94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 20 January 2021

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 5 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.586709

This article is part of the Research Topic The Role of Teachers in Students’ Social Inclusion in the Classroom View all 16 articles

Drawing on the role of teachers for peer ecologies, we investigated whether students favored ethnically homogenous over ethnically diverse relationships, depending on classroom diversity and perceived teacher care. We specifically studied students' intra- and interethnic relationships in classrooms with different ethnic compositions, accounting for homogeneous subgroups forming on the basis of ethnicity and gender diversity (i.e., ethnic-demographic faultlines). Based on multilevel social network analyses of dyadic networks between 1299 early adolescents in 70 German fourth grade classrooms, the results indicated strong ethnic homophily, particularly driven by German students who favored ethnically homogenous dyads over mixed dyads. As anticipated, the results showed that there was more in-group bias if perceived teacher care was low rather than high. Moreover, stronger faultlines were associated with stronger in-group bias; however, this relation was moderated by teacher care: If students perceived high teacher care, they showed a higher preference for mixed-ethnic dyads, even in classrooms with strong faultlines. These findings highlight the central role of teachers as agents of positive diversity management and the need to consider contextual classroom factors other than ethnic diversity when investigating intergroup relations in schools.

Ethnically heterogeneous classrooms are an important social context for facilitating intergroup contact among students from different social backgrounds. Interethnic classroom experiences can reduce students' prejudice (Turner and Cameron, 2016; Grütter and Tropp, 2018) and foster immigrant students' inclusion in the host society (Stefanek et al., 2014). However, while contact opportunities are an important prerequisite for students' interethnic friendships (Juvonen, 2017; Leman and Cameron, 2017; Graham, 2018), the mere presence of other ethnic groups does not automatically promote positive interethnic interactions (Moody, 2001; Verkuyten et al., 2010). Research has well-documented ethnic homophily, whereby students prefer to affiliate with classmates of the same ethnicity or nationality (Strohmeier, 2012; Bagci et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2014). Strong ethnic boundaries carry a high potential for conflict and isolation, especially for students from ethnic minority groups, as recent international studies indicate (Oxman-Martinez et al., 2012; OECD, 2019). Since social isolation and negative peer experiences can harm student engagement (e.g., Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014), academic achievement (e.g., Ladd et al., 2017), and mental health (e.g., Schwartz et al., 2005), it is important to study social relations in interethnic classrooms.

Previous findings on interethnic relations in the context of increasing ethnic diversity are mixed (Thijs and Verkuyten, 2014; Schwarzenthal et al., 2017): Some studies found positive associations between diversity and cross-ethnic friendships, as well as lower levels of prejudice among majority group students and lower rates of discrimination among minority group students (e.g., Agirdag et al., 2011; Schachner et al., 2015; Titzmann et al., 2015). In contrast, other studies point to a higher risk of peer discrimination among ethnic minorities (e.g., Vervoort et al., 2011; Brenick et al., 2012; Baysu et al., 2014). Recently, researchers have moved beyond analyzing whether diversity is good or bad for interethnic relations and acknowledged that social inclusion requires more than just placing students from different social groups in the same classroom (Thijs and Verkuyten, 2014; Juvonen et al., 2019). Therefore, more recent work focuses on how diversity is dealt with within schools (e.g., Geerlings et al., 2017; Schwarzenthal et al., 2017).

Focusing on teachers' critical role for social inclusion (Juvonen et al., 2019), the current study aims to contribute to this recent work. First, by integrating theories on peer ecologies (e.g., Gest and Rodkin, 2011; Farmer et al., 2019) and research on intergroup relations, we study whether teachers influence interethnic peer relations in the classroom. Previous research has shown that teachers' interactions with students strongly impact how relationships form among students (e.g., Mikami et al., 2012; Farmer et al., 2019). However, there are only very few studies on teachers' role for students' social inclusion in ethnically diverse classrooms (e.g., Thijs, 2017). In order to address this research gap, we study whether perceived teacher-student relationships moderate students' interethnic relations by specifically investigating whether students favor ethnically homogenous over ethnically diverse relationships, depending on how caring they perceive their teacher. Second, we integrate faultline theory from organizational psychology with educational theories on teacher-student relations, which allows us to take a novel intersectional approach to investigating classroom diversity: We measure hypothetical dividing lines between relatively homogeneous subgroups on the basis of student ethnicity and gender, i.e., we measure gender-ethnicity faultlines (Lau and Murnighan, 1998) and use these to predict dyadic relationships, thereby highlighting the role of the overlap of several diversity attributes in diverse classrooms. Faultline research shows that negative consequences of diversity become more likely with strong faultlines—i.e., if subgroups form on the basis of multiple attributes (Thatcher and Patel, 2012; Homan and van Knippenberg, 2015). We assume that teachers' positive interactions with students might serve as a buffer for potential negative effects of faultlines.

Third, on the basis of the notion that processes related to different social categories require theory and analyses at the individual level (van Dijk et al., 2018), we employ a novel methodological approach, namely the analysis of dyadic social networks, to study students' interaction preferences through a personal social network lens (e.g., Snijders and Bosker, 1999). This approach leaves room for ethnic minority and majority group students' differing experiences of classroom diversity, which have rarely been analyzed within the same study (Vervoort et al., 2011; Tolsma et al., 2013; Thijs and Verkuyten, 2014; Leszczensky et al., 2018). This methodology allows us to draw separate conclusions for majority and minority students.

Diversity shapes relationships within classrooms through creating opportunities for cross-group friendships, by creating a power hierarchy among ethnic groups, and through potential intergroup competition resulting from perceived threat (Thijs and Verkuyten, 2014; Graham, 2018). Since ethnic minorities are more likely to become targets of negative peer interactions (e.g., Hughes et al., 2016), interventions to reduce ethnic discrimination have primarily targeted intergroup attitudes of majority group members (e.g., Turner and Cameron, 2016). Moreover, as majority group students usually hold a higher social status than minority group members, majority group students have more decision power over the formation of interethnic friendships (Verkuyten, 2007; Schwarzenthal et al., 2017). In this context, schools are important agents for reducing group biases, as they can provide opportunities for positive interethnic contacts among students (Strohmeier, 2012; Jones and Rutland, 2018; Juvonen et al., 2019). Previous findings show that such diverse opportunities can promote interethnic friendships (e.g., Titzmann and Silbereisen, 2009; Wilson and Rodkin, 2011; Graham et al., 2014; Knifsend and Juvonen, 2014; Jugert et al., 2017), which are strong predictors of improved intergroup attitudes, mental health, and school adaptation (Turner and Cameron, 2016; Graham, 2018).

However, students from different ethnicities do not always form cross-group friendships. Previous findings show strong same-ethnicity biases in friendship selection (e.g., McPherson et al., 2001; Moody, 2001; Titzmann and Silbereisen, 2009; Vermeij et al., 2009; Graham et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2014), particularly among majority group students (e.g., Stark, 2015). This is at least partly due to the fact that ethnic homophily promotes students' shared social identities (Wilson and Rodkin, 2011; Bagci et al., 2014). According to social identity theory, individuals define themselves through their membership with different social groups, which they internalize into their self-concept. As individuals are motivated to achieve and maintain a positive self-concept, they compare and positively distinguish their own group from other groups (Tajfel and Turner, 1979). This intergroup bias is stronger for groups with higher social status, since individuals strive to belong to a positively valued group (Brown and Bigler, 2002).

Contexts where ethnicity is salient render intergroup bias (i.e., the automatic devaluation of outgroup members in comparison to the own ingroup) especially likely (Tajfel and Turner, 1979). Ethnicity can be particularly salient in contexts characterized by low levels of diversity, where a specific ethnic group is in the numeric minority (Bigler and Liben, 2007; Juvonen et al., 2019). In such contexts, there is typically an imbalance of power between members of different ethnicities. The imbalance of power theory (Graham, 2006) assumes that ethnic classroom diversity (i.e., a more balanced representation of multiple ethnic groups) can diminish such negative peer effects as power is distributed more evenly between multiple ethnic groups with an increasing number of groups and with increasing group size. Indeed, ethnic minority group students experience less peer victimization, less loneliness, and feel safer in classrooms with higher levels of ethnic diversity (Juvonen et al., 2006; Agirdag et al., 2011; Graham, 2018).

However, in addition to numerical imbalance, ethnic groups also differ with regard to their societal status (Jackson et al., 2006; Verkuyten, 2007). Thus, when social minorities grow in numbers, they can present a threat for majority group members (e.g., Durkin et al., 2012). According to ethnic group competition theory (Blalock, 1967; Scheepers et al., 2002), increasing levels of diversity cause feelings of threat and social competition among ethnic majority group students (Durkin et al., 2012). In order to maintain their higher status, these students are more likely to affiliate with in-group members (Scheepers et al., 2002; Vervoort et al., 2011). Accordingly, ethnic majority group students show higher same-ethnic friendship preferences with increasing levels of diversity (Kawabata and Crick, 2008; Wilson and Rodkin, 2011; Bagci et al., 2014; Jugert et al., 2017). Moreover, increasing proportions of minority group students in classrooms are associated with majority students' aggressive behavior and discrimination against ethnic minority group students (Verkuyten and Thijs, 2002; Vervoort et al., 2011; Durkin et al., 2012; Barth et al., 2013). In contrast, ethnic minority group students can feel more confident to challenge the out-groups' superiority when their numbers increase, which can in turn lead to more bullying and fights (Jackson et al., 2006; Vervoort et al., 2011; Barth et al., 2013).

Moderate levels of ethnic classroom diversity are especially likely to exacerbate negative peer relations (Bellmore et al., 2012), as they can highlight group distinctions and incite groups to attain higher social positions (Moody, 2001; Brenick et al., 2012). Such dynamics are likely to result in negative peer relations, negative climate (Benner and Graham, 2013), and perceived threat (Duffy and Nesdale, 2008). In this context, a recent study showed that prejudice moderated the relation between diversity and peer victimization (Thijs et al., 2014). Taken together, prior findings show that the salience of perceived group distinctions shapes the nature of interethnic relations in classrooms.

Individuals are more likely to perceive others as members of social groups if several categories align, such that they create clear demarcations between groups with reference to several categories in a given social context (Turner et al., 1987). Organizational psychology calls this alignment of multiple categories faultlines, i.e., hypothetical dividing lines splitting a group of individuals into relatively homogeneous subgroups on the basis of multiple attributes (Lau and Murnighan, 1998). Groups with strong faultlines are characterized by homogeneous subgroups with regard to multiple attributes. For example, a four-person group consisting of two young American women and two older German men is characterized by a strong faultline with regard to age, gender, and nationality. Faultlines exacerbate intergroup bias between subgroups and lead to group conflict in organizations (see Thatcher and Patel, 2012, for a meta-analysis). Specifically, other demographic attributes than ethnicity, such as gender, have been found to increase tensions between ethnic groups if these other categories align with ethnicity, i.e., in the case of faultlines with regard to ethnicity or nationality and other demographic attributes (see Carton and Cummings, 2013, for a review). This is also relevant for classroom settings: For example, Turkish girls may have a higher risk for being perceived as out-group members if most of their classmates are German boys—compared to a situation where both groups of Turkish and German students are of mixed gender. In this study, we specifically focus on the overlap of ethnicity and gender because adolescents exhibit strong gender homophily (Veenstra and Dijkstra, 2011). Therefore, if gender and ethnic categories align in classrooms, gender-ethnicity faultlines are likely to exacerbate intergroup bias and conflicts. Moreover, ethnic similarity can be more important for girls than for boys (Baerveldt et al., 2004; Sigal and Nally, 2004), whereby girls from ethnic minorities have a higher risk for victimization and negative perceptions than boys from ethnic minorities (Kistner et al., 1993; Putallaz et al., 2007; Vervoort et al., 2011). Investigating classroom diversity with faultlines also yields to calls for intersectional approaches in the study of classroom diversity (e.g., Ghavami and Peplau, 2012; Juvonen, 2017). In a nutshell, previous research shows that stronger faultlines intensify feelings of cohesion within a given subgroup and increase the devaluation of the “other” subgroup (e.g., Lau and Murnighan, 2005). Therefore, we predict that faultlines on the basis of ethnicity and gender are positively related to ethnic homophily among students, such that students will express stronger ethnic homophily in classrooms with stronger faultlines (Hypothesis 1).

However, the way in which individuals deal with diversity appears to be a stronger predictor for diversity-related outcomes than diversity itself (Juvonen et al., 2019). Given the central role of teachers for social processes in classrooms, we examine the role of teacher-student relationships for students' interethnic relations.

Teachers play a critical role for students' peer experiences and their social acceptance (Juvonen et al., 2019) as they have a strong potential to scaffold positive interactions among students (Farmer et al., 2011; Gest and Rodkin, 2011). Particularly through their interactions with students, teachers are role models for students' social interactions, set norms on how to treat each other, and provide emotional security for openness toward diversity (Hendrickx et al., 2016; Thijs, 2017; Farmer et al., 2019). We believe that this is the case for several reasons.

First, students are highly sensitive to how the teacher interacts with their classmates and infer from these interactions how to evaluate and treat classmates with specific traits or attributes (McAuliffe et al., 2009; Mikami et al., 2010; Farmer et al., 2011). Teachers' praise for a student, for instance, communicates their social value; accordingly, teachers' personal liking for a student predict their social acceptance in the classroom (Hughes et al., 2001). Additional longitudinal evidence from an ethnically diverse sample shows that peer ratings of liking among students are predicted by the quality of teacher-student relationships (Hughes and Chen, 2011; Sette et al., 2019). Therefore, teacher-student relationships have a strong impact on how classmates see each other (Mikami et al., 2010, 2012; Farmer et al., 2011; Hughes et al., 2014; Hendrickx et al., 2016). Moreover, if the teacher positively interacts with ethnic minority group students, they can highlight positive behavior that can disconfirm negative stereotypes (Juvonen et al., 2019).

Second, student-teacher relationships provide orientations and norms on how to treat each other. Thus, by treating students equally positively, independent of their social background, teachers can provide positive role models for dealing with diversity (Mikami et al., 2010, 2012; Thijs and Verkuyten, 2012; Schwarzenthal et al., 2017; Farmer et al., 2019; Juvonen et al., 2019). If students perceive that their teacher encourages students from different ethnicities to get along, there is less ethnic discrimination (Benner and Graham, 2013). Similarly, evidence suggests that pupils in ethnically diverse classrooms report less racist bullying when they trust that their teacher reacts if a student was victimized (Verkuyten and Thijs, 2002). In particular, emotionally supportive teacher-student interactions can inspire students to treat each other with respect and warmth, regardless of any differences in ethnic background. In line with this reasoning, findings show that in classrooms where teachers provided high emotional support to students, classroom hierarchies were less pronounced, such that children with lower social positions had a higher chance to increase their social acceptance (Mikami et al., 2012). Moreover, in classrooms where teachers provide high levels of emotional support, students score higher in social competencies (Brock et al., 2008), show lower relational aggression (Luckner and Pianta, 2011; Merritt et al., 2012), and have more reciprocal friendships (Gest and Rodkin, 2011). Emotional support refers to the degree of care, respect, and confidence in students' abilities, and has been identified as an important predictor for students' social and academic development throughout their school career (Hamre and Pianta, 2005).

Third, if teachers provide high emotional support to students, they not only have a role model for positive relational skills, but students also have a secure base for taking social and emotional risks in peer interactions (Gest and Rodkin, 2011; Luckner and Pianta, 2011). This is particularly relevant for interethnic relations, due to the high tendency to affiliate with peers from same ethnic groups. Exploring relations outside one's ethnicity may require openness toward diversity and may pose a risk for negative peer experiences. If teachers provide emotional security, students can have more positive expectations about intergroup interactions (Geerlings et al., 2017; Thijs, 2017). Supporting this assumption, previous research showed that emotional teacher support predicted acceptance for diversity among students (Sanders and Downer, 2012). A recent study showed that majority group students' perceived closeness to their teacher was associated with positive ethnic attitudes toward minority groups, independent of classroom diversity and even after controlling for multicultural school norms (Geerlings et al., 2017). The authors argued that secure student-teacher relationships result in cultural openness. Teacher-student relationships can be particularly relevant in classrooms with higher ethnic tensions. For example, a study with preadolescents suggests that perceived closeness and warmth with the teacher had a protective effect on ethnic minority group students' outgroup attitudes in relatively segregated classrooms (Thijs and Verkuyten, 2012). However, only few studies have investigated the role of teacher-student relationships for students' interethnic relations, and the few existing studies either focused on ethnic minority or ethnic majority groups, but not both in the same study.

In order to provide more insights, we aim to examine the role of teacher care for interethnic relations. Teacher care reflects the degree to which students feel respected, supported, and valued by their teacher and is usually assessed from the perspective of the individual student (Doll et al., 2004). Additionally, perceived care also reflects secure attachment to the teacher (Thijs and Fleischmann, 2015). We thus specifically focus on teacher care to examine how individual perceptions of students' relationships with their class teacher shape their dyadic social networks. In this way, we are able to consider that students from ethnic minority and majority groups may have different perceptions of their teacher.

Teachers' emotional support typically predicts students' perception of teacher care (Gasser et al., 2018). Similar to emotional support, perceived teacher care positively predicts academic and social school adjustment (e.g., Suldo et al., 2009; Wentzel et al., 2010) and positive classroom climate (e.g., Murray-Harvey and Slee, 2010). Accordingly, we predict that perceived teacher care positively relates to students' peer ratings (Hypothesis 2a). Moreover, extending prior work (e.g., Geerlings et al., 2017), we predict a negative relation between perceived teacher care and ethnic homophily, such that higher perceived teacher care relates to less ethnic homophily among students (Hypothesis 2b). Lastly, based on the idea that teachers are particularly relevant in classrooms with strong ethnic biases (e.g., Thijs and Verkuyten, 2012), we hypothesize that perceived teacher care moderates the relation between faultline strength and ethnic homophily, such that high levels of perceived teacher care mitigate negative effects of faultlines on students' interethnic relations (Hypothesis 3).

This study was conducted with early adolescents (i.e., fourth graders, about 10 years old) in German primary schools. Due to concerns about ethnic discrimination, multicultural learning became part of the official school curriculum in 1996 recognizing the potential of schools as agents of change (Civitillo et al., 2016; Schwarzenthal et al., 2017). More than twenty years later, creating school environments that build on diversity remains an important agenda. Germany has a long tradition of immigration; accordingly, classrooms are highly diverse with regard to students' ethnicity (Titzmann et al., 2015). Despite these opportunity structures in schools, cross-group friendships between German and immigrant students are not the norm (Jugert et al., 2011; Titzmann, 2014), whereby similar situations can be found in other European countries (Jones and Rutland, 2018).

Ethnic boundaries become increasingly important during early adolescence as a characteristic to distinguish in-groups from out-groups (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). As a consequence, friendship homophily increases with age (Strohmeier, 2012). In addition, research shows that adolescents take racist incidents less seriously as they get older (Mulvey et al., 2016) and that attention and conformity to peers and group norms increase (Knifsend and Juvonen, 2014). At the same time however, pathways of prejudice are more strongly moderated by the social context (van Zalk and Kerr, 2014). Therefore, by focusing on students at the transition to early adolescence, the current study focuses on a critical period in developing positive interethnic relations among students.

The sample consisted of 1,299 fourth graders (51% girls) from 70 school classes in Germany. The average classroom size was 22.6 children (SD = 3.7). Twenty-eight percent of the children were of non-German background, which means that they did not possess German citizenship. We obtained this information on children's nationality from the demographic part of the survey. Students also provided information about their country of birth. With one exception, all children with German citizenship were born in Germany1. The children without German citizenship came from 37 different countries, predominantly from so-called resettler states2 (i.e., former Soviet Union and other Eastern European states, 42%), Turkey (34%), Southern Europe (12%) or other nationalities including the U.S., Western Europe, and Asian/Arab regions (12%).

For the data collection, a specific approval from the school authorities (i.e., the respective ministry of education) was obtained to contact the schools. In addition, each school board decided whether to participate in the study, and if this was the case, class teachers were informed by their respective principal about the study goals. Written consent of the primary caregivers was obtained, whereby two percent of these primary caregivers refused the participation of their child in the study and these children were visiting other classrooms during the lesson at the time when the data collection took place. Before filling out the questionnaire, the research assistants, specifically trained for this data collection, explained that the study was about students' social experiences at school and how they perceived their peers and their teacher. Children were instructed that their participation was completely voluntary, that there were no negative consequences for non-participation, that there were no right or wrong answers, that they could leave out answers, that they could quit at any time, and that their data was treated confidentially. Besides gender and aspects related to nationality, no personal information was collected and children also rated themselves in the peer ratings to avoid disclosing personal information. The data was completely anonymized shortly after the data collection was completed. The data collection procedure was in line with the APA guidelines and the guidelines of the German Association of Psychology.

Students rated each of their classmates in how much they would like to sit next to this child on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = “not at all,” 4 = “very much”).

We calculated ethnic diversity using the Simpsons' Index, also called Blau Index (Simpson, 1949; Blau, 1977). This index takes the number of different groups and their numerical representation into account and ranges from 0 (i.e., no ethnic diversity, all students in the class are from the same ethnic group) to the maximal number of ethnicities present in the sample (i.e., total cultural diversity: if all the students would be from different ethnicities with an equal presence). For example, in a classroom of 20 students, this value would be 0.95 if all students were from different ethnicities. If there would be 4 ethnic groups with equal presence, the value would be 0.75, and if there would be two groups, with one fourth of them of one ethnic minority group, Simpsons' index would be 0.375. In our sample, we used children's nationality to calculate ethnic classroom diversity, whereby the mean value was 0.41 (SD = 0.18). This value represented that in most classrooms, German students were the numerical majority, while the groups containing children of other nationalities were smaller (M = 0.27, SD = 0.16).

Gender diversity (M = 0.47, SD = 0.05) was represented through Blau's Index, whereby a value of 0 indicates that all the children in a classroom are girls or boys, respectively, and a measure of 0.5 indicates that boys and girls are numerically equally represented.

For each classroom, we computed the strength of the ethnicity-gender faultline that divides the classroom into subgroups with the average silhouette width (ASW) algorithm (Meyer and Glenz, 2013). ASW uses a cluster-analytic procedure to detect possible subgroups and their homogeneity in a group (Meyer and Glenz, 2013). In a stepwise procedure, the members are clustered into similar subgroups, whereby the algorithm first classifies each member as an own subgroup and then subsequently merges them according to their similarity, until there is only one subgroup left: the classroom. Fit measures are calculated for each student and each possible subgroup configuration. The average ASW value represents the average fit of all members to their subgroup. For each classroom, the algorithm chooses the subgroup configuration with the highest ASW value. This value ranges from 0 to 1, where a value of 1 denotes completely homogeneous subgroups. We determined faultline strength across the individual attributes gender and nationality, whereby we specifically focused on nationality as a criterion for social group membership, which has been shown to be important for social identification (Jugert et al., 2011; Titzmann et al., 2015). A faultline value of 1 would represent a classroom where all possible subgroups are completely homogeneous with regards to their gender (e.g., a classroom with only girls with German background and boys with non-German background), a value of 0 would mean that no homogeneous subgroups exist. Indeed, on average, classrooms were characterized by strong faultlines (M = 0.97, SD = 0.04), which reflects a strong tendency for clustering around gender and ethnicity.

Children answered four items from the “Landauer Skalen für Sozialklima” (Saldern and Littig, 1987) regarding their perception of how sensitive and caring their teacher interacted with them (i.e., “The teacher comforts me if something is wrong,” “The teacher cares about me when I have trouble following the lesson,” “The teacher has enough time for me,” “The teacher helps me when I have problems with other students in my class”). The subscale was created in accordance with the concepts of teacher support (van Ryzin et al., 2009) and teacher care (Gasser et al., 2018). Students answered each item on a 4-point Likert-scale (1 = “not at all,” 4 = “very much”), ω = 0.70, M = 2.45, SD = 0.57.

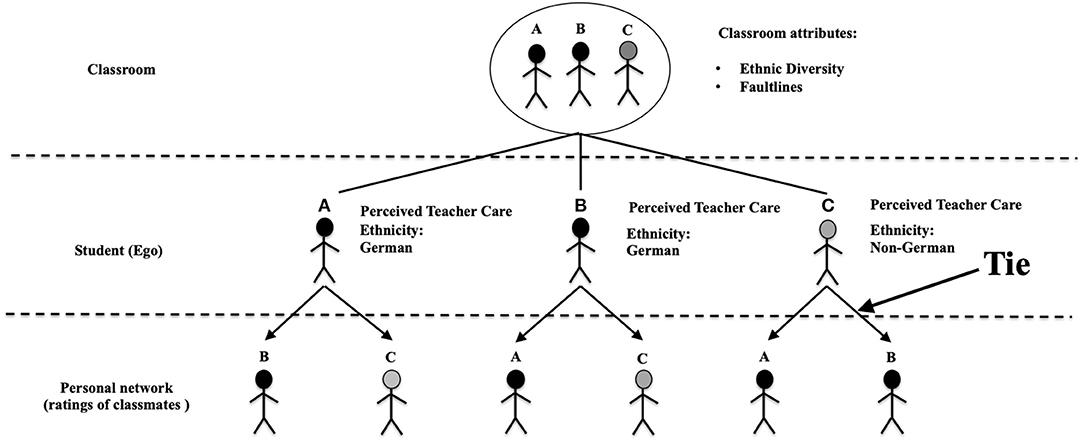

Peer ratings of students were analyzed within a dyadic social network approach, whereby we studied each students' personal network. In these analyses, the focus of interest lies on the valued tie (i.e., the rating of the relationship) between the ego (i.e., the student who is rating their classmates) and the alters (i.e., the classmates who are rated) (see Figure 1). As each child rated each of his or her classmates, the ratings of the students were not independent on each other. Therefore, and in line with previous work (e.g., Snijders and Bosker, 1999; Vermunt and Kalmijn, 2006; de Miguel Luken and Tranmer, 2010), we analyzed personal networks within a multilevel framework. This procedure allows to disentangle ego effects, alter effects, and the relative characteristics of ego and alter (i.e., whether ego and alter have the same ethnicity) (de Miguel Luken and Tranmer, 2010). Specifically, we were interested in whether students' average ratings of their classmates depended on their and their classmates' ethnicity. Moreover, we analyzed whether these peer ratings depended on classroom faultlines and perceived teacher care. Therefore, the data spanned three levels: the peer ratings that a child gave, the child who gave the ratings (i.e., the ego) and the classroom of the child (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study design: Personal network of ego with the ties between ego and their classmates as dependent variable. A tie reflects a rating of a student for a classmate of how much the child would like to sit next to them (1 = not at all, 4 = very much so). Ties are analyzed with regard to the ethnicity of ego and their classmates (German vs. non-German background) and characteristics of the classroom (i.e., ethnic diversity, faultlines, and teacher care).

We followed the modeling approach suggested by de Miguel Luken and Tranmer (2010), whereby we initially tested if there were significant differences between the ratings of the individual children and the average ratings in the classrooms. A model with random intercepts at the individual and the classroom level fit the data best ( = 25.17, p < 0.001). Differences between classrooms explained five percent of the total variance in peer ratings while differences between children explained 52% of the total variance. In a next step, we added the characteristics of the ego (i.e., sex and ethnicity of the child who is giving the rating), the alter (i.e., sex and ethnicity of the child who is being rated), and the respective dyadic match (i.e., do ego and alter have the same sex? Do ego and alter have the same ethnicity?). Next, we entered the contextual variables (diversity, faultlines, and perceived teacher care) followed by their interactions with the dyadic match terms, whereby we first entered the 2-way interactions followed by the hypothesized 3-way interaction (see Figure 1). As we were interested in how individual perceptions of students' relationships with their class teacher shape their dyadic social networks, perceived teacher care was included at the level of the individual.

As the dependent variable of this study was a single item (i.e., “How much would you like to sit next to this student?”), the preconditions of normally distributed error terms for multilevel models were not met (Gelman and Hill, 2006). To consider the scale of the dependent variable, we used ordinal multilevel models and tested our analysis with cumulative link models of the ordinal package (Christensen, 2018a) in R (R Development Core Team, 2019). Cumulative link models assume that the response variable is ordinal and that any observation Yi falls within a category j = 1 to J categories (Christensen, 2018b). For our analysis, the model estimated the probability of how likely an observation falls into a category that is smaller than or equal to the values from 1 to 4 as a function of the predictors. Based on the combination of predictors, the respective combination of estimated effects can be expressed as a latent variable. Higher values of this latent variable reflect a smaller probability that a category falls within a category that is equal to or smaller than j. In other words, higher values represent higher probabilities that children positively evaluated their peers. More information on cumulative link models can be found in the Supplementary File (see S0).

In a first step, we examined whether peer ratings depended on ethnicity and gender. Table 1 (step 1) shows the model that contains characteristics of the ego, characteristics of the alter and the dyadic information about gender and ethnic match. The results showed that, on average, German students had a higher probability of receiving more favorable ratings as compared to students with non-German background. Additionally, girls were less likely than boys to receive favorable peer ratings. Moreover, the results (see Table 1, step 1) point to ethnic and gender homophily. Fourth graders with the same ethnicity and with the same gender preferred to sit next to each other. Thus, in line with prior findings (e.g., Veenstra and Dijkstra, 2011), dyadic gender match was included as a control variable in our model3. In a next step, we added gender diversity, ethnic diversity, faultlines, and perceived teacher care to the model.

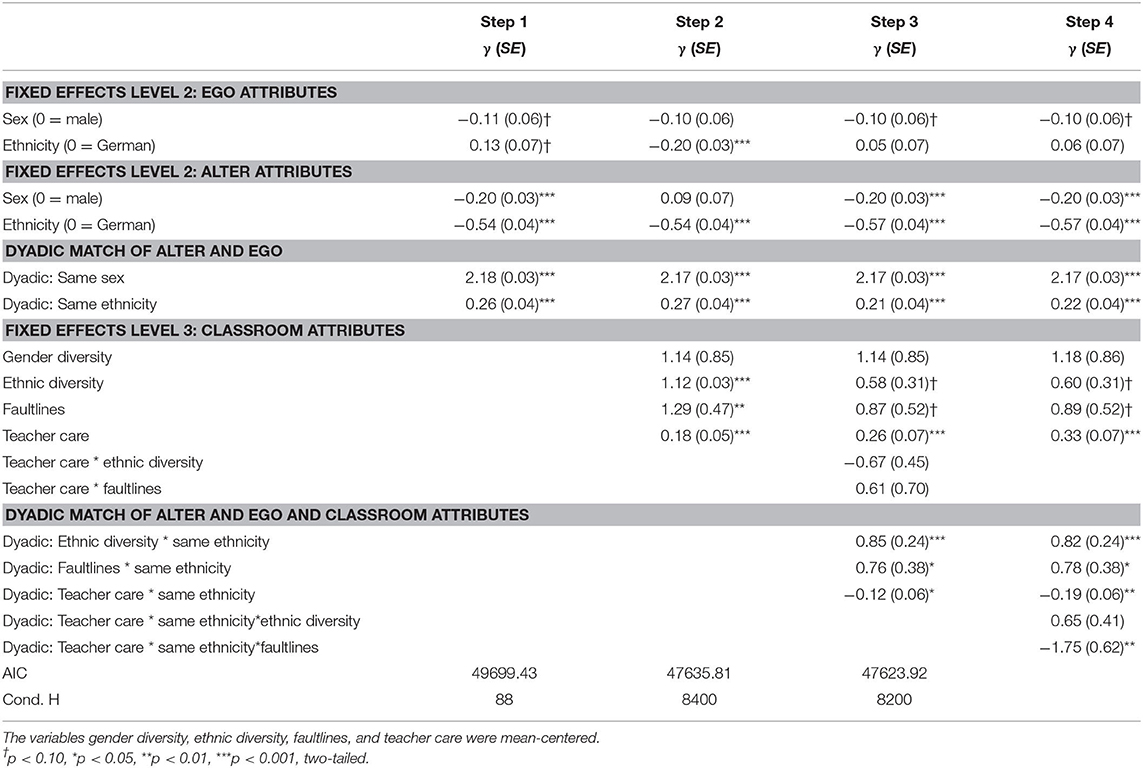

Table 1. Results of the multilevel cumulative link models predicting students' inclusion preferences (N = 23,727 peer ratings by 1,299 early adolescents in 70 classrooms).

When analyzing faultlines, it is recommended by Lau and Murnighan (2005) to control for the diversity attributes included in the faultline measure. Thus, we included ethnic diversity and the interaction of ethnic diversity and ethnic dyadic match in all analyses. When looking at ethnic diversity, it is interesting to note that higher levels of ethnic diversity in classrooms were positively associated with a higher probability to rate classmates positively—when the dyadic composition was not taken into account. However, the results showed that same ethnic dyads had a higher probability to prefer each other in classrooms with higher ethnic diversity as compared to classrooms with lower ethnic diversity. Post-hoc tests4 revealed that this difference was significant, z = 5.12, p < 0.001. Moreover, in classrooms with higher ethnic diversity, peer ratings were significantly higher for same ethnic dyads than for interethnic dyads, z = 16.74, p < 0.001. These interaction patterns are displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Students' ratings of their classmates (“How much would you like to sit next to X?”) for interethnic and same-ethnic dyads and classrooms with weak vs. strong ethnic diversity. The latent variable represents the probability for choosing higher categories.

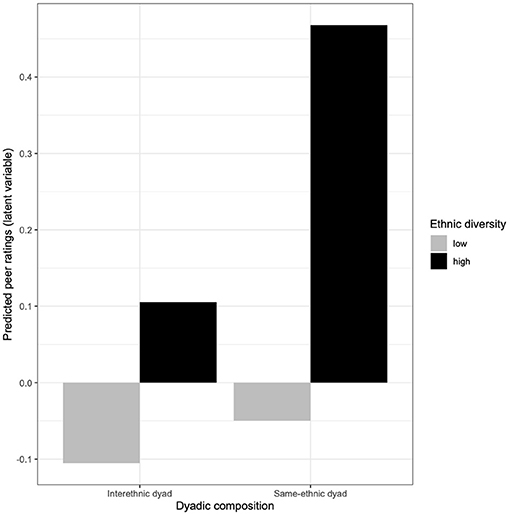

To test our first hypothesis that faultlines are related to increasing ethnic homophily (Hypothesis 1), we added the interaction of faultlines x dyadic ethnic match to the previous model. The significant interaction (see Table 1, step 3) is shown in Figure 3A. Same-ethnic dyads had a higher probability to prefer each other in classrooms with strong faultlines—as compared to classrooms with weak faultlines. Post-hoc tests revealed that this difference was significant, z = 3.28 p = 0.006.

Figure 3. (A) Students' ratings of their classmates (“How much would you like to sit next to X?”) for interethnic and same-ethnic dyads and classrooms with weak vs. strong faultlines. The latent variable represents the probability for choosing higher categories. (B) Students' ratings of their classmates (“How much would you like to sit next to X?”) for interethnic and same-ethnic dyads and classrooms with low vs. high teacher care. The latent variable represents the probability for choosing higher categories.

In line with Hypothesis 2a, perceived teacher care was positively related to students' peer ratings (see Table 1, step 2). Moreover, as assumed in hypothesis 2b, perceived teacher care moderated the relation between faultline strength and ethnic homophily (see Table 1, step 3). Figure 3B demonstrates that there was a stronger homophily effect when students perceived their teacher as low caring. Post-hoc tests showed that students rated same-ethnic classmates significantly more positively compared to classmates with a different ethnicity, z = 15.50, p < 0.001, when teacher care was low. However, even when teacher care was high, students showed a significant preference for same-ethnic classmates as compared to interethnic dyads, z = 13.32, p < 0.001. Importantly, in this condition, peer ratings were on average more positive rather than when teachers were perceived as low caring. In addition, when looking at peer ratings that classmates received in mixed dyads, there was a significant difference between low and high teacher care, such as peer ratings for interethnic dyads were significantly more positive when teacher care was high, z = 3.88, p < 0.001. Taken together, Hypothesis 2b was partially supported, as on one hand the results still showed a pattern of ethnic homophily even if teacher care was high, but on the other hand, ethnically mixed dyads were more positively evaluated when students perceived their teacher as caring.

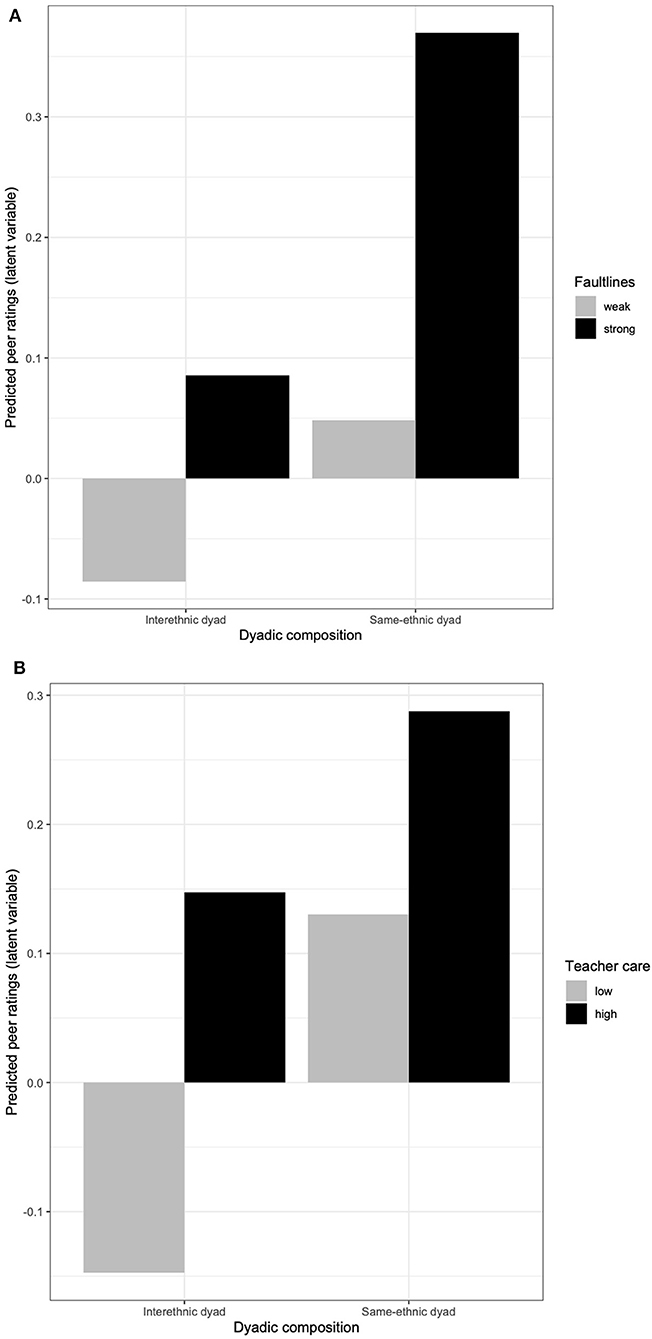

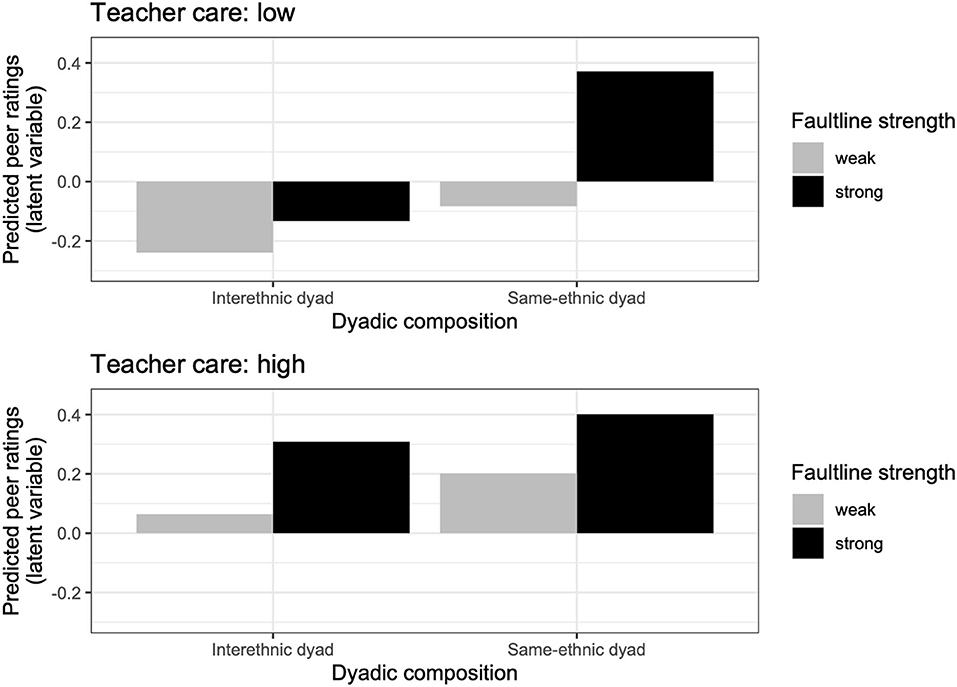

Finally, in order to test whether teacher care moderated the relation between ethnic homophily and faultlines (Hypothesis 3), we included the interaction term dyadic ethnic match x faultlines x teacher care to the previous model (see Table 1, step 4). The results showed a significant three-way interaction, revealing that teacher care and faultlines mattered for how students in same and mixed-ethnic dyads evaluated each other. Figure 4 displays that in classrooms with strong faultlines and high teacher care, students still rated same-ethnic dyads as more positive as compared to interethnic dyads, z = 9.23, p < 0.001. However, the homophily effect in classrooms with strong faultlines was smaller compared to when teacher care was low, where the effect was, z = 14.23, p < 0.001. Moreover, students showed more in-group bias in classrooms with strong faultlines as compared to classrooms with weak faultlines when teacher care was low, z = 3.64, p = 0.007, while this was not the case when teacher care was high, z = 1.64, p = 0.726. Importantly, in classrooms with strong faultlines, early adolescents showed a higher preference for interethnic dyads if teacher care was high compared to when teacher care was low, z = 3.93, p = 0.002. In contrast, in classrooms with weak faultlines, there were no significant differences regarding pupils' preference for interethnic dyads for students who perceived high vs. low teacher care, z = 2.62, p = 0.148 (see Figure 4). Taken together, these findings provide support for Hypothesis 3, that high teacher care plays a protective role for negative effects of faultlines, although it cannot dissolve in-group bias.

Figure 4. Students' ratings of their classmates (“How much would you like to sit next to X?”) for interethnic and same-ethnic dyads, depending on faultline strength, and teacher care. The latent variable represents the probability for choosing higher categories.

We were particularly interested to find out whether ethnic majority group students expressed higher in-group bias than ethnic minority group students. Therefore, we conducted separate exploratory analyses including the dyadic match by ego interaction terms to the model (e.g., do German pupils rate classmates with a German background more positively relative to interethnic dyads? And similarly, do students with a non-German background rate non-German classmates more positively relative to interethnic dyads?). For these analyses, we created a factorial variable that expressed if both students were either of German or non-German background, or if the dyads were ethnically mixed.

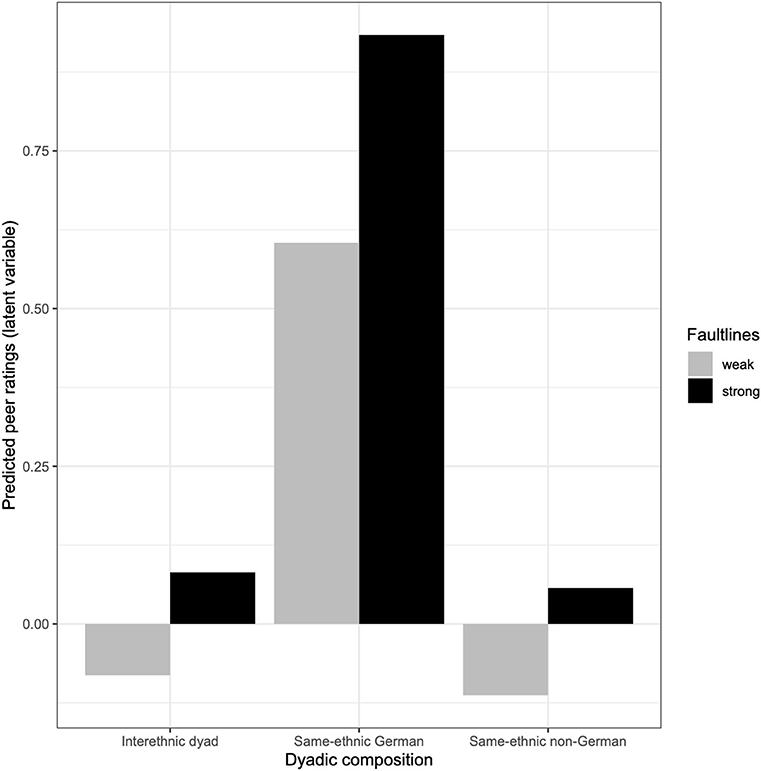

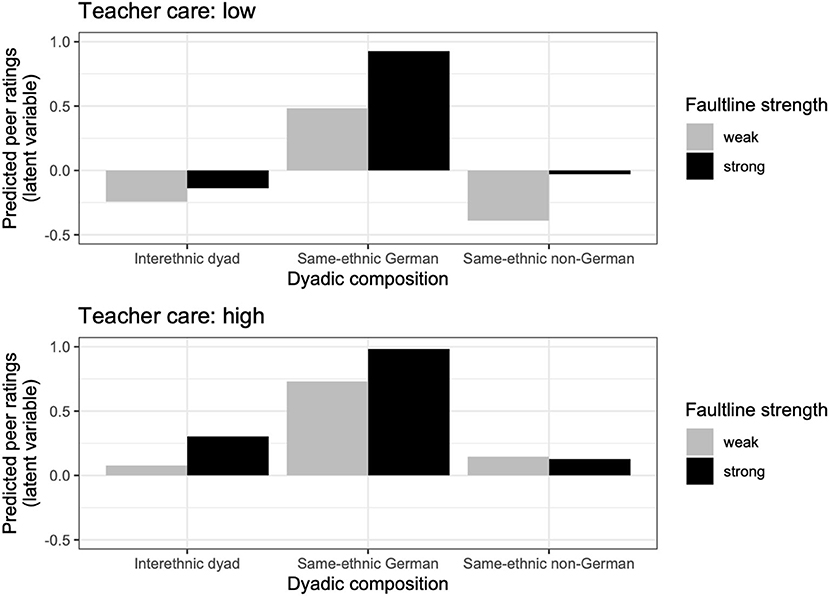

The results (for details, see the Supplementary File 2) indicated that students with a German background expressed more in-group bias than students with a non-German background (nGb): While German students favored German students over interethnic dyads, nGb students rated nGb students less positively relative to interethnic dyads. Furthermore, the preference for ethnic homophily among students with a German background was stronger in classrooms with stronger faultline strength as compared to classrooms with weak faultlines, z = 3.10 p = 0.024 (see Figure 5). Even when perceiving high teacher care, German students still expressed in-group bias, z = 12.22, p < 0.001. However, this difference was smaller compared to when teacher care was low, z = 14.97, p < 0.001. In addition, further supporting Hypothesis 2b, students in interethnic dyads showed more positive peer ratings when teacher care was high as compared to when teacher care was low, z = 4.02, p < 0.001 (see Supplementary Figure 3). Lastly, the post-hoc contrasts revealed a trend that German students showed more in-group bias (i.e., relative to interethnic dyads) in classrooms with strong faultlines as compared to classrooms with weak faultlines when teacher care was low, z = 3.20, p = 0.060. However, this result did not reach statistical significance and requires replication in future studies. Lastly, when teacher care was high, students with a German background did not express more in-group bias in classrooms with strong faultlines, z = 1.89, p = 0.764. Importantly, in classrooms with strong faultlines, ethnically mixed dyads were rated significantly more positively when teacher care was high as compared to when it was low, z = 3.91, p = 0.005 (see Figure 6). These findings therefore provide additional support for Hypothesis 3.

Figure 5. Students' ratings of their classmates (“How much would you like to sit next to X?”) for interethnic, non-German—non-German background, and German—German background dyads and classrooms with weak vs. strong faultlines. The latent variable represents the probability for choosing higher categories.

Figure 6. Students' ratings of their classmates (“How much would you like to sit next to X?”) for interethnic, non-German—non-German background, and German—German background dyads, depending on faultline strength and teacher care. The latent variable represents the probability for choosing higher categories.

Taken together, the more detailed explorative analyses further show that in-group bias was driven by German students and intensified by strong faultlines. In these classrooms, perceived teacher care had a protective effect, particularly since mixed ethnic dyads were rated more positively.

By combining ego-networks with a multilevel model for a fine-grained analysis of effects of classroom composition and teacher care, the current study allowed for new insights about driving forces involved in ethnic homophily. The current work demonstrates that contact opportunities in ethnically diverse classrooms do not necessarily go along with a higher desire for contact. This finding resonates well with previous work that found strong effects of ethnic homophily (e.g., Strohmeier, 2012; Bagci et al., 2014; Graham et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2014). The novel findings of the study point to the important role teachers play in shaping social relationships among ethnically diverse students: Fourth graders who perceived their teacher as supportive and caring were more positive toward mixed ethnic dyads and this was particularly the case in classrooms with stronger faultlines (i.e., stronger overlap of ethnicity and gender), where ethnic homophily was most salient. We build our discussion of potential explanations for this central finding on the analysis of how ethnic minority and majority group students rated their peers, as one of the novel aspects of this research was the joint investigation of students from ethnic minority and majority groups within dyadic social networks. Therefore, we discuss differential findings depending on social status with regards to diversity and faultlines in particular. Investigating faultline in the context of ethnically diverse classrooms, we were able to demonstrate how the intersectionality of different diversity attributes may negatively affect intergroup interactions in the school context.

How ethnicity is evaluated is expressed and shaped through early adolescents' interactions with peers (Verkuyten, 2016; Leszczensky et al., 2019). During the transition to early adolescence, the meaning of ethnicity is explored, rendering ethnic identity salient (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). Hence, increasing ethnic homophily in friendship selection represents students' increased need for a shared social identity (Wilson and Rodkin, 2011; Strohmeier, 2012; Bagci et al., 2014; Graham, 2018). These affiliation processes may be different, depending on early adolescents' social status. In the current study, adolescents from the German majority group showed a stronger preference for ethnic homophily as compared to mixed ethnic dyads than the non-German minority group. Many previous studies have shown that ethnic majority group children are more likely to rate their ethnic in-group peers more positively than ethnic out-groups (e.g., Strohmeier et al., 2006; Vervoort et al., 2011), and have a stronger tendency to affiliate with same-ethnic peers than with peers from different ethnicities (Hamm et al., 2005).

In particular, ethnic majority groups were less open to cross-ethnic boundaries. In contrast, students with non-German background rated interethnic dyads with German students more positively compared other non-German classmates. Thus, German students received higher ratings overall, representing ethnic-hierarchy in the classroom. Ethnic hierarchy means that ethnic groups with a high social status in society hold a high status in the classroom (Jackson et al., 2006; Schachner et al., 2015). Ethnic minority group students may be aware of such status differences and may want to affiliate with higher status groups, reflecting their higher positiveness toward majority group classmates (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Brown and Bigler, 2002). In line with this idea, prior studies found that ethnic minority children are more likely to report peers from ethnic majority groups as friends (e.g., Verkuyten and Martinovic, 2006; Vermeij et al., 2009; Schachner et al., 2015). Taken together, the results further strengthen previous evidence that the majority group seems to be the one to decide whether cross-group interactions and friendships occur (e.g., Schwarzenthal et al., 2017).

When considering the direct effect of ethnic diversity and faultlines, there seemed to be a positive effect on peer relations in the classroom. However, when looking at the dyadic intergroup level, these average positive effects were due to higher levels of ethnic homophily among German majority group members. Consequently, the present study highlights that effects of diversity should not neglect the dyadic level of intergroup interactions. With increasing ethnic diversity and stronger faultlines in particular, the power and higher status of ethnic majority group students may be perceived as compromised which could lead to a higher need for in-group affiliation. In order to keep the ability to control resources of the peer group, majority group students may become less open to cross-ethnic peers. Studies testing the ethnic competition theory have shown that increasing numbers of minority group students were associated with more negative peer relations and higher homophily among ethnic majority group students (Kawabata and Crick, 2008; Vervoort et al., 2011; Wilson and Rodkin, 2011; Durkin et al., 2012; Bagci et al., 2014).

The current study focused on gender-ethnicity faultlines, whereby both, ethnic and gender homophily revealed strong effects. When both categories align, demarcation of group boundaries may be more salient to students, rendering ethnicity more salient. Moreover, stronger group boundaries may predict higher levels of perceived threat among majority group students (Turner et al., 1987; Thijs and Verkuyten, 2014), which in turn negatively relates to peer interactions (Duffy and Nesdale, 2008). To date, faultlines have not been investigated in classroom settings; however, research in organizational contexts has shown that when teams are divided into subgroups on the basis of identity-related attributes such as gender and ethnicity, group tensions between subgroups increase (Li and Hambrick, 2005; Carton and Cummings, 2013). Therefore, the findings of the current study suggest that it is important to consider multiple aspects of diversity and their intersection when studying classroom social relations. In classrooms with strong faultlines, students of minority groups may have more limited opportunities to be accepted by peers. Limited evidence on the intersectionality of gender and ethnicity revealed that students from multiple minority groups may have a higher risk for exclusion because the pressure to conform to the characteristics of the “average student” increases (Vervoort et al., 2011; Ghavami and Peplau, 2012; Juvonen, 2017). Accordingly, the majority group students in the current study expressed more in-group bias in classrooms with stronger faultlines while minority group students' peer ratings depended less on faultlines. Regardless of faultline strength, these students preferred dyads with German students relative to other students with non-German background. This finding may reflect that minority group students cannot afford to avoid majority group students (Leszczensky et al., 2018). However, it is in contrast to previous work that found more bullying and fights of ethnic minority group students when their numbers increased (e.g., Jackson et al., 2006; Vervoort et al., 2011). It is possible that there would be different effects for different subgroups of the non-German ethnic minority group (e.g., when investigating different nationalities or subcultures); however, due to limited numbers associated with limited statistical power, we could not distinguish between specific minority groups, which is an important area for future research.

The central finding of this study was that negative associations between faultlines and students' peer relations were less pronounced when perceived teacher care was high. Moreover, when students perceived their teacher as high in care, there was no difference in the magnitude of in-group bias between classrooms with weaker and stronger faultlines. Instead, peer ratings were generally higher. In contrast, when teacher care was low, in-group bias was higher in classrooms with stronger than weaker faultlines. Hence, classroom composition did not matter as much for interethnic peer relations, when teachers were perceived as supportive and caring. This study therefore adds novel insights to the discussion of interethnic relations in ethnically diverse school classes that particularly highlight the competencies of teachers for students' inclusion (Thijs and Verkuyten, 2012; Geerlings et al., 2017; Juvonen et al., 2019).

When students perceived their teacher as highly caring and supportive, they were more open toward mixed-ethnic dyads (i.e., rated students of different ethnicity more favorably). This finding was significant above and beyond the effect that students were generally more positive toward their peers when perceiving high teacher care. By analyzing interethnic relations at the dyadic level, it was possible to disentangle these effects. Moreover, the analyses showed that ethnic homophily was still present, but weaker when teachers were perceived as high in care. This may be a consequence of the high significance of ethnic identity exploration and increasing attention to the intergroup peer world during early adolescence (Strohmeier, 2012; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). There are multiple explanations for the effects of teacher care, which can be explored in future longitudinal work.

First, it is possible that openness for cross-ethnic interactions (i.e., for choosing a seating partner from the ethnic minority or majority group) may be a result of emotional security provided in positive teacher-student relationships. Research in classrooms based on attachment theory shows that students who are securely attached to their teacher are more confident to master challenging situations and taking risks in peer interactions, as they trust their teacher would help and support if needed (Gest and Rodkin, 2011; Luckner and Pianta, 2011; Thijs and Fleischmann, 2015). There is some previous support with regards to intergroup situations, whereby students who perceived higher closeness to their teacher reported higher motivation for intercultural openness (i.e., to engage with cross-ethnic peers), which in turn predicted more positive out-group attitudes among ethnic majority group students (Geerlings et al., 2017). In addition, relationship security can reduce perceived out-group threat (Mikulincer and Shaver, 2001). Students who perceive their teacher as caring could have fewer negative expectations for cross-group interactions, rendering such interactions less threatening. In line with this idea, perceived teacher care was particularly relevant in classrooms with stronger faultlines, where group boundaries and threat may have been more salient. Thus, teachers may have an important role in facilitating perceived security of group relations, particularly when group boundaries are highly salient.

In addition to providing relational security, teachers can also shape peer ecologies through their interactions with students (McAuliffe et al., 2009; Audley-Piotrowski et al., 2015; Farmer et al., 2019). In caring teacher-student relationships, students feel respected, supported, and valued by the teacher (Doll et al., 2004). Therefore, it is plausible that students who perceived high care received positive messages from their teacher, which in turn serves as a reference for other students about the social value of that specific student (e.g., Mikami et al., 2010, 2012; Hughes and Chen, 2011; Hendrickx et al., 2016). With regards to interethnic relations, teachers have power to positively shape the perceptions of minority and majority group students by communicating their social value (i.e., through praise; Hughes et al., 2001) and by disconfirming negative stereotypes and repairing negative reputations of students (Mikami et al., 2010; Juvonen et al., 2019). Peers are highly sensitive to cues about whether to judge a peer as deviant and toward potential conflicts of specific students with their teacher (Mikami et al., 2010). From an intergroup perspective, such negative interactions with the teachers may add to intergroup conflict in classrooms by perpetuating negative stereotypes about out-group students (e.g., when a minority group student is often disciplined by the teacher and seen as disruptive; Bigler and Liben, 2007; Juvonen et al., 2019). In addition, negative interactions may increase attention to the group level, which in turn is associated with higher in-group bias (Brown and Bigler, 2002; Thijs and Verkuyten, 2012). In line with this reasoning, ethnic homophily was much higher when perceived teacher care was low.

Some authors have argued that interactions of majority group teachers with minority group students may serve as a form of extended intergroup contact (i.e., observing how an in-group member positively interacts with out-group members; Thijs, 2017). Positive intergroup contact may facilitate trust and other positive emotions, which can transfer from the teacher to other out-group members (i.e., out-group students). There is some support with regards to ethnic minority group students (Thijs and Verkuyten, 2012), whereby these students expressed more positive attitudes toward the majority group in relatively segregated classrooms, if they perceived more closeness to their majority group teacher. In contrast, in the current study minority group students' peer ratings were less affected by teacher care than those of majority group students. When teacher care was high, students with non-German background were equally positive toward mixed and non-German dyads; when minority group students perceived teacher care as low, they rated peers more negatively, independent of their ethnicity. The current study did not assess the ethnicity of class teachers and can therefore not investigate whether the effects of perceived teacher care could be due to extended contact. However, perceived teacher care was generally related to more positive peer relations and more positive ratings of mixed-ethnic dyads; therefore, teachers' ethnicity may be less relevant than their behavior.

The general positive effect of perceived teacher care may be explained by a general positive peer climate. Teacher-child relationships have been discussed as important antecedents of students' peer acceptance and prosocial behavior (e.g., Hughes et al., 2001; Mikami et al., 2012; Sette et al., 2019). In particular, the relationship quality of students with their teacher longitudinally predicts classroom social hierarchies (Cappella and Neal, 2012). If classrooms are characterized by hierarchies, it is more likely that certain students are excluded (Schäfer et al., 2005; Mikami et al., 2010; Hendrickx et al., 2016). In contrast, if teachers provide higher emotional support to students, students are more likely to form reciprocal friendships (Gest and Rodkin, 2011). Hence, accepting classroom climates facilitate positive peer relations, whereby students have positive role models for dealing with diversity (Hendrickx et al., 2016; Thijs, 2017; Farmer et al., 2019). By treating all students equally positive, teachers communicate value of diversity and promote classroom norms of equality and acceptance. Such norms in turn are related to higher acceptance and less discrimination of minority group students (Verkuyten and Thijs, 2002; Sanders and Downer, 2012; Benner and Graham, 2013; Schwarzenthal et al., 2017). Moreover, by establishing that everyone is treated equally, existing power imbalances among different ethnicities present in the classroom may be reduced (Schwarzenthal et al., 2017; Juvonen et al., 2019). Such effects are more apparent at the classroom level; whereby usually teachers' emotional support toward all students is observed. The current study focused specifically on individual perceptions of teacher-student relationships since the aim was to investigate how specific perceptions of students from minority and majority groups relate to their peer ratings. Still, individual perceptions of students are longitudinally predicted by observed emotional support (Gasser et al., 2018) and may therefore be higher when students perceive high teacher support. Given the importance of teachers for interethnic classroom dynamics, future research could determine differential effects of emotional support at the classroom level (i.e., observations), teachers' perceptions, and student perceptions on interethnic relations in the classroom. Moreover, how emotional teacher support relates to other practices that foster inclusion (e.g., multicultural education, inclusive school norms) is another important area for future research.

The study focused on students' ratings of each other as potential seating neighbors. Although such peer ratings are proxies for desired, sustained, and close contacts (seating neighbors in 4th grade spend a lot of time next to each other), the study cannot generate assumptions about cross-group friendships, prejudice or discrimination. Still, investigating social interactions is important, since a recent study showed similar patterns and effect sizes of ethnic homophily for social interactions and friendships (Fortuin et al., 2014). Ethnic homophily does not necessarily imply negative classroom relations; however, when students choose to affiliate only with same-ethnic peers, they withhold friendship opportunities and shared positive feelings from them (Juvonen et al., 2019). In order to better understand interethnic classroom dynamics, future longitudinal work could expand our cross-sectional findings and combine different aspects of dyadic peer relations with individual perceptions about classroom relations (e.g., perceived discrimination or school belonging).

Another limitation of this study was that we did not have enough power to answer our research questions with regards to contextual predictors of dyadic peer ratings for different groups of ethnic minority students. In particular, different subgroups of ethnic minority group students may have rated each other differently, leading to lower average in-group bias among minority group students. Ethnic identity may be particularly relevant for ethnic minority group students (e.g., Leszczensky et al., 2019).

Therefore, it is possible that minority group students distinguished themselves from other minority groups (Verkuyten and Thijs, 2010). Since this study cannot test assumptions about specific minority subgroups, future research could focus on a detailed analysis of ethnic identification and group dynamics for specific minority groups within different classroom contexts. This could provide additional insights into the role of teachers for specific minority groups, as previous evidence shows differential effects of teachers depending on the minority groups studied (Murray et al., 2008). Moreover, ethnic minority students may identify with different social groups (i.e., based on their national identity, migration background, the host country, or display dual-identity configurations; Leszczensky et al., 2019). Thus, future work could expand our findings that were based on nationality and shed more light on the different types of ethnic identification involved in peer processes, with a specific focus on teacher characteristics.

Finally, as we were interested in how students' peer ratings depended on their own and their classmates' ethnicity and on classroom features (i.e., diversity, teacher care), we chose to prioritize the possibility for analyzing valued ties in relation to classroom features over the possibility to study the complete social network. Thus, we were not able to control for structural effects of the complete social network. It may be possible that there could be structural network effects that limit or strengthen opportunities for contact among students (e.g., Vermeij et al., 2009). Thus, future work may focus on disentangling social network processes, individual characteristics, and classroom characteristics from a longitudinal perspective.

The findings of the current study provide new insights that teacher-student relationships may be key to foster inclusion among students in ethnically diverse classrooms—particularly in situations in which ethnicity and gender form strong faultlines. Although there was still ethnic homophily when students perceived their teacher as highly supportive and caring, they were more open to intergroup contacts, and particularly when group boundaries were salient. Hence our results support the assumption that teachers have a protective role for preventing negative interethnic relations, which implies strengthening the reflection of their influence on intergroup peer ecologies. This may have long-term consequences on students' social development, since cross-group relations serve as social capital (Juvonen et al., 2019), build intercultural competence (Schwarzenthal et al., 2017) and are important forces to combat prejudice and exclusion (Turner and Cameron, 2016). Openness to diversity may build the foundation for sustained positive peer-interactions, since the likelihood for choosing cross-ethnic friends increases if students have one cross-ethnic friend (Martinovic et al., 2011). Therefore, teachers have inherent power in creating positive intergroup relations and dealing with ethnic diversity.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin. The data collection procedure was in line with the APA guidelines and the guidelines of the German Association of Psychology.

JG participated in the study conceptualization, prepared the social network data, and performed the statistical analyses, their visualization and interpretation and drafted the manuscript and revised it based on feedback from co-authors. BM provided feedback for the study conceptualization, data analyses, interpretation, and visualization and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. MP provided feedback for the statistical analyses, data interpretation and visualization, and revised the methodological parts of the manuscript. SS provided feedback for the data analyses and intellectual content of the manuscript. RD acquisitioned the data, participated in the conceptualization of the study, and provided feedback for its intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This study has been founded by the Volkswagen Foundation, which aims to advance science and humanities (Grant No. AZ II/715 66).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors are grateful to Ulrich Wagner, Iris Jünger and Thomas Petzel for their support with the data collection. We also thank Bsc. Fabienne Lochmatter for the support in formatting and thoughtful reading of the manuscript and Dr. Ariana Garrote for her feedback. Lastly, our gratitude goes to the teachers and students who participated in the present study.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2020.586709/full#supplementary-material

1. ^Children also provided information about the country of birth of their parents. Out of the 1,269 children who reported this information (3% missing), 4% of the students (N = 51) had at minimum one parent born not in Germany (which is the official definition of a migration background), but were of German nationality.

2. ^Resettlers are ethnic German immigrants and represent one of the largest immigrant groups in Germany since 1990. They have lived in the former Soviet Union for many generations. Despite familiarity with German culture, former resettles face language barriers and are targets of prejudice and discrimination (Titzmann et al., 2015).

3. ^In order to control for the possibility that children with the same ethnicity and same gender would be more likely to prefer each other, we included this information in an alternative model. However, as this interaction was not significant, we did not control for same gender and same ethnicity homophily in the final model.

4. ^We conducted post-hoc tests with the lsmeans-package in R (Lenth and Hervé, 2015) and adjusted for multiple comparisons by using the Tukey method.

Agirdag, O., van Houtte, M., and van Avermaet, P. (2011). Ethnic school context and the national and sub-national identifications of pupils. Ethnic Racial Stud. 32, 357–378. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2010.510198

Audley-Piotrowski, S., Singer, A., and Patterson, M. (2015). The role of the teacher in children's peer relations: making the invisible hand intentional. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 1, 192–200. doi: 10.1037/tps0000038

Baerveldt, C., Van Duijn, M. A. J., Vermeij, L., and Van Hemert, D. A. (2004). Ethnic boundaries and personal choice. Assessing the influence of individual inclinations to choose intra-ethnic relationships on pupils' networks. Soc. Netw. 26, 55–74. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2004.01.003

Bagci, S. C., Kumashiro, M., Smith, P. K., Blumberg, H., and Rutland, A. (2014). Cross-ethnic friendships: are they really rare? Evidence from secondary schools around London. Int. J. Intercult. Relations 41, 125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2014.04.001

Barth, J. M., McDonald, K. L., Lochman, J. E., Boxmeyer, C., Powell, N., Dilon, C., et al. (2013). Racial composition on interracial peer relationships. Am. J. Orthopsychiatr. 83, 231–243. doi: 10.1111/ajop.12026

Baysu, G., Phalet, K., and Brown, R. (2014). Relative group size and minority school success: the role of intergroup friendship and discrimination experiences. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 53, 328–349. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12035

Bellmore, A., Nishina, A., You, J. I., and Ma, T. L. (2012). School context protective factors against peer ethnic discrimination across the high school years. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 49, 98–111. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9443-0

Benner, A. D., and Graham, S. (2013). The antecedents and consequences of racial/ethnic discrimination during adolescence: does the source of discrimination matter? Dev. Psychol. 49, 1602–1613. doi: 10.1037/a0030557

Bigler, R., and Liben, L. (2007). Developmental intergroup theory: explaining and reducing children's social stereotyping and prejudice. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 16, 162–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00496.x

Blau, P. M. (1977). A macrosociological theory of social structure. Am. J. Sociol. 83, 26–54. doi: 10.1086/226505

Brenick, A., Titzmann, P. F., Michel, A., and Silbereisen, R. K. (2012). Perceptions of discrimination by young diaspora migrants. Eur. Psychol. 17, 105–119. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000118

Brock, L. L., Nishida, T. K., Chiong, C., Grimm, K. J., and Rimm-Kaufman, S. E. (2008). Children's perceptions of the classroom environment and social and academic performance: a longitudinal analysis of the contribution of the Responsive Classroom approach. J. School Psychol. 46, 129–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2007.02.004

Brown, C. S., and Bigler, R. (2002). Effects of minority status in the classroom on children's intergroup attitudes. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 83, 77–110. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0965(02)00123-6

Cappella, E., and Neal, J. W. (2012). A classmate at your side: teacher practices, peer victimization, and network connections in urban schools. School Mental Health 4, 81–94. doi: 10.1007/s12310-012-9072-2

Carton, A. M., and Cummings, J. N. (2013). The impact of subgroup type and subgroup configurational properties on work team performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 95, 732–758. doi: 10.1037/a0033593

Christensen, R. H. B. (2018a). “Ordinal—Regression Models for Ordinal Data.” R package version 2018.8-25. Available online at: http://www.cran.r-project.org/package=ordinal/

Christensen, R. H. B. (2018b). Cumulative Link Models for Ordinal Regression with the R Package ordinal. R package vignette. Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ordinal

Civitillo, S., Schachner, M. K., Juang, L. P., Van de Vijver, F. J. R., Handrick, A., and Noack, P. (2016). Towards a better understanding of cultural diversity approaches at school: a multi-informant and mixed-methods study. Learn. Culture Soc. Interact. 12, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.lcsi.2016.09.002

de Miguel Luken, V., and Tranmer, M. (2010). Personal support networks of immigrants to Spain: a multilevel analysis. Soc. Netw. 32, 253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2010.03.002

Doll, B., Zucker, S., and Brehm, K. (2004). Resilient Classrooms: Creating Healthy Environments for Learning. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Duffy, A. L., and Nesdale, D. (2008). Peer groups, social identity, and children's bullying behaviour. Soc. Dev. 18, 121–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00484.x

Durkin, K., Hunter, S., Levin, K. A., Bergin, D., Heim, D., and Howe, C. (2012). Discriminatory peer aggression among children as a function of minority status and group proportion in school context. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 42, 243–251. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.870

Farmer, T. W., Hamm, J. V., Dawes, M., Barko-Alva, K., and Cross, J. R. (2019). Promoting inclusive communities in diverse classrooms: teacher attunement and social dynamics management. Educat. Psychol. 54, 286–305. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2019.1635020

Farmer, T. W., McAuliffe Lines, M., and Hamm, J. V. (2011). Revealing the invisible hand: the role of teachers in children's peer experiences. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 32, 247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2011.04.006

Fortuin, J., van Geel, M., Ziberna, A., and Vedder, P. (2014). Ethnic preferences in friendships and casual contacts between majority and minority children in the Netherlands. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 41, 57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2014.05.005

Gasser, L., Grütter, J., Buholzer, A., and Wettstein, A. (2018). Emotionally supportive classroom interactions and students' perceptions of their teachers as caring and just. Learn. Instruct. 54, 82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2017.08.003

Geerlings, J., Thijs, J., and Verkuyten, M. (2017). Student-teacher relationships and ethnic outgroup attitudes among majority students. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 52, 69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2017.07.002

Gelman, A., and Hill, J. (2006). Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. Cambridge: University Press.

Gest, S. D., and Rodkin, P. C. (2011). Teaching practices and elementary classroom peer ecologies. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 32, 288–296. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2011.02.004

Ghavami, N., and Peplau, L. A. (2012). An intersectional analysis of gender and ethnic stereotypes: testing three hypotheses. Psychol. Women Q. 37, 113–127. doi: 10.1177/0361684312464203

Graham, S. (2006). Peer victimization in school: exploring the ethnic context. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 15, 317–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00460.x

Graham, S. (2018). Race/ethnicity and social adjustment of adolescents: How (not if) school diversity matters. Educat. Psychol. 53, 64–77. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2018.1428805

Graham, S., Munniksma, A., and Juvonen, J. (2014). Psychosocial benefits of cross-ethnic friendships in urban middle schools. Child Dev. 85, 469–483. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12159

Grütter, J., and Tropp, L. R. (2018). How friendship is defined matters for predicting intergroup attitudes: Shared activities and mutual trust with cross-ethnic peers during late childhood and early adolescence. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 43, 128–135. doi: 10.1177/0165025418802471

Hamm, J. V., Bradford Brown, B., and Heck, D. J. (2005). Bridging the ethnic divide: Student and school characteristics in African American, Asian-Descent, Latino, and White adolescents' cross-ethnic friend nominations. J. Res. Adolescence 15, 21–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2005.00085.x

Hamre, B. K., and Pianta, R. C. (2005). Can instructional and emotional support in the first-grade classroom make a difference for children at risk of school failure? Child Dev. 76, 949–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00889.x

Hendrickx, M. M. H. G., Mainhard, M. T., Boor-Klip, H. J., Cillessen, A. H. M., and Brekelmans, M. (2016). Social dynamics in the classroom: teacher support and conflict and the peer ecology. Teach. Teacher Educat. 53, 30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2015.10.004

Homan, A. C., and van Knippenberg, D. (2015). “Faultlines in diverse teams,” in Current Issues in Work and Organizational Psychology. Towards Inclusive Organizations: Determinants of Successful Diversity Management at Work, eds S. Otten, K. van der Zee, and M. B. Brewer (Psychology Press), 132–150.

Hughes, D., Del Toro, J., Harding, J. F., Way, N., and Rarick, J. R. (2016). Trajectories of discrimination across adolescence: associations with academic, psychological, and behavioral outcomes. Child Dev. 87, 1337–1351. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12591

Hughes, J. N., Cavell, T. A., and Wilson, V. (2001). Further support for the developmental significance of the quality of the teacher-student relationship. J. School Psychol. 39, 289–301. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4405(01)00074-7

Hughes, J. N., and Chen, Q. (2011). Reciprocal effects of student-teacher and student-peer relatedness: effects on academic self efficacy. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 32, 278–287. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2010.03.005

Hughes, J. N., Im, M. H., and Wehrly, S. E. (2014). Effect of peer nominations of teacher-student support at individual and classroom levels on social and academic outcomes. J. School Psychol. 52, 309–322. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2013.12.004

Jackson, M. F., Barth, J., Powell, N., and Lochman, J. E. (2006). Classroom contextual effects of race on children's peer nominations. Child Dev. 77, 1325–1337. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00937.x

Jones, S., and Rutland, A. (2018). Attitudes toward immigrants among the youth: contact interventions to reduce prejudice in the school context. Eur. Psychol. 23, 83–92. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000310