- Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies, Indiana University Bloomington, Bloomington, IN, United States

The COVID-19 pandemic has prompted a variety of responses by organizational leaders throughout the United States and internationally. This paper explores the responses of five rural school superintendents who work in a conservative Midwestern state. Using an exploratory qualitative research design, the study analyzes interviews and documents collected remotely to adhere to current public health guidelines. The study adopted a crisis leadership perspective to explore how rural school superintendents were responding to the COVID-19 pandemic and managing the politics associated with it. Findings suggest that superintendents were acutely aware of their community’s current political stance toward the COVID-19 pandemic and were especially responsive to the individual political philosophies of their elected school board members. The superintendents did not uniformly adopt crisis leadership behaviors to respond to the circumstances created by the pandemic. Rather, superintendents responded in ways that managed the political perspectives held by their elected board members and sought to reconcile differences in the board members’ political perspectives that precluded action. As part of this reconciliation, the superintendents leveraged public health information to shape and at times change elected school board members’ perspectives. This information helped the superintendents overcome political perspectives that led some of the most conservative board members to resist widely accepted public health guidance. Implications for the field of educational leadership, research on rural superintendents, and potential revisions to superintendent preparation are discussed.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has prompted a variety of leadership responses throughout the United States and internationally. The popular media has chronicled how leaders in government and the public sector have taken actions to address the threats posed by one of the worst public health crizes on record. These accounts broadly suggest that “leaders have reacted to the COVID-19 pandemic in ways that vary dramatically” (Crayne & Medeiros, 2020, p. 1). Local context, including their local politics, often surrounds their reactions. News reports, which offer the most current coverage of the pandemic, suggest that leaders’ reactions to the pandemic have ranged from swift intervention designed to address social and economic challenges (Kealey, 2020) to more politically nuanced responses that have sought to minimize the severity of the situation (Phillips, 2020). In other contexts, leaders have sought to frame the pandemic as a “hoax” (Egan, 2020) and thereby undercut public health officials and scientifically-based guidance. Unsurprisingly, these actions have galvanized public perceptions about the threats posed by the pandemic and have created favorable and unfavorable conditions for leaders to respond to the public health crisis. Clearly, schools and school districts experience these conditions. Indeed, at least in the United States, schools and districts have faced inconsistent state and federal leadership during the initial closure of and subsequent reopening of public services. This study seeks to understand how superintendents working in public school districts have responded to the significant challenges introduced by the pandemic.

In this exploratory study, I focused exclusively on rural school superintendents and sought to understand how they have responded to the challenges posed by COVID-19 within their unique context. The scholarly literature and popular press have not paid particular attention to these leaders nor fully explored the impact of the pandemic in rural contexts. This is somewhat surprising as nearly half of all U.S. public schools are located in rural communities and enroll approximately one-quarter of the nation’s public school students (Snyder et al., 2019). Rural superintendents serve as important actors in the broader education system and their responses to the pandemic have significant consequences for the health and well-being of their communities. This seems especially true as scholars have documented pronounced inequities in rural areas related to education, healthcare, and economic opportunity prior to the onset of the pandemic (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2017). These inequities seem particularly vexing as public health experts at one point projected that an influx of COVID-19 cases could potentially cripple rural health infrastructure (Fehr et al., 2020). The public health crisis has thus intensified the pressures already placed on rural leaders, especially superintendents, as it has introduced new threats to an already overtaxed segment of American society. How superintendents in rural communities initially managed and have continued to manage the public health crisis thus represents a critical question as the rural political context has likely shaped the availability of resources, programs, and support for specific actions. Indeed, prior research suggests that superintendents working in rural schools already faced unique political pressures prior to the pandemic (Budge, 2006; Farmer, 2009; Preston et al., 2013). This study presumes that these conditions merit closer examination given the onset of COVID-19.

To complete this study, I interviewed five school superintendents working in rural school districts in a politically conservative Midwestern state. I focused on the superintendents’ initial responses to the pandemic (i.e., their leadership in March and April 2020) and their later efforts to safely reopen schools (i.e., their leadership in July and August). I informed my interpretation using crisis theories of leadership (DuBrin, 2013). Crisis leadership is defined as “the process of leading group members through a sudden and largely unanticipated, intensively negative, and emotionally draining circumstance (DuBrin, 2013, p. 3). Scholars have applied this perspective to prior work on public education, most notably in relation to natural disasters and school shootings (Mutch, 2015). Crisis leadership explains actions and reactions of leaders in unpredictable and uncertain times. I used this perspective to explore how the superintendents in these rural districts have responded to the pandemic. The paper unfolds with a brief review of the literature related to educational leadership in rural settings. Within this review, I also note recent discussions about leaders’ reactions to the pandemic. Next, I describe the research methodology I used to complete this exploratory study. Finally, I present my research findings and conclude the manuscript by offering implications for supporting and training leaders.

Literature Review

Given how rapidly events related to COVID-19 have unfolded, research on educational leaders’ responses to the pandemic is presently very limited. Scholars have only recently begun to publish research that describes the impact of COVID-19 on the work of school leaders. For example, Harris (2020) noted that the pandemic has shifted the work practices of school leaders toward greater use of distributed, collaborative, and networked leadership actions. Stone-Johnson and Weiner (2020) emphasized the professionalism that principals have exhibited during the pandemic and suggest that understanding how to cultivate this important leadership quality could contribute to principal retention during these challenging circumstances. Hayes et al. (2020) describe the work of rural school leaders during the pandemic in rural schools located in a southeastern state. They noted that principals have engaged in caretaker leadership as their schools have navigated the challenges associated with the pandemic. Finally, Lowenhaupt and Hopkins (2020) considered the leadership that principals might provide to immigrant communities amidst the challenges of the pandemic, noting the importance of asset based thinking, connections with parents and families, supports for school staff, and connections with other resources. Broadly, these studies suggest that the pandemic has had a significant impact on leaders and their practice and has fundamentally altered work routines that have previously defined leaders’ responses to common educational challenges.

Though less prevalent in the scholarly literature, scholars have also given attention to the pandemic’s influence on superintendents and school districts. For example, Starr (2020) noted that superintendents initially focused on meeting the immediate educational and nutritional needs of their schools at the onset of the pandemic and have yet to consider the long-term consequences the pandemic might have for the delivery of public education. The popular press and internet blogs have also attempted to describe educational leadership during this important period and reported on the perspective of superintendents. In one article published by School CEO magazine, Lifto (2020) described a survey of Minnesota superintendents’ responses to the pandemic. While the study had a limited sample size, it suggested that 78% of respondents to the survey lacked preparation to respond to the pandemic and its effect on their school districts. Further, 72% of respondents to the survey indicated that their school districts could not easily switch to distance delivery or online learning. These findings speak to the unexpected and unforeseen challenges associated with the pandemic that many superintendents are likely facing. Indeed, superintendents who responded to the survey pointed to the difficulty preparing and supporting teachers for distance learning, the challenges associated with the rapid implementation of online learning platforms, and infrastructure issues in schools and communities that functioned as significant barriers to the delivery of educational services to students during the pandemic.

Other studies conducted by professional associations point to the significant financial costs associated with reopening schools with necessary safeguards and personal protective equipment. For example, the Association of School Business Officials and American Association of School Administrators, jointly estimated that it will cost an average size district approximately $1.8 million to cover expenses related to health monitoring and cleaning protocols, staffing, personal protective equipment, and transportation (Association of School Business Officials, 2020). Superintendents will undoubtedly shape these decisions as they fit within a superintendent’s responsibility as the district’s senior fiscal steward. Surprisingly, the challenges facing rural superintendents have not received substantial attention in the popular media. The discussion which has appeared has predominately focused on the limitations of rural broadband internet access (Wang and McCoy, 2020). Indeed, limitations of rural broadband appear to disproportionately impact low-income and special education students (Kamentz, 2020). Yet, broadband internet access is only one of the many issues confronting superintendents in rural settings.

In my view, the pandemic has also raised important questions about education governance, as well as the leadership practice of superintendents related to their elected boards. The pandemic has introduced fundamental shifts related to a superintendent’s approach to, interactions with, and efforts to inform their board members. Prior research has documented that school districts function in a unique governance structure that links citizens to the work of professional administrators and educators (Wirt and Kirst, 1997; Feuerstein, 2002; Timar and Tyack, 1999). Indeed, superintendents serve as important actors in the education governance system in that they make important, high-level decisions about the vision and mission of the school district, policies related to the district’s program of teaching and learning, as well as the allocation of resources that support organizational activities (Björk and Gurley, 2005; Kowalski, 2005). Beyond their internal responsibilities, however, school superintendents also function as brokers between the professional staff in the district and the elected school board members (Howley et al., 2014). This role involves mediating politics within the district’s formal organizational structure, as well as managing political influences in the broader community (Björk and Gurley, 2005; Howley et al., 2014). Some of the political influences that confront superintendents might be engendered by the personal and political perspectives of school board members (Blissett and Alsbury, 2019). These perspectives can contribute to differing senses of urgency in relation to specific governance issues as well as explain the varying positions of school board members (Blissett and Alsbury, 2019). Unsurprisingly, this research suggests that superintendents must deliberately choose which issues to address given individual beliefs, organizational circumstances, and the decision-making culture that they wish to create through their leadership actions (Touchton et al., 2012). COVID-19 has likely altered some of these circumstances and introduced changes to the decision-making context for superintendents. As such, the pandemic presents an opportunity to better understand how the governance structures and relationships are changing due to the public health crisis. A central question thus concerns how superintendents manage the politics associated with the public health crisis given the availability of resources, programs, and political support from their board.

Research on Rural Educational Leadership

Compared with research focused on urban and suburban settings, research on educational leadership in rural school districts is a relatively small and somewhat dated body of research. One review of literature focused on rural education, found that between 1991 and 2003 issues related to educational leadership were addressed less frequently in the rural literature than studies focused on programs for students with special needs as well as research examining instruction, school safety, predictors of academic achievement, and students’ attitudes or behaviors (Arnold et al., 2005; O’Malley et al., 2018). More recently, Preston et al. (2013) reviewed published research from 2003 to 2013. The authors noted that rural school leaders (e.g., school principals) face significant challenges that often begin at the time of their initial hiring and continue throughout the work to include other issues such as the diversity of their work responsibilities, limited opportunities for professional learning, discrimination, and broader difficulties related to school accountability and change. The authors contend that “to be successful, rural principals must be able to nimbly mediate relations within the local community and the larger school system” (p. 1). This conclusion reflects rural school leadership under normal circumstances and does not consider what skills or dispositions leaders must draw upon when navigating a public health crisis as severe as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Literature on rural school principals offers some insights into the actions that leaders might take and challenges they might encounter under ordinary circumstances. For example, much of the recent literature has focused on the job responsibilities of rural principals, as well as the contextual factors surrounding rural schools (Acker-Hocevar and Ivory, 2006; Arnold, et al., 2005; Taylor and Touchton, 2005; Budge, 2006; Acker-Hocevar, et al., 2009; Farmer, 2009; Hyle et al., 2010; Preston, et al., 2013). Preston et al. (2013) determined that rural school principals face a complexity of roles, lack of professional development, gender discrimination, rising pressures related to accountability, and resistance to school change. While their findings focus on school principals, it is not difficult to hypothesize that these findings might also describe the work of rural superintendents. Budge (2006) conducted research on rural principals and found that they perceived their leadership involved unique challenges that were deeply embedded within the rural community context. These challenges related to the students they serve as well as the kinds of expectations that parents and families have for their children. Though situated in one district context, the study provides important insights into the nuances and particularities that define leadership in rural settings as well as the extent to which leadership action reflects the unique rural community context. Parallel research has more recently characterized the challenges facing rural superintendents as being both about the ongoing threat of school district consolidation, increasing racial, ethnic and linguistic diversity in rural communities, and new uses for the development of rural farmland (Howley et al., 2014). Farmer (2009) studied the politics of rural communities and determined that political factors, especially related to financial challenges, influenced leaders’ actions. Resource inequities in rural schools have been well-documented in the school finance literature (Tompkins, 2019). These inequities likely contribute to the challenges rural leaders have encountered during the pandemic.

Research on Rural Superintendents

Though not situated within rural contexts, much of the recent discussion about the superintendency has sought to differentiate superintendent leadership from that of their school-based peers. The scholarship positions the superintendency as a largely political role given expectations that superintendents manage the politics and political agendas found in their communities (Leithwood, 1995). Scholars contend that superintendents face internal and external conditions that create instability for leaders in this important position (Kowalski, 2005). Indeed, research suggests that the position requires that the individual who occupies it be adept at identifying potential conflicts among stakeholders and mitigating them in order to support their district’s instructional mission. Superintendents in rural communities may be even more subject to politics in their communities given they may be the district’s only administrator. Regardless of their setting, superintendents must perpetually navigate “turbulent environments involving elected boards, faculty and staff, community stakeholders, and fiscal constraints” (Tekniepe, 2015, p. 1). Indeed, political disagreements between superintendents and the school board are common even in the most mundane or ordinary circumstances. Scholars have also sought to define the role of the superintendent as an instructional leader (Petersen and Barnett, 2005). This work has sought to distinguish the role from the more conventional conceptions of instructional leadership found within individual schools. Petersen and Barnett (2005) sought to describe the instructional leadership behaviors of superintendents. Scholars have also pointed to the operational and financial responsibilities that distinguish the superintendency from other leadership positions in education (Kowalski, 2005).

In contrast with discussions about rural school principals, rural superintendents have received comparatively less attention in the research literature. McHenry-Sorber and Budge (2018) claimed that “the contemporary rural superintendency is a practice in need of a theory” (p. 1). This characterization reflects both the limited understanding about rural superintendents leadership practice as well as the limitations of current leadership theories to fully describe how their unique context shapes their work. Scholars have attempted to describe how superintendent leadership practice differs across educational settings, including within the context of rural schools (Lamkin, 2006; Alsbury and Whitaker, 2007; Hyle et al., 2010). Notably, Lamkin (2006) studied the challenges faced by rural superintendents and determined that rural superintendents faced challenges related to school law, finance, personnel, government mandates, and policies passed by the school board or enacted by the district. She and other scholars argue that these challenges are similar regardless of a superintendent’s position in a rural, suburban, or urban setting (Manasse, 1985; Leithwood and Montgomery, 1986; Stephens and Turner, 1988; Chance, 1999). However, both Howley et al. (2014) and Lamkin (2006) observed that rural superintendents faced some unique challenges that were more broadly associated with the cultural or normative expectations associated with leading primarily rural schools as well as the unique organizational and fiscal arrangements associated with rural school districts. As Lamkin (2006) noted, rural superintendents often engage in diverse administrative activities with less support. Thus, she concluded that rural superintendents faced challenges that do not substantively differ from their peers but more likely differ in terms of “scale and intensity” (p. 6) of the problems confronting them. The challenges facing rural superintendents are thought to be “faster, deeper, longer, and more public” (p. 6) given the rural context. This likely reflects the fact that in many rural districts, superintendents are one of very few, if not the only, administrators employed in the district office. This point appears to be supported in more recent research by Hyle et al. (2010), who observed that superintendents in small and rural settings may find their job responsibilities are fluid and in constant negotiation due to the size of their district. One significant limitation of the current literature relates to the ways in which rural superintendents manage crizes and respond to public health concerns.

A Working Framework: Perspectives on Crisis Leadership

In seeking to understand superintendent leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to consider theories that describe leadership during times of crisis. Prior research has considered crisis leadership within the context of schools, particularly its managerial aspects (Lichtenstein, et al., 1994; Decker, 1997; Kibble, 1999; Brock et al., 2001; Smith and Riley, 2012; Mutch, 2015). This research has largely investigated school leaders’ responses to crizes within the context of natural disasters and school shootings (Mutch, 2015). Muffet-Willett and Kruse (2008) observed that crisis leadership often requires leaders to employ knowledge and skills that are beyond those typically required in their daily work. As such, they contend that crisis leadership is a unique form of leadership. Crisis leadership is generally defined as “the process of leading group members through a sudden and largely unanticipated, intensively negative, and emotionally draining circumstance” (DuBrin, 2013, p. 3). The COVID-19 pandemic clearly constitutes a sudden disruption in the daily work of educational leaders. Scholars contend that communication is considered central to crisis leadership in that it assists individuals in making sense of and becoming clearer about the implications that the crisis has for their organization (Hackman and Johnson, 2013; Hesloot and Groenendaal, 2017). As Liu et al. (2020) argued, leadership is fundamentally a “communicative act” and within the context of a crisis it is a central responsibility of leaders to project clarity in an environment defined by uncertainty. Indeed, Liu et al. (2020) suggested that crisis leadership depends heavily on a leader’s ability to establish presence, develop relationships, and engage in inter-organizational coordination. In a study specifically considering leaders’ response to COVID-19, Crayne and Medeiros (2020) found that leaders who are responding to the COVID-19 pandemic exhibit leadership behaviors that are charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic. In the case of public schools, pragmatic leadership may be especially applicable as it defines how leaders take information from the surrounding environment and make strategic decisions given the circumstances. A central proposition in this study is that superintendents will engender the qualities of pragmatic crisis leadership in order to bring stability and clarity to their districts.

Methodology

I completed this exploratory qualitative research study to understand the perspectives of rural superintendents who were engaged in leadership at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. I situated my investigation at the district level and sought to understand how superintendents responded to the COVID-19 pandemic and prepared for the safe reopening of schools. The study addressed the question: How are rural school superintendents responding to the crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic and the politics associated with it, if at all?

Research Setting and Participants

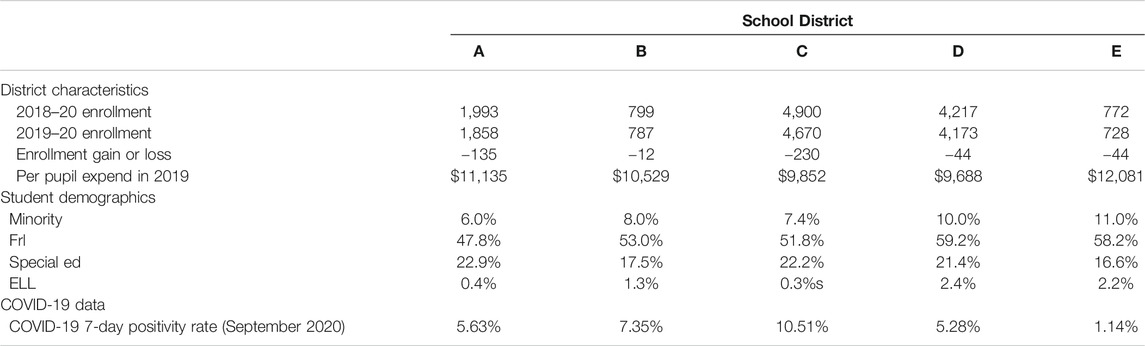

I constructed a purposeful sample (Patton, 1990) of five superintendents employed in rural school districts located in a politically conservative Midwestern state. I used the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) definition of a rural school district to locate participants for this study. Per the NCES definition, each of the districts was located more than five miles from an urban/suburban area and therefore was considered either rural-distant or rural-remote according to the NCES classification guidelines (Geverdt, 2015). As illustrated in Table 1, the districts ranged in size from 728 students to 4,670 students. All of the districts were experiencing student enrollment losses, which is a common feature of rural school communities. Between 6.0 and 11.0% of the district’s total student population were identified as students of color. Between 47.8 and 59.2% of the districts’ total student population were identified as economically marginalized based on their eligibility for free or reduced priced meals. Finally, between 16.6 and 22.9% of the districts’ total student population received special education services and between 0.4 and 2.4% of the districts’ students received supplemental language instruction. The 7-days average for COVID-19 positivity ranged from 1.14 to 10.51% in September 2020 when I collected data for this study.

Research Participants

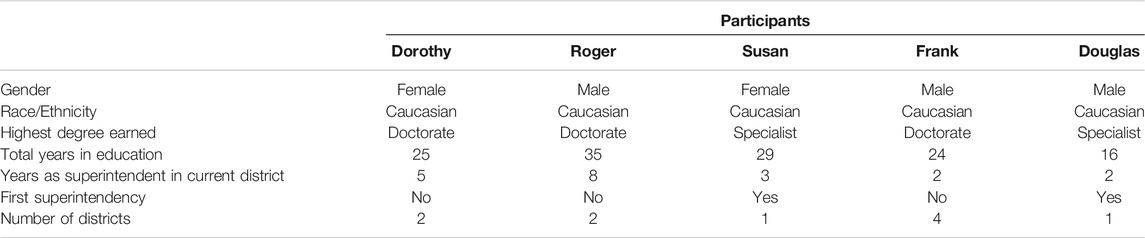

As illustrated in Table 1, the superintendents I interviewed included three men and two women. All of the participants in this study were White, which reflects the majority of superintendents employed in the state. Three of superintendents held a doctorate in educational administration, leadership, or a related field at the time of their interview. Two of the superintendents were pursuing their doctorate in educational leadership. The superintendents had between 16 and 29 years of experience in public education and had completed between two and eight years of service as a school superintendent in their current school district. Two of the superintendents were in their first superintendency. To protect the identity of the participants, I assigned a pseudonym to each participant interviewed.

Data Collection

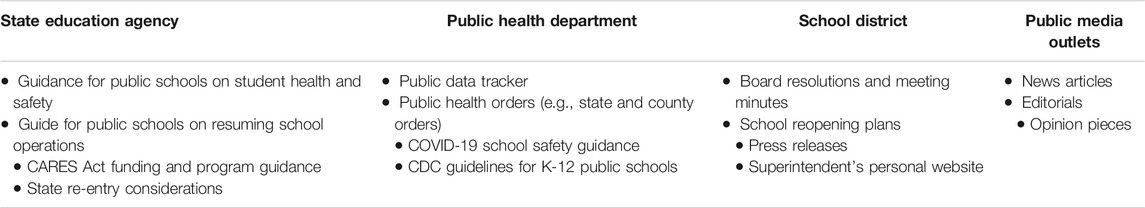

To complete this study, I conducted interviews via Zoom and collected online materials from the school district’s website, state department of education, county and state health department, and from news articles published in the regional and state newspaper. The study did not include onsite observations. In-person observation was not possible given public health considerations, as well as travel restrictions imposed on faculty by my university.

Semi-Structured Interviews

In September 2020, I conducted one semi-structured interview with each superintendent. The interviews ranged from 47 to 65 min in total length. I used a common interview protocol that asked the participant to describe their initial response to the COVID-19 pandemic, their interaction with stakeholders in their communities (e.g., school board members, parents, county health department, etc.) throughout the pandemic, and their plans for re-opening schools in the 2020–2021 academic year. I asked questions, including: “How did you respond when the COVID-19 pandemic initially impacted your school district?”, “What steps did you take to address the needs of low-performing students and/or students with special learning needs?”, and “How are you preparing to re-open schools in the 2020–2021 academic year given current public health conditions and guidance?” Additionally, I probed for specific examples that illustrated how the superintendents were responding or asked them to recall specific instances where they felt the pandemic prompted them to engage with key stakeholders differently.

Document Collection

To augment my interview data, I collected documents related to COVID-19 that were publicly available on the school district’s website, as well as news articles, editorials, press releases, and formal health guidance from the state and county department of health. The documents provided important contextual information about the communities, districts, and health risks both at the onset of the pandemic as well as in the lead up to school reopening. As illustrated in Table 2 retrieved 36 publicly available documents for this study, including each school districts reopening plan and remote learning plan. Given these documents were all available online, I retrieved them in Adobe PDF format.

Data Analysis

Given the small size of the data set and exploratory nature of the study, I chose to conduct a thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006). I began by transcribing the audio recordings of my interviews. Next, I manually coded each of the interviews and documents. Consistent with Saldana’s (2015) suggestions for coding, I structured my coding process in two distinct cycles. In the first cycle of coding, I focused on assigning single word descriptors or short phrases to passages of text. The codes were largely descriptive words or phrases that were low inference and intended to identify salient data points, perspectives, comments, or actions for further analysis. My intent at this stage was to begin reducing the dataset in preparation for the development of categories and themes that were more responsive to the research questions and aligned to the conceptual framework I adopted. In the second round of coding, I applied codes that related to the concepts of crisis leadership and management, which I derived from theoretical framework. These codes related to behaviors that literature suggests were indicative of a leader engaging in crisis leadership or management. To produce categories from the codes, I sought to identify (un)related codes that defined how leaders operationalized crisis leadership and management in their school districts during the initial school closure and in anticipation of school reopening. I then derived five themes by looking for (un)related and categories that could be logically and consistently grouped in ways that were responsive to my research questions.

Limitations

As an exploratory study into the leadership actions and responses of school superintendents during the COVID-19 pandemic the study is limited in sample size and thus narrow in participant perspectives. Many superintendents were simply unable to schedule an interview due to the demands on their time related to the pandemic or requested that the interview be delayed until after school reopened. To compensate for the small sample size, I sought to include diversity in the participants based on their professional experience, tenure in district, as well as complexity of the district’s organizational structure. This meant including superintendents who were both veteran district leaders as well as those who were new to the superintendency. I also included districts that served predominately rural communities (i.e., those without a major town or city) and districts that included a combination of rural and quasi-urban spaces. An additional limitation related to the absence of observational data to independently corroborate findings. Public health guidelines did not allow for on-site observation and limited infrastructure within the districts meant that key meetings and public events were not available via video. To compensate, I drew upon news articles, press releases, and other publicly available documents. While an imperfect substitute for in-person observation, these documents provided useful context and served as an important part of my effort to triangulate the observations and perspectives shared by my participants. Finally, I found that many of the school districts’ websites did not provide current information or posted information that linked to sources that were either no longer active or out of date. Thus, I emailed the superintendents for updated information and/or to retrieve documents pertaining to the pandemic.

Findings

My analysis suggests that superintendents were adjusting their leadership in response to the pandemic. Thematic analysis produced five themes. First, superintendents noted significant changes in the focus of their leadership practice. Second, the pandemic changed decision-making processes and forced superintendents to recalibrate what information was used to influence stakeholder perspectives. Third, superintendents noted increasing division and disagreement among previously stable political actors in relation to decisions about health and safety protocols. Fourth, superintendents employed public health information in order to address disagreements. Finally, differences in public health guidelines prompted varied responses to pandemic as well as different degrees of engagement. I discuss each of these themes in greater detail below.

Changing Focus in Leadership Practice Due to COVID-19

The superintendents described their work prior to the pandemic as being fundamentally about managing their board and the politics related to the personal perspectives of elected board members. To this end, their work focused on district issues that related to budget management, school litigation, community relations, and to a lesser extent the district’s teaching and learning practices. This was supported in documents posted on the district’s websites, as well as reflected in blog posts written by the superintendents. Prior to the pandemic, much of their public commentary focused on issues that had little relation to public health. For example, board meeting agendas and minutes in one district described topics such as issues related to collective bargaining, forthcoming litigation, and upcoming conversations about the consolidation of two small elementary schools. In another school district, the superintendent’s public webpage focused on an update about construction at their county’s largest high school. This focus reflects the state of the superintendent’s daily work prior to the onset of the pandemic. The superintendents corroborated this perspective in their interviews, as well. For example, Frank, a superintendent in his second year with his district noted, “The board didn’t used to ask me much about healthcare before this started, but they sure did want to know what we are spending our dollars on, balancing the books, or looking good for the state tournament.” This sentiment was similar across the five participants.

The onset of the pandemic profoundly shifted the superintendents’ work and invited new questions that they had not previously considered. These shifts reflected an abrupt departure from their standard work practices. Currently in his eighth year as a superintendent, Roger noted, “My work has changed so drastically because of this whole thing. I am now mostly assisting on issues related to COVID-19, covering teaching, doing [contact] tracing, and I’m not doing anything that I used to do.” Frank echoed this perspective as he had observed that his focus was now on daily or weekly issues about which he previously spent very little time. As Frank noted, “I’m focused on this week or maybe next week because of how fast this is all changing. On a daily basis I’m asking which teachers are going to show up sick, who needs to go home and quarantine, whether we’ll have coverage in the classrooms or lunch time.” Dorothy described the circumstances as forcing her to learn about aspects of the district that were not familiar to her and to acquire information that she had previously delegated to the district’s nursing staff. As Dorothy recalled,

We started getting information quickly at the beginning and it was all foreign. It was completely new to me. I used to rely on the nurse for her opinion and she would tell me what I needed to know. But the amount of information we are getting … it has really required me to get more involved and to learn about things that I haven’t. What superintendent is reading about things like community spread, viral transmission, social distancing guidelines, and quarantine guidance? That’s literally what I am reading now because that’s what I need to be familiar with to do this job. It’s honestly become a welcome distraction for me when I can talk about teaching and learning because there isn’t much of that now!

In sum, these comments reflect the with rapid adjustment that the superintendents attributed to the pandemic as well as the new learning the pandemic demanded in their work. The pandemic necessitated that superintendents learn new skills, adopt new foci, and prioritize different issues than they might have previously.

Pandemically-Driven Disruptions in Familiar Decision-Making Processes

Beyond disrupting the focus of their work, the pandemic also disrupted familiar decision-making processes, most notably the stakeholders who were engaged and the information used to shape stakeholders’ political perspectives. Superintendents broadly described that the pandemic had impacted their relationship with the board and found that political perspectives of their board members played an important role in shaping how their responded to the crisis. Notably, I found that the rapid onset of the pandemic disrupted the familiar dynamic they had established with their school board. As Roger noted, “I feel like the board has been supportive but they aren’t all in agreement with us like they used to be.” The pandemic also introduced new actors, such as public health authorities and medical professionals, who were previously not part of the superintendent’s decision-making process nor had significant influence on their board members’ perspectives. As Dorothy noted, “The pandemic has really changed who sits at my table when I make a decision. It used to be my principals, treasurer, and folks on the operational side. Now, when I make a major decision, I have the county health director on the phone, the nurse is in here, and I have a member of the board who is a family medical doctor.” As Roger noted, “At first, I was reaching out to our county health director almost daily getting updated information and asking for direction.” Frank and Susan echoed this sentiment noting that they had worked closely with their county health director and local medical professionals.

The superintendents also noted that state officials, particularly the Governor and public health commissioner, had acquired added importance in their post-pandemic decision-making. The superintendents reported that many decisions about public health were now being made by the state and communicated directly to county health departments. As such, beyond changing the decision-making actors, the pandemic also disrupted longstanding traditions around the local control of public schools. This ran counter to values in four of these communities which stressed the importance of making decisions aligned with the needs, political perspectives, and norms of the community. This shift demanded that superintendents be willing to take actions that their community members did not always fully support and that their board members often strongly opposed. As Doug, a superintendent in his second year noted, “We have long believed that we make decisions here, but I am now spending a lot more time explaining to my board and families decisions that are being made elsewhere and how they impact us.” Both Doug and Roger reported that there were many local stakeholders, including members of their board, who believed that schools should not close. This view was supported in some public commentary that I found in local newspaper editorial pages. In one comment a resident complained that “the Governor is taking away our rights to make our own decisions about how we live our lives and run our schools.” Indeed, the sense that local decision-making authority was being usurped was prevalent across the districts I studied. As Doug noted,

We have always had a very strong culture of local control in this county and don’t like the state poking around in our business. But the virus has given a lot more authority to the state and that’s not been easy for my folks to swallow. That’s spooked some people because they feel like their choices are being taken away.

Roger, Doug, and Frank each noted that their board members found the initial expectation that schools would close to be an unwelcome decision and a profound intrusion on their communities. Roger noted that many people in the community saw the virus as a “city problem.” This view was echoed by Doug, who stated, “Most of us were not of the mind that we really needed to close. Our hope was to maybe let the urban schools close and let places where the cases were more clustered deal with it differently.” This quote reflected both the community’s expectations about the role of schools as well as the belief that this was not a public health issue that directly concerned the rural communities. The superintendents reported that the nature of the public health crisis changed the calculus for many of their decisions early in the pandemic and in the lead up to reopening schools. Preferences of the local community seemed to give way to the requirements imposed by the state. As Doug stated, “There was a really strong will to close the schools down across the state. And the last few of us that remained open kind of capitulated to the will of everyone else.” Roger, Frank, and Dorothy similarly described the state’s decision to close schools as being the primary reason that they chose to do so and suggested that had the state not intervened they would have remained open.

Increasing Division and Disagreement Among Formerly Stable Actors

Given the changes occurring in their communities due to the pandemic, superintendents perceived that their communities had become increasingly divided about public health issues, operating protocols, and school reopening procedures. Indeed, their comments broadly suggested that stability among key actors in their district changed as the actions necessitated by the pandemic unfolded. Frank, in particular, spoke at length about his concern that the community had become “polarized” and “divided” during the pandemic due to the increasingly politicized views about the virus, disagreements about public health precautions, and the decision about whether to keep to schools closed protect students and staff from exposure. He noted that community leaders had come to increasingly disagree about how many precautions should be taken and at what expense. Frank noted that throughout the pandemic, he’d observed more “division” in his community than at any time during his superintendency.

I think as a community, there's been a lot of division that we’ve had to deal with as a school district. There has been some division about whether we should be in school or whether we should be out of school. And then beyond that, if we should be in school, should we be in virtual learning or should we be teaching in person. I think the other division is about what steps we should be taking. How should we be communicating with our parents? Should we be using our school messenger, the newspaper, social media to communicate with parents? What information should be communicated as far as our quarantine numbers or individuals that have tested positive. I think the last part of the division has been about what we should be doing or allowing in our schools. What measures should we be taking? Should we go to the extremes and take the temperature of every study upon entry? Should we be requiring more washing of hands? Should we be using electrostatic cleaners, the UV lights, everything, you know, should all those measures should be taken? And, honestly, as a community we have a lot of people who think those measures just aren’t necessary and that it’s a waste of taxpayer’s funds. So how we do manage that division in our community and try to bring them together in the school?

Frank’s comments illustrate the depth of the division in the community as well as the rising tensions around the issues related to the public health crisis that now confronted him as a superintendent. As he noted, “I used to have a dependably six vote block on the board for major decisions but that’s become more of a four to three block with the pandemic.” This suggested the extent to which he could not count on his board to make decisions as they previously had because of how profoundly their own views about the virus were shaping their votes on critical issues. Surprisingly, Frank found that much of the division was unrelated to the delivery of education and stemmed from disagreements about the steps that had to be taken to prevent the spread of the virus, implement guidance provided to schools by the United States Center for Diseases Control, or respond to directives issues by state’s own department of health.

Interestingly, Frank and other superintendents noted that the division between their board members related to the precautions that the community believed should be taken to reopen schools. He and other superintendents surmised that this had much to do with concerns about schools changing in light of the pandemic. He noted that some of the members of his community and representatives on his board baulked at expensive mitigation strategies (e.g., electrostatic cleaners, UV lights, etc.) that were being considered to stem the virus. Board members perceived that this would constitute a “waste of taxpayer’s funds.” Frank also noted that the community and board members were divided about how to communicate with parents and families. As Frank noted, “In a small community like ours, a lot of the communication comes through the school in weekly packets and so when the school is not open, how do we get that information out?” Frank noted that about one quarter of the families in the district lacked broadband internet access and instead relied primarily on cellular hotspots to access the school’s learning management system and to receive communication about the district’s plans for reopening. Beyond what Frank noted above, other superintendents found disagreements in their communities related to a variety of protective measures. For example, Dorothy noted that her board was divided about requiring masks and facial coverings in schools. Susan found that accommodations in teacher working conditions and use of unemployment benefits were especially divisive. Doug found that tensions with local education association leadership about appropriate compensation for online learning was a major issue. Roger noted that disagreements between his board members and the state’s high school athletics association were especially pronounced.

Four of the superintendents reported that the board members’ own political perspective tended to shape their willingness to close schools or adopt health and safety precautions. As Roger noted, “I’ve got two Trumpers on there who think this is all going to go away after the election. So, you present a plan to them that comes from the county and suddenly you’re the one who is taking away their basic freedoms and stuff.” Indeed, he noted that community members and others with ties to these members actively questioned key decisions about the initial school closure. Probing further I found that individuals who supported the board members’ elections, had ties to the county’s largest businesses, or owned farms where employees depended on public schools for childcare were among those exerting the greatest influence. As editorials in the local paper suggested, the sentiment in the community was that the pandemic was “hoax” and that it was “political” in nature. Editorials thus urged public leaders, including the superintendent, to avoid taking health precautions in order to avoid becoming politically involved. As Roger noted, “I think these, you know, voices really weighed heavily on my members and they made a few of them a little bit more aggressive in their resistance because they believed that this wasn’t real and would go away.” Superintendents offered various examples to demonstrate how this resistance played out with responses ranging from voting no on motions in meetings to questioning expenditures for personal protective equipment and other safety supplies. Frank noted that his board repeatedly questioned the value of purchasing sterilizing foggers, which are handheld blowers that can sterilize a bay of lockers or sanitize the inside of an entire bus.

Using Public Health to Reconcile and Overcome Divergent Perspectives

Despite the division arising in their communities and among board members, the superintendents still found that the threat of the pandemic required them to take action. A critical focus in their leadership was to identify how to reconcile diverse perspectives among key constituencies and members of their board. At times, this required making decisions without the familiar degree of consensus among their board members, risking public votes, or taking actions that were opposed by key district stakeholders, such as major employers or high school athletics boosters. The superintendents justified their decisions as being a response to the pandemic and used public health concerns as the basis for their actions. For example, Dorothy and Roger recognized that the health risks posed by the pandemic did not allow them to continue operating as they had previously. As Dorothy noted, “When we first said we were closing the schools, the board was not happy because they believed what they had heard in the media and didn’t want to see the threat that the virus actually posed.” She noted that her board members actually encouraged staff to remain in their district’s schools and instead of fully closing. Roger noted that the most conservative elements of his community had significant influence on the board. Recalling a conversation with his school board members, he recounted one exchange where a powerful board member who was backed by the owner of his county’s largest employer stated that the schools close should only close for weather related issues and that this “cold” seemed to be overblown. Roger noted that two additional board members shared this perspective initially. However, these three board members ultimately capitulated when it became clear that the schools were no longer safe for teachers and students at the height of the pandemic’s onset.

The superintendents also viewed the inconsistencies in public health guidance as a major reason for the division in their communities as well as the uneven adoption of public health measures. As Roger observed, “I think it had to become clear that this would impact children, then the board members with kids in our schools started coming around even if they were still skeptical about it personally or because of what they had believed.” Editorials in the local newspapers seemed to corroborate the perspectives in these communities. Editorials advocated closing based on the risks to children and staying open based on the needs of local businesses. In one editorial published in the local paper, a resident wrote in late February, “We must do what is right for the children and teachers who work in [school district name].” When pressed why his board members were reluctant, Roger explained that many of his most conservative members did not understand that the virus was a real health threat. As he recalled,

There’s nothing consistent about this response. Just 15 miles down the road, you are in a different county, in different school district, and under a different health department, and you see very different rules. You see them holding church and hosting an auction. So, it’s natural that they look down there and wonder why we need to take a different action.

Frank echoed this perspective, noting that the “patchwork quilt of health departments” and the different guidance they issued made it difficult for the superintendents to argue for closure in some places where residents were familiar with different health directives. Doug explained that his board was not initially willing to embrace the concept of closing schools nor in agreement about the severity of the threat posed by COVID-19 and partly attributed this reluctance to the mixed messages his county’s health authorities offered during daily briefing calls. Documents I obtained from four of the county health departments and copies of local health orders supported this perspective. The documents issued different guidance based on the size of gatherings allowed, whether and how many precautions needed to be taken, and what to do in the event of a positive case.

Varied Responses to COVID-19 and Opportunity for Leadership Action

While local politics might have precluded action under typical circumstances, I found that the superintendents found ways to capitalize on their district’s experience with the virus to take specific actions designed to mitigate the threat of the virus as well as to protect administrators, teachers, and students. Their responses ranged from those which were purely reactive to those which could be considered more pragmatic or forward thinking. For Doug, Roger, and Frank, who led communities that were the most resistant to taking action in response to the virus, I found that direct experience often generated support among their board members that allowed them to take actions necessary to mitigate the looming public health threat. These superintendents described constituencies in their district as being fundamentally committed to keeping their schools open regardless of the stakes. They believed that their rural location led would allow them to withstand the health risks associated with the pandemic. However, the rapid spread of the pandemic removed these benefits. As Roger noted, “Until we had our first exposure to the virus, we really thought this was not going to be a big deal. But that changed once we felt it.” Roger described his community as being “hit hard” by the pandemic due to the fact that their community experienced a large outbreak in a local nursing home. This experience awakened the community to the threat of the pandemic as well as the importance of action to protect students and teachers. As he recalled,

We were hit early, one of the nursing homes got hit real early in the process and so right away we had seven or eight deaths in the community. The five school districts in our county had to react and we actually reacted before the health department did. We made the decision as a superintendent group that we were going to go ahead and shut down. And then, of course, the governor took over.

Frank seemed to echo this view noting, “Our folks weren’t really worried at first because they felt it was a city problem and wouldn’t touch us. Once it started to spread here, though, folks became a lot more concerned and their resistance to doing things started to loosen up a little bit.” He recalled a small outbreak in a local business as being the primary trigger for action. In another district, I found that teachers who had contracted the virus precipitated action on the part of the school board. As Dorothy noted, “We had one teacher who is beloved in the community get it and that created a ground swell of support.” She recounted teachers and school staff organizing meals for the teacher, working to cover classes, and try to ensure that students were served in the teacher’s absence. Once these efforts were underway, she noted that the board members and larger community began to coalesce around some of the public health recommendations that they previously had not supported such as wearing masks in schools, social distancing, and other guidelines.

To further mediate the political extremes on their boards and in their communities, I found that superintendents skillfully used their emerging collaboration with the public health department to buffer critiques from their board members. As Roger, whose board members supported President Trump explained, “In this instance, I was able to say: Hey, the county health commissioner said this, and this is the way it’s going to be. That pretty much shut them up.” Indeed, because the pandemic intersected with public health guidance, this intersection often provided superintendents with leverage to manage their boards reactions as well as to project leadership that resistance might not have permitted otherwise. Susan, Dorothy, and Doug spoke to the value of routine convenings with their health department officials who helped them interpret the rapidly changing guidance from the state department of health as well as working with officials to expedite testing resources and positive COVID test results to help the superintendents carry out contact tracing, identify students who needed to quarantine, and ultimately deploy staff to cover absences. In drawing on this information and working with public health officials, superintendents acquired new skills and knowledge that they then were able to communicate back to their board members and districts in order to prompt particular policy decisions or justify controversial actions that the politics of their communities might not otherwise have supported.

Four of the five superintendents primarily reacted to the circumstances created by the pandemic and sought to manage their school boards by providing them with information. Roger, Frank, Doug, and Dorothy invested considerable energy managing their board member’s political philosophy in order to convince them to support closing schools, pivot to distance learning, as well as to maintain some aspects of distance learning throughout the Spring semester after health conditions began to improve. They repeatedly stressed the importance of keeping board members informed about conditions in the district and pointed to the value of sharing information with the board members. Most of the superintendents perceived that their board members became more supportive as they shared information and collaborated with them to identify acceptable safety measures to reopen schools. As Dorothy noted, “My board has been supportive of most of the actions I’ve taken, and they’ve been very willing to collaborate with me when trying to make plans for the coming year.” She noted that board members attended public forums to discuss the pandemic with the community, participated in a briefing provided by the state department of health, and jointly developed communications for parents and families that were disseminated through the school’s online systems as well as in the local newspaper. Frank, Doug, and Roger echoed this perspective noting that their board members became more supportive as evidence suggested that this was a serious public health threat and that the superintendent was asking their support in order to manage it. As Roger noted, “I think I’ve tried to keep them in the loop and try to help them be as well-informed as possible but it’s not easy because they still want to believe what they believe.” I noted that all of the boards passed resolutions authorizing the superintendents to respond to the pandemic through the management of the school’s instructional program, allocation of resources, adjustments to district transportation processes, and procurement of health and safety supplies.

Surprisingly, only one of the superintendents modeled the kind of crisis leadership that one might hope to see in such a severe situation. Susan saw the pandemic as a threat without significant community support and chose to take decisive action to address the situation even before enlisting her board’s support. She described herself as “always forecasting or predicting kind of what I see coming on the horizon.” Unlike her colleagues, she was motivated by the accumulating public health information as well as recognition that a prolonged public health crisis would necessitate providing instructional remotely for an extended period of time. As she noted at the outset of the pandemic, “We’ve got a problem here and we’re gonna have to start getting ready for it.” This prompted her to direct staff within her district to begin preparations. Before any formal direction from education officials, Susan instructed staff to prepare for e-learning. “So, we actually prepared like ten days or remote lesson plans before we needed them and we had everybody in the whole district prepared right up to Spring Break.” Susan estimated that this would provide her with sufficient instructional time to reach early April, a point at which she hoped the virus would subside and schools would reopen. Indeed, in the cases where the superintendent acted early, there was hope that the conditions would be temporary and that normal operations would resume. Her leadership reflects what the crisis leadership literature describes as the leader’s willingness to project, adjust, and anticipate that the circumstances surrounding the crisis could worsen rapidly.

Interestingly, Susan perceived that this kind of proactive leadership was supported by her board. She noted that her board members were “really looking for some leadership on this.” She indicated that the majority of the board members were supportive of her efforts to prepare the district and that their perspective on the pandemic had been influenced by a member who was also a healthcare provider. As she stated, “our vice president is also the director of nursing for [a local healthcare provider]. She’s very connected to the medical field …. So, she’s seen both sides of this as a practitioner and a board member.” This dual perspective enabled her to promote a balanced perspective among board members as the superintendent perceived that the board members deferred to her to make sense of the changing public health guidance. I found that a coalition of moderate board members was especially important was it allowed Susan to respond more proactively to the pandemic than her colleagues with more conservative members. Susan’s responses included purchasing supplies necessary for safe district operations as well as increasing the availability technology for remote learning. She also worked closely with the health department and major employers to prepare for the possibility of an extended school closure. This ability to respond created opportunities that proved beneficial to the superintendents, notably by increasing trust between the superintendent and board as well as promoting a sense of general welfare for students, teachers, and the broader community.

Discussion and Future Research

The findings from this exploratory study illuminate the extent to which the COVID-19 pandemic has upended leadership practices in these rural settings and shifted the decision-making processes undertaken by five rural school superintendents. Evidence suggests that the rural superintendents have not widely engaged in crisis leadership behaviors that have been described elsewhere in the scholarly literature (Decker, 1997; Brock et al., 2001). Rather, they have engaged in leadership that seeks to manage and mitigate political resistance from their elected board members. This orientation has meant that superintendents were acutely aware of the disruptions to their local communities, districts, and in the public health system. As such, they sought to calibrate their leadership actions carefully. This approach reflects well the conceptualization of a superintendent as a “statesman” or “strategist” (Bjork and Gurley, 2005). One remarkable finding is the extent to which superintendents leveraged public health to prompt particular policy decisions or justify actions that were politically controversial in their communities. Although prior research has not fully considered how superintendents might function as public health officials, the findings from this study suggest that they engender the qualities of a public health leader when responding to a health crisis as severe as COVID-19. Moreover, the findings suggest that leadership preparation programs might more fully attend to the potentially vital public health role of superintendents. Indeed, this role appears to be one that merits further consideration.

Another striking aspect of this study is the extent to which the superintendent’s leadership was not about leading online learning or promoting instructional quality. This suggests something important about their work that may have been occurring even before the pandemic. While the hope has long been that superintendents act as instructional leaders (Petersen and Barnett, 2005; Mountford and Wallace, 2019), a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic potentially mitigates the expectations about this focus for leadership. Indeed, much as Muffet-Willett and Kruse (2008) have observed, crisis leadership often requires leaders to employ knowledge and skills that are distinctly different from those utilized in routine work. In the case of the pandemic, superintendents sought to communicate across politicized extremes to ensure that the sense of division and uncertainty in their community was mitigated. This approach reinforces the perception that crisis leadership is a fundamentally communicative act (DuBrin, 2013; Liu, et al., 2020). Thus, understanding how, why, and when superintendents engage in crisis leadership is a potentially novel area for further exploration that could inform both practice and preparation. Indeed, a major implication from this study is that superintendents were not adequately prepared to manage the crisis and thus further attention should be paid to their preparation, professional development, and training. Additionally, their school districts were poorly equipped to handle the multiple crizes posed by the pandemic and thus planning for future public health emergencies should be a focus for superintendents.

Finally, the study sheds further light on the unique circumstances of rural communities–both as a site of the pandemic and a unique context for educational leadership. As research has dictated previously, the primary difference between the challenges faced by educational leaders in urban, suburban, and rural communities relates to the scale and intensity of these challenges (Lamkin, 2006). As Lamkin (2006) previously observed, rural leaders are thought to experience challenges that are potentially faster, deeper, longer, and more public. Amid the pressure of the COVID-19 pandemic, it also bears noting that the challenges associated with a public health emergency may be more disruptive both to the role of the rural superintendent as well as the political norms and local expectations about rural schools. This line of inquiry is both promising and needed given sociopolitical disagreements that have perplexed education specifically and our public institutions generally.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data set is considered confidential and will not be shared publicly. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Chad Lochmiller, Y2xvY2htaWxAaW5kaWFuLmVkdQ==.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Indiana University Bloomington. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

CL conceptualized the study, collected and analyzed the data, and produced the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Acker-Hocevar, M., and Ivory, G. (2006). Update on voices 3: focus groups underway and plans and thoughts about the future. UCEA Rev. 48 (1), 22–24.

Acker-Hocevar, M., Northern, T., and Ivory, G. (2009). The UCEA project on education leadership: voices from the field, phase 3. Educ. Considerations 36 (2), 1–7. doi:10.4148/0146-9282.1163

DuBrin, A. J. (2013). Handbook of research on crisis leadership in organizations. (North Hampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing).

Alsbury, T. L., and Whitaker, K. S. (2007). Superintendent perspectives and practice of accountability, democratic voice and social justice. J. Educ. Admin 45 (2), 154–174. doi:10.1108/09578230710732943

Arnold, M. L., Newman, J. H., Gaddy, B. B., and Dean, C. B. (2005). A look at the condition of rural education research: setting a direction for future research. J. Res. Rural Educ. 20 (6), 1–25.

Association of School Business Officials (2020). What will it cost to reopen schools? Retrieved from: https://www.asbointl.org/asbo/media/documents/Resources/covid/COVID-19-Costs-to-Reopen-Schools.pdf. (Accessed December 17, 2020)

Bjork, L. G., and Gurley, D. K. (2005). “Superintendent as educational statesman and political strategist,” in The contemporary superintendent: preparation, practice, and development. Editors L. G. Bjork, and T. W. Kowalski (Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press), 163–186.

Blissett, R. S. L., and Alsbury, T. L. (2018). Disentangling the personal agenda: identity and school board members' perceptions of problems and solutions. Leadersh. Pol. Schools 17 (4), 454–486. doi:10.1080/15700763.2017.1326142

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3 (2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brock, S. E., Sandoval, J., and Lewis, S. (2001). Preparing for crises in the schools: a manual for school crisis response teams. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Budge, K. (2006). Rural leaders, rural places: problem, privilege, and possibility. J. Res. Rural Educ. 21 (13), 1–10.

Chance, E. W. (1999). The rural superintendent: succeeding or failing as a superintendent in rural schoolsLeadership for rural schools: lessons for all. Lancaster, PA: Technomic Publishing Co.

Crayne, M. P., and Medeiros, K. E. (2020). Making sense of crisis: charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic leadership in response to COVID-19. Washington, DC: American Psychologist. doi:10.1037/amp0000715

Decker, R. H. (1997). When a crisis hits: will your school be ready?. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Egan, L. (2020). Trump calls coronavirus Democrats’ “new hoax”. New York, NY: NBC NewsRetrieved from: https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/donald-trump/trump-calls-coronavirus-democrats-new-hoax-n1145721. (Accessed December 17, 2020)

Fehr, R., Kates, J., Cox, C., and Michaud, J. (2020). COVID-19 in rural America- Is there cause for concern?. Retrieved from: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/covid-19-in-rural-america-is-there-cause-for-concern/. (Accessed December 17, 2020)

Feuerstein, A. (2002). Elections, voting, and democracy in local school district governance. Educ. Pol. 16 (1), 15–36. doi:10.1177/0895904802016001002

Geverdt, D. E. (2015). Education demographic and geographic estimates programs (EDGE): locale boundaries users’ manual. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics Retrieved from: http://nces.ed.gov. (Accessed December 17, 2020)

Hackman, M. Z., and Johnson, C. E. (2013). Leadership: a communication perspective. 2nd edn. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

Harris, A. (2020). COVID-19 - school leadership in crisis?. J. Prof. Capital Community 5 (3–4), 321–326. doi:10.1108/jpcc-06-2020-0045

Hayes, S., Flowers, J., and Williams, S. M. (2021). “Constant Communication”: rural principals’ leadership practices during a global pandemic. Front. Educ., 6, 617058. doi:10.3389/feduc.2020.618067

Helsloot, I., and Groenendaal, J. (2017). It’s meaning making, stupid! Success of public leadership during flash crises. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 25 (4), 350–353. doi:10.1111/1468-5973.12166

Hyle, A. E., Ivory, G., and McLellan, R. L. (2010). Hidden expert knowledge: the knowledge that counts for the small school-district superintendent. J. Research on Leadership Edu., 5 (4), 154–178. doi:10.1177/194277511000500401

Howley, A., Howley, C. B., Rhodes, M. E., and Yahn, J. J. (2014). Three contemporary dilemmas for rural superintendents. Peabody J. Educ. 89 (5), 619–638. doi:10.1080/0161956x.2014.956556

Kamentz, A. (2020). Survey shows big remote learning gaps for low-income and special needs children Retrieved from: https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/05/27/862705225/survey-shows-big-remote-learning-gaps-for-low-income-and-special-needs-children?utm_source=facebook.com&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=npr&utm_term=nprnews. (Accessed December 17, 2020)

Kealey, T. (2020). April 7). South Korea listened to the experts Retrieved from: https://www.cnn.com/world/live-news/coronavirus-pandemic-04-08-20/h_3b869bd5edb73903081c2b6b24f94fea. (Accessed December 17, 2020)

Kibble, D. G. (1999). A survey of LEA guidance and support for the management of crises in schools. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 19 (3), 373–384. doi:10.1080/13632439969113

K. Leithwood (1995). Effective school district leadership: transforming politics into education (Albany, NY: SUNY Press).

Kowalski, T. J. (2005). “Evolution of the school district superintendent position,” in The contemporary superintendent: preparation, practice and development. Editors L. G. Bjork, and T. J. Kowalski (Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press), 1–19.

Lamkin, M. L. (2006). Challenges and changes faced by rural superintendents. Rural Educator 28 (1), 17–24.

Leithwood, K., and Montgomery, D. J. (1986). The principal profile. Toronto, ON: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

Lichtenstein, R., Schonfeld, D., and Klein, M. (1994). School crisis response: expecting the unexpected. Educ. Leadersh. 52 (3), 79–83.

Lifto, D. E. (2020). Leadership matters: superintendents’ response to COVID-19. School CEO Retrieved from: https://www.schoolceo.com/a/leadership-matters-superintendents-response-to-covid-19. (Accessed December 17, 2020)

Lowenhaupt, R., and Hopkins, M. (2020). Considerations for school leaders serving US immigrant communities in the global pandemic. J. Professional Capital and Commun., 5 (3/4), 375–380. doi:10.1108/JPCC-05-2020-0023

Liu, B. F., Iles, I. A., and Herovic, E. (2020). Leadership under fire: how governments manage crisis communication. Commun. Stud. 71 (1), 128–147. doi:10.1080/10510974.2019.1683593

Manasse, A. L. (1985). Vision and leadership: paying attention to inattention. Peabody J. Educ. 63 (1), 150–173.

McHenry-Sorber, E., and Budge, K. (2018). Revising the rural superintendency: rethinking guiding theories for contemporary practice. J. Res. Rural Educ. 33 (3), 1–15.

Mountford, M., and Wallace, L. E. (2019). “(R)Evolutionary leadership: an innovative response to rapid and complex change,” in The contemporary superintendent: (R)evolutionary leadership in an era of reform. Editors M. Mountford, and L. E. Wallace (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing), 1–12.

Muffet-Willett, S., and Kruse, S. (2009). Crisis leadership: past research and future directions. J. Business Continuity Emerg. Plann. 3 (3), 248–258.

Mutch, C. (2015). Leadership in times of crisis: dispositional, relational and contextual factors influencing school principals' actions. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduction 14 (2), 186–194. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2015.06.005

O’Malley, M., Wendt, S. J., and Pate, C. (2018). A view from the top: superintendents’ perceptions of mental health supports in rural school districts. Educ. Adm. Q. 54 (5), 781–821.

Petersen, G. J., and Barnett, B. G. (2005). “The superintendent as instructional leader,” in The contemporary superintendent: preparation, practice, and development. Editors L. G. Bjork, and T. W. Kowalski (Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press), 107–136.

Phillips, T. (2020). Jair Bolsonaro claims Brazilians “never catch anything” as COVID-19 cases rise. London,United Kingdom: The Guardian Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/mar/27/jair-bolsonaro-claims-brazilians-never-catch-anything-as-covid-19-cases-rise. (Accessed December 17, 2020)

Preston, J. P., Jakubiec, B. A., and Kooymans, R. (2013). Common challenges faced by rural principals: a review of the literature. The Rural Educator 35 (1).

Smith, L., and Riley, D. (2012). School leadership in times of crisis. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 32 (1), 57–71. doi:10.1080/13632434.2011.614941

Snyder, T. D., De Brey, C., and Dillow, S. A. (2019). Digest of education Statistics 2017, NCES 2018-070. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Starr, J. P. (2020). On leadership: responding to COVID-19: short- and long-term challenges. Phi Delta Kappan 101 (8), 60–61. doi:10.1177/0031721720923796

Stephens, E. R., and Turner, W. G. (1988). Leadership for rural schools. Arlington, VA: American Association of School Administrators.

Stone-Johnson, C., and Weiner, J. M. (2020). Principal professionalism in the time of COVID-19. Jpcc 5 (3/4), 367–374. doi:10.1108/jpcc-05-2020-0020

Tekniepe, R. J. (2015). Identifying the factors that contribute to involuntary departures of school superintendents in rural America. J. Research in Rural Edu., 30 (1), 1.

Taylor, R. T., and Touchton, D. (2005). Voices from the field: what principals say about their work. J. Scholarship Pract. 4, 13–15.

Timar, T., and Tyack, D. (1999). The invisible hand of ideology: perspectives from the history of school governance. Denver, CO: Education Commission of the States.

Tompkins, R. B. (2019). Coping with sparsity: a review of rural school finance. in Education in rural America. London, United Kingdom: Routledge, 125–155.

Touchton, D., Taylor, R. T., and Acker-Hocevar, M. A. (2012). “Decision-making processes, giving voice, listening, and involvement,” in Snapshots of school leadership in the 21st century: the UCEA voices from the field project. Editors M. Acker-Hocevar, J. Ballenger, A. W. Place, and G. Ivory (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing), 121–146.

U.S. Department of Agriculture (2017). Rural education at a glance: 2017 edition (economic information bulletin, EIB-171). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service Retrieved from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=83077. (Accessed December 17, 2020)