- Faculty of Education, Edge Hill University, Ormskirk, United Kingdom

This paper employs a Square of Opposition as an interpretivist heuristic device in order to interrogate perceptions of academic support. The Square of Opposition is used to move beyond binary explanations of academic development subsumed within learner-/discipline-focussed practices or institutionally /epistemologically constrained systems; an exemplar data set is used to achieve this. The results of this analysis demonstrate that positions that might normally be understood as opposed in fact share common features, at least where some key concepts are concerned. In particular, two “contradictories” are explored: the first of these critiques the differences and similarities between contested meaning-making and knowledge dissemination and the second analyses the disjuncture between skills-focussed instruction and academic literacy as a social practice. This form of analysis offers new insights that directly speak to the ways in which we conceive of, and enact, teaching, personal tutoring and academic advising.

Introduction

At the time of writing this article, a global pandemic is changing the face of education. In response, universities are offering a range of teaching models, including what has been termed in the United Kingdom as “in-person” teaching and student support. Although these are truly unprecedented times that will impact upon student mobility, financial viability, and potential restructuring of the university experience, the Academy can learn much from the literature to date on academic support. For example, structures that focus on knowledge dissemination or skills-focused instruction, may lose sight of the complexity of meaning-making (Murray and Nallaya, 2016) and the social practices of academic support. In effect, current challenges provide fertile ground to review what Hathaway (2015) termed pedagogic priorities.

Indeed, the current situation presents opportunities to problematise how aspects of academic development are enacted beyond that which can be offered via, in a worst-case scenario, asynchronous online fora. New territory is inevitable but all that has been learned about the systems that create student success or failure remains relevant; possibly invaluable. In response, this study offers a unique way of analysing academic support to inform practice for an uncertain future.

Originating in logical analysis as a tool for analysing logical relationships between propositions, the Square of Opposition was developed as a method for narrative analysis by Griemas in the 1960s (Greimas and Rastier, 1968). Subsequently, it has been drawn upon in cultural studies to model conceptual relationships between components of models of social science (Jameson, 1988) and other forms of ideological and cultural analysis (Bull, 1996).

For this study, an exemplar data set has firstly been examined via Interpretivist Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) and then mapped onto a Square of Opposition. From this, the positions articulated by each group can be seen to relate to each other in ways that confound curricular and pedagogic binaries. The Square, then, appears to be a fertile tool for re-examining debates in the field; that is, it creates space to look at data from one context to elucidate global challenges in Higher Education.

Mapping the Terrain

As disciplines, services and institutions vary in nature and culture, this article is more concerned with epistemic structures in order to take account of the fact that universities are situated in, and often reflect, society at large. If we take the current situation in the United Kingdom, the mainstream media reported, in July 2020, that Chinese students (who bring around £4bn per year to the United Kingdom) are afraid to study in the United Kingdom due to fears over the high death toll from the Covid-19 pandemic. Messages of this nature have the potential to create fear around the safety of university campuses resulting in staff, and students, rethinking how teaching and learning might occur.

Six years ago, Hathaway (2015) cautioned that the forms of tuition offered by separate support systems should “no longer be seen as support, and therefore marginalised, but as a transformative process of acculturation that needs to be located in the mainstream of the university” (p.507). This would require all members of the Academy to review what they believe the mainstream of the university to be, and to what students are being accultured. Much media attention has been given to debates around an impoverished student experience and demands for a reduction in student fees have been muted. Whilst Cambridge University (as an example of the Russell Group) announced, in May, that there will be no face-to-face lectures until Summer 2021, post-92 universities have generally taken a different stance, maintaining that face-to-face provision will take place unless it is unsafe to do so.

With the current focus being on how lectures will take place and how content will be covered, a culture is growing that raises the risk of positioning “academic as subject expert, academic support staff as literacy expert and the student as either skilled or skill-deficient” (author, 2019, p.2). Thus, as noted by Percy in 2014 and returned to later in this article, there is a danger that historical, intellectual, and symbolic structures will continue to reproduce deficit modes of practice.

In contrast, some consideration of approaches such as reading resilience (Douglas et al., 2016) or “writing practices as a means of developing discourse competency within a field of study” (Harper and Vered, 2017, p. 690) might encourage all staff to rethink pedagogic priorities. Both examples (of which there are many) highlight the importance of exploring how teaching and learning practices can be designed to develop all forms of academic discourse. Such exploration enables interpretation of action.

Given the correlation between academic writing and academic achievement, it has long been noted that students often “struggle to understand the manner in which meaning is constructed in writing and the nature of power and authority as they pertain to the writing process” (Murray and Nallaya, 2016 p. 1,298). In this world of fractured academic experiences, it is easy to see how instrumentalism and attainment might take priority over giving “voice to both our ideas and ourselves” (Hutchings, 2014, p.316). In this regard, Harper and Vered, warn that:

“A focus on product can lead to writing that is voiceless, a collage of references to others in the required format and structure, but without any sense of what the student thinks about the topic or the citations referenced. Communication therefore needs to be conceptualised as both product and process: a purposeful (expressive) transaction” (2017, p. 697).

This observation invites consideration about what and how we teach, support, and assess, and for what purpose. Any confusion, even when benign in origin, leads to a lack of clarity and detail about the roles of tutors, academic advisors, and students. Addressing this will require Higher Education institutions to be willing to create space for all members of the academic community to be able to contest academic norms, and knowledge claims, in the new reality of university teaching and learning.

The Exemplar Data Set

In contrast (or perhaps as a complement) to studies that have sought to provoke universal discussion from local data (three useful examples, among many, being Murray and Nallaya, 2016, McGrath and Kaufhold, 2016, and Harper and Vered, 2017), the data on which this article in based does not relate to a specific initiative or program. Instead, the purpose was to consider data from a range of academic disciplines and programmes, collected across a post-92 university in the United Kingdom, to which the Square of Opposition can be applied. The aim, here, is to extend debates in the field via a real-world example. The university from which the data was collected offers a wide range of face-to-face, workshop-based and online academic support services facilitated by a centralised Learning Services department for approximately 12,000 undergraduate and 4,000 postgraduate students. The study involved semi-structured interviews with undergraduate students from a variety of disciplines across the university, tutors from the same disciplines, and centralised academic support staff working with undergraduate students. As the interviews were based on the lived realities of each participant, the intention was to model perceptions of academic support using a Square of Opposition affording the opportunity to analyse experience through a new lens.

Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) was used as the methodological framework for the initial analysis of this data in order to explore participant experience in a way that disavows the presumption of an emergent “reality”. As such, the purpose was to take an idiographic approach to the data.

Disciplines for student and tutor interviews were identified using Biglan. (1973) pure/applied hard/soft categorisation of disciplines. From this, the following disciplines were selected:

Pure soft: Psychology, History.

Applied soft: Education, Nursing.

Pure hard: Mathematics.

Applied Hard: Business Studies (the subject closest to Biglan’s Applied hard category, (i.e. Mechanical, Engineering, Civil Engineering and Economics).

Student Sample

Sixteen students were interviewed, eight male and eight female, representing the range of disciplines previously identified; the students were aged between 21 and 42 and three self-identified as having a Specific Learning Difficulty. Interviews continued until the data appeared “sufficient”, in that experiences were being similarly described. Participants (who were recruited via an open invitation sent out by an administrator), represented a wide range of achievement, from those who had attained distinctions for individual module assignments, through students who had failed one module or more to those who had yet to submit an assessed piece of work.

Tutor Sample

From 27 responses (similarly recruited), a sample of 16 academic staff was selected to mirror the same range of disciplines represented by the student sample, alongside variation in age and length of service. This sample comprised eight male tutors and eight female tutors.

Academic Support Staff Sample

Once again, an open invitation to engage with this research was sent to all academic support staff. From a staff team of 17, twelve individuals made contact to say that they were willing to be interviewed. This sample involved staff supporting all academic faculties and included eight females and four males.

The Interviews

A pilot study was conducted with each participant group in order to analyse the potential impact of the dual role of academic and researcher so often experienced in research of this nature. Following the pilot interviews (undertaken with three students, two tutors and two members of academic support staff), debrief discussions on the experience of each interview indicated that the students felt that being interviewed by a tutor increased their expectation that something might change as a result of the interview (as discussed in Limes-Taylor Henderson and Esposito, 2017). The tutor and academic support staff did not report any concerns about being interviewed by an academic colleague, commenting that they would give the same answers to a research assistant. As a result of this, the student interviews were conducted by an independent research assistant and the staff interviews by the author.

Whilst employed at the same university, the author did not work on the main campus and, as a result, did not have prior contact with any of the tutors or members of support staff interviewed. Nonetheless, potential power relations had to be taken into consideration to address the presumed “ethicism” (Brinkmann and Kvale, 2006) of research of this nature. For example, participant anonymity was enhanced by not making interview data available on public repositories and by using Biglan’s disciplinary categories for academic staff. In addition, with regard to the interviews conducted with academic support staff, responses that could have been made by any member of the student support team were selected; that is, those who were not employed in an identifiable role.

In each case, interviews were conducted individually at a time and place of the interviewees’ choosing (in all cases a space on campus was chosen) and each interview was recorded and transcribed by the interviewer. In order to ascertain the lived experiences of academic support for students, tutors, and academic support staff, only one question was posed:

Can you give me an actual, but typical, experience of academic support?

This then formed the basis of a discussion around real-world experiences and perceptions of academic development. For example, as each interviewee described an event or experience, they were asked for additional detail where necessary.

Following Savin-Baden and Major. (2012) and Smith and Osborn (2007), each interview was scrutinised through a process of identifying, coding and connecting themes, paying due regard to issues of subjectivity, ethics and emancipation (discussed extensively by Braidiotti, 2006), Thus, in line with Smith et al. (2009), considerable emphasis was attached to the writing process undertaken when constructing the IPA framework, in order for the researcher’s role to be both explanatory and interpretative and to incorporate discursive as well as analytic interpretations of participant responses. The six-step approach advocated by Smith et al. (2009) was used to create a series of super-ordinate and sub-ordinate themes:

(1) reading and re-reading

(2) initial noting

(3) developing emergent themes

(4) searching for connections across emergent themes

(5) moving to the next case

(6) looking for patterns across cases

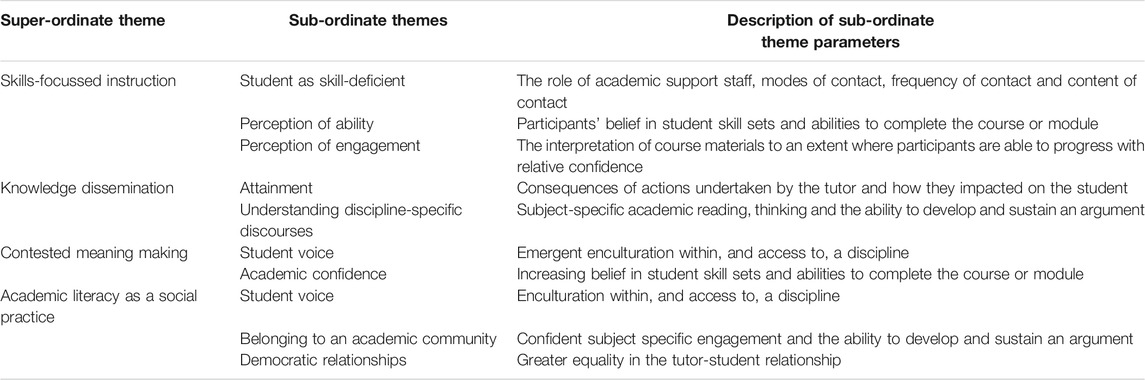

In the first instance, steps one to six were followed in order to create the four super-ordinate themes identified in Table 1. That is, emergent themes were identified, connections sought, and patterns identified. From this, each super-ordinate theme was further analysed in order to define sub-ordinate themes. To take the first example from Table 1, the super-ordinate theme “Skills-focussed Instruction” was further analysed to reveal a more nuanced picture of how participants articulated underlying perceptions of: skill deficiency; ability; and engagement. The third column of the table outlines the parameters of each sub-ordinate theme. So, for example, where student voice is identified as a sub-ordinate theme of “Contested-meaning making”, the parameters of this are noted as “emergent enculturation within, and access to, a discipline” In contrast, student voice in “Academic Literacy as a Social Practice”, is no longer described as “emergent”, rather it indicates authentic enculturation within, and access to, a discipline.

On analysis of these super- and sub- ordinate themes, a series of contradictions and tensions emerged which, when modeled on a Square of Opposition, have the potential to examine what (Roth and Tobin (2002), 116) describe as an “ethnography of trouble”.

Modeling Positions: The Square of Opposition

As mentioned earlier, the differences and similarities between perspectives can be analysed via a Square of Opposition or Semiotic Square.Beziau and Payette (2012) explored the different ways in which the original Aristotelian Square of Opposition has been developed for such varying purposes as narrative analysis, cultural studies and narrative logic. Following their example, the Square is used metaphorically and as a heuristic, rather than literally, in what follows.

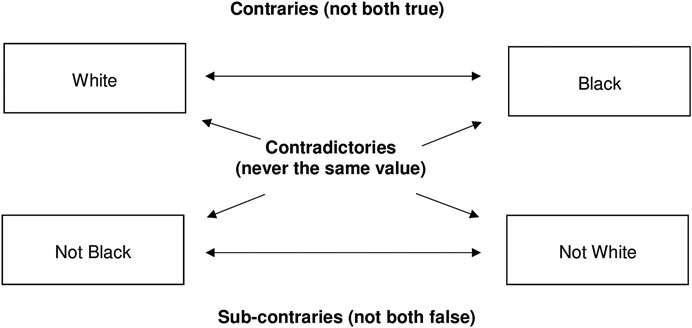

Perceptions of academic support are not simple categorical propositions and do not, therefore, have literal “truth value”, in the sense in which this term is understood in formal logic. However, by using the Square as a heuristic device, and as a tool for highlighting tensions, contrasts and commonalities, a deeper understanding of practice can be reached. A simple Square of Opposition is depicted in Figure 1.

The contraries mapped across a Square of Opposition are mutually exclusive (they cannot both be true) although not exhaustive (they can both be false, and another possibility may be true). Contradictories, on the other hand, are both mutually exclusive and exhaustive; they cannot both be true, but they cannot both be false. To illustrate this with an example drawn from Chandler, 2002: although the same object cannot be both “white” and “black” it can be neither (for example, “grey”). However, something must be “black” or “not-black” and cannot be both simultaneously and in the same respects.

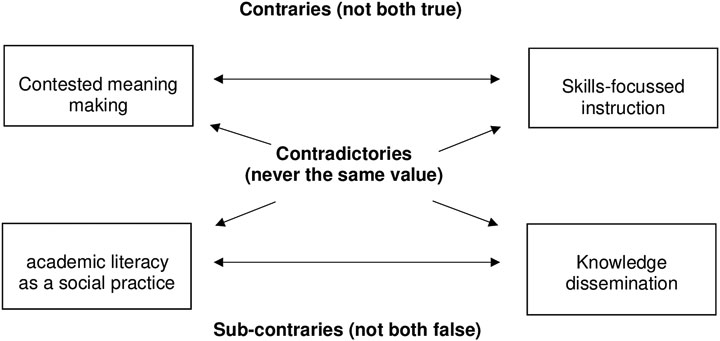

For the purpose of this study, a Square of Opposition was created by comparing key terms used by participant groups allowing commonalities and tensions to come to the fore. In doing so, it becomes possible to show how positions that might normally be understood as opposed in fact share common features. The analysis also allows the points of difference between key stakeholders to be brought out more clearly than they might otherwise be when arguments are presented in a linear manner.

Figure 2 in this example, the contraries and sub-contraries have been exhaustively debated in much of the aforementioned literature around academic support; more interesting for the purpose of this article are the “contradictories”.

Contradictory # 1: Contested Meaning Making vs Knowledge Dissemination

Here, contested meaning making refers specifically to pedagogic spaces that are designed to democratise, and make accessible, academic discourses in order to more clearly delineate our understanding of meaning- or knowledge-making. For example, tutors talked about “giving credibility to their (students) thinking so that they don’t just see us as the font of all knowledge” (Tutor six applied soft). Similarly, Student 12 (pure hard) explored the notion of contesting the views of her tutors explaining that “one of our tutors holds group tutorials where he just fires questions at us and it’s really hard at the time, but it really gets us thinking. It’s as though we have a right to challenge him”. Student 12 became animated when describing this experience and, in contrast to quotations linked to knowledge dissemination, appeared to relish the challenge of the unknown. Similar experiences were described when activities that encouraged students to challenge meaning making were facilitated by a tutor but enacted with peers:

We had a debate last week that went on for days and, one day, we were all still on there (the Virtual Learning Environment) past midnight. I know this probably isn’t the kind of thing you are looking for but this is the best kind of academic support as it provokes your thinking, encourages you to read and then you have to write a response so you develop the ability to formulate your thoughts in a written context. Student 15, applied hard).

In this quotation, Student 15 describes an intriguing interplay between thinking, articulation and response. Likewise, Student 10 (pure hard) described an experience that went beyond knowledge dissemination:

When you ask me to describe an actual example of academic support the thing that springs to mind is this big discussion we were having, last term, about the views across society about maths. It was fantastic, you talk about academic support–that’s academic support because it really got me thinking, with other mathematicians, about my subject.

This student talked about being a member of a specific discipline and framed academic support in terms of activities that enabled his enculturation within, and access to, that discipline. Similarly, when describing the particular features of individual texts, Tutor 11 (pure hard) described giving students two articles to read and then “asking the students to defend a position or to offer an opinion” emphasising that “our role is always to provoke … to develop their thinking”.

The distinction between contested meaning-making and knowledge dissemination (instruction as the transfer of knowledge) was often framed as subject-specific academic reading, academic thinking and the ability to articulate an argument. For example, Student 7 (applied soft) explained that:

I think some of the tasks that we are given in modules really bring us on especially some of the reading you get. For instance, I was really interested in Cognitive Behavior Therapy but couldn’t get the hang of academic reading so the tutor gave me an article to read about Cognitive Behavior Therapy and asked me to write an abstract for it. I found this really hard and a bit strange because we don’t have to write abstracts for our assignments, but, because the article was related to CBT, I got into it and then it was really interesting pulling it apart and really thinking about it, deeply.

In citing this as an actual, but typical, example of academic support, this student elected to share an experience in which interactions with her tutor enabled her to access academic texts, similar to that described by advocates of “close reading” (Douglas et al., 2016). In other examples, responses that related to knowledge dissemination focused upon attainment, as with Tutor 8 (applied soft) who argued that:

It’s good to get them to think about what we are looking for, for example to get a first in Education, they need to relate theory to educational practice; they’re not used to this. I think it makes the assessment criteria more accessible, some of them are worded in quite vague terms but when the students can look at real assignments and think about how they would answer them the criteria become more real.

In this sense, whilst recognising that students do need to develop particular academic skills, Tutor eight focused on subject-specific capability and student potential. A similar comment, from a tutor based in a very different subject area, was that:

We don’t expect them to come in operating at distinction level in all aspects, that’s actually very rare, it’s our job to help them to get there, or as near to it as they can, we can help them to interpret the criteria so that they can start to aim for a distinction (Tutor 9, pure hard).

Tutor 1 (applied soft) offered an example of this in relation to subject-specific knowledge and skills gained in undergraduate work in order to rise to the challenge of postgraduate work:

They are very good at writing history essays, they understand those conventions but when you come to using statistical data, they find it very, very difficult to look around and see patterns in order to be able to draw conclusions working from the evidence. Showing them how to do that, as a competent historian, is study support’

This quotation typified responses that placed subject-specific knowledge at the center of academic literacy development, thus justifying the need for knowledge dissemination.

Contradictory # 2: Skills-focussed instruction vs academic literacy as a social practice.

Comments about skills-focussed instruction ranged from those that valued skills-focussed academic support to those who found it demeaning. An example of the former was given by Student 7 (applied soft), who commented that: ‘I was really relieved when they said that we could go to sessions on Harvard or how to write at this level. I mean we got here by learning one set of skills but now we need another set’. Other students, however, appeared irritated by the fact that:

Some tutors tell us, over and over again, that students nowadays don’t have the same training that they used to do and that they didn’t used to have all these academic support sessions for things that we should already know (Student 4, pure soft).

In this instance, perceived levels of powerlessness associated with engagement with skills-focussed academic support sessions appeared to stem from an acceptance of tutor insistence that, in some way, students are ill-equipped for the academic demands of Higher Education. As Student 9 (pure hard) commented: “I went to a session about assignment planning. We keep being told that we need to go to these sessions as we don’t have the right skills and we all keep making the same mistakes”. As previously discussed, both examples echo concerns around the image of “the learning advisor as an agent of redemption performing compensatory educational practices” (Percy, 2014, p.1202).

Nevertheless, an interesting juxtaposition was posed by Tutor 7 (applied soft) who expressed concerns that this type of student response had the potential to created conditioned behaviors, in that:

We spend so much time telling them that they have to know how to reference and reading through the assessment criteria that the students just become totally instrumental and forget that this is supposed to be about learning, about enjoying forays in a discipline.

This concern was reflected in a response from a member of staff from academic support services who explained that:

We usually end up telling them to keep sentences short, to always use a topic sentence at the beginning of a paragraph, to follow the formula–tell them what you are going to say, say it, and then re-cap what you have said. It works every time and the students keep asking us for this session (ASS staff member # 1).

In addition, academic support staff consistently made the case that:

Virtually all students need induction in the use of the library, even though we have self-help guides, so we have a number of staff who do this. To be honest, they wouldn’t get very far without this, so I would say that it is an essential aspect of academic support (ASS staff member # 4).

Whilst it would be difficult to argue with the logic of this statement, per se, by describing an actual but typical example of academic support as induction in the use of the library, this member of staff presented an interpretation of academic support not given by tutors or students. Although unsurprising, entrenched positions can emerge whereby:

“…too often the way in which student learning and language is conceptualised resurrects the older models of thought and confines the agency of these practitioners within a redemptive model focused on the remediation on an individual student or social group outside mainstream teaching and learning” (Percy, 2014, p.1202).

Contrary to skills-focussed instruction, academic literacy as a social practice was highlighted by students and academic staff. When describing a wish to “be part of” an educational and social sciences research community, one student dismissed the potential contribution from staff, albeit dedicated to study support, who “are not members, themselves, of my discipline” (Student 4, pure soft). This perspective was echoed by students across the research sample with Student 13 (applied hard) arguing that: “In the business world, you need to be able to think in a certain way you can only do that by being in it; by thinking and debating as someone who is studying business”.

A tutor from the same discipline also argued that: “The only graduates worth producing are ones that understand the world they are entering, that can think, act and write as a business graduate” (Tutor 14, applied hard). These comments encapsulate the language used in relation to this category with the word “field” figuring more frequently than the more generic terms used in previous categories. One student explored this further by reflecting that:

I suppose the tutor is closer to your studies. I mean that they know the way we think, they’ve had discussions with us and listened to us talk; they know what we are trying to say and why. Now, someone from Study Support wouldn’t know that, would they (Student 5, applied soft).

In this quotation, Student five framed academic support within the tutor-student relationship, highlighting the specificity of what might be seen to be a community of academic practice. This quotation followed the description of a tutorial in which the student had experienced what she called “a light bulb moment” saying:

I suddenly understood why I had been going wrong, X (the tutor) told me that all I was doing was using the literature to support my thinking but I wasn’t being critical of the literature. She said I do this in discussion, too, and I hadn’t realised it.

It is interesting that, in the example given, anyone familiar with academic requirements may have been able to discern this difficulty and advise accordingly. However, Student five appeared to respond to the comparison drawn between her behavior during seminars and her writing.

Equally interesting was the point made by one tutor that:

As we’re not allowed to read a whole draft (of an essay), it can be quite difficult, I sometimes, at the end of a tutorial, advise the student to take their work to learning services but I don’t think that they do (Tutor 7, applied hard).

If this comment is taken within the context of broader concerns about the dangers of “centralized, decontextualized literacy support services … promoted as remedial … and often stigmatised” (Fox and O’Maley 2018, p.1599), confusion and contradictions between what we mean by academic literacy development will continue. As noted by one student:

It’s strange, really, I’ve been made to feel that I need study support because I want to be experimental and take risks with my learning. I guess I don’t need study support if I just play the game that I played at Sixth Form College (student 1, applied soft).

In effect, this comment indicates behavior counter to the purposes of Higher Education; a student who wants to think creatively deciding to revert to instrumental learning behaviors that had been successful previously can only be seen as a result of undemocratic, unjust and arguably anti-intellectual, forms of pedagogic communication.

Reflections

Two contradictories have been examined in this paper, and although each has been critiqued in terms of the degree to which commonalities and tensions come to the fore, each also shine a light on practices that deserve deeper analysis. That is, the methodological purpose of this study enables new ways of thinking about practice.

Specifically, it could be argued that there is a tendency to think in binaries when reflecting on teaching and learning in Higher Education and, at times, the literature might serve to confirm the binaries that currently dominate discussions around spaces for, and differing conceptualisation of, teaching, personal tutoring and academic advising.

The use of a Square of Opposition highlights the need to think beyond such binaries, many of which are bound up in learner-focussed/discipline-focussed modes of academic development or institutionally constrained/epistemologically constrained barriers to academic development. Yet, as the contradictories explored here highlight, reality is more nuanced than that illustrating that greater recognition of pedagogic complexity has the potential to become a starting point for the analysis of all forms of teaching and learning in Higher Education. As a result, the analysis enabled by the deployment of a Square of Opposition may be a little unsettling for some but invaluable for the Academy.

One valuable feature of the Square is that, although it starts with a binary, it goes on to multiply contrasts by drawing attention to, as it were, the shadows of the terms in the initial contraries. In addition, and central to this article, the Square makes visible contradictory positions that might otherwise be obscured.

Bass (2012) offers an interesting critique of teaching and learning in Higher Education arguing, amongst other things, that:

“Learning to “speak from a position of authority” is an idea rooted in expert practice. It is no more a “soft skill” than are the other dimensions of learning that we are coming to value explicitly and systematically as outcomes of Higher Education—dimensions such as making discerning judgments based on practical reasoning, acting reflectively, taking risks, engaging in civil if difficult discourse, and proceeding with confidence in the face of uncertainty” (p. 28).

If we relate this to academic development, dimensions of learning can be explored from new perspectives. In contradictory # 1, contested meaning-making was perceived as contradictory to knowledge dissemination. As with the critique offered by Bass, the aim of this paper is to recognise the importance of knowledge dissemination whilst questioning the degree to which teaching experiences enable practical reasoning and reflexivity.

Similarly, as explored in the second contradictory, viewing academic literacy as a social practice over skills-focussed instruction, does not disavow the latter. Yet, absence of the former can lead not only to “a lack of enthusiasm combined with a degree of scepticism–even cynicism” (Murray and Nallaya, 2016, p. 1,306) around the roles of other members of the academic community, but also to the creation of similar levels of cynicism across the student body.

As such, the contradictories identified here invite further examination of current debates around socio-cultural influences across the Academy in order to make visible the “important nuances that impact on how knowledge is created by students, and how it is taught and assessed by lecturers” (Clarence and McKenna, 2017, p. 39). Interestingly, four members of academic support staff expressed frustration at being forced to adopt instrumental approaches, with one member of this group describing herself as “sitting with my finger in a dam when I really want to be reviewing the whole system” (ASS member # 8). This quotation echoes concerns raised by (Harper and Vered, 2017, p. 689) that staff working in this field have “long critiqued such models as remedial”. Yet without adaptive leadership that seeks to embed new ways of support (Goldingay et al., 2016; Benzie, Pryce and Smith, 2017) the dominance of hierarchical structures is unlikely to disappear.

Although this article is about the Academy as a whole, implications of this analysis can be viewed at the level of each participant group, bearing in mind that these experiences are inextricably entwined. Firstly, the implications of this paper for students relate to the ways in which they engage with practices and practitioners across a university. Although power relations clearly exist, some of the students involved in this research were able to create communities of academic practice in order to influence the teaching and learning climate in which they studied.

Similar practices can be developed across a community of academic support staff who often work in a shared space and regularly feel dislocated from the wider work of the university. Academic support is a significant aspect of practice in Higher Education and the staff employed in academic support roles should see themselves as central to wider work of the university.

Finally, given that most tutors have significant autonomy over the ways in which they choose to teach, it could be argued that they have the greatest responsibility to enact socially just ways of teaching and learning. This is not to argue that the majority of tutors do not attempt to do just that, the point here is that such concerns need to be at the forefront of pedagogic design.

In summary, the purpose of this paper, as stated at the outset, was to view a recognised aspect of Higher Education through a different lens; a lens that enables us to view troubling aspects of Higher Education practice from a different perspective. Further examination and new ways of thinking are necessary if we are to continue to extend our thinking.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study will not be made publicly available Participants were assured that interview articles would be destroyed after analysis.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Edge Hill University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Bass, R. (2012). Disrupting ourselves: the problem of learning in higher education. EDUCAUSE review, 47 (2). Available at: www.educause.edu/er.

Benzie, H. J., Pryce, A., and Smith, K. (2017). The wicked problem of embedding academic literacies: exploring rhizomatic ways of working through an adaptive leadership approach. High Educ. Res. Dev. 36 (2), 227–240. doi:10.1080/07294360.2016.1199539

Beziau, J-Y., and Payette, G. (2012). The square of opposition: a general framework for cognition. Frankfurt, Oxford, New York, United States: Peter Lang.

Biglan, A. (1973). The characteristics of subject matter in different academic areas. J. Appl. Psychol. 57, 195–203. doi:10.1037/h0034701

Braidotti, R. (2006). “The ethics of becoming imperceptible,” in Deleuze and philosophy. Edinburugh, Scotland: Edinburugh University Press. Editor C. Boundas, 133–159.

Brinkman, S., and Kvale, S. (2006). Confronting the ethics of qualitative research. J. Constr. Psychol. 18 (2), 157–181. doi:10.1080/10720530590914789

Chandler, D. (2002). Semiotics: the basics. London, United Kingdom and New York, NY, United States: Routledge.

Clarence, S., and McKenna, S. (2017). Developing academic literacies through understanding the nature of disciplinary knowledge. Lond. Rev. Educ. 15 (1), 38–49. doi:10.18546/LRE.15.1.04

Copi, I. M., and Cohen, C. (1998). Introduction to logic. 10th Edn. New Jersey, NJ, United States: Prentice-Hall.

Culler, J. (1975). Structuralist poetics: structuralism, linguistics and the study of literature. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Douglas, K., Barnett, T., Poletti, A., Seaboyer, J., and Kennedy, R. (2016). Building reading resilience: re-thinking reading for the literary studies classroom. High Educ. Res. Dev. 35 (2), 254–266. doi:10.1080/07294360.2015.1087475

Eagleton, T. (1986). Against the grain: selected essays. London, United Kingdom and New York, NY, United States: Verso.

Fox, J. G., and O’Maley, P. (2018). Adorno in the classroom: how contesting the influence of late capitalism enables the integrated teaching of academic literacies and critical analysis and the development of a flourishing learning community. Stud. High Educ. 43 (9), 1597–1611. doi:10.1080/03075079.2016.1269314

Goldingay, S, Hitch, D., Carrington, A., Nipperess, S., and Rosario, V. (2016). Transforming roles to support student development of academic literacies: a reflection on one team’s experience. Reflective Pract. 17 (3), 334–346. doi:10.1080/14623943.2016.1164682

Greimas, A. J., and Rastier, F. (1968). The interaction of semiotic constraints. Yale Fr. Stud. 41, 86–105. doi:10.2307/2929667

Harper, R., and Vered, K. O. (2017). Developing communication as a graduate outcome: using “Writing across the Curriculum” as a whole-of-institution approach to curriculum and pedagogy. High Educ. Res. Dev. 36 (4), 688–701. doi:10.1080/07294360.2016.1238882

Hathaway, J. (2015). Developing that voice: locating academic writing tuition in the mainstream of higher education. Teach. High. Educ. 20 (5), 506–517. doi:10.1080/13562517.2015.1026891

Hutchings, C. (2014). Referencing and identity, voice and agency: adult learners' transformations within literacy practices. High Educ. Res. Dev. 33 (2), 312–324. doi:10.1080/07294360.2013.832159

Jameson, F. (1988). The ideologies of theory, essays 1971-1986. in Syntax of history, Vol. 2. Minneapolis, United States: University of Minnesota Press.

Jameson, F. (1989). The political unconscious: narrative as a socially symbolic act. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Lillis, T., and Tuck, T. (2016). “Academic literacies: a critical lens on writing and reading in the academy,” in The routledge handbook of English for academic PurposesKen hyland and philip shaw (London, United Kingdom: Routledge), 30–43.

Limes-Taylor Henderson, K., and Esposito, J. (2017). Using others in the nicest way possible: on colonial and academic practice(s), and an ethic of humility. Qual. Inq. 25 (9-10), 876–889. doi:10.1177/1077800417743528

McGrath, L., and Kaufhold, K. (2016). English for Specific Purposes and Academic Literacies: eclecticism in academic writing pedagogy. Teach. High. Educ. 21 (8), 933–947. doi:10.1080/13562517.2016.1198762

Murray, N., and Nallaya, S. (2016). Embedding academic literacies in university programme curricula: a case study. Stud. High Educ. 41 (7), 1296–1312. doi:10.1080/03075079.2014.981150

Percy, A. (2014). Re-integrating academic development and academic language and learning: a call to reason. High Educ. Res. Dev. 33 (6), 1194–1207. doi:10.1080/07294360.2014.911254

Pietkiewicz, I., and Smith, J. A. (2014). A practical guide to using interpretative phenomenological analysis in qualitative research psychology. Psychological Journal 20 (1), 7–14. doi:10.14691/CPPJ.20.1.7

Roth, W. M., and Tobin, K. G. (2002). At the elbow of another: learning to teach by coteaching. New York, NY, United States: Peter Lang.

Savin-Baden, M., and Major, C. H. (2012). Qualitative research: the essential guide to theory and practice. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Smith, J., Flowers, P., and Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: theory, method and research. London, United Kingdom: Sage Publications.

Smith, J., and Osborn, M. (2007). Pain as an assault on the self: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of the impact of chronic benign low back pain. Psychol. Health. 22, 517–534. doi:10.1080/14768320600941756

Keywords: academic literacy, square of opposition, higher education, academic support, university cultures

Citation: Hallett F (2021) Contradictory Perspectives on Academic Support: Beyond Linear Logic. Front. Educ. 6:527829. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.527829

Received: 17 January 2020; Accepted: 08 January 2021;

Published: 11 February 2021.

Edited by:

Emily Alice McIntosh, Middlesex University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Hugh Mannerings, Consultant, Edinburgh, United KingdomEve Rapley, University of Greenwich, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2021 Hallett. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fiona Hallett, aGFsbGV0dGZAZWRnZWhpbGwuYWMudWs=

Fiona Hallett

Fiona Hallett