- 1Faculty of Education, Tokai Gakuen University, Nagoya, Japan

- 2Faculty of Psychology, Tokai Gakuen University, Nagoya, Japan

In order to compare Japanese EFL learners’ lexical knowledge before and after undertaking extensive reading tasks, this study picked up eight words from the reading material and investigated how learners’ perceived relationship between these words changed during the task. Data were collected from 58 Japanese EFL learners who were divided into three groups, each of which was given the same reading material but with different tasks (translation task, multiple-choice question task, and no task (control)). Participants judged the degree of relationship between target words twice, before and after the assigned task. The results revealed that participants in the translation task group tended to find the relationships between the words more easily than the participants in other groups, and they were also more aware of changes in their own ability to recognize word association. In addition, the authors also analyzed the data by using AMISESCAL (Asymmetric von Mises Scaling), a statistical model that visualizes asymmetric relations among elements on a two-dimensional map. Visualization of learners’ lexical network threw some light on the restructuring process of how words were interconnected in their lexical representation.

Introduction

It is widely acknowledged that one of the important aspects of lexical knowledge is how words are organized into a structured whole. However, how such organization is achieved, or how learner’s lexical knowledge can be assessed in this structural aspect has not been sufficiently explicated (Wilks and Meara, 2002). There has been a long-standing discussion whether learning of second language vocabulary could be sufficiently accomplished by extensive reading (Horst et al., 1998; Hulstijn and Laufer, 2001; Laufer and Hulstijn, 2001; Waring and Takaki, 2003; Krashen, 2004; Pagata and Schmitt, 2006; Cobb, 2007; McQuillan and Krashen, 2008; Webb, 2008). Although Horst et al. (1998) claimed the limitation of extensive reading as a method of expanding L2 vocabulary, especially for early stage learners, they also mentioned the possibility for learners to enrich their knowledge of the words they have already known, and to build network linkages between words through extensive reading. Pagata and Schmitt (2006) suggested that various aspects of word knowledge should be treated differently when effectiveness of vocabulary acquisition through reading is discussed, implying nine categories of lexical knowledge by Nation (2001). Waring and Takaki (2003) suggested to the series editors of graded readers that they should not only be overly concerned with presenting new vocabulary but also provide a rich input of already known vocabulary with a variety of collocations and colligations. Although these reading studies have been mainly focusing on acquiring new words, some of them mentioned the important role of reading as a method of deepening vocabulary knowledge. It can be assumed that learners are provided with ample opportunities to incidentally acquire new information about familiar words as well as unfamiliar words through reading, which enables them to establish interwoven associations among those words.

The first author of this study has been trying to explicate and visualize the network properties of learner’s mental lexicon, with a particular focus on the strength and directionality (asymmetry) of links between lexical items by applying recent developments in statistics, namely, Asymmetric von Mises Scaling (AMISESCAL; Shojima, 2011; Shojima, 2012) (Sugino et al., 2015; Aotani et al., 2016a; Aotani et al., 2016b). The present study focused on the development of the linkage between words, and structuring/restructuring process of a learner’s L2 mental lexicon by investigating how words were networked before and after undertaking different kinds of reading task, which, we assumed, would affect the results differently.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 58 Japanese university students majoring in Education (36 males and 22 females, ranging from 18 to 21 years old), who were randomly divided into three groups (see below). Their English proficiency level was between 265 and 525 points on the TOEIC Test.

Materials

Eight target words (container, standard, urgent, service, gift, commercial, delivery, personal) were chosen from the reading material (word types 152, word tokens 306) about the mailing system in India1. These are high-frequency nouns and adjectives in the article, some of which collocate with each other such as gift container, urgent service, urgent delivery, commercial gift, and personal gift, or co-occur in a sentence as shown in Table 1. Other high-frequency nouns such as mail, letter, envelope, post were not used in this experiment because they colligate each other well in everyday life and are not appropriate for the purpose of this study.

Procedure

Experiments consisted of three parts.

Part 1: Participants were asked to judge the degree of relationship between two target words. In order that data can be analyzed in terms of the asymmetrical relationship between two words (AMISESCAL; see below), a perceived relationship of wordA toward wordB and that of wordB toward wordA were separately measured. That means all permutated pair out of eight target words (i.e., 56 pairs) were judged by each participant. The visual analog scales were used for the measurement; participants drew a slash on a line with one end indicating ‘not related (0)’ and the other indicating ‘strongly related (100),’ according to their perceived relationship between two words.

Part 2: A week later, participants were randomly divided into three groups. The first group was given the reading material with partly-translated Japanese, and participants were instructed to complete the translation (RM + TL Group). They were allowed to use dictionaries. The second group was given the same reading material as one in the RM + TL Group with four multiple-choice questions2 about it, which were required to be answered without using dictionaries (RM + MCQ Group). The third group served as the control (RM Group). Participants were given the same reading material as the one in other groups, and instructed to read it without using dictionaries. They were not given any extra tasks. All three groups were instructed to finish their task within 45 min.

Part 3: Immediately after the assigned task, the same procedure as Part 1 was repeated for all participants. After finishing the judgement of the words’ relationships, they were also instructed to self-evaluate how their recognition of the relationship between the target words as a whole was strengthened during the task according to a 10-point scale; from 0 (no change) to 10 (greatly deepened).

Results

Quantitative Analysis

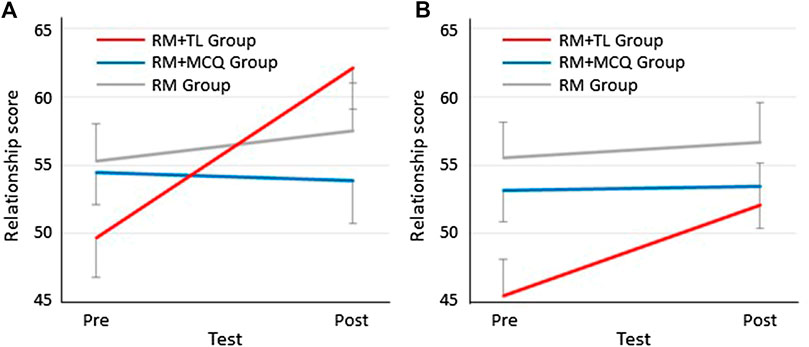

Figure 1 shows mean relationship score in each group before (Pre) and after (Post) the task, separately for the words that collocate with each other (a) and for the words that do not (b). Three-way (group×test×collocation) analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed significant interactions between group and test (F(2,55) = 5.396, p = 0.007, η2 = 0.164) and group and collocation (F(2,55) = 4.873, p = 0.011, η2 = 0.151). Then, two-way (test×collocation) ANOVA was conducted for each group. No significant interaction nor main effects were found in the RM + MCQ Group and the RM Group. In the RM + TL Group, significant main effects of test (F(1,19) = 11.069, p = 0.004, η2 = 0.368) and collocation (F(1,19) = 18.271, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.490) were found, but their interaction was not significant.

FIGURE 1. (A) Words with collocation and (B) Words without collocation. Mean relationship score in each group before (Pre) and after (Post) the task. (Error bars indicate standard error).

For the mean scores of self-evaluation of participants’ recognition change, one-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of group (F(2,55) = 8.899, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.244). Post-hoc analysis revealed that the score in the RM + TL Group (mean 6.85, SD 2.28) was significantly higher than those in the RM + MCQ Group (mean 4.70, SD 2.47) and the RM Group (mean 3.78, SD 2.18).

Qualitative Analysis

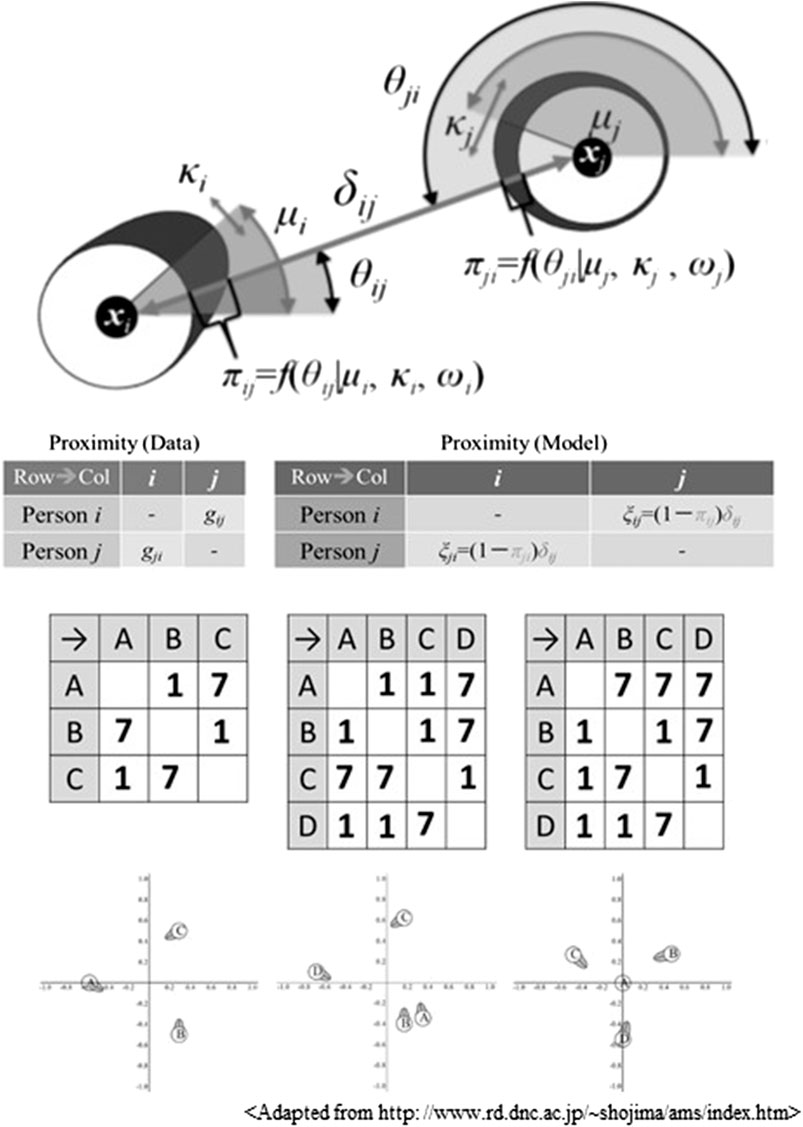

The individual results were analyzed by AMISESCAL, which is an application of directional statistics to visualize the asymmetric structure underlying the data matrix developed by Shojima (2011). It uses the von Mises distribution (vMd) for its normal distribution, and the vMd can be expressed as a function of μ (the Mean Direction Parameter) and ĸ (the Concentration Parameter). Figure 2 depicts the relationship between two items (xi and xj). The relative proximity represents the similarity between the two items, and the size and direction of vMd (πij and πji) shows the asymmetric relationship. As a simple example, compare three diagrams below representing socio-dynamics. The left table shows the relationship among three people whose favorability toward others was rated according to a 7-point Likert scale; from 1 (like very much) to 7 (do not like). It explains that A likes B but not C, B likes C but not A, and C likes A but not B. These asymmetries are represented by the direction in which each vMd is pointing in the left figure. In the middle table, both A and B like C and each other, but they do not like D. However, C does not like either A or B, while D likes them both. These asymmetries in relationships are represented in the middle figure. Note that A and B are positioned close together. In the right table, A is liked by everyone, but likes no one. B likes C but not D, C likes D but not B, D likes B but not C. In this case, A is located in the center because it is liked by all others, and asymmetries in relationships among B, C and D are represented by the direction in which each vMd is pointing in the right figure.

In this study, a pair of any target words, wordA and wordB, is considered to be in an asymmetric relationship if, for certain participant, wordA is perceived as semantically related to wordB but not the other way around. In such a case, wordA will be represented as the vMd pointing at wordB, while the vMd of wordB not pointing at wordA. The great advantage of AMISESCAL is that it can make us visually understand the relationship between the items.

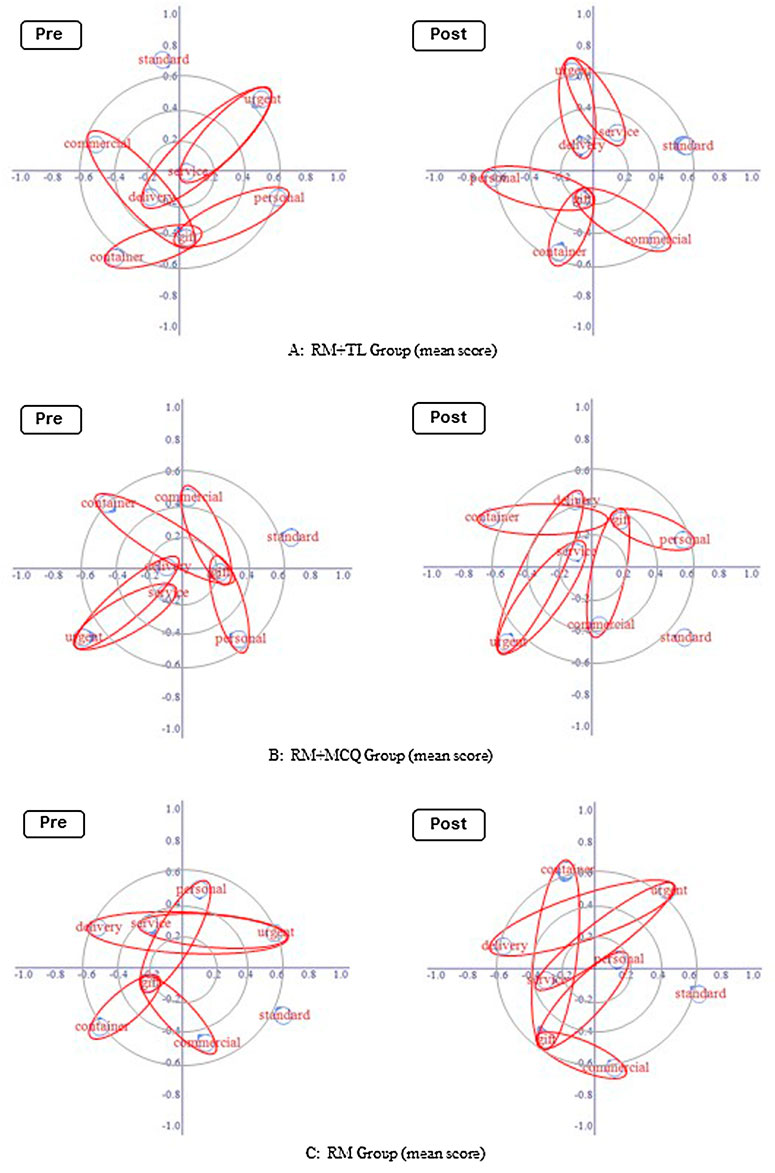

AMISESCAL mapping of each group is shown in Figure 3 (pre-task result is on the left, and post-task result is on the right). The post-task map of the RM + TL Group depicts slightly closer relationships among the eight words than the pre-task map compared to the other groups. Focusing on words that collocate in the reading material, which are circled in red on the maps, it is obvious that the lexical network is reorganized in accordance with collocation in the RM + TL Group.

In the post-task map of the RM + TL Group, delivery and gift are located inside the center circle, showing that these words were judged to have stronger relationship towards and/or from other words. Similarly, service and personal are located inside the center circle of the post-task map of the RM + MCQ Group and of the RM Group, respectively, suggesting the same characteristics as delivery and gift in the RM + TL Group. It could be assumed that the words delivery and gift, as the central concepts in the reading material, were noticed by the participants in the RM + TL Group to have stronger relationship with other target words during the translation task. In the RM + MCQ Group, participants would have regarded the word service as a keyword for answering the multiple-choice questions they have been given. The RM Group showed slightly puzzling results because the word personal is not a central theme in the context. Contrarily, the central words, delivery and gift, are located at a peripheral position. These results may suggest that the keywords relationship has not been properly comprehended by the participants in the RM Group who were not assigned a specific task.

Although the vMds of most words are not salient in all maps, it is interesting to note that the vMd of standard clearly points to service only in the post-task map of the RM + TL Group. This result can be interpreted that the word standard changed its status in the lexical network of eight words because it co-occurs with all other words excepting urgent in a sentence in the reading material (see Table 1). No salient changes, however, regarding the position of standard were found in the RM + MCQ Group and the RM Group.

Discussion

Through this experiment, the authors tried to observe how different types of intervening tasks affect the recognition of relationships between target words which appeared in the learning text, taking words’ collocation into account. As shown in Figure 1, learner’s recognition of the relationship between the words could be strengthened by extensive reading with the translation task, while reading with the multiple-choice question task nor with no-task did not affect leaner’s recognition. As regards the effect of words’ collocation, the results of the RM + TL Group in Figure 1 shows that increase of the relationship score from the pre-test to the post-test is larger in words with collocation than in words without collocation, but this difference was not supported by the significant interaction between test and collocation.

The result of AMISESCAL mapping also demonstrated the reorganizing process of the lexical network. Although the experiments were conducted in a short period of time with only one-time experience of performing the task, the participants in the RM + TL Group could find the relationships between the words more easily than the participants in other groups, and they were also more aware of changes in their own ability to recognize word association. These results indicate that deeper semantic processing (in this study, translation from English to Japanese) plays an important role for the reorganization of the lexical network.

Hulstijn and Laufer (2001) proposed the Involvement Load Hypothesis in vocabulary acquisition inspired by the notion of depth of processing proposed by Craik and Lockhart (1972). They proposed a motivational-cognitive construct of involvement, consisting of three basic components: need, search, and evaluation (also, Laufer and Hulstijn, 2001). Three degrees of prominence are suggested for each of the three factors; no, moderate and strong. In terms of the involvement load, reading the material without any additional tasks would induce no need, no search, and no evaluation; therefore the involvement index in the RM Group would be zero. Reading the material with the multiple-choice question task would induce moderate need, no search (because participants were not allowed to use dictionaries), and no evaluation; therefore the involvement index in the RM + MCQ Group would be one. Reading the material with the translation task would induce moderate need, moderate search, and moderate evaluation; therefore the involvement index in the RM + TL Group would be three, which is the highest among the three groups. According to Hulstijn and Laufer (2001)’s findings, the greater the involvement load, the better the retention of new words. Although this study did not focus on the acquisition of new words but association between already known words, their hypothesis could be applied to the present results in terms of the depth of processing.

Conclusion

When investigating the reorganizing process of one’s lexical network, it is important to see both the quantitative aspect and the qualitative aspect of the learner’s internal change. Whereas quantitative improvement is rather easy to be noticed by both teacher and learner him/herself, the qualitative change is likely to be ambiguous. In this regard, a visualized image like AMISESCAL mapping is very useful and it can help both of them understand the restructuring process of his/her lexical network. Although this study has compared map characteristics of experimentally manipulated groups and their change in a short period of time, further accumulation of data samples and observation over a longer period of time will provide us with more practical information about the effects of various ways of learning that helps the individual learner to improve his/her second language acquisition.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of Tokai Gakuen University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

NA and ST contributed to the design and implementation of the research, to the analysis of the results and to the writing of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (17H02367) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The first author is grateful to her research colleagues for years of collaboration and advice, especially K. Shojima who gave her technical support regarding AMISESCAL.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2020.621437/full#supplementary-material.

Footnotes

1This passage was adapted from the following preparation book for the TOEIC test (see Supplementary Appendix S1). Hilke, R., Wadden, P., and Maeda, H. (2007). New TOEIC test Chokuzen-moshi 3-Kaibun. ALC Press Inc. We selected the passage based on the length, readability and appearance of collocations.

2The multiple choice questions were also adapted from the same book as the passage (see Supplementary Appendix S2).

References

Aotani, N., Sugino, N., Fraser, S., Koga, Y., and Shojima, K. (2016a). An asymmetrical network model of the Japanese EFL learner’s mental lexicon. J. Pan Pac. Assoc. Appl. Ling. 20 (2), 95–108.

Aotani, N., Sugino, N., Fraser, S., Koga, Y., and Shojima, K. (2016b). An investigation into how learning strategies affect the mental lexicon of L2 learners. Proceedings of the 7th CLS International Conference, Singapore, December 3, 8–13.

Cobb, T. (2007). Computing the vocabulary demands of L2 reading. Lang. Learn. Technol. 11, (3), 38–63.

Craik, F. I. M., and Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of processing: a framework for memory research. J. Verb. Learn. Verb. Behav. 11, 671–684. doi:10.1016/S0022-5371(72)80001-X

Horst, M., Cobb, T., and Meara, P. (1998). Beyond a clockwork orange; acquiring second language vocabulary through reading. Read. Foreign Lang. 11 (2), 207–223.

Hulstijn, J. H., and Laufer, B. (2001). Some empirical evidence for the involvement load hypothesis in vocabulary acquisition. Lang. Learn. 51 (3), 539–558. doi:10.1111/0023-8333.00164

Laufer, B., and Hulstijn, J. H. (2001). Incidental vocabulary acquisition in a second language: the construct of task-induced involvement. Appl. Linguistics 22 (1), 1–26. doi:10.1093/applin/22.1.1

McQuillan, J., and Krashen, S. D. (2008). Commentary: can free reading take you all the way? A response to Cobb (2007). Lang. Learn. Technol. 12 (1), 104–108.

Nation, I. S. P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Pagata, M., and Schmitt, N. (2006). Vocabulary acquisition from extensive reading: a case study. Read. Foreign Lang. 18 (1), 1–28.

Shojima, K. (2011). Asymmetric von Mises scaling. Proceedings of the 39thAnnual Meeting of the Behaviormetric Society of Japan, Okayama, Japan, September 11–14, 261–262.

Shojima, K. (2012). On the stress function of Asymmetric von Mises Scaling. Proceedings of the 4th Japanese-German Symposium on Classification, Tokyo, March 9–10, 18.

Sugino, N., Fraser, S., Aotani, N., Shojima, K., and Koga, Y. (2015). Capturing and representing asymmetries in Japanese EFL learners’ mental lexicon: a preliminary report. Stud. Engl. Lang. Educ. 6, 21–30.

Waring, R., and Takaki, M. (2003). At what rate do learners learn and retain new vocabulary from reading a graded reader? Read. Foreign Lang. 15 (2), 130–163.

Webb, S. (2008). The effects of context on incidental vocabulary learning. Read. Foreign Lang. 20 (2), 232–245.

Keywords: Asymmetric von Mises Scaling, extensive reading, Japanese EFL learners, lexical network, task load

Citation: Aotani N and Takahashi S (2021) An Analysis of Japanese EFL Learners’ Lexical Network Changes. Front. Educ. 5:621437. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.621437

Received: 26 October 2020; Accepted: 21 December 2020;

Published: 15 February 2021.

Edited by:

Rebecca Blum Martinez, University of New Mexico, United StatesReviewed by:

Kristin Lems, National Louis University, United StatesJuan Sánchez García, Miguel F. Martínez Normal School, Mexico

Copyright © 2021 Aotani and Takahashi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Noriko Aotani, YW90YW5pQHRva2FpZ2FrdWVuLXUuYWMuanA=

Noriko Aotani

Noriko Aotani Shin’ya Takahashi2

Shin’ya Takahashi2