- 1Department of International Health, Maastricht University, Faculty of Health Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht, Netherlands

- 2Children’s Rehabilitation Department, Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Kaunas, Lithuania

- 3Department of Public Health and Epidemiology, Riga Stradins University, Riga, Latvia

- 4Institute of Public Health, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

- 5Autism Research Centre, Department of Psychiatry, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

- 6Department of Health Policy Management, Institute of Public Health, Faculty of Health Care, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland

- 7National Institute of Public Health, Warsaw, Poland

The Soviet occupation of the Baltic States followed by joining the United Nations (UN) and European Union make these countries an interesting point of comparison in the development of autism and education policy. This study investigates how policies changed following the transition and how the right and access to education are facilitated for autistic children by performing a path dependence analysis. All Baltic States created new education policies following the transition out of the Soviet era, with their accession to the UN and their appetite to follow internationally available guidance. The right to education for all children in was adopted in all education systems. Education facilities for children with disabilities were implemented in all countries. Afterward, all countries started toward the development of more inclusive systems. Nevertheless, the majority of policies did not specify for autism, yet covered special education needs in general. A development in Latvia should be noted, where various special education needs are outlined in national policy, along with provisions and professional assistance required to address them in mainstream or special classrooms. Ultimately, education policy flourished after the transition. Their development caught up to other European Union countries and they are currently working on implementing inclusive education.

Introduction

The Baltic States (a geopolitical term for Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania) were occupied by the Soviet Union until late 1980s, at which point their independence became inevitable as the Soviet Union began to dissolve (Beissinger, 2009). This ultimately led to a transitional period in which the Soviet Union collapsed and the individual Baltic States were re-established (Van Elsuwege, 2008; Kerikmäe et al., 2018). The Baltic States proceeded to each join the United Nations (UN) in 1991 and the European Union (EU) in 2004 (European Union, 2020; United Nations, 2020).

With the accession to the UN and EU, respectively, the Baltic States were introduced to the values set out in international documents, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the Salamanca Statement and later the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) (UNESCO, 1994; United Nations, 1948; United Nations, 2006). In these documents, the right to education for children with special education needs (SEN) is well established, including autistic children. However, endorsing this right with respect to access to education for autistic children in the EU has been complicated (Carroll et al., 2017). With a male-to-female ratio between 3:1 and 4:1, autism affects roughly 1% of the population and around 1 in 160 children (Lai et al., 2014; Loomes et al., 2017; World Health Organisation, 2019). Autistic people may be more susceptible to serious health and other functional difficulties that may cause financial problems for families and caregivers and the condition can still carry substantial stigma (Howlin et al., 2004; Knapp et al., 2009; van Heijst and Geurts, 2015; World Health Organisation, 2017). To address these circumstances and improve the inclusion and quality of life of the autism community across Europe, the implementation of fundamental rights of education is crucial (European Commission, 2010; Hehir et al., 2016).

Prior work by the European Consortium for Autism Researchers in Education (EDUCAUS) established that the implementation of the UDHR and CRPD had great impact in the development of the education systems with regards to autistic children (Roleska et al., 2018; van Kessel et al., 2019a,b). In these analyses, it was outlined that the UDHR, CRPD, and other UN policies set out values and directions for education systems to develop in. For instance, the UDHR set out the right to education for everyone. Subsequently, facilities where children with SEN could be educated were implemented in the countries under study. The Salamanca Statement and CRPD both emphasized the importance of developing inclusive education, which the countries under study subsequently started to develop.

This paper will extend the policy mapping project of EDUCAUS into the Baltic States. Even though Estonia (1.3 million inhabitants), Latvia (1.9 million inhabitants), and Lithuania (2.8 million inhabitants) represent only 6 million EU citizens and roughly 1% of the EU population (Eurostat, 2018), their shared history with the Soviet Union and subsequent development under the influence of the UN and EU make them an interesting point of comparison to see how a transition of ideology impacts the development of the respective education systems. More specifically, this study has two aims: (1) investigate what effects the transition from the Soviet era to the UN had on special education policy for autistic children; and (2) explore how the education systems have developed in regards to special education and inclusive education for autistic children.

Materials and Methods

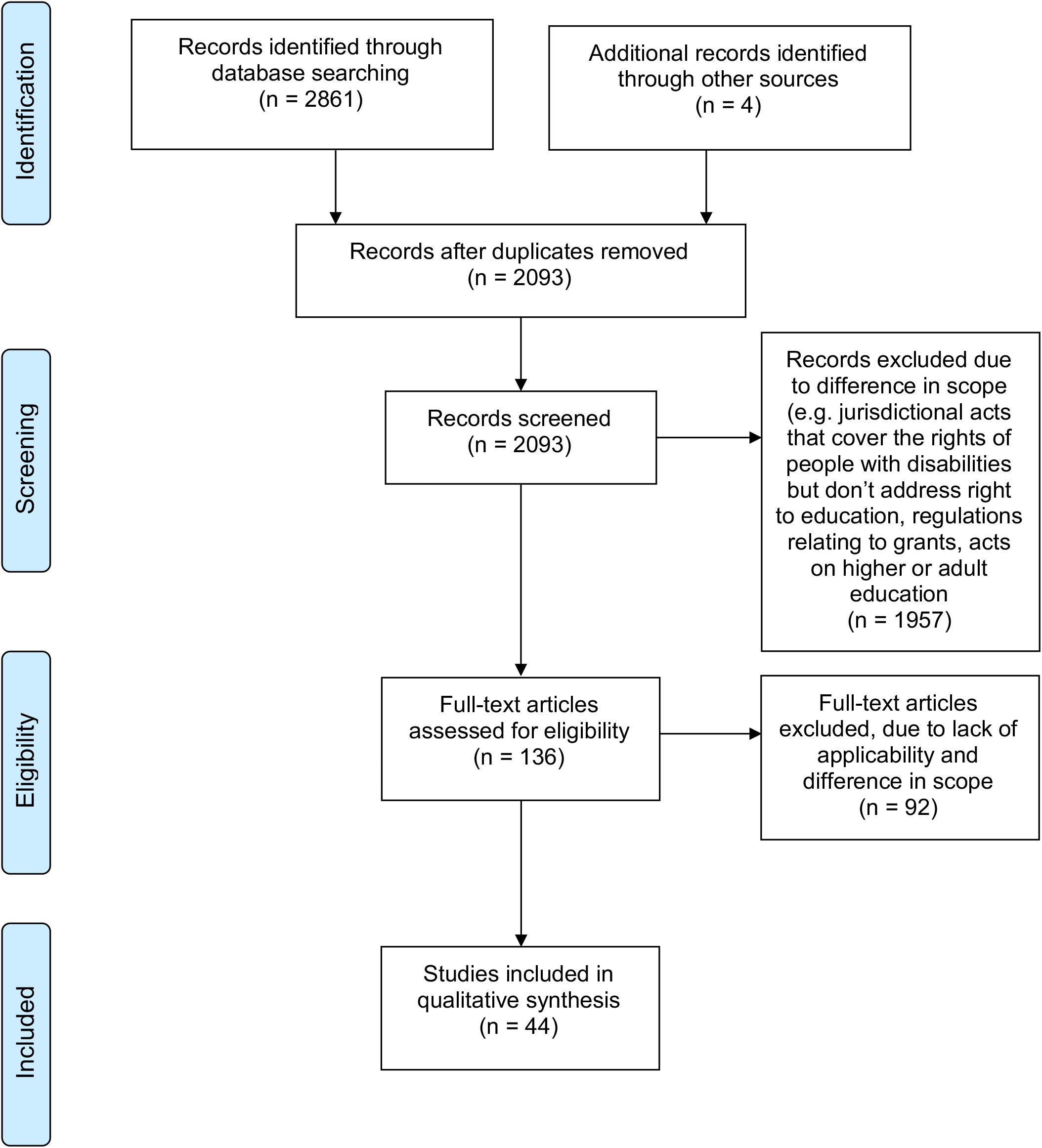

Since the analysis in this paper focuses on the interaction of different policy layers in a temporal manner, a path dependence analysis was used. This methodology enables us to see policy creation as historical sequences and patterns and identify path dependence (Mahoney, 2000). The usage of this methodology is consistent with and validated by previous work of EDUCAUS (Roleska et al., 2018; van Kessel et al., 2019a,b). Data were gathered through the use of a scoping review, which allows for rapid mapping of the key concepts that underpin a wide research area and is particularly suitable for exploring complex matters that have not yet been comprehensively reviewed (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005; Levac et al., 2010). Due to there not being a comprehensive data source in the EU on autism and SEN policy, a modular approach to legislative and policy work was adopted to analyze the different educational policy environments (Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian). This approach adopted the systematic search strategy that is outlined in the PRISMA framework by establishing clear eligibility criteria, defining information sources, reporting the complete search query, and outlining the data collection process and the data items that were looked for Moher et al. (2009). Risk of bias assessment was not translated into this methodology, since this work uses policy data. The findings were also reported based on the PRISMA framework by reporting the exact number of documents included per country, giving an overview of the individual documents, and a synthesis of the documents (Moher et al., 2009).

Eligibility Criteria

Eligibility criteria were similar to previous work by EDUCAUS for consistency purposes (Roleska et al., 2018; van Kessel et al., 2019a,b). Documents that fit the inclusion criteria should conform to (1) having a scope relating to the right to education, national education system, disability laws, inclusion, or special education needs; (2) aiming at children under 18 years; (3) being drafted by a governmental institution; and (4) being published after 1948. Constitutions were always included and no language limitations were set. Non-governmental policies and actions were excluded. It has to be noted that, in previous works by EDUCAUS, it became evident that autism-specific policy is not always present. In case this happens, general SEN or education policy was analyzed instead and the implications for the autism community were discussed.

Data Collection and Search Strategy

Similar to previous work (Roleska et al., 2018; van Kessel et al., 2019a,b), the data collection consisted of five steps in which governmental policy repositories formed the primary source of data collection: (1) review and extract relevant policies and legislation that address the right to education of autistic people directly from original governmental sources; (2) develop a multi-layered search strategy for scientific databases (PubMed and Google Scholar); (3) merging policy and academic publications according to the eligibility criteria; (4) acquire further information through searching reference lists of key articles; and (5) merge the three searches into one single data repository for the purpose of this scoping review and to compare it to the already mapped policy of the United Nations and the EU for further analysis.

Table 1 shows the governmental policy repositories that were used per country. The search strategy involved searching the full-text for the respective keywords, instead of just titles and abstracts in order to minimize the risk of overlooking policy as a result of inaccurate or incomplete translations. The keywords used for the policy repositories were as follows: autism, disability, special education needs, education, special needs, special education, inclusive education. These were translated into Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian, respectively, and used individually, as combining the keywords in the policy repositories yielded little relevant results. Subsequently, the exact build-up of the search query used for scientific databases is shown in Table 2. The data collection took place between May 23rd and June 13th 2019.

Data Analysis

Gathered data was analyzed using the UN and EU policy data that was mapped in previous EDUCAUS papers (Roleska et al., 2018; van Kessel et al., 2019a). Supplementary File 1 shows an overview of the policy data of the respective policies. As such, the extent to which the values of international policies are integrated in the national policies could be established. To gauge the development of the Baltic education systems after regaining their independence, implementation of the values that were set out in international policy were tracked by reporting on the clusters of policies that accounted for the implementation of international values: (1) the universal right to education laid down in the UDHR; (2) the right for children to receive appropriate treatment consistent with their condition by the Declaration on the Rights of the Child; (3) the right for children with developmental, intellectual, and learning conditions to receive appropriate education to maximize their potential by the Declaration on the Rights of Disabled Persons; and (4) the development of an inclusive education environment as set out by the Salamanca Statement and the CRPD.

Results

A total of 2861 sources were identified through electronic database searching and four through other sources. Ultimately, 44 sources were included in this scoping review. A PRISMA flowchart illustrates the data selection process in Figure 1. A synthesis of the policy data outlining development of the education systems is reported below, while the contents of each individual policy that are used in the synthesis is added in Supplementary File 2. References to all included policies are included in Supplementary File 3.

However, since both the Estonian and Latvian databases did not expand on legislation prior to their regained independence, an additional five sources were identified using the non-scientific database “Google” and added as gray literature in this review. Considering the lack of initial data prior to 1991 in two of the three countries under review and the stated fact that the Soviet Union acted in this time period in all three countries as a federal state, an additional sub-chapter is added in the results section covering Soviet federal law on the right to education for autistic children.

The Baltic Soviet Socialist Republics

The Soviet Union advocated a notion of rights different from the conception of fundamental rights in the West (Patenaude, 2012): Western rights aim to protect citizens and prevent the government from amassing too much power, while Soviet rights were given out and dictated by the government. The right to education and facilities to educate children with SEN in general were implemented—though from a different ideological perspective. Whereas UN-based policies state that their aim is to enable children with SEN to develop themselves to their maximum potential with a focus on autonomy (United Nations, 1975), the Soviet-based policies specifically state that they aimed to develop children with SEN in a way they can do socially useful work (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, 1973).

Estonia

The right to education for all children was re-established immediately upon the introduction of the new Estonian constitution in 1992 (Republic of Estonia, 1992). Subsequent policies in the 1990’s all shared the common theme of shaping the education system in a way that every child had a place: continuous education was developed for all children, schools were established to give children with SEN a place to follow education and have their needs met timely and adequately, and adapted curricula were formed that were appropriate to the SEN of a child (Republic of Estonia, 1993a; Republic of Estonia, 1993b; Republic of Estonia, 1993c; Republic of Estonia, 1993d). A multidisciplinary advisory committee was also established during this timeframe—which functioned as a guiding body in determining the location and curriculum for children with SEN (Republic of Estonia, 1999a; Republic of Estonia, 1999b). The term “inclusion” mentioned in this document refers to including children with SEN in the education system rather than mainstream education.

Policies from 2010 onward, however, aimed more at developing inclusive education. Education was organized with the ideology to admit children with SEN into mainstream schools as much as possible (Republic of Estonia, 2010; Republic of Estonia Ministry of Education and Research, 2014; Republic of Estonia, 2018; Republic of Estonia, 2016). An updated definition of SEN was introduced, namely a child whose talents, learning difficulties, state of health, disability, behavioral and emotional disturbances, prolonged absence from school or insufficient knowledge of the language of instruction necessitates changes or adjustments; classes for children with SEN that cannot participate in mainstream education were limited in their membership numbers, and an acknowledgment was made to adjust mainstream content to the needs of the child with SEN where possible and necessary.

Ultimately, with reference to the educational dimensions of the UN (United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 2016), a system of integration is currently in place. Additionally, it has to be noted that Estonia has not implemented autism-specific policy. Instead, all policies discuss children with SEN in general.

Latvia

Initially, a segregated approach is described by placing children with SEN in either sanatoria-type schools or educational and upbringing institutions, where they received care and education and, upon graduation, would receive a standard educational document (Republic of Latvia, 1991). This further developed in 1993 when the rights of people with disabilities were established at the national level (Republic of Latvia, 1993), which included the right to appropriate education—involving additional equipment or technical aides—at home and in schools. 1998 saw the introduction of anti-discrimination legislation that applied on the basis of disability (Republic of Latvia, 1998a); the reaffirmation of free, compulsory education for all children in Latvia (Republic of Latvia, 1998a); the establishment of rights specifically for children, including the right to develop according to individual capabilities, as well as the guarantee that professionals are specifically trained to work with children with SEN (Republic of Latvia, 1998b); and the ratification of a new education law that abolished the excluding elements set out in the 1991 iteration by introducing a framework on special education (Republic of Latvia, 1998c) 1999 marked the end of the first group of education-related policies by further elaborating on possibilities for education programs for children with SEN (Republic of Latvia, 1999). It is mentioned that mainstream schools can admit children with SEN when they can provide the assistance the child needs—which points to an initial element of integration-inclusion practice.

The second group of education-related policies commenced in 2010 with the introduction of rights for students with SEN at all school levels (Republic of Latvia, 2010). Subsequently, assistant services were introduced for children with SEN, along with requirements that people who would deliver these assistant services should adhere to in terms of their education (Republic of Latvia, 2012a). Pedagogical Medical Commissions were implemented to further streamline the education of children with SEN and promote their integration in mainstream education (Republic of Latvia, 2012b). Autism, atypical autism, and Asperger’s syndrome—the differentiations of autism that were included in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000)—were also specifically mentioned as possible diagnoses for children with SEN. A definition on inclusive education was introduced that acknowledged the array of needs that children with SEN can have and calls for inclusion in the education system (Republic of Latvia, 2014). It, however, fails to address the element that is present in the international definition of the unification of education—merging mainstream and special education in a single entity. Special Education Development Centres aimed to provide consultative and methodical support to parents, children and educators in the areas of diagnosis, methodical and pedagogical assistance, and organization of events (Republic of Latvia, 2016). Finally, specific provisions (i.e., equipment, support measures, and additional staff) that are necessary, preferred, and/or desirable to be implemented in mainstream or special classrooms were set out (Republic of Latvia, 2018). While autism is not specifically mentioned, various co-occurring conditions that appear with autism are listed (Lai et al., 2014), such as visual- and hearing impairment, learning disabilities, and mental health problems.

Lithuania

Development of the education system in Lithuania happened in two parts. Firstly, in the period of 1991–2002, the constitution instantly implemented compulsory education for all children until the age of 18 (Republic of Lithuania, 1992). Simultaneously, the right to education for people with disabilities was established (Republic of Lithuania, 1991b), as well as the option for children with SEN to be educated in special classes in mainstream schools (Republic of Lithuania, 1991a). The structure for special education was elaborated, along with the implementation of a definition for SEN (Republic of Lithuania, 1998). Special education, in a Lithuanian context, is not characterized by a segregated approach—rather by an approach that is mostly similar to integration. Autism was also categorized under the umbrella of “emotional, behavioral, and social developmental disorders” (Republic of Lithuania, 2002).

The second period, ranging from 2011 until present, commenced with an update of the purpose and framework of special education—now aiming to aid children with SEN to develop their competences and skills through education and involving technical and professional assistance (Republic of Lithuania, 2011a). Autism was recategorized under the umbrella of “various developmental disorders” and a distinction was made between the several types of autism that were previously outlined in the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Republic of Lithuania, 2011b). Remaining policies in this period all aimed at establishing values and objectives to improve education and to develop education further from an integrative to an inclusive system.

Discussion

The aim of this path dependence analysis was to extend the EDUCAUS policy mapping project into the Baltic States and (1) investigate what effects the transition from the Soviet era to the UN had on special education policy for autistic children; and (2) explore how the education systems have developed in regards to special education and inclusive education for autistic children. By searching the policy repositories of the respective Baltic States, all relevant national policies on the provision of education to autistic pupils and their right to education were inspected.

Firstly, we found a shift from the value system set out by the Soviet Union to the value system outlined by the UN in all three Baltic States after regaining their independence and joining the UN (Republic of Latvia, 1990; Republic of Latvia, 1991; Republic of Estonia, 1993c). They showed willingness to follow internationally available guidance, as is seen by their reformations of the education systems to introduce and further enhance the education of children with SEN soon after their accession to the UN and their efforts to start implementing inclusive education after the ratification of the CRPD (Republic of Estonia, 2010; Republic of Latvia, 2014; Republic of Lithuania, 2014). This is consistent with other literature where it is explained that the Baltic States showed willingness to adopt new policy influences after the collapse of the Soviet Union (Van Elsuwege, 2008; Kerikmäe et al., 2018). They were also willing to make the changes necessary to join the EU during their accession process (Grigas et al., 2013).

Secondly, we found that the Baltic States specifically adopted the values set out in the UDHR, Salamanca Statement, CRPD, and other UN documents. Particularly, we found that the universal right to education as laid down in the UDHR was unanimously implemented (Republic of Lithuania, 1991a; Republic of Estonia, 1992; Republic of Latvia, 1998a). The right for children to receive appropriate treatment consistent with their condition by the Declaration on the Rights of the Child and the right for children with developmental, intellectual, and learning conditions to receive appropriate education to fully develop themselves as set out by the Declaration on the Rights of Disabled Persons were also both integrated in all three countries (Republic of Estonia, 1993c; Republic of Latvia, 1998b; Republic of Latvia, 1998c; Republic of Lithuania, 1998). Development of inclusive education started in all three countries as well, initiating the uptake of children with SEN in their mainstream systems (Republic of Estonia, 2010; Republic of Latvia, 2014; Republic of Lithuania, 2014), though none have implemented a system of full inclusion yet. This is coherent with the development of other education systems across the EU (e.g., Denmark, France, Germany, and Netherlands), where a similar level of development of the education system was found (Roleska et al., 2018; European Union, 2020; van Kessel et al., 2019a,b). One noteworthy development in Latvia is the implementation of provisions that should be present in mainstream and special classrooms based on specific forms of SEN, which has only been found in Luxembourg previously (van Kessel et al., in press) [Forthcoming 2020] and forms a key factor is the development of inclusive education (Peters et al., 2005).

Findings of this paper also further support the findings of a previous EDUCAUS paper, in which the effect of international guidance on small states within the EU was explored (van Kessel et al., in press). Estonia fits their description of a small state, namely “states that not only have a small population size, but also are not in a position to influence the international policy environment on their own and are, by extension, largely dependent on the decisions of larger states and overarching political structures.” They explained that, while tension occurs in the field of health policy, the field of education policy, international guidelines tend to be closely translated to national policy. The findings of this paper are in line with this assertion, as the values set out by international guidance have been translated directly to national policy.

From the 39 discussed policies (12 for Estonia, 15 for Latvia, 12 for Lithuania), 35 did not specify for autism (89.74%; 12 for Estonia [100%], 14 for Latvia [93.33%], and 9 for Lithuania [75%]). Instead, they relate to autism in the sense that they discuss children with SEN. While this benefits the autism community by granting them access to the services discussed in the policies, it also points toward a lack of specificity being incorporated in national policy. This is a stark contrast to other EU countries, such as France, Northern Ireland, Spain, and Flanders (Belgium), where specific autism-related policies are implemented to guide how autism should be addressed in those specific countries (Roleska et al., 2018; van Kessel et al., 2019a). Alternatively, the German-speaking community in Belgium and Luxembourg implemented institutions that are specifically geared toward assisting autistic children (van Kessel et al., 2019a). As such, even though the Baltic States are progressing on par with other EU countries in terms of the development of their education system, specifically addressing autism in national policy is an aspect in which there is still room for improvement. That being said, due to the vast majority of policies focusing on SEN in general, the implications of this study are not limited to autism and can be applied to the wider context of SEN.

This study holds several limitations. Firstly, even though the outcomes of this scoping review are not blindly transferable, the concepts that are discussed can be implemented in other education systems after accounting for local and cultural implications. Secondly, this study involves a policy analysis, meaning it cannot determine how these policies are translated into practice. Thirdly, the national legal databases of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania were used in the data search. To use these databases, the search terms had to be translated into the respective languages and the documents had to be translated back to English using machine translation services. In order to account for errors in translation and to ensure completeness of the dataset, country experts were involved to review the data analysis. Fourthly, this paper did not investigate actions taken by non-governmental organizations, which could be used to enhance national policy. Finally, this paper only investigated education policy that pertained to autistic children. As a result, autistic adults that follow education are not included in this analysis, while they may experience similar learning difficulties.

Ultimately, this study provided insight in the SEN policy environment of the Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Path dependency analysis shows the integration of most values of the UDHR, CRPD, and other international documents in national legislation. Policies from the Soviet era were all replaced with policies that reflect the values of the UN. Finally, inclusive education has become a guiding factor in the education systems of the countries under study.

Data Availability Statement

All data are achieved from publicly available databases, the used documents including their source can been found in the list of References and Supplementary File 3.

Ethics Statement

Since all used sources are publicly available and already enacted in the countries under study, no ethical implications with regards to the outcomes, and no situation in which consent needed to be requested, are present.

Author Contributions

RK was in charge of data analysis and the writing of this manuscript. WD assisted with data collection and analysis. All other authors made meaningful contributions to the manuscript at various stages in its development. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Gillings Fellowship in Global Public Health and Autism Research (Grant Award YOG054) and the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking (grant agreement No. 777394).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the reviewers for contributing to the improvement of the quality of this study.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2020.00161/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

CRPD, Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; EDUCAUS, European Consortium for Autism Researchers in Education; EU, European Union; SEN, special education needs; UDHR, Universal Declaration of Human Rights; UN, United Nations.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Arksey, H., and O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 8, 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

Beissinger, M. (2009). “The intersection of ethnic nationalism and people power tactics in the Baltic States,” in Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Non-Violent Action From Gandhi to the Present, eds A. Robert and T. Garton Ash (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Carroll, J., Bradley, L., Crawford, H., Hannant, P., Johnson, H., and Thompson, A. (2017). SEN Support: A Rapid Evidence Assessment. London: Government of the United Kingdom.

European Commission (2010). European Disability Strategy 2010-2020: A Renewed Commitment to a Barrier-Free Europe. Brussels: European Commission.

European Union (2020). Countries. Available online at: https://europa.eu/european-union/about-eu/countries#tab-0-1 (accessed on 30 April 2020).

Eurostat (2018). Population Change - Demographic Balance and Crude Rates at National Level. Available online at: http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=demo_gind&langen (accessed on 30 April 2018)

Grigas, A., Kasekamp, A., Maslauskaite, K., and Zorgenfreija, L. (2013). The Baltic States in the EU: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow. Paris: Notre Europe.

Hehir, T., Grindal, T., Freeman, B., Lamoreau, R., Borquaye, Y., and Burke, S. (2016). A Summary of the Research Evidence on Inclusive Education. São Paulo, CA: Instituto Alana.

Howlin, P., Goode, S., Hutton, J., and Rutter, M. (2004). Adult outcome for children with autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 45, 212–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00215.x

Kerikmäe, T., Chochia, A., and Atallah, M. (2018). The Baltic States in the European Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Knapp, M., Romeo, R., and Beecham, J. (2009). Economic cost of autism in the UK. Autism 13, 317–336. doi: 10.1177/1362361309104246

Lai, M.-C., Lombardo, M. V., and Baron-Cohen, S. (2014). Autism. Lancet 383, 896–910. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61539-1

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., and O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

Loomes, R., Hull, L., and Mandy, W. P. L. (2017). What is the male-to-female ratio in autism spectrum disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 56, 466–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.013

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., and Altman, D. G., and Prisma Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/BMJ.B2535

Patenaude, B. (2012). Regional Perspectives on Human Rights: The USSR and Russia, Part One. Available online at: http://spice.stanford.edu (accessed on 21 November 2019)

Peters, S., Johnstone, C., and Ferguson, P. (2005). A disability rights in education model for evaluating inclusive education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 9, 139–160. doi: 10.1080/1360311042000320464

Republic of Estonia (1992). Constitution of the Republic of Estonia. Available online at: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/24304 (accessed on 23 November 2019)

Republic of Estonia (1993a). Basic Schools and Upper Secondary Schools Act. Available online at: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/28542 (accessed on 23 November 2019)

Republic of Estonia (1993b). Child Protection Act. Available online at: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/30657 (accessed on 23 November 2019)

Republic of Estonia (1993c). Education Act. Available online at: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/30588 (accessed on 23 November 2019)

Republic of Estonia (1993d). Preschool Child Care Institution Act. Available online at: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/28539 (accessed on 23 November 2019)

Republic of Estonia (1999a). Act Amending and Supplementing the Basic Schools and Upper Secondary Schools Act. Available online at: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/77246 (accessed on 23 November 2019)

Republic of Estonia (1999b). Approval of the Simplified National Curriculum for Basic Education (Curriculum for Assistive Education). Available online at: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/90764 (accessed on 23 November 2019)

Republic of Estonia (2010). Basic Schools and Upper Secondary Schools Act. Available online at: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/13332410#jg4 (accessed on 23 November 2019)

Republic of Estonia (2016). Organizing the Network of Basic Schools for Students with Special Educational Needs 2014-2020. Available online at: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/101032019006 (accessed on 23 November 2019)

Republic of Estonia (2018). Applying the Principles of Inclusive Education in General Education Schools 2014-2020. Available online at: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/118042018001#para2 (accessed on 23 November 2019)

Republic of Estonia Ministry of Education and Research (2014). The Estonian Lifelong Learning Strategy 2020. Tartu: Republic of Estonia Ministry of Education and Research.

Republic of Latvia (1990). Declaration by the Supreme Council of the Socialist Republic of Latvia Regarding the Restoration of Independence of the Republic of Latvia. Available online at: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/75539-par-latvijas-republikas-neatkaribas-atjaunosanu (accessed on 23 November 2019).

Republic of Latvia (1991). Education Law of the Republic of Latvia. Available online at: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/67960-latvijas-republikas-izglitibas-likum (accessed on 23 November 2019).

Republic of Latvia (1993). Law of the Republic of Latvia on Medical and Social Protection of the Disabled. Available online at: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/66352-par-invalidu-medicinisko-un-socialo-aizsardzibu (accessed on 23 November 2019).

Republic of Latvia (1998a). Amendments to the Constitution of the Republic of Latvia. Available online at: https://www.vestnesis.lv/ta/id/50292-grozijumi-latvijas-republikas-satversme (accessed on 23 November 2019)

Republic of Latvia (1998b). Children’s Rights Protection Law. Available online at: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/49096-bernu-tiesibu-aizsardzibas-likums (accessed on 23 November 2019).

Republic of Latvia (1998c). Education Law. Available online at: https://www.vestnesis.lv/ta/id/50759-izglitibas-likums (accessed on 23 November 2019)

Republic of Latvia (1999). Law of General Education. Available online at: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/20243-visparejas-izglitibas-likums (accessed on 23 November 2019).

Republic of Latvia (2010). Disability Law. Available online at: https://likumi.lv/doc.php?id=211494 (accessed on 23 November 2019).

Republic of Latvia (2012a). Arrangements for Awarding and Financing Assistant Services at Educational Establishments. Available online at: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/252140-kartiba-kada-pieskir-un-finanse-asistenta-pakalpojumu-izglitibas-iestade (accessed on 27 November 2019).

Republic of Latvia (2012b). Regulations on Pedagogical Medical Commissions. Available online at: https://www.vestnesis.lv/op/2012/165.7 (accessed on 23 November 2019)

Republic of Latvia (2014). Education Development Guidelines 2014-2020. Available online at: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/266406 (accessed on 23 November 2019).

Republic of Latvia (2016). Regulations Regarding Criteria and Procedures for Granting the Status of Special education development Centre to a Special Education Institution. Available online at: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/281256-noteikumi-par-kriterijiem-un-kartibu-kada-specialas-izglitibas-iestadei-pieskir-specialas-izglitibas-attistibas (accessed on 6 December 2019).

Republic of Latvia (2018). Requirements for Admission of Students with Special Needs to General Education Programs Implemented by General Education Institutions. Available online at: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/301251 (accessed on 6 December 2019).

Republic of Lithuania (1991a). Law on Education of the Republic of Lithuania. Available online at: https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/TAR.9A3AD08EA5D0 (accessed on 25 November 2019)

Republic of Lithuania (1991b). Law on the Social Integration of the Disabled. Available online at: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.2319?jfwid=32wfa0a4 (accessed on 25 November 2019).

Republic of Lithuania (1992). Constitution of the Republic of Lithuania. Available online at: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.1890?positionInSearchResults=17&searchModelUUID=01ecf603-c354-4a15-8dfa-b2de55568575 (accessed 25 November 2019).

Republic of Lithuania (1998). Law on Special Education. Available online at: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.69873?positionInSearchResults=3&searchModelUUID=f0d810cf-e202-4808-8980-b8ee642d582d (accessed on 25 November 2019).

Republic of Lithuania (2002). Order on the Procedure for the Identification of Persons with Special Needs and their Degree and the Assignment of Persons with Special Needs to the Special Education Needs. Available online at: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.180989?jfwid=-hok3irklu (accessed on 25 November 2019).

Republic of Lithuania (2011a). Law Amending the Law on Education of the Republic of Lithuania. Available online at: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.395105?jfwid=-edboaxtlh (accessed on 25 November 2019).

Republic of Lithuania (2011b). Order on the Approval of the Description of the Procedure for the Identification of Groups of Pupils with Special Education Needs. Available online at: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.404013/asr (accessed on 25 November 2019).

Republic of Lithuania (2014). 2014-2016 Action Plan for the Strengthening of Public Education and the Development of Inclusive Education. Available online at: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/74fc2e20379b11e48908b52e62efa377?jfwid=-edboaxq4p (accessed on 25 November 2019).

Roleska, M., Roman-Urrestarazu, A., Griffiths, S., Ruigrok, A. N. V., Holt, R., van Kessel, R., et al. (2018). Autism and the right to education in the EU: policy mapping and scoping review of the United Kingdom, France, Poland and Spain. PLoS One 13:e0202336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202336

UNESCO (1994). The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. Paris: UNESCO.

Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (1973). Law about the Approval of Bases Legislations of the Union of the SSR and the Union Republic About Public Education. Available online at: http://www.libussr.ru/doc_ussr/usr_8127.htm (accessed on 21 November 2019)

United Nations (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. New York, NY: United Nations.

United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2016). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities General Comment No. 4. New York, NY: United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Van Elsuwege, P. (2008). From Soviet Republics to EU Member States. A Legal and Political Assessment of the Baltic States’ Accession to the EU. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

van Heijst, B. F. C., and Geurts, H. M. (2015). Quality of life in autism across the lifespan: a meta-analysis. Autism 19, 158–167. doi: 10.1177/1362361313517053

van Kessel, R., Hrzic, R., Czabanowska, K., Baranger, A., Azzopardi-Muscat, N., Charambalous-Darden, N., et al. (in press). Autism and the influence of international legislation on small EU member states: policy mapping in Malta, Cyprus, Luxembourg, and Slovenia. Eur. J. Pub. Health doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckaa146

van Kessel, R., Roman-Urrestarazu, A., Ruigrok, A., Holt, R., Commers, M., Hoekstra, R. A., et al. (2019a). Autism and family involvement in the right to education in the EU: policy mapping in the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany. Mol. Autism 10, doi: 10.1186/s13229-019-0297-x

van Kessel, R., Walsh, S., Ruigrok, A. N. V., Holt, R., Yliherva, A., Kärnä, E., et al. (2019b). Autism and the right to education in the EU: policy mapping and scoping review of Nordic countries Denmark, Finland, and Sweden. Mol. Autism 10, doi: 10.1186/s13229-019-0290-4

Keywords: autism, special education needs, policy, Baltics, special education, inclusive education

Citation: van Kessel R, Dijkstra W, Prasauskiene A, Villeruša A, Brayne C, Baron-Cohen S, Czabanowska K and Roman-Urrestarazu A (2020) Education, Special Needs, and Autism in the Baltic States: Policy Mapping in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Front. Educ. 5:161. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00161

Received: 12 June 2020; Accepted: 10 August 2020;

Published: 04 September 2020.

Edited by:

Gregor Ross Maxwell, UiT – The Arctic University of Norway, NorwayReviewed by:

Despina Papoudi, University of Birmingham, United KingdomGarry Squires, The University of Manchester, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2020 van Kessel, Dijkstra, Prasauskiene, Villeruša, Brayne, Baron-Cohen, Czabanowska and Roman-Urrestarazu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Robin van Kessel, cmpjLnZhbmtlc3NlbEBhbHVtbmkubWFhc3RyaWNodHVuaXZlcnNpdHkubmw=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Robin van Kessel

Robin van Kessel Wiki Dijkstra1

Wiki Dijkstra1 Anita Villeruša

Anita Villeruša Simon Baron-Cohen

Simon Baron-Cohen Katarzyna Czabanowska

Katarzyna Czabanowska