- 1Medical Faculty, Institute for Medical Psychology, University Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany

- 2Faculty of Education and Social Studies, VIA University College, Aarhus, Denmark

Social-emotional education and the relational competence of school staff and leaders are emphasized in research since they strongly impact childrens’ social, emotional, and cognitive development. In a longitudinal project—Empathie macht Schule (EmS)—we aim at evaluating the outcome and process of an empathy training for the whole school staff, including leaders. We compare three treatments to three control elementary schools via a mixed-methods approach employing qualitative and quantitative research methods targeting both, the school staff and the schoolchildren. Since the start of the project in 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the global education process, that is, the range of training activities for school staff in an unprecedented manner. First the lockdown and then the hygienic measures impact the habits and certainties in schools on multiple levels, including artifacts (e.g., physical distancing measures and virtual platforms), processes (e.g., virtual learning and home-schooling), social structures (e.g., separation of a high-risk group), and values (e.g., difficulties in building relations and showing empathy due to physical distance). Leaders and staff are facing an uncertain situation, while their actions and decisions may—also unintentionally—shape the social reality that will be inhabited to a significant extent. In this context, a number of questions become salient. How does the disruption of the pandemic affect interpersonal relationships, interactions, and the social field—the sum of relationships within the system of a school—as a whole? And specifically, how do the actors reflect on changes in the social field, their relationships, and the schools’ and classrooms’ overall relationship quality due to the crisis? The assessment combines qualitative interviews with leaders and teachers (N = 10) along with a self-report survey (N = 80) addressing the effects of the pandemic on interpersonal aspects in schools. Surprisingly, a number of positive effects were mentioned regarding the learning environment in the smaller-sized classes, which were caused by hygienic measures, as well as increased cohesion among faculty. The potential influence of these effects by consciously shaping relationships and cultivating empathy is discussed in the article.

Introduction

Children do not learn and develop in isolation but embedded in a web of relationships which make up a social field. The quality of these relationships determines children’s learning, development, and well-being (Rucinski et al., 2018). A great body of research addresses the social aspects of education (Durlak et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2017), highlighting the importance of social emotional learning. Furthermore, it is largely agreed upon that acquiring social emotional skills is crucial for children’s success and well-being in life (OECD, 2015).

But there is a need for more knowledge about whole-school approaches (Jennings and Greenberg, 2009) and how the pedagogical school staff can be supported in establishing empathic relationships to children, and a positive relational climate, to leverage children’s development as well as the well-being for pedagogues themselves.

To this end, a whole-school training program in relational competence, compassion, and mindfulness (Empathie macht Schule, EMS) has been launched targeting the whole school staff and leaders in three elementary schools (N ca. 180) over the course of, in total, 4.5 years. The training activities began in early 2020, involving for the faculty six off-site three-day modules, along with a parallel training for school leaders. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the already initiated training activities in an unprecedented manner. The new international research initiated in the context of the pandemic has examined both aspects, related to homeschooling and online learning (König et al., 2020). However, to date, we have not sufficiently understood how the pandemic affects the social climate and interpersonal relationships in schools. In this regard, the EMS project provides a unique opportunity for insights into the way school leaders and teachers experienced interpersonal changes in their schools, from a longitudinal perspective with also data before anyone knew about COVID-19.

Theoretical Background

In order to better understand the unprecedented and multiple effects of COVID-19 on the interpersonal aspect in schools, we take several entrances into the theoretical field. The aim is to be sensitive to a wide range of potential effects. What is required is to combine knowledge about 1) schools as multilevel complex systems and some of the properties of these systems which may change in times of crises (School as a Social Field), 2) about specific interpersonal and intergroup relationships (leader–colleagues, teacher–student, staff group, etc.) (Interpersonal Relationships), and 3) about social emotional learning and the capacities and competencies it entails (Individual Social Emotional Capacities). In sum, we consider three levels, which can be subsumed as the individual, the relational, and the systemic levels (the inner, inter, and outer, see Goleman and Senge, 2014). Thus, we attempt to draw from the various disciplines to shed light on the complexity of social life in schools, with a particular focus on the actors’ lived experience which is at the heart of a social field’s perspective outlined in School as a Social Field. Last, we will examine how crises affect these various levels (How Crizes Affect the Social Field) and examine the emerging body of research on COVID-19 with respect to the interpersonal effects of the pandemic in schools (COVID-19 Research).

School as a Social Field

In the context of the pandemic’s effects on schools, we are dealing with a highly complex system which has been described with properties or aspects such as self-organization, emergence, nonlinearity, and the processual functioning in terms of various movements toward, among other things, a dynamic equilibrium (see, e.g., Dynamical Systems Theory, Salvatore et al., 2015; Verhoeff et al., 2018; Atzil-Slonim and Tschacher, 2020). A decisive contribution of this theory is not only the modeling of complex systems but it also supports a change of perspective, away from the pure object reference to the focus on the relations—the in-between (Capra and Luisi, 2014).

Schools have been described as multilevel systems which comprise both their internal organizational structures and processes as well as the patterns of roles, activities, and interactions between and within leaders, teachers and other pedagogues, classes, and students, while being embedded within the administrative structures, community (including parents and families), education system, and society (Koth et al., 2008). This is the backdrop against which to understand how COVID-19 affected the in-between.

While a lot can be known about systems from an outside, third-person perspective, the phenomenological first- and second-person dimensions of a social system are often overlooked (Scharmer, 2009; Boell and Senge, 2016; Pomeroy et al., 2021). We employ the notion of the social field to specifically refer these dimensions to inquire into what it is like to be the actors within the system. The term addresses people’s lived experience while enacting a social system, including the experience of themselves, of their interactions and relationships, and, third, of the complex patterns that co-arise between the actors and the larger systemic context. Goleman and Senge (2014) refer to these three layers as the inner, inter, and outer levels. We are thus interested in knowing the system both from the “exterior” and the “interior”—the field. An important aspect of the social field is that it entails not only affective and cognitive but also bodily and somatic experiences—interbodily resonances between the people who interact in the physical presence of each other and which are the base for mutual understanding and intersubjectivity (Fuchs, 2017).

To understand the social field, we can draw from knowledge about the two well-established and closely related system-level constructs of climate and culture. From a systemic view, it has been noted that there are nested climates within a school which pertain to subsystems of a classroom, the faculty, or the overall school climate (Rudasill et al., 2018). The latter comprises the “affective and cognitive perceptions regarding social interactions, relationships, safety, values, and beliefs held by students, teachers, administrators, and staff within a school” (Rudasill et al., 2018). Factors shaping school climate are the levels of conflict or cooperation among teachers and students, the expectations regarding students’ academic achievement, and the sense of collaboration (Haynes et al., 1997; Juvonen, 2007). Classroom climate has been defined by Buyse et al. (2008) as the average level of emotional support experienced by children, with high-quality emotional support being characterized by warmth, respect, positive affect, teacher sensitivity, and low levels of anger, sarcasm, and irritability (Buyse et al., 2008; Pianta et al., 2012; Breeman et al., 2015). Classroom climate has been found to be related with children’s academic achievement (Pianta et al., 2008). A social field perspective on climate highlights lived experience, as expressed by one of Boell and Senge (2016) interviewees: “You can feel the climate of a school—it is how being in a school activates or touches all the senses.”

One feature of a positive school climate is a trusting atmosphere, fostering cohesion. Cohesion refers to the way in which actors achieve a dynamic equilibrium between their separateness and communion in relation to others (Marmarosh and Sproul, 2021). In healthy and adaptive social systems, cohesion means that actors are connected while maintaining their integrity. On a classroom level, social network cohesion involves higher generalized trust and prosocial behavior (Van den Bos et al., 2018). Generally, cohesion depends on factors such as the leadership of the group, role attribution, and role clarity. An important prerequisite for cohesion is the degree of identification with the group and the related in- and out-group phenomena (Dion, 2000; Benard and Doan, 2011).

The climate in a school and its classrooms—along with the degree of cohesion—can be regarded as an expression of the underlying culture, which comprises among others its system of role-based interactions as well as its values and basic assumptions—serving the two-fold purpose of the school’s internal integration (or cohesion) and its external adaptation (Schein, 2017). We turn now to the relationships which are particularly important for the social life in a school.

Interpersonal Relationships

The theory of organizational culture (Schein, 2017) emphasizes that leaders profoundly shape culture and climate. Several findings support this view with regard to principals’ effects on school climate (Kelley et al., 2005; Bulach et al., 2006). One study found that teachers’ perceptions of principal effectiveness go along with positive climate ratings, while perceived inconsistent leadership behavior involves lower ratings (Kelley et al., 2005). With regard to change processes, it was found that the closer the principals were connected to their teachers (with a more central social network position), the higher the teachers’ motivation to invest in changing their practices (Moolenaar et al., 2010). Furthermore, the affective principal–teacher relationship has been found to influence principals’ and teachers’ job satisfaction and cohesion (Price, 2012).

Supportive teacher–student relationships are of central importance for student well-being, academic achievement, and their social and emotional learning (Crosnoe et al., 2004; Hamre and Pianta, 2006). However, as a systems view suggests, teachers’ well-being and job satisfaction also depend on the relational quality. Schonert-Reichl found accordingly that a teacher’s burnout level correlates with physiological stress markers in schoolchildren (Oberle and Schonert-Reichl, 2016).

Individual Social Emotional Capacities

We have seen the paramount importance of interpersonal relationships on all levels of the school for the overall climate and thriving of all actors involved. We will now focus on the respective skills and competencies required for building positive, supportive, and empathic relationships. Here, many studies indicate the effectiveness of social-emotional learning programs. Not only can social-emotional skills be strengthened (Schonert-Reichl, 2019) but they also can predict school success and important life outcomes in adulthood. The SEL framework refers to five core competencies, namely, self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making.

These skills are particularly important for the pedagogues themselves, as implied in Juul and Jensens (2017), p. 2 definition of relational competence: “The professional´s ability to ‘see’ the individual child on its own terms and attune her behavior accordingly without giving up leadership, as well as the ability to be authentic in her contact with the child. And as the professional´s ability and desire to take full responsibility for the quality of the relation.”

Many effective programs for building social emotional skills as well as relational competence integrate contemplative approaches and skills: compassion and mindfulness. Put simply, compassion comprises a motivational, affective, and a cognitive part: recognizing painful experiences, turning to them empathetically, and driven by the willingness—if possible—to change them (Strauss et al., 2016; Ash et al., 2021). Training compassion thus both strengthens the basis of social interaction and learning—our ability to empathize with the feelings and thoughts of others and to resonate with them—and serves as a base to cope with the aversive and difficult experiences which are an inevitable part of one’s own and other’s lives in a healthy way (Singer and Klimecki, 2014).

Mindfulness, in addition, describes the ability to focus attention on the present moment of experience without judging the content of the experience and to adopt an accepting attitude. Mindfulness involves an improved self- and emotion-regulation, as well as self-perception (Lindsay and Creswell, 2017), while indirectly also promoting behaviors that are more closely oriented toward one's own values by interrupting behavioral automatisms (Kabat-Zinn and Hanh, 2009; Tang et al., 2015).

How Crises Affect the Social Field

In the following, we present research and theoretical insights on the potential effects of crises on the social field. On a physiological level, decades of research suggest that permanent stress—particularly existential threat in a context of high uncertainty—brings along more automated stimulus–response mechanisms or fight–flight–freeze mechanisms. Furthermore, it is proven that humans as social beings (Baumeister, 2011) benefit in the sense of a stress buffer from feeling socially integrated, socially supported, and co-regulated (Cassel, 1976), for example, through touch and contact (Morrison, 2016), which was and is considerably limited by the physical distance in the pandemic situation (e.g., Szkody et al., 2020). Self-protection against burnout by down-regulating empathy is short term and misguided (Vaes and Muratore, 2013). On the contrary, the more volatile, unpredictable, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) our everyday life is, the greater the need for social-emotional competencies, which are at the core of adaptive coping strategies (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984; Hadar et al., 2020).

This is especially relevant for leaders since their impact on culture and climate—as suggested by (Schein 2017), is exaggerated in times of organizational crises. Even more so, when adaptation requires changing preexisting cultural roles, habits, or assumptions, in this case, leaders according to Schein must step outside the culture that created the leader and start evolutionarily adaptive change processes.

On a systems level, social systems tend to respond to crises with greater social cohesion, but can also intensify subgroup processes and conflicts between in- and out-group members (Jonas and Mühlberger, 2017; Jetten, 2020; Marmarosh and Sproul, 2021). Not only is cohesion affected by crises but also it shapes an organization’s capacity to respond to crises (Kahn et al., 2013).

COVID-19 Research

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, tens of thousands of schools just counting in Germany were closed in March 2020. Schools started reopening a few months later, but various restrictions remain. Many of the studies in the emerging field of COVID-19–related educational research emphasize issues of virtual learning (e.g., Bergdahl and Nouri, 2020; König et al., 2020). With regard to relational aspects, König et al. (2020) accentuate that maintaining social contact with students and their parents during lockdown (see also Eickelmann and Drossel, 2020) is a primary challenge, which was mastered by almost all early career teachers in their survey, including introducing new learning content, assigning tasks, and providing feedback to students. A similar study emphasizes (Bergdahl and Nouri, 2020) that the teachers reacted positively to seeing students in their home environment, expressing surprise to discover better student contact (Bergdahl and Nouri, 2020). None of these studies do, however, discuss the teachers’ reflections on social emotional and relational aspects.

A new OECD rapport (Reimers and Schleicher, 2020) on effective education responses to the COVID-19 pandemic addresses next to online learning social emotional aspects also recommending, for instance, to enhance the collaboration and communication among students to foster mutual learning and well-being. Results from a Danish research project (Egmontfonden, 2020) conclude that those most negatively affected from the lockdown are the most vulnerable students. They however also emphasize positive aspects in relation to more time for the individual child and the lockdown providing some students with a needed relief from the everyday social demands. Jørgensen et al. (2020) in a report from another Danish project conclude that for 75% of the students, positive and negative experiences balance each other, and for the last 25%, there is a 50/50 division in perceived effect on well-being. Half of these students missed their social relations to a degree where they refer to loneliness, deprivation, and sadness, while the other half refer to relief from performing socially in the everyday life at school, enjoying the extended focus on the close relations in the family during the lockdown. As emphasized by Beauchamp et al. (2021), there are few studies involving the school leaders. They contribute with new perspective on leadership with data from the initial stages of this pandemic, discussing the necessity of enhancing relationships in the face of situational ambiguity and external pressures (Beauchamp et al., 2020).

All in all, there is a call for more research looking into the social field at a school, examining how this was affected by the pandemic, from the inside perspective of the pedagogical professionals, including both teachers and school leaders.

Research Question

How does the disruption of the pandemic affect interpersonal relationships, interactions, and the school’s social field as a whole? And specifically, how do the actors reflect on changes in the social field, their relationships, and the schools’ and classrooms’ overall relationship quality due to the crisis?

Materials and Methods

Research Design

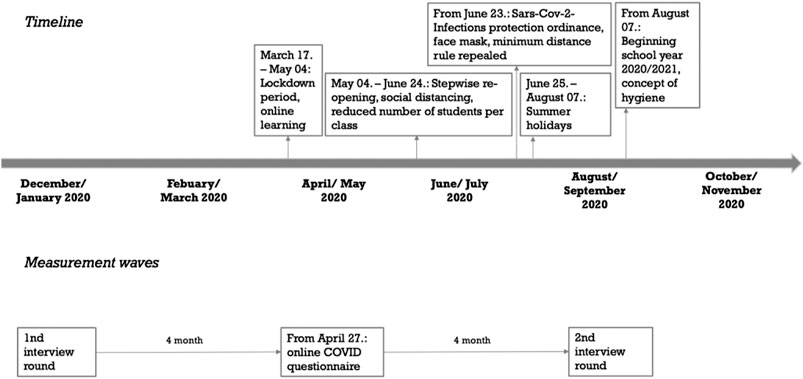

The research design is a sequential mixed-methods design with a QUAL priority (Creswell and Clark, 2017). The chronology is illustrated in Figure 1. The first round of interviews was before the pandemic, as part of the data collection in the context of the longitudinal EMS project. Hence, the research was embedded within a larger intervention design (Creswell and Clark, 2017). During the lockdown, questionnaires designed to address the specifics of the disruption (more below) were distributed. The second round of interviews in the period of reopening followed up on the questionnaires examining in-depth informants’ experiences from the lockdown. Regarding the sequential design, these interviews furthermore followed up on insights regarding relationships at the schools from the preinterviews before the pandemic. This design addressed the need for insight into the social relationship before, during, and after the lockdown.

FIGURE 1. The chronology of data collection, training process, and measurement waves along with the COVID-19–specific events in the Berlin education system.

Participants

The participating schools for the EMS project were recruited through various communication channels, including e-mails to headmasters of 107 Berlin elementary schools and a presentation at a school leader assembly. In order to participate, schools had to meet the eligibility criteria: regular, elementary state schools, no all-day school, but half-day school with after-school program; a majority of the faculty in favor of the participation (vote); and faculty size of 40–50 members. From the interested schools, three schools were sampled from municipalities representing a social economic diversity, one of which ranks as a high-risk school (“Brennpunktschule”). Interviews were conducted with school professionals (N = 11) from each school. Among them were the leadership team members (N = 7), including principals (2 female and 1 male), coprincipals (3 female), and—due to school B’s organizational structure—also the after-school program leader (Hortleitung) (1 female). Furthermore, pedagogues from each school were interviewed (total N = 4) (teachers and child-care workers)––who had participated in the first training module in March 2020, prior to the lockdown. In the following, we use the term pedagogues to refer to all professionals working with children at the schools.

Besides the qualitative interviews, a total of N = 80 pedagogues participated in an online survey (school A N = 24; 30%; school C N = 38; 47.5%; school B N = 18; 22.5%). The mean age was 46.49 (SD = 11.42; range = 24–69) years. N = 16 (23.5%) participants indicated to be male, N = 49 (72.1%) stated to be female, and N = 3 (4.4%) specified to be diverse.

Data Collection

The first round of qualitative interviews—which we call preinterviews—were conducted prior to the first EMS training period in December 2019 and January 2020, in-person, in the respective principals’ offices. The second round of (partially, follow-up) interviews was conducted in September 2020 in online video calls—after the first lockdown period in spring and at the onset of the new school year of 2020/2021. Interviews were recorded, and recordings were transcribed verbatim (Brinkmann and Kvale, 2015).

Quantitative data were obtained using a questionnaire (Quantitative Instruments) programmed as an online tool (www.soscisurvey.de) and administered virtually during the lockdown.

Qualitative Instruments

Three semi-structured interview protocols (Brinkmann and Kvale, 2015) were developed for this study, two for principals and one for the pedagogues. Comprehensive interview protocols can be found in the Supplement B. Principals were interviewed sequentially. The first interview involved questions about school culture, the relational climate, current challenges of the schools, and about the principals’ aspirations for joining the EMS project. The second, follow-up interview addressed experiences concerning the impact of COVID-19, their role as principles, and their experiences concerning the relationships within the learning community. For validation purposes, these follow-up interviews also involved a member checking on the main themes emerging when analyzing the previous interviews. Furthermore, participants were invited to elaborate on whether and how these main themes were affected by the pandemic. The interviews with the pedagogues covered questions on the training module’s impact and climate, as well as the impact of COVID-19 on the relationships with children, parents, colleagues, and within the learning community as a whole.

Quantitative Instruments

We designed a questionnaire tailored to the pandemic focusing on relational aspects (contact, empathy, etc.), which was also focused in the interviews. In more detail, the questions refer to the burden caused by the situation, the contact among colleagues and students, the satisfaction with building relationships via digital media, the ability to empathize with the students in the current situation—such as the concerns about the students—and finally, a resource-oriented question whether something positive can be gained from the pandemic situation. All questions were answered on a visual analogue scale (0–100). The items and answer formats can be found in Supplementary Material.

Official School Statistics

School and municipality statistics were obtained from official Berlin government sources. The Berlin government regularly assesses and publishes statistics about all schools, including variables such as size of the student population, number of non-native speakers, faculty size, and available work force. We display these official figures as made publicly available on the website of the Berlin Senate for Education (https://www.berlin.de/sen/bildung/schule/berliner-schulen/schulverzeichnis/Schulportrait.aspx).

Data Analysis

Thematic Analysis of the Qualitative Interviews

The qualitative interviews were analyzed following the procedures of inductive thematic analysis where emerging themes become the categories for analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006). For example, the theme regarding losses and gains of structure was constructed based on the utterances in the interviews. For transparence, findings are reported under the thematic headlines with example quotes (see Supplementary Table S1 for the analysis of the qualitative data). The themes were iteratively condensed and described in a collaborative process of careful reading and rereading the data individually followed by repeated discussions among the researchers. This process continued until agreement about themes.

Preinterviews with school leaders are, together with official school statistics, used to describe the schools. Furthermore, preinterviews are used as a reference in the discussion of the impact of COVID-19. Data from the postinterviews are presented to report on the school professionals’ reflections on how the pandemic has affected relationships and interactions. These aspects are also addressed using the quantitative questionnaire data (triangulation).

Quantitative Data

We conducted a one-way ANOVA to assess the effects of the seven items of the Corona survey in the three different schools. Homogeneity of variances was asserted using Levene’s test which showed that equal variances could be assumed (Levene’s test, p > 0.05). At the same time, to test if the mean values of the individual survey items differ significantly between two of the three schools, we conducted post hoc the LSD (no correction of alpha error accumulation) and Tukey’s test (alpha error accumulation correction) to clarify the single comparisons between schools A and B, between schools A and C, and between schools B and C. Additionally, we exploratively tested for Pearson’s correlations between the single items. We used IBM SPSS26 for all statistical analysis.

Ethics Approval

The overall study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Heidelberg Medical Faculty (S-526/2019). Prior to participation, all participants provided written informed consent.

Results

We report both qualitative and quantitative findings. In order to contextualize the qualitative findings, we also show figures from schools’ and their respective municipalities’ official statistics.

Description of the Schools

School A is situated in a municipality in the southwest of Berlin, with relatively low rates of poverty (12.3%) and unemployment (5.9%) (Mitte, 2018). In school year 2019/2020, 47.9% of the school’s 434 students learned German as a second language (for all school statistic data, see Supplementary Table S2). In the preinterview, the leaders of the school stressed the importance of positive, appreciative communication as a core value. Accordingly, one of their main goals was to maintain and improve the structures and processes that enable good communication. This brought along the leadership challenge of dealing with faculty members not living up to the leaders’ standards.

School B is located in a municipality in the east of Berlin, with 19.1% of the population in poverty and unemployment of 7.1%. In 2019/2020, 34% of School B’s 442 students learned German as a second language. In the preinterview, the leaders reflected on the level of trust among the whole school staff, which had been lacking when they joined the school several years ago, and which they since had been working on building. At the time of the interview, the school was joining EMS, and polarized conflicts and division between faculty members were resurfacing. The leaders also stressed the importance of an empathic learning environment for the children’s flourishing.

School C is situated in a municipality in the west of Berlin, with the highest poverty and unemployment rates (9.5% and 27.9%, respectively). It has an official status as high-risk school (“Brennpunktschule”) receiving special aid. In 2019/2020, 91.5% of its 434 students learned German as a second language. Key challenges mentioned by the leaders in the preinterview were a lack of both qualified staff and of adequate structures and processes in the organization of the school. Building coherent structures was an important goal. The leaders characterized the school climate in terms of an existing sense of community among faculty, which was based on the common challenge of working in such a school, but also in terms of a lack of appreciative communication.

Survey-Based Results

The descriptives of the dependent variables are depicted in Supplementary Table S3, whereas the means and standard errors are shown in Supplementary Figure S2.

The correlations of the seven items are shown in Supplementary Table S4. To pick out three essential correlations, it is interesting to note that the association between “own stress” and “worries about the students” correlates most strongly and significantly with each other, and also, “gaining something positive out of the pandemic for work” is related to both the “good functioning of the contact with the students” and the “perceived ability to empathize with the students.”

The one-way ANOVA revealed no statistically significant differences.

Perspectives on Changes in the Whole-School’s Social Field

We present our qualitative findings on the perceived changes in the social field beginning with the interviewees’ perspectives on how the crisis shook up the structural conditions (the rules, regulations, and processes). These are the backdrop for other changes in the social field, such as various group-level effects on climate (School and Classroom Climate) and cohesion (Conflict and Cohesion: Operating Like a Single Body), and more specific inter- and intrapersonal effects (Perspectives on Interpersonal Relationships and Perspectives on Social Emotional Capacities).

Disruption and Uncertainty: Losses and Gains of Structure

The pandemic disrupted the processes and structures usually defining schooling. With regard to the social aspects, the following factors were mentioned: lockdown, along with a lack of direct social contact, switching to virtual communication and online platforms, and very different tasks for teachers compared to child-care workers; the imposition of social distancing measures which had to be specifically adapted to each school and communicated to faculty and students; and the structural and processual changes involved in these distancing measures, such as divided classrooms, learning in smaller groups, or impaired communication with other faculty members.

The disruption of the schools’ structures and the rebooting with a new set of rules were experienced in both negative and positive ways. For the school leaders who in the preinterview highlighted the value of structures, this was a negative experience. As leaders of school B illustrate: “..this extreme situation, with masks, distances, organizing the everyday life. And we are all so trapped in this […] now we have to struggle for the basis by trying to do COVID-19-conform schooling.” This puts other problems into proportion: “Some things appear to be trivial now, which previously caused us big problems.” The leader also reflects on the lack of structure: “When I realized that part of my oblivion and of my tension is due to the lack of any sort of support in the form of structures and habitual patterns. That was, well, impressive, how much one needs this.” While many experienced a loss of structures, the situation was also an opportunity to establish new structures. This was the case in school C which had been marked as chaotic in the preinterview. The school leader recounts that “parallel to COVID-19 we structured our school more strongly.” The crisis was seen as a support and he reflected on whether the school should keep “the structuring elements, which COVID demanded from us via hygienic measures, hygiene one-way roads, and separated school yard, and so on.”

Another response to the disruption was insecurity and holding on to the familiar. The leaders of school A reflect on how in the midst of this uncertainty, their faculty was trying to preserve their faculty room: “We wanted to open a second faculty room and it is incredibly hard […]. This safety in this room means so much to them.” And “muddling” with this, “creates total uncertainty, […] fear or aggression. Everyone shows it a little bit differently […] But they show it. That they are insecure.”

As we will see in later paragraphs, the loss of routines also affected the relations. For instance, in after-school emergency childcare, when the pedagogues were faced with changing constellations of students unfamiliar to them: “There were no rituals and no fix points. What would be good for everyone now? It was a time of challenge, and relationally a remarkable challenge.”

These findings confirm the lockdown as a situation of crisis and further adds to the understanding of this not just having implications in terms of talking about emergency remote (online) teaching (Bergdahl and Nouri, 2020; König et al., 2020). It appears to be urgent to consider the situation as disrupting the full system.

School and Classroom Climate

School leaders describe changes in the affective climate during lockdown, reopening, and in the ongoing “new normal” school year. When first reopening, the climate in school B was described as “very numb.” Children and faculty were perceived to comply with the distancing measures “with great respect and a little fear” with an awareness of the big responsibility. At the same time, leaders mention the absence of extracurricular activities which “carry community,” such as Christmas and lantern parades. The climate during the early reopening was likened to “moving cattle” and a “ghosthouse,” where “everything in the beginning feels a bit dangerous.”

Positive changes were, however, also mentioned. For the leader of school C, these were “exciting times with a good feeling, “fulfilling.” Also, among the teachers, there was a lot of positive energy.” He describes an “almost euphoric situation.”

Later, having habituated to the distancing measures, the pedagogues describe a more “relaxed atmosphere” with a higher sense of “connectedness” and “calm”: “the children suddenly perceived this connectedness very strongly. To the school, to those who are there. It was a relief for them not having to be at home with their stressed parents.” A teacher expresses it more strongly: “When the schools were opened again […] that was for everyone involved, also for the children, a very pleasant, intense, and beautiful time.” Accordingly, leaders report children told them: “‘we are happy that we are allowed back to school.’ And that really means something with five- and sixth-graders.”

Hence, school and classroom climate were affected by the lockdown with increased fear and connectedness (as expected in crisis situations: Jetten, 2020)

Conflict and Cohesion: Operating Like a Single Body

COVID-19 affected the intensity of conflicts as well as the level of cohesion differently in each school. The leaders of School B who in the preinterview described their faculty as rather divided and prone to destructive arguments experienced a shift: “What I notice is rather that the colleagues have less conflicts with us or among them, because many are busier with themselves.” What is more, “Actually, they seek the support of the others. Affirmation. But I think, no one has the energy or nerves now to quarrel with one another.” The leaders noticed that even the school timetable, which usually is a conflictive issue, does not elicit the same amount of complains. In addition, the after-school faculty, previously marked by mutual rejection and an unwillingness to voice one’s opinion, now surpasses the leader’s expectations “operating coherently like a single body […] like a cat with eightteen legs walked […] in one direction.”

On the other hand, for the leaders of School A, the situation brought up more conflicts among faculty: “Because everything is already a little bit tense and stressed, we notice … small dissonance more intensely. Well, things pop up which during calmer periods would not have popped up in such a way.” In this school, intense conflicts with parents surfaced (as described in Perspectives on Social Emotional Capacities). Another line of conflict which was surprising for School A’s leaders showed up between “school and after-school.” The leaders elucidate that after-school staff was not exposed to the same degree of parental pressure and that after-school staff therefore does not comprehend the strict COVID-19 strategy.

This “division” between school and after-school was also mentioned to be strengthened in School C: “Appreciating, that has always been difficult between these two groups just like in many schools. I would say due to the separation of tasks [during COVID-19, inserted by author] there is a little bit of alienation.”

On the other hand, leaders express an appreciation for the quality of their relationships to the faculty, highlighting trust and a good team spirit. For instance, School B’s leaders believe they could deal with the challenge of COVID-19 due to the team structures and “basic trust” that had been established: “The fact that we could really rely on the colleagues was very impressive to us.” The leader of School C describes the “crisis mode” as an increased cohesion: “These were really long work days, but we noticed that we had a good team spirit. [..] In which many applied themselves with dedication.” School A’s leaders reflected elaborately on the level of trust. For them, trust is shown when a faculty member feels safe enough to give honest feedback that she is not able or willing to follow the leader’s orders:

“And at some point, a colleague showed up and said: ‘Stop! I can’t continue like this! I still have a child at home […]’ and to notice then: […] There is our buffer, that we can say: OK, there is enough trust that one can tell us: This is too much now; we can’t fulfill this.”

The situation also brought up controversial issues. During lockdown, this concerned especially virtual learning and online meetings: “Some colleagues refused for a long time […] participation in videoconferences.” A particularly controversial issue was the use of the Zoom software, which eventually was forbidden to use by the Berlin Senate for privacy reasons. With regard to the reopening, issues concerned in particular distancing measures. A teacher concludes: “It is logical that not everyone is always happy with such democratic decisions.“ In this context, she expresses appreciation for the leaders of school A who “think INCREDIBLY much in advance,” but also involve the faculty, as she paraphrases: “‘OK we need a new plan for the hygienic measures. We have already prepared this a little bit, but now it’s your turn.’”

Among children, a drop in conflicts was observed by pedagogues and school leaders. As the leaders of School C elucidates: “Usually the violence incidents pile up here in my office, every day. When I began working here, this made up 30% of my work time, always calming down weeping, injured children and totally exhausted teachers.” Now, they see “hardly any” incidents.

To sum up, we see that the crisis affected school cohesion, both by increasing and by decreasing it, further by deepening of existing divides between faculty subgroups. This confirms that the ways groups have been described to respond to crises are at play in schools during the pandemic (Jetten, 2020; Marmoush and Sproul, 2020).

Children Follow the Rules—With Some Fear

One theme raised by all pedagogues and leaders is children’s willingness for cooperation, their way of complying with the new rules, and adapting to the situation. Even very strict measures, such as in School A compartments on the yard for each class, and a queuing system for the students to reenter the building, are complied with: “I would have NEVER thought that this works out so excellently. And brings about CALM.” While the pedagogues experience the measures as “alienating” and are reluctant to them, being reminded of “the East [the German Democratic Republic, inserted by author]” they also acknowledge that the children “walk in orderly, are aligned inside.”

During early reopening, when the building was for the first time prepared for the distancing measures, with arrows on the floor for each class, the children’s cooperation was perceived to involve a level of anxiety (“You saw the fear in the eyes of some”), which later on decreased:

“Some which can barely walk up the stairs, because their legs are too short as first graders, but in NO WAY wanted to touch the handrails. So they struggled their way up, filled with effort and torment. Other sixth-graders, which are very anxious. One could also see their fear very visibly.”

In addition, school leaders reflect on the new conditions and how these may affect the children. The conditions are marked by a “lot of lessons and regulations” as well as a lack of extracurricular activities, festivals, and “school as a habitat,” which promote children’s well-being. Within these conditions, children are perceived to cooperate: “Everything is strictly arranged and regulated. Children join in really well, but […] I can sense that they are missing this [extra-curricular school life, inserted by author].” The leader of school C reflects whether the strong structures and rules may also have had a positive impact on children, giving them “support.” Furthermore, the reduction of academic demands was seen as positive for the children.

Children Flourish in Small Groups and Individual Settings

Next to distancing measures and the loss of extracurricular school life, there were also positive changes for children. A consistent and prominent theme which surfaced across all professions was the observation that the students profited from the small group settings. As one teacher puts it: The children “felt seen! […] It was simply great to witness this, they really flourished.” Accordingly, also the more individualized settings in after-school work were appreciated, as a child-care worker highlights: “They will NEVER have a better learning environment.” Interestingly, even in virtual settings during lockdown, which also encompassed smaller groups or one-on-one settings, teachers reported to perceive “each individual learning progress more intensely.” For pedagogues, this was such “a beautiful experience” that they prefer to continue their work in these small group settings. As a teacher recounts: “We went to the school leaders and told them: ‘What we take out of this: Small groups are useful.’” A child-care worker decided for the ongoing school year to change her work profile in order to continue the individual support, “Because the children can’t receive more from me than in this unblocked, unburdened environment.” Congruently, school leaders express their appreciation for small group sizes: “It was beautiful to see how children develop differently in this small group. […] I found that VERY impressive.” In particular, the interviewees express that the small groups—and feeling seen by the pedagogues—affect children’s social roles in the classroom in positive ways (see Calm Children More Visible, Others Totally Gentle). These results add to the findings of improved student contact in online settings during lockdown (Bergdahl and Nouri, 2020), highlighting that small classrooms are contributing to positive climate and teacher–student relationships (Calm Children More Visible, Others Totally Gentle).

Replotting the Social Field: Less Awareness of the Whole School, But of Subgroups

The temporary intensification and improvement of relational quality in classrooms is one example of a broader trend. This trend can be described as contracting the social fields’ boundaries to the inclusion of a smaller number of significant relationships. Especially during lockdown and reopening, pedagogues report a reduced awareness of the whole of the faculty and school while experiencing more intense relationships in certain subgroups. When asked about the impact on the whole school’s learning community, one teacher replied: “I find it actually difficult to tell […] because it became very individualized.”

A leader elucidates: “This relating-back-to-oneself among colleagues, in the same way the children relate back to their groups.” During “seemingly chaotic” breaks, when asking the children, they answer: “‘we are among us. It is our class!’ So they relate back to THEIR group.” While the interaction with the whole faculty was limited during lockdown and the early reopening, within subgroups, the relationships were strengthened and intensified. For instance, a teacher from School B, which is structured in grade-specific work groups, reports: “I got much closer with colleagues in my grade. We actually met regularly on Zoom, or on Skype, and at times spoke for one and a half hours about, how do you do it with your first graders? What else can we do for them?”

Perspectives on Interpersonal Relationships

Changes in outer structures and rules as well as social fields’ boundaries and textures also involved changes in interpersonal interactions and relationships. People in school were forced to take new social roles. This was the case on all levels of the school hierarchy, in the leaders’ relations to faculty (School Leaders’ New Role as Safety Managers), the teacher–student relationship and relations among students (Calm Children More Visible, Others Totally Gentle), and school professionals’ relations with parents (Teachers as Human Beings and Parents Grateful—Or Aggressive).

Lack of Physical Closeness and In-Between Nuances

Distancing measures lead to a lack of physical closeness in the relationships among school professionals and students. Leaders recount how their faculty spoke about this lack as a problem in their work with the children:

“…they said, ‘one is so happy to see them again. And usually one would have made physical contact […]. And suddenly one can’t hug the little brats […].’ You don’t say ‘good day’ to people anymore, and this does something to you. When this closeness is lacking. […] Whether as leader or teacher, one responds to those in-between-nuances a lot and this dropped away somehow.”

With the loss of in-between nuances, the leaders’ motivation for the work was impacted: “the lifeblood which we have in this job […] wasn’t on the agenda.”

A pedagogue who felt lonely analyzed what it was exactly that she was missing:

The contact […] never really broke up. Right? But we were writing on Whatsapp or just some e-mails, but this, this contact: I tell you something, and you react immediately. You recognize in my mimic how I am doing or what I really mean. This, right? Well, […] mimic and gestures.

This lack has been mentioned in previous studies on COVID-19 (Beauchamp et al., 2020). It underscores the relevance of the domain of interbodily resonance (Fuchs, 2017) for social relations.

Calm Children More Visible, Others Totally Gentle

Interviewees highlight consistently that the children flourished in the new small group settings. Specifically, this involved changes in the teacher–student relationships (children feel seen—see Children Flourish in Small Groups and Individual Settings) and in the relations among students. A school leader expresses her appreciation about “how to some extent they became more courageous. How their roles changed.” For instance, a teacher elucidates that “calm children, which don’t push into the foreground, they were suddenly there […] raising their hands endlessly.” They stopped “drowning in the masses.” In addition, children described as “difficult,” “all the super flashy ones, the super extreme ones, […]were totally gentle. Everyone enjoyed it a lot. Yes, the difficult children. With whom everyone is struggling so much.”

Not only did the individual children flourish and show up differently, also their interactions with peers changed, as one teacher retells:

“Usually in the small break […] they run through the classroom and throw their pencil cases around and quarrels are inevitable. They had to stay seated during the five-minute-break. So they stayed seated. I could also trust them. So I left the classroom and went outside to the faculty room opposite. And they started a CONVERSATION. What they otherwise NEVER really do. The ten of them […]. They simply TALKED with each other in a very relaxed atmosphere. Within this threatening situation.”

Looking back at the teaching situation in small groups, the teacher concludes: “I didn’t have to settle any argument. Not a single one.”

This shift in students’ social roles and interactions coincides with improved teacher–student relationships (“feeling seen,” 3.3.5.). This is in line with the prominent role of teacher–student relations in shaping classroom climate, social and emotional competencies, and academic achievement (Crosnoe et al., 2004; Hamre and Pianta, 2006), as well as teacher well-being.

School Leaders’ New Role as Safety Managers

The main issue mentioned by all the school leaders concerns changes in their role as leaders facing the novel challenge of creating and carrying out a safe reopening plan “to protect the families, the children, the colleagues.” Leaders reflect on this new role and the feedback and responses it elicits in a variety of ways. The leaders of School A which upheld dialogue and appreciative communication as their core values in the preinterview experienced a role conflict: “It was very strange for us, because we had to give a lot of orders quickly, without talking to the faculty.” They describe their role further: “It was orders. Orders, orders, orders” and “No talking, no time for appreciation, no time for seeing the other, not much time for listening.” They experienced rather negative responses from the faculty members and parents (see section on conflicts). In contrast, the leaders of School B characterize the role as one of an almost unquestioned leader: “In the time when we made those plans, they [the faculty, inserted by author] accepted it fully. There weren’t any big enquiries. You were the decision-maker: So it is. Fullstop.” The leader of School C reflects on these changes in mostly positive terms. His new role entailed mostly “confidence-building.” The faculty met him with a lot of “acceptance and trust,” “so-to-say as a representative of the state or a liaison to the public health department.” This leader describes that he was “always upfront” regarding the safety assessments and regulations, which brought along a sense of safety for the faculty. These results show that the leaders’ transition into their new roles was influenced by the leaders’ and schools’ values, indicating that the pandemic affected schools on the level of culture (Schein, 2017).

Teachers as Human Beings and Parents Grateful—Or Aggressive

Pandemic and lockdown were difficult times for many parents, too. This affected the school professionals’ roles in the relation to parents. On the positive end, this involves “humanization” and appreciation illustrated by the following example. A teacher had written an e-mail to the parents apologizing that she had not been able to support all of the students on that day, due to a “mid-size catastrophe” with her own two schoolchildren. The teacher paraphrases the parents’ responses:

“‘It is SO GOOD to see that you are also only a mother. That also for you NOT EVERYTHING is working out smoothly! We have such an underSTANDing for you!’ And suddenly I became a human being for them. Not an Übermensch anymore. But human. And that was obviously a relief for them.”

Another teacher who engaged the students in regular virtual writing activities to structure their day, also in the mornings, received partly positive feedback: “Some parents were very grateful for this. Others I had to throw out of their bed (laughter).”

Besides such positive shifts, also negative developments were described, such as “extreme parent-teacher conferences.” “The parents went up to the ceiling. It was impossible to regulate them. Out of stress, out of worry. Well, Corona. Out of certainly existential urgency, fear.”

This is in line with the leader’s description: The leaders of the same school (A) experienced a lot of demands from parents including “explicit aggression.” The leaders reflect further:“The aggression came from the fact that teachers partly didn’t support the children as they should have, and that was partly correct […] we had to re-adjust. And talk to the teachers.” This influenced their leadership strategy, prioritizing stricter hygienic measures to prevent another school closing.

These findings extend on what has been described as a blurring of the professional boundaries between teachers and parents (Beauchamp et al., 2020), and further highlight the necessity to foster positive relationships to parents.

Perspectives on Social Emotional Capacities

The interviewees described their experiences also in terms of intraindividual, inner changes which relate to the bases of their social emotional capacities—the dimensions of affect (Affective: Loneliness and Relief), stress (Physiological: Stress and Shutdown), resilience, successful coping, and creativity (Behavioral: Resilience and Creativity in Coping With Lockdown), as well as the deliberate use of input from the empathy training (Working With the Input From EMS).

Affective: Loneliness and Relief

The way the interviewees described their affective responses to the situation varied between individuals, for instance, regarding the lack of contact to colleagues:

“I felt lonely. Well, there was no exchange with colleagues anymore, because every class […] had lessons at different times. […] well, the communication with children is wonderful. But the […] exchange with adults. Also with the special pedagogues. This direct exchange. I missed that a lot.”

In contrast, another pedagogue felt relieved: “I didn’t see anybody anymore. It was phantastic. I only did my work on the child. It was wonderful and regenerating.”

Physiological: Stress and Shutdown

High workload and stress were mentioned by all leaders and pedagogues. As a teacher puts it: “Lockdown was stupid. Lockdown was a catastrophe. Lockdown caused me to feel completely burned out afterward.” These increased demands continue in the ongoing school year: “If you take a look at the faculty, many say that they are as exhausted as if they were standing shortly before the autumn break.”

Behavioral: Resilience and Creativity in Coping With Lockdown

Under this stress, teachers expressed resilience and determination:

“With one girl, I even tried to phone her 10 times within five days. Always at different day and night times and parents by default would not answer the call. I brought children’s homework to their homes. I had children practice reading and writing with me on their courtyard with a lot of distance, on the grass.”

The same goes for establishing virtual communication, which another teacher described as their “greatest show of strength” and “incredibly effortful.”

Once contact was established, the teacher emphasizes that she “couldn’t stop” working with the children even throughout holidays: “Because then I thought: Now I have the children. Now. For the children there are no Easter holidays, are there? It is totally irrelevant, if it is called ‘Easter holidays’ or not.”

The pedagogues furthermore found ways to work creatively within their structural confinements, such as the school’s text-based online learning platform:

“I pulled myself together, what is possible to do virtually somehow. And we then began to write stories together on the school cloud. It was very exciting in the beginning and very beautiful. […] We made agreements: Everyone writes one or two sentences. And then we invented stories. In the end we finished a thick book full of stories and this was a very, very beautiful experience. […] And the children, not all of them, but many, enjoyed it a lot.”

These reports confirm previous findings (König, 2020) that maintaining contact with students and parents during lockdown was a primary challenge.

Working With the Input From EMS

School professionals report about working with a variety of the empathy training’s (EMS) elements (e.g., mindfulness and empathic dialogue) in various settings with children (classroom and individual tutoring), parents, and faculty, as well as for self-regulation. A pedagogue illustrates co-regulating children in individual settings: “It was always like: ‘Come. First exhale. How are you, actually? Put your papers to the side. Are you nervous? Feel your heart.’ […] I can attune myself to the child while I am also completely with myself.”

Relating to parents, an intentionally compassionate stance was illustrated: “this ‘I see’, I see your fear”: “I start conversations with parents in such a way: […]‘It’s a hard time.’ […] The parents are burdened and worried, and they want to get a relief from all of this.” Regarding escalating teacher–parent conferences, mindfulness was considered as supportive: “For oneself to stay calm, while around you the roar begins. And it is very unpleasant when suddenly fifteen parents start shouting and predominating one another. Well, and then maybe to say: We simply stop this here now. We won’t get any further with this today.”

School leaders facing conflicts highlight the value of listening instead of reacting immediately: “There are really things that one would like to address very EXPLICITLY, because they were annoying. And, well, how important it is to stay in relation to the other. And to talk about that which is annoying in another situation.”

Another explains: “In my role, one is constantly under attack.” Instead of adopting a “defensive stance,” he could also “stay with in touch with myself,” first “exhale and let the others finish talking.”

The training modules were, furthermore, experienced as relaxing: “I was really dazzled by the speed in which I personally managed to calm down. […] I hadn’t calmed down since March 18th. I just had not! […]” She was “almost shocked” that such a level of relaxation was possible “due to practice or a moment in a safe space” and further reflected: “[…] we could have done this every day. But we didn’t.”

These results illustrate how relational competence, mindfulness, and compassion are main features of successful coping—as opposed to emotional shutdown (Vaes and Muratore, 2013)—disrupting stress-induced fight–flight–freeze mechanisms (Kabat-Zinn and Hanh, 2009) and enabling regulating one’s own and other’s emotions.

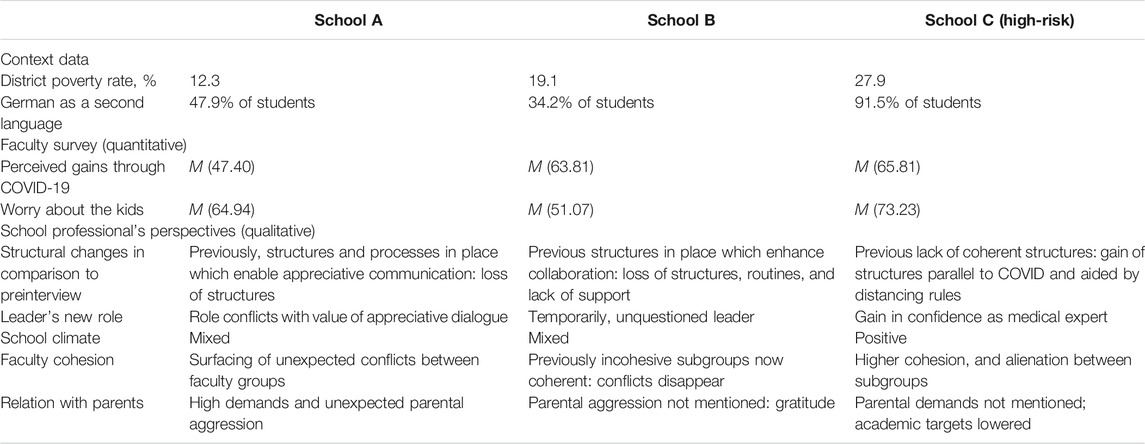

Overview of Differences Between Schools

Differences on the whole-school level become apparent when comparing the three schools. Table 1 presents an overview over context factors, survey results, and themes which were found to vary and differentiate among the three schools.

The domains in which the schools vary include equity factors, experienced positive aspects of the pandemic, structural changes, new roles, climate, cohesion, and relation to parents (see also Factors Driving Variation Between Schools’ Climate).

Discussion

The pandemic situation has broken up the school system’s structuring patterns and folders forcing its members—students, parents, pedagogues, and the principals—and their respective relationships with each other to break "new" ground. The goal of this article was to explore these changes as experienced by principals and pedagogues. We intentionally adopted an open focus including a variety of concepts and theoretical perspectives which allows us to capture multiple aspects and levels of these changes. Taken together, the data portrayed show how the relational atmosphere—the felt sense of what it was like to be in the schools—shifted in the phases of the response of the pandemic.

Social Field and System-Level Changes

School and Classroom Climate

According to a systems view of school climate, the overall climate is composed of a variety of subsystems which have their own climate (Rudasill et al., 2018)—nested social fields within a larger social field. As the following section suggests, the dynamics of the pandemic underlined this view in which they impacted these subsystems in very distinct ways—classrooms differently from faculties’ subgroups differently from parental households. What changed for these subsystems was both their structures or processes and their “textures” or the lived experience within them—along with the relation between subsystems’ actors. Again, we regard the observable system and the phenomenological field as two sides of the same coin. First, class sizes shrinked and the experienced classroom climate improved significantly—children felt seen and pedagogues enjoyed seeing them, indicating emotional support, positive affect, and low levels of irritability or anger—hence, a positive classroom climate (Buyse et al., 2008). Second, faculty was divided into different groups and rarely met physically—changes varied substantially between schools, with a new positive climate of connectedness, cohesion, and even enthusiasm for some, while others experienced more conflict along the lines of the preexisting division between the two subsystems of teachers on the one hand and after-school pedagogues on the other. Such conflicts among faculty illustrate the in-group and out-group dynamics often portrayed in relation to crises (Jonas and Mühlberger, 2017), and are also a well-known factor shaping school climate. Third, the changes in relation to parents were diverse, ranging from aggression and conflict to gratitude and a more personal, human contact. Taken together, we see that the subsystems relevant for school climate went through a multiplicity of significant changes.

Let us now turn to each school’s overall climate. For an investigation of how this was affected by COVID-19, we need to reflect on whether or not it is even possible to speak of a school climate in all phases of the pandemic response. The “affective and cognitive perceptions regarding social interactions, relationships,” etc., which define climate, were during lockdown largely absent, or present in the form of a perceived lack. Further, physical distancing heavily affected the constellations of interactions and relationships—with many “accidental” and “informal” interactions which had been important climate-shaping factors dropping away for all actors in school. Former publications have highlighted already this “missing” piece as a central theme (Beauchamp et al., 2020). Congruently, our interviewees named “school as a habitat” and “in-between nuances” which got lost. Thus, we indeed can speak of an overall school climate which during lockdown may have temporarily dissolved into its many components and was also later on largely lacking. However, the resultant overall climate was not only one of lack, but besides initial fear and alienation (“like a ghosthouse”), climate was also characterized by strong connectedness with those living through the same circumstances, and even “almost enthusiasm” in some special case. The good news is that in relation to children, the most consistent positive changes were reported (see Teacher-Student Relation).

This is in line with the understanding that social systems often respond to crisis with an increase in cohesion. Here, School B is an interesting case, since leaders in the preinterview mentioned a divisive atmosphere—next to also successful efforts of building trust. In response to the crisis, these conflicts disappeared as teachers turn toward each other to seek for support—acquiring a new balance between their separateness and communion (Marmarosh and Sproul, 2021).

Factors Driving Variation Between Schools’ Climate

Reports of an “almost enthusiastic” atmosphere in School C are particularly surprising and raise the question of what may be driving such experiences. Comparing school C to the other schools may hint at possible explanations. As Table 5 displays, the schools differed in a few domains, most prominently equity (the districts’ poverty rate in School C—a high-risk school) and the relationship to parents, but also organizational structures prior to the crisis. The latter were in School C marked by a lack of coherent structures, mentioned by the leaders in the preinterview as “chaotic.” Schools A and B on the other hand had many structures in place which supported their coherent functioning based on their values. When the crisis hit, schools A and B lost their structures, while School C was in a process of building new ones parallel to and aided by the crisis and its structuring elements (e.g., hygienic measures). Descriptively, also the survey data showed that School C professionals perceived more positive aspects of the pandemic than other faculties, but were also more worried about their disadvantaged children. Furthermore, School C’s professionals have mentioned parental aggression as an issue already prior to COVID-19. This was an unexpected experience for School A’s professionals. While School C’s professionals in their high-risk school with a significant language barrier (91.5% of students with German as second language) lowered their academic targets for their students due to the crisis (“achievement gap”), the parents in School A—in a more well-off district—demanded from school professionals to prevent their children from falling behind. This suggests once more that to understand climate, the structural and equity conditions need to be considered. The different initial conditions shaped each school’s course of change through the pandemic, and with it, the relational experience of living through the changes—the social field. For School C, these were to some extent quite positive. Another aspect is highlighted by the school comparison: The relationship to parents and the degree of parental pressure are important factors in shaping the COVID-19 response, and with it, the school’s social field. This role of external demands has also been highlighted in by other publications on the pandemic in schools (Beauchamp et al., 2020).

Impaired Interbodily Resonance

An overall pattern across system levels—alluded to by one interviewee—can be described as a “re-plotting” of the social field, narrowing the (subsystem’s) social field’s boundaries to the inclusion of fewer relations, while intensifying these remaining relations and at the same time losing an embodied experience of the whole school. This pattern is of course somewhat implicit in the distancing measures designed to limit the number of contacts. Therefore, it is even more important to understand better some of its effects. We suggest to consider a phenomenological perspective, which has described the interbodily resonance and body-related feedback loops in interpersonal interactions (Fuchs, 2017) as a base for empathy and a sense of connectedness, experiencing self and other as an extended body. Physical distancing and virtual communication impair these mechanisms—with effects on the overall quality of a social field (Fuchs, 2017) extensively described by our interviewees. What is more, one leader described a spillover effect, that is, physical distancing had the effect that people stopped greeting each other all together. This deserves close attention since it has implications for both virtual learning and successful crisis leadership which does not damage the relational system, as Kahn et al. (2013) suggested. The apparent lack of interbodily resonance, of touch, and direct contact (e.g., Szkody et al., 2020) needs to be compensated for rather than resigned to—for physical distancing not to become social distancing with loneliness and negatively skewed social perception spreading throughout the social network (Bzdok and Dunbar, 2020).

Interpersonal Relations

Leaders

Theory suggests that leaders have an important role in shaping climate and culture in times of crises (Kahn et al., 2013; Schein, 2017). To begin with, our findings highlight that the leaders themselves first had to adapt to and deal with the VUCA conditions and new demands they suddenly were confronted with (Hadar et al., 2020), foremost school leaders’ new role as crisis and safety managers. The adaptation to this new role and its effects on their relationships were different for the leaders. For School A’s leaders, the operating mode as crisis managers was conflicting with their value of dialogue and appreciative communication and was partly received critically by the faculty, while for School C’s leader, this operating mode entailed a gain in confidence as a medical expert, bringing about safety. The leaders’ different ways of adapting to the new demands may indeed have shaped climate, contributing to the differences between their schools. Previous studies found correlations between the teachers’ perception of principal effectiveness with better climate and perceived inconsistencies in leadership behavior with negative climate, respectively (Kelley et al., 2005). In this light, School A’s leaders’ role conflict may have been perceived as an inconsistency with their previous behavior of appreciation and dialogue. In contrast, School C’s leader’s acquired medical and legal expertize may speak to a perceived effectiveness.

Within one of the few existing publications on school leadership in times of COVID-19, the argument has been made that out of necessity, leaders rely on the practice of distributed leadership (Harris and Jones, 2020), which is based on networking and collaboration. Our findings only partly confirm this thesis. While collaboration has indeed been described, also a reduction of collaboration was mentioned since distancing measures require giving orders instead of dialogue.

An interesting aspect of leadership has been mentioned by Beauchamp et al. (2020) who found that principals were lacking the physical presence of the other community members, because “it allowed them to use the interactions as a way of gauging the more subtle moods of the community, and to triage these where necessary” (p. 10). Similarly, our interviewees mentioned a loss of “in-between nuances.” The role of this impaired interbodily resonance (Impaired Interbodily Resonance) and the—at least partial—disappearance of school climate for leadership needs to be further examined.

Taken together, findings could be interpreted in favor of Smith and Riley (2012) proposition that the leadership attributes and skills in times of crisis are fundamentally distinct from those generally required in “normal” school environment. Whether they are fundamentally different or not, the crisis situation does call on huge adaptation efforts. Our findings illustrate the massive impact of COVID-19 also on leaders and the school’s culture. Leaders are required to “step outside the culture that created the leader”, as Schein (2017) expresses it, to reflect on their own adaptation, how it reflects their values, and find ways of reconciling these with the situational demands. Our findings show that sometimes opportunities for positive change are to be found. We would further like to mention here that, as Harris and Jones (2020) point out, the continuous adaptation to these uncertain and unpredictable times also requires a great portion of self-care (see Social-Emotional Capacities: Strengthening Self-Regulation and Compassion).

Teacher–Student Relation

The pandemic surprisingly improved the learning environment in classrooms by reducing the class sizes. Positive effects of reduced class sizes on teacher–student relations, and on both students’ noncognitive development and academic achievement have been discussed (Konstantopoulos and Chung, 2009; Dee and West, 2011; Bosworth, 2014; Pipere and Mieriņa, 2017). The pedagogues in this study highlight that in the small group settings, children felt seen. This may play an important role in improving the relationships in the classroom. The classroom dynamics—as interviewees implied—were marked by a stronger polarization between, on the one hand, “difficult” children receiving a lot of attention and, on the other, calm children likely to be overseen. Due to COVID-19, with class sizes only half as big, children showed up in more balanced ways. The system found a new dynamic equilibrium. As Dee and West (2011) suggested, small class sizes increase the quality of the interaction or relation between pedagogue and each student. In smaller classes, pedagogues have more resources available for each student, such as time, attention, and empathic attunement. Hence, it is easier for pedagogues to act with relational competence, as defined by Juul and Jensen (2017), seeing each child on its own terms, and taking full responsibility for the quality of the relationship with each child. This extends the findings of Bergdahl and Nouri (2020), who had reported teachers’ surprise regarding a better contact to students even in online learning settings.

Our findings indicate that while most actors in the education system were under high stress struggling with a constant uncertainty, due to the divided classes, many students encountered just the right conditions to show up with improved social emotional skills.

It is not surprising that also the leaders and pedagogues highlight how they themselves enjoyed “witnessing” or “observing” the children’s development, to the extent that they were calling for a continuation of this small group learning setting. This may indicate what Boell and Senge (2016) call a generative social field, one in which the actors in the social field are mutually enriched by their interaction, grow new capacities, and flourish, experiencing a heightened sense of connectedness and awareness.

Social-Emotional Capacities: Strengthening Self-Regulation and Compassion

Under high stress levels, social emotional skills are key for adaptive coping (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984; Hadar et al., 2020). The participants’ reports show how practicing mindfulness can be a resource for self-regulation under VUCA conditions— “exhale and let the others finish talking” and “stay calm, while around you the roar begins.” Physiologically, these acts of self-regulation help the individual to regain balance and counter fight–flight–freeze mechanisms (Porges, 2015) (“staying in touch with myself” rather than being “defensive”). As such, this may help resolve conflicts (such as within escalating teacher–parent conferences). Furthermore, the individuals strengthen their ability to compassionately co-regulate others without losing their own ground, fostering positive connections throughout the whole social field. The survey results further speak to that point. Correlations between "getting something positive out of the situation" and, on the one hand, "being able to empathize with the kids" and, on the other hand, "maintaining a good contact with the kids" could be based on cultivating compassionate relationships which foster well-being both for self and other. Nonetheless, such interpretations need to be supported in the future by standardized operationalization, a larger sample, and more robust results.

Relational competence, after all, is also crisis competence. The crucial challenge is to reliably activate and practice mindfulness and compassion while confronting the urgent and ubiquitous stressors of the crisis—when practicing such qualities is, most likely, among the first things to be set aside. This is also a challenge for SEL research and practice (Hadar et al., 2020). How can social emotional learning be particularly supported while schools struggle with the daily base of COVID-19 conform schooling? The crisis can motivate for SEL—distancing and lockdown impressively demonstrate how essential social relations are for all of us. Supported by compassion and mindfulness, it is possible to maintain contact to oneself and one's values while allowing an authentic and compassionate encounter with others—colleagues and students–—to the point that the social field becomes generative, mutually enriching, and creative.

Limitations