effectiveness of the study. The experimental materials were based on the CasMac model, which aims to guide learners toward understanding the meaning of life and mature happiness. The teacher (first author) attempted to make the learning environment an open, informal setting where the teacher and students can communicate freely. Students’ opinions were valued and supported by all members in the class. The instruction practiced a collaborative approach and encouraged critical thinking and freedom of mind. The class encouraged dialogue and conversation between students and teachers, and also created opportunities to bring forward inspirations and discussions. Group work was common and was an important aspect of this class in order to stimulate dynamic interactions in the class.

Since this was a formal English speaking class, the class also needed to comply with the objectives of the university curriculum. Regarding the teaching method, a communicative approach of language teaching was chosen. This approach addressed the idea that successful language learning comes from having to communicate real meaning (Richards and Rodgers, 1986; Brown, 1987; Richards, 2006). When learners are involved in real communication, their natural strategies for language acquisition will be used, and this will allow them to learn to use the language (Nunan, 1991; Richards, 2006). For example, practicing question forms by asking learners to interact and find out personal information about their classmates is an example of the communicative approach, as it involves meaningful communication.

The concepts and tenets of PP2.0 and MCPE were integrated into classroom learning, teaching, and learning materials. For example, the vocabulary, quotes, lectures, questions, and journals were compiled based on the positions of PP2.0. The lectures were related to the concepts of positive psychology and in-class activities were developed to facilitate in-depth discussions on how to develop virtues, values, wellbeing, and resilience, and how to overcome challenges and overstep difficulties.

During the study, conducted from March to June 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic had been spreading and causing unprecedented crizes. Protective measures were being taken, such as wearing masks and keeping physical distancing from others; when it comes to education, partial or full school closures were the consequences. At this moment, the importance of PP2.0 and MCPE became particularly more prominent. It was just the time to show that one needs to develop the skills, attitudes, and habits of living a life of harmony and balance in a dangerous and unpredictable world (Wong, 2020b).

Procedure

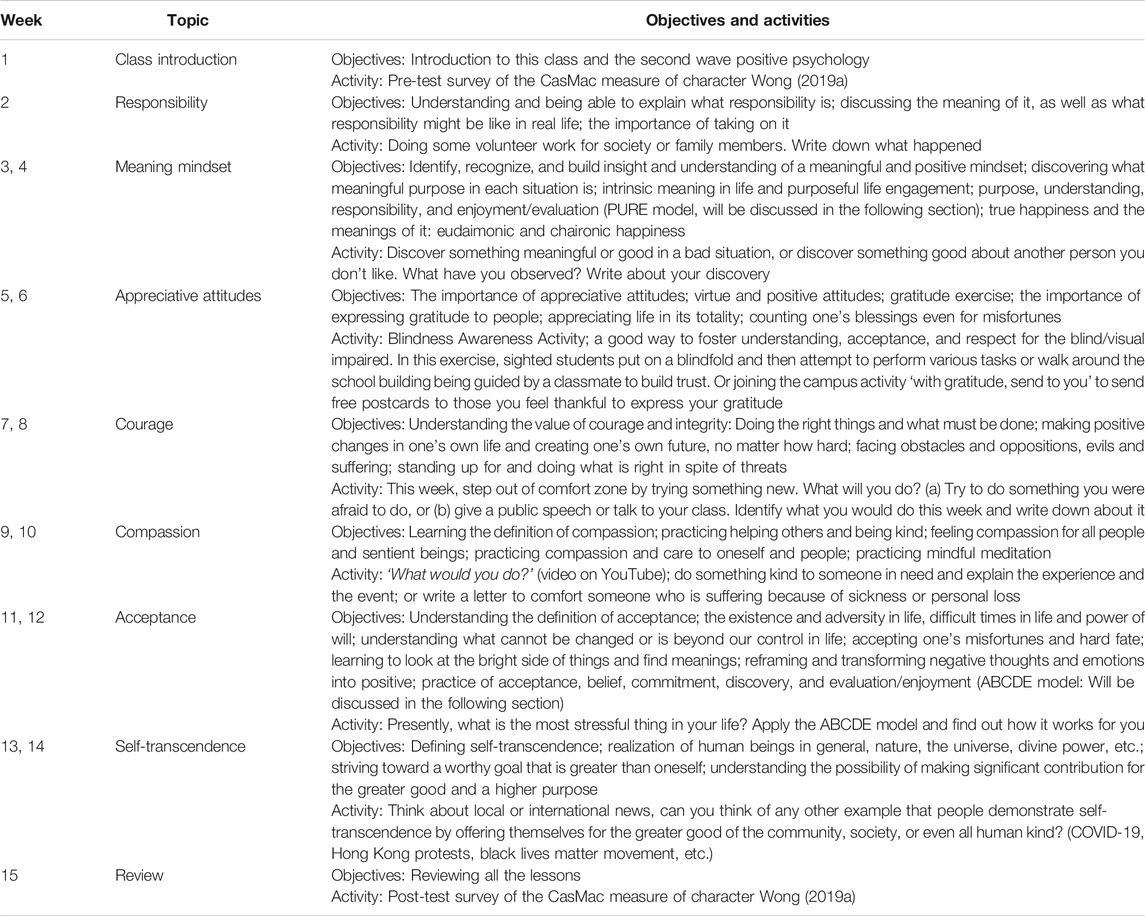

The classes lasted for 15 weeks. The learning materials were distributed in class for lectures, reading, and reflecting at the first session, followed by a 40-min interactive discussion at the second session. On designing the in-class activities, what was concerned most was to enable students to reflect and explore themselves through the windows of PP2.0 and MCPE. Based on the CasMac model, the lessons were organized into seven topics in 15 weeks Table 1 summarizes the seven topics, objectives, and activities regarding the MCPE intervention.

The weekly lesson consisted of the following components: vocabulary, lecture, quotes, questions, and journal writing. These were designed and developed based on the positions of PP2.0 to nurture students with good characters such as virtues, resilience, wellbeing, and meaning, which are also known as the four pillars of a good life (Wong, 2011). The vocabularies were the words often used in PP2.0. They were chosen with the aim to help students to expand their word bank and, which in turn, help to understand the topics discussed; likewise to quotes.

The lectures enabled the students to learn and discover personal strengths and, furthermore, the meaning of life through the lens of MCPE. It was hoped that through the learning processes, the students were able to make further explorations on their own meaning quest and then understand themselves better. Based on the research of Frankl (2000) and Wong (2017a), the spiritual part of human nature is considered to play an important role in the higher level of human nature. Deliberation on this part of human nature was practiced through reflecting and discussing issues related to the pursuit of the meaning of life through free will and the effort of self-transcendence, as well as facing the dark side of life as the reality in itself.

Expressive writing was also involved in class activities. Parks and Biswas-Diener (2013) pointed out that the most meaningful interventions involve personal narratives to make sense of traumatic or stressful events. Lyubomirsky et al, (2006) found that participants who wrote about a past positive event reported relative life satisfaction. Besides, writing about one’s positive future was beneficial (Sheldon and Lyubomirsky, 2006). Students had the opportunities to write down and reflect on the issues that were being delivered, as forms of in-class writing assignments, journals, or so on.

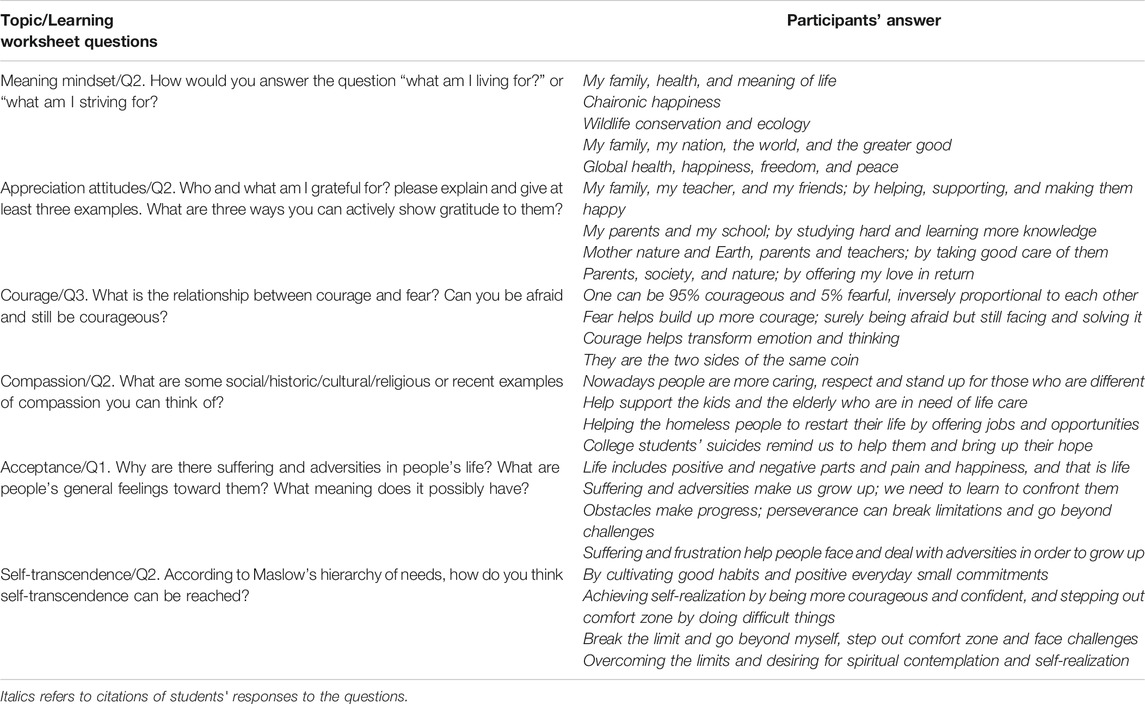

Questions based on the seven topics were discussed. By having these interventions as the in-class activities, the teacher taught the vocabulary and phrases that students were expected to learn, practice, and comprehend the content in order to answer the questions in the discussion followed by the lecture. Students were allowed to take time to finish the questions regarding each topic; for example.

1. Responsibility (three questions, e.g., “Do you think we have different responsibility based on our different social identities? What social identities do you have?”),

2. Meaning mindset (six questions, e.g., “How would you answer the question “What am I living for?” or “What am I striving for?”),

3. Appreciative attitude (three questions, e.g., “Who and what am I grateful for? please explain and give at least three examples. What are three ways you can actively show gratitude to them?”),

4. Courage (six questions, e.g., “What is the relationship between courage and fear? Can you be afraid and still be courageous? Can you be courageous without fear?”),

5. Compassion (six questions, e.g., “What are some social/historic/cultural/religious or recent examples of compassion you can think of?”),

6. Acceptance (seven questions, e.g., “Why are there suffering and adversities in people’s life? What are people’s general feelings toward them? What meaning does it possibly have?”),

7. Self-transcendence (five questions, e.g., “According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, how do you think self-transcendence can be reached?”).

The teacher provided assistance if necessary, and then students recorded their own reflections on the worksheet for the following conversation and discussion, and will also be submitted as an individual record for data collection.

As mentioned, various positive intervention strategies were included as parts of the drills and practice. The meaning-oriented approach to education identifies key components of a meaningful life as well as practical guidelines for practice. Meaning consists of four fundamental components, PURE (purpose, understanding, responsibility, and enjoyment/evaluation) of a meaningful life (Wong, 2010b; Wong, 2012a; Wong et al., 2016), the existentially oriented ABCDE (Wong, 2010b) elements are essential in coping with adversity (acceptance, belief, commitment, discovery, and evaluation/enjoyment), as well as perspective change, gratitude exercise, or an attitude of self-transcendence and other related interventions (e.g. videos on YouTube “What would you do” and Blindness Awareness activity) were practiced within class activities. These skills and exercises of mindset were interwoven with the lesson processes as the meaning-oriented exercise to help students acquire the ability of positive intervention. With the communicative language teaching approach, students learned to reflect and express their personal experiences while discussing the CasMac meaning-oriented topics.

During the study, conducted from March to June 2020, the global pandemic COVID-19 had been spreading and causing casualties and unprecedented crizes that all mankind has to deal with. Discussion of related news and coping measures were also included within the topics of gratitude, acceptance, resilience, and self-transcendence. Research on PP2.0, or existential positive psychology, supported the idea that the dark side of human existence is essential to complete the circle of wholeness (Wong, 2019b), and it will provide a solid groundwork to build a meaningful and successful life by nurturing students the capabilities to face suffering and adversity.

Measures

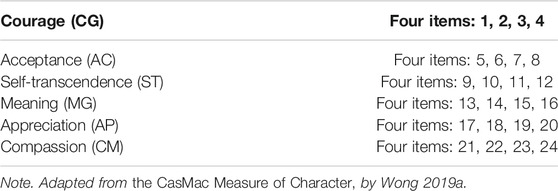

The CasMac Measure of Character has been developed by Wong (2019a). This instrument comprises 24 items which can be classified into six characteristics as subscales (see Table 2 and the appendix), including.

1. courage (four items, e.g., “I never let obstacles or oppositions prevent me from doing what really matters”),

2. acceptance (four items, e.g., “I accept my limitations”),

3. self-transcendence (four items, e.g., “My life is meaningful because I live for something greater than myself”),

4. meaning (four items, e.g., “I can find something meaningful or significant in everyday events”),

5. appreciation (four items, e.g., “My life is full of hardships and suffering, but I can still count my blessings”), and

compassion (four items, e.g., “I often feel the pain of another human being”).

Each subscale consisted of four items and each item was rated by participants on a seven-point Likert-type scale from one (strongly disagree) to seven (strongly agree) to indicate to what extent each item is characteristic of the participant. To calculate the final score, the scores of all 24 items were added. A high score meant the high performance of the characteristics.

Results

Through the analyses on data from CasMac Measure of Character (Wong, 2019a) at the beginning and the end of the semester and weekly learning sheets and journals, we found that students showed substantial learning outcomes on this MCPE class and reported their improved positive life attitudes as discussed in the following.

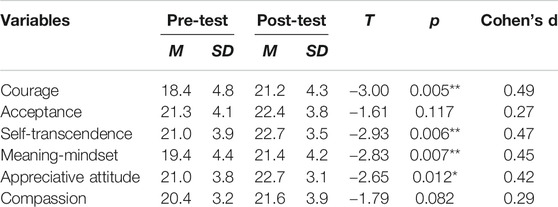

When it comes to the quantitative results, our interest was to determine whether there was statistical evidence to support our MCPE intervention as measured by the CasMac Measure of Character pre- and post-test. The data were analyzed with paired-sample t-test using SPSS 22.0. The results were shown in Table 3. The results showed that the overall mean CasMac score in the post-test (Mean = 5.5, SD = 1.2) was high than that of the pre-test (Mean = 5.1, SD = 1.4). Four of the six subscales (Courage, Self-Transcendence, Meaning-mindset, and Appreciative attitude) showed statistically significant differences (p < 0.05). These results suggested a significant effect of the CasMac intervention model. However, two subscales (Acceptance and Compassion) did not show a significant difference. The possible explanations will be discussed later in this paper.

The qualitative data were obtained from the students’ weekly learning sheets and journals. Upon reviewing each question, meaningful units were induced and organized according to the perspectives of the CasMac Model to examine students’ learning outcomes based on the seven topics. Table 4 shows examples of students’ answers and feedback from the weekly learning sheets. With the journal writings, the students reflected on the lessons regularly. They reported that this course helped them gain better understanding of meaning in their daily life. The students also reported that the course offered them a different way of reacting to daily events and reacting in a better manner. It helped them reflect on how to react at the moment of hardship and difficulties that they had encountered or would encounter in the future. They also showed a willingness to advance and challenge themselves by exerting their capabilities on meaningful goals and a positive attitude toward challenges and adversities. The qualitative data from the weekly learning sheets and journals also showed that students accepted that there are positive and negative realities in life, and they can face the negative life events with a more positive attitude.

Both the quantitative results of CasMac Measure of Character and the qualitative data from the weekly learning sheets and journals showed positive effects of applying the CasMac model and integrating meaning-centered positive education (MCPE) and the second wave positive psychology (PP2.0) into a university English class.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to form an original protocol and to apply Wong’s CasMac model in a university English speaking class. The researchers remain constant awareness, attention, and reflection during the process of study and the analysis of the results. MCPE based on PP2.0, focuses on meaning-mindset, and striving toward mature happiness as well as building characters and virtues. The results showed significant differences in the Courage, Self-transcendence, Meaning-mindset, and Appreciative attitude in the subscales of CasMac Measure of Character, but no differences in the Acceptance and Compassion subscales. The insignificant differences are possibly due to the design of the lessons and the indigenous cultural background of the participants. The results give an insight into the design of the lesson content of all subscales, particularly that of Acceptance, and it could be further inspected and modified. On the other hand, in the eastern cultural background, Compassion tends to be widely discussed and practiced in education and daily lives; students are likely to have mature understandings and actions regarding compassion relatively.

Accordingly, mature happiness, considered a by-product of pursuing a meaningful life, can be observed from students’ feedback and results. Theoretically, the application of the CasMac model indicated that PP2.0 could positively report the promotion of life meaning, wellbeing, and mature happiness; practically, the intervention strategy shows benefit in curriculum design and teaching in a university classroom. As a psychological intervention in education, the study can contribute to work on the development of meaning-mindset on students of higher education backgrounds, with the help of approaching mature happiness. Particularly in the dark times of the COVID-19 pandemic, the reality of life shows how important it is in discovering meaning in life, building resilience, and healing capacities with meaning-centered approaches and interventions that could be at help for people in need.

Implications for the Implementation of the CasMac Model

The results of this study were of significance to the application of the CasMac model and the MCPE intervention strategies. Meaning-based education has been used in elementary classrooms (e.g., The D.R.E.A.M. program, Armstrong et al., 2019). This was the first attempt at a higher education level to implement meaning-centered positive education and to apply the CasMac model in a university English class. The results show the feasibility of integrating PP2.0 and MCPE in a university curriculum. Future studies may extend this sample to various institutions of education. Nonetheless, if the CasMac model is intended to be applied, it is necessary to modify the content to make it appropriate for the developmental levels of the students, e.g. primary and secondary school children. Furthermore, teachers themselves need to understand PP2.0, MCPE, and the CasMac model in order to be adaptive in applying the theory and model.

It is important to realize that the purpose of education is not merely to teach students how to acquire certain skills, but also to inspire and nurture the minds to prepare them for the upcoming challenges with positive attitudes and to develop a mindset ready to face both the bright and dark sides of the reality of life. Stemmed from PP2.0, MCPE offers perspectives to see both the positive and negative sides of life, and to understand the meaning within. The attempt of this research confirms the feasibility of using Wong’s CasMac model in higher education and it has innovative value and contribution in curriculum and other intervention programs in future studies.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study was helpful to understand the feasibility of integrating MCPE and PP2.0 into a university English speaking class, there are still some limitations. Firstly, this study adopted a one-group pretest-posttest design because the class in this study was limited to students with upper-intermediate English proficiency. Since there was only one class with such a level, finding a control group with the same English proficiency level was difficult and inapplicable. In order to support the effectiveness of the study, it is recommended to improve the experimental design of involving control group in the future. Secondly, convenience sampling may limit the generalizability of the results. Future studies may expand the samples and increase the randomization level of the sample if possible. Finally, this study was conducted in the context of Eastern culture and the participants of upper-intermediate English proficiency, the participants had no difficulties in understanding authentic English material and the philosophy. Direct application of the model used in this study may be difficult if implemented in students with less English proficiency or different cultures.

Conclusion

This study applied the CasMac model in MCPE and PP2.0 and developed a series of lessons to discuss and explore virtues, values, and meaning, which are regarded as essential inner resources in order to develop a good character, resilience, and well-being even in the worst circumstances, as well as building personal growth in overcoming the dark side of living reality in view of the difficult times. The result presented that the implementation of the CasMac model in a university English class was feasible to enhance students’ understanding of mature happiness and promoted their meanings in life. Students showed willingness to advance themselves by applying their capabilities to meaning-orientation goals in life and having a positive attitude toward challenges and adversities. Also, the recorded conversations with students showed general satisfaction and recommendation to other university students to take this elective course because of its uniqueness, inspiration, and usefulness.

Based on the results of this study, the program serves as a model program to be adopted in classroom teaching. MCPE is needed not only for students. The possibility of future implementation and studies can extend to other needed targets, such as the teachers and parents, or students of different backgrounds in other fields, or other groups who are in need of enhancing the meaning of life and mature happiness. Hence, this can also accumulate more applicability of MCPE and PP2.0. To sum up, all generations are facing unpredictable difficulties and frustrating challenges nowadays, the second wave positive psychology is exactly what the time needs with its pursuit of meaningful beliefs and values.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the National Kaohsiung Normal University and National Pingtung University of Science and Technology. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

CC was the research designer and implementer. SC was the advisor of this study and offered guidance and references. CC and SC were in charge of writing. CC, SC, and HW participated in the discussion and revision of the manuscript. CC was the corresponding author. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants and the university in the study for the support, and Dr. Tu, C. T. for the help and advice on statistical analysis, and all the reviewers whose suggestions and comments greatly helped improve and clarify this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.648311/full#supplementary-material

References

Armstrong, L. L., Desson, S., St. John, E., and Watt, E. (2019). The D.R.E.A.M. Program: Developing Resilience through Emotions, Attitudes, & Meaning (Gifted Edition) - a Second Wave Positive Psychology Approach. Counselling Psychol. Q. 32 (3), 307–332. doi:10.1080/09515070.2018.1559798

Batthyany, A., and Russo-Netzer, P. (2014). Meaning in Positive and Existential Psychology. New York, NY: Springer.

Becker, D., and Marecek, J. (2008). Positive Psychology. Theor. Psychol. 18, 591–604. doi:10.1177/0959354308093397

Blank, C. (2017). The Characteristics of a Positive Attitude. LiveStrong. Available at: https://www.livestrong.com/article/139801-the-characteristics-positive-attitude/.

Breitbart, W., and Poppito, S. R. (2014). Individual Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Treatment Manual. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/med/9780199837243.001.0001

Bretherton, R., and Ørner, R. J. (2004). “Positive Psychology and Psychotherapy: An Existential Approach,” in Positive Psychology in Practice. Editors P. A. Linley, and S. Joseph (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley), 420–430.

Brown, H. D. (1987). Principles of Language Learning and Teaching. 2nd Edition. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Cavanagh, G. F., and Moberg, D. J. (1999). The Virtue of Courage within the Organization. Res. Ethical Issues Organizations 1, 1–25.

Chang, E. C., Downey, C. A., Hirsch, J. K., and Lin, N. J. (2016). Positive Psychology in Racial and Ethnic Groups: Theory, Research, and Practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Chang, S. J., Chang, S. M., Wei, H. M., and Chiu, A. L. (2006). A Survey of the Overall Conditions, Characteristics and Difficulties of the Implementation of Life-Education in Universities and Colleges in Taiwan. Kaohsiung Normal Univ. J. 21, 1–24.

Chang, S. M. (2020). A Brief Discussion on the Promotional Features and Prospects of Life Education in Taiwan. Assoc. Res. Life Educ. NKNU Electron. J. 1, 6–10. Available at: http://www.nknu.edu.tw/∼edu/web/doc/Learning/publication-7/1.pdf.

Chang, S. M. (2006b). “Life and Death Education.” in Practical Thanatology. Editor C. Y. Lin (Taichung, Taiwan: Wagner), 2-1–2-40.

Chang, S. M. (2016). “Life Education in Taiwan: Holistic and Meaning-Centered Positive Education,” in Oral presentation at The 4th Round Table Meeting of Asia-Pacific Network for Holistic Education, Malaysia, 2016. Nov. 11-13Taylor’s University Lakeside Campus).

Chang, S. M. (2006a). Life-and-death Education Approach of Life Education: Research and Practice. Kaohsiung, Taiwan: FuhWen Press.

Chang, S. M., Tang, H. W., and Tu, C. T. (2017). A Study on the Attitudes and Needs toward Life Education of Kindergarten Parents in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, R. O. C.. Kaohsiung Normal Univ. J. 43, 1–30. doi:10.7060/KNUJ-ES

Chen, L. Y., and Lin, Y. T. (2006). “The Promotion of Life Education in Vocational Colleges – A Case of Wenzao Ursuline College of Languages,” in China University of Science and Technology (Chair), National Colleges “Liberal Pedagogy Seminar – the Theory and the Practice of Life Education” Forum Collection Taichung, Taiwan, 33–43.

Chen, L. Y. (2004). Current Development of Life Education in Taiwan. Monthly Rev. Philos. Cult. 31 (9), 21–46. doi:10.7065/2fMRPC.200409.0021

Chi, J. F. (2002). Discussion of Integrating Life Education into Business Education: A Case of Business Ethics. Available at: http://life.edu.tw/homepage/091/others/tech/008.doc.

Christopher, J. C., and Hickinbottom, S. (2008). Positive Psychology, Ethnocentrism, and the Disguised Ideology of Individualism. Theor. Psychol. 18, 563–589. doi:10.1177/0959354308093396

Christopher, J. C., Richardson, F. C., and Slife, B. D. (2008). Thinking through Positive Psychology. Theor. Psychol. 18, 555–561. doi:10.1177/0959354308093395

Davidson, R. J. (2002). “Toward a Biology of Positive Affect and Compassion,” in Visions of Compassion: Western Scientists and Tibetan Buddhists Examine Human Nature. Editors R. Davidson, and A. Harrington (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 107–130. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195130430.003.0006

Dezelic, M. S., and Ghanoum, G. (2016). Trauma Treatment – Healing the Whole Person: Meaning Centered Therapy and Trauma Treatment Foundational Phase - Work Manual. Miami, FL: Presence Press International.

Ellis, A. (1995). Changing Rational-Emotive Therapy (RET) to Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT). J. Rational-emot Cognitive-behav Ther. 13, 85–89. doi:10.1007/bf02354453

Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s Search for Meaning. Revised & updated ed. New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

Goetz, J. L., Keltner, D., and Simon-Thomas, E. (2010). Compassion: An Evolutionary Analysis and Empirical Review. Psychol. Bull. 136 (3), 351–374. doi:10.1037/a0018807

Gross, J. J., and Levenson, R. W. (1997). Hiding Feelings: the Acute Effects of Inhibiting Negative and Positive Emotion. J. Abnormal Psychol. 106 (1), 95–103. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.106.1.95

Guttman, D. (2008). Finding Meaning in Life, at Midlife and beyond: Wisdom and Spirit from Logotherapy. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Harris, R. (2008). The Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start Living. Boston, MA: Trumpeter.

Held, B. S. (2004). The Negative Side of Positive Psychology. J. Humanistic Psychol. 44, 9–46. doi:10.1177/0022167803259645

Held, B. S. (2002). The Tyranny of the Positive Attitude in America: Observation and Speculation. J. Clin. Psychol. 58, 965–991. doi:10.1002/jclp.10093

Ivtzan, I., Lomas, T., Hefferon, K., and Worth, P. (2015). Second Wave Positive Psychology: Embracing the Dark Side of Life. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315740010

Jong, E. M., Ziegler, N., and Schippers, M. C. (2020). From Shattered Goals to Meaning in Life: Life Crafting in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 11. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577708/full.

Kristjánsson, K. (2012). Positive Psychology and Positive Education: Old Wine in New Bottles?. Educ. Psychol. 47, 86–105. doi:10.1080/00461520.2011.610678

Lomas, T. (2017). A Meditation on Boredom: Re-appraising its Value through Introspective Phenomenology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 14 (1), 1–22. doi:10.1080/14780887.2016.1205695

Lomas, T. (2019). Anger as a Moral Emotion: A “bird's Eye” Systematic Review. Counselling Psychol. Q. 32 (3-4), 341–395. doi:10.1080/09515070.2019.1589421

Lomas, T., and Ivtzan, I. (2016). Second Wave Positive Psychology: Exploring the Positive-Negative Dialectics of Wellbeing. J. Happiness Stud. 17, 1753–1768. doi:10.1007/s10902-015-9668-y

Lomas, T. (2018). The Quiet Virtues of Sadness: A Selective Theoretical and Interpretative Appreciation of its Potential Contribution to Wellbeing. New Ideas Psychol. 49, 18–26. doi:10.1016/j.newideapsych.2018.01.002

Lopez, S. J., Pedrotti, J. T., and Snyder, C. R. (2021). Positive Psychology: The Scientific and Practical Explorations of Human Strengths. 3rd Edition. Washington, DC: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Lukin, K. (2019). Toxic Positivity: Don’t Always Look on the Bright Side. Psychol. Today. Available at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-man-cave/201908/toxic-positivity-dont-always-look-the-bright-side.

Lyubomirsky, S., Sousa, L., and Dickerhoof, R. (2006). The Costs and Benefits of Writing, Talking, and Thinking about Life's Triumphs and Defeats. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 90 (4), 692–708. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.90.4.692

Martin, J. (2006). Self Research in Educational Psychology: A Cautionary Tale of Positive Psychology in Action. J. Psychol. 140, 307–316. doi:10.3200/jrlp.140.4.307-316

Maslow, A. H. (1971). “Blockchain challenges and opportunities: A survey, ” in Self-Actualizing and Beyond. New York:Penguin Compass, Chap. 1, 41.

McKay, M., and West, A. (2016). Emotion Efficacy Therapy: A Brief, Exposure-Based Treatment for Emotion Regulation Integrating ACT and DBT. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.

McMahan, E. A., Choi, I., Kwon, Y., Choi, J., Fuller, J., and Josh, P. (2015). Some Implications of Believing that Happiness Involves the Absence of Pain: Negative Hedonic Beliefs Exacerbate the Effects of Stress on Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 17 (6), 2569–2593. doi:10.1007/s10902-015-9707-8

Niemiec, R. M. (2018). Character Strengths Interventions. [PowerPoint Presentation]. Available at: https://pubengine2.s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/preview/99.110005/9781616764920_preview.pdf.

Norem, J. K., and Chang, E. C. (2002). The Positive Psychology of Negative Thinking. J. Clin. Psychol. 58 (9), 993–1001. doi:10.1002/jclp.10094

Nunan, D. (1991). Communicative Tasks and the Language Curriculum. TESOL Q. 25 (2), 279–295. doi:10.2307/3587464

Parks, A. C., and Biswas-Diener, R. (2013). “Positive Interventions: Past, Present, and Future,” in Mindfulness, Acceptance, and Positive Psychology: The Seven Foundations of Well-Being. Editors T. Kashdan, and J. Ciarrochi (Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications), 140–165.

Peterson, C., and Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Wong, P. T. P. in The Human Quest for Meaning: Theories, Research, and Applications. 2nd Edition (New York: Routledge Publishers).

Putnam, D. (1997). Psychological Courage. Philos. Psychiatry Psychol. 4, 1–11. doi:10.1353/ppp.1997.0008

Quintero, S., and Long, J. (2019). Toxic Positivity: The Dark Side of Positive Vibes. The Psychol. Group. Available at: https://thepsychologygroup.com/toxic-positivity/.

Richards, J. C. (2006). Communicative Language Teaching Today. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Richards, J. C., and Rodgers, T. S. (1986). Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching: A Description and Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ryff, C. D., and Singer, B. H. (2008). Know Thyself and Become what You Are: A Eudaimonic Approach to Psychological Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 9, 13–39. doi:10.1007/s10902-006-9019-0

Sample, I. (2003). How to Be Happy. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2003/nov/19/1.

Schneider, K. J. (2011). Toward a Humanistic Positive Psychology: Why Can’t We Just Get along?. Existential Anal. 22 (1), 32–38.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Seligman, M. E. P., and Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive Psychology: An Introduction. Am. Psychol. 55, 5–14. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.55.1.5

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being. New York, NY: Free Press.

Sheldon, K. M., and Lyubomirsky, S. (2006). How to Increase and Sustain Positive Emotion: The Effects of Expressing Gratitude and Visualizing Best Possible Selves. J. Positive Psychol. 1 (2), 73–82. doi:10.1080/17439760500510676

Steger, M. F., Sheline, K., Merriman, L., and Kashdan, T. B. (2013). “Using the Science of Meaning to Invigorate Values-Congruent, Purpose-Driven Action,” in Mindfulness, Acceptance, and Positive Psychology: The Seven Foundations of Well-Being. Editors T. Kashdan, and J. Ciarrochi (Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications), 240–266.

Sun, H. C. (2009). Challenges and Visions: Life Education in Taiwan. Curriculum Instruction Q. 12 (3), 1–25.

Sun, H. C. (2015). The Construction of Core Competencies of Life Education and the Development of General Curriculum Guidelines of 12-Year Basic Education. J. Edu. Res. 251, 48–72. doi:10.3966/168063602015030251004

Taheny, M. (2015). Living Existential Positive Psychology. New Existentialists: Saybrook University. Available at: http://www.saybrook.edu/newexistentialists/posts/05-04-15/.

Taylor, E. (2001). Positive Psychology and Humanistic Psychology: A Reply to Seligman. J. Humanistic Psychol. 41, 13–29. doi:10.1177/0022167801411003

Taylor, S. E., and Brown, J. D. (1988). Illusion and Well-Being: A Social Psychological Perspective on Mental Health. Psychol. Bull. 103 (2), 193–210. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.103.2.193

Trzebiński, J., Cabański, M., and Czarnecka, J. (2020). Reaction to the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Influence of Meaning in Life, Life Satisfaction, and Assumptions on World Orderliness and Positivity. J. Loss Trauma 25 (3), 1–14. doi:10.1080/15325024.2020.1765098

Van Tongeren, D. R., and Van Tongeren, S. A. S. (2020). The Courage to Suffer: A New Clinical Framework for Life’s Greatest Crises. West Conshocken, PA: Templeton Press.

Waterman, A. S. (2013). The Humanistic Psychology-Positive Psychology divide: Contrasts in Philosophical Foundations. Am. Psychol. 68, 124–133. doi:10.1037/a0032168

Williams, J. C., and Lynn, S. J. (2011). Acceptance: An Historical and Conceptual Review. Imagin Cogn. Pers 30, 5–56. doi:10.2190/IC.30.1

Wong, P. T. P. (2013a). “A Meaning-Centered Approach to Addiction and Recovery,” in The Positive Psychology of Meaning and Addiction Recovery. Editors L. C. J. Wong, G. R. Thompson, and P. T. P. Wong (Birmingham, AL: Purpose Research).

Wong, P. T. P., and Bowers, V. (2018). “Mature Happiness and Global Wellbeing in Difficult Times,” in Scientific Concepts behind Happiness, Kindness, and Empathy in Contemporary Society. Editor N. R. Silton (Hershey, PA: IGI Global), 112–134.

Wong, P. T. P. (2009). “Chinese Positive Psychology,” in Encyclopedia of Positive Psychology. Editor S. Lopez (Oxford: Blackwell).

Wong, P. T. P. (2013b). “Cross-cultural Positive Psychology,” in Encyclopedia of Cross-Cultural Psychology. Editor K. Keith (Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell Publishers).

Wong, P. T. P. (2020b). Existential Positive Psychology and Integrative Meaning Therapy. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 32, 565–578. doi:10.1080/09540261.2020.1814703

Wong, P. T. P. (2021a). Existential Positive Psychology (PP2.0) and Global Wellbeing: Why it Is Necessary during the Age of COVID-19. IJEPP 10 (1), 1–16.

Wong, P. T. P. (2016d). “From Viktor Frankl’s Logotherapy to the Four Defining Characteristics of Self-Transcendence,” in Paper presented at the research working group meeting for Virtue, Happiness, and the Meaning of Life Project, Columbia, SC(Funded by the John Templeton Foundation).

Wong, P. T. P. (2016a). “Integrative Meaning Therapy: From Logotherapy to Existential Positive Interventions,” in Clinical Perspectives on Meaning: Positive and Existential Psychotherapy. Editors P. Russo-Netzer, S. E. Schulenberg, and A. Batthyány (New York, NY: Springer).

Wong, P. T. P., Ivtzan, I., and Lomas, T. (2016). “Good Work: The Meaning-Centered Approach (MCA),” in The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Positivity and Strengths Based Approaches at Work. Editors M. Steger, and L. Oats (West Sussex, UK: Wiley Blackwell).

Wong, P. T. P. (2020a). Made for Resilience and Happiness: Effective Coping with COVID-19 According to Viktor E. Frankl and Paul T. P. Wong. INPM Press.

Wong, P. T. P. (2016b). Mapping the Contour of Second Wave Positive Psychology (PP2.0). Positive Living Newsl. Available at: http://www.drpaulwong.com/inpm-presidents-report-september-2016/.

Wong, P. T. P. (2014b). “Meaning in Life,” in Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Editor A. C. Michalos (New York, NY: Springer), 3894–3898. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_1755

Wong, P. T. P. (2010b). Meaning Therapy: An Integrative and Positive Existential Psychotherapy. J. Contemp. Psychother 40 (2), 85–93. doi:10.1007/s10879-009-9132-6

Wong, P. T. P. (2017a). Meaning-centered Approach to Research and Therapy, Second Wave Positive Psychology, and the Future of Humanistic Psychology. Humanistic Psychol. 45, 207–216. doi:10.1037/hum0000062

Wong, P. T. P. (2017b). Meaning-centered Positive Education. Keynote presented at the National Kaohsiung Normal University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan. Available at: http://www.drpaulwong.com/meaning-centered-positive-education/.

Wong, P. T. P. (2016c). “Meaning-seeking, Self-Transcendence, and Well-Being,” in Logotherapy and Existential Analysis: Proceedings of the Viktor Frankl Institute. Editor A. Batthyany (Cham, Switzerland: Springer), Vol. 1, 311–321. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-29424-7_27

Wong, P. T. P., Pattakos, A., and Arslan, G. (2020). The Role of Responsibility in Wellbeing & Public Policy in the Age of COVID-19 [Abstract]. Available at: http://www.drpaulwong.com/the-role-of-responsibility-in-wellbeing-public-policy-in-the-age-of-covid-19.

Wong, P. T. P. (2007). Perils and Promises in the Pursuit of Happiness. PsycCRITIQUES 52 (49). doi:10.1037/a0010040

Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive Psychology 2.0: Towards a Balanced Interactive Model of the Good Life. Can. Psychology/Psychologie canadienne 52 (2), 69–81. doi:10.1037/a0022511

Wong, P. T. P., and Roy, S. (2017). “Critique of Positive Psychology and Positive Interventions,” in The Routledge International Handbook of Critical Positive Psychology. Editors N. J. L. Brown, T. Lomas, and F. J. Eiroa-Orosa (London, UK: Routledge).

Wong, P. T. P. (2019b). Second Wave Positive Psychology's (PP 2.0) Contribution to Counselling Psychology. Counselling Psychol. Q. 32, 275–284. doi:10.1080/09515070.2019.1671320

Wong, P. T. P. (2006). The Nature and Practice of Compassion: Integrating Western and Eastern Positive Psychologies. PsycCRITIQUES 51 (25). doi:10.1037/a0002884

Wong, P. T. P. (2019a). The Positive Education of Character Building: CasMac. Dr. Paul T. P. Wong. Available at: http://www.drpaulwong.com/the-positive-education-of-character-building-casmac/.

Wong, P. T. P. (2004). The Wisdom of Positive Acceptance. Available at http://www.meaning.ca/archives/presidents_columns/pres_col_feb_2004_positive-acceptance.htm.

Wong, P. T. P. (2021b). Two Different Models of Human Flourishing: Seligman’s PERMA Model versus Wong’s Self-Transcendence Model. Dr. Paul T. P. Wong. Available at: http://www.drpaulwong.com/two-different-models-of-human-flourishing-seligmans-perma-model-versus-wongs-self-transcendence-model/.

Wong, P. T. P. (2014a). “Viktor Frankl's Meaning-Seeking Model and Positive Psychology,” in Meaning in Existential and Positive Psychology. Editors A. Batthyany, and P. Russo-Netzer (New York, NY: Springer), 149–184. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-0308-5_10

Wong, P. T. P. (2010a). What Is Existential Positive Psychology?. Int. J. Existential Psychol. Psychotherapy 3, 1–10. Available at: http://www.drpaulwong.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/what-is-existential-positive-psychology.pdf.

Wong, P. T. P. (2012b). What Is the Meaning Mindset?. Int. J. Existential Psychol. Psychotherapy 4 (1), 1–3.

Wong, P. T. P., and Wong, L. C. J. (2012). “A Meaning-Centered Approach to Building Youth Resilience,” in The Human Quest for Meaning: Theories, Research, and Applications. Editor P. T. P. Wong. 2nd Edn. (New York, NY: Routledge), 585–617. Available at: http://www.drpaulwong.com/documents/HQM2-chapter27.pdf.

Wong, P. T., and Weiner, B. (1981). When People Ask “why” Questions, and the Heuristics of Attributional Search. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 40, 650–663. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.40.4.650Available at: http://www.drpaulwong.com/documents/when-people-ask-why-questions.pd

Keywords: meaning-centered positive education, second wave positive psychology, curriculum design, CasMac model, mature happiness, english language teaching (ELT)

Citation: Chen C-H, Chang S-M and Wu H-M (2021) Discovering and Approaching Mature Happiness: The Implementation of the CasMac Model in a University English Class. Front. Educ. 6:648311. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.648311

Received: 31 December 2020; Accepted: 10 May 2021;

Published: 02 June 2021.

Edited by:

Paul T. P. Wong, Trent University, CanadaReviewed by:

Laura Armstrong, Saint Paul University, CanadaArthur Cheuk-Man Li, The University of Hong Kong, China

Copyright © 2021 Chen, Chang and Wu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chih-Hong Chen, YW5kcmV3Y2hjQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Chih-Hong Chen

Chih-Hong Chen Shu-Mei Chang

Shu-Mei Chang Huei-Min Wu

Huei-Min Wu