- 1Institute of Education and Behavioural Sciences, Dilla University, Dilla, Ethiopia

- 2Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

- 3Department of Education, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

The purpose of this article is to explain the practice, challenges and future prospects of community-based rehabilitation (CBR) in Gedeo zone, a district of nearly one million inhabitants in the south of Ethiopia. The study used a mixed methods design. The quantitative part of the study involved 138 parents and care givers selected by convenient sampling technique. In addition, a total of 22 (seven female and 15 male) research participants were purposively selected from various categories: one head of zone labor and social affairs, three heads of district labor and social affairs, three representatives of associations of PWDs, 11 parents, two CBR heads, and two CBR social workers. Questionnaires and interviews were used as tools of data collection. The data were analyzed using both descriptive and thematic analysis. The finding indicated that there was no well-established CBR service provision for PWDs in Gedeo zone to ensure full participation and successful adjustment in the community. The article also revealed that a lack of trained manpower, following the charity model of CBR, and a failure to understand the modern essence of CBR were some of the major challenges that hindered the implementation of CBR service in Gedeo zone. Based on the findings, we recommend the establishment of rehabilitation centers in combination with community services in various districts of the zone. CBR requires centers with skilled staff, able to empower local people in the community to develop inclusive structures. Furthermore, we suggest that the practice of CBR in Gedeo zone should empower CBR workers in community-based inclusive development.

Introduction

United Nations [UN] (2008) in Jacob (2015) states that people with disabilities (PWD) comprises those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments resulting from any physical or mental health conditions, which in interaction with various barriers, may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others. World Health Organization [WHO] (2011) reported that PWDs are excluded from education, health, employment and other aspects of society and that this can potentially lead to or exacerbate poverty. Furthermore, they are not provided with appropriate rehabilitation services.

In tracing back to the historical development of CBR, WHO was the main actor initiating the launch of CBR in accordance with the Declaration of Alma-Ata in 1978 intended to improve the conditions of persons with disabilities (PWDs) as well as their families. It was also intended to address the needs of PWDs and enable them to achieve social participation. However, for a long time, rehabilitation services did not provide PWDs with the help of trained professionals. Therefore, for many PWDs, in some regions and/or communities or social groups, the only rehabilitation service was a traditional approach provided within their own communities.

In the 1994 position paper by ILO, UNESCO, and WHO, the concept of CBR is defined as follows: ‘CBR is a strategy within general community development for the rehabilitation, equalization of opportunities and social integration of all PWDs.’ It is a holistic approach to community development, mainstreaming disability and building an inclusive society for all. It is further stated that ‘CBR’ is implemented through the combined effort of [PWDs] themselves, their families and communities, and the appropriate health, education, vocational, and social services (ILO, UNESCO, and WHO, 2004, p. 7).

Eventually, as reported in the joint position paper (2004), some significant changes have been made to this concept. Initially defined as social integration (1994), in 2004 the concept of CBR was re-defined as moving further toward social inclusion with more emphasis on the role of organizations of persons with disabilities (DPOs) to demand governmental services (ILO, UNESCO, and WHO, 2004). These changes appear to reflect a paradigm shift from a rehabilitation program toward an empowering model. The ideal CBR approach, which adopts the social model of disability, has been defined by the aforementioned organizations as follows:

• CBR focuses on empowerment, rights, equal opportunities and social inclusion of all PWDs.

• CBR is about collectivism and inclusive communities where PWDs, their families and community members participate fully for resource mobilization and development of intervention plans and services for PWDs.

• CBR needs to be initiated and managed by insiders in the community, rather than outsiders, for its sustainability. (Cheausuwantavee, 2007)

However, in practice there are still a lot of challenges in the adoption and implementation of this ideal CBR approach. This is partly due to the fact that many of the concepts in CBR are still unclear.

As a consequence of three decades of experience with CBR, the World Health Organization has reformulated the principles and presented new CBR guidelines (WHO, 2010).

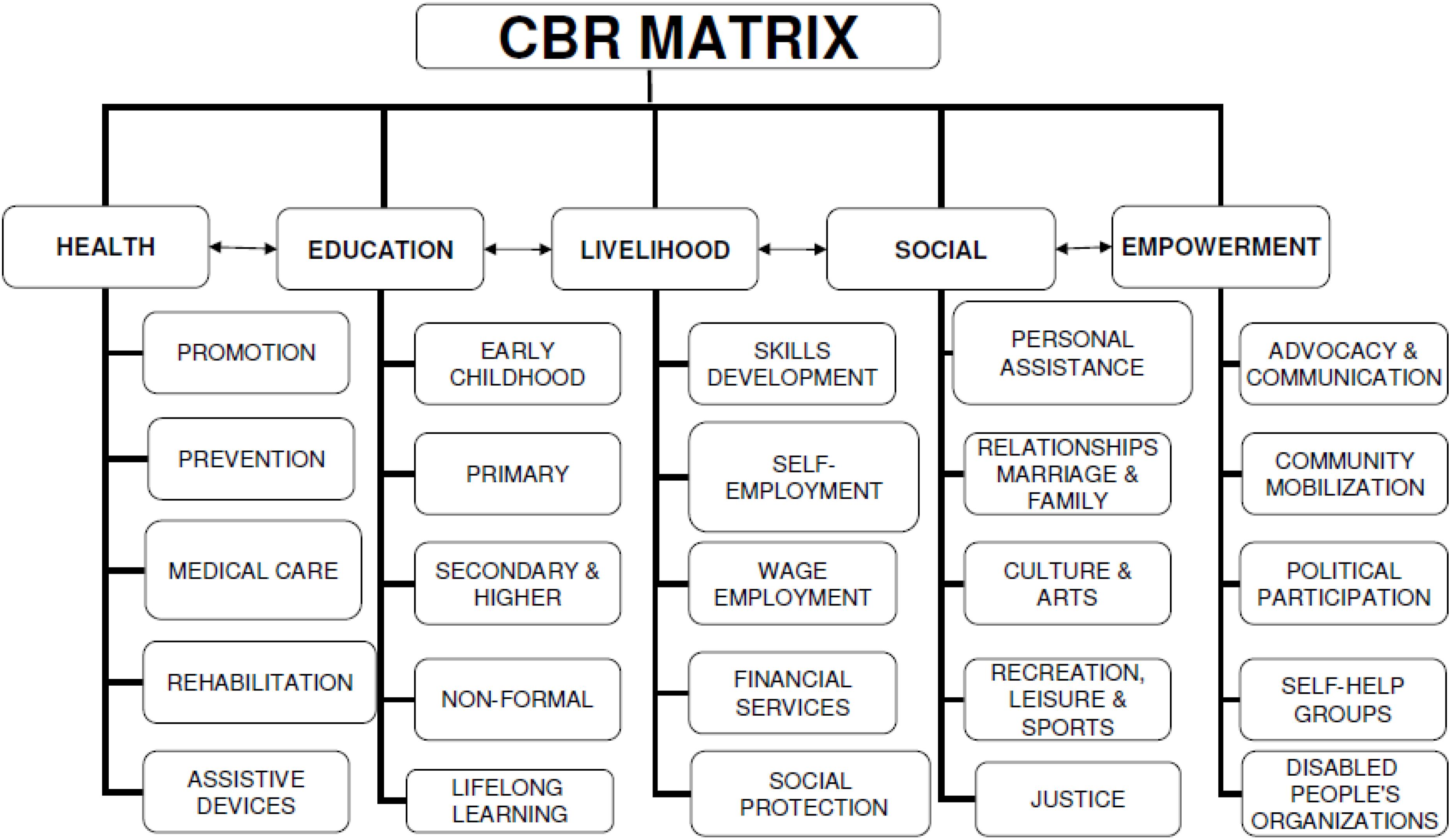

The CBR matrix provides a structured overview of thematic areas (health, education), life conditions (livelihood, social) and political strategies to improve the situation (empowerment). The CBR guidelines aim to connect the different areas and to show the direction toward inclusive development.

Likewise, in recent years, rehabilitation programs in developing countries like Ethiopia have mostly cases been adopted by either governmental or non-governmental organizations (FSCE, 2000). Moreover, different governmental and non-governmental organizations have been working to ameliorate the situation of PWDs. Most of the attempts made in developing countries like Ethiopia are uncoordinated and do not adequately involve the community in rehabilitation activities (FSCE).

Among millions of people with various degrees of disabilities in Ethiopia, only few are beneficiaries of rehabilitation services (Wegayehu, 2004). For instance, Save the Children UK supports few local NGOs involved in disability programs in collaboration with the communities to carry out CBR activities. CBR promoters work directly with PWDs in what is known as ‘cross-disability groups’ (CDGs). The functions of these groups are threefold: (1) working for the schooling of their children (parents are members), (2) promotion of income-generating activities and (3) working for skills training workshops in their vicinities (ACPF, 2011). Besides, Wegayehu (2004) states that many PWDs worldwide, particularly in developing countries, are living in poor health conditions and extreme poverty, not only because of their disability, but also due to their lack of a barrier-free environment.

Despite the current acceptance of CBR as an important strategy in improving the lives of PWDs, lack of comprehensive research-based data on the access, practice and challenges at both global and national level makes it impossible to understand to what extent CBR is an effective strategy. This in turn hinders the development and implementation of effective rehabilitation policies and programs (World Health Organization [WHO], 2011). Moreover, as indicated by Wegayehu (2004), the few rehabilitation services existing in Ethiopia are mostly located in the capital city, Addis Ababa, at Paulos Specialized Hospital, and in a number of major towns such as Mekele, Hawassa, Arbaminch, Dire-Dawa, and Jimma. Therefore, they cannot serve PWDs who live far away from the service deliverers. Tigabu (2008) and Yeshimebet (2014) also reported that these CBR services could only address less than 1% of the total rehabilitation needs of PWDs in the country.

The LIGHT FOR THE WORLD Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR) Framework brought together 14 CBR projects in Ethiopia, Burkina Faso and Mozambique between 2009 and 2011 to share experiences and learning. Between them, the projects reached 20,991 beneficiaries. Although the Framework has now ended, the individual projects continue to implement CBR activities with support from LIGHT OF THE WORLD.

Similarly, PWDs live in different districts of Gedeo zone did not get appropriate CBR services. These marginalized group of the society continued for long period of time facing challenging life without CCBR services. In responding to this gap, recently the Zone labor and social affairs took initiation to launch CBR project that was considered as part of a comprehensive multi-partner project for the inclusion of PWDs in the various districts off the zone. It was planned to include the municipality and the local office of the ministry of social affairs, CBR workers, NGOs and association of PWDs to provide CBR service to PWDs. Each stakeholders were expected to make contribution to the project with a sound basis of communication and information sharing. Therefore, the article explored the practice of CBR in the study area in collaboration with University of Vienna.

A collaborative project entitled ‘Inclusion in Education for Persons with Disabilities’ was implemented in collaboration between four universities (Vienna, Gondar, Addis Ababa and Dilla) in 2017. One of the focus areas in which the APPEAR project team members of Dilla University became highly engaged was the work on collaborative research development to explore the practice, challenges and future prospects of CBR services in Gedeo zone, southern Ethiopia.

The ultimate goals of undertaking this participatory community-based research were threefold: (1) to assess CBR workers’ knowledge, skills and attitude gaps, (2) to explore the real practice of CBR services and challenges and (3) to provide directions for stakeholders on how to improve integrated CBR service provisions for PWDs.

Specifically in Gedeo zone in southern Ethiopia, the situation of PWDs is challenging: they suffer from lack of appropriate access to education, healthcare service, employability and accessible environment. This article illustrates the general practice, challenges and prospects of CBR in Gedeo zone in southern Ethiopia in line with the following research objectives:

• to examine the practice of CBR service provision to PWDs in Gedeo zone in southern Ethiopia,

• to determine whether PWDs have access to CBR services in the study area,

• to identify the challenges of CBR implementation in the study area,

• to outline the future prospect of CBR services in the study area.

Methodology

The study was conducted during 8 months in 2017 in Gedeo zone in southern Ethiopia. According to the CSA (2007) census, the zone has a population of 847,434, of whom 424,742 are men and 422,692 are women; the area is 1,210.89 square kilometers. As the research team work at Dilla University (the capital city of the zone where the study was conducted), they had the advantage of familiarity with the local language, local culture, and establishing local networks with people. This paved the way for the researchers to understand what kind of community services are in fact implemented and what impression the local people and officials had of the implementation of CBR.

The article intended to explore the practice of CBR service provision to PWDs, determine whether PWDs have access to CBR services, and identify the challenges of CBR implementation in the study area from the point of view of parents, caregivers and service providers. The selection of respondents and research participants was determined by two major reasons. First, the article intended to determine the challenges and experience of the service providers and higher professionals in the study area. Second, preliminary data collected from the study area, prior to the main study, indicated that parents/caregivers have been shouldering severe challenges in caring PWDs in their family. Therefore, the article sought to find out the insight of parents, caregivers and service providers about the topic under study.

The article followed a mixed methods research design in which quantitative data were collected by administering Likert type questionnaires with open-ended and closed-ended questions to the respondents. For qualitative data interview was used to elicit the participants’ insights into the practices and the opportunities and challenges pertaining to CBR service in the study area. The article used quantitative and qualitative methods of data analysis. The quantitative data were analyzed in regard to frequencies, percentages, and mean differences. Thematic analysis was conducted for qualitative data and was supplemented by narrative description and verbatim.

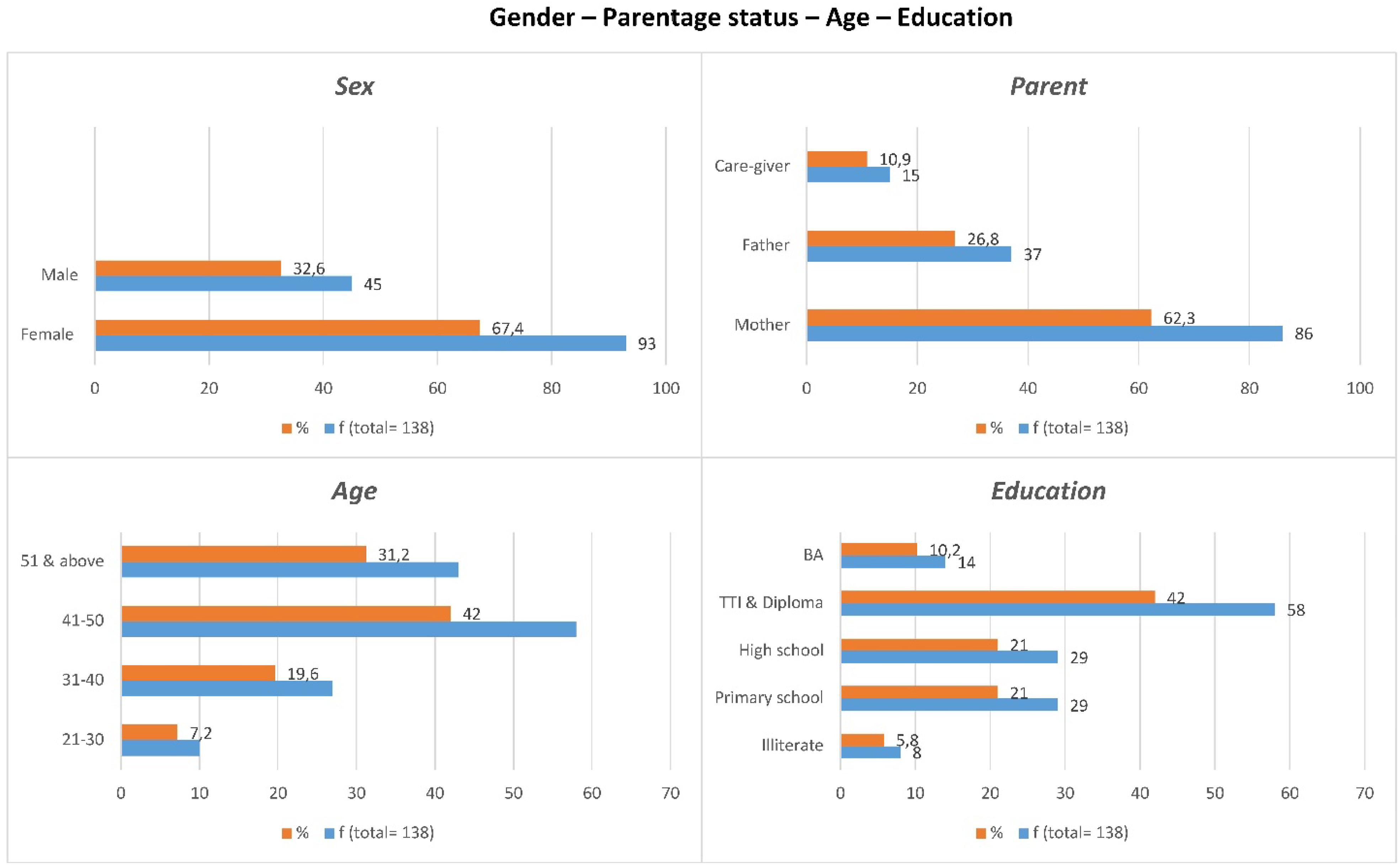

The article involved 138 parents and caregivers, selected by convenient sampling technique, for the quantitative data. More specifically, quantitative data were collected from 86(62.3%) mothers, 37(26.8%) fathers, and 15(10.5%) caregivers. Besides, 93(67.4%) are females and 45(32.6%) are males. Most of the respondents had good competence in reading, comprehending and responding to the questionnaire. However, there were some respondents assisted by the researchers to respond to the questionnaire because they were not able to read and write.

In addition, 22 research participants were selected from different categories: one head of zone labor and social affairs, three heads of district labor and social affairs, three representatives of associations of PWDs, 11 parents, two CBR heads and two CBR social workers. All research participants were from different sector offices and their ages ranged from 18 to 56. Seven research participants are females and 15 are males. They were selected purposively based on their experiences with PWDs and years of work experience related to CBR in the zone.

In regard to procedure, the researchers communicated with the participants to introduce the purpose of the study. This approach helped the researchers to secure the participants’ consent to respond and participate in the study. Based on the consent, a suitable time and place were arranged. In addition to the homes of the parents and caregivers of PWDs, offices of NGOs and offices of labor and social affairs in the zone and district were used to conduct the interviews.

The article used both quantitative and qualitative methods of data analysis. The quantitative data were analyzed with frequencies, percentages, and mean differences. Qualitative data were analyzed thematically. Therefore, the article adapted both inductive and deductive logical reasoning in addressing the research objectives. More specifically, in the quantitative part, deductive reasoning guided the researchers to reach a logically certain conclusion from one or more premises collected from respondents (Sternberg, 2009).

Whereas the article used thematic analysis to treat qualitative data. It was supplemented by narrative description and verbatim. To this part, the article employed inductive reasoning and moved from specific observations about individual occurrences to broader generalizations. In making use of the inductive approach, the article began with specific observations, and then moved to detecting themes and patterns in the data. This allowed forming an early tentative hypothesis that could be explored and triangulated with the findings of the quantitative part. Besides, the results of the exploration led to general conclusions (Creswell, 2013).

To ensure rigor in the process of qualitative data analysis, the article used A4 sheets of paper, pens, colored markers, sticky notes and large format display boards. This helped to bring the fractured data together into a coherent whole and supported understanding of the relationships between categories. During the analysis process, annotations and memos were created. This resulted in a number of interviews being coded more than once, encouraged reflection and comparison of emerging codes, particularly, codes which differed because of the coding approach adopted and ultimately increased the modes of interaction with the data.

The article addressed rigor in the quantitative and qualitative part. Rigor in the quantitative part dealt with ensuring reliability, replication, and validity by focusing mainly on the adequacy of the instruments.

The article also ensured rigor in the qualitative part by focusing on trustworthiness that involves credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability (Shenton, 2004; Rolfe, 2006). Credibility in the article focused on confidence in the ‘truth’ of the findings. It ensures that the article measures what is intended to measure and is a true reflection of the social reality of the participants. It was addressed by prolonged engagement through spending sufficient time in the field to learn to understand the culture, social setting, and phenomenon of the participants. Besides, the researchers conducted member checks to test the data, analytic categories, interpretations and conclusions with members of those groups from whom the data were originally obtained. In addition, persistent observation and triangulation were employed by using multiple data sources in an investigation to produce understanding (Vicent, 2014).

The article established transferability to ensure the ability of the findings to be transferred to other contexts or settings. Because qualitative research is specific to a particular context, it is important to provide the reader with a “thick description” of the research context to allow the reader to assess whether it is transferable to their situation or not. The researchers made explicit connections to the cultural and social contexts that surround data collection. The data were collected at offices of workers, home of parents and caregivers of PWDs during their free time based on their choice and consent (Irene and Albine, 2018).

Dependability of the article was addressed by a detailed audit trail of the researchers to verify that the findings are consistent with the raw data collected. Besides, they want to be sure that if some other researchers are to look over the data, they would arrive at similar findings, interpretations, and conclusions about the data (Creswell, 2013). Therefore, to establish dependability an outside researcher conduct an ‘inquiry audit’ on the study. This technique is also called an ‘external audit.’ It involves having a researcher outside of the data collection and data analysis examine the processes of data collection, data analysis, and the results of the article. This was done to confirm the accuracy of the findings and to ensure the findings are supported by the data collected. All interpretations and conclusions were examined to determine whether they are supported by the data itself (Irene and Albine, 2018). Finally, the study addressed confirmability by triangulation and reflexivity to minimize the researchers’ bias by acknowledging their predispositions (Korstjens and Moser, 2017).

Findings

Quantitative Findings

The following data emerged from a questionnaire which was developed by the research team of Dilla University. As no knowledge existed on the situation of CBR provision, the investigation should collect relevant data to describe the situation in the whole region. Some of the parents were illiterate or had low reading skills. Therefore, the data of some respondents and participants had to be collected face-to-face and it was not possible to give them anonymity However, much care has been done to keep confidentiality.

Demographic Data of the Respondents

As shown in Figure 1 below, 138 parents and caregivers (non-biological parents) are involved in the collection of quantitative data. Among these, 93(67.4%) are females and 45(32.6%) are males. Besides, 86(62.3%) respondents are mothers, 37(26.8%) are fathers and 15(10.9%) are caregivers. In terms of age, 10(7.2%) are aged 21–30, 27(19.6%) are aged 31–40, 58(42%) are aged 41–50 and 43(31.2%) are aged above 50. Furthermore, 58(42%) respondents are in possession of teacher training certificate and a diploma education level.

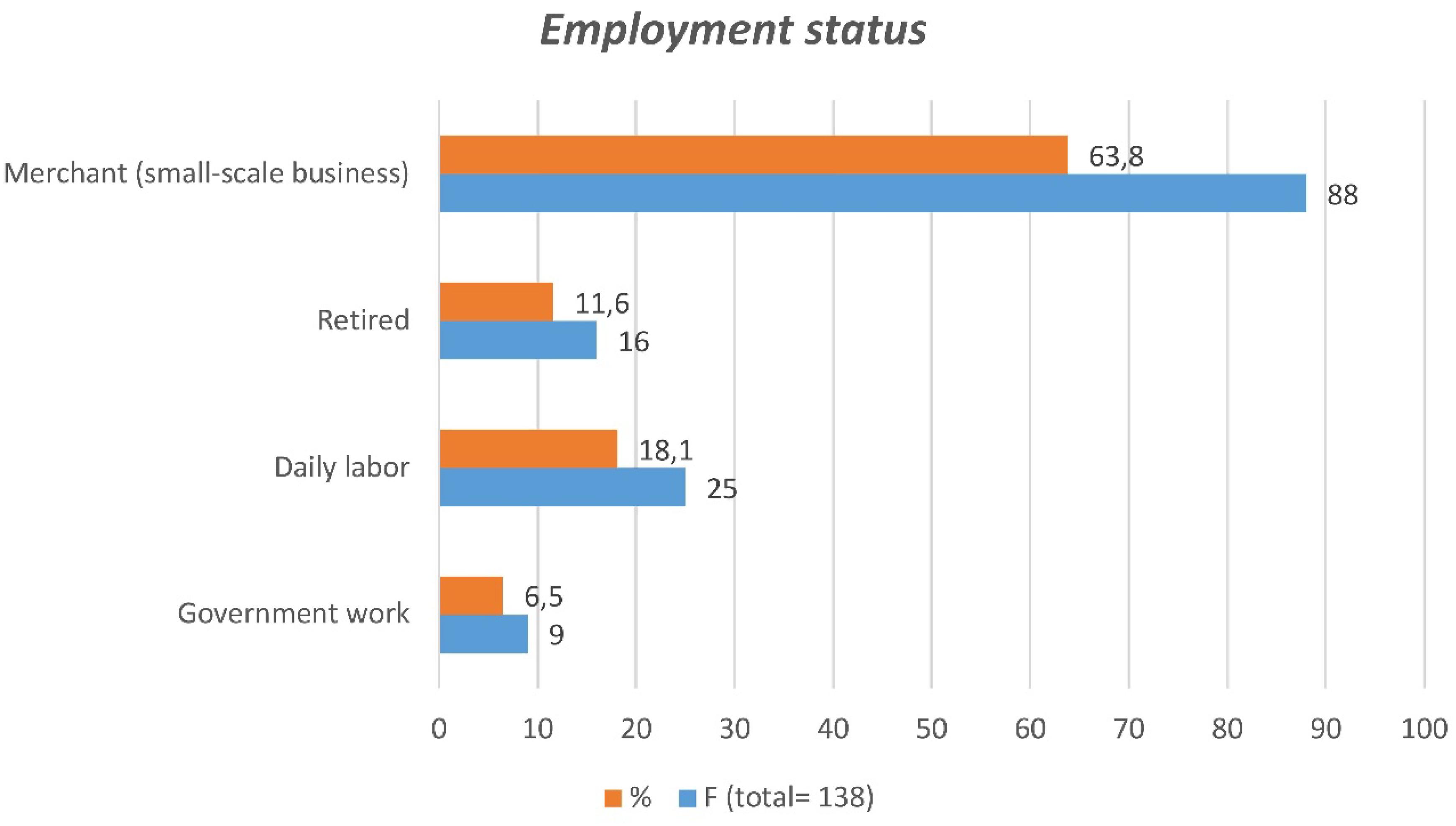

Figure 2 shows the employment status of parents. The majority of the parents and caregivers 88(63.8%) were in small-scale business. Furthermore, nine (6.5%) were employed by the government.

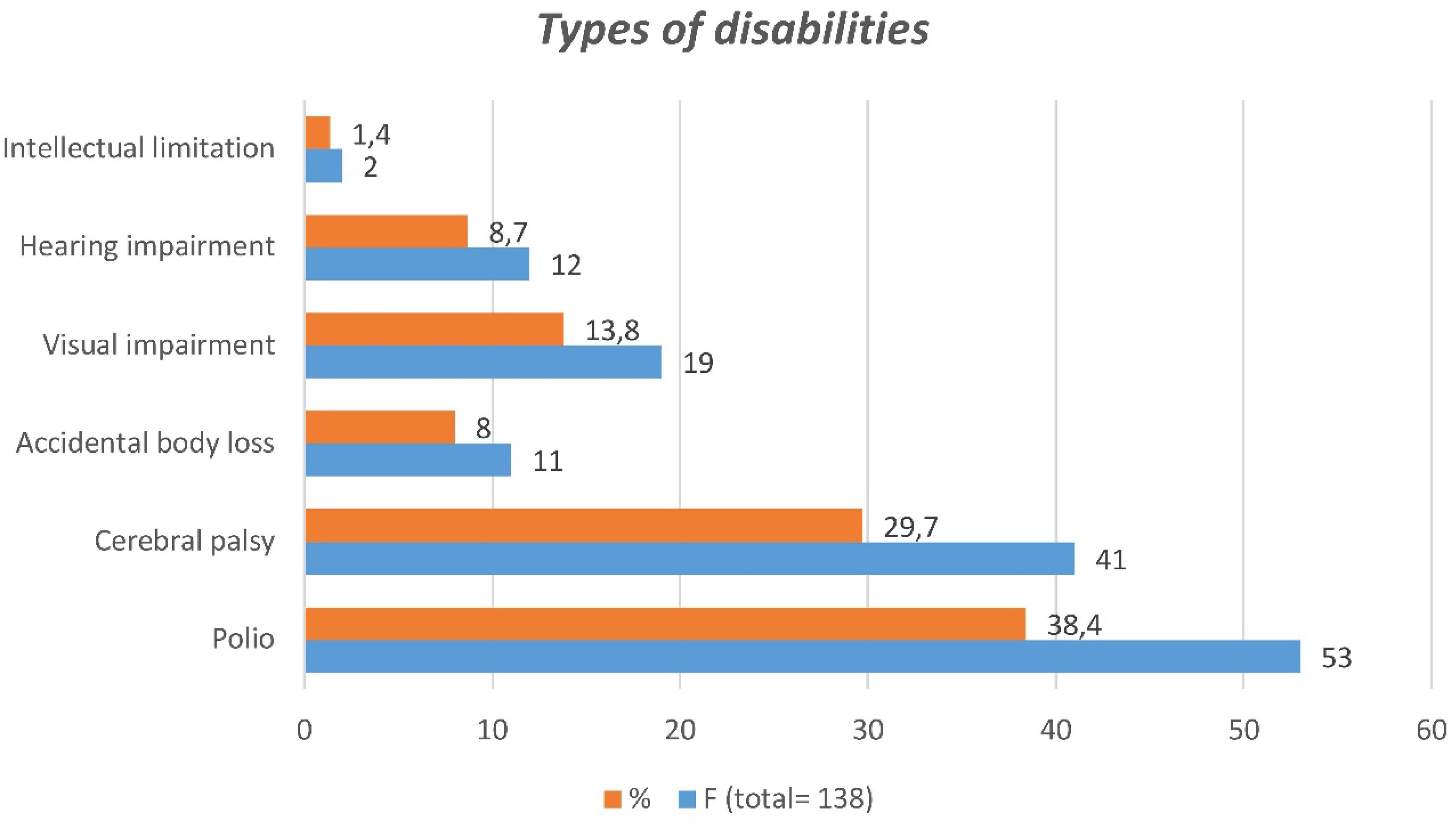

As shown in Figure 3, the majority of parents reported that their children had a physical impairment. The demographic data show that the majority of respondents indicated that their children are with polio 53(38.4%), followed by cerebral palsy 41(29.7%).

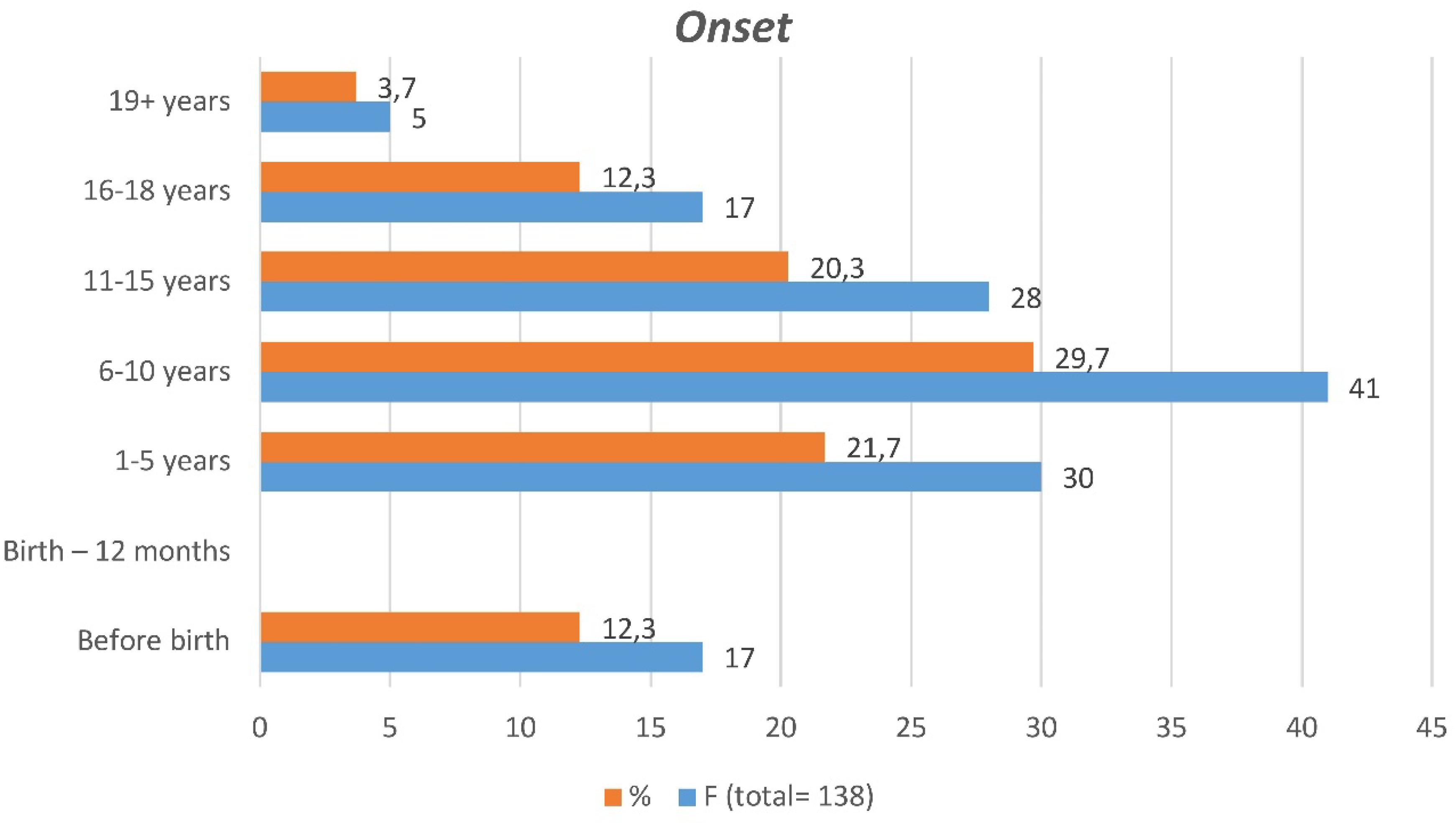

The article indicated the onset of the disabilities based on the data collected from parent and caregiver respondents. However, the disability might have been faced by the individuals much longer but might not yet have been identified early by their parents and caregivers or other professionals at the study area. Accordingly, as shown in Figure 3, 41(29.7%) respondents reported that the onset of their children’s disability was observed during childhood (ages 6–10) period. The period between ages 1 and 5 was reported by 30(21.7%) respondents as the onset of the disability. Ages 16–18 and age 19+ were reported as the onset of the disability by 17(12.3%) respondents and five (3.7%) respondents respectively.

Major Findings of the Quantitative Study

A five-point Likert scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree) was used to collect data. In the scale SA, strongly agree; A, agree; U, undecided; D, disagree; and SD, strongly disagree.

The practice of CBR in Gedeo zone

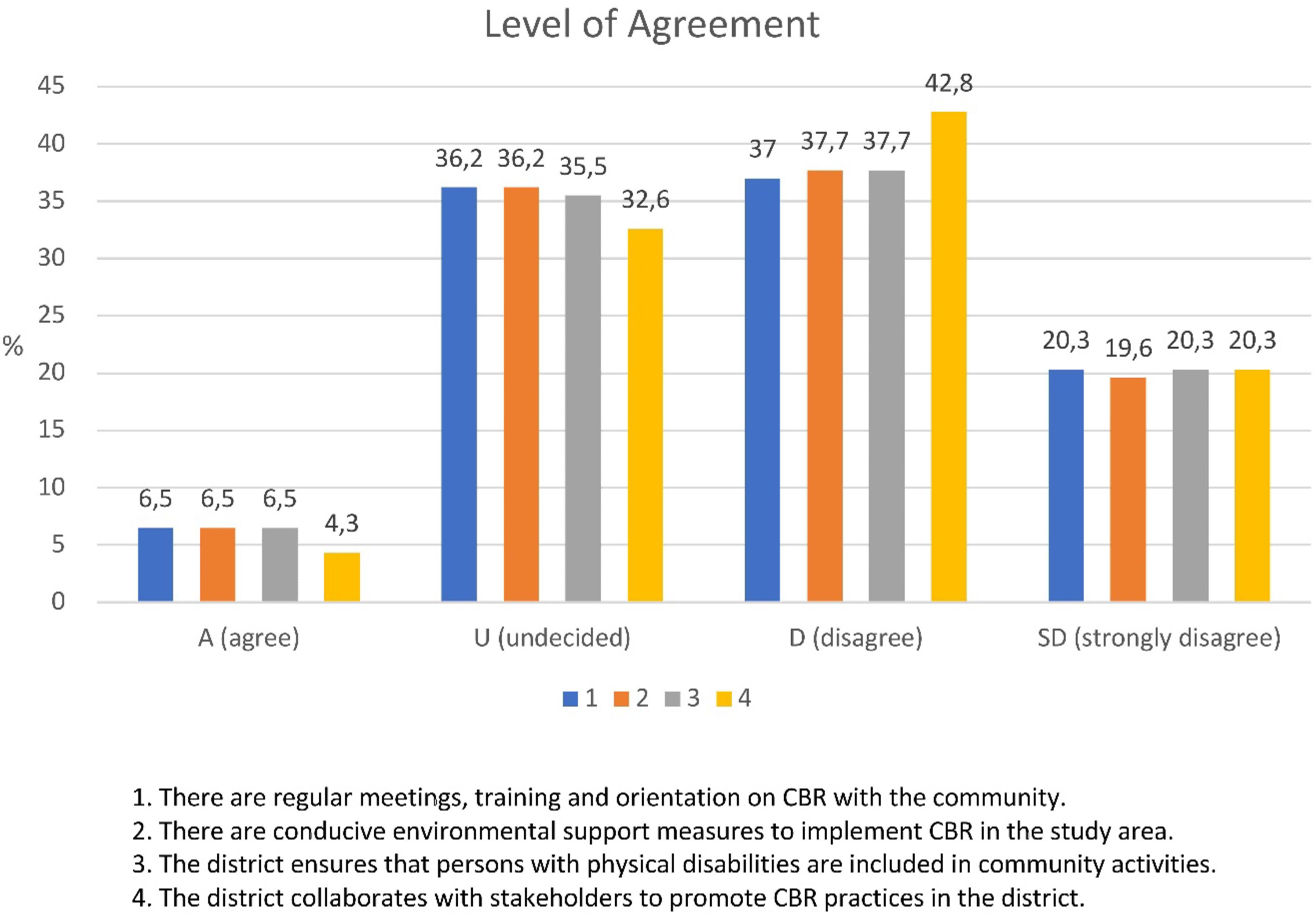

The data in Figure 4 clearly show that CBR service provision in the study area is weak. For instance, it was reported by a number of respondents that there are no community awareness practices related to CBR. Similarly, a significant number of respondents disagreed with the statement that conducive situations existed in support of CBR practices in the study area. Furthermore, efforts to collaborate with stakeholders in planning, implementing and evaluating CBR services are found to be insignificant.

Challenges in CBR implementation

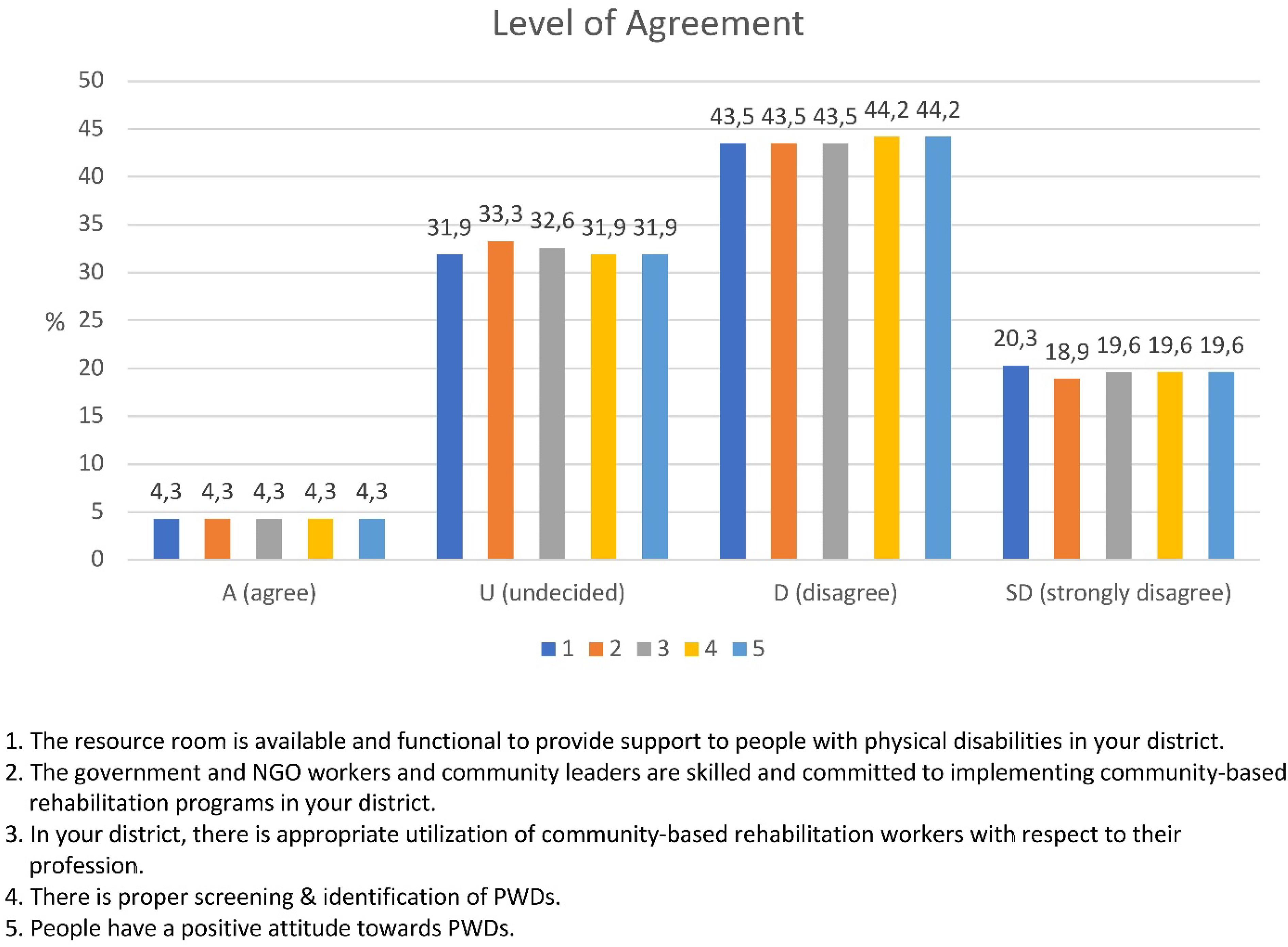

The respondents indicated the major challenges faced in the practice of CBR in the study area. The majority of the respondents reported that there are no functional resource rooms to provide support to people with physical disabilities; the majority also stated that government and NGO workers and community leaders are not skilled and committed to implementing CBR programs. Many said that there is a lack of screening and identification of PWDs. Besides, 44(31.9%) respondents are not able to decide.

The prospect of CBR services in the study area

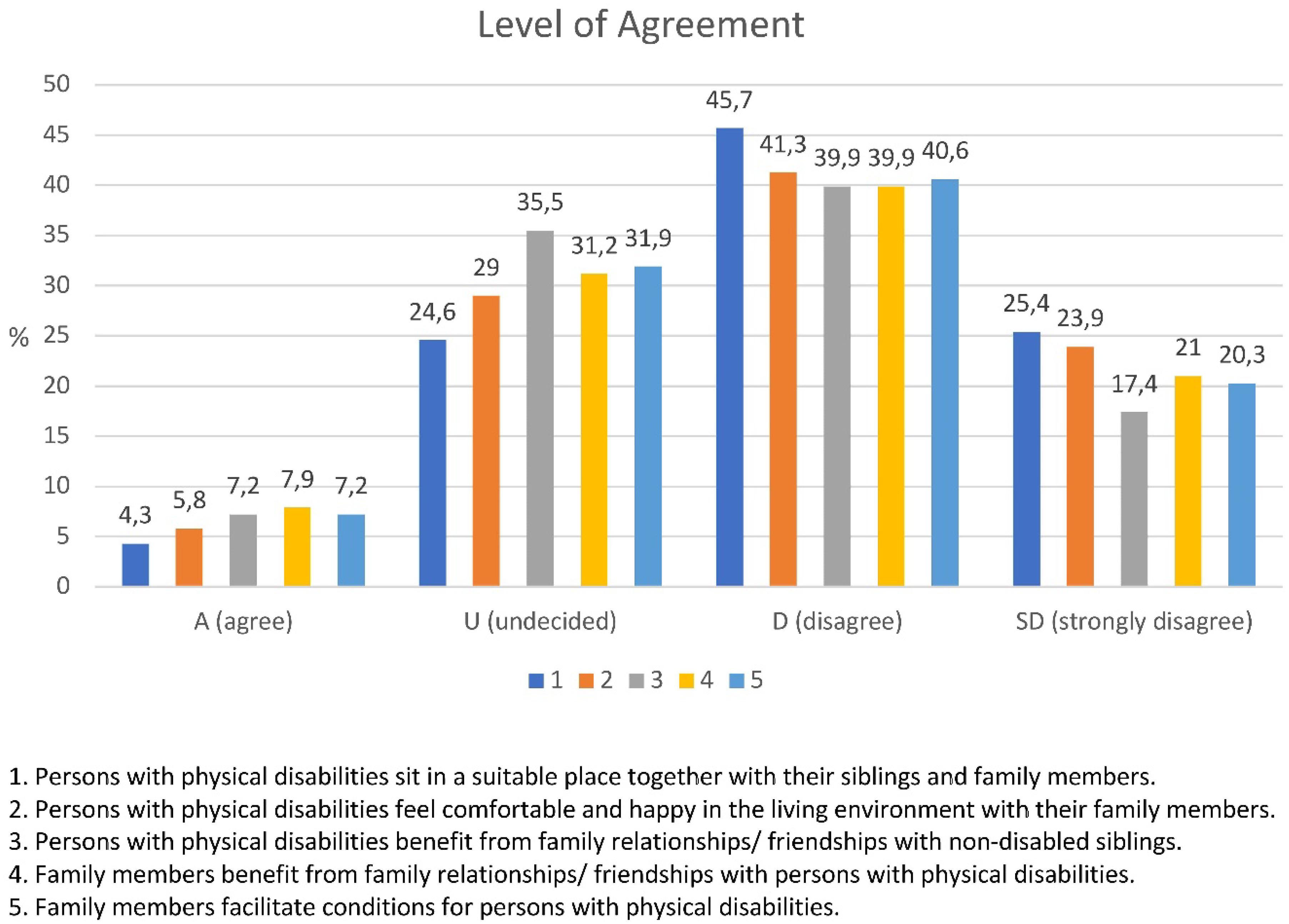

More than half of the respondents reported that persons with physical disabilities did not have convenient places to sit with their family members. Furthermore, the majority of respondents stated that family members did not facilitate conditions for persons with physical disabilities.

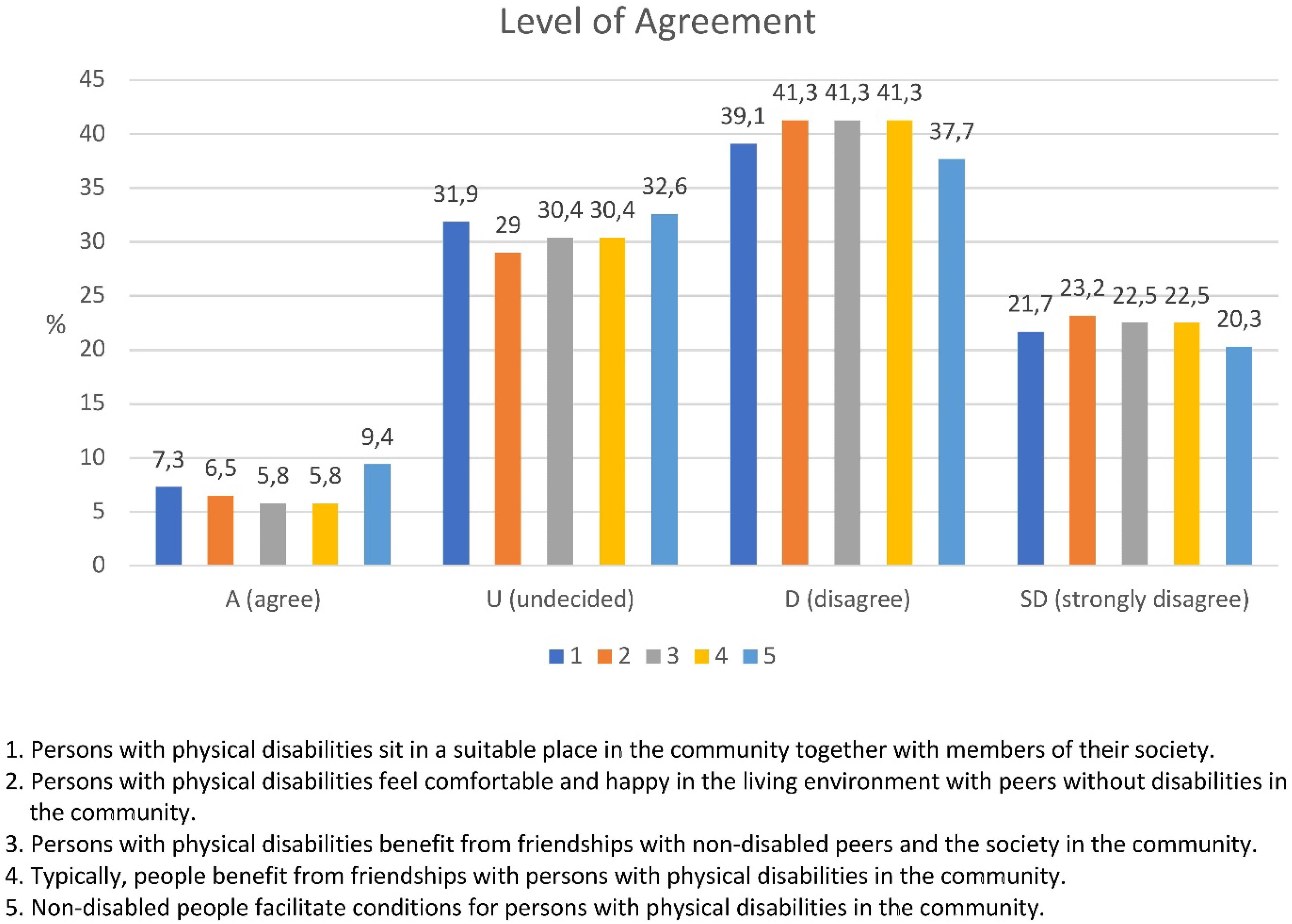

Interaction between persons with disabilities and the community

The majority of respondents reported that persons with physical disabilities did not feel comfortable in the living environment with peers without disabilities in the community. They stated that persons with physical disabilities did not benefit from friendships with their non-disabled peers in the community.

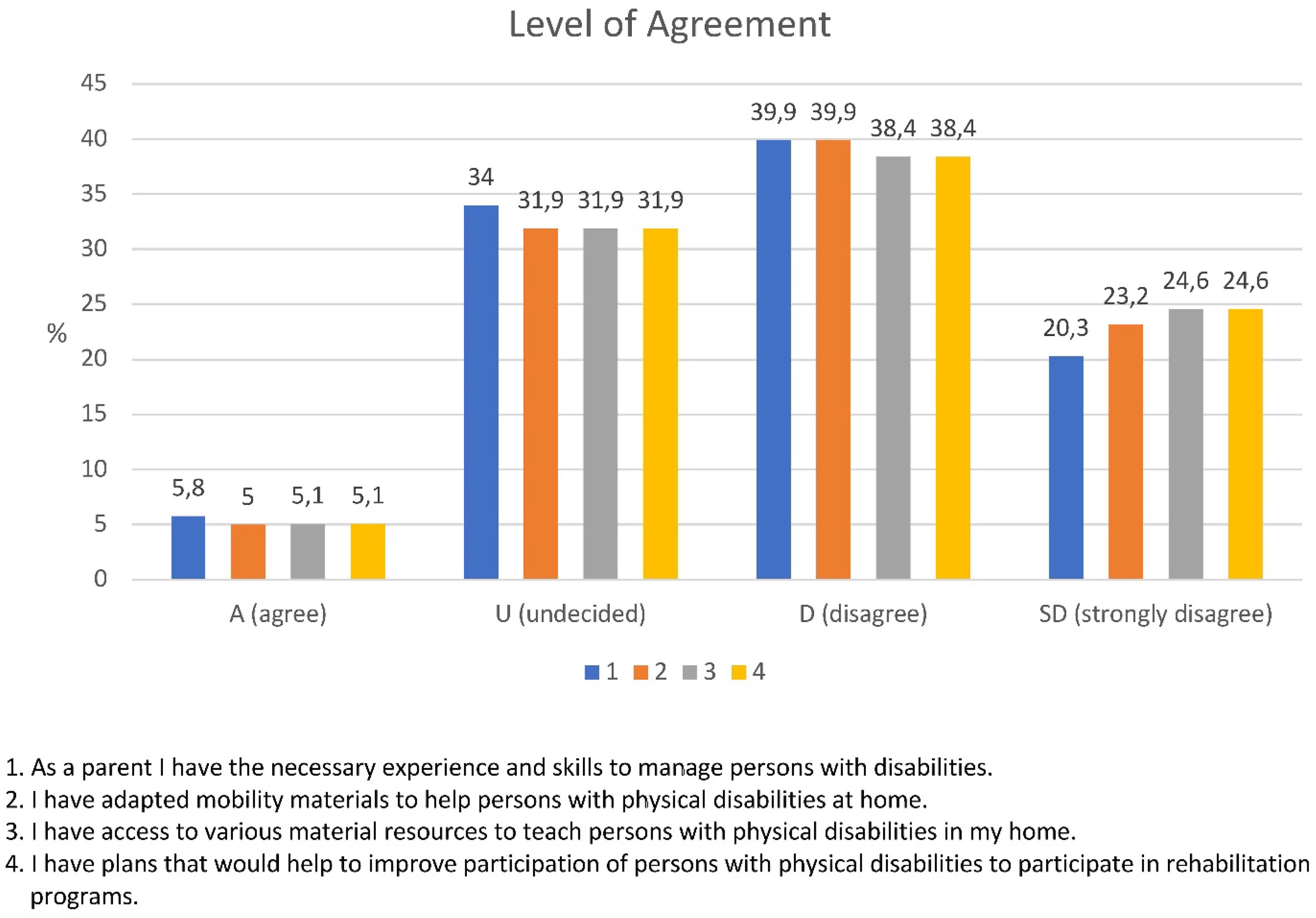

Experience and skills of the family in treating persons with disabilities at home

As depicted in Figure 5 below, the majority of respondents stated that they did not have experience in managing and teaching persons with physical disabilities and did not have adapted mobility materials and resources for persons with physical disabilities. Furthermore, the data reveal that the parents have no access to resources and are not involved in the process of planning and implementation of the CBR program.

Large numbers of respondents answered ‘undecided.’ This might have been due to the dilemma they face to say agree or “Disagree” on the issues raised. The dilemma also might be due to their poor understanding on disability and CBR. Therefore, the article probed the research participants for further deep investigation in the qualitative part to triangulate the quantitative finding with supplementary qualitative data. The article presents the finding in the preceding section.

Qualitative Data

Families of PWDs in countries of the Global South are a highly vulnerable group. Collecting qualitative data with this group and in their social environment provokes ethical questions. Institutions or boards for ethical approval in social research did not exist in Dilla University at the time of this investigation. Nevertheless, ethical considerations accompanied all stages of field research of the Dilla University team, which collected the data. The research team, which includes a blind person, is highly sensible not to violate any right of their parents or any other actor in the field. Informed consent to publish quotes in an anonymized way was taken from all interviewees.

Accessibility of CBR for Persons With Disabilities in Gedeo Zone

In the qualitative part of the study, the following questions were presented to interview participants; ‘Is there access to CBR for persons with disabilities in your locality? Do you have awareness of the CBR program of your locality? Is there an awareness creation program on CBR in your locality? What type of CBR program is available? How long do you travel to get CBR? Are there sufficient materials for the CBR program?” Based on the participants’ report to each item, key themes were identified to conduct thematic analysis.

The following themes were identified: accessibility of CBR program, client and family awareness of accessibility, means of awareness creation regarding the accessibility of CBR program, and general practice of CBR. These themes are reflected in the verbatim of the participants presented below. In order to ensure ethical standards and safeguard the confidentiality of the participants’ responses, the study used codes such as: Interview with Parents (IP), Interview with Zone Labor and Social Affairs Officers (IZO), Interview with District Labor and Social Affairs Officers (IWO), Interview with District NGO Workers (INW), and Interview with Association of Persons with Disabilities (IA).

All participants reported that there were very limited rehabilitation activities to provide financial and material support and that there was no rehabilitation center to satisfy the demands of PWDs. Only two rehabilitation centers, namely Hawassa and Arbaminch, provided wheelchairs and crutches. This material was scarce and mostly unable to meet the PWDs needs. Therefore, some supportive material was provided for a few PWDs by ‘Red Cross International.’ One mother of a child with a physical disability reported that she did not have access to CBR service in the zone.

I have a child with a physical disability aged 18. I have been challenged and have received no support. I have not been able to get any CBR service for the last 16 years. But recently, starting last year, the Gedeo zone labor and social affairs department offered some support. Mary Joy also gave me some monthly financial support.

Another parent also reported that there was no provision of CBR for PWDs in Gedeo zone.

My child is blind and learning at primary school. She is aged 13. It is really very challenging to care for a child with a disability in a situation in which no one is supporting you. My husband is a farmer farming on a rented piece of land. We have no sufficient income to support our six children including the one who has a visual impairment. Thank God, for the last 2 years my daughter has been getting monthly pocket money and support for educational equipment including a school uniform from the office of district social affairs Balaya welfare association.

As reflected in the above verbatim, the offices of social affairs of districts provided support consisting in financial and educational equipment. NGOs did not rehabilitate PWDs. Therefore, offices of district social affairs and NGOs could not fulfill the rehabilitation demands of PWDs since they did not have the capacity or special centers equipped with advanced rehabilitation materials. The wife of a person with a physical impairment stated:

As you can see, my husband has a physical impairment. His two legs have not functioned since his childhood. We have stayed in marriage for the last 12 years. We have three children. We have no means of income. I and my husband lived on begging at a road every day. We did not get any CBR program. But starting last year Mary Joy has given us a little support.

As reflected above, persons with disabilities live in harsh conditions. Their environment does not meet their interests and needs. The parent of a child with a disability said, “I have no information about the CBR program in my district, but the district officials sometimes call us for a meeting and tell us to bring our children and family members with disabilities for registration.”

Representatives of associations of PWDs stated, “There is no CBR program in the district and zonal levels, too. I am not sure if the people have awareness of the CBR program and its availability in our districts.” One Gedeo zone labor and social office coordinator reported:

In Dilla town there is one non-governmental organization (Belaya) working in six kebeles, which is an insignificant number compared to the total number of kebeles found in Gedeo zone. Balaya is not working directly with PWDs. When we asked Balaya to support these PWDs, we didn’t get responses.

Another parent gave testimony on the status of the support system for PWDs:

I am afraid to say that PWDs had little access to CBR in our district. However, there is recently launched support provision for PWDs and for their associations. It involves providing monthly pocket money to students with visual impairment, providing training on entrepreneurship and startup funding for job opportunities, providing a suitable manufacturing area and market opportunities. However, I strongly believe that there should be a community-based rehabilitation (CBR) program for people of our district who are living with various types of severe disabilities.

The interviews with district labor and social affairs officials also indicated that there was no CBR service in the zone. One officer stated:

I do not have any information on the availability of CBR programs in our zone. It is also the challenge of our office that we have not been able to send our clients to nearby centers. Therefore, we have been forced to send the clients to Hawassa Cheshire foundation and Arbaminch rehabilitation center for rehabilitation and the provision of orthoses and prostheses.

Similarly, the other district labor and social affairs officer reported:

CBR program in our zone?..eh… I do not think. But there are NGOs like us which are working on welfare activities. It would facilitate our activities if there were CBR centers in our zone. …eh…for instance, there are PWDs in our welfare package…they should get rehabilitation services…thus, we are sending them to Hawassa Cheshire foundation for physical rehabilitation and for the provision of other equipment.

As illustrated above, interviews both with PWDs and with zone and district social affair officers clearly revealed that PWDs in the study area (Gedeo zone) did not have access to rehabilitation services where the non-governmental organizations working in the area were implementing activities related to children development and anti-HIV/-AIDS programs.

The Practice of CBR Service in Gedeo Zone

Regarding the practice of CBR, the majority of participants did not have any information on its availability in Gedeo zone. The head of zone labor and social affairs revealed that it was challenging to their office to meet the rehabilitation and financial demands of families of PWDs. Therefore, a number of PWDs and their families were not able to access rehabilitation services since the zone labor and social affairs faced transportation and financial limitation, as reported by the head. Only two or three out of thousands of PWDs of the zone were as lucky as to receive orthotic and prosthetic devices from nearby towns (Hawassa Cheshire and Arbaminch rehabilitation centers), and approximately 24 students with visual impairment received pocket money from their zone administration office through the zone labor and social affairs (LSA) office. In this regard, the head of the zone LSA reported:

We have 24 students with visual impairment, we delivered 20 canes and 10 packets of Braille papers that we got from Arbaminch rehabilitation center; however, those who demanded to change their old canes did not get support. The students asked for additional Braille materials… we could not afford that…how can we get them?…. it is our big problem….

Similarly, the Chelelektu district disability association chairman reported:

I did not see any concerned body working on CBR in our district. For instance, there is an association of PWDs in the district that has a membership of around 250 persons with disabilities. They do not get any rehabilitation service and assistive devices, which they have frequently demanded.

One representative of an association of PWDs stated:

Our association has a number of PWDs. We contribute 20.00 Ethiopian birr (0.61 Euros/0.72 USD) monthly. But still we are not getting any support from any source. Thus, the members are leaving the association, since they are not getting any benefit.

One parent interview shows that there was some financial support from the district labor and social affairs. The parent said, “There is some monthly pocket money for my child with visual impairment from his school that is budgeted by the district labor and social affairs.” Another parent reported, “We are getting some financial aid from Mary Joy.”

Interviews with district officials and representatives of associations of PWDs indicated that recently the office had launched a support measure for PWDs in providing entrepreneurship training and creating a manufacturing place and market opportunity. For instance, the district labor and social affairs office representative said, “We currently began giving training on vocational and entrepreneurship skills to PWDs. We also provide some startup financial support, a manufacturing place and market linkage for their product.” Similarly, a representative of another district reported, “Vocational training and financial support will be given to youths of our district who are organized in various associations…and the zone labor and social affairs department provides financial support to students with visual impairment of our district.”

The responses of different participants of the study revealed that there was no practice of CBR service focusing on the physical therapy and on the provision of assistive devices to enable PWDs to achieve full participation in the community.

Challenges Regarding the Implementation of CBR in Gedeo Zone

Pertaining to the implementation of CBR service, the participants reported that there were pervasive challenges to carrying out the program. There was a limited number of NGOs working with disability in the zone. Administrative staff turnover is another challenge in implementing the CBR program. For instance, one of the district labor and social affairs office coordinators stated:

We gave training to different officials and state workers on the rights of the PWDs and national and international declarations; however, it was wastage of the resources because we could not get those individuals who participated in the training in their former position. Due to promotion or turnover some workers or officials would leave their position without formal clearance so that they do not leave important documents at their previous offices for new workers. This would be a challenge for new workers assigned in the CBR area of the zone.

Labor and social affairs office coordinators added:

Sometimes good and positive leaders come to the position; in contrast some careless leaders who also have a negative outlook on PWDs come to the position… they do not give due attention to the rehabilitation needs of PWDs.

To sum up, quantitative data were collected from parents and caregivers with the help of questionnaires, whereas qualitative data were gathered through interviews from parents, caregivers, zone and district focal persons who did not take part in the quantitative part. The finding revealed that there are many factors, which negatively influence the implementation of CBR services for PWDs in the study area. The major factors identified by the participants were negative societal attitudes, lack of commitment both by government and non-governmental organizations, absence of trained manpower, poor financial and material support and mobilization and absence of CBR centers.

Lessons Learned From the Practice of CBR Service in Gedeo Zone

The majority of respondents and research participants explained that CBR service is not the responsibility of a single institution; rather it requires a collaborative effort where all players have their responsibilities. For instance, the interview participants indicated that government would take a lion share; and NGOs, community and civic organizations could all play their own roles in sharing responsibility. Government policies and strategies are also suggested to be implemented down to the bottom level.

The finding also indicated that poverty is deeply rooted in PWDs in the community. Therefore, based on the finding it is possible to infer that empowering PWDs regarding financial resources, vocational skills, academic skills, micro and macro enterprises, as well as providing material resources is fundamental to improve their lives. These conditions call for the collaborative effort of various sectors working hand in hand in the implementation of CBR.

Future Prospects of CBR Service in Gedeo Zone

In the survey questionnaire, participants reported that there were no conducive environmental conditions for CBR programs. However, in in-depth interviews with district and zone social affairs officers, the majority of respondents explained that there were potential resources in the areas of economic empowerment like small-scale enterprises such as animal herding, woodwork and market opportunities.

If there is a need to achieve full community integration and inclusion, there is a need for all PWDs to have equal access in all economic, health and educational services. However, data from interviews suggest that factors such as a negative societal attitude, problems of accessibility in the home, school and work areas have had a severe impact.

PWDs must have equal access to rehabilitation services and healthcare, employment and education to grant full community integration. However, physical and attitudinal barriers are major challenges to integration. Lack of appropriate infrastructure, poor housing, inadequate school conditions and inaccessible buildings where services and daily-living activities take place complicate the inclusion of PWDs. Each kind of barrier influences the provision of CBR to empower an individual to lead an independent life. According to WHO (2004):

CBR is implemented through the combined efforts of PWDs themselves, their families, organizations and communities, and the relevant governmental and non-governmental health, education, vocational, social and other services (ILO, UNESCO, and WHO, 2004, p. 2).

Discussion

Accessibility of CBR Service for Persons With Disabilities (PWDs)

PWDs in Gedeo zone have very limited educational access. Very few attend secondary school (grade 9 and 10). Only eight of the respondents were attending high school. Others had dropped out due to various challenges including lack of appropriate instructional approach at school, inaccessible school conditions, financial limitation, lack of health facilities, lack of support at home, environmental barriers and negative societal attitude. Some of the PWDs in the study were not undergoing formal education; few of them had very low literacy developed at home.

The article revealed that school enrolment and progress of PWDs in the study area is very limited. As indicated by the article, the prevailing barriers require intervention strategies.

Similarly, international context indicates that there is low literacy rate among PWDs (Mprah, 2013; UPHLS, 2015). For instance, persons with visual impairments cannot access printed sources; lack of awareness is also a barrier to attending healthcare services as families may not know that PWDs can be taken to general health care centers (Jolley et al., 2014). Besides, PWDs are often not able to access information to themselves so they are reliant on friends and family for health information, rather than on messages and information from health professionals.

Pertaining the importance of medical and rehabilitative interventions for PWDs, United Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific [ESCAP]/World Health Organisation [WHO] (2008) state that:

Medical and rehabilitative interventions are important in addressing body- level aspects of disability, i.e., impairments and limitations in a person’s capacity to perform actions; while at the same time environmental and social interventions are essential to deal with restrictions in a person’s participation in educational, economic, social, cultural and political activities.

However, the study reveals that PWDs have no access to CBR services. Parents also reported that they had no awareness of how they could support and manage the members of their family who had a disability. For instance, the study investigated home experiences of parents in managing and teaching persons with physical disabilities, adapting mobility materials and resources for PWDs, developing and implementing plans with CBR workers to facilitate participation, and obtaining access to resources in order to teach PWDs.

Parents had serious limitations in performing these activities. They had no experiences in managing and teaching people with physical disabilities at home. They were not able to adapt mobility materials and resources for persons with physical disabilities in the home. Furthermore, they had no access to resources in order to support persons with physical disabilities and provide them with life skill training.

Supporting the finding, Zuurmond et al. (2018) indicated that in low and middle-income nations where access to support and rehabilitation services for PWDs are often lacking, the evidence base for community initiatives is limited.

Furthermore, parents also has no knowhow in supporting PWDs in their family due to lack of training. These conditions reveal the importance of CBR service for PWDs and their parents. If parents and family members were trained and supported in managing disability issues, they would easily manage cases at home. They would also be able to create accessible and adequate conditions at home to address the special needs of the member of their family with a disability (Zuurmond et al., 2018).

To the contrary, the article revealed that the home conditions and the surrounding environment are very challenging and restricting the full participation of PWDs.

Similarly, evidence from other studies show that caregivers of PWDs in low resource settings are more likely to experience stress, social isolation, emotional and physical impacts (Gona et al., 2011; Donald et al., 2015). The scarcity or complete absence of rehabilitation services in low and middle-income countries can result in families in providing uncoordinated service and care for their children, often with little or no access to training and support (Mobarak et al., 2000).

CBR Practice in Gedeo Zone

WHO and World Bank (World Health Organization [WHO], 2011) indicate that the practice of CBR service has a holistic nature which ensures access to healthcare, education, social welfare, empowerment, livelihood and enabling poverty reduction capacity. WHO (2010) also indicates that the far-reaching goal of CBR should be to achieve community-based inclusive development and to ensure the implementation of the Convention on the Rights of PWDs. Besides, ILO, UNESCO, and WHO (2004) state that effective practice of CBR service necessitates collective efforts of PWDs, families, communities, and governmental and non-governmental organizations working in the area of health, education, vocational and social services.

The article shows that the majority of PWDs do not receive appropriate CBR services which would address the restoration of a PWDs to the maximum possible physical, vocational and economic independence and social inclusion. The majority of respondents (see in Figure 4) reported that the selected districts found in Gedeo zone do not conduct regular meeting, training and orientation on the issue of CBR with the community; the environmental settings of the districts do not support the implementation of CBR; the districts do not ensure the inclusion of PWDs in community social activities. Besides, the districts do not collaborate with stakeholders to promote CBR practices in the zone.

The article also reveals that there is a strong demand for assistive devices such as shoe raises, braces, crutches, orthopedic shoes, corrective shoes and wheelchairs for PWDs. However, as indicated by the participants, it is very difficult to obtain access to these devices since there are no centers providing this type of CBR service in Gedeo zone.

Participants reported further that there was a need for social rehabilitation of PWDs. According to Kahsay (2010), social rehabilitation enables PWDs to achieve a sense of wellbeing in the community similar to non-disabled members of the community. However, as indicated in Figure 6, the article indicates that persons with a physical disability are not provided with suitable places in their home as well as in the community. They feel uncomfortable and unhappy in the living environment and do not benefit from friendships with non-disabled peers and the society.

It was also found that there were some activities implemented by the Gedeo zone labor and social affairs department from 2009 to 2017. Among the main activities implemented by this department were the provision of monthly pocket money to students with visual impairment, providing entrepreneurship training and startup funding for job opportunities for youths of some districts, and providing a manufacturing area and market opportunity. Furthermore, the department sent some individuals with disabilities to Hawassa Cheshire and Arbaminch rehabilitation centers to provide them with orthoses and prostheses.

Moreover, a representative of Balaya which is a non-governmental organization, reported that their organization has been engaged in humanitarian activities in Gedeo zone by launching a charity support system to PWDs. According to Lang (2000), NGOs play a significant role in providing rehabilitation services to PWDs. The institution follows a charity-based approach where there is no sufficient collaboration with the local government entities. Hence, the head officer of Balaya reported that they had recently begun sending individuals with physical disabilities to the Hawassa Cheshire and Arbaminch rehabilitation centers for physiotherapy and device assistance. Furthermore, they provided educational materials like exercise books, pens, pencils and uniforms to students with disabilities at some schools.

However, they could not reach all students with disabilities due to a lack of baseline data. The comprehensive and multi-sectoral nature of CBR includes health (promotion, prevention, medical care, rehabilitation and assistive device), education (early childhood, primary, secondary and higher, non-formal and lifelong learning), livelihood (skills development, self-employment, wage employment, financial service and social protection), personal assistance, relationships, marriage and family, culture and arts, recreation (leisure, sports and justice) and empowerment (advocacy and communication, community mobilization, political participation, self-help groups and organizations of PWDs).

The existing practice of supporting PWDs in Gedeo zone shows that it is not in line with the basic concept of CBR. Roles and responsibilities are not shared among all concerned bodies. PWDs, their parents/families, the community, government, non-profit organizations and various associations are not coordinated to collaborate in the area of preventing disability, empowering PWDs to achieve quality of life and independence.

Challenges Regarding Implementation of CBR

Implementing the concept of CBR is an essential approach to meeting the prevailing challenges of PWDs in Gedeo zone. However, the study identified a number of barriers. The following sub-sections present the challenges identified.

Failure to Understand the Basic Concept of CBR

The article indicates that the practice of CBR in Gedeo Zone does not follow the basic concept of CBR. There is no firm association between all concerned bodies at different administrative levels. Roles and responsibilities are not shared among the concerned bodies. PWDs, parents/families, the community, government, not-for-profit organizations, voluntary associations, or public-private partnerships are not coordinated. Activities and strategies are not designed to be implemented at the various administrative levels to intervene on disability, empower PWDs, and develop the community’s economic, political, social and physical environment.

The article further indicates that the CBR practice in Gedeo zone does not consider the involvement of the community in the intervention, focusing only on PWDs. Furthermore, the majority of the respondents (see Figure 7), revealed that there is no functional resource room to give support for PWDs; the local governmental, NGOs workers and community leaders are not skilled and committed to implement CBR in its scientific sense; there is no appropriate utilization of CBR worker with respect to their profession; and there is no proper screening and identification of PWDs in the selected districts.

Caughy et al. (1999) explain that rehabilitation services intended to ameliorate individual problems should focus on the community, since individual problems including social, economic, environmental and political crises are deeply rooted in the community.

In supporting the article, other studies indicated that lack of clarity on the concept of CBR has impact on implementation of CBR. For instance, Morita et al. (2013) depicted poor skill, knowledge of CBR and lack of commitment as a factor hampering its implementation in Japan. Similarly, findings from South Africa (Lorenzo and Motau, 2014), Mongolia (Como and Batdulam, 2012), Asia and the Pacific (Cayetano and Elkins, 2016) revealed that the lack of skill and understanding on CBR affected the implementation of CBR in various contexts of respective areas.

Therefore, unless stakeholders have clear understanding on CBR, the changes expected from CBR in the lives of PWDs do not help to solve community problems. Besides, the CBR concept necessitates the implementers, community and all stakeholders to clearly recognize and firmly establish the link between individual challenges and the community’s role. Hence, similar to other parts of the world, the prevailing challenges identified in Gedeo zone induces making an effort to examine the existing situation of the zone at each level of the community.

Following the Charity Model

The other failure of the CBR implementation in Gedeo zone is the intention to follow the charity model by the governmental and non-governmental organizations. The charity model of disability follows a traditional perception, sees PWDs either as objects of sympathy and charity or as sick people in need for compassion, as victims of circumstance (UNICEF, 2007). This model considers PWDs as long-term recipients of support and welfare (Duyan, 2007).

However, if the implementation of CBR is accompanied by modern model of disability, it would expand disability service provision through establishing working partnerships between local communities, PWDs and their families, governments and rehabilitation professionals (Theeraphong and Mokbul, 2009; Pradeep et al., 2018). Such partnerships would use local resources to provide basic rehabilitation to a larger number of clients.

Conversely, due to the charity model followed in Gedeo zone, PWDs in various districts of the zone are perceived as unfortunate, tragic and helpless, deserving pity and charity. Therefore, the district labor and social affairs offices and some NGOs (Balaya and Mary Joy) show a tendency to provide support such as some monthly financial support for PWDs. However, this model of service provision does not lead to a holistic improvement for PWDs and their families. Instead, it perpetuates a sense of dependency of PWDs in the community.

Similarly, research findings from Nigeria indicates that regardless of high number of PWDs in Nigeria, empirical evidence depicted that social services including CBR is limited to PWDs and they are often excluded from social, economic and political matters. The common perception of disability intervention is often in terms of charity and consequently it became a significant factor that inhibits the social inclusion of PWDs in the country (Ahon Adaka et al., 2014).

WHO (2010) describes a modern understanding of CBR (see Figure 8) which focuses on promoting independence and a sense of satisfaction through participation of PWDs in the rehabilitation program in which they have their role and responsibilities. Therefore, the far-reaching goal of the rehabilitation must also consist in enabling the PWDs to become independent and productive and to be able to contribute to the development of activities of the general community. Entities operating in the various sectors and at the various administrative levels are advised to collaborate closely.

Figure 8. Areas of CBR activities (WHO, 2010: https://www.who.int/disabilities/cbr/matrix/en/).

Lack of Trained Manpower

The article indicates that there are no trained workers who can deliver CBR to PWDs in the community. As discussed above, the zone labor and social affairs department began registering PWDs living in the zone and launched providing monthly pocket money, few weeks vocational training with startup financial support. However, there are no trained workers assigned to serve PWDs in the community to address the rehabilitation demand of PWDs.

In line with this article, experience from Nigeria shows that there are challenges with regard to human resources in CBR that need to be solved. One has to do with the need for personnel who have the understanding and skills in various aspects of CBR, while the other is the lack of adequate numbers of trained personnel in this field (Ahon Adaka et al., 2014). Similar findings from Uganda depict that CBR programs are not intended or able to provide specialized medical care or advanced rehabilitative services through interdisciplinary clinics found in high-income countries; besides, it also uncovered that specialized rehabilitative medicine care remains inaccessible to PWDs due to human resource and health systems limitations in the local setting of Uganda (Lukia et al., 2017). Due to this, PWDs cannot enjoy their independent life. They would be deprived and marginalized from social interaction. For instance, as indicated on Figure 9, the majority of the respondents reported that PWDs from all age category (see Figure 10) did not feel comfortable in their environment.

Absence of Rehabilitation Centers

The article revealed that in Gedeo zone there are no rehabilitation centers, which can provide rehabilitation services to PWDs. The article revealed that GOs and NGOs working on disability issues are sending PWDs to Hawassa and Arbaminch rehabilitation centers for further assistance. Hawassa Cheshire is found to the north of Gedeo zone at a distance of 90 km and Arbaminch rehabilitation center is found to the east of Gedeo zone at 350 km. As the finding indicated sometimes it is difficult to send all PWDs to these rehabilitation centers for further assistance. As a result, it became challenging to address the special needs of all PWDs in their locality.

However, Seijas et al. (2018) indicate that CBR is an accepted model to improve the delivery of rehabilitation in the community. It includes the access to health care, education, labor and accessible environments. In addition to this, rehabilitation centers have paramount value in providing various kinds of rehabilitation services to PWDs to address physical, medical, education, social, vocational and counseling aspects of rehabilitation. The centers work on the provision of furnishing devices like shoe raises, braces, crutches, orthopedic shoes, corrective shoes and wheelchairs to support missing or damaged organs.

Moreover, Mauro et al. (2014) state that PWDs are to receive physiotherapy in addition to physical rehabilitation from the rehabilitation centers. Furthermore, rehabilitation centers provide appropriate active and passive exercises such as balance and coordination exercises, electric stimulation and pop correction (JICA, 2002).

Lessons Learned

The findings of the study at hand provide a valuable lesson concerning the existing CBR service in Gedeo zone.

• As indicated in the preceding section, persons with disabilities do not have access to modern CBR service. This raises the need to re-assess the existing conditions of PWDs and the real situation of the zone to provide effective CBR service to the community.

• There is a tendency to see PWDs as objects of sympathy and charity in Gedeo zone. This hinders the holistic change intended for PWDs and for the community. A modern CBR service is required in the zone for the rehabilitation, equalization of opportunities and social inclusion of PWDs.

• PWDs become dependent on the support provided by GOs and NGOs in Gedeo zone. This sense of dependency may have negative consequence for their functioning at present as well as for the future productivity of PWDs.

• The CBR activity of the zone does not involve the community. The support system only emphasizes the provision of charity to PWDs. As a result of this approach, it is very difficult to achieve holistic change in the lives of PWDs. Attitudinal barriers prevailing in the society hamper the full participation of PWDs.

• The authors did not involve the community in asking them what they think is the best way forward since the main focus of the article is investigate about challenges, not their views on how to tackle these challenges. Therefore, it would be advisable to conduct further study on how to involve the community in the rehabilitation service.

The zone has no rehabilitation centers to provide appropriate medical care, physiotherapy and adapted physical exercise. Few lucky individuals get the opportunity to attend rehabilitation centers nearby. However, many PWDs remain at home without any rehabilitation service. PWDs in various districts of Gedeo zone do not have access to social rehabilitation, and as a result they face social challenges posed by their disability. There is no trained manpower to deliver CBR service to PWDs in Gedeo zone. It was thus very difficult to reach all PWDs in the various districts.

Future Prospects of CBR in Gedeo Zone

Based on the findings of the study, it is possible to state that unless the zone administrative bodies take corrective measures to adopt, adapt or develop a modern CBR program, it will be very challenging to effectively address the developmental need of PWDs in the zone. Moreover, if the charity model of CBR is perpetuated, the level of dependency of PWDs might be aggravated.

Conclusion

PWDs in Gedeo zone have no access to effective CBR service. They do not attain full participation since the zone’s CBR approach does not consider the rehabilitation of the social environment. The absence of rehabilitation centers in the zone exacerbates the challenges of PWDs. Most PWDs have no access to assistive devices like shoe raises, braces, crutches, orthopedic shoes, corrective shoes or wheelchairs to support missing or damaged organs. Due to a lack of medical support and absence of physiotherapy, minor disabling conditions become complicated and worsen the physical and health condition of PWDs. Moreover, absence of baseline data on the profile of PWDs makes it impossible to reach all of them and provide CBR service.

Therefore, the authors of this study suggest that there should be an ecological model for the implementation of CBR in Gedeo zone. It is advisable that the Gedeo zone administration office and zone social and labor affair department train social workers with a modern concept of CBR and assign them in the community. The Gedeo zone administration office should consider establishing rehabilitation centers in various districts of the zone.

The Gedeo zone administration office must consider that the practice of CBR in the zone should gear toward inclusive development. CBR service must consider the matrix of CBR (WHO, 2010) to ensure the inclusion of PWDs. For CBR service, Gedeo zone administrative bodies must assume responsibility in establishing a multidisciplinary approach among community workers, physiotherapist, occupational therapists, counselors, special needs and inclusive education experts and GOs and NGOs offices.

At the end of this article, the question might emerge, why this study is worth to be published in an international journal, though the data was collected in one specific region. The region, where this investigation was conducted, is not in the center of development, but it also does not belong to areas in Ethiopia with intensive development needs (such as Afar or parts of the Somali region). So the situation might represent an average of the situation in the country, and in some way also in Africa. The results may describe emerging features and structures of developments, which have started to change the situation of PWDs in some way, but under unclear directions and insufficient performance. Ethiopia is the second largest country in Africa. It is one of the largest recipients of foreign support for development issues, but it also has strong actors in the country, trying to promote support services for PWDs.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

This study was funded by the Austrian Development Agency (ADA) APPEAR project ‘Inclusion in Education for Persons with Disabilities (INEDIS).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

ACPF (2011). Children with disabilities in Ethiopia: The hidden reality. Addis Ababa: African Child Policy Forum.

Ahon Adaka, T., Obi, B. F., and Emmanuel, I. (2014). Implementation of Community-Based Rehabilitation in Nigeria: The Role of Family of People with Disabilities. Int. J. Technol. Incl. Educat. 1:2014.

Caughy, M. O., O’Campo, P., and Brodsky, A. E. (1999). Neighbourhoods, families, and children: Implications for policy and practice. J. Commun. Psychol. 27, 615–633.

Cayetano, R. D. A., and Elkins, J. (2016). Community-based rehabilitation services in low and middle-income countries in the Asia-Pacific region: successes and challenges in the implementation of the CBR matrix. Disabil. CBR Incl. Develop. 27:112. doi: 10.5463/DCID.v27i2.542

Cheausuwantavee, T. (2007). Beyond community based rehabilitation. Consciousness and meaning. Bangalore: Asia Pacific Disabil. Information Journal.

Como, E., and Batdulam, T. (2012). The role of community health workers in the Mongolian CBR programme. Disabil. CBR Incl. Develop. 23, 14–33. doi: 10.5463/DCID.v23i1.96

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

CSA (2007). Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Central Statistical Authority.

Donald, K. A., Kakooza, A. M., Wammanda, R. D., Mallewa, M., Samia, P., Babakir, H., et al. (2015). Pediatric Cerebral Palsy in Africa Where Are We? J. Child Neurol. 30, 963–971. doi: 10.1177/0883073814549245

Duyan, V. (2007). The community effects of disabled sports. Amputee sports for victims of terrorism. Amsterdam: IOS Press, 70–77.

FSCE (2000). Investigating the implementation of community-based rehabilitation program for children with physical disabilities in Adama town. Addis Ababa: Forum on street children Ethiopia.

Gona, J. K., Mung’ala-Odera, V., Newton, C. R., and Hartley, S. (2011). Caring for children with disabilities in Kilifi, Kenya: what is the carer’s experience? Child Care Health Dev. 37, 175–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01124.x

ILO, UNESCO, and WHO (2004). CBR: A Strategy for Rehabilitation, Equalization of Opportunities, Poverty Reduction and Social Inclusion of People with Disabilities Joint Position Paper. Geneva: ILO.

Irene, K., and Albine, M. (2018). Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 24, 120–124. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375092

Jacob, U. S. (2015). Utilization of community based rehabilitation for persons’ with disabilities (PWD) in Nigeria: the way forward. Eur. Sci. J. 11:25.

Jolley, E., Thivillier, P., and Smith, F. (2014). Disability Disaggregation of Data - Baseline Report. Available online at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/c15a/5ab683612ff56e55263810652d5ba6b3a591.pdf[retrieved 2020-02-04].

Kahsay, T. (2010). The State of Community Based Rehabilitation Approaches of Children With Disabilities. Unpublished MA thesis Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University.

Korstjens, I., and Moser, A. (2017). Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 24, 120–124.

Lang, R. (2000). The Role of NGOs in the Process of Empowerment and Social Transformation of People With Disabilities. Selected Readings in Community Based Rehabilitation. Bangalore: Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal.

Lorenzo, T., and Motau, J. (2014). ‘A transect walk to establish opportunities and challenges for youth with disabilities in Winterveldt, South Africa’. Disabil. CBR Inclus. Devel. 25, 45–63. doi: 10.5463/dcid.v25i3.232

Lukia, N., Hamid, O. K., Sebastian, O. B., Chrispus, M., and Jacob, A. B. (2017). Disability Characteristics of Community-Based Rehabilitation Participants in Kayunga District, Uganda. Anna. Glob. Health 83, 3–4.

Mauro, V., Biggeri, M., and Deepak, S. (2014). The effectiveness of community based rehabilitation programmes: an impact evaluation of a quasi-randomised trial. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 68, 1102–8. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-203728

Mobarak, R., Khan, N. Z., Munir, S., Zaman, S. S., and McConachie, H. (2000). Predictors of stress in mothers of children with cerebral palsy in Bangladesh. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 25, 427–433. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/25.6.427

Morita, H., Yasuhara, K., Ogawa, R., and Hatanawa, H. (2013). Factors impeding the advancement of community-based rehabilitation: Degree of understanding of professionals about CBR’. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 25, 413–423. doi: 10.1589/jpts.25.413

Mprah, W. K. (2013). Perceptions about barriers to sexual and reproductive health information and services among deaf people in Ghana. Disabil. CBR Incl. Dev. 24:2136. doi: 10.5463/dcid.v24i3.234

Pradeep, K., Sushma and Aishwarya, R. (2018). Emergence of community based rehabilitation for persons with disability in India. Delhi Psych. J. 21.

Rolfe, G. (2006). Validity, trustworthiness and rigour: quality and the idea of qualitative research. J. Adv. Nurs. 53, 304–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03727.x

Seijas, V. A., Lugo, L. H., Cano, B., Ecobar, L. B., Quintero, C., Nugraha, B., et al. (2018). Understanding community-based rehabilitation and the role of physical and rehabilitation medicine. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 54, 4530–4535. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.16.04530-4535

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Educat. Inform. 22, 63–75. doi: 10.3233/efi-2004-22201

Theeraphong, B., and Mokbul, M. A. (2009). Why does community-based rehabilitation fail physically disabled women in northern Thailand? J. Develop. Pract. 19, 28–38. doi: 10.1080/09614520802576351

Tigabu, G. (2008). An assessment of neighbours of persons with disabilities in Addis Ababa. Unpublished MA thesis Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University.

UNICEF (2007). Promoting the rights of children with disabilities, Innocent Digest, no. 13. Florence: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre.

United Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific [ESCAP]/World Health Organisation [WHO] (2008). Training Manual on Disability Statistics. Geneva: World Health Organization.

United Nations [UN] (2008). UN Convention on the Rights of Persons With Disabilities. New York: United Nations.

UPHLS (2015). Needs assessment of people with disabilities in HIV and AIDS services and strategies to meet them for equal and equitable services.

Vicent, N. A. (2014). Ensuring the Quality of the Findings of Qualitative Research: Looking at Trustworthiness Criteria. J. Emerg. Trends Educat. Res. Polic. Stud. 5, 272–281.

Wegayehu, T. (2004). A study of the principles and practices of community based vocational rehabilitation and its implication for Ethiopia, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education. Canada: University of Toronto.

WHO (2004). CBR: A Strategy for Rehabilitation, Equalization of Opportunities, Poverty Reduction and Social Inclusion of People with Disabilities. Geneva: WHO.

WHO. (2010). The world health report: Health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization.

World Health Organization [WHO] (2011). World Report on Disability. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Yeshimebet, A. (2014). Impact of Rehabilitation Centre on the psycho-social Condition of Children with Physical Impairment. Addis Ababa: Submitted to Graduate School of Social Work. AAU. MA Thesis.

Keywords: Ethiopia, Gedeo zone, disability, community-based rehabilitation, inclusive development

Citation: Ayalew AT, Adane DT, Obolla SS, Ludago TB, Sona BD and Biewer G (2020) From Community-Based Rehabilitation (CBR) Services to Inclusive Development. A Study on Practice, Challenges, and Future Prospects of CBR in Gedeo Zone (Southern Ethiopia). Front. Educ. 5:506050. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.506050

Received: 19 October 2019; Accepted: 28 September 2020;

Published: 23 October 2020.

Edited by:

Brahm Norwich, University of Exeter, United KingdomReviewed by:

Lynne Sanford Koester, University of Montana, United StatesTirussew Teferra Kidanemariam, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia

Copyright © 2020 Ayalew, Adane, Obolla, Ludago, Sona and Biewer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gottfried Biewer, Z290dGZyaWVkLmJpZXdlckB1bml2aWUuYWMuYXQ=

Ababu T. Ayalew

Ababu T. Ayalew Dejene T. Adane

Dejene T. Adane Solomon S. Obolla

Solomon S. Obolla Tesfaye B. Ludago

Tesfaye B. Ludago Berhanu D. Sona

Berhanu D. Sona Gottfried Biewer

Gottfried Biewer