- 1School of Teaching and Learning, College of Education, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, United States

- 2Department of Middle, Secondary, and K-12 Education, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, Charlotte, NC, United States

- 3Department of Theory and Practice in Teacher Education, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Knoxville, TN, United States

The article uses events and narratives from the perspectives of Black women professors as examples of how allyship can be birthed and to illustrate the roles, responsibilities, and risks inherent in allyship development and work. It focuses on the labor needed to establish and sustain allyship as critical anti-racist educators in an Urban Teacher Preparation Program at a Historical White Institution. Dispositions of White allies are discussed, in addition to the various tensions allies may face in creating and sustaining equitable spaces and practices. Considerations for reciprocity are also offered to better support faculty of color.

Introduction

Hudlin et al. (2017), a movie documenting the life of then-young attorney Thurgood Marshall, a traveling attorney who was working for the NAACP, solicits the help of a local White attorney named Sam Friedman to try the case of a Black man who is accused of sexually assaulting and attempting to murder a White woman. In the 1940 case, The State of Connecticut v. Joseph Spell, the initially unwilling Friedman is coerced into working under Marshall’s leadership, and because Marshall, an out-of-state attorney, was forbidden from speaking in court, Friedman became the voice of the trial. As a White man, Friedman could also help ensure that the Black defendant Joseph Spell received a fair trial. Through Friedman’s experience working side-by-side with Thurgood Marshall, an ally and Civil Rights activist was born. In this paper, we refer to the process of Black people working alongside White people to prepare them to serve as allies as the process of ally development.

For both Marshall and Friedman, their work required immense sacrifice. Their contested work led to threats to their physical safety and that of their families. They also risked becoming social outcasts, yet they persisted, and Joseph Spell was acquitted. After the attorneys won the case, Sam Friedman went on to continue to engage in Civil Rights work. This example of allyship is evident throughout history beginning with the underground railroad and White abolitionists who supported the dissolution of slavery (Kendi, 2017).

We share this story as an example of the way in which allyship can be birthed and to illustrate the roles, responsibilities, and risks inherent in allyship development and work. It took the commitment and intellectual work of Marshall and the NAACP to guide Friedman in his work on behalf of a historical legal victory that had broad implications for addressing the vulnerabilities of Black people wrongfully accused of crimes. In this example, Black-White allyship required Marshall and the NAACP to: (1) encourage engagement in social justice work, (2) train someone from the White majority by enhancing their legal knowledge, (3) coach the individual on their courtroom argumentation technique or style of engagement, and (4) assist the individual in dealing with the physical, social, and emotional implications of the work. Furthermore, the work created tensions and moments of friction between the two men as they worked toward the goal of racial justice—a most intense endeavor.

We find this aforementioned process to be quite analogous to our processes for developing white allies. In this paper, we (Coleman-King and Anderson), refer to ourselves Black Women Critical Antiracist Educators (BWCAEs), and describe the work we undertook in leading a program with two White women clinical faculty members, and two White men graduate assistants through a journey endeavored to cultivating allies and maintaining and sustaining a critical urban education program at a Historically White Institution (HWI). In this paper, we specifically highlight the labor of the Black women faculty involved in this process and the tensions inherent in allyship development, specifically considering the labor involved. We share an account of our experiences attempting to develop allies across several groups: teacher candidates, clinical faculty, doctoral students, and school and community partners.

Theoretical Framework

Allyship between Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) and White people has been long heralded as an important strategy for overcoming racial injustice. Allyship allows White people, through their positions of power, an opportunity to use their privilege to create space and advocate for minoritized groups (Tatum, 2007). However, we must ask the question, how do allies come to be? While scholars acknowledge that the road toward allyship can be difficult and contentious (Patton and Bondi, 2015), literature on how to intentionally cultivate allies is sparse and does not highlight the multiple roles embedded in this process and how those roles vary depending on individuals’ identities and positionalities.

In framing this work, we draw from the work of Tatum (2007), who argues that it is important for White people to acknowledge and align with their history in using their privilege to counter oppressive systems. Tatum (2007) states:

It is possible to claim both one’s Whiteness as a part of who one is and of one’s daily experience, and the identity of being what I like to call a “White ally”: namely, a White person who understands that it is possible to use one’s privilege to create more equitable systems; that there are White people throughout history who have done exactly that; and that one can align oneself with that history. That is the identity story that we have to reflect to White children, and help them see themselves in it, in order to continue racial progress in our society (p. 37).

In order to be an active ally as Tatum (2007) suggests, White individuals must not be bystanders, but must act (Sue et al., 2019).

We lean on interdisciplinary research to operationally define White allies as a person who positions themselves as a learner and who possesses positive and affirming attitudes on issues of inclusion and diversity (Broido, 2000); consciously commits to ongoing and purposeful engagement of challenging white privilege (Ford and Orlandella, 2015); disrupts systems and cycles of injustice (Waters, 2010); and who do not see themselves as “saviors” to a measurable end, but aim to dismantle individual and institutional beliefs, practices, and policies that impede the growth of historically minoritized groups (Sue et al., 2019).

In an effort to understand the context in which allyship develops, we draw on Critical Race Theory (CRT) and critical whiteness studies as they help us situate allyship building within a larger framework and help explicate the inherent possibilities and tensions in this work.

Critical Race Theory

At its roots, CRT hinges on the belief that beneath every social structure, institution, and construct, racism exists on some level (Yosso et al., 2001; Delgado and Stefancic, 2017).

Embedded in this is the notion that within every social scenario, institution, and construct, there are positions of power and oppression based upon race that can be investigated critically (Yosso et al., 2001; Delgado and Stefancic, 2017). This is the first tenet of CRT: racism is a normal and permanent aspect of life (Yosso et al., 2001; Delgado and Stefancic, 2017). In other words, racism functions daily as an every-day commonality of American culture, life, and society (Yosso et al., 2001; Ladson-Billings, 2016; Taylor, 2016; Delgado and Stefancic, 2017).

CRT scholars have identified several tenets as central to the ideology and enactment of racism. These tenets include: interest convergence, the role of the voice through counter- narratives/storytelling, the concept of intersectionality, whiteness as property, and the critique of liberalism (Yosso et al., 2001; Bell, 2016; Delgado and Stefancic, 2017). Interest convergence refers to the principle that dominant white power groups will only concede benefits, rights, and privileges to minoritized groups when those benefits also ‘converge’ with the interests of White people (Bell, 2016; Delgado and Stefancic, 2017). The telling of counter-narratives and the role of the voice actively seek to dismantle and revise the dominant narrative by providing explicit examples of experiences with oppression and racism that unsettle white-washed historical representations (Bell, 2009; Ladson-Billings, 2016; Delgado and Stefancic, 2017). The role of narrative voice also demonstrates the ways in which race and reality are socially constructed by allowing individuals the autonomy and space to “name their own reality” (Ladson-Billings, 2016, p. 20). Voice also plays a central role in understanding intersectionality as unique narratives often provide an outlet for individuals to describe how their multiple identities intersect to create unique experiences (Bell, 2016; Delgado and Stefancic, 2017). Lastly, CRT focuses on the critique of liberalism, which addresses advances made through and since the Civil Rights Movement and disputes the rhetoric of meritocracy, color blindness, and post-racialism propagated by liberals and the liberal agenda (Bell, 2016; Delgado and Stefancic, 2017). Additionally, CRT is also founded on a commitment to social justice, meaning that although racism is deemed permanent, we must not cease to work toward ending the subordination of one group by another because of differences related to race, religion, ethnicity, ability, and the like (Cappice et al., 2012).

Several tenets of CRT are particularly useful in helping us understand the concept of allyship and why allyship might be useful in moving forward a social justice agenda: (1) whiteness as property, (2) interest convergence, (3) the critique of liberalism, and (4) intersectionality.

Whiteness as Property

Coined by Cheryl Harris (1993) and accepted widely by CRT scholars, this principle posits that whiteness has been socially constructed such that White skin carries with it an inherent value that can be used to negotiate social networks and amass goods and services that lead to distinct privileges and advantages for White people (Allen, 2004; Ladson-Billings, 2016; Delgado and Stefancic, 2017). As was the case in the movie Marshall, Friedman’s whiteness carried an inherent value, despite his lack of knowledge or skills in trying Spell’s case. Although Friedman’s words and actions were highly prescribed by Marshall, it took Friedman’s whiteness to legitimize Marshall’s ideas to a White audience. Likewise, White bodies continue to possess value and gain recognition when addressing issues related to social justice. This is especially evident in scholarly communities where White scholars receive recognition, fame, and notoriety for engaging in scholarship that BIPOC have been doing for decades (Osayande, 2010).

Interest Convergence and the Critique of Liberalism

Interest convergence, described by Ladson-Billings (2016) as “the place where the interests of Whites and people of color intersect” (p. 19), directly problematizes the concept of allyship. In the academic context, allyship insinuates instances of interest convergence. As conference themes, journal issues, educational initiatives, and academia at large move toward equity and social justice orientations (albeit often superficially), White faculty benefit from allyship because it furthers their own research, careers, and interests. While allyship should not be generalized as an ubiquitous manifestation of interest convergence, awareness of this intersection and its implications are critical to formulating authentic allied relationships. Moreover, when allyship is framed by the critique of liberalism and the liberal perspective, it further problematizes the ally relationship because White people are often the “primary beneficiaries” (Ladson-Billings, 2016, p. 19) of liberal policies and practices that can be derived through allyship.

Intersectionality

According to Delgado and Stefancic (2017), “[intersectionality] means the examination of race, sex, class, national origin, and sexual orientation and how their combination plays out in various settings” (p. 58). CRT scholars recognize that identities often overlap, creating unique experiences with privilege and oppression. However, when people experience multiple minoritized identities, their unique concerns often go unaddressed by mainstream social justice movements, which tend to focus on one particular form of oppression or essentialize minoritized groups. Particularly, Collins (2000) and Crenshaw (1991) employ the concept of intersectionality to explore and better understand how Black women experience marginalization within both race- and gender-based movements, rendering them invisible. One obvious way this plays out in academia is the separation of Black Studies and Women’s Studies on college campuses, neither of which centers Black women (Hull et al., 1982). In the androcentric and ethnocentric setting of the academy, allies must recognize the intersections of oppression that Black women faculty face, which will differ from their own experiences with oppression, and work to center Black women’s concerns and accomplishments.

Relevant Literature

Invisible Labor

As we consider the tenets of CRT, it is important to recognize the positionalities of those involved in the process of developing allies. As we consider these positions, particularly those of Black women, the impact of invisible labor must be examined. Invisible labor according to Crain et al. (2016) is defined as activities that occur within the context of paid employment that workers perform in response to requirements (either implicit or explicit) from employers and that are crucial for workers, yet are often overlooked, ignored, and/or devalued by the employer. Numerous scholars have discussed how invisible labor manifests, and is perceived, particularly amongst minoritized faculty. There are deep gendered divides: gender segregation, stereotyping of jobs, gendered expectations in work organizations and other social arenas, and policing of gender-adequate behaviors (Park, 1996; Crain et al., 2016). While women and faculty of color may work to make the academy a more inclusive space, and study equity as part of their work, this work is often undervalued and can hinder chances for promotion (Bird et al., 2004). Crain et al. (2016) also assert that in addition to service to the university, faculty of color also experience physical and mental health concerns such as anxiety and stress.

Historical Traditions of Black Women’s Labor

Given CRT’s thrust to eradicate the subordination of minoritized groups, we focus our attention on the historical traditions of Black women’s labor. Anna Julia Cooper—educator, feminist, and activist—discussed the intersectional systems of oppression for Black women: racism, sexism, invisibility, and classism (Cooper, 1892). As stated by Cooper (1892), “I speak for the colored women of the South, because it is there that the millions of blacks in this country have watered the soil with blood and tears, and it is there too that the colored woman of America has made her characteristic history, and there her destiny evolving” (p. 712). Cooper argued that Black women have a unique epistemological perspective about the interactions, observations, and actions one might take in confronting and correcting oppressive structures (Gines, 2015).

Parks (2010) too argued that “generations of people—Black, White and just about everybody else—have been raised with the underlying assumption that Black women will save them” (p. xiv). In alignment with Cooper’s (1892) position, Dillard (2012, 2016) calls for Black women to claim and recognize our worthiness from an endarkened epistemology—making sense of our lives against a Black backdrop—even as we endure the pain and frustration of experiencing and bearing witness to oppression. That means, as Black women name our own experiences, we move beyond the often deficit and mischaracterized understanding of our experiences as simply being a singular or “personal” view, and not a result of systemic and structural oppression (Dillard, 2016). As Black women extend and correct misnomers about our labor and position(s) in the academy and other leadership spaces, we affirm that our work matters, and how we center our work matters (Dillard, 2016).

There has been little progress in how society values Black women’s work (Collins, 2013; Dillard, 2016). Black women who choose to enter higher education, face barriers to full participation and success due to widespread systemic racism on college campuses; in addition, there is a lack of representation of Black women in faculty and staff positions on university campuses who could act as role models and/or provide support for students (Hughes and Howard-Hamilton, 2003). For context, of the 176,485 tenured full professors in public and private institutions in the United States, only about two percent are Black women (Pittman, 2010; Esnard and Cobb-Roberts, 2018). The visibility of Black women professors in higher education has been an issue of concern for researchers, feminists, and higher education administrators in the United States (Evans, 2007; Davis et al., 2011; Esnard and Cobb-Roberts, 2018). While Black women are earning more doctoral degrees and entering the academy, they continue to be underrepresented in higher ranks and are promoted at a slower rate than their White counterparts (Evans, 2007; Griffin et al., 2013; Esnard and Cobb-Roberts, 2018).

According to Esnard and Cobb-Roberts (2018), “Black women are valued for their diversification of the educational environment, in terms of both race and gender, but they seem to be penalized for those very same attributes and are further expected to fill a huge void although occupying limited space in numbers” (p. 11). Even with the low number of Black women recruited and retained by institutions of higher education, Black women tend to engage in “care work”— teaching, mentoring, and advising, with the latter being a significant lift. These laborious tasks are masked within broad categories that are not accounted for in the tenure process (Patton, 2009; Crain et al., 2016). Additionally, Black women disproportionately engage in tasks that require emotional labor where they must stifle their own anger and frustrations, but placate and tend to the emotional needs of others (Durr and Harvey Wingfield, 2011).

Using Dillard’s (2016) framework, we use the endarkened epistemology framework by naming and contextualizing our gendered racial experiences through an intersectional lens (Crenshaw, 1991). Black women have discussed their labor in higher education and other educational settings, the cultural taxation of said labor, and the benefits to others as a result of these laborings (Shavers et al., 2014; Boutte and Jackson, 2014). However, few of these analyses move beyond the baseline of their extensive labor and cultural taxation, to discuss the process by which Black women act as conduits of ally development, both within and outside of institutions. Furthermore, few studies address allyship development from the perspective of Black women (Boutte and Jackson, 2014); this work has been operationalized mainly through the eyes of White individuals.

Allyship and Critical Whiteness

Authentic allyship requires an awareness of and understanding of critical whiteness. This framework, informed by CRT tenets, seeks to racialize and problematize whiteness (Frankenburg, 1994; Miller and Starker-Glass, 2018). Within this work, critical whiteness implores us to not lose sight of the racial nature of white existence. It also serves as a reminder to watch for elements of systemic white supremacy and the unearned privilege it bestows. Most importantly, critical whiteness identifies the necessity of avoiding colorblind and ‘racially neutral’ perspectives that often pervade departments, programs, and institutions. Moreover, this racial neutrality fosters and facilitates invisible labor for faculty of color, as their White peers remain blind to the additional burdens faced by faculty of color (Crain et al., 2016).

One recommendation important to White staff and faculty is the need to grow meaningful relationships with people of color. These relationships are paramount for White allies (Allen, 2004). For White individuals to see whiteness, Allen (2004) writes, “they require the spark of knowledge that comes from people of color” (p. 124). Without guidance and relationships from people of color, White individuals will never, “learn how to see the world through new eyes that reveal the complexities and problematics of whiteness” (Allen, 2004, p. 130). Thus, these relationships provide the space for White allies to uncover and begin to perceive the additional labor required of faculty of color. Most scholarship and research on allyship development are through the lens of the White individuals, discussing outcomes of their racial identity interrogations, coupled with action steps for other allies to continuously interrogate the functions of whiteness in Black and Brown spaces, and ways not to perpetuate the exploitation (e.g., labor) of POC in higher education (Leonard and Misumi, 2016; Levine-Rasky and Ghaffar-Siddiqui, 2020).

To that end, there are a small number of urban education licensure programs across the United States—even fewer in the southeast region of the United States— and in these spaces, few are examining allyship development from the viewpoint of Black women (Coleman-King et al., 2019). There have been calls for a critical analysis of teacher preparation programs focused on issues of race, equity, and social justice, particularly at research intensive institutions (Hollins and Guzman, 2005; Labaree, 2008; Zeichner and Conklin, 2008). Additionally, there are few studies focused on the nuances of the programming: delivery, content, implementation in urban schools, and/or the explanation of the cultural taxation associated with the delivery of preparing culturally responsive, anti-racist teachers (Boutte and Jackson, 2014; Henry, 2015). To continue to prepare teachers for urban schools, critical examinations of allyship development through course content and delivery in urban programs must be explored. Mayorga and Picower (2018) argue that teacher education programs should prepare teachers who engage in “active solidarity” with the Black Lives Matter movement by defending public education, providing stipulations for who becomes teachers, and preparing pre-service and supporting in-service teachers whose work aligns with the movement. In addition, critical explorations should address how Black women’s labor is situated in these programs and development, moving the conversation beyond cultural taxation to active conduits of allyship development.

Research Context, Participants, and Questions

This study took place at a historically white university in the southeastern region of the United States. The program was a 5th-year master’s degree program that prepared teachers to teach in elementary schools in urban communities inhabited by racially, socioeconomically, and linguistically minoritized students and their families.

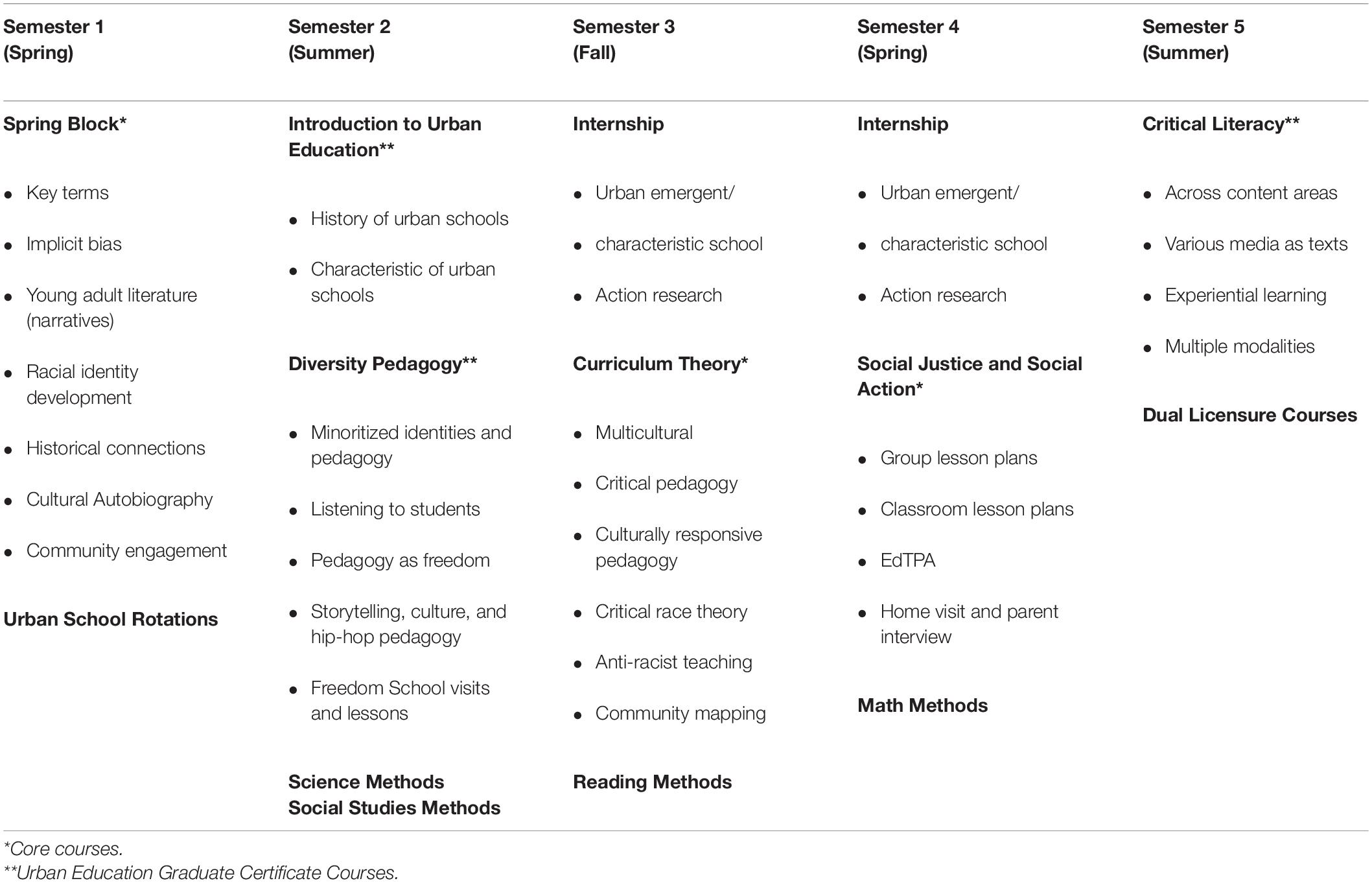

The Urban Teacher Preparation Program (UTPP) required prospective students to engage in an application and interview process where they were expected to demonstrate an interest in teaching in urban schools and some knowledge of issues related to equity and diversity. Once selected for the program, students followed a five-semester cohort model (including two summer semesters) in which they took core classes with their major instructors for at least three semesters and up to five semesters if they enrolled in the Urban Education Certificate program (see Table 1). The three core courses followed a sequential trajectory built on racial identity development theory (Helms, 1990). The first course highlighted the history and trajectory of US anti-Black racism through the use of young adult literature, teacher candidates’ personal beliefs about issues on race and equity, and the development of a cultural autobiography highlighting teacher candidates’ socialization experiences and resultant ideologies they brought to their work. In the second course, the curriculum centered around multicultural and critical theories related to teaching in urban schools such as multicultural education, culturally responsive pedagogy, critical pedagogy, anti-racist teaching, and critical race theory. In the final core course, teacher candidates were tasked with applying the theories from their previous courses to instructional practices in their elementary classroom placements. This included planning and teaching lessons related to critical issues affecting the students they served.

While most of the content taught in the core courses were taught by BWCAEs, clinical faculty (CF) and doctoral graduate assistants (DGAs) attended all classes and taught several course sessions based on their areas of expertise and interest. We functioned as a team, planning, teaching, and collaborating together on research and writing projects. CF and DGAs also mentored teacher candidates in their year-long internship providing support and feedback on the development and implementation of lessons.

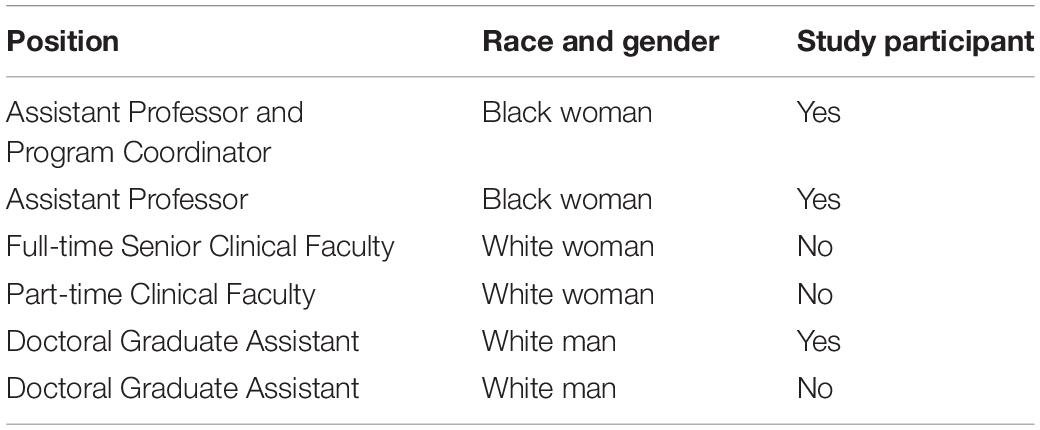

Although each of the additional team members had an interest in and commitment to issues of diversity and equity, the degree to which each person had formal educational training or teaching experience related to these issues varied. Additionally, the racial and gender makeup of the team (see Table 2) was an anomaly in many ways. In a field largely occupied by White women, two Black women held the most senior positions on the team, leading course development, research directions, and university-school-community engagement efforts. The team organization was the reverse of the typical power hierarchy with the Black women at the top, White CF members in the middle, and White men at the bottom. The White male DGAs were selected from a pool of incoming doctoral students due to their expressed interest in issues of equity—they seemed most compatible with the team. Securing BIPOC DGAs would have been highly unlikely in the prospective student pool; however, the White male DGAs represented a numeric minority in the field of elementary education (Ingersoll and May, 2011).

During one of our weekly research meetings, we discussed the unique make-up of our team. This prompted systematic exploration of our relationships to one another, and equity work even as we navigated our racial and gendered positionalities within and outside of the university. The data shared in this paper reflect the narratives and analyses of three of six team members— two BWCAEs and one White male DGA—all authors of this paper, who agreed to collaboratively share our narratives and analyses as part of a larger study examining the UTPP. While this work includes the perspective of a White male DGA, we have chosen to center BWSAEs’ experiences and narratives—a voice that is often missing in scholarship on allyship.

Participants and Positionality

Chonika Coleman-King

I grew up in New York City, the child of Jamaican immigrant parents. As a Black Caribbean-American girl, I keenly was made aware of how I was different from both Black and White Americans. Much of the cultural dissonance I experienced occurred in schools and while I loved the academic aspects of schooling, the cultural and racial hierarchies I experienced detracted from my otherwise positive schooling experiences. These tensions intrigued me and piqued my interest in examining the intersections between race, class, culture, immigrant status, and education and continue to shape my understanding of schools as spaces of both unbridled possibility and overwhelming oppression.

My love of learning and desire to create better educational opportunities for Black children prompted me to become an elementary school teacher. I taught just outside of Washington, D. C. at Title 1 schools where I bridged classroom and community by living in the neighborhood in which I taught and sharing space with families and caregivers in and outside of the school. In my most recent professional roles, I have worked as an urban teacher educator to prepare mostly White women to teach Black and Brown children from economically disadvantaged communities. As a university course instructor, I draw on critical pedagogy (Giroux, 2020) and anti-racist teaching (Love, 2019) philosophies. I am insistent that my students engage deeply in critical theories and apply those theories to practice and research. For me, this work is not merely directed at my students’ job and career preparation, but should also shape who they understand themselves to be within a myriad of systemic structures and their intentionality about how they choose to exist in the world.

Despite the challenges of engaging in this work, I remind myself that if my work helps facilitate praxis, the primary benefactors will be Black and Brown children, and they are worth it. I am also the mother of three Black children and as a result, I still navigate elementary education spaces on a personal level, ensuring my children have rich educational experiences and addressing issues of inequity when they arise. My work is both personal and professional in many ways.

Brittany Anderson

I come to this work using an endarkened feminist epistemology (Dillard, 2012, 2016) to frame my personal experiences as an early career tenure-track professor in an urban education program. I identify as a cisgender Black woman who attended K-12 schools in an urban area, a first-generation college graduate attending HWIs, and as a critical feminist scholar who focuses on the experiences of Black girls and women in educational spaces (i.e., gifted education, talent identification and development). My worldview and approaches to advocating for equitable practices in urban education are influenced by my K-12 and postsecondary experiences in Title I schools and HWIs, background as a general education elementary teacher, and engagement in underserved communities. As a scholar, I position my work in teacher education, focused on how the intersections of gender, race, class, and gifted ability manifest in K-12 settings, with a concentration on talent identification and development of students of color.

My journey through this work has evolved from my roles in leadership positions in K-12 schools, talent development agencies, and now as a consultant, researcher, and professor in higher education. As I unpack the experiences of engaging in teacher preparation programs, schools, community/third-spaces, and grassroots organizations, I lean on my human, cultural, social capital to create experiences and share knowledge with future and current teachers. Using Dillard’s (2016) framework, I demonstrate my ways of being (culture), my ways of knowing (my theory), and ways of leading (culturally engaged) as I analyze and discuss ways that my labor matters, in addition to sharing my racialized realities and experiences in higher education. This work has been a labor of love and commitment to enriching the lives of youth in urban settings, but I also want to share the challenges, benefits, invalidation, and erasure that has occurred as I dedicated my time and energy. As an early career faculty member, it has been challenging to navigate these spaces with so many confounding, systemic, and mediating factors at play.

Nate Koerber

I am a cisgender White male who epistemologically aligns with critical and pragmatic orientations, and whose research focuses on policy, policy implementation, and the ability for policy to promote equitable education. As a former middle and high school ESL (English as a Second Language) teacher and a third-generation immigrant, who was educated in large urban public-school settings, my worldview is rooted in my experiences and my recognition that I benefited from my positionality and the privileges it bestowed. From my time spent as a DGA in the urban education program, my experience as a K-12 teacher, a leader of professional developments focused on equity, and even through my AmeriCorps service, I have been able to utilize my positionality and provide practical support to communities and individuals with whom I have worked. However, I have also witnessed the challenges and additional burdens faced by BIPOC students and in relation to this topic, those faced by Black faculty when engaging in these predominantly white spaces.

Research Questions

This paper focuses on describing the characteristics and processes of allyship development and relationships across four planes: Black women critical antiracist educators (BWCAEs) and (1) teacher candidates (TCs), (2) doctoral graduate assistants (DGAs), and (3) clinical faculty (CF), school partners, and community stakeholders. We are particularly interested in highlighting how allies are cultivated drawing on Freire’s (1970/2000) notion that only the oppressed can help humanize the oppressor. It is by bearing witness to our own oppression and advocating for our humanization that the oppressor, dehumanized through their engagement in oppression, becomes humanized. Drawing on these ideas, we examine our work in relationship with and to, allies and developing allies (WA/DAs). Consequently, our inquiry focuses on the following questions:

(1) What kinds of labor did BWCAEs engage in as a means of developing anti-racist allies across multiple groups such as teacher candidates, doctoral graduate assistants, clinical faculty, and school and community stakeholders?

(2) What themes were most characteristic of BWCAEs’ labor in the ally development process?

(3) How did WA/DAs engage in the ally development process?

(4) What are the implications of BWCAEs’ labor and how might White allies and developing allies engage in a more reciprocal process of allyship development in support of BWCAEs on the tenure track?

Methods

We employ narrative inquiry as a means of exploring the processes by which our work led to the development of anti-racist allies. This work stems from larger efforts to examine our own practice as teacher educators as we simultaneously taught TCs to engage in the inquiry process. Knowledge generated from educator inquiry “is socially, culturally, historically, and institutionally situated in and responsive to [educators’] professional worlds and needs (Golombek and Johnson, 2017, p. 16).” Narrative inquiry provides a space for systematically identifying, naming, organizing, and analyzing one’s own experience, a process that is hugely important to the work of educators and those engaged in the anti-racist project.

According to Liou (2016), CRT rejects notions of neutrality and objectivity, supporting an account of reality that values retrospective accounts as a methodological approach and “challenges master narratives that rationalize social infrastructures, hierarchies and belief systems” (p. 85). Narratives that counter dominant paradigms are critically important to anti- racist work. Narrative storytelling is a reflexive process that centers the stories and analyses of the individuals. Critical race theorists refer to these stories as counternarratives (Solorzano and Yosso, 2002). Through narrative inquiry, or perhaps (counter)narrative inquiry, we work to make meaning of our lived experiences.

Narrative inquiry allows for the analysis of what was, what is, and what could be (Golombek and Johnson, 2017). It creates a space for remembering and creating connections between past and present. This work also aligns with Dillard’s (2016) notions of (re)membering and endarkened feminist epistemology (EFE) that centers (re)searching, (re)visioning, (re)cognizing, (re)presenting, and (re)claiming. We allow space to frame our narratives and lived experiences centering on our intersecting identities as Black women with similar intersecting identities to guide the understanding of our interactions from a Black feminism qualitative inquiry perspective (Evans-Winters, 2019). This perspective seeks to give meaning to important historical events, and how people construct themselves through the past (Yow, 2014). The process of remembering helps the narrator recognize critical moments and generate knowledge about the social meaning of one’s lived experience as informed by one’s race, gender, and other identities (Delgado and Stefancic, 2013).

We used data drawing on personal encounters and conversations within and between racial groups to unpack our experiences, guiding the analyses with our voices (Boutte and Jackson, 2014). We also aim to unpack the understanding of a White male doctoral student about our labor and positionalities in this space, as well as ways he constructs his own understanding of the work regarding equitable practices. Furthermore, we ask in what way(s) does our mentorship help him commit to conscious acts of dismantling cycles and systems of oppression and active self-reflection about his privilege.

For this study, we provide descriptions around a series of events, using narrative inquiry and analysis. According to Clandinin and Connelly (2000), the use of narrative inquiry can assist in unpacking our stories–merging life experience and research. Furthermore, narrative inquiry allows for a study’s purpose to shift and blur and moves away from the convention of maintaining distance from research participants.

In our case, we began this project with the intention of examining allyship relations among our UTPP team as recommended by program DGAs, but later decided to expand the focus to reflect a more comprehensive scope of our work and to center the experiences of the Black women in the group. We used narrative inquiry in our roles as both researchers and research participants together, interrogating our own and each other’s experiences as we worked together to develop allies. We interrogate the functionality of our relationships even as we interface with teacher candidates, doctoral students, colleagues, and community members.

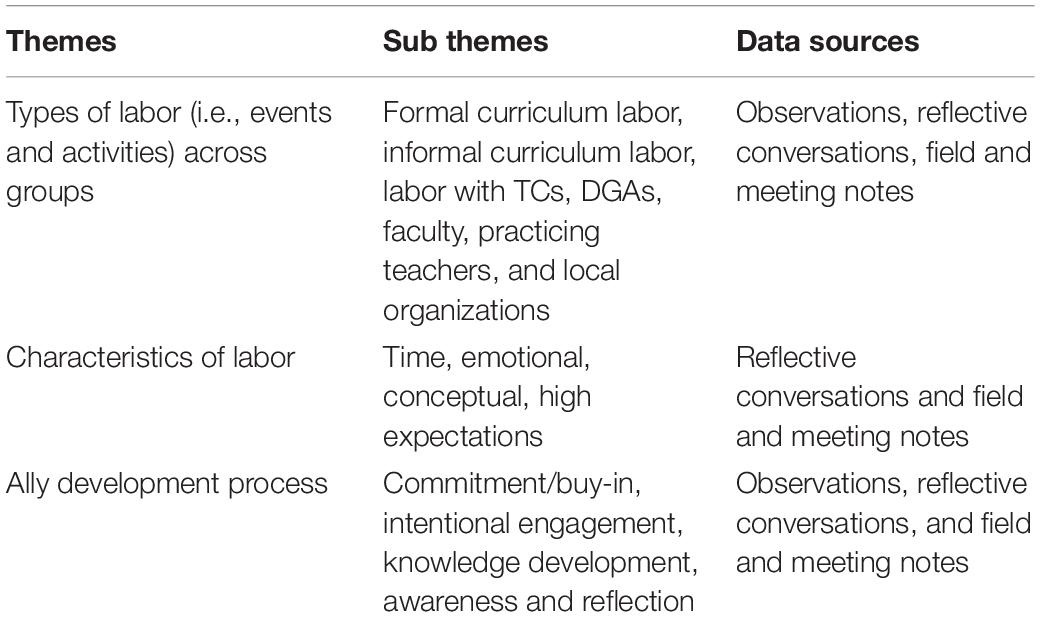

According to Clandinin and Connelly (2000), “There are two starting points for narrative inquiry: listening to individuals tell their stories and living alongside participants as they live their stories”—we engaged in listening and living alongside one another (p. 543). The data sources for this study include reflective conversations between authors as well as documentation of our conversations and activities over the 2 years we worked alongside one another in the UTPP. Reflective conversations were rarely planned, but occurred in response to various tensions and hostilities, new pedagogical ideas, or celebrations of the progress we were seeing in our ally development work. These reflective conversations also included our analyses of experiences that occurred before BWCAEs’ time working together. We often recorded these conversations once we recognized the depth of reflection and how our conversations captured our experiences. Recorded conversations were coded and then transcribed as needed. Data also included reflective journals and field notes from course sessions, UTPP team meetings and retreats, teacher professional development sessions, and community events. Using these data, we underwent inductive and process coding (Saldaña, 2016) and interpreted themes related to our allyship development work (see Table 3). We recognize that our unique lenses, experiences, and positionalities influence how we framed the study and how we interpret the study’s findings.

Boundaries of the Study

One of the limitations of this study is that it is bound by one case that took place within the confines of an urban teacher education program located in a specific geographic region.

While this might limit the generalizability of our findings, we recognize the importance of sharing counternarratives that document the experiences of minoritized groups and ways to advance a social justice agenda. Furthermore, we recognize possible tensions inherent in collaborating with a DGA to describe their working relationship with faculty members.

However, the DGA initiated exploring our unique cross-racial collaboration as a means of identifying the benefits of this type of deeply engaged graduate experience and his mentorship by Black faculty, which mirrors his previous experiences with Black faculty (see Nate Koerber’s positionality statement below).

Findings

In this section of the paper, we share the most salient themes that emerged from our work. We begin by identifying the kinds of labor we engaged in as a means of ally development across multiple constituents such as TCs, DGAs, CF, and school and community stakeholders. While the extensive service labor of Black faculty has been documented extensively (Shavers et al., 2014; Henry, 2015; Brown and Mogadime, 2017; Daniel, 2019), we endeavored to highlight the kinds of activities BWCAEs engage in relative to teacher preparation and demonstrate the expansiveness of our reach. Next, we highlight the nuances of this labor and the role our epistemological leanings, time, emotional investments, and the role of excellence and high expectations. Finally, we identify several key components necessary to ally development processes such as cultivating authentic cross-racial relationships, engaging BIPOC communities, expanding knowledge and skills through a commitment to intellectual study, and ongoing critical reflection and openness to critique.

Labor Across Multiple Constituencies

As previously noted, Coleman-King and Anderson worked alongside multiple White constituents to help build their capacity for allyship or continued allyship across various contexts. In this section of the paper, we describe the formal and informal ‘curriculum’ BWACEs used to engage in anti-racist instructional and leadership practices. We describe the kinds of content, commitments, and activities used to help shape potential allies’ historical knowledge regarding racial injustice and understanding of theoretical frameworks that describe the nature of racism, and modes of engagement both in and outside of the university classroom.

Teacher Candidates

The Formal Curriculum

In the UTPP, we engaged in both formal and informal curriculum geared toward preparing teachers that not only understood the inequities their students faced, but were well poised to enact change on individual and institutional levels. In an effort to realize these goals, we had to move beyond the traditional expectations of what students’ time with us might entail and the norms of engagement placed on teacher candidates in other elementary education programs in the larger department. We define the formal curriculum as that which was included on the course syllabus and recognized as a contractual agreement between the students and their instructors—the ‘non-negotiables’ of courses as well as programmatic and institutional requirements.

As a program, the UTPP was tasked with ensuring that TCs were well prepared in the basics of elementary teaching (e.g., lesson planning, classroom management, parent-teacher communication, etc.), while also creating space to enhance their preparation as culturally responsive, anti-racist teachers (see Table 1). In essence, we were preparing teachers to recognize and incorporate, “the rich and varied cultural wealth, knowledge, and skills that diverse students bring to schools” (Howard, 2006, p. 67), and also seek to empower students by critically deconstructing curriculum, conceptions of knowledge, and confronting the historical and current ramifications of racism in schools and society (Kailin, 2002). Although we were allotted the same amount of course time as the other elementary programs, we utilized every space we could within and outside of course time to provide additional instruction relevant to critical issues in urban schools. In classes that were typically reserved as seminars for students to reflect on field experiences, we assigned extensive weekly course readings. This was in addition to TCs’ methods courses each semester and work as interns in elementary schools four full days per week.

We engaged TCs in off-campus activities such as field trips to local historical and cultural sites and had members of community organizations come speak to our class. Additionally, TCs and their mentor teachers attended a series of off-campus professional development opportunities related to culturally responsive experiential learning including a collaborative weekend residential program in the Delancey Mountains and several full-day weekend workshops. Our goal was to ensure that TCs were especially prepared to engage in praxis—the ability to act on their knowledge in substantive ways (Freire, 1970/2000, p. 51) and serve as allies to fellow educators, students, and local BIPOC communities.

The Informal Curriculum

While there were instances where lines between the formal and informal curriculum were blurred, our work with and availability to TCs did not end with instructional class time. We readily made ourselves available to support TCs by attending special programming at their school placements like assemblies or viewing important lessons on critical issues (outside of scheduled teaching evaluations). In addition to attending local meetings where TCs and alums spoke, we also planned and attended social events like game nights and dinner parties to help build and maintain a sense of community within and between UTPP cohorts and ourselves. We began each semester by welcoming students to the UTPP family.

In addition to our support of current students, we also maintained relationships with alumni who would reach out to us with questions about teaching resources or ways to address systemic challenges like the school districts’ refusal to build a new school in a low-income community serving Black and Brown children despite the school being overcrowded and subject to regular gas leaks that led to school cancelations. Amanda, who we continued to mentor, invited UTPP faculty to attend the school board meeting the evening she decided to share her concerns with the school board. Following the meeting BWCAEs had the following exchange:

Chonika

I really wanted to go support Amanda at the school board meeting last night, but I have been away from the kids for the last few days. I didn’t want to come home late again. How was it?

Brittany

She did really well! I am so glad I had a chance to go support her. I am amazed that she spoke up even as a new teacher.

Chonika

Yup! This is what we have been preparing them to do–to take risks and advocate for students. Our students make me so proud!

Situations where TCs and alums took risks to challenge the power structure often required multiple phone calls, meetings, and emails with BWCAEs to develop problem-solving strategies. All of this work was outside the scope of the formal curriculum, but supported WA/DAs’ agency and promoted equitable change within the schools and the local community.

Doctoral Graduate Assistants

In addition to working with TCs, which was our primary instructional role in the department, there were DGAs who were assigned to the UTPP to work as TCs’ mentors during their 1-year placement in local elementary classrooms. DGAs’ role was strictly field-based and only required faculty support for clinical responsibilities. However, as a part of this work, we believed it was imperative for DGAs to fully understand the thrust of the UTPP and the kinds of teaching we expected to see from TCs—teaching that reflected the critical theories we addressed in class. As was the tradition of the program before BWCAEs joined the faculty, DGAs were required to attend all weekly seminar course sessions designed for TCs, usually the equivalent of one or two three-credit courses per week. An indirect result of this was that our DGAs were given first-hand exposure to our teaching of critical issues across the entire UTPP core curriculum. In addition to attending courses, DGAs also attended planning meetings prior to the start of each semester where we planned the course syllabus and also attended monthly program meetings to discuss the TCs’ progress and conduct program-related business. This created an opportunity for DGAs to experience all phases of the course planning and implementation process—a key experience for doctoral students who are generally required to teach collegiate courses with little to no formal instruction in teaching at the post-secondary level (Austin, 2002). Furthermore, this gave DGAs experience in planning for and teaching in a niche area of teacher education that centers race, class, language, ability, and immigrant status in urban schools.

According to Picower (2009) and Sue (2017), course content that disrupts students’ ways of seeing the world is often met with resistance—a tenuous tension for instructors to navigate.

This resistance also intensifies based on the intersecting identities of the instructor. Generally, instructors with one or more minoritized identities, like Black women, receive the most resistance when teaching material that challenges the status quo (Treitler, 2016). In observing course sessions, DGAs had the opportunity to see how Black women professors maneuvered around TCs’ moments of disruption and discontentment, and continued to challenge students in ways that were supportive but did not undermine the values of anti-racist teaching.

BWCAEs were very clear about being intentional regarding how we mentored students especially since there was not a departmental culture around doctoral mentorship. In one conversation Chonika argued,

I am not sure what they are doing here about mentoring students, but students who work in our program should be well-prepared for the job market. We should be having regular research meetings. Before [DGAs] graduate, they should have experiences doing research, publishing, and presenting at conferences. They can take an independent study course to get credit for their work.

We scheduled weekly 3-h working meetings with DGAs where we came together to check in about how DGAs were doing in their courses, and to discuss any challenges they might have been having as they mentored TCs in their field placements. However, the main thrust of our meetings was to help guide DGAs in the process of developing their skills and identities as researchers whose scholarship centered critical issues. It was during these meetings that DGAs engaged in the process of conceiving and enacting a study from start to finish—including developing research questions, selecting appropriate research methods, securing institutional review board (IRB) permissions, collecting and analyzing data, and preparing papers for conferences and journal submissions. Most importantly, all of our projects centered around topics like culturally responsive experiential learning (Anderson and Coleman-King, 2020), urban teacher education curriculum, and developing culturally responsive practicing teachers through professional development. DGAs were invited to assist in research projects and professional development sessions. In the midst of and beyond the work of teaching and research, we also reserved time for a summer retreat where we stayed in cabins and worked to refine the content and goals of the UTPP to ensure the program’s alignment with the kinds of outcomes we had hoped to see in TCs. We also reserved time to socialize and bond as a team.

Faculty, Practicing Teachers, and Local Organizations

Our work in developing anti-racist allies extended beyond our responsibility to students and included our work with fellow faculty, local educators, and community organizations. Due to the structure of our program, CF also joined Friday seminars where they observed BWCAEs teach core courses. In fact, over the years, CF often remarked that they felt like they were auditing a course because they learned so much from our class sessions. While CF members had significant experience as teachers and teacher educators, they received little to no formal training in issues related to equity and diversity beyond that of their own self-directed reading and personal interests. In attending meetings with CF, BWCAEs would often have to advocate for and defend particular positions related to student assignments and course requirements that might have been deemed unnecessary or seen as competing with others’ academic interests given constraints on instructional time. Beyond the UTPP, we were expected to serve as the voice for diversity and equity issues on departmental, college, and university committees, where our ideas were often met with resistance. For instance, we were asked to evaluate a potential program collaboration, and after highlighting several significant failings of the program, our dissent was rebuffed.

University faculty and local organizations also relied heavily on BWCAEs to gain access to the local Black community and help recruit for their programs and research projects. In a similar vein, community organizations who had been historically isolated from the university community, relied on BWCAEs to provide access to university resources to support programming in Black and Brown communities. This required regular communication and network building as we acted as intermediaries between the two communities, often with direct benefits to those entities and limited recognition of our role in helping to create, maintain, and sustain vital partnerships.

The Many Facets of Black Women’s Labor

Data from this study elucidated the multifaceted ways in which both BWCAEs and WA/DAs worked toward advancing social justice aims. Evidence shows that the process of allyship building and development required a significant amount of labor from both groups— labor that became inextricable from individuals’ personal identities and commitments. Social justice work is not simply about amassing and utilizing knowledge and skills in particular contexts, but creating a new self and lifestyle that integrates issues of equity into daily considerations and lived experiences. Although these commitments were evident for both BWCAEs and WA/DAs, the ways in which this played out for each group varied. Below, we document themes that surfaced demonstrating the kinds of labor that went into meeting an imagined end—one characterized by ongoing praxis endeavored toward equity and justice.

In coding data related to the ally development work of BWCAEs, several themes emerged as central characteristics of their work: (1) An inordinate time commitment through voluntary and involuntary means, (2) use of often taken-for-granted intellectual and experiential expertise, (3) significant emotional labor, and (4) holding WA/DAs to high expectations. The most evident of the themes is one that has been widely documented as characteristic of Black women’s work in the academy. By naming and coding the litany of ways we used our time as BWCAEs, it became increasingly evident that our commitment to and involvement in ally development was its own full-time job.

Time Commitment

Although the time that BWCAEs put into our ‘work’ was significant, the time commitment was difficult to quantify due to the flexible nature of academic positions, but also because our commitments to supporting others in their development as anti- racist allies was both personal and professional. How we chose to spend our time was voluntary. There seemed to be no line of demarcation between our formal work as academics and educators and the work we did beyond the parameters of our official teaching and scholarship requirements. As previously indicated, we created both formal and informal structures for supporting TCs, DGAs, CF, and other community members which required planning for and teaching courses, attending meetings outside of class time, and responding to phone calls and emails during personal time as issues and needs arose. Furthermore, this support was not only made available to currently enrolled students, but program alumni who had graduated from the program within the last 7 years.

In addition to the time voluntarily spent engaging WA/DAs, there were additional expectations placed on BWCAEs. It was also expected that BWCAEs would serve on university committees or engage in service work that enhanced the appearance of the institution’s commitment to equity and diversity, without a genuine desire to shift the status quo. Though some might argue that agreeing to these commitments were voluntary, pre-tenure faculty, who were also members of minoritized groups, were vulnerable to retaliation (whether imagined or implied) for not adhering to colleagues’ requests. These dynamics caused further tensions as BWCAEs were essentially forced into spaces where they were expected to be present and ensure inclusivity, yet our insights were not valued and our recommendations were often overlooked, and in many instances we faced retribution for holding colleagues accountable for actualizing purported goals.

Sharing Knowledge

Beyond the use of our time, allyship development also required a significant use of our intellectual, experiential, and embodied knowledge. In the movie Marshall, Friedman was wholly unprepared to engage in antiracist work. What he learned was not of his own volition, but by Marshall openly sharing the knowledge, skills, and expertise that he had worked hard to attain over many years and through struggles and trials he experienced as a Black man pursuing higher education in a society built on white supremacy and racism. Similarly, BWCAEs worked their way through HWIs, where we routinely encountered racism in and outside of the classroom, while trying to access knowledge and skills that were not always readily available through traditional course listings. While we shared our knowledge willingly and in the service of a larger cause, our unique expertise was often taken for granted. We regularly encountered individuals who believed that social justice work simply requires good intention or membership in a minoritized group, rather than significant training, intellectual rigor, and professional expertise.

This expertise goes beyond content knowledge to include expertise regarding how to engage in anti-racist pedagogy and ally development that led to productive change. This knowledge includes the ability to lead grassroots initiatives, mobilize groups of people, and bring together collaborative voices to engage in substantive change. The aforementioned results are different from that which we typically see in mainstream institutions where the focus tends to be on shifting knowledge, and perhaps dispositions or creating statements and declarations around diversity devoid of any substantive reform. Critical race theorists warn of this trap in their critique of liberalism (Yosso et al., 2001; Bell, 2016), which ultimately serves the interest of White people who want to give the appearance of equity without having to change the larger power structure.

Emotional Labor

Another critical element of our work was the degree of emotional labor it required. While emotional labor is not a new concept, its role in anti-racist work brings its own set of challenges. Initially defined as the effort, planning, and control necessary to express desired emotion(s) during interpersonal transactions at their job or organizational structure (Morris and Feldman, 1996); emotional labor has come to describe the ways in which certain members of the workforce, particularly women and other minoritized groups, are disproportionately responsible for work that either results in intense emotion or centers the need to address the emotional concerns of others with little recognition or validation of that labor (Bellas, 1999). The kind of emotional labor related to anti-racist teacher preparation and training required regular engagement with and critique of racist systems and structures—much of which are violent, brutal, and cause deep pain. In our classes, we paired deeply moving first-person narratives texts like Copper Sun (Draper, 2012), The Hate U Give (Thomas, 2017), and BUCK: A memoir (Asante, 2014) with traditional academic literature. In the story Copper Sun, Tidbit, a young enslaved boy is taken and used as alligator bait. Coleman-King taught this text while she was pregnant with her son 1 year and reread the text the following year with her months-old son lying in bed next to her. The thought of bearing and rearing a Black son in a world that has historically viewed Black lives as disposable, caused her a great deal of distress. During a class session, she shared:

I noticed that you all did not mention much about Tidbit being used as alligator bait. It’s interesting what resonates with us in texts. I really struggled reading this week’s reading and looking over at my beautiful baby boy sleeping, realizing he could have been taken from me and used as alligator bait and there would not have been anything I could have done about it.

Sharing stories of Black trauma, created its own trauma for BWCAEs as our vulnerabilities as Black people were often on display. However, we believe these personal connections were important to our pedagogical commitments and helped shape our students’ development.

Additionally, we created a social media page where instructors and TCs shared online videos and articles of historical and current events related to course content. In some instances, we shared content as benign as diverse reading lists, but other times, we shared articles of BIPOC being harassed for doing mundane things like wearing a t-shirt with the Puerto Rican flag (Irizarry, 2018) or speaking a language other than English (Bermudez, 2018). As a result, TCs and instructors engaged the harsh realities of everyday people affected by injustices related to race, class, immigrant status, language, and sexual orientation. Both instructors and TCs were often so moved by these realities that on many occasions you could find BWCAEs fighting back tears or despondent due to the sheer gravity of inequities faced by minoritized groups and the unrelenting power of white supremacy. However, the emotional weight was not relegated to professors alone, our vulnerability enabled students’ to also tap into and display their emotions of sadness, anger, rage, despair, and hope.

Emotional labor also went beyond the acute issues being addressed in anti-racist work to the emotional toil necessary to deal with resistant and even hostile TCs, faculty, and others.

Personal attacks directed at BWCAEs occurred through course evaluations, dealing with the need to defend and protect the UTPP program from others who sought to alter the program’s structure or reduce programmatic resources. In a one-sided, ongoing feud, other program faculty complained that they had too many students despite their status as clinical faculty with a more substantive teaching load. They successfully rallied to have UTPP student numbers increased and theirs decreased. This was in addition to having to navigate the academy as Black women, who also experienced regular microaggressions in departmental meetings, social isolation in the larger work environment, and intense scrutiny of our work. As BWCAEs, we engaged in what felt like daily battles in order to defend the UTPP and ourselves, even as we engaged in the most mundane work-related tasks.

High Expectations

Lastly, BWCAEs came to their work with a deep level of resolve to improve the learning conditions of minoritized children. With that, there also came a deep commitment to enhancing and maintaining an effective, high-quality urban education program. This often meant going above and beyond the general expectations of a university professor. The labor of high expectations consisted of regular planning and revisions of programmatic content as evidenced by program retreats, regular team meetings, and ongoing analysis of what was and was not working. Additionally, we worked tirelessly with students to ensure that assignments were meaningful and well-executed, which meant students were able to revise assignments as necessary so that the goals of the assignment were met. For example, in the first core course of the program, we met with each student to discuss their cultural autobiography assignment. Conversations that were supposed to last 15 min each easily doubled in time as students sat sharing deep emotions and personal traumas that shaped their lives. Anderson worked with students to ensure that their action research projects reflected relevant, equity-focused questions, stellar execution, and well-written analyses.

Supporting students to meet high expectations meant lots of individual meetings with students to discuss their work and ideas, multiple iterations of feedback on written assignments, reflection on gaps in student understanding and the development of curriculum to address those gaps. Furthermore, the labor of high expectations required intentional relationship building with TCs that led to one-on-one mentoring relationships. We realized that unlike other faculty, our students and alums’ reputation in the field would be a reflection of us recognizing that Black women and programs with critical content are often under intense scrutiny (especially in politically conservative contexts) and as a result, we had to protect our personal reputations and that of the program. Because of our desire to affect change in schools, we were committed to holding ourselves and others to high expectations, which required more consistent, intense labor on our part. Consequently, we had schools that sought to hire our students annually and without a formal interview. In fact, our former students became the most senior teachers at hard-to-staff schools with high teacher turnover rates, because they had been well prepared for the urban school context.

White Ally Development: The Role of Relationships, Engagement, Knowledge, and Reflection

While data clearly show the significant role of BWCAEs in the development of White allies, it is important to also interrogate the ways in which WA/DAs engaged and experienced in the allyship development process. Data from this study show that significant elements of WA/DAs’ allyship development process included: (1) A notable experience that sparked an interest in issues of race and equity, (2) allowing time and space for authentic engagement with BIPOC individuals, (3) study of historical and theoretical knowledge related to race and racism and current implications, and (4) ongoing opportunities to cultivate self-awareness and reflection.

Cultivating Commitment and Buy-In

Across the various groups of White doctoral students, teachers and TCs, faculty, and community members who were WA/DAs, we found that most individuals committed to allyship had at least one significant experience that informed their impetus for engaging in anti-racist work. For one CF member, her impetus for allyship was prompted by her experience working in a majority Black, low-income school for a great deal of her career. During this time, she built significant, intimate relationships with children, parents, and Black colleagues. It was through these direct relationships and the lens of her social work background that she was able to humanize those she encountered and recognize the role of structural challenges in shaping their experiences.

In another instance, our DGA, reflecting on his implicit biases as a part of a course requirement, and realized that his commitment to anti-racist work also stemmed from significant cross-racial encounters and relationships. He journaled:

During my first doctoral course, we were asked to take the Implicit Associations Test—an assessment that helps identify implicit biases across domains such as race, gender, religion, and age—and share our results, if we felt comfortable. I’ve long recognized we all hold biases, often some we aren’t even aware of. However, my results confirmed this when I discovered I had a moderate preference for Black people. I was certainly a bit taken aback, but upon reflecting, it became clear that this was because at two pivotal moments of my life, Black individuals supported and guided me through trauma I could not have dealt with individually. A Black male elementary gym teacher and two Black professors played vital roles in my achievement, growth, and trajectory in life because they valued me as a person first, and a student second. In fact, the courses I took with the two black professors initiated and solidified my transition from a Biology major to an English major, and when I earned my degree, my area of concentration was in African American Literature because I took any and all courses taught by these two individuals.

While interracial contact is significant in creating opportunities for individuals to want to learn more, it alone cannot prompt antiracist allyship. Individuals must bring a disposition of humility and see their Black counterparts as fully human or at least come to that place through their interactions. Additional experiences included grappling with literature, especially first-person narratives, which also helped to encourage allyship. The use of narrative literature helps support a kind of imagined encounter with an individual. Grappling with the intimacy of narrative texts helped change TCs’ perspectives as indicated by students’ journal entries. Kendra, a UTPP student wrote:

Reading Copper Sun and Monster made…injustices more real. When I read a story written in first-person about a person who experienced these travesties, I have a strong emotional reaction. It’s easy to get bogged down by numbers and statistics, but when you’re faced with someone who actually experiences injustice, it’s hard to turn away.

For TCs, the pairing of first-person narratives with readings that also addressed “the facts,” helped to create a balanced and holistic view of how systemic oppression works on an institutional and personal level. By triangulating personal accounts and statistical data, TCs came to a clear understanding as one stated, “clear discriminatory labels [are] placed on people of color [across all the texts]. Because of skin color, people of color have been viewed in a negative manner, pushing injustice and inequality throughout history.”

Creating Intentional Time and Space for Authentic Engagement

While BWCAEs spent their time engaging in a multitude of ally development activities, the work that appeared most significant to WA/DAs development the extent to which they created time to engage BIPOC communities. Beyond initial experiences that led WA/DAs to pursue allyship, it was necessary for them to continue to engage in authentic experiences with BIPOC on their terms and in their communities and spaces. For the DGAs, their time working with the UTPP provided some of that exposure through their relationships with the BWCAEs, but also through their work in schools and communities. However, DGAs went beyond these school-related spaces to also cultivate personal relationships with members of minoritized groups. For example, Nate regularly played in a diverse soccer league. This was also true of entire UTPP team. In many ways, the personal and professional were blurred as relationship building was key to sustaining the UTPP family and building strong ally relationships. However, relationship cultivation required the participation of all parties involved, which meant DGAs, CF, and TCs often gave of their time to support equity-focused professional development workshops and attend culturally specific social outings. For example, each year for MLK Day, Chonika was invited to conduct a professional development workshop for the local district. Members of the UTPP team would attend to support the sessions by handing out materials, setting up, and contributing to group conversations. It was through engagement in these authentic spaces that their understanding of and appreciation for minoritized cultures grew.

Additionally, authentic engagement led WA/DAs to witness differential treatment firsthand, further strengthening their knowledge of the workings of racism. Allen (2004) emphasized that White individuals will never fully comprehend the “problematics of whiteness” (p. 130) until they form authentic ally relationships. Nate argued,

Through our relationship and work together, I have witnessed how [Black faculty] are inundated with additional requirements for which they receive little to no recognition, and I have witnessed how their scholarship has been subordinated by these excessive burdens. Moreover, even when the labor is recognized, it is often minimized. For instance, after returning from an international conference, where all members of the team gave multiple presentations, other White faculty from the department casually stated that, “it looked like we had fun.” (fieldnote, December, 2018)

Faculty’s comments diminished the value of the experience the BWCAEs provided for DGAs through their scholarship and writing. Additionally, BWCAEs also supported DGAs in getting papers accepted to the fields most distinguished conference–a conference that most faculty in the department did not bother to attend. Crain et al. (2016) highlight the additional burdens faced by BIPOC faculty and WA/DAs witnessed how silent burdens are placed upon BWCAEs, reinforced, and perpetually situated as an unspoken, unacknowledged component of their labor and work responsibilities.

Historical and Theoretical Knowledge and Current Implications

In addition to voluntary means of developing relationships, TCs and DGAs also committed time to the study of critical theories and issues. In many cases, WA/DAs were intentional about enrolling in courses where critical content would be taught like the Urban Education Graduate Certificate program or Critical Race Theory courses. Even then, many went beyond course requirements to engage in additional opportunities to broaden their knowledge. This often included trips to museums, reading relevant literature, attending meetings and talks, and taking on opportunities to engage in activism. Additionally, some TCs began to share literature with their friends and family. One TC, Dannielle, planned a family trip to Washington, D.C. to visit the National Museum of African American History and Culture—a profound experience for her dad who otherwise failed to acknowledge the historical impact of racism and white privilege.

Awareness and Reflection

Finally, the role of ongoing critical reflection was central to WA/DAs continued development and growth. This was the work that WA/DAs had to undergo on their own and when there was likely no one else to hold them accountable. According to Howard (2006), White people have the privilege of remaining in encapsulation and incubation stages of identity development. White people also have the privilege of disengaging from allyship and BIPOC, existing in an oblivious white space. It is through formal and informal reflections that WA/DAs came to recognize how privilege functioned in their lives and resultantly, how this privilege ultimately created disadvantages for BIPOC communities.

According to Nate, “ongoing reflection was crucial to eroding the encapsulation and incubation whiteness affords and to understanding the burdens faced by [BWCAEs].”

Overall, it appeared that WA/DAs experienced a process whereby they were propelled into antiracist work through some profound point of contact (Helms, 1990)—a significant experience, relationship, or medium such as literature, which ultimately led them to become intentional about gaining more knowledge and information about systems of inequity whether through formal or informal means. For example, many of the TCs in the UTPP had indicated that they wanted to study urban education and identified some experiences that led to that decision.

From that point, they gained ongoing exposure to minoritized groups through a variety of mechanisms that provided opportunities to cultivate authentic relationships. However, the real work occurred through regular reflection on their actions, the role of white privilege, and the manifestations of racism, which ultimately led to praxis—changes in actions and the development of new orientations, programs, and processes. These changes included regular engagement in activism, speaking out against racism and inequity, integrating critical and culturally relevant content into their teaching, and maintaining cross-racial relationships.

Discussion

Creating Room for Reciprocity: Considerations and Implications of Allyship Development

In presenting our work on allyship with DGAs at an urban education conference, a Black man in the audience asked, “So, how do you two [Black women] benefit from your labor?” It was a pointed and important question that BWCAEs later engaged in critical reflexivity sessions. As anti-racist educators and professors, we understand that the fruit of our labor benefit our White students and colleagues, but more importantly, they benefit the Black and Brown students these groups engage within K-12 schools, communities, and in institutions of higher education. By sharing our funds of knowledge through engagement in the academy and our daily lives, we provide insights that potential White allies will likely never fully comprehend. However, we understood that this was a weighted question that many of Black women needed to explore. For this paper, we felt that it was important to not only name or experiences, but to also provide insights to others and they contemplate engagement in allyship development.

We draw from our own experiences and interdisciplinary research to provide best practices for allyship development. An ally is not simply supportive of BIPOC communities, wanting to “help”, but an individual who actively chooses to be an agent of change (Ford and Orlandella, 2015). Helms et al. (1990, 2006) identified three types of allies: (1) ally for self-interest: works on individual interventions rather than acknowledging how they are implicated with the larger structural system of racism, (2) ally for altruism: works for members of target groups who he or she sees as victims in a patronizing effort to do the “right” thing, and (3) ally for social justice: works with members of oppressed groups, acknowledges his or her role in the racist system, and connects with other group members. White allies should use this system of development to assess where they are as an ally, and continue to reeducate themselves to work at the highest level. Boutte and Jackson (2014) offered the following guidance for WA/DAs:

1. Silence on issues of racism is not an option;