- 1Bartiméus, Zeist, Netherlands

- 2Pedagogical and Educational Sciences, Nieuwenhuis Institute, University of Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands

- 3Royal Dutch Kentalis, Kentalis Academy, Utrecht, Netherlands

Typically developing children are exposed to multiparty communication on a daily basis from birth. This facilitates both group belonging and observational learning. However, involvement in multiparty conversations is not self-evident for people with congenital deafblindness due to their dual sensory impairment. This study explored the added value of multiparty conversations for people with congenital deafblindness by analyzing communication partners' narrations of their experiences. Three focus group sessions were conducted with professionals and relatives (n = 24) of people with congenital deafblindness. These sessions were audiotaped, transcribed, and coded using thematic analysis. Participants described the following defining characteristics of multiparty conversations in relation to congenital deafblindness: a minimum of three people involved, with at least one who has congenital deafblindness; awareness of the presence of the other communication partners; attention for the communicative setting; and the use of communication means that are familiar to all communication partners. In their experience, multiparty conversations supported social, emotional, and communication development. Furthermore, focus group participants indicated that spontaneous multiparty conversations with people with congenital deafblindness were scarce and, therefore, needed to be encouraged by communication partners. The participants considered positive beliefs, preparation of the multiparty conversation, repetitions, and a low communication speed as important partner competencies to support the involvement of individuals with congenital deafblindness in multiparty conversations. Accordingly, we recommend the development of an intervention protocol for communication partners to initiate and foster multiparty conversations with people with congenital deafblindness. Another recommendation is to test the effects of MPC on the observational learning of people with congenital deafblindness.

Introduction

Human beings are social in nature and thoroughly interdependent in functioning and development, both as a species and as individuals (Linell, 2009). However, for people with congenital deafblindness, communication with others is a huge challenge. Congenital deafblindness (hereafter abbreviated to CDB) refers to both a vision and hearing impairment that originated in utero, at birth or shortly after, at least before the onset of language development (Dammeyer, 2014). Deafblindness is characterized by heterogeneity, due to differences in onset and variance in sensory, psychological, and cognitive functioning (Dammeyer, 2014). People with severe vision and hearing loss of congenital origin have very few opportunities to learn cultural language in an informal way. Typical means of communication are not attuned to the (often idiosyncratic) communication of a person with CDB (Bruce et al., 2007). Furthermore, their personal expressions are often not recognized by others (Hart, 2006; Vervloed et al., 2006; Dalby et al., 2009; Nafstad and Rødbroe, 2015). Due to this low readability of communicative expressions, adults, and teachers need guidance and instruction (Correa-Torres, 2008; Nijs et al., 2016). Studies show that the communication skills of people with CDB can increase if communication partners lead by example (Damen et al., 2017) and share emotions in communication (Martens et al., 2017).

In multiparty conversations (hereafter referred to as MPC) more than two communication partners are involved. Where dyadic conversations only include the roles of speaker and addressee, MPC also involves roles of side participants and overhearers (Clark, 1996). MPC involves a broad spectrum of conversations between three people and up to large group conversations. Even listening to a conversation between two others without being directly addressed is included, since the presence of this third person shapes the actions of the two others (Clark, 1996). Studies on group conversations often focus on three-party, or triadic, conversations, which has less possible directions of communication than tetradic (four-person), pentadic (five-person), and more-person setups (Greene and Adelman, 2013). In daily interactions, however, all these possibilities occur. To account for this broad spectrum, the more general term MPC is used in this study.

Although MPC is common in spoken language, examples of MPC with people with CDB are relatively scarce. Most typically developing children and adults without CDB are exposed to MPC from birth and all day long (Barton and Tomasello, 1991; Gräfenhain et al., 2009). Close observation of the behavior of babies reveals a rich variety of infant sociality (Bradley and Selby, 2004), with peer interactions from the first weeks of life (Hay et al., 2008). However, children with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities display relatively few peer-directed behaviors and mutual responses could not be observed (Nijs et al., 2015, 2016). An active mediating role of adults is needed in order to encourage their peer interactions, by creating optimal conditions (Kamstra et al., 2019). Teachers of children with deafblindness in inclusive school settings also aim to facilitate social interactions by modeling and stimulating social interactions (Correa-Torres, 2008). It can be hypothesized that these situations, in which a third person stimulates interactions between two others, are MPC as well, since at least three persons are involved in the conversation.

All persons with intellectual and/or sensory disabilities are at risk of missing information within their conversations, but people with CDB are particularly unable to perceive other people's communication at a distance. Although they may sense the presence of others, their opportunities for unintentionally overhearing a conversation are scarce. Communication partners are often too far away to fulfill the requirements for communication with a person with CDB (Vervloed et al., 2006). Due to their sensory impairments, communication partners need to be close to people with CBD to enable them to notice and understand what is going on (Malmgren, 2019).

Being engaged in conversations is always an active process, even if they are listening or taking time to think (Nafstad, 2015). For persons with CDB this is even more prominent, because communication relies on the tactile modality. In tactile communication, listening involves participation through active reciprocal movement (Worm, 2016). In a verbal conversation, there can be any number of participants, and as long as there is space for contributions, there is no impact on comprehensibility. However, for people communicating through the tactile modality, the hands need to be available to all participants, so that the ability to comprehend what is going on is directly influenced by the number of participants.

MPC has both qualitative and quantitative properties that teach children different aspects of language and cultural membership than does dyadic communication (Blum-Kulka and Snow, 2002). Having only dyadic conversations does not allow a person to learn about the concept of “we” beyond “you and I” (Lundqvist, 2012). The importance of MPC for social development is endorsed in developmental theories. From birth humans are attentive to multiple communication partners simultaneously (Tremblay-Leveau and Nadel, 1995; Fivaz-Depeursinge, 2008; McHale et al., 2008; Thorgrimsson et al., 2015). Children are innately capable of having manifold relationships with both adults and peers, having a “multiple self that is engaged in groups” (Selby and Bradley, 2003, p. 216). Being a species that survives in groups, our capacities for MPC develop similar to dyadic conversations in line with general communicative and social development (Selby and Bradley, 2003; Fivaz-Depeursinge et al., 2010). While occupied in multiparty play, an infant has opportunities for sharing affect and obtaining social feedback. This group-context provides enlarged and enriched opportunities for self-other differentiation (Fivaz-Depeursinge et al., 2010).

MPC is not only associated with group belonging but also enables learning through witnessing the actions of others (Akhtar et al., 2001; Shneidman et al., 2016). This process is called informal learning, which is, in contrast to formal learning, spontaneous, and subconscious (Boekaerts and Minnaert, 1999). One of the forms of informal learning is observational learning. Bandura (1986) claimed that most behavior that humans perform is learned by observation. He reasoned that the costs and efforts of trial and error are spared by observing modeled behavior and its consequences. Also, behavior that has already been learned would be both activated and inhibited by observing others perform that same behavior. The attention of the spectator is a key element for observational learning (Bandura, 1986). Being in a multiparty setting can support a child's understanding of relationships through their participant-observer perspective (McHale et al., 2008; Fivaz-Depeursinge et al., 2010). Learning by observation promotes acquisition of new competencies, cognitive skills, and behavioral patterns. Modeled situations can affect a person's level of motivation and restraints in the same or similar situations. Overhearing others' conversations supports the understanding of a person's own prior experiences and generates new ideas (Miles, 2003). Furthermore, it has a direct influence on the arousal of the observer, serving as a guide for the development of attitudes, values, and emotions (Bandura, 1989). So, in order to understand human behavior, people need to observe others in multi-person interactions.

Natural opportunities for casual observation of communication and social interaction, as described above, do not occur naturally for persons with CDB due to their sensory impairments. This means that the process of observational learning, which is usually spontaneously present in development, may not apply at all, or may be fragmented. Their observational learning requires purposeful intervention by their communication partners in a natural environment (Rødbroe and Janssen, 2006). MPC can be a means to encourage observational learning. However, how and to what extent MPC is currently present in the conversations of people with CDB remains unclear. Interventions on communication with people with CDB who have limited expressive language are almost exclusively restricted to dyadic (one-on-one) conversations (Lundqvist, 2012). This also applies to research practices: in an evaluation of over 30 studies on communication and literacy in children and young adults with deafblindness (Bruce et al., 2016), MPC is mentioned nowhere.

As a result of this lack of attention to MPC in both research and practice, no prerequisites or guidelines for communication partners have been formulated yet for having MPC with a person with CDB. In the past decade, some practitioners have enacted MPC with people with CDB and shared their proceedings at conferences or in case descriptions in master's theses (cf. Lundqvist, 2012; Worm, 2016; Nafstad and Daelman, 2017; Lindström, 2019). These exemplary cases demonstrate that MPC is possible for people with CDB. Potential benefits of MPC on the participation, understanding, and language learning of persons with CDB are described by Malmgren (2019). Nevertheless, these experiences are not yet reflected in peer reviewed publications, which inhibits the circulation of such practices and their effects.

The current study was therefore initiated to retrieve and explore practice-based knowledge on MPC with people with CDB. The overall aim of the study was to explore how MPC can contribute to observational learning in people with CDB. Research questions were designed to understand how MPC has been operationalized and how it was used by communication partners in their conversations with people with CDB. The research questions were:

(1) What is an operational definition of MPC in the case of CDB?

(2) What is the perceived added value of MPC in addition to dyadic conversations for this target group?

(3) Which competencies do communication partners need to enact and maintain MPC with people with CDB?

Method

Materials and Procedure

In the current study, focus groups were used to obtain detailed practice-based reports of communication partners of people with CDB about their perspectives on and experiences with MPC. Since the topic is relatively new, open discussions can increase the knowledge base and at the same time help retrieve, discuss, and reflect on relevant issues concerning this topic. By sharing and comparing experiences, the participants build on each other's expressions, generating rich information on the topic (Morgan, 1997). In a period of 2 months, three focus groups were conducted in meeting rooms at organizations for people with sensory disabilities in the Netherlands. Each focus group met once in a 90-min session. The first, second, and third sessions included eight, nine, and seven participants, respectively. One of the participants in the second focus group session participated simultaneously over video.

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee for Pedagogical & Educational Sciences at the University of Groningen.

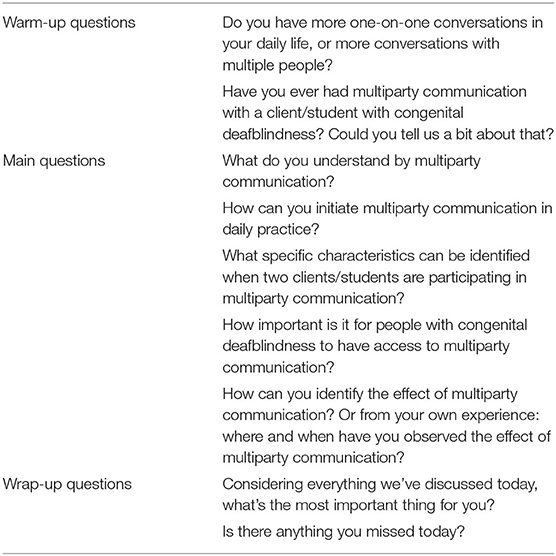

The focus group sessions were conducted following a standardized procedure and standardized set of questions (Krueger and Casey, 2009). Before the focus group sessions started, participants received both spoken and written information about the aims and procedure of the focus group sessions and gave written informed consent. Furthermore, they were asked to complete a short demographic questionnaire. Then, the first moderator explained the goal and the procedure of the focus group session. After that, the audio recording started and the first question was posed. The focus group sessions were based on nine questions: two warm-up questions, five main questions, and two wrap-up questions (Table 1). These questions aimed to collect the narrations of participants about their experiences with MPC: when, how, and by whom it was enacted and which effects were attributed to MPC. The focus group sessions were in Dutch language. Since the term “multiparty conversations” was relatively new to the field, the first moderator used the terminology that was used on site, which was “multi-partner communication,” “multiparty conversations,” and the abbreviation MPC. The focus group sessions lasted approximately 90 min, including the forms, the introduction, and the wrap-up.

In each focus group session, two moderators were involved. The first author was the first moderator and conducted the focus groups. Each focus group session had a different second moderator, which was a therapist on site. The second moderators took notes in case the recordings failed. Both moderators were seated at the table with the participants. The role of the first moderator was to facilitate the discussion around the questions and to summarize the issues mentioned. The second moderator did not take part in the discussions and acted as observer and notetaker. After the focus group sessions ended, the first and second moderators checked the audio recordings and discussed the notes and observations together.

Participants

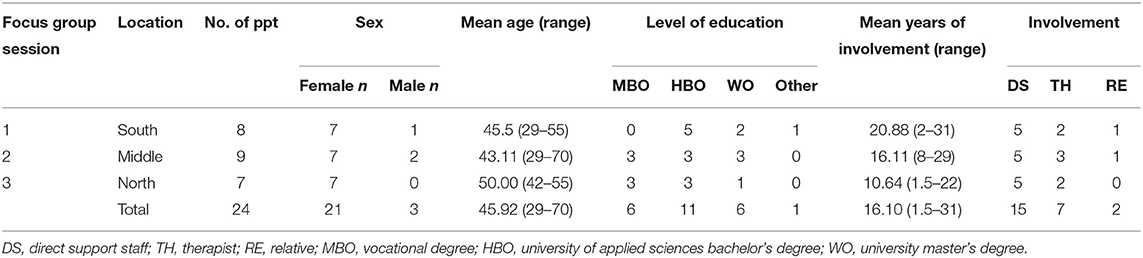

A total of 24 participants joined one of three focus groups: 2 relatives, 15 direct support professionals, and 7 therapists (psychologists, speech therapists, and care specialists) of people with CDB. All three focus groups consisted of direct support staff and therapists. Furthermore, the second and third focus group included a relative of a person with CDB. Most focus group participants were female support professionals. The mean age of the participants was 45.9 and they had an average of 16.1 years of experience with people with CDB. Further characteristics of the focus group participants are presented in Table 2.

Participants were recruited from the professional network of the second moderator. The second moderator targeted persons who had a background of MPC with persons with CDB, since these persons could use their experiences to add to the knowledge base. All participants were professionally or personally related to the organization where the focus group sessions were conducted. Two of the organizations provide residential care and daily activities for adults with CDB. The other organization mainly provides services for children and provides education and residential care. The participating employees of the organizations were enabled to join during their working hours in order to maximize participation. The participating relatives received a gift card as a token of appreciation for their contribution. Since MPC is a relatively unknown communication strategy in conversations with people with CDB, it is not yet practiced systematically in other care organizations in the Netherlands. That is why a total of three focus group sessions was considered the maximum for the current study.

Data Analysis

Audio recordings of the focus group sessions were transcribed verbatim by the first author. Since no video recordings were made, the analysis is primarily based on participants' verbal expressions. A thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) was conducted using the software program ATLAS.ti 8. Initially, the transcripts of the focus groups were read repeatedly to immerse them with the data. The analysis was based on the research questions, which concerned an operational definition of MPC, partner competencies needed to elicit and sustain MPC, and the added value of MPC for people with CDB. First, all participant responses, whether directly related to the research questions or not, were clustered in initial codes. Relationships between codes were presented in an initial thematic map. Both the categories and the thematic map were presented to the second author and an experienced practitioner in the field of CDB to review the analysis. They independently checked the match between the codes and their associations. Their feedback and suggestions were part of the iterative process that followed, during which the first author reviewed the data, codes, and subthemes. The scope and content of the themes and subthemes were subsequently described and accompanied by a refined thematic map. The three second moderators reviewed this part of the analysis to ascertain whether the identified subthemes appropriately reflected how they experienced the focus group session they attended. Furthermore, the authors evaluated the description of the data analysis in terms of comprehensiveness and coherence. Once again the transcripts, categories, and subthemes were reviewed by the first author and the thematic map was finalized. After that, the first author substantiated the analysis with quotations from the interviews.

Results

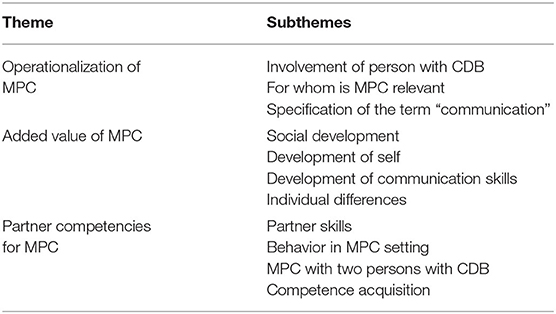

The results are described in line with the three main research questions: (1) an operational definition of MPC in relation to CDB, (2) the perceived added value of MPC for people with CDB, and (3) the required partner competencies needed to have MPC with people with CDB. A thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) highlighted participants' perspectives on and experiences with MPC with people with CDB in three subthemes for each theme (Table 3). Each subtheme is presented by a reproduction of the perspectives of the participants, exemplified by relevant quotations. The quotations, which were in Dutch, were translated to English verbatim. For readability purposes, hesitations and filler words like “erm…well, um…” were removed from the text. To ensure anonymity, each quotation is preceded by a code. Each focus group session has a number (i.e., F1, F2, or F3), and the same applies to the participating professionals (e.g., P1) and relatives (e.g., R1). Moderators are referred to as M, people with CDB as X, and other communication partners as C.

Operationalization of MPC

The participants of the focus group sessions were asked what MPC meant to them in the case of CDB. They stated that in order to call it MPC with a person with CDB at least three people should be involved, at least one with CDB. Three subthemes regarding the operational definition were discussed: the required level of involvement of the person with CDB, who would benefit from MPC, and what communication specifically means in MPC.

Involvement of Person With CDB

The meaning of the concept “involvement of the person with CDB in relation to MPC” was discussed in the focus group sessions. A focus group participant stated that for people without disabilities, conversations were already multiparty when multiple people were in the same room. Participants reasoned that those people could hear the ongoing conversation and therefore choose to participate at any moment. This was considered different if people with CDB were involved. Several participants mentioned that people with CDB have limited opportunities to notice conversations in their surroundings and/or to elicit MPC themselves due to their sensory impairments. The first subtheme therefore concerns the required level of involvement of the person with CDB in the conversation in order to call it an MPC. Some of the focus group participants argued that a distinction should be made between being able to overhear a conversation but choosing not to join in, and active involvement. Others suggested that just being in the same room could be enough to realize communication is taking place. In their opinion this created an MPC situation, even though the person with CDB could not understand the content of this conversation. They discussed that being aware of others is not necessarily the same as being aware of the content of the conversation. At the end of the discussion, focus group participants summarized that the communication should at least be both perceivable and understandable for the person with CDB.

F1P3 But there needs to be at least some level of attention. If the child has his back to you, I don't really think you can have a multi-partner conversation, even if he's right there… So there needs to be some attention.

F1P3 In a normal family situation, I think it's pretty common for a child to be doing a heap of different things and still pick up a lot. But that's also harder to check with our students.

F2P17 I think the definition is that all three are aware of each other. That's the bare minimum.

F2R2 And you need to speak the same language, and by language I mean bigger than just the language, yeah. The transfer of meaning… understanding each other.

F3P18 In any case, that there are several people… talking to each other.

F3P19 Listening is also active.

F3P23 We've been talking about multiparty conversation. But I, yeah, I assumed that's… we're conversing with three people and… that's at least… two who have an active role in the conversation and one listens.

According to focus group participants, involvement in an MPC may vary from overhearing to joining in another person's conversations. Attention of the person with CDB is regarded as an important indicator for involvement. However, opportunities for incidental listening in a conversation are considered small for persons with CDB and are dependent on the availability and comprehensibility of the language.

Which People With CDB Benefit From the Added Value of MPC?

The second subtheme looks at who would benefit from MPC. Focus group participants considered people with CDB to be a very heterogeneous group. They emphasized that a person's sensory functioning defined how they could be involved in the MPC. Furthermore, it was stated that people with residual vision and/or hearing had more opportunities to overhear a conversation.

Some focus groups participants questioned how much need people with CDB and cognitive and/or developmental challenges have for MPC. It was also questioned whether MPC would be possible if the communication level of the person with CDB was low. They reasoned that MPC might be too complicated for these people. Others replied that you could arrange the MPC situation into an understandable interactional setting.

F2P13 First you need to know which senses you can engage in a conversation. Does someone have some residual hearing, does someone have some residual vision? Must it be completely by touch?… Does someone want you to be closer or do they prefer more distance in their contact?

F3P20 I really think that's… a world of difference. If you can hear and see or can still hear and see a little bit. Yeah, I really think that… really makes a world of difference.

F1P4 I have a boy in my class who uses tactile signing. And that's all he's got and so I end up not communicating [in MPC] with him as much.

F2P13 How much of a strain are you placing on someone? If somebody has… such a low level of communication skills or social emotional level… how… How much can they handle? Are they getting too much information? Way too much sensory overload? I'm really talking about a very low level. I think for… The majority, I actually think it's a right that you… can have contact with different people… at the same time. Because it expands your world…

F2P17 I agree with you that you have to take it slow. But I still think… Not trying, because you're afraid it's not going to work… Of course that's.… Even if someone's, someone has low level functioning…. They sometimes have that for 50 years. You can't compare them to a baby… lying in their crib. Where, by the way, a baby could be lying next to another twin and therefore also be engaging in multiparty conversations. It depends on what you're exposed to as well.

F2P13 And I definitely agree with you that… you should at least try. Because hey. Whatever I said: I think it's a right for us to have contact with… our surroundings. So also with different people around you at the same time.

F3P21 The… level of development. If that's… very low… and hey, around the age of one we also have. I mean, a 1 year old doesn't have conversations with four people either… doesn't have that need either. But that child does have a need to know: what will my day look like? So that's why I said the same about X15.

F3P20 And maybe in an interaction game as well. So what I was just saying. That's with a 1 year old with their mom and dad, for example… They can easily switch between them. Yeah. So that's… you could… take that into account… yeah.

F3P21 It is very difficult to determine the level. So it could just as well be higher than we think. And is there a need, but… someone doesn't have… the tool or the opportunities to make that clear.

F3P20 They may have a different need, but you shouldn't withhold that from them, no matter what… the level of development or what… their need seems to be.

Focus group participants expressed that they initiated most MPC with CDB persons with residual vision and/or hearing. However, they thought all persons with CDB could potentially profit from MPC. They often found it difficult to judge the communication desires of an individual with CDB. Therefore, they suggested not to exclude anyone with CDB from trying MPC.

Specifications of Communication

The focus group participants discussed the forms of communication that should be included in an operational definition of MPC. They questioned whether a distinction should be made between multiparty interaction and multiparty communication. Interaction was seen as the sharing of an event, while communication included the exchange of meanings. It was suggested that interaction is a precursor of communication and has its own specifications. An alternative viewpoint was that the content of the communication is of no importance for an operational definition. A multiparty setting was conceived possible both within interaction and/or communication.

F1P6 If it's possible, because then… conversation may not be the right word, but contact might already… [interrupted]

F3P20 Interaction really is a prelude to communication, isn't it? That you first need to… take turns… understand that the other person… needs room to respond to that… that's when communication begins… Yeah. I… but you share an experience together. And there is some turn-taking it that. Yeah.

F3P20 And I think… the discussion about whether that game is interaction or communication perhaps isn't so interesting or important. If you see it as a prelude to turn-taking… which is part of your communication, you can at least use it as a starting point. If that works well for someone. That's what I think.

So, focus group participants discussed a potential distinction between interaction and communication in MPC. Since this distinction is not multiparty-specific, but relates to all acts of communication, this topic will not be elaborated on in this article.

The Perceived Added Value of MPC for People With CDB

Following thematic analysis, three subthemes were identified on the topic of added value for people with CDB: social development, development of self, and development of communication skills. Hereafter, individual differences in added value of MPC are discussed.

Social Development

Regarding social development, MPC is thought to broaden the world of people with CDB. In all focus groups it was mentioned that MPC contributes to group belonging. One focus group participant explained that people with CDB learn from MPC how people mutually exchange perspectives.

Participants also suggested that with MPC, the person with CDB learns what social groups are and how people can be involved. In their opinion, this knowledge generates a sense of belonging. Participants explained that MPC can lead to a person with CDB feeling more connected to others, and that in turn supports the development of social interaction skills.

In addition, one of the focus group participants explained that the seeing-hearing communication partner can use MPC to encourage initial peer interactions. In their experience, some people with CDB have been in the same places with others with CDB for a long time, but have never communicated with each other. MPC was used in those instances to introduce them to peer-to-peer communication.

F2P12 That… our children, so to speak… don't often… or at least don't automatically realize they actually belong to a social group.

F3P20 That you come out of your isolation. So that you… understand or experience or feel… that you are a part in a larger whole and that you belong. And that those other people are there too.

F1P6 And so you have many different goals, because this is also raising awareness of the fact there are other children in the classroom and discovering that. And the other is again… creating awareness that the other can have… their own opinion about swimming and so you can use it quite broadly.

F2P13 That it's actually, whatever we're talking about… it's not so much about communication, but much more about contact. Right. Being together and realizing there are other people around you. That you're a part of that.

F2P15 It can also help… a bit of social interaction with each other. At least… that's what I do myself. That you let clients help each other and that you do that together, but let them help each other, that's also good for their self-confidence.

F2P17 Because that's the underlying goal, sometimes behind that goal. The social interaction and the social cohesion and the rules of behavior.

F1P1 So that girl had a lot of trouble listening, but then she learned.. So you could teach her, you could teach her to do that. Wait a sec.. and.. what X6 says. First listen to X6.

F1P4 You often see that the children kind of exist separately from each other in the classroom. Yeah, that doesn't sound pleasant, but that's often the case, because they're very focused on the adult. And this is a great tool to get them to share something with each other.

So, in the domain of social development, learning about social interaction rules, encouragement of peer interaction, and development of group belonging were the main topics discussed in the focus group sessions.

Development of Self

In the domain development of the self, communication partners described how MPC contributes to sharing emotions. Effects on self-development were not only described within the MPC situation, but focus group participants also observed effects on general personal development. For example, an increase in self-esteem, relaxation, alertness, and joy were all related to MPC in the narrations of focus group participants. One focus group participant expressed how people with CDB increasingly expressed themselves within MPC, for example, by taking more pronounced initiatives in the conversation. A different focus group participant suggested that the enhanced feeling of being understood may lead to a decrease in self-injurious behavior.

Taken together, focus group participants exemplified how MPC encouraged persons with CDB to express themselves, which was regarded as a growth of self-esteem and confidence.

Development of Communication Skills

The last subtheme is that MPC is thought to have good properties for developing communication skills. Focus group participants mentioned in particular the aspects of turn-taking, understanding the structure of a conversation, and understanding the speaker/listener roles. For example, one participant described MPC as being a good setting to show how to ask a question. MPC also provides examples of how to introduce a topic and which information is shared within conversations. Moreover, participants mentioned that they had observed enhanced communicative capacity in the person with CDB during MPC, because the person had learned new gestures and signs. In multiple focus groups it was mentioned that the person with CDB does not need to be an active communicator to learn these aspects of communication. Their experience was that a person with CDB often chose a listening stance just after the introduction of MPC and that over time they also took the position of speaker.

F3P20 I think that's the beauty of it, someone else having an interest in you… that gives… a lot of value to life.

F2R2 And that… I think that boosts your self-esteem, right? In the sense that you matter. That there are other people who concern themselves with you.

F3P23 But now he's much more relaxed. And that doesn't necessarily have to be because of that, because it's of course also… that he's used now to going to daily activities. He has only had that for 3,5 years, but… yeah, I think it helped him.

F2P11 That someone is becoming more alert or… taking more initiatives of their own… While at first they might think… What's happening here? And is quite hesitant and just listens. Or just experiences it. And later in the process they can be prompted to… take initiatives of their own… and… F2P16 And enjoy that.

F2P18 Because that's very important, because it makes life more fun.

F3P18 And… movements become… bigger. If it's really all in their own little world, they use arm movements, they're… they're all smaller. When they become more aware there are more… people, and also, often… they start expanding their gestures. F3P19 Yeah. Does that make you feel freer? Orgive you more courage? Yeah, dare to reach out more to the world I think… yeah. F3P21 Yeah, you dare to test the boundaries. Literally and figuratively.

F2P17 I can imagine that… if you're understood more often, then eventually, the self-mutilation will decrease.

Several focus group participants stated that MPC contains much declarative communication (communication that has the purpose to share meanings; see Damen et al., 2015). For example, one participant described MPC being used to reflect on past activities of the person with CDB and/or to share emotions. In one of the focus group sessions, this was compared to dyadic conversations with people with CDB, which was said to cover mostly imperative communication (in which a person's intent is to obtain their own goals by means of the other; see Souriau et al., 2008).

Thus, focus group participants expressed how MPC highlighted aspects of communication skills: how to ask questions, speaker/listener roles and the sharing of thoughts and emotions. Also, they gave examples of how MPC had encouraged language use.

Individual Differences

Focus group participants expressed that effects on the development of the person with CDB are often not immediately visible and effects may appear small. In participants' experience, the speed, and size of effects depends on the individual characteristics of the person with CDB. For example, one focus group participant reported she immediately noticed effects, while another participant described that one-and-a-half years had passed before the effects were visible in the person with CDB. Participants experienced it as rewarding to notice that the person with CDB understands MPC and is able to participate in MPC.

F1P4 But for me it's very much there being two competent partners, maybe more. Who can give a good example. And it that's with really technical questions yes and no, or the… With one boy in my class we really had to shape: How do you ask a question? Otherwise, great if two others can show you how, right? You can't do that one-on-one. How can I demonstrate to you the right way to ask a question.

F1P1 The turn-taking… taking turns… that there's one, that girl had a lot of trouble listening, but then she learned… So you could teach her, you could teach her to do that. Wait a sec.. and.. what X6 says. Just listen to X6 and yeah. It had a lot of added value… those conversations.

F2P14 Then we saw her taking more of her own initiative to communicate. And saw the conversations were longer, too. And not just functional, but also about other topics… So that certainly helped enrich her life.

F1P5 Yeah, because at a certain point, you see he wants to share things. Where, in the beginning, he was just the listener. And only joined in occasionally. At a certain point he started saying: yes, but I want this.

F2P13 Well, in my experience, that sometimes lead to new gestures… or signing coming out of that. That you're working on something, and that leads to a kind of new gesture or sign. Yeah…

F1P6 And at a certain point, he also… started signing your name.

F3P20 No, not.. yeah, indeed. That you can also… have contact without having it to result in an action. F3P21 Not just functional. Yeah. F3P20 Because of course that happens a lot and it's… like… we're going have a drink now, we're going to do this, we're going to do that.

F1P5 We really feel that he… that multi-partner conversations really helped… helped to get him using declarative communication.

In the focus groups was also discussed how some people with CDB may have no desire for MPC. Participants had experienced that some people with CDB required several repetitions of MPC to become familiar with this conversational setting. Those participants pointed out that the first reaction to MPC is often unpredictable. A refusal can, in their opinion, also be explained by (un)familiarity with the conversation type. Examples given by focus group participants illustrated that in their conversations, they have far less MPC with people with CDB than with people without CDB. However, several participants also unexpectedly noticed a naturalness during their MPC with people with CDB. Their suggestion was to simply try MPC and see what happens.

Although the individual effects of MPC may be unknown beforehand and be invisible during the first introduction of MPC, focus group participants believe communication partners need to offer multiple MPC conversations to persons with CDB. Narrations of focus group participants point at developments that may be expected and unexpected at varying developmental speeds.

The Required Partner Competencies

Participants of the focus group sessions mentioned that people with CDB are dependent on their communication partners to be able to have MPC. Since these types of conversations rarely happen spontaneously in their conversations with other people with CDB, one focus group participant suggested introducing it purposefully.

F1P4 What I enjoyed about it was that it was a kind of quest and that… that it actually turned out… that it could serve multiple purposes.

F2P13 I don't think the result necessarily has to be overly spectacular.

F1P5 But that we are now seeing… after 1.5 years that he can occasionally focus on two people and can enjoy that as well.

F2P11 But I think that it's… that it's simply a matter of just doing it… and along the way… solving the… problems you run into or… You can't come up with that beforehand anyway.

F1P6 Knowing there are also people who don't at all enjoy group conversations… or who struggle with difficult… also in our… F1P8 But still… you have to try it to figure that out. Because, you cannot say from the start: Oh, we are not going to do it with you. F1P3 And not just once. If it doesn't work the first time, that's a reason to wait a while and maybe try again later, because they have that right to it.

F3P19 And I can see that it's very natural. Just very, yeah. I've never had a client who thought: well, that's weird or whatever.

F3P18 And if they don't know it's there, they can't or don't seek it out either.

F1P4 I think that's where the strength of it lies. That… our children, so to speak… don't often… or at least don't automatically realize they actually belong to a social group and that they're not one-on-one either. There are also other people. That it's nice when you create a situation like that to start out with, where they are present together with each other and each in their own way can experience that.

Analysis of the focus group discussions revealed three subthemes on partner competencies. The first subtheme is that communication partners need certain skills to enact MPC with people with CDB. The second is that the behavior and expressions within the MPC setting are of importance. The last subtheme considers how the competencies needed for MPC can be acquired by communication partners.

Partner Skills

Participants of all three focus group sessions expressed the opinion that communication partners of people with CDB need skills to initiate MPC in their conversations. First, multiple participants suggested that communication partners needed to make a conscious choice to use MPC as a means of communication. They also mentioned the value of believing a successful outcome is possible. Besides that, focus group participants suggested observation skills and empathy are important. They have experienced that potential initiatives and reactions of the people with CDB are often subtle and therefore easy to miss.

Taken together, participants of the focus groups expressed that communication partners need to introduce MPC to a person with CDB purposefully and need observation skills within the MPC.

F3P23 You really have to, it's a precondition really, that you believe in it yourself. Not all of our team think oh, that's great, let's do it.

F1P3 It's also about having faith in the other person, in X1 in this case. That he'll pick it up. Cause otherwise you're not going to do it, are you, otherwise you'll stop signing because you think… Think like: he can do it… And I think that's part of that multi-partner, too… You also trust that the other person will at least pick up parts of the conversation or maybe the whole conversation. Even if he doesn't participate very…actively.

F3P18 You need to be aware that we're all here together and… that… Someone who's deaf-blind lives in a smaller world. That you… have to involve her to let her know the world is more than… bigger, that's the start.

F2P10 But I think there are an incredible number of clients where it is possible and where… but we just don't know yet how to do it.

F2P11 Attention and focus.

F1P Stay tuned to each other.

F2P17 It requires constantly looking and reviewing what… what we consider meaningful.

Partner Behavior in the MPC Setting

The second subtheme considers the setup of the MPC setting and the behavior of the communication partners. The focus group participants relatively often selected promising situations to enact MPC conversations, for example, during special activities or the moment the person with CDB is returning home after a workday. They suggested considering circumstantial and personal factors when choosing the situation for an MPC. For example, a hectic environment was regarded as difficult for MPC, because it distracts the attention of the communication partners.

Participants also described their actions and attitudes to facilitate the introduction of MPC. In particular, preparation of the conversation, the use of repetitions, and low expectations about the duration of the conversation improved their confidence in practicing MPC with a person with CDB. For example, multiple participants stated that they gave a person with CDB additional time to process the information that was exchanged within the conversation. Participants furthermore stressed that flexibility on the course or the outcome of the conversation was required. One of the participants illustrated this by describing that every communication partner, including the person with CDB, can introduce or end conversational topics.

In order to achieve shared meaning within the MPC, it was suggested that communication partners could adopt the means and level of communication of the person with CDB. Participants explained that tactile communication (like tactile sign language or fingerspelling in the hand) was the most difficult means of communication to use within MPC. Expressing yourself in tactile gestures that are intelligible for all communication partners was seen as a challenge.

Several focus group participants said that in their opinion the best people to introduce MPC to a person with CDB are familiar communication partners who have established a relationship with the person with CDB. Also, feeling supported by a more experienced colleague boosted their tendency to start an MPC with a person with CDB.

F2P11 But also create a situation you can talk about and have feelings about perhaps.…

F1P1 I used to think it was very important that… yeah, that I wasn't disturbed or interrupted, cause then I might quickly lose my attention again.

F3P21 We often talk during dinner. Often have family conversations. But I can imagine that's not handy for the clients. Cause even eating can be quite a hassle sometimes.

F1P4 We often even schedule it carefully into the roster. And then you connect to for example an interaction moment of the child… Or in advance you have… talked a bit about what you are going to do, for example with those technical things like how to respond with a yes or no, or asking a question, but it would be much better if…that should be the first step to using this a lot more, you know?

F2R2 When you… start something then… you need continuity in it too. Even if you only do it once a month… twice a month… or how ever often.

F3P24 I agree it's important for him that you keep it small, too. F3P23 No, it's really about one thing and not two.

F1P5 It can sometimes be a short 2-min conversation, can't it? It doesn't have to be… F1P1 Yeah, it doesn't have to last hours.

F1P6 You can even during one conversation you can… we have an example… where… a little boy at a certain point clearly indicated: Now I need time to process it. Now I…want… really regulating the conversation and turning away from us. And at a certain point came back and wanted to check… check that: Are you both still here?

F3P24 And indeed, he's allowed to walk away. And sometimes he does walk… He goes to his planner and then… Well then that's it… it's over.

F1P8 It took me a while to figure out how to make sure the deaf-blind person really gets what I… say. How do I do that with signs, how do I talk, watch…

F3P23 But we're really still trying to figure out the hands. We've now got, like, an agreement on how we approach that.

F2P10 You need to be able to… sign.… yeah.

F2P15 I think it also matters whether you… of course with one client you'll have more of a click than with another. That that also matters in what you… do. F2P11 That's related to connection again, of course… F1P1 I think it's important that you know them well.

Thus, focus group participants appointed several aspects within the MPC situation to take into account: start the MPC in an appropriate situation, use the means of communication of the person with CDB and use repetitions within, be flexible in the course and the outcome of the MPC, and learn from familiar and experienced communication partners.

MPC With Two Persons With CDB

Focus group participants also discussed specific aspects of an MPC with two people with CDB and one person without CDB. They suggested that this type of MPC has specific characteristics that should be taken into account. In their experience, the seeing-hearing communication partner needs to be both communication partner and moderator. Often, they also need to adopt the role of interpreter. For example, one focus group participant stated that the seeing-hearing communication partner needs to make sure all communication partners are aware of each other's presence and understand all the contributions to the conversation. Participants also pinpointed this as a complication for communication partners. In their opinion, it is difficult to simultaneously use different means of communication within a conversation.

F1P1 It's a lot more intense for you.

F1P1 You really need to make sure they're both… transmitting, receiving and it's all going well. And did he understand that? Did she hear that?

F2P13 It's really an additional task you have. To make sure it's not going too fast for the other client, for example.

F1P3 They don't all speak the same language.

F3P22 And then you have to speak both their languages. Because they can really differ.

F321 You're kind of an interpreter really.

F1P2 You also really need to.. the turns… direct the turn-taking.

F2P13 But… yes, more guidance. That you.. yeah. Focus more on the form of communication. Of both clients.

Communication Partners' Acquisition of Competencies

The third subtheme on partner competencies concerns the training of communication partners in MPC. The focus groups participants indicated that communication partners do not need a natural ability to use the described competencies. Within the focus groups, examples were presented in which communication partners instructed each other. One of the suggestions was to watch and evaluate good examples of MPC with people with CDB. It was also mentioned that narratives about successful MPC can inspire others. In addition, it was stated that experience with this conversation type needs to be built. Focus group participants described how they learned to have MPC with people with CDB by practicing and experiencing MPC with people with CDB. One focus group participant emphasized that not only the successful conversations were helpful; also, the conversations that turned out differently than expected were considered to be good learning experiences.

So, focus group participants exemplified how partner skills developed during practicing MPC with persons with CDB. Their self-confidence developed accordingly as a result of these experiences.

Recommendation for Future Practice

Overall, participants of all three focus group sessions thought MPC should be offered much more to people with CDB.

F1P2 At a certain point, you just start and then… Then you see that it works and then it's well… Much smaller, so to speak, than with the older children, but. Yeah, it is possible.

F2P11 But I think that it's… that it's simply a matter of just doing it… and along the way… solving the… problems you run into or yeah… You can't come up with that beforehand anyway.

F1P3 By scheduling it you practice and you simply become familiar with it and that makes it easier.… F1P8 Yeah, and it makes you more competent.

F1P1 With me it helped that I'd done it more often with M2 and that I was a bit more familiar with it, and that you know how… how to approach that.

F3P21 That video clip that… I really… it made me really enthusiastic! When I saw the video clip. Maybe if everyone sees that they'll then… think: oh.

F2P17 Miscommunication… And that's okay, because there are life lessons in communication.

F3P20 If I… hear P23's story, I'd do it every day! And then also in little things, the way you do it now.

F1P5 That's the great thing about it, isn't it? You just… apply it in… everyday life, just like at your own home… Not just in those moments.

F2P16 And… yeah. This might sound a bit vague, but a bit… a really warm feeling like: Imagine you manage to get this right. What would that mean for those clients, hey? Like how much would they benefit from that if you really… yeah. You managed to get it right.… That you, yeah, if you have enough tools for this and the clients understand it and… can really benefit from it. That could really be such an added value for them. That you really, yeah. They live a lot… in their own little world and when you think about how much the people around you mean to you.. that could really mean a lot to them, really benefit them a whole lot more. Would really be,. Yeah… would be pretty amazing.

Discussion

Results of the Study

The aim of this research project was to collect communication partners' experiences with MPC in conversations with people with CDB. We explored potential contributions of MPC to the observational learning of these people with CDB. Three focus group sessions were conducted with relatives and professionals of people with CDB to address three research questions regarding (1) the operationalization of MPC in relation to conversations with people with CDB, (2) the perceived added value of MPC in addition to dyadic conversations, and (3) required partner competencies to encourage MPC for people with CDB. The responses of participants in the focus group sessions were analyzed and clustered into codes and themes, following the steps of Braun and Clarke (2006). This procedure secured the belief that the breadth of expressions was valued, instead of a predetermination of categorization. The analysis led to a clustering of subthemes related to the research questions. These subthemes, resulting from the analysis, explicate the findings of this study.

Regarding an operational definition, focus group participants mentioned that having MPC is not self-evident for people with CDB. Participants considered involvement of the person with CDB in the conversations as a prerequisite for MPC. This idea implied that a person with CDB both needs to attend to and understand which communication partners are involved, and be enabled to join the conversation. Focus group participants explained that this required communication partners to use means of communication that are familiar to the person with CDB. The majority of focus group participants suggested that MPC is suitable for everyone with CDB provided it is adapted to their personal abilities.

The focus group participants described the significance of MPC for social development, the development of self, and the development of communication skills. Focus group participants believe MPC gives a person with CDB the opportunity to experience group belonging. Additionally, participants explained that MPC may be used to encourage peer interactions. In the focus groups, it was suggested that MPC is important for people with CDB to broaden their world. Focus group participants associated both development of self-confidence and alertness with involvement in MPC. Within the focus group sessions, the following communication skills were thought to develop as a result of MPC: turn-taking, understanding what is being discussed, and the ability to discuss topics within the conversation. Focus group participants explained that MPC involves a relatively high amount of declarative communication. Also, an MPC setting is considered to consist of different structures than dyadic communication. In their experience, MPC expands the vocabulary of the person with CDB.

Participants of the focus group believe that the effects of MPC for people with CDB may be delayed, small, and/or only visible within the situation. Even so, MPC is considered to have added value for people with CDB as long as personal factors and circumstances are taken into account. Focus group participants suggested MPC should be offered much more to people with CDB, preferably by familiar communication partners. In their opinion, these communication partners appreciate the potential utterances of the person with CDB most and are best acquainted with their means of communication. To ensure successful communication, focus group participants suggested lowering the speed and using repetitions within the conversation. Often, the communication partner prepared the MPC by choosing a suitable situation and using systematic repetitions to support the comprehension of the person with CDB.

Critical Reflection

Several focus group participants mentioned that a multiparty situation was only regarded as MPC if the person with CDB participated in the conversation. On the other hand, Clark (1996) stated that MPC includes situations with overhearers who are present, though uninvolved in the conversation. These two viewpoints may appear contradictory, but people with CDB are unable to follow a conversation at a distance, which is different to hearing people. It is interesting to explore the concept of “overhearers” when the overhearers have deafblindness as in the current study, or speak a different language, or when they are small babies. Is this the same as overhearing a conversation that one can hear, follow, and understand? Attention is seen as one of the important elements in observational learning, and learning will at least be fragmentary if the modeled behavior is too complex (Bandura, 1986). Focus group members suggested that a conversation needs adaptations to facilitate comprehension of persons with CDB, which corresponds to Malmgren (2019) and Vervloed et al. (2006), who emphasize adaptations in language and proximity. Since these adaptations are often based on touch, participation in the conversation may be unavoidable in deafblind communication.

A second point on a definition for MPC concerns the understanding of the person with CDB. A focus group participant expressed that the person with CDB should understand the content of the conversation in order to call it an MPC. However, determining comprehension of a person with CDB is a complex task for both researchers and practitioners. It entails reading the often subtle and idiosyncratic expressions of the person with CDB (e.g., Rødbroe and Janssen, 2006; Dalby et al., 2009) and relies on the sensemaking capacities of the communication partner and their shared experiences with the person with CDB (Souriau et al., 2008). An alternative viewpoint is that meaning making is a shared activity within the conversation, which implies that understanding the content relies on the process between the communication partners. Consequently, the person with CDB feels empowered by this shared process of maintaining the negotiation within communication, instead of reaching a state of shared understanding (Nafstad and Rødbroe, 2015). Also Bandura (1986) appointed attention, and not comprehension, as one of the essential elements of learning. In sum, the notion of understanding is complex and needs operationalization when observing communication patterns.

Concerning the execution of MPC, focus group participants said that spontaneous MPC with people with CDB was rare. In their opinion, the sensory impairments of the person with CDB inhibits a natural occurrence of MPC. Focus group participants suggested it needs to be enacted purposefully by their seeing-hearing communication partners. Deafblindness is regarded as one of the most heterogeneous disability groups, due to variances in hearing and vision loss (Bruce et al., 2016; World Federation of the DeafBlind, 2018). Communication partners have a cardinal role in their development by offering individualized interventions, adapted to the personal needs of the person with CDB (Bruce et al., 2016). Such interventions have recently been developed, for instance to stimulate the sharing of emotions (Martens et al., 2017) and high-complex communication (Damen et al., 2017). These interventions, however, focus primarily on dyadic conversations and are not based on observational learning in a multiparty setting. Since no instructions for MPC with people with CDB are currently available, communication partners have developed their personal competence in MPC through practice. Further research should objectify these experiences into guidelines for high quality MPC with people with CDB.

Focus group participants believed communication skills of people with CDB developed by them having MPC. This relates to cognitive development and reflects findings in studies on MPC with typically developing children. Young infants are attentive to others' conversations, both in a triadic setting and in overhearing a dyadic setting (Fivaz-Depeursinge et al., 2010). Children learn new words by listening to others' conversations (Akhtar et al., 2001). Their interest in overhearing human conversation develops in line with their growing understanding of language (Bakker et al., 2011). Barton and Tomasello (1991) found that infants join other people's conversations both if they are invited and spontaneously. In their study, the proportion of triadic joint attention and of triadic conversations increased with age. They hypothesize that multiparty constellations decrease the pressure to reply, which facilitates opportunities to join in. These findings may apply to conversations with people with CDB as well as conversations with young children, but no evidence is yet available.

Regarding social development, focus group participants suggested that peer interactions of people with CDB rarely occur spontaneously. Peer interactions are, in their opinion, constrained by variations in communication strategies, which are often idiosyncratic. Focus group participants expressed that MPC situations, initiated and guided by a seeing-hearing communication partner, might contribute to the occurrence of peer interactions. Peer interactions of children without sensory disabilities occur naturally from birth. As infants they already develop in communities, and are attentive to conversations where other infants are involved (Selby and Bradley, 2003; Ishikawa and Hay, 2006). Peer interactions during the first years contribute to social and cognitive development (Hay et al., 2004). The number of triadic interactions increases during the second year of life, which is associated with children's increasing linguistic skills (Barton and Tomasello, 1991; Tremblay-Leveau and Nadel, 1995). It can therefore be hypothesized that naturally occurring peer interactions of people with CDB are not only inhibited by their sensory impairments but also by their idiosyncratic means of communication. Communication partners could encourage the peer interactions of people with CDB by means of MPC, and act as a moderator of the ongoing discourse.

On the issue of partner competencies, focus group participants expressed that the enactment of MPC was especially challenging in the tactile modality. This can be explained by the fact that communication partners' own natural communicative behavior barely contains tactile communication. In addition, the expressive vocabulary of a person with CDB has a personal nature, as has been exemplified by Bruce et al. (2007). Gregersen (2018) argues that particularly tactile contact gives a person with CDB sufficient information to share experiences. Interventions to increase communication partners' sensitivity to personal means of communication of people with CDB have been implemented (cf. Janssen et al., 2003; Damen et al., 2017; Martens et al., 2017; Bloeming-Wolbrink et al., 2018), but these interventions have not yet been studied in tactile MPC. Focus group participants in the current study remarked that taking additional time and using repetitions in the conversations improved mutual understanding between themselves and the person with CDB. We therefore recommend further analysis of partner competencies for successful tactile MPC in a follow-up study.

Furthermore, focus group participants expressed that confidence of the communication partner increases the chances of successful use of MPC. These impressions about the impact of beliefs are in line with previous research. Beliefs unconsciously influence how people interact with each other (e.g., in childhood practitioners: Kucharczyk et al., 2019) and which outcome a person expects (e.g., in teaching: Hoover-Dempsey et al., 1987). Focus group participants suggested that communication partners of people with CDB can increase their self-efficacy by watching good examples of colleagues, practicing by doing, and discussing their experiences in MPC together. Since expressions of persons with CDB are often small, momentary, and idiosyncratic, coaching often involves video-analysis (Nafstad and Rødbroe, 2015; Damen et al., 2020). In addition, focus group participants appointed modeling and coaching on the job as potential elements of intervention. Further research on the fidelity of the implementation of MPC can objectify these suggestions.

Methodological Considerations

Focus group sessions have a qualitative nature that allows for insights into a certain topic. The use of multiple focus groups has been recommended to ensure revelations of patterns in discussions (Krueger and Casey, 2009). Therefore, the current study consisted of three focus group sessions with experts in the relative small field of CDB. Similar statements were made in two to three different focus group sessions, which demonstrates some level of agreement between participants of different focus groups in this small-scale study. However, consensus was not aimed for. Accordingly, a breadth of opinions was generated due to varying experience of individual focus group participants and context of the sessions. For example, one of the focus groups consisted primarily of school teachers, while caregivers dominated the other two groups. Since the explicit practice of MPC with people with CDB is relatively new in the Netherlands, it can be reasoned that other communication partners in different settings, or increasing experience of the current focus group members, may lead to enriched perspectives in the future. Therefore, we recommend further study be done on the practice and effects of MPC with people with CDB after more experience has been gained.

Ensuring a diversity of participants was effected by the invitation of both professional communication partners and members of the social network, representing different disciplines, different age groups, and diversity in work experience. Two of the participants were family members of a person with CDB. Their input in the discussions might have a different nature than the input of professionals, since they have a different relationship with the person with CDB. A comparison between groups was beyond the scope of this article but may be interesting for future research with different study methods. Females were over-represented in the focus groups, but that is generally the case in care organizations in the Netherlands (VGN, 2019) and is therefore representative of the daily interactions of people with CDB. Altogether, the variability in this study is seen as a representative reflection of the variability in the population.

Reports on qualitative studies, like the current focus group report, should describe issues on the study's rigor, comprehensiveness, and credibility (Tong et al., 2007), which has been done in relevant sections of this report. A limitation of the chosen methodology is that reliability and validity are difficult to establish. Where appropriate, steps were taken to increase transparency, including a check by two independent experts on deafblindness who were not present in the sessions and a reliability check of the analysis by the facilitators of the three focus group sessions. A participant check of the transcripts would have added to the validity (Tong et al., 2007), but it was not undertaken. A potential disadvantage of focus groups is that one or two participants can dominate the discourse. This can result in quick consensus, which may inhibit others from disagreeing. However, in this study, the objective was to gain more insight, and consensus was not aimed for. In the discussions, all participants were vocal and expressed differences in viewpoints more than once. However, the authors suggest future research use alternative methods to discuss the conclusions of the study, contributing to a more solid knowledge base.

Focus groups are an instrument to collect perspectives and experiences. The current focus group sessions aimed to increase the understanding of issues that communication partners experience during MPC with people with CDB. This report reflects potential strategies to implement MPC in this target group and outlined its possible effects. Further research is needed to elaborate on these findings and to measure strategies and effects in practice. For example, the incidence of MPC for people with CDB could be studied and related to studies of the general population.

Conclusion

The information gained from this study brings insight into the opinions of communication partners on operational definition, benefits, and partner competencies of MPC with people with CDB. The responses in the focus group sessions revealed what communication partners of people with CDB think of how, when, and for whom MPC is beneficial. Participants of the focus group sessions were enthusiastic about the potential of MPC but felt unsure about how best to adapt MPC to the personal communicational needs of each person with CDB. Since MPC is not yet common practice in the field of CDB, it can be hypothesized that MPC is a learning experience for all communication partners. In dialogical theory, learning is seen as a dynamic collaborative activity between the communication partners (Linell, 2009; Dufva et al., 2014). From this viewpoint, the communication partner is not the scaffolder of the person with CDB. In fact, both communication partners co-construct the dialog and extend their individual knowledge (Foote, 2018). Therefore, we recommend designing an intervention based on the insights from this study to support communication partners in fostering MPC that includes people with CDB. Additionally, we recommend evaluating the effects of this intervention on the observational learning of people with CDB in an effect study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee for Pedagogical & Educational Sciences (Groningen University). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

MW conceptualized and designed the study, recruited participants, moderated the focus group sessions, analyzed the data to themes and subthemes, and drafted the manuscript, supervised by SD. SD gave methodological support and independently reviewed the analysis. MW, SD, MJ, and AM participated in revision of the draft until agreement of all aspects of the work was obtained and approved the final version to be published. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was funded by the Programmaraad Visueel (grant No. VJ2018-02). The programmaraad visueel was a Dutch fund by VIVIS (Association of institutions for people with a visual impairment).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants of the focus group sessions for their contribution to the knowledge presented here. We also thank Kitty Bloeming, Amanda Buijs, and Ingrid Korenstra for their involvement in the research group. They were second moderators during the focus group sessions and gave their feedback on the analysis. Furthermore, we thank Sietske Molenaar for independently reviewing the data analysis.

References

Akhtar, N., Jipson, J., and Callanan, M. A. (2001). Learning words through overhearing. Child Dev. 72, 416–430. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00287

Bakker, M., Kochukhova, O., and von Hofsten, C. (2011). Development of social perception: a conversation study of 6-, 12- and 36-month-old children. Infant Behav. Dev. 34, 363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2011.03.001

Bandura, A. (1986). Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Retrieved from: https://rug.on.worldcat.org/oclc/781688395

Bandura, A. (1989). “Social cognitive theory,” in Annals of Child Development. Vol. 6. Six Theories of Child Development, ed R. Vasta (Greenwich, CT: JAI Press), 1–60.

Barton, M. E., and Tomasello, M. (1991). Joint attention and conversation in mother-infant-sibling triads. Child Dev. 62, 517–529. doi: 10.2307/1131127

Bloeming-Wolbrink, K. A., Janssen, M. J., Ruijssenaars, W. A. J. J. M., and Riksen-Walraven, J. M. (2018). Effects of an intervention program on interaction and bodily emotional traces in adults with congenital deafblindness and an intellectual disability. J. Deafblind Studies Commun. 4, 39–66. doi: 10.21827/jdbsc.4.31376

Blum-Kulka, S., and Snow, C. E. (2002). Talking to Adults: The Contribution of Multiparty Discourse to Language Acquisition. Mahwah, NJ: Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from: https://rug.on.worldcat.org/oclc/936901868. doi: 10.4324/9781410604149

Boekaerts, M., and Minnaert, A. (1999). Self-regulation with respect to informal learning. Int. J. Educ. Res. 31, 533–544. doi: 10.1016/S0883-0355(99)00020-8

Bradley, B. S., and Selby, J. M. (2004). Observing infants in groups: the clan revisited. Infant Observ. 7, 107–122. doi: 10.1080/13698030408405046

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bruce, S. M., Nelson, C., Perez, A., Stutzman, B., and Barnhill, B. A. (2016). The state of research on communication and literacy in deafblindness. Am. Ann. Deaf 161, 424–443. doi: 10.1353/aad.2016.0035

Bruce, S. M. P. D., Mann, A. M. A., Jones, C. M. A., and Gavin, M. M. A. (2007). Gestures expressed by children who are congenitally deaf-blind: topography, rate, and function. J. Vis. Impair. Blind 101, 637–652. doi: 10.1177/0145482X0710101010

Clark, H. H. (1996). Using Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from: https://rug.on.worldcat.org/oclc/798792608

Correa-Torres, S. M. (2008). The nature of the social experiences of students with deaf-blindness who are educated in inclusive settings. J. Visual Impair. Blind. 102, 272–283. doi: 10.1177/0145482X0810200503

Dalby, D. M., Hirdes, J. P., Stolee, P., Strong, J. G., Poss, J., Tjam, E. Y., et al. (2009). Characteristics of individuals with congenital and acquired deaf-blindness. J. Vis. Impair. Blind 103, 93–102. doi: 10.1177/0145482X0910300208

Damen, S., Janssen, M. J., Ruijssenaars, W. A. J. J. M., and Schuengel, C. (2015). Intersubjectivity effects of the high-quality communication intervention in people with deafblindness. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ. 20, 191–201. doi: 10.1093/deafed/env001

Damen, S., Janssen, M. J., Ruijssenaars, W. A. J. J. M., and Schuengel, C. (2017). Scaffolding the communication of people with congenital deafblindness: an analysis of sequential interaction patterns. Am. Annal. Deaf. 162, 24–33. doi: 10.1353/aad.2017.0012

Damen, S., Prain, M., and Martens, M. (2020). Video-feedback interventions for improving interactions with individuals with congenital deaf blindness: a systematic review. J. Deafblind Stud. Commun. 6, 5–44. doi: 10.21827/jdbsc.6.36191

Dammeyer, J. (2014). Deafblindness: a review of the literature. Scand. J. Public Health 42, 554–562. doi: 10.1177/1403494814544399

Dufva, H., Aro, M., and Suni, M. (2014). Language learning as appropriation: how linguistic resources are recycled and regenerated. AFinLA-e Soveltavan kielitieteen tutkimuksia 6, 20–31. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282816775 (accessed November 12, 2020).

Fivaz-Depeursinge, E. (2008). Infant's triangular communication in “two for one” versus “two against one” family triangles: case illustrations. Infant Ment. Health J. 29, 189–202. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20174

Fivaz-Depeursinge, E., Lavanchy-Scaiola, C., and Favez, N. (2010). The young infant's triangular communication in the family: access to threesome intersubjectivity: conceptual considerations and case illustrations. Psychoanal. Dialog. 20, 125–140. doi: 10.1080/10481881003716214

Foote, C. (2018). Essay. Unpublished Essay MSc Pedagogical Science, Communication and Congenital Deafblindness. Groningen: University of Groningen.

Gräfenhain, M., Behne, T., Carpenter, M., and Tomasello, M. (2009). One-year-olds' understanding of nonverbal gestures directed to a third person. Cogn. Dev. 24, 23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cogdev.2008.10.001

Greene, M. G., and Adelman, R. D. (2013). “Beyond the dyad: communication in triadic (and more) medical encounters,” in The Oxford Handbook of Health Communication, Behavior Change, and Treatment Adherence, eds L. R. Martin and M. R. DiMatteo (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Gregersen, A. (2018). Body with body: interacting with children with congenital deafblindness in the human niche. J. Deafblind Stud. Commun. 4, 67–83. doi: 10.21827/jdbsc.4.31374

Hart, P. (2006). Using imitation with congenitally deafblind adults: establishing meaningful communication partnerships. Infant Child Dev. 15, 263–274. doi: 10.1002/icd.459