- 1Department of English and Linguistics, Obama Institute for Transnational American Studies, Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz, Germany

- 2Department of Business and Economics Education, Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz, Germany

- 3Department of Neurophysiology, University Hospital of the Goethe University, Frankfurt (Main), Germany

The digital and information age has fundamentally transformed the way in which students learn and the study material they have at their disposal, especially in higher education. Students need to possess a number of higher-order cognitive and metacognitive skills, including effective information processing and critical reasoning to be able to navigate the Internet and use online sources, even those found outside of academically curated domains and in the depths of the Internet, and to solve (domain-specific) problems. Linking qualitative and quantitative research and connecting the humanities to empirical educational science studies, this article investigates the role of narratives and their impact on university students’ information seeking and their critical online reasoning (COR). This study focuses on the link between students’ online navigation skills, information seeking behavior and critical reasoning with regard to the specific domains: economics and medicine. For the empirical analysis in this article, we draw on a study that assesses the COR skills of undergraduate students of economics and medicine at two German universities. To measure COR skills, we used five tasks from the computer-based assessment “Critical Online Reasoning Assessment” (CORA), which assesses students’ skills in critically evaluating online sources and reasoning using evidence on contentious issues. The conceptual framework of this study is based on an existing methodology – narrative economics and medicine – and discusses its instructional potential and how it can be used to develop a new tool of “wise interventions” to enhance students’ COR in higher education. Based on qualitative content analyses of the students’ written responses, i.e., short essays, three distinct patterns of information seeking behavior among students have been identified. These three patterns – “Unambiguous Fact-Checking,” “Perspective-Taking Without Fact-Checking,” and “Web Credibility-Evaluating” – differ substantially in their potential connection to underlying narratives of information used by students to solve the CORA tasks. This analysis suggests that training university students in narrative analysis can strongly contribute to enhancing their critical online reasoning.

Introduction

Research Background

The digital and information age has fundamentally transformed the way in which students learn and the study material they have at their disposal, especially in higher education. To navigate the Internet and to successfully use online sources, even those found outside of academically curated domains and in the depths of the Internet, as well as to solve (domain-specific) problems, they need to possess a number of higher-order cognitive and metacognitive skills, including effective information processing and critical reasoning (e.g., Zhou and Ren, 2016; Shavelson et al., 2019). Learners who use the Internet must be able to assess the credibility and trustworthiness of sources and information (McGrew et al., 2018; Wineburg et al., 2018), they have to balance new information against their prior knowledge and any beliefs they may hold (van Strien et al., 2014; List and Alexander, 2017, 2018), and they must recognize how a given text or media format can affect not only their rational decision-making processes (Stanovich, 2018) but also their emotional judgment, which may lead to judgment errors, for instance, due to fast thinking and other biases such as motivated reasoning (Stanovich et al., 2013; Kahne and Bowyer, 2017).

This ever-changing information and learning environment has profound consequences for the teaching of domain-specific knowledge in higher education (e.g., Harrison and Luckett, 2019). A number of obstacles appear to make online learning challenging: first, students may acquire misconceptions by uncritically selecting sources that provide, for instance, misleading or even false information. Second, students may stop searching once they have arrived at a simple, unambiguous answer (Johnson et al., 2016). Third, their online search behavior may be limited by their previous knowledge and beliefs (van Strien et al., 2014; List and Alexander, 2018), which may cause them to stop short of taking full advantage of the wealth and diversity of information that Internet sources can provide. The dichotomy between knowledge and beliefs can hence be a particular obstacle to learning with the help of the Internet (Chiu et al., 2013; Hsu et al., 2014; van Strien et al., 2016).

In this context, researchers and educators attempt to create what Walton (2014) has called “wise interventions”: new instructional methodologies are required that will “vaccinate” students against biased information they find on the Internet, and that will guide their (self-directed) searches, information seeking, reasoning, and learning paths. These interventions, in turn, need to be closely related to what Pellegrino and Hilton (2012) have called “transferable knowledge” and “deeper learning,” i.e., developing students’ skills both to navigate the Internet successfully to gain domain-specific knowledge (and avoid the acquisition of erroneous knowledge and misconceptions) as well as to learn in a way that enables them to master concepts not merely superficially, but rather to apply their knowledge and skills to new contexts.

With the aim of developing effective teaching methodologies, recent empirical research has studied how students navigate the Internet, for instance, when solving (domain-specific) tasks (Collins-Thompson et al., 2016; Brand-Gruwel et al., 2017). Prior research indicates that students may lack the skills to understand how the content they find on the Internet is also generally shaped by (covert) narrative framing of information (e.g., metaphors and analogies) (de los Santos and Nabi, 2019; Luong et al., 2020), which may lead to a framing effect, and cognitive heuristics (e.g., confirmation bias, Brand-Gruwel et al., 2009; Powell et al., 2019; Zollo, 2019), and thus a biased selection of information, where students’ information seeking and reasoning are influenced by, for instance, positive or negative connotations of the presented information. However, little is known about how and to what extent narratives may affect students’ information seeking (incl. selection, interpretation, and use of information) and their critical reasoning when solving (domain-specific) problems (Ulyshen et al., 2015; Hoppe et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2018).

Study Framework and Research Objectives

Linking qualitative and quantitative research and connecting the humanities to empirical educational science studies, this article investigates the role of narratives and their impact on university students’ information seeking and their critical online reasoning (COR). This study focuses on the link between students’ online navigation skills, information seeking behavior and critical reasoning with regard to two specific domains: economics and medicine.

The conceptual framework of this study is based on existing methodology – narrative economics and medicine – and discusses its potential and how it can be used to develop a new tool of “wise interventions” to enhance students’ COR. The key to narrative economics and medicine is a combination of domain-specific knowledge and its narrative framing: it applies methodology from literary studies and narrative analysis to fundamentally rethink the use of narratives in economics and medicine (see section “Narrative Medicine and Narrative Economics”).

Our conceptual framework of students’ COR has some overlaps with related concepts such as “information literacy” (Armstrong and Brunskill, 2018) or “digital literacy” (Hartley, 2017). However, we expand these conceptualizations through the specific, additional focus on COR, which is related to various well-established traditions on critical thinking (Oser and Biedermann, 2020; see section “The Project ‘Critical Online Reasoning 192 Assessment’ (CORA)”; Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2020; Nagel et al., 2020). Moreover, we enhance the existing conceptual framework by adding the concept of narrative competence (see section “Narrative Medicine and Narrative Economics”).

In this article, we demonstrate that the information that is available on the Internet is never “neutral”: the content of this information cannot be disentangled from the narratives that this information is embedded in (Kay, 2000). Narrative carries knowledge: it has an effect on the reader, for instance through the metaphors and analogies it uses (Hallyn, 2000) and the perspectives it takes (Trzebinski, 1995). We argue, therefore, that learners need a specific skillset to recognize and to understand the (covert) narrative structure and framing of the information they use, and how this framing can influence their information processing and reasoning.

For the empirical analysis in this article, we draw on a study that assesses the COR skills of undergraduate students of economics and medicine at two German universities. To measure COR skills, we used five tasks from the computer-based assessment “Critical Online Reasoning Assessment” (CORA), which assesses the students’ skills in critically evaluating online sources and reasoning from evidence on contentious issues (Molerov et al., 2019; Nagel et al., 2020). In addition to conducting an open web search and evaluating online information, the students were also prompted to write an open-ended, argumentative response to each task. The difficulty lies in making a judgment in a short period of time while recognizing (covert) bias in information sources. The participants’ browser history and online behavior data were recorded, and their written responses (short essays) were evaluated by independent human raters using a newly developed and validated rating scheme (for details, see Nagel et al., 2020). On the basis of these data, we investigate the narrative framing of the online information processed by the students while working on the CORA tasks, and how an impact of this framing on students’ information processing and reasoning may manifest in their written responses.

We propose here that investigating students’ COR using multiple sources of information can be approached from two directions, which ultimately need to converge: first, through a qualitative narrative analysis of sources that the students used in their reasoning process, we can identify the information processing approaches students used based on both the sources’ content and their underlying narrative frames. The second approach is to analyze the students’ written responses in terms of whether they recognized the way in which a given information source, its context and content, its (covert) motives, and its potential conflicts with other evidence and/or the students’ prior knowledge and beliefs guided their information processing and reasoning approach. These analyses can provide us with an empirical insight into the relationship between students’ information seeking, the (covert) narrative framing, and the affective influence that sources on the Internet may have on students’ information processing and critical reasoning.

Based on this analysis, this article discusses how the methodologies of narrative medicine and narrative economics can be used to teach students how to critically and competently use online information for learning, to enhance students’ COR and help them overcome the aforementioned obstacles in online learning in higher education. By fostering COR rather than rather than superficially covering a wide range of learning content, narrative fields of study, in this case economics and medicine, may be a promising approach to help students deal with the current explosion of information in the classroom (e.g., McQuiggan et al., 2008). Drawing on this methodology as a potential teaching tool, this study also discusses the role of emotion in learning economics and medicine in higher education. Moreover, we argue that, given their attention to narrative and to the relationship between narrative and knowledge building, narrative medicine and narrative economics have much in common and can be transferred to other academic domains.

Consequently, we investigate narrative economics and narrative medicine as a way for students to identify the narrative framing of learning materials and texts, and hence foster their skills in recognizing that Internet sources are never completely “neutral” and may influence their information seeking behavior and reasoning through both argument and affect. By combining domain-specific knowledge with a narrative framing approach, students’ preconceptions and beliefs may be uncovered. In this way, narrative economics and medicine may enhance domain-specific learning by fostering students’ skills in understanding the difference between knowledge and beliefs as well as between informed reasoning and motivated reasoning (Kunda, 1990).

By using the methodology of literary studies, which stipulates that answers are seldom one-sided and stresses the role of ambiguity, narrative economics and narrative medicine might enable students to better deal with ambiguity – a crucial yet often neglected faculty in the classroom (Craig and Charon, 2017). Finally, by promoting skills required for critical reasoning and making decisions in the face of ambiguity, initially when dealing with diverging sources and contradictory information in the context of university learning and later in real-life practical situations, narrative economics and narrative medicine can encourage students to search for information in such a way that they do not stop once they have found an answer, but continue searching and eventually devise a complex, multi-layered, and potentially ambiguous answer and a more elaborate critical reasoning and problem-solving approach.

To explore narrative economics and narrative medicine as tools to enhance the online learning of higher education students in the Internet age, this article combines education and learning research with the humanities. As learning today consists of a combination of in-class teaching and (self-directed) learning using the Internet, this article proposes that narrative economics and narrative medicine may train and equip students with skills that help them use the Internet in a manner that enhances their COR and their domain-specific knowledge acquisition.

Prior Research

The Project “Critical Online Reasoning Assessment” (CORA)

To successfully learn and study in higher education in the Internet age, knowledge and skills for critically processing information including online reasoning are crucial. Since various studies reveal significant deficits among both graduate and undergraduate students (e.g., McGrew et al., 2018; Wineburg et al., 2018; Hahnel et al., 2019; Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2019), more research on students’ COR and its determinants is required. As some studies show in particular, information processing is significantly determined by students’ individual beliefs and preconceptions (e.g., Alexander et al., 2018; Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2020) indicating the impact of affective factors. In this context, the question arises to what extent students themselves may recognize affective influences, i.e., to what extent do they understand that the presentation of a given topic in an Internet source and its underlying (covert) narrative may shape their perception, attention, their emotions and their own decision-making? We consider this skillset an important facet of COR, and therefore used the data from the CORA study to investigate this question.

In CORA, undergraduate students from different study domains (including economics and medicine) were presented with tasks that describe real-life judgment situations (for an example, see section “Analyses of Student Responses”) and require the students to form an opinion on a given topic using an unrestricted web search (Nagel et al., 2020). To solve the CORA tasks, students were required to navigate the Internet and find suitable information sources on their own. One of the aims of the CORA study was to analyze how students select, evaluate and use Internet sources while working on a given CORA task and writing their response.

In the CORA tasks, students were given one website as a main source (see an example in section “Analyses of Student Responses”). Based on this website, they were asked to use the Internet and find other sources to form an opinion about a given topic and to evaluate the trustworthiness and the quality of the information presented on this website. CORA thus combined a website chosen by the task developer with online sources the students selected to make the CORA tasks as authentic as possible. Moreover, as Alexander et al. (2018) have shown, being able to form their own “search path” by doing their own research and autonomously selecting sources may enhance students’ (test) motivation.

This part of the CORA study is specifically related to research on the use of multiple sources in student learning (for an overview, see Braasch et al., 2018). According to Britt and Rouet (2012, p. 276), “studying multiple documents to learn about a topic can lead to a deeper, more complex understanding of the topic.” Moreover, since the CORA study requires students to autonomously find source material online to evaluate the source (website) given in the CORA task and to verify this information, this study is also related to research on self-regulated learning based on metacognitive skills (e.g., Neuenhaus et al., 2013; for “search as learning,” see Hoppe et al., 2018) as well as on information problem-solving (Brand-Gruwel et al., 2009).

At the same time, the students in the CORA study are required not only to evaluate the credibility and trustworthiness of the given website and its information but also, ultimately, to form their own opinion and justify this opinion in a brief essay referencing online information they used. In this respect, the CORA study is related to research on “web credibility” (Metzger and Flanagin, 2015; for “credibility evaluation,” see Metzger et al., 2010; for “information trust,” Lucassen and Schraagen, 2011), as well as on “trustworthiness.” For instance, Hendriks et al. (2015) designed an “inventory measuring laypeople’s ascriptions of an expert’s trustworthiness” to measure this skill.

Moreover, the CORA tasks also incorporate challenging issues that sometimes include moral or ethical aspects, for instance framed in terms of conflicting interests. The resolution thereof requires students to apply multiple aspects of ethical critical reasoning and decision-making. For instance, in one of the CORA tasks (illustrated in section “Analyses of Student Responses”), students were given a link to a website and encouraged to conduct additional research online, then asked to state and justify their decisions. This facet of COR can be linked to critical reflection, which was defined by Oser and Biedermann (2020, p. 90) as “a basic attitude that must be taken into consideration if (new) information is questioned to be true or false, reliable or not reliable, moral or immoral etc.” Therefore, critical reflection involves recognizing potential motives or (covert) interests and analyzing consequences of making a decision.

Narrative Medicine and Narrative Economics

Narrative medicine is an approach that emerged in the 1980s. Its founder, Rita Charon, a medical doctor who also holds a Ph.D. in literature, argued that with the rise of biotechnology in medicine, doctors had stopped paying attention to narratives. Introducing the model of narrative medicine, Charon suggested using the tools of literary analysis while listening to patients’ stories. She stresses the necessity of “honoring the stories of illness” (Charon, 2008).

Charon proposes narrative medicine not just as a tool to change doctor-patient communication but also as a way to make physicians recognize that narratives are a key component of medical knowledge. We tested this assumption by focusing on one case in particular, the history of the so-termed “broken heart syndrome” (Efferth et al., 2017). For decades, physicians had been approached by patients who, after the traumatic loss of a loved one, complained that their heart had been broken. The metaphor of the broken heart, moreover, has been one of the most powerful images to convey the extent of trauma, grief, or loss. Researchers then began to wonder whether the metaphorical quality of the image which was used to convey a physical condition might in fact prevent physicians from taking this condition seriously as a somatic condition. The recognition of the broken heart syndrome as a medical condition was hence hampered by the metaphorical, literary quality of the narrative in which it was conveyed. This obstacle may in part account for the fact that it took until 1990 for the condition to be recognized as a medical condition (Goldman, 2014; Efferth et al., 2017).

Narrative medicine sets out to demonstrate that narrative is central to the practice of medicine, both for knowledge acquisition and for doctor-patient communication. As a methodology, narrative medicine can serve to enhance physicians’ narrative competence. In this framework, narrative competence can be defined as the ability to “listen closely” (Charon et al., 2017) and detect hidden meanings and sudden turns in the narrative. Charon suggests that the act of doctors listening to patients’ narratives is akin to the careful reading of literary texts (Charon et al., 2017). By enabling them to pay attention even to minor details in patients’ narratives, Charon proposes, physicians will be able to arrive at more valid diagnoses. Moreover, the narrative competence will also serve to improve doctor-patient communication (Charon et al., 2017). Narrative medicine has substantial overlaps with narrative ethics (Craig and Charon, 2017), and it is also closely related to medical humanities (Banerjee, 2018; Spencer, 2020).

Narrative medicine is increasingly becoming an established methodology for the teaching of medicine (McAllister, 2015). One of the aims of narrative medicine is to enhance students’ self-reflection about their role as medical practitioners and about the kind of knowledge and skills required for a successful professional development in this domain. Students are trained in narrative competence, and they are taught to recognize that knowledge in medicine is constructed not only through data and biotechnological diagnostics, but also through narrative. At the core of narrative medicine as a teaching methodology lies the idea of estrangement (Spiegel and Spencer, 2017). For instance, medical students are asked to read literary texts such as Michael Ondaatje’s The English Patient. These texts often do not feature specific medical settings but rather deal with concepts of care: how friends or relatives care about one another, and the protagonist’s need for care. In narrative medicine courses, students are asked to relate to the texts in an affective manner: they relate the text to their own understanding of care. Through the “detour” of literature, medical students hence come to reflect on their own practice as physicians. After this intervention by narrative medicine, they may approach the clinical setting in a new way, and they may listen differently to patients’ narratives. While narrative medicine is increasingly becoming an established tool in the didactics of medicine, its effectiveness for teaching in higher education still needs to be explored empirically (see section “Narrative Analysis in Educational and Learning Research”).

It may be indicative of a paradigm shift across academic disciplines in a particular period of time that after Charon et al. (2017) had developed the narrative medicine approach – which understood narrative to be essential to the practice of medicine – the “narrative economics” approach was developed by Yale economist and Nobel laureate Shiller (2017).

Shiller integrates the fields of economics, anthropology, psychology, and literary studies to create this approach. Narrative economics is conceived by Shiller as a methodology for redefining knowledge in economics: so far, knowledge in economics has been conceived mainly in terms of theories and data; the role of narrative has been underestimated. By contrast, Shiller suggests relating to economic events such as economic downturns or fluctuations in the stock market through the narratives that are created around these events. Consequently, he proposes that economists need to be equipped with narrative competence (Shiller, 2019).

Shiller evokes the work of biologist Gould (1980) and his image of the “homo narrator.” Following Gould, Shiller (2017) suggests that humans are a “storytelling animal”: “…the human brain is built around narratives.” Shiller (2017) goes on to look at important events in the history of economics like the stock market crash of 1929 to focus on narratives and “narrative history” as a potential reason for why we remember and forget certain events. He argues that economists need to team up with narrative scholars, such as literary researchers, to unpack the power of narratives in conveying economic meaning: “Not everyone is equally proficient at understanding narratives, and economists are among the worst at appreciating them” (Shiller, 2017). Through narrative analysis, we may be able to understand the role narratives plays in what we might call economic memory. For instance, the images and metaphors we connect with the crash of 1929 are those of people losing their life savings overnight, of the stock market crash sparking off the Great Depression, and “…we’ve been worried about it happening again all this time, because the narrative isn’t forgotten” (Shiller, 2017).

Overall, according to Charon et al. (2017) and Shiller (2019), narratives are at the core of knowledge acquisition in medicine and economics. In this article, we focus on the overlaps between these two methodologies. Based on prior research (Charon et al., 2017; Shiller, 2019), we argue that it is fruitful to link the methodologies of narrative medicine and narrative economics. Moreover, we argue that these two methodologies can be used for both narrative analysis (see section “Qualitative Narrative Research”) and teaching intervention (see section “Narrative Analysis in Educational and Learning Research”): first, in the following section, we show how narrative analysis – which lies at the core of both narrative medicine and narrative economics – can be used in qualitative narrative research. Second, based on the narrative analyses in this article, we propose that narrative medicine and narrative economics can be employed to change students’ online information-seeking behavior and foster COR in the domains of medicine and economics, and that this approach can be transferred to other domains (see section “Limitations and Future Perspectives”).

Methods and Analysis

Qualitative Narrative Research

To investigate our research question and provide insights into the potential influence of narratives on the extent to which students critically evaluated the information they were confronted with on the Internet, and which led them to come to certain conclusions, we connected qualitative narrative analyses of both students’ written responses and the online information they used. Narrative analysis, as proposed here, shows overlaps with reconstructive hermeneutics, which are widely established in educational research (Malpas and Zabala, 2010). Like reconstructive hermeneutics, narrative analysis aims to identify and to “reconstruct” implicit patterns through text analyses. However, we expand this existing research by particular focusing on framing, affect, and metaphoricity.

Narrative framing, for instance, the use of metaphors (e.g., “broken heart” and “economic crisis”), analogies (virus as an “invisible enemy”), change of perspective (“life-value” vs “money-value”) is covert; i.e., students/learners often do not recognize narratives and their role in information processing and decision-making. Prior research has shown that linguistic framing influences reasoning (e.g., Gibbs, 1994): narratives have a powerful influence on reasoning, as students select and use information that is consistent with a certain narrative frame and that confirms their initial knowledge and beliefs (“vaccination is poison”), while neglecting any contradictory information (e.g., Thibodeau and Boroditsky, 2011). Thus, narratives may cause a so-termed framing effect due to a cognitive bias (e.g., confirmation bias) and lead to a biased selection of information, and students’ reasoning may be influenced by, for instance, positive or negative connotations of the information (Rumelhart, 1979; Pinker, 2007).

Building on this research, we analyzed the influence of narrative framing on COR by assessing economics and medical students. In the CORA study (see section “Sample and Procedures”), we retraced the sources students used on the Internet as well as their simultaneous use of multiple documents from various sources in their responses to the CORA tasks (for details, see Nagel et al., 2020). According to Hahnel et al. (2019, p. 524), “however, to use variables generated from process data (e.g., mouse clicks with timestamps) sensibly for educational purposes, their interpretation needs to be validated with regard to their intended meaning.” Thus, these quantitative data from the CORA study are linked to qualitative narrative analysis as proposed in this article. Based on a methodology from narratology often used in literary studies, we analyze online information used by students in terms of its underlying narrative features: this narrative analysis explores the ways in which (domain-specific) content was put into a “story” format. The qualitative narrative analyses based on different categories, for example, the structure of the text, the main topic of the “story,” narrative perspective (first-, second-, or third-person perspectives), mode of speech (direct/indirect speech), choice of metaphors, as well as the affective dimension involved in these textual features.

Crucially, narrative analysis as a tool for the assessment of the linguistic framing of information is based on the fact that rhetorical strategies are not always intentional. The speaker might, for instance, use metaphors or formulations that may lead the readers to become predisposed in certain ways, without actually being conscious of the effects of their rhetoric. Narrative analysis, along with discourse analysis, has thus tended to focus less on the speaker or producer of an utterance, than on the effects produced by the utterance itself. In this context, the evaluation of the expert’s expertise in a given domain may be equally based on the students’ ability to unpack not just the argument, but its underlying narrative and to recognize the narrative affect which a source might convey.

Consequently, we analyzed students’ written responses to web search tasks to see whether they recognized the narrative framing of the information they used. Based on the data from the CORA study, we focus on the research question did the narrative influence how the students perceived and processed the information and how they reasoned based on the online sources they used?

When analyzing the students’ written responses, we therefore focused on identifying clues as to whether the narratives of the online information they used influences students’ information seeking behavior and their COR. We suggested that if affective influence is key to narratives, this notion can also be applied to the interpretation of students’ responses, for instance, how students assess the trustworthiness of expert opinions on topics described in the CORA tasks (for an example, see section “Sample and Procedures”). We proposed that a narrative analysis may also contribute to an understanding of students’ opinion-forming processes and their decision-making when learning with the help of the Internet.

Analyses of Student Responses

Sample and Procedures

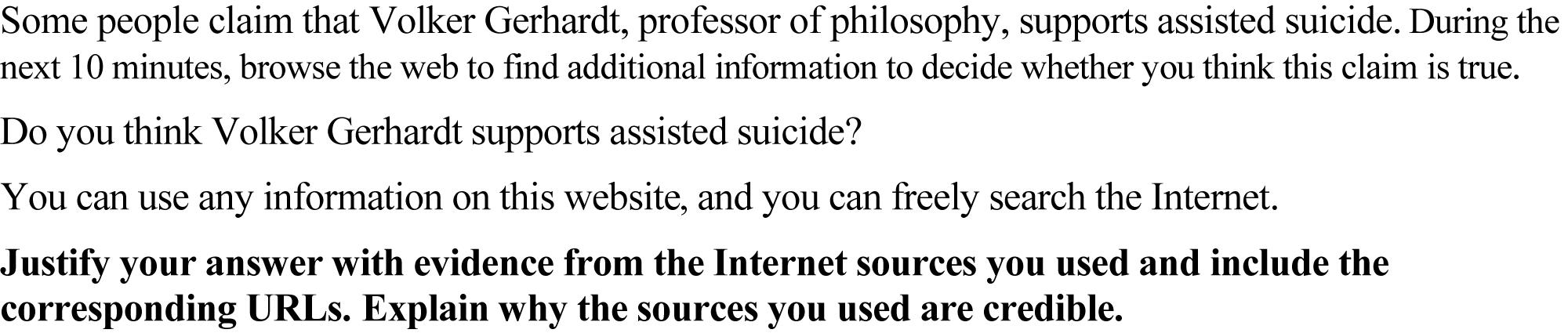

In the first step, we took an initial look at the students’ written responses, i.e., the short essays, in which they described their decision or conclusion related to the evaluation of the credibility of the information presented on the website linked in the CORA task. While we cannot discuss all student responses collected in the study, we instead focus particularly on one CORA task “assisted suicide,” which dealt with aspects of moral reasoning (see Figure 1). We focus on this task, since we had the most written answers from students in both domains for this task, and they were on average longer than for the other CORA tasks, which could be due to the special moral and ethical aspect of this task. For the narrative analyses, the length of the written student responses was an important qualitative factor of the data.

Thus, the subsample used in this narrative analysis consists of 19 medical and 47 economics students from two German universities (the data of 11 students from other domains were excluded in the following analyses). The data were collected in the winter semester of 2019/2020. The assessments took place in a research laboratory under controlled conditions. To ensure test motivation, for their participation in the study, the students received credits for a study module. The majority of the 66 participants were in their first study year; about two thirds of the participants were women.

The subsample can be considered very large with a view to the comprehensive qualitative analysis conducted in this study. Moreover, this sample can be considered representative for the total sample of the CORA study in terms of the gender ratio and the study semester. However, the medical students are underrepresented in this sample (for limitations, see section “Limitations and Future Perspectives”).

In this CORA task that deals with the topic of assisted suicide, students were asked to discuss, to evaluate and to justify an expert’s opinion on assisted suicide presented on a website linked in the task. Here, students were first not explicitly asked what they thought of assisted suicide or even whether the expert in the article was credible or trustworthy. Rather, the first question in the task was formulated on a much more pragmatic level: “Do you think that Volker Gerhardt [the expert cited on the website linked in the task] supports assisted suicide?” Remarkably, this question, which seems to be only content-based at first sight, actually elicited student responses that precisely addressed these more focused questions of trustworthiness and the credibility of sources. In the subsequent question, students were asked to explain why they think this source is credible. In particular, they were asked to find additional information on the Internet and justify their responses with evidence from the Internet sources they used. In the next section, we present the key results of our qualitative narrative analysis.

Results

When analyzing student responses as described in section “Qualitative Narrative Research,” we identified three distinct patterns: “Unambiguous Fact-Checking,” “Perspective-Taking without Fact-Checking,” and “Web Credibility-Evaluating,” which can be linked to existing research: for instance, the role of fact-checking was established in recent studies about university students’ online search behavior and its role in their learning (e.g., McGrew et al., 2019). Moreover, the ability to evaluate the credibility and trustworthiness of a given source has been at the core of recent research on online learning (e.g., Gierth and Bromme, 2020).

The majority of the student answers correspond to the pattern of “web credibility-evaluating” (56 percent); this was closely followed by the pattern of “perspective-taking without fact-checking” (41 percent). Only very few answers fell into the pattern of “unambiguous fact-checking” (3 percent). Regarding the pattern of “web credibility-evaluating,” many of the students seemed to be at a loss for criteria they could use to evaluate the credibility of a source. While many students referred to the trustworthiness of the source, for instance, of websites hosted by national newspapers (Die Welt, Süddeutsche Zeitung), others simply remarked that the website “looked” trustworthy because “it cited experts.”

In the following, we describe students’ task responses with regard to these three patterns. While some students’ responses showed elements of two or more of these patterns, here, we will elaborate on the answers that fell squarely into one of the profiles. At the same time, however, we demonstrate that this pattern-based analysis can only be the first step toward a more complex investigation of students’ online search behavior and their reasoning. Therefore, we conclude by indicating perspectives for further, more fine-grained research (see sections “Analysis of the Narrative Framing of the Most Commonly Used Online Source” and “The Impact of the Narrative Framing on the Student Responses to the CORA Task”).

Unambiguous fact-checking

One pattern of student responses distinguished among the short essays can be defined as “Unambiguous Fact-Checking.” Prior research has outlined the relevance of “fact-checking” for students’ critical evaluation of online sources (e.g., McGrew et al., 2019). In our analysis of student responses, we investigated in particular whether students’ search behavior indicates that they verify the “facts” stated in the original source. For instance, the original article may cite the opinion of a specific expert. Students can then “check” if this person is really an expert on the topic at hand, or they can neglect to do so. This pattern was termed “unambiguous” fact-checking, since this initial evaluation of the facts presented and/or experts cited in the source was only one of the steps of a more critical evaluation of the source that students were asked to make in the CORA tasks (see Figure 1). The next steps might include a more critical reflection on the quality of the facts presented in the online information used by students when solving the CORA tasks. For instance, the expert may be from a discipline that is not central to the topic at hand: a professor of physics for example is an expert in his field, but his expertise may not be pertinent to the specific task topic (assisted suicide). In this context, our research relates to the well-established approaches in ‘web credibility’ research (Bromme and Thomm, 2016).

In the following, we describe the responses of the student group of unambiguous fact-checkers in more detail. This group of students thinks that Volker Gerhardt supports assisted suicide: “Based on my research, I would agree with the statement. Especially on the basis of his answer to a reader’s question in the Tagesspiegel. He is also an expert on Nietzsche’s philosophy as well as on theological philosophy. Nietzsche, who, as is well known, advocated ‘atheistic’ theories and declared ‘God is dead,’ freed thinking from the obstinacy of a God and the interpretation of the Church. Thus, it is not morally wrong to kill a human being if it so desired.”

A number of things are remarkable about this pattern of responses. The first aspect relates to the question whether the students accept the knowledge and trustworthiness of the expert himself. In the article, Volker Gerhardt is introduced as a professor, a philosopher, and a person deeply concerned with the question of assisted suicide. In this response, the student first follows the “lead” that the article has established, namely that Volker Gerhardt’s expertise as a philosopher is key to the debate on assisted suicide. Second, however, the student goes on to double-check what this philosophical expertise is based on. Crucially, she does not refer to the fact that Gerhardt is a professor at the Humboldt University Berlin nor that he is a member of the Berlin Brandenburg Academy of Sciences, but she focuses on his expertise regarding Nietzsche.

The student follows two leads in particular: first, she “checks” the website given in this task by googling a YouTube video: an interview with Volker Gerhardt. This suggests that the YouTube videos were used to double-check the impression that the student gained through the website. Moreover, she enhances the presence of Volker Gerhardt by adding the visual impression (YouTube video) to the sense that we get of him from the website. Secondly, the student sets out to verify Professor Gerhardt’s expertise by following up on Nietzsche, one of the philosophers that he specializes on in his work. The student thus not only googles an interview with Volker Gerhardt, but also consults a Wikipedia source on Friedrich Nietzsche. Finally, in the answer, she states that “everyone knows that Nietzsche declared that God is dead.” The URL she provides below her short response, however, suggests that she just looked Nietzsche up on Wikipedia, and may not have known or remembered all these aspects in detail before consulting Wikipedia.

With regard to an underlying pattern, this student’s search behavior and reasoning approach indicate that she is by no means uncritical in her use of sources: she verifies the trustworthiness of the source as well as the credibility of the expert witness (Volker Gerhardt). However, her search behavior and reasoning also indicate that she might not recognize the narrative patterns which underlie the framing of the expert by the sources she consults.

Theoretically, the Internet could be an ideal source for learning, as there is an almost infinite number of sources available. However, for COR, the students need to recognize and understand alternative perspectives and arguments in a given source and hence alternative forms of search behavior and online information processing. This student’s search behavior hence corroborates one of the findings from prior research (see section “Research Background”), namely that students may stop searching once they have arrived at a simple, unambiguous answer (Johnson et al., 2016).

At the same time, it can be debated whether the student’s response is only a form of simple fact-checking or whether it exceeds this process. The student quoted here goes on to investigate not only the expert himself, but the expert’s own “expert,” namely the philosophy of Nietzsche. Yet, the student may not understand that Nietzsche’s philosophy is a highly complex philosophical theory with its own political and ethical implications and cannot be reduced to atheism alone. Students may therefore not understand the political tendencies and ethical associations that come with the Nietzsche reference. For follow-up empirical research (see section “Limitations and Future Perspectives”), this opens up an important question: where does the student’s fact-checking end? Which facts do they assume require verification through further sources?

Perspective-taking without fact-checking

Another group of students whose pattern we described as “Perspective-Taking without Fact-Checking” do not focus on Volker Gerhardt at all in their responses, but rather on the question of assisted suicide more generally. This can be demonstrated with the following statement: “In his interview, Volker Gerhardt states that it is an incredible imposition to demand that other people hold him (doctor) responsible for the death of another person. Because the doctor would not know in this state what it means for him and his conscience. The website www.bpb.de is a credible internet source, as many concrete topics are worked out very specifically and there is a lot of input.”

In contrast to the first group of students, the unambiguous fact-checkers, this group of students does not investigate the trustworthiness of the cited expert. Given the key relevance of fact-checking for critical reasoning and the evaluation of online sources, these students may hence be easily misled by the original source. Student answers from this group show that they immediately form an opinion of their own about the topic, without recognizing that this opinion-forming may be guided by the underlying narrative of the source.

Remarkably, this pattern of responses focuses on an aspect which was only marginally mentioned in the original source, namely the ethical dilemma of those who are called upon to assist another person’s suicide. To this extent, this pattern does not follow the “lead” laid in the article, namely the framing of this debate through the person and professional expertise of Volker Gerhardt. Notably, however, the student refers to the trustworthiness of one source he consults. The source is the Federal Agency for Civic Education, and hence a federal, non-partisan institution. While the student rates this source as trustworthy, however, he does not refer to the owner of the site and hence the institution itself – the Federal Agency for Civic Education – but rather focuses on the content provided on this site: “The website is a credible internet source, as many concrete topics are worked out very specifically and there is a lot of input.” This response corroborates research proposed by Wineburg et al. (2018), who state that students often cannot be seen as “fact checkers” and that they do not check the origin of a given website to find out where they have “landed.”

Web credibility-evaluating

Another pattern of student responses, which we defined as “Web Credibility-Evaluating,” focused not on the first question – whether or not Volker Gerhardt is in favor of assisted suicide – but directly responded to the second question and discussed the trustworthiness of the source (Scharrer et al., 2019). Student answers in this group indicate recognition of the fact that they must first check the trustworthiness of the source (e.g., newspaper, journal, and blog). The answers show that for this evaluation, students rely on their own prior knowledge of the (German) media landscape. However, the responses also indicate that once students had established the trustworthiness of the source, they did not go on to question the narrative framing of the article given in this source.

Since students were asked in this CORA task to search for websites relating to Volker Gerhardt’s opinion on assisted suicide, some referred to the article in the Süddeutsche Zeitung (analyzed in section “Analyses of Student Responses” below), while others used other sources. One student in this group thus refers to an article about Gerhardt in the Tagesspiegel: “Volker Gerhardt is quoted on this page. This quote contains statements by Gerhardt which clarify his attitude toward assisted suicide. Basically I judge the Tagesspiegel as a rather serious site, but with journalistic ones it can never be ruled out that false information may creep in. This can be seen in the Spiegel scandal, where false information was subsequently uncovered in articles (Relotius). In this case, however, I think it is unlikely that Gerhardt’s statements in the article were falsified. However, one cannot assume this to be 100% true.”

Remarkably, the student was familiar with a “scandal” in which the Spiegel news magazine was involved, and hence goes on to question the trustworthiness of even established newspapers in general. From this observation, however, she goes on to question whether Gerhardt’s opinion, which was quoted in the Tagesspiegel, was “fake” as well. At the same time, the student neglected another relevant perspective – compared to the “Perspective-taking” pattern, and did not double-check the given information – compared to the “Fact-checking” pattern.

In terms of a typology of student online information seeking and their COR that emerges from these preliminary qualitative analyses, it became evident that students of this group paid much more attention to the source than to the narrative itself. They hence understood credibility mainly as pertaining to the source in which a given report was provided, for instance, weighing the Tagesspiegel against the Süddeutsche Zeitung. The students who had thus established credibility, might have followed the narrative framing of the source itself. This suggests that training students in narrative analysis can strongly contribute to enhancing their COR (see section “Narrative Analysis in Educational and Learning Research”).

Overall, other students’ responses assume some of these reasoning approaches and arguments as well, which can only be referred to in an exemplary fashion here. Some refer to Gerhardt as “the professor,” suggesting that it is his status and expertise that makes him a trustworthy source (indicating the “authority bias,” Metzger et al., 2015). Other test participants also consult the website of the Federal Agency for Civic Education but unlike the student quoted above, they understood the institutional, non-partisan character of this source.

The three patterns of student CORA task-solving behavior that we have identified in their written responses – “Unambiguous Fact-Checking, Perspective-Taking without Fact-Checking, and Web Credibility-Evaluating” – differ substantially in their potential connection to underlying narratives. Of these types, it could be argued that the third response pattern – Web Credibility-Evaluating – seems to be the least impacted by narrative. This type of response does not take into account the expert’s narrative at all but is rather concerned with the source it is cited in (Tagesspiegel). This may be especially problematic in that students may not recognize how the narrative form in which the information was given impacted their own reasoning strategies. Since this group of students shows the least understanding of how narrative framing can guide or even manipulate their own reasoning, this group may be most susceptible to acquiring misleading information or even erroneous (domain-specific) knowledge through Internet searches. Compared to this type of response, the first pattern, the “Fact-Checking,” shows the highest impact of narratives on their own reasoning. Remarkably, this group of students appears to at least implicitly recognize a number of related facts, which they proceeded to cross-check with the given information (the reference to a specific expert-philosopher, and the expert’s reference to another expert). The “Perspective-Taking and Non-Fact-Checking” group of students show the least impact of narratives on their own reasoning.

To establish the relevance of narrative knowledge (Carroll, 2001) and narrative competence for teaching economics and medicine in higher education, however, we must go beyond defining these initial patterns of students’ search behavior. To engage in COR, students need to understand how sources can influence or even manipulate their opinion-making. They need to be able to detect narrative framings in all their complexity. To elucidate this complexity, we will now analyze the source (online article) that most students based their answers on. We will then reconstruct the narrative framings which may have influenced the students’ responses.

Analysis of the Narrative Framing of the Most Commonly Used Online Source

In the next step, we qualitatively analyzed the websites which were most commonly used by students in their written responses. The aim of this analysis step is to reconstruct the leads given by the source which students may follow in their responses without recognizing they were being “guided” by these leads (see section “The Impact of the Narrative Framing on the Student Responses to the CORA Task”).

First, a content-based narrative analysis might start off by noting that the information source most commonly used by students when solving the CORA task “assisted suicide” was an article from one of the largest daily newspapers in Germany Süddeutsche Zeitung. In terms of credibility, it can thus be argued that this is a reliable and multi-perspective source of information. Upon closer analysis, however, we might delve into the question of perspectives: (i) Who are the experts that the article cites, and how exactly are they being cited? (ii) What are their credentials, how does the article frame their narrative authority and their authority on the subject? (iii) What metaphors are being used, what discursive or narrative frameworks are evoked?

Seen in these terms, the narrative framing of the (task) topic of assisted suicide may in fact be quite surprising. First, it should be noted that the narrative is woven around one expert in particular, a professor of philosophy at the renowned Humboldt University in Berlin, Volker Gerhardt. This framing has a number of implications for the way the debate on assisted suicide is being framed:

First, the topic at hand is looked at from an academic perspective. Moreover, it is framed less as a political or societal issue, but more as an ethical one. Philosophy is hence implicitly reframed as being integral to ethics. It may be notable in this context that the question of ethics is itself a highly complex one. In the field of bioethics, for instance, experts might be situated in the domain of theology (as in the case of the former head of the German National Ethics Committee, Peter Dabrock), or medicine. At the same time, however, the fields to which the expert refers in his own opinion on assisted suicide by far exceeds philosophy and contains references to legal parameters as well as social and cultural ones. The point which might be made here, in particular, is that legal parameters are reported through the philosopher’s perspective. The article does not cite or feature another interview with a legal expert. Even as on the surface, the fields that the article refers to as relevant for assessing the topic of assisted suicide range from philosophy to ethics and law, all of these fields are represented by just one particular expert, who is a professor of philosophy.

Second and perhaps even more importantly, while the article uses direct speech to convey this expert’s opinion on the subject, all other experts or potential discussants on the subject are present in the article merely through reported speech. Thus, the article notes, in reported speech and as if in passing, that representatives of the church and palliative care physicians have also referred to palliative care as a relevant factor in the context of the debate on assisted suicide. Narrative analysis here needs to be complemented by linguistic research to provide an insight into the differences in using direct or reported speech in a given text, and the different effects this will have on the reader.

Third and just as importantly, there is one metaphor used in the expert’s direct speech which evokes a very particular historical context and a very particular emotional register. At what can be said to be an argumentative pivot of the article, the expert evokes the question of human rights. What happens, then, once the paradigm of human rights and its historical and ethical significance is evoked? Once the question of assisted suicide is framed in terms of human rights, the emotional subtext may have shifted imperceptibly. The absence of human rights, both historically and geographically, is implicitly framed as a context in which authorities can arbitrarily exert their power; where members of marginal communities – communities of color, working-class communities, or indigenous peoples – can be arrested and detained without proper trial. Historically, the habeas corpus act was an important precursor to the Declaration of Human Rights. Because of this declaration, which just celebrated its 70th anniversary in 2018, no-one can be arbitrarily arrested, and everyone, regardless of their provenance, race or social status, has the right to a fair trial. Conversely, the time before the Declaration of Human Rights appears to us, in retrospect, as the dark ages of a world without ethical recourse.

What does it mean, then, to reframe the topic of assisted suicide in terms of the human rights debate? It could be argued to mean that the current moment described in the article, in which no clear guideline for assisted suicide exists as yet, parallels the time before the institutionalization of human rights. Implicitly, then, the equation of the legal regulation on assisted suicide with the declaration of human rights frames medical practitioners as potentially holding arbitrary or at least unjustified power over patients who are powerless to resist their authority. Regardless of whether we are in favor of or against assisted suicide, it may therefore be important for us to note that introducing the metaphorical link of assisted suicide to human rights strikes a powerful emotional and affective chord. To the extent to which we may tend to identify with or at least accept the authority of the speaker who makes this connection, then – an identification which may be enabled by the fact that this speaker is the only one whose ideas are represented to us in direct speech – this emotional influence may be all the more powerful.

The Impact of the Narrative Framing on the Student Responses to the CORA Task

How can this qualitative narrative analysis of the information source that students most commonly used when solving the CORA task be linked back to their responses to this task? On the basis of the content analysis outlined above, we now return to the students’ written statements.

One particularly remarkable aspect here is that none of the students question the expertise of Prof. Gerhardt, indicating the cognitive heuristic “authority bias” among all test participants (Metzger et al., 2015). They did not, as they could have done, wonder whether there are other experts on the topic of assisted suicide, and they did not look for other source materials. Rather, their short essay responses suggest that they invariably followed the “lead” (discussed in the section “Analyses of Student Responses”) provided by the online source.

Moreover, students’ responses indicated that they did not recognize how and why their trust in the expert’s knowledge was established. As to the reasons for this conviction, almost all of the students referred to the credibility of the Süddeutsche Zeitung as a representative and unbiased source of information. Yet, this too may fall short of the actual complexity of the information landscape in the Internet age. While the Süddeutsche Zeitung is considered a trustworthy source, the choice of experts featured in their articles may nonetheless be biased in one direction or another.

With regard to the impact of the narrative framing of the used information in the student responses, three patterns among participants have been identified, which differ in terms of their search and reasoning approaches as well as in the extent to which the given information and arguments were recognized or neglected. The findings indicate that the participants within these groups evaluated the credibility, trustworthiness and relevance of the sources and incorporated arguments differently, whereby most of the students, however, did not weigh or compile the information and arguments provided, but rather selected information – most likely related to their own (prior) knowledge and beliefs, indicating the “confirmation bias” (Metzger et al., 2015; Zollo, 2019).

In particular, the students with the pattern “Web Credibility-Evaluating,” who had established the credibility of the Süddeutsche Zeitung, did not even remotely suspect that an article in this trustworthy newspaper might steer their opinion in a certain direction. This pertains to findings from prior research (outlined in section “Research Background”). For instance, none of the students picked up on the fact that Volker Gerhardt’s opinion was given in direct speech, while other experts’ opinions were only referred to indirectly. In reporting their own search behavior, students may thus not have recognized that narrative perspective and linguistic patterns (direct vs indirect speech) can have an emotional impact on their information processing and reasoning. In journalistic writing, for example, direct speech can serve to establish an identification between the reader and the person who is being quoted. This identification can occur on the level of content as well as its emotional impact.

Finally, none of the students picked up on the metaphors that Volker Gerhardt used in his defense of assisted suicide (assisted suicide as a human right). Students may thus not have recognized the role of metaphors not only in guiding their reasoning and decision-making, but in having an emotional impact on their reaction to the expert’s statement. By linking the students’ responses to a narrative analysis of the source they most commonly used, we can thus point to the lacunae in students’ COR.

Discussion

These lacunae can then specifically be targeted in instructional interventions (see section “Narrative Analysis in Educational and Learning Research”). One of the aims of such an intervention would be to enable students to make the best possible use of the Internet as a tool for critical reasoning. Most importantly, such interventions should enable learners to continue searching even after they have arrived at a simple, unambiguous answer (as in the pattern “Unambiguous Fact-Checking”). In students’ responses to the CORA task, this became especially manifest in their reaction to the expert. They questioned neither Gerhardt’s expertise on the subject at hand (assisted suicide) nor the metaphors he used to steer readers’ emotive reaction to support his own opinion.

An instructional intervention can equip students with the skills they need to continue searching even after they have arrived at a simple, unambiguous answer (Berliner, 2020). Through such interventions, students can learn to deal with ambiguity, which may lead them to a much more complex grasp of the topic. The Internet may then prove to be the ideal tool to foster their ability to devise complex, multi-faceted responses: it puts them in a position to continue searching for more complex responses. In the CORA task, this would have meant that the students do not stop at one expert (Volker Gerhardt), but rather look for other, alternative experts, and for other, alternative disciplines: from theology to law and medical ethics.

Literary and linguistic analysis may thus be a useful tool to teach students to understand how a given text (as in our case in a newspaper by the Süddeutsche Zeitung or elsewhere) may affect them. In the source in question, students are able to relate to the expert (in this case, a professor of philosophy) more directly and in a more personal and possibly, a more affective manner, since all other sources are only referred to in indirect speech. Once students understand this potential bias, they may then search for sources with alternative experts, and their final judgment and decision may differ significantly from the results of the CORA study (see also Nagel et al., 2020).

Our qualitative narrative analysis clearly emphasizes that students’ COR is essential when learning with the help of the Internet. This is highly important for our consideration of the Internet as a tool for learning in the information age. In the CORA study, potentially, students would have had a wide variety of source materials available. As our analysis shows, however, that since they followed only the “lead” that had been laid out for them in the one source of information, they did not use the other materials that they could theoretically have consulted. This is where “wise interventions” may be necessary to train students in COR skills that would allow them to make the best possible use of the Internet as a learning resource, and to enhance their learning and knowledge acquisition.

We illustrate in this article that to design a “wise instructional intervention,” it is essential to combine learning data, such as from the CORA study and the methodology of narrative economics and medicine. For an intervention of this kind to be instructionally effective, a qualitative narrative analysis of the material and its content that students use for learning is required. As illustrated in the narrative analysis in this article (see section “Analysis of the Narrative Framing of the Most Commonly Used Online Source”), the extent to which abstract arguments are conveyed through human interest narratives needs to be especially focused: for instance, what (personal) stories are used in the text? By means of which linguistic or rhetorical features is affect achieved? On the basis of the narrative analysis, we can derive a set of hypotheses about how the narrative framing of learning materials can impact students’ information processing and their reasoning. The idea which underlies this assumption is that the (learning) source establishes some “leads” to guide their readers’ reasoning approaches and decision-making. Our findings from the analyses of students’ actual responses, which were provided in short essays in the CORA study (see section “Analyses of Student Responses”) suggest one particular hypothesis in this context, namely that most students tend to follow this “lead,” since they did not recognize the strategies used in the text to elicit precisely the respective response.

As our study demonstrated, the methodologies of narrative medicine and narrative economics can be used not only for qualitative analysis in educational and learning research but also for teaching interventions. Both methodologies acknowledge that narrative framing is inseparable from content in medicine and economics. When linking this consideration to teaching and learning research, narrative knowledge is seen as a concept which explores how domain-specific content is influenced by the narratives through which it is conveyed (Dettori and Paiva, 2009; Clark, 2010; Goodson et al., 2010). Thus, language is not a neutral “tool” through which (domain-specific) content is conveyed, and it can significantly affect the presentation of content. It is therefore noteworthy that research into the role of affective influence is increasingly being conducted in a number of disciplines and academic fields in recent years, such as, for instance, in law (Bandes and Blumenthal, 2012) or narrative physics (Braid, 2006). Moreover, the attention paid to emotional influence on learning is in line with recent studies in brain research which have addressed the “cognitive emotional brain” (Pessoa, 2013). Prior research indicates that our ways of reasoning may not be guided by rationality alone but by complex processes involving both emotional and rational reasoning (e.g., Damasio, 2000).

In this context, we consider narrative medicine and narrative economics models for teaching intervention. We argue, that when used effectively, they may lead to a modification in students’ online search behavior and the increase of their COR skills. As the analysis of students’ responses to the CORA tasks (in section “Analyses of Student Responses”) indicate, students may already have a certain degree of critical reasoning when approaching online source material. We suggest, however, that narrative medicine and narrative economics can serve as “wise interventions” and as a practicable teaching tool in higher education which can substantially enhance students’ COR skills (see section “Implications for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education in the Internet Age”).

Conclusion

Narrative Analysis in Educational and Learning Research

As illustrated, the quantitative analyses of the CORA data and narrative analysis can be mutually complementary. This points to the fact that linking qualitative and quantitative research is essential when it comes to assessing and explaining students’ ability to reason critically in the Internet age. Despite their brevity in short essays, the students’ responses are in fact highly complex, and hence need to be evaluated through both qualitative and quantitative analysis.

As a further step along the way in this development, we may thus want to enhance the qualitative and quantitative research outlined in this article through teaching interventions. How might students be enabled to understand the role of narrative, and even more importantly, the affective impact created by these narratives? Just as Shiller (2017) stresses the role of affect in understanding (and, we would like to add here, in teaching) economic history, affect may also be crucial to consider in one more respect: in the Internet age, students must be able not only to assess, for instance, the trustworthiness of a scientific expert, but also the affective dimension which may accompany the framing of a certain concept or state of affairs by this expert.

In higher education, we should talk to students not only about what sources they use in understanding, for example, certain economic developments, and what they think about the trustworthiness of the sources, but should also teach them to understand how, on the level of narrative structure, these sources “work” and how they shape students’ reasoning about a particular subject. By retracing their own reasoning and decision-making process with tools based on the methodologies of narrative economics and narrative medicine, students can enter into a dialog with themselves, as if interrogating an alter ego, about the impact of these sources on their own thinking, and the reasons for this impact (e.g., Sánchez-Martí et al., 2018). Instructional interventions of this kind can be developed by linking qualitative narrative and quantitative empirical research (see section “Methods and Analysis”).

In the course of an instructional intervention using the narrative analysis, students can then reflect on their attitude to a given source both before and after using narrative research as a tool to unpack how the argument of a given source “worked.” Thus, even prior to actually reading the article on assisted suicide, they may have said that the Süddeutsche Zeitung is certainly a reliable and credible source of information. After conducting a narrative analysis of the article they used, however, they may understand that the article might nonetheless steer their attention in a given direction and could have its own agenda. Understanding such an agenda may be more relevant than ever given the recent scandal of the German news magazine Spiegel. In November 2018, it turned out that Spiegel, widely credited as one of Germany’s major news magazines, had been duped by a journalist who had been fabricating his data for years. In this way and because of narrative research as a method for understanding both, for instance, economic data and its underlying narratives, students are no longer at the mercy of the sources but can enter into a dialog with them. In fact, one of the students’ responses discussed above indicated his understanding of precisely this dilemma.

The preliminary qualitative analysis presented here suggests that an investigation of students’ online search behavior is actually highly complex. How do we begin to tackle this complexity? What happens once students delve deeper into alternative sources? Do they understand that some of these other “experts” have an authority in the debate that may equal or even surpass that of the professor of philosophy whose opinion shapes the Süddeutsche Zeitung article? Here, a follow-up empirical study (discussed below) might be conceived of in which students do not search the Internet randomly looking for additional information and in which their search is instead guided by the parameters established in a previous narrative analysis of the original source.

Limitations and Future Perspectives

There is one particular aspect which this article has addressed in the context of the methodologies of narrative medicine and narrative economics: it related this qualitative methodology to empirical quantitative research and to instructional interventions to promote students’ COR skills in higher education in the Internet age. In this context, the CORA tasks were designed to assess students’ skills in critically evaluating online sources and reasoning using evidence on contentious issues (Nagel et al., 2020).

Being a newly emerging research field, however, narrative medicine and narrative economics as methodologies have not yet been related to empirical research. In this article, we have proposed that this linkage between empirical research and the methodology of narrative analysis involves the following aspects in particular: it is essential to link the idea of students’ COR to the concept of narrative medicine and narrative economics. If indeed, as Shiller (2017) proposes for instance, knowledge in economics is generated through narratives, then narratives can be potentially misleading. They can provide false “leads,” or they can even manipulate students into subscribing to certain theories. This may particularly be the case in the Internet age. This article also related the latter aspect to student learning in higher education. It has thus established a link between narrative medicine and economics, student learning in an online environment, and students’ COR skills.

In particular, we propose to link narrative medicine as a teaching methodology to Walton’s concept of “wise intervention.” So far, the relevance of narrative medicine for students’ information-seeking behavior and critical reasoning has not been empirically analyzed. Practitioners of narrative medicine have only argued that, after a narrative medicine intervention, students will approach the clinical setting in a new way (Arntfeld et al., 2013). Going beyond this approach, we want to explore how narrative medicine can change students’ online information-seeking behavior, their reasoning and their decision-making, taking into account both content and narrative framing of the information they use. We hypothesize that since narrative medicine enhances students’ understanding of the multi-perspective nature of a given medical problem (e.g., all the factors and information that must be considered in diagnosing and treating Alzheimer’s disease), their advanced information-seeking behavior – after the intervention – will mirror this understanding. For instance, students may not stop searching after they have located the definition of Alzheimer’s disease on Wikipedia, but will continue to search, for instance for patients’ experiences or the relationship between Alzheimer’s and the social environment, and to evaluate and critically reflect on the different pieces of information. In terms of economics, a similar process of a more critical information-seeking behavior may result from the use of narrative economics as a model for teaching economics, which may potentially be transferred to other domains (e.g., sociology).

Based on our results presented here, we suggest that we are only at the beginning of a new universe of research which is only beginning to take shape. In future research, it is essential not only to study the role of narratives for the acquisition of domain-specific knowledge in economics or medicine, but also to anchor such narrative research in domain-specific teaching and learning per se. Thus, narrative scholars have to collaborate with researchers and instructors from the respective domains. These latter experts also need to act as “fact checkers”: while knowledge may be narratively constructed, we still have to subscribe to the idea of a verifiable and warranted knowledge base in a given domain. Despite narrative variation, for instance economists will then generally agree on the veracity of a certain idea. For education research at a university level, it is essential that we do not jettison the belief in domain-specific knowledge. Rather, the relationship between domain-specific knowledge on the one hand and “narrative knowledge” on the other is at stake. Students hence need to be equipped with certain skills, COR being the most important among them. It is to the assessment of students’ COR skills in the Internet age that this article has sought to contribute by linking narratives and certain domains in the field of higher education research.

As a future perspective, the findings about narrative knowledge in one domain (e.g., economics) need to be mapped onto another domain (e.g., medicine). Research of this kind seems highly promising, as outlined in this article. In this context, one gap in narrative medicine may be discerned: while narrative medicine has already been fruitfully linked to the didactics of medicine, few studies have empirically tested narrative medicine interventions in the medical classroom and their impact on students’ learning (e.g., McAllister, 2015). For further investigation of narrative medicine in this context, two steps are required: first, narrative medicine must be reconceptualized with regard to concepts such as “deeper learning” (Pellegrino and Hilton, 2012). Through this reconceptualization, narrative medicine would be linked to both education and learning research, which has not been the case so far. Second, empirical studies should be conducted, which would again combine qualitative and quantitative research, focusing for instance on the condition of dementia as it is currently being taught in the biomedical classroom. An empirical study similar to CORA here would gauge the way in which students’ understanding of dementia is shaped by narrative, and would give medical students the task of defining dementia through the use of Internet sources. Through short questions and essay answers, researchers could assess students’ ability to critically evaluate information about dementia, from its biomedical definition to its societal and ethical challenges.