- Department of Leadership Studies, College of Education, University of Central Arkansas, Conway, AR, United States

We based our exploratory study on the premise that the role of a K-12 teacher in the classroom is that of a leader. Teachers must identify as leaders to effectively navigate the challenges of teaching and learning. In our research, we developed and validated a tool containing both quantitative and qualitative items to assess the attributes of the leader identity of teachers in the context of their role as a classroom teacher. The responses of the 91 K-12 teachers who participated in our research revealed variations in the levels of leader identity attributes based on individual differences. We found most teachers tended to perceive the primary role of a teacher as a conveyer of knowledge, and yet strongly agreed that teachers are critical role models. We also found a disconnect between why they became teachers and their perceptions of the role of a teacher. Following our results, we interpret our findings, provide associated implications, and offer directions for future research.

Introduction

In the typical K-12 classroom, there is one adult in the room—the teacher. Also, in that room are the students, sometimes more than 40 children per teacher. The teacher is responsible for organizing the students in the room, getting their attention, inspiring them to engage, assuring they are learning, and assessing their progress. The activities of a teacher are those commonly associated with effective leadership, such as inspiring and motivating others, providing a vision for the future, acting as mentors and building community, and implementing a vision (Bennis, 1986). Yet, in our search of the literature, we found that teacher preparation programs do not tend to include a focus on teachers being leaders, and, when leadership is considered in K-12 settings, the focus is on school (or district) administrators and teachers with school-level roles (e.g., instructional coach, department chair) as is detailed in the Teacher Leader Model Standards (Teacher Leadership Exploratory Consortium, 2011). The standards focus on the role of the teacher outside of the classroom, such as mentoring other teachers, instructors at a teacher leadership academy, and facilitating teacher conversations about instructional interventions. Thus, teacher leadership standards are focused almost exclusively on teachers working with colleagues or engaging in leadership roles outside of the classroom.

Missing from the teacher leadership literature (and standards) is empirical evidence detailing the leadership activities and perceptions of teachers in their role as instructors of their students. Thus, while teachers engage in the activities of leaders in the classroom, we are unable to locate empirical studies documenting teachers' identifying as leaders. The lack of empirical research on teacher perceptions of themselves as leaders indicates that teachers (and others, such as teacher educators) may not perceive teaching as a leadership role. We argue there is a need to research the leader identity of teachers in the classroom to understand teacher leadership more fully.

The critical role of leadership to teacher effectiveness for decision making, inspiring others to learn, resolving situations of conflict, and the lack of preparation and recognition of teaching as a leadership position, led us to wonder if teachers hold a leader identity in the context of classroom teacher. Further, we wondered, to what extent do teachers embrace and express attributes of a leader identity as part of their role in the classroom as a teacher? The dearth of empirical studies focused on teachers as classroom leaders indicate that there is a gap in the teacher leadership literature that needs to be addressed.

Review of Literature

Leader Identity

The tasks and expectations of leaders require a range of dispositions, knowledge, and skills (e.g., Spears, 2010). In recognition of the expectations of leaders, scholars such as Day et al. (2012) have posited that there are essential attributes of all leaders which influence individual leader identity. These ubiquitous attributes are fundamental to the extent to which an individual identifies (internally) as a leader (Day et al., 2012). Therefore, leader identity is considered to be the personal internalization of the essential attributes of leaders (Day et al., 2012). The essential attributes of leader identity include leader contextualized self-regulation (Sosik et al., 2002), self-efficacy for leading (Paglis and Green, 2002), self-determination (Eyal and Roth, 2011), implementation intentions (Day, 2000), and resilience and persistence (Stoltz, 2015). If the expression of leader identity attributes is similar to other identities, then the self-identification as a leader is likely to be influenced by context, related to experience, associated with expectations, and shift to align with the perceptions of others (Klenke, 2007). For example, a teacher may perceive herself as a leader in the role of department head, but not as a leader in her role as a classroom teacher. Thus, when examining the leader identity of K-12 teachers, it is critical to take into account their range of roles, their responsibilities, interactions with others, and the setting in which they are leaders.

As with other identities people may hold, leader identity is highly personal and develops with time and experience (Day et al., 2012). The relevance of holding a leader identity, in relation to the extent to which teachers perceive their role in the classroom as a leader, justifies examining the levels to which they hold and express the attributes of leader identity in their roles as classroom teachers. Specifically, we are interested in which leader identity attributes teachers are more likely to perceive they embrace and express, in relation to their classroom practice and teaching role. The potential for teachers to perceive leadership of a teacher in the classroom to be different than leadership outside the classroom justifies examining teachers' leader identity in the context of teaching.

Leader Identity of Teachers

We consider leader identity to be the internalization of an identity of self as a leader (Miscenko et al., 2017). Identity may be self-claimed (which is considered identification) in which one claims an identity without regard to the perspective of others (Stets and Burke, 2000). Identity may also be granted by others (Abrams and Hogg, 1988), as is the case with social identity. People tend to hold multiple identities such as those associated with gender, ethnicity, lifestyle, professional position, relationships, and other personal and professional variables (Josselson and Harway, 2012). Identities may evolve, be gained (e.g., becoming a parent), or lost through time (e.g., no longer being a student).

It is possible for teachers to claim to be a leader based on their perceptions self-validating their identity, or they may be granted the identity as a leader based on the validation of others. The leader identity of teachers is complicated by the potential for holding multiple roles in a school. For example, Wenner and Campbell (2017) consider leadership of teacher to be, “teachers who maintain K−12 classroom-based teaching responsibilities while also taking on leadership responsibilities outside of the classroom” (p. 140), which indicates the identity of leader is granted to teachers. The definition is consistent with the perspective of Hunzicker (2017), who suggests that the leader identity of teachers is a progression resulting from teachers not initially recognizing teaching as a leadership role. Carver (2016) also distinguishes between teaching and leading, indicating that teachers commonly “maintain their identity as a teacher while preparing to be leaders” (p. 169), which may reflect a culture in which teachers are not commonly granted a leader identity in their role of teaching. Danielson (2006) devotes an entire chapter to what teachers do as leaders by claiming, “teacher leaders work as teachers but exercise leadership with their colleagues” (p. 28). Thus, leader identity is granted to teachers when engaging in leadership roles outside of teaching (Wenner and Campbell, 2018). Yet, successful teaching requires the expression of the attributes of a leader to be successful (e.g., motivating others, sharing a vision, team building, etc.), which provides a warrant for examining the leader identity of teachers.

Assessing Leader Identity of Teachers

As discussed previously, the identity one has as a leader is likely to be considered in the context of a specific role (Purvanova and Bono, 2009). The leadership role could involve leading one's life or being a classroom teacher. Regardless of the conditions in which the leading is taking place, the context should be considered when assessing levels of leader identity. Thus, in our consideration of teachers' internalization and expression of the leader identity attributes, we chose to use contexts from classroom teaching. For example, when considering teacher engagement in self-regulation, the consideration might be classroom situations that require high levels of self-control, such as working around classroom interruptions or interacting with a disrespectful student. We would expect a teacher with a well-developed leader identity to navigate these situations as a leader by minimizing the influence of the interruption and moving forward with instruction or defusing the disrespectful student using a non-confrontational or other leader-based approaches.

As an individual develops a leader identity, there are various attributes that they express in the context of leadership. These attributes include self-regulation, self-efficacy, self-determination, implementation intentions (Day et al., 2012), and grit (Duckworth and Gross, 2014). Expression of these attributes by teachers may provide evidence that they are acting and thinking like leaders, regardless of their identification as leaders.

Self-Regulation and Teachers Leading

Self-regulation in leading involves the process of controlling emotions, thoughts, preferences, desires, and attention, in efforts to maximize effectiveness (Ent et al., 2012). The leadership attribute self-regulation in the context of teaching might be associated with controlling emotions when frustrated, adjusting the desire to move forward with instruction when students have not mastered the necessary prerequisite content, or limiting assumptions about under-performing students. Based on our premise that teaching is a leadership role, there is justification for examining teacher engagement in self-regulation in the context of teaching, to assess their leader identity.

Self-Efficacy and Teachers Leading

Self-efficacy is “beliefs in one's capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to manage prospective situations” (Bandura, 1995, p. 2). Murphy and Johnson (2016) argue self-efficacy is critical for identifying as a leader, by recognizing the potential for beliefs in one's ability to fulfill the responsibilities of a leader. Murphy and Ensher (1999) claim that leader self-efficacy (alternatively—leader efficacy) is an estimate of the leader's ability to complete a leadership task. For teachers, self-efficacy for leading may be an estimate of their ability to create and maintain positive learning climates in classes, a goal that requires the application of well-developed leadership skills.

A gap in the literature is in the leadership self-efficacy of teachers. Scholars have not researched (or recognized) the leader self-efficacy of teachers, yet teachers engage in leadership roles as they lead their students in learning. Scholars of teacher self-efficacy have researched teaching a particular subject (Nadelson et al., 2013), classroom management and discipline (Brouwers and Tomic, 2000), student engagement (Martin et al., 2012) using technology in the classroom (Bellibas and Liu, 2017; Cansoy et al., 2018), and interpersonal relations with students (Veldman et al., 2017). While the existing studies of teacher self-efficacy do not include leadership, the research provides models for assessing self-efficacy in different contexts of teaching.

Bandura (2012) argues self-efficacy is situational and domain-dependent and, therefore, measures of self-efficacy should be constructed in alignment with the audience and task. When assessing the leader identity of teachers, it is critical to evaluate their leadership self-efficacy using the context of teaching and tasks that require leadership. The association between self-efficacy and leader identity justifies including self-efficacy for leading as a critical attribute of the leader identity of teachers.

Self-Determination and Teachers Leading

Ryan and Deci (2017) define self-determination as an empirically based theory of human motivation, development, and wellness. Self-determination in leadership is expressed when making decisions and engaging in the associated activities to achieve professional goals. A teacher with a leader identity may express the attribute of self-determination as the motivation to try new instructional approaches in situations of unknown outcomes.

Much research on self-determination in educational settings has focused on teacher influence on student development of self-determination, rather than teacher expression of the construct (e.g., Reeve, 2002; Perlman and Pearson, 2012). Taylor and Ntoumanis (2007) assessed teachers' level of self-determination, but with respect to their influence on students and not in relation to their leader identity. Although teacher self-determination plays a significant role in classroom teaching and in leadership, there is scant research on associated with the leader identity of teachers. Due to the importance and the lack of research on teacher engagement in the leader identity attribute of self-determination in the context of teaching, there is justification for considering self-determination as a critical attribute of the leader identity of teachers.

Implementation Intentions and Teachers Leading

Gollwitzer and Sheeran (2006) define implementation intentions as desires or visions of the actions needed to achieve goals or shield goals from distractions. Implementation intentions is an attribute of leader identity as leadership requires planning and setting goals (Day et al., 2009). We consider implementation intentions in the context of teaching as leading to be the desire, willingness, and commitment to take actions to facilitate student learning. Implementation intentions are critical for teachers' success as they plan for student learning, work to help students meet learning objectives, and support student learning progression. We were unable to locate any empirical reports documenting the implementation intentions of teachers associated with their leader identity in the context of their classroom teaching. Because of the importance of implementation intentions to effective leadership, teaching, and identifying as a leader, there is justification for assessing the attribute when documenting the leader identity of teachers.

Grit and Teachers Leading

Grit is defined as the “perseverance and passion for long term goals” (Duckworth et al., 2007, p. 1087). Individuals with a high level of grit are more likely to succeed (Duckworth and Gross, 2014). Grit has been documented to be as crucial to success as talent and intelligence (Laursen, 2015). Davidson (2014) found an association between leadership behaviors and grit, validating the relationship between leadership and grit. Schimschal and Lomas (2019) report grit as accounting for variance in positive leadership. The association between grit and leadership activities suggests grit is likely an essential attribute associated with leader identity.

Grit has also been found to be a significant predictor of teacher effectiveness (Duckworth et al., 2009). Gritty teachers successfully sustain their careers because they can persevere through the many challenges of teaching. We recognize that teachers may have grit but lack a leader identity, but it would be doubtful for teachers to identify as leaders and not have grit. Because of the association between grit and effective leadership, there is justification for including grit in the assessment of the leader identity of teachers.

Teachers' Perceptions of Leadership in the School

As we discussed previously, current research tends to separate teaching from leadership, conveying the likelihood that researchers and the education community do not perceive teaching to be a leadership activity. For example, Smulyan (2016) advocates for teacher leader preparation as a holistic process instead of as a set of prescribed behaviors; however, the focus is on preparing teachers for leadership opportunities outside of the classroom. The prospect that there is a general separation of leadership and teaching, despite the substantial leadership skills required for teaching, motivated us to explore teachers' perceptions of leadership in the school. We were particularly interested in assessing qualities perceived as necessary for one to be identified as a leader in the school as well as teachers' perceptions of the activities they engage in while teaching and if they recognize and perceive the actions as leadership.

Leaders as Role Models

Leaders explicitly or implicitly influence others (Yukl, 2002). Leaders by role, title, or action are perceived as role models (Schein, 1985) influencing the behaviors, ethical and moral perspectives, and priorities of those they lead. Through role-modeling, leaders influence the culture of an organization and the values of those within the organization (Sims and Brinkman, 2002). Sims and Brinkman (2002) argue that followers in organizations emulate the behaviors, actions, and priorities of their leaders, taking cues from the leader for expectations and norms for the organization. From the perspective of social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986), followers observe the behaviors that their leaders model to determine expectations and acceptable actions within organizations. Thus, it is through social interactions that leaders model expectations for others.

Given the role of teachers as leaders of learning, there is logic in considering them as role models to their students. By acting as role models, teachers influence the morality, work ethic, citizenship, and character of their students (Lumpkin, 2008). Given that leadership is the process of influencing others, and that teaching is the process of influencing students' desire and engagement in learning, teachers are in positions of role models. However, we were not able to find any studies associating teachers' perceptions of themselves as role models in conjunction with their leader identity. Our research addressed this gap by assessing teachers' perceptions of being a role model and their self-identifying as leaders.

Method

The goal of our research was to explore to what extent teachers hold a leader identity, and what are teachers' perceptions of leadership in schools? To accomplish our goal, we created the following guiding research questions:

• How do teachers perceive leadership within the school?

• What is the relationship between teachers' expression of leader identity and other personal and professional characteristics?

• What is the relationship among attributes of leader identity held by the participants?

• What are the primary attributes of leader identity that teachers naturally communicate?

• To what extent do teachers perceive their role in the classroom as that of a leader?

Participants

We recruited our participants from a region in the southern United States through the distribution of an email to teachers through their school district administrators and to K-12 educator listservs inviting the teachers to participate in our research. There were 91 K-12 teachers who participated in our study and fully completed our survey. It is important to note our approach to recruiting study participants (e.g., through listservs and relying on district administrators to distribute our email invitation to participate) constrained our ability to determine how many K-12 teachers we contacted in our recruitment process. The participants were on average 49.39 years old (SD = 9.88) and had been teaching an average of 18.41 years (SD = 9.67). Females made up 83% of our sample and males 17%. The ethnicity of the participants was predominantly Caucasian (85.6%), followed by African Americans (6.6%), Hispanic (4.4%), Asian (2.2%), and other (1.1%). One participant declined to share an ethnicity. The majority of the participants worked in rural schools (58%), followed by urban (23%) and suburban (17%), with two participants declining to share their school community. Just four of the participants indicated that their school had <25% of students qualifying for free and reduced lunch, with 13 participants indicating that between 25 and 50% of the students qualified for free and reduced lunch, and the majority (63 participants) indicating that more than 50% of the students eligible for free and reduced lunch, with 11 participants indicating they did not know the percentage of students qualifying for free and reduced lunch. About 39% of the teachers taught at the high school level, followed by 17% in K-12 schools, 15% at the elementary or middle school level, 4% in grade 6–12 schools, and 10% selected “other” for their school type. About half of the participants (49.5%) indicated that they held a graduate certificate, 17% held a bachelor's degree, 15.5% had some graduate work, 10% held a master's degree, 6% indicated they held a doctorate, 1% held an educational specialist certificate, and 1% indicated an “other” level of education.

Research Design

For our research, we selected a cross-sectional design, surveying teachers in a southern region of the United States as a convenience sample. We recognized the limitations of survey research such as sampling bias, item interpretation, and participant completion, yet, these issues can persist in other forms of data collection as well (Coughlan et al., 2009). Given the exploratory nature of our research, we determined using a survey to collect data would provide a foundational understanding that is necessary for future research.

Survey Development

Given the exploratory nature of our research, we were not able to find any extant instruments aligned with teacher leader identity, particularly as associated with teacher work and leadership in the classroom. Thus, we determined it was necessary for us to create a tool that could effectively assess teachers' leadership identity in K-12 teachers, specifically with respect to their work with students as teachers in the classroom. Using the framework of Day et al. (2009), we identified the key attributes of leader identity, and based on the work of Duckworth et al. (2007), we included grit as an additional key leader identity attribute.

Specifically, we decided to align our survey items with the leader attributes of self-regulation (SR), self-efficacy (SE), self-determination (SD), implementation intentions (II), and grit (GR). Also, we determined that there was value in developing items aligned with teachers' perceptions and knowledge of leadership. Following our identification of attributes, we created a pool of at least five selected-response items for each of the leader identity attributes. As part of our development, we contextualized the items for classroom teaching. To ensure variety, we developed both positively and negatively phrased quantitative items to be answered using a Likert scale.

Our items included prompts such as, “I can motivate all my students to learn, even those who show low interest in schoolwork,” which reflects both leadership and self-efficacy. The item, “I do not like to vary the way I organize my lessons,” is reflective of both leadership in adapting to the needs of others and the self-determination (motivation) to initiate change. The item, “Teachers are critical role models for their students,” is aligned with perceptions and knowledge of leadership. The instruction for the items was to select the response that reflected how much they agreed (or disagreed) with each item on a five-point Likert scale.

In addition to the selected response items, we also developed several free-response qualitative items to use as general prompts to elicit responses that we could code for attributes of leader identity. Our goal was to provide prompts that were likely to catalyze the participants to share thoughts that included leader identity attributes, without priming the response with prompts that may have led the teachers to share perspectives that were not necessarily part of their leader identity mindset. The two free-response prompts we included in our final survey were, “Briefly share why you teach:” and “What is the primary role of a teacher?” for which we allowed unlimited space for the participants to provide their responses.

Once we developed our draft survey, we sought to validate the measure. We shared our survey with multiple scholars with experience in teacher education and leadership studies. We had five of the scholars respond to our request to review our survey. Their responses indicated that they perceived the survey as valid and likely to be useful for measuring teacher leader identity. We made changes to our survey based on the feedback of the experts.

The final survey had eleven demographic items, two free-response items, and 32 leadership selected-response items. We calculated the reliability for the instrument to have a Cronbach's alpha of 0.77, indicating an acceptable level of internal consistency.

Data Collection

Our data collection took place online using a survey portal. We distributed an email containing a brief description of our study and a link to our survey to K-12 teachers associated with a regional professional development center, education listservs, and school districts where we had received permission to collect data. In addition, we asked all participants to share the survey with others who also may be willing to participate. We collected data over 3 weeks in the middle of the spring semester of 2019. Due to the nature of our data collection, we are uncertain how many teachers received the invitation.

Analysis

Quantitative Data Analysis

We began the analysis of the quantitative data by removing from the sample the responses of the participants who had not completed at least 90% of the items. We then used the “replace missing values with series mean” feature in SPSS to fill in the skipped items. Following the assurance of a conditioned data set, we reverse coded our negatively phrased items. Using the conditioned data set, we calculated the reliability (Cronbach's alpha) and created average composite scores for each of our leader identity sub-scales. In our analysis, we calculated a combination of descriptive statistics such as means, standard deviations, and correlations as well as inferential statistics such as T-tests (for 2 level factors) and ANOVA (for factors of 3 or more).

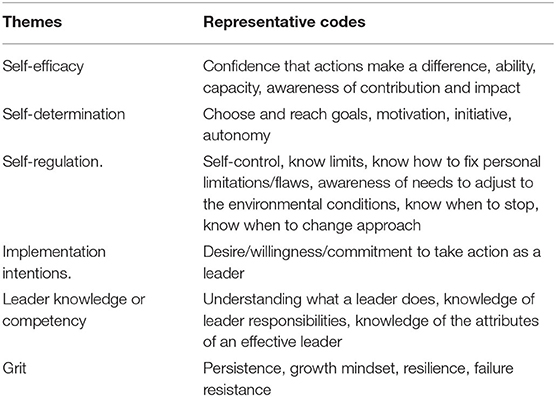

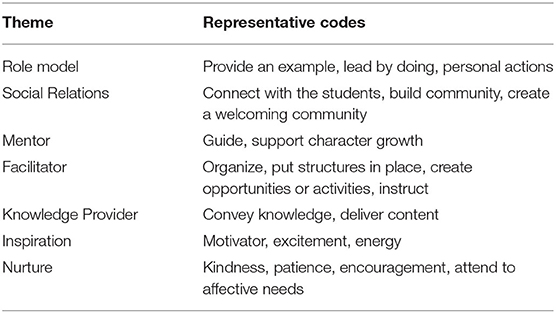

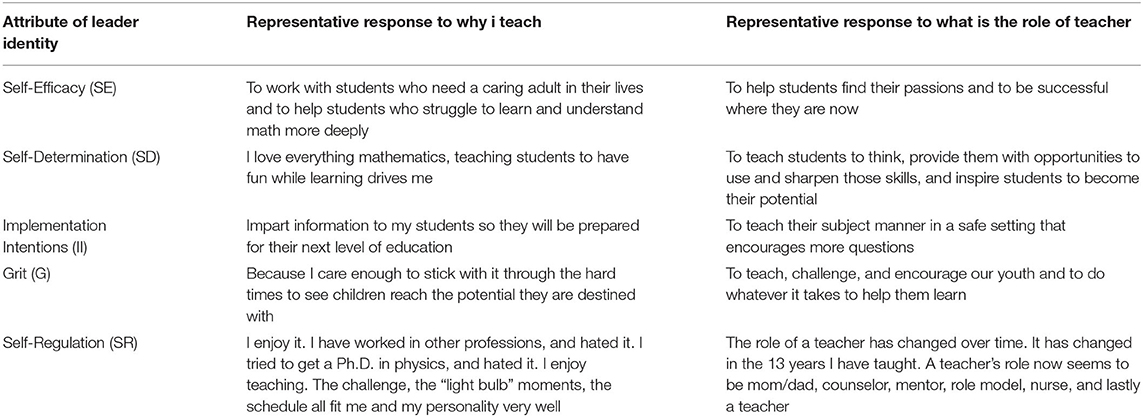

Qualitative Data Analysis

To guide our analysis of the qualitative items, we created a list of representative codes associated with the attributes we identified and detailed in our review of literature as being essential for the leader identity of teachers (see Table 1). In addition to the attributes, we created a set of themes and representative codes reflective of the potential role of teachers (see Table 2), based on the work of educators with students in an instructional setting.

Coding

We began our coding process as a group, with all team members contributing to the discussion of coding the first 15 qualitative responses. Following the group experience, two team members were assigned to code the remaining set of items independently. Once the independent coding was complete, we met as a team and reviewed our independent analyses, and through discussion, we came to a consensus in the coding analysis. We report the outcome of our coding analysis as we address our research questions in our results.

Results

Perceptions of Leadership in the School

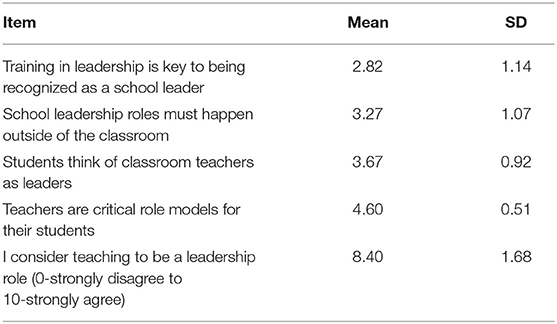

Our first guiding research question asked, “How do teachers perceive leadership within the school?” To answer this question, we examined the mean responses of the teachers to our selected-response items aligned with perceptions of leadership (see Table 3). Our analysis revealed that participants were neutral (M = 2.83, SD = 1.14) in their perceptions of leadership requiring training, indicating a lack of commitment to either “to be a leader one needs training or does not need training” to be recognized as a leader. The participants were more positive (M = 3.27, SD = 1.07) in their perceptions of school leadership roles needing to take place outside of the classroom, indicating a slight lean toward agreeing that leadership roles in schools are exclusive to activities outside of the classroom. In contrast, the participants leaned toward agreeing (M = 3.67, SD = 0.92) that students think of teachers as leaders. Similarly, the participants leaned toward strongly agreeing (M = 4.60, SD = 0.51) that teachers are role models (arguably a leadership role) for their students. On the 10-point slider scale, the teachers leaned toward strongly agreeing (M = 8.40, SD = 1.68) in their consideration of teaching as a leadership role, indicating that teachers tend to perceive their role as that of a leader.

Leader Identity and Individual Differences

Our second guiding research question asked, “What is the relationship between teacher levels of leader identity and their roles, responsibilities, and school structure?” To answer this question, we examined the composite scores for our leader identity attributes and the item asking participants if they consider teaching to be a leadership role and compared the values to the teachers' personal and professional characteristics (such as school type and community description). Our results revealed that there were no differences in the levels of leader identity attributes composite scores or perceptions of teachers as leaders with respect to: gender; the number of students in the school; whether the participant was involved in a leadership role in the school outside the classroom (e.g., coach, club sponsor), the percentage of students eligible for free and reduced lunch; or ethnicity.

We did find multiple differences in leader identity attributes or perceptions of teachers as leaders based on other factors. We found a significant positive correlation between years of teaching and self-determination composite scores (r = 0.32, p < 0.01), which indicates that, as years of teaching increase, so does self-determination in relationship to teacher leader identity.

Using the community type of the participants as a factor, we conducted an ANOVA and found differences in levels of leader grit [F(2, 86) = 5.19, p < 0.01], implementation intentions [F(2, 86) = 4.91, p < 0.01], and in perceptions of teaching as a leadership role [F(2, 86) = 10.41, p < 0.01]. Our post hoc analysis revealed the differences in leader grit were between urban (n = 21, M = 3.44, SD = 0.48) and rural teachers (n = 53, M = 3.15, SD = 0.46) and urban and suburban teachers (n = 15, M = 2.97, SD = 0.39), which indicates the leader grit level of teachers working in urban communities are higher than teachers working in suburban and rural communities. The post hoc analysis on the implementation intentions revealed a difference between urban (M = 4.02, SD = 0.39) and suburban teachers (M = 3.59, SD = 0.40), which indicates that teachers in urban environments hold higher levels of implementation intentions than teachers in suburban environments. Our post hoc analysis of the perceptions of teaching as a leadership position revealed suburban community teachers (M = 6.73, SD = 2.06) held significantly lower perceptions than teachers working in urban communities (M = 8.75, SD = 1.21) and teachers working in rural communities (M = 8.75, SD = 1.69). Our results indicate that the community type that a teacher works in may be a factor in the development of a leader identity.

In an independent samples t-test, we found teachers at the high school level (n =35, M = 3.39, SD = 0.49) had significantly lower levels of leader identity self-efficacy [t(48) = 3.15, p < 0.01] than teachers teaching in K-12 (n = 15, M = 3.87, SD = 0.51). Similarly we found teachers at the high school level (M = 7.94, SD = 1.73) had significantly lower levels of perceptions of teaching as a leadership role [t(48) = 2.44, p = 0.02] than teachers teaching in K-12 (M = 9.13, SD = 1.13). Our finding indicates that the type of school that teachers work in may be a predictor of their levels of leader identity.

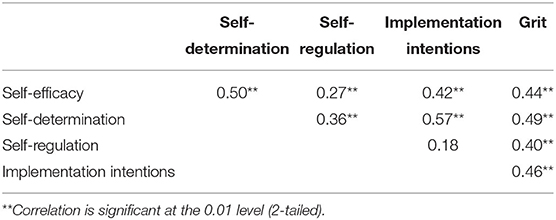

Connections Among Leader Identity Attributes

Our third guiding research question asked, “What is the relationship among attributes of leader identity held by the participants?” To answer this question, we examined the teachers' composite scores for our selected attributes of leader identity. Our analysis revealed nearly all the attributes of teacher leader identity to be significantly correlated at the p < 0.01 significance level (see Table 4). The one exception was between implementation intentions and self-regulation, which we found not to be significantly related. The correlations we found to be significant were between r = 0.27 and r = 0.57 which indicates the items are related but not overly correlated. Our results suggest that there are relationships among the attributes that we determined are representative of a leader identity.

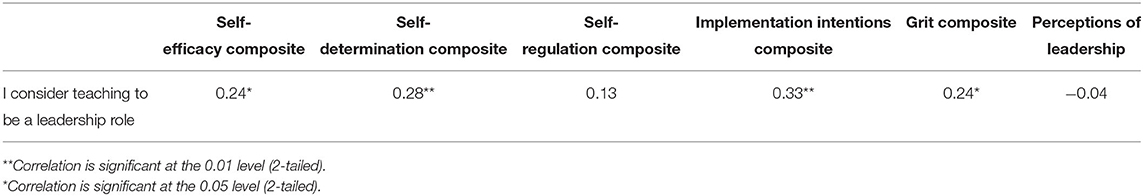

As we continued to explore the relationships among the attributes of leader identity, we calculated the correlations between the level to which the participants consider teaching to be a leadership role and the attributes of leader identity, as well as the composite score of knowledge and perceptions of leadership (see Table 5). Our analysis revealed the level to which teachers perceive teaching as a leadership role was correlated with self-determination and implementation intentions at p < 0.01. We found self-efficacy and grit to be correlated with the teachers perceiving teaching as a leadership role at the p < 0.05 level. Our analysis failed to reveal a significant relationship (p > 0.05) between the level to which teachers perceive teaching as a leadership role and self-regulation as well as the composite score for knowledge and perceptions of leadership. Our results indicate that perceptions of teaching as a leadership role do not correlate with knowledge and perceptions of leadership, indicating the teachers' perceptions of leadership are not aligned with their consideration of teaching as a leadership role.

Table 5. Correlations Among Attributes, Perceptions of Leadership, and Consideration of Teacher as a Leadership Role.

Primary Attributes of Teacher Leader Identity

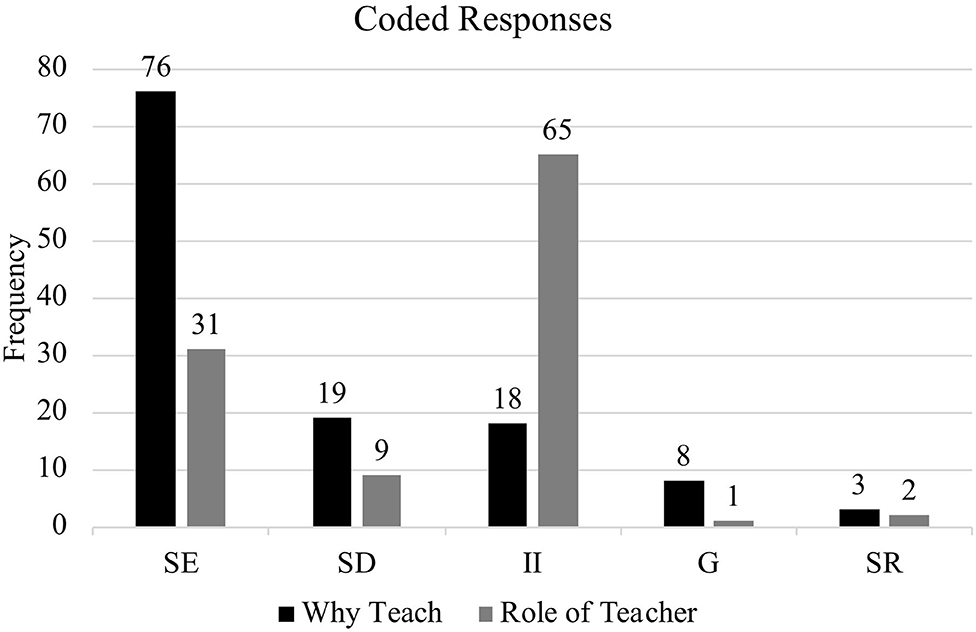

Our fourth guiding research question asked, “What are the primary attributes of leader identity that teachers naturally communicate?” To answer this question, we examined the coded theme of the teachers' free-response narratives to why they teach and the role of a teacher. Our analysis revealed differences in emphasis on leader identity attributes based on the question the participants answered. When answering the question asking them why they teach, the participants tended to focus primarily on instructional effectiveness, which we associated with the leader identity attributes of self-efficacy (see Figure 1). The secondary foci conveyed by the participants were issues of covering the required curriculum and conveying knowledge, which we associated with the leader identity attributes of self-determination and implementation intentions. The attribute of grit, such as persisting through conditions of adversity, and the attribute of self-regulation, such as changing an instructional approach when a method is ineffective, were shared at a very low level.

In contrast, our analysis of the participants' responses to our item asking them what is the role of a teacher revealed a high focus on teachers as conveyers of knowledge and on covering required curriculum, which we associated with the leader identity attributes of implementation intentions (see Figure 1).

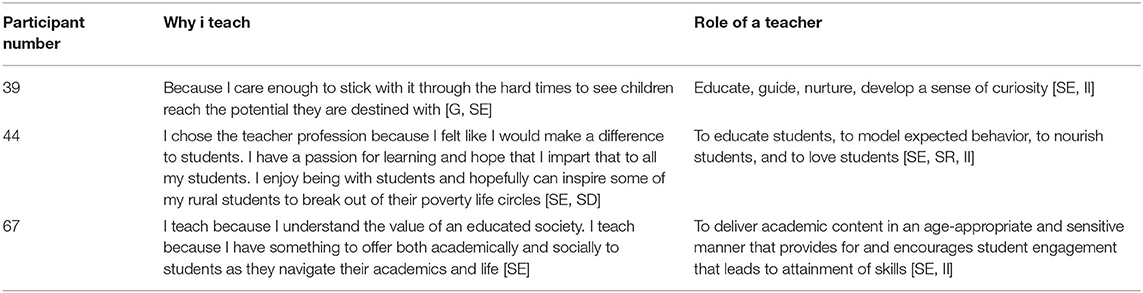

In Table 6, we provide the responses to our two qualitative items, why I teach, and, what is the role of a teacher, for a sample of our participants. Our analysis revealed that the participants had very little overlap in their responses, which suggests that they perceive the explanation for why they teach to be different than the role of a teacher.

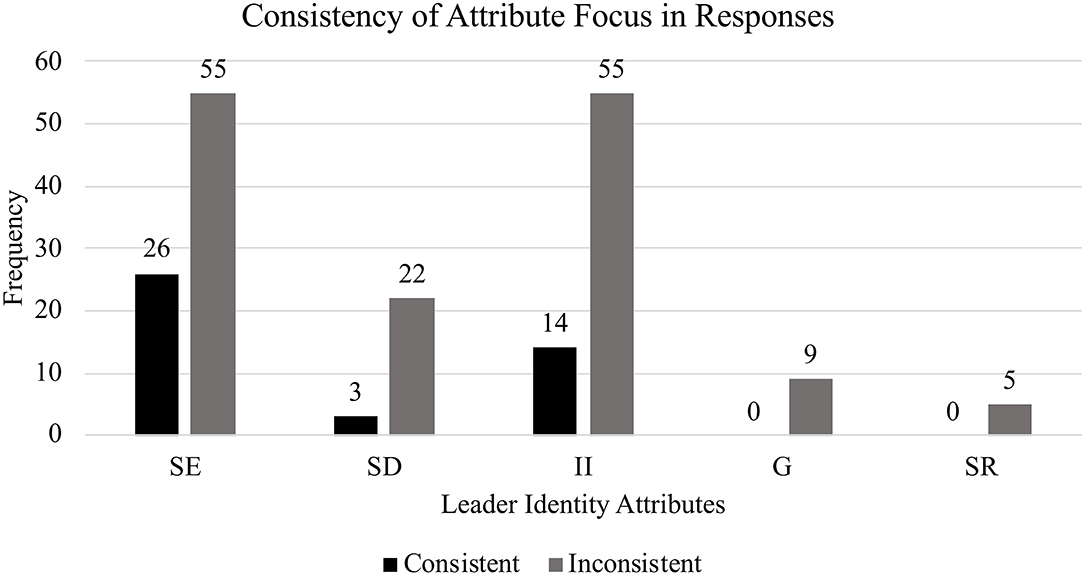

In Figure 2, we present our comparison of communication of leader identity attributes between the two free-response items. The figure includes the consistent communication or lack of consistent communication of the participants by attribute. Our analysis revealed considerable inconsistency between the leader identity attributes communicated when the participants shared why they teach when compared to their explanations of the role of a teacher. Our results indicate the participants tended to see their role as a teacher through a different leader identity lens than the lens they applied when describing why they teach. Thus, the evidence reflects an under-developed or fragmented leader identity.

Figure 2. Consistency in the communication of our leader identity attributes in the responses between our two free-response items.

In Table 7, we present the qualitative answers provided by several participants to free-response items. Note, even with the consistency in the communication of the attributes, the context or activities communicated are inconsistent. The data again indicates that the teachers are likely viewing why they teach and the role of the teacher through different lenses, and not consistently through a lens of a developed leader identity.

Table 7. Responses from the same participant to our two free response items with attribute alignment.

Role as a Classroom Leader

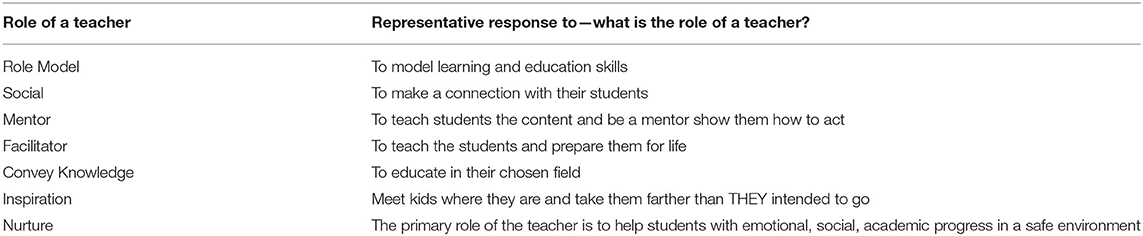

Our fifth guiding research question asked, “To what extent do teachers perceive their role in the classroom as that of a leader?” To answer this question, we examined the coded theme of the teachers' free-response narratives to our item asking them to share the role of a teacher (see Table 8 for codes and example responses).

Our analysis revealed the majority of the teachers perceived the role of a teacher to be either as a conveyer of knowledge or as a facilitator (see Figure 3). At a moderate to low level of frequency, a smaller percentage of responses reflected the role to be one of nurturing, inspiring, or acting as a role model. At a low level, some participants indicated the role as being that of a mentor or social organizer. We interpret the results to suggest that teachers tend to be content and process-based, which may reflect a perspective of teachers as managers, rather than being based on organizational structure, which would reflect teachers as leaders.

Figure 3. Frequencies of the different roles of teachers reflected in the participants' responses to share the primary role of a teacher.

Discussion and Implications

The goal of our exploratory study was to begin to gain an understanding of the leader identity of teachers in the context of their work in the classroom with their students. We sought to determine the level to which teachers embrace the primary attributes of leader identity in the context of their role as a classroom teacher. There is considerable literature about teacher leaders (e.g., Crowther et al., 2009); however, the focus of this body of research is developing teachers as leaders outside of the classroom, and with peers, administrators, and community members. We maintain that teacher effectiveness requires teachers to develop and express a leader identity in their work as teachers of students. Thus, there is a need to explore the level to which teachers perceive their role in the classroom as that of a leader and the extent to which they hold a leader identity associated with their instructional activities.

In our examination of the perceptions of leadership, we found the teachers were moderate on several aspects of leadership but indicated they strongly perceive they are critical role models. Further, we found the teachers tended to perceive teaching as a leadership role. Yet, in their free-response communication of the role of a teacher, the participants rarely communicated teachers serving as role models. We speculate that teachers may see themselves as role models, but do not consider being a role model essential for teaching. It may also be possible that teachers are projecting their extra-curricular activities when considering being a role model and are not necessarily using the context of classroom teaching as the context for consideration of themselves as role models. Exploring teacher perceptions of teachers as role models as classroom teachers is a much-needed direction for future research. The implications of teachers not perceiving themselves as role models in classroom teaching is that they may not adapt or express a leadership role in their teaching. The lack of internalization of the perceptions of being a role model in the role of classroom teacher may limit the ability for teachers to develop their leader identity in the context of teaching.

Leader Identity and Individual Differences

Our examinations of the relationship between teacher levels of leader identity and their roles, responsibilities, and school structure revealed few significant differences between groups. We did find that teachers with more years of teaching expressing higher levels of self-determination, which may be due to self-determination being a critical attribute of the professional retention of teacher. Those who are motivated to stay in the profession over time may develop a strong sense of self-determination, while those with low self-determination may be more likely to experience burnout and change professions and, therefore, would not likely be part of the population of teachers with many years of experience. An implication for our finding is the potential for enhancing teacher self-determination may enhance their retention in the profession. Enhancing teacher self-determination may be accomplished by helping them develop a paradigm of teaching as leading, granting them a leader identity of which self-determination is an attribute.

Our analysis revealed the community type a teacher works within is likely to be predictive of their development of a leader identity. The difference in the levels of the teachers' leader identity may suggest that specific challenges of teaching in an urban school have led teachers to become more intentional and, therefore, aware of leader aspects of implementation intentions. These same challenges have created an environment where grit is a necessity. These challenges may involve classroom management issues. Regardless, the importance of grit and implementation intentions to effective teaching provides additional support for granting teachers a leader identity.

Another finding is that the type of school may influence teacher development of a leader identity, which may be explained by the possibility that K-12 schools in rural communities are generally smaller. Given the smaller community and school, it is likely that teachers are perceived as leaders in and out of school and transfer that perception to their work as classroom teachers; this contributes to a higher level of leader identity. At the high school level, perhaps teachers are more concerned with transferring knowledge adequately so that students can graduate and be successful post-graduation. The focus on the transfer of knowledge is likely to reduce space for perceptions of teachers as leaders. The differences in levels suggest the potential for community differences in granting leader identity to teachers. Future research should further explore the differences in leader identity of teachers in different types of communities and school types.

Connections Among Leader Identity Attributes

With one exception, we found all the teacher leader identity attribute composite scores to be significantly correlated. We posit that the significant correlations were due to the parallel expression of leader identity attributes, indicating when teachers express an attribute, they are likely to express others as well. Our results provide empirical support for the model speculated by Day et al. (2012). We are perplexed by the lack of significant correlations between self-regulation and implementation intentions, particularly given the potential need to adjust an approach (e.g., self-regulate) if there is evidence that indicates desired intentions to implement become unrealistic. An implication for our findings is that teachers may need formal professional development focused on the attributes of leader identity to assure they are prepared to express the attributes in alignments with their roles as classroom leaders.

The mixed results of the correlations among perceptions of teaching as a leadership role and the attributes of leader identity suggest that teachers may not be applying their leader identity attributes to their role as an instructor. We speculate that many of the participants may apply the attributes but do not perceive these as traits or actions of leaders, but rather useful for the process of conveying knowledge and managing classrooms. It may also be possible that those who do perceive teaching as a leadership role may not express the attributes or may consider alternative actions or traits as being indicative of leadership (e.g., being authoritative). Exploring teacher expression of leader identity attributes and their perceptions of the critical qualities of a leader is an excellent direction for future research.

Primary Attributes of Teacher Leader Identity

We attempted to connect the attributes of leader identity from the literature and contextualize them for K-12 teachers. We found that the participants had varying levels of focus or that emphasis on the attributes varied in nature, focusing almost exclusively on the attributes of self-efficacy and implementation intentions. We speculate that teachers may associate being a teacher as a leadership role (as when answering why do you teach). In contrast, teachers likely do not perceive the process of doing teaching as an act of leadership (as when explaining what is the role of the teacher). The context of teachers' expression of attributes of leader identity is further supported by our data that reflects a lack of consistency between the responses to our two free-response items. We posit that teachers teach for personal reasons (internalized as part of their identity); however, teachers may perceive the role or work of a teacher as being more task-oriented and subject to systemic constraints, leading to the adoption and expression of different leader identity attributes. To support the development of stable leader identity attributes in teachers, specifically within the context of classroom teaching, teachers may need to be exposed to conditions or professional development that shift the current paradigm of teacher leadership. The teachers may also experience shifts in their leader identity if they are explicitly granted the identity of being a leader. Our data may also reflect the historical development of teaching as the process of transmitting knowledge, as with lectures. It may be possible that teachers who embrace and engage in more constructivist approaches may hold very different views of teachers as leaders, and therefore express the attributes more consistently. Exploring the leader identity of teachers based on their philosophy of learning and engagement in teaching (e.g., traditional vs. constructivist) is likely to be a fruitful line of research.

Perceptions of Role of Teachers

We found that teachers agree to strongly agree that teachers are role models, and yet when asked to share what they think is the primary role of a teacher, they tended to focus on conveying knowledge or managing learning. The participants seldom shared perceptions of the role of teachers to be that of a leader, with moderate to little mention of roles associated with leadership. We speculate that the teachers' focus on management and knowledge delivery suggests that their perceptions of their role as a teacher is fragmented and only partially reflective of the potential influence of a leader. Our results also indicate that teachers likely hold multiple and competing identities, and their leader identity is potentially overshadowed by other more dominant identities, such as that of being an expert (e.g., Burn, 2007). Again, an implication of our findings is the potential need for formal professional development for teachers in leadership that is aligned with their role as classroom leaders.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

One of the limitations of our research is our sample size. While the sample was diverse and likely representative of K-12 teachers in the region, there may be other perspectives from other groups of teachers, particularly those working in different environments, that are not represented in our study. Also, we removed the responses of the participants who did not complete at least 90% of the survey, which may also have limited the diversity of our sample. Examining the leader identity of different groups of teachers to gain an empirical understanding from a diversity of perspectives is an excellent direction for research.

The second limitation of our research is similar to our first. We collected data from teachers in the same region of the United States. Because of the limited distribution of our survey, we may have captured data that is reflective of the region, as there may be cultural, societal, and legislative nuances that influence the teachers' perceptions and engagement in leader identity attributes. Gathering data in other locations, regions, or cultures would allow us to determine if our findings are unique to this region or aligned with perceptions and practices of teachers more generally.

A third limitation of our study was in the nature of our data collection, which we deemed appropriate given the exploratory nature of our investigation. Although our survey was reliable and was validated, the use of the survey for collecting the data did not allow us to follow up with the participants with additional questions to gain clarity or more in-depth understanding of their perceptions in association with their responses. Further, as we shared previously, survey research is prone to sample bias, issues of representation, and concerns of accurate responses (Coughlan et al., 2009). As we move forward with our research, we plan to use our baseline data and conduct interviews with focus groups of teachers to get more in-depth explanations for our findings.

Conclusion

The goal of our exploratory research was to investigate the leader identity of teachers in the context of their roles as classroom teachers. Outside of classroom teaching, it is commonly accepted that people rely on leaders and mentors to support their learning and intellectual growth to improve professionally (and personally), as is the case with instructional coaches. However, within the classroom, engaging as a teacher to enhance their students' learning and intellectual growth, teachers seldom perceive themselves to be in a leadership role.

We argue teacher recognition of and engagement in leadership in their role as a classroom teacher is essential for being highly effective at addressing the societal and organizational challenges associated with learning and student success. Through our research, we exposed a range of relationships, perceptions, and practices that could be used to create a baseline for understanding teacher leader identity. We will build upon the baseline we have established as we continue to explore how teachers develop and express a leader identity in their role as classroom teachers.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by UCA Institutional Review Board. The ethics committee waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation.

Author Contributions

LN led the research, with LB and MT, both contributing to the reporting of results and analysis of data. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Abrams, D., and Hogg, M. A. (1988). Comments on the motivational status of self-esteem in social identity and intergroup discrimination. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 18, 317–334. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420180403

Bandura, A. (1986). The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J. Social Clin. Psychol. 4, 359–373.

Bandura, A. (2012). On the functional properties of perceived self-efficacy revisited. J. Manag. 38, 9–44. doi: 10.1177/0149206311410606

Bellibas, M. S., and Liu, Y. (2017). Multilevel analysis of the relationship between principals' perceived practices of instructional leadership and teachers' self-efficacy perceptions. J. Educ. Admin. Armidale 55, 49–69. doi: 10.1108/JEA-12-2015-0116

Bennis, W. (1986). “Transformative power and leadership,” in Leadership and Organizational Culture, eds T. J. Sergiovanni and J. E. Corbally (University of Illinois Press), 64–71.

Brouwers, A., and Tomic, W. (2000). A longitudinal study of teacher burnout and perceived self-efficacy in classroom management. Teach. Teach. Educ. 16, 239–253. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(99)00057-8

Burn, K. (2007). Professional knowledge and identity in a contested discipline: challenges for student teachers and teacher educators. Oxford Rev. Educ. 33, 445–467. doi: 10.1080/03054980701450886

Cansoy, R., Polatcan, M., and Parlar, H. (2018). Research on teacher self-efficacy in Turkey: 2000-2017. World J. Educ. 8, 133–145. doi: 10.5430/wje.v8n4p133

Carver, C. L. (2016). Transforming identities: the transition from teacher to leader during teacher leader preparation. J. Res. Leadership Educ. 11, 158–180. doi: 10.1177/1942775116658635

Coughlan, M., Cronin, P., and Ryan, F. (2009). Survey research: process and limitations. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 16, 9–15. doi: 10.12968/ijtr.2009.16.1.37935

Crowther, F., Ferguson, M., and Hann, L. (2009). Developing Teacher Leaders: How Teacher Leadership Enhances School Success. Corwin Press.

Danielson, C. (2006). Teacher Leadership That Strengthens Professional Practice. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Davidson, B. (2014). Examining the relationship between non-cognitive skills and leadership: the influence of hope and grit on transformational leadership behavior (Doctoral dissertation), University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, United State

Day, D. V. (2000). Leadership development: a review in context. Leadersh. Q, 11, 581–613. doi: 10.1016/S1048-9843(00)00061-8

Day, D. V., Harrison, M. M. and Halpin, S. M. (2009). An Integrative Approach to Approach to Leader Development, Connecting Adult Development, Identity, and Expertise. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group.

Day, D. V., Harrison, M. M., and Halpin, S. M. (2012). An Integrative Approach to Leader Development: Connecting Adult Development, Identity, and Expertise. Routledge.

Duckworth, A., and Gross, J. J. (2014). Self-control and grit: related but separable determinants of success. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 23, 319–325. doi: 10.1177/0963721414541462

Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., and Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: perseverance and passion for long-term goals. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 92, 1087–1101. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087

Duckworth, A. L., Quinn, P. D., and Seligman, M. E. (2009). Positive predictors of teacher effectiveness. J. Posit. Psychol. 4, 540–547. doi: 10.1080/17439760903157232

Ent, M. R., Baumeister, R. F., and Vonasch, A. J. (2012). Power, leadership, and self-regulation. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 6, 619–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2012.00446.x

Eyal, O., and Roth, G. (2011). Principals' leadership and teachers' motivation: self-determination theory analysis. J. Educ. Admin. 49, 256–275. doi: 10.1108/09578231111129055

Gollwitzer, P. M., and Sheeran, P. (2006). Implementation intentions and goal achievement: a meta-analysis of effects and processes. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 38, 69–119. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38002-1

Hunzicker, J. (2017). From teacher to teacher leader: a conceptual model. Int. J. Teach. Leadership 8, 1–27.

Josselson, R., and Harway, M. (2012). Navigating Multiple Identities: Race, Gender, Culture, Nationality, and Roles. Oxford University Press.

Klenke, K. (2007). Authentic leadership: a self, leader, and spiritual identity perspective. Int. J. Leadership Stud. 3, 68–97.

Lumpkin, A. (2008). Teachers as role models teaching character and moral virtues. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 79, 45–50. doi: 10.1080/07303084.2008.10598134

Martin, N. K., Sass, D. A., and Schmitt, T. A. (2012). Teacher efficacy in student engagement, instructional management, student stressors, and burnout: a theoretical model using in-class variables to predict teachers' intent-to-leave. Teach. Teach. Educ. 28, 546–559. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2011.12.003

Miscenko, D., Guenter, H., and Day, D. V. (2017). Am I a leader? Examining leader identity development over time. Leadership Q 28, 605–620. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.01.004

Murphy, S. E., and Ensher, E. A. (1999). The effects of leader and subordinate characteristics in the development of leader–member exchange quality. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 29, 1371–1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb00144.x

Murphy, S. E., and Johnson, S. K. (2016). Leadership and leader developmental self-efficacy: their role in enhancing leader development efforts. N Direct. Student Leadership 2016, 73–84. doi: 10.1002/yd.20163

Nadelson, L. S., Callahan, J., Pyke, P., Hay, A., Dance, M., and Pfiester, J. (2013). Teacher STEM perception and preparation: inquiry-based STEM professional development for elementary teachers. J. Educ. Res. 106, 157–168. doi: 10.1080/00220671.2012.667014

Paglis, L. L., and Green, S. G. (2002). Leadership self-efficacy and managers' motivation for leading change. J. Organ. Behav. 23, 215–235. doi: 10.1002/job.137

Perlman, D. J., and Pearson, P. (2012). A comparative analysis between primary and secondary teachers: a self-determination perspective. Res. J. Phys. Educ. Sports Sci. 7, 8–17.

Purvanova, R. K., and Bono, J. E. (2009). Transformational leadership in context: face-to-face and virtual teams. Leadership Q 20, 343–357. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.03.004

Reeve, J. (2002). “Self-determination theory applied to educational settings,” in Handbook of Self-Determination Research, eds E. L. Deci and R. M. Ryan (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press), 183–203.

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. Guilford Press.

Schimschal, S. E., and Lomas, T. (2019). Gritty leaders: the impact of grit on positive leadership capacity. Psychol. Rep. 122, 1449–1470. doi: 10.1177/0033294118785547

Sims, R. R., and Brinkman, J. (2002). Leaders as moral role models: the case of John Gutfreund at Salomon brothers. J. Bus. Ethics 35, 327–339. doi: 10.1023/A:1013826126058

Smulyan, L. (2016). Stepping into their power: the development of a teacher leadership stance. Schools 13, 8–28. doi: 10.1086/685800

Sosik, J. J., Potosky, D., and Jung, D. I. (2002). Adaptive self-regulation: meeting others' expectations of leadership and performance. J. Soc. Psychol. 142, 211–232. doi: 10.1080/00224540209603896

Spears, L. C. (2010). Character and servant leadership: ten characteristics of effective, caring leaders. J. Virtues Leadership 1, 25–30.

Stets, J. E., and Burke, P. J. (2000). Identity theory and social identity theory. Soc. Psychol. Q 63, 224–237. doi: 10.2307/2695870

Stoltz, P. G. (2015). Leadership grit: what new research reveals. Leader Leader 2015, 49–55. doi: 10.1002/ltl.20205

Taylor, I. M., and Ntoumanis, N. (2007). Teacher motivational strategies and student self-determination in physical education. J. Educ. Psychol. 99, 747–760. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.4.747

Teacher Leadership Exploratory Consortium (2011). Teacher Leader Model Standards. Retrieved from: https://www.ets.org/s/education_topics/teaching_quality/pdf/teacher_leader_model_standards.pdf (accessed October 9, 2020).

Veldman, I., Admiraal, W., Mainhard, T., Wubbels, T., and Van Tartwijk, J. (2017). Measuring teachers' interpersonal self-efficacy: relationship with realized interpersonal aspirations, classroom management efficacy and age. Social Psychol. Educ. 20, 411–426. doi: 10.1007/s11218-017-9374-1

Wenner, J. A., and Campbell, T. (2017). The theoretical and empirical basis of teacher leadership: a review of the literature. Rev. Educ. Res. 87, 134–171. doi: 10.3102/0034654316653478

Keywords: teacher leader, leader identity, teacher identity, attribute of leader identity, teacher role

Citation: Nadelson LS, Booher L and Turley M (2020) Leaders in the Classroom: Using Teaching as a Context for Measuring Leader Identity. Front. Educ. 5:525630. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.525630

Received: 10 January 2020; Accepted: 29 September 2020;

Published: 26 October 2020.

Edited by:

Lauri Johnson, Boston College, United StatesReviewed by:

Jana Hunzicker, Bradley University, United StatesLauren P. Bailes, University of Delaware, United States

Copyright © 2020 Nadelson, Booher and Turley. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Louis S. Nadelson, bG5hZGVsc29uMUB1Y2EuZWR1

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Louis S. Nadelson

Louis S. Nadelson Loi Booher

Loi Booher Michael Turley†

Michael Turley†