- 1Educational Leadership Program, St. John Fisher College, Rochester, NY, United States

- 2Office of Global Learning, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, United States

Turbulent events in leadership and in life can challenge even those most stoic in the face of adversity and loss. Prefacing with a combined definition of resilience, this paper illustrates the complete lifecycle of resilience in the face of adversity and its resultant rewards when and if appropriately applied. Phases included in this lifecycle are: normalcy, deterioration, adaptation, recovery, and growth. The paper then discusses the application of the revised Leader Resilience Profile® (LRP) data, comparing leader resilience according to gender and age. Results from this ongoing study on resilience clearly show as people age, their resilience increases. The 60+ age group, in particular, had significantly higher resilience scores than participants in other age groups. Men between the ages of 20–29 had significantly higher resilience scores than women of the same age group. Other age groups provided no notable differences or substantial correlations when it came to gender and age. A framework is presented for how to become more resilient throughout the life course. This framework includes positive well-being, assessing and strengthening meaningful intrinsic and extrinsic resources, self-efficacy, future-focus, and important strategic avenues for resilient aging. The paper then raises the questions: who ages resiliently, and how, and what differences are there between young, old, retired, and elderly individuals when it comes to living and working resiliently? The paper concludes that support and proactivity are the means for achieving positive growth orientation, quality of life, self-identity, purpose, inhibiting stress-related debilitation, and resilient aging.

Resilient Educational Leaders in Turbulent Times: Applying the Leader Resilience Profile® to Assess Differences in Relationship to Gender and Age

People of all ages face adversity. How they adapt characterizes the resilience of any particular individual. Constituents, media, funding, peers, and shifting standards in education can disrupt the paths leaders pave in their professional careers, not to mention the personal, mental, and even physical impacts these carry when consistently under scrutiny. Surviving and thriving through these challenges is the essence of resilience, although resilience is more than merely enduring and surviving adversity. Rather, resilience is not only surviving but ultimately thriving in the face of adversity. Growth is engendered through challenges and experience along with the availing of supportive networks and resources. How leaders adjust to challenging situations in general, and in particular, how these adjustments correlate with the changes and challenges of physical and cognitive aging, is dependent on the characteristics of resilience discussed in this paper.

This paper contributes to the literature on resilience, offering salient findings on aging and resilience among educational leaders. The original dataset from LRP-R surveys on differences in resilience is reanalyzed to for correlation between gender and age. In particular, this paper furthers the conceptual understanding of resilience in the literature, as informed by the original findings of LRP-R on resiliency differences (Reed, 2018).

Commencing with a combined definition of resilience in leadership and aging, this paper highlights results from LRP-R data comparing leader resilience by gender and age, providing conceptual frameworks on resilience for younger and older leaders, prior to reaching retirement and elderly ages. The literature review on resilient aging elaborates on the patterns between age groups and their strategies for contented and resilient living over time. The paper presents a new framework: the Resilience Conceptual Framework for Aging and discusses primary and most notable differences between professional adults and the elderly, and how the implementation of resilience differs between these two groups. After describing a few limitations of the study, the paper concludes with insights for achieving resilience against aging. This study was undertaken to understand how older educational leaders employ resilience in the beginning stages of old age, and how these strategies may inform younger leaders, and others, in their professional and personal life trajectories.

Prior Research

Patterson et al. (2009) surveyed the experiences and developmental consequences of adversity in educational leadership to determine the characteristics and features of resilience in this population. In short, a resilient leader is one who is able to survive and then thrive in the wake of chronic adversity by reframing their losses into opportunities for adaptation and growth. In this context, the research shows that resilience is not malleable within short timeframes, but is rather an ongoing learning and developmental experience for the individual, enabling them to achieve and perform new skills with greater confidence while gradually preparing them for future hurdles. This reframing is shown to improve adaptability and overall outlook on life.

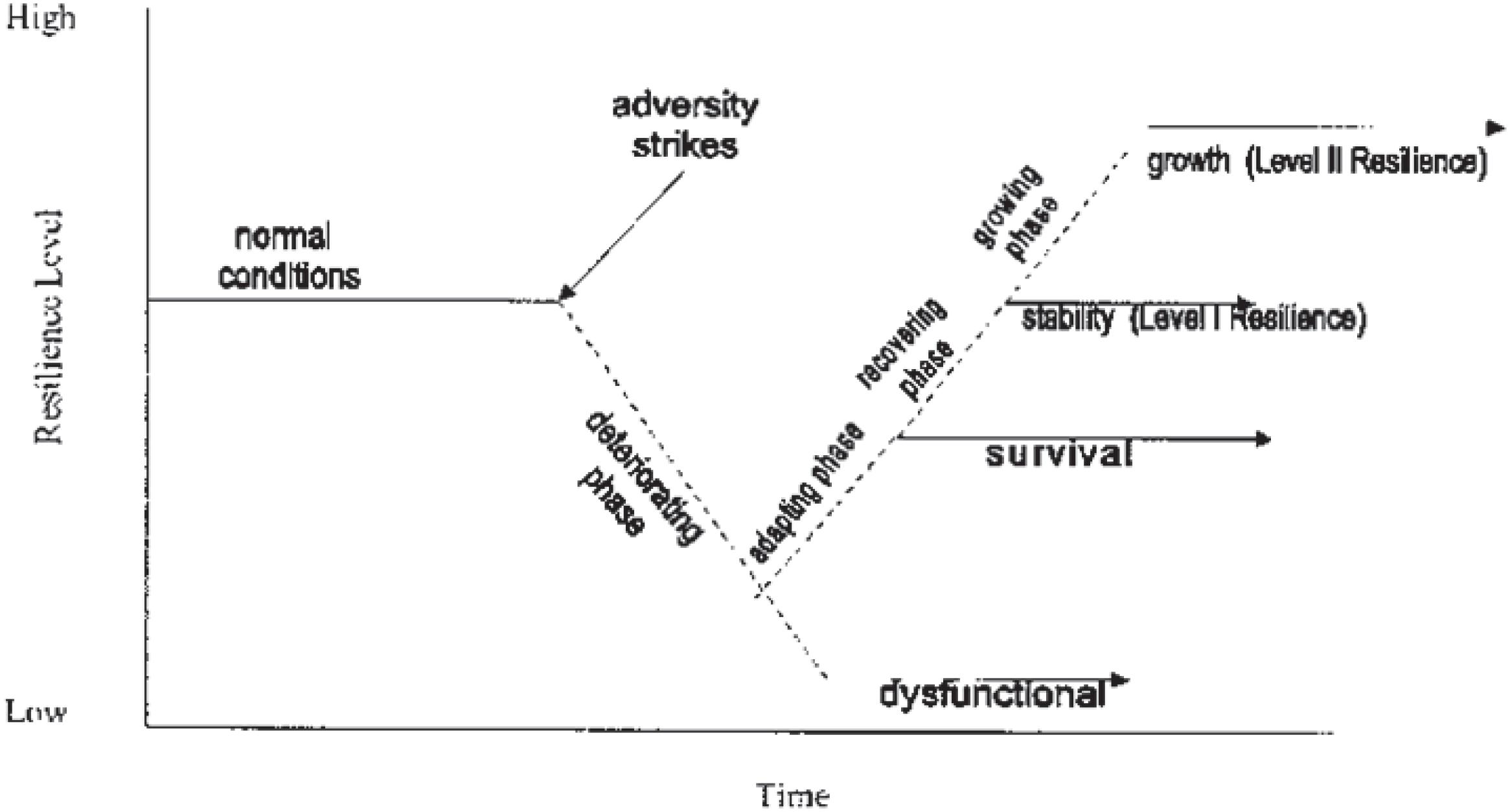

Patterson et al. (2009) research identifies five phases of the resilience cycle (Figure 1).

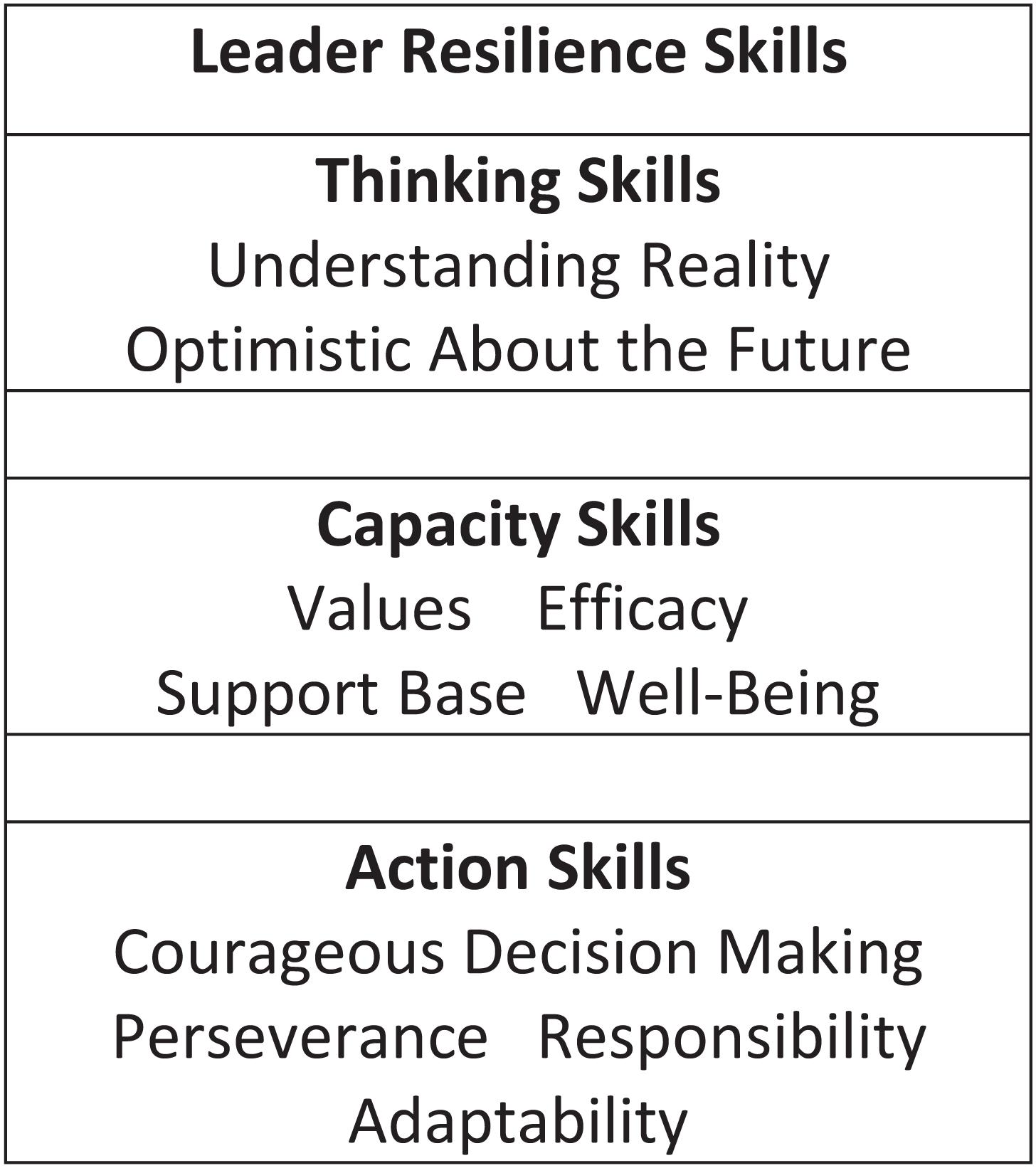

The cycle begins with Phase 1, considered “normal conditions,” where life is continuing along normally for the individual. Resources are plentiful, performance is high, and there is ample community support. Then adversity strikes. The individual abruptly falls into Phase 2, the deteriorating phase of the resilience cycle, where they think and act in ways that increases stress reactions, such as anger, aggression, and fear, and they may blame others. The emotions of denial, grief, and anger thrust them into a reactive position, wallowing wallow in “victim” status. A notable distinction between resilient and non-resilient people is the time spent in Phase 2. Resilient people tend not to languish in the role of victim. They quickly move to Phase 3, the adapting phase, which begins when they assume some responsibility for their situation and take action to avoid staying mired in the dysfunctional deteriorating phase of the resilience cycle. Continuing an upward trajectory, the adapting phase gives way to Phase 4, the recovering phase, following a path back to the level of stability experienced before the onset of adversity. The regaining of the status quo, in terms of stability and attitude, is referred to as Level 1 resilience. Concrete strategies, outlined below, may help them recover from adversity to this point. However, if they plateau at the status quo level, while they may continue to function adequately, they do not experience growth, and are rather merely coping with the stressor. Resilient individuals move beyond regaining a semblance of the status quo. They enter Phase 5, the growing phase, on their way to Level II resilience, in which they have not only rebalanced their situation, but have been strengthened. It is critical to note that individuals choose to move beyond Level 1 resilience, as it requires conscious effort. Below we outline three skill sets that successful leaders engage to achieve resilience (Figure 2). A resilient leader is one who demonstrates the capacity to recover and learn from, as well as grow stronger, in the face of adversity (Patterson et al., 2009).

In sum, Figure 1 demonstrates an individual’s means to achieving resilience in the face of adversity. At the point when normalcy is challenged, the individual is presented with a forked path with choices along with route: where the challenge is accepted or resisted, where one can settle or continue to grow. In choosing to resist the adversity through denial or flight, recovery and even growth are never achieved, leaving the individual in a state of developmental stasis. By choosing the path of accepting the challenge posed by adversity, recovery is gained first through adaptation, with the ultimate intent to not only survive but thrive beyond the comfortable plateau of stability, with the possibility of further developmental and personal growth that could not have been realized without the opportunity posed by the adversity in question.

Literature Review

Resilience is understood in many ways, though these understandings are undergirded with a shared notion of coping, adapting, and thriving in the face of adversity. Resilience is not the same as being stalwart but refers to the capacity to be tenacious, proactive, resourceful, and future-oriented. It is to desire to grow into a more adaptive and less reactive self, beyond the original status quo. As there is little literature on the relationship between leadership, resilience, and aging, which this study seeks to remedy, the review below discusses resilience in aging as a whole, particularly among senior citizens.

Resilience requires a greater understanding of one’s identity and therefore, to be resilient means maintaining and utilizing meaningful social connections. These connections play a pivotal role in establishing life-strengths. Adaptation is arguably critical for personal growth and success. In terms of aging, these factors are particularly salient, as a lifetime of experience has enabled the development of many social connections and support, which in turn, bolsters understanding of oneself in context with these relationships and their histories.

Resilience as Positive Thinking

Positive emotions have been shown to promote increased mental flexibility and lowered reactivity, improving and broadening coping skills and counteracting physiological effects of negative emotions (Reivich and Shatté, 2003). They focus on resilience as a matter of self-correction in the wake of adversity. In their view, resilience has to do with electing constructive and forward-thinking reactions in the face of adversity. Such thinking also demands a pathological remission of negative thoughts, meaning that the individual suppresses negative thinking in order to face and navigate adversity with mental and emotional “freeness and flexibility” that comes with positive thinking. In a similar vein, Lavretsky’s (2014) multidimensional study on resilience in aging focuses strongly on the health benefits (i.e., emotional, cognitive, and physical) of resilience to the elderly. Reactivity to loss can be managed by using strategies for self-preparedness, such as regular exposure to new situations, removing societal factors that burden quality of life, education from early age, updating obsolete, and positive, compensative thinking (Reivich and Shatté, 2003; Milstein, 2010; Fry and Keyes, 2013; Agronin, 2018).

Well-being, along with other resilience practices described in this review, is also measured by one’s spirituality or practice of religion as it provides a working avenue toward acceptance of change and reestablishing purpose in life. Spirituality, as a goal, resource, and strategy also fills emotional gaps that personal reflection may not in the wake of loss as it offers an avenue to faith and acceptance for unexpected losses. Regular practice of positive emotions in times of adversity strengthens resilience by reducing stress, a primary contributor to decrepitation and/or illness. Similarly, Lavretsky (2014) states that positive emotions (such as hope, laughter, social connectedness and gratitude) at a moment of loss or adversity, or “happiness intervention,” has been demonstrated to boost well-being, longevity, and quality of life. Lavretsky (2014) also poses the “broaden-to-build” theory, which hypothesizes that happiness intervention (particularly when coupled with openness to experience) expands an individual’s thought-action repertoires, building hardiness via growth through adversity and coping responses.

Resilience Through Struggle

Greitens (2016), through a personal narrative posed in a series of letters to a friend, provides several frames of resilience for PTSD sufferers in the military. He frames resilience in terms of freedom, death, and leadership, and focuses on achieving resilience through self-realization via rote exposure to struggle and a consistent, conscious practice of patience. In his view, resilience can only be cultivated through struggle. He also explains that learning to flow with the forces of adversity by evaluating one’s own perspective of self and others can manifest in resiliency, and that a greater and more complete sense of freedom and identity comes through persistence of action in hardship, not by procrastination or blame.

While Greitens’s (2016) contemplation on the nature of resilience is in the context of trauma and survival, Agronin’s (2018) review, from a psychiatric perspective, of aging among seniors illustrates that quality of life can be inferred and even measured by the health of relationships, self-esteem, sense of humor, gratitude, forgiveness, and, above all, conscientiousness. In this view, like those of Reivich and Shatté (2003) and Greitens (2016), resilience is cultivated through adversity. A consistent argument through the literature reviewed here is that adversity is a prerequisite for the cultivation of resilience. With proper engagement with a particular challenge, there are opportunities to gain insight and wisdom, which in turn yields personal growth, self-esteem, and sense of purpose, strengthening a sense of usefulness and meaning within the community. In Agronin’s frame of resilience in aging, resilience is the way of overcoming the “stagnant quo,” or sense of obsolescence as younger communities mature by reclaiming their sense of self in a dignified way and thriving in the wake of life course changes and accepting the difficulties that accompany them. In leaving one’s sense of purpose unpursued and resilience unpracticed, arguably aging will be that much harder on the individual.

Resilience Through Learning

Following the notion of pursuing one’s purpose and growth throughout the life course, Milstein’s (2010) argument regarding aging for retiring professionals is the value age brings when one becomes a student again. After a lifetime of experience, both personal and professional, mature adults may find it difficult to leave their sense of being the “expert” behind to become a learner again. Yet, by doing so, Milstein (2010) argues, the feeling of “oldness” will wane while the accumulation of new skills will help a senior to feel “like new.” To Milstein, this is the resilient response to aging. He advises that seniors learn new skills before dropping old ones so as to maintain one’s sense of self without worry about personal or intellectual loss following retirement. This view of adjusting to aging also incorporates a social emphasis, focusing on how the establishment of new boundaries, one’s connectedness to others, outlook, and life-renewing actions in the face of lifestyle changes can create a ripple effect, inspiring peers in similar stages of life to handle said changes with the dignity of self-defined autonomy. In this way, an individual takes charge of challenging situations as they move from one life stage to the next, incorporating self-authorization and personal leadership to their resilience skills.

One elderly woman offered a personal contribution to the literature as a woman in her nineties, including lessons on managing the losses that come with aging while resolving to be happy in old age (Allen and Starbuck, 2011). Her salient insights on resilience and aging, specifically coping with and adapting to permanent loss, brings a new scope to this study presented here. Resilient moments are itemized against specific losses, from hearing and vision to muscle degeneration and arthritis, acknowledging the necessity of adapting by maintaining a positive outlook, realizing limits (e.g., taking responsibility for personal safety and risks), meeting losses as challenges that keep the brain active, and minding reactions to limitations (e.g., patience, frustration), and adjusting accordingly.

Resilience Through Internal and External Resources

In Fry and Keyes (2013) examination of what it means to age successfully, they find that the healthy utilization of internal and external resources, self-efficacy, social connectedness, spirituality, and cognitive strength directly impact overall health. Growth orientation (self-identity through experience and reflection of desires) and growth motivation (preparedness inspired by anxiety over potential loss or adversity) also impact overall well-being, though they cannot be realized without meaningful intrinsic and extrinsic resources. Decline cannot be halted, Fry and Keyes argue, but it can be mitigated by positive emotions, positive relationships, and proactivity. Regular implementation of dynamic cognitive challenges, reflection on previous experience and new purposes in life (that is, “personal restructuring”), and weeding out relationships that lack positive meaning are strategies for enhancing not only resilience in old age, but also one’s self-identity, which in turn provides a working avenue toward contented living in the face of loss.

Milstein (2010), Fry and Keyes (2013), and Greitens (2016), support the idea that reflection and action on less prominent resources for resilience leads to a more contented, supported, confident, prepared, and whole self. By integrating the Resilience Conceptual Framework for Aging, the Leader Resilience Skills, and the Resilience Cycle, it is possible to strategize on what might be done to reclaim these missing links and better prepare for adversity, challenges, and potential future loss. Cognitive loss, as described by Fry and Keyes (2013), for example, can be inhibited by routine, dynamic exercises. Openness to experiences that challenge one’s self diversifies problem-solving, decision making, coping, and self-acceptance skills.

Resilience and Happiness

While not measured in our instrument, the literature review demonstrates that it is imperative to include in the findings of this study on resilience and aging that the key to successful aging is happiness, as happiness indicates the ability to maintain positive relationships and adaptability to challenges makes a more resilient self (Lavretsky, 2014). One must consider the state of their well-being and make improvements where necessary in the present and in preparation for the future (Patterson et al., 2009; Greitens, 2016). This may require the elimination of connections that lack positive purpose, reconnecting or strengthening relationships that have lasting meaning, strengthening cognizance, financial security, or spiritual understanding (Fry and Keyes, 2013). The realization of what is missing cognitively (Fry and Keyes, 2013) is the route to a more resilient self as one struggles to not just survive but thrive in the wake of adversity (Patterson et al., 2009). Indeed, this analysis corroborates the arguments that internal and external resources (Fry and Keyes, 2013), spiritual awareness (Lavretsky, 2014), autonomy (Milstein, 2010), self-efficacy (Fry and Keyes, 2013), personal growth (Patterson et al., 2009), and self-acceptance (Allen and Starbuck, 2011; Greitens, 2016; Agronin, 2018), are the pillars of resilience, and self-identity.

Resilience and Proactivity

Whether one is resilient, however, is largely dependent on one’s proactivity (Fry and Keyes, 2013). To be proactive is to be future-focused and claim control confidently, even if some degree of loss is anticipated (Fry and Keyes, 2009). In older individuals, psychological and cognitive impediments are viewed as challenges to be overcome (Lavretsky, 2014). This is accomplished by finding ways to compensate or adapt to loss or adversity by finding new routes to the same pleasures, such as listening to audiobooks when eyes no longer see Allen and Starbuck (2011). In the wake of loss, individuals look for ways to reclaim continuity through adaptive thinking, reflection, meaningful connection, and purpose in life (Reivich and Shatté, 2003; Milstein, 2010; Allen and Starbuck, 2011; Fry and Keyes, 2013). These actions highlight the benefits of proactivity over reactivity, as proactivity means not only personal control of a situation but mental and physical readiness for new situations (Lavretsky, 2014).

Summary

This study’s literature review therefore highlights that to strategize, therefore, is to defend and expand one or multiple abilities as, indeed, many areas of growth overlap, ultimately making their eventual loss with age easier to endure. The literature review also highlights that resilience can then build upon itself as years pass, strengthened by the utilization of internal and external resources such as perseverance, support, and self-realization, which provide not only growth from loss, but also reduces one’s need for intrinsic and extrinsic “replenishment,” either socially, emotionally, economically and so on. This then allows a greater sense of autonomy over one’s life, and confidence in one’s choices for their future, encouraging a positive outlook on challenges to come, as well as one’s skills as a leader in education as well as in life (Reivich and Shatté, 2003).

Study Purpose

Further analysis of the findings Reed (2018) study on educational leaders, resilience, gender, and age has led to the proposal of a new conceptual framework on aging and resilience.

Participants

Data collected for the original study were provided through the senior author’s consulting work, and participating respondents of the Leader Resilience Profile® (LRP-R) website: http://theresilientleader.com/quiz/index.php (Reed, 2018). This is a link to a survey where people self-select to complete the LRP-R and as such, is a self-reporting inventory. As stated before, this was self-selection. It is not a sample of any true population and the demographics were not monitored carefully enough to make any generalizations about the representativeness. Gender and age were reported but no other demographics were asked for.

Subjects were drawn from the governing boards of the American Association of School Administrators, Learning Forward, and the National Association of Elementary Principals, with the survey administered to 277 school administrators under the age of 70. The study received IRB approval from St. John Fisher University, and informed consent was granted from participants and their anonymity guaranteed.

Instrument

The original LRP contained 73 items. Over 1,000 respondents completed the LRP from 2009 to 2012. In 2012, the LRP was revised with a shortened data instrument and improved psychometric properties. The revised instrument (LRP-R) (Appendix), consists of 11 4-item subscales measuring the resilience dimensions described and has been validated in prior research (Reed and Blaine, 2015). Reed (2018) presents further findings and analysis for the Leader Resilience Profile®, which was derived from an original study (Patterson et al., 2009), to assess resiliency in relationship to gender and age.

For this study, we selected items for the LRP-R from the original database of findings. Two items from each subscale was selected with the lowest factor loadings dropped. We created 12 4-item subscales, increasing the current LRP-R to 44 items. Separated by 8 weeks, two tests were performed with subjects. For validity, we used the Brief Resilience Scale and Ego Resilience Scale.

Analysis

Overall resilience scores were calculated by averaging the 11 subscale scores for each participant. Overall scores ranged from 5 (lowest resilience) to 20 (highest resilience). The overall scale demonstrated adequate internal consistency in this sample (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.74). LRP-R subscale scores were not utilized for the purpose of this study. A 1-way ANOVA of resilience scores by age was conducted to determine the correlation between resilience and age. A Wilcoxon rank-sum tests was used to test the difference between male and female median resilience in each age group, with Bonferroni method employed to correct p-values for the set of tests.

Results

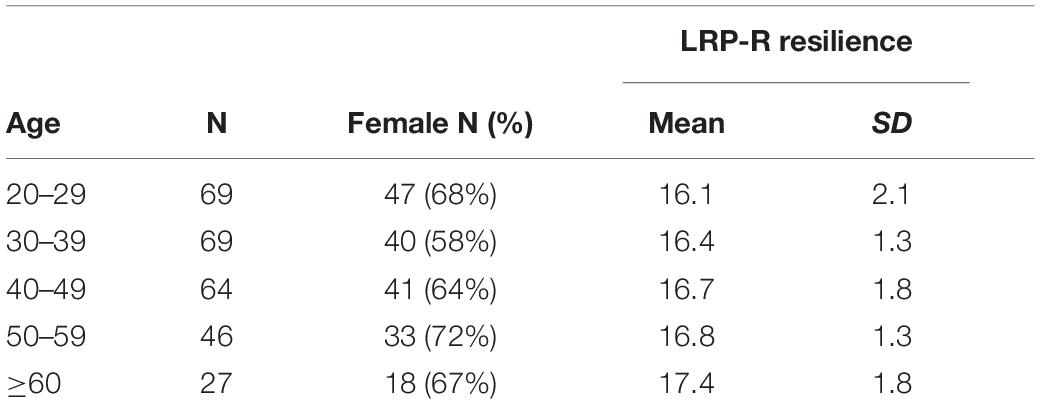

As cited in Reed (2018), LRP-R responses from 277 participants (female: n = 181, 65%; male: n = 96, 35%) were analyzed for gender differences in resilience and in the relationships between gender, resilience, and age. Female (M = 16.4, SD = 1.7) and male (M = 16.9, SD = 1.8) participants did not significantly differ in overall resilience, with one exception, described below. The 1-way ANOVA found that resilience increases reliably with age, although the magnitude of the relationship is small, F(4, 270) = 3.11, p = 0.016, eta squared = 0.04. The descriptive statistics appear in Table 1.

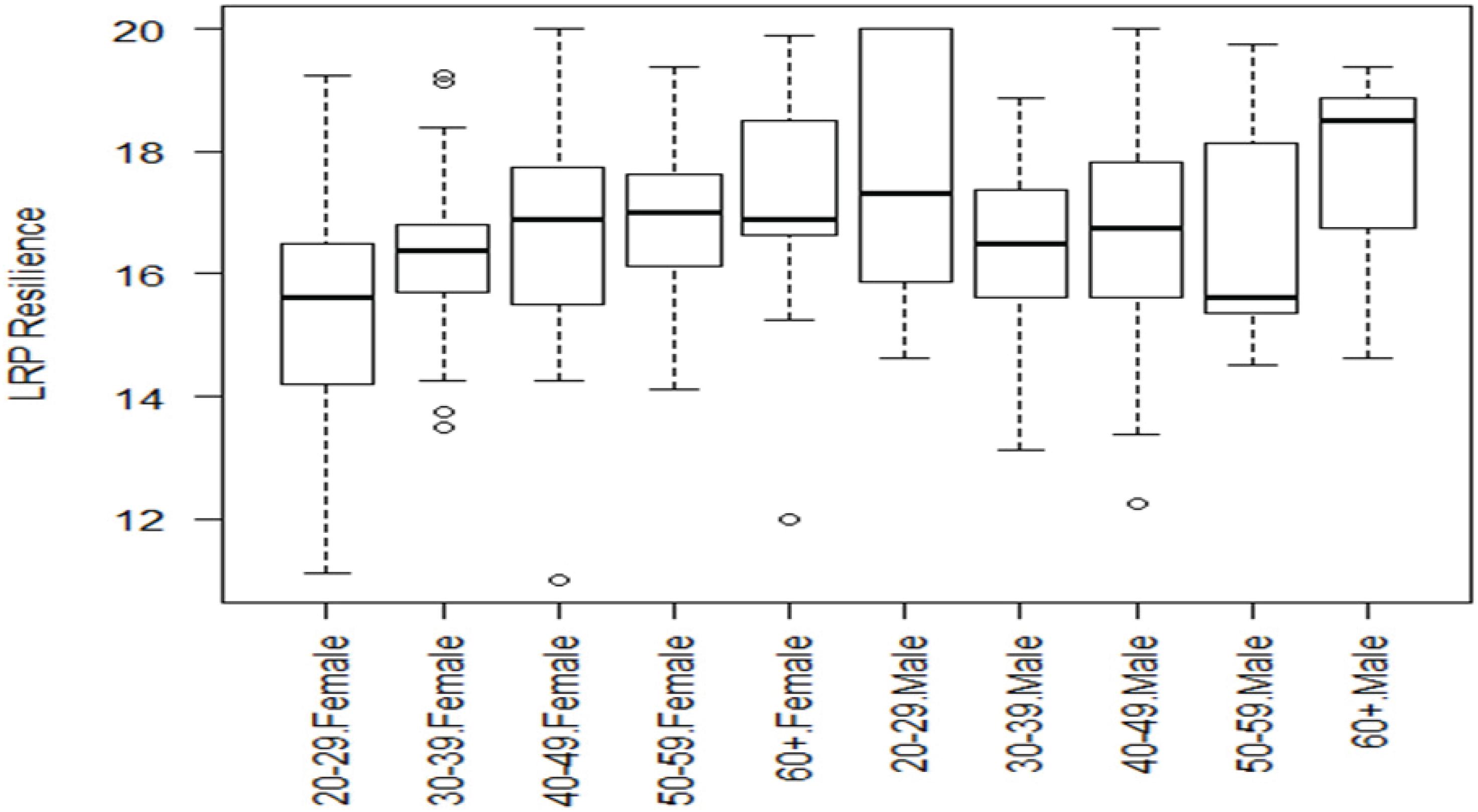

A planned contrast showed that participants in the 60 + age group, compared with all other age groups combined, demonstrated significantly higher resilience scores, F(1, 270) = 6.82, p = 0.009. Further analysis parsed the influence of gender in this relationship, with the boxplots in Figure 3 presenting resilience scores separately by age group and gender. Figure 3 demonstrates an increasing trend of resilience among females compared to males, suggesting that there is a difference between genders in the relationship between age and resilience. Further analysis of this finding, using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests to test the difference between male and female median resilience in each age group and correcting the p-values by the Bonferroni method for the set of tests show that in the 20–29 age group, men (n = 22, median = 17.3) demonstrate significantly higher resilience than women (n = 47, median = 15.6), Wilcoxon W = 215.5, p = 0.0001. There are no reliable gender differences in resilience in the other age groups (Reed, 2018). In summary, the results of this study show that the participants did not significantly differ in overall resilience and that resilience increases reliably with age. The participants in the 60 + age group demonstrated significantly higher resilience scores. The study showed there is an increasing trend of resilience among females compared to males suggesting there is difference between genders in the relationship between age and resilience but further study is needed in regard to this.

Proposed Conceptual Framework on Aging and Resilience

A reanalysis of the original dataset from the administration of the LRP-R has led to a proposed framework on the correlations between aging and resilience. Below is a chart that outlines resources and strategies older adults might utilize to strengthen their resilience as they age.

The chart above shows the predictors of resilience—positive well-being, optimism, awareness and utilization of learned and/or innate skill sets, the awareness and availing of external resources, and the routine practice of self-strengthening strategies. The implementation of these strategies improves anticipation and resolution of problems, as supported by Reivich and Shatté (2003) and Lavretsky (2014). Similarly, coping, which is considered a form of resilience (Lavretsky, 2014), may be defined as a mechanism that when applied in a healthy and productive way, may prevent or mitigate the impact of unhealthy stress.

Aging leads to numerous challenges physically, cognitively, and emotionally (Fry and Keyes, 2013). The proposed conceptual framework for aging calls attention to avenues that could be utilized to enhance one’s scope of support and build a more resilient self. The learned set of tools gained by personal experience enables older adults to disassemble problem cases and reconstruct solutions in a more mature manner (Patterson et al., 2009). This is demonstrated in the data used for this study, in which older generations show higher resilience levels than younger individuals. The inner resources (e.g., habits, outlooks, skills, values, strengths) gained through experiences of adversity then become usable, practical tools which younger adults have yet to develop in their personal and professional lives. External skills, meanwhile, are those that have personal, positive connections and meaning, which have shown to inhibit physical and/or emotional decline and reactivity (Milstein, 2010; Fry and Keyes, 2013). Resilience, therefore, is in part the mobilization of support, as is supported by the research of Milstein (2010); Fry and Keyes (2013), Agronin (2018), and Lavretsky (2014) on the subject.

Resilience and Aging: Coping With Permanence

In some ways, aging is facing the fact of impermanence, with physical and cognitive losses indicating a release on the vigor of life. However, there is one striking difference that is unique to the elderly: adapting to permanence. This is shown most particularly in the Allen and Starbuck (2011) contribution on resilient aging, and which brings a new, unique scope to this study on resilience and aging. There is little difference between younger and older adults in terms of resilience other than the increase in resilience with age. However, the perception of resilience differs between younger and older adults. Younger adults tend to view resilience as problem-focused active coping, while older adults commonly consider it to be tolerance and acceptance of negative outcomes. Compared to younger adults who commonly struggle with new losses, a large proportion of older adults are able to feel positive emotion despite overwhelming loss (Lavretsky, 2014).

In younger and most middle-aged adults, resilience comes with an opportunity for preparedness for, and, most importantly, prevention of similar challenges; for growth over loss; the return to and surpassing of normalcy to an even better position than before. For the elderly, resilience is most frequently used to cope with a change that cannot be reversed, but instead can be adapted to for the purpose of compensating for loss and achieving an alternative vision of normalcy. Resilience in old age is minimizing the impact of cumulative losses through spiritual and social connectedness, as well as creative compensation for once loved, but now challenging hobbies. This is achieved through the openness and adaptation to new ways of living, and thereby increasing strength and resilience in the face of new realities.

The largest difference between the resilience cycle, the conceptual framework of aging, and aging itself is not the emphasis of value added, but adaptability to loss and adjusting to pivotal life changes by creatively and positively dealing with the shrinking domains of one’s world. The resilience concepts therefore are no longer applied so as to prevent, but to create a new normal by dealing with losses associated with aging through acceptance and re-invention of long-practiced routines. One is then able to reflect on ways to minimize the losses and their subsequent impacts by adapting to different ways of doing old things, thereby avoiding discontentedness in life and reaching satisfactory, or even enhanced, quality of life.

Limitations and Future Research

There are threats to the validity of this study because it was self-selection and not a sample of any true population and the demographics were not monitored carefully enough to make any generalizations about representativeness. The study focused on school administrators during their time of practice, which excludes the elderly (over the age of 70) as a subject group. One limitation was the lack of literature on educational leadership and resilience in relation to aging. Considerations for future study include the transfer of concepts of resilience research in leadership to aging, conducting qualitative research such as interviews and focus forums of elderly people in regard to the “resilient strengths.” Further research should also be conducted on larger samples in each age range for more refined data on resilience in relation to the given demographics socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and nationality, especially in places that have experienced longevity explosions.

Conclusion

This continuation of our research using the Leadership Resilience Profile® demonstrates that resilience increases as individuals age. Men, particularly between the ages of 20–29, show significantly higher resilience than women of the same age group. Subjects over 60 demonstrate higher resilience rates than all other age groups. For the other age groups, no significant differences emerged.

Younger individuals perceive adversity as an inhibitor to achieve goals while older adults view adversity as challenging opportunities. As older adults deal with adversity at an ever-increasing rate (Lavretsky, 2014), they are able to adapt more readily and to seek aid from other available sources of support. Life experiences also allow the opportunity to perceive what must be adjusted and changed to improve quality of life. Positivity, connectedness with family and friends, sense of purpose, and proactivity facilitate a more resilient self, particularly in the face of permanent losses frequently experienced by older people (Lavretsky, 2014). The utilization of these strategies has proven to inhibit health issues caused by stress.

Resilient aging, therefore, is directly impacted by one’s focus on the future: where one wants to see oneself physically, emotionally, and cognitively in the future, deducing what must be done to actualize this goal, and actively pursuing it. It is proactivity toward not just surviving but thriving in the face of adversity and making future challenges easier to overcome, termed growth motivation (Fry and Keyes, 2013). Support and proactivity are the means for achieving positive growth orientation, quality of life, self-identity, purpose, inhibiting stress-related debilitation, and resilient aging.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material.

Author Contributions

DR conducted the research. AR did the literature review. Both authors contributed to numerous revisions.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Agronin, M. E. (2018). The End of Old Age: Living a Longer, More Purposeful Life. New York, NY: Da Capo.

Allen, K. E., and Starbuck, J. R. (2011). I Like Being Old: A Guide to Making the Most of Aging. Bloomington, IN: IUniverse.

Fry, P. S., and Keyes, C. L. (Eds). (2013). New Frontiers in Resilient Aging: Life-Strengths and Well-Being in Late Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Greitens, E. (2016). Resilience: Hard-Won Wisdom for Living a Better Life. Boston, MA: Mariner Books / Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Lavretsky, H. (2014). Resilience and Aging: Research and Practice. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Milstein, M. M. (2010). Resilient aging: Making the Most of Your Older Years. New York, NY: IUniverse.

Patterson, J., Goens, G., and Reed, D. (2009). Resilient Leadership for Turbulent Times. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Education.

Reed, D. (2018). Resilient educational leaders in turbulent times: applying the Leader Resilience Profile® to assess resiliency in relationship to gender and age. Rev. Perif. 10, 119–134. doi: 10.12957/periferia.2018.34777

Reed, D., and Blaine, E. (2015). Resilient women educational leaders in turbulent times: applying the leader resilience resilience profile® to assess women’s leadership strengths. J. Plan. Chang. 259–268.

Reivich, K., and Shatté, A. (2003). The Resilience Factor: 7 Keys to Finding Your Inner Strength and Overcoming Lifes Hurdles. New York, NY: Broadway Books.

Appendix

Leadership Resilience Profile (Revised) Scale

LRP-R

Instructions: Respond to the statements below regarding your leadership behavor using the following 5-point scale.

1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = neutral; 4 = agree; 5-strongly agree.

1. I have a positive influence in making things happen.

2. I expect that good things can come out of an adverse situation.

3. I focus my energy on the opportunities to be found in a bad situation, without downplaying the importance of obstacles.

4. I demonstrate an overall strength of optimism in my leadership style.

5. I gather the necessary information from reliable sources about what is really happening relative to the adversity.

6. I seem to look for the positive aspects of adversity to balance the negative aspects.

7. I seem to accept the reality that adversity is both inevitable and many times occurs unexpectedly.

8. I possess the overall strength of understanding current reality in my leadership role.

9. I make value-driven decisions even in the face of strong opposing forces.

10. I am able to privately clarify or publicly articulate my core values.

11. I rely on strongly held moral or ethical principles to guide me through adversity.

12. I demonstrate an overall strength of being value-driven in my leadership role.

13. I have an overall sense of competence and confidence in my leadership role.

14. I take a deliberate, step-by-step approach to overcome adversity.

15. I demonstrate the essential knowledge and skills to lead in tough times.

16. I maintain a confident presence as leader in the midst of adversity.

17. I reach out to build trusting relationships with those who can provide support in tough times.

18. When adversity strikes, I try to learn from the experiences of others who faced similar circumstances.

19. I have a strong support base to help me through tough times in my leadership role.

20. I try to learn from role models who have a strong track record of demonstrating resilience.

21. I can emotionally accept those aspects of adversity that I can’t influence in a positive way.

22. I demonstrate an understanding of my emotions during adversity and how these emotions affect my leadership performance.

23. I create time for replenishing my emotional energy.

24. I have the overall strength of emotional well-being in my leadership role.

25. I demonstrate an overall strength of physical well-being in order to effectively carry out my leadership role.

26. I never let adverse circumstances that inevitably happen disrupt my long-term focus on maintaining a healthy lifestyle.

27. I monitor my personal health factors and then adjust my behavior accordingly.

28. I find healthy ways for channeling my physical energy to relieve stress.

29. I take prompt, principled action on unexpected threats before they escalate out of control.

3o. I take prompt, decisive action in emergency situations that demand an immediate response.

31. I am able to make needed decisions if they run counter to respected advice by others.

32. I demonstrate an overall strength of making courageous decisions in my leadership role.

33. When I choose to take not leadership action in the face of adversity, I accept personal accountability for this choice.

34. I accept accountability for the long-term organizational impact of any tough leadership decisions I make.

35. I have an overall strength of accepting personal responsibility for my leadership actions.

36. In my leadership role, I acknowledge mistakes in my judgment by accepting responsibility to avoid these mistakes in the future.

37. I adjust my expectations about what is possible based on the current situation.

38. I put my mistakes in perspective and move beyond them.

39. I change course, as needed, to adapt to changing circumstances.

40. I search for creative strategies to achieve positive results in a difficult situation.

41. I refuse to give up in overcoming adversity, even when all realistic strategies have been exhausted.

42. I sustain a steady focus on the most important priorities until I achieve successful results.

43. I demonstrate perseverance in my leadership role.

44. I never let distractions interfere with my focus on important goals and tasks.

SCORING: To compute subscale scores, average the items associated with each LRP-R subscale.

Subscale Items

Optimism—Future 1–4

Optimism—Reality 5–8

Personal Values 9–12

Personal Efficacy 13–16

Support Base 17–20

Emotional Well-being 21–24

Physical Well-being 25–28

Decision-making 29–32

Personal Responsibility 33–36

Adaptability 37–40

Perseverance 41–44.

Keywords: resilience, age, adaptability, perseverance, wellbeing, efficacy

Citation: Reed DE and Reedman AE (2020) Reactivity and Adaptability: Applying Gender and Age Assessment to the Leader Resilience Profile®. Front. Educ. 5:574079. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.574079

Received: 18 June 2020; Accepted: 17 September 2020;

Published: 20 October 2020.

Edited by:

Pontso Moorosi, University of Warwick, United KingdomReviewed by:

Emily Winchip, Zayed University, United Arab EmiratesKay Fuller, University of Nottingham, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2020 Reed and Reedman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Diane E. Reed, ZHJlZWRAc2pmYy5lZHU=; Ashley E. Reedman, YXJlZWQwMDNAeWFob28uY29t

Diane E. Reed

Diane E. Reed Ashley E. Reedman2*

Ashley E. Reedman2*