- 1Artificial Intelligence and Human Languages Lab, Beijing Foreign Studies University, Beijing, China

- 2School of Applied English Studies, Shandong University of Finance and Economics, Jinan, China

- 3School of College English Teaching, Zaozhuang University, Zaozhuang, China

- 4School of International Organization, Beijing Foreign Studies University, Beijing, China

- 5Research Bases for the Humanities and Social Sciences, Sichuan International Studies University, Chongqing, China

In recent years, due to the concern of the high rate of burnout and attrition of teachers in their early career years, teacher resilience has become a vital theme in the study of their professional development. However, little has been done in China. This study contextualized teacher resilience development in Chinese universities and interviewed seven resilient novice foreign language (FL) teachers to explore risk factors confronting them in Chinese contexts and resilience strategies they have employed to cope with these challenges. In-depth interview data and informants' reflective journals were analyzed inductively by using thematic analysis. The results of the study unfolded risk factors peculiar to Chinese context, and novices' adoption of resilience strategies was found to involve teachers' highly selective and dynamic interaction with risk and protective factors, and individual agency manifested itself as an important factor in novice FL teacher resilience development.

Introduction

Teachers' job burnout and attrition have become a serious problem confronting almost every school in many countries. Studies conducted by Chinese scholars also manifest that college teachers generally experience the mild or medium level of burnout (Xu, 2010; Tang, 2011; Jiang, 2019), which would definitely assert negative influence on “teaching well” and accordingly disrupt students' learning and achievement (Gu, 2021, p. vii). This alarming regularity would weaken teachers' passion, commitment, and morale on a large scale. As a consequence, students are at risk as to whether they can be entitled to the best teaching, which should be persistent, professionally adept, and passionate. In order to cope with the intractable issue, the study of teacher resilience was initiated at the turn of the twenty-first century (Bobek, 2002), and it was motivated by the concern of the high rate of burnout and attrition of teachers in the first 3 years of their teaching career (Tait, 2005; Intrator, 2006). Rather than focus on those who dropped out or lost commitment to teaching, more attention was shifted to the study of those who were not only surviving but also thriving (Beltman et al., 2011) in their teaching career in face of great challenges and complex circumstances.

As a psychological term, resilience is commonly defined as the ability to “bounce back” or recover after exposure to stress or traumatic experiences (Sammons et al., 2007). The study of psychological resilience originated as an intervention for children who developed negative behaviors like drug abuse, alcohol abuse, or mental disorders after exposure to serious risk hazards (Rutter, 1999, p. 159). As a newly emerging field of investigation, teacher resilience is still a loosely and broadly defined term. Some scholars regard it as an individual attribute and define it as teachers' quality (Brunetti, 2006, p. 813) or capacity (Oswald et al., 2003, p. 50) to “bounce back” in the face of potential risks; others view it as an outcome of “using energy productively… in the face of adverse conditions” (Patterson et al., 2004, p. 3). However, the recent years have witnessed more recognition that resilience is not an “innate” quality (Cohler, 1987, p. 395) of individuals that stays static through one's life. Social, environmental, and cultural contexts are found to play important roles in developing or shaping psychological resilience (Richardson et al., 1990; Beltman et al., 2011). Resilience, accordingly, is gradually recognized as a dynamic process that involves individuals' active interaction and negotiation with the environment (Tait, 2008). Day and Gu (2014) have further broadened the concept of resilience and believe resilience is “more than bouncing back,” and teacher resilience is the positive adaptation to the uncertainties in workplace; it is dynamic, relational, and developmental. This study would adopt Day and Gu's (2014) concept of teacher resilience and highlight how resilience is developed and how individual agency counts in novice college foreign language (FL) teachers' positive response to challenges in their induction. The study of teacher resilience relies heavily on the resilience theories in the field of psychology. Along with the abundant research on teacher resilience from different perspectives, researchers have developed a number of resilience models to account for the findings in this field. Richardson et al. (1990) resiliency model depicts the process as a psychological reintegration. It is the ability to learn new strategies or tactics from disruptive or traumatic experiences and resume the balance in a way that will strengthen the power to negotiate life events. The premise of the model is that in order to become more resilient, an individual's former organized state must be broken by challenges, stressors, and risks. Then the individual struggles his or her way to reorganize life and recover from the disruptive experiences. After this process, he or she would become more adept with suitable coping strategies and protective factors (Richardson et al., 1990). It is a process that leads to the homeostatic reintegration after the interaction between the stressors or challenges with biopsychospiritual protective factors (Richardson et al., 1990). In a similar vein, Jordan's relational resilience model emphasizes that “resilience should be seen as a relational dynamic” (Jordan, 1992, p. 11). In her later studies, Jordan (2012) argues that although risks in dysfunctional environment would impede the natural flow of disconnection-connection, human brains' strong ability to adjust can help people rebuild the links with healthy connections, establish more reliable attachment, and, through this, “begin to shift underlying patterns of isolation and immobilization” (Jordan, 2012, p. 74). The two models both indicate that resilience is not an inborn capacity that remains static during one's life time. Social, environmental, and cultural contexts are found to play important roles in developing or shaping psychological resilience (Richardson et al., 1990; Beltman et al., 2011). Therefore, the two models resonate with each other in terms of regarding resilience as a dynamic and interactive process that can resume and promote the well-organized situation with the help of protective factors. Individuals' active interaction and negotiation with the environment (Tait, 2008) are recognized. Johnson (2002, p. 226) has stressed, “resilience changes with time, circumstances and context.” Both the immediate contexts that teachers are in and the historical, political, social, and cultural contexts will exert influence on teachers' beliefs, values, and behaviors.

Resilience presumes the existence of risk factors. Previous studies have examined the personal and contextual risk factors confronting novice teachers in a western context. On the individual level, the lack of experience and confidence (e.g., Day, 2008), disillusion from mismatch between teaching vision and the realities of the job (e.g., McCormack and Gore, 2008), and a sense of isolation or alienation (e.g., McIntyre, 2003) were consistently reported. On the contextual level, the following risk factors are commonly recognized in western context: difficult courses or classes assigned, heavy workload, classroom management or discipline, inadequate support from mentors or administrative leaders, unfamiliarity with the colleagues and non-rapport relationship with students, insufficient resources or equipment, and institutional supervision and evaluation of their teaching (e.g., Gordon and Maxey, 2000; McIntyre, 2003; Tait, 2008).

Factors that mitigate the effect of risks were called protective factors (Kaplan, 2002, p. 46), which were revealed to be centered on personal and conditional levels (Castro et al., 2010, p. 623). Individual protective factors such as altruistic motives, intrinsic motivation, sense of self-efficacy, individual personalities, teaching and coping skills, and professional reflection (e.g., Gu and Day, 2007; Sinclair, 2008; Le Cornu, 2009) and contextual protective factors such as interpersonal relationships, school or administrative support, and pre-service program support were shown to be beneficial to the promotion of resilience (e.g., Howard and Johnson, 2004; Gu and Day, 2007; Olsen and Anderson, 2007).

Undoubtedly, investigating the protective factors is important, as they are helpful for resilience development. Having protective factors does not entail that they will function automatically in facilitating the building of psychological resilience. Issues about how and under what circumstances they will function would largely depend on how individuals actively utilize and integrate these factors in making them functional. However, few studies have mentioned the important role of teachers as active agents (Beltman et al., 2011) to integrate the risk and protective factors in promoting resilience. In the past decades, researchers have conducted studies on teacher resilience (Gu and Day, 2007, 2013; Beltman et al., 2011; Day and Gu, 2014; Mansfield et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2016; Wosnitza et al., 2018) and the strategies they employed to cope with the challenges (Patterson et al., 2004; Castro et al., 2010). Patterson et al. (2004) made a static description of four strategies that would be favorable to resilience development, namely making decisions under the guidance of personal values, emphasizing professional development, taking initiatives to contribute to their community, and solving problems.

Although the dynamic view of resilience has been long adopted in the study of children and adolescents, the study on teacher resilience is still in its infancy and the majority of the research remains their focus on the description of static risk and protective factors, and even some almost equate resilience studies with exploration of protective factors (Kumpfer, 2002, p. 182), and very few have gone beyond and searched for the process underlying the resilience development. Although the dynamic and developmental nature of teacher resilience has been commonly accepted, studies adopting this view and analyzing how teachers negotiate with the environment are comparatively sparse. Castro et al. (2010) revealed four strategies that beginning teachers of primary and elementary schools employed to cope with the hardships they encountered in high-need areas and in special education in United States. Beutel et al. (2019) explored a cohort of pre-service teachers' personal and contextual resources and how they utilized strategies to activate resilience in eastern Australia.

The overview of previous studies on teacher resilience reveals that almost all of the studies were carried out in Western contexts, and scattered studies have adopted strategy-oriented perspective; thus, there is an urgent need to carry out more empirical studies to offer insights into how individuals develop their resilience. To our knowledge, no study to date has investigated the risk factors and how social and cultural contexts affect Chinese novice FL teachers' development of resilience in colleges and universities. By revealing how novice FL teachers actively and selectively employ strategies to overcome adversities, this study aims to highlight the agency that novice teachers demonstrate in resilience development. With the huge population of novice teachers as well as the educational backgrounds and policies peculiar to China, it would be more meaningful to gain insights into the trajectories of teacher resilience in this country. A deep exploration on risk factors Chinese novice teachers are confronted with and how they develop resilience to cope with them may yield different findings and offer new insights into the nature of teacher resilience.

In view of the research gaps mentioned above, this study selected seven resilient novice FL teachers in China as participants to reveal the process of resilience development of Chinese novice FL teachers. It aims to explore the risk factors novice college FL teachers encountered in Chinese contexts and how they developed strategies to cope with the challenges. It is hoped that the findings of this research will enhance novices' adaptability in their induction, help sustain their commitment to the teaching profession in China, and at the same time offer implications for teacher education and national policy development concerning FL teaching and learning. Specifically, two research questions will be addressed in this study.

(1) What risk factors will novice college FL teachers be confronted with in the Chinese contexts?

(2) What resilience strategies will Chinese novice college FL teachers adopt to meet the challenges?

Methods

Participants

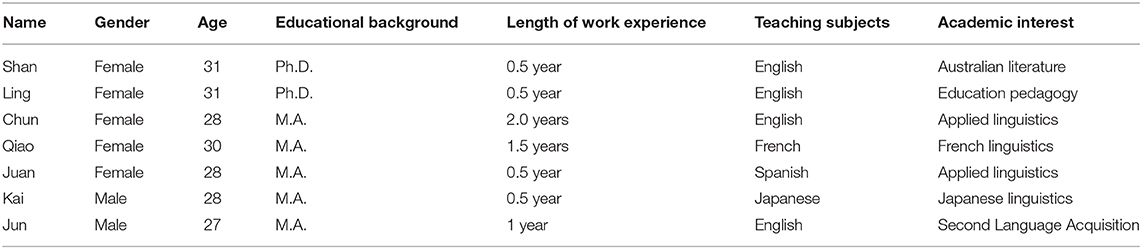

This study adopted purposeful sampling. Two criteria guided the selection of the participants: (1) the teachers worked in the university within their first 3 years; (2) in spite of adversities, the teachers made above average achievements in both teaching and researching. Novices' teaching quality was measured by both the student evaluation and supervisor evaluation, and novices' achievement in research was judged by their published papers and their enthusiasm in doing research, such as their engagement in academic activities. Hence, seven resilient novice teachers with work experience ranging from 6 months to 2 years were selected as qualified participants, and they all agreed to participate in this study. Among them two were males and five were females, and two of them had received their doctoral degrees and five master's degrees. Written informed consent was obtained from all of them, and the study was approved by the ethics board of Artificial Intelligence and Human Languages Lab in Beijing Foreign Studies University.

To triangulate, Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD—RISC) (2003) was adopted and translated into Chinese. The Resilience Scale consists of 25 items, and each item was rated on a 5-point scale (0–4), with the total score 100 and higher scores reflecting greater resilience. The Cronbach alpha coefficient of the scale was 0.89 and the test-retest reliability coefficient was found to be 0.87 (Connor and Davidson, 2003). The seven novice teachers were required to complete the questionnaire and the result demonstrated that all of them were above 85 points, indicating they were all resilient teachers. The informants' profiles are shown in Table 1.

Data Collection

In-depth interview was adopted as the main method. The interview was semi-structured, conducted by two of the researchers adhering to the following procedures. First, the interviewers explained their interest in novice teachers' development in general. Next, the following guiding questions were asked for interviewees to elaborate on: (1) What difficulties have you encountered since you became a college FL teacher? Such as difficulties from yourself, your family, teaching, research, relationship, etc. (2) What have you done to cope with the challenges, and what turned to be effective ways that you kept adopting in similar circumstances? (3) Since your induction, have you felt any changes, for example, in your teaching techniques, research ability, relationship with your students, colleagues and leaders of your department, your expectation, self-confidence and self-positioning, etc.?

Informants were interviewed one by one and each interview lasted from one to one and a half hours. Follow-up interviews were conducted by the same interviewers to clarify interviewees' understanding and complement materials necessary for research questions.

In addition to the data from the interview, reflective journals kept by five of the informants since their induction (Chun, Kai, Qiao, Shan, and Jun) also contributed to addressing the above research questions. In the journals, they recorded the “reality shock” (Veenman, 1984, p. 143) they experienced, the struggle they have made, and the ways they have found to help them tide over, so their journals are enlightening for researchers to trace how they negotiated with the new environment and how they developed their resilience. These five informants all showed willingness to share their journals for this research.

Data Analysis

The interviews were recorded with the permission of the informants. The recordings were first transcribed by the interviewers, and then checked for accuracy by the interviewees and finally coded by two researchers.

Two researchers first read through the interview and reflective journal data to obtain a general sense of the data. The data in this study was approached in an inductive way. We first began with open coding and found the recurring categories and themes in the data. Participants were asked to confirm whether these categories and themes were meaningful to them in the follow-up interview. Those confirmed meaningful were maintained, and those questionable were further discussed and negotiated by the researchers and the participants until finally all were determined. Representative extracts were carefully selected to offer evidence for each category and theme.

Findings and Discussion

An analysis of the data from the interview and informants' reflective journals yields the following results. For the first research question, four categories of risk factors were recognized, and they were challenges from individual, classroom, institution, and national reform policy concerning FL teaching and learning; all were found to be deeply rooted in Chinese context. For the second research question, four themes emerged as effective resilience strategies to ease novices' challenges in their induction, and they were listed as perceiving risks as opportunities, taking initiatives to motivate students, seeking help from social network, and keeping professional learning. Resilience was found not as a static trait of individuals but in the constant negotiation of the individuals with their inner world and the outside world. Detailed analysis of the results is as follows.

Peculiar Risk Factors Confronting Novice FL Teachers in Chinese Context

Data analysis sorted the risk factors confronting Chinese novice FL teachers into four sources: individual, classroom, institution, and national reform policy concerning FL teaching and learning, and found these challenges did pose threats to their status quo and temporarily disrupted their world views (see Richardson et al., 1990).

Individual Risk Factors

Emotional states such as being “unsure,” “uncertain,” “nervous,” “worried” were frequently reported by the informants. Totally new experience, unfamiliarity with the students, and suddenly changed the role as a teacher as mentioned by Jia, Li, and Chang all contributed to their “reality shock” (see Veenman, 1984, p. 143) and caused anxiety and insecurity (Giovanelli, 2015).

Feelings of isolation as reported by McIntyre (2003) also surfaced from the interview data; this negative feeling was especially emphasized by teachers with little institutional support (Kai, Chun, Qiao, and Jun).

There are very few collective activities in our department. After 6 months, I have not been familiar with my colleagues. There is nobody to turn for help and nobody to talk with, and I seem to have been alienated. (Kai, interview)

In contrast, novices working in a supporting environment seemed to be free from this negative emotion (Shan, Juan, and Ling), which seems to indicate caring organizational setting helps in novices' adaptation to their new life events.

We have a teaching and research community in our department for lesson preparation, and a veteran teacher was specially assigned to assist me in my teaching practice, so very soon I integrated into the big family. (Juan, interview)

Another source of challenge for novice FL teachers was found to be linked to their foreign language teaching contexts and their non-native speaker identity (Medgyes, 1992; Liu, 1999). As non-native language teachers, they worried about their qualifications in language proficiency (Juan and Chun), authenticity of linguistic expressions (Kai and Qiao), lack of experience in the target culture (Kai, Chun, Juan, and Qiao Li, Chang, Jia, and Qian) and even their pronunciation (Chun and Jun). Compared with native speakers of FL teachers, non-native FL teachers seem to have much more to do to be qualified as a language teacher.

Classroom Challenges

Working in a foreign language context, all novice FL teachers reported the challenges to motivate students to learn a foreign language and to organize and present teaching materials in accordance with the diverse interests and abilities of learners. Shan mentioned students' lack of interest in learning a foreign language, Jun revealed students' unwillingness to participate in class activities, and Kai felt helpless when confronting students' silence in his language class.

FL learners' lack of intrinsic motivation may be directly linked to the FL learning context. Different from the second language learning context, foreign languages are not vital for Chinese students' survival, and communication activities are not natural but contrived. Therefore, most Chinese FL learners learn a FL with an instrumental motivation (Zhou and Gao, 2009) and are mostly examination-oriented (Gu and Li, 2013).

Chinese students' strong sense of “face” is another factor worsening the classroom atmosphere. As a strategy to avoid losing face (Ha and Li, 2012), Chinese students prefer to “play safe” and appear to be silent and inactive in class activities.

Furthermore, huge population coupled with shortage of language faculties make FL class a large size in China. Too many students in one class (about 100 students in Kai's and Chun's and about 150 students in Jun's class) would incur great trouble for teachers to get the students effectively involved in classroom activities.

The large class size actually made me strained at first, I could hardly guarantee everyone could stay focused…It is not realistic for me to check their homework one by one and the limited time in class can only possibly allow two or three groups to demonstrate their presentations. (Chun, interview)

Along with the challenges from large-class teaching come students' diversified demands and uneven proficiency levels.

In my class, there is uneven distribution of proficiency levels. Some have reached the advanced levels and complained what I taught was too simple, while some others could not even catch up with my teaching. It is really hard to satisfy every student's need. (Juan, interview)

Institutional Challenges

This study shows that heavy workload, lack of institutional support in teaching and academic research, and research evaluation constitute the major institutional challenges confronting novice college FL teachers.

Heavy workload originated from the lack of teacher resources in China. As a country with the hugest population, China has the largest number of students to teach. However, teachers seem to be always in short supply. Heavy teaching and non-teaching workload, consequently, was assigned to novice foreign language teachers. Too heavy workload was reported to have endangered their academic and professional development. For example, Shan had 3 different subjects to teach per week and most of her time was spent on preparing and presenting the lessons, thus leaving her very little time to do research. As the English department was short of hands, Jun, besides shouldering the responsibility as a teacher, was also burdened with trivial and time-consuming office affairs, which even ate into his time preparing for the lessons and he had to burn the midnight oil.

Insufficient teacher resources yielded another result, i.e., novice teachers would be assigned courses that do not match well with their majors. For example, a linguistic major (Juan) may be assigned to teach American Literature, which would cause stresses and anxieties because of her inadequate “content knowledge” (CK) (see Shulman, 1986, p. 9) in the subject field.

Institutional support in teaching and academic research is deemed to be crucial for novice teachers' development (Gu and Day, 2007; Olsen and Anderson, 2007; Fantilli and McDougall, 2009). Collective preparation of lessons was reported to have helped Shan, Ling, and Juan to be better prepared for the lessons. Project teams or research groups have also offered Shan, Ling, and Juan more chances to apply for or join in research projects. By participating in these collective activities, novices get more socialized and the sense of belonging has been gradually fostered.

On the contrary, the lack of support from institutions would leave the teachers, especially novices, in a helpless, alienated, and perplexing condition as was revealed by Chun, Kai, Qiao, and Jun.

As regards to preparing for the new courses, our university does not provide guidance for new teachers in teaching. I have to do it all by myself, which is really confusing, especially at the beginning. (Chun, interview)

Institutional academic supports can also be embodied in opportunities for further development accessible to teachers, such as in-service training programs, academic lectures, research groups, research funds, and supportive policies. The absence of these would worsen the situation of novices and leave them a bleak prospect for their future development.

There is neither research team nor training program available to novice teachers in our department and we need to struggle all by ourselves in academic development. (Kai, reflective journal)

The third challenge from institution is the evaluation and promotion system. Academic research, as a yardstick to evaluate and promote college FL teachers in China, puts all the informants under pressure. While Shan and Ling, who both hold doctorate degrees, mentioned the pressure from publishing papers, and the other five teachers with master's degrees were found to have much more concern about accomplishing the research requirement. For example, both Chun and Qiao mentioned they were totally at a loss about how to do research and publish papers, although they realized the importance of doing research in college. This finding revealed the effect of educational background on the perceived research pressure of the novice FL teachers. Being marginalized when applying for research programs and seeking promotion is another challenge facing novice college FL teachers, especially for those working in universities where foreign language department was marginalized. Qiao, who works as a French teacher in a financial university, complained,

It is unfair to assess us FL teachers in the same way as the teachers whose majors are economy or finance, as the school has laid down policies more favorable to them. (Qiao, reflective journal)

Risk Factors From National Reform Policy

One challenge typically found among Chinese foreign language teachers came from the national reform policy concerning foreign language teaching. With the developments and advances propelled by the reform and opening up policy, multilateral trading between China and the world has experienced unprecedented growth during the past decades. Accordingly, students are expected to have compound abilities both in their English language proficiency and specialized fields. To meet the demand of the market economy, pragmatic orientation in foreign language talents cultivation manifests itself in various aspects. One reform was to reduce English for General Purpose (EGP) courses and make college English optional courses. This has aroused a sense of insecurity among novice FL teachers. As Jun worried:

I have just graduated and settled down with a steady job that I assumed, but it seems no longer as steady as before. I'm likely to be out of work anytime if foreign language teaching reform continues this way. (Jun, reflective journal)

When EGP courses were cut down, more English for Special Purpose (ESP), English for Academic Purpose (EAP), and optional courses catering to students' interest are encouraged to be opened by FL teachers. For example, courses like Financial English, Medical English, and Tourism English have been proposed to be incorporated into the curriculum of college English teaching. While content-based language teaching is highly advocated in colleges, foreign language teachers' CK has not been updated, which leads to their incompetence in teaching the course.

My major is English Education, but one of the courses I had to teach was Business English. To be honest, I really felt confused and upset as I opened the textbook and saw so many business terms, because I didn't know clearly about the actual procedures involved in business transactions. (Chun, interview)

The risks from national reform policy concerning foreign language teaching showed the challenge of globalization in China has set new requirements for universities to cultivate compound and innovative talents. Accordingly, it is necessary for FL teachers to update their knowledge structure, re-position themselves as language teachers, and re-plan their professional development path.

The above analysis reveals “context specific” (Gu, 2017, p. 125) risk factors confronting Chinese novice college FL teachers. The foreign language teaching and learning contexts not only deprive teachers and students of direct exposures to the target language but also reduce students' motivation to learn the language, thus making language teaching more challenging. Chinese students' fear of “losing face” discouraged them from active participation in class activities and worsened the teaching situation for teachers as well. Huge population coupled with lack of FL teacher resources brings about large class size, uneven proficiency levels of students, heavy teaching and non-teaching workload. Chinese reform concerning FL teaching and learning, together with shortage of corresponding support, caused the mismatch between what novices have been trained and what they will have to teach. Apart from challenges from teaching, the requirement in novices' evaluation and promotion constituted an even more disruptive risk factor. All these risk factors brought about unpleasant and stressful experience and temporarily broke the balance of novice FL teachers' life.

Novices as Active Agents to Adopt Resilience Strategies

Informants did not stay in the disorganized situation for long. To address these challenges and reconstruct a new balance, they came up with a variety of strategies. By adopting a strategy orientation, the focus of this study is not only on the exploration of possible protective factors like previous studies (e.g., Bobek, 2002; Le Cornu, 2009). As an extension of prior studies, the study emphasized how the novice FL teachers activated their agency to make use of the existing protective factors and to create favorable conditions when things got tough. Four strategies surfaced from the data to cope with the above risk factors: perceiving risks as opportunities, taking initiatives to motivate students, seeking help from social network, and keeping professional learning.

Perceiving Risks as Opportunities

Confronted with adverse circumstances, novice teachers did not take a pessimistic attitude toward life (Castro et al., 2010). Instead, they viewed these challenges as opportunities for their further growth (Richardson et al., 1990) and actively seek measures to tackle them.

When confronted with the heavy teaching and non-teaching workload, interviewees all demonstrated their optimistic attitude toward and passion for their work. For instance, most of them agreed that they were young and should take on more tasks and conceived the workload as beneficial. For them, more work means more engagement with their surroundings and more chances to get adapted to their new working environment, and hence a quicker transformation of their identity from a student to a teacher. For example, Shan regarded workload as an incentive to inspire her inspiration of academic research:

Every week, I spend much time marking and correcting students' compositions. Time-consuming as it is, I feel really content as I realize my students make progress day by day. What's more, their writings gave me a lot of valuable insights into my research. Their excellent compositions can serve as good samples for the writing course book I plan to compile. (Shan, interview)

Shan's remarks show that she regarded the extra time spent on students' homework as rewarding. Her positive attitude toward the heavy workload helped her find her interest in research—to compile a writing course book suitable for Chinese students. This research interest, in turn, stimulated her enthusiasm for teaching. The same attitude can be found in the interviews with Qiao and Ling, who transformed the heavy workload and the exhausting work state into a conducive process to “make themselves felt” (Qiao, reflective journal) in their new environment and enable them to “be more competent with their teaching” (Ling, interview).

Actively undertaking responsibilities is another example to show novices' positive attitude. Assigned difficult courses, they would not retreat but viewed them as challenges to motivate them to perfect themselves. When it comes to the new course, Chun said:

Although it (Business English) was totally new for me, I didn't hesitate to accept it. I am young and new here, and I'd like to take more challenges. I believe, if I can teach this course well, I can prove my competence and become more confident. (Chun, interview)

For Jun and Kai, they were required to live on campus during the 1st year, which would be tough as they can hardly stay with their family on weekdays. Although they complained a little about the inconvenience, both of them said that the experience brought them unexpected opportunities to get close to students, which helped ease their anxiety in the classroom and adjust their teaching to meet the requirements of the students.

Novices' optimistic attitude and intrinsic passion for teaching career act as a buffer, helping them transform the negative emotions to motivation and generate positive outcomes. After this transformation, they all got increasingly accustomed to their career, which constitutes a more favorable environment in promoting their further development.

Taking Initiatives to Motivate Students

Taking initiatives to motivate students is a direct way to show how novice teachers' agency is at work. Teaching in the FL context, teachers need to make more efforts to arouse students' interest and encourage their engagement in classroom activities. For example, Kai intentionally created opportunities to communicate with students to better understand them so as to achieve better cooperation and communication in the classroom:

When I lived on campus, I often purposefully had meals with my students. During the talk, we gradually got familiar with each other. I knew a lot about their interests, their worries and even the reasons for their reluctance to answer questions in class. (Kai, interview)

With a better understanding of his students, Kai redesigned his lessons and adjusted the teaching tempo, and finally it turned out that his students became more active in class.

Confronting the uneven language proficiency levels of the students, Juan did not let it be, but took active measures to help those who lagged behind:

After the mid-term exam, I found two of them did worse than the average apparently. Instead of scolding them, I recalled their performance in class and went through their test papers again, and found out the reasons. Then I had a long talk with them and finally worked out a feasible means to help them make progress in this course. (Juan, interview)

Unpredictable incidences may arise anytime in class, which constitute great challenges for novices and call for their quick-minded reactions. Ling once mentioned her experience of solving an embarrassing situation during the process of organizing an oral English activity:

As I told them to prepare for the lecture through discussion in class, they seemed to be a little bit passive. I guessed that may result from the choices of partners. Then I encouraged them, “It is a good chance to have a talk with someone if you happen to have affection. Don't hesitate to stand up and get close to him or her.” Upon my suggestion, the class smiled and they stood up to find their partners and soon got themselves actively involved in the discussion. (Ling, interview)

With her humor, Ling created a relaxing atmosphere, broke the ice, and successfully engaged students in the teaching activities.

Classroom practice may challenge novices in different ways, such as students' disbelief in teachers (Kai), their disinterest in the assigned tasks (Ling), and the uneven proficiency levels of students (Juan). In tackling these problems, novice FL teachers exhibited their flexibility and selectivity by resorting to internal resources like their caring for students (Juan and Kai) and humor (Ling) or external resources like the support from the institution (Juan) and individual social network (Kai). The initiatives they take not only complemented their inadequacy in CK and pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) but also helped them find effective measures to handle difficulties in teaching.

Seeking Help From Social Network

Seeking help from social network has been found to be a very important way to help novices (Castro et al., 2010). However, novices were revealed to differ in their priority when it comes to which social network to turn to. The network resources that novices resorted to in this study were found to include the existing institutional support and the network constructed by the individuals. The existing institutional teaching and research supports were the primary choice for the novice FL teachers to seek help. During the interview, Juan and Ling both mentioned:

We have a specialized teaching and academic research group and we meet and discuss regularly. For us novice teachers, our group would help us clarify and specify the teaching content, objectives and procedures. (Juan and Ling, interview)

This supportive help from the institution not only provided guidance for the teaching staff and guaranteed their teaching quality, but also encouraged the novice teachers to get socialized into the group more quickly. These two teachers both admitted this helpful routine actually provide them with a sense of safety and belonging, as well as warmth, which quickened their adaptation to the new environment in a more natural and reassured way.

When the institutional support assisted Juan and Ling a lot, it did no good to Shen, who worked in the same university as Juan. Although an academic research team has been established to encourage cooperation in academic research, Shan insisted on doing research by herself rather than relying on the existing team. And she explained as follows:

I don't like involving myself in complex interpersonal relationships in cooperation with others and I prefer to do research by myself. It is my personal habit for years. (Shan, interview)

Shan's case demonstrated clearly the availability of institutional support does not mean it will function in individuals' negotiation with the environment. Novice teachers are highly selective in availing of the existing support.

When support for teaching and academic research was bleak, the novice teachers strove for ways out and constructed their own supportive network. For example, Chun chose to turn to her husband working in a foreign trade corporation for some help in her teaching of Business English, and Ling would fall back on foreign teachers in her department to clarify some language confusions. To gain research help, Qiao and Kai would consult their former classmates and former tutors.

Seeking help from social network reveals the importance of relations in resilience development (Le Cornu, 2013; Papatraianou and Le Cornu, 2014). What is more striking, this study demonstrated that contextual and personal factors influenced individuals' selection of external relations in adapting to the environments. For example, Juan and Ling relied heavily on the existing supportive network in their preparation for lessons and in solving difficult problems. However, for those without much support from the institution like Kai, Chun, Qiao, and Jun, individuals' initiatives were most employed to construct their own network favorable to tackle challenges. In this sense, resilient teachers are not only users of protective factors but also active builders of protective factors (Castro et al., 2010).

Shan's preference for relying on herself in doing research despite the existence of external academic groups also reflects that individuals are highly selective in using protective factors and the existence of protective factors should not be equated with resilience development (see Kumpfer, 2002, p. 182).

Keeping Professional Learning

Aware of the discrepancy between their knowledge storage and the requirement in their career, novice teachers positively chose to keep professional learning. Continuous professional learning in CK, PCK, and academic research was the key for them to improve their performance in teaching as well as in research. To be a qualified teacher, Qiao and Chun were eager to equip themselves with relevant knowledge necessary for teaching practice.

I spent much time preparing for my course (a specialized course for seniors), consulting reference books and surfing the internet to get deeper understanding. (Qiao, interview)

Novice FL teachers not only take up professional learning in their preparation for lessons, but also other opportunities for their further development. Applying to be a visiting scholar abroad (Shan), studying abroad (Juan), and attending international academic conferences (Kai), to some extent, made up for their inadequacy in first-hand target culture experience. Attending academic seminars and lectures (Chun and Jun) helped them keep academically active in mind.

To gain personal experience of the target culture, I went on a study tour to America at my own expense. The month abroad deepened my understanding about American culture, broadened my vision and promoted my confidence as a teacher of English. (Juan, interview)

Attending lectures offers me good chances to get to know some renowned scholars and have a talk with them about my confusions in teaching and research. I can get some enlightenment and encouragement. (Jun, reflective journal)

In their continuous learning they gained more control and ease in classroom management. Through professional learning, they also expanded their vision and laid solid foundation for their research. This active adaptation empowered novice teachers to be more competent (Ruohotie-Lyhty, 2013) and showed the significant role of individual's autonomy (Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2014) in helping teachers better adapt to risky environments.

To summarize, in face of the risk factors, novice FL teachers showed strong agency to actively adapt to the adverse circumstances. Perceiving pressures as opportunities is an attribute that motivated novice FL teachers to solve problems; motivating students' classroom engagement bettered their teaching effectiveness; seeking help showed their active reliance on possible resources; and keeping professional learning alleviated their pressure from the feeling of inadequacy.

The employment of all these four strategies manifested the process-oriented view of resilience (Richardson et al., 1990) and showed how individuals, as active agents, integrated the internal and external protective factors to respond to challenges. Challenges from personal and contextual factors disrupted the homeostasis (Richardson et al., 1990) of the novice teachers, but at the same time offered opportunities for their development of better adaptive abilities. Facing the disorganization, novice teachers' optimistic attitude (perceiving risks as opportunities) and their effective measures (taking initiatives, seeking help, and keeping learning) contributed to their formation of new balance for their life. During this process, their coping skills were enhanced, and adaptability to the environment was fostered, which alleviated their pressure in future encounters with similar risks. It is in this sense that stress or adversity is not an inhibitor in the traditional sense, but has become something positive and beneficial for personal development if perceived and managed well by individuals.

Conclusion

The findings of this study can be summarized as follows. First, risk factors were revealed to be context dependent and challenges confronting Chinese novices could only be interpreted when Chinese contexts were borne in mind. Second, resilience was found not to be a static trait of individuals, but was dynamically developed in the individuals' negotiation with their internal and external world. Third, the adoption of resilience strategies was highly selective and novice teachers' attitude toward stressors, their autonomy, agency, and perseverance in tackling the challenges were found to play significant roles in fostering their resilience. Fourth, when well-managed, risk factors would be the prelude for more resilient and capable individuals, and thus should be viewed positively.

Findings from this study could offer implications for teacher education and national policy development. For individuals, novice college FL teachers should hold an optimistic attitude and view stressors as facilitators rather than as inhibitors for their development, and actively integrate the internal and external resources to respond to life challenges, which would not only promote their resilience but also speed up their transition from a novice to a competent teacher. For institutions, administrators can draw insights from this study and offer substantial support for novice teachers, such as incorporating resilience training into pre-service teacher education, providing novices adequate teaching resources, offering them guidance and positive feedback, and building teaching and research project community. All these measures would assist novices' socialization and their becoming full-fledged members of the community. For national policy makers, when more ESP, EAP, and other content-based courses are incorporated into the curriculum, teacher training programs should also be ready to update and reconstruct the knowledge structure of foreign language teachers, so they will get better prepared to adapt to the reforms and guarantee their teaching effectiveness. It is hoped that resilience strategies would not only help teachers survive their teaching profession but also sustain their passion and love for the career, and in this way, teachers would be well-retained in China.

Revealing as this study is, there is no lack of limitations, which, in turn, would open new avenues for future research. First, the trajectories of novice college FL teacher resilience development were mainly a retrospective inquiry in this study, and it is suggested that longitudinal studies should be carried out in the future to unfold a more dynamic picture. Second, most studies, including this one, mainly focused on resilience development of novice teachers. Actually, how resilience works for experienced teachers would turn out to be equally important in helping teachers avoid burnout and maintain their passion and commitment to teaching.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be available on request to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the ethics board of Artificial Intelligence and Human Languages Lab in Beijing Foreign Studies University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

LF and L-nW made substantial contributions to conception, design, and data acquisition of the study. FM and Y-mL collected and analyzed the data as well as drafted the manuscript. TL and LG revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the First-class Disciplines Project of Beijing Foreign Studies University (2020SYLZDXM040) and Humanities and Social Science Project of Shandong Provincial Universities and Colleges (J18RA258) and Social Science Project of Shandong Province (18CWZJ53).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Beltman, S., Mansfield, C., and Price, A. (2011). Thriving not just surviving: a review of research on teacher resilience. Educ. Res. Rev. 6, 185–207. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2011.09.001

Beutel, D., Crosswell, L., and Broadley, T. (2019). Teaching as a “take-home” job: understanding resilience strategies and resources for career change pre-service teachers. Austr. Educ. Res. 46, 607–620. doi: 10.1007/s13384-019-00327-1

Bobek, B. L. (2002). Teacher resiliency: a key to career longevity. Clearing House 75, 202–205. doi: 10.1080/00098650209604932

Brunetti, G. J. (2006). Resilience under fire: perspectives on the work of experienced, inner city high school teachers in the United States, Teach. Teacher Educ. 22, 812–825. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2006.04.027

Castro, A. J., Kelly, J., and Shih, M. (2010). Resilience strategies for new teachers in high-needs areas, Teac. Teacher Educ. 26, 622–629. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.09.010

Cohler, B. J. (1987). “Adversity, resilience, and the study of lives”, in The Invulnerable Child, eds E. J. Anthony, and B. Cohler (New York, NY: Guilford), 363–424.

Connor, K. M., and Davidson, J. R. T. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depression Anxiety 18, 76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113

Day, C. (2008). Committed for life? Variations in teachers' work, lives and effectiveness. J. Educ. Change 9, 243–260. doi: 10.1007/s10833-007-9054-6

Day, C., and Gu, Q. (2014). Resilient Teachers, Resilient Schools: Building and Sustaining Quality in Testing Times. London, UK: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203578490

Fantilli, R. D., and McDougall, D. E. (2009). A study of novice teachers: challenges and supports in the first years. Teach. Teacher Educ. 25, 814–825. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.02.021

Giovanelli, M. (2015). Becoming an English language teacher: linguistic knowledge, anxieties and the shifting sense of identity. Lang. Educ. 29, 416–429. doi: 10.1080/09500782.2015.1031677

Gordon, S. P., and Maxey, S. (2000). How to Help Beginning Teachers Succeed, 2nd Edn. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Gu, Q. (2017). “Resilient teachers, resilient schools: building and sustaining quality in testing times,” in Quality of Teacher Education and Learning: Theory and Practice, eds X. Zhu, A. Goodwin, and H. Zhang (Singapore: Springer), 119–143. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-3549-4_8

Gu, Q. (2021). “Foreward” in Cultivating Teacher Resilience: International Approaches, Applications and Impact. ed C. F. Mansfield (Singapore: Springer International Publishing), vii–ix.

Gu, Q., and Day, C. (2007). Teachers' resilience: a necessary condition for effectiveness, Teach. Teacher Educ. 23, 1302–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2006.06.006

Gu, Q., and Day, C. (2013). Challenges to teacher resilience: conditions count. Br. Educ. Res. J. 39, 22e44. doi: 10.1080/01411926.2011.623152

Gu, Q., and Li, Q. (2013). Sustaining resilience in times of change: stories from Chinese teachers. Asia Pacif. J. Teacher Educ. 41, 288–303. doi: 10.1080/1359866X.2013.809056

Ha, P. L., and Li, B. (2012). Silence as right, choice, resistance and strategy among Chinese “Me Generation” students: implications for pedagogy. Discourse 35, 233–248. doi: 10.1080/01596306.2012.745733

Howard, S., and Johnson, B. (2004). Resilient teachers: resisting stress and burnout. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 7, 399–420. doi: 10.1007/s11218-004-0975-0

Intrator, S. (2006). Beginning teachers and the emotional drama of the classroom. J. Teacher Educ. 57, 232–239. doi: 10.1177/0022487105285890

Jiang, X. Y. (2019). A review of the research on the job burnout of Chinese college English teachers and its implications. Foreign Lang. World 92, 76–84.

Johnson, B., Down, B., Cornu, R., Peters, J., Sullivan, A., Pearce, J., et al. (2016). Promoting Early Career Teacher Resilience. New York, London, UK: Routledge.

Johnson, J. L. (2002). “Resilience as transactional equilibrium,” in Resilience and Development: Positive Life Adaptations, eds M. D. Glantz and J. L. Johnson (NewYork, NY: Kluwer Academic Publishers), 225–228.

Jordan, J. (1992). “Relational resilience,” in Work in Progress No. 57 Wellesley, MA: Stone Center Working Paper Series.

Jordan, J. (2012). “Relational resilience in girls,” in eds S. Goldstein, and R. B. Brooks, Handbook of Resilience in Children (New York, NY: Springer), 73–86. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3661-4_5

Kaplan, H. B. (2002). “Toward an understanding of resilience: a critical review of definitions and models”, in Resilience and Development: Positive Life Adaptations, eds M. D. Glantz and J. L. Johnsonpp (New York, NY: Kluwer Academic Publishers), 17–84.

Kumpfer, K. L. (2002). “Factors and processes contributing to resilience”, in Resilience and Development: Positive Life Adaptations, eds M. D. Glantz, and J. L. Johnson (New York, NY: Kluwer Academic Publishers), 179–224.

Le Cornu, R. (2009). Building resilience in pre-service teachers. Teach. Teacher Educ. 25, 717–723. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2008.11.016

Le Cornu, R. (2013). Building early career teacher resilience: the role of relationship. Austr J. Teacher Educ. 38, 1–16. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2013v38n4.4

Liu, J. (1999). Nonnative-English-speaking professionals in TESOL. TESOL Quart. 33, 85–102. doi: 10.2307/3588192

Mansfield, C. F., Beltman, S., and Price, A. (2014). “I'm coming back again!” The resilience process of early career teachers. Teachers Teach Theor Pract. 20, 547–567. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2014.937958

McCormack, A., and Gore, J. (2008). “If only I could just teach”: early career teachers, their colleagues, and the operation of power,” in Paper presented at the annual conference of the Australian Association for Research in Education (Brisbane).

McIntyre, F. (2003). Transition to teaching: New teachers of 2001 and 2002. Report of their first two years of teaching in Ontario. Toronto, ON: Ontario College of Teachers.

Medgyes, P. (1992). Native and non-native: who's worth more? ELT J. 46, 340–349. doi: 10.1093/elt/46.4.340

Olsen, B., and Anderson, L. (2007). Courses of action: a qualitative investigation into urban teacher retention and career development. Urban Educ. 42, 5–29. doi: 10.1177/0042085906293923

Oswald, M., Johnson, B., and Howard, S. (2003). Quantifying and evaluating resilience-promoting factors: teachers' beliefs and perceived roles. Res. Educ. 70, 50–64. doi: 10.7227/RIE.70.5

Papatraianou, L. H., and Le Cornu, R. (2014). Problematising the role of personal and professional relationships in early career teacher resilience. Austr. J. Teacher Educ. 39, 100–106. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2014v39n1.7

Patterson, J. H., Collins, L., and Abbott, G. (2004). A study of teacher resilience in urban schools. J. Instruct. Psychol. 31, 3–11. Available online at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ774036

Richardson, G. E., Neiger, B. L., Jenson, S., and Kumpfer, K. L. (1990). The resiliency model. Health Educ. 21, 33–39. doi: 10.1080/00970050.1990.10614589

Ruohotie-Lyhty, M. (2013). Struggling for a professional identity: two newly qualified language teachers' identity narratives during the first years at work. Teach. Teacher Educ. 30, 120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2012.11.002

Rutter, M. (1999). Resilience as the millennium Rorschach: response to Smith and Gorell Barnes. J. Fam. Ther. 21, 159–160. doi: 10.1111/1467-6427.00111

Sammons, P., Day, C., Kington, A., Gu, Q., Stobart, G., and Smees, R. (2007). Exploring variations in teachers' work, lives and their effects on pupils: key findings and implications from a longitudinal mixed-method study. Br. Educ. Res. J. 33, 681–701. doi: 10.1080/01411920701582264

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: knowledge growth in teaching. Educ. Res. 15, 4–14. doi: 10.3102/0013189X015002004

Sinclair, C. (2008). Initial and changing student teacher motivation and commitment to teaching. Asia-Pac. J. Teacher Educ. 36, 79–104. doi: 10.1080/13598660801971658

Skaalvik, E. M., and Skaalvik, S. (2014). Teacher self-efficacy and perceived autonomy: relations with teacher engagement, job satisfaction and emotion exhaustion. Psychol. Rep. Employ. Psychol. Market. 114, 68–77. doi: 10.2466/14.02.PR0.114k14w0

Tait, M. (2008). Resilience as a contributor to novice teacher success, commitment, and retention, Teacher Educ. Quart. 35, 57–75. doi: 10.2307/23479174

Tang, J. (2011). Research on job burnout of college English teachers. Shandong Foreign Lang. Teach. J. 42, 56–61. doi: 10.16482/j.sdwy37-1026.2011.05.018

Veenman, S. (1984). Perceived problems of beginning teachers. Rev. Educ. Res. 54, 143–178. doi: 10.3102/00346543054002143

Wosnitza, M., Peixoto, F., Beltman, S., and Mansfifield, C. (2018). Resilience in Education: Concepts, Contexts and Connections. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-76690-4

Keywords: risk factors, resilience strategies, protective factors, Chinese context, novice college FL teachers

Citation: Fan L, Ma F, Liu Y-m, Liu T, Guo L and Wang L-n (2021) Risk Factors and Resilience Strategies: Voices From Chinese Novice Foreign Language Teachers. Front. Educ. 5:565722. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.565722

Received: 26 May 2020; Accepted: 04 December 2020;

Published: 13 January 2021.

Edited by:

Gary James Harfitt, The University of Hong Kong, Hong KongReviewed by:

Roza Valeeva, Kazan Federal University, RussiaEve Eisenschmidt, Tallinn University, Estonia

Copyright © 2021 Fan, Ma, Liu, Liu, Guo and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lin Fan, ZmFubGluQGJmc3UuZWR1LmNu; Lu-nan Wang, bHV0aGVyOTU5MUAxNjMuY29t

Lin Fan

Lin Fan Fang Ma

Fang Ma Yan-mei Liu

Yan-mei Liu Tao Liu

Tao Liu Lin Guo

Lin Guo Lu-nan Wang

Lu-nan Wang