95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 08 April 2021

Sec. Language, Culture and Diversity

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.618655

The relationship between language anxiety and self-determined motivation has been examined from various aspects in the applied linguistics domain. However, the direction of the relationship tend to disagree. Some studies report positive correlation whereas others (and in most cases) show negative correlation. To address this issue, the present study attempted to evaluate in depth the relationship between these two variables. We first qualitatively examined the types of language anxiety students face during learning, and then assessed how motivational variables based on self-determination theory can predict these identified types of anxiety. The results showed that sense of competence and relatedness negatively predicted certain types of anxiety while controlled motivation positively predicted only the general language anxiety. However, perception of autonomy and autonomous motivation did not predict any sub-types of language anxiety while sense of relatedness positively predicted psychological anxiety. The findings are discussed in terms of their theoretical and educational implications for language learning.

Many second language (L2) students experience a certain level of language anxiety that emerges from being involved with L2. Such feelings are challenging because they negatively affect learners’ engagement and involvement in language learning (Horwitz, 2001). Indeed, research shows that language anxiety is associated with English as a foreign language (EFL) learning and has academic as well as psychological implications (MacIntyre and Gardner, 1989; Alrabai, 2014; Oteir and Al-Otaibi, 2019). Thus, emphasis is placed on the relationship between language anxiety and L2 motivation. Within the framework of Self-determination Theory (SDT) the relationship between motivation and language anxiety tend to disagree (e.g., Noels et al., 2000; McEown et al., 2014; Alamer et al., 2017; Oteir and Al-Otaibi, 2019; McEown and Sugita-McEown, 2020). Such mixed results warrant further exploration of the relationship between these two key L2 psychological constructs. For example, whether specific type(s) of language anxiety positively (or negatively) predict certain type(s) of motivation is a critical issue to clarify because the results would lead to quite different recommendations about instructional implications and research agenda. Therefore, exploring different types of language anxiety students face and assessing the extent to which these sub-types predict motivational factors would enrich our understanding of how language anxiety relate to various motivational orientations.

Language anxiety is a situation-specific construct (Teimouri et al., 2019) such that specific types of anxiety may emerge among some students but not others. Therefore, language anxiety has been assessed qualitatively in this study. Upon understanding the types of language anxiety EFL learners exhibit, a quantitative exploration of how these sub-types of anxiety predict Students’ motivational orientations based on the SDT perspective was conducted.

Anxiety is an important variable directly related to success in language learning. Language anxiety “encompasses the feelings of worry and negative, fear-related emotions associated with learning or using a language that is not an individual’s mother tongue” (MacIntyre and Gregersen, 2012, p. 103). It is a psychological factor thought to be effective in determining the level of success in the language learning process (Dörnyei, 2005). Young (1992) describes anxiety in foreign language classrooms as a complicated process that cannot be easily assessed, but which inevitably affects L2 learning at different levels. Learning a foreign language entails social interaction with others (possibly native speakers) and takes into consideration the cultural aspects of the target language. Horwitz et al. (1986) included “communication apprehension” as one of the three components constituting language learning anxiety: it is associated with the fear of communicating with people, which might be reflected in a sort of shyness. The second component is “fear of negative evaluation”: learners avoid situations where they might be negatively evaluated or might not satisfy expectations of others; the third is “test anxiety”: learners might be anxious because of tests or academic evaluation. Nonetheless, the researchers asserted that language anxiety is more than the sum of these parts and should be treated as a complex learning construct that comprises beliefs, behaviours, and feelings inside and outside the classroom that result from the overall language learning process.

A recent systematic review of language anxiety considers anxiety a challenging issue in language learning and suggests that researchers should aim for its complete understanding (Oteir and Al-Otaibi, 2019). The review also identifies the effects of language anxiety on language learning and groups them into five broad categories based on how they affect the students: academically, socially, cognitively, affectively, and personally. Specifically, the review indicated that when learners express levels of language anxiety they tend to exhibit low academic performance. Further, they appear to be less interested in social interaction using the L2. In addition, high anxiety prevents information from reaching learners’ cognitive processing system, and thus, losing an important portion of language acquisition. Furthermore, because anxiety is an affective construct its impact on other affective variables (such as attitudes and self-confidence) can be observed. Finally, language anxiety affects learners’ personality by making anxious learners more miserable, worried, forgetful (Oteir and Al-Otaibi, 2019).

Further, a recent meta-analysis (Teimouri et al., 2019) has shown the association between language anxiety and language achievement among 105 different samples with roughly 20,000 sample size. The meta-analysis revealed a medium negative correlation between the variables (r = −0.36). It was also noticed that the strength of the relationship fluctuates depending on situations such as educational levels, target languages, and types of language anxiety. Alrabai (2014) observed that the major fears of Saudi EFL learners were related to language classroom settings. Specifically, learners indicated that they get nervous about forgetting what they already know, go blank when they try to say something without preparation, and feel panic when they are asked by their language teacher to reply using English. Alamer (2021b) also noted that learners with controlled type of motivation appear to be less passionate about learning the L2 over a period of whole semester. Furthermore, a recent study by Alamer and Lee (in press) has investigated the directional relationship between language anxiety and L2 achievement over time. Their study has shown that, contrary to the common belief, it is language achievement that predicted language anxiety and not the other way round. In addition, their study provided some evidence that autonomous motivation was acted as a moderator between the variables, such that with a high endorsement of autonomous motivation high achievers students become less anxious about their learning of the L2.

SDT proposes that different orientations of motivation can be delineated by varying degrees of self-determination expressed as impersonal, external, somewhat internal, and internal (Alamer and Lee, 2019; Alamer, 2021a). Thus, the influence of each motivational orientation on language learners may be positive or negative. There are four different orientations that belong to two general types of motivation. First, intrinsic orientation reflects the pleasure and enjoyment the learner feels in learning the language. Second, identified orientation represents the learner’s feeling that language learning aligns with the values in his/her life. These two orientations form a more general type of motivation called autonomous motivation. Introjected orientation refers to the internal pressure driven by social obligations such as feelings of guilt and shame if the learner fails in learning the language. Fourth, external orientation reflects the learner’s intention to learn L2 because of tangible or intangible rewards or to avoid negative consequences. The motivation formed by these last two orientations is called controlled motivation. Several studies have empirically confirmed these four specific orientations and the two general types of motivation (Gagné et al., 2010; Oga-Baldwin and Nakata, 2017; Ryan and Deci, 2017; Alamer and Lee, 2019; Alamer, 2021a).

Further, several studies within the language learning domain have shown that autonomous motivation is associated with positive learning outcomes, including increased engagement (McEown et al., 2014; Oga-Baldwin and Nakata, 2017; Noels et al., 2019), BPN satisfaction (Noels, 2013; Alamer et al., 2017; Alamer and Al Khateeb, 2021), metacognitive awareness (Vandergrift, 2005), presentence and intended effort (Noels et al., 1999; Noels et al., 2019), perceived usefulness of language (Parrish and Lanvers, 2019), and ultimately, the greater attainment of language (Noels et al., 1999; Oga-Baldwin et al., 2017; Alamer and Lee, 2019). Moreover, these studies show that controlled motivation is associated with negative linguistic and non-linguistic outcomes, including a decrease in L2 achievement, self-confidence, willingness to communicate, frequent use of language and speaking fluency, and motivational intensity.

In addition to the motivational orientations described above, SDT (2000, 2020) posits that individuals strive to develop an environment where their Basic Psychological Needs (BPN) of autonomy, competence, and relatedness are met. From SDT perspective BPN are the essential components for learners to grow and endorse autonomous motivation. In this way, autonomy refers to a learner’s need to feel agency over his/her action. Competence refers to a learner’s feeling of being effective and competent in the learning process. Relatedness refers to the feeling that the learner is connected to and receive care from others. Researchers argue that when these needs are satisfied, L2 learners are expected to act autonomously to learn the language effectively (Noels et al., 1999; Gagné and Deci, 2005; McEown et al., 2014; Alamer and Lee, 2019; Alamer, 2021a; Alamer and Al Khateeb, 2021).

Research has shown that L2 learners with satisfied basic needs flourish, engage in, and achieve the language more effectively than learners with frustrated basic needs (Noels, 2013; Alamer et al., 2017; Oga-Baldwin et al., 2017; Noels et al., 2019; Alamer, 2021a). These findings extend support to Alamer and Lee (2019), who studied the relationship between BPN and learning emotions and found that more self-perception of BPN was moderately and strongly associated with positive life and study emotions, respectively. Further, the researchers indicated that both competence and autonomy were negatively correlated with life and study fear emotions, whereas more self-perception of relatedness was associated with higher levels of both life and study fear emotions (Alamer and Lee, 2019). This result is unexpected, but research provides no clear explanation of why this is the case. The present study may provide further knowledge in this area by including different types of language anxiety in the assessment.

Self-determined types of motivation are often assessed with language anxiety to understand how these factors interrelate to inform the learning process. However, empirical studies investigating the relationship between the two factors have indicated mixed results (e.g., McEown et al., 2014; Alamer et al., 2017; Alamer and Lee, 2019; McEown and Sugita-McEown, 2020). For example, social anxiety might influence learners’ autonomy and consequently, language learning. Zhou (2016) showed that students who experienced fear of public speaking—as a sign of social anxiety in language learning—perceived lower BPN and were less autonomously motivated, although the negative correlation was rather low in magnitude. Similar results were obtained from McEown et al. (2014) who found that intrinsic motivation positively predicted scored in language anxiety. However, other studies have provided strikingly different results emphasising that autonomous motivation is significantly associated with increased language anxiety (McEown et al., 2014; McEown and Sugita-McEown, 2020). Further, past research have consistently indicated that controlled motivation has a positive correlation with language classroom anxiety (Noels et al., 1999; McEown and Sugita-McEown, 2020; Alamer, 2021b). These contradictory results may be attributed to different reasons such as research design or the socio-educational context of the study.

A more detailed study of the relationship among BPN, SDT-based motivational orientations, and language anxiety was conducted by Alamer and Lee (2019), who reported that language anxiety was negatively associated with autonomy and competence, whereas, it had an unexpected positive association with relatedness. The researchers concluded that the Saudi socio-educational context might influence Students’ mindset about receiving feedback from others as implying low confidence of the learner, thus resulting in an increased feeling of language anxiety. Zhou (2016) observed that social anxiety did not correlate with controlled motivation, and only negatively correlated with self-autonomous motivation, thus, affecting classroom learning orientation. In conclusion, the investigation into the relationships between these variables has not been well understood, and further empirical research is needed.

The literature review indicates that the relationship between language anxiety and motivation requires further exploration. One way to achieve this is to explore the types of language anxiety students experience during L2 learning and explore the association between these anxiety types and BPN and SDT-based motivational orientations. Thus, the present study aims to qualitatively identify the types of language anxiety EFL students face during L2 learning in order to unpack what make learners anxious. The study then quantitatively examines how BPN and SDT-based motivational orientations predict different types of anxiety. Thus, the present study follows the dominance research design (Cohen et al., 2013), in which the qualitative part is conceptualised as a starting point for the major part (i.e., the quantitative part). To this end, the study attempts to answer one research question:

RQ: How do BPN (i.e., autonomy, competence, and relatedness) and SDT-based motivational orientations (autonomous motivation and controlled motivation) predict the emerged types of language anxiety?

Participants were invited to participate by filling out a questionnaire that consists of quantitative and qualitative parts. These parts are explained in the following parts.

Respondents were asked through open-ended questions to express what language anxiety concerns they face while studying English. Students were asked three questions that were included at the end of the questionnaire:

(1)- What difficulties (if any) do you face in the college language learning experience?

(2)- Have you experienced any kind of pressure that made language learning difficult? If yes, mention some of them.

(3)- Were anxiety or fear from failure barriers in your language learning experience? How?

Open-ended questions allow students to elaborate on their points (Cohen et al., 2013). Further, they provide a far greater richness than fully quantitative data in exploring the number and types of themes of the phenomena under investigation (DonYei, 2007). Data are presented thematically and Students’ responses are analysed and discussed using the framework proposed by Horwitz et al. (1986). Students responses were analysed and discussed under the themes to which they belong. Respondents anxiety appeared to fall under the following categories: language proficiency anxiety, contextual anxiety, psychological anxiety, and social anxiety.

To evaluate the relationships between language anxiety and BPN and SDT-based motivational orientations, logistic regression analysis was conducted using JASP (2020). Logistic regression analysis allows researchers to deal with categorical variables in a regression model in which the predicated variable is categorical (such as types of anxiety), whereas predictor variables can be continuous. We, thus, attempted to identify whether BPN and SDT-based motivational orientations could predict the specific types of anxiety that emerged from the qualitative analysis. Students who expressed one of the four identified types of anxiety were coded as (1), and those who expressed no such behaviour were coded as (0) in the analysis. For precise results, Cohen et al. (2013) indicate that beta (β) values of predictor variables can be used as effect sizes, such that β values between 0–0.10, 0.10–0.30, 0.30–0.50, and > 0.50 are indicative of weak, modest, moderate, and strong effect sizes, respectively. Effect sizes are used in addition to the significance test (i.e., p-value) because the latter is perceived as limited in providing detailed information about the magnitude of the association or prediction among the variables (Hair et al., 2014). To evaluate instrument reliability, McDonald’s composite reliability (ω) was considered in addition to Cronbach’s α. This estimate assesses the magnitude of association between variables and their error terms. Thus, composite reliability accounts for the extent to which different observed variables represent the general construct (McDonald, 1970).

Participants were 134 EFL Saudi undergraduate students studying English at a public Saudi University. Generally speaking, the way of delivering the content of the language courses can be described as didactic where students rely heavily on teachers’ lectures to learn the subject (Alrabai, 2014). Typically, students in the university listen to the lectures, take notes, and follow their teachers’ direct instruction, though some teachers may show some supportive-teaching style (Alamer and Lee, in press). Therefore, teachers teaching styles would have a noticeable effect on their Students’ anxiety and motivation and are generally similar to the other universities in the country (Alamer and Lee, 2019). For example, students are required to complete eight semesters which usually consume 4 years to get a Bachelor’s degree in English language and Translation. It should be noted that data collection took place in 2019 [before the spread of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19)]. Participants ages ranged from 18 to 24 years (M = 21.2, SD = 1.03), and 57% of the participants were male. The university review board approved the study and granted permission to collect data from the students. An invitation message was sent to all students via a Telegram channel dedicated to sharing news and important announcements with the students. Participants were invited to participate by clicking on and completing an online questionnaire. Those who were unwilling to participate were asked to simply refrain from visiting the link or completing the online questionnaire after they started taking it.

The questionnaire consisted of four parts. Part one concerned items that assessed Students’ BPN: 12 items from the BPN-L2 scale (Alamer, 2021a) were used, which elicits self-report about Students’ satisfaction of the basic needs for autonomy (4 items), competence (4 items), and relatedness (4 items). The answers were rated on a five-point Likert scale. Example items are “I am able to freely decide my own pace of learning in English” for autonomy; “I feel I am capable of learning English” for competence; and “My English teacher cares about my progress” for relatedness (Cronbach’s α = 0.73, composite reliability = 0.76). The second part consisted of 12 items taken from Alamer (2021a), which assess Students’ SDT-based motivational orientations based on two general types of motivation: autonomous and controlled. Beginning with the instruction, “think of why are you learning English and then select the extent to which you agree with the following statements,” students were asked questions that reflected autonomous and controlled motivation. Answers to these questions were rated on a five-point Likert scale. Example items are “because I enjoy learning English” for autonomous motivation; “because I would feel ashamed if I am not successful in English learning like my friend/family” for controlled motivation (Cronbach’s α = 0.80, composite reliability = 0.79). The third part focussed on overall language anxiety as explained by Gardner (2010): 10 items elicit self-report about Students’ language anxiety on a five-point Likert-type scale. Example item is “I never feel quite sure of myself when I am speaking in our English class” (Cronbach’s α = 0.88, composite reliability = 0.86). The fourth part was an open-ended question that asked the participants whether they felt anxious while L2 learning.

Construct validity was assessed using exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM) (see Alamer, in press for a review). Robust diagonally weighted least squares method was used for estimating the model because the data were deemed ordinal. A measurement model including BPN, SDT, and language anxiety as observed variables that belonged to six latent variables was considered and tested. The results of this comprehensive measurement model provided a good fit to the data (χ2 = 241.033, df = 213, p = 0.09, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, GFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.03, RMSEA 90% CI: [0.00, 0.05], SRMR = .09). Two error terms were allowed to covary between items: external 1 and external 3 as well as introjected 2 and introjected 3. These covariances were expected because the items from the same constructs were possible tapping into common aspects that observed variables did not capture.

This section aims to address barriers reported by the participants in their English learning experience. The responses of the students varied; while some learners appeared not to be facing difficulties, others reported various encountered obstacles. The major barriers faced by the students can be classified under social, psychological, L2 proficiency, and other contextual and academic barriers.

Some participants reported social barriers, while two others agreed with the existence of social barriers but preferred not to tell what the barriers were; some argued that social pressure comes primarily from friends, followed by family members and finally teachers. While family members tend to push their children toward success and hard work to avoid failure, learners appear to feel pressure when they themselves compare their performance with other students. “Yes, those around me are better in English,” a participant argued. Another said, “I compare myself with others around me, and that makes me disappointed.” In contrast, one participant shared her suffering, arguing that she had no “friends” in class and that “I feel alone.” Thus, friendship in the classroom can motivate, but might also cause social pressure. A third participant reported hearing a few negative words from some teachers. Although it was reported as a social barrier, it might also be related to communicative competence.

When asked whether anxiety and fear of failure might be an obstacle to fluency in English, some learners argued that concerns such as losing a second chance to study the courses again, anxiety causing attention deficit, and lack of co-operative colleagues in the class might obstruct learning. “I was diagnosed with anxiety by a psychiatrist but I don’t think it affects learning English but it affects me in a different way such as the fear of failure,” said one of the learners. Others added, “when I fear, I cannot focus” and “fear and anxiety control me, make me depressed, and thus I can’t study and understand.”

Further, one participant explained that “teachers mentioning failure makes learners nervous, frustrated, and therefore they can’t perform well.” It is therefore necessary that learners become motivated. “If we don’t get motivated and supported, of course, we might have troubles more than just anxiety and fear,” one of the learners argued. Remarks such as “my ambition is to learn English, and if I fail, I will be terminated to another department” and “my marks will determine my future whether to continue in the department or not” indicate that students might be forced to focus on how to pass than how to learn. “I will just focus on passing,” one participant argued, with others explaining that they would not get promoted to the English department if they did not pass the language courses. This pressurises students to learn to pass. “Learning can’t be enjoyed under pressure,” said one female learner. Although such pressure may motivate students to study hard, over worrying may lead to unwanted results. “It would affect my performance in the finals and reduce productivity,” said one participant. On the other hand, a few learners appeared to successfully channelise such kind of pressure. “It is natural that we worry and fear,” said one, while the other argued, “this anxiety should be deployed as a motive for studying harder.”

Data showed that some learners faced difficulties related to their language proficiency. Participants reported problems with spelling, new terminologies, grammar, the accent of some instructors, and the books being for advanced learners. “We are being taught as advanced learners, although many of us don’t know the basics,” argued a participant, whereas another student blamed teachers for their focus on advanced learners only. Further, a few participants criticised instructors for not using their first language.

Some learners also reported a lack of focus, clarifying that when many skills need to be learned at the same time, they get nervous and consequently cannot perform well. Another learner adds, “I am afraid of failure because of some non-English required courses.” Other students have highlighted that elective courses are one of the reasons to feel anxious about the language levels getting low. One learner says “elective courses taught in Arabic are too much and they prevent me from focusing on the language studies.”

College requirements therefore appear to create additional pressure on students.

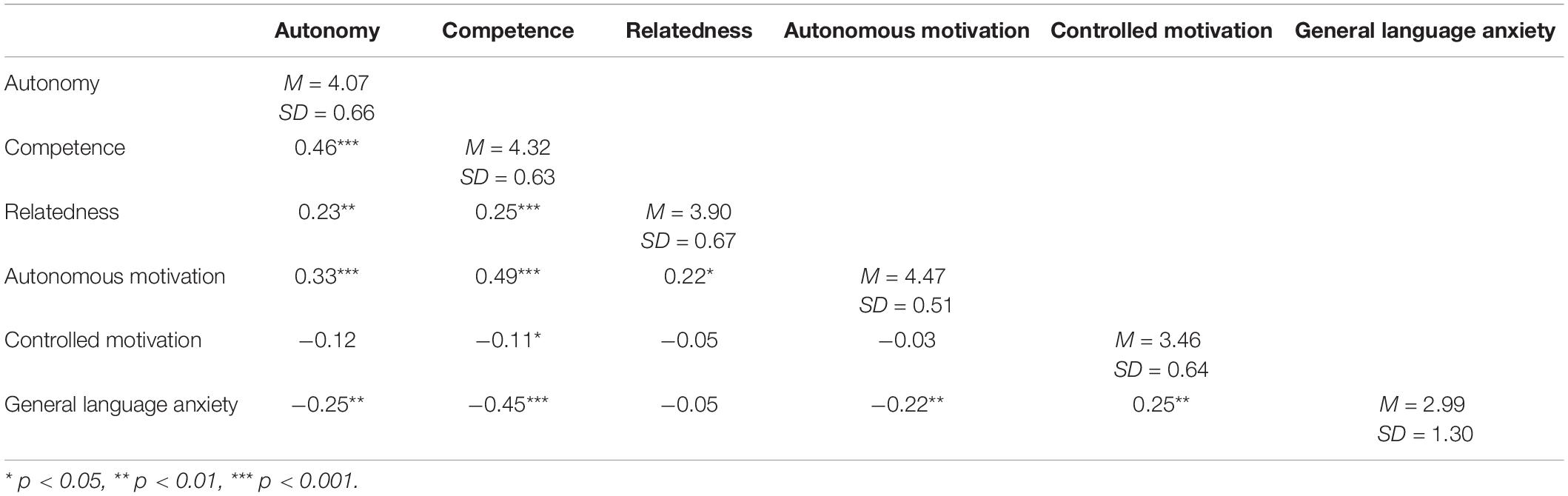

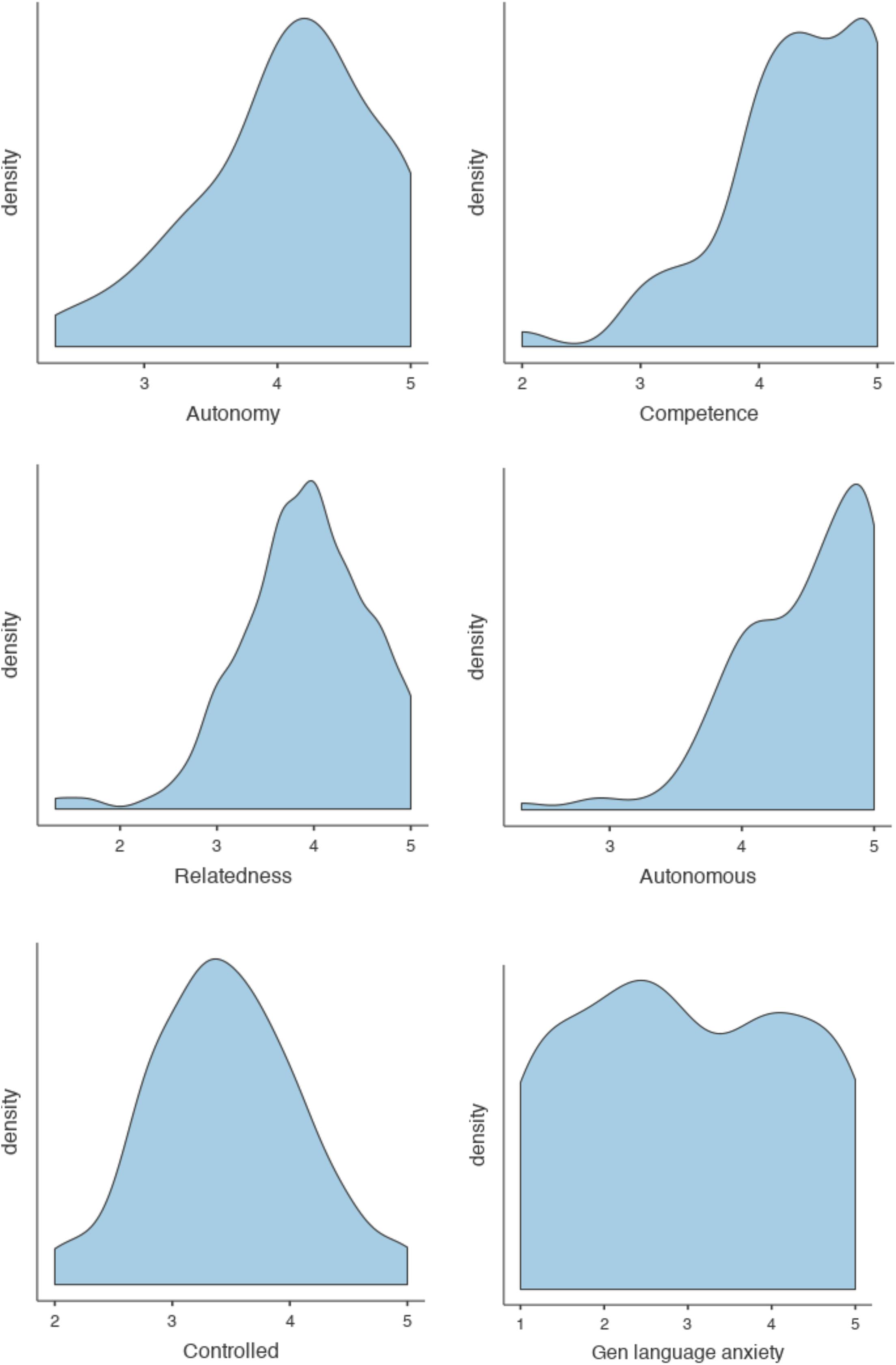

Means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations of the study variables are presented in Table 1. In Figure 1, histogram density is presented to show the patterns participants exhibited when responding to variable items. It also helps in determining the univariate outliers as well as the skewness of the data. Inspecting these histograms, it turns out that our data is not normally distributed. Thus, an alternative correlation test to Pearson (r), namely Spearman’s rho (ρ), is used, which assesses the strength of the relationships when normality is not achieved. The results indicated that BPN significantly correlated with autonomous motivation, with competence showing the strongest association. However, only competence (among the BPN) negatively correlated with controlled motivation. With regard to language anxiety, controlled motivation was positively related to language anxiety, whereas autonomous motivation had a negative association. Among the BPN variables, competence and autonomy were negatively correlated with language anxiety, whereas relatedness appeared to show non-significant correlation.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations Spearman’s rho (ρ) between the variables.

Figure 1. Histogram density of study variables. Autonomous, autonomous motivation; controlled, controlled motivation; Gen language anxiety, general language anxiety.

Table 2 shows the results of the logistic regression models in which the three BPN variables and two SDT orientations were set as predictors of the emerged types of anxiety. Model 1 presents the results of prediction of social anxiety, and the model fit measures revealed that the model explained only 7% of the variance in social anxiety, as indicated by the R2McF value. Further, only relatedness significantly but negatively predicted social anxiety (B = −0.96, CI 95%: [−1.83, −0.10], p = 0.02). That is, the more the need for relatedness is satisfied among the students, the less they feel socially anxious. None of the variables reached statistical significance. Model 2 presents the results pertaining to the prediction of psychological anxiety, which explained around 10% of its variance. Specifically, competence was found to be significantly but negatively predicting psychological anxiety (B = −1.33, CI 95%: −2.55, −0.14, p = 0.02), whereas relatedness was observed to positively predict psychological anxiety (B = 1.03, CI 95%: 0.02, 2.11; p = 0.05). Model 3 reveals the results wherein achievement anxiety was set as a predicted variable and the model explained approximately 6% of the variance in achievement anxiety, as shown by the R2McF value. Nonetheless, the result showed that competence was the only significant but negative predictor of increased achievement anxiety (B = −1.33, 95% CI [−1.76, −0.03], p = 0.04). Model 4 reflects the results for the contextual anxiety variable, but the model showed a weak explained variance of the variables (R2McF value = 0.01). This weak explanatory variance was reflected in the marginal coefficients, as they were not statistically significant. Therefore, no motivational variables predicted contextual anxiety. Finally, Model 5 presents a linear regression analysis assessing the extent to which the motivational variables can predict general language anxiety. The model explained 24% of the variance in general language anxiety. Further, perceived competence was the only negative variable among BPN that predcicted general language anxiety (B = −0.80, CI 95%: [−1.22, −0.38], p < 0.001). Satisfaction of relatedness and autonomy failed to predict general language anxiety. With regard to SDT-based motivational orientations, it was observed that only controlled motivation positively predicted increased general language anxiety (B = .38, CI 95%: [0.04, 0.73], p = 0.04), whereas autonomous motivation failed to explain significant variance in general language anxiety.

The purpose of the present study was to qualitatively explore the types of anxiety students encounter while learning English as an L2. The study also assessed how satisfaction with BPN (autonomy, competence, and relatedness) and the two general motivational orientations of SDT (autonomous motivation and controlled motivation) predict the experienced sub-types of anxiety. Since previous research in language learning within SDT have provided little consensus on the relationship between language anxiety and motivational orientations (McEown et al., 2014; Zhou, 2016; Alamer et al., 2017; Alamer and Lee, 2019; McEown and Sugita-McEown, 2020), the present study aimed to offer a clearer understanding of the relationship between these two key psychological variables and how motivational variables predict different forms of anxiety among L2 students.

The qualitative results revealed four types of language anxiety among the participants: social, psychological, proficiency-related, and contextual. These sub-types of language anxiety partially conform with those found by Horwitz et al. (1986); however, the present study provided some important qualitative details. Socially, some students reported fear of communication, especially with friends and less frequently with family members. This kind of fear (e.g., Horwitz et al., 2010) seems to be related to evaluative situations, that is, learners’ fear of unsatisfying expectations of classmates or significant others. Thus, classroom context appears to be inevitably evaluative. This form of anxiety resonates with introjected orientation, a form of SDT motivational orientation, in which learners may feel motivated by social and inner pressures (Noels et al., 2000; Alamer et al., 2017). L2 teachers can minimise this experience by, for example, making sure that there are no pre-set expectations, and encourage learners participate, even if they are likely to commit language mistakes. It might also be beneficial for teachers to make students aware of the fact that committing mistakes is inevitable in the learning situations, and thus, there is no reason for such fear in social participation. If other students seem to be causing such pressure, teachers should prevent such situations by implementing an appropriate disciplinary rule. Engagement of students in such social situations may result in an unlikely suffering of language anxiety (Dewaele and Al-Saraj, 2015).

Another factor that many students seemed concerned with was the fear of failure and psychological anxiety. Some students reported general fear from engaging in the classroom and expressed feelings of pressure. It is, thus, important for teachers to prepare students psychologically by making them aware of how to positively channelise their anxieties (Horwitz, 2001). Further, it is important for parents to encourage their children and avoid putting pressure on them by mentioning failure. Although teachers are required to continuously assess and evaluate Students’ performance, it is also important to substitute the consequences of failure by clarifying the good scenarios following their success. This may help to relieve language learners’ psychological anxiety and provide them with sufficient motivation to proceeds in learning in the face of challenges.

Participants in the present study appeared to report one common type of anxiety: proficiency-related anxiety. This is not surprising because many students, especially in the context of Saudi Arabia, are test-oriented (Alrabai, 2014); thus, they may be anxious about the exams and test in their language courses. Here, L2 teachers can support students by increasing their self-perception of language competence and facilitating a desire to learn through a lifelong learning approach. Teachers should stress that final marks are more about the progress the students have made than a judgement of their language competencies. This type of anxiety can be encountered by increasing Students’ competence needs, as suggested by previous studies (Noels et al., 1999; Zhou, 2016; Ryan and Deci, 2017; Alamer and Lee, 2019).

Students also shared different types of anxiety which can be combined under contextual anxiety. In several cases, students may express short-term negative emotions or mood that is related to the immediate learning situation (MacIntyre and Gregersen, 2012). Contextual anxiety is less critical compared to the other three types of anxiety because the latter are long-lasting and require deep cognitive and metacognitive strategies to address. Nonetheless, contextual factors could be minimised by initiating open regular discussions about the course, class environment, and the types of language tasks being given to the students, so that Students’ voices can be heard, eventually decreasing their contextual anxiety (Ryan and Deci, 2000).

An important finding of our study is related to the robustness of the motivational variables in predicting the above mentioned types of language anxiety in addition to the general language anxiety. Overall, results of the BPN variables revealed that relatedness negatively predicted social anxiety but positively predicted psychological anxiety, and competence negatively predicted psychological, achievement, and general language anxiety. Further, results of SDT motivational orientations showed that only controlled motivation positively predicted general language anxiety. Nonetheless, no variable predicted contextual anxiety. These results partially support previous research findings, explaining the role motivation plays in determining Students’ level of anxiety (Noels et al., 2000; Alrabai, 2014; Alamer et al., 2017; Alamer and Lee, 2019). Most importantly, by exploring the emerging types of language anxiety and setting BPN variables as well as SDT motivational orientations as predictors, the current study further clarifies the relationship between these sub-constructs. However, our results contradict other empirical studies that observed a positive association between general language anxiety and autonomous motivation (McEown et al., 2014; McEown and Sugita-McEown, 2020). The correlational analysis in the present study indicated that autonomous motivation was negatively associated with general language anxiety, but it did not predict any sub-types of language anxiety. A possible explanation for this finding could be attributed to the nature of the language being learned. Studies reporting a positive association between language anxiety and autonomous motivation often used languages other than English in their evaluation of the association, whereas the present study used English as the target language. Although these previous studies did not provide direct interpretation of their results, one could postulate that learning English is far more common than any other language. Hence, it appears that Students’ feelings of enjoyment and interest allowed the participants of the present study to experience less language anxiety, especially inside the classroom. As the same time, studying languages other than English seem to entail a specific level of anxiety even when enjoyment and interest are experienced. However, the present study showed that relatedness predicted greater endorsement of psychological anxiety. This is similar to findings of Alamer and Lee (2019) who showed relatedness was positively correlated with L2 life and study fear. However, these results are not very encouraging because they contradict the claim that the basic need for relatedness is one of the three needs that are essential for learning and expanding knowledge. The results suggest that those who felt connected with and cared for are likely to suffer from psychological obstacles that are inherent in the learning process, such as language ability and beliefs about one’s aptitude in achieving the language. However, further work is required to establish this link.

Our study has important implications for research on language motivation and anxiety. First, since relatedness was noticed as a predictor of lower social anxiety, there is a possibility that students who receive sufficient support from their language teachers appear to feel socially confident. In other words, the care they receive from people around them in the language and social context makes students more relaxed while engaging in and practising the language. Therefore, L2 teachers should provide their students with important psychological needs (i.e., relatedness) and connect well with them in order to understand them. Second, self-perception of competence is a significant predictor of lower endorsement of achievement and psychological anxiety. This is not surprising, given the significant position competence occupies in L2 motivation literature (e.g., Noels et al., 1999; Ryan and Deci, 2000, 2020; Oga-Baldwin and Nakata, 2017; Alamer and Lee, 2019; Noels et al., 2019).

Moreover, the findings suggest that competent L2 learners are less likely to suffer from and display anxiety related to the learning process; they are more likely to feel capable of achieving the language than those with less perception of self-competence. As the results show, psychological anxiety that might arise from engaging in different language tasks could affect those who feel less efficient in learning the language. In addition, self-perception of competence was found to be a negative predictor of general language anxiety. Therefore, L2 teachers should inspect their Students’ perception of competence as it explains why some students experience greater stress about their ability to attain the language and psychological anxiety related to their learning process. In short, this variable explains several others variables in the present study. Thus, L2 teachers should emphasise the fact that learning entails a specific amount of effort that may translate into achievement later on, and that the commonly held belief among L2 students that only aptitude explain successful achievement is not necessarily true. This may allow the students to appreciate and reflect on their perception of competence, although such a reflection may take time to sink in. Lastly, one of the issues that emerge from our result is the positive prediction of controlled motivation for general language anxiety. That is, students who decided to learn the language to gain external rewards and benefits, or simply engage in the language tasks to impress the teacher and satisfy other people’s desires are more likely to feel anxious while learning the language. Since learning the language has not yet been internalised optimally within Students’ sense of selves, students seem to feel anxious about the language and its learning tasks.

It can also be postulated that the combination of language anxiety and controlled motivation will prevent students from acquiring the language smoothly (Zhou, 2016; Oteir and Al-Otaibi, 2019). This is a clear opportunity for teachers to minimise the endorsement of controlled motivation among their students. They can, for example, remind the students about the internal reasons for learning L2 and how this endeavour could be fruitful for their personal improvement and growth. Students are to be reminded that getting rewards or jobs in the future should not be the main driver of their learning but its by-product because this form of motivation makes them vulnerable to increased language anxiety. Although there is nothing wrong with planning to achieve high marks in the language courses, students often feel enticed by these external motivators and forget the intrinsic reason for learning; hence, teachers can regularly check Students’ motivation and remind them about the reasons behind learning and studying.

The main aim of the present study was to determine how language anxiety is associated with language motivation. To obtain a clearer perspective, we first qualitatively explored potential aspects of language anxiety among the participants. We then set different types of motivation based on the SDT theoretical framework as predictors of the different types of language anxiety. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to determine the association between these variables using this approach. Therefore, the present research extends our knowledge of the relationship between BPN and SDT orientation and language anxiety and provides educational implications for learning and teaching. Taken together, these results confirmed findings of some previous studies but contradicted those of others and serve as a basis for future empirical studies on these two key L2 psychological factors.

Finally, a number of important limitations must be presented. First, the present study has only explored the relationship between language anxiety and motivation. Other key variables can be included in future research to determine how the larger set is interrelated. This can include language learning strategies, learning effort, willingness to communicate, and language achievement. In addition, the study’s participants are only Saudi learners. Thus, no generalisation can be made outside of this context. However, future research might examine the role of these psychological variables and how they affect each other, and the learning outcomes outside of Saudi Arabia for comparison purposes. Further, a more comprehensive study linking these variables in a hypothetical structural model can be a useful step toward a fuller understanding of the interrelationship between language motivation and anxiety.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Imam Mohammed Ibn Saud Islamic University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

AA contributed toward the quantitative parts while FA contributed toward the qualitative parts. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Alamer, A. (in press). Exploratory structural equation modeling in second language research: the case of the dualistic model of passion. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach.

Alamer, A. (2021a). Basic psychological needs, motivational orientations, effort, and vocabulary knowledge: a comprehensive model. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. doi: 10.1017/S027226312100005X

Alamer, A. (2021b). Grit and language learning: construct validation of grit and its relation to later vocabulary knowledge. Educ. Psychol. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2020.1867076

Alamer, A., and Al Khateeb, A. (2021). Effects of using the WhatsApp application on language learners motivation: a controlled investigation using structural equation modelling. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2021.1903042

Alamer, A., and Lee, J. (in press). Language achievement predicts anxiety and not the other way around: a cross-lagged panel analysis approach. Lang. Teach. Res.

Alamer, A., and Lee, J. (2019). A motivational process model explaining L2 Saudi students’ achievement of English. System 87:102133. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2019.102133

Alamer, A., Lee, J., and Vigentini, L. (2017). “The relationship of motivation and emotion with second language learning,” in Proceedings of the Applied Linguistics Conference (ALANZ/ALAA/ALTAANZ), Auckland.

Alrabai, F. (2014). A model of foreign language anxiety in the Saudi EFL context. Engl. Lang. Teach. 7, 82–101.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2013). Research Methods in Education, 8th Edn. London: Routledge.

Dewaele, J. M., and Al-Saraj, T. M. (2015). Foreign language classroom anxiety of Arab learners of English: the effect of personality, linguistic and sociobiographical variables. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 5, 205–228. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2015.5.2.2

Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The Psychology of the Language Learner: Individual Differences in Second Language Acquisition. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. doi: 10.4324/9781410613349

Gagné, M., and Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 26, 331–362. doi: 10.1002/job.322

Gagné, M., Forest, J., Gilbert, M. H., Aubé, C., and Morin, E., and Malorni, A. (2010). The motivation at work scale: validation evidence in two languages. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 70, 628–646. doi: 10.1177/0013164409355698

Gardner, R. C. (2010). Motivation and Second Language Acquisition: The Socio-Educational Model, Vol. 10. Language as Social Action. New York, NY: Peter Lang Inc.

Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., and Anderson, R. (2014). Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th Edn. London: Pearson Education Limited.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., and Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. Mod. Lang. J. 70, 125–132.

Horwitz, E. K., Tallon, M., and Luo, H. (2010). “Foreign language anxiety,” in Anxiety in Schools: The Causes, Consequences, and Solutions for Academic Anxieties, ed. J. C. Cassady, (New York, NY: Peter Lang Inc), 95–115.

JASP (2020). JASP (Version 0.13.1) [Computer software]. Available at: https://jasp-stats.org

MacIntyre, P., and Gregersen, T. (2012). “Affect: the role of language anxiety and other emotions in language learning.” in Psychology for Language Learning, eds S. Mercer, S. Ryan, and M. Williams, (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 103–118. doi: 10.1057/9781137032829_8

MacIntyre, P. D., and Gardner, R. C. (1989). Anxiety and second-language learning: toward a theoretical clarification. Lang. Learn. 39, 251–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1989.tb00423.x

McDonald, R. (1970). The theoretical foundations of principal factor analysis, canonical factor analysis, and alpha factor analysis. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 23, 1–21. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8317.1970.tb00432.x

McEown, K., and Sugita-McEown, M. (2020). The role of positive and negative psychological factors in predicting effort and anxiety toward languages other than English. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2020.1767634

McEown, M. S., Noels, K. A., and Chaffee, K. E. (2014). “At the interface of the socio-educational model, self-determination theory and the L2 motivational self-system models,” in The Impact of Self-Concept on Language Learning, eds K. Csizér and M. Magid, (Bristol: Multilingual Matters), 19–50. doi: 10.21832/9781783092383-004

Noels, K. (2013). “Learning Japanese; learning English: promoting motivation through autonomy, competence and relatedness,” in Foreign Language Motivation, eds M. T. Apple, D. Da Silva, and T. Fellner, (Bristol: Multilingual Matters), 15–34. doi: 10.21832/9781783090518-004

Noels, K., Clément, R., and Pelletier, L. (1999). Perceptions of teachers’ communicative style and students’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Mod. Lang. J. 83, 23–34. doi: 10.1111/0026-7902.00003

Noels, K., Pelletier, L., Clément, R., and Vallerand, R. (2000). Why are you learning a second language? Motivational orientations and self-determination theory. Lang. Learn. 50, 57–85. doi: 10.1111/0023-8333.00111

Noels, K., Lascano, D., and Saumure, K. (2019). The development of self-determination across the language course: trajectories of motivational change and the dynamic interplay of psychological needs, orientations, and engagement. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 41, 821–851. doi: 10.1017/s0272263118000189

Oga-Baldwin, Q., Nakata, Y., Parker, P., and Ryan, R. (2017). Motivating young language learners: a longitudinal model of self-determined motivation in elementary school foreign language classes. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 49, 140–150. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.01.010

Oga-Baldwin, Q., and Nakata, Y. (2017). Engagement, gender, and motivation: a predictive model for Japanese young language learners. System 65, 151–163. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2017.01.011

Oteir, I. N., and Al-Otaibi, A. N. (2019). Foreign language anxiety: a systematic review. Arab World Engl. J. 10, 309–317. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol10no3.21

Parrish, A., and Lanvers, U. (2019). Student motivation, school policy choices and modern language study in England. Lang. Learn. J. 47, 281–298. doi: 10.1080/09571736.2018.1508305

Ryan, R., and Deci, E. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.55.1.68

Ryan, R., and Deci, E. (2017). Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

Ryan, R., and Deci, E. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 61:101860. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Teimouri, Y., Goetze, J., and Plonsky, L. (2019). Second language anxiety and achievement: a meta-analysis – erratum. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 41, 489–489. doi: 10.1017/s0272263119000445

Vandergrift, L. (2005). Relationships among motivation orientation, metacognitive awareness and proficiency in L2 listening. Appl. Linguist. 26, 70–89. doi: 10.1093/applin/amh039

Young, D. J. (1992). Language anxiety from the foreign language specialist’s perspective: interviews with Krashen, Omaggio Hadley, Terrell, and Rardin. Foreign Lang. Ann. 25, 157–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.1992.tb00524.x

Keywords: language anxiety, L2 motivation, self-determination theory, basic psychological needs, emotions, mixed methods, nonparametric tests, logistic regression

Citation: Alamer A and Almulhim F (2021) The Interrelation Between Language Anxiety and Self-Determined Motivation; A Mixed Methods Approach. Front. Educ. 6:618655. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.618655

Received: 17 October 2020; Accepted: 15 March 2021;

Published: 08 April 2021.

Edited by:

Marco A. Bravo, Santa Clara University, United StatesReviewed by:

Jenelle Reeves, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, United StatesCopyright © 2021 Alamer and Almulhim. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abdullah Alamer, YWEuYWxhbWVyQGtmdS5lZHUuc2E=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.