94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 18 May 2021

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.642367

This article is part of the Research TopicAdvances in Youth Bullying ResearchView all 14 articles

Relatively little scholarly work addresses parental experiences with bullying in the United States. This lack of understanding about parental perceptions of bullying is a gap in both the scholarly research and the development of effective bullying prevention programming. This paper presents data from responses to a series of open-ended questions about perceptions of and experiences with bullying from 50 parents in a southeastern state. Parents self-reported their level of concern about bullying, their perceptions of why bullying occurs and the extent of bullying at their school, and their communication strategies with their children about bullying. Findings demonstrate that most parents 1) view bullying as problematic and are somewhat fearful of bullying affecting their child, 2) are confident their child is not telling them about all bullying situations they experience, and 3) are more than willing to approach school administrators when their children are victims of bullying. The findings suggest that parents remain concerned about bullying and its problematic nature, and efforts to encourage children to report bullying to adults are not entirely effective. Consequently, bullying prevention training will benefit from greater parental involvement with (and reinforcement of) bullying prevention strategies learned by children at school. Implications for policy and research are also discussed.

Despite decades of research around the topic, bullying remains a serious problem for students in school. Olweus (1973) defines bullying as behavior that occurs repeatedly, is intended to cause harm, and involves a power imbalance. When bullying occurs, parents play a pivotal role in how it is handled and supportive parents reduce their children’s likelihood of being both a perpetrator and victim of bullying (Baldry & Farrington 2005; Wang et al., 2009).

The vast majority of studies around bullying examine bullying from the child’s perspective, and generally ignore the perceptions of parents. Thus, despite the hundreds of scholarly articles around bullying, limited research has examined parents’ perception of bullying and the conversations they have with children concerning bullying involvement and victimization. In this study, we seek to partially fill that gap by using qualitative interviews with 50 parents in a southeastern state to examine parent perceptions of bullying and how they discuss bullying with their children. We also explore how fearful parents are of their child being victimized by bullying, their opinion of why bullying occurs in school, and the advice they give their children concerning bullying.

Bullying is behavior that occurs repeatedly, is intended to cause harm, and involves a power imbalance (Olweus, 1973). Bullying can occur through physical aggression, gestures, rumors, or exclusion. The imbalance of power may appear as a difference in physical strength, whether real or perceived, between the aggressor and victim, the number of persons against the victim, or the inability of the victim to confront forms of relational aggression such as rumors or exclusion (Olweus, 1997).

In 1998, one in three (29.9%) students (N = 15,686) in grades 6 through 10 were involved with bullying, including those who reported being a bully (13%), a victim (10.6%) or both a bully and victim (6.3%; Nansel et al., 2001). In the 2015–2016 school year, a nationally representative study of 2,092 public schools in the United States found 21% of students between the ages of 12 and 18 were bullied at school (Musu-Gillette et al., 2018). Bullying prevalence is well documented, particularly during middle school and into early high school (Hymel & Swearer, 2015; Wang et al., 2020). Findings from the Bureau of Justice Statistics lend credence to this occurrence; during the 2017–2018 school year, a greater percentage of middle schools (28%) reported bullying than high schools (16%), combined schools (16%), or primary schools 9%; Wang et al., 2020).

In any year, more than one in 10 schools reported that bullying occurred at least once per week (Musu-Gillette et al., 2018). Of the 5,064 teachers and support professionals from the National Education Association who were surveyed, more than three in five (62%) reported seeing bullying two or more times in the previous month and two out of five (41%) reported bullying at least once in the last week (Bradshaw et al., 2013). Bullying is a pervasive issue that affects youth of all ages, races, genders, and backgrounds; however, it is unclear to what extent youth are bullied or bully others on any given day. Some of the variation in prevalence may be attributed to the operationalization of bullying, measurement criteria, or memory distortions of bullying experiences (Jimerson et al., 2009).

There are four commonly recognized types of bullying. These include physical, verbal, relational (social), and cyber. These types can also be categorized as direct or indirect forms of aggression. Physical bullying occurs face-to-face and may include behaviors such as hitting or kicking. Verbal bullying involves threats or name-calling. Relational bullying is indirect and may include social exclusion, rumors, or peer rejection (Ericson, 2001). Finally, cyberbullying is defined as intentional and repeated harm that occurs through an electronic medium (Patchin & Hinduja, 2006).

Bullying takes a variety of forms including name calling, threats, rumors, exclusion, disrespect, or being made fun of and bullying prevalence varies by type of bullying (Patchin & Hinduja, 2006). Some research has found that more youth experience verbal and relational bullying than physical or cyberbullying (Williams & Guerra, 2007; Wang et al., 2009). Traditional bullying and cyber bullying are highly correlated (Modecki et al., 2014), and youth involved in traditional bullying are at a greater risk of being involved in cyberbullying than their peers (Kowalski et al., 2012).

Youth may be involved in several types of bullying. A recent meta-analysis of 80 studies found an average prevalence rate of 35% for traditional forms of bullying and 15% for cyberbullying (Modecki et al., 2014). Because bullying is influenced by a number of factors and can occur in several contexts, it is important to consider not only the locations and reasons why it occurs, but to assess all persons who are involved. The input from children, parents, and teachers is necessary to fully understand the extent to which youth experience bullying, whether as a victim or aggressor.

Bullying has been shown to have both short-term and long-term consequences including adverse psychological and health outcomes. Data from 1,118 children between ages 9 and 11 was collected to determine whether bullying victims experience negative health effects after their experience or whether negative health effects occur prior to a youth’s victimization. Fekkes, Pijpers, Fredriks et al. (2006)’s study found support for both relationships. They determined that youth who were often bullied at the beginning of the school year were likely to develop adverse health effects (including anxiety and depression) by the end of the school year while youth who already experienced anxiety and depression at the beginning of the school year were also at an increased risk of being victimized (Fekkes, Pijpers, Fredriks et al., 2006). A systemic review of previous bullying research conducted by Moore et al. (2017) also explored health and psychological effects of bullying. In their sample of 153 peer reviewed articles published before February 2015, they found significant associations between bullying victimization and mental health disorders, such as anxiety and depression, suicide ideation and suicide behavior. Associations between physical health and bullying victimization were also uncovered. Negative physical health consequences of bullying victimization included problems sleeping, stomach aches, dizziness, back pain, and obesity. The findings from the review also suggest there was an association between alcohol use and tobacco use for those youth who experienced bullying frequently (Moore et al., 2017). Given the serious consequences that can result from bullying victimization, it is important for parents to get involved and identify if their child has been bullied.

Only recently has research begun to recognize the unique position of parents to address bullying. Parents act not only as a protective factor (Jeynes, 2008; Lereya et al., 2013), but as a resource, to offer strategies to prevent bullying. Parent involvement is also associated with lower rates of bullying (Jeynes, 2008). Bullying interventions are needed at home and in school and must involve parents, school staff, and children. Improvements in classroom management and supervision of outdoor areas can decrease bullying (Ttofi & Farrington, 2011). In the 2015–2016 school year, three in four (76%) public schools reported teachers and teaching aides were given training to recognize bullying behavior (Musu-Gillette et al., 2018). In addition to creative effective trainings for teachers and other school staff, parents should also be involved. Parental involvement has been recognized as one of the key elements needed to create effective anti-bullying programs in schools (Ttofi & Farrington, 2011) and some parents have reported wanting to be more involved in responding to their child’s bullying experience at school (Harcourt, Green et al., 2015). The creation of effective programs to prevent bullying though is complicated, as many children do not report bullying (Unnever & Cornell, 2004).

Children do not report bullying for a variety of reasons. Children may not report as a result of the type of bullying, the severity of the behavior, characteristics of the victim and bully, social circumstances, and family dynamics. Children who perceived that the school or their teacher would not take bullying seriously were also less likely to tell someone (Unnever & Cornell, 2004). Some children have reported fearing the bully or peer rejection, blaming themselves for their victimization, or being hesitant to affect the relationship with the bully, particularly when it is a friend. Youth also report fearing that adults would tell the principal or believing that telling an adult would make the bullying worse (Mishna, Pepler et al., 2006). Children were willing to tell an adult if they believed the bullying was serious (Mishna et al., 2006), if it occurred frequently (Unnever & Cornell, 2004; Musu-Gillette et al., 2018), or if they perceived bullying would be taken seriously (Cortes & Kochenderfer-Ladd, 2014).

When children report bullying, they are more likely to tell a parent than a teacher (Bentley & Li, 1996; Fekkes, Pijpers, & Verloove-Vanhorick, 2005). Bentley and Li’s (1996) study of 394 students in grades 4 to 6 found students, in general, were more likely to tell someone at home than a teacher about bullying. However, children who were victims of bullying were more likely than their peers to tell a teacher. Despite the number of children who would tell someone at home though, children perceived telling a teacher was more likely to help improve the bullying situation than if they told a parent (Bentley & Li, 1996).

Teachers, school administrators, and parents have expressed difficulty in fully understanding bullying situations, particularly when their definition of bullying do not match the situation (Mishna, Pepler et al., 2006). Findings from Sawyer et al. (2011) revealed parents who were unaware of bullying were surprised to learn their child experienced bullying, especially when they had many friends. However, bullying among friends is often commonplace (Mishna, Wiener et al., 2008). Parents may find it difficult to understand the extent of bullying when it comes to friendships between children (Mishna, Pepler et al., 2006). Furthermore, some parents normalize bullying as part of growing up (Sawyer et al., 2011) or something that is inevitable (Mishna, Sanders et al., 2020). This could make children less likely to want to report because being a victim of bullying may not be taken seriously, a concern raised by children in several studies (Unnever & Cornell, 2004; Cortes & Kochenderfer-Ladd, 2014).

Parents, teachers, and students have identified differences as one of the key reasons why bullying happens (Compton et al., 2014; Mishna, Sanders et al., 2020). Parents offered qualitative accounts of these differences in Mishna, Sanders et al.’s (2020) study with specific mentions of gender, race, class, religion, sexual orientation, appearance, mannerisms, academic abilities, and athletic abilities. These examples are all indicative of bias-based bullying, in which a person is bullied because of a particular stigma or social identity (Mulvey et al., 2018). Other reasons parents believe bullying occurs include a quest for power or status by the bully, peer pressure, and anger or frustration as a result of the bullying perpetrator having previously experienced bullying victimization (Compton et al., 2014). The anonymous nature of cyberbullying also appears to be a motivator for that form of bullying as well (Hoff & Mitchell, 2009; Compton et al., 2014; Monks et al., 2016).

Parents may feel an array of negative emotions, such as anger and frustration, or feelings of concern or worry about the negative effects bullying victimization can have for their children (Sawyer et al., 2011). Nevertheless, limited research has addressed whether parents are fearful of their child being bullied. In the only previous study of parental fear of bullying of which we are aware, Stives et al. (2019) assessed the extent to which parents were fearful of their child becoming a victim of bullying. In Stives et al.’s (2019) study of 54 parents, they found parents were evenly divided on whether they were fearful of their child becoming a victim. Nearly half of the parents (46.6%) reported they were not fearful of their child becoming a victim, while 26% reported they somewhat fearful and 22% reported they were very fearful. Parents who were not fearful for their child offered three main reasons; the size of the school, their belief that there was no bullying at their child’s school, and their confidence in their child’s ability to handle bullying situations on their own. When parents did express fear of victimization, concerns were related to the belief their child was different based on particular characteristics or appearance (Stives et al., 2019).

Telling someone about bullying is the first step necessary to address the situation. Positive parenting behavior has been associated with protective effects for children. When children perceive their relationship with their parent is warm/loving, their parent is understanding, and their parent is sympathetic to their problems and willing to help, this perception has a protective effect (Wang et al., 2009; Lereya et al., 2013). Higher levels of parental support are associated with lower rates of bullying involvement and bullying victimization (Baldry & Farrington, 2005; Wang et al., 2009). Having parents with an authoritative style of parenting is also negatively associated with being a victim or a bully (Baldry & Farrington, 2005). In addition to acting as a protective factor, when children are bullied, parents can offer a variety of strategies to address their situation.

One of the most common strategies parents tell their children is to get help from an adult when they are bullied (Cooper & Nickerson, 2013; Offrey & Rinaldi, 2014; Stives et al., 2019). Cooper and Nickerson (2013) reported that parents were most likely to tell their child to get help from a parent (98%) and teacher (97%). Strategies can be classified as either problem-solving (i.e., help-seeking; Craig et al., 2007; Harcourt, Jasperse et al., 2014; Offrey & Rinaldi, 2014), or emotion-focused (Harcourt, Jasperse et al., 2014). Problem-solving behaviors directly address the incidence of bullying, while emotion-focused strategies help the victim cope with their experience, rather than focus on the bully.

Parents commonly suggest avoidance strategies when children are faced with a bully (Cooper & Nickerson, 2013; Stives et al., 2019). These avoidance strategies include avoiding the bully or pretending nothing happened (Stevens et al., 2002). The extent to which these strategies are suggested varies. Using hypothetical bullying scenarios, Stevens et al. (2002) found parents of victimized children were more likely to suggest avoidance strategies than parents of children who bully. Thus, parents may offer different strategies depending on their perspective of bullying and its effects. During interviews with 20 parents, Sawyer et al. (2011) found parents also teach pro-social strategies to their children that focus on healthy relationships and improving a child’s self-esteem. Parents gave assurances to children and some enrolled their children in extracurricular activities to expand their social network.

Some parents suggest a more direct approach to handle the bullying situation. Parents are divided on whether or not to tell their child to retaliate for bullying. In Cooper and Nickson’s (2013) study, 42.3% told their child to fight back, while another 44.1% said to never fight back. Some parents do support fighting back, particularly when nothing else has worked (Sawyer et al., 2011). Other parents take a more hands-on approach when it comes to bullying including contacting the parent of the other child (Cooper and Nickerson, 2013), a higher authority such as the principal (Stives et al., 2019), or taking serious actions including transferring their child to a different class or school, contacting the board of trustees, a higher commission, or involving the police (Harcourt, Green et al., 2015).

The preceding literature review has suggested that a wide variety of studies examine the predictors, types, and consequences of bullying. Another growing body of research has also examined why children do not report bullying to adults. Nevertheless, the vast majority of studies around bullying examine bullying from the child’s perspective, and generally ignore the perceptions of parents. We believe this is an important oversight in the literature and attempt to partially fill that gap with this research.

A wide variety of topics thus remain open for exploration from the parent’s perspective. Limited research asks parents about their perceptions of whether or not bullying is problematic, how fearful they are of their child experiencing bullying victimization, or what types of strategies parents give to their children to cope with bullying victimization. Additionally, no research of which we are aware asks parents whether they believe their own children are honest with them about the child’s bullying experience. Using data from 50 parents of middle and high school children in a southeastern state, we begin to fill these gaps by addressing the following research questions:

1. Are parents fearful of their children being bullied at school?

2. Do parents perceive bullying as problematic? If so, how big a problem is it?

3. Do parents believe their children are reporting all their bullying experiences?

4. Why do parents feel bullying occurs?

The data analyzed in this article were collected in the fall of 2017 as part of a larger project funded by the National Science Foundation that examined bullying among middle and high school students. The overall objective of the research was to investigate the use of robots as intermediaries to gather sensitive information from children.

After obtaining approval from the Mississippi State University institutional review board, we recruited the child participants from 1) the local high school during lunch and 2) a database of children who had volunteered to be contacted to participate in research at the university that was maintained by one of the members of the research team. On the day of the child’s interview, the child and their parent were met by a researcher as they entered the lab. The researcher explained the purpose of the study to the child and their parent, obtained parental consent and assent from the child, then escorted the child to a private room for their interview.

The researcher then returned to the child’s parent in the waiting area and provided them with a self-report questionnaire that asked the parent questions about their child’s bullying experiences (and their own responses to their child’s bullying experiences). The survey instrument was modeled after Sawyer et al. (2011) and included closed and open-ended questions. The responses to the open-ended questions on that survey provide the data for this study and are discussed in detail below. If a parent had more than one child participating in the study, he or she was asked to complete a survey for each child. Thus, if a parent had three children participating, they completed three separate surveys.

Of the 56 parents who were asked to complete a survey for their child, only six declined to participate. Thus, the response rate for this study was 89.3%. A total of 50 parents provided data for this study. In every situation, only one parent provided transportation for their child to the research site, so that was the parent that provided data for this study.

The demographics of the parents are reported in Table 1. Of the 50 parents who responded to the survey, the vast majority (92.0) were female. Parents were generally evenly split along racial lines. Approximately half (46%) were White, 25 (50%) were Black, and two respondents described themselves as other than Black or White. Parents were also evenly distributed across age categories, with the youngest parent being 32 and the oldest being 58 years old. Half of the parents were married (50%) and more than one in three parents (33.9%) had more than two children in their household. Parents were also evenly split across household income categories with the largest proportion (28.6%) having a household income between $25,000 and $49,999 per year.

In this study, we examined open-ended responses to self-report questions designed to measure parental discussions of bullying with their children. The self-report questionnaire asked some demographic questions and then asked a number of open-ended questions designed to examine parental perceptions of bullying and the methods through which they discuss bullying with their children. The questions were as follows:

1. How fearful are you of your child being bullied? Please explain.

2. What is your view about bullying? How problematic do you think it is?

3. Why do you think bullying happens at school? In general?

4. Do you think that your child is telling you about being bullied every time it happens? Or less often? Why?

5. In the past 12 months, has your child been involved in a bullying situation? If so, was the child a victim of bullying? Please tell us how you handled that situation.

6. If your child has not been involved in a bullying situation, what would you do if they were to experience bullying?

The responses to these open-ended questions were coded using an open axial-coding approach. Responses to questions five and six were combined into one variable to represent actual (for those parents whose child had been bullied) or likely (for those parents whose children had not been bullied) responses to bullying victimization. After coding the responses to each question into themes, we estimated frequencies of the themes for each question. A number of parents responded with more than one answer to one or more of the questions. The results of those analyses are presented below.

We asked parents, “How fearful are you of your child being bullied?” Responses to this question are provided in Table 2. Responses were relatively evenly distributed among the 41 parents who responded; nine parents did not respond to this question. More than one in four parents (28%) were coded as “not fearful,” suggesting that a substantial minority of the parents were not worried that their child would be bullied. By comparison, slightly more than half of the parents were concerned, to at least some degree, about their child being bullied. More than one in three (38%) parents were somewhat fearful and one in six (16%) of parents were very fearful of their child being bullied. Of those parents who said they were not fearful, some of the common themes were the child’s independence, the child’s ability to defend themselves, and open communication at home. Several parents simply responded they were not fearful. Parent 14 (P14) said, “No worries. My kids defend themselves very well”. Parent 7 (P7) also remarked, “Not very fearful, but I do ask them frequently about their day and also if anyone is bothering them”.

Parents who were fearful of their child being bullied mentioned specific themes, including the child’s personality, the harmful effects of bullying, or doubts in the ability of the school to address bullying. Parent 18 (P18) exemplifies the first theme about the child’s personality, “Because she's a quiet, shy child, I do worry about bullying. I also worry she may not open up and tell me if it was happening”. Parent 19 (P19) also expressed, “Very, my child is quiet and tends to hold things in”.

Two of the parents who were very fearful discussed the harmful effects of bullying. Parent 30 (P30) replied, “I am very fearful. My youngest child has an innate desire for acceptance and is very affectionate. I fear the effects rejection has on her socially and mentally. My oldest is very quiet and sensitive. I fear her being taken advantage of or hurt because she's perceived as weaker”.

Parent 31 (P31) agreed about the potential consequences of bullying and said they were, “Very fearful because it can lead to self-harm”.

Finally, some parents attributed their fear to the school’s inability to address bullying situations. Parent 41 (P41) replied, “He seems ok so far (he just started high school in August) but I have zero faith the school can handle it if something happens unless I create a shitstorm and force the issue, such as removing a bully from a class he/she haves with my kid”.

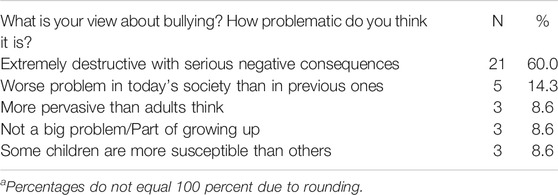

Next, we asked parents, “What is your view about bullying? How problematic do you think it is?” Responses were coded into five categories presented in Table 3. Parents gave a variety of responses but the most frequent (60%) response was that bullying was extremely destructive with serious negative consequences. Parents also reported it was a worse problem in today’s society than in previous ones (14.3%), it was more pervasive than adults think (8.6%), and some children are more susceptible than others (8.6%). Finally, some parents said it was not a big problem or it was part of growing up (8.6%).

TABLE 3. What is your view about bullying? How problematic do you think it is?a.

Responses of parents suggest that many are concerned about the prevalence of bullying and potentially harmful effects bullying can have on children. Parent 3 (P3) remarked, “I think it is extremely destructive to a child's social/mental wellbeing and can affect them for the rest of their life. In extreme cases, it can even be a cause of suicide or an attempt. Things seem so major to a child or teenager”.

Other parents commented on the serious consequences that can result from bullying including suicide. Parent 58 (P58) stated, “Bullying is wrong. And now the problem has gotten bad. Kids are killing themselves about this.” Parent 2 (P2) echoed these sentiments, “It's a big problem because everyone has feelings and if you mess with a person too long, you never know what going across their mind.”

Parents were then asked, “Why do you think bullying happens at school? In general?” Responses were coded into six categories that are included in Table 4. Despite the variety in responses, parents frequently (32.43%) stated bullying happens because youth model behaviors from home. Parent 37 (P37) stated, “Not sure but I believe a lot has to do with how a child is taught at home. Most children will do what they see other adults, in their daily life, do. How we as adults treat our neighbors, friends, or just the people we pass in the stores will affect our children”.

Parent 36 (P36) reiterated these sentiments and attributed a child’s behavior to what they experience at home. “I think children witness their parents being bullied in their homes and the children are bullied in their homes. They probably are growing up in a bullying environment in which they may perceive as normal”.

Parents also suggested bullying occurs in schools due to power differential and class systems among children (29.73%). Parent 3 (P3) said, “It occurs because social ranking is so very important to kids/teenagers, and when a child feels less than, they sometimes become a bully to make themselves feel more important or powerful”. Other parents simply replied power, or as Parent 17 (P17) remarked, “Because a person wants to have power over another person or a person wants what the other person haves”.

Other parents believed bullying happened as a result of poor adult supervision (16.2%), low self-esteem or a need for attention (10.8%), peer pressure (5.4%), and jealousy or building status (5.4%). Parents who mentioned a child’s self-esteem discussed how bullying was a way that person tries to make themselves feel better. By making someone else feel worse, they feel better. As Parent 25 (P25) said, “I believe bullying is an attempt for the bully to feel better about themselves by making someone else feel poorly about themselves”.

Parents were then asked “Does your child tell you about bullying every time it happens? If not, why not”. Responses to that question are presented in Table 5. Most (75%) parents believed their children did not always tell them about bullying. Of those who did not believe their child always told them, a variety of explanations were offered. Responses were coded into ten categories.

Of the parents who believed their child did not always talk to them about bullying, the most common reasons offered by parents were that their child was ashamed or embarrassed (15%), their child handles they bullying situation themselves (12.5%), or their child didn’t tell them because they were afraid of punishment if they told (10%). Parents who mentioned that their child may be ashamed or embarrassed talked about how their child likely feels when they are bullied or how they would feel if the parent got involved in the bullying situation. Parent 42 (P42) replied that their child did not always tell them about bullying because “…it is embarrassing to admit that you didn’t have the courage to confront a bully”. Parent 49 (P49) exemplified the belief that their child would handle a bullying situation themselves. As they said, “She has mentioned it in the past. We discuss it. She has been taught to fight very good and is an excellent marksman. I build her up and she knows she is a star and has worth. She is a Christian and we have discussed praying for our enemies. She is a happy child and understands that some people are simply pathetic so they turn into bullies. She has been prepared to protect herself if it comes to that. If she initiates any act, I will be her problem then. We believe in loving everyone and being open and honest. Over the years, she has actually befriended someone who once was a bully to her”.

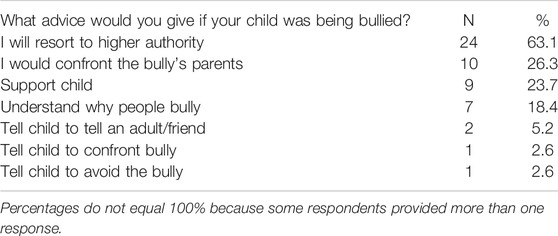

Finally, parents were asked: “What advice would you give if your child was being bullied?” Responses were then coded into seven categories which are presented in Table 6. The most frequent response (63.1%) was to resort to a higher authority. Nearly one in four (26.3%) parents also suggested they would confront the bully’s parents. Parents commonly mentioned talking to their child first to understand the situation. Parent 55 (P55) said they would, “Talk to them (my child) about the possible motives of the bully, explain that the bully is the one with the problem and talk to my child about how to respond. If the bullying was severe, I would address it with the school administration or possibly the bully's parents (if I know them)”.

TABLE 6. What advice would you give if your child was being bullied? N = 38. “Of the 38 parents who responded to the question,” before the most frequent result in the current sentence.

Another parent mentioned involving the school; Parent 36 (P36) said, “Talk to them, find out the situation, and go talk to the principal. Get the other parents involved.” Parent 15 (P15) also mentioned “speaking with the principal about bullying and recollected how they had done so in the past”.

I would go to the principal after discussing the situation with my child. This did happen when he was in sixth grade and I did have a long talk with the principal. As a result, there were some changes made to the school schedule for the following year.

Of the parents who would confront the bully’s parents, three mentioned how they would request a face-to-face meeting with the other parents to discuss the situation. Parent 11 (P11) said, “First thing I would do is find out who that child's parents are and contact them to let them know their child is bullying my child. It would not be a pleasant conversation. If it continued after that, the police would get involved”.

Parent 23 (P23) answered, “I would contact the aggressors parents as well as the school to have a conference”, and Parent 31 (P31) responded, “I would want to talk to the child's parents and see what exactly the problem is and how we can settle it”.

In this study, we used data from 50 parents in a southeastern state to examine parent perceptions of bullying and how they discuss bullying with their children. We also explored how fearful parents are of their child being victimized by bullying, their opinion of why bullying occurs in school, and also the advice they gave their children concerning bullying. Our study makes an important contribution to the literature around bullying because it is one of the first studies to examine parental fear of bullying victimization (Stives et al., 2019, for a notable exception) and parental concerns about the harmful impact of bullying. Additionally, this is one of a limited number of studies that examines the advice parents give their children when they have been bullied. Thus, this work contributes to a growing body of literature that considers the viewpoints of parents in the bullying literature in general (Sawyer et al., 2011; Cooper & Nickerson, 2013; Harcourt et al., 2014; Stives et al., 2019).

The findings from this study add to the bullying literature in a number of important ways. First, the findings uncovered here generally replicate those of Stives and her associates (2019) who examined fear of bullying among a sample of parents of elementary school children. The results presented here suggest that approximately half of the parents were are least somewhat fearful of their child being bullied at school and one in four parents were very fearful. Parents reported that their concerns stemmed from the personality of their child (which made them more likely to be a target for bullying), their lack of faith in the school administration to handle bullying, and their realization that bullying has serious harmful effects. Although half of the parents in this sample were not fearful of their child being bullied, the results presented here suggest that, no matter the age of the children, many parents still are concerned about their child being bullied at school, and feel that the school administration can do more to reduce bullying.

Next, the findings presented here reveal important differences between the advice parents of middle and high school children in this sample and parents of younger children in Stives et al. (2019) and Sawyer et al. (2011) give their children when they have been bullied. Parents in this sample were much more likely to be willing to directly intervene on their child’s behalf by meeting with the principal (by far the most common parental response) or confronting the bully’s parents (the second most common response). It appears, then, that parents of older children are much less willing to tolerate bullying of their children and much more willing to spearhead a solution than parents of younger children. This may result from frustration with years of telling their children to follow the school’s advice around bullying (e.g., tell a responsible adult, intervene when you see other children being bullied) yet their child is still suffering from bullying victimization. We did not ask parents “why” they would give their children the advice they would give them; future research should further explore the reasoning for this advice, particularly among parents of older children.

Another important finding from this study has to do with parents’ recognition of the negative impacts of bullying. Despite the belief among some members of the public that bullying is “not that serious,” with limited exception, parents in this sample acknowledged that bullying is extremely destructive, with serious negative consequences, and may be worse in the 21st century than ever before. In fact, more than one parent mentioned suicide as a potential outcome of bullying victimization. Additionally, most parents also acknowledged that their children likely were not telling them every time they experienced bullying, and thus parents rightly believed that bullying is even more pervasive than we like to acknowledge.

This study is also one of the first of which we are aware to ask parents whether they believe their child reports all of their bullying victimizations to them and, when their child does not report the bullying to the parent, why the parent believes this occurs. Parents that felt their child always reported their bullying victimization to them (about 25% of the sample) unanimously reported that they had an open line of communication with their children about everything, and thus their child felt comfortable telling them about each bullying incident that occurred. Those parents that reported their children withheld reports of bullying victimization felt they did so for a variety of reasons. The most common responses was that the child handled the bullying themselves; other common responses were that the child was too embarrassed to tell their parents every time they were bullied or they feared reprisal from the bully if they did tell their parent. The variety of responses presented by the parents to that question suggest that there are a plethora of reasons why children do not tell their parents about bullying and better understanding is needed, particularly among older children, for more effective bullying prevention.

Finally, this study is one of the first of which we are aware to ask parents about their opinions about why bullying occurs. The findings presented here reveal some interesting opinions, many of which support the extant research around causes of bullying. The most common response was that bullies were modeling behaviors they witnessed and/or experienced at home; in other words, there is little the school can do to prevent bullying because they are learning these behaviors at home, not at school. A second very common response does flow from extant research; almost one in three parents felt the primary reason bullying occurred was because of the power differentials in the school setting. As with many other studies, the opinions of parents support that there is no single solution that will prevent all bullying. In fact, some of the parents in this study apparently felt there was little the school could do to prevent bullying since bullying started at home.

Although we believe this research has made important contributions to the research examining parental responses to bullying, there are several limitations to this study. First, the small sample of parents under study here was a sample of relatively affluent parents in a southeastern state. Consequently, the findings presented here may not be generalizable to parents in other parts of the United States or from other demographic strata even within the same local community. Second, the vast majority of parents providing data for this study were female; it would be interesting to examine gender differences in parental responses but we were unable to do so because of the very small number of fathers (four) that provided responses for this study. Nevertheless, given the limited research around parental attitudes and experiences with bullying, we believe these findings are still important in terms of gaining understanding of how parents experience bullying of their children.

The findings presented in this study lead to a number of important questions, and some methodological improvements, for future research. First, we believe it is important to gain a better understanding of how parents define bullying. Asking parents to define bullying, then developing a definition of bullying from those responses, is an important next step in the bullying research. After that definition is developed, it can then be used with additional samples of parents to insure that all parents are discussing bullying from the same perspective. Next, the findings uncovered here indicate that a second large hole in the research around parental perspectives on bullying is in the area of understanding the reasons why parents choose the strategies they do for helping their children address bullying. Quite frankly, the fact that so many parents would either go directly to the principal or to the alleged bully’s parents was surprising to us. Additional research is needed to not only better understand the advice parents are giving their children but the reasons behind that advice.

As Stives et al. (2019) and others have argued, there is still much work for teachers, school administrators, and educational psychologists around the messages that parents receive about bullying prevention. This is particularly evident in the responses parents had about 1) causes of bullying and 2) how they would handle bullying situations that involved their child. Information is widely available for parents around these topics if they choose to use it. However, work by teachers and school administrators to understand why parents are frustrated with the school’s lack of response to bullying, and the ineffectiveness of strategies used by school districts throughout the United States, is still needed.

As Stives et al. (2019) has suggested, school administrators and teachers play an essential role in bullying prevention when they enforce the rules regarding behavior at school. Nevertheless, it is also important for parents to have confidence that the strategies used by the school for bullying prevention are working. Evidence from this study suggests some parents are frustrated with what they perceive to be ineffective responses by the school and are willing to intervene with parents outside the school setting, or go directly to the principal when their child is being bullied. While most middle and high school principals would support the second parental strategy (even if it made their job harder), very few would support the first. Thus, parents need to better understand the messages that schools are giving their child regarding how to respond to bullying and schools need to do a better job telling parents how to respond to bullying on behalf of their children. Until this occurs, there is still much to do in the area of bullying prevention.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because these data were gathered as part of a project funded by the National Science Foundation and are subject to availability guidelines of that organization. Requests to access the datasets should be directed toY2JldGhlbEBjc2UubXNzdGF0ZS5lZHU=.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Mississippi State University Institutional Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Authors contributed to this research in the order in which they are listed in authorship.

This research was sponsored by National Science Foundation Award IIS-1408672 titled The Use of Robots as Intermediaries to Gather Sensitive Information from Children. Views expressed herein represent those of the authors and not necessarily those of the sponsor.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Baldry, A. C., and Farrington, D. P. (2005). Protective Factors as Moderators of Risk Factors in Adolescence Bullying. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 8 (3), 263–284. doi:10.1007/s11218-005-5866-5

Bentley, K. M., and Li, A. K. F. (1996). Bully and Victim Problems in Elementary Schools and Students' Beliefs about Aggression. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 11 (2), 153–165. doi:10.1177/082957359601100220

Bradshaw, C. P., Waasdorp, T. E., O'Brennan, L. M., and Gulemetova, M. (2013). Teachers' and Education Support Professionals' Perspectives on Bullying and Prevention: Findings from a National Education Association Study. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 42 (2), 280–297. doi:10.1080/02796015.2013.12087474

Compton, L., Campbell, M. A., and Mergler, A. (2014). Teacher, Parent and Student Perceptions of the Motives of Cyberbullies. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 17 (3), 383–400. doi:10.1007/s11218-014-9254-x

Cooper, L. A., and Nickerson, A. B. (2013). Parent Retrospective Recollections of Bullying and Current Views, Concerns, and Strategies to Cope with Children's Bullying. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 22 (4), 526–540. doi:10.1007/s10826-012-9606-0

Cortes, K. I., and Kochenderfer-Ladd, B. (2014). To Tell or Not to Tell: What Influences Children's Decisions to Report Bullying to Their Teachers? Sch. Psychol. Q. 29 (3), 336–348. doi:10.1037/spq0000078

Craig, W., Pepler, D., and Blais, J. (2007). Responding to Bullying. Sch. Psychol. Int. 28 (4), 465–477. doi:10.1177/0143034307084136

Ericson, N. (2001). Addressing the Problem of Juvenile Bullying. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Justice. Office of Justice Programs. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/fs200127.pdf.

Fekkes, M., Pijpers, I. M. F., Fredriks, M. A., Vogels, T., and Verloove-Vanhorick, P. S. (2006). Do Bullied Children Get Ill, or Do Ill Children Get Bullied? A Prospective Cohort Study on the Relationship between Bullying and Health-Related Symptoms. Pediatrics 117, 1568–1574. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-0187

Fekkes, M., Pijpers, I. M. F., and Verloove-Vanhorick, P. S. (2005). Bullying: Who Does what, when and where? Involvement of Children, Teachers and Parents in Bullying Behavior. Health Edu. Res. 20 (1), 81–91. doi:10.1093/her/cyg100

Harcourt, S., Green, V. A., and Bowden, C. (2015). “It Is Everyone’s Problem”: Parents’ Experiences of Bullying. New Zealand J. Psychol. 44 (3), 4–17.

Harcourt, S., Jasperse, M., and Green, V. A. (2014). "We Were Sad and We Were Angry": A Systematic Review of Parents' Perspectives on Bullying. Child. Youth Care Forum 43 (3), 373–391. doi:10.1007/s10566-014-9243-4

Hoff, D. L., and Mitchell, S. N. (2009). Cyberbullying: Causes, Effects, and Remedies. J. Educ. Admin 47 (5), 652–665. doi:10.1108/09578230910981107

Hymel, S., and Swearer, S. M. (2015). Four Decades of Research on School Bullying: An Introduction. Am. Psychol. 70, 293–299. doi:10.1037/a0038928

Jeynes, W. H. (2008). Effects of Parental Involvement on Experiences of Discrimination and Bullying. Marriage Fam. Rev. 43 (3), 255–268. doi:10.1080/01494920802072470

Jimerson, S., Swearer, S., and Espelage, D. (2009). Handbook of Bullying in Schools: An International Perspective. Philadelphia: Routledge.

Kowalski, R. M., Morgan, C. A., and Limber, S. P. (2012). Traditional Bullying as a Potential Warning Sign of Cyberbullying. Sch. Psychol. Int. 33 (5), 505–519. doi:10.1177/0143034312445244

Lereya, S. T., Samara, M., and Wolke, D. (2013). Parenting Behavior and the Risk of Becoming a Victim and a Bully/victim: A Meta-Analysis Study. Child. Abuse Neglect 37 (12), 1091–1108. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.001

Mishna, F., Pepler, D., and Wiener, J. (2006). Factors Associated with Perceptions and Responses to Bullying Situations by Children, Parents, Teachers, and Principals. Victims & Offenders 1 (3), 255–288. doi:10.1080/15564880600626163

Mishna, F., Sanders, J. E., McNeil, S., Fearing, G., and Kalenteridis, K. (2020). “If Somebody Is Different”: A Critical Analysis of Parent, Teacher and Student Perspectives on Bullying and Cyberbullying. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 118, 105366. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105366

Mishna, F., Wiener, J., and Pepler, D. (2008). Some of My Best Friends--Experiences of Bullying within Friendships. Sch. Psychol. Int. 29 (5), 549–573. doi:10.1177/0143034308099201

Modecki, K. L., Minchin, J., Harbaugh, A. G., Guerra, N. G., and Runions, K. C. (2014). Bullying Prevalence across Contexts: A Meta-Analysis Measuring Cyber and Traditional Bullying. J. Adolesc. Health 55, 602–611. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.06.007

Monks, C. P., Mahdavi, J., and Rix, K. (2016). The Emergence of Cyberbullying in Childhood: Parent and Teacher Perspectives. Psicología Educativa 22 (1), 39–48. doi:10.1016/j.pse.2016.02.002

Moore, S. E., Norman, R. E., Suetani, S., Thomas, H. J., Sly, P. D., and Scott, J. G. (2017). Consequences of Bullying Victimization in Childhood and Adolescence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Wjp 7 (1), 60–76. doi:10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.60

Mulvey, K. L., Hoffman, A. J., Gönültaş, S., Hope, E. C., and Cooper, S. M. (2018). Understanding Experiences with Bullying and Bias-Based Bullying: What Matters and for Whom? Psychol. Violence 8 (6), 702–711. doi:10.1037/vio0000206

Musu-Gillette, L., Zhang, A., Wang, K., Zhang, J., Kemp, J., Diliberti, M., et al. (2018). Indicators Of School Crime and Safety: 2017 (NCES 2018-036/NCJ 251413). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, and Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice.

Nansel, T. R., Overpeck, M., Pilla, R. S., Ruan, W. J., Simons-Morton, B., and Scheidt, P. (2001). Bullying Behaviors Among US Youth. Jama 285, 2094–2100. doi:10.1001/jama.285.16.2094

Offrey, L. D., and Rinaldi, C. M. (2014). Parent-child Communication and Adolescents' Problem-Solving Strategies in Hypothetical Bullying Situations. Int. J. Adolescence Youth 22 (3), 251–267. doi:10.1080/02673843.2014.884006

Olweus, D. (1997). Bully/victim Problems in School: Facts and Intervention. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 12 (4), 495–510. doi:10.1007/bf03172807

Patchin, J. W., and Hinduja, S. (2006). Bullies Move beyond the Schoolyard. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 4 (12), 148–169. doi:10.1177/1541204006286288

Sawyer, J.-L., Mishna, F., Pepler, D., and Wiener, J. (2011). The Missing Voice: Parents' Perspectives of Bullying. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 33, 1795–1803. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.05.010

Stevens, V., De Bourdeaudhuij, I., and Van Oost, P. (2002). Relationship of the Family Environment to Children's Involvement in Bully/Victim Problems at School. J. Youth Adolescence 31 (6), 419–428. doi:10.1023/a:1020207003027

Stives, K. L., May, D. C., Pilkinton, M., Bethel, C. L., and Eakin, D. K. (2019). Strategies to Combat Bullying: Parental Responses to Bullies, Bystanders, and Victims. Youth Soc. 51 (3), 358–376. doi:10.1177/0044118x18756491

Ttofi, M. M., and Farrington, D. P. (2011). Effectiveness of School-Based Programs to Reduce Bullying: a Systematic and Meta-Analytic Review. J. Exp. Criminol 7, 27–56. doi:10.1007/s11292-010-9109-1

Unnever, J. D., and Cornell, D. G. (2004). Middle School Victims of Bullying: Who Reports Being Bullied? Aggr. Behav. 30, 373–388. doi:10.1002/ab.20030

Wang, J., Iannotti, R. J., and Nansel, T. R. (2009). School Bullying Among Adolescents in the United States: Physical, Verbal, Relational, and Cyber. J. Adolesc. Health 45, 368–375. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.021

Wang, K., Chen, Y., Zhang, J., and Oudekerk, B. A. (2020). Indicators Of School Crime And Safety: 2019 (NCES 2020-063/NCJ 254485). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, and Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice.

Keywords: bullying, bullying prevention, parent responses to bullying, school, parental communication

Citation: Stives KL, May DC, Mack M and Bethel CL (2021) Understanding Responses to Bullying From the Parent Perspective. Front. Educ. 6:642367. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.642367

Received: 15 December 2020; Accepted: 05 May 2021;

Published: 18 May 2021.

Edited by:

Pina Filip, University of Messina, ItalyReviewed by:

Valeria Verrastro, University of Catanzaro, ItalyCopyright © 2021 Stives, May, Mack and Bethel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: David C. May, ZG1heUBzb2MubXNzdGF0ZS5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.