- 1Educational Science, Salzburg University of Teacher Education Stefan Zweig, Salzburg, Austria

- 2Civic Engagement for the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa College of Social Sciences, Honolulu, HI, United States

Civic thinking and civic attitude require values and norms for social togetherness and social engagement. Service learning and active-citizenship learning are high-impact pedagogies, well-documented as supporting civic-mindedness and a culture of democracy sustainably. Though our study is part of a broader research project, this brief research report already documents the impact of the two pedagogies on civic-mindedness and students' democratic awareness. Through a mixed-method design we implemented a quantitative survey (7 level Likert Scale) of undergraduate student learning outcomes of service learning with 55 students from the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa and 41 students practicing active-citizenship learning at Salzburg University of Teacher Education. We found that the two pedagogies significantly support students' democratic awareness and civic attitudes. In addition to the survey, a qualitative analysis is in progress based on 23 focus group discussions, conducted to detail how the students experience themselves when they take on social responsibility, e.g., when they actively participate in improving their society. Our mixed, but narrowly focused, approach combined with well-established measuring tools and scales is a first study of how to assess Attitudes, one of the four fundamental principles of the Council of Europe‘s Competency Model for a Democratic Culture.

Introduction

Growing populism and new challenges posed by an increasingly globalized world of refugee movements, climate change, pandemics, and other overwhelmingly important issues, make it necessary to focus on democratic action and make the value of democracy and social equity more tangible. It is already a basic tenet of higher education that we not only teach discipline skills, but also critical thinking and other civic skills. The degree to which the value of democracy is recognized, accepted, and practiced is strongly linked to active participation in society, a sense of responsibility, and recognition of a moral obligation. Across continents and diverse systems of education, this insight has been a focus for education for a while.

Finding viable ways of dealing with the need to solve global and local issues have led to an increased focus on this so-called “third mission” of higher education. Indeed, a United States National Task Force on Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement in 2012 published a report entitled “A Crucible Moment: College Learning and Democracy‘s Future—A Call for Action,” in which the task force stresses the need for a strong focus on the civic mission of higher education, beyond workforce preparation. The report argues that,

It is time to bring two national priorities—career preparation and increased access and completion rates—together in a more comprehensive vision with a third national priority: fostering informed, engaged, responsible citizens. Higher education is a space where that triad of priorities can cohere and flourish… [A] socially cohesive and economically vibrant. democracy and a viable, just global community require informed, engaged, open-minded, and socially responsible people committed to the common good and practiced in “doing” democracy. In a divided and unequal world, education. can open up opportunities to develop each person's full talents, equip graduates to contribute to economic recovery and innovation, and cultivate responsibility to a larger common good. Achieving that goal will require that civic learning and democratic engagement be not sidelined but central. Civic learning needs to be an integral component of every level of education (The National Task Force on Civic Learning Democratic Engagement, 2012, p. 13–14).

These viewpoints are echoed globally among educators and, as we will see below, also by the Council of Europe‘s large investment in addressing education for a democratic culture (Barrett et al., 2018; Barrett, 2020).

It has become common that universities and educational institutions take on social responsibility as their third academic mission (Berthold et al., 2010) in addition to traditional teaching and research. How they regard this task for their institution, in what way they tailor learning opportunities, and what answers and solutions they provide for society is up to the individual institutions and mirrored in corresponding development plans of educational institutions (Görason et al., 2009; Carrión García et al., 2012). Experiential learning programs that can promote pedagogical skills (Jacoby, 2015) as well as personal development of students are commonly offered as they can strengthen the work and learning of students, instructors, and educational institutions (Wang, 2013; Hwang et al., 2014).

With our current study, we aim to document specifically how service learning (SL) and active-citizenship learning (ACL) can promote democratic education and support strengthening democratic and civic attitudes and associated values, such as human cultural diversity, democracy, civic-mindedness, social responsibility, knowledge, and critical understanding of the self in society. Though there is well-documented evidence in several meta-analyses and reviews that SL significantly supports social outcomes (e.g., Giles and Eyler, 1994; Hatcher, 2008; Conway et al., 2009; Bringle and Steinberg, 2010; Celio et al., 2011; Steinberg et al., 2011; Warren, 2012; Yorio and Ye, 2012; Moely and Ilustre, 2013) our mixed-methods design aims to give specific insight into students' experiences regarding democratic attitudes and their orientation toward the common good.

Both SL and ACL pedagogies aim to develop democratic and intercultural competence. That means that through SL or ACL students ideally should develop their ability to promote important values, attitudes, skills, and knowledge to respond efficiently and appropriately to the demands and opportunities in democratic and intercultural situations. In SL this can happen in a multitude of ways, often through participation in existing programs or with placement at sites in communities as part of their academic learning, as it does at University of Hawai'i at Mānoa, whereas in ACL, it can happen in the creation of the students' own projects based on community needs, as it does as practiced at Salzburg University of Teacher Education, where ACL is implemented in the curriculum for all primary school teachers. Based on self-regulated learning (Winne and Perry, 2000) students create and design their own service projects which represents a personal challenge. They formulate learning objectives for themselves and the communities they work in, and apply their projects in socially relevant contexts. ACL strengthens students' individual responsibility, when focusing on the public good and enabling a change of perspective through getting to know other living environments (Geier, 2018, p. 162).

The purpose of this joint study is not to compare the two universities and their predominant practices of experiential pedagogies. The two universities are set in different cultural and social contexts and the students come from different disciplines. The study is part of an international, cross-cultural project to inspire and exchange ideas, and documentation of how community engaged work plays a major role for learners as strengthening not only academic, but also pedagogical and personal skills.

The overall study pursues three scientific research questions within our mixed-method design. Question 1 is the focus of this research report. Questions 2 and 3 will be answered through the ongoing qualitative data analysis from the focus group discussions.

(1) What roles do teaching and learning pedagogies like SL and ACL play for civic-mindedness and for strengthening a culture of democracy in students' attitudes toward social responsibility and acting in the public interest?

(2) How do students practice and experience social participation?

(3) Which key factors in the ACL and SL pedagogies can support a deeper understanding of social participation?

Civic-Mindedness and the Role of Service Learning and Active-Citizenship Learning in Supporting Democratic Awareness

The study of being civic-minded goes back to the American psychologist, philosopher, and pedagogue John Dewey, who considered people civic-minded when they had an interest in and awareness of civic or social responsibility and when they did their part to promote social welfare (Dewey, 1927). True to Dewey‘s spirit, Bringle and Steinberg (2010) as well as Hatcher (2008) define civic-mindedness as a tendency or disposition, reflected in an orientation toward the common good in the sense of participating in the community and acting responsibly. In this line of thinking, the Council of Europe defines civic-mindedness as an

attitude toward a community or social group to which one belongs that is larger than one's immediate circle of family and friends. It involves a sense of belonging to that community, an awareness of other people in the community, an awareness of the effects of one's actions on those people, solidarity with other members of the community and a sense of civic duty toward the community (Council of Europe, 2016, p. 12).

When students take on a responsibility for society, they can experience themselves as autonomous social players. Through participation in their society, they gain experience and develop their skills as they contribute to the common good. But to go beyond traditional engagement or volunteering, which is critically important to do, the key question is how to link students' learning experiences with political knowledge, skills and understanding (Kahne and Westheimer, 2003; Annette, 2005) so they contribute to a culture of democracy. This would mean not solely focusing on traditional engagement as implemented in the common pedagogies of service learning or other forms of civic engagement. Rather, it would require looking at the development of democratic values and students' democratic and political learning.

As democratic and intercultural competence is regarded as a key competence of the twenty-first century, it is also crucial for a sustainable future. Democratic competence includes the ability to promote important values, attitudes, skills, knowledge and thinking (Barrett et al., 2018; Barrett, 2020). To be able to respond efficiently and appropriately to the demands and opportunities arising from exchanges in democratic and intercultural situations, attitudes and values are decisive. They can guide action when applying knowledge and can be viewed as an element of professional competence (Opalinski and Scharenberg, 2018). The Council of Europe‘s competence model for democratic culture is intended to strengthen the democratic commitment of citizens and enable individuals to participate in a culture of democracy. It bundles competencies in the four principles of Values, Attitudes, Skills, and Knowledge and critical thinking. In our research and analyses, we focus on the principle of Attitudes, which the model divides into six groups: (a) Openness to cultural otherness and to other beliefs, world views and practices, (b) respect, (c) civic-mindedness, (d) responsibility, (e) self-efficacy and (f) tolerance for ambiguity (Council of Europe, 2016, p. 11; Barrett et al., 2018).

Methods

Design

Our overall study is designed as a focused mixed-methods research project, combining quantitative, and qualitative research and methods to strengthen conclusions (Creswell, 2008, 2015; Steinberg et al., 2013; Holzman et al., 2017), give students a voice, and understand their perspectives of the impact that the pedagogies of SL and ACL have on a culture of democracy, especially regarding civic-mindedness and orientation to the common good.

Sample and Procedure

Before we began our surveys and focus group data collection, we secured Institutional Review Board approval for human subject research. To answer our first research question about what role SL/ACL might have in strengthening students' attitudes toward social responsibility and thereby civic-mindedness and a culture of democracy, we did a quantitative survey with 55 Hawai'i and 41 Austrian students. It was administered as an online survey. All students were able to decide voluntarily to take part in the study. We required students to already work on a SL or ACL project or have finished it. Individual privacy was protected. Thus, participants were anonymous and able to choose to quit the questionnaire at any point. Ninety six students completed the online survey, all of them undergraduates and coming from a variety of disciplines, choosing their own projects within social, cultural, or environmental areas of the societies and communities.

The Hawai'i sample (n1 = 55) includes 35 female/20 male with an average age of 24.50 years. The Austrian sample (n2 = 41) includes 37 female/4 male with an average age of 24.97 years. All students in the Hawai'i sample and 29 of the Austrian sample reported that they had already finished their projects, whereas 12 Austrian students were still working on them.

Measures

The survey is based on two theoretically grounded and empirically validated tested scales: the Civic-Minded Professional Scale, CMP (Hatcher, 2008) and the Civic-Minded Graduate Scale, CMGS (Steinberg et al., 2011). Both scales are well-suited to measure civic-mindedness, which is supported by recent additional evidence regarding the continued relevance of the CMGS (Bringle et al., 2019). In our study we focus on a subset of these scales, and we adapt some of the items to be able to apply the scales for both universities. Additionally, we created a scale of nine items to study the learning outcomes around “common good” perceptions and address civic duty, such as attitudes. This subscale is based on the Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture defined by the Council of Europe (2016, p. 11). We adapted subsets of the descriptors of this validated model and added a suitable Likert scale to them. The subscale sheds light on students' interest in the public good—whether they are aware of the needs of the community around them and worry about the rights or well-being of others in the community. It also focuses on their own role in the community and the responsibilities, duties and obligations associated with it, to what extent they feel a sense of civic duty to the community, and to what extent action is essential for them for the common good.

Our survey consists of 38 closed questions with a response format of 7 level Likert Scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree), some items with negative polarity. Introduction is asking for some demographic information, including the participants' status in and level of involvement with SL/ACL projects, and their gender, age, and majors.

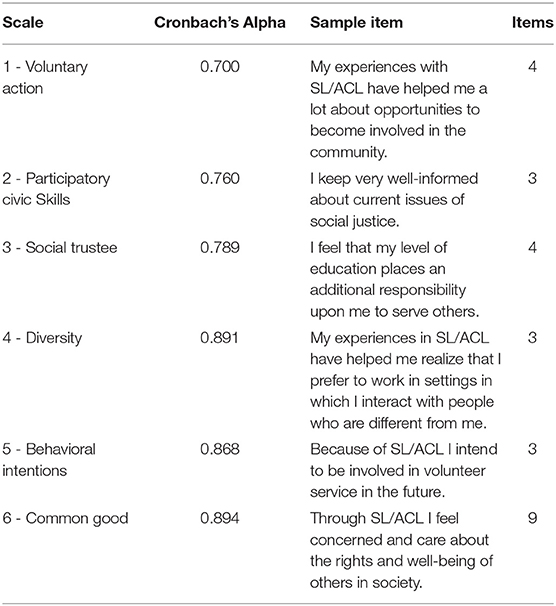

Voluntary Action, based on 3 items from CMP (Hatcher, 2008) and 1 item from CMGS (Steinberg et al., 2011), shows a coefficient alpha of 0.700 (see Table 1) and comprises items on being informed of volunteer opportunities and how to get involved in the community through volunteering just as items on bringing people together to address community needs. Furthermore, there are items on the connection to people who actively contribute to the community and on the extent to which SL/ACL can help support knowledge about volunteering. A sample item of this subscale would be “I feel confident in my ability to bring people together to address a community need.”

Participatory Civic Skills, based on 4 items from CMP (Hatcher, 2008), shows a coefficient alpha of 0.760 (see Table 1) and includes questions on political engagement and citizenship, social justice, public policy, and being informed about current events. A sample item of this scale is “I would describe myself as a politically active and engaged citizen.”

Social Trustee shows a coefficient alpha of 0.789 (see Table 1) and is based on 1 item from CMP (Hatcher, 2008) and 3 items from CMGS (Steinberg et al., 2011). It addresses the knowledge of and sense of responsibility to serve others to improve society and to achieve purposes beyond self-interest. A sample item is “I believe that I have a responsibility to use the knowledge that I have gained to serve others.”

Diversity as a subscale was included with a coefficient alpha of 0.891 (see Table 1) and relates to 3 items from CMGS that are based on an understanding of the appreciation and sensitivity of a pluralistic society (Steinberg et al., 2011). It focusses on the experiences of SL/ACL, for instance interacting with people who are different (from oneself), and on cultural and ethnic diversity. A sample item would be “SL/ACL helps me develop my ability to respond to others with empathy, regardless of their backgrounds.”

The subscale Behavioral Intentions is based on 3 items from CMGS (Steinberg et al., 2011) and shows a coefficient alpha of 0.868 (see Table 1). It includes items about students' intended behavior in the future, e.g., to stay current with news, to participate in political activities, or being involved in voluntary work. A sample item is “Because of SL/ACL I plan to stay current with the local and national news in the future.”

The subscale Common Good was newly developed by the authors. This subscale is based on the Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture (2016, p. 11) adapting subsets of the descriptors. It addresses the identification and feeling of belonging to the community. It also takes into account whether someone is concerned and caring about the rights of others, committed to helping disadvantaged people, and willing to take on social responsibility. Additionally, there are items related to the importance of contributing to a solution to community needs, having a sense of civic duty, and acting for the common good. A sample item is “It is important to me to be able to contribute to a solution in order to respond to community needs.”

Initially, 10 items were developed based on theoretical assumptions. To test the factor structure of this scale empirically, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted. The sample size of the present study does not allow testing the factor structure of all subscales of the questionnaire simultaneously. This will be a task that has to be completed in future studies. The results revealed a one-factor structure of the scale. However, one item (“35/It is not important to me to inform myself about the needs of society; reverse coded.”) did not show a satisfactory communality and factor loading. Therefore, this item was excluded. A subsequent EFA with nine items exhibited good values for all items. Again, a clear one-factor structure for the scale “common good” resulted from the EFA. The explained variance is 58%. All factor loadings are > 0.72. The communalities are > 0.52. A consecutive reliability analysis shows a satisfactory Cronbach's Alpha of 0.894 (see Table 1).

Results

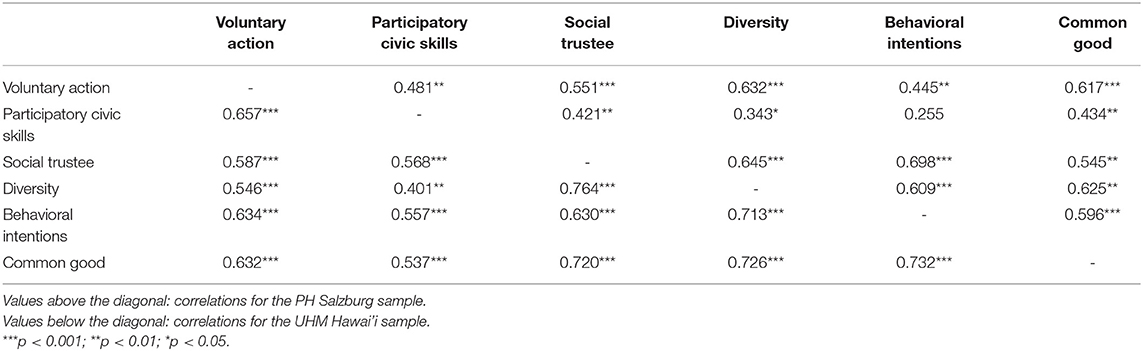

Results from the survey are reported as summarized, group data only. For statistical tests, the alpha level of 0.05 was used. Bivariate correlations were computed to determine existing relationships between two different variables. The table of intercorrelations (Table 2) for the Austrian sample shows that if civic attitude is strongly pronounced and students are civic-minded, then the subcomponents correlate very strongly. The intercorrelations for the Hawai'i sample are positive too, showing a slightly stronger level with higher correlation coefficient than the Austrian sample.

Since research shows that SL and ACL are high-impact practices and can play a crucial role supporting students in living a culture of democracy (Council of Europe, 2016), both pedagogies have potential to support an inclusive and equitable quality education (Wang, 2013; Hwang et al., 2014) and can promote lifelong learning (E3 Project, 2012) as SL/ACL projects help to engage with problem-solving not only for, but also with, the community.

The diagram (Figure 1) shows to what extent SL at the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa and ACL at University of Teacher Education in Salzburg support civic-mindedness. It shows that both pedagogies promote civic-mindedness in various aspects. The Hawai'i sample even at a slightly stronger level. Regarding Voluntary Action (Austria: M = 4.70; SD = 0.92; Hawai'i: M = 5.54; SD = 0.92), the diagram shows that students at both universities consider themselves being well-informed about opportunities for volunteers e.g., how they can get involved. They feel confident, bringing people together to address community needs or see themselves connected to other active citizens. Regarding their Participatory Civic Skills (Austria: M = 4.84; SD = 1.03; Hawai'i: M = 4.89; SD = 1.28), students describe themselves as politically active and engaged citizens who are well-informed about current public policy and current events. In terms of the subscale Social Trustee (Austria: M = 5.01; SD = 1.13; Hawai'i: M = 5.95; SD = 0.96), students feel that their education gives them additional responsibility to serve others. They firmly believe that it matters to achieve goals beyond their own interest, and they report that they have a responsibility to use their knowledge to serve others. Considering Diversity (Austria: M = 4.92; SD = 1.32; Hawai'i: M = 6.11; SD = 0.76), they appreciate their opportunities through SL/ACL to experience interaction with people different from themselves. Thus SL/ACL helps value the enrichment of cultural and ethnic diversity (Bringle et al., 2019) in the community. The connection to Behavioral Intentions (Austria: M = 3.89; SD = 1.48; Hawai'i: M = 5.68; SD = 0.92) is positive, though not significant for the University of Teacher Education in Salzburg (r = 0.309; p = 0.185—see Table 2). Most Austrian students answered that they neither agree nor disagree that ACL helps them to keep up to date with local and national news or they feel motivated to become a volunteer in the future. But acting for the Common Good (Austria: M = 5.19; SD = 0.97; Hawai'i: M = 5.99; SD = 0.69) seems to be very important for students at both universities. It is a worthy goal and desirable for them. Furthermore, students self-report that SL/ACL helps them to get a deeper feeling of belonging to and identifying with the community. They feel concerned about the rights and well-being of others e.g,. disadvantaged people in the community. They furthermore feel committed to fulfill responsibilities associated with their role in the society and agree on having a sense of civic duty to contribute to solutions.

The left diagram in Figure 2 shows that more than 58% of the Hawai'i sample and 63% of the Austrian sample agree that social problems are not too complex for them to solve. Though the diagram relates to a single item of the survey, it shows that students are self-efficient and predominantly positive, and at both programs involve a positive belief in their own ability to undertake actions which are required to achieve particular goals, such as solving problems. Because of their SL and ACL experiences, students self-report that they can have an impact on community problems, though 18% of the Hawai'i and 17% of the Austrian sample are neutral in this matter. The diagram on the right in Figure 2 is even more positive. Based on students' experiences with these pedagogies, 94% of the Hawai'i and 83% of the Austrian sample believe they can make a difference in society. Only 4% of the Hawai'i students and 12% of the Austrian students are neutral in this question and the rest slightly disagree. Associated with feelings of self-confidence, this demonstrates that students believe in their abilities and are positive they can have an impact on community problems and can contribute to society.

Differences between the samples from the two universities, give us a deeper understanding of the students' perspectives. These perspectives will be further analyzed by integrating qualitative data and results from the focus group discussions. Analyses are still in process and therefore not reported in this article. However, based on the students' statements in the discussions and initial results, we expect to find additional indication that Austrian students are more cautious in evaluating their contribution to society. One reason for this might be that ACL is mandatory for all students at the Salzburg University of Education, where students are explicitly required to create their own projects. We expect that the qualitative analysis and our focused mixed-method design will help to explain these differences.

Discussion and Conclusion

Within our mixed-method design, we used a survey based on empirically validated and tested Hatcher's Civic-Minded Professional Scale (2008) and Steinberg et al. (2011), which we extended. We subsequently implemented the new subscale by adapting subsets of validated descriptors of the Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture (Council of Europe, 2016; Barrett et al., 2018; Barrett, 2020), linking these originally validated civic-minded scales with the required attitudes for the competence for a democratic culture. Our work connects existing theoretical bodies of research, and for us constitutes a valuable innovative tool.

Implementing our concept in a learning-outcomes survey with diverse groups of undergraduate students gave us results that verify the conclusion that service learning at the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa and active-citizenship learning at Salzburg University of Teacher Education significantly support a culture of democracy at both universities, independent from particular national and cultural contexts. The Hawai'i sample, even at a slightly stronger level than the Austrian one. Students with experiences in these pedagogies have knowledge about volunteering and are interested in social equity politics and issues (Kolb and Kolb, 2005). Furthermore, it is important for students to contribute to their society with their own competencies. They report they interact and collaborate with people from different backgrounds and have an awareness of other people and their impact regarding their own actions. Of course, the validity of self-reported survey data and small samples must be considered in the results. Therefore, to provide additional evidence, the survey will be continued in order to monitor the programs also in the future, and there will be further analysis of our focus group discussions.

Through taking two well-researched and documented scales and adding an additional subscale to address a sense of civic duty and a need to act for the common good, we now have clear evidence that the pedagogies of service learning and active-citizenship learning can contribute to the current understanding of how higher education can cultivate students' democratic and civic attitude. Learning through engagement and social responsibility, as it happens through service learning and active-citizenship learning, with the words of Steinberg et al. supports “civic growth of students” (2011, p. 15) and has an impact on students' democratic awareness and civic attitude. As expressed by one of the students in the Hawai'i sample: “To be actively involved in society means to identify what your strengths are and how you can use them to help other people, other than yourself.”

Contribution to the Field

Service learning (SL) and active-citizenship learning (ACL) address equity issues and help students strengthen their civic-mindedness and democratic commitment to society. Excellent research has demonstrated the importance of SL in supporting civic-mindedness through education, and several quantitative studies (e.g. Giles and Eyler, 1994; Hatcher, 2008; Bringle and Steinberg, 2010; Steinberg et al., 2011; Moely and Ilustre, 2013) confirm the importance of SL in terms of civic outcomes. Recent studies (e.g., Holzman et al., 2017; Díaz et al., 2019; Manning-Ouellette and Hemer, 2019) apply mixed-method design to gain a deeper understanding of learning outcomes. Building on this work, our research takes the outset in the theoretically grounded and empirically validated Civic-Minded Professional Scale (Hatcher, 2008) and Civic-Minded Graduate Scale (Steinberg et al., 2011), but we employ a subscale to study specifically the resulting sense of civic duty and inclination to act for the common good through focusing our research on attitudes and civic virtues of students. Our more focused study then, creates a deeper insight into students' way of seeing their service experiences in relation to their attitudes and at the same time reveals how SL/ACL supports students in improving skills needed for living a democratic culture.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by IRB Institutional Review Board University of Hawai'i at Mānoa. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

IG and UH collected and analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript.

Funding

The empirical work was supported by a Fulbright Scholarship in 2019/2020 for IG to conduct research at the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Annette, J. (2005). Character, civic renewal and service learning for democratic citizenship in higher education. Br. J. Educat. Stud. 53, 326–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8527.2005.00298.x

Barrett, M. (2020). The Council of Europe's reference framework of competences for democratic culture. Policy context, content and impact. London Rev. Educ. 18, 1–17. doi: 10.18546/LRE.18.1.01

Barrett, M., De Bivar Black, L., Byram, M., Faltýn, J., Gudmundson, L., Van't Land, H., and Zgaga, P. (2018). Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture. Vol.3. Guidance for implementation. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing. Available online at: https://tinyurl.com/urpvnqk (accessed November 4, 2020).

Berthold, C., Meyer-Guckel, V., and Rohe, W., (eds) (2010). Mission Gesellschaft. Engagement und Selbstverständnis der Hochschulen Ziele, Konzepte, internationale Praxis. Essen: Stifterverband für die Deutsche Wissenschaft.

Bringle, R. G., Hahn, T. W., and Hatcher, J. A. (2019). Civic-minded graduate: additional evidence II. Int. J. Res. Service-Learn. Commun. Engagement 7:3. doi: 10.3998/mjcsloa.3239521.0026.101

Bringle, R. G., and Steinberg, K. (2010). Educating for informed community involvement. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 46, 428–441. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9340-y

Carrión García, A., Carot, J., Soeiro, A., Hämäläinen, K., Boffo, S., Pausits, A., et al. (2012). Green Paper. Fostering and Measuring ‘Third Mission' in Higher Education Institutions. Valencia: E3M Project. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.25015.11687

Celio, C. I., Durlak, J., and Dymnicki, A. (2011). A meta-analysis of the impact of service-learning on students. J. Exp. Educat. 34, 164–181. doi: 10.1177/105382591103400205

Conway, J. M., Amel, E. L., and Gerwien, D. P. (2009). Teaching and learning in the social context: a meta-analysis of service learning's effects on academic, personal, social, and citizenship outcomes. Teach. Psychol. 36, 233–245. doi: 10.1080/00986280903172969

Council of Europe (2016). Competencies for Democratic Culture: Living Together as Equals in Culturally Diverse Democratic Societies. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Creswell, J. W. (2008). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

Creswell, J. W. (2015). A concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

Díaz, K., Ramia, N., Bramwell, D., and Costales, F. (2019). Civic attitudes and skills development through service-learning in ecuador. J. Higher Educ. Outreach Engagement 35, 124–144. Retrieved from: https://openjournals.libs.uga.edu/jheoe/article/view/1524

E3 Project (2012). Green Paper. Fostering and Measuring ‘Third Mission' in Higher Education Institutions. Available online at: https://www.dissgea.unipd.it/sites/dissgea.unipd.it/files/Green%20paper-p.pdf (accessed November 4, 2020).

Geier, I. (2018). Active citizenship learning in higher education. Zeitschrift für Hochschulentwicklung 13, 155–168. doi: 10.3217/zfhe-13-02/10

Giles, D. E., and Eyler, J. (1994). The impact of a college community service laboratory on students' personal, social and cognitive outcomes. J. Adolescence 17, 327–339. doi: 10.1006/jado.1994.1030

Görason, B., Maharajh, R., and Schmoch, U. (2009). New activities of universities. Sci. Public Policy 36, 157–164. doi: 10.3152/030234209X406863

Hatcher, J. A. (2008). The public role of professionals. Developing and evaluating the Civic-Minded Professional scale. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from Pro Quest Dissertation and Theses, AAT 3331248.

Holzman, S. N., Horst, S. J., and Ghant, W. A. (2017). Developing College Students' civic-mindedness through service-learning experiences: a mixed-methods study. J. Stud. Aff. Inquiry 3.

Hwang, H., Wang, H., Tu, C., Chen, S., and Chang, S. (2014). Reciprocity of service learning among students and paired residents in long-term care facilities. Nurse Education Today 34, 854–859. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.04.001

Jacoby, B. (2015). Service-Learning Essentials: Questions, Answers, and Lessons Learned. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Kahne, J., and Westheimer, J. (2003). Reconnecting education to democracy. Democratic dialogues. Phi Delta Kappen 85, 8–14. doi: 10.1177/003172170308500105

Kolb, A. Y., and Kolb, D. A. (2005). Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhancing experiential learning in higher education. Acad. Manage. Learn. Educat. 4, 193–212. doi: 10.5465/amle.2005.17268566

Manning-Ouellette, A., and Hemer, K. M. (2019). Service-learning and civic attitudes: a mixed methods approach to civic engagement in the first-year of college. J. Commun. Engage. Higher Educat. 11, 5–18. Retrieved from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1265121.pdf

Moely, B. E., and Ilustre, V. (2013). Stability and change in the development of college students' civic attitudes, knowledge, and skills. Michigan J. Commun. Service Learn. 19, 21–36. Retrieved from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1013493.pdf

Opalinski, S., and Scharenberg, K. (2018). Veränderung inklusionsbezogener Überzeugungen bei Studierenden durch diversitätssensible Lehrveranstaltungen. Bildung Erziehung, 71, 449–464. doi: 10.13109/buer.2018.71.4.449

Steinberg, K. S., Bringle, R. G., and McGuire, L. E. (2013). “Attributes of high-quality research on service learning,” in Research on Service Learning: Conceptual Frameworks and Assessment, Vol. 2A: Students and Faculty, eds P. Clayton, R. Bringle, and J. Hatcher (Sterling, VA: Stylus), 27–53.

Steinberg, K. S., Hatcher, J. A., and Bringle, B. G. (2011). Civic-minded graduate: a north star. Michigan J. Commun. Service Learn. 18, 19–33. Retrieved from: https://scholarworks.iupui.edu/bitstream/handle/1805/4592/steinberg-2011-civic-minded.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

The National Task Force on Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement (2012). A Crucible Moment: College Learning and Democracy's Future. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Wang, Y. (2013). Impact of service-learning courses with a social justice curriculum on the development of social responsibility among college students. J. Commun. Engage. Higher Educat. 5, 33–44. Retrieved from: https://discovery.indstate.edu/jcehe/index.php/joce/article/view/200

Warren, J. L. (2012). Does service-learning increase student learning? A meta-analysis. Michigan J. Commun. Service Learn. 18, 56–61. Retrieved from: https://www.stjohns.edu/sites/default/files/uploads/does-service-learning-increase-student-learning-a-meta.pdf

Winne, P. H., and Perry, N. E. (2000). “Measuring self-regulated learning,” in Handbook of Self-Regulation, eds M. Boeckaerts, and P. R. Pintrich et al. (San Diego, CA: Academic Press), 531–566. doi: 10.1016/B978-012109890-2/50045-7

Keywords: education for the common good, civic-learning, civic-mindedness, active-citizenship learning, service-learning, culture of democracy

Citation: Geier I and Hasager U (2020) Do Service Learning and Active-Citizenship Learning Support Our Students to Live a Culture of Democracy? Front. Educ. 5:606326. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.606326

Received: 14 September 2020; Accepted: 18 November 2020;

Published: 10 December 2020.

Edited by:

Miguel A. Santos Rego, University of Santiago de Compostela, SpainReviewed by:

Concepcion Naval, University of Navarra, SpainJuan Luis Fuentes, Complutense University of Madrid, Spain

Copyright © 2020 Geier and Hasager. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ingrid Geier, aW5ncmlkLmdlaWVyQHBoc2FsemJ1cmcuYXQ=

Ingrid Geier

Ingrid Geier Ulla Hasager

Ulla Hasager